1. Introduction

Emotions in animals are intricate and multifaceted phenomena that play a vital role in their survival, social interactions, and overall well-being. These adaptive mechanisms have evolved over millennia to enable animals to respond appropriately to environmental challenges and opportunities, such as avoiding threats, pursuing rewards, and fostering social cohesion [

1,

2,

3]. In horses, emotions are expressed through a range of measurable physiological and behavioral responses, making them a focal point for understanding equine welfare and their interactions with humans [

4,

5].

The scientific study of emotions in horses gained momentum in the late 20th century, coinciding with advancements in behavioral science, cognitive research, and physiological monitoring technologies [

4,

6,

7]. These developments have not only enhanced our understanding of equine emotional states but have also underscored the significance of emotional contagion in horse-human relationships. Emotional contagion, defined as the transfer of emotional states between individuals, is a fundamental mechanism underpinning social communication and cohesion in many species, including horses [

8].

Horses, as highly social animals, possess a sophisticated emotional repertoire that facilitates interactions within their species and with humans. They are acutely sensitive to environmental cues and the emotional states of conspecifics, as well as those of their human handlers. This sensitivity enables horses to respond to subtle emotional signals, fostering effective communication and coordination within social groups [

9,

10]. Research has shown that horses can detect human emotional cues, such as facial expressions and vocal tones, and adapt their behavior accordingly [

11,

12]. For instance, horses have been observed to differentiate between positive and negative human emotional expressions, responding more favorably to calm and relaxed individuals than to nervous or agitated ones [

13].

Understanding the physiological and behavioral manifestations of emotions in horses is critical for advancing equine welfare. Physiological responses, such as changes in heart rate variability (HRV), cortisol levels, and eye temperature, provide objective measures of emotional states. HRV, in particular, has emerged as a valuable indicator of autonomic nervous system balance, reflecting the interplay between the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches [

14]. High HRV is associated with relaxation and positive emotional states, while low HRV often indicates stress or emotional arousal [

15]. Similarly, cortisol, a hormone commonly linked to stress, serves as a key biomarker for assessing emotional responses in horses. Cortisol levels can be measured using non-invasive methods such as saliva analysis, which minimizes stress during sample collection [

16].

Behavioral indicators are equally important for evaluating equine emotions. Ethograms, which catalog specific behaviors associated with emotional states, have become a standard tool in this field. Behavioral responses such as ear and tail positions, vocalizations, and locomotion patterns provide visible clues to a horse's emotional state [

9,

17]. Advanced methodologies, including the Equine Grimace Scale (EGS) and the Equine Facial Action Coding System (EquiFACS), have further refined the ability to assess pain-related and emotional expressions through facial cues [

12,

18].

The study of horse-human emotional contagion has also benefited from technological advancements. Wearable devices for monitoring HRV and other physiological parameters have enabled researchers to collect data in real-time, reducing the potential for observer-induced bias [

19]. These technologies, originally developed for human applications, have been adapted to equine research, offering unprecedented precision in measuring stress and emotional states during various activities, including training and therapy sessions. Emerging tools such as machine learning algorithms and neural networks are now being employed to analyze complex datasets, paving the way for automated emotion recognition in horses [

20].

One of the most intriguing aspects of equine emotional research is the bidirectional nature of horse-human interactions. Studies have demonstrated that emotional states can be transferred not only from humans to horses but also from horses to humans, highlighting the dynamic interplay within this dyad [

21]. For example, synchronicity in HRV between horses and their handlers during in-hand tasks underscores the depth of emotional connection and mutual influence in these relationships [

22]. This finding has profound implications for equine-assisted therapies, where the emotional alignment between horse and human is often a cornerstone of therapeutic success.

Despite these advancements, several challenges remain in the study of horse-human emotional contagion. One significant hurdle is the lack of a standardized framework for interpreting physiological and behavioral data across different contexts. While HRV and cortisol levels are widely used as indicators of stress and emotional arousal, their interpretation can vary depending on factors such as the horse's baseline physiological state, environmental conditions, and individual temperament [

4,

23]. Similarly, behavioral assessments often rely on subjective observations, which may introduce variability in data collection and analysis [

9].

The integration of behavioral, physiological, and technological approaches offers a promising pathway for overcoming these challenges. By combining ethological observations with advanced physiological monitoring and computational analytics, researchers can achieve a more holistic understanding of equine emotions. For instance, combining HRV analysis with thermal imaging and behavioral ethograms can provide a comprehensive view of how horses respond to specific stimuli, enhancing the reliability and validity of emotional assessments [

14,

23].

Moreover, interdisciplinary collaboration between fields such as veterinary science, cognitive psychology, and artificial intelligence is essential for advancing the study of equine emotions. Recent developments in wearable technology and machine learning have the potential to revolutionize this field by enabling continuous, non-invasive monitoring of emotional states in both horses and humans [

24]. These innovations not only enhance research capabilities but also have practical applications in equine training, welfare, and therapeutic interventions.

The study of horse-human emotional contagion is an evolving field that bridges multiple disciplines, offering valuable insights into the emotional lives of horses and their interactions with humans. By systematically reviewing the methods and outcomes of this research, this paper aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of how emotions are expressed, shared, and influenced within the horse-human dyad. Such insights have profound implications for improving equine welfare, optimizing training practices, and advancing the therapeutic use of horses, emphasizing the need for a nuanced and interdisciplinary approach to studying these remarkable animals. This review aims to summarize the prevalence of different methods used to assess horse – human emotional contagion.

2. Materials and Methods

The objective of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the methodologies currently employed to evaluate emotional contagion between humans and horses. Emotional transfer between humans and horses plays a pivotal role in shaping their interactions, influencing behavior, welfare, and performance. This review aims to identify areas of consensus and highlight existing gaps in the evidence base regarding methods for assessing emotional contagion in horse-human interactions.

A systematic literature search was conducted using Google Scholar, Web of Science/Clarivate, Scopus, PubMed, and ScienceDirect. Keywords and search terms included "horse-human interaction," "horse emotional contagion," and "emotional transfer in horses." All articles from 1988 until 2023 that met the inclusion citeria were reviewed. .

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

Studies hypothesizing and investigating horse-human interactions with a focus on emotional arousal in horses.

Studies that provided clear methodologies for measuring horses' emotional states.

Peer-reviewed original research articles published in English

All the articles included are presented in

Appendix A.

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

Studies that did not measure emotional arousal in horses.

Studies that did not examine horse-human interactions.

2.3. Data Collection

The literature search, conducted between March 2023 and January 2024, identified articles relevant to horse-human emotional interactions and methodologies for assessing emotional contagion. References were managed using Zotero, an open-source reference management tool.

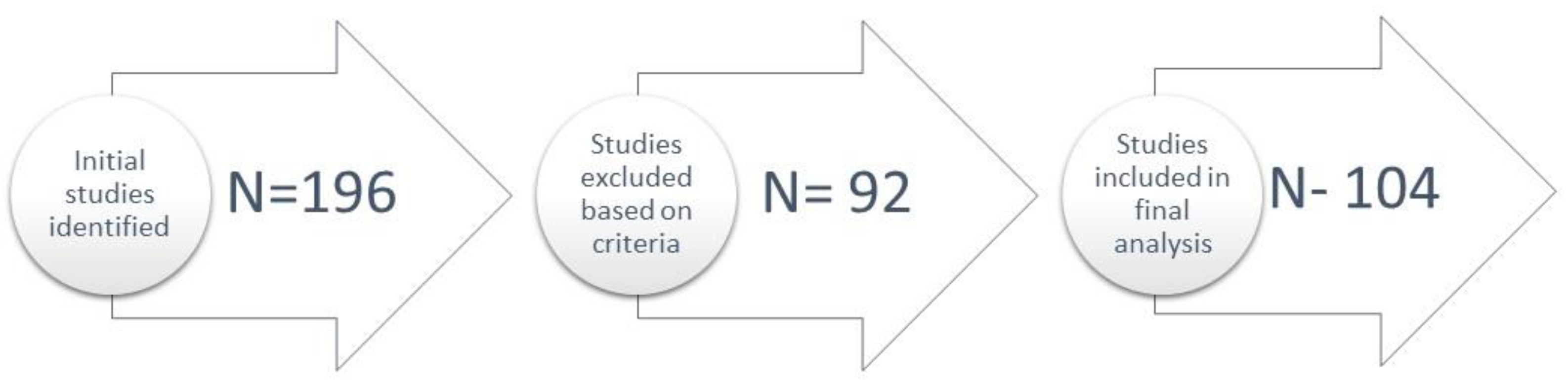

Titles, abstracts, methods, and conclusions of identified articles were screened. Publications were retained if they focused on horse-human relationships and met the inclusion criteria. Studies failing to address horse emotional arousal or horse-human interactions were excluded (

Figure 1).

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

Included studies were systematically analyzed to extract data on methods used to assess horses' emotional states during interactions with humans. Extracted data included the study title, authorship, publication date, behavioral and physiological measures, and key findings as reported by the authors. Data were organized into extraction tables to facilitate comparison and synthesis of methodological approaches.

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Studies Measuring Emotions on Horses Solely or Horses and Humans Concomitently

In this review we introduced a number of 104 studies that met the inclusion criteria. From the studies included 68 focused only on horses (66.02%) whereas 35 (33.98%) examined both horses and humans.

Out of the 35 studies that examined both horses and humans, the distribution of measured parameters is presented in

Table 1.

3.1. Behavioral Responses in Horses

Behavioral responses were predominantly measured through body language (73.1% of studies). Other behavioral measures included facial cues (13.5%) and vocalizations (3.8%). Notably, body language emerged as the most frequently analyzed indicator, given its observable nature and relevance in interpreting emotional states (

Table 2).

The low percentage of studies involving facial cues and vocalizations could reflect the challenges in reliably interpreting these indicators in horses. Facial cues require fine-tuned observational methods, and vocalizations are less common and context-specific in equine behavior.

Table 2.

Frequency and percentage distribution of behavioral indicators observed in horse-human interaction studies. The table presents data on facial cues, body language, and vocalizations across a sample of 104 observations. The results highlight the prevalence of these behavioral responses and their significance in assessing emotional states in horses.

Table 2.

Frequency and percentage distribution of behavioral indicators observed in horse-human interaction studies. The table presents data on facial cues, body language, and vocalizations across a sample of 104 observations. The results highlight the prevalence of these behavioral responses and their significance in assessing emotional states in horses.

| Facial Cues |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

90 |

86.5 |

86.5 |

86.5 |

| Yes |

14 |

13.5 |

13.5 |

100.0 |

| Total |

104 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| Body Language |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

28 |

26.9 |

26.9 |

26.9 |

| Yes |

76 |

73.1 |

73.1 |

100.0 |

| Total |

104 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| Vocalization |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

100 |

96.2 |

96.2 |

96.2 |

| Yes |

4 |

3.8 |

3.8 |

100.0 |

| Total |

104 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

3.2. Physiological Responses in Horses

Physiological responses were primarily measured using heart rate (49%) and heart rate variability (30.8%). Cortisol levels were assessed in about 15% of studies, with variations in the type of cortisol measured (salivary, blood, or fecal). Less common physiological indicators included EEG (1%) and respiration (1.9%) (

Table 3).

Heart rate and HRV, being non-invasive and relatively easy to monitor, were the preferred physiological measures. The infrequent use of EEG and respiration might be attributed to the technical complexity and potential stress induced by these methods during measurement.

Table 3.

Frequency and percentage distribution of physiological indicators used to assess emotional states in horse-human interaction studies. The table presents data on heart rate, heart rate variability (HRV), cortisol levels (including blood, salivary, and fecal cortisol), EEG, and respiration across a sample of 104 observations. The findings illustrate the prevalence of each physiological measure and their role in evaluating stress and emotional responses in horses.

Table 3.

Frequency and percentage distribution of physiological indicators used to assess emotional states in horse-human interaction studies. The table presents data on heart rate, heart rate variability (HRV), cortisol levels (including blood, salivary, and fecal cortisol), EEG, and respiration across a sample of 104 observations. The findings illustrate the prevalence of each physiological measure and their role in evaluating stress and emotional responses in horses.

| Heart Rate |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

53 |

51.0 |

51.0 |

51.0 |

| Yes |

51 |

49.0 |

49.0 |

100.0 |

| Total |

104 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| Heart Rate Variance (HRV) |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

72 |

69.2 |

69.2 |

69.2 |

| Yes |

32 |

30.8 |

30.8 |

100.0 |

| Total |

104 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| Cortisol |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

89 |

85.6 |

85.6 |

85.6 |

| Blood Cortisol |

6 |

5.8 |

5.8 |

91.3 |

| Salivary Cortisol |

8 |

7.7 |

7.7 |

99.0 |

| Fecal Cortisol |

1 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

100.0 |

| Total |

104 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| EEG |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

103 |

99.0 |

99.0 |

99.0 |

| Yes |

1 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

100.0 |

| Total |

104 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| Respiration |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

102 |

98.1 |

98.1 |

98.1 |

| Yes |

2 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

100.0 |

| Total |

104 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

3.3. Comparison and Overlap in Measures (Horses)

A significant number of studies (approximately 76.5%) that measured heart rate also assessed body language. This suggests that combining behavioral and physiological responses enhances the reliability of emotional assessments.

Of all the studies examining body language, more than half of them also examine the heart rate of its subjects (n=39), while about 29% examine HRV as well (n=22). Vocalization (n=2) and facial ques (n=2) are involved in a lower number of the studies. Similarly, EEG (n=1) and respiration are (n=2) also less mentioned. Cortisol has a high count of mentions (

Table 4).

All the studies that examine vocalization also examine body language (n=4). Half of them also examine heart rate (n=2) (

Table 5)

77% of studies measuring heart rate, also involve the analysis of body language (n=39). While 53% analyze HRV as well (n=27) (

Table 6)

A large majority of studies examining HRV (n=32) also examine heart rate as well (n=27). While, body language is also examined in 69% of the studies examining HRV (n=22) (

Table 7).

All studies looking at fecal cortisol also analyze the body language and EEG of its subjects (n=1). Further, 4 studies involving blood cortisol also involve body language, while tree involve heart rate. In the case of salivary cortisol, 6 involve body language and 5 involve heart rate. 3 studies measuring Heart Rate Variance also measure Blood Cortisol, while another 3 measure salivary cortisol (

Table 8,

Table 9).

The only study measuring EEG also measures body language (

Table 10).

The two studies that focus on respiration also involve body language and heart rate (

Table 11).

3.4. Correlations

A positive correlation was observed between heart rate and HRV (r = 0.47, p < 0.001), indicating that studies often measure these indicators together to understand autonomic nervous system responses. In contrast, a negative correlation was found between body language and facial cues (r = -0.52, p < 0.001), implying that studies focusing on one are less likely to focus on the other (

Table 12).

3.5. Other Methods

Other methods were less frequently used (

Table 13).

4. Discussion

The findings highlight the importance of a multi-faceted approach in evaluating horse emotions. While body language remains the cornerstone of behavioral analysis, physiological measures like heart rate and HRV add robustness to the interpretation of emotional states. The limited use of facial cues and vocalizations suggests that further research is needed to develop standardized protocols for these indicators.

Moreover, the low prevalence of studies using EEG and respiration underscores the need for innovative, non-invasive technologies that can provide deeper insights into equine neurophysiology without inducing stress. Future research could focus on integrating wearable technologies and AI-driven analysis for real-time monitoring of both behavioral and physiological responses.

Current methodologies however have several limitations of both physiological and behavioral indicators including observer bias in behavioral assessments or environmental and contextual factors affecting physiological markers, as for example hormonal fluctuation in mares throughout their cycle. Longitudinal studies might bring more light in assessing emotional contagion over time.

Out of the 35 studies that examined both horses and humans, the distribution of measured parameters suggests that while heart rate and HRV remain the predominant physiological measures, facial expressions and body language are also significant areas of study. However, hormonal and neurophysiological measurements are less commonly explored, presenting potential gaps for further research in horse-human interaction studies.

The process of emotion contagion between horses and humans is central to equine welfare, training, and therapy. The statistical interpretation of the studies indicates that only 33.98% of research includes both horse and human physiological and behavioral responses, highlighting a research gap in understanding the bidirectional influence of human emotions on horses. Studies demonstrate that human emotions such as stress, relaxation, and emotional states can influence a horse’s physiological responses, supporting the concept of emotional co-regulation between the two species [

25,

26]. Horses appear to interpret human facial expressions and vocal tones, responding more positively to calm and happy expressions while showing stress-related responses to negative cues [

27]. The way a human approaches and interacts with a horse significantly affects equine behavioral responses, suggesting that non-verbal cues play a vital role in establishing trust and communication [

11,

28,

29]. Despite the importance of cortisol levels and EEG readings in assessing stress and arousal, only a small portion of studies have examined these markers in both horses and humans simultaneously.

5. Conclusions

The systematic review underscores the complexity of horse-human emotional contagion and the necessity for holistic assessment methods. Behavioral indicators, especially body language, dominate current research, but physiological responses offer critical, objective validation. Combining these approaches will be pivotal in advancing our understanding of equine emotions, improving training practices, and enhancing horse welfare.

Future studies should aim to bridge the gap between behavioral and physiological measures by exploring underutilized indicators like EEG and respiration. Additionally, efforts should be made to establish standardized guidelines for measuring and interpreting both types of responses, ultimately fostering a more empathetic and scientifically informed approach to horse care and management.

Given the bidirectional nature of emotional transfer, future research should focus on the development of standardized methodologies to quantify human-horse emotional interactions more accurately. Advances in wearable technology, AI-driven analysis, and interdisciplinary research will be key to deepening our understanding of how human emotions shape equine experiences and behaviors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T. and M.D.; methodology, Z.D.; validation C.C. , formal analysis, D.M.; investigation, M.T.; resources, C.C..; data curation, M.T. and D.M..; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.; writing—review and editing, D.M.; visualization, Z.D.; supervision, C.C.; project administration, C.C.; funding acquisition, C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HR |

Heart rate |

| HRV |

Heart rate variability |

| EEG |

electroencephalogram |

|

|

Appendix A

Appendix A.1 Comprehensive List of Referenced Studies

This appendix includes a detailed table of all the studies cited and analyzed in this review article. The table categorizes each study by its authorship, year of publication, and the specific behavioral or physiological parameters investigated. These parameters include aspects such as **facial cues, body language, vocalization, heart rate, heart rate variability (HRV), cortisol levels, EEG patterns, respiratory responses**, and other metrics.

The purpose of this appendix is to provide readers with a clear and accessible summary of the research base underpinning our findings. Each entry allows for a quick identification of the studies that explore specific response types or methodologies, aiding in transparency and facilitating further research by others in the field.

For studies where data on certain parameters are not provided, the corresponding cells are left blank. Special abbreviations (e.g., XB, XS, BH, Q, etc.) indicate additional relevant details, which are elaborated upon in the main text.

| |

|

|

BEHAVIORAL RESPONSES |

PHYSIOLOGICAL RESPONSES |

|

| No. |

AUTHORS |

YEAR |

FACIAL CUES |

BODY LANGUAGE |

VOCALIZATION |

HEART RATE |

HRV |

CORTISOL |

EEG |

RESPIRATION |

OTHER |

| 1 |

Anderson et.al. [30] |

1999 |

|

X |

|

|

|

XB |

|

|

BH |

| 2 |

Austin and Rogers [31] |

2007 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3 |

Baba et.al. [11] |

2019 |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4 |

Baragli et al. [32] |

2014 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

| 5 |

Baragli et al. [33] |

2009 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

| 6 |

Baragli et al. [34] |

2011 |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| 7 |

Becker-Birck et al. [14] |

2013 |

|

|

|

X |

X |

XB |

|

|

|

| 8 |

Birke et al [35] |

2011 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 9 |

Bornmann et al. [36] |

2021 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Q |

| 10 |

Brandt [28] |

2004 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Q |

| 11 |

Cavanaghn [37] |

2017 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 12 |

Chamove et.al. [38] |

2002 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 13 |

Chapman et.al. [39] |

2020 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Q |

| 14 |

Christensen et al. [40] |

2012 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

XF |

|

|

|

| 15 |

Christensen et.al. [41] |

2005 |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

16

|

Contreras Aquilar et.al. [16] |

2019 |

|

X |

|

|

|

XS |

|

|

SM |

| 17 |

Corujo et.al. [24] |

2021 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 18 |

Cravana et.al. [42] |

2021 |

|

|

|

X |

|

XB |

|

|

BH |

| 19 |

Dalla Costa et.al. [43] |

2017 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 20 |

dIngeo et al. [44] |

2019 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

| 21 |

Drinkhouse et.al. [45] |

2012 |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| 22 |

Duclugosz et al. [46] |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

XS |

|

|

|

| 23 |

Dyson et.al. [47] |

2021 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Q |

| 24 |

Farmer et.al. [48] |

2010 |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 25 |

Feighelstein et.al. [20] |

2023 |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

AI |

| 26 |

Fejsakova et al. [49] |

2013 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

XS |

|

|

|

| 27 |

Felici et al. [50] |

2023 |

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

| 28 |

Fureix et al. [51] |

2012 |

|

X |

|

|

|

XB |

|

|

|

| 29 |

Gerhke et.al. [52] |

2011 |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

| 30 |

Gleerup et al. [53] |

2015 |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 31 |

Guidi et.al. [54] |

2016 |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

| 32 |

Hama et.al. [55] |

1996 |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

x2 |

| 33 |

Hausberger and Muller [13] |

2002 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 34 |

Hintze et al. [56] |

2016 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 35 |

Hintze et al. [57] |

2017 |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

EW |

| 36 |

Hockenhull and Creighton [58] |

2013 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Q |

| 37 |

Hockenhull et.al. [21] |

2015 |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| 38 |

Hotzel et.al. [59] |

2019 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Q |

| 39 |

Ijichi et.al. [60] |

2023 |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

IRT |

| 40 |

Ijichi et.al. [61] |

2018 |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

IRT |

| 41 |

Ille et al. [62] |

2014 |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

| 42 |

J. W., C et.al. [63] |

2008 |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| 43 |

Janczarek et.al. [64] |

2019 |

|

X |

|

X |

|

XS |

|

|

|

| 44 |

Janczarek et.al. [65] |

2018 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

| 45 |

Kaiser et.al. [66] |

2006 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 46 |

Keeling et.al. [67] |

2009 |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

x2 |

| 47 |

Kim and Yoon [68] |

2022 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BH |

| 48 |

Konig et.al. [69] |

2011 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

| 49 |

Kosiara and Harrison [70] |

2021 |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

| 50 |

Kowalik et al. [71] |

2017 |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

| 51 |

Lanata et.al. [22] |

2016 |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

| 52 |

Lanata et.al. [72] |

2018 |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

ODOUR |

| 53 |

Lansade and Bouissou [10] |

2008 |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| 54 |

Lansade et.al. [27] |

2018 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

BH |

| 55 |

Lansade et.al. [73] |

2020 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 56 |

Lee et al. [5] |

2021 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

| 57 |

Leiner and Fendt [74] |

2011 |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| 58 |

Lie [75] |

2017 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 59 |

Lloyd et.al. [76] |

2007 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Q |

| 60 |

Lundberg et.al. [29] |

2020 |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| 61 |

Lundblad [77] |

2018 |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| 62 |

Maros et.al. [78] |

2008 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 63 |

McBride et al. [79] |

2022 |

X |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

EYE BLINK |

| 64 |

McCann et.al. [80] |

1988 |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

| 65 |

McGreevy et.al. [9] |

2009 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 66 |

Merkies et al. [81] |

2022 |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| 67 |

Merkies et.al. [82] |

2014 |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

x2 |

| 68 |

Merkies et.al. [83] |

2019 |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

EYE BLINK |

| 69 |

Momozawa et.al. [84] |

2005 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Q |

| 70 |

Mott et al. [85] |

2020 |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

EYE BLINK |

| 71 |

Mullard et.al. [86] |

2017 |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 72 |

Nakamura et.al. [87] |

2018 |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 73 |

Noble et.al. [88] |

2013 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

XB |

|

|

|

| 74 |

Norton et al. [19] |

2018 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

| 75 |

Pereira et.al. [89] |

2023 |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

BH |

| 76 |

Perez Manrique et al. [90] |

2019 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

| 77 |

Pierard et.al. [17] |

2019 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Q |

| 78 |

Popescu et.al. [91] |

2013 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Q |

| 79 |

Reid et al. [92] |

2017 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

| 80 |

Rietmann et al. [93] |

2004 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

| 81 |

Rorvang et.al. [94] |

2015 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

| 82 |

Sabiniewicz et.al. [95] |

2020 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

ODOUR |

| 83 |

Sankey et al. [96] |

2010 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

| 84 |

Sauer et.al. [97] |

2019 |

|

X |

|

|

|

XB |

|

|

BH |

| 85 |

Schmidt et al. [15] |

2010 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

XS |

|

|

|

| 86 |

Schrimpf et.al. [26] |

2020 |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 87 |

Schutz and Schmitz [98] |

2021 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 88 |

Scopa et.al. [99] |

2020 |

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

| 89 |

Seaman et.al. [100] |

2002 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 90 |

Siipola et.al. [101] |

2019 |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| 91 |

Smith et. al. [25] |

2018 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 92 |

Squibb et al. [102] |

2018 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

IRT |

| 93 |

Stomp et.al. [103] |

2018 |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

POSITIVE EM |

| 94 |

Trosch et.al. [104] |

2020 |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| 95 |

Valera et.al. [23] |

2012 |

|

|

|

|

|

XS |

|

|

IRT |

| 96 |

Visser et al. [105] |

2008 |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| 97 |

Visser et.al. [4] |

2002 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

| 98 |

von Borstel et al. [106] |

2007 |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

| 99 |

von Lewinski et al. [107] |

2013 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

XS |

|

|

|

| 100 |

Wathan et al. [12] |

2015 |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 101 |

Wathan et al. [108] |

2016 |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 102 |

Wilk and Janczarek [109] |

2015 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

| 103 |

Wolff et.al. [110] |

1997 |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 104 |

Young et al. [111] |

2012 |

|

X |

|

X |

|

XS |

|

|

|

| XB – Blood Cortisol, XS – Salivary Cortisol, XF – Fecal (Faeces) Biomarkers, IRT – Infrared Thermography, BH – Blood Hormones, Q – Questionnaires, x2 – Studies Conducted in Both Humans and Horses, AI – Artificial Intelligence Applications, SM – Other Salivary Metabolites. |

References

- Darwin, C. (1859). On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. John Murray.

- Panksepp, J. (1994). The clearest physiological distinctions between emotions emerge in the analysis of the brain sources of arousal. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 18, 435–445. [CrossRef]

- Rolls, E. T. (1999). The Brain and Emotion. Oxford University Press.

- Visser, E. K. , Van Reenen, C. G., Hopster, H., Schilder, M. B., Knaap, J. H., Barneveld, A., Blokhuis, H. J. (2002). Quantifying aspects of young horses’ temperament: Consistency of behavioral variables. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 77, 33–48. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C., Verbeek, E., Doyle, R., Bateson, M. (2021). Attention bias to threat in sheep is modulated by affective state. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 8, 643152. [CrossRef]

- Bekoff, M. (2000). Animal emotions: Exploring passionate natures. BioScience, 50, 861–870. [CrossRef]

- Porges, S. W. (2007). The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology, 74, 116–143. [CrossRef]

- Nakahashi, W. , Ohtsuki, H. (2018). Evolution of emotion-driven punishment and cooperation in social dilemmas. Scientific Reports, 8, 189. [CrossRef]

- McGreevy, P. , McLean, A., Buckley, P., McConaghy, F., McLean, C. (2009). How riding may affect welfare: What the equine veterinarian needs to know. Equine Veterinary Journal, 41, 565–573. [CrossRef]

- Lansade, L. , Bouissou, M. F., Erhard, H. W. (2008). Fearfulness in horses: A temperament trait stable across time and situations. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 115, 182–200. [CrossRef]

- Baba, K. , Kawai, N., Fujita, K. (2019). Horses (Equus caballus) categorize human emotions cross-modally based on facial expression and voice tone. Scientific Reports, 9, 16200. [CrossRef]

- Wathan, J., Proops, L., Grounds, K., McComb, K. (2015). Horses discriminate between facial expressions of conspecifics. Scientific Reports, 5, 14336. [CrossRef]

- Hausberger, M. , Gautier, E., Biquand, V., Lunel, C., Jégo, P. (2002). Could work be a source of behavioural disorders? A study in horses. PLoS ONE, 12, e0176125. [CrossRef]

- Becker-Birck, M., Schmidt, A., Wulf, M., Aurich, J., Möstl, E., Aurich, C. (2013). Cortisol release and heart rate variability in sport horses participating in equestrian competitions. The Veterinary Journal, 197, 318–322. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A., Möstl, E., Wehnert, C., Aurich, J., Müller, J., Aurich, C. (2010). Cortisol release and heart rate variability in horses during road transport. Hormones and Behavior, 57, 209–215. [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Aguilar, M. D. , Bertal, M., Martos, L., Lopez-Arjona, M., Escribano, D., Cerón, J. J. (2019). Salivary alpha-amylase activity and protein concentration in horses: A pilot study. Research in Veterinary Science, 122, 293–295. [CrossRef]

- Pierard, C. , Liscia, M., Valle, A. L., Colson, V. (2019). Horse heart rate variability and its regulation by the autonomic nervous system: A review. Physiology & Behavior, 207, 122–130. [CrossRef]

- Dalla Costa, E. , Dai, F., Lebelt, D., Scholz, P., Barbieri, S., Canali, E., Minero, M. (2017). Welfare assessment of horses: The AWIN approach. Animals, 7, 41. [CrossRef]

- Norton, J. N. , Kinzig, K. P., Aylor, D. L. (2018). Measuring stress in animal models: How, why and what to avoid. ILAR Journal, 59, 174–193. [CrossRef]

- Feighelstein, M. , Pruvost, J., Henry, S., Hausberger, M. (2023). Emotional reactions to humans in horses: The effect of negative versus positive handling. Animal Behaviour, 198, 149–160. [CrossRef]

- Hockenhull, J., Creighton, E., Waran, N., McGreevy, P. (2015). The use of positive reinforcement in horse training. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 10, 297–307. [CrossRef]

- Lanata, A., Scilingo, E. P., Nardelli, M., Greco, A., Valenza, G. (2016). Complexity analysis of heart rate variability in horses during sleep. Physiological Measurement, 37, 1678–1691. [CrossRef]

- Valera, M., Bartolomé, E., Sánchez, M. J., Molina, A., Gallardo, L., Lupiáñez, J., Fernández, A. (2012). Effect of training and competition on heart rate variability in show jumping horses. Equine Veterinary Journal, 44, 195–201. [CrossRef]

- Corujo, A. , Sarabia, J. A., Garcés-Narro, C., Cavero-Redondo, I., Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. (2021). Equine-assisted therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51, 2197–2213. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M. K; Friend, T. H; Evans, J. W; Bushong, D. M. 1999. Behavioral assessment of horses in therapeutic riding programs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 631, 11–24. [CrossRef]

- Austin, N. P; Rogers, L. J. 2007. Asymmetry of flight and escape turning responses in horses. Laterality: Asymmetries of Body, Brain and Cognition, 125, 464–474. [CrossRef]

- Baragli, P; Gazzano, A; Martelli, F; ; Sighieri, C. 2009. How Do Horses Appraise Humans’ Actions? A Brief Note over a Practical Way to Assess Stimulus Perception. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 2910, 739–742. [CrossRef]

- Baragli, P; Mariti, C; Petri, L; De Giorgio, F; ; Sighieri, C. 2011. Does attention make the difference? Horses’ response to human stimulus after 2 different training strategies. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 61, 31–38. [CrossRef]

- Baragli, P; Vitale, V; Banti, L; ; Sighieri, C. 2014. Effect of aging on behavioural and physiological responses to a stressful stimulus in horses Equus caballus. Behaviour, 15111, 1513–1533. [CrossRef]

- Birke, L; Hockenhull, J; Creighton, E; Pinno, L; Mee, J; ; Mills, D. 2011. Horses’ responses to variation in human approach. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 1341–2, 56–63. [CrossRef]

- Bornmann, T; Randle, H; ; Williams, J. 2021. Investigating Equestrians’ Perceptions of Horse Happiness: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 104, 103697. [CrossRef]

- Brandt, K. 2004. A Language of Their Own: An Interactionist Approach to Human-Horse Communication. Society ; Animals, 124, 299–316. [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, C. E. P. n.d. . Recognition of Human Facial Expressions of Emotion in the Domestic Horse Equus caballus. 53.

- Chamove, A. S; Crawley-Hartrick, O. J. E; Stafford, K. J. 2002. Horse reactions to human attitudes and behavior. Anthrozoös, 154, 323–331. [CrossRef]

- Chapman, M; Thomas, M; ; Thompson, K. 2020. What People Really Think About Safety around Horses: The Relationship between Risk Perception, Values and Safety Behaviours. Animals, 1012, 2222. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J. W; Ahrendt, L. P; Lintrup, R; Gaillard, C; Palme, R; ; Malmkvist, J. 2012. Does learning performance in horses relate to fearfulness, baseline stress hormone, and social rank? Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 1401–2, 44–52. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J. W; Keeling, L. J; Nielsen, B. L. 2005. Responses of horses to novel visual, olfactory and auditory stimuli. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 931–2, 53–65. [CrossRef]

- Cravana, C; Fazio, E; Ferlazzo, A; ; Medica, P. 2021. Therapeutic Riding Horses: Using a hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis measure to assess the physiological stress response to different riders. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 46, 18–23. [CrossRef]

- Dalla Costa, E; Bracci, D; Dai, F; Lebelt, D; ; Minero, M. 2017. Do Different Emotional States Affect the Horse Grimace Scale Score? A Pilot Study. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 54, 114–117. [CrossRef]

- d’Ingeo, S; Quaranta, A; Siniscalchi, M; Stomp, M; Coste, C; Bagnard, C; Hausberger, M; ; Cousillas, H. 2019. Horses associate individual human voices with the valence of past interactions: A behavioural and electrophysiological study. Scientific Reports, 91, 11568. [CrossRef]

- Drinkhouse, M; Birmingham, S. S; Fillman, R; ; Jedlicka, H. 2012. Correlation of Human and Horse Heart Rates During Equine-Assisted Therapy Sessions with At-Risk Youths: A Pilot Study. Journal of Student Research, 13, 22–25. [CrossRef]

- Długosz, B; Próchniak, T; Stefaniuk-Szmukier, M; Basiaga, M; Łuszczyńśki, J; ; Pieszka, M. n.d.. Assessment of changes in the saliva cortisol level of horses during different ways in recreational exploitation. Turk J Vet Anim Sci, 6.

- Dyson, S; Bondi, A; Routh, J; Pollard, D; Preston, T; McConnell, C; ; Kydd, J. 2022. Do owners recognise abnormal equine behaviour when tacking-up and mounting? A comparison between responses to a questionnaire and real-time observations. Equine Veterinary Education, 349. [CrossRef]

- Farmer, K; Krueger, K; ; Byrne, R. W. 2010. Visual laterality in the domestic horse Equus caballus interacting with humans. Animal Cognition, 132, 229–238.

- Fejsáková, M; Kottferová, J; Dankulincová, Z; Haladová, E; Matos, R; ; Miňo, I. 2013. Some possible factors affecting horse welfare assessment. Acta Veterinaria Brno, 824, 447–451. [CrossRef]

- Felici, M; Reddon, A. R; Maglieri, V; Lanatà, A; ; Baragli, P. 2023. Heart and brain: Change in cardiac entropy is related to lateralised visual inspection in horses. PloS one, 188, e0289753.

- Fureix, C; Jego, P; Henry, S; Lansade, L; ; Hausberger, M. 2012. Towards an Ethological Animal Model of Depression? A Study on Horses. PLoS ONE, 76, e39280. [CrossRef]

- Gehrke, E. K; Baldwin, A; ; Schiltz, P. M. 2011. Heart Rate Variability in Horses Engaged in Equine-Assisted Activities. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 312, 78–84. [CrossRef]

- Gleerup, K. B; Forkman, B; Lindegaard, C; ; Andersen, P. H. 2015. An equine pain face. Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia, 421, 103–114. [CrossRef]

- Guidi, A; Lanata, A; Baragli, P; Valenza, G; ; Scilingo, E. 2016. A Wearable System for the Evaluation of the Human-Horse Interaction: A Preliminary Study. Electronics, 54, 63. [CrossRef]

- Hama, H; Yogo, M; ; Matsuyama, Y. 1996. Effects of stroking horses on both humans’ and horses’ heart rate responses. Japanese Psychological Research, 382, 66–73. [CrossRef]

- Hintze, S; Murphy, E; Bachmann, I; Wemelsfelder, F; ; Würbel, H. 2017. Qualitative Behaviour Assessment of horses exposed to short-term emotional treatments. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 196, 44–51. [CrossRef]

- Hintze, S; Smith, S; Patt, A; Bachmann, I; ; Würbel, H. 2016. Are Eyes a Mirror of the Soul? What Eye Wrinkles Reveal about a Horse’s Emotional State. PLOS ONE, 1110, e0164017. [CrossRef]

- Hockenhull, J; ; Creighton, E. 2013. Training horses: Positive reinforcement, positive punishment, and ridden behavior problems. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 84, 245–252. [CrossRef]

- Hötzel, M. J; Vieira, M. C; Leme, D. P. 2019. Exploring horse owners’ and caretakers’ perceptions of emotions and associated behaviors in horses. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 29, 18–24. [CrossRef]

- Ijichi, C; Griffin, K; Squibb, K; ; Favier, R. 2018. Stranger danger? An investigation into the influence of human-horse bond on stress and behaviour. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 206, 59–63. [CrossRef]

- Ijichi, C; Wilkinson, A; Riva, M. G; Sobrero, L; ; Dalla Costa, E. 2023. Work it out: Investigating the effect of workload on discomfort and stress physiology of riding school horses. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 267, 106054. [CrossRef]

- Ille, N; Erber, R; Aurich, C; ; Aurich, J. 2014. Comparison of heart rate and heart rate variability obtained by heart rate monitors and simultaneously recorded electrocardiogram signals in nonexercising horses. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 96, 341–346. [CrossRef]

- J. W; C; Malmkvist, J; Nielsen, B. L; ; Keeling, L. J. 2008. Effects of a calm companion on fear reactions in naive test horses. Equine Veterinary Journal, 401, 46–50. [CrossRef]

- Janczarek, I; Stachurska, A; Wilk, I; Krakowski, L; Przetacznik, M; Zastrzeżyńska, M; ; Kuna-Broniowska, I. 2018. Emotional excitability and behaviour of horses in response to stroking various regions of the body. Animal Science Journal, 8911, 1599–1608. [CrossRef]

- Janczarek, I; Wilk, I; Stachurska, A; Krakowski, L; ; Liss, M. 2019. Cardiac activity and salivary cortisol concentration of leisure horses in response to the presence of an audience in the arena. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 29, 31–39. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, L; Heleski, C. R; Siegford, J; ; Smith, K. A. 2006. Stress-related behaviors among horses used in a therapeutic riding program. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 2281, 39–45. [CrossRef]

- Jonare, L (Ed.) Keeling, L. J; Jonare, L; ; Lanneborn, L. 2009. Investigating horse–human interactions: The effect of a nervous human. The Veterinary Journal, 1811, 70–71. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J; ; Yoon, M. 2022. The effect of serotonin and oxytocin on equine docility and friendliness to humans. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 50, 18–22. [CrossRef]

- König von Borstel, U; Euent, S; Graf, P; König, S; ; Gauly, M. 2011. Equine behaviour and heart rate in temperament tests with or without rider or handler. Physiology ; Behavior, 1043, 454–463. [CrossRef]

- Kosiara, S; ; Harrison, A. P. 2021. The Effect of Aromatherapy on Equine Facial Expression, Heart Rate, Respiratory Tidal Volume and Spontaneous Muscle Contractures in M. Temporalis and M. Cleidomastoideus. Open Journal of Veterinary Medicine, 1102, 87–103. [CrossRef]

- Kowalik, S; Janczarek, I; Kędzierski, W; Stachurska, A; ; Wilk, I. 2017. The effect of relaxing massage on heart rate and heart rate variability in purebred Arabian racehorses: Massage and HRV in Horses. Animal Science Journal, 884, 669–677. [CrossRef]

- Lanata, A; Nardelli, M; Valenza, G; Baragli, P; DrAniello, B; Alterisio, A; Scandurra, A; Semin, G. R; ; Scilingo, E. P. 2018. A Case for the Interspecies Transfer of Emotions: A Preliminary Investigation on How Humans Odors Modify Reactions of the Autonomic Nervous System in Horses. 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society EMBC, 522–525. [CrossRef]

- Lansade, L; Colson, V; Parias, C; Reigner, F; Bertin, A; ; Calandreau, L. 2020. Human Face Recognition in Horses: Data in Favor of a Holistic Process. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 575808. [CrossRef]

- Lansade, L; Nowak, R; Lainé, A.-L; Leterrier, C; Bonneau, C; Parias, C; ; Bertin, A. 2018. Facial expression and oxytocin as possible markers of positive emotions in horses. Scientific Reports, 81, 14680. [CrossRef]

- Leiner, L; ; Fendt, M. 2011. Behavioural fear and heart rate responses of horses after exposure to novel objects: Effects of habituation. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 1313–4, 104–109.

- Lie, M. R. 2017. Emotional Contagion and Mimicry of Behavior between Horses and their Handlers Master's thesis, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Ås.

- Lloyd, A. S; Martin, J. E; Bornett-Gauci, H. L. I; Wilkinson, R. G. 2007. Evaluation of a novel method of horse personality assessment: Rater-agreement and links to behaviour. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 1051–3, 205–222. [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, P; Hartmann, E; ; Roth, L. S. V. 2020. Does training style affect the human-horse relationship? Asking the horse in a separation–reunion experiment with the owner and a stranger. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 233, 105144. [CrossRef]

- Lundblad, J. n.d. . Changes in facial expressions during short term emotional stress as described by a Facial Action Coding System in horses.

- Maros, K; Gácsi, M; ; Miklósi, Á. 2008. Comprehension of human pointing gestures in horses Equus caballus. Animal Cognition, 113, 457–466. [CrossRef]

- McBride, S. D; Roberts, K; Hemmings, A. J; Ninomiya, S; ; Parker, M. O. 2022. The impulsive horse: Comparing genetic, physiological and behavioral indicators to those of human addiction. Physiology ; Behavior, 254, 113896. [CrossRef]

- McCann, J. S; Heird, J. C; Bell, R. W; Lutherer, L. O. 1988. Normal and more highly reactive horses. I. Heart rate, respiration rate and behavioral observations. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 193–4, 201–214. [CrossRef]

- Merkies, K; Sudarenko, Y; ; Hodder, A. J. 2022. Can Ponies Equus Caballus Distinguish Human Facial Expressions?. Animals, 1218, 2331.

- Merkies, K; Sievers, A; Zakrajsek, E; MacGregor, H; Bergeron, R; ; von Borstel, U. K. 2014. Preliminary results suggest an influence of psychological and physiological stress in humans on horse heart rate and behavior. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 95, 242–247. [CrossRef]

- Merkies, Ready, Farkas, ; Hodder. 2019. Eye Blink Rates and Eyelid Twitches as a Non-Invasive Measure of Stress in the Domestic Horse. Animals, 98, 562. [CrossRef]

- Momozawa, Y; Kusunose, R; Kikusui, T; Takeuchi, Y; ; Mori, Y. 2005. Assessment of equine temperament questionnaire by comparing factor structure between two separate surveys. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 921–2, 77–84. [CrossRef]

- Mott, R. O; Hawthorne, S. J; McBride, S. D. 2020. Blink rate as a measure of stress and attention in the domestic horse Equus caballus. Scientific Reports, 101, 21409. [CrossRef]

- Mullard, J; Berger, J. M; Ellis, A. D; ; Dyson, S. 2017. Development of an ethogram to describe facial expressions in ridden horses FEReq. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 18, 7–12. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K; Takimoto-Inose, A; ; Hasegawa, T. 2018. Cross-modal perception of human emotion in domestic horses Equus caballus. Scientific Reports, 81, 8660. [CrossRef]

- Noble, G. K; Blackshaw, K. L; Cowling, A; Harris, P. A; ; Sillence, M. N. 2013. An objective measure of reactive behaviour in horses. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 1443–4, 121–129. [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Figueiredo, I. , Rosa, I., & Sancho Sanchez, C. (2024). Forced Handling Decreases Emotionality but Does Not Improve Young Horses’ Responses toward Humans and their Adaptability to Stress. Animals, 14(5), 784.

- Pérez Manrique, L; Hudson, R; Bánszegi, O; ; Szenczi, P. 2019. Individual differences in behavior and heart rate variability across the preweaning period in the domestic horse in response to an ecologically relevant stressor. Physiology ; Behavior, 210, 112652. [CrossRef]

- Popescu, S; Diugan, E. A; ; Spinu, M. 2014. The interrelations of good welfare indicators assessed in working horses and their relationships with the type of work. Research in Veterinary Science, 962, 406–414. [CrossRef]

- Reid, K; Rogers, C. W; Gronqvist, G; Gee, E. K; ; Bolwell, C. F. 2017. Anxiety and pain in horses measured by heart rate variability and behavior. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 22, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Rietmann, T. R; Stuart, A. E. A; Bernasconi, P; Stauffacher, M; Auer, J. A; ; Weishaupt, M. A. 2004. Assessment of mental stress in warmblood horses: Heart rate variability in comparison to heart rate and selected behavioural parameters. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 881–2, 121–136. [CrossRef]

- Rørvang, M. V; Ahrendt, L. P; Christensen, J. W. 2015. A trained demonstrator has a calming effect on naïve horses when crossing a novel surface. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 171, 117–120. [CrossRef]

- Sabiniewicz, A; Tarnowska, K; Świątek, R; Sorokowski, P; ; Laska, M. 2020. Olfactory-based interspecific recognition of human emotions: Horses Equus ferus caballus can recognize fear and happiness body odour from humans Homo sapiens. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 230, 105072. [CrossRef]

- Sankey, C; Richard-Yris, M.-A; Henry, S; Fureix, C; Nassur, F; ; Hausberger, M. 2010. Reinforcement as a mediator of the perception of humans by horses Equus caballus. Animal Cognition, 135, 753–764. [CrossRef]

- Sauer, F. J; Hermann, M; Ramseyer, A; Burger, D; Riemer, S; ; Gerber, V. 2019. Effects of breed, management and personality on cortisol reactivity in sport horses. PLOS ONE, 1412, e0221794. [CrossRef]

- Schrimpf, A; Single, M.-S; ; Nawroth, C. 2020. Social Referencing in the Domestic Horse. Animals, 101, 164. [CrossRef]

- Schütz, K; ; Schmitz, J. 2021. Positive and Negative Affects in Horse-assisted Coachings. Coaching | Theorie ; Praxis, 71, 25–33. [CrossRef]

- Scopa, C; Greco, A; Contalbrigo, L; Fratini, E; Lanatà, A; Scilingo, E. P; ; Baragli, P. 2020. Inside the Interaction: Contact With Familiar Humans Modulates Heart Rate Variability in Horses. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7, 582759. [CrossRef]

- Seaman, S. C; Davidson, H. P. B; Waran, N. K. 2002. How reliable is temperament assessment in the domestic horse Equus caballus? Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 782–4, 175–191. [CrossRef]

- Siipola, A.-K. S; Stefánsdóttir, G. J; Ragnarsson, S. n.d. . Heart Rates in Familiar and Unfamiliar Pairs of Young Horses and Their Riders.

- Smith, A. V; Proops, L; Grounds, K; Wathan, J; ; McComb, K. 2016. Functionally relevant responses to human facial expressions of emotion in the domestic horse Equus caballus. Biology Letters, 122, 20150907. [CrossRef]

- Squibb, K; Griffin, K; Favier, R; ; Ijichi, C. 2018. Poker Face: Discrepancies in behaviour and affective states in horses during stressful handling procedures. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 202, 34–38. [CrossRef]

- Stomp, M; Leroux, M; Cellier, M; Henry, S; Lemasson, A; ; Hausberger, M. 2018. An unexpected acoustic indicator of positive emotions in horses. PLOS ONE, 137, e0197898. [CrossRef]

- Trösch, M; Pellon, S; Cuzol, F; Parias, C; Nowak, R; Calandreau, L; ; Lansade, L. 2020. Horses feel emotions when they watch positive and negative horse–human interactions in a video and transpose what they saw to real life. Animal Cognition, 234, 643–653. [CrossRef]

- Visser, E. K; Van Reenen, C. G; Blokhuis, M. Z; Morgan, E. K. M; Hassmén, P; Rundgren, T. M. M; ; Blokhuis, H. J. 2008. Does Horse Temperament Influence Horse–Rider Cooperation? Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 113, 267–284. [CrossRef]

- von Borstel, U. U; Duncan, I. J. H; Shoveller, A. K; Merkies, K; Keeling, L. J; ; Millman, S. T. 2009. Impact of riding in a coercively obtained Rollkur posture on welfare and fear of performance horses. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 1162–4, 228–236. [CrossRef]

- von Lewinski, M; Biau, S; Erber, R; Ille, N; Aurich, J; Faure, J.-M; Möstl, E; ; Aurich, C. 2013. Cortisol release, heart rate and heart rate variability in the horse and its rider: Different responses to training and performance. The Veterinary Journal, 1972, 229–232. [CrossRef]

- Wathan, J; Proops, L; Grounds, K; ; McComb, K. 2016. Horses discriminate between facial expressions of conspecifics. Scientific Reports, 61, 38322. [CrossRef]

- Wilk, I; ; Janczarek, I. 2015. Relationship between behavior and cardiac response to round pen training. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 103, 231–236. [CrossRef]

- Wolff, A; Hausberger, M; ; Le Scolan, N. 1997. Experimental tests to assess emotionality in horses. Behavioural Processes, 403, 209–221. [CrossRef]

- Young, T; Creighton, E; Smith, T; ; Hosie, C. 2012. A novel scale of behavioural indicators of stress for use with domestic horses. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 1401–2, 33–43. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Phases of the study.

Figure 1.

Phases of the study.

Table 1.

The distribution of measured parameters in 35 studies that examined both horses and humans during interaction.

Table 1.

The distribution of measured parameters in 35 studies that examined both horses and humans during interaction.

| Measurement Type |

Percentage (%) |

Description |

| Heart Rate (HR) and HRV |

28.57% |

Studies focused on physiological parameters such as heart rate and heart rate variability, indicating a strong interest in physiological synchronization or autonomic responses of both species. |

| Body Language |

14.29% |

Studies analyzed human and horse body posture, gestures, and movement, emphasizing non-verbal communication and behavioral patterns. |

| Facial Expressions |

20.00% |

Studies explored facial recognition, human emotion perception, and horse responses to human expressions, shedding light on interspecies emotional recognition. |

| Other Constants |

8.57% |

Studies measured additional parameters such as cortisol levels, EEG, and other stress-related biomarkers, indicating a smaller but relevant focus on neurophysiological and hormonal responses. |

Table 4.

Frequency and percentage distribution of various physiological and behavioral indicators observed in horse-human interaction studies. The table presents data on vocalization, heart rate, heart rate variability (HRV), cortisol levels (including blood, salivary, and fecal cortisol), EEG, and respiration, highlighting their occurrence across a sample size of 76 observations. The results indicate the prevalence of each measure and its relative importance in assessing emotional states in horses.

Table 4.

Frequency and percentage distribution of various physiological and behavioral indicators observed in horse-human interaction studies. The table presents data on vocalization, heart rate, heart rate variability (HRV), cortisol levels (including blood, salivary, and fecal cortisol), EEG, and respiration, highlighting their occurrence across a sample size of 76 observations. The results indicate the prevalence of each measure and its relative importance in assessing emotional states in horses.

| Vocalization |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

72 |

94.7 |

94.7 |

94.7 |

| Yes |

4 |

5.3 |

5.3 |

100.0 |

| Total |

76 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| Heart Rate |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

37 |

48.7 |

48.7 |

48.7 |

| Yes |

39 |

51.3 |

51.3 |

100.0 |

| Total |

76 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| Heart Rate Variance (HRV) |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

54 |

71.1 |

71.1 |

71.1 |

| Yes |

22 |

28.9 |

28.9 |

100.0 |

| Total |

76 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| Cortisol |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

65 |

85.5 |

85.5 |

85.5 |

| Blood Cortisol |

4 |

5.3 |

5.3 |

90.8 |

| Salivary Cortisol |

6 |

7.9 |

7.9 |

98.7 |

| Fecal Cortisol |

1 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

100.0 |

| Total |

76 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| EEG |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

75 |

98.7 |

98.7 |

98.7 |

| Yes |

1 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

100.0 |

| Total |

76 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| Respiration |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

74 |

97.4 |

97.4 |

97.4 |

| Yes |

2 |

2.6 |

2.6 |

100.0 |

| Total |

76 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

Table 5.

Frequency and percentage distribution of body language and heart rate observations in horse-human interaction studies. The table presents data on the occurrence of these behavioral and physiological indicators across a sample of 4 observations, highlighting their equal distribution in assessing emotional states in horses.

Table 5.

Frequency and percentage distribution of body language and heart rate observations in horse-human interaction studies. The table presents data on the occurrence of these behavioral and physiological indicators across a sample of 4 observations, highlighting their equal distribution in assessing emotional states in horses.

| Body Language. |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

Yes |

4 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| Heart Rate |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

2 |

50.0 |

50.0 |

50.0 |

| Yes |

2 |

50.0 |

50.0 |

100.0 |

| Total |

4 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

Table 6.

Frequency and percentage distribution of behavioral and physiological indicators observed in horse-human interaction studies. The table presents data on facial cues, body language, vocalization, heart rate variability (HRV), cortisol levels (including blood, salivary, and fecal cortisol), and respiration across a sample of 51 observations. The results highlight the prevalence of these indicators in assessing emotional states in horses, emphasizing the importance of combining behavioral and physiological measures for comprehensive evaluations.

Table 6.

Frequency and percentage distribution of behavioral and physiological indicators observed in horse-human interaction studies. The table presents data on facial cues, body language, vocalization, heart rate variability (HRV), cortisol levels (including blood, salivary, and fecal cortisol), and respiration across a sample of 51 observations. The results highlight the prevalence of these indicators in assessing emotional states in horses, emphasizing the importance of combining behavioral and physiological measures for comprehensive evaluations.

| Facial Cues |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

47 |

92.2 |

92.2 |

92.2 |

| Yes |

4 |

7.8 |

7.8 |

100.0 |

| Total |

51 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| Body Language |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

12 |

23.5 |

23.5 |

23.5 |

| Yes |

39 |

76.5 |

76.5 |

100.0 |

| Total |

51 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| Vocalization |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

49 |

96.1 |

96.1 |

96.1 |

| Yes |

2 |

3.9 |

3.9 |

100.0 |

| Total |

51 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| Heart Rate Variance (HRV) |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

24 |

47.1 |

47.1 |

47.1 |

| Yes |

27 |

52.9 |

52.9 |

100.0 |

| Total |

51 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| Cortisol |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

42 |

82.4 |

82.4 |

82.4 |

| Blood Cortisol |

3 |

5.9 |

5.9 |

88.2 |

| Salivary Cortisol |

5 |

9.8 |

9.8 |

98.0 |

| Fecal Cortisol |

1 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

100.0 |

| Total |

51 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| Respiration |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

49 |

96.1 |

96.1 |

96.1 |

| Yes |

2 |

3.9 |

3.9 |

100.0 |

| Total |

51 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

Table 7.

Frequency and percentage distribution of behavioral and physiological indicators in horse-human interaction studies. The table presents data on facial cues, body language, heart rate, and cortisol levels (including blood, salivary, and fecal cortisol) across a sample of 32 observations. The findings highlight the prevalence of these indicators, demonstrating their role in assessing emotional states and stress responses in horses.

Table 7.

Frequency and percentage distribution of behavioral and physiological indicators in horse-human interaction studies. The table presents data on facial cues, body language, heart rate, and cortisol levels (including blood, salivary, and fecal cortisol) across a sample of 32 observations. The findings highlight the prevalence of these indicators, demonstrating their role in assessing emotional states and stress responses in horses.

| Facial Cues |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

29 |

90.6 |

90.6 |

90.6 |

| Yes |

3 |

9.4 |

9.4 |

100.0 |

| Total |

32 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| Body Language |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

10 |

31.3 |

31.3 |

31.3 |

| Yes |

22 |

68.8 |

68.8 |

100.0 |

| Total |

32 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| Heart Rate |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

5 |

15.6 |

15.6 |

15.6 |

| Yes |

27 |

84.4 |

84.4 |

100.0 |

| Total |

32 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

| Cortisol |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

No |

26 |

81.3 |

81.3 |

81.3 |

| Blood Cortisol |

2 |

6.3 |

6.3 |

87.5 |

| Salivary Cortisol |

3 |

9.4 |

9.4 |

96.9 |

| Fecal Cortisol |

1 |

3.1 |

3.1 |

100.0 |

| Total |

32 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

Table 8.

Frequency and percentage distribution of cortisol levels in relation to behavioral indicators in horse-human interaction studies. The table presents data on the presence of facial cues, body language, and vocalization in horses, categorized by cortisol type (blood, salivary, and fecal). The results provide insights into the relationship between these behavioral responses and physiological stress markers, highlighting variations in cortisol levels across different observed behaviors.

Table 8.

Frequency and percentage distribution of cortisol levels in relation to behavioral indicators in horse-human interaction studies. The table presents data on the presence of facial cues, body language, and vocalization in horses, categorized by cortisol type (blood, salivary, and fecal). The results provide insights into the relationship between these behavioral responses and physiological stress markers, highlighting variations in cortisol levels across different observed behaviors.

| |

Cortisol |

| No |

Blood Cortisol |

Salivary Cortisol |

Fecal Cortisol |

| Count |

Column N % |

Count |

Column N % |

Count |

Column N % |

Count |

Column N % |

| Facial Cues |

No |

75 |

84.3% |

6 |

100.0% |

8 |

100.0% |

1 |

100.0% |

| Yes |

14 |

15.7% |

0 |

0.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

| Body Language |

No |

24 |

27.0% |

2 |

33.3% |

2 |

25.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

| Yes |

65 |

73.0% |

4 |

66.7% |

6 |

75.0% |

1 |

100.0% |

| Vocalization |

No |

85 |

95.5% |

6 |

100.0% |

8 |

100.0% |

1 |

100.0% |

| Yes |

4 |

4.5% |

0 |

0.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

Table 9.

Frequency and percentage distribution of cortisol levels in relation to physiological indicators in horse-human interaction studies. The table presents data on heart rate, heart rate variability (HRV), EEG, and respiration, categorized by different cortisol types (blood, salivary, and fecal). The findings provide insights into the relationship between physiological responses and cortisol levels, offering valuable information on stress assessment in horses. .

Table 9.

Frequency and percentage distribution of cortisol levels in relation to physiological indicators in horse-human interaction studies. The table presents data on heart rate, heart rate variability (HRV), EEG, and respiration, categorized by different cortisol types (blood, salivary, and fecal). The findings provide insights into the relationship between physiological responses and cortisol levels, offering valuable information on stress assessment in horses. .

| |

Cortisol |

| No |

Blood Cortisol |

Salivary Cortisol |

Fecal Cortisol |

| Count |

Column N % |

Count |

Column N % |

Count |

Column N % |

Count |

Column N % |

| Heart Rate |

No |

47 |

52.8% |

3 |

50.0% |

3 |

37.5% |

0 |

0.0% |

| Yes |

42 |

47.2% |

3 |

50.0% |

5 |

62.5% |

1 |

100.0% |

| Heart Rate Variance (HRV) |

No |

63 |

70.8% |

4 |

66.7% |

5 |

62.5% |

0 |

0.0% |

| Yes |

26 |

29.2% |

2 |

33.3% |

3 |

37.5% |

1 |

100.0% |

| EEG |

No |

88 |

98.9% |

6 |

100.0% |

8 |

100.0% |

1 |

100.0% |

| Yes |

1 |

1.1% |

0 |

0.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

| Respiration |

No |

87 |

97.8% |

6 |

100.0% |

8 |

100.0% |

1 |

100.0% |

| Yes |

2 |

2.2% |

0 |

0.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

0 |

0.0% |

Table 10.

Frequency and percentage distribution of body language observations in horse-human interaction studies. The table presents data on the occurrence of body language as a behavioral indicator, with all observed instances indicating its consistent presence in the sample.

Table 10.

Frequency and percentage distribution of body language observations in horse-human interaction studies. The table presents data on the occurrence of body language as a behavioral indicator, with all observed instances indicating its consistent presence in the sample.

| Body Language |

| |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

| Valid |

Yes |

1 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

Table 11.