2. Case Presentation

The patient is a male infant aged 1 month and 23 days, G1P2, delivered via full-term cesarean section, the smaller of twins. The mother had no abnormalities during prenatal check-ups, and the twin sister is healthy. There is no significant family medical history. The infant was brought to our hospital due to decreased appetite, paroxysmal coughing accompanied by breathing difficulties, and an unexplained rash. The family reported that a rash gradually appeared on the infant's forehead over the past month and later spread to the entire body. There were no accompanying symptoms, such as fever, diarrhea, or jaundice. Urination and bowel movements were regular.

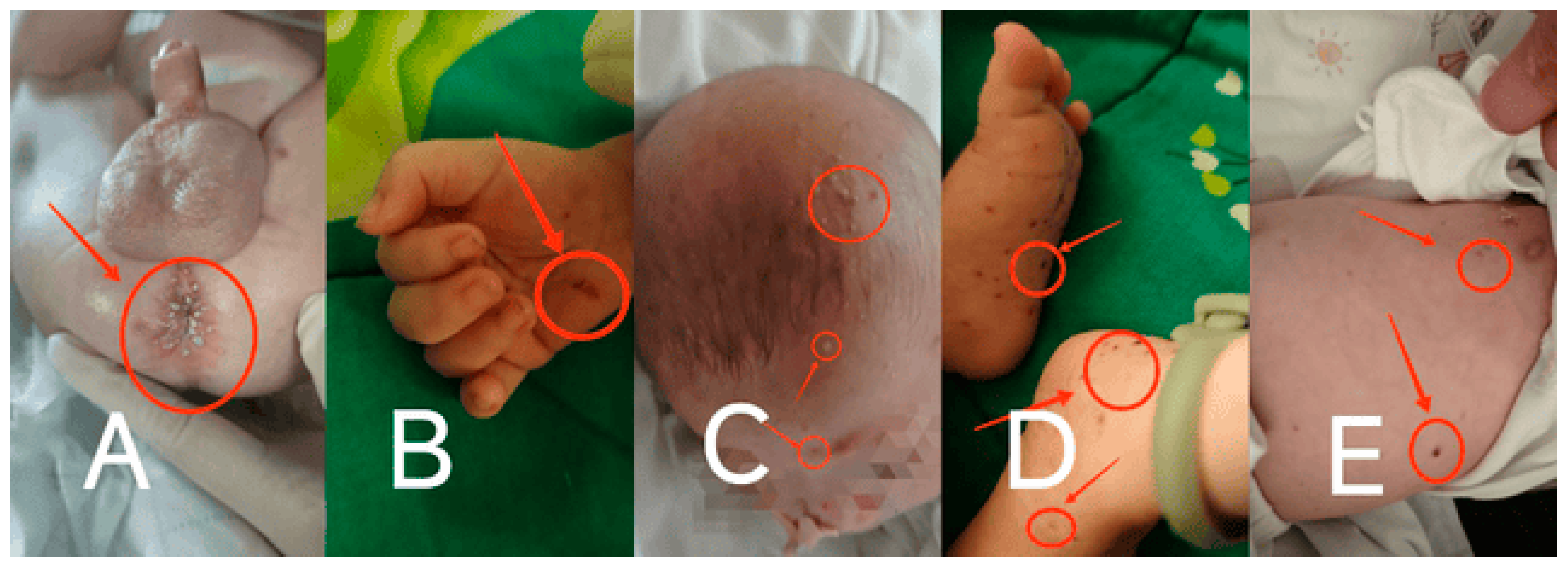

Physical examination: Upon admission, the infant was conscious but in poor spirits. No deformities were observed in the head or limbs. No lymph node enlargement was palpable. No abnormal secretions were found in the ears. The liver and spleen were not enlarged and had a medium texture. Moist rales were audible in the lungs. Scattered round, flat, raised papules and maculopapular rashes, ranging from millet to rice grain size, were observed on the head, trunk, and limbs. The rashes were yellowish-brown, with some showing central crusting and thin scaling on the surface. There was desquamation but no petechiae. Yellowish millet-like rashes were present in the perianal and perineal areas. (

Figure 1 A-E)

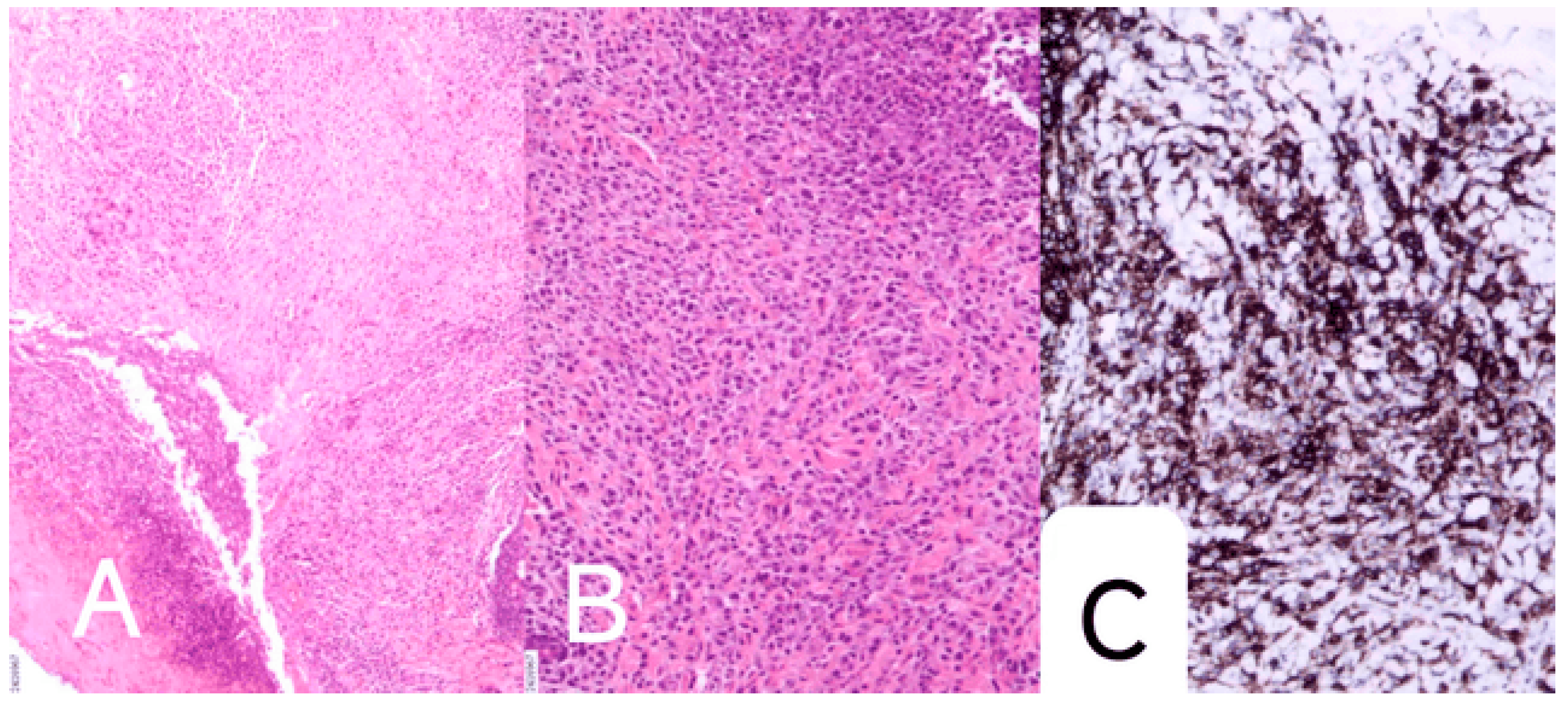

On July 11, 2024, the infant was taken to a local hospital due to "decreased appetite." On July 12, the infant developed significant paroxysmal coughing, and on July 13, rapid breathing and increased heart rate were observed, prompting transfer to our hospital. The infant was admitted to our hospital with the diagnosis of "decreased appetite for 7 days, coughing for 1 day, and difficulty breathing for half a day." Based on relevant auxiliary examinations, the infant was diagnosed with "severe pneumonia and respiratory failure." After admission, the infant was treated with anti-infection therapy, bronchoscopic alveolar lavage, and symptomatic supportive care. On July 27, 2024, due to worsening symptoms such as coughing and difficulty breathing, the infant was transferred to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) for further monitoring and treatment. Given the severity of the infection and the presence of multiple pathogens, the infant was treated with anti-infective therapy (including meropenem, co-trimoxazole, amikacin, and piperacillin-tazobactam sodium) and respiratory support. The infection markers gradually decreased during treatment. Throughout the illness, the infant exhibited reduced milk intake, poor mental status, significant oxygen desaturation during crying, rapid respiratory rate, and a gradually worsening rash that would fade and reappear, with some rashes turning light red and dark brown. Laboratory tests revealed anemia (hemoglobin 89 g/L), thrombocytosis (633×10^9/L), and markedly elevated CRP (127.42 mg/L). Bone marrow cytology demonstrated a mild left shift of the granulocytic series and marked erythroid hyperplasia with a reversed granulocyte-to-erythroid ratio (G: E = 0.89, 1). Immunological studies showed elevated levels of immunoglobulin A, immunoglobulin M, and complement components C3 and C4. Peripheral blood lymphocyte subset analysis indicated decreased T cells and NK cells, an elevated CD4/CD8 ratio, and increased B lymphocyte proportion, suggesting immune regulatory dysfunction. Pathogen testing identified Mycoplasma pneumonia, Pneumocystis jirovecii, and Rhinovirus A infections, while HIV and syphilis serology were negative. Imaging studies demonstrated multiple lesions in both lungs and liver, thymic enlargement with calcification, a mediastinal mass, and abnormal hepatic signals. Skin biopsy revealed Langerhans cell infiltration, with immunohistochemical staining positive for CD1α, Langerin, and S100. (

Figure 2 A-C)

Treatment and Prognosis: The patient received anti-infective and symptomatic supportive treatment during the PICU stay after admission. Once the diagnosis was confirmed and vital signs stabilized, the patient was transferred to the pediatric hematology department for specialized treatment. According to the 2018 Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis treatment protocol from the Shanghai Children's Medical Center (SCMC-LCH-2018), the patient was classified into the high-risk group and started standardized chemotherapy on August 8, 2024. Despite meticulous nursing care and strict disinfection and isolation measures, the patient experienced recurrent infections and fever. During chemotherapy, the patient exhibited poor oxygen maintenance, rapid breathing, inability to wean off oxygen, recurrent vomiting, and poor appetite. The patient's weight fluctuated around 4 kg during hospitalization (initial admission weight was 4 kg) and was only 3.5 kg at the time of death, indicating poor nutritional status. The last chemotherapy session was completed on October 1, 2024, after which the patient was voluntarily discharged from the hospital, intending to return for the next treatment cycle. During a follow-up three days later, the family informed our hospital that the patient had passed away on the morning of October 4.

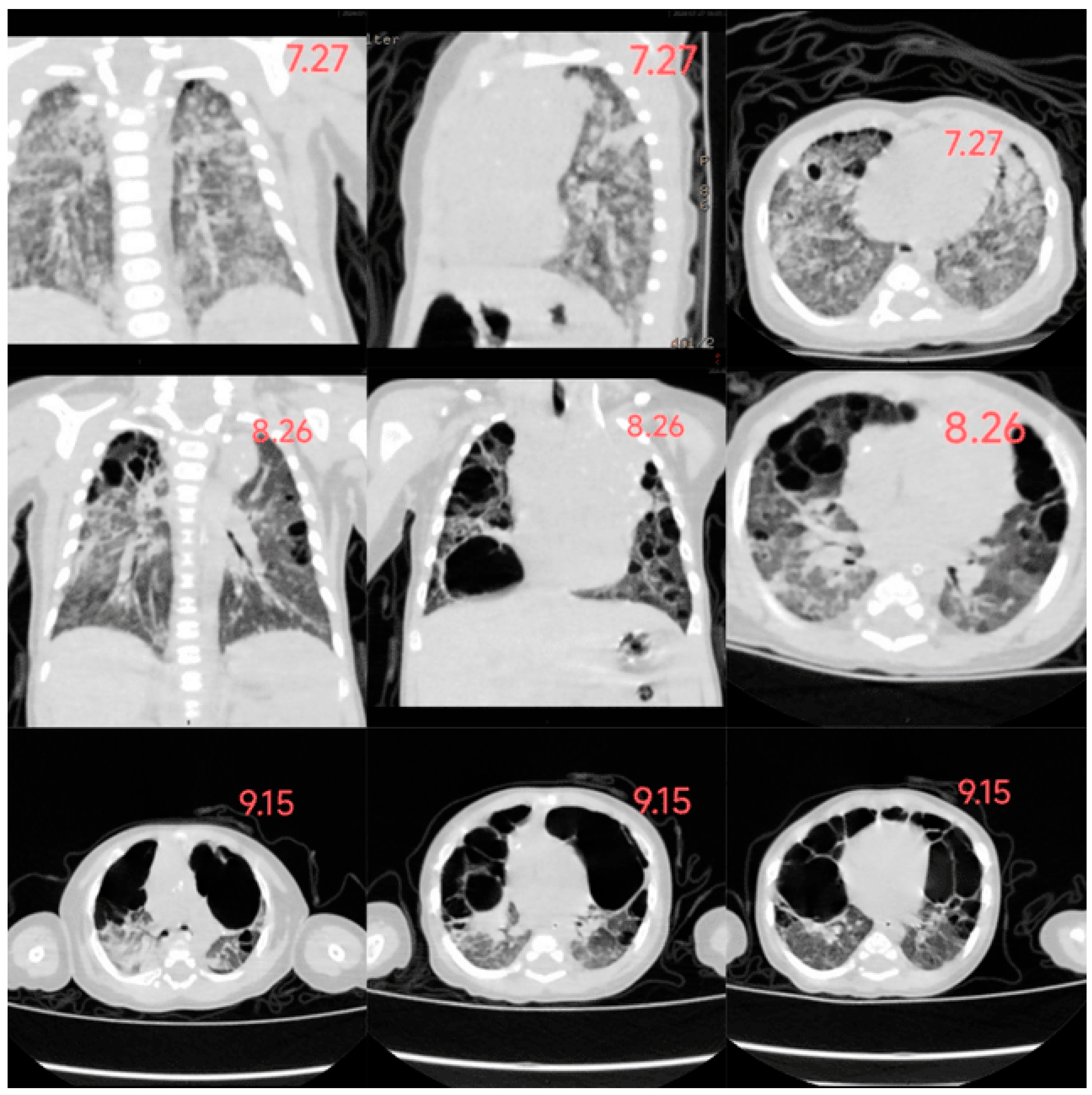

In this case, the infant developed a rash 20 days after birth, gradually spreading across the entire body. The rash presented as scattered millet-sized, round, flat, raised papules and maculopapular lesions, appearing light yellow, yellowish-brown, or dark brown. Some lesions had central crusting with thin scaling on the surface, accompanied by desquamation. However, a timely diagnosis was not made. By the age of 2 months (2 weeks after admission), the rash had worsened and involved the lungs and liver, leading to the development of pulmonary bullae and hepatomegaly. Based on pathological and immunohistochemical findings, the infant was diagnosed with Letterer-Siwe disease. After one month of guideline-directed treatment, follow-up chest imaging revealed further progression of pulmonary bullae, along with pancreatic involvement. Ultimately, the infant passed away, and the overall condition exhibited a progressively worsening trend. (

Figure 3: The changes in the infant's chest CT)

3. Discussion

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH) is a clonal proliferative disorder of Langerhans cells that can involve single or multiple organs, predominantly affecting infants and children. The estimated incidence in children is approximately 8-9 cases per million annually. Familial clustering has been observed in 1% of patients, and studies on twins have shown a higher concordance rate in monozygotic twins compared to dizygotic twins (92% vs. 10%) [

1]. The male-to-female ratio is 2:3 [

2].

Traditionally, LCH is classified into four types: eosinophilic granuloma (chronic focal), Hand-Schüller-Christian disease (chronic disseminated), Letterer-Siwe disease (acute disseminated), and congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis. Eosinophilic granuloma, the most common LCH in children aged 5 to 10, typically presents as painful bone masses (lytic lesions). Hand-Schüller-Christian disease, a chronic multisystem disorder, is characterized by the classic triad of diabetes insipidus (due to hypothalamic-pituitary axis involvement), lytic bone lesions, and exophthalmos. Letterer-Siwe disease, the most severe and aggressive form of multisystem LCH, manifests early in life, usually before the age of one. It is marked by cutaneous signs, liver and/or lymph node involvement and carries a poor prognosis [

3]. The mortality rate of Letterer-Siwe disease is at least 50%, making it the most severe variant of LCH. In this case, the infant exhibited multisystem involvement, including the skin, lungs, and liver, consistent with the clinical features of Letterer-Siwe disease.

Clinical Manifestations: Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH) can involve multiple organs, with the most commonly affected sites including bones (80%), skin (33%), pituitary gland (25%), liver (manifesting as jaundice, elevated liver enzymes, or hypoalbuminemia), spleen, lungs (presenting with cough, chest pain, and dyspnea, accounting for 15%), and lymph nodes (5-10%) [

2]. Since isolated skin lesions are observed in less than 2% of cases, cutaneous involvement is typically associated with multisystem disease [

4]. Early skin manifestations of LCH are often misdiagnosed as seborrheic dermatitis, diaper dermatitis, candidiasis, or atopic dermatitis. Due to the diverse cutaneous presentations, the misdiagnosis rate is as high as 16% [

5]. Additionally, some children may exhibit immune dysfunction, leading to concurrent candidal infections at rash sites, further complicating the diagnosis. In this case report, the infant presented with yellow, red, and brown papules, some of which were raised with central ulceration and yellow crusting. Scalp lesions resembling seborrheic dermatitis, characterized by scaly white to yellow erythematous patches, were also observed. Literature reports describe various skin manifestations of LCH, including vesicular, pustular, lichenoid, eczematous, hemorrhagic, and polymorphic rashes [

6]. Non-specific symptoms such as mucosal lesions (e.g., ulcers in the genital area or oral mucosa), paronychia, or onycholysis may also be present [

7].

Gastrointestinal involvement in LCH is rare, with highly variable and non-specific symptoms, often initially misdiagnosed as cow's milk protein allergy. A case analysis of LCH with gastrointestinal involvement revealed that nearly 95% of patients were under two years of age, presenting with symptoms such as bloody diarrhea, protein-losing enteropathy (PLE), anemia, vomiting, abdominal discomfort, constipation, and intestinal perforation. Notably, more than half of these patients died within 18 months of diagnosis [

8].

Approximately 10% of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH) children have pulmonary involvement. Somatic mutations are typically located in the proto-oncogenes of the MAPK signaling pathway, particularly BRAF V600E [

9]. In children, pulmonary LCH (PLCH) typically presents with two distinct clinical manifestations. In one form, pulmonary involvement in infants is often associated with multisystem disease (MS), affecting vital organs such as the liver, spleen, and blood. This form remains in the nodular phase, with rare occurrences of pneumothorax, and can be cured with systemic disease treatment, without sequelae. In the other form, pulmonary damage progresses insidiously, and symptoms may not become evident until the pneumothorax stage [

10]. Pulmonary involvement in pediatric LCH is typically part of a multisystem disease, with clinical presentations often atypical. Shortness of breath is usually the first and sometimes the only clinical sign, but other symptoms may include cough, difficulty breathing, pleural effusion, and recurrent pneumothorax. Typical radiological findings include ground-glass opacities, reticulonodular patterns, or cystic interstitial lesions. In later stages, cystic lesions may merge, leading to the formation of pulmonary bullae or even tension pneumothorax, which can result in severe complications [

11].

Diagnosis and Treatment: Diagnosing Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH) requires a comprehensive evaluation of medical history, clinical manifestations, imaging studies, laboratory tests, and histopathological findings. Definitive diagnosis typically relies on biopsy, with immunohistochemical detection of CD1a, CD207, and S100 being critical. Molecular genetic testing is essential for diagnosis and prognosis assessment, particularly for BRAF/MAPK/ERK mutation status. Additionally, mixed inflammatory infiltrates include T lymphocytes (FOXP3 and CD4), multinucleated giant cells, eosinophils, and macrophages. Langerhans cells exhibit a spherical shape, eosinophilic cytoplasm, and "coffee bean"-like indented nuclei. Polymorphism and abnormal mitoses are usually absent; if present, Langerhans cell sarcoma should be suspected [

2]. To differentiate LCH from other diagnoses, Tzanck smears, bacterial, viral, and fungal cultures, and serological tests may be utilized. Maternal infection history, medication use, and smoking during pregnancy may increase the risk of developing the disease.

Furthermore, in vitro fertilization, blood transfusions during infancy, neonatal infections, low socioeconomic status, inadequate feeding, and a family history of thyroid disease are potential risk factors for LCH [

12]. The management of LCH depends on the extent of the disease and the organs involved. Isolated skin lesions may resolve spontaneously, as seen in congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis. For severe multisystem disease, the Histiocyte Society's LCH-III protocol recommends a combination of systemic corticosteroids and vinblastine for 6-12 months. Additional treatment options include methotrexate, thalidomide, 6-mercaptopurine, cytarabine, and azathioprine [

13]. Significant progress has been made in targeted therapies against the MAPK pathway in recent years, particularly for patients with BRAF V600E mutations. BRAF inhibitors (e.g., vemurafenib and dabrafenib) and MEK inhibitors (e.g., trametinib) have demonstrated promising efficacy in high-risk or refractory LCH. They are used off-label in clinical practice, with many patients showing significant short-term improvement [

14]. However, targeted therapies have limitations, as BRAF inhibitors are ineffective against specific BRAF mutations, including insertions or deletions in exon 12, BRAF fusions with partner genes, and mutations in genes encoding upstream RAF functional proteins (e.g., RAS) [

14].

Additionally, paradoxical activation mechanisms may lead to significant cutaneous side effects, such as keratoacanthomas and squamous cell carcinomas. The prognosis of LCH primarily depends on organ involvement, with a 100% survival rate for single-organ disease but a 50% mortality rate in infants with multisystem high-risk organ involvement. Common sequelae include diabetes insipidus, growth hormone deficiency, orthopedic disabilities, skin issues, hearing loss, neurological/cerebellar complications, and secondary cancers. Overall prognosis is influenced by multiple factors, including the number and type of involved organs, patient age, and high-risk organ involvement [

15]. Despite the wide variability in clinical manifestations and outcomes, timely diagnosis and treatment are critical for improving patient prognosis.