1. Introduction

Logics of Statements in Contexts have been introduced in [

1] as a general framework enabling us to describe, analyze, relate and unify a variety of diverse concepts, results and constructions from a broad spectrum of logics and other formalisms including First-Order Logic [

2,

3,

4], Universal Algebra [

5], Algebraic Specifications [

6,

7], Ehresmann Sketches [

8], Generalized Sketches [

9,

10,

11], Description Logic [

12] and Graph Transformations [

13], for example.

From the more focused perspective of logic, Logics of Statements in Contexts propose a uniform way to define logics also comprising "open formulas". Especially, it has been shown that we can define arbitrary first-order "open formulas" in arbitrary categories.

At present, there are two main deficiencies. In the general case we do not consider operations since it is quite unclear for us how to generalize the traditional concept of operation for the category

of sets and total maps to arbitrary categories. Some results have been achieved for graph operations, i.e., for operations in structures with directed multi graphs as carriers instead of sets [

14,

15]. We are convinced that these results can be extended to arbitrary categorical presheaves instead of the presheaf

. However, even in case of

we have not been able yet to come up with a reasonable substitution calculus. We adapted in [

1] the concept of

institution [

16,

17] as an adequate pattern to present the basic constituents of a logic. That we constructed in [

1] only institutions of statements in context for single signatures, is the second main deficiency.

In this paper we turn back to the roots. We elaborate the paradigmatic special case of traditional many-sorted First-Order Logic where predicates and operations are combined. We show that any first-order signature

with predicate and (!) operation symbols gives rise to an institution

of

-statements in context, and that any signature morphism transforms into a comorphism between the corresponding institutions. We prove that we obtain a functor

from the category of signatures into the category of institutions and comorphisms. We construct a corresponding Grothendieck institution

[

17,

18] and prove that

is indeed an extension of the traditional institution of first-order logic

, as presented in [

16,

17] for example, which only comprises “closed formulas”. In addition, it turns out that

is not only opfibred over

(since it is a Grothendieck institution) but even over

in a certain sense.

It is well-known that

empty sorts potentially cause the problem that deduction rules for one-sorted first-order logic are, in general, not sound for many-sorted deduction [

17,

19]. We demonstrate that

contexts are an appropriate tool to localize and handle this problem in the spirit of [

19].

Another objective, leading us to the framework of Logics of Statements in Context, was the longing for a way of describing logics in a uniform abstract manner that is close to the way it is often done in traditional logic. We want to be allowed to restrict ourselves to finite signatures and to describe the language of a logic in an enumerable manner. We prefer a clear distinction between constant symbols and variables.

In addition, we intend to do (abstract) model theory even in case of finite signatures. From the perspective of model theory contexts serve as a bridge between syntax (constant symbols, variables) and semantics (elements of carrier sets), and can be utilized to define different kinds of sketches in analogy to the different kinds of diagrams in traditional First-Order Logic. In such a way, contexts also establish a "technological space" where deduction can take place. Deduction in Logics of Statements in Contexts is a big topic of its own and can not be covered in this paper.

To facilitate the reading and understanding of the paper, we recapitulate some methodological principles which guided the design of Logics of Statements in Context:

"Open formulas" should be treated as first-class citizens.

All syntactic entities and not only the basic ones, like predicate and operation symbols, should have a semantics in a given structure.

The semantics of a term in a given structure is a "derived operation" assembled from the "basic operations", i.e., the semantics of operation symbols in the given structure. So, terms give us a syntactic representation of "derived operations" at hand.

To obtain, in the many-sorted case, a sound and complete deduction calculus it is not enough to take into account only the set of all free variables syntactically appearing in a formula. The set of free variables needs to be bound, in principle, to a bigger context.

"Open formulas" without such a binding are called expressions. We do not consider expressions as formulas but, in analogy to terms, as syntactic representations of "derived predicates" assembled from the "basic predicates", i.e., the semantics of predicate symbols in the given structure.

Expressions bound to a context are called statements in context.

In such a way, we can also encapsulate the relatively intricate construction of first-order expressions, in the sense, that the translation of statements along context morphisms can be simply defined by composing bindings with context morphisms. We adapted this "encapsulation trick" from [

16] where it is used for initial and free constraints.

The paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 recapitulates some basic concepts and corresponding notational conventions.

Section 3 gives a rigorous and novel description of basic concepts in many-sorted first-order logic and their semantics – signatures, terms and expressions.

Section 4 is devoted to signature morphisms. We start with a detailed analysis of the functors induced by maps between finite sets of sort symbols and elucidate, especially, the special role of disjoint sorted sets. This enables us to describe the translation of terms and expressions along signature morphisms by means of natural transformations. On the semantic side, we define reducts of structures, homomorphisms, derived operations and derived predicates in the opposite direction. This gives us, finally, a

satisfaction condition for expressions and assignments at hand. The traditional institution of first-order logic

is reconstructed by restraining the natural transformations and the satisfaction condition to closed expressions.

In

Section 5 we finally present the institutions

of

-statements in context, the functor

and the Grothendieck institution

. In

Section 6 we investigate substitutions in detail and develop corresponding extensions of constructions and results in

Section 3 and

Section 4.

Section 7 recalls the concepts sketch and sketch implication. We adapt the proposal in [

1] to formalize diagrams, in the sense of traditional First-Order Logic [

2,

3], as sketches. We conclude the paper with

Section 8.

2. Notations and Preliminaries

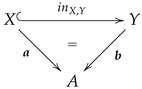

Categories and Functors denotes the collection of objects of a category and the collection of morphisms of , respectively. is the collection of all morphisms from object A to object B in . If the category is clear from the context, we will often use the more compact notation instead of . We use the diagrammatic notation for the composition of morphisms and in .

An object in a category is called initial if there exist for any object A in a unique morphism from into A often denoted by and called initial morphism for A.

states that category is a subcategory of category . The corresponding inclusion functor is denoted by .

A category is small if the collection , and thus also the collection , is a set. is the category of all small categories. denotes the category of all sets and all (total) maps. and are not small! A category is locally small if is a set for all objects A and B in . and are locally small! is the category with all small categories and categories like and as objects.

To lighten notation, we often use, in case , the same identifier for the restriction of a functor to subcatgories , .

For a category

we denote by

the underlying

reflexive graph, i.e., in

we simply forget that there is a composition operation in

. Obviously, each functor

comprises a corresponding

reflexive graph homomorphism between the underlying reflexive graphs (compare the concept of a "model of a graph in a category" in [

8]). Be aware, however, that not every reflexive graph homomorphism

establishes also a functor

because a reflexive graph homomorphism

is not required to be compatible with composition.

Natural Transformations and Functor Categories: If and are natural transformations, the vertical composition of and is denoted such that for each , .

Also, if , , are functors and is a natural transfomation, the horizontal compositions of with , and with are represented as and such that for each , , whereas .

Moreover, we have for functors

,

,

,

and natural transformations

,

the following laws

For categories and we denote by or the corresponding functor category with objects all functors from into , morphisms all natural transformations between those functors and vertical composition of natural transformations.

The traditional definition of natural transformations

between functors can be reused to define natural transformations

for all (!) reflexive graph homomorphisms between the underlying reflexive graphs of categories. The equations in (

1) and (

2) remain valid for those reflexive graph homomorphisms and natural transformations between them.

S-sorted Sets: We can consider any set S as a discrete category. The corresponding functor category has S-indexed families of sets as objects, called S-sorted sets or S-sets for short, and as morphisms S-indexed families of maps, called S-maps. The empty S-set is the initial object in . is called a singleton S-set if there is only one with and if is a singleton for this . denotes the full subcategory of given by all disjoint S-sets , i.e., we have for all with .

Inclusions: For any inclusion of sets there is a corresponding inclusion map with for all . There is an S-inclusion between S-sets and if for all . The corresponding inclusion S-map is . Intersections, unions and complements of S-sets are also defined component wise.

S-typed Sets: For any set S the slice category has as objects S-typed sets, i.e., pairs of a set C and a typing map . A morphism is given by a map such that .

The assignments extend to a functor which restricts to an isomorphism where is the full subcategory of given by all disjoint S-sets. The inverse functor is given by union of component sets and assigns to each S-set the S-typed set with if . can be extended to a functor by utilizing disjoint union (sum) instead of union for all non-disjoint S-sets. This establishes an equivalence of categories with .

3. Basic Concepts and Constructions in First-Order Logic

Name spaces: It is under-communicated that the definition a morphism between concrete institutions often relies on the implicit assumption that the syntactic entities of both institutions are build upon the same stocks of symbol identifiers. We restrict ourselves in this paper to finitary syntactic entities. Therefore, we assume that all considered first-order institutions are build upon a certain choice of four enumerable and disjoint name spaces:

A set of names for operation symbols.

A set of names for predicate symbols.

A set of names for sort symbols which is equipped with a fixed total order.

A set of names for variables which is equipped with a fixed total order.

In this paper we choose to be a subset of words with at least two letters over the Latin alphabet with lexicographic order, and for we choose the totally ordered set .

3.1. Signatures and Structures

In this paper about first-order logic we use the traditional term "signature" instead of the neologism "footprint" coined for the general setting in [

1]. Since we will neither misuse constant symbols to encode variables nor to encode elements of carriers of first-order structures, we can restrict ourselves to finite signatures only.

To define a many-sorted signature

, we first have to choose a finite set

of sort symbols. In [

1] we require that the arities of predicate and operation symbols are defined by means of "variable declarations". For a chosen set

S the corresponding "variable declarations", in the sense of [

1], are given by the set

of all finite and disjoint (!)

S-sets

with

for all

. We will simply call them "

S-sets of variables" instead of "variable declarations".

Definition 1 (Signature). A(many-sorted) signature is given by

a finite set of sort symbols,

a finite set of predicate (relation) symbols,

a finite set of operation (function) symbols, and

arity functions , , where is a singleton S-set for all . By we denote the only with . We also assume that and are disjoint for all (compare [15]).

Remark 1 (Representation and Syntactification of S-sets of Variables). Since is by assumption equipped with a total order, any finite set inherits from a total order thus we can represent, especially in examples, any S-set as an m-tuple of sets where is thecardinalityof S.

Moreover, for any S-set of variables the union of its components sets inherits a total order from . This allows us to represent X by encoding the equivalent S-typed set as an n-tuple ofvariable declarationswith , denoting the i-th variable in the totally ordered set and for all .

In such a way, we can also syntactically encode the S-set X of variables by the string of symbols .

Example 1 (Signature). We chose with sort symbols "" for person and "" for natural number. The sample signature is then defined by

with predicate symbols for "parent", for "female" and for "before", and the following arities: represented by , represented by and represented by ; and

with operation symbols for "sp(ecial day)", for "pl(us that many days)" and the following arities: represented by , represented by , represented by and represented by , represented by , represented by .

Now, we are going to define the category of structures for a given signature .

Definition 2 (Structure). For a signature a -Structure is given by

an S-set A, called the carrier of ,

a family of sets of valid assignments for the predicate symbol in , and

a family of operations (functions) in .

Remark 2 (Representation of Variable Assignments). We consider an S-set in with . For a given S-set A, S-maps will be also called(variable) assignments of X in A.

Relying on Remark 1, we can establish a bijection between the set of all assignments of X in A and the Cartesian product with for all where denotes the i-th variable in the totally ordered set . That is, anyassignment can equivalently be represented as an n-tuple with for all . We will utilize both notations and synonymously.

Note, that in case of the empty S-set the only element in is represented by the empty tuple.

Example 2 (Structure). For the sample signature Σ in Example 1 we describe a sample Σ-structure thereby relying on the conventions in Remark 1 and 2:

For the carrier we choose to be the set of all dates from 01.01.1700 on. is the set of all positive natural numbers and is the set of all persons born in Europe from 01.01.1900 on.

For the family the predicate is given by all triples of persons in such that is the father and is the mother of . Note, that there is no information in about the parents of a person, if one of the parents is born before 01.01.1900 or outside Europe. is the subset of all female persons in and is given by the usual irreflexive before-relation between dates.

For the family the operation provides for each person p in the date of its day of birth. Note, that we have chosen and in such way that is ensured to be a total operation! For any date and any natural number is the date of the n-th day after d. is the natural number 1 and the special date .

Homomorphisms preserve as well "truth" as "operation behavior".

Definition 3 (Homomorphism). A -homomorphism between two Σ-structures and is given by an S-map such that

- 2.

for all and all input assignments , i.e., .

denotes the category of all -structures and all -homomorphisms.

3.2. Terms and First-Order Expressions: Syntax

We consider terms and first-order expressions as syntactic entities and define them as finite strings of symbols. To distinguish terms from meta-level expressions, such as , we will use angle bracket symbols , instead of parenthesis , to build terms. Moreover, we will use delimiter signs ⌈…⌉ to indicate that the expression between the delimiters is a string. So, the delimiter signs are not constituents of terms and we may just drop them if convenient.

To be prepared for later and future developments we introduce terms not only for

S-sets of variables but for arbitrary disjoint (!)

S-sets. The following is a traditional inductive definition of terms similar to [

5,

6] and relies on the conventions in Remark 2:

Definition 4 (Terms: Syntax). The S-set of all-termsover a disjoint S-set A is the smallest S-set of strings of symbols such that

Variables: for all , ;

Constants: for all with , i.e., ;

Operations: for all with and all assignments in .

Note that the assignments , assigning to each element in A the string constituted exactly by this single symbol, define an injective S-map : .

Note further, that each operation symbol with is reborn as the -term with the as in Remark 2.

Remark 3 (Terms: Disjointness and Inclusions). The S-set is disjoint since A is disjoint and since our concept of signature avoids the so-called "overloading of operation symbols"!

In such a way, the inductive definition of can be equivalently seen as the inductive definition of a set of strings together with a typing map !

We do have whenever . For a disjoint S-set B not every Σ-term in "syntactically contains" all the elements in B. The S-set of all the elements in B, "syntactically appearing" in a Σ-term , is the smallest S-subset such that .

Example 3 (Terms: Syntax). There is no recursion in the sample signature Σ in Example 1 thus we have "up to renaming of variables" only five Σ-terms, all of sort , in addition to the four "reborn operation symbols" , , and . The five Σ-terms are over , over , over , over and over .

Remark 4 (Syntactification of Substitutions). Variable assignments of the form will be also called-substitutions. Due to Remark 2, we can uniquely represent any Σ-substitution by an n-tuple of terms where .

What we implicitly did in Definition 4, was to introduce the corresponding syntactic encoding of the substitution as a string of symbols. For the injective S-map : we get with variables due to Remark 1. In case of the empty S-set the only element in is represented by theempty tuple thus we have .

First-order expressions are strings of symbols. For convenience we drop, however, the delimiter signs in the following definition.

Definition 5 (Expressions: Syntax). For a signature , we define inductively and in parallel a family of sets of(first-order) -expressions on X, in symbols, where X varies over all S-sets of variables, i.e., all elements in :

-

Atomic expressions:

- (a)

Equation: for any and any .

- (b)

Relational Atom: for any and any S-map .

Everything: for any S-set X of variables.

Void: for any S-set X of variables.

Conjunction: for any expressions and .

Disjunction: for any expressions and .

Implication: for any expressions and .

Negation: for any expression .

Quantification: and for any expression and any proper S-inclusion .

Remark 5 (Syntax of expressions).

There are three changes compared to the general Definition 8 in [1]. First, we do not use arbitrary S-maps between S-sets of variables but only proper inclusion S-maps in quantifications. Second, these inclusion S-maps are not considered to be morphisms in the category of "variable declarations" for the institutions of statements defined in Section 5.1. Third, we adapt the traditional notation for quantification, i.e., we represent the proper inclusion S-maps by the complements in .

Attention, we do not keep track of the "free variables" that actually appear in an expression (compare Remark 3). ensures, however, that all "free variables" in are contained in X. So, in case of quantification, it may happen that none of the variables in appears as a "free variable" in !

Our design decision, to explicitly declare first all the variables , which are available, before actually constructing expressions using only the variables in X, together with our requirement for quantification has a subtle but important consequence. If then none of the variables in X appears as a "bound variable" in . Other variables than the ones in X can appear, however, multiple times as "bound variables" in but only in non-overlapping "sub-expressions". Lately, we learned that these syntactic restrictions correspond toBarendregt’s variable convention

for the λ-calculus (see [20], p. 26):

bound variables are distinct from free variables, and

all binders bind variables not already in scope.

Every predicate symbol is reborn as the Σ-expression with . Keep in mind, that with according to Remark 4.

Remark 6 (Everything and Void). We consider ⊤ and ⊥ not aslogical constantsbut asbuilt-in nullary predicate symbols, i.e., . Therefore, we are not using symbols likeTorF, for example. Built-in, means, especially, that ⊤ and ⊥ do have a fixed semantics for any Σ-structure , namely and . Be aware, that the string in and encodes the initial morphism .

Analogously, the equation symbol "=" can be seen to represent an S-indexed family of binary built-in predicate symbols with a fixed semantics in any Σ-structure. Finally, built-in means that none of the symbols appears in any of the sets , , or .

Remark 7 (Closed expressions: Syntax).

Σ-expressions of the form will be calledclosed -expressions. They represent nullary derived predicates that can be either valid or not valid in a given Σ-structure (compare Remark 6, Remark 9 and SubSection 4.2.5).

Example 4 (Expressions: Syntax). We continue Example 3 and discuss some Σ-expressions for the sample signature in Example 1. For convenience, we will drop some parentheses and simplify the notations for encodings of S-sets of variables introduced in Remark 1.

The following closed Σ-expression, which we identify by the auxiliary name ,

claims that biological parents are always born before their children.

Our main methodological point is, however, to consider expressions as syntactic representations ofderived predicatesenabling us to denote properties in an anonymous way. We may say, for example, that the sample signature in Example 1 is redundant in the sense that the property, denoted by the basic predicate , could be also represented by the following Σ-expression

which we consider as a derived predicate with arity and auxiliary name . The following atomic Σ-expression gives us the property "born before" for two persons at hand

The next Σ-expression represents the property "being sibling of someone" thereby hiding the witnesses for a corresponding statement about a certain person

Our last sample Σ-expression, with auxiliary name , represents the bit more intrinsic property "being half-sister of someone"

3.3. Terms and First-Order Expressions: Semantics

As mentioned in

Section 1, the semantics of a

-term in a given

-structure should be a derived operation. To define those operations, we consider the

evaluation of -terms in

-structures: Let a

-structure

be given. Based on Definition 4 and employing the fixed semantics

of all operation symbols in

F, we can inductively extend any assignment

of an

S-set

X of variables in the carrier

A to an S-map

such that

This allows us to define the

semantics of a -term in a

-structure

as the map

defined by

for all

. We call

the derived operation in

represented by

t. Each variable

represents a

projection (compare Remark 2).

We can go even further: Any

-substitution

defines a

derived operation in

(in the opposite direction!) with

Since

is a singleton, the

S-inclusion

represents a constant operation

. Moreover, the canonical injective

S-map

:

represents the identity

S-map on

:

Example 5 (Terms: Semantics). We discuss the semantics of the five non-trivial Σ-terms from Example 3 in the Σ-structure defined in Example 2.

For the "derived constant" we have . computes for each date the date of the next day. provides for each natural number the date of the n-th day after 19.10.1958, while computes for each person and each natural number the date of the n-th day after the day of birth of person p and provides the date of the next day after the day of birth of person p.

Our idea is, to consider first-order -expressions as derived predicates with a fixed semantics in any -structure . To define the semantics of a -expression in , we first have to define the semantics of the S-set X of variables in . This is simply the set of all assignments of X in A. A -expression is built upon -terms, predicate symbols and substitutions. The semantics of -terms and substitutions in we do have already at hand, thus it remains to define the semantics of -expressions in employing the fixed semantics of all predicate symbols in P. Relying on Definition 5, we will inductively define the family of sets of valid assignments (solutions) of in . For convenience, the interested reader may use instead of , the more traditional notation to follow the definitions.

Given an S-inclusion , we say that an assignment is an expansion of an assignment to Y if, and only if, .

Definition 6 (Expressions: Semantics). The semantics of Σ-expressions in an arbitrary, but fixed, Σ-structure is defined inductively:

-

Atomic expressions:

- (a)

Equation: iff .

- (b)

Relational Atom: iff .

Everything:

Void:

Conjunction:

Disjunction:

Implication: iff whenever

Negation:

-

Existential quantification: iff there exists an expansion of to Y such that .

Universal quantification: iff for all expansions of to Y we have .

Remark 8 (Expressions: Semantics).

As mentioned in Remark 5, every predicate symbol is reborn as the Σ-expression with . Definition 6 and Equation (5) ensure that also their semantics coincides .

The universal quantification is trivially valid for if there is no expansion of to Y at all, while the existential quantification is not valid, in this case.

Two expressions and aresemantical equivalent, in symbols, if, and only if, for all Σ-structures . Definition 6 ensures that we do have the usual semantic equivalences available. In particular, conjunction and disjunction are associative; thus we can drop, for convenience, the corresponding parenthesis as we have done it already at some places in Example 4.

Remark 9 (Closed expressions: Semantics). We consider a closed expression (see Remark 7). is a singleton with the initial morphism as the only element. In such a way, we have either , i.e., , or , i.e., .

Example 6 (Expressions: Semantics). We consider the sample Σ-structure in Example 2 and the derived predicates in Example 4.

For the closed Σ-expression we do have , i.e., . Note, that this is only the case since is defined in such a way that means that is the child of and .

The semantics of the derived predicate in coincides indeed with the semantics of the basic predicate in . gives us all the knowledge about "being a sibling of someone", that can be extracted from the information in , and the corresponding knowledge about "being a half-brother of someone". Remember, that there is no information in about the parents of a person, if one of the parents is born before 01.01.1900 or outside Europe.

4. Change of Base

In the last section we introduced and discussed basic concepts, structures and constructions connected to a single many-sorted first-order signature. In this section, we investigate how these concepts, structures and constructions are related across different signatures.

4.1. Maps Between Sets of Sort Symbols

By we denote the full subcategory of with objects all finite subsets of and morphisms all maps between those finite sets of sort symbols.

According to

Section 2, we do have for every

the category

of

S-sets, its subcategory

of disjoint

S-sets and the category

of

S-typed sets at hand.

For any map

we obtain a (reduct) functor

defined by

for all

-sets

and

for all

-maps

. We can consider the sets

S,

as discrete categories, thus

is simply defined by precomposing the functors

and the natural transformation

with the functor

. In such a way, the functoriality of

is ensured by the right equation in (

2). In addition, the left equation in (

1) entails that the assignments

establish a functor

.

Any fixed choice of finite sums in allows us to define a functor with for all S-sets A and

for all S-maps . becomes left adjoint to .

The crucial technical trick is, that we can choose the sums in to be the union for finite families of disjoint sets, thus we have for all disjoint S-sets A and all . Keep in mind that if there is no with , i.e., if . This "union trick" ensures two essential technical prerequisites:

The functor restricts to a functor (mimicking the functor ).

For families of non-disjoint sets the chosen finite sums will be, in general, not associative on the nose, thus the assignments and do not define a functor but only a pseudo functor from into .

Union of sets is, however, associative on the nose, thus the assignments and define a functor .

Note, is a "proper reduct functor" only for injective and restricts then also to a functor from to . For non-injective the functor produces, however, identical copies of some component sets and component maps, respectively, and restricts therefore not to a functor from to .

The functors

are later utilized to translate structures while the functors

will enable us to translate syntactic entities, like terms and expressions, in the opposite direction. The adjunctions

pave the way for proving satisfaction conditions. To facilitate these proofs, we use Lawvere’s characterization of adjunctions by means of comma categories [

21,

22].

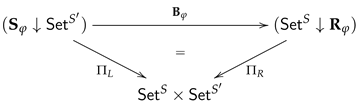

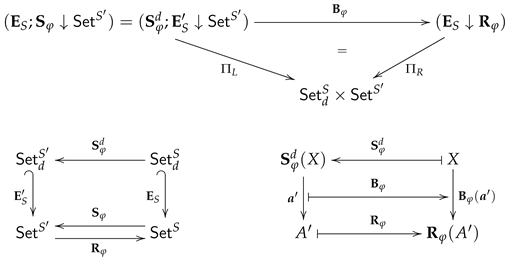

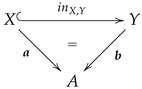

left adjoint to means nothing but that there exists an isomorphism between comma categories such that the following triangle of functors commutes.

More precisely, we will need a one-to-one correspondence between S-sorted variable assignments and -sorted variable assigments. Families of sets of variables are disjoint while carriers of structures are not. Therefore, we will later need the following restriction of to subcategories of and , constructed by means of the inclusion functors and .

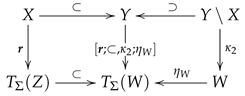

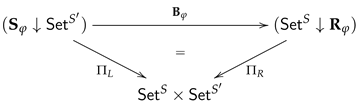

The objects in are all triples of a disjoint S-set X, an -set and an -map . The morphisms in are given by an S-map and an -map such that (see the left diagram below). is the obvious projection.

The objects in are all triples of a disjoint S-set X, an -set and an S-map . The morphisms in are given by an S-map and an -map such that (see the right diagram above). is the obvious projection.

The commutativity of the triangle of functors in (

6) ensures that the isomorphism

restricts to a bijective map

These canonical bijections appear, at least implicitly, in all proofs of the satisfaction condition for (fragments of) first-order logic (see [

17], for example) and are called "corresponding assignments" in [

23]. Moreover, we get

This follows immediately from the commutativity in (

6) and the functoriality of

:

Since the

are isomorphisms, we also do have the equivalent statement:

Symmetrically, it follows from the commutativity in (

6) and the functoriality of

:

Remark 10 (Pseudo Functors).

The original concept ofinstitution

[16,17] is based on the optimistic prerequisite that as well the reduction of models as the translation of syntax is functorial on the nose. As indicated in this section, we are able to meet this prerequisite, in case of first-order logic, if we work with S-indexed sets.

It is maybe worth to mention that we could not meet this prerequisite if we utilize S-typed sets instead. A functorial translation of syntax we would get for free by simple post-composition, i.e., by the functors . And, for any fixed choice of pullbacks in we would get, for all φ, a functor from to right adjoint to . However, for any fixed choice of pullbacks in the composition of chosen pullbacks will be not functorial on the nose thus reduction of models would as well not be functorial but only pseudo-functorial!

We have been facing this problem in [24] and guess that there are many situations where we are able to ensure functoriality on the nose for either "reduction of models" or "translation of syntax" while the other mechanism becomes pseudo-functorial only.

While indexed functors correspond to split (op)fibrations, indexed pseudo functors are just equivalent to (op)fibrations. It is maybe worth, to develop and explore, one day, a fibred counterpart of institutions simply based on (op)fibrations, to handle the obstacle of pseudo functors? One could, for example, relax the concept ofsplit fibred frames

in [25] to a concept offibred frames

. For such a project we have to bear in mind that there are actually four possibilities to transform an indexed category into a split (op)fibration not only the standard Grothendieck construction usually presented in the literature [8].

4.2. Signature Morphisms

In this subsection we introduce signature morphisms and define as well the reduction of structures as the translation of syntactic entities induced by signature morphisms.

Definition 7 (Signature Morphisms). Asignature morphism between signatures and consists of

a map ,

a map such that for all , and

a map such that and for all .

The composition

of signature morphisms

and

is defined component-wise:

The functoriality of the assignments ensures that becomes indeed a signature morphism .

denotes the category of all many-sorted signatures and signature morphisms. By construction, we do have the obvious projection functor which is a split opfibration.

4.2.1. Reducts

Signature morphisms are defined in a way that we can construct corresponding reducts of structures by means of the reduct functors

in

Section 4.1 and the bijections in (

7).

Definition 8 (Structure Reduct). Given a signature morphism the-reductof a -structure is a Σ-structure with

For later we should keep in mind that is a bijection by construction and that by definition of .

Reducts of homomorphisms are also given by the functors

in

Section 4.1, i.e., by reducts of

-maps, while the homomorphism property of the reducts is ensured by the equations in (

8) and (

9).

Definition 9 (Homomorphism Reduct). Given a signature morphism the-reductof a -homomorphism between two -structures ’ and ’ is the Σ-homomorphism given by the S-map .

Notation: As one can see, the subscript notations , and can become quite heavy. When there is no danger of ambiguity, we may just drop the subscripts from now on.

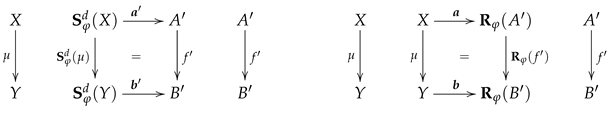

For any signature morphism the functoriality of entails that the assignments and define a functor .

On the global level the functoriality of entails for any signature morphisms and that for all -structures and for all -homomorphisms . The fact that adjunctions compose ensures, in such a way, that the functor lifts up to a functor given by the assignments and .

4.2.2. Translation of Terms

For each signature the assignments define a map from into . For convenience we can consider as a discrete subcategory of and use the functor notation for this map.

For any signature morphism the corresponding translation of terms is given by a natural transformation .

For each S-set X of variables in the -map , is simply the inclusion map of the empty set into for all . Relying on the inductive definition of in Definition 4 and the definition of by union, the family of maps for all is inductively defined as follows:

-

Variables:

if , ;

-

Constants:

if , , ;

-

Operations:

if , , .

The conditions for signature morphisms ensure that the left-hand sides in the three defining equations above are indeed -terms over the -set of variables. Note further, that for the assignment in (see Remark 4).

Remark 11 (Induction). Be aware, that we are not defining by induction over but by induction over ! This is justified by the observation that the disjointedness of ensures that the meta-level (!) inductive generation process of as a set of strings of symbols is still the same for since . Only the "typing" of the strings is changed (see Remark 3)!

Due to the inductive definition of terms and the corresponding inductive definition of term translation, one can inductively prove the following lemma relying on the facts that is a functor and that composition of signature morphisms is defined componentwise.

Lemma 1 (Composition of Term Translations).

For any signature morphisms , and the corresponding translations of terms , we do have:

Remark 12 (Typing of Terms). This remark is triggered by a discussion at Bergen Language Design Laboratory (BLDL) in 2023. According to Definition 4, there is no "type information" encoded in terms. That is, the type (sort) of a term and its subterms has to be deduced from the types (sorts) of the variables and the input and output arities of the involved operation symbols declared in the corresponding signature Σ. Note, that expressions involving quantification carry, in contrast, type information due to Definition 5 and Remark 1.

Let us consider signature morphisms only relaxing the type restrictions for predicate and operation symbols, i.e., signature morphisms between signatures and with a non-injective but surjective map. In this case, the natural transformation is not a real translation of terms but simply a family of inclusion -maps with X an S-set of variables.

In other words, for a given -term t there may be different signatures Σ and signature morphisms such that t is also a Σ-term!

4.2.3. Translation of Expressions

For each signature we inductively defined in Definition 5 a map from into . For convenience we can consider as a discrete subcategory of and use the functor notation for this map.

Relying on the translation of terms, defined in

Section 4.2.2, the translation of expressions for a signature morphism

is given by a natural transformation

. Be aware, that we use for both kinds of translation the same notation.

The family of maps with X in is defined inductively and in parallel by the following assignments:

-

Atomic expressions:

- (a)

Equation: for any and any .

- (b)

Relational Atom: for any and any S-map .

Everything:

Void:

Conjunction:

Disjunction:

Implication:

Negation:

Quantification: and for any expression and any proper S-inclusion .

For the case Quantification we have to bear in mind that implies and . By means of Lemma 1 one can inductively prove the following lemma relying on the facts that is a functor and that composition of signature morphisms is defined componentwise.

Lemma 2 (Composition of Expression Translations).

For any signature morphisms , and the corresponding translations of expressions and we do have:

4.2.4. Translation of Syntax vs. Reduct of Structures

For any signature morphism we do have now, on the semantic side, a corresponding reduct functor and, on the syntactic side, a corresponding translation of terms as well as a corresponding translation of expressions in the opposite direction.

The inductive definitions of terms and expressions and their syntactic translations ensure that the compatibility between the semantics of the basic syntactic entities operation symbol, predicate symbol and their syntactic translations, as described in Definition 8, lifts up to the derived syntactic entities term and expression.

For a given

-structure

we consider its

-reduct, i.e., the

-structure

as defined in Definition 8. First, we discuss the compatibility between the semantics of terms and their syntactic translation. According to (

4), any

-substitution declaration

defines a derived operation

in

. By means of

we can translate the

-substitution declaration

into a

-substitution declaration

and obtain a corresponding derived operation

in

. The bijections in (

7) establish a correspondence between the two derived operations assuring that

can be considered as the

-reduct of

.

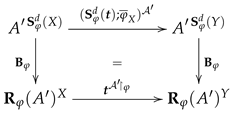

Proposition 1 (Derived Operation Reduct).

For any signature morphism , any -structure and any Σ-substitution declaration we have

Second, we discuss the compatibility between the semantics of expressions and their syntactic translation. For any

-expression

on an

S-set

X of variables its semantics in the reduct

is given by the derived predicate

. By means of

we can translate

into a

-expression

on the

-set

of variables and obtain a corresponding derived predicate

in

. The bijections in (

7) establish a correspondence between the two derived predicates assuring that

can be considered as the

-reduct of

.

Proposition 2 (Derived Predicate Reduct).

For any signature morphism , any -structure and any Σ-expression on an S-set X of variables the bijection restricts to a bijection .

If we use the more traditional notation

to indicate that

for an assignment

in a

-structure

, we get the following equivalent formulation of the statement in Proposition 2: For any signature morphism

, any

-structure

, any

-expression

on an

S-set

X of variables and any assignment

and thus

it holds that

Following the tradition in abstract model theory, we may call this the

satisfaction condition for expressions and assignments.

4.2.5. Traditional Institution of First-Order Logic

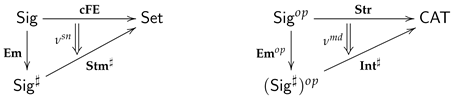

We obtain the traditional institution

of first-order logic, as presented in [

16,

17] for example, if we restrain our results to empty sets of variables only.

We start with the category of all many-sorted signatures and signature morphisms. The "model functor", in the sense of institutions, is the functor given by the assignments and .

For each signature we consider only the empty S-set of variables. The -sentences are exactly all closed -expressions (see Remark 7). For any signature morphism the corresponding translation of sentences is given by the map . Keep in mind that . Lemma 2 ensures that the assignments and define a sentence functor in the sense of institutions.

We say that a closed -expression is satisfied in a -structure , in symbols if, and only if, , i.e., (compare Remark 9).

For any signature morphism

and any

-structure

we do have

and

thus (

12) specializes for

to the statement

This means, that the satisfaction condition holds indeed in .

A crucial fact is that closed expressions, their translations and their semantics are constructed via a long detour through the realm of "open formulas" thus the proof of the satisfaction condition in (

13), for example, requires to prove (at least implicitly) general statements like in (

12). One motivation to develop Logics of Statements in Context was to establish a "conceptual and technological space" where all the general results concerning "open formulas" and variable assignments can be formalized, developed and presented in their full extent and beauty. The anticipated "conceptual and technological space" is also meant to become the home for deduction since deduction of first-order formulas takes essentially place in the realm of "open formulas".

It is well-known that empty sorts potentially cause the problem that deduction rules for one-sorted first-order logic are, in general, not sound for many-sorted deduction [

17,

19]. As a matter of fact, the simple concept of expression turns out to be not sophisticated enough to describe, formalize and analyze first-order deduction and the problems concerning many-sorted first-order deduction. In Logics of Statements in Context we introduce therefore a new conceptual layer of contexts, between the layer of sets of variables and the layer of carrier sets, and we are lifting up the concept of expression to the more flexible concept of "statement in context".

5. First-Order Logics of Statements in Context

5.1. Institutions of Statements

In this subsection we construct for each signature

an institution of statements

combining the constructions of Institutions of Statements and of Institutions of Equations in [

1]. Compared to the general case in [

1], we consider only the variant with the full spectrum

of first-order expressions and with the whole category

of

-structures as semantics

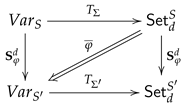

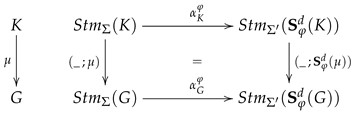

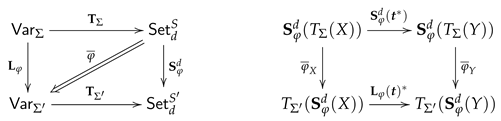

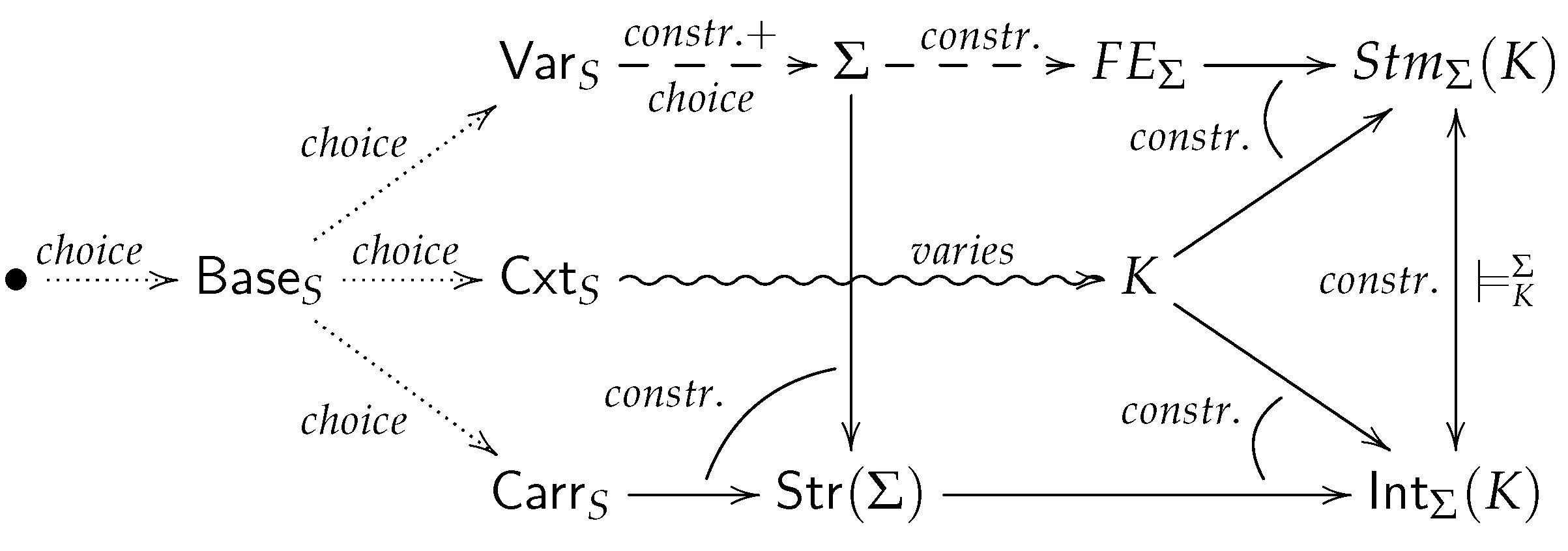

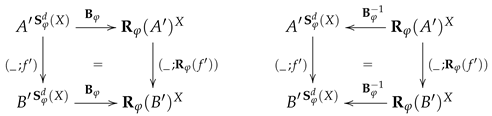

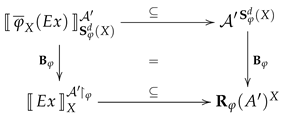

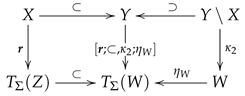

. Therefore, we only need a simplified version of the construction of institution of statements as visualized in

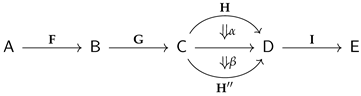

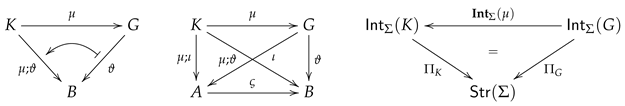

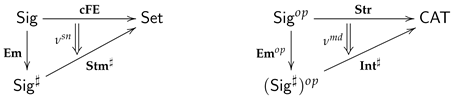

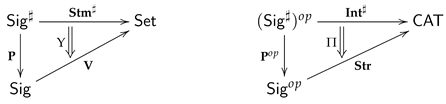

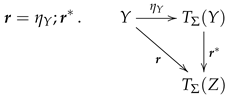

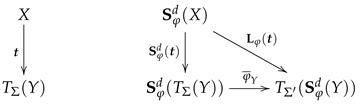

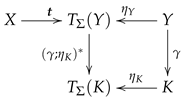

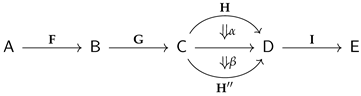

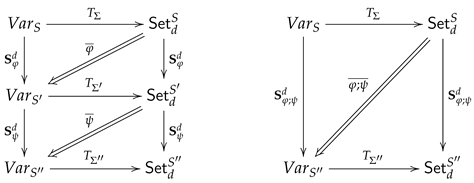

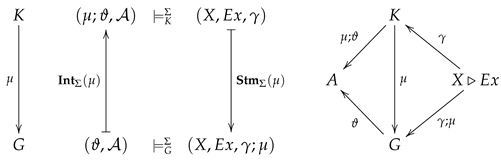

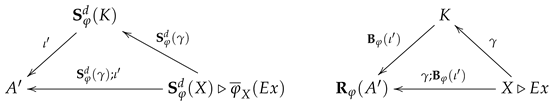

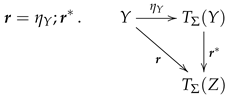

Figure 1.

The "base category" and the "category of (potential) carriers" are simply the category of

S-sets:

. At this stage, we do not consider the translation of expressions along substitutions

and thus not along inclusions

either. Those translations are discussed in

Section 6. Therefore, we choose as category

of "variable declarations" simply the set

considered as a discrete category.

is the category of all

-structures, as defined in

Section 3.1, and

is the

-indexed family of sets of first-order

-expressions, as defined in Definition 5.

It remains to define the "category of contexts"

. In traditional First-Order Logic contexts are not considered at all thus we could choose a cautious step and define

as the extension of

by all inclusions between

S-sets of variables. Those inclusions are, at least, implicitly present in traditional First-Order Logic! We drop this step for three reasons. First, we would just blow up the paper by "copying and paste" without providing new theoretical substance. Second, it would be too annoying always to underline and discuss why the same

S-set

X of variables plays, methodological seen, two different roles depending on if we consider

X as an object in

or as an object in

, respectively. The methodological distinction between these two roles becomes more naturally evident if we consider arbitrary contexts. Third, it is convenient to consider arbitrary contexts from the very beginning to be prepared for the discussion of "diagrams" [

2,

3,

17] in

Section 7.

In

Section 4 we learned that the translation of syntactic entities along signature morphisms becomes only functorial if the definition of syntactic entities is based on disjoint

S- sets. Therefore, we define the category of contexts to be the category of disjoint

S-sets:

. Contexts are the

abstract signatures in an institution of statements. Keep in mind that

by definition.

Since the interplay of predicates and equations is encapsulated in the construction of

, the general construction of Institutions of Statements in [

1] can easily be adapted for first-order logic with predicates and operations. To make the paper sufficiently self-contained and accessible, we give a concise presentation of the adapted definitions, constructions and results.

5.1.1. Institutions of Statements: Sentence and Model Functor

Statements in context are the sentences in an institutions of statements.

Definition 10 (Statement). A-statement in a context is given by a Σ-expression in and abinding S-map. is calledatomicif is an atomic expression, i.e., an Equation or a Relational Atom.

By , we denote the set of all Σ-statements in K and by the obvious projection map.

Remark 13 (General statements and closed formulas). For any closed Σ-expression (see Remarks 7 and 9) there is a unique initial morphism ; thus, we have for any context K and all closed Σ-expressions in . We call ageneral statement in K.

From all the general statements sharing the same closed expression , only the general statement in the empty context is the proper formal counterpart of traditional closed formulas in institutions of statements in context!

Example 7 (Context and Statement).

For the sample signature Σ in Example 1, we define a context K: is chosen to be a finite set ofsymbolic literals

in the sense of PROLOG. We distinguish clearly between sets of variables, carriers of structures and contexts, but allow that the same entity can play different roles (see also Section 7.2). In this spirit, we choose to be the set of all dates from 01.01.2000 to 31.12.2020 and .

In examples we adapt the encoding of assignments from Remark 2 and use for statements the shorthand notation accepting the possible loss that we can not reconstruct from the whole S-set X of variables. Instead of expressions , we will also use auxiliary names for expressions as introduced in Example 4, for example. If is a "reborn predicate symbol" (see Remark 5) we will use the traditional notation instead of .

is not a legal Σ-statement in context K simply because is not contained in . , however, is an atomic legal Σ-statement in K. Attention, we are not using a notation like , instead of , since is neither a variable nor a constant symbol, i.e., is not a Σ-expression. To say it differently: In syntax (predicate symbols, expressions, auxiliary names) and semantics (assignments) are not separated.

, , are atomic Σ-statements in K and from the last two Σ-statements we could deduce and .

, , , and are other Σ-statements in context K.

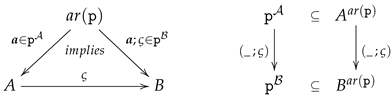

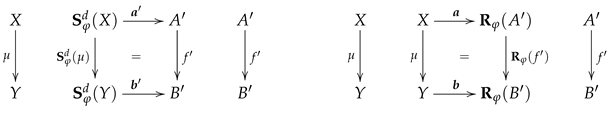

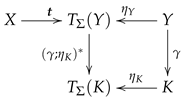

Any morphism

in

induces a map

defined by simple post-composition for all statements

in

K:

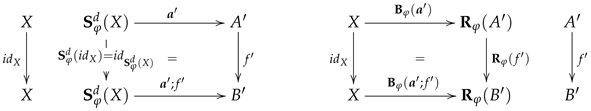

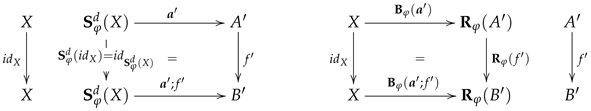

It is easy to show that the assignments and provide a functor . This is the sentence functor of the institution .

Interpretations of contexts are the models in an institution of statements.

Definition 11 (Context interpretations). A-interpretation of a context is given by a Σ-structure in and an S-map .

A morphism between Σ-interpretations of K is given by a Σ-homomorphism such that for the underlying S-map .

For any context K in , we denote by the category of all Σ-interpretations of K and all morphisms between them and by the obvious projection functor.

Remark 14 (Split Opfibration).

It is easy to see that the functor is a split opfibration with the opcartesian arrow for a Σ-homomorphism and an interpretation of context K in the Σ-structure [8]. Be aware that all morphisms in are opcartesion arrows, that is, for any Σ-structure , the correspondingfiber over , i.e., the subcategory of given by all interpretations of K in and all context morphisms , is a discrete category representing the hom-set .

Note finally, that is an isomorphism.

Any morphism

in

induces a functor

defined by simple pre-composition for all

-interpretations

of

G:

For any morphism

between two

-interpretations of

G the same underlying

S-map

establishes a morphism

between the corresponding two

-interpretations of

K, thus we have

One can easily validate that the assignments and define a functor . This is the model functor of the institution .

5.1.2. Institutions of Statements: Satisfaction Relation and Satisfaction Condition

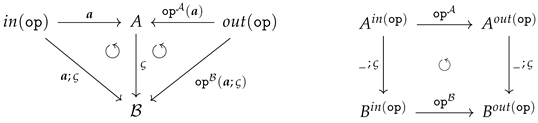

The last two steps, in establishing an institution, are the definition of a satisfaction relations and the proof of the so-called satisfaction condition. The satisfaction relations are simply provided by the semantics of expressions, as described in Definition 6.

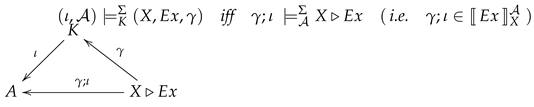

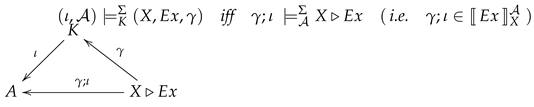

Definition 12 (Satisfaction Relation).

For any context , any Σ-statement in K and any Σ-interpretation of context K we define:

Remark 15 (Validity of Closed Formulas). If , we do have for any Σ-structure in exactly one interpretation thus for any closed formula (see Remark 13) means nothing but that the closed formula isvalid in in the traditional sense.

Moreover, the validity of closed formulas is "semantically context independent" in the following sense: For any context K, any Σ-structure , any Σ-interpretation of K in and any closed expressions , we have due to the uniqueness if intitial morphisms:

Example 8 (Interpretation and Satisfaction). For the sample context K in Example 7 and the sample Σ-structure in Example 2, we consider the "author intended interpretation" of K in with the S-map defined as follows: is the inclusion map from into , the inclusion map from into while assigns to each symbolic literal in the corresponding "real person" in from the family of the author. We discuss the satisfaction of the sample Σ-statements from Example 7 by .

is satisfied by since and . The atomic Σ-statements , and are satisfied by since they reflect, due to the definition of , the "real life" family situation of the author. In such a way, the definition of Σ-expressions and their semantics, ensures that also the two Σ-statements and are satisfied by , i.e., .

is not satisfied by since the "real person" is an only child. is true in "real life", however, not satisfied by since the mother of the "real person" is born in Venezuela. is satisfied by even if the only sibling of the author is not represented by a symbolic literal in . and are, finally, satisfied by since and .

After we developed everything in a systematic modular way, we obtain the satisfaction condition nearly “for free”.

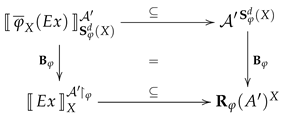

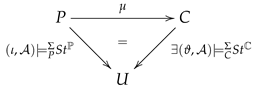

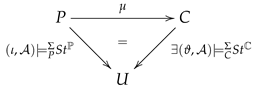

Corollary 1 (Satisfaction condition).

For any morphism in , any Σ-statement in context K and any interpretation of context G in a Σ-structure , we have:

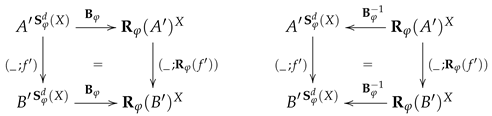

Proof. Due to the definition of the functors and , we obtain the commutative diagram, above on the right, thus the satisfaction condition follows immediately from Definition 12 (Satisfaction Relation). □

Summarizing all definitions and results, we obtain for each signature the Institution of -Statements in Context .

Remark 16 (Empty Sorts).

The fact that the rules for unsorted first-order logic are not sound for many-sorted first-order logic is caused by the freedom that some (or even all) components of the carrier S-set A of a Σ-structure can, in principle, be empty. This freedom is essential for applications of formal specifications as discussed, for example, in [26].

By introducing the conceptual level of contexts we are able to address and potentially deal with this issue. As said in the introduction, we will not present in this paper a comprehensive exposition of deduction but only discuss some aspects of deduction.

Deduction in Logics of Statements in Context means, in the first place, to deduce new statements in contexts from given statements in contexts by means of rules. The problem, caused by potentially empty sorts, can be identified by the observation that the equivalence in Remark 15 vanishes if there is no Σ-interpretation of the context K in the Σ-structure at all.

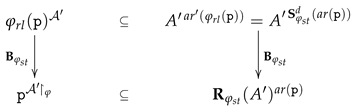

A rule, stating that we can deduce from the validity of in the empty context the validity of in any context K, will be always sound since is simply the translation of along the context morphism (see rule "Abstraction" in [19]). However, a rule stating that we can deduce from the validity of in a certain context K the validity of in the empty context will be only sound if there is, at least, one interpretation of context K in all Σ-structure ! This requirement can be only fulfilled if whenever for all (see rule "Concretion" in [19]).

5.2. The Indexed First-Order Logic of Statements in Context

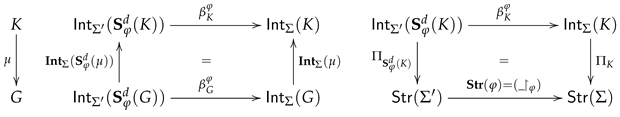

5.2.1. Institution Comorphisms

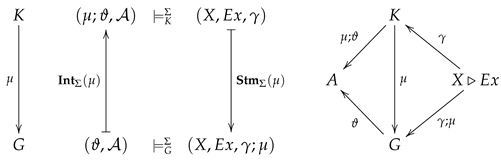

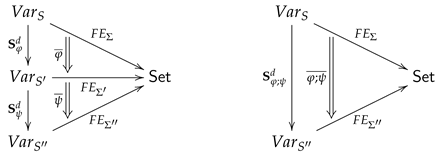

For any signature morphism

between signatures

and

, as defined in Definition 7, we consider the institutions

and

as described in the last subsection. We will construct an

institution comorphism consisting of (see [

17] or [

27] for a general definition of institution comorphisms)

a functor ,

a natural transformation , and

a natural transformation

such that the following

satisfaction condition for comorphisms holds:

for any context

, any

-interpretation

of

and any

-statement

in context

K.

By definition we have

and

thus we can simply set

Note, that there is no right adjoint for thus we can not equivalently describe the institution comorphism by means of an institution morphism!

Translation of Statements along Signature Morphisms

For any context

K in

we define the map

by means of the translation of expressions defined in

Section 4.2.3:

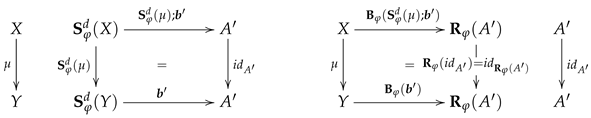

The assignments

constitute a natural transformation

since we defined the translation of statements along context morphisms by simple post-composition and since

is a functor.

Translation of Interpretations along Signature Morphisms

For any context

K in

we define the functor

by means of the bijections in (

7) and the reduct of structures defined in

Section 4.2.1:

The assignments

constitute a natural transformation

since we defined the translation of interpretations along context morphisms in (

15) by simple pre-composition and due to (

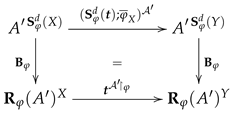

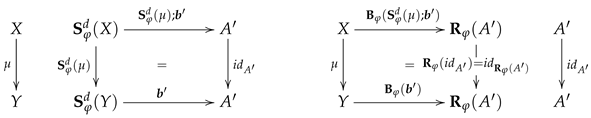

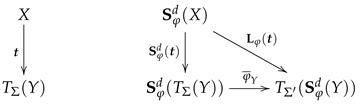

10) (see the diagram below on the left).

Supplementing (

16), we observe that

is defined in (

22) in such a way that

Satisfaction Condition for Comorphisms

Let be given a context , a -interpretation of and a -statement in context K.

First, due to the definition of

in (

22), the statement

is equivalent to the statement

while this statement is equivalent to

according to (

10) and Definition 12.

Second, due to the definition of

in (

20) and the definition of

in (

21) the statement

is equivalent to

while this statement is equivalent to

by Definition 12.

In such a way, the required satisfaction condition for comorphisms in (

19) exactly reflects the general satisfaction condition for expressions and assignments in (

12)!

5.2.2. Composition of Comorphisms

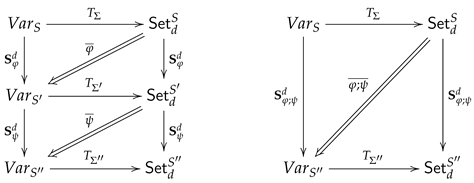

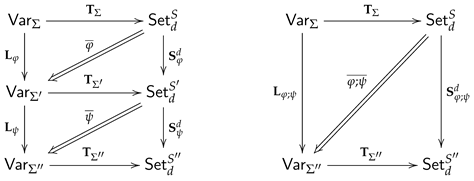

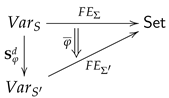

For any signature morphisms

,

the composition of the institution comorphisms

and

gives rise to an institution comorphism

given by (compare [

17])

the functor ,

the natural transformation , and

the natural transformation .

The definition of the institution comorphisms

in

Section 5.2.1 ensures that their composition can be represented by means of the composition of the underlying signature morphisms.

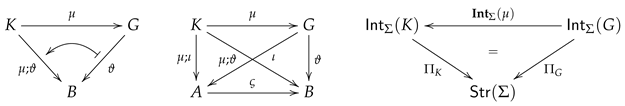

Lemma 3 (Composition of Institution Comorphisms).

For any signature morphisms and we have

Proof. Since

is a functor, we trivially have

due to (

20). Since

is a functor,

is an immediate consequence of Lemma 2 due to the definitions in (

20) and (

21). Since

and

are functors, the fact that adjunctions compose, finally ensures

due to the definitions in (

20) and (

22). □

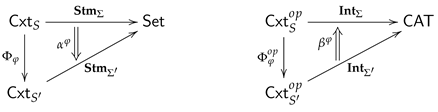

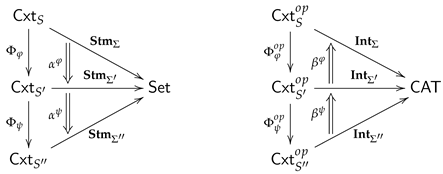

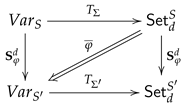

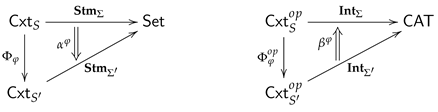

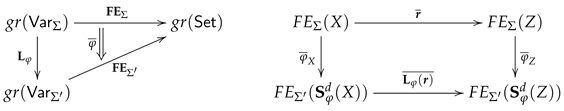

That the assignments

and

define a functor (also called an

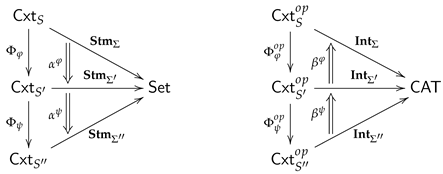

indexed comorphism-based institution [

17])

from the category

of many-sorted signatures into the category

of institutions and comorphisms, is an immediate consequence of Lemma 3. We call

the

Indexed First-Order Logic of Statements in Context.

5.3. The Fibred First-Order Logic of Statements in Context

5.3.1. A Grothendieck Institution

In contrast to [

17,

18], we ended up with a covariant functor

and not a contra-variant functor as an

indexed comorphism-based institution [

17]. As mentioned already in Remark 10, there are actually four possibilities to transform an indexed category into a split (op)fibration not only the standard Grothendieck construction usually presented in the literature [

8]. Correspondingly, there are, at least, four possibilities to transform an indexed institution into a Grothendieck institution. We will not present the general construction of Grothendieck institutions for covariant indexed comorphism-based institutions, but define directly a Grothendieck institution for

.

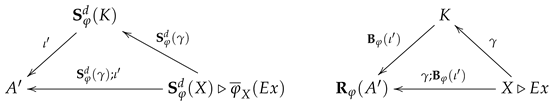

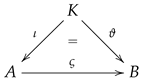

The Grothendieck institution for is constructed as follows:

-

The category has as

objects pairs with and , and as

morphisms pairs of a signature morphism and a context morphism where .

The composition of and is the morphism .

-

The sentence functor is given by

for each object in , and

for each morphism , i.e., for all we have .

-

The model functor is given by

for each object in , and

for each morphism , i.e., for all we have .

The satisfaction relation is defined by if, and only if, for each , , and .

By routine calculations, we can check that the definition of

transforms the satisfaction condition for comorphisms in (

19) to the satisfaction condition for

:

for any morphism

in

, any statement

and any interpretation

.

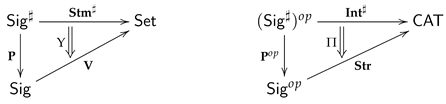

5.3.2. as an Extension of

We validate that we indeed achieved our objective to construct an institution extending the traditional institution

of first-order logic, as described in

Section 4.2.5, by arbitrary first-order "open formulas". We show that

can be fully embedded into

. Varying the terminology in [

17], we may say that

is a "full sub-institution of

up to renaming".

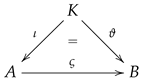

First, we observe that the assignments and define a full embedding . Keep in mind .

Second, there is a natural isomorphism

with maps

defined by

for all

. The map

is bijective since

is the only

S-map with codomain

! The naturality of

immediately follows from the definition of

in

Section 5.3.1 and the definition of

in (

21).

Third, there is a natural isomorphism

with isomorphisms

according to Remark 14. The naturality of

immediately follows from the definition of

in

Section 5.3.1 and (

23).

Fourth, the statement

for any signature

and any

-structure

is equivalent to the statement

, due to the definition of

in

Section 5.3.1, and Definition 12 entails that this statement is, in turn, equivalent to the statement

. This is, however, exactly how we defined the satisfaction relation

for

in

Section 4.2.5. In other words, the satisfaction condition in

is a restriction of the satisfaction condition in

!

5.3.3. A Fibred Institution

In addition of

being a full sub-institution of

, the construction of

also entails that

is fibred over

. The concept of

fibred institutions in [

17] is based on fibrations while we meet here opfibrations instead. Moreover, the concept of fibred institution in [

17] only relies on a fibration for the category of signatures. We will not coin a general concept of an institution fibred over another institution, but simply describe the strong relationship between

and

in terms of opfibrations.

The assignments and define a functor right-adjoint to the full embedding with . Moreover, is a split opfibration with the opcartesian arrow for a signature morphisms and an object in .

As discussed in Remark 14, the projection functors

are split opfibrations. The definition of

in

Section 5.3.1 and the equations (

16), (

23) ensure that the family of the obfibrations

establishes a natural transformation

.

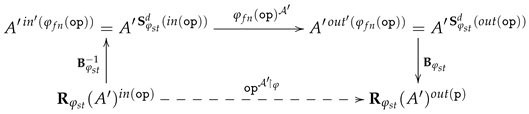

On the syntactic side, we do have another functor given by the assignments and .

For any object

in

there is a map

given by the assignments

. The definition of

in

Section 5.3.1 and the definitions in (

14), (

21) ensure that the family of the maps

establishes a natural transformation

.

We call together with the opfibration and the natural transformations , the Fibred First-Order Logic of Statements in Context.

Remark 17 (Applications).

Fortunately, we do have now two equivalent ways at our disposal to deal with fully-fleshed first-order "open formulas". It is, however, nearly impossible to state a priori which way will be most appropriate in applications. We guess that it will be, at the end, most convenient in many applications to utilize both ways in a well-defined interplay (compare [28], for example).

6. Substitutions

Substitutions are not relevant for utilizing a logic as a specification formalism. As also mentioned in [

17], substitutions are, however, an important logical device for deduction. In this section we investigate substitutions and develop corresponding extensions of constructions and results in

Section 3 and

Section 4 necessary and sufficient for deduction.

6.1. Categories of Substitutions

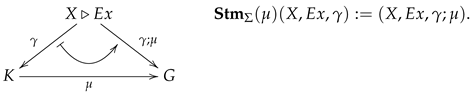

The simple, natural idea is to extend the sets of S-sets of variables by substitutions. For any signature the small category is defined as follows:

-

Objects:

are all S-sets X of variables, i.e., ;

-

Morphisms:

in are given by -substitutions ;

-

Identities:

on S-sets X are given by the canonical S-maps : ; and the

-

Composition:

of two morphisms

,

in

is given by the

-substitution

where

is the inductive extension of

such that

Note, that

describes nothing but the application of the

-substitution

to all

-terms over

Y! We can inductively prove that

thus the composition of substitutions is associative, and we get indeed a category.

Remark 18 (Lawvere Theories).

The tentative reader may have realized that the categories are nothing but so-calledsyntactic Lawvere theories

[21,22,29]. We will, however, not walk further into the realm of "Categorical Algebra" and "Functorial Semantics". We will neither utilize the fact that the categories are finite product categories nor reconstruct (Σ) as a subcategory of the functor category in case of signatures Σ without predicate symbols!

Remark 19 (Kleisli Morphisms).

It is a common practice to describe substitutions as morphisms of the Kleisli category of a "term algebra adjunction". In such a way, we would get the extension of assignments in (3) and the application of substitutions in (26) as well as their compatibility "for free". See the discussion of "internalization of terms" and substitution calculi in [15].

To stay closer to traditional presentations of logics, we rely instead in this paper on explicit inductive definitions (located on the meta-level). Another reason is, that some of the necessary constructions and results, as the translation of terms and Lemma 1 for example, can not be obtained by means of term algebra adjunctions (see Remark 11)!

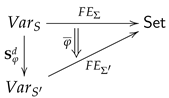

For a signature morphism

we can extend the map

in

Section 4.2.2 to a functor

defined by

for all substitutions

where

is the natural transformation defined in

Section 4.2.2 and describing the translation of

-terms into

-terms.

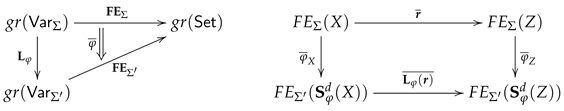

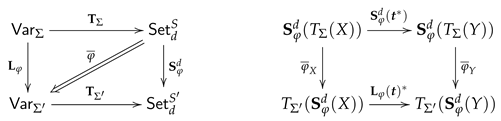

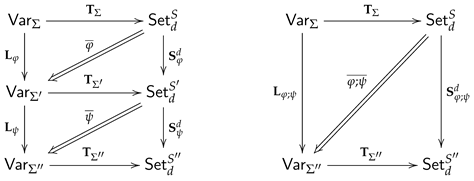

Lemma 1 ensures for any signature morphisms , thus the assignments and define a functor .

6.2. Translation of Terms and Substitution Application

We can also extend the maps

to functors

with

for all

S-sets

X of variables and

, due to (

26), for all

-substitutions

. Functoriality is ensured by (

27).

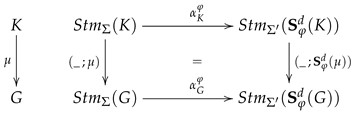

To show that the family of -maps also constitutes a natural transformation , we have to prove that for any -substitution the square of -maps on the right commutes.

Here we have another situation, as mentioned in Remark 19, where term algebra adjunctions are of no help. Since the -maps are defined by induction over , also the commutativity of the square has to be and can be shown by induction over (compare Remark 11).

Since the functors and are simply defined be extending the maps between objects and to morphisms, the validity of Lemma 1 is preserved.

Corollary 2 (Composition of Term Translations).

For any signature morphisms , and the corresponding translations of terms , we do have:

6.3. Translation of Expressions and Substitution Application

Analogously to terms, we would also like to extend the map to a functor . For all -substitutions we can indeed define a map describing the application of the substitution to -expressions on X. Due to the presence of quantification, the assignments will be, however, not functorial "on the nose" as we will discuss below.

There seems to be no way out! As long as we do not utilize something like the

de Bruijn index [

30] to avoid named bound variables, we have to deal, in one or another way, with the problem that substitution application may cause an unintended interaction between free and bound variables. One approach to avoid such an unintended interaction is to inductively define a binary meta-level predicate stating when a substitution is "legal" for a certain expression as it is done, for example, in [

4]. From the perspective of deduction, this is viable. We will, however, not adapt this approach, since we would end up with partial substitution maps .

Another approach is to use α-conversion, i.e., renaming of bound variables, in such a way, that we obtain total substitution maps. We will define the application of a substitution to expressions, according to the inductive definition of expressions in Definition 5, thereby establishing a stepwise inductive variant of -conversion.

To meet the "proper inclusion condition" for Quantification in Definition 5, we must use non-symmetric sums when defining substitution application in case of Quantification. That is, for any two S-sets of variables we must choose a sum in such that the left injection is an S-inclusion . If and are disjoint, we simply choose .

Definition 13 (Substitution Application for Expressions). For any signature Σ the family of maps with a Σ-substitution is defined inductively and in parallel by the following assignments:

-

Atomic expressions:

- (a)

Equation: for any and any with given by (26). - (b)

Relational Atom: for any and any S-map with given by (26).

Everything:

Void:

Conjunction:

Disjunction:

Implication:

Negation:

Quantification: and for any expression and any proper S-inclusion where and thus . The extended substitution is constructed as a cotuple. Keep in mind Remark 3 and that Y is the sum of X and in since .

It looks like there is no choice of non-symmetric sums in such that the assignments and define a functor from into since for any -substitutions , the maps and coincide, in general, only for -expressions without quantifications. For a -expression on containing quantifications, the two -expressions and may be different. They will be, however, the "same up to -conversion". Especially, it can be shown that they are semantically equivalent.

Lemma 4 (Semantic Equivalence).

For Σ-substitutions , the maps and are semantically equivalent in the sense that

Remark 20 (

-conversion).

The best we can hope for, if we intend to formalize the observation that the Σ-expressions and are the "same up to α-conversion", is some kind of "pseudo functor" (maybe in the sense of [31]?). For such a formalization, we should probably upgrade the sets (X) to small categories with morphisms encoding the information that two Σ-expressions are the "same up to α-conversion". The assignments and hopefully define then a "pseudo functor" from into in the sense that for any Σ-substitutions , there is a natural isomorphism between the functors and .

In light of deduction, there is no need for a formalization of -conversion! It should be quite enough to formally grasp what we have at hand besides Lemma 4.

Due to (

27), we obviously have

for the canonical substitutions

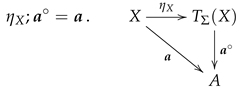

:

, thus the assignments

and

define a reflexive graph homomorphism

(see

Section 2).

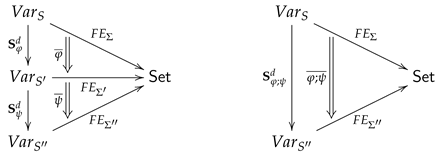

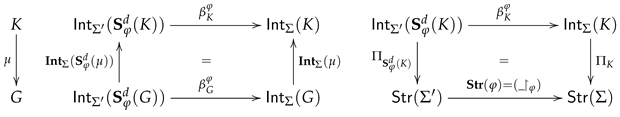

We consider an arbitrary signature morphism

. To show that the family of maps

with

X in

, defined in

Section 4.2.3, also establishes a natural transformation

between reflexive graph homomorphisms, we have to prove that for any

-substitution

the square of maps on the right below commutes.

The commutativity of the right square can be inductively shown according to the inductive definition of expressions in Definition 5 and the corresponding inductive definition of the maps

in

Section 4.2.3 and of the translation maps

in Definition 13. The basic case 1.(a) Equation follows from the fact in

Section 6.2 that the family of

-maps

constitutes a natural transformation

. This fact also ensures the second basic case 1.(b) Relational Atom due to the definition of

and the functoriality of

. The cases 2. Everything to 7. Negation can be straightforwardly proven.

The critical case 8. Quantification can only be shown under the

additional assumption that for all signature morphisms

and all disjoint

S-sets

X,

Y of variables the equation

holds. Such a coordination of choices of non-symmetric sums can be achieved if we define the choices for all sets

in a uniform way by means of one and the same choice of non-symmetric sums in

for the set

of all finite subsets of the set

of names for variables: For any disjoint

S-sets

X,

Y in

, we consider the corresponding

S-typed sets

,

. We take the chosen non-symmetric sum

of the sets

and

in

and construct its typing morphism as the cotuple

. The

S-typed set

is a non-symmetric sum of

and

in

. The desired non-symmetric sum of

X and

Y in

can be obtained via the isomorphism

:

Case 8. Quantification is then entailed by the definition of and its functoriality as well as the fact that , as a left-adjoint functor, preserves sums.

Analogously to Lemma 1, the validity of Lemma 2 is preserved since the functors and the reflexive graph homomorphisms are defined as extensions of maps between between objects to morphisms.

Corollary 3 (Composition of Expression Translations).

For any signature morphisms , and the corresponding translations of expressions and we do have:

6.4. Translation of Expressions vs Derived Operations

According to (

4), any

-substitution

represents for any

-structure

a derived operation

in the opposite direction with

for all assignments

. For any

-substitution

and any assignment

it can also inductively shown that

This entails

That is, composition in

syntactically represents the composition of derived operations! (

29) and (

5) ensure that for any

-structure

the assignments

and

define a contra-variant functor

the semantic counterpart of the reflexive graph homomorphisms

.

and

are not really matching the "original institution pattern". Nevertheless, we do have a corresponding satisfaction condition: For any

-substitution

, any

-expression

, any

-structure

and any assignment

it holds that

This is our reconstruction of the statement in Proposition 5.6 in [

17].

6.5. Statements in Context and Substitutions

As we have seen, -substitutions establish directed relationships between -expressions and . An obvious idea could be to extend now the sets of all -statements in contexts K in Definition 10 by morphisms of the form with . What should "??" be in this case? A natural proposal would be to choose the S-map .

That is, if we want to introduce morphisms between statements induced by substitutions, we probably must upgrade the concept of "binding" to S-maps of the form . In such a way, we would get morphisms like with , and thus .

As seen in

Section 6.3, the composition of substitutions will, however, not establish a category since composition will only be associative "up to

-conversions". At the moment, we do not have the capacity and/or the technical skills to find out if we would get something like a "pseudo category", in the sense of [

31], a "quasi category" [

32] or something else.