Submitted:

10 February 2025

Posted:

12 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Elaboration of the Mortar

2.2. Fiber Preparation and Conditioning of the Fibers

2.3. Physicochemical Characterization of Fibers

2.4. Mechanical Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Characterization of Fibers

3.1.1. Chemical Resistance

3.1.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

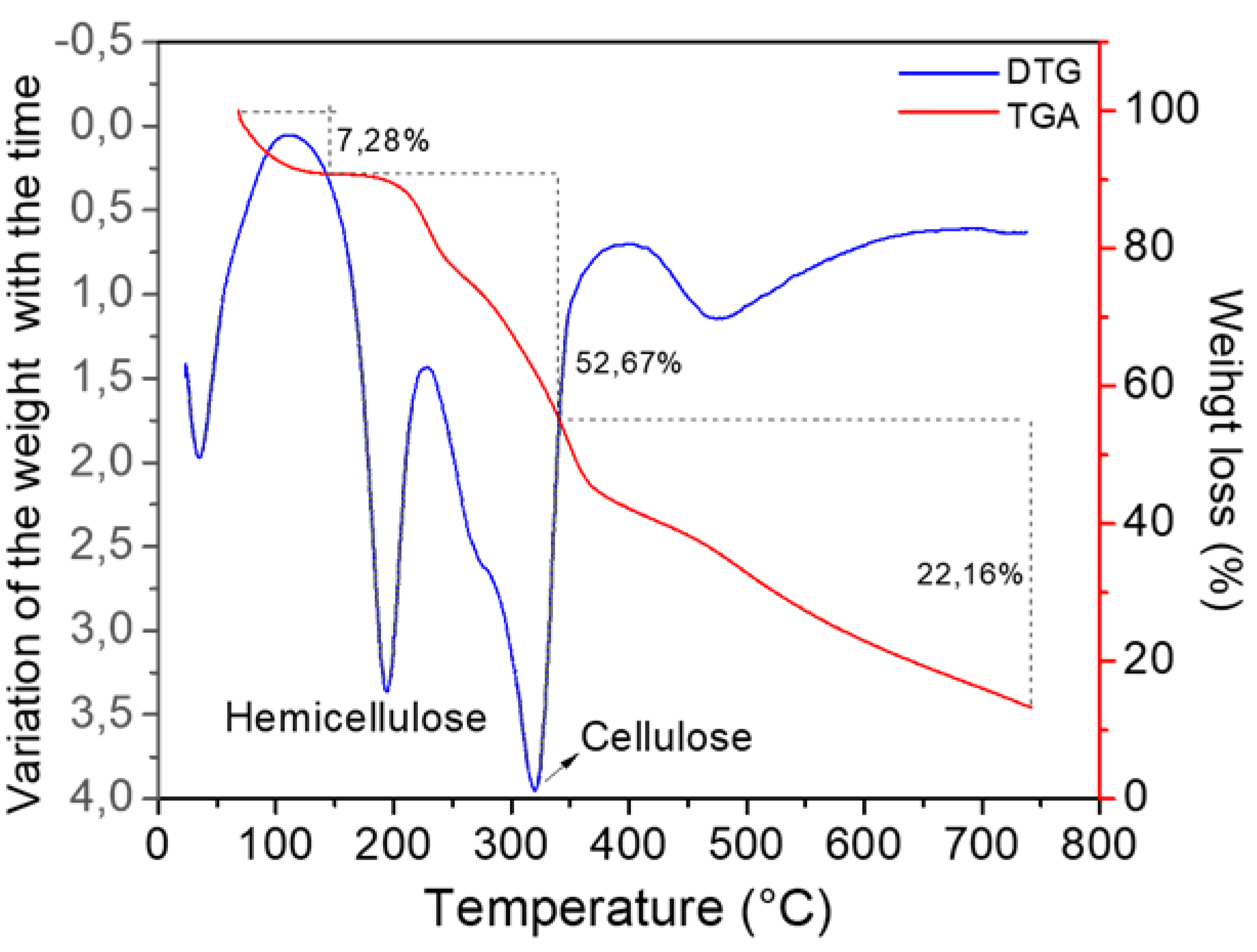

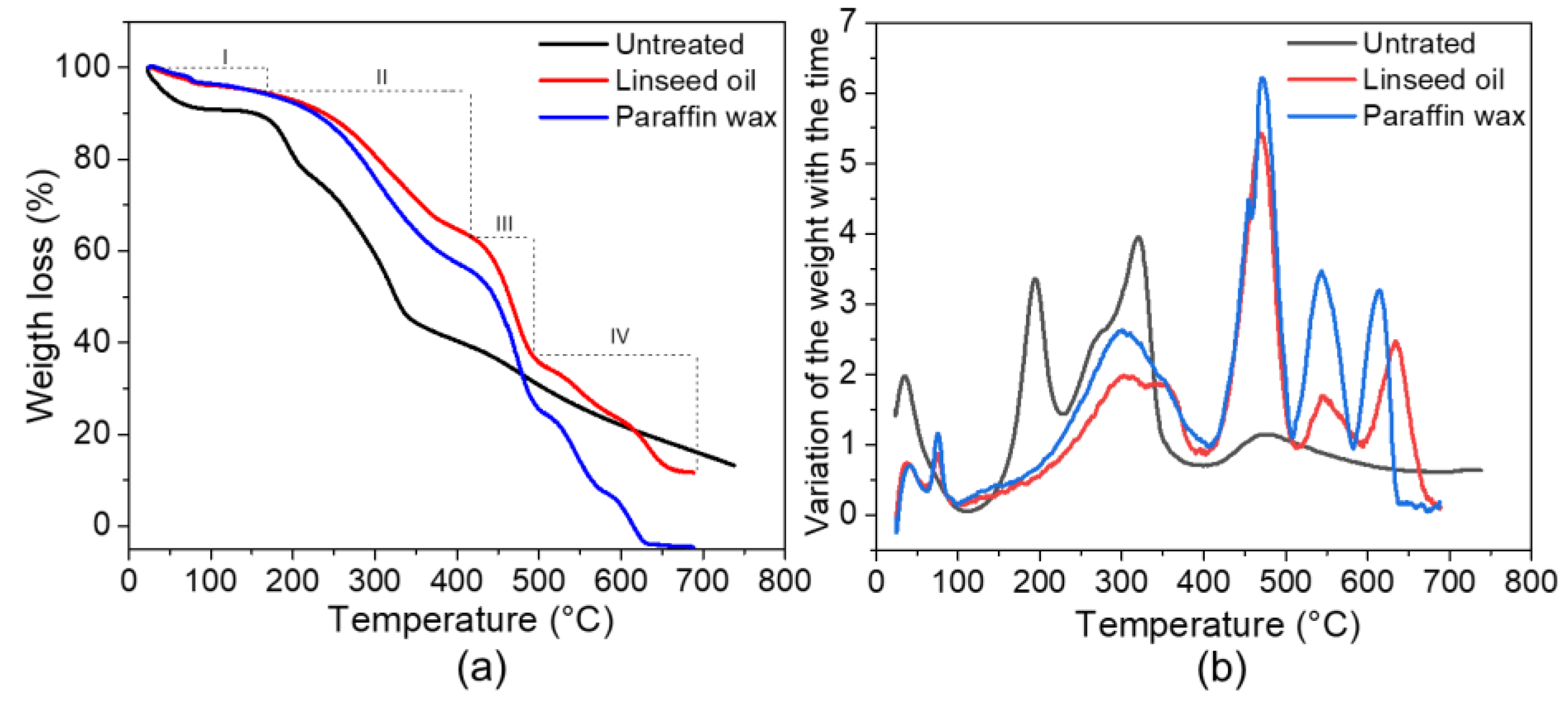

3.1.3. Thermal Analysis

3.2. Mechanical Evaluation

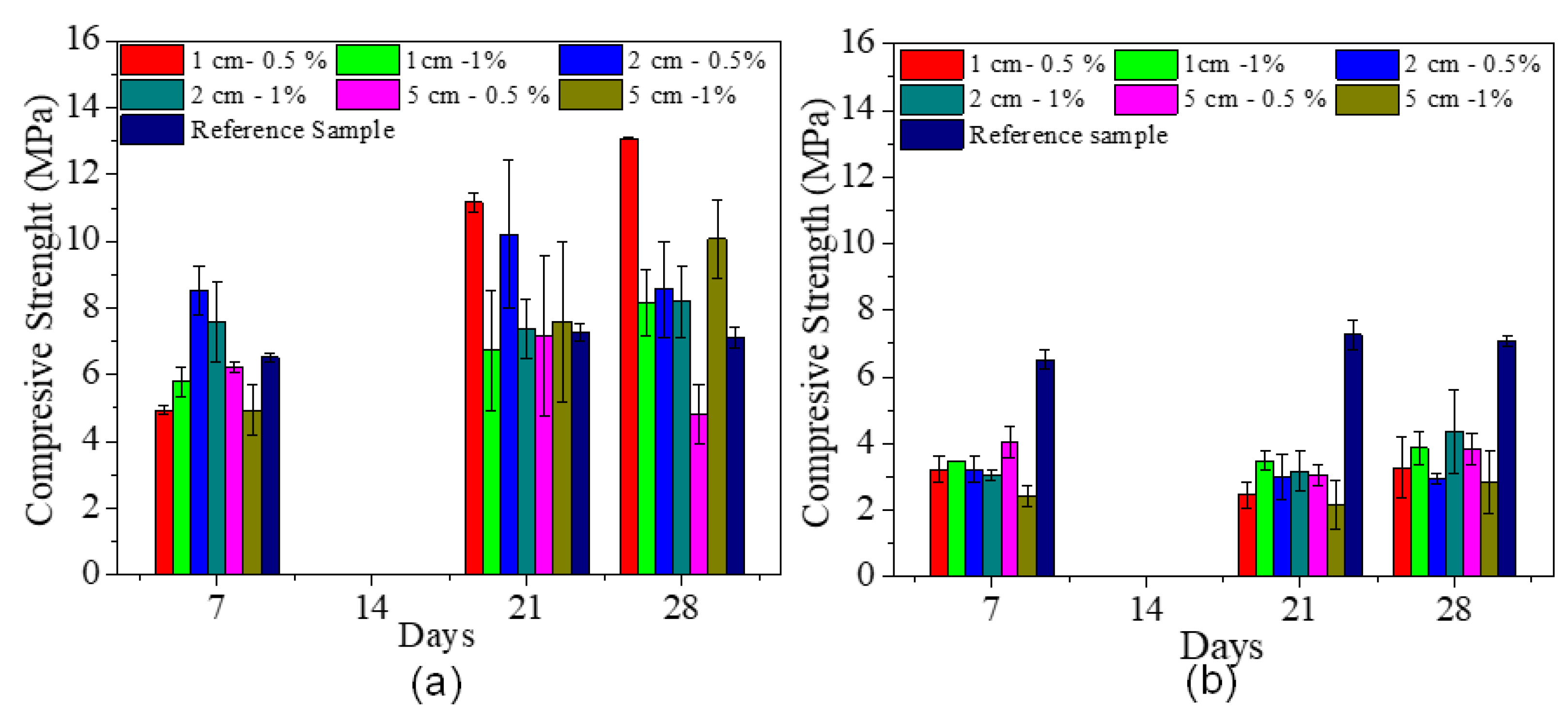

3.2.1. Compressive Strength

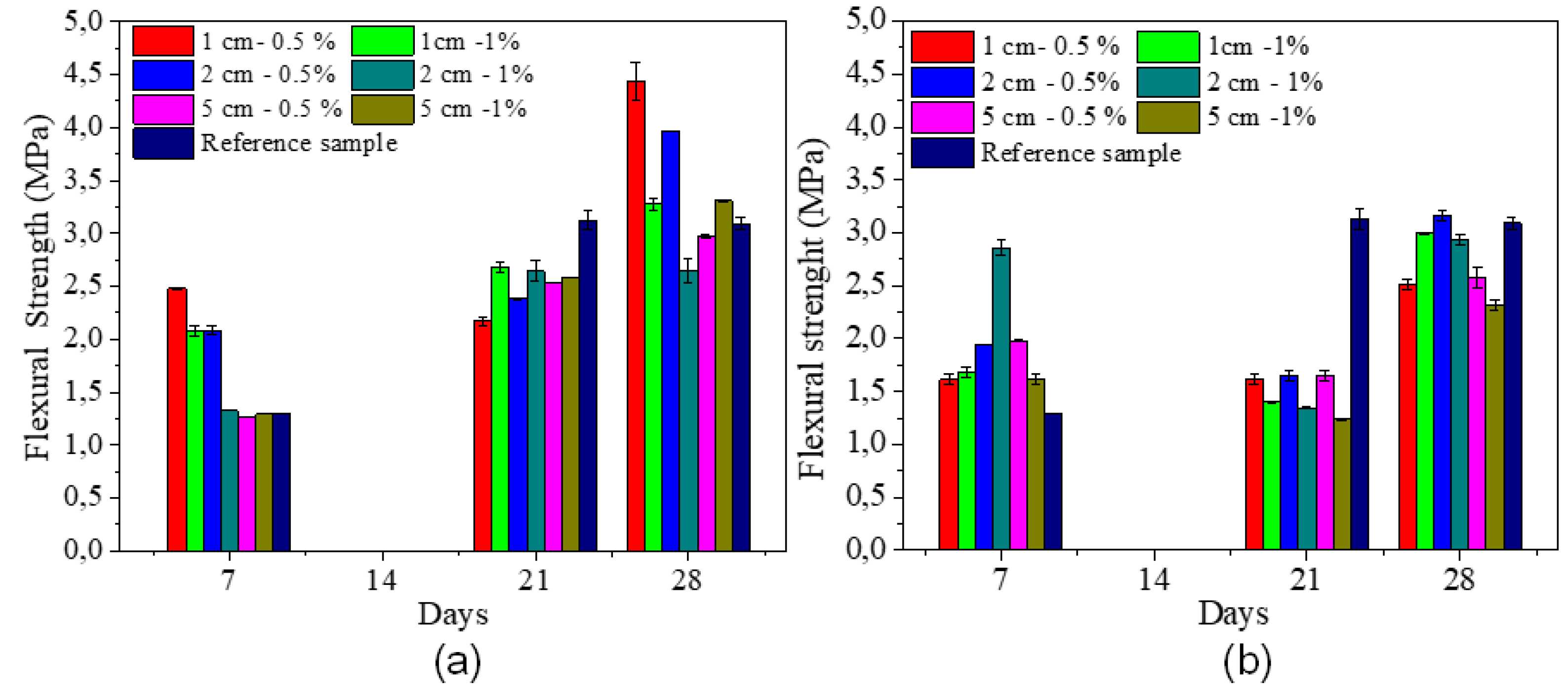

3.2.2. Flexural Strength

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thanushan, K. & Sathiparan, N. Mechanical performance and durability of banana fibre and coconut coir reinforced cement stabilized soil blocks. Materialia, 2022, vol 21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtla.2021.101309.

- Agopyan, V., Jr, H., John, V. & Cincotto, M. Developments on vegetable fibre-cement based materials in São Paulo, Brazil: An overview. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2005, vol 27, pp 527–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2004.09.004.

- Varghese, A. & Unnikrishnan, S. Mechanical strength of coconut fiber reinforced concrete. Mater. Today Proc. (2023) doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2023.05.637.

- Zou, Q., Ye, X., Huang, X., Zhang, W. & Zhang, L. Influence of elevated temperature on the interfacial adhesion properties of cement composites reinforced with recycled coconut fiber. J. Build. Eng. 2014, vol 98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.111270.

- Crucho, J. M. L., Picado-Santos, L. G. de & Neves, J. M. C. das. Assessment of the durability of cement-bound granular mixtures using reclaimed concrete aggregate and coconut fiber. Constr. Build. Mater, 2024, vol 441, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.137550.

- Osorio Saraz, J. A., Varón Aristizabal, F. & Herrera Mejía, J. A. Comportamiento mecánico del concreto reforzado con fibras de bagazo de caña de azúcar. Dyna , 2007,vol 74, pp 69–79.

- Coutts, R. S. P. A review of Australian research into natural fibre cement composites. Nat. Fibre Reinf. Cem. Compos, 2005, vol 27,pp 518–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2004.09.003.

- Arnon Bentur & Mindess Sidney. Fibre Reinforced Cementitious Composites. (CRC Press, 2014).

- Diego Sanchez de Guzman. Tecnología Del Concreto y Del Mortero. (Bhandar Editores LTDA, 2001).

- Icontec. Norma Técnica Colombiana. Concretos. Ensayo de Resistencia a la Compresión de Especímenes Cilíndricos de Concreto. NTC 673. (2010).

- ASTM C470/C470M-02. Standard Specification for Molds for Forming Concrete Test Cylinders Vertically. (2002).

- Icontec. Norma Técnica Colombiana. Concretos. métodos de ensayo para determinar la evaluación en el laboratorio y en obra, de morteros para unidades de mampostería simple y reforzada. NTC 3546. (2003).

- Resistencia a la flexión de morteros de cemento hidraúlico I.N.V.E - 324- 07. (2007).

- Llerena Encalada, A. Estudio de compuestos cementicios reforzados con fibras vegetales. Trabajo fin de master, 2014, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona.

- Acevedeo de la espriella, M. A. & Luna Velasco, M. S. Tratamiento químicos superficiales para el uso de fibras naturales en la construccioón:concretos y morteros. Monografia título Ingeniero Civil, 2021, Universidad de Cartagena.

- Juarez Alvarado, C. A. Concretos base cemento Portland reforzados con fibras naturales (Agave Lechugilla), como materiales para construcción en México. Tesis Doctoral, 2002, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León.

- Bilba, K., Arsene, M.-A. & Ouensanga, A. Study of banana and coconut fibers: Botanical composition, thermal degradation and textural observations. Bioresour. Technol. 2007,vol 98, pp 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2005.11.030.

- Hernandez-Vidal, N., Bautista, V., Morales, V., Ordóñez, W. & Osorio, E. Caracterización química de la Fibra de Coco (Cocus nucifera L.) de México utilizando Espectroscopía de Infrarrojo (FTIR). Ing. Región, 2018, vol 20, pp 67–71.

- Ceron Meneses, Y. P., Alban Bolaños, P., Grass Ramírez, J. F. & Camacho Muñoz, R. Caracterización física, química, térmica y mecánica de fibras de coco de la Costa Pacífica del Cauca con potencial como refuerzo de materiales compuestos de matriz polimérica. Biotecnol. En El Sect. Agropecu. Agroindustrial, 2024, vol 22, pp 30–42. https://doi.org/10.18684/rbsaa.v22.n2.2024.2291.

- Contreras, J., Trujillo, A., Arias, O., Perez, L. J. B. & Delgado, F. E. Espectroscopía ATR-FTIR de celulosa: aspecto instrumental y tratamiento matemático de espectros. in (2010).

- Romero, P., Marfisi, S., Oliveros, P., Rojas de Gáscue , B. & Peña, G. Obtención de Celulosa Microcristalina a partir de Desechos Agrícolas del Cambur (Musa Sapientum). Síntesis de Celulosa Microcristalina. Rev. Iberoam. Polímeros , 2014, vol 15, pp 286–300.

- Luo, Z. et al. Comparison of performances of corn fiber plastic composites made from different parts of corn stalk. Ind. Crops Prod, 2017, vol 95, pp 521–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.11.005.

- Sanou, I., Bamogo, H., Sory, N., Gansoré, A. & Millogo, Y. Effect of the coconut fibers and cement on the physico-mechanical and thermal properties of adobe blocks. Heliyon, 2024, vol 10, pp 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e38752.

- Olonade, K. A. & Savastano Junior, H. Performance evaluation of treated coconut fibre in cementitious system. SN Appl. Sci, 2023,vol 5, pp 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-023-05444-2.

- Carrillo Navarrete, F. Caracterización estructural de fibras lyocell y su comportamiento frente a procesos de degradación, Tesis Doctoral, 2002, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya.

- Ssemujju Lubowa, P., Ndiritu, H., Oketch, P. & Mutua, J. Coconut Fiber Pyrolysis: Bio-Oil Characterization for Potential Application as an Alternative Energy Source and Production of Bio-Degradable Plastics. World Journal of Engineering and Technology, 2024, vol. 12.

- Moshi, A. A. M. et al. Characterization of a new cellulosic natural fiber extracted from the root of Ficus religiosa tree. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, vol 142, pp 212–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.09.094.

- Paricaguán, B. et al. Degradación térmica de fibras de coco con tratamiento químico provenientes de mezclas de concreto (estudio cinético). Rev. Ing. UC, 2013, 20, pp 60–67.

- Pineda Gomez, P., Coral, D. F., Rivera Ramos, D. & Rosales Rivera, A. Estudio de las propiedades térmicas de harinas de maíz producidas por tratamiento térmico-alcalino. Ingeniería y Ciencia, 2011, vol. 7, pp 119–142.

- Ferreira, S. R., Silva, F. de A., Lima, P. R. L. & Toledo Filho, R. D. Effect of fiber treatments on the sisal fiber properties and fiber–matrix bond in cement based systems. Constr. Build. Mater, 2015, 101, pp 730–740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.10.120.

- Wei, J. & Meyer, C. Degradation rate of natural fiber in cement composites exposed to various accelerated aging environment conditions. Corros. Sci, 2014, 88, pp 118–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2014.07.029.

- Jimenez, A., Betancourt, S., Gañán, P. & Cruz, L. Degradación térmica de fibras naturales procedentes de la calceta de plátano. (Estudio cinético). Rev. Latinoam. Metal. Mater, 2009, 29, pp 215–219.

- Juarez, C., Valdes, P. & Durán, A. Fibras naturales de lechuguilla como refuerzo en materiales de construcción. Revista Ingeniería de Construcción, 2004, vol. 19, pp 83-92.

- Wei, J. & Meyer, C. Utilization of rice husk ash in green natural fiber-reinforced cement composites: Mitigating degradation of sisal fiber. Cem. Concr. Res, 2016, vol 81, pp 94–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2015.12.001.

- Aziz, M. A., Paramasivam, P. & Lee, S. L. Prospects for natural fibre reinforced concretes in construction. Int. J. Cem. Compos. Lightweight Concr, 1981, vol 3, pp 123–132.

- Chakraborty, S., Kundu, S. P., Roy, A., Adhikari, B. & Majumder, S. B. Polymer modified jute fibre as reinforcing agent controlling the physical and mechanical characteristics of cement mortar. Constr. Build. Mater, 2024, vol 49, pp 214–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.08.025.

- Fujiyama, R., Darwish, F. & Pereira, M. V. Mechanical characterization of sisal reinforced cement mortar. Theor. Appl. Mech. Lett, 2014, vol 4, pp 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1063/2.1406102.

- Yan, L., Kasal, B. & Huang, L. A review of recent research on the use of cellulosic fibres, their fibre fabric reinforced cementitious, geo-polymer and polymer composites in civil engineering. Compos. Part B Eng, 2016, vol 92, pp 94–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2016.02.002.

- Hwang, C.-L., Tran, V.-A., Hong, J.-W. & Hsieh, Y.-C. Effects of short coconut fiber on the mechanical properties, plastic cracking behavior, and impact resistance of cementitious composites. Constr. Build. Mater, 2016, vol 127, pp 984-992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.09.118.

- Quintero García, S. L. & González Salcedo, L. O. Uso de fibra de estopa de coco para mejorar las propiedades mecánicas del concreto. Ing. Desarro, 2011, vol 20, pp 134–150.

- Gonzalez Salcedo, L. O. Influencia de los componentes del concreto reforzado con fibras en sus propiedades mecánicas. (2013).

| Fiber type | Protective substance |

Length (cm) |

Percentage by weight |

Number of specimens |

|

Coconut fiber |

Linseed Oil |

1 | 0,5 | 12 |

| 1 | 12 | |||

| 2 | 0,5 | 12 | ||

| 1 | 12 | |||

| 5 | 0,5 | 12 | ||

| 1 | 12 | |||

|

Paraffin wax |

1 | 0,5 | 12 | |

| 1 | 12 | |||

| 2 | 0,5 | 12 | ||

| 1 | 12 | |||

| 5 | 0,5 | 12 | ||

| 1 | 12 | |||

| Control mortar | 6 | |||

| Total | 150 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).