Introduction

Medical decision-making requires clinicians to rely on available scientific evidence to ensure accurate diagnoses and determine the most effective course of treatment. Ideally, these decisions are driven by a solid foundation of empirical data, including randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews and large-scale observational studies (Young et al., 2020; McFadden 2023). However, in real-world clinical practice, such high-quality evidence is not always available. Physicians frequently encounter cases where data are incomplete, unreliable or contradictory, creating an epistemic gap that challenges the traditional models of evidence-based medicine (Meyer et al., 2021). The question that arises in these situations is whether a rational and justifiable medical decision can still be made and if so, what methodologies can be employed to navigate uncertainty (Guerdan et al., 2023). The absence of scientific evidence in medical decision-making can result from multiple factors. Some medical conditions are rare or under-researched, limiting the availability of robust clinical trials. Emerging diseases and novel therapeutic interventions, such as the COVID-19 vaccine, often lack long-term studies, compelling doctors to make decisions based on preliminary findings, clinical observations, and theoretical reasoning. Additionally, the nature of medical evidence itself can be contested, with studies producing conflicting results due to differences in methodology, sample size or statistical interpretation (Kaplanis et al., 2020). The hierarchy of evidence in evidence-based medicine traditionally prioritizes randomized trials over observational studies, expert opinions and mechanistic reasoning (Wang et al., 2023). Yet, in many medical situations, reliance on lower-tier evidence is unavoidable (Hammond et al., 2021; Wan et al., 2022). The challenge, then, is how to systematically incorporate diverse knowledge sources while maintaining the reliability of medical judgments.

Bayesian models provide a mathematical framework for integrating diverse sources of information and dynamically updating degrees of belief as new data emerges. However, they assume that probabilities can be assigned to all relevant variables, which is not always feasible in clinical contexts with missing or non-quantifiable data. Moreover, Bayesian inference does not account for the cognitive and social dynamics that shape how medical professionals weigh different forms of evidence, including biases, heuristics and collective knowledge. Given these limitations, alternative frameworks are needed to formalize medical decision-making under uncertainty while remaining pragmatic in real-world clinical environments.

We propose a heuristic belief-aggregation model (henceforward HAM) that quantifies degrees of belief by integrating multiple epistemic sources relevant to medical judgment. The primary objective is to provide a structured yet flexible method that allows clinicians to make justified treatment decisions even in the absence of robust empirical data. Our approach assigns weighted values to different categories of evidence, including scientific literature, expert consensus, individual clinical experience, logical reasoning. By summing these weighted values, a cumulative score is generated, indicating whether a particular treatment decision should be accepted or rejected. Unlike standard Bayesian approaches, which require well-defined probability distributions, our model accommodates qualitative and subjective factors that often play a crucial role in clinical reasoning. A key feature of our approach is its explicit acknowledgment of both externalist and internalist sources of justification. Externalist sources, such as systematic reviews and randomized trials, provide objective, data-driven insights forming the backbone of evidence-based medicine (Goldman, 1986; Alston 1989). Internalist sources, including individual expertise, peer opinions and inferential reasoning, contribute to the interpretation and contextualization of available data (Chisholm 1989; Haack 1991; Ben-Moshe 2019). HAM systematically incorporates these elements, ensuring that decision-making is not solely dependent on statistical inference but also accounts for the realities of medical practice.

To illustrate the utility of our heuristic model, we present a hypothetical case study involving the use of an antibiotic in a scenario where conventional guidelines do not offer a clear directive. By applying our belief-aggregation method, we demonstrate how different knowledge sources contribute to a final treatment decision. In the following sections, we discuss the theoretical foundations of our approach, outlining its relationship to existing decision-making models in medicine. Then, we detail the methodological framework, specifying how different sources of knowledge are weighted and integrated. A practical application is presented through the case study, followed by a discussion of the HAM’s advantages, limitations and prospects for future refinement.

Materials and Methods

We built a structured heuristic framework designed to assist medical decision-making when sufficient empirical data are unavailable, unreliable or contradictory. The approach integrates multiple sources of knowledge, both empirical and non-empirical, to form a quantifiable degree of belief regarding a medical decision. We follow a sequential process that begins with the formulation of a medical question and proceeds through evidence collection, source classification, numerical assignment, aggregation and decision-making.

The first step is to define the medical question in a standardized, logical format, ensuring that the problem under investigation can be systematically analysed. The medical question is framed as a conditional statement of the form “if X, then Y,” where X represents a specific medical intervention and Y denotes an expected clinical outcome. The question is structured to have a binary response of either “yes” or “no” to facilitate decision-making without ambiguity (Ramsey 1929; Carnap 1974; Taylor and Raden, 2007; Misak 2020). This format is chosen to align with classical logical structures and expert system frameworks, which prioritize clear conclusions.

The next step consists of the identification and collection of all available sources of knowledge that may contribute to the decision-making process. This includes formal scientific evidence from medical literature, clinical expertise derived from practitioners’ experience, collective knowledge within the medical community, inferential reasoning based on logical principles and additional modifying factors such as cognitive biases and confounding variables.

The collected information is categorized into two broad epistemic domains: externalist sources, which originate from outside the individual decision-maker and relyi on empirical validation (Armstrong 1973; Supriyanto 2023) and internalist sources, which depend on the subjective interpretation, expertise and reasoning of the clinician (Feldman and Conee, 1985; BonJour 1985; Supriyanto 2023).

The externalist sources consist of levels of evidence classified according to the widely accepted hierarchical frameworks in evidence-based medicine. The highest-ranked source of knowledge in this category is systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials, considered the gold standard for determining treatment efficacy (Burns et al., 2011). Randomized controlled trials without systematic synthesis follow in the hierarchy, providing a strong, albeit slightly less robust, form of evidence (OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group, 2011; Antoniou 2021). Non-randomized controlled cohort studies and observational studies come next, reflecting a lower level of empirical rigor but still contributing valuable insights, especially in cases where randomized trials are infeasible. The weakest form of externalist evidence includes case series, case reports and expert opinion without formal empirical validation, which are often used as a last resort when higher levels of evidence are unavailable (Greenhalgh 1997; Debray et al., 2023). Further, model-based statistical approaches could be able to predict patient outcomes with discrete accuracy, improving decision-making related to medical treatments (Chekroud et al., 2024). The growing momentum of machine learning–based medical decision support systems in health care is creating high expectations, but the performance is not (yet?) able to overtake human decision-making (Vasey et al., 2021; Luo et al., 2023).

The internalist sources encompass a broader range of non-empirical factors influencing medical judgment (Heyting 1930). Individual clinical experience plays a significant role, incorporating knowledge gained from repeated exposure to similar cases, pattern recognition and intuitive decision-making confidence (Rosenberg, 2002; Fields et al., 2024). This category also includes collective medical knowledge, which is derived from discussions among practitioners, expert consensus and the collective wisdom of the medical community (Monteiro et al., 2020). According to the wisdom of crowds principles, accurate estimates can be obtained by combining the judgements of different individuals, since the average of just two judgements from different people (between-person aggregation) is more accurate than a large number of repeated judgements from the same person (within-person aggregation) (van Dolder et al., 2018). Logical reasoning is another crucial internalist issue, incorporating deductive inference, mechanism-based thinking and theoretical extrapolation (Suppes 1960; Vasey et al., 2021). Additionally, modifying factors such as cognitive biases, heuristics and decision-making fallacies are recognized for their potential to distort judgment (Gettier 1963; Taleb 2007; Beldhuis et al., 2021; Loncharich et al., 2023).

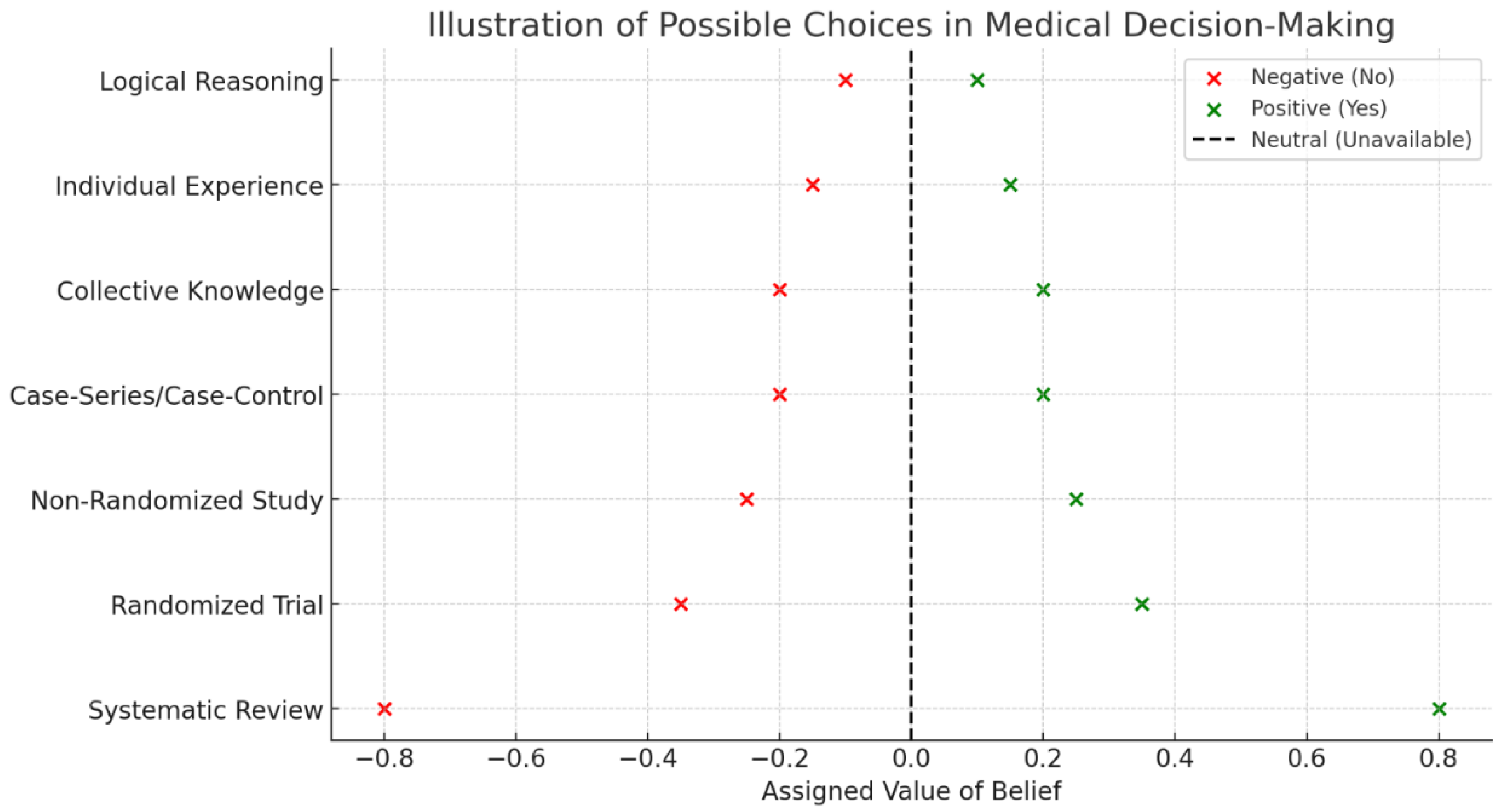

The next step consists of numerical assignment of values to each source. This involves the allocation of weighted scores reflecting the relative reliability and influence of each knowledge source. A numerical scale is used, where positive values indicate support for the proposed medical intervention, negative values signify opposition and zero values denote neutrality or the absence of relevant information (

Figure 1). The assignment of numerical values is driven by the relative strength of each source within the hierarchy of evidence, with higher-ranked sources receiving larger numerical weights. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are assigned to have the highest positive or negative values due to their strong empirical foundation, while lower-ranked sources receive progressively smaller values. Individual clinical experience, collective knowledge and logical reasoning are assigned lower values, reflecting their contributory role but acknowledging their susceptibility to subjective bias. Indeed, confounding factors, including cognitive biases and emotional influences, stand for modifiers that may adjust or temper the assigned values.

The next step involves the aggregation of values to generate a cumulative score representing the overall degree of belief. The summation of all assigned values produces a single numerical outcome, which is interpreted according to predefined thresholds. If the cumulative score is positive, the treatment decision is endorsed; if the score is negative, the treatment is rejected. The absolute magnitude of the score provides an indication of the degree of confidence in the decision, with higher values reflecting stronger epistemic support. Cases where the score is near zero indicate a state of epistemic equilibrium, where neither approval nor rejection is strongly justified.

In sum, HAM aims to integrate diverse knowledge sources into a single quantitative framework. The method accommodates both empirical and non-empirical factors, ensuring that decision-making remains structured even in the absence of definitive scientific evidence.

Next, we apply our methodology to a case study examining the hypothetical use of an antibiotic termed Napcar for treating severe diabetic microangiopathy.

Results

We analysed a case study exploring the potential use of the hypothetical antibiotic Napcar in treating severe diabetic microangiopathy. The medical question under evaluation was whether administering Napcar twice daily instead of the conventional once-daily regimen would yield superior clinical outcomes. We followed our structured methodology, beginning with the formulation of the medical question and proceeding through source identification, classification, numerical assignment and aggregation.

To address the specific question, no systematic reviews or meta-analyses were available, resulting in an assigned value of zero for this source (

Figure 2). A single randomized controlled trial had been conducted on the conventional use of Napcar, providing evidence that the once-daily regimen was effective, leading to a negative value assignment of -0.35. Non-randomized cohort studies and observational data were not available, contributing additional zero values. A case series had reported anecdotal evidence supporting twice-daily administration, warranting a positive value assignment of +0.2. Collective medical knowledge, based on informal expert opinions, contributed a small positive value of +0.1, reflecting cautious support without empirical validation. Individual clinical experience also supported the possibility of twice-daily administration, contributing an additional +0.1. Logical reasoning, based on pharmacokinetic properties indicating a short half-life of Napcar, provided another +0.1 in favor of increased frequency of administration. Aggregating these values resulted in a cumulative score of +0.15, indicating a slight preference for the twice-daily regimen despite the presence of a contradictory randomized trial.

The cumulative belief score must be interpreted within the context of decision-making thresholds. A strongly negative score would have reinforced the existing standard of care, discouraging deviation from the once-daily regimen, while a strongly positive score would have provided compelling justification for the alternative regimen. The final belief score of +0.15 indicated a weak but measurable preference for the adjusted dosing schedule, suggesting that, within the context of limited empirical data, there was a justifiable rationale for considering the alternative treatment approach of twice-daily administration.

Conclusions

We provide a structured approach to medical decision-making when empirical data are insufficient, unreliable or conflicting. The novelty of our approach lies in its explicit integration of both empirical and non-empirical sources of knowledge into a unified, quantitative framework. Our model acknowledges that real-world medical decision-making incorporates a broader range of influences. Unlike purely probabilistic approaches, such as Bayesian inference, which require precise prior probabilities, our heuristic method offers a simpler, more adaptable structure that accommodates qualitative factors, including cognitive biases, personal experience and expert consensus. The innovation is the explicit numerical weighting of different sources of knowledge, allowing for a transparent approach to decision-making under uncertainty. The choice of numerical values assigned to each epistemic source is based on a balance between the strength of evidence and its practical influence on decision-making, ensuring that the framework remains both scientifically grounded and clinically useful. The numerical scale guarantees that highly reliable sources exert a dominant influence on the final belief score, while still allowing room for other factors to contribute meaningfully. The highest positive and negative values are assigned to systematic reviews due to their comprehensive nature and reliability, followed by decreasing weights for randomized trials, observational studies and case-series data. Lower values are assigned to collective knowledge, individual experience and logical reasoning, reflecting their less formalized and more context-dependent nature. Further, our approach mitigates the risk of subjective bias dominating clinical reasoning while still preserving the flexibility needed for real-world application. Alternative numerical assignments could be used, but they would require rigorous justification and empirical validation to maintain consistency and predictive reliability.

In sum, the interpretability and reproducibility of the numerical belief score ensures transparency in the decision-making process, allowing clinicians to see exactly how different sources contribute to the outcome.

Compared to other techniques, HAM offers several advantages. Traditional Bayesian methods, while mathematically rigorous, require precise probability distributions and often struggle to incorporate qualitative factors such as cognitive biases, expert judgment and heuristic reasoning. HAM circumvents this issue by using a structured yet flexible numerical system accommodating both statistical and non-statistical evidence. Still, machine learning-based decision-support systems, while increasingly sophisticated, often lack transparency and interpretability, making it difficult for clinicians to understand how a given recommendation is derived. In turn, our model provides an explainable decision-making process, allowing physicians to see exactly how different sources contribute to the outcome. Unlike purely intuitive decision-making, which can be highly variable and prone to bias, HAM ensures that all relevant epistemic inputs are explicitly considered and systematically weighted.

The potential applications of HAM extend beyond the Napcar case study to a wide range of medical decision-making scenarios. In emergency medicine, where rapid decisions are required despite incomplete information, HAM could provide a way to integrate available evidence and professional judgment. In rare diseases, where large-scale clinical trials are often lacking, the model could help synthesize case reports, expert opinions and mechanistic reasoning into a coherent treatment recommendation. In situations involving emerging diseases or novel treatments where data are limited, our method could be adapted to continuously update belief scores as new evidence becomes available. Additionally, HAM could be implemented in artificial intelligence-driven decision-support systems, enhancing the ability of clinical algorithms to incorporate expert knowledge and qualitative reasoning into automated recommendations. Also, HAM has broader implications for epistemology and medical ethics. The process of forming justified medical beliefs without sufficient empirical evidence raises fundamental questions about the nature of knowledge, uncertainty and the role of expert judgment in healthcare. The strain between empirical rigor and pragmatic necessity underscores the need for a balanced approach that neither dismisses non-empirical factors outright, nor overemphasizes subjective reasoning at the expense of scientific validity. Additionally, expanding HAM to incorporate sensitivity analysis would allow for a better understanding of how variations in individual epistemic contributions influence overall decision confidence.

The application of HAM to the hypothetical case study of the antibiotic Napcar demonstrates how our structured decision-making framework can integrate multiple epistemic sources, assign numerical values to each and generate a cumulative belief score to guide clinical choices. Even when robust empirical evidence is available, such as the randomized controlled trial in our case study, alternative knowledge sources may still exert influence on medical decision-making. This means that medical decision-making is not purely data-driven but also shaped by contextual understanding and pragmatic considerations. The results further highlight the importance of explicitly considering cognitive biases and confounding factors. Although not assigned discrete numerical values in this study, these factors were recognized as potential modifiers of judgment. HAM could be tested through controlled or retrospective studies in which physicians are presented with complex clinical cases and asked to make decisions using different methods, with their choices compared for consistency and justification. We hypothesize that our model will perform comparably to Bayesian approaches in predictive accuracy but with greater ease of use.

Despite its advantages, HAM has several limitations. Our assignment of numerical values to different epistemic sources remains somewhat subjective. While our hierarchy is grounded in evidence-based medicine principles, different weighting schemes could yield different results. Our method does not erase uncertainty but rather provides a structured way to navigate it; decisions with low belief scores may still require further empirical research or additional clinical judgment. HAM assumes that different epistemic sources can be meaningfully combined into a single numerical score, which may not always be the case, particularly when sources directly contradict each other. Additionally, while our model accounts for cognitive biases, it does not prevent them entirely and clinicians must remain vigilant against over-reliance on subjective influences. Still, HAM’s reliance on numerical assignments introduces an inherent degree of subjectivity, as the weighting of different sources depends on heuristic judgment rather than a strictly algorithmic process. The relatively low cumulative score in the Napcar case illustrates the challenge of making high-confidence decisions when empirical evidence is conflicting or sparse. Furthermore, while the approach successfully synthesizes various epistemic sources, it does not resolve the underlying issue of limited high-quality data, meaning that decisions remain probabilistic rather than definitive. Future refinements, such as expert calibration of numerical weights and sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of belief scores, could enhance HAM’s reliability and applicability.

In conclusion, we introduce a structured and quantifiable approach to medical decision-making when empirical data are lacking. By integrating multiple sources of knowledge, assigning numerical values and generating a cumulative belief score, our model, despite its limitations, provides a systematic framework to tackle complex treatment decisions.

Author Contributions

The Author performed: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical analysis, obtained funding, administrative, technical and material support, study supervision.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the Author.

Consent for publication

The Author transfers all copyright ownership, in the event the work is published. The undersigned author warrants that the article is original, does not infringe on any copyright or other proprietary right of any third part, is not under consideration by another journal and has not been previously published.

Availability of data and materials

all data and materials generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript. The Author had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the author used ChatGPT to assist with data analysis and manuscript drafting. After using this tool, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Competing interests

The Author does not have any known or potential conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations within three years of beginning the submitted work that could inappropriately influence or be perceived to influence, their work.

References

- Alston, William P., 1989. Epistemic Justification: Essays in the Theory of Knowledge. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Antoniou, A. 2021. What is a data model? Euro Jnl Phil Sci 11, 101. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, David, 1973. Belief, Truth and Knowledge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Beldhuis, Iris E; Ramesh S Marapin, You Yuan Jiang, Nádia F Simões de Souza, Artemis Georgiou, et al. 2021. Cognitive biases, environmental, patient and personal factors associated with critical care decision making: A scoping review. J Crit Care. 2021 Aug:64:144-153. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Moshe, Nir. 2019. The internal morality of medicine: a constructivist approach. Synthese 196 (11):4449-4467. [CrossRef]

- BonJour, Laurence, 1985. The Structure of Empirical Knowledge. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Burns, Patricia B.; Rohrich, Rod J.; Chung, Kevin C. (July 2011). "The Levels of Evidence and Their Role in Evidence-Based Medicine". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 128 (1): 305–310. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carnap R. 1974. An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science. Ed. Gardner M, 1995, Dover Publications, Inc., Mineona, New York. ISBN-13: 978-0486283180.

- Chekroud, Adam M; Matt Hawrilenko, Hieronimus Loho, Julia Bondar, Ralitza Gueorguieva, et al. 2024. Illusory generalizability of clinical prediction models. Science. 2024 Jan 12;383(6679):164-167. [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, Roderick, 1989. Theory of Knowledge, 3rd edition. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Debray, Thomas P A; Gary S Collins, Richard D Riley, Kym I E Snell, Ben Van Calster, et al. 2023. Transparent reporting of multivariable prediction models developed or validated using clustered data (TRIPOD-Cluster): explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2023;380:e071058.

- Feldman, Richard and Earl Conee, 1985. “Evidentialism.” Philosophical Studies, 48, pp. 15-34.

- Fields, by Chris; James F. Glazebrook, Michael Levin. 2024. Principled Limitations on Self-Representation for Generic Physical Systems. Entropy 2024, 26(3), 194. [CrossRef]

- Gettier, Edmund, 1963. “Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?” Analysis, 23, pp. 121-123. [CrossRef]

- Goldman, Alvin, 1986. Epistemology and Cognition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Greenhalgh T. July 1997. How to read a paper. Getting your bearings (deciding what the paper is about). BMJ. 315 (7102): 243–246. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guerdan, Luke; Amanda Coston, Kenneth Holstein, Zhiwei Steven Wu. 2023. Counterfactual Prediction Under Outcome Measurement Error. FAccT '23: Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency.

- Haack, Susan, 1991. “A Foundherentist Theory of Empirical Justification,” In Theory of Knowledge: Classical and Contemporary Sources (3rd ed.), Pojman, Louis (ed.), Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Hammond, MEH; Josef Stehlik, Stavros G. Drakos, Abdallah G. Kfoury. 2021. Bias in Medicine. Lessons Learned and Mitigation Strategies. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2021 Jan; 6(1): 78–85. [CrossRef]

- Heyting, Arend. 1930. Die formalen Regeln der intuitionistischen Logik I, II, III. Sitzungsberichte der preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (in German). pp. 42–56, 57–71, 158–169. In three parts.

- Kaplanis, J., Samocha, K.E., Wiel, L. et al. 2020. Evidence for 28 genetic disorders discovered by combining healthcare and research data. Nature 586, 757–762 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Lewis, David. 1973. Counterfactuals and Comparative Possibility. Journal of Philosophical Logic. 2 (4). [CrossRef]

- Loncharich, Michael F, Rachel C Robbins, Steven J Durning, Michael Soh, Jerusalem Merkebu. 2023. Cognitive biases in internal medicine: a scoping review. Diagnosis (Berl). 2023 Apr 21;10(3):205-214. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Yuan; Richard G. Wunderink, Donald Lloyd-Jones. 2023. Proactive vs Reactive Machine Learning in Health Care -Lessons From the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA. 2022;327(7):623-624. [CrossRef]

- McFadden, Johnjoe. 2023. Razor sharp: The role of Occam's razor in science. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2023 Dec;1530(1):8-17. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Ashley N D; Traber D Giardina, Lubna Khawaja, Hardeep Singh. 2021. Patient and clinician experiences of uncertainty in the diagnostic process: Current understanding and future directions. Patient Educ Couns. 2021 Nov;104(11):2606-2615. [CrossRef]

- Misak C. 2020. Frank Ramsey: A Sheer Excess of Powers. OUP Oxford. ISBN-13: 978-0198755357.

- Monteiro, Sandra; Jonathan Sherbino, Jonathan S. Ilgen, Emily M. Hayden, Elizabeth Howey and Geoff Norman. The effect of prior experience on diagnostic reasoning: exploration of availability bias. Diagnosis (Berl). 2020 Aug 27;7(3):265-272. [CrossRef]

- OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group. 2011. The Oxford 2011 Levels of Evidence. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Available online: http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653.

- Ramsey FP. 1929. Philosophy. In: The Foundations of Mathematics and Other Logical Essays, R. B. Braithwaite (ed.), second impression, 1950, Routledge &Kegan Paul LTD, London.

- Rosenberg, Charles E. 2002. The Tyranny of Diagnosis: Specific Entities and Individual Experience. Milbank Q. 2002 Jun; 80(2): 237–260. [CrossRef]

- Suppes, P. (1960). A comparison of the meaning and uses of models in mathematics and the empirical sciences. Synthese, 12(2-3), 287–301.

- Supriyanto S. 2023. Justification Theory of Internalism VS Externalism. IJSSHR. volume 06 issue 02 february 2023. [CrossRef]

- Taleb NN. 2007. The Black Swan: Second Edition: The Impact of the Highly Improbable: With a new section: "On Robustness and Fragility”. Random House Publishing Group; 2° ed., 2010. ISBN-13: 978-0812973815.

- Taylor, James; Raden, Neil (2007). Smart (Enough) Systems. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-234796-2.

- van Dolder, D., van den Assem, M.J. The wisdom of the inner crowd in three large natural experiments. Nat Hum Behav 2, 21–26 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Vasey, Baptiste; Stephan Ursprung, Benjamin Beddoe, Elliott H. Taylor, Neale Marlow, et al. 2021. Association of Clinician Diagnostic Performance With Machine Learning–Based Decision Support Systems - A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e211276. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Bohua; Brian Caffo, Swaroop Vedula. 2022. A Unified Framework on Generalizability of Clinical Prediction Models. Front. Artif. Intell. Volume 5 - 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Shirley V.; Sebastian Schneeweiss, the RCT-DUPLICATE Initiative. 2023. Emulation of Randomized Clinical Trials With Nonrandomized Database Analyses: Results of 32 Clinical Trials. JAMA;329(16):1376-1385. [CrossRef]

- Young, Paul J.; Christopher P. Nickson anders Perner. 2020. When Should Clinicians Act on Non–Statistically Significant Results From Clinical Trials? JAMA. 2020;323(22):2256-2257. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).