Submitted:

10 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

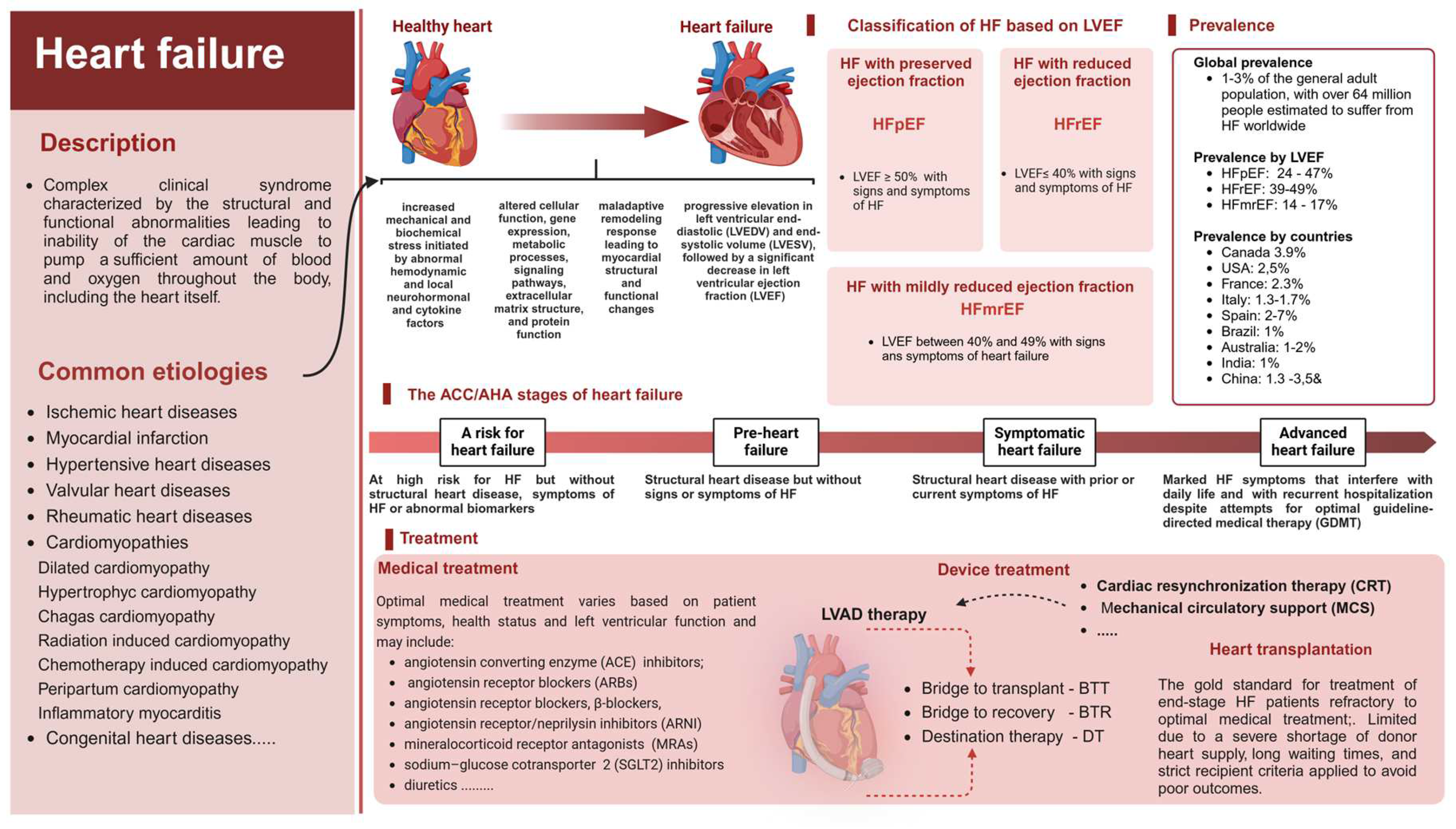

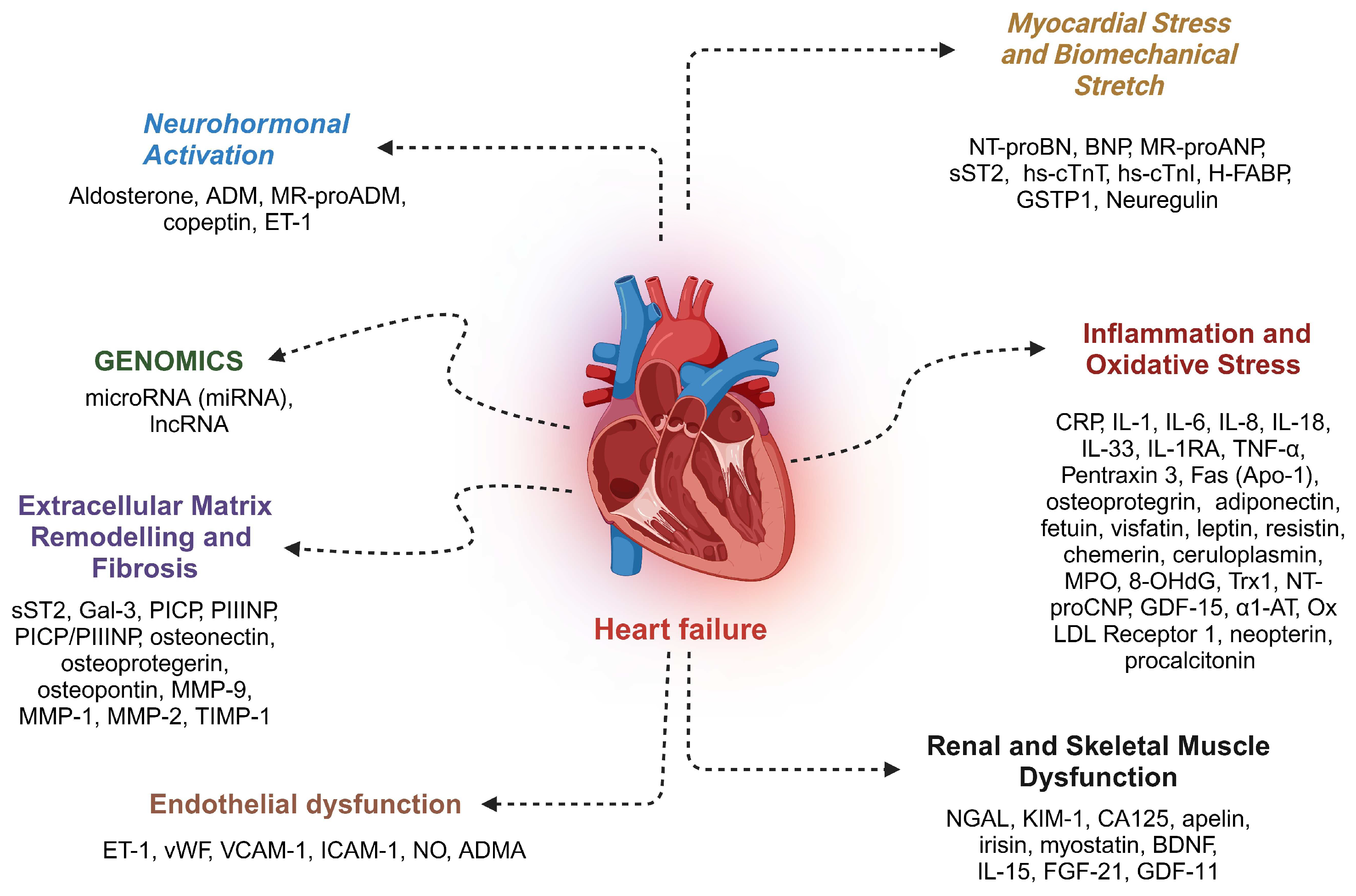

1. Introduction

2. Left Ventricular Assist Devices

3. Noncoding RNAs

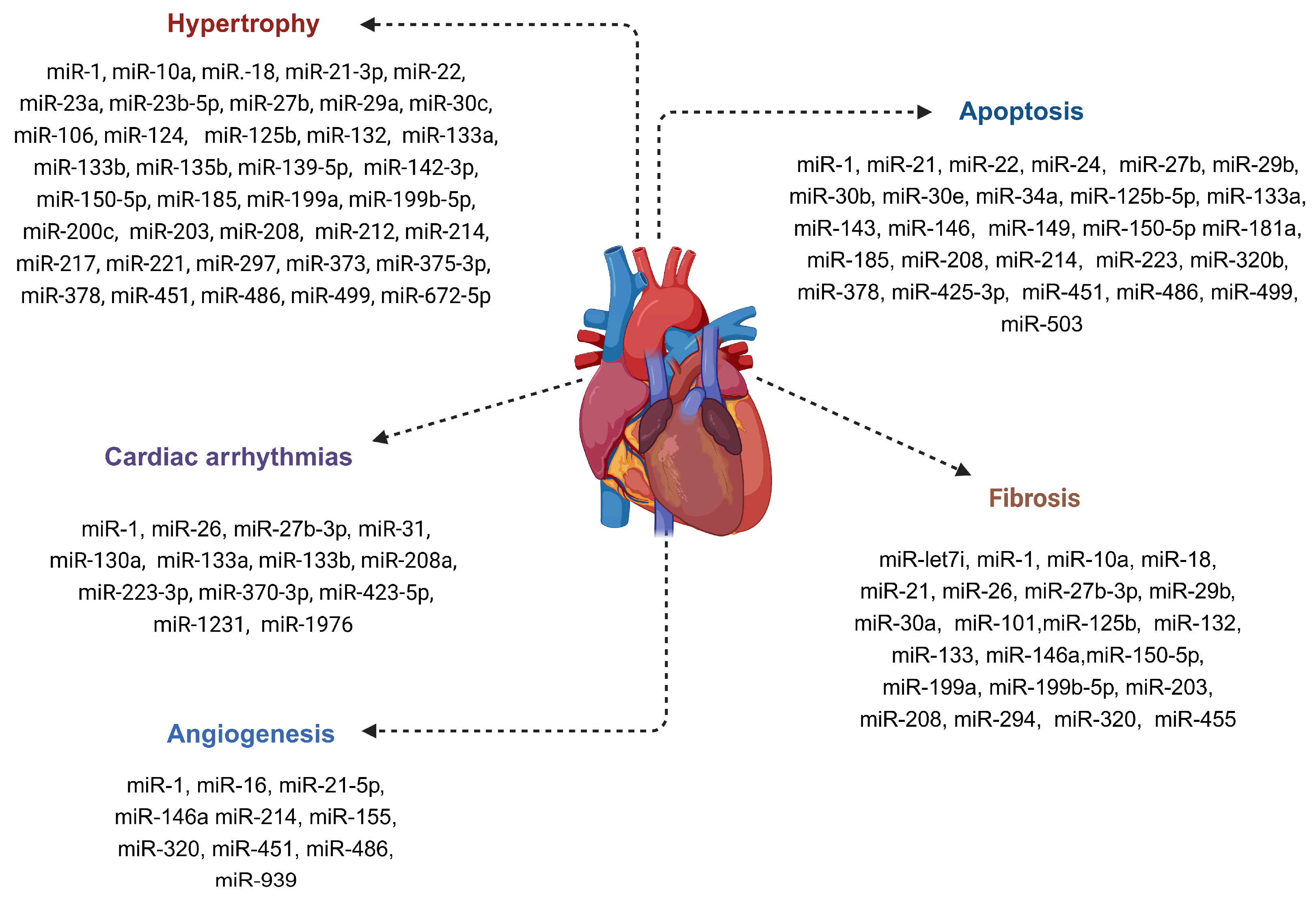

4. MicroRNAs

5. Myocardial miRNA Signature in LVAD-Supported HF Patients

6. Biomarker Potential of Circulating miRNAs Associated with LVAD-Induced Mechanical Unloading

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 8-OHdG | 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine |

| ACC/AHA | American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association; |

| ACE | angiotensin-converting enzyme |

| ADM | adrenomedullin |

| ADMA | asymmetric dimethyl arginine |

| ARBs | angiotensin receptor blockers |

| ARN | angiotensin receptor/ neprilysin inhibitors |

| BDNF | brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| BNP | brain natriuretic peptide |

| BTR | bridge to recovery |

| BTT | bridge to transplantation |

| CA125 | cancer antigen 125 |

| cf-LVAD | continuous flow LVAD devices |

| CHD | congenital heart disease |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CRT | cardiac resynchronization therapy |

| DCM | dilated cardiomyopathy |

| DT | destination therapy |

| ET-1 | endothelin 1 |

| FGF-21 | fibroblast growth factor 21 |

| GAL-3 | galectin-3 |

| GDF-15 | growth differentiation factor 15 |

| GSTP1 | glutathione transferase P1 |

| HCM | hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| HF | heart failure |

| H-FABP | heart-type fatty acid-binding protein |

| HFmrEF | heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction |

| HFpEF | heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| HFrEF | heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| hs-cTnT/CTnI | high-sensitivity cardiac troponins cTnT and cTnI |

| HTx | heart transplantation |

| HTx-ctrl | heart transplant control |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 |

| ICM | ischemic cardiomyopathy |

| IL-1 | interleukin |

| IL-1 RA | interleukin-1 receptor antagonist |

| IL-15 | interleukin 15 |

| IL-18 | interleukin 18 |

| IL-33 | interleukin 33 |

| IL-6 | interleukin 6 |

| IL-8 | interleukin 8 |

| INTERMACS | interagency registry for mechanically assisted circulatory support |

| KIM-1 | kidney injury molecule-1 |

| lncRNA | long non-coding RNA |

| LV | left ventricle |

| LVAD | left ventricular assist device |

| LVEF | left ventricular ejection fraction |

| LVNC | LV non-compaction |

| MCS | mechanical circulatory support |

| MMP-1 | matrix metalloproteinase 1 |

| MMP-2 | matrix metalloproteinase 2 |

| MMP-9 | matrix metalloproteinase 9 |

| MPO | myeloperoxidase |

| MRA | mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist |

| MR-proADM | mid-regional pro-adrenomedullin |

| NF | non-failing control |

| NGAL | neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin |

| NGS | next generation sequencing |

| NICM | nonischemic cardiomyopathy |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal brain natriuretic pro-peptide |

| NTproCNP | N-Terminal pro C-Type Natriuretic Peptide |

| NYHA class | New York Heart Association functional classification for heart failure |

| Ox LDL | oxidized low-density lipoprotein |

| pf-LVAD | pulsatile flow LVAD devices |

| PICP | procollagen type I carboxyterminal peptide |

| PIIINP | pro-collagen type III amino terminal peptide |

| qPCR | quantitative real-time PCR |

| RMC | restrictive cardiomyopathy |

| RV | right ventricle |

| SE | standard error |

| SGLT2 | sodium-glucose linked cotransporter 2 |

| sST2 | soluble suppression of tumorigenesis-2 |

| TIMP-1 | tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase 1 |

| TNF-α | transforming growth factor alpha |

| VCAM-1 | vascular cell adhesion protein 1 |

| vWF | Von Willebrand factor |

| α1-AT | alpha-1 antitrypsin |

References

- Bozkurt, B., Coats, A. J. S., Tsutsui, H., Abdelhamid, C. M., Adamopoulos, S., Albert, N., Anker, S. D., Atherton, J., Böhm, M., Butler, J., Drazner, M. H., Michael Felker, G., Filippatos, G., Fiuzat, M., Fonarow, G. C., Gomez-Mesa, J. E., Heidenreich, P., Imamura, T., Jankowska, E. A., Januzzi, J., Khazanie, P., Kinugawa, K., Lam, C. S. P., Matsue, Y., Metra, M., Ohtani, T., Francesco Piepoli, M., Ponikowski, P., Rosano, G. M. C., Sakata, Y., Seferović, P., Starling, R. C., Teerlink, J. R., Vardeny, O., Yamamoto, K., Yancy, C., Zhang, J. & Zieroth, S. (2021). Universal definition and classification of heart failure: a report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition of Heart Failure: Endorsed by the Canadian Heart Failure Society, Heart Failure Association of India, Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand, and Chinese Heart Failure Association. Eur J Heart Fail. 23, 352-380. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. S., Shahid, I., Bennis, A., Rakisheva, A., Metra, M. & Butler, J. (2024). Global epidemiology of heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. [CrossRef]

- Savarese, G., Becher, P. M., Lund, L. H., Seferovic, P., Rosano, G. M. C. & Coats, A. J. S. (2023). Global burden of heart failure: a comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc Res. 118, 3272-3287. [CrossRef]

- Shahim, B., Kapelios, C. J., Savarese, G. & Lund, L. H. (2023). Global Public Health Burden of Heart Failure: An Updated Review. Card Fail Rev. 9, e11. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S., MacIntyre, K., Hole, D. J., Capewell, S. & McMurray, J. J. (2001). More ’malignant’ than cancer? Five-year survival following a first admission for heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 3, 315-322. [CrossRef]

- González, A., Richards, A. M., de Boer, R. A., Thum, T., Arfsten, H., Hülsmann, M., Falcao-Pires, I., Díez, J., Foo, R. S. Y., Chan, M. Y., Aimo, A., Anene-Nzelu, C. G., Abdelhamid, M., Adamopoulos, S., Anker, S. D., Belenkov, Y., Ben Gal, T., Cohen-Solal, A., Böhm, M., Chioncel, O., Delgado, V., Emdin, M., Jankowska, E. A., Gustafsson, F., Hill, L., Jaarsma, T., Januzzi, J. L., Jhund, P. S., Lopatin, Y., Lund, L. H., Metra, M., Milicic, D., Moura, B., Mueller, C., Mullens, W., Núñez, J., Piepoli, M. F., Rakisheva, A., Ristić, A. D., Rossignol, P., Savarese, G., Tocchetti, C. G., Van Linthout, S., Volterrani, M., Seferovic, P., Rosano, G., Coats, A. J. S. & Bayés-Genís, A. (2022). Cardiac remodelling - Part 1: From cells and tissues to circulating biomarkers. A review from the Study Group on Biomarkers of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 24, 927-943. [CrossRef]

- Aimo, A., Vergaro, G., González, A., Barison, A., Lupón, J., Delgado, V., Richards, A. M., de Boer, R. A., Thum, T., Arfsten, H., Hülsmann, M., Falcao-Pires, I., Díez, J., Foo, R. S. Y., Chan, M. Y. Y., Anene-Nzelu, C. G., Abdelhamid, M., Adamopoulos, S., Anker, S. D., Belenkov, Y., Ben Gal, T., Cohen-Solal, A., Böhm, M., Chioncel, O., Jankowska, E. A., Gustafsson, F., Hill, L., Jaarsma, T., Januzzi, J. L., Jhund, P., Lopatin, Y., Lund, L. H., Metra, M., Milicic, D., Moura, B., Mueller, C., Mullens, W., Núñez, J., Piepoli, M. F., Rakisheva, A., Ristić, A. D., Rossignol, P., Savarese, G., Tocchetti, C. G., van Linthout, S., Volterrani, M., Seferovic, P., Rosano, G., Coats, A. J. S., Emdin, M. & Bayes-Genis, A. (2022). Cardiac remodelling - Part 2: Clinical, imaging and laboratory findings. A review from the Study Group on Biomarkers of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 24, 944-958. [CrossRef]

- Cohn, J. N., Ferrari, R. & Sharpe, N. (2000). Cardiac remodeling--concepts and clinical implications: a consensus paper from an international forum on cardiac remodeling. Behalf of an International Forum on Cardiac Remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 35, 569-582. [CrossRef]

- Zeglinski, M. R., Moghadam, A. R., Ande, S. R., Sheikholeslami, K., Mokarram, P., Sepehri, Z., Rokni, H., Mohtaram, N. K., Poorebrahim, M., Masoom, A., Toback, M., Sareen, N., Saravanan, S., Jassal, D. S., Hashemi, M., Marzban, H., Schaafsma, D., Singal, P., Wigle, J. T., Czubryt, M. P., Akbari, M., Dixon, I. M. C., Ghavami, S., Gordon, J. W. & Dhingra, S. (2018). Myocardial Cell Signaling During the Transition to Heart Failure: Cellular Signaling and Therapeutic Approaches. Compr Physiol. 9, 75-125. [CrossRef]

- González, A., Schelbert, E. B., Díez, J. & Butler, J. (2018). Myocardial Interstitial Fibrosis in Heart Failure: Biological and Translational Perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol. 71, 1696-1706. [CrossRef]

- Triposkiadis, F., Giamouzis, G., Boudoulas, K. D., Karagiannis, G., Skoularigis, J., Boudoulas, H. & Parissis, J. (2018). Left ventricular geometry as a major determinant of left ventricular ejection fraction: physiological considerations and clinical implications. Eur J Heart Fail. 20, 436-444. [CrossRef]

- Husti, Z., Varró, A. & Baczkó, I. (2021). Arrhythmogenic Remodeling in the Failing Heart. Cells. 10. [CrossRef]

- Frangogiannis, N. G. (2019). The Extracellular Matrix in Ischemic and Nonischemic Heart Failure. Circ Res. 125, 117-146. [CrossRef]

- Bristow, M. R., Kao, D. P., Breathett, K. K., Altman, N. L., Gorcsan, J., 3rd, Gill, E. A., Lowes, B. D., Gilbert, E. M., Quaife, R. A. & Mann, D. L. (2017). Structural and Functional Phenotyping of the Failing Heart: Is the Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction Obsolete? JACC Heart Fail. 5, 772-781. [CrossRef]

- Vancheri, F., Longo, G. & Henein, M. Y. (2024). Left ventricular ejection fraction: clinical, pathophysiological, and technical limitations. Front Cardiovasc Med. 11, 1340708. [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, P. A., Bozkurt, B., Aguilar, D., Allen, L. A., Byun, J. J., Colvin, M. M., Deswal, A., Drazner, M. H., Dunlay, S. M., Evers, L. R., Fang, J. C., Fedson, S. E., Fonarow, G. C., Hayek, S. S., Hernandez, A. F., Khazanie, P., Kittleson, M. M., Lee, C. S., Link, M. S., Milano, C. A., Nnacheta, L. C., Sandhu, A. T., Stevenson, L. W., Vardeny, O., Vest, A. R. & Yancy, C. W. (2022). 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 145, e895-e1032. [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T. A., Metra, M., Adamo, M., Gardner, R. S., Baumbach, A., Böhm, M., Burri, H., Butler, J., Čelutkienė, J., Chioncel, O., Cleland, J. G. F., Coats, A. J. S., Crespo-Leiro, M. G., Farmakis, D., Gilard, M., Heymans, S., Hoes, A. W., Jaarsma, T., Jankowska, E. A., Lainscak, M., Lam, C. S. P., Lyon, A. R., McMurray, J. J. V., Mebazaa, A., Mindham, R., Muneretto, C., Francesco Piepoli, M., Price, S., Rosano, G. M. C., Ruschitzka, F. & Kathrine Skibelund, A. (2021). 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 42, 3599-3726. [CrossRef]

- Falcão-Pires, I., Ferreira, A. F., Trindade, F., Bertrand, L., Ciccarelli, M., Visco, V., Dawson, D., Hamdani, N., Van Laake, L. W., Lezoualc’h, F., Linke, W. A., Lunde, I. G., Rainer, P. P., Abdellatif, M., Van der Velden, J., Cosentino, N., Paldino, A., Pompilio, G., Zacchigna, S., Heymans, S., Thum, T. & Tocchetti, C. G. (2024). Mechanisms of myocardial reverse remodelling and its clinical significance: A scientific statement of the ESC Working Group on Myocardial Function. Eur J Heart Fail. [CrossRef]

- Koitabashi, N. & Kass, D. A. (2011). Reverse remodeling in heart failure--mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cardiol. 9, 147-157. [CrossRef]

- Kim, G. H., Uriel, N. & Burkhoff, D. (2018). Reverse remodelling and myocardial recovery in heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 15, 83-96. [CrossRef]

- Boulet, J. & Mehra, M. R. (2021). Left Ventricular Reverse Remodeling in Heart Failure: Remission to Recovery. Structural Heart. 5, 466-481. [CrossRef]

- Chudý, M. & Goncalvesová, E. (2022). Prediction of Left Ventricular Reverse Remodelling: A Mini Review on Clinical Aspects. Cardiology. 147, 521-528. [CrossRef]

- Hellawell, J. L. & Margulies, K. B. (2012). Myocardial reverse remodeling. Cardiovasc Ther. 30, 172-181. [CrossRef]

- Reis Filho, J. R., Cardoso, J. N., Cardoso, C. M. & Pereira-Barretto, A. C. (2015). Reverse Cardiac Remodeling: A Marker of Better Prognosis in Heart Failure. Arq Bras Cardiol. 104, 502-506. [CrossRef]

- Ojo, A., Tariq, S., Harikrishnan, P., Iwai, S. & Jacobson, J. T. (2017). Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy for Heart Failure. Interv Cardiol Clin. 6, 417-426. [CrossRef]

- Burkhoff, D., Topkara, V. K., Sayer, G. & Uriel, N. (2021). Reverse Remodeling With Left Ventricular Assist Devices. Circ Res. 128, 1594-1612. [CrossRef]

- Hamad, E. A., Byku, M., Larson, S. B. & Billia, F. (2023). LVAD therapy as a catalyst to heart failure remission and myocardial recovery. Clin Cardiol. 46, 1154-1162. [CrossRef]

- Pan, S., Aksut, B., Wever-Pinzon, O. E., Rao, S. D., Levin, A. P., Garan, A. R., Fried, J. A., Takeda, K., Hiroo, T., Yuzefpolskaya, M., Uriel, N., Jorde, U. P., Mancini, D. M., Naka, Y., Colombo, P. C. & Topkara, V. K. (2015). Incidence and predictors of myocardial recovery on long-term left ventricular assist device support: Results from the United Network for Organ Sharing database. J Heart Lung Transplant. 34, 1624-1629. [CrossRef]

- Ponzoni, M., Coles, J. G. & Maynes, J. T. (2023). Rodent Models of Dilated Cardiomyopathy and Heart Failure for Translational Investigations and Therapeutic Discovery. Int J Mol Sci. 24. [CrossRef]

- Galeone, A., Buccoliero, C., Barile, B., Nicchia, G. P., Onorati, F., Luciani, G. B. & Brunetti, G. (2023). Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms Activated by a Left Ventricular Assist Device. Int J Mol Sci. 25. [CrossRef]

- Drakos, S. G., Badolia, R., Makaju, A., Kyriakopoulos, C. P., Wever-Pinzon, O., Tracy, C. M., Bakhtina, A., Bia, R., Parnell, T., Taleb, I., Ramadurai, D. K. A., Navankasattusas, S., Dranow, E., Hanff, T. C., Tseliou, E., Shankar, T. S., Visker, J., Hamouche, R., Stauder, E. L., Caine, W. T., Alharethi, R., Selzman, C. H. & Franklin, S. (2023). Distinct Transcriptomic and Proteomic Profile Specifies Patients Who Have Heart Failure With Potential of Myocardial Recovery on Mechanical Unloading and Circulatory Support. Circulation. 147, 409-424. [CrossRef]

- Margulies, K. B., Matiwala, S., Cornejo, C., Olsen, H., Craven, W. A. & Bednarik, D. (2005). Mixed messages: transcription patterns in failing and recovering human myocardium. Circ Res. 96, 592-599. [CrossRef]

- Topkara, V. K., Chambers, K. T., Yang, K. C., Tzeng, H. P., Evans, S., Weinheimer, C., Kovacs, A., Robbins, J., Barger, P. & Mann, D. L. (2016). Functional significance of the discordance between transcriptional profile and left ventricular structure/function during reverse remodeling. JCI Insight. 1, e86038. [CrossRef]

- Yan, C. L. & Grazette, L. (2023). A review of biomarker and imaging monitoring to predict heart failure recovery. Front Cardiovasc Med. 10, 1150336. [CrossRef]

- Holzhauser, L., Kim, G., Sayer, G. & Uriel, N. (2018). The Effect of Left Ventricular Assist Device Therapy on Cardiac Biomarkers: Implications for the Identification of Myocardial Recovery. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 15, 250-259. [CrossRef]

- Motiwala, S. R. & Gaggin, H. K. (2016). Biomarkers to Predict Reverse Remodeling and Myocardial Recovery in Heart Failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 13, 207-218. [CrossRef]

- Castiglione, V., Aimo, A., Vergaro, G., Saccaro, L., Passino, C. & Emdin, M. (2022). Biomarkers for the diagnosis and management of heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 27, 625-643. [CrossRef]

- Jaltotage, B., Dwivedi, G., Ooi, D. E. L. & Mahadavan, G. (2021). The Utility of Circulating and Imaging Biomarkers Alone and in Combination in Heart Failure. Curr Cardiol Rev. 17, e160721193557. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E. L., Baker, A. H., Brittan, M., McCracken, I., Condorelli, G., Emanueli, C., Srivastava, P. K., Gaetano, C., Thum, T., Vanhaverbeke, M., Angione, C., Heymans, S., Devaux, Y., Pedrazzini, T. & Martelli, F. (2022). Dissecting the transcriptome in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res. 118, 1004-1019. [CrossRef]

- Dangwal, S., Schimmel, K., Foinquinos, A., Xiao, K. & Thum, T. (2017). Noncoding RNAs in Heart Failure. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 243, 423-445. [CrossRef]

- Singh, D. D., Kim, Y., Choi, S. A., Han, I. & Yadav, D. K. (2023). Clinical Significance of MicroRNAs, Long Non-Coding RNAs, and CircRNAs in Cardiovascular Diseases. Cells. 12. [CrossRef]

- Carninci, P., Kasukawa, T., Katayama, S., Gough, J., Frith, M. C., Maeda, N., Oyama, R., Ravasi, T., Lenhard, B., Wells, C., Kodzius, R., Shimokawa, K., Bajic, V. B., Brenner, S. E., Batalov, S., Forrest, A. R., Zavolan, M., Davis, M. J., Wilming, L. G., Aidinis, V., Allen, J. E., Ambesi-Impiombato, A., Apweiler, R., Aturaliya, R. N., Bailey, T. L., Bansal, M., Baxter, L., Beisel, K. W., Bersano, T., Bono, H., Chalk, A. M., Chiu, K. P., Choudhary, V., Christoffels, A., Clutterbuck, D. R., Crowe, M. L., Dalla, E., Dalrymple, B. P., de Bono, B., Della Gatta, G., di Bernardo, D., Down, T., Engstrom, P., Fagiolini, M., Faulkner, G., Fletcher, C. F., Fukushima, T., Furuno, M., Futaki, S., Gariboldi, M., Georgii-Hemming, P., Gingeras, T. R., Gojobori, T., Green, R. E., Gustincich, S., Harbers, M., Hayashi, Y., Hensch, T. K., Hirokawa, N., Hill, D., Huminiecki, L., Iacono, M., Ikeo, K., Iwama, A., Ishikawa, T., Jakt, M., Kanapin, A., Katoh, M., Kawasawa, Y., Kelso, J., Kitamura, H., Kitano, H., Kollias, G., Krishnan, S. P., Kruger, A., Kummerfeld, S. K., Kurochkin, I. V., Lareau, L. F., Lazarevic, D., Lipovich, L., Liu, J., Liuni, S., McWilliam, S., Madan Babu, M., Madera, M., Marchionni, L., Matsuda, H., Matsuzawa, S., Miki, H., Mignone, F., Miyake, S., Morris, K., Mottagui-Tabar, S., Mulder, N., Nakano, N., Nakauchi, H., Ng, P., Nilsson, R., Nishiguchi, S., Nishikawa, S., Nori, F., Ohara, O., Okazaki, Y., Orlando, V., Pang, K. C., Pavan, W. J., Pavesi, G., Pesole, G., Petrovsky, N., Piazza, S., Reed, J., Reid, J. F., Ring, B. Z., Ringwald, M., Rost, B., Ruan, Y., Salzberg, S. L., Sandelin, A., Schneider, C., Schönbach, C., Sekiguchi, K., Semple, C. A., Seno, S., Sessa, L., Sheng, Y., Shibata, Y., Shimada, H., Shimada, K., Silva, D., Sinclair, B., Sperling, S., Stupka, E., Sugiura, K., Sultana, R., Takenaka, Y., Taki, K., Tammoja, K., Tan, S. L., Tang, S., Taylor, M. S., Tegner, J., Teichmann, S. A., Ueda, H. R., van Nimwegen, E., Verardo, R., Wei, C. L., Yagi, K., Yamanishi, H., Zabarovsky, E., Zhu, S., Zimmer, A., Hide, W., Bult, C., Grimmond, S. M., Teasdale, R. D., Liu, E. T., Brusic, V., Quackenbush, J., Wahlestedt, C., Mattick, J. S., Hume, D. A., Kai, C., Sasaki, D., Tomaru, Y., Fukuda, S., Kanamori-Katayama, M., Suzuki, M., Aoki, J., Arakawa, T., Iida, J., Imamura, K., Itoh, M., Kato, T., Kawaji, H., Kawagashira, N., Kawashima, T., Kojima, M., Kondo, S., Konno, H., Nakano, K., Ninomiya, N., Nishio, T., Okada, M., Plessy, C., Shibata, K., Shiraki, T., Suzuki, S., Tagami, M., Waki, K., Watahiki, A., Okamura-Oho, Y., Suzuki, H., Kawai, J. & Hayashizaki, Y. (2005). The transcriptional landscape of the mammalian genome. Science. 309, 1559-1563. [CrossRef]

- Djebali, S., Davis, C. A., Merkel, A., Dobin, A., Lassmann, T., Mortazavi, A., Tanzer, A., Lagarde, J., Lin, W., Schlesinger, F., Xue, C., Marinov, G. K., Khatun, J., Williams, B. A., Zaleski, C., Rozowsky, J., Röder, M., Kokocinski, F., Abdelhamid, R. F., Alioto, T., Antoshechkin, I., Baer, M. T., Bar, N. S., Batut, P., Bell, K., Bell, I., Chakrabortty, S., Chen, X., Chrast, J., Curado, J., Derrien, T., Drenkow, J., Dumais, E., Dumais, J., Duttagupta, R., Falconnet, E., Fastuca, M., Fejes-Toth, K., Ferreira, P., Foissac, S., Fullwood, M. J., Gao, H., Gonzalez, D., Gordon, A., Gunawardena, H., Howald, C., Jha, S., Johnson, R., Kapranov, P., King, B., Kingswood, C., Luo, O. J., Park, E., Persaud, K., Preall, J. B., Ribeca, P., Risk, B., Robyr, D., Sammeth, M., Schaffer, L., See, L. H., Shahab, A., Skancke, J., Suzuki, A. M., Takahashi, H., Tilgner, H., Trout, D., Walters, N., Wang, H., Wrobel, J., Yu, Y., Ruan, X., Hayashizaki, Y., Harrow, J., Gerstein, M., Hubbard, T., Reymond, A., Antonarakis, S. E., Hannon, G., Giddings, M. C., Ruan, Y., Wold, B., Carninci, P., Guigó, R. & Gingeras, T. R. (2012). Landscape of transcription in human cells. Nature. 489, 101-108. [CrossRef]

- Stelzer, G., Rosen, N., Plaschkes, I., Zimmerman, S., Twik, M., Fishilevich, S., Stein, T. I., Nudel, R., Lieder, I., Mazor, Y., Kaplan, S., Dahary, D., Warshawsky, D., Guan-Golan, Y., Kohn, A., Rappaport, N., Safran, M. & Lancet, D. (2016). The GeneCards Suite: From Gene Data Mining to Disease Genome Sequence Analyses. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 54, 1.30.31-31.30.33. [CrossRef]

- Yates, A. D., Achuthan, P., Akanni, W., Allen, J., Allen, J., Alvarez-Jarreta, J., Amode, M. R., Armean, I. M., Azov, A. G., Bennett, R., Bhai, J., Billis, K., Boddu, S., Marugán, J. C., Cummins, C., Davidson, C., Dodiya, K., Fatima, R., Gall, A., Giron, C. G., Gil, L., Grego, T., Haggerty, L., Haskell, E., Hourlier, T., Izuogu, O. G., Janacek, S. H., Juettemann, T., Kay, M., Lavidas, I., Le, T., Lemos, D., Martinez, J. G., Maurel, T., McDowall, M., McMahon, A., Mohanan, S., Moore, B., Nuhn, M., Oheh, D. N., Parker, A., Parton, A., Patricio, M., Sakthivel, M. P., Abdul Salam, A. I., Schmitt, B. M., Schuilenburg, H., Sheppard, D., Sycheva, M., Szuba, M., Taylor, K., Thormann, A., Threadgold, G., Vullo, A., Walts, B., Winterbottom, A., Zadissa, A., Chakiachvili, M., Flint, B., Frankish, A., Hunt, S. E., G, I. I., Kostadima, M., Langridge, N., Loveland, J. E., Martin, F. J., Morales, J., Mudge, J. M., Muffato, M., Perry, E., Ruffier, M., Trevanion, S. J., Cunningham, F., Howe, K. L., Zerbino, D. R. & Flicek, P. (2020). Ensembl 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D682-d688. [CrossRef]

- Braschi, B., Denny, P., Gray, K., Jones, T., Seal, R., Tweedie, S., Yates, B. & Bruford, E. (2019). Genenames.org: the HGNC and VGNC resources in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D786-d792. [CrossRef]

- (2019). RNAcentral: a hub of information for non-coding RNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D221-d229. [CrossRef]

- Barshir, R., Fishilevich, S., Iny-Stein, T., Zelig, O., Mazor, Y., Guan-Golan, Y., Safran, M. & Lancet, D. (2021). GeneCaRNA: A Comprehensive Gene-centric Database of Human Non-coding RNAs in the GeneCards Suite. J Mol Biol. 433, 166913. [CrossRef]

- Brown, G. R., Hem, V., Katz, K. S., Ovetsky, M., Wallin, C., Ermolaeva, O., Tolstoy, I., Tatusova, T., Pruitt, K. D., Maglott, D. R. & Murphy, T. D. (2015). Gene: a gene-centered information resource at NCBI. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D36-42. [CrossRef]

- Morris, K. V. & Mattick, J. S. (2014). The rise of regulatory RNA. Nat Rev Genet. 15, 423-437. [CrossRef]

- Hombach, S. & Kretz, M. (2016). Non-coding RNAs: Classification, Biology and Functioning. Adv Exp Med Biol. 937, 3-17. [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, K., Bayraktar, R., Ferracin, M. & Calin, G. A. (2024). Non-coding RNAs in disease: from mechanisms to therapeutics. Nat Rev Genet. 25, 211-232. [CrossRef]

- Ninomiya, K., Yamazaki, T. & Hirose, T. (2023). Satellite RNAs: emerging players in subnuclear architecture and gene regulation. Embo j. 42, e114331. [CrossRef]

- St Laurent, G., Wahlestedt, C. & Kapranov, P. (2015). The Landscape of long noncoding RNA classification. Trends Genet. 31, 239-251. [CrossRef]

- Shang, R., Lee, S., Senavirathne, G. & Lai, E. C. (2023). microRNAs in action: biogenesis, function and regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 24, 816-833. [CrossRef]

- Statello, L., Guo, C. J., Chen, L. L. & Huarte, M. (2021). Gene regulation by long non-coding RNAs and its biological functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 22, 96-118. [CrossRef]

- Loganathan, T. & Doss, C. G. (2023). Non-coding RNAs in human health and disease: potential function as biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Funct Integr Genomics. 23, 33. [CrossRef]

- Wu, R., Su, Y., Wu, H., Dai, Y., Zhao, M. & Lu, Q. (2016). Characters, functions and clinical perspectives of long non-coding RNAs. Mol Genet Genomics. 291, 1013-1033. [CrossRef]

- Poller, W., Dimmeler, S., Heymans, S., Zeller, T., Haas, J., Karakas, M., Leistner, D. M., Jakob, P., Nakagawa, S., Blankenberg, S., Engelhardt, S., Thum, T., Weber, C., Meder, B., Hajjar, R. & Landmesser, U. (2018). Non-coding RNAs in cardiovascular diseases: diagnostic and therapeutic perspectives. Eur Heart J. 39, 2704-2716. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Padilla, C., Lozano-Velasco, E., Garcia-Lopez, V., Aranega, A., Franco, D., Garcia-Martinez, V. & Lopez-Sanchez, C. (2022). Comparative Analysis of Non-Coding RNA Transcriptomics in Heart Failure. Biomedicines. 10. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A., Griffiths-Jones, S., Ashurst, J. L. & Bradley, A. (2004). Identification of mammalian microRNA host genes and transcription units. Genome Res. 14, 1902-1910. [CrossRef]

- Godnic, I., Zorc, M., Jevsinek Skok, D., Calin, G. A., Horvat, S., Dovc, P., Kovac, M. & Kunej, T. (2013). Genome-wide and species-wide in silico screening for intragenic MicroRNAs in human, mouse and chicken. PLoS One. 8, e65165. [CrossRef]

- Ramchandran, R. & Chaluvally-Raghavan, P. (2017). miRNA-Mediated RNA Activation in Mammalian Cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 983, 81-89. [CrossRef]

- Stavast, C. J. & Erkeland, S. J. (2019). The Non-Canonical Aspects of MicroRNAs: Many Roads to Gene Regulation. Cells. 8. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, R. C., Farh, K. K., Burge, C. B. & Bartel, D. P. (2009). Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 19, 92-105. [CrossRef]

- Gebert, L. F. R. & MacRae, I. J. (2019). Regulation of microRNA function in animals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 20, 21-37. [CrossRef]

- Londin, E., Loher, P., Telonis, A. G., Quann, K., Clark, P., Jing, Y., Hatzimichael, E., Kirino, Y., Honda, S., Lally, M., Ramratnam, B., Comstock, C. E., Knudsen, K. E., Gomella, L., Spaeth, G. L., Hark, L., Katz, L. J., Witkiewicz, A., Rostami, A., Jimenez, S. A., Hollingsworth, M. A., Yeh, J. J., Shaw, C. A., McKenzie, S. E., Bray, P., Nelson, P. T., Zupo, S., Van Roosbroeck, K., Keating, M. J., Calin, G. A., Yeo, C., Jimbo, M., Cozzitorto, J., Brody, J. R., Delgrosso, K., Mattick, J. S., Fortina, P. & Rigoutsos, I. (2015). Analysis of 13 cell types reveals evidence for the expression of numerous novel primate- and tissue-specific microRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 112, E1106-1115. [CrossRef]

- Tomasello, L., Distefano, R., Nigita, G. & Croce, C. M. (2021). The MicroRNA Family Gets Wider: The IsomiRs Classification and Role. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9, 668648. [CrossRef]

- Zealy, R. W., Wrenn, S. P., Davila, S., Min, K. W. & Yoon, J. H. (2017). microRNA-binding proteins: specificity and function. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 8. [CrossRef]

- Sood, P., Krek, A., Zavolan, M., Macino, G. & Rajewsky, N. (2006). Cell-type-specific signatures of microRNAs on target mRNA expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 103, 2746-2751. [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, N., Leidinger, P., Becker, K., Backes, C., Fehlmann, T., Pallasch, C., Rheinheimer, S., Meder, B., Stähler, C., Meese, E. & Keller, A. (2016). Distribution of miRNA expression across human tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 3865-3877. [CrossRef]

- Kozomara, A., Birgaoanu, M. & Griffiths-Jones, S. (2019). miRBase: from microRNA sequences to function. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D155-d162. [CrossRef]

- Laggerbauer, B. & Engelhardt, S. (2022). MicroRNAs as therapeutic targets in cardiovascular disease. J Clin Invest. 132. [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, P., Marzano, F., Salvatore, M., Basile, C., Buonocore, D., Parlati, A. L. M., Nardi, E., Asile, G., Abbate, V., Colella, A., Chirico, A., Marciano, C., Paolillo, S. & Perrone-Filardi, P. (2023). MicroRNAs: diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic role in heart failure-a review. ESC Heart Fail. 10, 753-761. [CrossRef]

- Shen, N. N., Wang, J. L. & Fu, Y. P. (2022). The microRNA Expression Profiling in Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 9, 856358. [CrossRef]

- Gholaminejad, A., Zare, N., Dana, N., Shafie, D., Mani, A. & Javanmard, S. H. (2021). A meta-analysis of microRNA expression profiling studies in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 26, 997-1021. [CrossRef]

- Parvan, R., Hosseinpour, M., Moradi, Y., Devaux, Y., Cataliotti, A. & da Silva, G. J. J. (2022). Diagnostic performance of microRNAs in the detection of heart failure with reduced or preserved ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 24, 2212-2225. [CrossRef]

- Vilella-Figuerola, A., Gallinat, A., Escate, R., Mirabet, S., Padró, T. & Badimon, L. (2022). Systems Biology in Chronic Heart Failure-Identification of Potential miRNA Regulators. Int J Mol Sci. 23. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, R., Adão, R., Leite-Moreira, A. F., Mâncio, J. & Brás-Silva, C. (2022). Candidate microRNAs as prognostic biomarkers in heart failure: A systematic review. Rev Port Cardiol. 41, 865-885. [CrossRef]

- Schipper, M. E., van Kuik, J., de Jonge, N., Dullens, H. F. & de Weger, R. A. (2008). Changes in regulatory microRNA expression in myocardium of heart failure patients on left ventricular assist device support. J Heart Lung Transplant. 27, 1282-1285. [CrossRef]

- Ramani, R., Vela, D., Segura, A., McNamara, D., Lemster, B., Samarendra, V., Kormos, R., Toyoda, Y., Bermudez, C., Frazier, O. H., Moravec, C. S., Gorcsan, J., 3rd, Taegtmeyer, H. & McTiernan, C. F. (2011). A micro-ribonucleic acid signature associated with recovery from assist device support in 2 groups of patients with severe heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 58, 2270-2278. [CrossRef]

- Lok, S. I., van Mil, A., Bovenschen, N., van der Weide, P., van Kuik, J., van Wichen, D., Peeters, T., Siera, E., Winkens, B., Sluijter, J. P., Doevendans, P. A., da Costa Martins, P. A., de Jonge, N. & de Weger, R. A. (2013). Post-transcriptional regulation of α-1-antichymotrypsin by microRNA-137 in chronic heart failure and mechanical support. Circ Heart Fail. 6, 853-861. [CrossRef]

- Barsanti, C., Trivella, M. G., D’Aurizio, R., El Baroudi, M., Baumgart, M., Groth, M., Caruso, R., Verde, A., Botta, L., Cozzi, L. & Pitto, L. (2015). Differential regulation of microRNAs in end-stage failing hearts is associated with left ventricular assist device unloading. Biomed Res Int. 2015, 592512. [CrossRef]

- Lok, S. I., de Jonge, N., van Kuik, J., van Geffen, A. J., Huibers, M. M., van der Weide, P., Siera, E., Winkens, B., Doevendans, P. A., de Weger, R. A. & da Costa Martins, P. A. (2015). MicroRNA Expression in Myocardial Tissue and Plasma of Patients with End-Stage Heart Failure during LVAD Support: Comparison of Continuous and Pulsatile Devices. PLoS One. 10, e0136404. [CrossRef]

- Morley-Smith, A. C., Mills, A., Jacobs, S., Meyns, B., Rega, F., Simon, A. R., Pepper, J. R., Lyon, A. R. & Thum, T. (2014). Circulating microRNAs for predicting and monitoring response to mechanical circulatory support from a left ventricular assist device. Eur J Heart Fail. 16, 871-879. [CrossRef]

- Ragusa, R., Di Molfetta, A., Del Turco, S., Cabiati, M., Del Ry, S., Basta, G., Mercatanti, A., Pitto, L., Amodeo, A., Trivella, M. G., Rizzo, M. & Caselli, C. (2021). Epigenetic Regulation of Cardiac Troponin Genes in Pediatric Patients with Heart Failure Supported by Ventricular Assist Device. Biomedicines. 9. [CrossRef]

- Ragusa, R., Di Molfetta, A., Mercatanti, A., Pitto, L., Amodeo, A., Trivella, M. G., Rizzo, M. & Caselli, C. (2024). Changes in adiponectin system after ventricular assist device in pediatric heart failure. JHLT Open. 3, None. [CrossRef]

- Mann, D. L. & Burkhoff, D. (2011). Myocardial expression levels of micro-ribonucleic acids in patients with left ventricular assist devices signature of myocardial recovery, signature of reverse remodeling, or signature with no name? J Am Coll Cardiol. 58, 2279-2281. [CrossRef]

- Matkovich, S. J., Van Booven, D. J., Youker, K. A., Torre-Amione, G., Diwan, A., Eschenbacher, W. H., Dorn, L. E., Watson, M. A., Margulies, K. B. & Dorn, G. W., 2nd (2009). Reciprocal regulation of myocardial microRNAs and messenger RNA in human cardiomyopathy and reversal of the microRNA signature by biomechanical support. Circulation. 119, 1263-1271. [CrossRef]

- Akat, K. M., Moore-McGriff, D., Morozov, P., Brown, M., Gogakos, T., Correa Da Rosa, J., Mihailovic, A., Sauer, M., Ji, R., Ramarathnam, A., Totary-Jain, H., Williams, Z., Tuschl, T. & Schulze, P. C. (2014). Comparative RNA-sequencing analysis of myocardial and circulating small RNAs in human heart failure and their utility as biomarkers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 111, 11151-11156. [CrossRef]

- Parikh, M., Shah, S., Basu, R., Famulski, K. S., Kim, D., Mullen, J. C., Halloran, P. F. & Oudit, G. Y. (2022). Transcriptomic Signatures of End-Stage Human Dilated Cardiomyopathy Hearts with and without Left Ventricular Assist Device Support. Int J Mol Sci. 23. [CrossRef]

- Yang, K. C., Yamada, K. A., Patel, A. Y., Topkara, V. K., George, I., Cheema, F. H., Ewald, G. A., Mann, D. L. & Nerbonne, J. M. (2014). Deep RNA sequencing reveals dynamic regulation of myocardial noncoding RNAs in failing human heart and remodeling with mechanical circulatory support. Circulation. 129, 1009-1021. [CrossRef]

- Muthiah, K., Humphreys, D. T., Robson, D., Dhital, K., Spratt, P., Jansz, P., Macdonald, P. S. & Hayward, C. S. (2017). Longitudinal structural, functional, and cellular myocardial alterations with chronic centrifugal continuous-flow left ventricular assist device support. J Heart Lung Transplant. 36, 722-731. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Liu, C. Y., Li, Y. S., Xu, J., Li, D. G., Li, X. & Han, D. (2016). Deep RNA sequencing elucidates microRNA-regulated molecular pathways in ischemic cardiomyopathy and nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Genet Mol Res. 15. [CrossRef]

- Chistiakov, D. A., Orekhov, A. N. & Bobryshev, Y. V. (2016). Cardiac-specific miRNA in cardiogenesis, heart function, and cardiac pathology (with focus on myocardial infarction). J Mol Cell Cardiol. 94, 107-121. [CrossRef]

- Song, Z., Gao, R. & Yan, B. (2020). Potential roles of microRNA-1 and microRNA-133 in cardiovascular disease. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 21, 57-64. [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, S., Kong, S. W., Lu, J., Bisping, E., Zhang, H., Allen, P. D., Golub, T. R., Pieske, B. & Pu, W. T. (2007). Altered microRNA expression in human heart disease. Physiol Genomics. 31, 367-373. [CrossRef]

- Thum, T., Galuppo, P., Wolf, C., Fiedler, J., Kneitz, S., van Laake, L. W., Doevendans, P. A., Mummery, C. L., Borlak, J., Haverich, A., Gross, C., Engelhardt, S., Ertl, G. & Bauersachs, J. (2007). MicroRNAs in the human heart: a clue to fetal gene reprogramming in heart failure. Circulation. 116, 258-267. [CrossRef]

- van Rooij, E., Sutherland, L. B., Liu, N., Williams, A. H., McAnally, J., Gerard, R. D., Richardson, J. A. & Olson, E. N. (2006). A signature pattern of stress-responsive microRNAs that can evoke cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 103, 18255-18260. [CrossRef]

- Sigutova, R., Evin, L., Stejskal, D., Ploticova, V. & Svagera, Z. (2022). Specific microRNAs and heart failure: time for the next step toward application? Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 166, 359-368. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A., Ji, Z., Zhang, R., Zuo, W., Qu, Y., Chen, X., Tao, Z., Ji, J., Yao, Y. & Ma, G. (2023). Inhibition of miR-195-3p protects against cardiac dysfunction and fibrosis after myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 387, 131128. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Ji, R., Liao, X., Castillero, E., Kennel, P. J., Brunjes, D. L., Franz, M., Möbius-Winkler, S., Drosatos, K., George, I., Chen, E. I., Colombo, P. C. & Schulze, P. C. (2018). MicroRNA-195 Regulates Metabolism in Failing Myocardium Via Alterations in Sirtuin 3 Expression and Mitochondrial Protein Acetylation. Circulation. 137, 2052-2067. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M., Zhang, C., Zhang, Z., Liao, X., Ren, D., Li, R., Liu, S., He, X. & Dong, N. (2022). Changes in transcriptomic landscape in human end-stage heart failure with distinct etiology. iScience. 25, 103935. [CrossRef]

- Dirkx, E., da Costa Martins, P. A. & De Windt, L. J. (2013). Regulation of fetal gene expression in heart failure. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1832, 2414-2424. [CrossRef]

- Eduardo Rame, J. (2017). Hemodynamic unloading and the molecular-functional phenotype dissociation in myocardial recovery. J Heart Lung Transplant. 36, 715-717. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A., Williamitis, C. A. & Slaughter, M. S. (2014). Comparison of continuous-flow and pulsatile-flow left ventricular assist devices: is there an advantage to pulsatility? Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 3, 573-581. [CrossRef]

- Lampert, B. C. & Teuteberg, J. J. (2015). Right ventricular failure after left ventricular assist devices. J Heart Lung Transplant. 34, 1123-1130. [CrossRef]

- Rodenas-Alesina, E., Brahmbhatt, D. H., Rao, V., Salvatori, M. & Billia, F. (2022). Prediction, prevention, and management of right ventricular failure after left ventricular assist device implantation: A comprehensive review. Front Cardiovasc Med. 9, 1040251. [CrossRef]

- Frankfurter, C., Molinero, M., Vishram-Nielsen, J. K. K., Foroutan, F., Mak, S., Rao, V., Billia, F., Orchanian-Cheff, A. & Alba, A. C. (2020). Predicting the Risk of Right Ventricular Failure in Patients Undergoing Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation: A Systematic Review. Circ Heart Fail. 13, e006994. [CrossRef]

- Løgstrup, B. B., Nemec, P., Schoenrath, F., Gummert, J., Pya, Y., Potapov, E., Netuka, I., Ramjankhan, F., Parner, E. T., De By, T. & Eiskjaer, H. (2020). Heart failure etiology and risk of right heart failure in adult left ventricular assist device support: the European Registry for Patients with Mechanical Circulatory Support (EUROMACS). Scand Cardiovasc J. 54, 306-314. [CrossRef]

- Balcioglu, O., Ozgocmen, C., Ozsahin, D. U. & Yagdi, T. (2024). The Role of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in the Prediction of Right Heart Failure after Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation: A Comprehensive Review. Diagnostics (Basel). 14. [CrossRef]

- Lippmann, M. R. & Maron, B. A. (2022). The Right Ventricle: From Embryologic Development to RV Failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 19, 325-333. [CrossRef]

- Havlenova, T., Skaroupkova, P., Miklovic, M., Behounek, M., Chmel, M., Jarkovska, D., Sviglerova, J., Stengl, M., Kolar, M., Novotny, J., Benes, J., Cervenka, L., Petrak, J. & Melenovsky, V. (2021). Right versus left ventricular remodeling in heart failure due to chronic volume overload. Sci Rep. 11, 17136. [CrossRef]

- Frisk, C., Das, S., Eriksson, M. J., Walentinsson, A., Corbascio, M., Hage, C., Kumar, C., Ekström, M., Maret, E., Persson, H., Linde, C. & Persson, B. (2024). Cardiac biopsies reveal differences in transcriptomics between left and right ventricle in patients with or without diagnostic signs of heart failure. Sci Rep. 14, 5811. [CrossRef]

- Dewar, M. B., Ehsan, F., Izumi, A., Zhang, H., Zhou, Y. Q., Shah, H., Langburt, D., Suresh, H., Wang, T., Hacker, A., Hinz, B., Gillis, J., Husain, M. & Heximer, S. P. (2024). Defining Transcriptomic Heterogeneity between Left and Right Ventricle-Derived Cardiac Fibroblasts. Cells. 13. [CrossRef]

- Batkai, S., Bär, C. & Thum, T. (2017). MicroRNAs in right ventricular remodelling. Cardiovasc Res. 113, 1433-1440. [CrossRef]

- Toro, V., Jutras-Beaudoin, N., Boucherat, O., Bonnet, S., Provencher, S. & Potus, F. (2023). Right Ventricle and Epigenetics: A Systematic Review. Cells. 12. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, D. T. & Pearson, G. D. (2009). Heart failure in children: part I: history, etiology, and pathophysiology. Circ Heart Fail. 2, 63-70. [CrossRef]

- Shaddy, R. E., George, A. T., Jaecklin, T., Lochlainn, E. N., Thakur, L., Agrawal, R., Solar-Yohay, S., Chen, F., Rossano, J. W., Severin, T. & Burch, M. (2018). Systematic Literature Review on the Incidence and Prevalence of Heart Failure in Children and Adolescents. Pediatr Cardiol. 39, 415-436. [CrossRef]

- Senekovič Kojc, T. & Marčun Varda, N. (2022). Novel Biomarkers of Heart Failure in Pediatrics. Children (Basel). 9. [CrossRef]

- Amdani, S., Auerbach, S. R., Bansal, N., Chen, S., Conway, J., Silva, J. P. D., Deshpande, S. R., Hoover, J., Lin, K. Y., Miyamoto, S. D., Puri, K., Price, J., Spinner, J., White, R., Rossano, J. W., Bearl, D. W., Cousino, M. K., Catlin, P., Hidalgo, N. C., Godown, J., Kantor, P., Masarone, D., Peng, D. M., Rea, K. E., Schumacher, K., Shaddy, R., Shea, E., Tapia, H. V., Valikodath, N., Zafar, F. & Hsu, D. (2024). Research Gaps in Pediatric Heart Failure: Defining the Gaps and Then Closing Them Over the Next Decade. J Card Fail. 30, 64-77. [CrossRef]

- Ragusa, R., Di Molfetta, A., Amodeo, A., Trivella, M. G. & Caselli, C. (2020). Pathophysiology and molecular signalling in pediatric heart failure and VAD therapy. Clin Chim Acta. 510, 751-759. [CrossRef]

- Khan, R. S., Kato, T. S., Chokshi, A., Chew, M., Yu, S., Wu, C., Singh, P., Cheema, F. H., Takayama, H., Harris, C., Reyes-Soffer, G., Knöll, R., Milting, H., Naka, Y., Mancini, D. & Schulze, P. C. (2012). Adipose tissue inflammation and adiponectin resistance in patients with advanced heart failure: correction after ventricular assist device implantation. Circ Heart Fail. 5, 340-348. [CrossRef]

- Mado, H., Szczurek, W., Gąsior, M. & Szyguła-Jurkiewicz, B. (2021). Adiponectin in heart failure. Future Cardiol. 17, 757-764. [CrossRef]

- Litviňuková, M., Talavera-López, C., Maatz, H., Reichart, D., Worth, C. L., Lindberg, E. L., Kanda, M., Polanski, K., Heinig, M., Lee, M., Nadelmann, E. R., Roberts, K., Tuck, L., Fasouli, E. S., DeLaughter, D. M., McDonough, B., Wakimoto, H., Gorham, J. M., Samari, S., Mahbubani, K. T., Saeb-Parsy, K., Patone, G., Boyle, J. J., Zhang, H., Zhang, H., Viveiros, A., Oudit, G. Y., Bayraktar, O. A., Seidman, J. G., Seidman, C. E., Noseda, M., Hubner, N. & Teichmann, S. A. (2020). Cells of the adult human heart. Nature. 588, 466-472. [CrossRef]

- Tucker, N. R., Chaffin, M., Fleming, S. J., Hall, A. W., Parsons, V. A., Bedi, K. C., Jr., Akkad, A. D., Herndon, C. N., Arduini, A., Papangeli, I., Roselli, C., Aguet, F., Choi, S. H., Ardlie, K. G., Babadi, M., Margulies, K. B., Stegmann, C. M. & Ellinor, P. T. (2020). Transcriptional and Cellular Diversity of the Human Heart. Circulation. 142, 466-482. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Yu, P., Zhou, B., Song, J., Li, Z., Zhang, M., Guo, G., Wang, Y., Chen, X., Han, L. & Hu, S. (2020). Single-cell reconstruction of the adult human heart during heart failure and recovery reveals the cellular landscape underlying cardiac function. Nat Cell Biol. 22, 108-119. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, P. S., Parkin, R. K., Kroh, E. M., Fritz, B. R., Wyman, S. K., Pogosova-Agadjanyan, E. L., Peterson, A., Noteboom, J., O’Briant, K. C., Allen, A., Lin, D. W., Urban, N., Drescher, C. W., Knudsen, B. S., Stirewalt, D. L., Gentleman, R., Vessella, R. L., Nelson, P. S., Martin, D. B. & Tewari, M. (2008). Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 105, 10513-10518. [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, N., Guan, W., Capaldo, B., Mackey, A. J., Carlson, M., Ramakrishnan, S., Walek, D., Gupta, M., Mitchell, A., Eckman, P., John, R., Ashley, E., Barton, P. J. & Hall, J. L. (2014). Identification of a new target of miR-16, Vacuolar Protein Sorting 4a. PLoS One. 9, e101509. [CrossRef]

- Qian, L., Zhao, Q., Yu, P., Lü, J., Guo, Y., Gong, X., Ding, Y., Yu, S., Fan, L., Fan, H., Zhang, Y., Liu, Z., Sheng, H. & Yu, Z. (2022). Diagnostic potential of a circulating miRNA model associated with therapeutic effect in heart failure. J Transl Med. 20, 267. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T., O’Brien, E. C., Rogers, J. G., Jacoby, D. L., Chen, M. E., Testani, J. M., Bowles, D. E., Milano, C. A., Felker, G. M., Patel, C. B., Bonde, P. N. & Ahmad, T. (2017). Plasma Levels of MicroRNA-155 Are Upregulated with Long-Term Left Ventricular Assist Device Support. Asaio j. 63, 536-541. [CrossRef]

- Dlouha, D., Ivak, P., Netuka, I., Novakova, S., Konarik, M., Tucanova, Z., Lanska, V., Hlavacek, D., Wohlfahrt, P., Hubacek, J. A. & Pitha, J. (2021). The effect of long-term left ventricular assist device support on flow-sensitive plasma microRNA levels. Int J Cardiol. 339, 138-143. [CrossRef]

- Ragusa, R., Di Molfetta, A., D’Aurizio, R., Del Turco, S., Cabiati, M., Del Ry, S., Basta, G., Pitto, L., Amodeo, A., Trivella, M. G., Rizzo, M. & Caselli, C. (2020). Variations of circulating miRNA in paediatric patients with Heart Failure supported with Ventricular Assist Device: a pilot study. Sci Rep. 10, 5905. [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, M., Bonora, M., Baldetti, L., Pieri, M., Scandroglio, A. M., Landoni, G., Zangrillo, A., Foglieni, C. & Consolo, F. (2023). Left ventricular assist devices promote changes in the expression levels of platelet microRNAs. Front Cardiovasc Med. 10, 1178556. [CrossRef]

- Richards, A. M. (2018). N-Terminal B-type Natriuretic Peptide in Heart Failure. Heart Fail Clin. 14, 27-39. [CrossRef]

- Poredos, P., Jezovnik, M. K., Radovancevic, R. & Gregoric, I. D. (2021). Endothelial Function in Patients With Continuous-Flow Left Ventricular Assist Devices. Angiology. 72, 9-15. [CrossRef]

- Pasławska, M., Grodzka, A., Peczyńska, J., Sawicka, B. & Bossowski, A. T. (2024). Role of miRNA in Cardiovascular Diseases in Children-Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci. 25. [CrossRef]

- Loyaga-Rendon, R. Y., Kazui, T. & Acharya, D. (2021). Antiplatelet and anticoagulation strategies for left ventricular assist devices. Ann Transl Med. 9, 521. [CrossRef]

- Leebeek, F. W. G. & Muslem, R. (2019). Bleeding in critical care associated with left ventricular assist devices: pathophysiology, symptoms, and management. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2019, 88-96. [CrossRef]

- Leng, Q., Ding, J., Dai, M., Liu, L., Fang, Q., Wang, D. W., Wu, L. & Wang, Y. (2022). Insights Into Platelet-Derived MicroRNAs in Cardiovascular and Oncologic Diseases: Potential Predictor and Therapeutic Target. Front Cardiovasc Med. 9, 879351. [CrossRef]

- Gutmann, C., Joshi, A., Zampetaki, A. & Mayr, M. (2021). The Landscape of Coding and Noncoding RNAs in Platelets. Antioxid Redox Signal. 34, 1200-1216. [CrossRef]

- Kabłak-Ziembicka, A., Badacz, R., Okarski, M., Wawak, M., Przewłocki, T. & Podolec, J. (2023). Cardiac microRNAs: diagnostic and therapeutic potential. Arch Med Sci. 19, 1360-1381. [CrossRef]

| Study | Methodology | Baseline patient characteristics | HF etiology | LVAD device | Time of LVAD support and/or duration of HF in days | miRNAs of interest | Major findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schipper et al. [80] | qPCR, 4 miRs |

LVAD:17[ male 88%; age 40 ±13 years, NYHA class IV (%) 100] NF: 6 |

ICM – 8 (47%) NICM - 9 (53%) |

pf-LVAD (HeartMate, Thoratec, Pleasanton, CA) | LVAD support: 262±129 (range 57-557) HF duration - not reported |

miR-1, 133a, 133b and miR-208 | Upregulation and partial normalization of miR-1, mir-133a, and miR-133b in ICM; further decrease in DCM; similar changes of miR-208 - expression level too low for reliable statistical analysis |

| Ramani et al. [101] | PCR-based array; qPCR, 376 miRs |

Test cohort: recovered 7 [male 50 %; age 40±12 years; EF(% + SE) 18±5] dependent 7 (male 50 %, age 42±15 years; LVEF (%) 15±5) Validation cohort; recovered 7 [male 71 %, age 27±8 years; LVEF (%+SE) 18±5); dependent (male 71 %; age 33±9 years; EF (%+SE) 17±5] Paired pre- and post-LVAD samples: 6 [male 50 %; age 54±18 years; LVEF (%+SE) 18±5] NF: 7 [male 50 %; age 36±10 years; LVEF (%+SE) 65±10] |

NICM - 100 % | pf-LVAD (Thoratec, Pleasanton, CA) and rotary cf-LVAD support Test cohort: recovered -rotary 14 %; dependent – rotary – 13 % Validation cohort: recovered – rotary 71 %; dešendent – rotary 42 % |

LVAD support: Test cohort: recovered 53±31; dependent 61±29 ; Validation cohort: recovered 433±250; dependent 369±167; Paired pre- and post-LVAD samples: 144±67 HF duration: Test cohort:: recovered 62±49; dependent 75±58 Validation cohort: recovered 680±1117 ; dependent 771±802 Paired pre- and post-LVAD samples: 210±108 |

miR-1, 15b, 21, 23a, 26a, 27a, 103, 133a, 133b, 142-3p, 181b, 195, 208, 376a, and miR-424 | Downregulated expression of miR-23a and miR-195 in the LVAD-recovered versus LVAD-dependent myocardial tissue probably reflects the less serious nature of HF at the time of LVAD implantation; no notable change in miR expression between pre- and post-LVAD patient group |

| Lok et al. [82] | qPCR, 1 miR |

LVAD - 18 [male 78 %; age 43.0 (28.0–48.0) years; NYHA IV (%) 100]; 15 underwent HTx NF: 10 |

NICM - 100 % | cf-LVAD (Heart-Mate II, Thoratec, CA) | LVAD support (HTx patients): 282 (207–521) HF duration: 1675 (416–1954) |

miR-137↑ | α-1-antichymotrypsin (ACT) confirmed as a direct target for miR-137; miR-137 expression is inversely correlated with ACT mRNA levels in myocardial tissue |

| Barsanti et al. [83]. | RNA sequencing, qPCR, 23 miRs | HTx-LVAD: 8 [male 100 %; age 46 ± 4 years; LVEF (%+SE) 21 ± 2] HTx-ctrl: 9 [male 55.5 %; age 52 ± 3 years; LVEF (%+SE) 26 ± 2] All patients; NYHA class III-IV; LVEF < 35 % at HTX or LVAD implantation |

HTx-LVAD – ICM - 12.5 %, DICM - 87.5 % HTx-ctrl: NICM – 22 %, NICM – 78 % |

cf-LVAD: 7 [ 4 HeartMate II (Thoratec, Pleasanton, CA), 2 De Bakey (MicroMed Technology, Houston, TX), 1 INCOR (Berlin Heart AG, Germany)] pf-LVAD: 1 Best BEAT (NewCorTec, Pomezia, Italy) |

HTX-LVAD support: 357 ± 66 HF duration: not reported |

miR-23a-5p↑, 27a-5p↑, 29b-3p↓, 135a-5p↓, 142-3p↑, 142-5p↑, 144-5p↑, 146b-3p↑, 216a-5p↓, 223-3p↑, 335-3p↑, 338-3p↑, 374b-5p↓, 376a-3p↓, 378g↑, 628-5p↑, 3195↓, 4284↓, 4461↑, 4532↓, 4485↓, 4792↓ and miR-5683↑ | No paired LVAD samples; 13 upregulated and 10 downregulated miRs in the LVAD group with respect to the HTx-ctrl group; a positive correlation was found between some miRs and cardiac index (miR-27a-5p, miR-142-3p, miR-142-5p, miR-223-3p, miR-338-3p, and miR-378g) and pulmonary vascular resistance values (miR-29b-3p and miR-374b-5p) |

| Lok et al. [84]. | PCR-based array; qPCR, 26 miRs | Test cohort – pf-LVAD: 5 [male 100 %; age 38 ± 7 years; NYHA IV (%) 100]; cf-LVAD: 5 [males 80 %; age 49 ± 6 years; NYH class IV (%) 100] Validation cohort - pf-LVAD: 17 [male 82 %; age 45 ± 3 years; NYHA class IV (%) 100]; cf-LVAD : 17 [male 94 %, age 39 ± 3 years; NYHA IV (%) 100] |

Test cohort: NICM – 100 % Validation cohort: NICM 100 % |

Test cohort – pf-LVAD: HeartMate (X)VE 60 %; Thoratec 20 %; Novacor 20 %; cf-LVAD: HeartMate II 100% Validation cohort – pf-LVAD: HeartMate-(X)VE 70 %; Thoractec 18 %; Novacor 6 %; HeartMate-IP 6 %; cf-LVAD: HeartMate-II 100 % |

Test cohort – pf-LVAD support 204 (180–301); HF duration 261 (26–1023); cf-LVAD support 489 (238–897); HF duration 1747 (1531–3316)Validation cohort – pf-LVAD support 282 (197–512); HF duration 1754 (750–2489); cf-LVAD support 206 (190–317); HF duration 398 (49–1344) | let-7i, miR-1-1, 17*, 21, 22, 23a*, 23a, 25, 29b-1*, 92a, 129*↑, 133a, 133b, 136, 137, 142-5p, 146a↑, 155↓, 199a-5p, 199b-5p, 208a, 221↓, 222↓, 320d, 378, and miR-378* | Five miRNAs (miR-129*, 146a, 155, 221, and miR-222) displayed a similar expression pattern among cf- and pf-LVAD devices, whereas others only changed significantly during pf-LVAD (miR-let-7i, 21, 378, and miR-378*) or cf-LVAD support (miR-137); no significant pre- and post-LVAD changes within individual patients |

| Morley-Smith et al.[105]. | qPCR, 2 miRs | Paired pre- and post-LVAD samples - n = 10; no gender and age data available | ICM - 53 % NICM - 47 % |

cf-LVAD (Heart-Mate II, Thoratec, CA) | LVAD support: 200 (133–299) days | miR-483-3p and miR-1202 | Noticeable, although nonsignificant, up-regulation of miR-483–3p, no change in myocardial miR-1202 expression |

| Ragusa et al. [106] | NGS/RNA sequencing, qPCR, 463 miRs | Pediatric HF:13 [male 46 %; age 29 (5–123) months; LVEF (%) 19 (13.75–20.75)] Adult HF: 21 [male 66.7 %, age 60 (50-64) years, LVEF (%) 22.5 (19.5–25)] |

DCM -69.2 % LVNC – 15.4 % RCM – 15.4 % |

Pediatric HF: pf-LVAD n=3 (Thoratec, Berlin Heart Excor); cf-LVAD n=1 (Jarvik); BiVAD n=3 (BiVAD; Thoratec, Berlin Heart Excor) | Not reported | NGS: miR-19a-3p↓, 29b-1-5p↑, 199b-5p↓, 199a-5p↓, 338-3p↑, and miR-1246 ↓ qPCR: miR-1246↓, -19a-3p↓ and miR-199b-5p↓ |

Downregulated expression of miR-19a-3p, miR-199b-5p, and miR-1246 in post-LVAD tissue; down-regulatory effect of miR-19a-3p on cTnC expression; no data for miRNA expression in adult HF patients |

| Ragusa et al. [107] | NGS/RNA sequencing, qPCR, 463 miRs | Pediatric HF:13 [male 46 %; age 29 (5–123) months; LVEF (%) 19 (13.75–20.75)] Plasma samples: 9 pediatric HF patients and 107 healthy children |

DCM 70 % LVNC – 15 % RCM – 15 % |

Pediatric HF: pf-LVAD n=3 (Thoratec, Berlin Heart Excor); cf-LVAD n=1 (Jarvik); BiVAD n=3 (BiVAD; Thoratec, Berlin Heart Excor) | Not reported | NGS: miR-19a-3p↓, 29b-1-5p↑, 199b-5p↓, 199a-5p↓, 338-3p↑, and miR-1246 ↓ qPCR: miR-1246↓, -19a-3p↓ and miR-199b-5p↓ |

myocardial AdipoR2 expression levels were inversely related to miR-19a-3p, miR-199b-5p, and miR-1246 expression; miR-1246 was also negatively associated with T-cad; no relationship was observed among miRNAs and AdipoR1; in vitro validation confirmed regulatory role of miR-1246 and miR-199b-5p on AdipoR2 and miR-199b-5p on T-cad |

| Matkovich et al. [109]. | Microarray, 467 miRs |

LVAD: 10 [male 80 %; age 53 ± 14; ] end-stage HF: 17 [male 64 %; age 56 ± 6; LVEF (%+SE) 14 ± 6 ] NF: 11 [male 36 %; age 56 ± 6, LVEF (%+SE) 62 ± 5 ] |

LVAD: ICM – 40%, NICM – 60% End-stage HF: ICM - 41%, NICM - 59 % |

Not reported | LVAD support- average 51 days Hf duration: LVAD - 1.7 ± 1.0 months; end-stage HF - 68 ± 60 months |

let-7f, let-7g↓, let-7i, miR-1↓, 15a, 16, 21, 22↓, 23a, 24↓, 26a, 26b↓, 27a↓, 27b, 29a, 29b↓, 30b↓, 30a-5p, 30c, 30d, 103, 125b, 126↓, 130a, 133a, 133b, 143↓,195↓, 199a-3p, 378, 499↓, and miR-638 | Eight miRs showed full normalization, while twelve miRs showed significant decreases in expression levels between the failing and LVAD-supported myocardium, no paired LVAD samples; combined miRNA/mRNA signature sufficiently effective in classifying different HF types and functional states |

| Akat et al. [90] | NGS/RNA sequencing; > 500 miRs | NICM 21 [male 95 %; age57 (33–78); LVEF median (range) 15(10–30)] ICM: 13 [male 92 %; age 66 (51–78) LVEF median (range) 17.5(10–22) ] NF; 8 [male 63 %; age 48 (2–80) LVEF, median(range) 57/65(6 unknown) ] Fetal hearts:5 fetal (gestational age 19–24 weeks), LVAD:: 8 NICM, 7 ICM |

NICM- 62 % ICM – 38 % |

pf-LVAD: HeartMate I, Thoratec Corp., Pleasanton, California) cf-LVAD; HeartMate II, (Thoratec Corp., Pleasanton, California); HeartWare (HeartWare International, Framingham, MA, USA) |

Not reported | let-7-f, let-7g, let-7i, miR-1, 15a, 15b, 16, 17*, 19a, 21, 22. 23a*, 23a, 24, 25, 26a, 26b, 27a, 27a*↑, 27b, 29a, 29b, 29b-1*, 30b, 30c, 30d, 92a, 103, 125b, 126, 130a, 133a, 133b, 136-3p, 136-5p, 137, 142-3p, 142-5p, 143, 146a, 155, 181b, 195, 199a-5p, 199a-3p, 199b-5p, 204, 208a, 208b, 216a, 217, 221, 222, 223, 335-3p, 338-3p, 376a, 374b, 376a-3p, 378, 378*, 424, 483-3p, 499, 628 and miR-2114 | Marginal difference in miRs signature between ICM and NICM and no difference in miRNA cistron expression among paired myocardial samples before and after LVAD support; miRNA changes in HF tissues partially resembled that of fetal myocardium |

| Parikh et al. [111]. | Microarray, 58 miRs | LVAD: 8 [male 87.5%); age 57 (45–59) years; LVEF (5) 13 (10–20); LVEF<50% 50 %; NYHA II/IIV 87,5 % ] HF without LVAD: 8 [male 87.5 %; age 50 (43–54) years; LVEF (%) 18 (15–26); LVEF<50% 87.5%; NYHA II/IIV 87.5 %] NF: 6 [age 45 (40–51) years] |

LVAD: NICM – 100 % HF without LVAD: NICM – 100 % |

Not reported | LVAD support: 156 days (131–268 ) HF duration: LVAD - 48 (30–120); HF without LVAD - 39 (6–108) |

LV; miR-10b↓, 95, 103b, 135b, 182↓, 187, 208a, 218,223↓, 224, 299-5p↓, 329, 373, 374b↓, 431, 451↓, 495, 548x↓, 601↓, 628-5p↓, 940↓, 1226, 1226*↓, 1825↓, 3128, 3187-3p↓, 3201, 3910↓, 4269, 4270↓, 4458, 4521, 4539↓, 4687-3p↓, 4689↓, 4741↓, 4793-3p, ENSG00000202498↓ and ENSG00000202498_x↓ RV: miR-10b↓, 21*, 92a-1, 95, 124, 138, 181a-2↓, 182↓, 216a, 217, 373, 431, 451↓, 1247, 1972, 3065-3p, 4461, 4524, and HBII-52-32_x↓ |

miR-4458 in the LV and miR-21*, miR-1972, miR-4461 in the RV were significantly normalized following LVAD implantation. |

| Yang et al. [112] | NGS/RNA sequencing, 1007 miRs | LVAD: 16 [male 81 %, age 60 (54-65) years; LVEF < 35 %] NF: 8 [male 87.5 %; age 53.5 (52-58) years ] |

ICM - 50%, NICM - 50% | Not reported | 305±50 days (range 111 - 690) | miR-23b-5p↑, 93-3p↓, 130b-5p↓, 183-3p↓, 193b-5p↑, 301a-5p↓, 302a-3p↑, 363-3p↓, 365a-3p↑, 378a-3p↑, 378e↑, 378f↑, 425-5p↓, 429, 548d-5p↓, 665↑, 760, and miR-4484↑ | Only seven miRs [miR-365a-3p and miR-378a-3p in ICM and miR-93-3p, miR-193b-5p, miR-425-5p, miR-548d-5p, and miR-760 in NICM] normalized with LVAD support |

| Muthiah et al. [93] | RNA sequencing, 100 miRs | HF: 37 [male 86.5 %; age 49.6 ± 13.1 years; LVEF (%) 23.7±7.7; INTERMACS – I 32.4 %, II 62.1 %, III 5.4 % ] 12 paired pre- and post-LVAD samples were used for RNA sequencing |

NICM- 54 % ICM – 35 % HCM – 8 % CHD – 3 % |

cf-LVAD HeartWare (HeartWare International, Framingham, MA, USA); Five patients had biventricular support with a HeartWare centrifugal-flow LVAD placed in the left LV and RV. |

HF duration: 83 ±68.9 months Paired samples LVAD support: 307 ±132 days |

let-7f-1, miR-1-1, 1-2, 10b-5p, 15a, 15b, 16-1, 21, 23a, 23b, 24-1, 26a-1, 27b, 29a,29a-5p, 29b-1, 30a, 30c-1, 30d,30e-5p, 34a, 34b, 34c, 92a-1, 100, 101-1-5p, 103a-1, 125b-1, 129-1, 130a, 133a-1, 133a-2, 133b,133b-5p, 140-5p, 145-5p, 151a-5p, 155, 182, 192-5p, 195, 199b, 199a-1, 206, 210, 211, 212, 208a, 208b, 214, 214-5p, 221, 328, 378a, 378b, 378c, 378d-1, 378d-2, 378e, 378f, 378g, 378h, 378i, 378j, 423, 451b, 452-5p, 455-5p, 489, 526a-1, and miR-1307-5p | No significant changes in miRs expression were detected |

| Study | Methodology | Baseline patient characteristics | HF etiology | LVAD device | Time of LVAD support and/or duration of HF in days | miRNAs of interest | Major findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akat et al. [110] | RNA sequencing | Plasma - Stable HF: 14 [male 79 %, age 63(49–71) years; LVEF,median(range) 22(10–43)] Advanced HF at LVAD implantation: 24 [male 92 %; age 66(33–78) years; LVEF, median(range) 18(10–24)] Advanced HF 3 (n=10) and 6 months after LVAD implantation (n =10), and at LVAD explantation (n=/) NF: 13 [male 69 %; age 60(32–70) years] Serum – Advanced HF: 7; LVAD explantation: 7; NF 4 |

ICM NICM |

pf-LVAD: HeartMate I, Thoratec Corp., Pleasanton, California) cf-LVAD; HeartMate II, (Thoratec Corp., Pleasanton, California); HeartWare (HeartWare International, Framingham, MA, USA) |

Measured at baseline and 3 and 6 months following LVAD implantation | miR-1-1, 22, 122 , 126, 133b, 203, 208a, 208b, 210, 216a, 375, 499, 1180, and miR-1908 | Up to 140-fold increase in heart and muscle-specific miRs in advanced HF compared to healthy individuals, alongside elevated cardiac troponin I (cTnI) levels indicating myocardial injury; the levels dropped as early as 3 months after the initiation of LVAD support, approaching normal levels, but rose again at LVAD explantation; higher levels of miR-208a, miR-208b, and miR-499 in advanced HF positively correlated with the protein levels of cTnI |

| Morley-Smith et al. [105] | PCR array; qPCR, 1113 miRs | Whole cohort: 19 [male 79 %, age 52 (30–61) years; LVEF (%), median (IQR) 15 (15–25) ] Good responders: 7 [male 71 %; age 40 (14–62) years; LVEF (%), median (IQR) 20 (10–30)] Poor responders: 6 [male 83 %; age 55 (36–60) years; LVEF (%), median (IQR) 15 (13–23)] |

Whole cohort: ICM 53 %; NICM 47 % Good responders: ICM 29 %; NICM 71 % Poor responders: ICM 50 %; NICM 50 % |

Cf-LVAD Thoratec HeartMate II | Measured at baseline and 3, 6, 9, and 12 months following LVAD implantation | PCR array - miR-33a↑, 1254↑, 219-1-3p↑, 483-3p↑, 548 l↓, 557↑, 938↑, 1202↑, 1250↑, 1275↑, 4266↑, and miR-4325↓ qPCR – miR-488-3p↑ and miR-1202 |

Plasma miR-483-3p levels exhibit significant up-regulation with LVAD support that mirrors the suppression of NT-proBNP levels; miR-1202 levels correlate with change in NT-proBNP at three months following LVAD support, thus stratifying the patients into poor vs. good responders; potentially valuable noninvasive biomarkers for monitoring (miR-483-3p) and predicting (miR-1202) patient response to LVAD therapy |

| Adhikari et al. [129] | qPCR, 4 miRs | end-stage HF: 10 [male 57 %; age 60 years; ] NF: 9 [male 57 %; age 45±5 ] Paired pre- and post-LVAD blood samples: 9 [males 89 %; age 60 years; LVEF < 25 % ] NF: 6 [males 60%; age 54±4 ] |

Blood – ICM- 55.5 % NICM -44.5 |

Not reported | Measured at baseline and 7 days following LVAD implantation | miR-15a↓, 16↑, 103, and miR- 195↓ | Downregulated expression of circulatory miR-16 in HF patients; miR-16 targets VPS4a; LVAD support increases the levels of miR 16 thus decreasing the levels of VPS4a |

| Lok et al. [104] | Microarray, qPCR, 4 miRs | Test cohort: 5 [male 40%; age 42 ± 6 ; NYHA class IV(%) 100 %] Validation cohort: 18 [male 78 %; age 45 ± 3; NYHA class IV (%) 100% ] |

NICM 100 %; | cf-LVAD HeartMate-II | Measured at baseline and 1, 3, and 6 months following LVAD implantation | miR-21↓, 146a, 221 and miR-222 | A two-fold upregulation of miR-21 in pre-LVAD samples and decreased expression following LVAD support but did not normalize, fluctuating expression pattern of miR-146a, miR-221, and miR-222 with a tendency to reduction following LVAD support |

| Qian et al. [137] | qPCR, 89 miRs | Discovery phase - In hospital/Out-of-hospital: 40 [age 64.40±11.88; LVEF (%) 34.05±5.77] Training phase – HF 30; NF 15 Validation cohort: HF 50; NF 25 |

ICM- 26 % NICM- 53 % Other – 21 |

External dataset reported by Akat et al. [110]. | External dataset reported by Akat et al. [110]. |

Discovery phase - let-7a, let-7b, let-7c, let-7e, let-7f, let-7g, let-7i, miR-10a, 15a, 15b, 16, 16, 17, 18a, 18b, 19a, 19b, 20b, 21, 23a, 24, 26, 27a, 27b, 29a, 29b, 30a-5p↓, 30d, 92, 93, 99b, 100↓, 103a, 106a, 106b, 122, 125b, 126, 129, 130a, 133a, 133b, 136, 140, 143, 145, 150, 151-5p, 155, 181b, 181a, 182, 191, 195, 199a, 199a-3p, 208a, 214, 221, 222, 302a, 302c, 302d, 302e, 320a↓, 320b, 324-5p, 342, 346, 369-5p, 329, 382, 423-3p, 423-5p, 433, 484, 486, 493, 495, 499a, 499b-5p, 499b-3p↓, 543, 622, 638, 654-5p↑, 665, 675, 762, and miR-885-5p Training and validation phase - miR-30a-5p and miR-654-5p |

Circulatory miR-30a-5p, miR-100, miR-499b, miR-320a, and miR-433 showed significant downregulation, while the levels of miR-654-5p were upregulated in HF patients compared to control; a significantly negative correlation of circulatory miR-654-5p and a positive correlation of miR-30a-5p with NT-proBNP plasma levels of HF patients; a novel 2-circulating miRNA (miR-30a-5p/miR-654-5p) model with diagnostic and prognostic potential |

| Wang et al. [138] | qPCR, 23 miRs | HF – 40 [male 72.5%; age 67 (51–74); LVEF (%) 20 (15-20); INTERMACS I/II 57.5% ] NF - 7 |

Not reported | Cf-LVAD - Heartmate II (62.5%), HeartWare | SMeasured at serial blood draws - median 96.5 (72–150) days post-LVAD implantation | miRNA-1, 10a, 15b, 16, 21, 24, 27a, 27b, 29a, 92a, 103, 126, 133a, 146a, 146b, 155↑, 159a, 195, 221, 222, 320, 423, and miR-872 | Upregulated expression of circulatory miR-155 following LVAD support |

| Dlouha et al. [139] | qPCR, 9 miRs | LVAD treatment- 33 [male 85 %; age 55.7 ± 11.6 ] NF 13 [male 61.5 %; age 50.1 ± 13.5 years; LVEF (%+SE) 18.9 ± 3.2] |

ICM: 48.5 % NICM – 51.5 % |

cfLVAD: axial HeartMate II – 42 % centrifugal HeartMate III 58 % |

Measured at baseline and 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after LVAD implantation | miR-10a, 10b, 21, 126↑, 146a↑, 146b, 155, 663a, and miR-663b | Iow pulsatile flow up-regulates plasma levels of circulating flow-sensitive miRNAs; increased plasma levels of miR-126 and miR-146a following cf-LVAD support; positive association between miR-155 and Belcaro score; an inverse correlation between miR-126 and endothelial function, measured as the reactive hyperemia index |

| Ragusa et al. [140] | NGS/RNA sequencing, qPCR, 340 miRs | NGS analysis – HF 5 [male 40 %; age 13.8±6.25 years; LVEF (%+SE) 16.6±1.7 ] LVAD treatment – 8 [male 37.5 %; age 25.25 ± 10.9 years; LVEF (%+SE) 21.7 ± 5.6] |

NGS HF - NICM 80 %; LVNC 20 % LVAD treatment – NICM 75 %, LVNC 25 % |

Berlin Heart Chamber | Measured at baseline and 4 hrs, and 1, 3, 7, 14, and 30 days after LVAD implantation LVAD support (179 ± 34.71 days) |

miR-16-5p, miR-30a-5p, 127-3p, miR-150-3p↑, miR-375↑, 409-3p↓, 432-5p, 483-3p, 483-5p↓, 485-3p↓, miR-941. 3135b, and miR-4433b-3p | miR-409-3p, miR-483-3p, and miR-485-3p were downregulated up to undetectable levels, while miR-432-5p showed a trend to decrease, while the circulatory levels of miR-150-3p and miR-375 increased after one month of LVAD implantation; in vitro data confirmed coagulation factors 7 (F7) and F2a as targets of hsa-miR-409-3p; a potential role for circulatory miRs, particularly 409-3p, as an early biomarker for monitoring hemostasis-related adverse events in pediatric LVAD-supported HF patients |

| Lombardi et al. [141] | qPCR, 12 miRs | HF-15 [male 100 %; age 64 (63–71) years; chronic HF 73 % ] Control – 5 (male 100 %; age 53 (47–61) years] |

ICM – 60 % NICM - 40 % |

cf-LVAD: Heartmate III (HM3; Abbott, United States) 53 %; HVAD (Medtronic Inc., United States) 47 % | measured before and 1, 6, and 12 months following LVAD implantation | miR-19b-3p, 20b-5p, 25-3p↑, 126-5p, 144-3p, 151a-3p, 223-3p, 320a, 374b-5p, 382-5p, 451a↑, 454-3p, 16-5pa and miR-103a-3pa |

significantly different pre-implant levels of platelet miR-126, miR-374b, miR-223, and miR-320a in HF patients compared to controls. The LVAD patients suffering from bleeding had significantly higher pre-implant levels of platelet miR-151a and miR-454. The same miRs were also differentially expressed in these patients following LVAD implantation early before the clinical manifestation of the bleeding events. The expression levels of platelet miR-25, miR-144, miR-320, and miR-451a changed significantly over the course of LVAD support, indicating partial or increasing platelet activation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).