Submitted:

08 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Feline Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Phenotype

3. Genetic Influence

4. Pathophysiology of Feline Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

5. Clinical Manifestations

6. HCM ACVIM Consensus

7. Diagnostic Tools for Feline HCM

7.1. Clinical-Laboratory Diagnosis

7.2. Imaging Diagnosis

7.2.1. Thoracic Radiographs

7.2.2. Electrocardiography

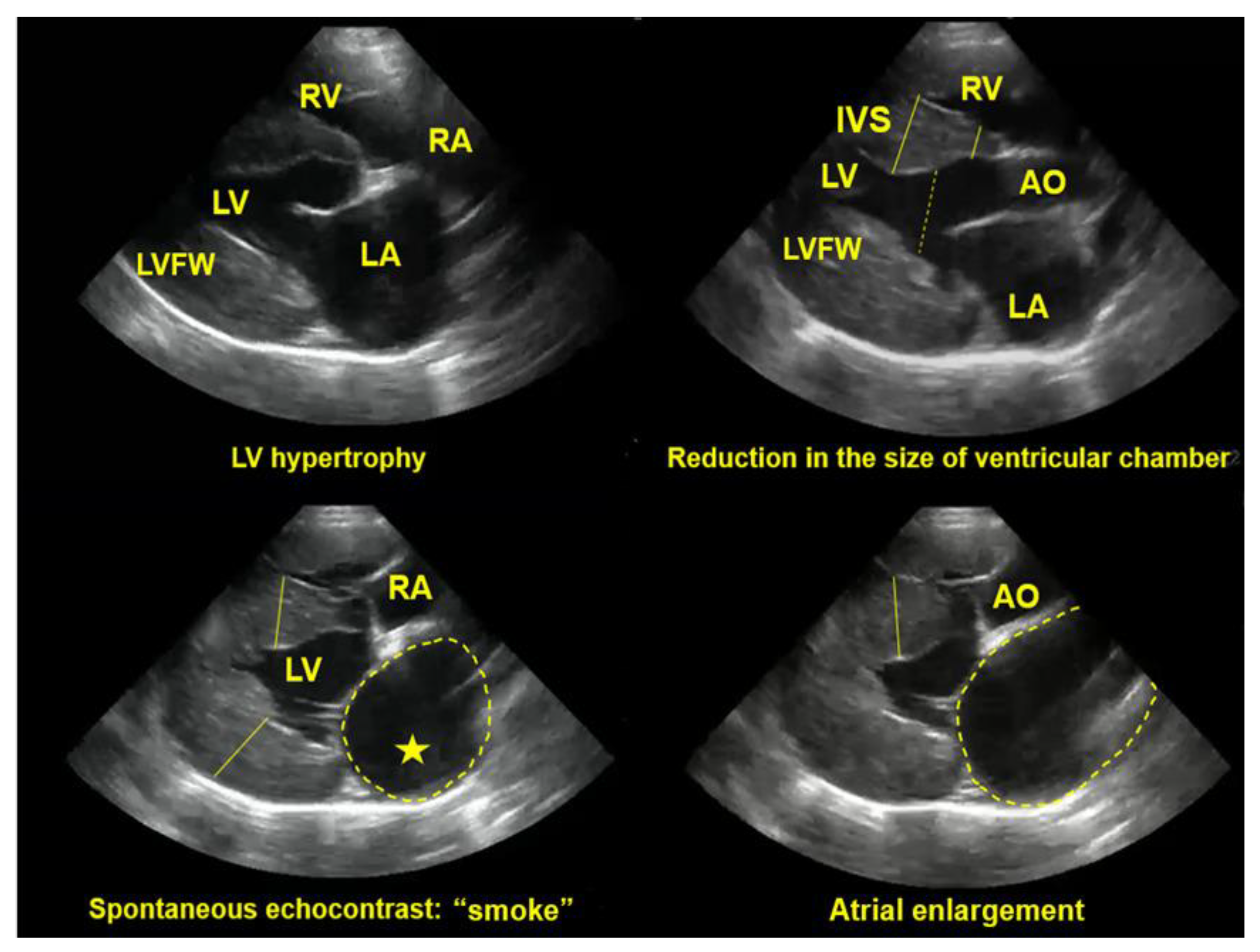

7.2.3. Echocardiography

7.3. Biomarkers and Other Diagnostic Options

8. Treatment Strategies

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A31P | A31P mutation |

| ACE2 | angiotensin II-converting enzyme |

| ACVIM | American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine |

| ALMS1 | ALMS1 variant |

| AMC | arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy |

| ANG II | angiotensin II |

| ANP | atrial natriuretic peptide |

| AO | aorta |

| ATE | arterial thromboembolism |

| BNP | B-type natriuretic peptide |

| cfDNA | cell-free DNA |

| CHF | chronic heart failure |

| citH3 | citrullinated histone H3 |

| CRI | continuous infusion |

| cTnI | cardiac troponin-I |

| DCM | dilated cardiomyopathy |

| ESC | European Society of Cardiology |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| HCM | hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| IL-6 | interleukin 6 |

| IV | intravenous |

| IVRT | isovolumetric relaxation |

| IVSd | interventricular septum in diastole |

| IVSs | interventricular septum in systole |

| LA | LA left atrium |

| LAA | left atrial appendage |

| LA/Ao | left atrium:aortic root ratio |

| LAMP | loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay |

| LFD | lateral flow dipstick |

| LOX | lysyl oxidase |

| LV | LV left ventricle |

| LVFW | left ventricle free wall thickness |

| LVFWd | left ventricle free wall thickness in diastole |

| LVFWs | left ventricle free wall thickness in systole |

| LVOT | left ventricular outflow tract |

| LVOTO | left ventricular outflow tract obstruction |

| MAPSE | mitral annular plane systolic excursion |

| MCP-1 | monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 |

| mTOR | mammalian homologue TOR protein |

| MYBPC3 | MYBPC3 gene |

| MYH7 | MYH7 gene |

| NETs | neutrophil extracellular traps |

| NLR | neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio |

| NTproANP | N-terminal pro-atrial natriuretic peptide |

| NTproBNP | N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide |

| PO | orally |

| PVF | pulmonary venous flow |

| R820W | R820W mutation |

| RA | right atrium |

| RAS | renin angiotensin system |

| RMC | restrictive cardiomyopathy |

| RV | right ventricle |

| RVOT | right ventricular outflow tract |

| SAM | systolic anterior movement |

| SF% | shortening fraction |

| SQ | subcutaneous |

| T4 | thyroxine |

| TGF-β | transforming growth factor beta |

| TNNT2 | TNNT2 intronic variant |

| TpTe | Tpeak–Tend |

| TT-LD | color-coded tissue tracking |

| VHS | vertebral heart size |

| VLAS | vertebral left atrial size |

References

- Garcia, R.C.M.; Amaku, M.; Biondo, A.W.; Ferreira, F. Dog and cat population dynamics in an urban area: evaluation of a birth control strategy. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2018, 38, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.A.; Oyama, M.A.; Rush, J.E.; Rozanski, E.A.; Singletary, G.E.; Brown, D.C.; Cunningham, S.M.; Fox, P.R.; Bond, B.; Adin, D.B.; Williams, R.M.; MacDonald, K.A.; Malakoff, R.; Sleeper, M.M.; Schober, K.E.; Petrie, J.P.; Hogan, D.F. Perceptions of Quality of Life and Priorities of Owners of Cats with Heart Disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2010, 24, 1421–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, P.R.; Keene, B.W.; Lamb, K.; Schober, K.A.; Chetboul, V.; Luis Fuentes, V.; Payne, J.R.; Wess, G.; Hogan, D.F.; Abbott, J.A.; Häggström, J.; Culshaw, G.; Fine-Ferreira, D.; Cote, E.; Trehiou-Sechi, E.; Motsinger-Reif, A.A.; Nakamura, R.K.; Singh, M.; Ware, W.A.; Riesen, S.C.; Borgarelli, M.; Rush, J.E.; Vollmar, A.; Lesser, M.B.; Van Israel, N.; Lee, P.M.; Bulmer, B.; Santilli, R.; Bossbaly, M.J.; Quick, N.; Bussadori, C.; Bright, J.; Estrada, A.H.; Ohad, D.G.; Del Palacio, M.J.F.; Brayley, J.L.; Schwartz, D.S.; Gordon, S.G.; Jung, S.; Bove, C.M.; Brambilla, P.G.; Moïse, N.S.; Stauthammer, C.D.; Stepien, R.L.; Quintavalla, C.; Amberger, C.; Manczur, F.; Hung, Y.W.; Lobetti, R.; De Swarte, M.; Tamborini, A.; Mooney, C.T.; Oyama, M.A.; Komolov, A.; Fujii, Y.; Pariaut, R.; Uechi, M.; Tachika Ohara, V.Y. International collaborative study to assess cardiovascular risk and evaluate long-term health in cats with preclinical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and apparently healthy cats: The REVEAL Study. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2018, 32, 930–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis Fuentes, V.; Abbott, J.; Chetboul, V.; Côté, E.; Fox, P.R.; Häggström, J.; Kittleson, M.D.; Schober, K.; Stern, J.A. ACVIM consensus statement guidelines for the classification, diagnosis, and management of cardiomyopathies in cats. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2020, 34, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittleson, M.D.; Côté, E. The feline cardiomyopathies 2. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2021, 23, 1028–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meurs, K.M.; Sanchez, X.; David, R.M.; Bowles, N.E.; Towbin, J.A.; Reiser, P.J.; Kittleson, J.A.; Munro, M.J.; Dryburgh, K.; Macdonald, K.A.; Kittleson, M.D. A cardiac myosin binding protein C mutation in the Maine Coon cat with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 3587–3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meurs, K.M.; Norgard, M.M.; Ederer, M.M.; Hendrix, K.P.; Kittleson, M.D. A substitution mutation in the myosin binding protein C gene in Ragdoll hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Genomics. 2007, 90, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Ortuño, C.; Sebastian-Marcos, P.; Sabater-Molina, M.; Nicolas-Rocamora, E.; Gimeno-Blanes, J.R.; Fernandez del Palacio, M.J. Genetics of feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Clin. Genet. 2020, 98, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittleson, M.D.; Côté, E. The feline cardiomyopathies 1. General concepts. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2021, 23, 1009–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukumolanan, P.; Petchdee, S. Feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: genetics, current diagnosis and management. Vet. Integr. Sci. 2020, 18, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, A.J.; Braunwald, E. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Genetics, Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Therapy. Circ. Res. 2017, 121, 749–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliot, P.; Andersson, B.; Arbustini, E.; Bilinska, Z.; Cecchi, F.; Charron, P.; Dubourg, O.; Kühl, U.; Maisch, B.; McKenna, W.J.; Monserrat, L.; Pankuweit, S.; Rapezzi, C.; Seferovic, P.; Tavazzi, L.; Keren, A. Classification of the cardiomyopathies: a position statement from the European society of cardiology working group on myocardial and pericardial diseases. Eur. Heart J. 2008, 29, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersh, B.J.; Maron, B.J.; Bonow, R.O.; Dearani, J.A.; Fifer, M.A.; Link, M.S.; Naidu, S.S.; Nishimura, R.A.; Ommen, S.R.; Rakowski, H.; Seidman, C.E.; Towbin, J.A.; Udelson, J.E.; Yancy, C.W. 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2011, 124, 2761–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, C.D.N.; Caminotto, E.L.; Calahani, A.; Silveira, M.F. Sobrevida e características ecocardiográficas de gatos com e sem cardiomiopatias. R. Bras. Ci. Vet. 2020, 27, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, V.N.; Stern, J.A.; Ueda, Y. The Role of Personalized Medicine in Companion Animal Cardiology. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2023, 53, 1255–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, J.N.; Payne, J.R. Predicting Development of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and Disease Outcomes in Cats. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2023, 53, 1277–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron, B.J.; Fox, P.R. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in man and cats. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2015, 17, S6–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiatsilapanan, A.; Surachetpong, S.D. Assessment of left atrial function in feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy by using two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography. BMC Vet. Res. 2020, 16, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchini, A.; Abbott, J.A.; Lahmers, S.; Eriksson, A. Clinical characteristics of cats referred for evaluation of subclinical cardiac murmurs. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2021, 23, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argenta, F.F.; Mello, L.S.; Cony, F.G.; Pavarini, S.P.; Driemeier, D.; Sonne, L. Epidemiological and pathological aspects of cardiomiopatias in cats in southern Brazil. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2020, 40, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.R.; Borgeat, K.; Brodbelt, D.C.; Connoly, D.J.; Luis Fuentes, V. Risk factors associated with sudden death vs. congestive heart failure or arterial thromboembolism in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2015, 17, S318–S328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, J.N.; Payne, J.R.; Seo, J.; Luis Fuentes, V. Natural history of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in cats from rehoming centers: The CatScan II study. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2022, 36, 1900–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, J.N.; Payne, J.R.; Mullins, J.; Luis Fuentes, V. Isolated discrete upper septal thickening in a nonreferral cat population of senior and young cats. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2023, 50, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.; Owen, R.; Hunt, H.; Luis Fuentes, V.; Connolly, D.J.; Munday, J.S. Prevalence of cardiomyopathy and cardiac mortality in a colony of nonpurebred cats in New Zealand. N. Z. Vet. J. 2025, 73, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longeri, M.; Ferrari, P.; Knafelz, P.; Mezzelani, A.; Marabotti, A.; Milanesi, L.; Pertica, G.; Polli, M.; Brambilla, P.G.; Kittleson, M.; Lyons, L.A.; Porciello, F. Myosin-Binding Protein C DNA Variants in Domestic Cats (A31P, A74T, R820W) and their Association with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2013, 27, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.M.; Rush, J.E.; Stern, J.A.; Huggins, G.S.; Maron, M.S. Feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a spontaneous large animal model of human HCM. Cardiol. Res. 2017, 8, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, P.R.; Keene, B.W.; Lamb, K.; Schober, K.A.; Chetboul, V.; Luis Fuentes, V.; Wess, G.; Payne, J.R.; Hogan, D.F.; Motsinger-Reif, A.; Häggström, J.; Trehiou-Sechi, E.; Fine-Ferreira, D.M.; Nakamura, R.K.; Lee, P.M.; Singh, M.K.; Ware, W.A.; Abbott, J.A.; Culshaw, G.; Riesen, S.; Borgarelli, M.; Lesser, M.B.; Van Israël, N.; Côté, E.; Rush, J.E.; Bulmer, B.; Santilli, R.A.; Vollmar, A.C.; Bossbaly, M.J.; Quick, N.; Bussadori, C.; Bright, J.M.; Estrada, A.H.; Ohad, D.G.; Fernández-Del Palacio, M.J.; Lunney Brayley, J.; Schwartz, D.S.; Bové, C.M.; Gordon, S.G.; Jung, S.W.; Brambilla, P.; Moïse, N.S.; Stauthammer, C.D.; Stepien, R.L.; Quintavalla, C.; Amberger, C.; Manczur, F.; Hung, Y.W.; Lobetti, R.; De Swarte, M.; Tamborini, A.; Mooney, C.T.; Oyama, M.A.; Komolov, A.; Fujii, Y.; Pariaut, R.; Uechi, M.; Tachika Ohara, V.Y. International collaborative study to assess cardiovascular risk and evaluate long-term health in cats with preclinical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and apparently healthy cats: The REVEAL Study. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2018, 32, 930–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, R. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy-Advances in Imaging and Diagnostic Strategies. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2023, 53, 1325–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messer, A.E.; Chan, J.; Daley, A.; Copeland, O.; Marston, S.B.; Connoly, D.J. Investigations into the Sarcomeric Protein and Ca2+-Regulation Abnormalities Underlying Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in Cats (Felix catus). Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, J.A.; Ueda, Y. Inherited cardiomyopathies in veterinary medicine. Pflug. Arch. 2019, 471, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetboul, V.; Petit, A.; Gouni, V.; Trehiou-Sechi, E.; Misbach, C.; Balouka, D.; Sampedrano, C.C.; Pouchelon, J.-L.; Tissier, R.; Abitbol, M. Prospective echocardiographic and tissue Doppler screening of a large Sphynx cat population: reference ranges, heart disease prevalence and genetic aspects. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2012, 14, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgeat, K. , Stern, J., Meurs, K.M., Fuentes, V.L., Connolly, D.J. The influence of clinical and genetic factors on left ventricular wall thickness in ragdoll cats. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2015, 17, S258–S267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittleson, M.D.; Meurs, K.M.; Harris, S.P. The genetic basis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in cats and humans. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2015, 17, S53–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brizard, D.; Amberger, C.; Hartnack, S.; Doherr, M.G.; Lombard, C. Phenotypes and echocardiographic characteristics of a European population of domestic shorthair cats with idiopathic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Schweiz Arch. Tierheilkd. 2009, 151, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis Fuentes, V.; Wilkie, L.J. Asymptomatic Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Diagnosis and Therapy. Vet. Clin. Small. Anim. 2017, 47, 1041–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilley, L.P.; Liu, S.K.; Gilbertson, S.R.; Wagner, B.M.; Lord, P.F. Primary myocardial disease in the cat: A model for human cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Pathol. 1977, 86, 493–522. [Google Scholar]

- Kittleson, M.D.; Meurs, K.M.; Munro, M.J.; Kittleson, J.A.; Liu, S.K.; Pion, P.D.; Towbin, J.A. Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Maine coon cats: an animal model of human disease. Circulation. 1999, 99, 3172–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, J.A.; Rivas, V.N.; Kaplan, J.L.; Ueda, Y.; Oldach, M.S.; Ontiveros, E.S.; Kooiker, K.B.; van Dijk, S.J.; Harris, S.P. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in purpose-bred cats with the A31P mutation in cardiac myosin binding protein-C. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Donnell, K.; Adin, D.; Atkins, C.E.; DeFrancesco, T.; Keene, B.W.; Tou, S.; Meurs, K.M. Absence of known feline MYH7 and MYBPC3 variants in a diverse cohort of cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Anim. Genet. 2021, 52, 542–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontiveros, E.S.; Ueda, Y.; Harris, S.P.; Stern, J.A. Precision medicine validation: identifying the MYBPC3 A31P variant with whole-genome sequencing in two Maine Coon cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2019, 21, 1086–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukumolanan, P.; Demeekul, K.; Petchdee, S. Development of a Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Assay Coupled with a Lateral Flow Dipstick Test for Detection of Myosin Binding Protein C3 A31P Mutation in Maine Coon Cats. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 819694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgeat, K.; Casamian-Sorrosal, D.; Helps, C.; Luis Fuentes, V.; Connolly, D.J. Association of the myosin binding protein C3 mutation (MYBPC3 R820W) with cardiac death in a survey of 236 ragdoll cats. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2014, 16, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meurs, K.M.; Williams, B.G.; DeProspero, D.; Friedenberg, S.G.; Malarkey, D.E.; Ezzell, J.A.; Ezzell, J.A.; Keene, B.W.; Adin, D.B.; DeFrancesco, T.C.; Tou, S. A deleterious mutation in the ALMS1 gene in a naturally occurring model of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the Sphynx cat. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turba, M.E.; Ferrari, P.; Milanesi, R.; Gentilini, R.; Longeri, M. HCM-associated ALMS1 variant: Allele drop-out and frequency in Italian Sphynx cats. Anim. Genet. 2023, 54, 643–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, N.; Suzuki, R.; Saito, T.; Yuchi, Y.; Ukawa, H.; Matsumoto, Y. Presence of known feline ALMS1 and MYBPC3 variants in a diverse cohort of cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Japan. PLoS ONE. 2023, 18, e0283433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Loh, Y.; Connolly, D.J.; Luis Fuentes, V.; Dutton, E.; Hunt, H.; Munday, J.S. Prevalence of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and ALMS1 Variant in Sphynx Cats in New Zealand. Animals (Basel). 2024, 14, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeekul, K.; Sukumolanan, P.; Panprom, C.; Thaisakun, S.; Roytrakul, S.; Petchdee, S. Echocardiography and MALDI-TOF Identification of Myosin-Binding Protein C3 A74T Gene Mutations Involved Healthy and Mutated Bengal Cats. Animals (Basel). 2022, 12, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukumolanan, P.; Petchdee, S. Prevalence of cardiac myosin-binding protein C3 mutations in Maine Coon cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Vet. World. 2022, 15, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, T.; Ohlsson, Å.; Longeri, M.; Hayward, J.J.; Mouttham, L.; Ferrari, P.; Smets, P.; Ljungvall, I.; Häggström, J.; Stern, J.A.; Lyons, L.A.; Peelman, L.J.; Broeckx, B.J.G. The TNNT2:c.95-108G>A variant is common in Maine Coons and shows no association with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Anim. Genet. 2022, 53, 526–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzeczka, A.; Graczyk, S.; Pasławski, R.; Pasławska, U. Genetic Basis of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in Cats. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 8752–8766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciagrà, R. Positron-emission tomography myocardial blood flow quantification in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Q. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2016, 60, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Patata, V.; Caivano, D.; Porciello, F.; Rishniw, M.; Domenech, O.; Marchesotti, F.; Marchesotti, F.; Giorgi, M.E.; Guglielmini, C.; Poser, H.; Spina, F.; Birettoni, F. Pulmonary vein to pulmonary artery ratio in healthy and cardiomyopathic cats. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2020, 27, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schober, K.E.; Savino, S.I.; Yildiz, V. Right ventricular involvement in feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2016, 18, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, L.C.; Sloan, C.Q.; Stern, J.A. Echocardiographic assessment of right ventricular size and function in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2017, 31, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häggström, J.; Fuentes, L.V.; Wess, G. Screening for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in cats. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2015, 17, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parato, V.M.; Antoncecchi, V.; Sozzi, F.; Marazia, S.; Zito, A.; Maiello, M.; Palmiero, P.; ISCU. Echocardiographic diagnosis of the different phenotypes of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound. 2016, 14, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshua, J.; Caswell, J.; O'Sullivan, M.L.; Wood, G.; Fonfara, S. Feline myocardial transcriptome in health and in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-A translational animal model for human disease. PLoS One. 2023, 18, e0283244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colpitts, M.E.; Caswell, J.L.; Monteith, G.; Joshua, J.; O'Sullivan, M.L.; Raheb, S.; Fonfara, S. Cardiac gene activation varies between young and adult cats and in the presence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Res. Vet. Sci. 2022, 152, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.M.M.; Fonfara, S.; Hetzel, U.; Kipar, A. Feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: reduced microvascular density and involvement of CD34+ interstitial cells. Vet. Pathol. 2022, 59, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lean, F.Z.X.; Priestnall, S.L.; Vitores, A.G.; Suárez-Bonnet, A.; Brookes, S.M.; Núñez, A. Elevated angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expression in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Res. Vet. Sci. 2022, 152, 564–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.L.; Lisciandro, G.R.; Ware, W.A.; Viall, A.K.; Aona, B.D.; Kurtz, K.A.; Reina-Doreste, Y.; DeFrancesco, T.C. Evaluation of point-of-care thoracic ultrasound and NT-proBNP for the diagnosis of congestive heart failure in cats with respiratory distress. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2018, 32, 1530–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follby, A.; Pettersson, A.; Ljungvall, I.; Ohlsson, Å.; Häggström, J. A Questionnaire Survey on Long-Term Outcomes in Cats Breed-Screened for Feline Cardiomyopathy. Animals (Basel). 2022, 12, 2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Boedec, K.; Arnaud, C.; Chetboul, V.; Trehiou-Sechi, E.; Pouchelon, J.L.; Gouni, V.; Reynolds, B.S. Relationship between paradoxical breathing and pleural diseases in dyspneic dogs and cats: 389 cases (2001-2009). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2012, 240, 1095–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson, D.; Little, C.J.L.; Harris, J.; Rishniw, M. Rapid assessment with physical examination in dyspnoeic cats: the RAPID CAT study. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2018, 59, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugada-Terradellas, C.; Hellemans, A.; Brugada, P.; Smets, P. Sudden cardiac death: A comparative review of humans, dogs and cats. Vet. J. 2021, 274, 105696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saponaro, V.; Mey, C.; Vonfeld, I.; Chamagne, A.; Alvarado, M.-P.; Cadoré, J.-L.; Chetboul, V.; Desquilbet, L. Systolic third sound associated with systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve in cats with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2023, 37, 1679–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paige, C.F.; Abbott, J.A.; Elvinger, F.; Pyle, R.L. Prevalence of cardiomyopathy in apparently healthy cats. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2009, 234, 1398–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Luis Fuentes, V.; Payne, J.R.; McDermott, N.; Brodbelt, D. Comparison of auscultatory and echocardiographic findings in healthy adult cats. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2010, 12, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, A. Cardiomiopatias em felinos. In Tratado de Cardiologia de Cães e Gatos, 1st ed.; Larsson, M.H.M.A., Ed. Interbook: São Paulo, Brazil, 2020: Volume 1, pp.

- Nonn, T.; Adisaisakundet, I.; Chairit, K.; Choksomngam, S.; Hunprasit, V.; Jeamsripong, S.; Surachetpong, S.D. Parameters related to diagnosing hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in cats. Open Vet. J. 2024, 14, 2407–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vliegenthart, T.; Szatmári, V. A New, Easy-to-Learn, Fear-Free Method to Stop Purring During Cardiac Auscultation in Cats. Animals (Basel). 2025, 15, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaverdian, M.; Li, R.H.L. Preventing Cardiogenic Thromboembolism in Cats Literature Gaps, Rational Recommendations, and Future Therapies. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2023, 53, 1309–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaverdian, M.; Nguyen, N.; Li, R.H.L. A novel technique to characterize procoagulant platelet formation and evaluate platelet procoagulant tendency in cats by flow cytometry. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1480756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poredos, P.; Jezovnik, M.K. Endothelial Dysfunction and Venous Thrombosis. Angiology 2017, 69, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, D.F. Feline Cardiogenic Arterial Thromboembolism Prevention and Therapy. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. 2017, 47, 1065–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, J.K.; Kellett, J.G.; Jensen, N.H.; Hansen, S.N.; Jensen, K.; Brabrand, M. Prognostic value of infrared thermography in an emergency department. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 25, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavelková, E. Feline arterial thromboembolism. Companion animal, 2019, 24, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis Fuentes, V. Arterial thromboembolism Risks, realities and a rational first-line approach. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2012, 14, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogan, D.F.; Fox, P.R.; Jacob, K.; Keene, B.; Laste, N.J.; Rosenthal, S.; Sederquist, K.; Weng, H.-Y. Secondary prevention of cardiogenic arterial thromboembolism in the cat: the double-blind, randomized, positive-controlled feline arterial thromboembolism; clopidogrel vs. aspirin trial (FAT CAT). J. Vet. Cardiol. 2015, 17, S306–S317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, G.C.; Veronezi, T.M.; Luz, C.G.; Gutierrez, L.G.; Scherer, S.; Pavarini, S.P.; Costa, F.V.A. Arterial thromboembolism of noncardiogenic origin in a domestic feline with ischemia and reperfusion syndrome. Semin. Cienc. Agrar. 2020, 41, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.M.; Caramalac, S.M.; Caramalac, S.M.; Gimelli, A.; Palumbo, M.I.P. Feline Aortic Thromboembolism Diagnosed by Thermography. Acta Vet. Sci. 2022, 50, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrold, E.; Schober, K.; Miller, J.; Jennings, R. Systemic reactive angioendotheliomatosis mimicking hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a domestic shorthair cat. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2024, 56, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janus, I.; Noszczyk-Nowak, A.; Bubak, J.; Tursi, M.; Vercelli, C.; Nowak, M. Comparative cardiac macroscopic and microscopic study in cats with hyperthyroidism vs. cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Vet. Q. 2023, 43, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Lee, D.; Park, J.; Yun, T.; Koo, Y.; Chae, Y.; Kang, B.-T.; Yang, M.-P.; Kim, H. Heart failure in a cat due to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy phenotype caused by chronic uncontrolled hyperthyroidism. Acta Vet. Hung. 2023, 71, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, S.; Levy, J.; Hartmann, K.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Hosie, M.; Olah, G.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Hosie, M.; Olah, G.; Denis, K.S. 2020 AAFP Feline Retrovirus Testing and Management Guidelines. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2020, 22, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavazza, A.; Marchegiani, A.; Guerriero, L.; Turinelli, V.; Spaterna, A.; Mangiaterra, S.; Galosi, L.; Rossi, G.; Cerquetella, M. Updates on Laboratory Evaluation of Feline Cardiac Diseases. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, R.C.; Kadotani, S.; Stack, J.P.; Kruckman, L.; Wallace, G. Prognostic Value of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Cats with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 813524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, I.; Summers, S.; Rishniw, M.; Quimby, J. Cross-sectional survey of noninvasive indirect blood pressure measurement practices in cats by veterinarians. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2022, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oura, T.J.; Young, A.N.; Keene, B.W.; Robertson, I.D.; Jennings, D.E.; Thrall, D.E. A Valentine-Shaped Cardiac Silhouette in Feline Thoracic Radiographs is Primarily due to Left Atrial Enlargement. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound. 2015, 56, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmini, C.; Diana, A. Thoracic radiography in the cat: Identification of cardiomegaly and congestive heart failure. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2015, 17, S87–S101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côtè, E. Feline Congestive Heart Failure Current Diagnosis and Management. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. 2017, 47, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.R.; Borgeat, K.; Connoly, D.J.; Boswood, A.; Dennis, S.; Wagner, T.; Menaut, P.; Maerz, I.; Evans, D.; Simons, V.E.; Brodbelt, D.C.; Luis Fuentes, V. Prognostic Indicators in Cats with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2013, 27, 1427–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Lee, D.; Park, S.; Suh, G.H.; Choi, J. Radiographic findings of cardiopulmonary structures can predict hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure in cats. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2023, 84, ajvr.23–01.0017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rho, J.; Shin, S.-M.; Jhang, K.; Lee, G.; Song, K.-H.; Shin, H. Deep learning-based diagnosis of feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. PLoS One. 2023, 18, e0280438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, K.E.; Zientek, J.; Li, X.; Luis Fuentes, V.; Bonagura, J.D. Effect of treatment with atenolol on 5-year survival in cats with preclinical (asymptomatic) hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2013, 15, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, M.D.; Giglio, R.F.; Berry, C.R.; Reese, D.J.; Maisenbacher, H.W.; Hernandez, J.A. Associations between 'valentine' heart shape, atrial enlargement and cardiomyopathy in cats. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2014, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diana, A.; Perfetti, S.; Valente, C.; Toaldo, M.B.; Pey, P.; Cipone, M.; Poser, H.; Guglielmini, C. Radiographic features of cardiogenic pulmonary edema in cats with left-sided cardiac disease: 71 cases. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2022, 24, e568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litster, A.L.; Buchanan, W. Vertebral scale system to measure heart size in radiographs of cats. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2000, 216, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, B.L.; Lehmkuhl, L.B.; Adin, D.B. Heart rate and arrhythmia frequency of normal cats compared to cats with asymptomatic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2014, 16, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.S.; Pinto, A.C.B.C.F.; Itikawa, P.H.; Júnior, F.F.L.; Goldfeder, G.T.; Larsson, M.H.M.A. Radiographic evaluation of cardiac silhouette in healthy Maine Coon cats. Semin: Ciênc. Agrar. 2014, 35, 2501–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanås, S.; Tidholm, A.; Holst, B.S. Ambulatory electrocardiogram recordings in cats with primary asymptomatic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2015, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romito, G.; Gugliemini, C.; Mazzarella, M.O.; Cipone, M.; Diana, A.; Contiero, B.; Baron Toaldo, M. Diagnostic and prognostic utility of surface electrocardiography in cats with left ventricular hypertrophy. J Vet Cardiol 2018, 20, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidler, M.; Santarelli, G.; Kovacevic, A.; Matos, J.N.; Schreiber, N.; Toaldo, N.B. Ventricular preexcitation in cats: 17 cases. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2023, 47, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, L.A.; Nakamura, R.K. Pre-excitation alternans in a cat. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2025, 58, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, R.F.; Tuleski, G.L.R.; Franco, L.F.C.; Sousa, M.G. Tpeak-Tend, a novel electrocardiographic marker in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-a brief communication. Vet. Res. Commun. 2023, 47, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Kurosawa, T.A.; Borgeat, K.; Novo Matos, J.; Hutchinson, J.C.; Arthurs, O.J.; Fuentes, V.L. Clinical signs associated with severe ST segment elevation in three cats with a hypertrophic cardiomyopathy phenotype. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2024, 54, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, R.F.; Tuleski, G.L.R.; Sousa, M.G. QT interval instability and QRS interval dispersion in healthy cats and cats with a hypertrophic cardiomyopathy phenotype. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2023, 25, 1098612X231151479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oricco, S.; Quintavalla, C.; Apolloni, I.; Crosara, S. Bradyarrhythmia after treatment with atenolol and mirtazapine in a cat with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2024, 53, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cofaru, A.; Murariu, R.; Popa, T.; Peștean, C.P.; Scurtu, I.C. The Unseen Side of Feline Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Diagnostic and Prognostic Utility of Electrocardiography and Holter Monitoring. Animals (Basel). 2024, 14, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartoszuk U; Keene BW; Baron Toaldo M; Pereira N; Summerfield N; Novo Matos J; Glaus, T. M. Holter monitoring demonstrates that ventricular arrhythmias are common in cats with decompensated and compensated hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Vet. J. 2019, 243, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, Y.C.; Rush, J.E.; Cunningham, S.M.; Bulmer, B.J.; Freeman, L.M.; Rozanski, E.A. Evaluation of a training course in focused echocardiography for noncardiology house officers. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care. 2013, 23, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, J.A.; MacLean, H.N. Two-Dimensional Echocardiographic Assessment of the Feline Left Atrium. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2006, 20, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chetboul, V.; Passavin, P.; Trehiou-Sechi, E.; Gouni, V.; Poissinnier, C.; Pouchelon, J.-L.; Desquilbet, L. Clinical, epidemiological and echocardiographic features and prognostic factors in cats with restrictive cardiomyopathy: A retrospective study of 92 cases (2001-2015). J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2019, 33, 1222–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maerz, I.; Schober, K.; Oechtering, G. Echocardiographic measurement of left atrial dimension in healthy cats and cats with left ventricular hypertrophy. Tieraerztl. Prax. Ausg. K. Kleintiere. Heimtiere. 2006, 34, 331. [Google Scholar]

- Schober, K.E.; Maerz, I. Assessment of left atrial appendage flow velocity and its relation to spontaneous echocardiographic contrast in 89 cats with myocardial disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2006, 20, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, J.N.; Sargent, J.; Silva, J.; Payne, J.R.; Seo, J.; Spalla, I. Thin and hypokinetic myocardial segments in cats with cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2023, 46, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colakoglu, E.; Sevim, K.; Kaya, U. Short communication Assessment of left atrial size, left atrial volume and left ventricular function, and its relation to spontaneous echocardiographic contrast in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A preliminary study. Pol. J. Vet. Sci, 2024, 27, 487–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.; Novo Matos, J.; Munday, J.S.; Hunt, H.; Connolly, D.J.; Luis Fuentes, V. Longitudinal assessment of systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2024, 38, 2982–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.; Matos, J.M.; Payne, J.R.; Luis Fuentes, V.; Connolly, D.J. Anterior mitral valve leaflet length in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2021, 37, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velzen, H.G.; Schinkel, A.F.L.; Menting, M.E.; Bosch, A.E.V.D.; Michels, M. Prognostic significance of anterior mitral valve leaflet length in individuals with a hypertrophic cardiomyopathy gene mutation without hypertrophic changes. J. Ultrasound. 2018, 21, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalla, I.; Payne, J.R.; Borgeat, K.; Pope, A.; Luis Fuentes, V.; Connoly, D.J. Mitral Annular Plane Systolic Excursion and Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion in Cats with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2017, 31, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, K.E.; Chetboul, V. Echocardiographic evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function in cats: Hemodynamic determinants and pattern recognition. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2015, 17, S102–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutton, L.C.; Spalla, I.; Seo, J.; Silva, J.; Matos, J.N. Aortic annular plane systolic excursion in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2024, 38, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, M.B.T.; Grevsen, J.R.; Kiely, M.A.B.; Willesen, J.L.; Koch, J. Detection of congestive heart failure by mitral annular displacement in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy - concordance between tissue Doppler imaging-derived tissue tracking and M-mode. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2021, 36, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crosara, S.; Allodi, G.; Guazzetti, S.; Oricco, S.; Borgarelli, M.; Corsini, A.; Quintavalla, C. Aorto-septal angle, isolated basal septal hypertrophy, and systolic murmur in 122 cats. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2023, 46, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalla, I.; Boswood, A.; Connolly, D.J.; Luis Fuentes, V. Speckle tracking echocardiography in cats with preclinical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2019, 33, 1232–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Suzuki, R.; Yuchi, Y.; Fukuoka, H.; Satomi, S.; Teshima, T.; Matsumoto, H. Comparative study of myocardial function in cases of feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with and without dynamic left-ventricular outflow-tract obstruction. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1191211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, M.; Watanabe, M.; Takeuchi, A.; Yokoi, A.; Terai, K.; Matsuura, K.; Takahashi, K.; Tanaka, R. Differences in the Impact of Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Obstruction on Intraventricular Pressure Gradient in Feline Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Animals (Basel). 2024, 14, 3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, R.; Saito, T.; Yuchi, Y.; Kanno, H.; Teshima, T.; Matsumoto, H. Detection of Congestive Heart Failure and Myocardial Dysfunction in Cats With Cardiomyopathy by Using Two-Dimensional Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 771244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, R.; Vasan, R.S. Biomarkers in Cardiovascular Disease: Statistical Assessment and Section on Key Novel Heart Failure Biomarkers. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2017, 27, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machen, M.C.; Oyama, M.A.; Gordon, S.G.; Rush, J.E.; Achen, S.E.; Stepien, R.L.; Fox, P.F.; Saunders, A.B.; Cunningham, S.M.; Lee, P.M.; Kellihan, H.B. Multicentered investigation of a point-of-care NT-proBNP ELISA to detect moderate to severe occult (preclinical) feline heart disease in cats referred for cardiac evaluation. J. Ve.t Cardiol. 2014, 16, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heishima, Y.; Hori, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Yamashita, Y.; Isayama, N.; Kanno, N.; Katagi, M.; Onodera, H.; Yamano, S.; Aramaki, Y. Diagnostic accuracy of plasma atrial natriuretic peptide concentrations in cats with and without cardiomyopathies. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2018, 20, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.F.; Quinn, R.L.; Rahilly, L.J. Biomarkers for differentiation of causes of respiratory distress in dogs and cats: Part 1-cardiac diseases and pulmonary hypertension. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care. 2015, 25, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.-L.; Côté, E.; Kuo, Y.-W.; Wu, H.-H.; Wang, W.-Y.; Hung, Y.-H. Point-of-care N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide assay to screen apparently healthy cats for cardiac disease in general practice. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2021, 35, 1663–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainville, C.A.; Clark, G.H.; Esty, K.J.; Foster, W.M.; Hanscom, J.; Hebert, K.J.; Lyons, H.R. Analytical validation of an immunoassay for the quantification of N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide in feline blood. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2015, 27, 414–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parzeniecka-Jaworska, M.; Garncarz, M.; Kluciński, W. ProANP as a screening biomarker for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Maine coon cats. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2016, 19, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ironside, V.A.; Tricklebank, P.R.; Boswood, A. Risk indictors in cats with preclinical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a prospective cohort study. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2021, 23, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, Y.; Iguchi, M.; Heishima, Y.; Yamashita, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Hirakawa, A.; Kitade, A.; Ibaragi, T.; Katagi, M.; Sawada, T.; Yuki, M.; Kanno, N.; Inaba, H.; Isayama, N.; Onodera, H.; Iwasa, N.; Kino, M.; Narukawa, M.; Uchida, S. Diagnostic utility of cardiac troponin I in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2018, 32, 922–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanås, S.; Larsson, A.; Rydén, J.; Lilliehöök, I.; Häggström, J.; Tidholm, A.; Höglund, K.; Ljungvall, I.; Holst, B.S. Cardiac troponin I in healthy Norwegian Forest Cat, Birman and domestic shorthair cats, and in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2022, 24, e370–e379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.; Payne, J.R.; Matos, J.N.; Fong, W.W.; Connolly, D.J.; Fuentes, V.L. Biomarker changes with systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Int. Med. 2020, 34, 1718–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prošek, R.; Sisson, D.; Oyama, M.A.; Biondo, A.W.; Solter, P.F. Measurements of Plasma Endothelin Immunoreactivity in Healthy Cats and Cats with Cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2004, 18, 826–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiwaganont, P.; Roytrakul, S.; Thaisakun, S.; Sukumolanan, P.; Petchdee, S. Investigation of coagulation and proteomics profiles in symptomatic feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and healthy control cats. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsiglia, J.D.C.; Credidio, F.L.; Mimary de Oliveira, T.G.; Reis, R.F.; Antunes, M.O.; de Araujo, A.Q.; Pedrosa, R.P.; Barbosa-Ferreira, J.M.B.; Mady, C.; Krieger, J.E.; Arteaga-Fernandez, E.; Pereira, A.C. Clinical predictors of a positive genetic test in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the Brazilian population. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 2014, 14, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casamian-Sorrosal, D.; Chong, S.K.; Fonfara, S.; Helps, C. Prevalence and demographics of the MYBPC3-mutations in ragdolls and Maine coons in the British Isles. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2014, 55, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.-C.; Lawson, C.; Liu, H.-H.; Wilkie, L.; Dobromylskyj, M.; Luis Fuentes, V.; Dudhia, J.; Connolly, D.J. Exploration of mediators associated with myocardial remodelling in feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Animals (Basel) 2023, 13, 2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.L.; Rivas, V.N.; Connolly, D.J. Advancing treatments for feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the role of animal models and targeted therapeutics. Vet. Clin. North. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2023, 53, 1293–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, J.P.; Fries, R.C.; Kruckman, L.; Kadotani, S.; Wallace, G. Galectin-3 as a novel biomarker in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Cardiol, 2023, 48, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fries, R.C.; Kadotani, S.; Keating, S.C.J.; Stack, J.P. Cardiac extracellular volume fraction in cats with preclinical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2021, 35, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeekul, K.; Sukumolanan, P.; Petchdee, S. Evaluation of galectin-3 and titin in cats with a sarcomeric gene mutation associated with echocardiography. Vet. World. 2024, 17, 2407–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, A.; Joshua, J.; Raheb, S.; Pires, A.; Colpitts, M.; Caswell, J.L.; Fonfara, S. Evaluation of potential novel biomarkers for feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Res. Vet. Sci. 2024, 180, 105430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.H.L.; Nguyen, N.; Stern, J.A.; Duler, L.M. Neutrophil extracellular traps in feline cardiogenic arterial thrombi: a pilot study. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2022, 24, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.H.L.; Fabella, A.; Nguyen, N.; Kaplan, J.L.; Ontiveros, E.; Stern, J.A. Circulating neutrophil extracellular traps in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and cardiogenic arterial thromboembolism. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2023, 37, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodan, I.; Sundahl, E.; Carney, H.; Gagnon, A.-C.; Heath, S.; Landsberg, G.; Seksel, K.; Yin, S.; Association, A.A.H. AAFP and ISFM Feline-Friendly Handling Guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2011, 13, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keene, B.W.; Atkins, C.E.; Bonagura, J.D.; Fox, P.R.; Häggström, J.; Luis Fuentes, V.; Oyama, M.A.; Rush, J.E.; Stepien, R.; Uechi, M. ACVIM consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2019, 33, 1127–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamp, A.L.; Yousofzai, W.; Kooistra, H.S.; Santarelli, G.; van Geijlswijk, I.M. Suspected clopidogrel-associated hepatitis in a cat. J.F.M.S. Open Rep. 2024, 10, 20551169241278408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, B.L.; Adin, D.B.; Lehmkuhl, L.B. Effect of atenolol on heart rate, arrhythmias, blood pressure, and dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in cats with subclinical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2015, 17, S296–S305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortas, M; Szatmári, V. Prevalence and prognosis of atenolol-responsive systolic anterior motion of the septal mitral valve leaflet in young cats with severe dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Animals (Basel). 2022, 12, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.N.; Martin, M.; Chetboul, V.; Ferasin, L.; French, A.T.; Strehlau, G.; Seewald, W.; Smith, S.G.W.; Swift, S.T.; Roberts, S.L.; Harvey, A.M.; Little, C.J.L.; Caney, S.M.A.; Simpson, K.E.; Sparkes, A.H.; Mardell, E.J.; Bomassi, E.; Muller, C.; Sauvage, J.P.; Diquélou, A.; Schneider, M.A.; Brown, L.J.; Clarke, D.D.; Rousselot, J.-F. Evaluation of benazepril in cats with heart disease in a prospective, randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2019, 33, 2559–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, K.A.; Kittleson, M.D.; Kass, P.; White, S.D. Effect of spironolactone on diastolic function and left ventricular mass in Maine Coon cats with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2008, 22, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reina-Doreste, Y.; Stern, J.A.; Keene, B.W.; Tou, S.P.; Atkins, C.E.; DeFrancesco, T.C.; Ames, M.K.; Hodge, T.E.; Meurs, K.M. Case-control study of the effects of pimobendan on survival time in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2014, 245, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaka, M.; Katagiri, K.; Ogawa, M.; Hsu, H.H.; Miyagawa, Y.; Takemura, N. A pilot study of the proarrhythmic effects of pimobendan injection in clinically healthy cats. Vet. Res. Commun. 2024, 48, 3177–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldach, M.S.; Ueda, Y.; Ontiveros, E.S.; Fousse, S.L.; Visser, L.C.; Stern, J.A. Acute pharmacodynamic effects of pimobendan in client-owned cats with subclinical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochie, S.L.; Schober, K.E.; Rhinehart, J.; Winter, R.L.; Bonagura, J.D.; Showers, A.; Yildez, V. Effects of pimobendan on left atrial transport function in cats. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2021, 35, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schober, K.E.; Rush, J.E.; Luis Fuentes, V.; Glaus, T.; Summerfield, N.J.; Wright, K.; Lehmkuhl, L.; Wess, G.; Sayer, M.P.; Loureiro, J.; MacGregor, J.; Mohren, N. Effects of pimobendan in cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and recent congestive heart failure: results of a prospective, double-blind, randomized, nonpivotal, exploratory field study. J. Vet. Intern Med. 2021, 35, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, R.; Guillot, E.; Garelli-Paar, C.; Huxley, J.; Grassi, V.; Cobb, M. The SEISICAT study: a pilot study assessing efficacy and safety of spironolactone in cats with congestive heart failure secondary to cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2017, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrook, L.E.; Bennett, P.F. Effect of pimobendan on the clinical outcome and survival of cats with nontaurine responsive dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2012, 14, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche-Catholy, M.; Paepe, D.; Devreese, M.; Broeckx, B.J.G.; Woehrlé, F.; Schneider, M.; Garcia de Salazar Alcala, A.; Hellemans, A.; Smets, P. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of orally administered torasemide in healthy cats. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2022, 36, 1782–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pion, P.D.; Kittleson, M.D.; Rogers, Q.R.; Morris, J.G. Myocardial failure in cats associated with low plasma taurine: a reversible cardiomyopathy. Science. 1987, 14, 764–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umezawa, M.; Aoki, T.; Niimi, S.; Takano, H.; Mamada, K.; Fujii, Y. A pilot study investigating serum carnitine profile of cats with preclinical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2025, 87, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.E.; Morris, N.; Dhupa, N.; Murtaugh, R.J.; Rush, J.E. Retrospective study of streptokinase administration in 46 cats with arterial thromboembolism. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2000, 10, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, K.M.; Rozanski, E.A.; Freeman, L.M.; Rush, J.E. Prospective evaluation of tissue plasminogen activator in 11 cats with arterial thromboembolism. J Feline Med Surg 2010, 12, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaumin, J.; Gibson, R.M.B.; Goy-Thollot, I.; Bonagura, J.D. Thrombolysis with tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) in feline acute aortic thromboembolism: a retrospective study of 16 cases. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2018, 21, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, S.T.; Walker, A.L.; Georges, C.J.; Li, R.H.L.; Stern, J.A. Dual therapy with clopidogrel and rivaroxaban in cats with thromboembolic disease. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2022, 24, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.T.; Li, R.H.L.; Georges, C.J.; Nguyen, N.; Chen, C.K.; Stuhlmann, C.; Oldach, M.S.; Rivas, V.N.; Fousse, S.; Harris, S.P.; Stern, J.A. Synergistic inhibitory effects of clopidogrel and rivaroxaban on platelet function and platelet-dependent thrombin generation in cats. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2023, 37, 1390–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaturanratsamee, K.; Jiwaganont, P.; Panprom, C.; Petchdee, S. Rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin plus clopidogrel therapy for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-associated thromboembolism in cats. Vet. World 2024, 17, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rishniw, M. How much protection does clopidogrel provide to cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy? J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2024, 262, 1422–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, A.N.; Oldach, M.S.; Kaplan, J.L.; Rivas, V.; Kovacs, S.L.; Hwee, D.T.; Morgan, B.P.; Malik, F.I.; Harris, S.P.; Stern, J.A. Pharmacokinetics of a single dose of Aficamten (CK-274) on cardiac contractility in an A31P MYBPC3 hypertrophic cardiomyopathy cat model. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Therap. 2023, 46, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, A.N.; Oldach, M.S.; Rivas, V.N.; Kaplan, J.L.; Walker, A.L.; Kovacs, S.L.; Hwee, D.T.; Cremin, P.; Morgan, B.P.; Malik, F.I.; Harris, S.P.; Stern, J.A. Effects of Aficamten on cardiac contractility in a feline translational model of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.L.; Rivas, V.N.; Walker, A.L.; Grubb, L.; Farrell, A.; Fitzgerald, S.; Kennedy, S.; Jauregui, C.E.; Crofton, A.E.; McLaughlin, C.; Van Zile, R.; DeFrancesco, T.C.; Meurs, K.M.; Stern, J.A. Delayed-release rapamycin halts progression of left ventricular hypertrophy in subclinical feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: results of the RAPACAT trial. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2023, 261, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, V.N.; Crofton, E.A.; Jauregui, C.E.; Wouters, J.R.; Yang, B.S.; Wittenburg, L.A.; Kaplan, J.L.; Hwee, D.T.; Murphy, A.N.; Morgan, B.P.; Malik, F.I.; Harris, S.P.; Stern, J.A. Cardiac myosin inhibitor, CK-586, minimally reduces systolic function and ameliorates obstruction in feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).