1. Introduction

Whenever a nation or territory cannot raise enough money from its citizens to support its economic expansion, it turns to outside lenders and investors. This external finance often consists of both state and private funding. In contrast to private financing, public financing has favorable terms. It is provided through grants or privileged lending with extended payback terms and lower interest charges than those on global personal capital markets (Amoa, 2020). This is made possible by Official Development Assistance (ODA), also referred to as Foreign Development Aid, which is federal funding that primarily supports and fosters the prosperity and well-being of underdeveloped nations (Ono & Sekiyama, 2024). ODA differs from other monetary resource transfers from industrialized to underdeveloped nations primarily due to two factors. First, ODA is given to developing nations in two ways: directly and indirectly through multilateral institutions at the choice of the governing bodies of industrialized nations. These bodies are driven by their desires and objectives rather than market outcomes (Cassola et al., 2022). Secondly, ODA is offered on extremely lenient conditions; about 90% are donations, and if loans are issued, they are offered at modest interest rates for extended periods (Sengupta, 2002). Due to these qualities, ODA remains more appealing to less developed nations, making it superior to other forms of outside funding.

The relationship between ODA and EG is complicated. Theoretically, ODA could positively or negatively affect EG depending on the quality of governance, institutional capacity, and the broader economic environment in the recipient nation. According to the two-gap model, proposed by Chenery and Strout (1966), developing countries face two primary gaps: the savings-investment gap and the foreign exchange gap. Therefore, ODA can stimulate EG by bridging these gaps. In addition, endogenous growth theory suggests that internal elements, such as human capital, innovation, and knowledge, are crucial in promoting EG. ODA can boost EG by financing education, research and development, and technology transfer, which contribute to increasing returns to scale and sustained long-term growth. However, moral hazard theory posits that ODA can have adverse effects if governments of recipient countries change their behavior, as the aid they receive protects them from facing the full consequences of their actions. Moreover, public choice theory asserts that the effectiveness of foreign aid depends on how political leaders in recipient countries distribute aid resources. ODA may be redirected to projects that serve political interests rather than those that enhance economic efficiency.

Over the past few decades, many empirical studies have investigated the impact of ODA on economic growth (EG) in developing countries. Most studies in this field has focused on the effect of aggregate ODA on EG with mixed outcome. Specifically, many empirical studies reported a positive effect of ODA on EG (Burnside and Dollar, 2000; Gomanee et al., 2005; Refaei and Sameti, 2015; Das and Sethi, 2020; Azam and Feng, 2022; Wehncke et al., 2023, and Fazlly, 2024). However, some studies reported a negative effect of ODA on EG (Mallik, 2008; Liew et al., 2012; Zardoub and Sboui, 2023) or no impact on EG (Ekanayake and Chatrna, 2010; Siraj, 2012; Stojanov et al., 2019; Awino and Kioko, 2022). A key distinction in the discussion of ODA is between bilateral and multilateral aid, each driven by different donor motives, characteristics and conditions of aid, and donor-recipient relationships. Bilateral aid is often aligned with the donor’s economic and strategic interests, as seen in the practices of countries like Japan, the United States, and former colonial powers. In contrast, multilateral aid, provided by institutions like the World Bank (WB) and International Monetary Fund (IMF), typically includes stringent conditions such as structural adjustments. The unique technical skills, historical ties, and specific field expertise that bilateral donors possess often create a more tailored and effective aid relationship. These differences underscore the necessity of distinguishing between bilateral and multilateral aid impacts in economic analyses, as their respective influences on growth can vary significantly.

Like other developing countries, Vietnam has depended on foreign capital to augment the resources and accelerate investment from abroad. ODA may complement local savings in a way that other types of foreign transfers cannot, owing to both attributes (Sengupta, 2002). In economically disadvantaged nations like Vietnam, where banking systems are fragile; physical infrastructure is lacking; resources are stationary, and market malfunctions are widespread, ODA turns into one of the most excellent and successful strategies to promote EG. Although the effect of ODA on EG has been substantially discovered in developing countries, very little has been known about this effect on the EG of Vietnam, especially, in terms of distinguishing the effects of bilateral and multilateral ODA. Therefore, this study is devoted to filling this gap in the literature by investigating the effects of bilateral and multilateral ODA on Vietnam’s EG separately.

The contributions of the study are to broaden the literature on the impact of ODA on EG in a transitional economy. Vietnam offers a compelling case for studying due to its rapid economic transformation with high EG and the substantial aid it has received for infrastructure, social services, and policy reforms over the period of 1986-2022. In addition, while most studies have examined the aggregate effect of ODA on EG, this study focuses on the effects of bilateral and multilateral ODA on Vietnam’s EG separately. This distinction is critical, as bilateral ODA often comes with specific conditions tied to the donor country’s interests, while multilateral ODA is generally managed by international organizations with broader development objectives. Studying the separate impacts of bilateral and multilateral ODA is essential to better understand different effectiveness of these types of ODA and to provide tailored policy recommendations. Such insights are crucial for optimizing the use of ODA in Vietnam and contributing to the broader discussion on the role of ODA in economic development of developing nations. As Vietnam progresses from a low-income to a lower-middle-income country, the strategic choice and management of ODA funding will significantly impact the nation’s sustainable development path.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the literature and

Section 3 describes the data and research methodology.

Section 4 reports and discusses the empirical results. Finally,

Section 5 provides the conclusion.

2. Literature Review

Many empirical studies that investigated the impact of ODA on EG have been conducted in developing economies for the last few decades. Most empirical studies have examined the effects of aggregate ODA on EG. However, empirical findings of these studies have been mixed. Many studies documented that ODA has positive effects on EG. Burnside and Dollar (2000) is one of the earliest and most influential studies on this field. Using a dataset of 56 developing nations from 1970 to 1993, the researchers documented that foreign aid positively impacts on EG, but this impact depends on the quality of the recipient country’s economic policies. Foreign aid is more effective in stimulating EG in nations with good policies, but the effect of foreign aid on EG is negligible or even negative in countries with poor policy environments. Moreover, Gomanee et al. (2005) determined the impact of ODA on EG of 25 Sub-Saharan African countries from 1970 to 1997 and found that ODA has significantly positive impact on EG. Similarly, Eregha and Oziegbe (2016) reported that ODA had a significantly positive effect on EG for Southern Africa, Central Africa, and oil exporting countries. However, ODA had significantly positive impact on EG for West Africa only when macroeconomic policy environment variables were taken into account. Moreover, using a data of 111 developing countries from 1970 to 2010, Rahnama et al. (2017) documented that ODA has positive effects on EG in high-income developing nations. Furthermore, Azam and Feng (2022) explored how foreign aid impacted the EG of 37 developing economies from 1985 to 2018. Generally, they found a positive effect of ODA on EG. However, the influence of ODA depends on some factors, such as the types of aid and the quality of institutions within the recipient country. Besides, Wehncke et al. (2023) estimated the relationships between ODA, foreign direct investment (FDI), and EG for 20 developing countries. The researchers found that ODA has significantly positive impact on EG in both the short-term and long-term, but the long-term impact of ODA on EG are more significant than those observed in the short-term. Regarding specific countries, Feeny (2005) examined the effect of ODA on Papua New Guinea’s EG from 1965 to 1999. The empirical findings of the study confirmed that ODA has a positive effect on the EG. In addition, Refaei and Sameti (2015) explored the influence of ODA on Iran’s EG from 1980 to 2012. They reported that ODA positively impacted on EG in the long-term. Moreover, Das and Sethi (2020) investigated how various external financial inflows, including FDI, remittances, and ODA, impacted on EG of India and Sri Lanka and found that ODA had positive impact on EG for both countries. Nguyen et al. (2022) explored the impact of Japanese ODA on EG of ASEAN countries for the period from 2008 to 2020. This study documented that the ODA has a positive effect on EG of ASEAN countries. Similarly, Chansombuth (2023) investigated the relationship between Japanese ODA and EG in Laos for the period from 1990 to 2020 and concluded that the ODA has a positive effect on EG in the long-run, but it has no impact on EG in the short-run. Besides, Guo et al. (2024) examined the impact of ODA on renewable energy development in sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries. Using double machine learning approach, they found that ODA has a positive impact on the development of renewable energy in these countries. Moreover, the effectiveness of aid in promoting renewable energy is significantly enhanced when recipient countries possess strong management systems and transparent policy environments. Recently, using the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) approach with the sample from 1980 to 2021, Fazlly (2024) also reported a long-term positive effect of ODA on EG for Afghanistan. In addition, Orchi and Ahmed (2024) investigated the symmetric and asymmetric effects of ODA and remittances on EG of Bangladesh. The findings derived from the ARDL and Non-Linear ARDL (NARDL) consistently confirm that ODA has a positive effect on Bangladesh’s EG.

In contrast, some studies have provided empirical evidence of the negative effect of ODA on EG. Mallik (2008) used cointegration approach to determine the long-run relationship between ODA and the EG of the six poorest African countries. The findings of the study confirmed that ODA had a negative long-run effect on the EG of five countries, namely Central African Republic, Malawi, Mali, Niger, and Sierra Leone. Similarly, Liew et al. (2012) also found that ODA had significantly negative impact on EG for five East African countries. In addition, Driffield and Jones (2013) investigated the effects of FDI, ODA, and migrant remittances on EG in developing economies and found a negative effect of ODA on EG when the interaction terms are not considered. However, the impact of ODA on EG becomes positive when the bureaucratic quality factor is considered. Moreover, Rahnama et al. (2017) documented that ODA has the negative impact on EG in low-income developing nations. Besides, Zardoub and Sboui (2023) analyzed the effects of capital inflows, including ODA on EG of 41 developing countries from 1990 to 2016. Their findings also confirmed that ODA has a significantly negative effect on the EG. In a recent study, Moloi (2024) investigated the relationship between ODA, FDI, and EG of 30 African countries. Findings from this study also revealed that ODA is negatively associated with EG. Several studies, in particular, have found no significant effects of ODA on EG (Ekanayake and Chatrna, 2010; Siraj, 2012; Stojanov et al., 2019; Awino and Kioko, 2022).

Some empirical studies have investigated the effects of bilateral and multilateral aid on EG in developing countries. Specifically, Ram (2003) examined how bilateral and multilateral ODA impacted on the EG of 56 developing countries. The empirical findings confirmed that multilateral ODA has a negative effect on EG whereas bilateral ODA greatly boosts it. These findings suggest that recipient countries can use bilateral ODA more successfully since there are fewer conditions and a greater understanding of the program. Additionally, Amoa (2020) determined the effects of bilateral and multilateral ODA and EG of six African countries from 1978 to 2010. Amoa (2020) reported that both types of ODA have negative effects on the EG. In addition, this study revealed that the interaction between ODA and FDI significantly boosted EG in the studied countries. Moreover, Edo et al. (2023) investigated how different types of ODA, including bilateral and multilateral ODA, impacted on EG of Sub-Saharan African economies. The researchers documented that both bilateral and multilateral ODA had significantly positive effects on the countries EG, but the effects depended on how they were administered and utilized. Specifically, the impact of bilateral ODA is more significant than multilateral one. Similarly, Wambaka (2023) estimated the effects of bilateral and multilateral aid on EG for 28 middle and low-income Sub Sahara Africa nations from 1999-2015. The empirical findings indicated that only multilateral aid had significantly positive impact on EG, and that this impact depended on the presence of high-quality institutions.

In summary, theoretical frameworks posit the potential for ODA to promote EG but also caution against potential negative effects. Moreover, empirical evidence on the effect of ODA on EG has not reached a consensus. Specifically, most studies reported a positive effect of ODA on EG whereas others found a negative or no effect of foreign aid on EG. The diverse effects of ODA on EG often depend on the types of ODA, institutional capacity, and quality of governance in the recipient country.

3. Data and Research Methodology

3.1. Data

This study utilizes annual series of economic growth, bilateral ODA, multilateral ODA, and FDI of Vietnam from 1986 to 2022. This period was chosen for the study because Vietnam initiated its comprehensive economic reforms (Doi Moi) in 1986, marking the beginning of its economic opening and the end of a period of central planning. All data were obtained from the World Bank.

3.2. Research Methodology

Theoretically, the two-gap model, proposed by Chenery and Strout (1966), asserts that developing countries face two primary gaps: the savings-investment gap and the foreign exchange gap. Therefore, ODA can stimulate EG by bridging these gaps. In addition, endogenous growth theory suggests that internal elements, such as human capital, innovation, and knowledge, are crucial in promoting EG. ODA can boost EG by financing education, research and development, and technology transfer, which contribute to increasing returns to scale and sustained long-term growth. Empirically, several empirical studies confirmed that ODA has positive effects on EG (Burnside and Dollar, 2000; Gomanee et al., 2005; Refaei and Sameti, 2015; Das & Sethi, 2020; Azam and Feng, 2022; Wehncke et al., 2023, and Fazlly, 2024). As a result, it is hypothesized that ODA has a significantly positive effect on Vietnam’s EG. In addition, according to the endogenous growth theory, higher national savings can lead to more investment in research and development, which boosts productivity and growth. Therefore, it is expected that national savings have a positive effect on EG. Moreover, several studies documented that foreign direct investment (FDI) has significantly effects on EG (Driffield and Jones, 2013; Amoa, 2020; Wehncke et al., 2023; Zardoub and Sboui, 2023; Moloi, 2024). Based on the findings of previous studies, it is expected that FDI has a positive effect on EG. Therefore, this study investigates the effects of ODA on EG of Vietnam by employing the baseline regression model as follows:

where:

- -

LNGROWTH: Natural logarithm of Vietnam’s EG;

- -

LNBODA: Natural logarithm of Vietnam’s bilateral ODA inflows;

- -

LNMODA: Natural logarithm of Vietnam’s multilateral ODA inflows;

- -

LNSAV: Natural logarithm of Vietnam’s gross savings on GDP.

- -

LNFDI: Natural logarithm of Vietnam’s FDI inflows.

To capture the short-run and long-run effects of bilateral and multilateral ODA on the EG of Vietnam, the ARDL bounds testing approach developed by Pesaran et al. (2001) is applied in this study. This study employs the ARDL approach because this technique has some advantages compared to other co-integration methods (Truong et al., 2024). Firstly, the ARDL model does not require all variables have the same integration order. Instead, this approach just requires the integration order of all studied variables does not exceed 1. Secondly, the ARDL approach is generally more reliable and robust than other approaches for studies with a limited number of observations like this study. Finally, an error correction model (ECM) can be estimated from the ARDL model, and hence the short-run and the long-run effects of explanatory variables on the dependent variable can be simultaneously estimated. The ARDL representation for equation (1) is specified as follows:

where:

- -

Δ: The first difference of the variables;

- -

q1, q2, q3, q4, q5: The optimal number of lags for the variables.

It is noted that the ARDL model requires the integration orders of all variables do not exceed 1 (Truong et al., 2024). Therefore, unit root tests need to be conducted to ensure that all studied variables fulfill the model requirements. This study employs the widely used augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test to determine the integration orders of all variables. Before estimating the long-term effects, it is crucial to know whether the variables in the model are cointegrated. If they are not, then the long-term estimation would provide misleading results. The ARDL bounds test helps to confirm that whether the variables are suitable for long-term analysis. The null hypothesis (H0) of the ARDL bound test is that there is no cointegration among the variables. If the F-statistic computed from the bounds test exceeds the critical value at the given level, the null hypothesis is rejected, indicating the presence of cointegration among the variables. Once cointegration is confirmed, the short-term and long-term effects of bilateral and multilateral ODA on the EG are simultaneously estimated by the ARDL error correction model.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Sample

Based on the data obtained from the WB, some descriptive statistics of the studied variables over the period from 1986 to 2022 are calculated and presented in

Table 1.

Table 1 shows that Vietnam’s EG over the sample period was rather high and stable. Specifically, the average of EG over the studied period is 6.45% while the standard deviation is only 1.70%. In addition, statistics presented in

Table 1 show that the value of bilateral ODA is significantly higher than multilateral ODA inflows to Vietnam, meaning that Vietnam’s ODA is mainly bilateral ODA. In fact, the mean of bilateral ODA during the sample period was USD 2,107.96 million, whereas the average of multilateral ODA was only USD 40.56 million. Moreover, it is found that the bilateral ODA was highly volatile over the studied period, with a range from USD 124.28 million to USD 5,379.60 million, with a standard deviation of 1,531.00. Besides,

Table 1 indicates that the average of Vietnam’s gross savings on GDP for the period from 1986 to 2022 is 24.52%, ranging from -2.65% to 35.77%. Finally, statistics presented in

Table 1 reveal that Vietnam’s FDI highly fluctuated from 1986 to 2022. In fact, the mean of FDI inflows was USD 5,677.55 million, with a standard deviation of 5,798.15.

4.2. Results of the ADF Test

The results of the ADF test presented in

Table 2 indicate that the LNGROWTH and LNFDI series are I(0) while LNBODA, LNMODA and LNSAV series are I(1). These findings suggest that all the variables satisfy requirements of the ARDL bound test.

4.3. ARDL Bound Test for Cointegration

This study employs the bounds test proposed by Pesaran et al. (2001) to examine the long-run relationship among variables in the model. Based on the Akaike Information Criterion, the best model used for the bounds test is ARDL (4,4,4,4). The results of the bounds test contained in

Table 3 indicate that the null hypothesis of no cointegration among the variables is rejected at the five percent level. This evidence implies that there is a long-run equilibrium relationship among the variables in the model.

4.4. Short-Term and Long-Term Effects of Bilateral and Multilateral ODA on the EG

With the evidence of cointegration among the variables in the model, the short-run and long-run coefficients are estimated using the ARDL error correction model. The empirical findings presented in

Table 4 indicate that in the short-run, bilateral ODA has significantly positive impact on the EG for different time lags. Specifically, a 1% increase in bilateral ODA results in a 0.60% and 0.79% increase in the EG for the 2-year and 3-year lags, respectively. However, it is found from

Table 4 that in the short-run multilateral ODA has a negative effect on the EG at the significant level of 1%. Specifically, a 1% increase in multilateral ODA leads to a 1.52% decrease in the EG for the 3-year lag. In addition,

Table 4 reveals that in the short-run, the national gross savings (SAV) has a significantly positive effect on the EG. In fact, a 1% increase in SAV is contemporaneously associated with a 1.53% increase in the EG at the significant level of 5%. Moreover, the results reported in

Table 4 indicate that in the short-run, FDI positively impacts on the EG at the 1% level of significance. Specifically, a 1% increase in FDI is contemporaneously associated with a 0.91% increase in the EG. Furthermore, the coefficient of error correction terms is -0.8653, indicating that 86.53% of the deviation from the long-run equilibrium due to a shock in the current year will be adjusted back toward equilibrium in the next year.

In addition to estimating the short-term effect, the ARDL approach also allows for the estimation of the long-term of ODA on the EG. The empirical results reported in

Table 4 confirm that both the bilateral and multilateral ODA have no statistically significant impact on the EG. Especially, in the long-run, the empirical findings confirm that FDI has a significantly positive effect on the EG at the 5% level. Specifically, a 1% increase in FDI leads to 0.17% increase in the long-run. However, we found no evidence of a long-term effect of SAV on the EG.

Overall, this study find a considerable difference between the effects of the two ODA components. Specifically, bilateral ODA has significantly positive impact on the EG whereas multilateral ODA has a negative effect on the EG. However, our findings reveal that both the bilateral and multilateral ODA have no significant impact on the EG in the long-term. These findings are totally consistent with previous empirical findings of Ram (2003) and partially align with the findings of Edo et al. (2023). However, this evidence is contrary to the findings documented by Amoa (2020) and Wambaka (2023). There are some reasons to explain these different effects. First, bilateral donors could have closer ties and a better understanding of Vietnam’s context, challenges, and development needs. Therefore, bilateral ODA is financed more targeted and effective interventions that address the specific needs of the country. Second, bilateral ODA could have deeper expertise and experience in specific sectors or development challenges, allowing them to provide more tailored and effective assistance. Moreover, the negative impact of multilateral ODA on the EG of Vietnam could be explained by several reasons. First, multilateral ODA projects generally require strict compliance with international environmental, social, and financial management standards. While these standards are crucial for sustainable development, they can impose significant administrative burdens, slow project progress, and reduce the ability to achieve immediate economic impacts. Second, some multilateral ODA projects could not fully consider the environmental and social context of Vietnam in the transitional period. Therefore, projects that overlooked the environmental sustainability or social impacts might lead to long-term costs that offset any short-term economic gains. Third, multilateral ODA projects in Vietnam often involve multiple stakeholders, including international organizations, donor countries, and domestic management agencies. This complexity results in prolonged approval and implementation processes. Delays in implementation not only increase project costs but also reduce the immediate economic impact, negatively affecting short-run economic growth.

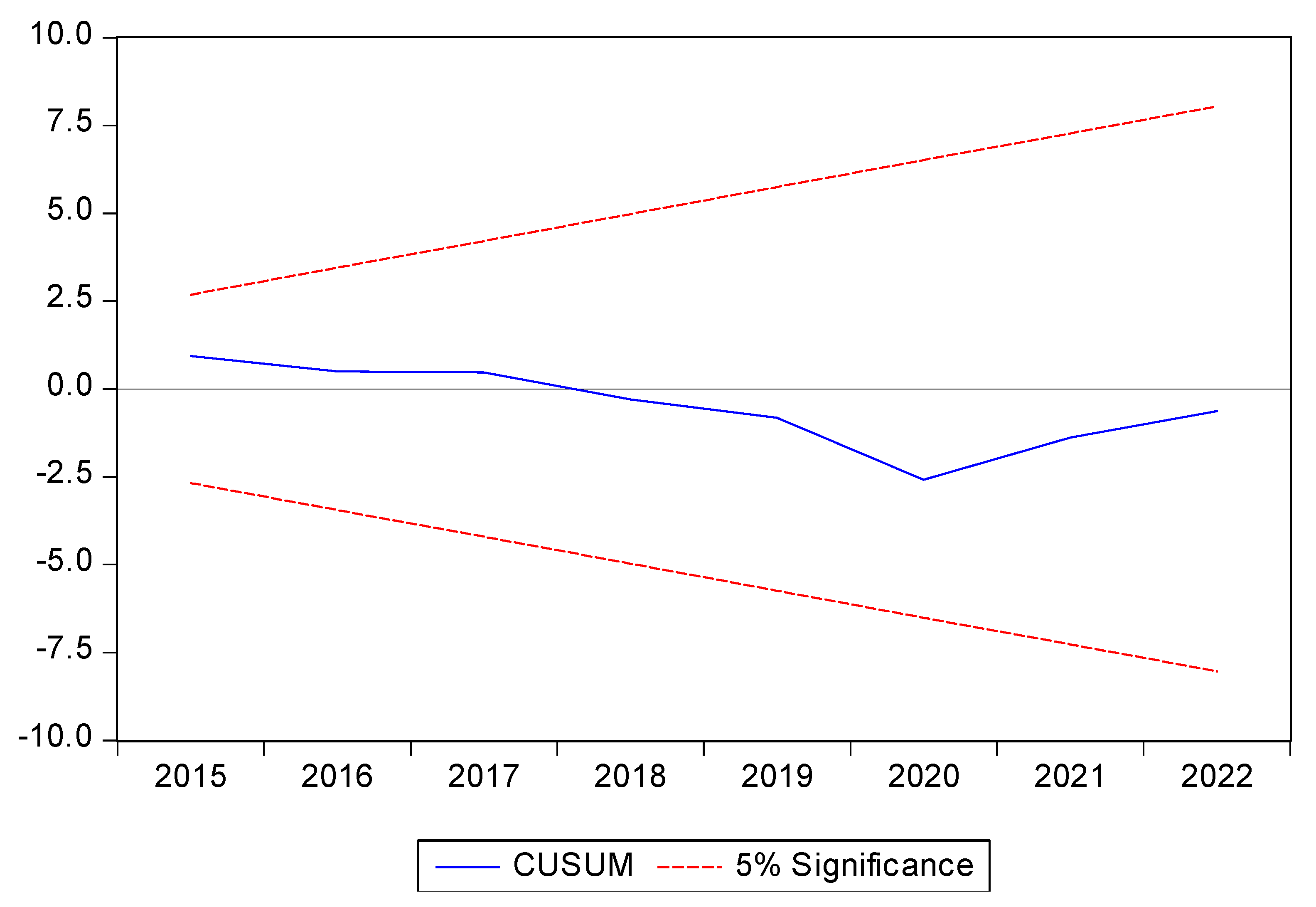

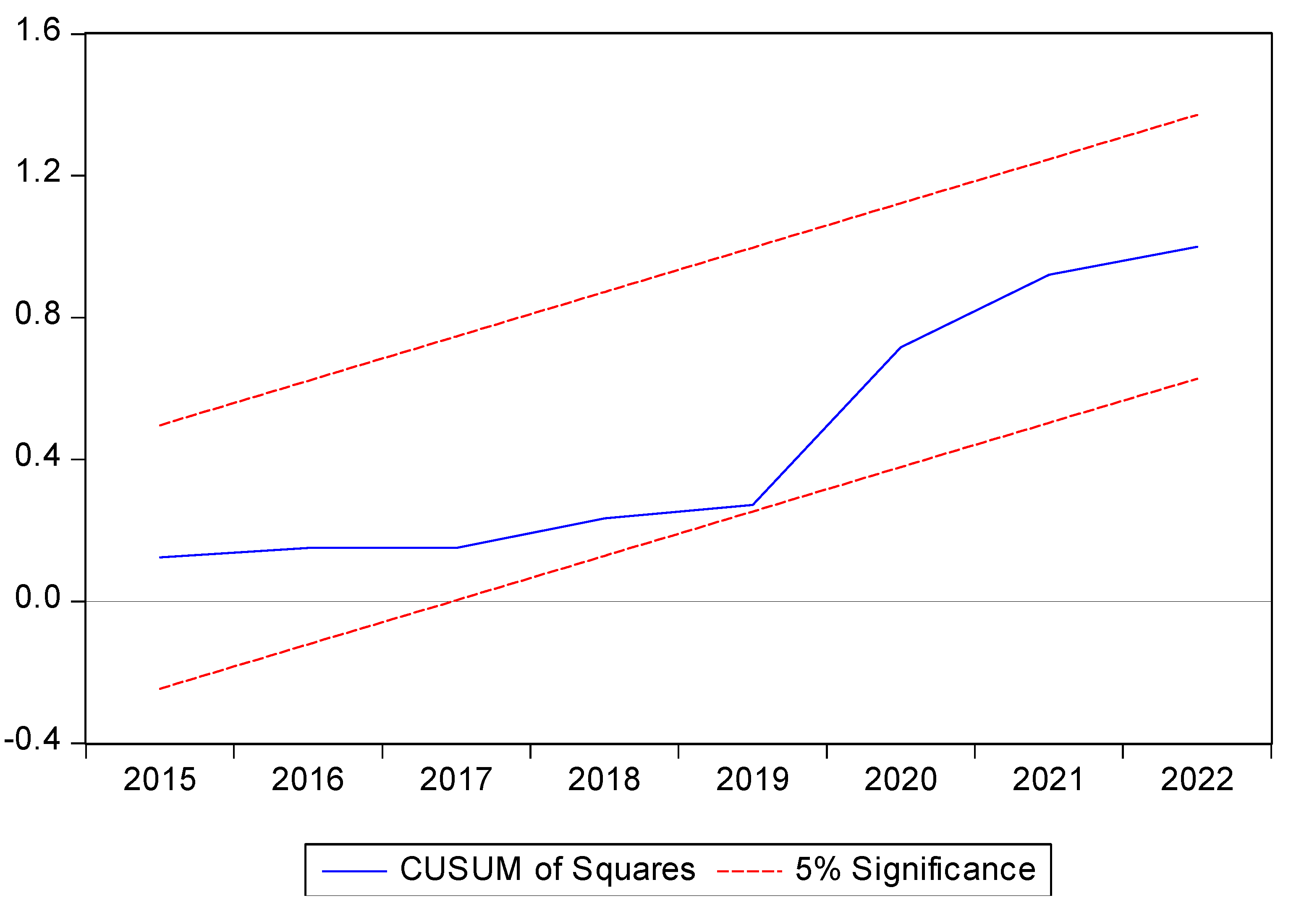

4.5. Diagnostic and Structural Stability Tests

To check the robustness of the model, diagnostic tests of Breach-Godfrey for autocorrelation and ARCH test for heteroscedasticity are used in this study. The results reported in

Table 5 reveal autocorrelation among the residuals does not exist in the model. Moreover, the results of the ARCH test indicate that the residuals exhibit homoscedasticity. The results derived from these tests confirm the reliability and validity of the estimated results.

Furthermore, this study employs the cumulative sum (CUSUM) and cumulative sum of squared (CUSUMSQ) tests to examine the long-term stability of the model. The findings illustrated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 confirm the model is stable throughout the studied period.

5. Conclusions

This study empirically examined the short-run and long-run effects of bilateral and multilateral ODA on the EG of Vietnam over the transitional period from 1986 to 2022. The results obtained from the ARDL model confirmed that there is a significant difference between the effects of the two ODA components on the EG in the short-run. Specifically, bilateral ODA has a significantly positive effect on the EG whereas multilateral ODA has significantly negative impact on the EG. However, the empirical findings indicated that both bilateral and multilateral ODA have no impact on the EG in the long-run. In addition, the findings confirmed that FDI has a significantly positive effect on the EG in the short-run, but has no impact on the EG in the long-run. Finally, the findings obtained from the ECM indicated that 86.53% of the deviation from the long-run equilibrium due to a shock in the current year will be adjusted back toward equilibrium in the next year.

While the study has expanded our understanding of the impact of bilateral and multilateral ODA on EG in a transition economy, it still has some limitations that future research has the potential to explore. Due to limitations of the data, this study examined the impact of bilateral and multilateral ODA on EG without taking into account the moderating effects of quality of governance and institutional capacity variables on the effects of bilateral and multilateral ODA. Therefore, future studies should investigate how the quality of governance and institutional capacity moderate the impact of bilateral and multilateral ODA on Vietnam’s EG. The second limitation of the study is that the Covid-19 pandemic could impact on Vietnam’s ODA inflows and economic growth, but it has not been considered while measuring the effect of ODA on EG of Vietnam. This limitation could be an interesting topic for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.D.T. and A.T.L.; methodology, L.D.T. and H.S.F.; software, L.D.T.; validation, H.S.F. and A.T.L; formal analysis, L.D.T., H.S.F. and A.T.L; investigation, L.D.T.; resources, A.T.L.; data curation, L.D.T. and A.T.L.; writing—original draft preparation, L.D.T., H.S.F. and A.T.L.; writing—review and editing, H.S.F. and L.D.T.; visualization, L.D.T. and H.S.F.; project administration, L.D.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this research are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Amoa, Adèle M. Ngo Bilong. 2020. Effectiveness of bilateral and multilateral official development assistance on economic growth in CEMAC: an expansion variable analysis method. Theoretical Economics Letters 10(2): 322–333. [CrossRef]

- Awino, Omenda Purity, and Urbanus Mutuku Kioko. 2022. The effect of official development assistance aid on economic growth and domestic savings in Kenya. International Journal of Finance, Insurance and Risk Management 12(4): 63–77.

- Azam, Muhammad, and Yi Feng. 2022. Does foreign aid stimulate economic growth in developing countries? Further evidence in both aggregate and disaggregated samples. Quality & Quantity 56(2): 533–556. [CrossRef]

- Burnside, Craig, and David Dollar. 2000. Aid, policies, and growth. American Economic Review 90(4): 847–868. [CrossRef]

- Cassola, Adèle, Prativa Baral, John-Arne Røttingen, and Steven J. Hoffman. 2022. Evaluating official development assistance-funded granting mechanisms for global health and development research that is initiated in high-income countries. Health Research Policy and Systems 20: 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Chansombuth, Soulivanh. 2023. Effectiveness analysis for Japanese ODA impact on growth: Empirical results from Laos. Journal of International Studies 16(3): 117–126. [CrossRef]

- Chenery, Hollis B., and Alan M. Strout. 1966. Foreign assistance and economic development. American Economic Review 56(4): 679–733. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1813524.

- Das, Aurolipsa, and Narayan Sethi. 2020. Effect of foreign direct investment, remittances, and foreign aid on economic growth: Evidence from two emerging South Asian economies. Journal of Public Affairs 20(3): 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Driffield, Nigel, and Chris Jones. 2013. Impact of FDI, ODA and migrant remittances on economic growth in developing countries: A systems approach. The European Journal of Development Research 25(2): 173–196. [CrossRef]

- Edo, Samson, Oluwatoyin Matthew, and Ifeoluwa Ogunrinola. 2023. Bilateral and multilateral aid perspectives of economic growth in sub-Saharan Africa. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies 14(1), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Ekanayake, E. M., and Dasha Chatrna. 2010. The effect of foreign aid on economic growth in developing countries. Journal of International Business and Cultural Studies 3: 1–13.

- Eregha, Perekunah. B., and Tope Rufus Oziegbe. 2016. Official development assistance, volatility and per capita real GDP growth in sub-Saharan African countries: a comparative regional analysis. The Journal of Developing Areas 50(4): 363–382. [CrossRef]

- Fazlly, Sayed Kifayatullah. 2024. Foreign aid and economic growth: an econometric study of Afghanistan. Journal of Indonesian Applied Economics 12(1): 46–54. [CrossRef]

- Feeny, Simon. 2005. The impact of foreign aid on economic growth in Papua New Guinea. Journal of Development Studies 41(6): 1092–1117. [CrossRef]

- Gomanee, Karuna, Sourafel Girma, Oliver Morrissey. 2005. Aid and growth in Sub-Saharan Africa: accounting for transmission mechanisms. Journal of International Development 17(8): 1055–1075. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Jiaqi, Qiang Wang, and Rongrong Li. 2024. Can official development assistance promote renewable energy in sub-Saharan Africa countries? A matter of institutional transparency of recipient countries. Energy Policy 186: 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Liew, Chung Yee, Masoud Rashid Mohamed, and Said Seif Mzee. 2012. The impact of foreign aid on economic growth of East African countries. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development 3(12): 129–138.

- Mackinnon, James G. 1991. Critical values for cointegration tests. In R. Engle & C. Granger (Eds.), Long-run economic relationships: Readings in cointegration. Oxford University Press.

- Mallik, Girijasankar. 2008. Foreign aid and economic growth: A cointegration analysis of the six poorest African countries. Economic Analysis & Policy 38(2): 251–260. [CrossRef]

- Moloi, Vincent Muziwakhile Mbongeleni. 2024. The threshold analysis of the official development assistance (ODA), foreign direct investment (FDI), and economic growth in selected African countries. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science 13(5): 558–570. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Hien Phuc, Anh Ngoc Quang Huyn, Ulrike Reisach, and Xuyen Le Thi Kim. 2022. How does Japanese ODA contribute to economic growth of ASEAN countries? Journal of International Economics and Management 22(2): 71–83. [CrossRef]

- Ono, Saori, and Takashi Sekiyama. 202). The impact of official development assistance on foreign direct investment: The case of Japanese firms in India. Frontiers in Political Science 6: 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Orchi, Rashik Mahmud, and Md. Adib Ahmed. 2024. Remittances, exports, ODA, and economic growth in Bangladesh: A time series analysis. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development: 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M. Hashem, Yongcheol Shin, and Richard J. Smith. 2001. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics 16: 289–326. [CrossRef]

- Rahnama, Masha, Fadi Fawaz, and Kaj Gittings. 2017. The effects of foreign aid on economic growth in developing countries. The Journal of Developing Areas 51(3): 153–171. [CrossRef]

- Ram, Rati. 2003. Roles of bilateral and multilateral aid in economic growth of developing countries. Kyslos 56: 95–110. [CrossRef]

- Refaei, Ramiar Refaei, and Morteza Sameti. 2015. Official development assistance and economic growth in Iran. International Journal of Management, Accounting & Economics 2(2): 125–135.

- Sengupta, Arjun. 2002. Official development assistance: the human rights approach. Economic and Political Weekly 37(15): 1424–1436.

- Siraj, Tofik. 2012. Official development assistance (ODA), public spending and economic growth in Ethiopia. Journal of Economics and International Finance 4(8): 173–191. [CrossRef]

- Stojanov, Robert, Daniel Němec, and Libor Žídek. 2019. Evaluation of the long-term stability and impact of remittances and development aid on sustainable economic growth in developing countries. Sustainability 11(6): 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Truong, Loc Dong, H. Swint Friday, and Tan Duy Pham. 2024. The effects of geopolitical risk on foreign direct investment in a transition economy: Evidence from Vietnam. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 17(3): 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Wambaka, Kosea. 2023. Impact of bilateral and multilateral aid on economic growth in low and middle-income Sub Sahara African countries: Mediating role of institutional quality. International Business Research 16(1): 44–53. [CrossRef]

- Wehncke, Francois Cornelius, Godfrey Marozva, and Patricia Lindelwa Makoni. 2023. Economic growth, foreign direct investments and official development assistance nexus: Panel ARDL approach. Economies 11(1): 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Zardoub, Amna, and Faouzi Sboui. 2023. Impact of foreign direct investment, remittances and official development assistance on economic growth: panel data approach. PSU Research Review 7(2): 73–89. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).