1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 40 million amputees reside in developing countries, yet only 5% have access to prosthetic care [

1,

2]. This stark disparity underscores a critical global health challenge. The demand for prosthetic supplies is projected to increase as a result of vascular complications, diabetics and traumatic accidents in these regions [

3]. However, the availability of prosthetic healthcare resources is severely limited, particularly in underserved areas, complicating the acquisition and fitting of necessary prosthetic devices for amputees [

4]. The high costs associated with prosthetics, coupled with the need for specialized expertise and the scarcity of trained technicians, further exacerbates this issue.

Thermoplastic polypropylene (PP) has been widely adopted for socket fabrication, as standardized by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). This low-cost material helps mitigate the expenses of prosthetic services in low-income countries [

5,

6]. In an extensive review of lower limb prosthetic technologies in developing countries, Andrysek et al. (2010) emphasized that the primary goals of the International Society of Prosthetics and Orthotics (ISPO) organization should focus not only on maintaining sound biomechanical principles for amputees but also on keeping prosthetic services economically affordable [

2]. Establishing training programs to produce qualified personnel is essential to improving prosthetic care in developing countries. Despite these initiatives, significant barriers remain, particularly the high costs associated with skilled prosthetists and trained orthopedic technologists, which continue to limit access for many underserved populations.

In the context of reducing the cost of Transtibial Prosthetic (TP) services, this paper explores a feasible solution aimed at addressing the cost of prosthetic personnel. This solution involves the standardization of the size and volume of Transtibial sockets, and the maintenance of a “neutral” socket alignment in the design and clinical fitting. This concept, known as Mercer Universal Prostheses (MUP

®), presents a promising approach to enhancing accessibility and affordability of prosthetic care [

7,

8]. Vo et al. in 2018 suggested that the MUP concept addresses the urgent need for cost-effective prosthetic solutions without compromising quality or functionality [

7]. Vo et al.’s paper described the technical aspects, clinical implementation, and potential impact of the MUP, emphasizing its benefits and outlining future research directions.

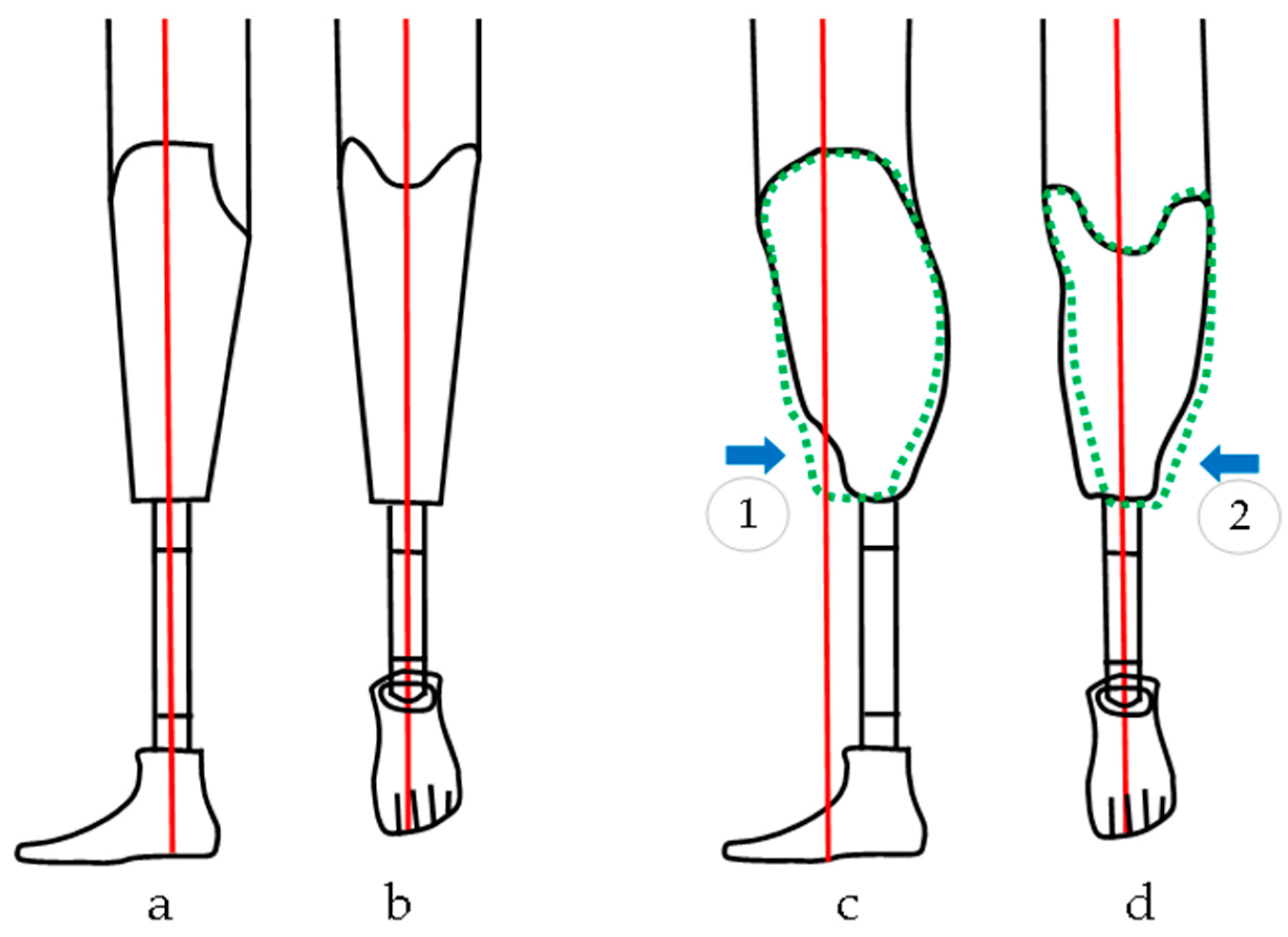

Socket alignment plays a critical role in various aspects of prosthetic fitting for Transtibial prosthetics, such as comfort, balance, and stability, irrespective of the prosthetic socket fit and components chosen [

9,

10]. Conventional prosthesis (CVP) alignment involves three stages: bench, static, and dynamic alignment. Bench and static alignment entail setting the prosthetic socket in a default orientation (e.g. +5

o flexion in the sagittal plane and +5

o in the frontal plane,

Figure 1) while setting the prosthetic foot at a 5–7

o external rotation [

11,

12,

13,

14]. By contrast, dynamic alignment (DA) allows for further adjustments of up to ±10

o in both the frontal and sagittal planes; this process is time-intensive and requires expertise [

15]. Unfortunately, dynamic alignment can be biased, as prosthetists must accommodate patients’ perceptions of socket pressure, often resulting in alignment that prioritizes patient’s comfort over gait function and long-term joint health [

9,

11,

12,

15,

16]. This patient-driven DA may lead to a misaligned prosthesis, deviating from the clinician's intended alignment[

13,

15]. Misalignment can cause imbalanced loading between the intact and affected limbs, which may result in joint degradation or osteoarthritis (OA), and eventually reduced patients’ quality of life as the OA disease progresses in long-term [

15,

16].

Despite clinical efforts to optimize dynamic alignment (DA) for gait symmetry, studies on Transtibial gait with socket DAs have not shown significant changes in gait symmetry when DA is adjusted within the clinically accepted 10-degree (i.e. +/- 5 degree) tolerance [

9,

12,

14,

15,

16]. If symmetry remains unchanged within this DA tolerance, and if comfort is not worsened, adopting a standard alignment, as with the MUP “neutral” alignment concept, could benefit current and future amputees. This approach not only reduces the cost of prosthetic services in developing countries but also potentially eliminates the need for the DA process in current fitting procedures, simplifying the fitting process, reducing fitting time, and significantly lowering prosthetic costs.

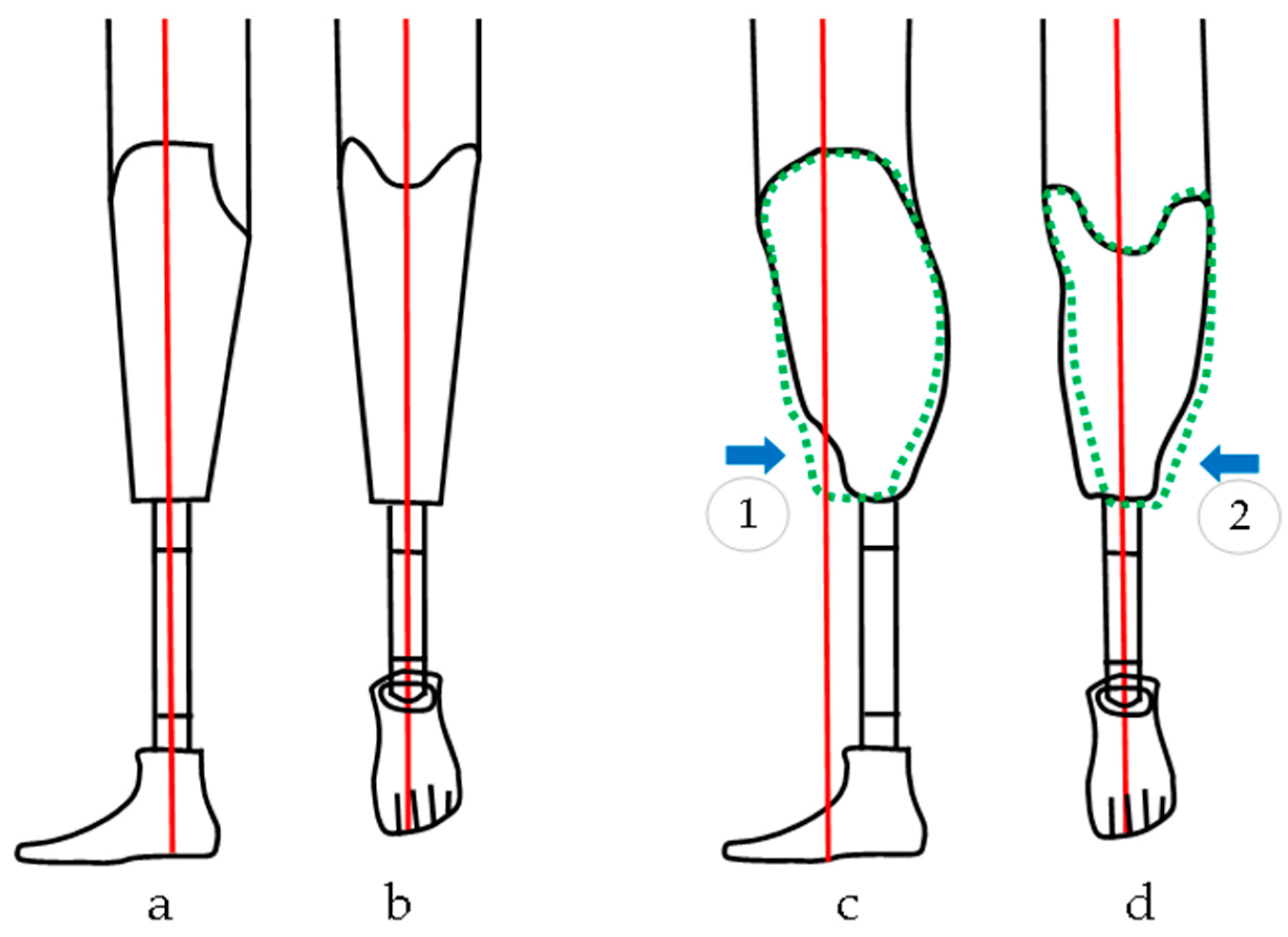

In contrast with CVP, the MUP employs a patella weight bearing socket design with a default axial alignment. Consequently, the MUP endeavors to maintain alignment with the femoral and tibial bone longitudinal axes (see

Figure 1). The longitudinal axis of the socket aligns with the pylon axis in relation to the prosthetic foot, and this neutral alignment remains constant throughout prosthetic fitting. The MUP fitting procedures are standardized, providing a practical method for training local technicians within a short period (i.e. 3-4 weeks) so they can successfully perform fittings. Efforts to reduce personnel costs for prosthetic fitting have demonstrated the potential and competency of the MUP concept compared to conventional custom-made prosthetic devices. Additionally, MUP socket technology, pre-made using low-cost PP further contributes to cost reduction [

7,

8,

17].

The MUP for transtibial amputees, costing only

$150, has been fitted for over 18,000 amputees in Vietnam and Cambodia since 2009 [

7,

8]. These countries have the highest number of amputees per capita due to landmines and explosive devices remaining from past conflicts [

17]. Since 2009, MUP technology has been sponsored and distributed free of charge in several rural regions of Vietnam (e.g., Ben Tre, An Giang, Dong Thap, Kien Giang, Quang Tri, Thai Nguyen) and Cambodia (Preah Vihear) through Mercer On Mission (MOM), a service-learning program operated by Mercer University in Macon, Georgia, USA [

7]. The MOM program incorporates service learning and cultural exchange for motivated undergraduate and graduate students, regardless of their backgrounds and majors. The MUP concept of universal design and standard alignment has proven effective and transferable to train Mercer students.

Under ISPO certification, VIETCOT (Vietnamese Training Centre for Orthopedic Technologies) and ICRC operate clinics, train prosthetic technologists, and provide prosthetic healthcare in Vietnam and Cambodia. However, demand for low-cost prosthetic devices continues to exceed supply and remains a challenge due to a lack of trained technologists. To achieve ISPO or ICRC recognition and certification for MUP technology, extensive research is necessary to demonstrate the biomechanical effectiveness of MUP prostheses in amputees. This paper aims to quantitatively compare the gait characteristics of Transtibial amputees using both conventional custom-made (CVP) and MUP prostheses. It is hypothesized that temporal/spatial and kinematic gait parameters will differ between the sound limb and prosthetic limb in Transtibial amputees using both conventional custom-made (CVP) and Mercer Universal (MUP) prostheses, and there will be small differences between MUP and CVP within intact and prosthetic limbs. In addition, gait symmetry is expected to show small differences between MUP and CVP for both kinematics and temporal/spatial parameters.

4. Discussion

The Mercer Universal Prostheses (MUP) concept involves a standardized socket alignment and a universal pre-made socket design. This study aimed to investigate the immediate effects of MUP prostheses on gait symmetry, focusing on kinematic, temporal, and spatial gait parameters. Sagittal joint angles (hip, knee, and ankle) were the primary focus due to their consistency and minimal error in IMU-based kinematic measurements [

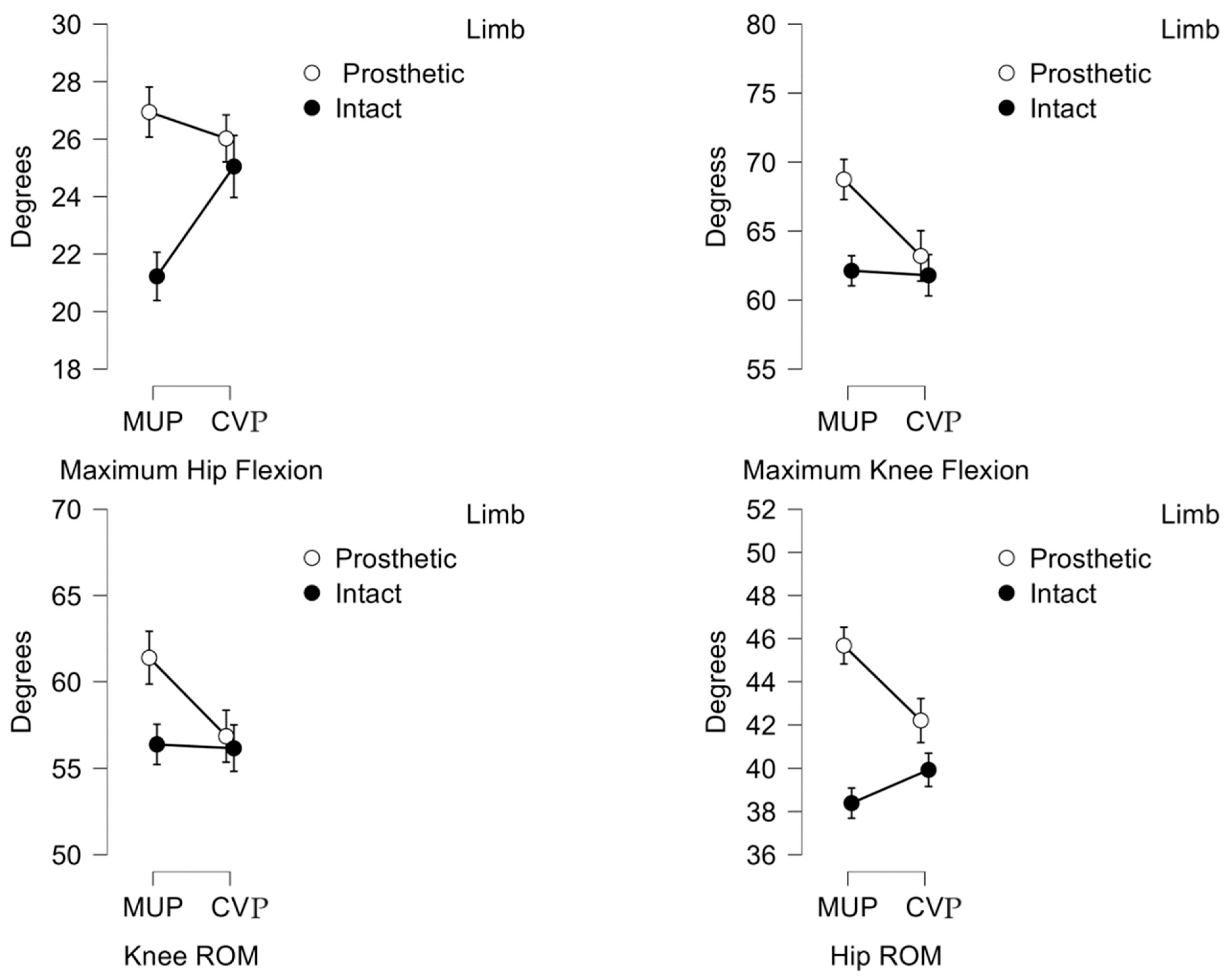

28]. As expected, kinematic outcomes showed some degree differences between the intact and prosthetic limbs in Transtibial amputees using both CVP and MUP prostheses. Temporal and spatial outcomes remained consistent between the two devices. Gait symmetry also showed small differences between MUP and CVP.

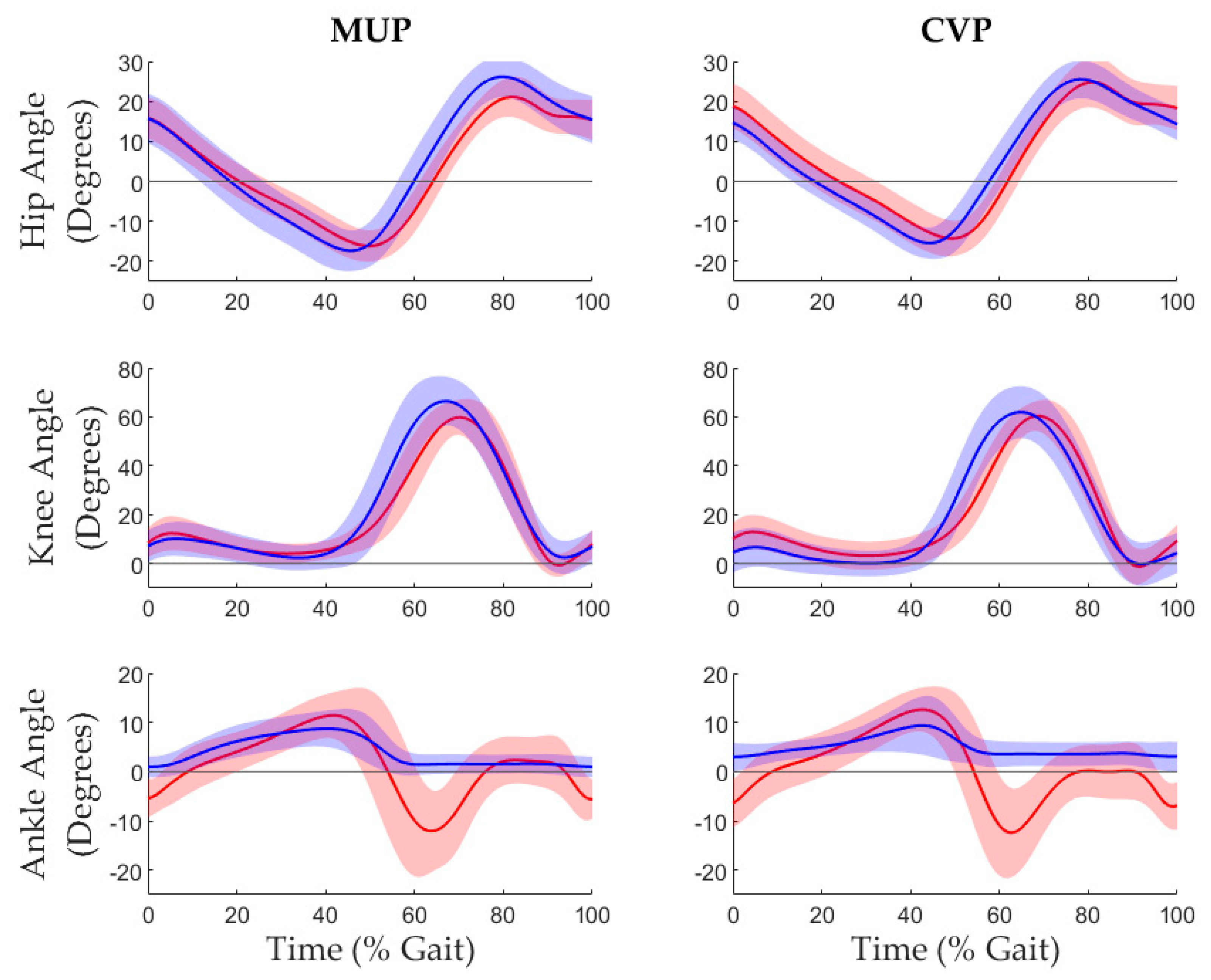

Analysis revealed significant alterations in kinematics, particularly in the prosthetic limb, immediately after fitting with the MUP. Participants exhibited greater knee flexion (about 5.7°) and hip flexion (about 6.6°) in the prosthetic limb compared to the intact limb (refer to

Figure 6). This resulted in an increased hip and knee range of motion (3.4° and 2.5°, respectively) in the MUP group, with no significant differences in the CVP group. These findings suggest that the MUP device influences biomechanics, and specifically inter-limb symmetry differently, compared to CVP, particularly in the hip and knee joint angles. The MUP device appears to enhance joint mobility, especially in the prosthetic limb, leading to greater hip/knee flexion and hip/knee ROM, which may contribute to a more balanced and efficient gait. This increased mobility could reduce compensatory movements and the risk of overuse injuries in the intact limb. Clinically speaking, these results suggest that the MUP may be more effective in promoting natural gait patterns, which could improve long-term mobility and quality of life for amputees. Future research should explore the longitudinal effects of these kinematic adaptations on gait function, stability, and comfort.

To contextualize these findings, the hip and knee range of motion (ROM) from the CVP device in this study were compared to those reported in Laing’s 2018 study on Vietnamese amputees using conventional prostheses. Laing et al. reported a hip ROM of 37° in the sound limb and 36° in the prosthetic limb, while this study found hip ROMs of about 40° in the intact limb and 42° in the prosthetic limb. Additionally, Laing’s study also reported knee ROM of 70.7° in the intact limb and 61.4° in the prosthetic limb, whereas this study reported approximately 63° in the intact limb and 66.3° in the prosthetic limb. The cadence in this study (approximately 75 steps/min) was lower than that in Laing’s study (about 96 steps/min), which may account for some of the discrepancies in kinematic measurements[

29,

30,

31].

The kinematic measurements in this study were obtained using Noraxon IMU technology, which has been validated in healthy control subjects by Berner et al. (2020) and Park et al. (2021), demonstrating that sagittal joint angles can be accurately compared with those obtained using optical motion capture (OMC) systems, with hip angle differences within ±1° [

18,

19]. However, Park’s study noted that knee and ankle joint angles may be overestimated and underestimated, respectively, during the swing phase, which is an important consideration for clinical practice [

17]. In this study, the differences in hip and knee kinematics between the MUP and CVP devices in the both prosthetic and sound limbs were minimal; for example, peak hip flexion differed by approximately 1

0 , hip ROM differed by 3.5

0, and differences in peak knee flexion and ROM were approximately 5.6

0 and 4.5

0, respectively. In the sound limb, the MUP group presented with a slightly reduced both hip flexion and hip ROM (i.e. about 3.8

0 for hip flexion and 1.5

0 for hip ROM). The knee kinematic differences in the sound limb between MUP and CVP were found negligible (<1

0). In addition, the differences between intact and prosthetic limbs was increased approximately 5.7

0 for hip flexion, 7.3

0 for hip ROM in the MUP group while CVP group showed slightly differences in hip flexion (<1

0) , and 2.3

0 for hip ROM. Similarly, knee kinematics were found slightly differences between intact and prosthetic limbs in the CVP group (1.5

0 of knee flexion and <1

0 of knee Rom) while the differences were found higher in the MUP group (about 6.6

0 of knee flexion and 5

0 of knee ROM) (see

Figure 6) . These differences in hip and knee kinematics between limbs and devices, as measured by the Noraxon Utium IMU system, were considered within the clinically acceptable error margin of 5-7° when comparing IMU versus gold-standard OMC measurements [

19]. Thus, kinematics was similar between CVP and MUP devices within both prosthetic and intact limbs, relative to measurement error.

The increase in maximum hip and knee ROM angles immediately after fitting the MUP’s prosthetic limb could be attributed to the MUP’s lighter weight compared to the CVP in this study [

5]. According to Bateni’s 2004 study, changing prosthetic components from steel to titanium helped reduce the physiological cost index (PCI), increase the amputee’s relative speed, and emphasize kinematic changes [

32]. These findings suggest that the type of prosthesis and walking speed are crucial factors influencing the ROM in transtibial amputees, highlighting the importance of considering these variables in future prosthetic design and fitting processes. Nevertheless, in the present study, gait speed did not differ significantly between MUP and CVP devices.

No significant interactions were observed in temporal and spatial gait parameters immediately after fitting the MUP device. However, stance and swing times were significantly affected by both the device and limb factors. Within-subject analysis revealed that the prosthetic limb had a significantly shorter stance phase and a prolonged swing phase, while the intact limb exhibited the opposite pattern. This reflects typical amputee gait characteristics, where the intact limb is favored for stability [

23,

29,

30,

31,

32]. The MUP device led to slight improvements in balancing stance and swing times between the intact and prosthetic limbs. Notably, changes in the MUP’s prosthetic limb caused a reduction in stance and swing times in the intact limb, suggesting patient acceptance of the MUP device immediately after fitting. However, these changes could also indicate that the patient did not feel fully confident so soon after receiving the MUP device.

Gait symmetry is often associated with reduced energy expenditure, lower risk of overuse injuries, and better overall mobility. The differences in symmetry observed between prosthetic and intact limb within the devices could therefore have important implications for long-term outcomes in prosthetic users. The lack of significant differences in temporal and spatial measurements (such as speed, stride time, stride length, and step length) suggests that both the MUP and CVP devices allow for similar overall gait mechanics. The prosthetic users in this study maintained consistent walking temporal/spatial gait parameters regardless of which device they used. The CVP device was associated with better symmetry between intact and prosthetic limbs for both hip and knee flexion compared to the MUP. Specifically, hip flexion symmetry was 19% better, and knee flexion symmetry was 8% better with the CVP device. This suggests that the CVP device may promote more balanced movement between the prosthetic and intact limbs at these joints, which could be important for maintaining a stable and efficient gait. In contrast, the MUP device showed 24.4% greater symmetry in ankle plantarflexion compared to the CVP device. This implies that the MUP device might be better at replicating the natural movement of the ankle, leading to a more balanced motion in this specific joint. The C-shape design of MUP prostheses (see

Figure 2) aims to mimic natural ankle motion by enhancing dorsiflexion/plantarflexion and improving overall ankle ROM [

5,

6]; this could allow more natural ankle motion which would explain the difference in the ankle joint motion ROM compared to the CVP’s prosthetic SACH foot [

7,

8,

33]. Collectively, these findings suggest that each device has specific strengths. The CVP device appears to promote better symmetry in hip and knee movements since it is the participant’s current, habitual device. On the other hand, the MUP device exhibited less symmetry at hip and knee joints immediately after fitting, but it seems to enhance symmetry between intact and prosthetic limbs at the ankle, thus providing more natural ankle movement. Importantly, GSI has some limitations. Human gait is complex, and GSI is just a single number that may not capture all aspects of gait symmetry. Moreover, GSI in amputee during training session can be influenced by various factors such as walking speed, fatigue, or the environment in which the gait is assessed [

25]; therefore, it should be interpreted with an understanding of its limitations and in the context of the broader assessment of gait.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, HV, SB and TL ; methodology, TL and SB; software, TL and SB; validation, HV, TL and SB; formal analysis, SB, TL; investigation, HV, CM, SB and TL; resources, HV, CM; data curation, TL and SB; writing—original draft preparation, TL; writing—review and editing, HV, CM, SB and TL; visualization, TL; supervision, CM, HV and SB; project administration, CM and HV; funding acquisition, CM . All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Conceptual alignment differences between Mercer Universal (MUP) and Conventional (CVP) Prostheses. (a)(b): The MUP’s alignment is established at neutral in both sagittal and frontal views, rendering both anterior and lateral socket tilts at 00. (c)(d): Conventional (CVP) prostheses with bench alignment typically set at a default of +5° socket flexion (1) and +5° adduction (2) from neutral position in the sagittal and frontal planes. Note: Alignment of socket with respect to the foot (the mechanical axis) indicates in red line showing MUP’s alignment in sagittal plane is projected by the middle of the foot arch while CVP’s sagittal alignment is bisected the socket and is projected anteriorly by the foot. Each device aims to project the socket alignment between 1st and 2nd toes (foot external rotation) with respect to the foot in the frontal plane causing the prosthetic foot to externally rotated about 5-70. Lastly, the MUP socket is designed and pre-made with Universal Concept by using injection molding, and CVP has a custom-made socket. Further reducing labor-intensity and expense.

Figure 1.

Conceptual alignment differences between Mercer Universal (MUP) and Conventional (CVP) Prostheses. (a)(b): The MUP’s alignment is established at neutral in both sagittal and frontal views, rendering both anterior and lateral socket tilts at 00. (c)(d): Conventional (CVP) prostheses with bench alignment typically set at a default of +5° socket flexion (1) and +5° adduction (2) from neutral position in the sagittal and frontal planes. Note: Alignment of socket with respect to the foot (the mechanical axis) indicates in red line showing MUP’s alignment in sagittal plane is projected by the middle of the foot arch while CVP’s sagittal alignment is bisected the socket and is projected anteriorly by the foot. Each device aims to project the socket alignment between 1st and 2nd toes (foot external rotation) with respect to the foot in the frontal plane causing the prosthetic foot to externally rotated about 5-70. Lastly, the MUP socket is designed and pre-made with Universal Concept by using injection molding, and CVP has a custom-made socket. Further reducing labor-intensity and expense.

Figure 2.

Vietnamese Transtibial Amputee. (Top Left, L) Wearing a Conventional Prosthesis (CVP). (Top Right, R) Wearing a Transtibial MUP Prosthesis. (Bottom) Mercer Patented C-shaped prosthetic foot design (patent ID: US8870968B2).

Figure 2.

Vietnamese Transtibial Amputee. (Top Left, L) Wearing a Conventional Prosthesis (CVP). (Top Right, R) Wearing a Transtibial MUP Prosthesis. (Bottom) Mercer Patented C-shaped prosthetic foot design (patent ID: US8870968B2).

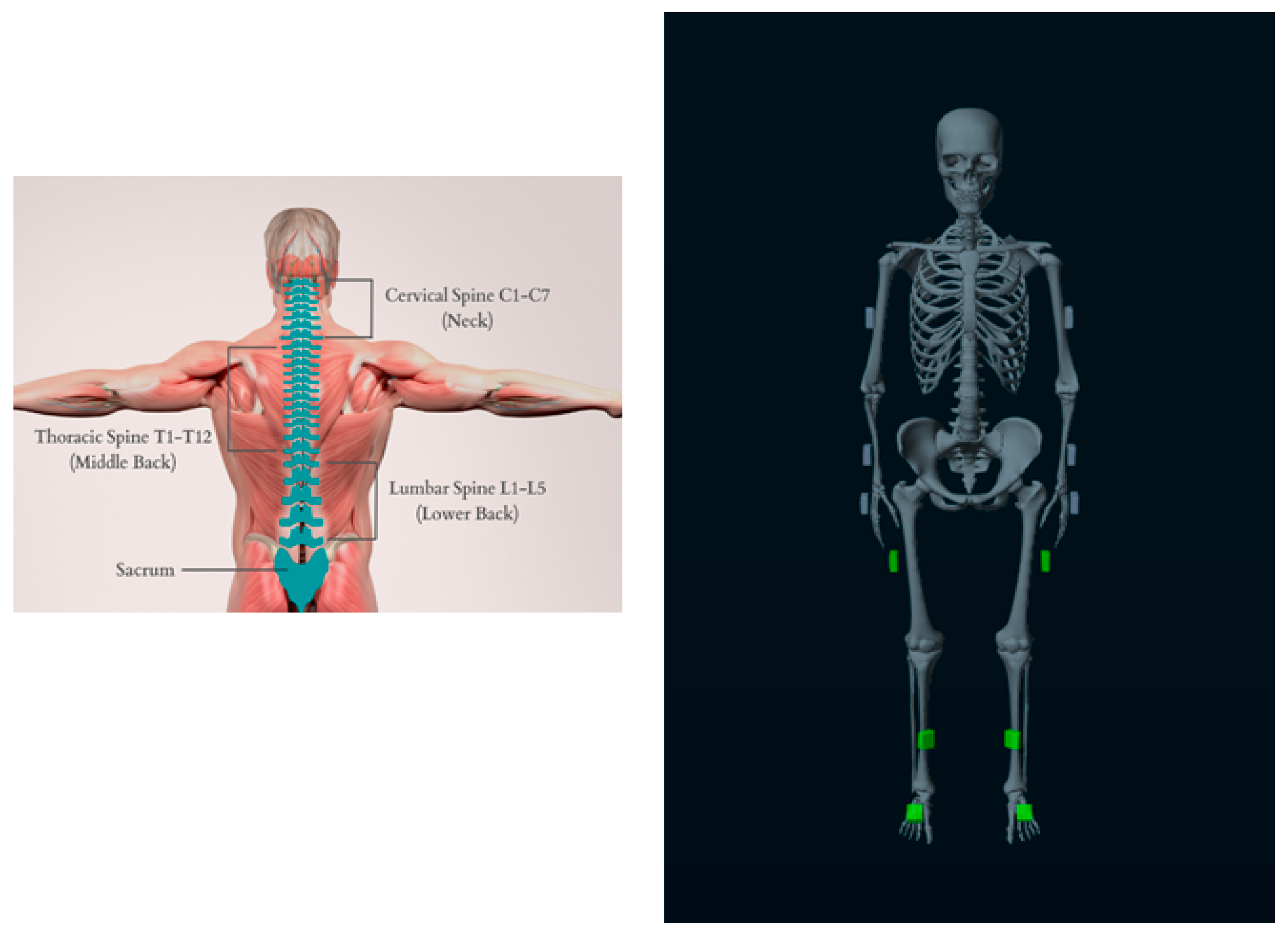

Figure 3.

Noraxon Utium IMU sensor placement. IMUs were attached on the posterior lumbar spine (between L1-L5), posterior pelvis (body area of the sacrum), thigh (frontal and distal half, where there is a lower amount of muscle displacement during gait), and shank (front and slightly medial to be placed along the flattest tibia bone or prosthesis pylon), and a foot (upper foot, slightly below the ankle).

Figure 3.

Noraxon Utium IMU sensor placement. IMUs were attached on the posterior lumbar spine (between L1-L5), posterior pelvis (body area of the sacrum), thigh (frontal and distal half, where there is a lower amount of muscle displacement during gait), and shank (front and slightly medial to be placed along the flattest tibia bone or prosthesis pylon), and a foot (upper foot, slightly below the ankle).

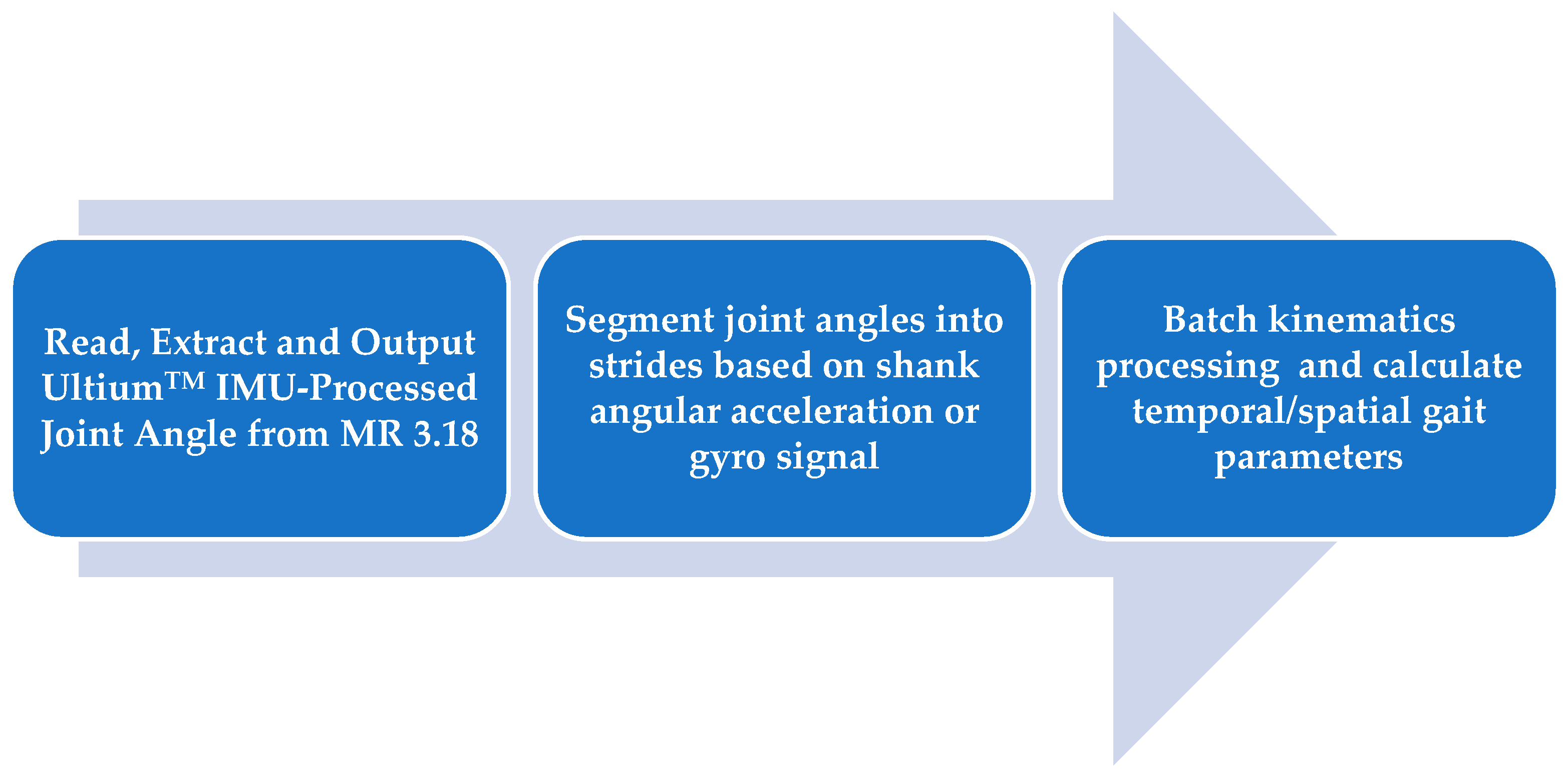

Figure 4.

Pipeline of Kinematic IMU data processing. Data were exported from Noraxon software (MR 3.18) to MATLAB, then segmented into strides based on heel strike (HS) and toe off (TO) events which were derived from sagittal shank angular acceleration or gyro data [

21,

22]. Finally, peak and symmetry measures were computed.

Figure 4.

Pipeline of Kinematic IMU data processing. Data were exported from Noraxon software (MR 3.18) to MATLAB, then segmented into strides based on heel strike (HS) and toe off (TO) events which were derived from sagittal shank angular acceleration or gyro data [

21,

22]. Finally, peak and symmetry measures were computed.

Figure 5.

Interaction Plots of the kinematic Hip and Knee joint angle showing the interaction between prosthetic and intact limb happening in the MUP and CVP groups (a) Maximum Hip Flexion (b) Maximum knee Flexion (c) Knee ROM (d) Hip ROM.

Figure 5.

Interaction Plots of the kinematic Hip and Knee joint angle showing the interaction between prosthetic and intact limb happening in the MUP and CVP groups (a) Maximum Hip Flexion (b) Maximum knee Flexion (c) Knee ROM (d) Hip ROM.

Figure 6.

Plot of average hip, knee and ankle joint angles between intact limb and prosthetic limb. Red (±SD) and blue (±SD) represent Intact and Prosthetic limbs respectively.

Figure 6.

Plot of average hip, knee and ankle joint angles between intact limb and prosthetic limb. Red (±SD) and blue (±SD) represent Intact and Prosthetic limbs respectively.

Table 1.

Participant demographics, prosthetic feet mass. In the study setting, participants used a solid SACH foot design for the current conventional device while the Mercer Universal Prostheses utilized the patented C-Shaped design (US patent number: US20110320010A1).

Table 1.

Participant demographics, prosthetic feet mass. In the study setting, participants used a solid SACH foot design for the current conventional device while the Mercer Universal Prostheses utilized the patented C-Shaped design (US patent number: US20110320010A1).

| Sex |

19 Male / 1 Female |

| Age |

60.4 ± 8.08 year |

| Height |

1.60 ± 0.07 m |

| Prosthetic Mass |

Conventional (CVP) |

1.55 ± 0.35 kg |

| Mercer Universal (MUP) |

1.31 ± 0.16 kg |

Table 2.

Spatiotemporal results for transtibial amputees walking with Conventional Prosthesis (CVP) and Mercer Universal Prosthesis (MUP).

Table 2.

Spatiotemporal results for transtibial amputees walking with Conventional Prosthesis (CVP) and Mercer Universal Prosthesis (MUP).

| |

Descriptive Statistics: Mean (Std) |

2 Factors Repeated ANOVA |

| MUP |

CVP |

p-value |

| Prosthetic |

Intact |

Prosthetic |

Intact |

Device*Limb |

Device |

Limb |

| Stride Time (s) |

1.26 (0.15) |

1.26 (0.15) |

1.24 (0.13) |

1.24 (0.13) |

0.171 |

0.086 |

0.641 |

| Stance Time (s) |

0.65 (0.12) |

0.61 (0.05) |

0.61 (0.09) |

0.63 (0.06) |

0.287 |

<0.001** |

<0.001** |

| Swing Time (s) |

0.71 (0.14) |

0.55 (0.03) |

0.67 (0.12) |

0.57 (0.03) |

0.785 |

0.003** |

<0.001** |

| Speed (m/s) |

0.68 (0.19) |

0.69 (0.20) |

0.72 (0.13) |

0.72 (0.13) |

0.590 |

0.378 |

0.276 |

| Stride Length (m) |

0.86 (0.21) |

0.86 (0.20) |

0.87 (0.10) |

0.89 (0.10) |

0.419 |

0.696 |

0.348 |

| Step Length (m) |

0.44 (0.12) |

0.45 (0.14) |

0.42 (0.10) |

0.48 (0.09) |

0.120 |

0.752 |

0.265 |

Table 3.

Kinematic results for transtibial amputees walking with Conventional (CVP) and Mercer Universal (MUP) prostheses.

Table 3.

Kinematic results for transtibial amputees walking with Conventional (CVP) and Mercer Universal (MUP) prostheses.

| |

Descriptive Statistics: Mean (Std) |

2 Factors Repeated ANOVA |

| MUP |

CVP |

p-value |

| Prosthetic |

Intact |

Prosthetic |

Intact |

Device*Limb |

Device |

Limb |

| Hip Extension (0) |

-18.6 (4.1) |

-17.1(3.) |

-16.1 (3.5) |

-14.8 (4.7) |

0.786 |

0.013* |

0.092 |

| Knee Extension (0) |

-0.4 (6.2) |

-1.4(4.5) |

-3.2 (5.8) |

-1.5 (7.2) |

0.459 |

0.301 |

0.230 |

| Ankle Plantarflex (0) |

0.3 (2.2) |

-17.6 (7.7) |

1.9 (2.9) |

-15.1 (7.0) |

0.435 |

0.011* |

<0.001** |

| Hip Flexion (0) |

26.9 (4.8) |

21.2 (4.9) |

26.03 (4.5) |

25.1 (6.1) |

0.013 |

0.039* |

0.008 |

| Knee Flexion (0) |

68.4 (9.3) |

62.0(5.8) |

63.2 (9.3) |

61.6 (6.3) |

0.025 |

0.016* |

0.067 |

| Ankle Dorsiflex (0) |

9.3 (4.1) |

12.8 (4.4) |

10.1 (6.2) |

13.7 (4.4) |

0.929 |

0.281 |

0.004* |

| Hip ROM (0) |

45.5 (5.3) |

38.2 (4.1) |

42.1 (6.1) |

39.8 (4.3) |

0.014* |

0.124 |

<0.001** |

| Knee ROM (0) |

68.8 (10.6) |

63.1 (5.6) |

66.3 (8.6) |

63.0 (6.5) |

0.033* |

0.024* |

0.168 |

| Ankle ROM (0) |

8.9 (3.5) |

30.3 (6.4) |

8.2 (7.7) |

28.8 (5.7) |

0.675 |

0.305 |

<0.001** |

Table 4.

Result of Gait Symmetry Index (GSI)– Kinematic (degrees).

Table 4.

Result of Gait Symmetry Index (GSI)– Kinematic (degrees).

| |

Mean GSI (SEM) |

Paired t-test

p < 0.05

|

| MUP |

CVP |

|

| Hip Extension (0) |

9.1 (4.9) |

11.1 (7.9) |

.780 |

| Knee Extension (0) |

18.7 (19.4) |

25.1 (23.0) |

.806 |

| Ankle Plantarflexion (0) |

-163.4 (46.0) |

-267.9 (61.3) |

.013* |

| Hip Flexion (0) |

24.2 (5.5) |

5.2 (5.) |

.012* |

| Knee Flexion (0) |

9.7 (2.8) |

1.7 (4.2) |

.026* |

| Ankle Dorsiflexion (0) |

-32.9 (10.9) |

-36.4 (12.2) |

.738 |

| Hip ROM (0) |

17.1 (2.9) |

5.1 (3.5) |

.014* |

| Knee ROM (0) |

7.8 (3.6) |

0.6 (4.0) |

.044* |

| Ankle ROM (0) |

-109.2 (6.5) |

-120.4 (10.3) |

.323 |

Table 5.

Result of Gait Symmetry Index (GSI) – Temporal and Spatial.

Table 5.

Result of Gait Symmetry Index (GSI) – Temporal and Spatial.

| |

Mean GSI (SEM) |

Paired t-test

p < 0.05

|

| MUP |

CVP |

Stride Duration (s)

Stance Duration (s)

Swing Duration (s)

Speed (m/s)

Stride Length (m)

Step Length (m)

|

0.5 (0.2)

-7.8 (1.4)

9.4 (1.6)

-1.2 (1.3)

-0.3 (1.4)

-0.8 (8.4) |

-0.2 (0.4)

-10.2 (1.8)

10.2 (1.8)

-0.7 (0.8)

-1.6 (0.9)

-14.9 (8.0) |

0.120

0.185

0.838

0.747

0.473

0.135 |