Submitted:

07 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

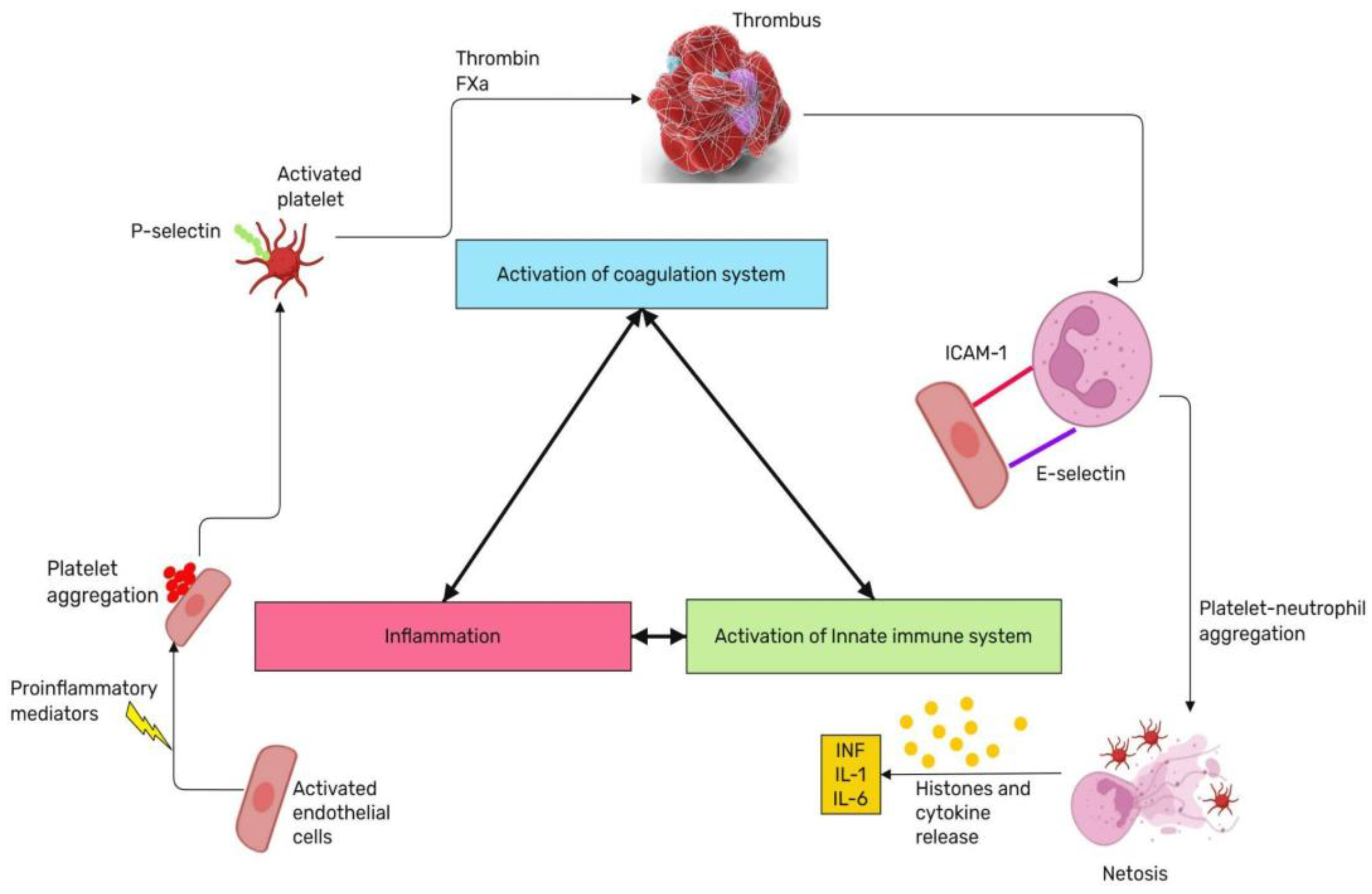

2. Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome, Thromboinflammation and Septic Shock in Fetuses and Neonates

2.1. Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome, SIRS

2.1.1. Diagnostic Criteria for SIRS

2.1.2. The Pathogenesis of SIRS

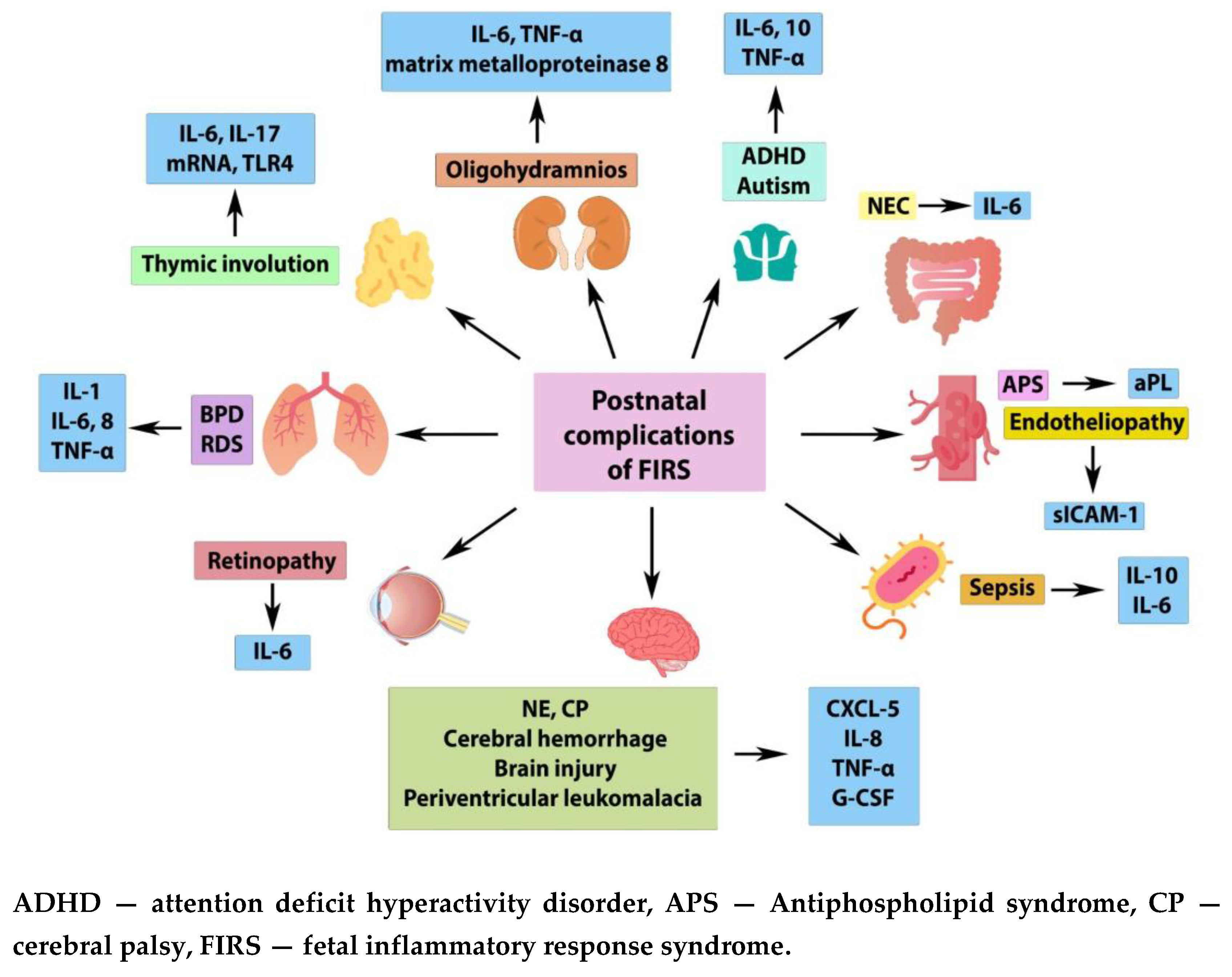

2.2. Fetal Inflammatory Response Syndrome, FIRS

2.3. Multiple Organ Failure in FIRS

2.4. Perinatal Aspects of Septic Shock

- 1)

- The initial phase, termed 'compensated shock', is characterized by the activation of neuroendocrine compensatory mechanisms [66]. The symptoms of stage 1 may include tachycardia, hypouresis, decreased tissue perfusion, and extremity coldness in the newborn.

- 2)

- The subsequent stage in the development of septic shock is uncompensated shock, which is characterized by symptoms of systemic hypotension and metabolic acidosis.

- 3)

- The final phase of septic shock development is irreversible shock, which is characterized by severe microcirculatory disorders and irreversible cellular damage, leading to necrosis and multi-organ failure.

2.5. Hemostasis in Newborns

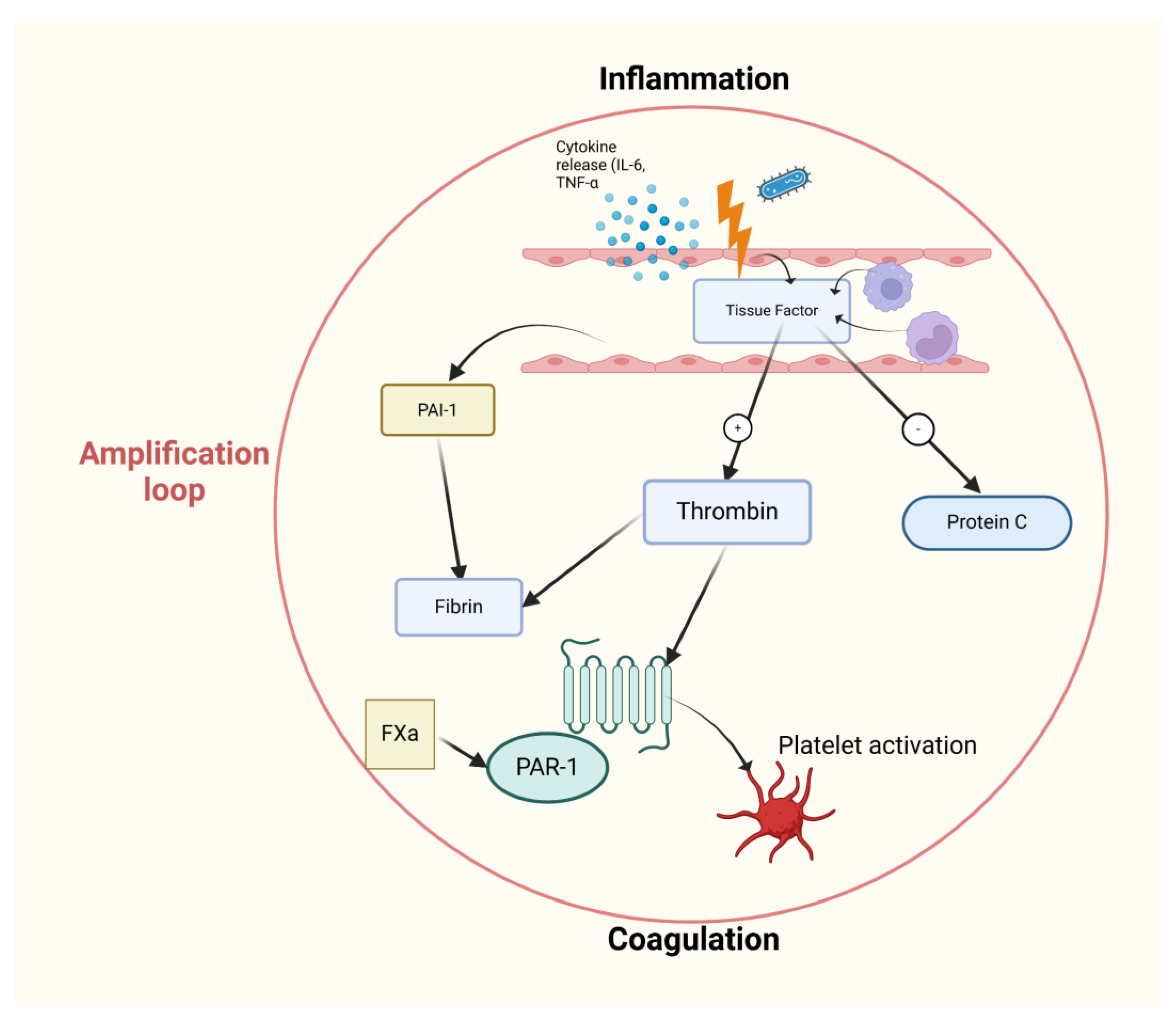

2.6. Alterations in Neonatal Hemostasis in Septic Shock

2.7. The Role of Convergent Model of Coagulation in Septic Shock

3. The Early Diagnosis and Treatment of Septic Shock

3.1. Antimicrobial Therapy

3.2. Infusion Therapy

3.3. Vasoactive Drugs

3.4. Corticosteroids

3.5. Antipyretic Therapy

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Linnikov V.I., Linnikov S.V., Makatsariya N.A. Sanarelli and Schwartzman, a historical background. Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproduction. 2022;16(3):324-327. (In Russ.). [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty RK, Burns B. Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome. 2023 May 29. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. PMID: 31613449.

- Wang Y, Dong H, Dong T, Zhao L, Fan W, Zhang Y, Yao W. Treatment of cytokine release syndrome-induced vascular endothelial injury using mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2024 May;479(5):1149-1164. Epub 2023 Jul 1. PMID: 37392343. [CrossRef]

- Beznoshchenko G.B. Sindrom sistemnogo vospalitel'nogo otveta v akusherskoj klinike: reshennye voprosy I nereshennye problemy // Rossijskij vestnik akushera-ginekologa. 2018. T.18, No4. S.6–10. [CrossRef]

- Sikora JP, Karawani J, Sobczak J. Neutrophils and the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS). Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Aug 30;24(17):13469. PMID: 37686271; PMCID: PMC10488036. [CrossRef]

- Medzidova MK, Tiutiunnik VL, Kan NE, Kurchakova TA, Kokoeva DN. The role of systemic inflammatory response syndrome in preterm labour development. Russian Journal of Human Reproduction. 2016;22(2):116-120. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.17116/repro2016222116-120.

- De Felice C, De Capua B, Costantini D, Martufi C, Toti P, Tonni G, Laurini R, Giannuzzi A, Latini G. Recurrent otitis media with effusion in preterm infants with histologic chorioamnionitis--a 3 years follow-up study. Early Hum Dev. 2008 Oct;84(10):667-71. Epub 2008 Aug 29. PMID: 18760552. [CrossRef]

- Karrow NA. Activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and autonomic nervous system during inflammation and altered programming of the neuroendocrine-immune axis during fetal and neonatal development: lessons learned from the model inflammagen, lipopolysaccharide. Brain Behav Immun. 2006 Mar;20(2):144-58. Epub 2005 Jul 14. PMID: 16023324. [CrossRef]

- Para R, Romero R, Miller D, Galaz J, Done B, Peyvandipour A, Gershater M, Tao L, Motomura K, Ruden DM, Isherwood J, Jung E, Kanninen T, Pique-Regi R, Tarca AL, Gomez-Lopez N. The Distinct Immune Nature of the Fetal Inflammatory Response Syndrome Type I and Type II. Immunohorizons. 2021 Sep 14;5(9):735-751. PMID: 34521696; PMCID: PMC9394103. [CrossRef]

- Glavina-Durdov M, Springer O, Capkun V, Saratlija-Novaković Z, Rozić D, Barle M. The grade of acute thymus involution in neonates correlates with the duration of acute illness and with the percentage of lymphocytes in peripheral blood smear. Pathological study. Biol Neonate. 2003;83(4):229-34. PMID: 12743450. [CrossRef]

- Straňák Zbyněk, Berka Ivan, Širc Jan, Urbánek Jan, Feyereisl Jaroslav, Korček Peter. Role of umbilical interleukin-6, procalcitonin and C-reactive protein measurement in the diagnosis of fetal inflammatory response syndrome. Ceska Gynekol. 2021;86(2):80-85. English. PMID: 34020553. [CrossRef]

- Persson G, Jørgensen N, Nilsson LL, Andersen LHJ, Hviid TVF. A role for both HLA-F and HLA-G in reproduction and during pregnancy? Hum Immunol. 2020 Apr;81(4):127-133. Epub 2019 Sep 24. PMID: 31558330. [CrossRef]

- Nomiyama M, Nakagawa T, Yamasaki F, Hisamoto N, Yamashita N, Harai A, Gondo K, Ikeda M, Tsuda S, Ishimatsu M, Oshima Y, Ono T, Kozuma Y, Tsumura K. Contribution of Fetal Inflammatory Response Syndrome (FIRS) with or without Maternal-Fetal Inflammation in The Placenta to Increased Risk of Respiratory and Other Complications in Preterm Neonates. Biomedicines. 2023 Feb 18;11(2):611. PMID: 36831147; PMCID: PMC9953376. [CrossRef]

- Romero R, Savasan ZA, Chaiworapongsa T, Berry SM, Kusanovic JP, Hassan SS, Yoon BH, Edwin S, Mazor M. Hematologic profile of the fetus with systemic inflammatory response syndrome. J Perinat Med. 2011 Sep 30;40(1):19-32. PMID: 21957997; PMCID: PMC3380620. [CrossRef]

- Ead JK, Armstrong DG. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor: Conductor of the wound healing orchestra? Int Wound J. 2023 Apr;20(4):1229-1234. Epub 2023 Jan 12. PMID: 36632762; PMCID: PMC10031218. [CrossRef]

- Zurochka A.V., Zurochka V.A., Dobrynina M.A., Gritsenko V.A. Immunobiological properties of granulocytemacrophage colony-stimulating factor and synthetic peptides of his active center. Medical Immunology (Russia). 2021;23(5):1031-1054. (In Russ.). [CrossRef]

- Chaiworapongsa T, Romero R, Berry SM, Hassan SS, Yoon BH, Edwin S, Mazor M. The role of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in the neutrophilia observed in the fetal inflammatory response syndrome. J Perinat Med. 2011 Nov;39(6):653-66. Epub 2011 Jul 30. PMID: 21801092; PMCID: PMC3382056. [CrossRef]

- Leikin E, Garry D, Visintainer P, Verma U, Tejani N. Correlation of neonatal nucleated red blood cell counts in preterm infants with histologic chorioamnionitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997 Jul;177(1):27-30. PMID: 9240578. [CrossRef]

- Mandel D, Oron T, Mimouni GS, Littner Y, Dollberg S, Mimouni FB. The effect of prolonged rupture of membranes on circulating neonatal nucleated red blood cells. J Perinatol. 2005 Nov;25(11):690-3. PMID: 16222345. [CrossRef]

- Romero R, Soto E, Berry SM, Hassan SS, Kusanovic JP, Yoon BH, Edwin S, Mazor M, Chaiworapongsa T. Blood pH and gases in fetuses in preterm labor with and without systemic inflammatory response syndrome. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012 Jul;25(7):1160-70. Epub 2011 Dec 20. PMID: 21988103; PMCID: PMC3383905. [CrossRef]

- Zaharie GC, Drugan T, Crivii C, Muresan D, Zaharie A, Hășmășanu MG, Zaharie F, Matyas M. Postpartum assessment of fetal inflammatory response syndrome in a preterm population with premature rupture of membranes: A Romanian study. Exp Ther Med. 2021 Dec;22(6):1427. Epub 2021 Oct 11. PMID: 34707708; PMCID: PMC8543235. [CrossRef]

- Kallapur SG, Willet KE, Jobe AH, Ikegami M, Bachurski CJ. Intra-amniotic endotoxin: chorioamnionitis precedes lung maturation in preterm lambs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001 Mar;280(3):L527-36. PMID: 11159037. [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe A, Lisonkova S, Sabr Y, Stritzke A, Joseph KS. Neonatal respiratory morbidity following exposure to chorioamnionitis. BMC Pediatr. 2017 May 17;17(1):128. PMID: 28514958; PMCID: PMC5436447. [CrossRef]

- Plakkal N, Soraisham AS, Trevenen C, Freiheit EA, Sauve R. Histological chorioamnionitis and bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a retrospective cohort study. J Perinatol. 2013 Jun;33(6):441-5. Epub 2012 Dec 13. PMID: 23238570. [CrossRef]

- Yoon BH, Romero R, Kim KS, Park JS, Ki SH, Kim BI, Jun JK. A systemic fetal inflammatory response and the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Oct;181(4):773-9. PMID: 10521727. [CrossRef]

- Sarno L, Della Corte L, Saccone G, Sirico A, Raimondi F, Zullo F, Guida M, Martinelli P, Maruotti GM. Histological chorioamnionitis and risk of pulmonary complications in preterm births: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021 Nov;34(22):3803-3812. Epub 2019 Nov 13. PMID: 31722581. [CrossRef]

- Wu J, Wang Y, Zhao A, Wang Z. Lung Ultrasound for the Diagnosis of Neonatal Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Meta-analysis. Ultrasound Q. 2020 Jun;36(2):102-110. PMID: 32511203; PMCID: PMC7289125. [CrossRef]

- Dessardo NS, Dessardo S, Mustać E, Banac S, Petrović O, Peter B. Chronic lung disease of prematurity and early childhood wheezing: is foetal inflammatory response syndrome to blame? Early Hum Dev. 2014 Sep;90(9):493-9. Epub 2014 Jul 21. PMID: 25051540. [CrossRef]

- Yap V, Perlman JM. Mechanisms of brain injury in newborn infants associated with the fetal inflammatory response syndrome. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020 Aug;25(4):101110. Epub 2020 Apr 9. PMID: 32303463. [CrossRef]

- Muraskas JK, Kelly AF, Nash MS, Goodman JR, Morrison JC. The role of fetal inflammatory response syndrome and fetal anemia in nonpreventable term neonatal encephalopathy. J Perinatol. 2016 May;36(5):362-5. Epub 2016 Jan 21. PMID: 26796124. [CrossRef]

- Yoon BH, Romero R, Kim CJ, Koo JN, Choe G, Syn HC, Chi JG. High expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6 in periventricular leukomalacia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997 Aug;177(2):406-11. PMID: 9290459. [CrossRef]

- Kadhim H, Tabarki B, Verellen G, De Prez C, Rona AM, Sébire G. Inflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of periventricular leukomalacia. Neurology. 2001 May 22;56(10):1278-84. PMID: 11376173. [CrossRef]

- Stolp HB, Dziegielewska KM, Ek CJ, Habgood MD, Lane MA, Potter AM, Saunders NR. Breakdown of the blood-brain barrier to proteins in white matter of the developing brain following systemic inflammation. Cell Tissue Res. 2005 Jun;320(3):369-78. Epub 2005 Apr 22. PMID: 15846513. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Jyoti A, Balakrishnan B, Williams M, Singh S, Chugani DC, Kannan S. Trajectory of inflammatory and microglial activation markers in the postnatal rabbit brain following intrauterine endotoxin exposure. Neurobiol Dis. 2018 Mar;111:153-162. Epub 2017 Dec 21. PMID: 29274431; PMCID: PMC6082145. [CrossRef]

- Giovannini E, Bonasoni MP, Pascali JP, Giorgetti A, Pelletti G, Gargano G, Pelotti S, Fais P. Infection Induced Fetal Inflammatory Response Syndrome (FIRS): State-of- the-Art and Medico-Legal Implications—A Narrative Review. Microorganisms. 2023; 11(4):1010. [CrossRef]

- Goncalves LF, Cornejo P, Towbin R. Neuroimaging findings associated with the fetal inflammatory response syndrome. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020 Aug;25(4):101143. Epub 2020 Aug 3. PMID: 32800654. [CrossRef]

- Boog G. Asphyxie périnatale et infirmité motrice d’origine cérébrale (I- Le diagnostic). Gynécologie Obstétrique & Fertilité 2010; 38: 261–277.

- Song JS, Woo SJ, Park KH, Kim H, Lee KN, Kim YM. Association of inflammatory and angiogenic biomarkers in maternal plasma with retinopathy of prematurity in preterm infants. Eye (Lond). 2023 Jun;37(9):1802-1809. Epub 2022 Sep 15. PMID: 36109603; PMCID: PMC10275990. [CrossRef]

- Park YJ, Woo SJ, Kim YM, Hong S, Lee YE, Park KH. Immune and Inflammatory Proteins in Cord Blood as Predictive Biomarkers of Retinopathy of Prematurity in Preterm Infants. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019 Sep 3;60(12):3813-3820. PMID: 31525777. [CrossRef]

- Gibson B, Goodfriend E, Zhong Y, Melhem NM. Fetal inflammatory response and risk for psychiatric disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2023 Jun 24;13(1):224. PMID: 37355708; PMCID: PMC10290670. [CrossRef]

- Yoon BH, Kim YA, Romero R, Kim JC, Park KH, Kim MH, Park JS. Association of oligohydramnios in women with preterm premature rupture of membranes with an inflammatory response in fetal, amniotic, and maternal compartments. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Oct;181(4):784-8. PMID: 10521729. [CrossRef]

- Lee SE, Romero R, Lee SM, Yoon BH. Amniotic fluid volume in intra-amniotic inflammation with and without culture-proven amniotic fluid infection in preterm premature rupture of membranes. J Perinat Med. 2010;38(1):39-44. PMID: 19708825; PMCID: PMC2887661. [CrossRef]

- Azpurua H, Dulay AT, Buhimschi IA, Bahtiyar MO, Funai E, Abdel-Razeq SS, Luo G, Bhandari V, Copel JA, Buhimschi CS. Fetal renal artery impedance as assessed by Doppler ultrasound in pregnancies complicated by intraamniotic inflammation and preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Feb;200(2):203.e1-11. PMID: 19185102; PMCID: PMC3791328. [CrossRef]

- Galinsky R, Moss TJ, Gubhaju L, Hooper SB, Black MJ, Polglase GR. Effect of intra-amniotic lipopolysaccharide on nephron number in preterm fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011 Aug;301(2):F280-5. Epub 2011 May 18. PMID: 21593183. [CrossRef]

- Stantsidou A, Pagonopoulou O, Deftereou T. Effects of chorioamnionitis in fetal renal glomeruli. Hippokratia. 2021 Apr-Jun;25(2):98. PMID: 35937516; PMCID: PMC9347347.

- Muk T, Jiang PP, Stensballe A, Skovgaard K, Sangild PT, Nguyen DN. Prenatal Endotoxin Exposure Induces Fetal and Neonatal Renal Inflammation via Innate and Th1 Immune Activation in Preterm Pigs. Front Immunol. 2020 Sep 30;11:565484. PMID: 33193334; PMCID: PMC7643587. [CrossRef]

- Kuypers E, Wolfs TG, Collins JJ, Jellema RK, Newnham JP, Kemp MW, Kallapur SG, Jobe AH, Kramer BW. Intraamniotic lipopolysaccharide exposure changes cell populations and structure of the ovine fetal thymus. Reprod Sci. 2013 Aug;20(8):946-56. Epub 2013 Jan 11. PMID: 23314960; PMCID: PMC3702021. [CrossRef]

- Luciano AA, Yu H, Jackson LW, Wolfe LA, Bernstein HB. Preterm labor and chorioamnionitis are associated with neonatal T cell activation. PLoS One. 2011 Feb 8;6(2):e16698. PMID: 21347427; PMCID: PMC3035646. [CrossRef]

- Melville JM, Bischof RJ, Meeusen EN, Westover AJ, Moss TJ. Changes in fetal thymic immune cell populations in a sheep model of intrauterine inflammation. Reprod Sci. 2012 Jul;19(7):740-7. Epub 2012 Mar 14. PMID: 22421448. [CrossRef]

- Kramer BW, Moss TJ, Willet KE, Newnham JP, Sly PD, Kallapur SG, Ikegami M, Jobe AH. Dose and time response after intraamniotic endotoxin in preterm lambs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001 Sep 15;164(6):982-8. PMID: 11587983. [CrossRef]

- Kuypers E, Willems MG, Jellema RK, Kemp MW, Newnham JP, Delhaas T, Kallapur SG, Jobe AH, Wolfs TG, Kramer BW. Responses of the spleen to intraamniotic lipopolysaccharide exposure in fetal sheep. Pediatr Res. 2015 Jan;77(1-1):29-35. Epub 2014 Oct 6. PMID: 25285474. [CrossRef]

- Musilova I, Kacerovsky M, Hornychova H, Kostal M, Jacobsson B. Pulsation of the fetal splenic vein--a potential ultrasound marker of histological chorioamnionitis and funisitis in women with preterm prelabor rupture of membranes. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012 Sep;91(9):1119-23. PMID: 22574855. [CrossRef]

- Yan X, Managlia E, Tan XD, De Plaen IG. Prenatal inflammation impairs intestinal microvascular development through a TNF-dependent mechanism and predisposes newborn mice to necrotizing enterocolitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2019 Jul 1;317(1):G57-G66. Epub 2019 May 24. PMID: 31125264; PMCID: PMC6689733. [CrossRef]

- Razak A, Malhotra A. Fetal inflammatory response spectrum: mapping its impact on severity of necrotising enterocolitis. Pediatr Res. 2024 Apr;95(5):1179-1180. Epub 2023 Dec 16. PMID: 38104186. [CrossRef]

- Bieghs V, Vlassaks E, Custers A, van Gorp PJ, Gijbels MJ, Bast A, Bekers O, Zimmermann LJ, Lütjohann D, Voncken JW, Gavilanes AW, Kramer BW, Shiri-Sverdlov R. Chorioamnionitis induced hepatic inflammation and disturbed lipid metabolism in fetal sheep. Pediatr Res. 2010 Dec;68(6):466-72. PMID: 20717072. [CrossRef]

- Heymans C, den Dulk M, Lenaerts K, Heij LR, de Lange IH, Hadfoune M, van Heugten C, Kramer BW, Jobe AH, Saito M, Kemp MW, Wolfs TGAM, van Gemert WG. Chorioamnionitis induces hepatic inflammation and time-dependent changes of the enterohepatic circulation in the ovine fetus. Sci Rep. 2021 May 14;11(1):10331. PMID: 33990635; PMCID: PMC8121927. [CrossRef]

- Sergeeva V.A., Shabalov N.P., Aleksandrovich Yu.S., and Nesterenko S.N. \"Predopredelyaet li fetal'nyj vospalitel'nyj otvet oslozhnyonnoe techenie rannego neonatal'nogo perioda?\" Bajkal'skij medicinskij zhurnal, vol. 93, no. 2, 2010, pp. 75-80.

- Watterberg KL, Demers LM, Scott SM, Murphy S. Chorioamnionitis and early lung inflammation in infants in whom bronchopulmonary dysplasia develops. Pediatrics. 1996 Feb;97(2):210-5. PMID: 8584379.

- Volpe JJ. Postnatal sepsis, necrotizing entercolitis, and the critical role of systemic inflammation in white matter injury in premature infants. J Pediatr. 2008 Aug;153(2):160-3. PMID: 18639727; PMCID: PMC2593633. [CrossRef]

- Eloundou SN, Lee J, Wu D, Lei J, Feller MC, Ozen M, Zhu Y, Hwang M, Jia B, Xie H, Clemens JL, McLane MW, AlSaggaf S, Nair N, Wills-Karp M, Wang X, Graham EM, Baschat A, Burd I. Placental malperfusion in response to intrauterine inflammation and its connection to fetal sequelae. PLoS One. 2019 Apr 3;14(4):e0214951. PMID: 30943260; PMCID: PMC6447225. [CrossRef]

- Luciano AA, Arbona-Ramirez IM, Ruiz R, Llorens-Bonilla BJ, Martinez-Lopez DG, Funderburg N, Dorsey MJ. Alterations in regulatory T cell subpopulations seen in preterm infants. PLoS One. 2014 May 5;9(5):e95867. PMID: 24796788; PMCID: PMC4010410. [CrossRef]

- Muraskas J, Astrug L, Amin S. FIRS: Neonatal considerations. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020 Aug;25(4):101142. Epub 2020 Aug 26. PMID: 32912755. [CrossRef]

- Agyeman PKA, Schlapbach LJ, Giannoni E, Stocker M, Posfay-Barbe KM, Heininger U, Schindler M, Korten I, Konetzny G, Niederer-Loher A, Kahlert CR, Donas A, Leone A, Hasters P, Relly C, Baer W, Kuehni CE, Aebi C, Berger C; Swiss Pediatric Sepsis Study. Epidemiology of blood culture-proven bacterial sepsis in children in Switzerland: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2017 Oct;1(2):124-133. Epub 2017 Jul 21. PMID: 30169202. [CrossRef]

- Wynn JL, Wong HR. Pathophysiology and treatment of septic shock in neonates. Clin Perinatol. 2010 Jun;37(2):439-79. PMID: 20569817; PMCID: PMC2891980. [CrossRef]

- Samsygina G.A. \"Sepsis i septicheskij shok u novorozhdennyh detej\" Pediatriya. Zhurnal im. G. N. Speranskogo, vol. 87, no. 1, 2009, pp. 120-126.

- Spaggiari V, Passini E, Crestani S, Roversi MF, Bedetti L, Rossi K, Lucaccioni L, Baraldi C, Della Casa Muttini E, Lugli L, Iughetti L, Berardi A. Neonatal septic shock, a focus on first line interventions. Acta Biomed. 2022 Jul 1;93(3):e2022141. PMID: 35775767; PMCID: PMC9335427. [CrossRef]

- Schorr CA, Zanotti S, Dellinger RP. Severe sepsis and septic shock: management and performance improvement. Virulence. 2014 Jan 1;5(1):190-9. Epub 2013 Dec 11. PMID: 24335487; PMCID: PMC3916373. [CrossRef]

- Silveira Rde C, Giacomini C, Procianoy RS. Neonatal sepsis and septic shock: concepts update and review. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2010 Sep;22(3):280-90. English, Portuguese. PMID: 25302436.

- Khizroeva J, Makatsariya A, Vorobev A, Bitsadze V, Elalamy I, Lazarchuk A, Salnikova P, Einullaeva S, Solopova A, Tretykova M, Antonova A, Mashkova T, Grigoreva K, Kvaratskheliia M, Yakubova F, Degtyareva N, Tsibizova V, Gashimova N, Blbulyan D. The Hemostatic System in Newborns and the Risk of Neonatal Thrombosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Sep 8;24(18):13864. PMID: 37762167; PMCID: PMC10530883. [CrossRef]

- Andrew M, Vegh P, Johnston M, Bowker J, Ofosu F, Mitchell L. Maturation of the hemostatic system during childhood. Blood. 1992 Oct 15;80(8):1998-2005. PMID: 1391957. [CrossRef]

- Wiedmeier SE, Henry E, Sola-Visner MC, Christensen RD. Platelet reference ranges for neonates, defined using data from over 47,000 patients in a multihospital healthcare system. J Perinatol. 2009 Feb;29(2):130-6. Epub 2008 Sep 25. PMID: 18818663. [CrossRef]

- Sillers L, Van Slambrouck C, Lapping-Carr G. Neonatal Thrombocytopenia: Etiology and Diagnosis. Pediatr Ann. 2015 Jul;44(7):e175-80. PMID: 26171707; PMCID: PMC6107300. [CrossRef]

- Bednarek FJ, Bean S, Barnard MR, Frelinger AL, Michelson AD. The platelet hyporeactivity of extremely low birth weight neonates is age-dependent. Thromb Res. 2009 May;124(1):42-5. Epub 2008 Nov 20. PMID: 19026437. [CrossRef]

- Bitsadze V.O., Sukontseva T.A., Akinshina S.V., Sulina Ya.Yu., Khizroeva J.Kh., Tretyakova M.V., Sultangadzhieva Kh.G., Ungiadze J.Yu., Samburova N.V., Grigoreva K.N., Tsibizova V.I., Shkoda A.S., Blinov D.V., Makatsariya A.D. Septic shock. Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproduction. 2020;14(3):314-326. (In Russ.). [CrossRef]

- Mal'ceva L.A., and Bazilenko D.V. \"Patogenez tyazhelogo sepsisa i septicheskogo shoka: analiz sovremennyh koncepcij\" Medicina neotlozhnyh sostoyanij, no. 7 (70), 2015, pp. 35-40.

- Bitsadze V.O., Khizroeva J.K., Makatsariya A.D., Slukhanchuk E.V., Tretyakova M.V., Rizzo G., Gris J.R., Elalamy I., Serov V.N., Shkoda A.S., Samburova N.V. COVID-19, septic shock and syndrome of disseminated intravascular coagulation syndrome. Part 1 // Annals of the Russian academy of medical sciences. - 2020. - Vol. 75. - N. 2. - P. 118-128. [CrossRef]

- Levi M, van der Poll T. Coagulation and sepsis. Thromb Res. 2017 Jan;149:38-44. Epub 2016 Nov 19. PMID: 27886531. [CrossRef]

- Green J, Doughty L, Kaplan SS, Sasser H, Carcillo JA. The tissue factor and plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 response in pediatric sepsis-induced multiple organ failure. Thromb Haemost. 2002 Feb;87(2):218-23. PMID: 11858480.

- Asakura H, Ontachi Y, Mizutani T, Kato M, Ito T, Saito M, Morishita E, Yamazaki M, Suga Y, Miyamoto KI, Nakao S. Depressed plasma activity of plasminogen or alpha2 plasmin inhibitor is not due to consumption coagulopathy in septic patients with disseminated intravascular coagulation. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2001 Jun;12(4):275-81. PMID: 11460011. [CrossRef]

- Dempfle CE. Das TAFI-System. Die neue Rolle der Fibrinolyse [The TAFI system. The new role of fibrinolysis]. Hamostaseologie. 2007 Sep;27(4):278-81. German. PMID: 17938767.

- Stief TW, Ijagha O, Weiste B, Herzum I, Renz H, Max M. Analysis of hemostasis alterations in sepsis. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2007 Mar;18(2):179-86. PMID: 17287636. [CrossRef]

- Gando S. Role of fibrinolysis in sepsis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2013 Jun;39(4):392-9. Epub 2013 Feb 27. PMID: 23446914. [CrossRef]

- Willemse JL, Heylen E, Nesheim ME, Hendriks DF. Carboxypeptidase U (TAFIa): a new drug target for fibrinolytic therapy? J Thromb Haemost. 2009 Dec;7(12):1962-71. Epub 2009 Aug 28. PMID: 19719827; PMCID: PMC3170991. [CrossRef]

- Emonts M, de Bruijne EL, Guimarães AH, Declerck PJ, Leebeek FW, de Maat MP, Rijken DC, Hazelzet JA, Gils A. Thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor is associated with severity and outcome of severe meningococcal infection in children. J Thromb Haemost. 2008 Feb;6(2):268-76. Epub 2007 Nov 15. PMID: 18021301. [CrossRef]

- Prodeus A.P., Ustinova M.V., Korsunskiy A.A., Goncharov A.G. New aspects of sepsis and septic shock pathogenesis in children. The complement system as target for an effective therapy // Russian Journal of Infection and Immunity = Infektsiya i immunitet, 2018, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 19–24. [CrossRef]

- Hazelzet JAde Groot R, van Mierlo G, Joosten KFM, van der Voort E, Eerenberg A, Suur MH, Hop WCJ, Hack CE. 1998. Complement Activation in Relation to Capillary Leakage in Children with Septic Shock and Purpura. Infect Immun 66: https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.66.11.5350-5356.1998.

- Kelwick R, Desanlis I, Wheeler GN, Edwards DR. The ADAMTS (A Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase with Thrombospondin motifs) family. Genome Biol. 2015 May 30;16(1):113. PMID: 26025392; PMCID: PMC4448532. [CrossRef]

- Levi M, Scully M, Singer M. The role of ADAMTS-13 in the coagulopathy of sepsis. J Thromb Haemost. 2018 Apr;16(4):646-651. Epub 2018 Feb 2. PMID: 29337416. [CrossRef]

- Levi M, Opal SM. Coagulation abnormalities in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2006;10(4):222. PMID: 16879728; PMCID: PMC1750988. [CrossRef]

- Pillai VG, Bao J, Zander CB, McDaniel JK, Chetty PS, Seeholzer SH, Bdeir K, Cines DB, Zheng XL. Human neutrophil peptides inhibit cleavage of von Willebrand factor by ADAMTS13: a potential link of inflammation to TTP. Blood. 2016 Jul 7;128(1):110-9. Epub 2016 May 13. PMID: 27207796; PMCID: PMC4937355. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Chung DW. Inflammation, von Willebrand factor, and ADAMTS13. Blood. 2018 Jul 12;132(2):141-147. Epub 2018 Jun 4. PMID: 29866815; PMCID: PMC6043979. [CrossRef]

- Peigne V, Azoulay E, Coquet I, Mariotte E, Darmon M, Legendre P, Adoui N, Marfaing-Koka A, Wolf M, Schlemmer B, Veyradier A. The prognostic value of ADAMTS13 (a disintegrin and metalloprotease with thrombospondin type 1 repeats, member 13) deficiency in septic shock patients involves interleukin-6 and is not dependent on disseminated intravascular coagulation. Crit Care. 2013 Nov 18;17(6):R273. PMID: 24238574; PMCID: PMC4056532. [CrossRef]

- Habe K, Wada H, Ito-Habe N, Hatada T, Matsumoto T, Ohishi K, Maruyama K, Imai H, Mizutani H, Nobori T. Plasma ADAMTS13, von Willebrand factor (VWF) and VWF propeptide profiles in patients with DIC and related diseases. Thromb Res. 2012 May;129(5):598-602. Epub 2011 Nov 8. PMID: 22070827. [CrossRef]

- Ono T, Mimuro J, Madoiwa S, Soejima K, Kashiwakura Y, Ishiwata A, Takano K, Ohmori T, Sakata Y. Severe secondary deficiency of von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease (ADAMTS13) in patients with sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation: its correlation with development of renal failure. Blood. 2006 Jan 15;107(2):528-34. Epub 2005 Sep 27. PMID: 16189276. [CrossRef]

- Schwameis M, Schörgenhofer C, Assinger A, Steiner MM, Jilma B. VWF excess and ADAMTS13 deficiency: a unifying pathomechanism linking inflammation to thrombosis in DIC, malaria, and TTP. Thromb Haemost. 2015 Apr;113(4):708-18. Epub 2014 Dec 11. PMID: 25503977; PMCID: PMC4745134. [CrossRef]

- Emmer BT, Ginsburg D, Desch KC. Von Willebrand Factor and ADAMTS13: Too Much or Too Little of a Good Thing? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016 Dec;36(12):2281-2282. PMID: 27879275; PMCID: PMC5127281. [CrossRef]

- Sonneveld MA, Franco OH, Ikram MA, Hofman A, Kavousi M, de Maat MP, Leebeek FW. Von Willebrand Factor, ADAMTS13, and the Risk of Mortality: The Rotterdam Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016 Dec;36(12):2446-2451. Epub 2016 Oct 13. PMID: 27737864. [CrossRef]

- Papadogeorgou P, Boutsikou T, Boutsikou M, Pergantou E, Mantzou A, Papassotiriou I, Iliodromiti Z, Sokou R, Bouza E, Politou M, Iacovidou N, Valsami S. A Global Assessment of Coagulation Profile and a Novel Insight into Adamts-13 Implication in Neonatal Sepsis. Biology (Basel). 2023 Sep 26;12(10):1281. PMID: 37886991; PMCID: PMC10604288. [CrossRef]

- Kansas GS. Selectins and their ligands: current concepts and controversies. Blood. 1996 Nov 1;88(9):3259-87. PMID: 8896391. [CrossRef]

- Martinod K, Deppermann C. Immunothrombosis and thromboinflammation in host defense and disease. Platelets. 2021 Apr 3;32(3):314-324. Epub 2020 Sep 8. PMID: 32896192. [CrossRef]

- Rossaint J, Margraf A, Zarbock A. Role of Platelets in Leukocyte Recruitment and Resolution of Inflammation. Front Immunol. 2018 Nov 20;9:2712. PMID: 30515177; PMCID: PMC6255980. [CrossRef]

- Iba T, Levy JH. Inflammation and thrombosis: roles of neutrophils, platelets and endothelial cells and their interactions in thrombus formation during sepsis. J Thromb Haemost. 2018 Feb;16(2):231-241. Epub 2017 Dec 21. PMID: 29193703. [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein Y, Shenkman B, Sirota L, Vishne TH, Dardik R, Varon D, Linder N. Whole blood platelet deposition on extracellular matrix under flow conditions in preterm neonatal sepsis. Eur J Pediatr. 2002 May;161(5):270-4. Epub 2002 Mar 16. PMID: 12012223. [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi K, Berger A, Langgartner M, Prusa AR, Hayde M, Herkner K, Pollak A, Spittler A, Forster-Waldl E. Immaturity of infection control in preterm and term newborns is associated with impaired toll-like receptor signaling. J Infect Dis. 2007 Jan 15;195(2):296-302. Epub 2006 Dec 1. PMID: 17191175. [CrossRef]

- Sitaru AG, Speer CP, Holzhauer S, Obergfell A, Walter U, Grossmann R. Chorioamnionitis is associated with increased CD40L expression on cord blood platelets. Thromb Haemost. 2005 Dec;94(6):1219-23. PMID: 16411397. [CrossRef]

- Aloui C, Prigent A, Sut C, Tariket S, Hamzeh-Cognasse H, Pozzetto B, Richard Y, Cognasse F, Laradi S, Garraud O. The signaling role of CD40 ligand in platelet biology and in platelet component transfusion. Int J Mol Sci. 2014 Dec 3;15(12):22342-64. PMID: 25479079; PMCID: PMC4284712. [CrossRef]

- Andryukov B.G., Bogdanova V.D., Lyapun I.N. PHENOTYPIC HETEROGENEITY OF NEUTROPHILS: NEW ANTIMICROBIC CHARACTERISTICS AND DIAGNOSTIC TECHNOLOGIES. Russian journal of hematology and transfusiology. 2019;64(2):211-221. (In Russ.). [CrossRef]

- Kaplan MJ, Radic M. Neutrophil extracellular traps: double-edged swords of innate immunity. J Immunol. 2012 Sep 15;189(6):2689-95. PMID: 22956760; PMCID: PMC3439169. [CrossRef]

- Fuchs TA, Brill A, Duerschmied D, Schatzberg D, Monestier M, Myers DD Jr, Wrobleski SK, Wakefield TW, Hartwig JH, Wagner DD. Extracellular DNA traps promote thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Sep 7;107(36):15880-5. Epub 2010 Aug 23. PMID: 20798043; PMCID: PMC2936604. [CrossRef]

- Hoppenbrouwers T, Boeddha NP, Ekinci E, Emonts M, Hazelzet JA, Driessen GJ, de Maat MP. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Children With Meningococcal Sepsis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018 Jun;19(6):e286-e291. PMID: 29432403. [CrossRef]

- McDonald B, Davis RP, Kim SJ, Tse M, Esmon CT, Kolaczkowska E, Jenne CN. Platelets and neutrophil extracellular traps collaborate to promote intravascular coagulation during sepsis in mice. Blood. 2017 Mar 9;129(10):1357-1367. Epub 2017 Jan 10. Erratum in: Blood. 2022 Feb 10;139(6):952. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021014436. PMID: 28073784; PMCID: PMC5345735. [CrossRef]

- Fatmi A, Saadi W, Beltrán-García J, García-Giménez JL, Pallardó FV. The Endothelial Glycocalyx and Neonatal Sepsis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Dec 26;24(1):364. PMID: 36613805; PMCID: PMC9820255. [CrossRef]

- Dreschers S, Platen C, Ludwig A, Gille C, Köstlin N, Orlikowsky TW. Metalloproteinases TACE and MMP-9 Differentially Regulate Death Factors on Adult and Neonatal Monocytes After Infection with Escherichia coli. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Mar 20;20(6):1399. PMID: 30897723; PMCID: PMC6471605. [CrossRef]

- He Y, Du WX, Jiang HY, Ai Q, Feng J, Liu Z, Yu JL. Multiplex Cytokine Profiling Identifies Interleukin-27 as a Novel Biomarker For Neonatal Early Onset Sepsis. Shock. 2017 Feb;47(2):140-147. PMID: 27648693. [CrossRef]

- Formosa A, Turgeon P, Dos Santos CC. Role of miRNA dysregulation in sepsis. Mol Med. 2022 Aug 19;28(1):99. PMID: 35986237; PMCID: PMC9389495. [CrossRef]

- Bindayna K. MicroRNA as Sepsis Biomarkers: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Jun 12;25(12):6476. PMID: 38928179; PMCID: PMC11204033. [CrossRef]

- Zheng X, Zhang Y, Lin S, Li Y, Hua Y, Zhou K. Diagnostic significance of microRNAs in sepsis. PLoS One. 2023 Feb 22;18(2):e0279726. PMID: 36812225; PMCID: PMC9946237. [CrossRef]

- Yao J, Lui KY, Hu X, Liu E, Zhang T, Tong L, Xu J, Huang F, Zhu Y, Lu M, Cai C. Circulating microRNAs as novel diagnostic biomarkers and prognostic predictors for septic patients. Infect Genet Evol. 2021 Nov;95:105082. Epub 2021 Sep 11. PMID: 34520874. [CrossRef]

- Yong J, Toh CH. The convergent model of coagulation. J Thromb Haemost. 2024 Aug;22(8):2140-2146. Epub 2024 May 28. PMID: 38815754. [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm G, Mertowska P, Mertowski S, Przysucha A, Strużyna J, Grywalska E, Torres K. The Crossroads of the Coagulation System and the Immune System: Interactions and Connections. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Aug 8;24(16):12563. PMID: 37628744; PMCID: PMC10454528. [CrossRef]

- Weiss SL, Peters MJ, Alhazzani W, Agus MSD, Flori HR, Inwald DP, Nadel S, Schlapbach LJ, Tasker RC, Argent AC, Brierley J, Carcillo J, Carrol ED, Carroll CL, Cheifetz IM, Choong K, Cies JJ, Cruz AT, De Luca D, Deep A, Faust SN, De Oliveira CF, Hall MW, Ishimine P, Javouhey E, Joosten KFM, Joshi P, Karam O, Kneyber MCJ, Lemson J, MacLaren G, Mehta NM, Møller MH, Newth CJL, Nguyen TC, Nishisaki A, Nunnally ME, Parker MM, Paul RM, Randolph AG, Ranjit S, Romer LH, Scott HF, Tume LN, Verger JT, Williams EA, Wolf J, Wong HR, Zimmerman JJ, Kissoon N, Tissieres P. Surviving Sepsis Campaign International Guidelines for the Management of Septic Shock and Sepsis-Associated Organ Dysfunction in Children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2020 Feb;21(2):e52-e106. PMID: 32032273. [CrossRef]

- Haque KN. Defining common infections in children and neonates. J Hosp Infect. 2007 Jun;65 Suppl 2:110-4. PMID: 17540253. [CrossRef]

- McGovern M, Giannoni E, Kuester H, Turner MA, van den Hoogen A, Bliss JM, Koenig JM, Keij FM, Mazela J, Finnegan R, Degtyareva M, Simons SHP, de Boode WP, Strunk T, Reiss IKM, Wynn JL, Molloy EJ; Infection, Inflammation, Immunology and Immunisation (I4) section of the ESPR. Challenges in developing a consensus definition of neonatal sepsis. Pediatr Res. 2020 Jul;88(1):14-26. Epub 2020 Mar 3. PMID: 32126571. [CrossRef]

- Santhanam I, Sangareddi S, Venkataraman S, Kissoon N, Thiruvengadamudayan V, Kasthuri RK. A prospective randomized controlled study of two fluid regimens in the initial management of septic shock in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008 Oct;24(10):647-55. PMID: 19242131. [CrossRef]

- Iroh Tam PY, Musicha P, Kawaza K, Cornick J, Denis B, Freyne B, Everett D, Dube Q, French N, Feasey N, Heyderman R. Emerging Resistance to Empiric Antimicrobial Regimens for Pediatric Bloodstream Infections in Malawi (1998-2017). Clin Infect Dis. 2019 Jun 18;69(1):61-68. PMID: 30277505; PMCID: PMC6579959. [CrossRef]

- Perner A, Haase N, Guttormsen AB, Tenhunen J, Klemenzson G, Åneman A, Madsen KR, Møller MH, Elkjær JM, Poulsen LM, Bendtsen A, Winding R, Steensen M, Berezowicz P, Søe-Jensen P, Bestle M, Strand K, Wiis J, White JO, Thornberg KJ, Quist L, Nielsen J, Andersen LH, Holst LB, Thormar K, Kjældgaard AL, Fabritius ML, Mondrup F, Pott FC, Møller TP, Winkel P, Wetterslev J; 6S Trial Group; Scandinavian Critical Care Trials Group. Hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.42 versus Ringer's acetate in severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2012 Jul 12;367(2):124-34. Epub 2012 Jun 27. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2012 Aug 2;367(5):481. PMID: 22738085. [CrossRef]

- Scott HF, Brou L, Deakyne SJ, Fairclough DL, Kempe A, Bajaj L. Lactate Clearance and Normalization and Prolonged Organ Dysfunction in Pediatric Sepsis. J Pediatr. 2016 Mar;170:149-55.e1-4. Epub 2015 Dec 19. PMID: 26711848. [CrossRef]

- Ventura AM, Shieh HH, Bousso A, Góes PF, de Cássia F O Fernandes I, de Souza DC, Paulo RL, Chagas F, Gilio AE. Double-Blind Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial of Dopamine Versus Epinephrine as First-Line Vasoactive Drugs in Pediatric Septic Shock. Crit Care Med. 2015 Nov;43(11):2292-302. PMID: 26323041. [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy KN, Singhi S, Jayashree M, Bansal A, Nallasamy K. Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Dopamine and Epinephrine in Pediatric Fluid-Refractory Hypotensive Septic Shock. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016 Nov;17(11):e502-e512. PMID: 27673385. [CrossRef]

- El-Nawawy A, Khater D, Omar H, Wali Y. Evaluation of Early Corticosteroid Therapy in Management of Pediatric Septic Shock in Pediatric Intensive Care Patients: A Randomized Clinical Study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017 Feb;36(2):155-159. PMID: 27798546. [CrossRef]

| Criterion | Value |

| Body temperature (rectal, oral) | >38.5°C or <36°C |

| Heart rate | Tachycardia ≥ 90/min, or bradycardia in children under 1 year of age below the 10th percentile |

| Respiratory rate | ≥ 20/min or hyperventilation with blood carbon dioxide ≤ 32 mmHg |

| White blood cell count | Leukocytosis or leukopenia or neutrophil left shift |

| Maternal risk factors |

|

| Fetal risk factors |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).