Submitted:

06 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Basic Information About the CaAHL Gene Family

2.2. Chromosome Distribution of the CaAHL Gene Family

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis of the CaAHL Gene Family

2.4. Analysis of CaAHLs Conserved Motifs

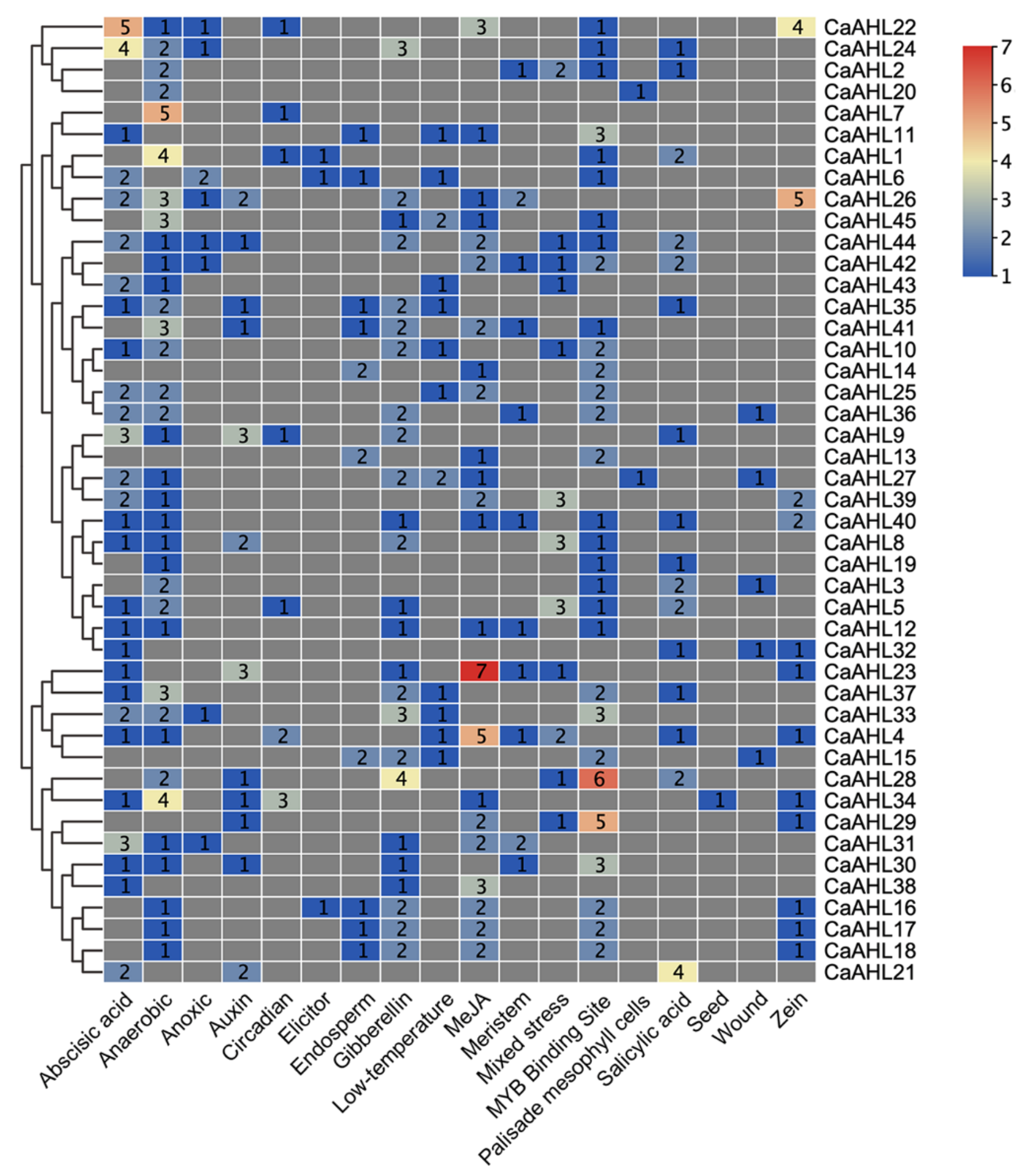

2.5. Cis-Regulatory Element Analysis of the CaAHLs Promoter

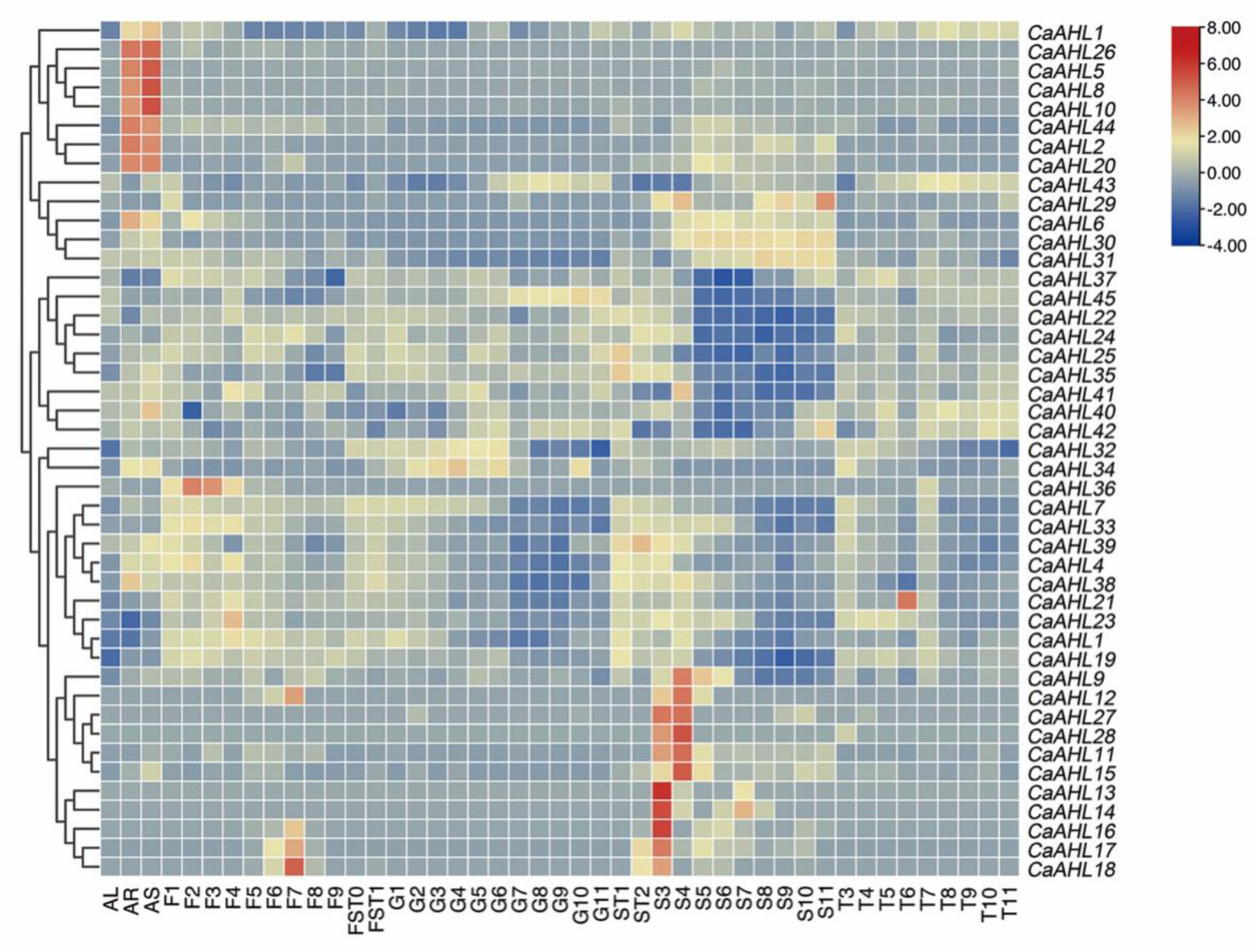

2.6. Tissue-Specific Expression Profiles of the CaAHLs in Peppers

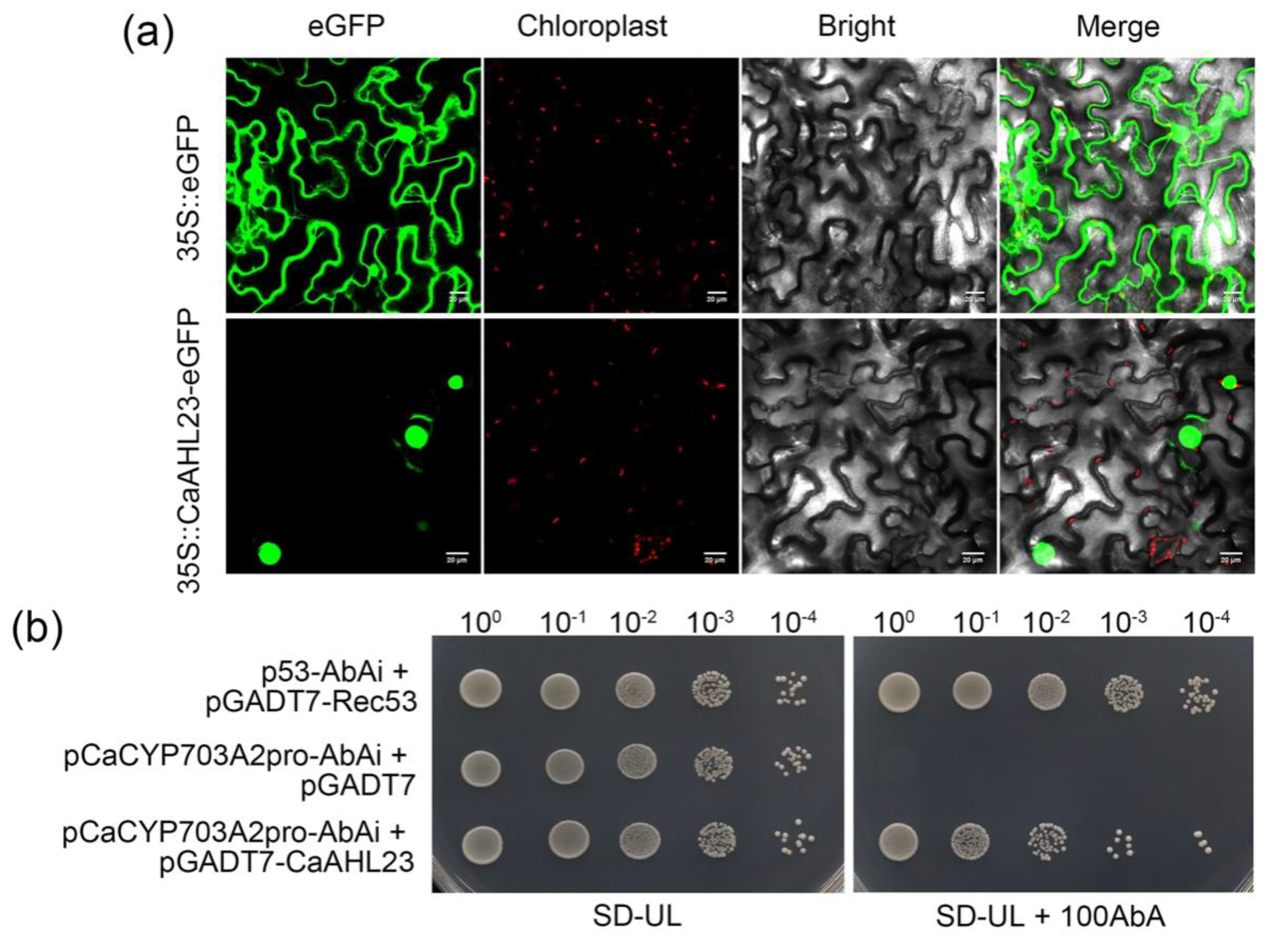

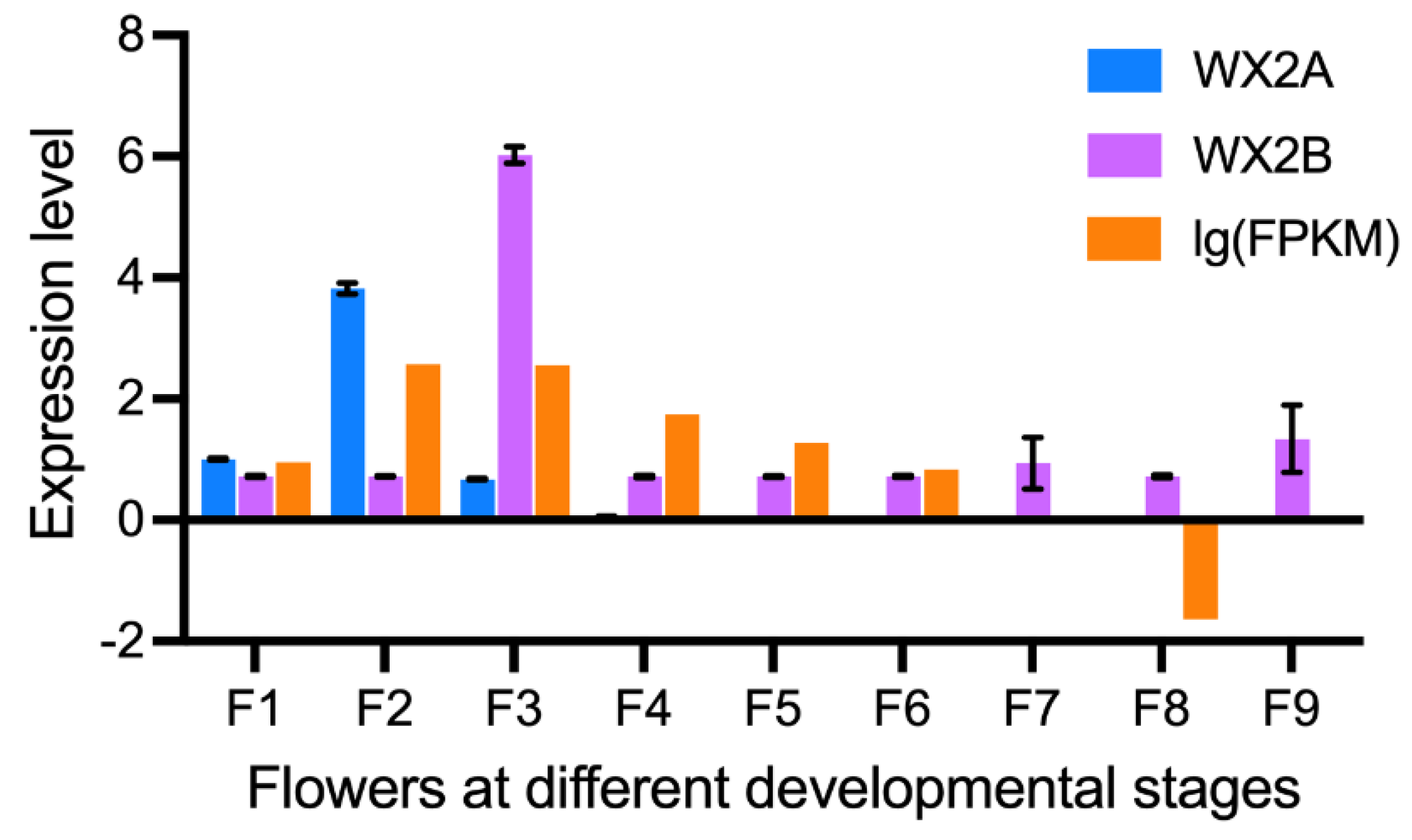

2.7. CaAHL23 as a Potential Regulator in Pepper Male Sterility

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Retrieval and Identification of AHL Genes in Pepper

4.2. Sequence Analysis and Structural Characteristics

4.3. Chromosome Localization, Tandem Duplication, and Synteny Analysis

4.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

4.5. RNA-Seq Analysis of CaAHL Genes

4.6. RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR Analysis

4.7. Subcellular Localization

4.8. Y1H Assays

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, S.; Park, M.; Yeom, S.-I.; Kim, Y.-M.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, H.-A.; Seo, E.; Choi, J.; Cheong, K.; Kim, K.-T.; et al. Genome Sequence of the Hot Pepper Provides Insights into the Evolution of Pungency in Capsicum Species. Nat Genet 2014, 46, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, U.; Li, X.; Fan, Y.; Chang, W.; Niu, Y.; Li, J.; Qu, C.; Lu, K. Multi-Omics Revolution to Promote Plant Breeding Efficiency. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, K.; Momo, J.; Rawoof, A.; Vijay, A.; Anusree, V.K.; Kumar, A.; Ramchiary, N. Integrated Use of Molecular and Omics Approaches for Breeding High Yield and Stress Resistance Chili Peppers BT - Smart Plant Breeding for Vegetable Crops in Post-Genomics Era. In; Singh, S., Sharma, D., Sharma, S.K., Singh, R., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2023; pp. 279–335. ISBN 978-981-19-5367-5. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Zheng, S.; Witzel, K.; Van De Slijke, E.; Baekelandt, A.; Mylle, E.; Van Damme, D.; Cheng, J.; De Jaeger, G.; Inzé, D.; et al. Chromatin Attachment to the Nuclear Matrix Represses Hypocotyl Elongation in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, I.H.; Shah, P.K.; Smith, A.M.; Avery, N.; Neff, M.M. The AT-Hook-Containing Proteins SOB3/AHL29 and ESC/AHL27 Are Negative Modulators of Hypocotyl Growth in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal 2008, 54, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Chen, F.; Yu, X.; Lin, C.; Fu, Y.-F. Over-Expression of an AT-Hook Gene, AHL22, Delays Flowering and Inhibits the Elongation of the Hypocotyl in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Plant Mol Biol 2009, 71, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzair, M.; Xu, D.; Schreiber, L.; Shi, J.; Liang, W.; Jung, K.-H.; Chen, M.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.; et al. PERSISTENT TAPETAL CELL2 Is Required for Normal Tapetal Programmed Cell Death and Pollen Wall Patterning1 [OPEN]. Plant Physiol 2020, 182, 962–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayengwa, R.; Sharma Koirala, P.; Pierce, C.F.; Werner, B.E.; Neff, M.M. Overexpression of AtAHL20 Causes Delayed Flowering in Arabidopsis via Repression of FT Expression. BMC Plant Biol 2020, 20, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machaj, G.; Grzebelus, D. Characteristics of the AT-Hook Motif Containing Nuclear Localized (AHL) Genes in Carrot Provides Insight into Their Role in Plant Growth and Storage Root Development. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Yang, H.; Sun, H.; Lu, P.; Yan, P.; Zhao, W.; Zeng, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L.; Hou, W. Characterization of AHL Transcription Factors and Functional Analysis of IbAHL10 in Storage Root Development in Sweetpotato. Sci Hortic 2024, 338, 113718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favero, D.S.; Kawamura, A.; Shibata, M.; Takebayashi, A.; Jung, J.-H.; Suzuki, T.; Jaeger, K.E.; Ishida, T.; Iwase, A.; Wigge, P.A.; et al. AT-Hook Transcription Factors Restrict Petiole Growth by Antagonizing PIFs. Current Biology 2020, 30, 1454–1466e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.-N.; Sun, H.-J.; Zuo, Z.-F.; Lee, D.H.; Song, P.-S.; Kang, H.-G.; Lee, H.-Y. Overexpression of ATHG1/AHL23 and ATPG3/AHL20, Arabidopsis AT-Hook Motif Nuclear-Localized Genes, Confers Salt Tolerance in Transgenic Zoysia Japonica. Plant Biotechnol Rep 2020, 14, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howden, A.J.M.; Stam, R.; Martinez Heredia, V.; Motion, G.B.; ten Have, S.; Hodge, K.; Marques Monteiro Amaro, T.M.; Huitema, E. Quantitative Analysis of the Tomato Nuclear Proteome during Phytophthora Capsici Infection Unveils Regulators of Immunity. New Phytologist 2017, 215, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayapuram, N.; Jarad, M.; Alhoraibi, H.M.; Bigeard, J.; Abulfaraj, A.A.; Völz, R.; Mariappan, K.G.; Almeida-Trapp, M.; Schlöffel, M.; Lastrucci, E.; et al. Chromatin Phosphoproteomics Unravels a Function for AT-Hook Motif Nuclear Localized Protein AHL13 in PAMP-Triggered Immunity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2004670118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Kong, D.; Li, T.; Yu, S.; Mei, H.; Xu, X.; Liu, H.; Chen, L.; et al. A Novel Gene OsAHL1 Improves Both Drought Avoidance and Drought Tolerance in Rice. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 30264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lü, Y.; Chen, W.; Yao, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Pan, J.; Fang, S.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y. Genome-Wide Identification and Analyses of the AHL Gene Family in Cotton (Gossypium). BMC Genomics 2020, 21, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, B.; Zhou, W.; Xie, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the AT-Hook Motif Nuclear Localized Gene Family in Soybean. BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, S.; Mishra, A. Genome-Wide Identification and Analyses of the AHL Gene Family in Rice (Oryza Sativa). 3 Biotech 2023, 13, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, E.H.; Kumar, R.; Luo, F.; Saski, C.; Sekhon, R.S. Genome-Wide Identification, Expression Profiling, and Network Analysis of AT-Hook Gene Family in Maize. Genomics 2020, 112, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.; Kim, Y.-S.; Jung, J.-H.; Seo, P.J.; Park, C.-M. The AT-Hook Motif-Containing Protein AHL22 Regulates Flowering Initiation by Modifying FLOWERING LOCUS T Chromatin in Arabidopsis*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012, 287, 15307–15316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Gan, E.-S.; Ito, T. The AT-Hook/PPC Domain Protein TEK Negatively Regulates Floral Repressors Including MAF4 and MAF5. Plant Signal Behav 2013, 8, e25006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Xu, X.-F.; Zhu, J.; Gu, J.-N.; Blackmore, S.; Yang, Z.-N. The Tapetal AHL Family Protein TEK Determines Nexine Formation in the Pollen Wall. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karami, O.; Rahimi, A.; Mak, P.; Horstman, A.; Boutilier, K.; Compier, M.; van der Zaal, B.; Offringa, R. An Arabidopsis AT-Hook Motif Nuclear Protein Mediates Somatic Embryogenesis and Coinciding Genome Duplication. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlgren, A.; Gyllenstrand, N.; Källman, T.; Sundström, J.F.; Moore, D.; Lascoux, M.; Lagercrantz, U. Evolution of the PEBP Gene Family in Plants: Functional Diversification in Seed Plant Evolution. Plant Physiol 2011, 156, 1967–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z.; Tian, D.; Li, Y.; Aminu, I.M.; Tabusam, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, S. Characterization, Evolution, Expression and Functional Divergence of the DMP Gene Family in Plants. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, J.; Ellis, N. Conservation and Diversification of Gene Function in Plant Development. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2002, 5, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.-Y.; Lin, P.-F.; Xu, R.-J.; Kang, H.-Q.; Gao, L.-Z. Comparative Genomic Analysis of Asian Cultivated Rice and Its Wild Progenitor (Oryza Rufipogon) Has Revealed Evolutionary Innovation of the Pentatricopeptide Repeat Gene Family through Gene Duplication. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qanmber, G.; Liu, J.; Yu, D.; Liu, Z.; Lu, L.; Mo, H.; Ma, S.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Z. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of the PERK Gene Family in Gossypium Hirsutum Reveals Gene Duplication and Functional Divergence. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Li, Q.; Yin, H.; Qi, K.; Li, L.; Wang, R.; Zhang, S.; Paterson, A.H. Gene Duplication and Evolution in Recurring Polyploidization–Diploidization Cycles in Plants. Genome Biol 2019, 20, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; He, W.; Guo, X.; Pan, J. Genome-Wide Identification, Classification and Expression Analysis of the MYB Transcription Factor Family in Petunia. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Lu, X.; Zhang, P.; Wang, G.; Wei, L.; Wang, T. Systematic Analysis of Differentially Expressed Maize ZmbZIP Genes between Drought and Rewatering Transcriptome Reveals BZIP Family Members Involved in Abiotic Stress Responses. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Guo, X.; Wang, H.; Zhen, W.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Botella, J.R.; et al. Overexpression of AHL9 Accelerates Leaf Senescence in Arabidopsis Thaliana. BMC Plant Biol 2022, 22, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Favero, D.S.; Peng, H.; Neff, M.M. Arabidopsis Thaliana AHL Family Modulates Hypocotyl Growth Redundantly by Interacting with Each Other via the PPC/DUF296 Domain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110, E4688–E4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Wu, D.; Shi, J.; He, Y.; Pinot, F.; Grausem, B.; Yin, C.; Zhu, L.; Chen, M.; Luo, Z.; et al. Rice CYP703A3, a Cytochrome P450 Hydroxylase, Is Essential for Development of Anther Cuticle and Pollen Exine. J Integr Plant Biol 2014, 56, 979–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Wu, Y.; Lv, R.; Chi, H.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, L.; Guo, X.; et al. Cytochrome P450 Mono-Oxygenase CYP703A2 Plays a Central Role in Sporopollenin Formation and Ms5ms6 Fertility in Cotton. J Integr Plant Biol 2022, 64, 2009–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Zhao, J.; Sun, H.; Xiong, C.; Sun, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Jarret, R.; Wang, J.; Tang, B.; et al. Genomes of Cultivated and Wild Capsicum Species Provide Insights into Pepper Domestication and Population Differentiation. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistry, J.; Chuguransky, S.; Williams, L.; Qureshi, M.; Salazar, G.A.; Sonnhammer, E.L.L.; Tosatto, S.C.E.; Paladin, L.; Raj, S.; Richardson, L.J.; et al. Pfam: The Protein Families Database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, D412–D419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “One for All, All for One” Bioinformatics Platform for Biological Big-Data Mining. Mol Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, P.; Park, K.-J.; Obayashi, T.; Fujita, N.; Harada, H.; Adams-Collier, C.J.; Nakai, K. WoLF PSORT: Protein Localization Predictor. Nucleic Acids Res 2007, 35, W585–W587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Elkan, C. Fitting a Mixture Model by Expectation Maximization to Discover Motifs in Bipolymers. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol 1994, 2, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, J.-T.; Kong, Y.-Z.; Wang, Q.; Sun, Y.-H.; Gong, D.-P.; Lv, J.; Liu, G.-S. MapGene2Chrom, a Tool to Draw Gene Physical Map Based on Perl and SVG Languages. Yi Chuan 2015, 37, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol Biol Evol 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (ITOL) v5: An Online Tool for Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Yu, H.; Deng, Y.; Zheng, J.; Liu, M.; Ou, L.; Yang, B.; Dai, X.; Ma, Y.; Feng, S.; et al. PepperHub, an Informatics Hub for the Chili Pepper Research Community. Mol Plant 2017, 10, 1129–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | Gene ID | Chromosome location | Protein length | Molecular weight (kDa) | Theoretical pI | Instability index | Grand average of hydropathicity | Subcellular localization1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaAHL1 | Caz01g03310.1 | Chr01:5691094-5697294 | 347 | 35.27 | 9.62 | 38.59 | -0.33 | nucl |

| CaAHL2 | Caz01g04670.1 | Chr01:9114966-9116603 | 295 | 31.17 | 5.79 | 52.67 | -0.54 | nucl |

| CaAHL3 | Caz01g04810.1 | Chr01:9383031-9386809 | 322 | 33.18 | 8.74 | 50.79 | -0.17 | chlo |

| CaAHL4 | Caz01g08370.1 | Chr01:20063956-20073612 | 418 | 43.66 | 8.82 | 60.17 | -0.76 | nucl |

| CaAHL5 | Caz01g08400.1 | Chr01:20111560-20112474 | 304 | 31.69 | 5.75 | 51.83 | -0.27 | nucl |

| CaAHL6 | Caz01g13980.1 | Chr01:55893363-55894391 | 314 | 33.10 | 6.83 | 53.54 | -0.60 | nucl |

| CaAHL7 | Caz01g14080.1 | Chr01:56075436-56079692 | 324 | 33.72 | 9.57 | 47.83 | -0.25 | chlo |

| CaAHL8 | Caz01g31040.1 | Chr01:251924071-251924907 | 278 | 29.43 | 6.54 | 50.25 | -0.47 | chlo |

| CaAHL9 | Caz01g35190.1 | Chr01:276409484-276418256 | 123 | 13.45 | 5.87 | 47.09 | -0.20 | cyto |

| CaAHL10 | Caz01g40510.1 | Chr01:326409380-326414186 | 265 | 28.25 | 5.96 | 44.58 | -0.44 | nucl |

| CaAHL11 | Caz01g40520.1 | Chr01:326434617-326442536 | 331 | 35.20 | 9.51 | 49.49 | -0.46 | chlo |

| CaAHL12 | Caz01g40530.1 | Chr01:326492721-326618469 | 316 | 33.80 | 10.04 | 51.86 | -0.37 | nucl |

| CaAHL13 | Caz01g40540.1 | Chr01:326621531-326626277 | 207 | 22.30 | 6.96 | 44.75 | -0.13 | nucl |

| CaAHL14 | Caz01g40550.1 | Chr01:326687022-326691770 | 207 | 22.34 | 7.84 | 44.38 | -0.14 | chlo |

| CaAHL15 | Caz01g40640.1 | Chr01:327024609-327031508 | 329 | 34.72 | 9.65 | 48.09 | -0.47 | chlo |

| CaAHL16 | Caz01g40680.1 | Chr01:327253871-327258557 | 288 | 30.70 | 8.76 | 47.03 | -0.45 | chlo |

| CaAHL17 | Caz01g40710.1 | Chr01:327378313-327383011 | 273 | 29.34 | 7.79 | 47.92 | -0.53 | chlo |

| CaAHL18 | Caz01g40720.1 | Chr01:327501110-327505809 | 273 | 29.30 | 7.79 | 51.24 | -0.53 | chlo |

| CaAHL19 | Caz01g41290.1 | Chr01:329720440-329727085 | 332 | 34.13 | 9.54 | 44.92 | -0.10 | chlo |

| CaAHL20 | Caz01g41410.1 | Chr01:329900501-329901727 | 316 | 33.79 | 6.05 | 59.8 | -0.63 | chlo |

| CaAHL21 | Caz01g41740.1 | Chr01:331181444-331186914 | 352 | 35.75 | 9.44 | 49.49 | -0.27 | nucl |

| CaAHL22 | Caz02g02600.1 | Chr02:44359225-44368231 | 345 | 34.69 | 8.97 | 55.44 | -0.11 | E.R. |

| CaAHL23 | Caz02g20690.1 | Chr02:156842236-156848762 | 331 | 33.33 | 9.99 | 50.43 | -0.23 | nucl |

| CaAHL24 | Caz03g00210.1 | Chr03:551605-558146 | 111 | 12.02 | 6.39 | 30.43 | 0.01 | chlo |

| CaAHL25 | Caz03g21400.1 | Chr03:72579177-72587401 | 346 | 36.17 | 6.33 | 45.59 | -0.38 | nucl |

| CaAHL26 | Caz03g34730.1 | Chr03:267518820-267519650 | 276 | 28.85 | 5.45 | 57.84 | -0.47 | cyto |

| CaAHL27 | Caz03g36660.1 | Chr03:273808903-273810928 | 122 | 12.87 | 5.19 | 34.02 | 0.18 | cyto |

| CaAHL28 | Caz03g36670.1 | Chr03:273824211-273825851 | 113 | 12.01 | 6.01 | 47.05 | -0.25 | nucl |

| CaAHL29 | Caz03g36680.1 | Chr03:273829352-273850851 | 273 | 28.76 | 9.64 | 49.08 | -0.30 | vacu |

| CaAHL30 | Caz04g00390.1 | Chr04:713251-718475 | 267 | 26.36 | 6.42 | 48.45 | -0.13 | nucl |

| CaAHL31 | Caz04g08200.1 | Chr04:20375417-20376564 | 352 | 37.79 | 7.05 | 63.62 | -0.66 | nucl |

| CaAHL32 | Caz05g17580.1 | Chr05:235719249-235723745 | 294 | 31.56 | 5.35 | 52.68 | -0.61 | nucl |

| CaAHL33 | Caz06g17080.1 | Chr06:50064634-50076684 | 349 | 36.50 | 9.34 | 53.47 | -0.51 | nucl |

| CaAHL34 | Caz06g17990.1 | Chr06:57415662-57416120 | 152 | 15.59 | 4.44 | 51.44 | -0.03 | nucl |

| CaAHL35 | Caz06g24080.1 | Chr06:182665460-182672828 | 341 | 35.70 | 7.02 | 40.07 | -0.30 | plas |

| CaAHL36 | Caz07g19270.1 | Chr07:251735483-251736292 | 269 | 28.24 | 9.24 | 33.67 | -0.13 | cyto |

| CaAHL37 | Caz08g07460.1 | Chr08:137932240-137938844 | 341 | 34.99 | 10.26 | 58.12 | -0.22 | nucl |

| CaAHL38 | Caz09g21720.1 | Chr09:274809109-274813725 | 438 | 45.01 | 9.38 | 50.94 | -0.34 | nucl |

| CaAHL39 | Caz12g05920.1 | Chr12:13682382-13697371 | 578 | 60.51 | 7.72 | 52.36 | -0.30 | chlo |

| CaAHL40 | Caz12g05950.1 | Chr12:13811174-13813071 | 115 | 11.71 | 11.25 | 59.27 | -0.01 | chlo |

| CaAHL41 | Caz12g06070.1 | Chr12:14037114-14041618 | 177 | 18.10 | 4.89 | 59.53 | -0.20 | chlo |

| CaAHL42 | Caz12g06080.1 | Chr12:14056732-14062760 | 438 | 47.47 | 9.27 | 50.27 | -0.21 | chlo |

| CaAHL43 | Caz12g08880.1 | Chr12:32039622-32040395 | 257 | 28.05 | 7.83 | 49.44 | -0.42 | nucl |

| CaAHL44 | Caz12g18220.1 | Chr12:219722263-219725994 | 293 | 29.60 | 6.16 | 46.17 | -0.33 | nucl |

| CaAHL45 | Caz12g18510.1 | Chr12:221530027-221540499 | 358 | 37.13 | 9.57 | 50.03 | -0.37 | cyto |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).