Submitted:

05 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

2. Methodology

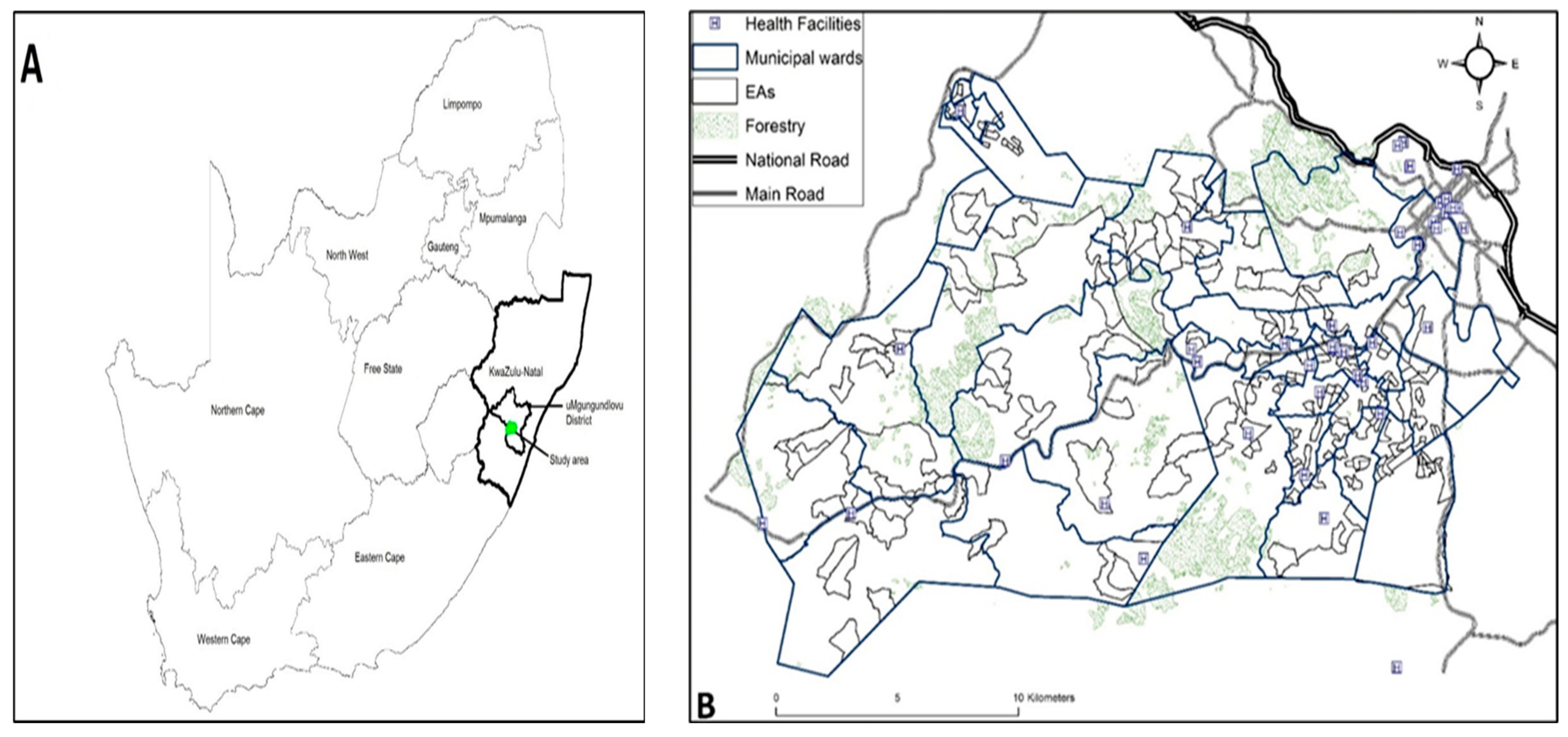

2.1. Study Area Location

2.2. Sources of Data and Study Population

2.3. Study Variables

2.4. Spatial Autocorrelation

2.4.1. Global Moran’s Index Statistic

2.4.2. Geary’s C Statistic

2.5. Bayesian Logistic Regression Models

2.6. Prior Distributions

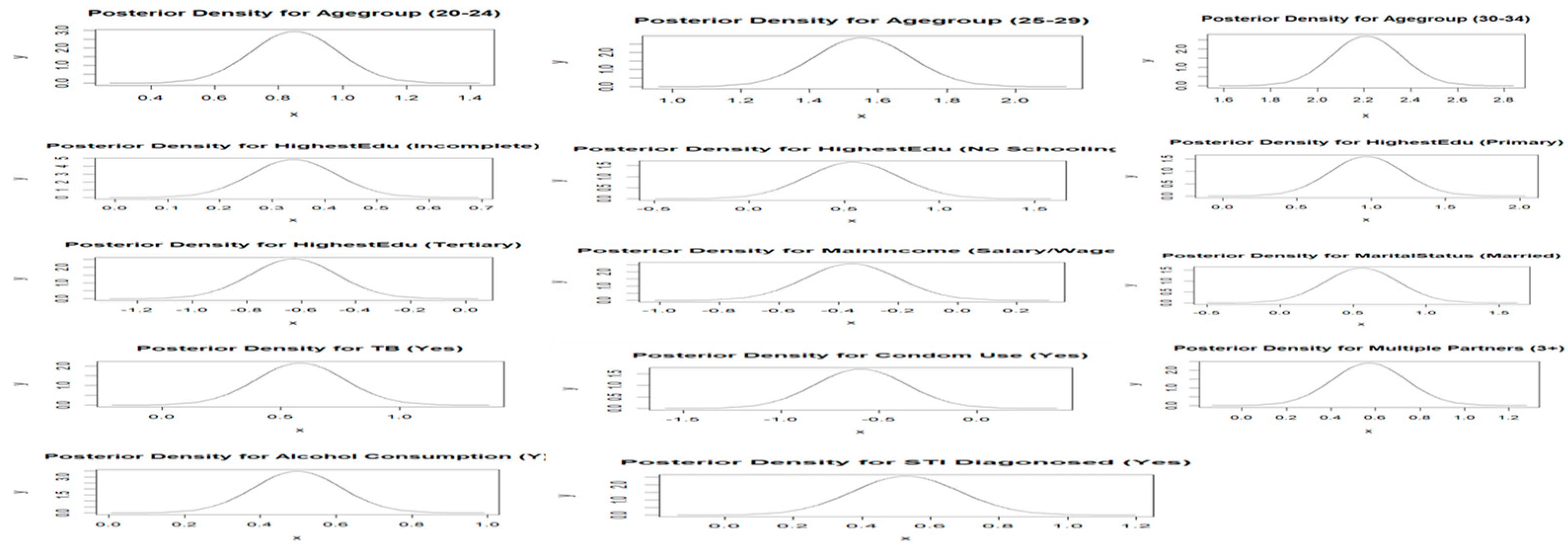

2.7. Posterior Distributions and Point Estimates

2.8. Bayesian Spatial Logistic Regression Models Applied

2.8.1. Unstructured Bayesian Spatial Logistic Regression Model:

2.8.2. Structured Bayesian Spatial Logistic Regression Model:

2.9. Model Selection Criteria

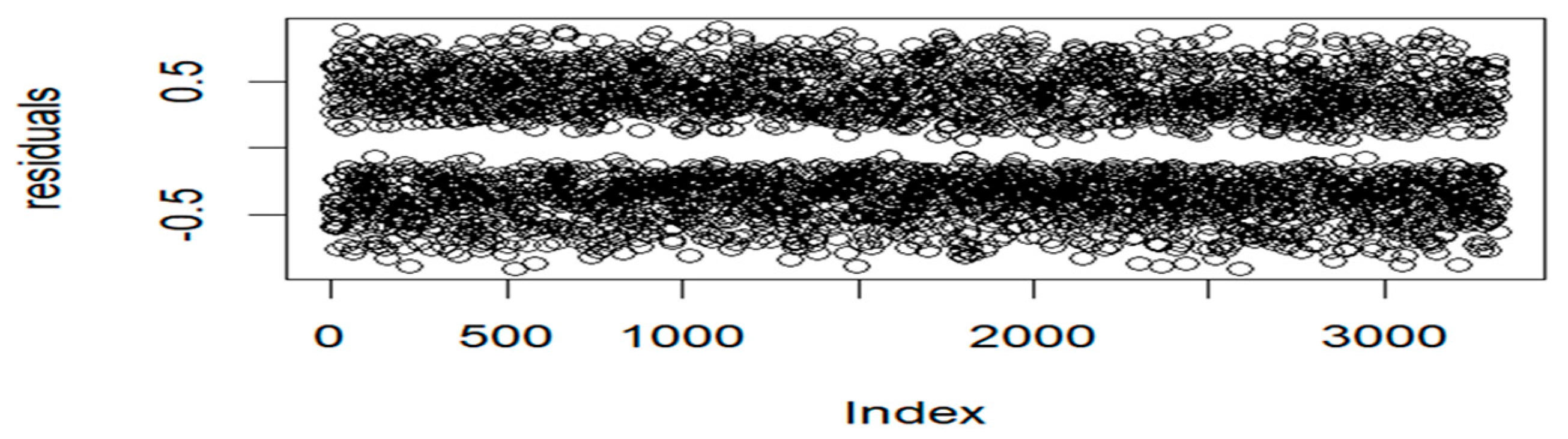

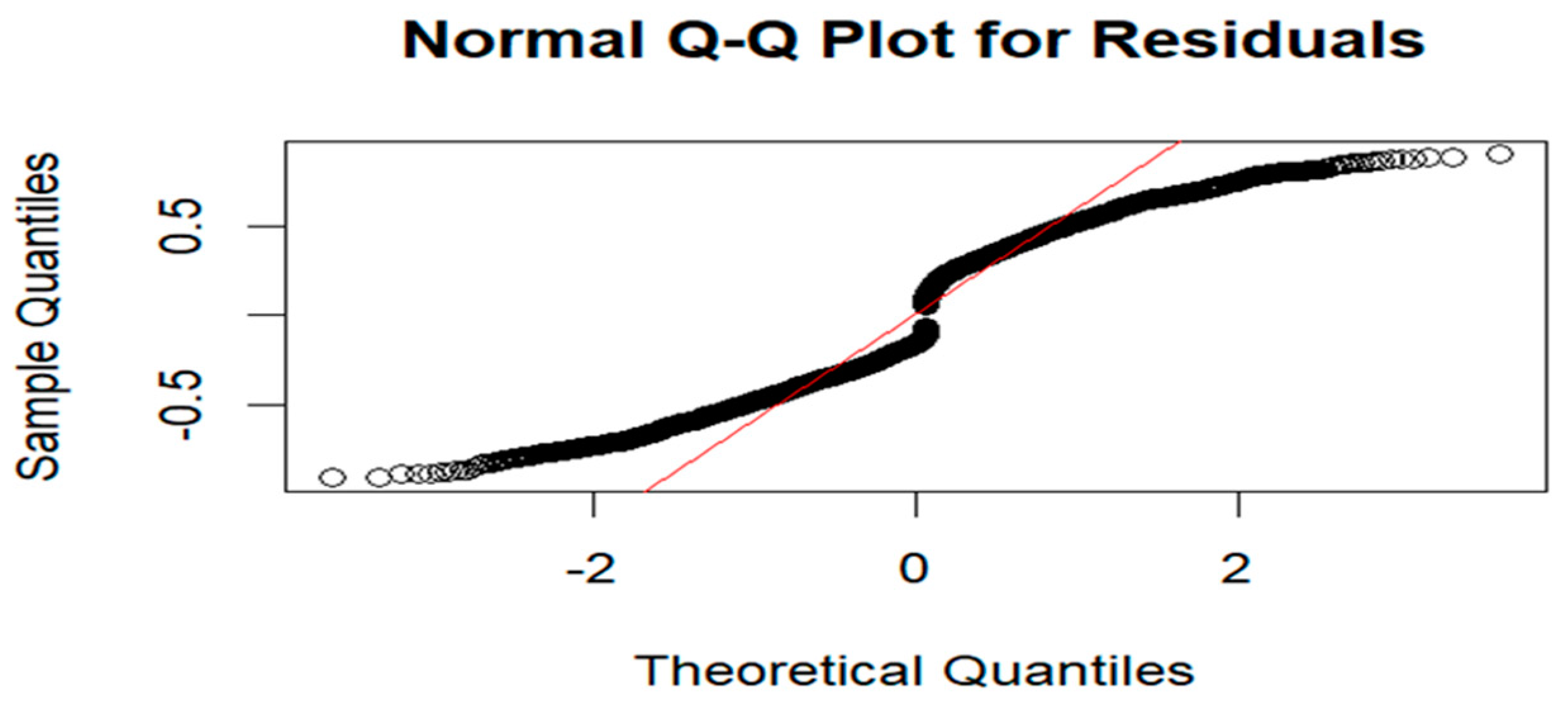

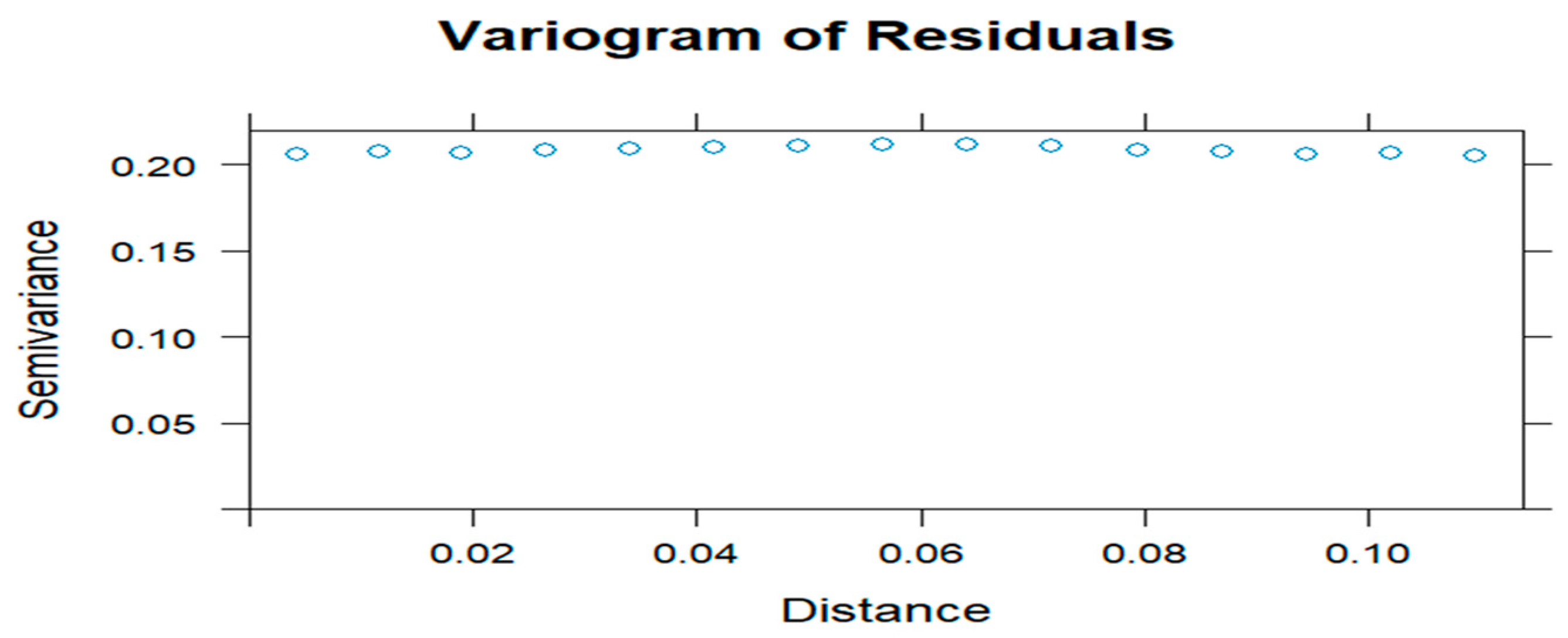

2.10. Model Diagnostics

2.11. Software and Implementation

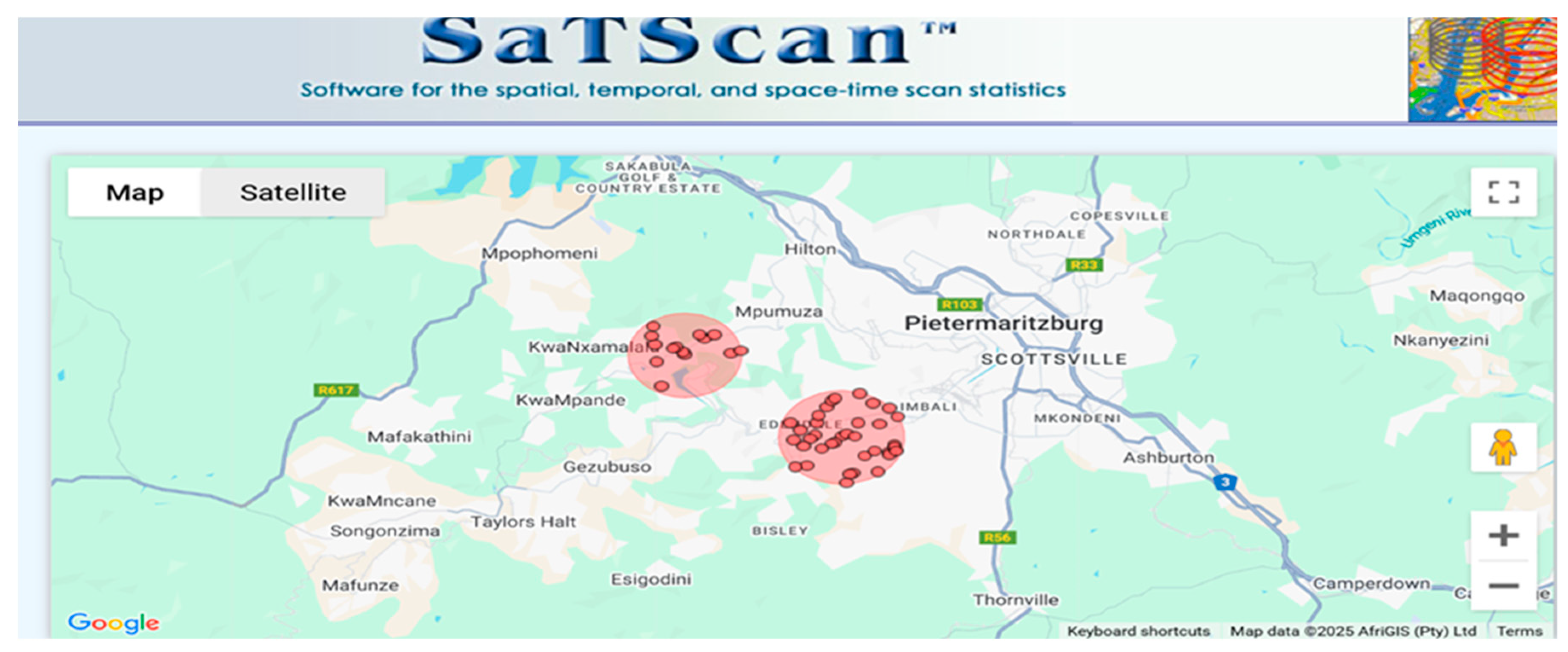

3. Empirical Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Authors’ information

Funding

Availability of data materials

Declarations Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate in the Study

Consent for Publication

Competing Interests

Abbreviations

- HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- KZN: KwaZulu Natal

- HIPSS: HIV Incidence Provincial Surveillance System

- STIs: Sexually Transmitted Infections

- INLA: Integrated Nested Laplace Approximation

- GIS: Geographical Information System

- MCMC: Markov Chain Monte Carlo

- CI: Credible Interval

- OR: Odds Ratios

References

- Kharsany ABM, Karim QA. HIV infection and AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa: current status, challenges, and opportunities. The Open AIDS Journal. 2016, 10, 34–48. [CrossRef]

- Kharsany ABM, Cawood C, Khanyile D, et al. Community-based HIV prevalence in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: results of a cross-sectional household survey. The Lancet HIV 2018, 5, e427–e437. [CrossRef]

- UNAIDS. In danger: UNAIDS global AIDS update 2022. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2022.

- Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Shai N. Transactional sex and HIV incidence in a cohort of young women in the Stepping Stones trial. J AIDS Clin Res. 2015, 68, 449–456.

- Zuma K, Shisana O, Rehle TM, Simbayi LC, Jooste S, Zungu N, et al. New HIV infections in South Africa: Evidence from the 2012 population-based household survey. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2016, 32, 121–134.

- Leclerc-Madlala S. Age-disparate and intergenerational sex in southern Africa: the dynamics of hypervulnerability. AIDS 2008, 22, S17–25.

- Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, Gray GE, McIntryre JA, Harlow SD. Transactional sex among women in Soweto, South Africa: prevalence, risk factors and association with HIV infection. Soc Sci Med. 2016, 62, 181–193. [CrossRef]

- Tomita A, Vandormael A, Bärnighausen T, de Oliveira T, Tanser F. Social determinants of HIV infection clustering in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2017, 21, 2417–2426.

- Tanser F, Bärnighausen T, Cooke GS, Newell ML. Localized spatial clustering of HIV infections in a widely disseminated rural South African epidemic. Int J Epidemiol. 2009, 38, 1008–1016. [CrossRef]

- Lawson AB. Bayesian disease mapping: Hierarchical modeling in spatial epidemiology. 2nd ed. CRC Press; 2013.

- Ngesa O, Mwambi H, Achia T. Bayesian spatial semi-parametric modeling of HIV variation in Kenya. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e103299. [CrossRef]

- Gemechu LL, Debusho LK. Bayesian spatial modelling of tuberculosis-HIV co-infection in Ethiopia. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0283334. [CrossRef]

- Rue H, Held L. Gaussian Markov Random Fields: Theory and Applications. CRC Press; 2005.

- Rue H, Martino S, Chopin N. Approximate Bayesian inference for latent Gaussian models using integrated nested Laplace approximations (INLA). J R Stat Soc B. 2009, 71, 319–392.

- Tomita A, Vandormael A, Cuadros D, Di Minin E, Heikinheimo V, Tanser F, Slotow R. Spatial clustering of HIV prevalence in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: applying Bayesian spatial modeling to a hyperendemic epidemic. Int J Health Geogr. 2020, 19, 1–12.

- Gelman A, Carlin JB, Stern HS, Dunson DB, Vehtari A, Rubin DB. Bayesian Data Analysis. 3rd ed. CRC Press; 2013.

- Tanser F, Bärnighausen T, Dobra A, et al. High HIV incidence in a hyperendemic area of South Africa: A 10-year cohort study. AIDS 2021, 35, 35–45.

- Republic of South Africa. National Youth Policy 2020-2023. Pretoria: Department of Women, Youth and Persons with Disabilities; 2020.

- Gómez-Rubio V. Bayesian Inference with INLA. Boca Raton, Florida: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2020.

- Moran PAP. Notes on continuous stochastic phenomena. Biometrika 1950, 37, 17–23.

- Waller LA, Gotway CA. Applied Spatial Statistics for Public Health Data. John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA; 2004.

- Hu W, Mengersen K, Tong S. Risk factor analysis and spatiotemporal CART model of cryptosporidiosis in Queensland, Australia. BMC Infect Dis. 2010, 10, 311. [CrossRef]

- Haining R, Li G. Modelling Spatial and Spatial-Temporal Data: A Bayesian Approach. 1st ed. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL, USA; 2020.

- Cliff AD, Ord JK. Spatial processes: Models & applications. Pion. 1981.

- Anselin L. Local Indicators of Spatial Association—LISA. Geographical Analysis 1995, 27, 93–115. [CrossRef]

- Geary RC. The contiguity ratio and statistical mapping. Incorporated Stat. 1954, 5, 115–145. [CrossRef]

- Kulldorff M. Spatial scan statistics: Models, calculations, and applications. In: Scan Statistics and Applications. Springer; 1999. p. 303–322.

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression. 3rd ed. Hoboken: Wiley; 2013.

- McElreath R. Statistical rethinking: A Bayesian course with examples in R and Stan. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2020.

- Lawson AB. Bayesian disease mapping: hierarchical models and spatial dependence. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2018.

- Banerjee S, Carlin BP, Gelfand AE. Hierarchical Modelling and Analysis for Spatial Data (2nd ed.). CRC Press; 2014.

- Cressie N, Wikle CK. Statistics for Spatio-Temporal Data. John Wiley & Sons; 2011.

- Gelfand AE, Banerjee S. Bayesian Modeling and Analysis of Spatial Data. CRC Press; 2017.

- Simpson D, Rue H, Riebler A, et al. Penalising model component complexity: a principled, practical approach to constructing priors. Stat Sci. 2017, 32, 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Riebler A, Sørbye SH, Simpson D, Rue H. An intuitive Bayesian spatial model for disease mapping that accounts for scaling. Stat Methods Med Res. 2016, 25, 1145–1165. [CrossRef]

- Wakefield J. Disease mapping and spatial regression with count data. Biostatistics. 2007, 8, 158–183. [CrossRef]

- Besag J, York J, Mollié A. Bayesian image restoration, with two applications in spatial statistics. Annals of the Institute of Statistical Mathematics. 1991, 43, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Spiegelhalter DJ, Best NG, Carlin BP, van der Linde A. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. J R Stat Soc B. 2002, 64, 583–639. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe S. Asymptotic equivalence of the bayes cross validation and widely applicable information criterion in singular learning theory. J Mach Learn Res. 2010; 11, 3571–3594.

- Montgomery DC, Peck EA, Vining GG. Introduction to linear regression analysis. 5th ed. Wiley; 2012.

- Kutner MH, Nachtsheim CJ, et al. Applied Linear Regression Models. McGraw-Hill; 2004.

- Draper NR, Smith H. Applied regression analysis. 3rd ed. Hoboken: Wiley; 2004.

- Cressie NAC. Statistics for Spatial Data (Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics). John Wiley & Sons; 1993.

- Dormann CF, McPherson JM, Araújo MB, et al. Methods to account for spatial autocorrelation in the analysis of species distributional data: A review. Ecography. 2007;30, 609–628. [CrossRef]

- Isaaks EH, Srivastava RM. An introduction to applied geostatistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1989. [CrossRef]

- Rue H, Riebler A, Sorbye SH, Illian JB, Simpson DP, Lindgren FK. Bayesian computing with INLA: A review. Annu Rev Stat Appl. 2017, 4, 395–421. [CrossRef]

- Haining R. Spatial Data Analysis: Theory and Practice. Cambridge University Press; 2003.

- Gamerman D, Lopes HF. Markov Chain Monte Carlo: Stochastic Simulation for Bayesian Inference. 2nd ed. Chapman and Hall/CRC Press; 2006.

- Tanser F, de Oliveira T, Maheu-Giroux M, Bärnighausen T. Concentrated HIV subepidemics in generalized epidemic settings. Lancet 2014, 384, 246–256.

- Pettifor A, MacPhail C, Hughes JP, Selin A, Wang J, Gómez-Olivé FX, et al. The effect of a conditional cash transfer on HIV incidence in young women in rural South Africa (HPTN 068): A phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health 2018, 4. [CrossRef]

- Govender K, Beckett SE, George G, et al. Factors associated with HIV in younger and older adult men in South Africa: findings from a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e031667. [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves JR, Bonell CP, Boler T, Boccia D, Birdthistle I, Fletcher A, Pronyk PM, Glynn JR. Systematic review exploring time trends in the association between educational attainment and risk of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS 2008, 22, 403–414.

- Mabaso M, Makola L, Naidoo I, et al. HIV prevalence in South Africa through gender and racial lenses: results from the 2012 population-based national household survey. Int J Equity Health 2019, 18, 167. [CrossRef]

- Worede JB, Mekonnen AG, Aynalem S, Amare NS. Risky sexual behavior among people living with HIV/AIDS in Andabet district, Ethiopia: Using a model of unsafe sexual behavior. Front Public Health 2022, 10, 1039755.

- Mishra V, Assche SBV. HIV infection does not disproportionately affect the poorer in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS 2007, 21, S17–S28. [CrossRef]

- Ugwu CLJ, Ncayiyana JR. Spatial disparities of HIV prevalence in South Africa: Do sociodemographic, behavioral, and biological factors explain this spatial variability? Front Public Health 2022, 10, 994277.

- Mah TL, Halperin DT. Concurrent sexual partnerships and the HIV epidemics in Africa: Evidence to move forward. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(1):11–16.

- Wondmeneh TG, Wondmeneh RG. Risky sexual behaviour among HIV-infected adults in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2023, 2023.

- Fisher JC, Bang H, Kapiga SH. The association between HIV infection and alcohol use: A systematic review and meta-analysis of African studies. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 2007, 34, 856–863.

- Duko, B., Ayalew, M.; Ayano, G. The prevalence of alcohol use disorders among people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 14, 52 (2019).

- Shuper PA, Joharchi N, Rehm J. Lower blood alcohol concentration among HIV-positive versus HIV-negative individuals following controlled alcohol administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016, 40, 1460–1465.

- World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2021. 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int.

- Pillay K, Gardner M, Gould A, Otiti S, Mullineux J, Bärnighausen T, et al. Long term effect of primary health care training on HIV testing: A quasi-experimental evaluation of the Sexual Health in Practice (SHIP) intervention. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0199891. [CrossRef]

- Moyo F, Mazanderani AH, Murray T, Technau KG, Carmona S, Kufa T, et al. Characterizing viral load burden among HIV-infected women around the time of delivery: findings from four tertiary obstetric units in Gauteng, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020, 83, 390–396. [CrossRef]

- UNAIDS. Global HIV & AIDS statistics — 2020 fact sheet. 2020. Available from: https://www.unaids.org.

- Mishra V, Bignami-Van Assche S, Greener R, et al. The Effect of HIV on Adult Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Comparison of Two Approaches. AIDS 2009, 23, 1617–1627.

- Harling G, Morris KA, Manderson L, Perkins JM, Berkman LF. Age and gender differences in social network composition and social support among older rural South Africans: Findings from the HAALSI study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020, 75, 148–159. [CrossRef]

| Covariate | n = 1576 | HIV Prevalence (%) | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | -Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | |||||

| 15–19 | 88 | 20.4 | 16.8 | 24.5 | <0.0001 |

| 20–24 | 399 | 37.0 | 34.2 | 40.0 | |

| 25–29 | 546 | 54.0 | 50.8 | 57.1 | |

| 30–34 | 543 | 67.5 | 64.2 | 70.8 | |

| Ever Pregnant | |||||

| No | 282 | 37.4 | 33.9 | 40.9 | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 1294 | 50.4 | 48.4 | 52.3 | |

| Education Level | |||||

| Complete Secondary | 737 | 44.3 | 41.9 | 46.7 | <0.0001 |

| Incomplete secondary (Grade 8-11/NTC1/2) | 660 | 52.1 | 49.3 | 54.9 | |

| No response | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 97.5 | |

| No schooling/creche/pre-primary | 45 | 55.6 | 44.1 | 66.6 | |

| Primary (Grade 1–7) | 60 | 70.6 | 59.7 | 80.0 | |

| Tertiary (Diploma/degree) | 74 | 32.9 | 26.8 | 39.4 | |

| Main Income | |||||

| No Income | 102 | 50.5 | 43.4 | 57.6 | 0.169432 |

| No response | 36 | 49.3 | 37.4 | 61.3 | |

| Other | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 97.5 | |

| Other non-farming income | 102 | 47.9 | 41.0 | 54.8 | |

| Pension or grants | 541 | 50.4 | 47.4 | 53.5 | |

| Remittance (migrant worker sending money home) | 40 | 50.0 | 38.6 | 61.4 | |

| Salary and/or wage | 748 | 44.8 | 42.4 | 47.3 | |

| Sales of farming products | 7 | 50.0 | 23.0 | 77.0 | |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Divorced | 2 | 100.0 | 15.8 | 100.0 | 0.000181 |

| Legally married | 70 | 38.0 | 31.0 | 45.5 | |

| Living together like husband and wife | 56 | 51.4 | 41.6 | 61.1 | |

| Separated, but still legally married | 2 | 100.0 | 15.8 | 100.0 | |

| Single and never been married/never lived together as husband/wife before | 1357 | 47.0 | 45.2 | 48.8 | |

| Single, but have been living with someone as husband/wife before | 86 | 63.7 | 55.5 | 71.8 | |

| Widowed | 3 | 60.0 | 14.7 | 94.7 | |

| Ever diagnosed with TB | |||||

| No | 1482 | 46.7 | 45.5 | 48.5 | 0.000365 |

| No response | 2 | 28.6 | 36.7 | 71.0 | |

| Yes | 92 | 63.0 | 54.6 | 70.8 | |

| Condom use | |||||

| No | 50 | 58.1 | 47.0 | 68.7 | 0.056253 |

| Yes | 1526 | 47.1 | 45.4 | 48.9 | |

| Number of sexual partners | |||||

| 1 | 1278 | 45.5 | 43.6 | 47.3 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | 159 | 51.6 | 45.9 | 57.3 | |

| 3+ | 139 | 67.5 | 60.6 | 73.8 | |

| Alcohol consumption | |||||

| No | 1326 | 45.8 | 43.9 | 47.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Yes | 250 | 58.5 | 53.7 | 63.3 | |

| Ever diagnosed with STI | |||||

| No | 1438 | 46.3 | 44.5 | 48.1 | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 138 | 63.0 | 56.2 | 69.4 | |

| Forced first sex | |||||

| Don’t remember | 26 | 54.2 | 39.2 | 68.6 | 0.246837 |

| No | 1503 | 47.1 | 45.4 | 48.9 | |

| Yes | 47 | 54.7 | 43.5 | 65.4 | |

| Away from home | |||||

| No | 1391 | 47.0 | 45.2 | 48.9 | 0.407053 |

| N response | 7 | 58.3 | 27.7 | 84.8 | |

| Yes | 178 | 50.1 | 44.8 | 55.5 | |

| Length in community | |||||

| Always | 1196 | 46.7 | 44.8 | 48.7 | 0.447987 |

| Moved here less than 1 year ago | 62 | 48.1 | 39.2 | 57.0 | |

| Moved here more than 1 year ago | 315 | 50.1 | 46.1 | 54.1 | |

| No response | 3 | 60.0 | 14.7 | 94.7 | |

| Accessed health care | |||||

| Did not respond | 2 | 33.3 | 4.3 | 77.7 | 0.018296 |

| No | 950 | 45.6 | 43.4 | 47.8 | |

| Yes | 624 | 50.5 | 47.7 | 53.4 | |

| Run out of money | |||||

| Did not respond | 34 | 45.9 | 34.3 | 57.9 | 0.618173 |

| No | 1206 | 47.0 | 45.1 | 49.0 | |

| Yes | 336 | 49.1 | 45.2 | 52.9 | |

| Meal cuts | |||||

| Did not respond | 28 | 40.6 | 28.9 | 53.1 | 0.515632 |

| No | 1259 | 47.5 | 45.6 | 49.4 | |

| Yes | 289 | 47.7 | 43.7 | 51.8 | |

| Summary Statistics | Moran’s Index | Geary’s C |

|---|---|---|

| Statistic | 0.7067737 | 0.2914347 |

| P-value | <2.2e-16 | <2.2e-16 |

| Expectation | −0.0003052 | 1.000000 |

| Variance | 0.0001070 | 0.0001434 |

| Standard Deviate | 68.361 | 59.176 |

| Spatial Logistic Model | DIC | pD | WAIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstructured | 4128.952 | 48.89294 | 4080.059 | 4129.874 |

| Structured | 4127.739 | 40.20267 | 4087.537 | 4128.783 |

| Covariate | OR | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.28880 | 0.0550 | 1.5174 |

| Age Group (ref: 15–19) | |||

| 20–24 | 2.3373 | 1.7914 | 3.0526 |

| 25–29 | 4.7446 | 3.6111 | 6.2339 |

| 30–34 | 9.1981 | 2.8826 | 12.2926 |

| Education (ref: Complete Secondary) | |||

| Incomplete secondary (Grade 8-11/NTC1/2) | 1.4049 | 1.1948 | 1.6520 |

| No response | 0.8001 | 0.1289 | 4.9679 |

| No schooling/creche/pre-primary | 1.7177 | 1.0650 | 2.7732 |

| Primary (Grade 1–7) | 2.6117 | 1.5968 | 4.2759 |

| Tertiary (Diploma/degree) | 0.5337 | 0.3910 | 0.7276 |

| Main Income (ref: No Income) | |||

| No response | 0.8270 | 0.4733 | 1.4448 |

| Other | 0.7929 | 0.1285 | 4.8988 |

| Other non-farming income | 0.8624 | 0.5746 | 1.2943 |

| Pension or grants | 0.8130 | 0.5945 | 1.1107 |

| Remittance | 0.9871 | 0.5764 | 1.6888 |

| Salary and/or wage | 0.7061 | 0.5215 | 0.9560 |

| Sales of farming products | 0.8146 | 0.3009 | 2.2034 |

| Marital Status (ref: Divorced) | |||

| Living together like husband and wife | 0.7305 | 0.2888 | 1.8497 |

| Legally married | 0.3708 | 0.1497 | 0.9185 |

| Single and never been married/never lived together as husband before | 0.9589 | 0,3985 | 2.3071 |

| Separated, but still legally married | 1.7807 | 0.3282 | 9.6504 |

| Single, but have been living with someone as husband before | 1.3539 | 0.5390 | 3.4008 |

| Widowed | 0.8395 | 0.2001 | 3.5184 |

| Ever pregnant (ref: No) | |||

| Yes | 1.1366 | 0.9389 | 1.3744 |

| Run out of money (ref: Did not respond) | |||

| No | 0.9646 | 0.5775 | 1.6112 |

| Yes | 0.9773 | 0.5661 | 1.6871 |

| Meal cuts (ref: Did not respond) | |||

| No | 1.3979 | 0.8245 | 2.3703 |

| Yes | 1.1972 | 0.6805 | 2.1064 |

| TB (ref: Never Suffered from TB) | |||

| No response | 0.6650 | 0.1818 | 2.4303 |

| Yes | 1.7986 | 1.2473 | 2.5935 |

| Condom Use (ref: No) | |||

| Yes | 0.5516 | 0.3482 | 0.8737 |

| Number of Sexual Partners (ref: 1) | |||

| 2 | 1.2117 | 0.9361 | 1.5683 |

| 3+ | 1.7647 | 1.2751 | 2.4449 |

| Alcohol (ref: No) | |||

| Yes | 1.6438 | 1.3100 | 2.0627 |

| STI Diagnosed (ref: No) | |||

| Yes | 1.6938 | 1.2448 | 2.3025 |

| Forced First Sex (ref: Do not remember) | |||

| No | 0.7672 | 0.4334 | 1.3566 |

| Yes | 1.0704 | 0.5283 | 2.1684 |

| Away From Home (ref: No) | |||

| No response | 1.3284 | 0.4757 | 3.7062 |

| Yes | 1.2436 | 0,9753 | 1.5857 |

| Length in Community (ref: Always) | |||

| Moved here less than 1 year ago | 1.0111 | 0.6887 | 1.4859 |

| Moved here more than 1 year ago | 0.9831 | 0.8057 | 1.2008 |

| No response | 1.6989 | 0.4378 | 6.5864 |

| Accessed Health Care (ref: Did not respond) | |||

| No | 1.2918 | 0.4404 | 3.7886 |

| Yes | 1.5762 | 0.5358 | 4.6367 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).