Introduction:

Viruses comprise a protein coat surrounding their genetic components, such as RNA or DNA. They cannot replicate on their own instead; they need a living specific host cell to replicate in by taking its metabolic machinery. HIV is one of these common viruses that replicate in our immune cells, especially T-cells, causing AIDS (2021). There is no specific vaccine for many viruses, including HIV, which is a virus that contributes to significant threats to humanity. It alters the immune cells in the human body, leading to immune deficiency (AIDS disease). Most of the conceptions of viruses and microbes describe them as harmful and contagious pathogens.

However, Viruses and microorganisms could play a beneficial role in bioprospecting applications. On the other side, their beneficial role is on the rise as represented by bacteriophages, that could be used to control multi-antimicrobial resistant bacteria (Rogovski et al., 2021). Beneficial microorganisms are in the human body, especially in large bowls. Each human body hosts ten microbial cells for every one human cell. These microorganisms help humans in many ways, such as digestion and production of vitamin K. They are also essential in synthesizing certain foods, such as bread and cheese (Stark, 2010). Hence, viruses may be used to help humans perform functions. One of these functions may be fighting other viruses. GB virus C (GBV-C) has been discovered lately. This virus did not show a known pathogenic effect. It might be considered latent, but it is not. This virus is present in a high percentage of HIV-infected individuals. Some studies have shown that GBV-C may be useful against HIV.

However, particular challenges are encountered in its usage as a treatment or even a vaccine for HIV. From 1995 to 2005, there was a debate and focused research about the GBV-C. Nonetheless, it began to diminish until 2012. Since then, no reported studies were published. Therefore, by outlining the difficulties in employing viruses as a vaccine, this article seeks to investigate the most important facts regarding GBV-C and its connection to HIV. The main goal of the current study also is to explicitly encourage the scientific community to focus on more research on the GBV-C virus by examining how bioinformatics can be used to help overcome these obstacles.

Effect of HIV on the Human Body:

Immunological Effect :

HIV devastates the immune cells by targeting T-4 lymphocytes. HIV cellular receptor is CD-4 glycoprotein on T-lymphocytes. It also affects monocytes, macrophages, and other cells. It chiefly kills CD-4 cells directly by cytotoxicity and in an indirect way through host response against infected cells. Macrophages show specific action with HIV as they act as reservoirs for the virus. HIV also causes function impairment in T-cells, B-cells, and monocytes. It may be found in our body in a latent or chronic form (Seligmann, 1990).

Clinical Stages and Symptoms of HIV :

HIV has four clinical stages in the body: clinical stage 1, clinical stage 2, clinical stage 3, and clinical stage 4.

Clinical Stage 1:

There are no apparent symptoms at this stage. However, lymphadenopathy may persist in children and adults (1970).

Clinical Stage 2:

Symptoms in adults: moderate unexplained weight loss, recurrent respiratory tract infection, herpes zoster, angular cheilitis, recurrent oral ulceration, papular pruritic eruption, fungal nail infection, and seborrheic dermatitis. In children, the symptoms differ from adults as they appear in the form of unexplained persistent hepatosplenomegaly, chronic upper respiratory tract infection, herpes zoster, linear gingival erythema, recurrent oral ulceration, papular pruritic eruption, fungal nail infection, extensive wart virus infection, extensive molluscum contagiosum, and unexplained persistent parotid enlargement (1970).

Clinical Stage 3:

In adults, symptoms appear as severe unexplained weight loss, unexplained chronic diarrhea for longer than one month, unexplained persistent fever for more than one month, persistent oral candidiasis oral hairy leukoplakia, pulmonary tuberculosis, severe bacterial infections, acute necrotizing ulcerative stomatitis, and unexplained anemia. In children, unexplained moderate malnutrition, unexplained persistent diarrhea for 14 days or more, unexplained persistent fever for more than one month, persistent oral candidiasis, oral hairy leukoplakia, pulmonary tuberculosis, severe bacterial infections, acute necrotizing ulcerative stomatitis, unexplained anemia, and symptomatic lymphoid interstitial pneumonitis (LIP) chronic HIV-associated lung disease, including bronchiectasis (1970).

Clinical Stage 4:

In adults, symptoms: HIV wasting syndrome, recurrent severe bacterial pneumonia, Chronic herpes simplex infection, esophageal candidiasis, Extrapulmonary tuberculosis, Kaposi sarcoma, Cytomegalovirus infection, and other serious symptoms. In children, pneumocystis, recurrent severe bacterial infections, cytomegalovirus infection, chronic cryptosporidiosis, chronic isosporiasis, and other severe symptoms (1970).

Clinical Latency Stage:

Acute HIV Infection:

It is the first stage of HIV infection that progresses within 2-4 weeks after infection. This stage shows flu-like symptoms. HIV replicates rapidly in this stage and spreads through the body. It attacks and kills CD-4 cells. The level of HIV in the blood during this stage is high (2021).

Chronic HIV Infection:

The Second stage of HIV is called the asymptomatic stage. HIV duplicates at a lower level at this stage, people at this stage may not have any symptoms. Chronic HIV infection may turn into AIDS in 10 or more years. HIV could be transmitted from one person to another at this stage (2021).

AIDS :

It is the third and final stage of HIV infection. It is considered the most severe stage as HIV has damaged immunity, making the body unable to fight opportunistic infections. It can be told that a person has AIDS if their CD-4 count is less than 200 cells/mm3 (2021).

Antiretroviral Therapy (ART):

ART enhances people's survival against HIV, especially in chronic infection. People who take ART for chronic infection may still be in this stage for decades and do not transmit HIV through the sexual route. If a person starts ART in the first phase, he/she may get numerous health benefits. People with AIDS who do not take ART will survive only three years (2021).

Effect on the Nervous System:

Despite using ART people are still endangered by central nervous system (CNS) issues. Brain atrophy, encephalitis, and other CNS complications may occur due to the chronic inflammation caused by HIV. Neurocognitive complications may also affect people's cognition levels and mental processes (2023). Mental health problems are common in HIV-infected people as depression and anxiety. Depression affects a person's daily life activity, and its symptoms range from mild to severe it’s the most common mental illness with HIV (2023).

Effect on the Respiratory System:

Tuberculosis (TB) is a disease that affects the lungs. It's more common to happen with people with weakened immunity. Therefore, it’s a common disease with HIV and it is considered as an AIDS-defining condition. TB is known as one of the major causes of death in HIV-infected individuals (2023).

Effect on the Liver:

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and Hepatitis C virus (HCV) are viruses like HIV, but they affect the liver causing serious problems to it. These problems may be liver cancer or liver failure. In the United States of America, one-third of HIV-infected people are co-infected with HBV or HCV (2023).

What is GB Virus C (GBV-C)?

GBV-C is a virus that enters the human body without any harm or pathogenic effect reported on the human body. It's mostly related to the Flaviviridae family, especially hepatitis C virus (HCV). It also has been found in vitro that it interferes with several positive methods in the body mechanisms in fighting the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (George & Varmaz, 2005).

History of Discovery:

Abbott Laboratories (in 1995) reported a virus in a West African patient without any similarities with hepatitis (A-E). Based on the genomic similarities between it and a previously discovered virus called GB virus A and B, they called it GB virus C (GBV-C). Concurrently, at Genelabs technologies, some investigators have uncovered a virus called Hepatitis G (HGV), which is 96% homology with GBV-C. This virus, HGV, had been found in the plasma of a patient who suffers from; chronic hepatitis (Bhattarai & Stapleton, 2012).

Epidemiology:

GBV-C comprises a positive sense-stranded RNA that encodes a single polyprotein with about 3000 amino acids. This virus epidemiology is still a topic of research. However, the current information indicates that antibodies for GBV-C don’t appear until its RNA is no longer detected in the body. Moreover, this virus has a high prevalence in the general population as it presents in (1.7%-2%) of the total population and in 39% of HIV-infected persons (Zhang et al., 2006). The virus occurrence has been associated with many diseases as it has been found that patients suffer from liver cirrhosis and HCC gives positive for GBV-C RNA, and in almost 20% of patients with hematological malignancies, the bone marrow cells were found to be infected with GBV-C virus. On the other hand, when the patient with cirrhosis or HCC has a liver transplant there weren’t any signs for GBV-C (Mulrooney-Cousins & Michalak, 2017). There was a study in Denmark, that was constructed to study the root of transmission of GBV-C and the risk factors for it. In this study, children between ages 9 and 15, blood donors, hospital employees, and prisoners injecting and not injecting drugs were tested by two methods: RT-PCR in-house for GBV-CRNA, and ELISA for anti-E2. Revealed that: 1.4% of the total (901) children, 2.2% of the total (5203) blood donors, 2.2% of the total (1432) hospital employees, 12.5% of the total (407) non-injecting drug prisoners, and 34.9% of the total (407) drug injecting prisoners showed a positive for GBV-CRNA. In professions, independent risk factors of blood exposure and sexual patterns were confirmed. In prisoners, independent risk factors of injecting and sexual risk factors were ensured. In children, it is found that it occurs due to birth in childhood, causing chronic infection. In adulthood, the sexual route is more relevant to occur. (Christensen et al., 2003)

Evolution of GBV-C:

The viral composition of this virus differs from most known RNA viruses that lack the proofreading enzymes to assure the commitment of RNA genome replication as it is composed of enveloped positive-strand RNA with a genomic size of about 9.3 kilobases. It also contains a large open reading frame (ORF) that encodes a single polyprotein: structural proteins are (E1 and E2), and nonstructural ones are (NS2, NS3, NS4, NS5A, and NS5B) they are located at the N-terminal and C-terminal respectively. A study was constructed to determine the history of this virus by making several phylogenic analyses of it. These analyses confirmed its ancient African evolutionary history. By analyzing different isolates for the virus, it has found closely related Southeast Asian isolates related to those of African ones (Pavesi, 2001).

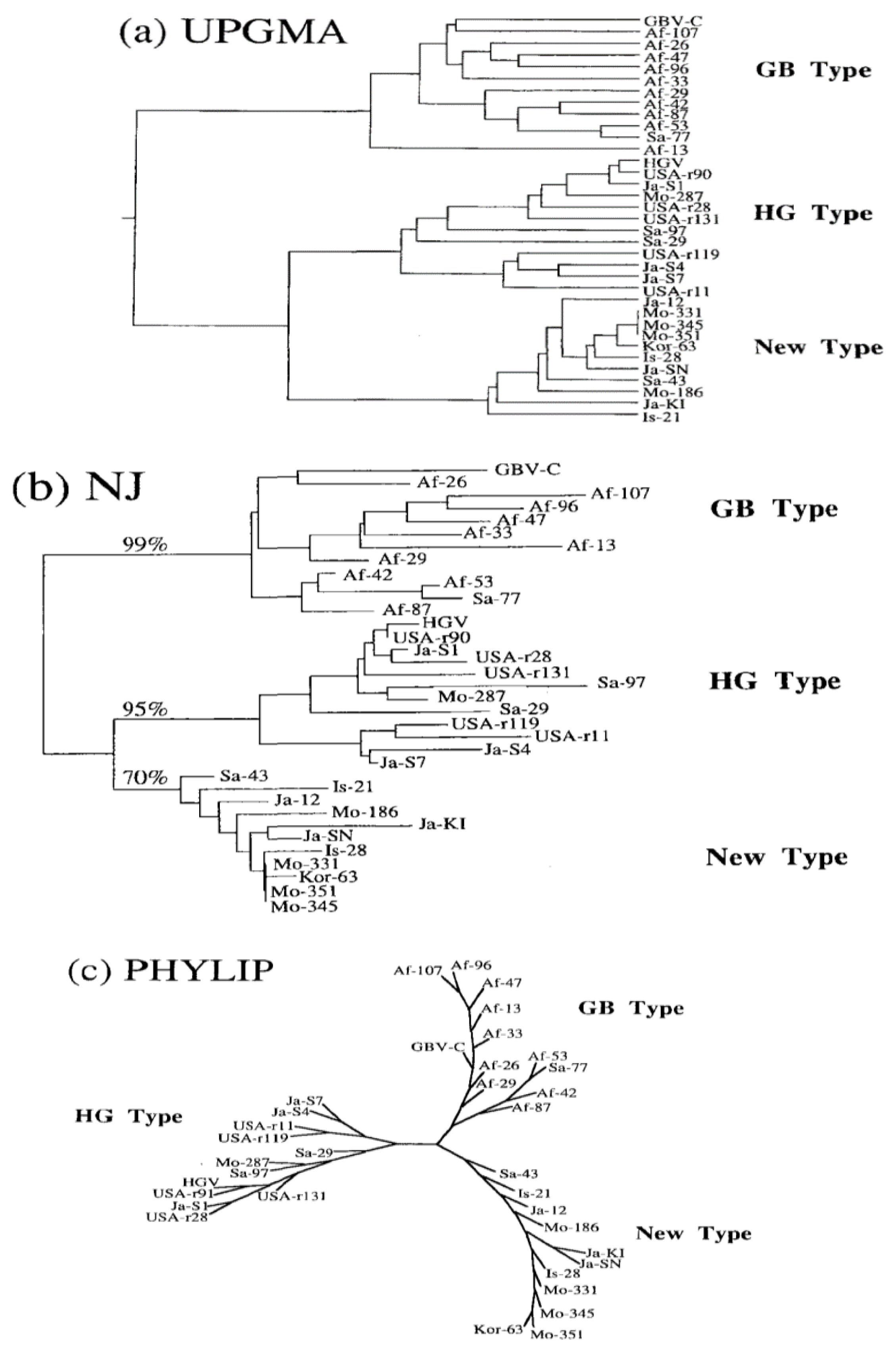

Figure 1.

shows three phylogenetic trees for GBV-C.

Figure 1.

shows three phylogenetic trees for GBV-C.

Different Strains for GBV-C:

Understanding different strains of any virus will help identify its effect on the human body. Hence, being aware of its impact on HIV. GBV-C is like any virus that includes different strains. In 1997, a group of scientists decided to design a study to know different strains of the GBV-C. Thus, they constructed a phylogenetic analysis based on restriction fragment length polymorphism. The 5’-untranslated region (5’-UTR) sequences of 33 GB Virus C(HGV), were obtained from different locations. These sequences were determined through reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and dideoxy termination sequencing. GBV-C was from West Africa, and HGV was from US patients. Phylogenetic trees were constructed based on all three accepted methods: UPGMA, Nj, and PHYLIP. Based on all three strategies of trees, there was a phylogenetic relationship between them. The isolates were separated into three phylogenetic branches (or genotypes) of three strains: GB virus C, Hepatitis G virus, and an unknown strain that hasn’t been reported before. GB-type was obtained from Africa and Saudi Arabia, hepatitis G was obtained from isolates from the United States of America, Mongolia, and Japan, and the new strain was from Korea and Israel. As shown in figure (1), the three trees they constructed to illustrate their foundations were Af for Africa, Sa for Saudi Arabia, USA for the United States of America, Mo for Mongolia, Ja for Japan, Kor for Korea, and Is for Israel. However, there was a promising homology between isolates of one type, 87.4%-98.4% in GB, 88.0%-98.9% for HGV, and 94%-99.5% in the new type. On the other hand, the homology between different types was lower,70.9%-84.1% between GBV and HGV, 83.1%-91.3% between HGV and the un-covered type, and 79.1%-89.0% between GBV-C and the new type (Mukaide et al., 1997).

Hepatitis G Virus (HGV) and Liver Disease:

HGV can be considered another name for GBV-C, but it is one of its strains with 70.9%-84.1% homology as mentioned before. After studying the virus, it has been proven that it is non-A-E hepatitis and does not produce any immune reaction. In 1999, a study designed to investigate the effect of HGV. The study was conducted on fifty patients with cirrhosis who are non-alcoholic and on 50 healthy blood donors as a control group. It is done by reverse transcription and nested polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). HGV was detected in six (12%) of cirrhosis patients and 2 (4%) of healthy blood donors. Of six infected HGV, two were coinfected with HBV, 1 with HCV, and the remaining did not belong to the B or C category. No difference has been observed between HGV-positive and HGV-negative individuals. Most studies haven’t found any relation between liver disease and HGV. However, it doesn’t mean that it isn’t a pathogenic virus. It may play a role in specific diseases that have not been discovered yet (Ramia& Al Faleh, 1999) & (Jain et al., 1999).

GBV-C Effect on Immunity and Its Relationship with HIV:

Several studies have proved the beneficial effect on HIV-infected individuals directly and indirectly. In 2009, a study demonstrated a comparison between co-infected patients with HIV and GBV-C As well as individuals with HIV only. They proved that people with GBV-C showed a lower percentage of T-cells positive for CD-38, CD-4, CD-8, and CCR-5 than patients who have HIV only. Furthermore, lower CD-38 on T-cells positive for CD-4 or CD-8 than infected individuals with HIV only, and lower CCR-5 on T-cells positive for CD-8 than patients with HIV only. In addition, they proved a total reduction in CD-4 and CD-8 positive T-cell activation (Maidana-Giret et al., 2009). In 2012, a study showed that expression of Ki-67 proliferative marker coding protein was lower in individuals co-infected with GBV-C and HIV than in patients with HIV only. In the same year, another study showed the effect of GBV-C envelope glycoprotein E2 on IL-2 receptor signaling and T-cell receptor-mediated signaling. GBV-C does not affect non-simulated cells. However, it decreases activation in positive CD-4 and CD-8 T-cells. Therefore, it reduces immune activation without its blockage (Bhattarai et al., 2012). In 2013, a study investigating HIV stated that HIV increases global immune activation by increasing microbial translocation, which leads to exposure of these cells to endotoxin and other cytokines (Klatt et al., 2013). In the same year, a group of scientists proved that GBV-C reduces natural killer cells (NK) and monocytes and a trend toward B-cells activation. Hence, by decreasing HIV entrance to the cells, global immune reduction will happen in NK, monocytes, and in their study, they proved a reduction in B-cells associated with GBV-C (Stapleton et al., 2013). The investigators supported their study by a foundation in 2005 in which a study found GBV-C replicating in B-cells positive for CD-19, suggesting that GBV-C is a pan-lymphotropic virus (George et al., 2006).

Challenges to Using GBV-C as a Vaccine for HIV:

Several challenges face the usage of GBV-C as a vaccine and using any virus as a vaccine in general. When using a vaccine including a virus it faces ethical and regulatory issues. Ensuring vaccine safety involves many trials on many bodies before its public use. Moreover, the public acceptance of injecting a virus into their body is still a significant concern. Despite curing another virus, most people are afraid of viruses and microorganisms. These challenges face any potential for the safe use of a virus. However, there are more specific challenges with using GBV-C. Safety and efficiency must be ensured before injecting it into the human body. Even though no study has found a harmful effect for the virus, it does not mean it's 100% safe because there is a lack of studies on its impact on the human body. In addition, most studies are old, the latest in 2012. Past studies indicated that the mechanism of action for GBV-C against HIV is not fully understood and needs further research. Also, the immunogenicity of the virus is significant. It must produce a strong effect and immune response specific to HIV only, not a general immune activation, as general immune activation can cause serious issues.

Furthermore, there is a tremendous variability in HIV strains. HIV has two types: type 1 and type 2. Type 1 has six different strains and clades (Verma et al., 2012). Thus, GBV-C must protect the body against all these strains. Production and delivery of a vaccine containing a virus is also a concern. In addition, the logistic transportation of a vaccine containing a virus is a concern. Addressing these challenges requires comprehensive research, practical trials, and considering scientific and ethical issues.

Role of Bioinformatics in Helping to Overcome Some of These Challenges:

Bioinformatics can play a critical position in growing a secure and influential vaccine for HIV by leveraging the genomic and proteomic information of numerous viruses, inclusive of GBV-C (a virulent disease intently associated with HIV) through multiple methods (Mount, 2006).

The first technique is Comparative Genomics: By evaluating the genomic sequences of GBV-C and HIV, conserved areas and variations may be identified. This evaluation facilitates information on how GBV-C would contribute to immune responses and which viral additives are conserved or range among those viruses. Such insights can manual the layout of vaccine antigens which are much more likely to elicit the most significant immune reaction (Setubal, Stadler, & Stoye, 2024). By Vaccine Target Identification bioinformatics gear can examine the protein sequences of GBV-C and HIV to pick out ability vaccine goals. This consists of figuring out epitopes that are shared among GBV-C and HIV. These goals may be used to lay out vaccines that initiate an immune reaction in opposition to HIV through leveraging cross-reactive immunity (Martini et al., 2019).

The second technique is Epitope Mapping: advanced bioinformatics techniques, including peptide-MHC binding prediction gear, can assist in picking out epitopes that are probable to elicit a robust immune reaction. These gears anticipate which components of the GBV-C and HIV proteins are more likely to be identified through the immune system, helping in determining the satisfactory applicants for vaccine improvement (Martini et al., 2019). In addition, Modeling how the immune machine interacts with GBV-C and HIV on the molecular degree can offer insights into how an HIV vaccine might be designed to elicit a defensive immune reaction. This consists of; information on how viral proteins interact with immune cells and predicting how interactions might be inspired through vaccine-brought immunity (Martini et al., 2019).

The third technique is structural bioinformatics: structural bioinformatics can provide information on the 3-D systems of GBV-C and HIV proteins. By reading those systems, conformational epitopes and the ability for vaccine improvement may be identified. This information may be used to lay out vaccines that mimic those systems, thereby improving the probability of an emphatic immune reaction (Mohan, 2019). Combining information from numerous sources, which includes genomic, proteomic, and medical information, can offer a complete view of the way GBV-C and HIV interact with the host. This incorporated method facilitates figuring out styles and correlations that may be used to lay out more secure and extra-powerful vaccines. Moreover, bioinformatics methods may be used to predict how distinct vaccine applicants would possibly carry out primarily based totally on ancient information and simulations. This can consist of predicting ability aspect effects, efficacy, and the probability of cross-reactivity with HIV.

The fourth technique is Vaccine Design and Optimization: Using bioinformatics, artificial vaccines primarily based totally on GBV-C sequences and checking out their efficacy in silico earlier than shifting to moist lab experiments may be designed. This method can assist in optimizing vaccine constructs and lowering the time and value of vaccine improvement (Thomas, 2022). So, integrating those bioinformatics approaches, advancing the refinement of HIV vaccines, and making them more secure and extra powerful through leveraging insights received from GBV-C studies should be of great attention for research.

Conclusions:

GBV-C is a pan-lymphotropic virus. It presents (1.7-2%) of the world population and 39% of HIV-infected persons. GBV-C has three different strains: GBV-C, HGV, and non-studied ones. Each strain presents with a higher percentage in certain places of the world. Thus, hepatitis G virus (HGV) is a misleading name because it isn’t related to any hepatitis viruses. Its evolutionary history confirms a major route for migration for ancient humans from Africa to Southeast Asia. Because of its significant effect on the immune system, it has a counter-effect to HIV as it reduces the global immunity activation in HIV-infected patients. Hence, it may be advantageous in patients with HIV. It does not treat HIV, or there are no studies stating that it treats HIV, but it may prolong the survival of infected individuals. Thus, more studies could be able to use this virus in a certain way. Even its protein envelope, because the virus is not well studied yet and may cause harmful effects on the body. Its glycoprotein, E2, has a role in interfering with IL-2 signaling and T-cell receptor-mediated signaling. Hence, by further studies investigating all possible effects on the body, the viral protein envelope may be used as a vaccine against HIV or a drug that enhances survival against it. However, there are significant issues with using this virus in a vaccine for HIV. Moreover, there is a lack of information about the virus and the most updated study was in 2013. Nevertheless, bioinformatics principles could be applied to solve these issues. Techniques that could be used are comparative genomics, epitope mapping, structural bioinformatics, and vaccine design and optimization. The most crucial conclusion is to use bioinformatics to overcome vaccine design problems. Further research on how to apply these methods to GBV-C and HIV will be valuable.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Availability of Data and Material

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

Acknowledgment

I wish to thank my friend and fellow medicine student, Yousef Ahmed Ismail, for his constant encouragement and insightful feedback, which significantly contributed to the refinement of the paper.

Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

For this type of study formal consent is not required. This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Consent for Publication

Not Applicable

List of Abbreviations:

| 1 |

GBV-C - GB virus C |

| 2 |

HCV - Hepatitis C virus |

| 3 |

HBV - Hepatitis B Virus |

| 4 |

RNA - Ribonucleic acid |

| 5 |

HIV - Human immunodeficiency virus |

| 6 |

AIDS - Acquired immune deficiency syndrome |

| 7 |

ORF - Open reading frame |

| 8 |

ELISA - Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| 9 |

RT-PCR - Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| 10 |

CD - Cluster of differentiation (e.g., CD-4, CD-8) |

| 11 |

UPGMA - Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic mean |

| 12 |

NJ - Neighbor-joining |

| 13 |

PHYLIP - Phylogeny Inference Package |

| 14 |

USA - United States of America |

| 15 |

Mo - Mongolia |

| 16 |

Ja – Japan |

| 17 |

Kor – Korea |

| 18 |

Is – Israel |

| 19 |

IL-2 - Interleukin-2 |

| 20 |

NK - Natural killer cells |

| 21 |

B-cells - B lymphocytes |

| 22 |

ART - Antiretroviral Therapy |

| 23 |

CNS - Central Nervous System |

| 24 |

CD - Cluster of Differentiation |

| 25 |

HGV - Hepatitis G Virus |

| 26 |

LIP - Lymphoid Interstitial Pneumonitis |

| 27 |

RT-PCR - Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| 28 |

TB - Tuberculosis |

| 29 |

UTR - Untranslated Region |

References

- Bhattarai, N., & Stapleton, J. T. (2012). GB virus C: The good boy virus? Trends in Microbiology, 20(3), 124–130. [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, N., McLinden, J. H., Xiang, J., Kaufman, T. M., & Stapleton, J. T. (2012). GB virus C envelope protein E2 inhibits TCR-induced IL-2 production and alters IL-2–signaling pathways. The Journal of Immunology, 189(5), 2211–2216. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, P. B., Fisker, N., Mygind, L. H., Krarup, H. B., Wedderkopp, N., Varming, K., & Georgsen, J. (2003). GB Virus C Epidemiology in Denmark: Different routes of transmission in children and low- and high-risk adults. Journal of Medical Virology, 70(1), 156–162. [CrossRef]

- George, S. L., & Varmaz, D. (2005). What you need to know about GB virus C. Current Gastroenterology Reports, 7(1), 54–62. [CrossRef]

- George, S. L., Varmaz, D., & Stapleton, J. T. (2006). GB virus C replicates in primary T and B lymphocytes. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 193(3), 451–454. [CrossRef]

- Jain, A., Kar, P., Gopalkrishna, V., Gangwal, P., Katiyar, S., & Das, B. C. (1999). Hepatitis G virus (HGV) infection & its pathogenic significance in patients of cirrhosis. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 110, 37–42.

- Klatt, N. R., Funderburg, N. T., & Brenchley, J. M. (2013). Microbial translocation, immune activation, and HIV disease. Trends in Microbiology, 21(1), 6–13. [CrossRef]

- Maidana-Giret, M. T., Silva, T. M., Sauer, M. M., Tomiyama, H., Levi, J. E., Bassichetto, K. C., Nishiya, A., Diaz, R. S., Sabino, E. C., Palacios, R., & Kallas, E. G. (2009). GB virus type C infection modulates T-cell activation independently of HIV-1 viral load. AIDS, 23(17), 2277–2287. [CrossRef]

- Martini, S., Nielsen, M., Peters, B., & Sette, A. (2019). The Immune Epitope Database and Analysis Resource Program 2003–2018: Reflections and outlook. Immunogenetics, 72(1–2), 57–76. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, C. G. (2019). Structural bioinformatics: Applications in preclinical drug discovery process. Springer.

- Mount, D. W. (2006). Bioinformatics: Sequence and Genome Analysis. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

- Mukaide, M., Mizokami, M., Orito, E., Ohba, K., Nakano, T., Ueda, R., Hikiji, K., Iino, S., Shapiro, S., Lahat, N., Park, Y.-M., Kim, B.-S., Oyunsuren, T., Rezieg, M., Al-Ahdal, M. N., & Lau, J. Y. N. (1997). Three different GB virus C/hepatitis G virus genotypes. FEBS Letters, 407(1), 51–58. [CrossRef]

- Mulrooney-Cousins, P. M., & Michalak, T. I. (2017). Molecular testing in hepatitis virus related disease. Diagnostic Molecular Pathology, 63–73. [CrossRef]

- Other health issues & affects for people living with HIV. (2023, September 15). HIV.gov. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/staying-in-hiv-care/other-related-health-issues/other-health-issues-of-special-concern-for-people-living-with-hiv.

- Pavesi, A. (2001). Origin and evolution of GBV-C/Hepatitis G virus and relationships with ancient human migrations. Journal of Molecular Evolution, 53(2), 104–113. [CrossRef]

- Ramia, S., & Al Faleh, F. Z. (1999). Hepatitis G virus (HGV) and liver diseases. Saudi Journal of Gastroenterology: Official Journal of the Saudi Gastroenterology Association, 5(2), 50–55.

- Rogovski, P., Cadamuro, R. D., da Silva, R., de Souza, E. B., Bonatto, C., Viancelli, A., Michelon, W., Elmahdy, E. M., Treichel, H., Rodríguez-Lázaro, D., & Fongaro, G. (2021). Uses of bacteriophages as bacterial control tools and environmental safety indicators. Frontiers in Microbiology, 12. [CrossRef]

- Seligmann, M. (1990a). 2 immunological features of human immunodeficiency virus disease. Baillière’s Clinical Haematology, 3(1), 37–63. [CrossRef]

- Setubal, J. C., Stadler, P. F., & Stoye, J. (2024). Comparative genomics: Methods and protocols. Humana Press.

- Stark, L. A. (2010). Beneficial microorganisms: Countering microbephobia. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 9(4), 387–389. [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, J. T., Martinson, J. A., Klinzman, D., Xiang, J., Desai, S. N., & Landay, A. (2013). GB virus C infection and B-cell, Natural Killer Cell, and monocyte activation markers in HIV-infected individuals. AIDS, 27(11), 1829–1832. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S. (2022). Vaccine design. Volume 1, Vaccines for human diseases: Methods and protocols. Humana Press.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021a, August 4). The HIV life cycle. National Institutes of Health. https://hivinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv/fact-sheets/hiv-life-cycle.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021b, August 20). The stages of HIV infection. National Institutes of Health. https://hivinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv/fact-sheets/stages-hiv-infection.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2023, November). HIV and AIDS and mental health. National Institute of Mental Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/hiv-aids#part_2498.

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. (1970, January 1). Who clinical staging of HIV disease in adults, adolescents and children. Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach, 2nd edition. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK374293/.

- Verma, A., Singh, U., Mallick, P., Dwivedi, P., & Singh, A. (2012). NeuroAIDS and Omics of HIVvpr.

- Zhang, W., Chaloner, K., Tillmann, H., Williams, C., & Stapleton, J. (2006). Effect of early and late GB virus C viraemia on survival of HIV-infected individuals: A meta-analysis. HIV Medicine, 7(3), 173–180. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).