Submitted:

05 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Pharmacologic Properties

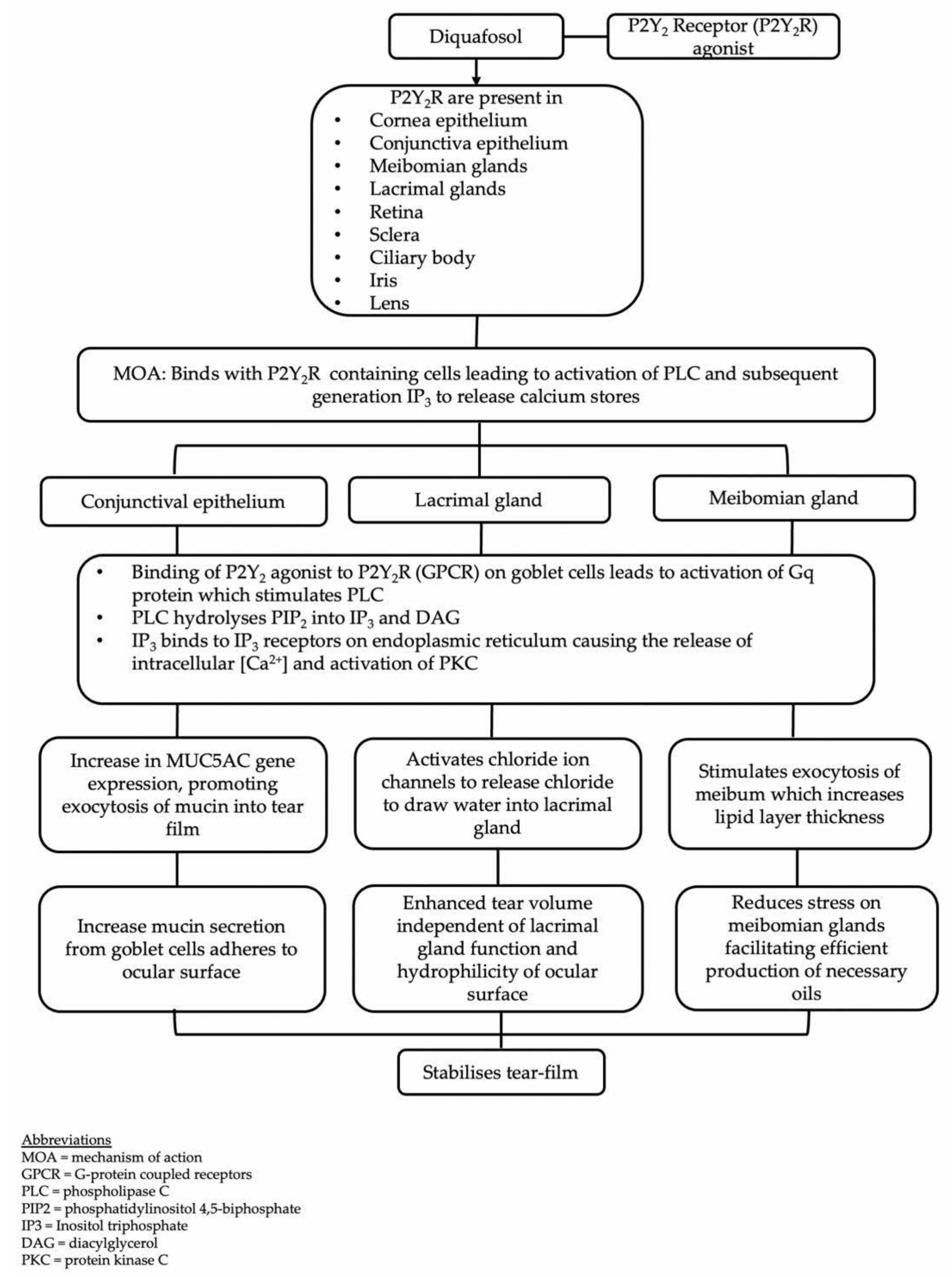

3.1. Mechanism of Action

3.2. Commercially Available Formulations

3.3. Adverse Effects

3.4. Effects on Tear Stimulation

3.5. Effects on Lipid Secretion

3.6. Effects on Mucin Secretion

4. Therapeutic Efficacy

4.1. Dry Eye Disease

4.2. Meibomian Gland Dysfunction

4.3. Aqueous-Deficient Dry Eye Disease

4.4. Ocular Graft-Versus-Host Disease (oGVHD)

4.5. Glaucoma Medication and Preservatives-Related Ocular Surface Disease

4.6. Cataract Surgery

4.7. Contact Lens Wear

4.8. Keratorefractive Surgery

4.9. Long Acting Diquafosol (DQS-LX) Formulation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D. Wu, L. Tong, A. Prasath, B. X. H. Lim, D. K. Lim, and C. H. L. Lim, “Novel therapeutics for dry eye disease,” (in eng), Ann Med, vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 1211-1212, Dec 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Cai, J. Wei, J. Zhou, and W. Zou, “Prevalence and Incidence of Dry Eye Disease in Asia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” (in eng), Ophthalmic Res, vol. 65, no. 6, pp. 647-658, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Song et al., “Variations of dry eye disease prevalence by age, sex and geographic characteristics in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” (in eng), J Glob Health, vol. 8, no. 2, p. 020503, Dec 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Uchino and D. A. Schaumberg, “Dry Eye Disease: Impact on Quality of Life and Vision,” (in eng), Curr Ophthalmol Rep, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 51-57, Jun 2013. [CrossRef]

- P. Buchholz et al., “Utility assessment to measure the impact of dry eye disease,” (in eng), Ocul Surf, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 155-61, Jul 2006. [CrossRef]

- W. Yang et al., “Estimated Annual Economic Burden of Dry Eye Disease Based on a Multi-Center Analysis in China: A Retrospective Study,” (in eng), Front Med (Lausanne), vol. 8, p. 771352, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Yu, C. V. Asche, and C. J. Fairchild, “The economic burden of dry eye disease in the United States: a decision tree analysis,” (in eng), Cornea, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 379-87, Apr 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Craig et al., “TFOS DEWS II Definition and Classification Report,” (in eng), Ocul Surf, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 276-283, Jul 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Tsubota et al., “A New Perspective on Dry Eye Classification: Proposal by the Asia Dry Eye Society,” (in eng), Eye Contact Lens, vol. 46 Suppl 1, no. 1, pp. S2-s13, Jan 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Yokoi and G. A. Georgiev, “Tear Film-Oriented Diagnosis and Tear Film-Oriented Therapy for Dry Eye Based on Tear Film Dynamics,” (in eng), Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, vol. 59, no. 14, pp. Des13-des22, Nov 1 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Nakamura, T. Imanaka, and A. Sakamoto, “Diquafosol ophthalmic solution for dry eye treatment,” (in eng), Adv Ther, vol. 29, no. 7, pp. 579-89, Jul 2012. [CrossRef]

- T. Kojima et al., “The Effects of High Molecular Weight Hyaluronic Acid Eye Drop Application in Environmental Dry Eye Stress Model Mice,” (in eng), Int J Mol Sci, vol. 21, no. 10, May 15 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Sun, L. Liu, and C. Liu, “Topical diquafosol versus hyaluronic acid for the treatment of dry eye disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials,” (in eng), Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, vol. 261, no. 12, pp. 3355-3367, Dec 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Cowlen, V. Z. Zhang, L. Warnock, C. F. Moyer, W. M. Peterson, and B. R. Yerxa, “Localization of ocular P2Y2 receptor gene expression by in situ hybridization,” (in eng), Exp Eye Res, vol. 77, no. 1, pp. 77-84, Jul 2003. [CrossRef]

- T. Murakami, T. Fujihara, Y. Horibe, and M. Nakamura, “Diquafosol elicits increases in net Cl- transport through P2Y2 receptor stimulation in rabbit conjunctiva,” (in eng), Ophthalmic Res, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 89-93, Mar-Apr 2004. [CrossRef]

- H. J. Lee et al., “Diquafosol ophthalmic solution enhances mucin expression via ERK activation in human conjunctival epithelial cells with hyperosmotic stress,” (in eng), Mol Vis, vol. 28, pp. 114-123, 2022.

- I. Jun et al., “Effects of Preservative-free 3% Diquafosol in Patients with Pre-existing Dry Eye Disease after Cataract Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial,” (in eng), Sci Rep, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 12659, Sep 2 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Matsumoto, Y. Ohashi, H. Watanabe, and K. Tsubota, “Efficacy and safety of diquafosol ophthalmic solution in patients with dry eye syndrome: a Japanese phase 2 clinical trial,” (in eng), Ophthalmology, vol. 119, no. 10, pp. 1954-60, Oct 2012. [CrossRef]

- E. Takamura, K. Tsubota, H. Watanabe, and Y. Ohashi, “A randomised, double-masked comparison study of diquafosol versus sodium hyaluronate ophthalmic solutions in dry eye patients,” (in eng), Br J Ophthalmol, vol. 96, no. 10, pp. 1310-5, Oct 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Tauber et al., “Double-masked, placebo-controlled safety and efficacy trial of diquafosol tetrasodium (INS365) ophthalmic solution for the treatment of dry eye,” (in eng), Cornea, vol. 23, no. 8, pp. 784-92, Nov 2004. [CrossRef]

- L. Gong et al., “A randomised, parallel-group comparison study of diquafosol ophthalmic solution in patients with dry eye in China and Singapore,” (in eng), Br J Ophthalmol, vol. 99, no. 7, pp. 903-8, Jul 2015. [CrossRef]

- K. Kamiya et al., “Clinical evaluation of the additive effect of diquafosol tetrasodium on sodium hyaluronate monotherapy in patients with dry eye syndrome: a prospective, randomized, multicenter study,” (in eng), Eye (Lond), vol. 26, no. 10, pp. 1363-8, Oct 2012. [CrossRef]

- H. S. Hwang, Y. M. Sung, W. S. Lee, and E. C. Kim, “Additive Effect of preservative-free sodium hyaluronate 0.1% in treatment of dry eye syndrome with diquafosol 3% eye drops,” (in eng), Cornea, vol. 33, no. 9, pp. 935-41, Sep 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Shimazaki-Den, H. Iseda, M. Dogru, and J. Shimazaki, “Effects of diquafosol sodium eye drops on tear film stability in short BUT type of dry eye,” (in eng), Cornea, vol. 32, no. 8, pp. 1120-5, Aug 2013. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ohashi et al., “Long-Term Safety and Effectiveness of Diquafosol for the Treatment of Dry Eye in a Real-World Setting: A Prospective Observational Study,” (in eng), Adv Ther, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 707-717, Feb 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Idzko, D. Ferrari, and H. K. Eltzschig, “Nucleotide signalling during inflammation,” (in eng), Nature, vol. 509, no. 7500, pp. 310-7, May 15 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. S. Peterson et al., “P2Y2 nucleotide receptor-mediated responses in brain cells,” (in eng), Mol Neurobiol, vol. 41, no. 2-3, pp. 356-66, Jun 2010. [CrossRef]

- Z. Kargarpour et al., “Blocking P2Y2 purinergic receptor prevents the development of lipopolysaccharide-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome,” (in eng), Front Immunol, vol. 14, p. 1310098, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. D. Bellefeuille, C. M. Molle, and F. P. Gendron, “Reviewing the role of P2Y receptors in specific gastrointestinal cancers,” (in eng), Purinergic Signal, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 451-463, Dec 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Elliott et al., “Nucleotides released by apoptotic cells act as a find-me signal to promote phagocytic clearance,” (in eng), Nature, vol. 461, no. 7261, pp. 282-6, Sep 10 2009. [CrossRef]

- D. Bremond-Gignac, J. J. Gicquel, and F. Chiambaretta, “Pharmacokinetic evaluation of diquafosol tetrasodium for the treatment of Sjögren’s syndrome,” (in eng), Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 905-13, Jun 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Dota, A. Sakamoto, T. Nagano, T. Murakami, and T. Matsugi, “Effect of Diquafosol Ophthalmic Solution on Airflow-Induced Ocular Surface Disorder in Diabetic Rats,” (in eng), Clin Ophthalmol, vol. 14, pp. 1019-1024, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. S. Byun et al., “Diquafosol promotes corneal epithelial healing via intracellular calcium-mediated ERK activation,” (in eng), Exp Eye Res, vol. 143, pp. 89-97, Feb 2016. [CrossRef]

- N. Yokoi, H. Kato, and S. Kinoshita, “Facilitation of tear fluid secretion by 3% diquafosol ophthalmic solution in normal human eyes,” (in eng), Am J Ophthalmol, vol. 157, no. 1, pp. 85-92.e1, Jan 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. Oguz, N. Yokoi, and S. Kinoshita, “The height and radius of the tear meniscus and methods for examining these parameters,” (in eng), Cornea, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 497-500, Jul 2000. [CrossRef]

- N. Yokoi, A. J. Bron, J. M. Tiffany, and S. Kinoshita, “Reflective meniscometry: a new field of dry eye assessment,” (in eng), Cornea, vol. 19, no. 3 Suppl, pp. S37-43, May 2000. [CrossRef]

- N. Yokoi, H. Kato, and S. Kinoshita, “The increase of aqueous tear volume by diquafosol sodium in dry-eye patients with Sjögren’s syndrome: a pilot study,” (in eng), Eye (Lond), vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 857-64, Jun 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Ikeda et al., “The effects of 3% diquafosol sodium eye drop application on meibomian gland and ocular surface alterations in the Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase-1 (Sod1) knockout mice,” (in eng), Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, vol. 256, no. 4, pp. 739-750, Apr 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. I. Endo, A. Sakamoto, and K. Fujisawa, “Diquafosol tetrasodium elicits total cholesterol release from rabbit meibomian gland cells via P2Y(2) purinergic receptor signalling,” (in eng), Sci Rep, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 6989, Mar 26 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Fukuoka and R. Arita, “Increase in tear film lipid layer thickness after instillation of 3% diquafosol ophthalmic solution in healthy human eyes,” (in eng), Ocul Surf, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 730-735, Oct 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Fukuoka and R. Arita, “Tear film lipid layer increase after diquafosol instillation in dry eye patients with meibomian gland dysfunction: a randomized clinical study,” (in eng), Sci Rep, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 9091, Jun 24 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Inatomi, S. Spurr-Michaud, A. S. Tisdale, Q. Zhan, S. T. Feldman, and I. K. Gipson, “Expression of secretory mucin genes by human conjunctival epithelia,” (in eng), Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, vol. 37, no. 8, pp. 1684-92, Jul 1996.

- I. K. Gipson, “Distribution of mucins at the ocular surface,” (in eng), Exp Eye Res, vol. 78, no. 3, pp. 379-88, Mar 2004. [CrossRef]

- F. Mantelli and P. Argüeso, “Functions of ocular surface mucins in health and disease,” (in eng), Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol, vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 477-83, Oct 2008. [CrossRef]

- Y. Jin, K. Y. Seo, and S. W. Kim, “Comparing two mucin secretagogues for the treatment of dry eye disease: a prospective randomized crossover trial,” Scientific Reports, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 13306, 2024/06/10 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Hori, T. Kageyama, A. Sakamoto, T. Shiba, M. Nakamura, and T. Maeno, “Comparison of Short-Term Effects of Diquafosol and Rebamipide on Mucin 5AC Level on the Rabbit Ocular Surface,” (in eng), J Ocul Pharmacol Ther, vol. 33, no. 6, pp. 493-497, Jul/Aug 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Terakado et al., “Conjunctival expression of the P2Y2 receptor and the effects of 3% diquafosol ophthalmic solution in dogs,” (in eng), Vet J, vol. 202, no. 1, pp. 48-52, Oct 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Liu, G. Yang, Q. Li, and S. Tang, “Safety and efficacy of topical diquafosol for the treatment of dry eye disease: An updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials,” (in eng), Indian J Ophthalmol, vol. 71, no. 4, pp. 1304-1315, Apr 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. H. Kim et al., “Effect of Diquafosol on Hyperosmotic Stress-induced Tumor Necrosis Factor-α and Interleukin-6 Expression in Human Corneal Epithelial Cells,” (in eng), Korean J Ophthalmol, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 1-10, Feb 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. T. Jung et al., “Proteomic analysis of tears in dry eye disease: A prospective, double-blind multicenter study,” (in eng), Ocul Surf, vol. 29, pp. 68-76, Jul 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Eom, J. S. Song, and H. M. Kim, “Effectiveness of Topical Cyclosporin A 0.1%, Diquafosol Tetrasodium 3%, and Their Combination, in Dry Eye Disease,” (in eng), J Ocul Pharmacol Ther, vol. 38, no. 10, pp. 682-694, Dec 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Ozdemir, S. W. J. Yeo, J. J. Lee, A. Bhaskar, E. Finkelstein, and L. Tong, “Patient Medication Preferences for Managing Dry Eye Disease: The Importance of Medication Side Effects,” (in eng), Patient, vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 679-690, Nov 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Sheppard and K. K. Nichols, “Dry Eye Disease Associated with Meibomian Gland Dysfunction: Focus on Tear Film Characteristics and the Therapeutic Landscape,” (in eng), Ophthalmol Ther, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 1397-1418, Jun 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Arita et al., “Topical diquafosol for patients with obstructive meibomian gland dysfunction,” (in eng), Br J Ophthalmol, vol. 97, no. 6, pp. 725-9, Jun 2013. [CrossRef]

- D. H. Kang et al., “Changes of tear film lipid layer thickness by 3% diquafosol ophthalmic solutions in patients with dry eye syndrome,” (in eng), Int J Ophthalmol, vol. 12, no. 10, pp. 1555-1560, 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. R. Donthineni, P. Kammari, S. S. Shanbhag, V. Singh, A. V. Das, and S. Basu, “Incidence, demographics, types and risk factors of dry eye disease in India: Electronic medical records driven big data analytics report I,” (in eng), Ocul Surf, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 250-256, Apr 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. R. Donthineni et al., “Aqueous-deficient dry eye disease: Preferred practice pattern guidelines on clinical approach, diagnosis, and management,” (in eng), Indian J Ophthalmol, vol. 71, no. 4, pp. 1332-1347, Apr 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Koh, C. Ikeda, Y. Takai, H. Watanabe, N. Maeda, and K. Nishida, “Long-term results of treatment with diquafosol ophthalmic solution for aqueous-deficient dry eye,” (in eng), Jpn J Ophthalmol, vol. 57, no. 5, pp. 440-6, Sep 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. Koh et al., “Effect of diquafosol ophthalmic solution on the optical quality of the eyes in patients with aqueous-deficient dry eye,” (in eng), Acta Ophthalmol, vol. 92, no. 8, pp. e671-5, Dec 2014. [CrossRef]

- N. Yokoi, Y. Sonomura, H. Kato, A. Komuro, and S. Kinoshita, “Three percent diquafosol ophthalmic solution as an additional therapy to existing artificial tears with steroids for dry-eye patients with Sjögren’s syndrome,” (in eng), Eye (Lond), vol. 29, no. 9, pp. 1204-12, Sep 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. Malard, E. Holler, B. M. Sandmaier, H. Huang, and M. Mohty, “Acute graft-versus-host disease,” (in eng), Nat Rev Dis Primers, vol. 9, no. 1, p. 27, Jun 8 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Sakoda et al., “Donor-derived thymic-dependent T cells cause chronic graft-versus-host disease,” (in eng), Blood, vol. 109, no. 4, pp. 1756-64, Feb 15 2007. [CrossRef]

- P. L. Surico and Z. K. Luo, “Understanding Ocular Graft-versus-Host Disease to Facilitate an Integrated Multidisciplinary Approach,” (in eng), Transplant Cell Ther, vol. 30, no. 9s, pp. S570-s584, Sep 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Yang et al., “Eyelid blood vessel and meibomian gland changes in a sclerodermatous chronic GVHD mouse model,” (in eng), Ocul Surf, vol. 26, pp. 328-341, Oct 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. L. Perez et al., “Meibomian Gland Dysfunction: A Route of Ocular Graft-Versus-Host Disease Progression That Drives a Vicious Cycle of Ocular Surface Inflammatory Damage,” (in eng), Am J Ophthalmol, vol. 247, pp. 42-60, Mar 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ogawa, S. Shimmura, T. Kawakita, S. Yoshida, Y. Kawakami, and K. Tsubota, “Epithelial mesenchymal transition in human ocular chronic graft-versus-host disease,” (in eng), Am J Pathol, vol. 175, no. 6, pp. 2372-81, Dec 2009. [CrossRef]

- K. Shamloo, A. Barbarino, S. Alfuraih, and A. Sharma, “Graft Versus Host Disease-Associated Dry Eye: Role of Ocular Surface Mucins and the Effect of Rebamipide, a Mucin Secretagogue,” (in eng), Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, vol. 60, no. 14, pp. 4511-4519, Nov 1 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Yamane et al., “Long-Term Topical Diquafosol Tetrasodium Treatment of Dry Eye Disease Caused by Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease: A Retrospective Study,” (in eng), Eye Contact Lens, vol. 44 Suppl 2, pp. S215-s220, Nov 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Yamane et al., “Long-term rebamipide and diquafosol in two cases of immune-mediated dry eye,” (in eng), Optom Vis Sci, vol. 92, no. 4 Suppl 1, pp. S25-32, Apr 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Kolko et al., “Impact of glaucoma medications on the ocular surface and how ocular surface disease can influence glaucoma treatment,” (in eng), Ocul Surf, vol. 29, pp. 456-468, Jul 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, S. Vadoothker, W. M. Munir, and O. Saeedi, “Ocular Surface Disease and Glaucoma Medications: A Clinical Approach,” (in eng), Eye Contact Lens, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 11-18, Jan 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. L. Coakes, I. A. Mackie, and D. V. Seal, “Effects of long-term treatment with timolol on lacrimal gland function,” (in eng), Br J Ophthalmol, vol. 65, no. 9, pp. 603-5, Sep 1981. [CrossRef]

- E. V. Kuppens, C. A. de Jong, T. R. Stolwijk, R. J. de Keizer, and J. A. van Best, “Effect of timolol with and without preservative on the basal tear turnover in glaucoma,” (in eng), Br J Ophthalmol, vol. 79, no. 4, pp. 339-42, Apr 1995. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, W. R. Kam, Y. Liu, X. Chen, and D. A. Sullivan, “Influence of Pilocarpine and Timolol on Human Meibomian Gland Epithelial Cells,” (in eng), Cornea, vol. 36, no. 6, pp. 719-724, Jun 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Aydin Kurna, S. Acikgoz, A. Altun, N. Ozbay, T. Sengor, and O. O. Olcaysu, “The effects of topical antiglaucoma drugs as monotherapy on the ocular surface: a prospective study,” (in eng), J Ophthalmol, vol. 2014, p. 460483, 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Nijm, L. De Benito-Llopis, G. C. Rossi, T. S. Vajaranant, and M. T. Coroneo, “Understanding the Dual Dilemma of Dry Eye and Glaucoma: An International Review,” (in eng), Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila), vol. 9, no. 6, pp. 481-490, Dec 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Mocan, E. Uzunosmanoglu, S. Kocabeyoglu, J. Karakaya, and M. Irkec, “The Association of Chronic Topical Prostaglandin Analog Use With Meibomian Gland Dysfunction,” (in eng), J Glaucoma, vol. 25, no. 9, pp. 770-4, Sep 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. P. Rabinowitz et al., “Unilateral Prostaglandin-Associated Periorbitopathy: A Syndrome Involving Upper Eyelid Retraction Distinguishable From the Aging Sunken Eyelid,” (in eng), Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg, vol. 31, no. 5, pp. 373-8, Sep-Oct 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Vitoux et al., “Benzalkonium chloride-induced direct and indirect toxicity on corneal epithelial and trigeminal neuronal cells: proinflammatory and apoptotic responses in vitro,” (in eng), Toxicol Lett, vol. 319, pp. 74-84, Feb 1 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Ivakhnitskaia et al., “Benzalkonium chloride, a common ophthalmic preservative, compromises rat corneal cold sensitive nerve activity,” (in eng), Ocul Surf, vol. 26, pp. 88-96, Oct 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Van Went et al., “[Corneal sensitivity in patients treated medically for glaucoma or ocular hypertension],” (in fre), J Fr Ophtalmol, vol. 34, no. 10, pp. 684-90, Dec 2011. [CrossRef]

- G. Martone et al., “An in vivo confocal microscopy analysis of effects of topical antiglaucoma therapy with preservative on corneal innervation and morphology,” (in eng), Am J Ophthalmol, vol. 147, no. 4, pp. 725-735.e1, Apr 2009. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Ammar, R. J. Noecker, and M. Y. Kahook, “Effects of benzalkonium chloride-preserved, polyquad-preserved, and sofZia-preserved topical glaucoma medications on human ocular epithelial cells,” (in eng), Adv Ther, vol. 27, no. 11, pp. 837-45, Nov 2010. [CrossRef]

- H. Liang, F. Brignole-Baudouin, L. Riancho, and C. Baudouin, “Reduced in vivo ocular surface toxicity with polyquad-preserved travoprost versus benzalkonium-preserved travoprost or latanoprost ophthalmic solutions,” (in eng), Ophthalmic Res, vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 89-101, 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. Y. Kahook, C. J. Rapuano, E. M. Messmer, N. M. Radcliffe, A. Galor, and C. Baudouin, “Preservatives and ocular surface disease: A review,” (in eng), Ocul Surf, vol. 34, pp. 213-224, Aug 3 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Herreras, J. C. Pastor, M. Calonge, and V. M. Asensio, “Ocular surface alteration after long-term treatment with an antiglaucomatous drug,” (in eng), Ophthalmology, vol. 99, no. 7, pp. 1082-8, Jul 1992. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Chung et al., “Impact of short-term exposure of commercial eyedrops preserved with benzalkonium chloride on precorneal mucin,” (in eng), Mol Vis, vol. 12, pp. 415-21, Apr 26 2006.

- J. M. Martinez-de-la-Casa et al., “Tear cytokine profile of glaucoma patients treated with preservative-free or preserved latanoprost,” (in eng), Ocul Surf, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 723-729, Oct 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. Boimer and C. M. Birt, “Preservative exposure and surgical outcomes in glaucoma patients: The PESO study,” (in eng), J Glaucoma, vol. 22, no. 9, pp. 730-5, Dec 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Tomić, S. Kaštelan, K. M. Soldo, and J. Salopek-Rabatić, “Influence of BAK-preserved prostaglandin analog treatment on the ocular surface health in patients with newly diagnosed primary open-angle glaucoma,” (in eng), Biomed Res Int, vol. 2013, p. 603782, 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. Huang et al., “Benzalkonium chloride induces subconjunctival fibrosis through the COX-2-modulated activation of a TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling pathway,” (in eng), Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, vol. 55, no. 12, pp. 8111-22, Nov 18 2014. [CrossRef]

- D. C. Broadway, I. Grierson, C. O’Brien, and R. A. Hitchings, “Adverse effects of topical antiglaucoma medication. II. The outcome of filtration surgery,” (in eng), Arch Ophthalmol, vol. 112, no. 11, pp. 1446-54, Nov 1994. [CrossRef]

- R. Merani et al., “Aqueous Chlorhexidine for Intravitreal Injection Antisepsis: A Case Series and Review of the Literature,” (in eng), Ophthalmology, vol. 123, no. 12, pp. 2588-2594, Dec 2016. [CrossRef]

- N. E. Epstein, “Review: Perspective on ocular toxicity of presurgical skin preparations utilizing Chlorhexidine Gluconate/Hibiclens/Chloraprep,” (in eng), Surg Neurol Int, vol. 12, p. 335, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Green, V. Livingston, K. Bowman, and D. S. Hull, “Chlorhexidine Effects on Corneal Epithelium and Endothelium,” Archives of Ophthalmology, vol. 98, no. 7, pp. 1273-1278, 1980. [CrossRef]

- M. B. Hamill, M. S. Osato, and K. R. Wilhelmus, “Experimental evaluation of chlorhexidine gluconate for ocular antisepsis,” (in eng), Antimicrob Agents Chemother, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 793-6, Dec 1984. [CrossRef]

- S. W. Jin and J. S. Min, “Clinical evaluation of the effect of diquafosol ophthalmic solution in glaucoma patients with dry eye syndrome,” (in eng), Jpn J Ophthalmol, vol. 60, no. 3, pp. 150-5, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- Y. Guo, J. Y. Ha, H. L. Piao, M. S. Sung, and S. W. Park, “The protective effect of 3% diquafosol on meibomian gland morphology in glaucoma patients treated with prostaglandin analogs: a 12-month follow-up study,” (in eng), BMC Ophthalmol, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 277, Jul 10 2020. [CrossRef]

- Q. Liu et al., “Evaluation of effects of 3% diquafosol ophthalmic solution on preocular tear film stability after trabeculectomy,” (in eng), Int Ophthalmol, vol. 43, no. 6, pp. 1903-1910, Jun 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Dasgupta, “The course of dry eye following phacoemulsification and manual - SICS: a prospective study based on Indian scenario,” International eye science, vol. 16, pp. 1789-1794, 07/12 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Miyake and N. Yokoi, “Influence on ocular surface after cataract surgery and effect of topical diquafosol on postoperative dry eye: a multicenter prospective randomized study,” (in eng), Clin Ophthalmol, vol. 11, pp. 529-540, 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Kato et al., “Conjunctival Goblet Cell Density Following Cataract Surgery With Diclofenac Versus Diclofenac and Rebamipide: A Randomized Trial,” (in eng), Am J Ophthalmol, vol. 181, pp. 26-36, Sep 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. Oh, Y. Jung, D. Chang, J. Kim, and H. Kim, “Changes in the tear film and ocular surface after cataract surgery,” (in eng), Jpn J Ophthalmol, vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 113-8, Mar 2012. [CrossRef]

- R. Yanai et al., “Evaluation of povidone-iodine as a disinfectant solution for contact lenses: antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity for corneal epithelial cells,” (in eng), Cont Lens Anterior Eye, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 85-91, May 2006. [CrossRef]

- S. P. Epstein, M. Ahdoot, E. Marcus, and P. A. Asbell, “Comparative toxicity of preservatives on immortalized corneal and conjunctival epithelial cells,” (in eng), J Ocul Pharmacol Ther, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 113-9, Apr 2009. [CrossRef]

- H. B. Hwang and H. S. Kim, “Phototoxic effects of an operating microscope on the ocular surface and tear film,” (in eng), Cornea, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 82-90, Jan 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. Ipek, M. P. Hanga, A. Hartwig, J. Wolffsohn, and C. O’Donnell, “Dry eye following cataract surgery: The effect of light exposure using an in-vitro model,” (in eng), Cont Lens Anterior Eye, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 128-131, Feb 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. E. Han et al., “Evaluation of dry eye and meibomian gland dysfunction after cataract surgery,” (in eng), Am J Ophthalmol, vol. 157, no. 6, pp. 1144-1150.e1, Jun 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Ram, A. Gupta, G. Brar, S. Kaushik, and A. Gupta, “Outcomes of phacoemulsification in patients with dry eye,” (in eng), J Cataract Refract Surg, vol. 28, no. 8, pp. 1386-9, Aug 2002. [CrossRef]

- D. H. Park, J. K. Chung, D. R. Seo, and S. J. Lee, “Clinical Effects and Safety of 3% Diquafosol Ophthalmic Solution for Patients With Dry Eye After Cataract Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” (in eng), Am J Ophthalmol, vol. 163, pp. 122-131.e2, Mar 2016. [CrossRef]

- P. Kim, S. Plugfelder, and A. R. Slomovic, “Top 5 pearls to consider when implanting advanced-technology IOLs in patients with ocular surface disease,” (in eng), Int Ophthalmol Clin, vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 51-8, Spring 2012. [CrossRef]

- W. B. Trattler, P. A. Majmudar, E. D. Donnenfeld, M. B. McDonald, K. G. Stonecipher, and D. F. Goldberg, “The Prospective Health Assessment of Cataract Patients’ Ocular Surface (PHACO) study: the effect of dry eye,” (in eng), Clin Ophthalmol, vol. 11, pp. 1423-1430, 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. T. Epitropoulos, C. Matossian, G. J. Berdy, R. P. Malhotra, and R. Potvin, “Effect of tear osmolarity on repeatability of keratometry for cataract surgery planning,” (in eng), J Cataract Refract Surg, vol. 41, no. 8, pp. 1672-7, Aug 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. Teshigawara et al., “Effect of Long-Acting Diquafosol Sodium on Astigmatism Measurement Repeatability in Preoperative Cataract Cases with Dry Eyes: A Multicenter Prospective Study,” (in eng), Ophthalmol Ther, vol. 13, no. 6, pp. 1743-1755, Jun 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Kobashi, K. Kamiya, A. Igarashi, T. Miyake, and K. Shimizu, “Intraocular Scattering after Instillation of Diquafosol Ophthalmic Solution,” (in eng), Optom Vis Sci, vol. 92, no. 9, pp. e303-9, Sep 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. Kojima, “Contact Lens-Associated Dry Eye Disease: Recent Advances Worldwide and in Japan,” (in eng), Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, vol. 59, no. 14, pp. Des102-des108, Nov 1 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Arita, K. Itoh, K. Inoue, A. Kuchiba, T. Yamaguchi, and S. Amano, “Contact lens wear is associated with decrease of meibomian glands,” (in eng), Ophthalmology, vol. 116, no. 3, pp. 379-84, Mar 2009. [CrossRef]

- Y. Nagahara et al., “Diquafosol Ophthalmic Solution Increases Pre- and Postlens Tear Film During Contact Lens Wear in Rabbit Eyes,” (in eng), Eye Contact Lens, vol. 43, no. 6, pp. 378-382, Nov 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. Shigeyasu, M. Yamada, Y. Akune, and M. Fukui, “Diquafosol for Soft Contact Lens Dryness: Clinical Evaluation and Tear Analysis,” (in eng), Optom Vis Sci, vol. 93, no. 8, pp. 973-8, Aug 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. Ogami, H. Asano, T. Hiraoka, Y. Yamada, and T. Oshika, “The Effect of Diquafosol Ophthalmic Solution on Clinical Parameters and Visual Function in Soft Contact Lens-Related Dry Eye,” (in eng), Adv Ther, vol. 38, no. 11, pp. 5534-5547, Nov 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Yang, X. Ma, L. Liu, and P. Cho, “Vision-related quality of life of Chinese children undergoing orthokeratology treatment compared to single vision spectacles,” (in eng), Cont Lens Anterior Eye, vol. 44, no. 4, p. 101350, Aug 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. D. P. Willcox et al., “TFOS DEWS II Tear Film Report,” (in eng), Ocul Surf, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 366-403, Jul 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. Xie and R. Wei, “Long-term changes in the ocular surface during orthokeratology lens wear and their correlations with ocular discomfort symptoms,” (in eng), Cont Lens Anterior Eye, vol. 46, no. 1, p. 101757, Feb 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. X. Miao, X. Y. Xu, and H. Zhang, “[Analysis of corneal complications in children wearing orthokeratology lenses at night],” (in chi), Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi, vol. 53, no. 3, pp. 198-202, Mar 11 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yang et al., “Short-term application of diquafosol ophthalmic solution benefits children with dry eye wearing orthokeratology lens,” (in eng), Front Med (Lausanne), vol. 10, p. 1130117, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. S. De Paiva et al., “The incidence and risk factors for developing dry eye after myopic LASIK,” (in eng), Am J Ophthalmol, vol. 141, no. 3, pp. 438-45, Mar 2006. [CrossRef]

- S. Nair, M. Kaur, N. Sharma, and J. S. Titiyal, “Refractive surgery and dry eye - An update,” (in eng), Indian J Ophthalmol, vol. 71, no. 4, pp. 1105-1114, Apr 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. C. Liu et al., “Comparison of tear proteomic and neuromediator profiles changes between small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) and femtosecond laser-assisted in-situ keratomileusis (LASIK),” (in eng), J Adv Res, vol. 29, pp. 67-81, Mar 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Konomi et al., “Preoperative characteristics and a potential mechanism of chronic dry eye after LASIK,” (in eng), Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 168-74, Jan 2008. [CrossRef]

- E. Cohen and O. Spierer, “Dry Eye Post-Laser-Assisted In Situ Keratomileusis: Major Review and Latest Updates,” (in eng), J Ophthalmol, vol. 2018, p. 4903831, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. W. Jung, J. Y. Kim, H. S. Chin, Y. J. Suh, T. I. Kim, and K. Y. Seo, “Assessment of meibomian glands and tear film in post-refractive surgery patients,” (in eng), Clin Exp Ophthalmol, vol. 45, no. 9, pp. 857-866, Dec 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu et al., “Combination Therapy With Diquafosol Sodium and Sodium Hyaluronate in Eyes With Dry Eye Disease After Small Incision Lenticule Extraction,” (in eng), In Vivo, vol. 37, no. 6, pp. 2829-2834, Nov-Dec 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Mori et al., “Effect of diquafosol tetrasodium eye drop for persistent dry eye after laser in situ keratomileusis,” (in eng), Cornea, vol. 33, no. 7, pp. 659-62, Jul 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. Wang, Y. Di, and Y. Li, “Combination therapy with 3% diquafosol tetrasodium ophthalmic solution and sodium hyaluronate: an effective therapy for patients with dry eye after femtosecond laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis,” (in eng), Front Med (Lausanne), vol. 10, p. 1160499, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Matsumoto, O. M. A. Ibrahim, T. Kojima, M. Dogru, J. Shimazaki, and K. Tsubota, “Corneal In Vivo Laser-Scanning Confocal Microscopy Findings in Dry Eye Patients with Sjögren’s Syndrome,” (in eng), Diagnostics (Basel), vol. 10, no. 7, Jul 20 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Uchino, N. Yokoi, J. Shimazaki, Y. Hori, K. Tsubota, and S. On Behalf Of The Japan Dry Eye, “Adherence to Eye Drops Usage in Dry Eye Patients and Reasons for Non-Compliance: A Web-Based Survey,” (in eng), J Clin Med, vol. 11, no. 2, Jan 12 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Arita, S. Fukuoka, and M. Kaido, “Tolerability of Diquas LX on tear film and meibomian glands findings in a real clinical scenario,” (in eng), PLoS One, vol. 19, no. 9, p. e0305020, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Hori, K. Oka, and M. Inai, “Efficacy and Safety of the Long-Acting Diquafosol Ophthalmic Solution DE-089C in Patients with Dry Eye: A Randomized, Double-Masked, Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Study,” (in eng), Adv Ther, vol. 39, no. 8, pp. 3654-3667, Aug 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Ishikawa, T. Sasaki, T. Maruyama, K. Murayama, and K. Shinoda, “Effectiveness and Adherence of Dry Eye Patients Who Switched from Short- to Long-Acting Diquafosol Ophthalmic Solution,” (in eng), J Clin Med, vol. 12, no. 13, Jul 5 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. H. Y. Teo, H. S. Ong, Y. C. Liu, and L. Tong, “Meibomian gland dysfunction is the primary determinant of dry eye symptoms: Analysis of 2346 patients,” (in eng), Ocul Surf, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 604-612, Oct 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Yang et al., “Quantitative evaluation of lipid layer thickness and blinking in children with allergic conjunctivitis,” (in eng), Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, vol. 259, no. 9, pp. 2795-2805, Sep 2021. [CrossRef]

| Diquas® | Diquas®-S |

|---|---|

| Chlorhexidine gluconate (preservative) Dibasic sodium phosphate hydrate Disodium edetate hydrate Sodium chloride Potassium chloride Sodium hydroxide Dilute hydrochloric acid |

Dibasic sodium phosphate hydrate Disodium edetate hydrate Sodium chloride Potassium chloride Hydrochloric acid Sodium hydroxide |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).