1. Introduction

B vitamins include 8 water-soluble vitamins that consist of thiamine (B1), riboflavin (B2), niacin (B3), pantothenic acid (B5), pyridoxine (B6), biotin (B7), folate (B9), and cobalamin (B12) [

1]. B vitamins are excreted through urine and need to be replaced daily through dairy products, leafy green vegetables or animal proteins [

1]. They are cofactors for cellular pathways supporting physiological function [

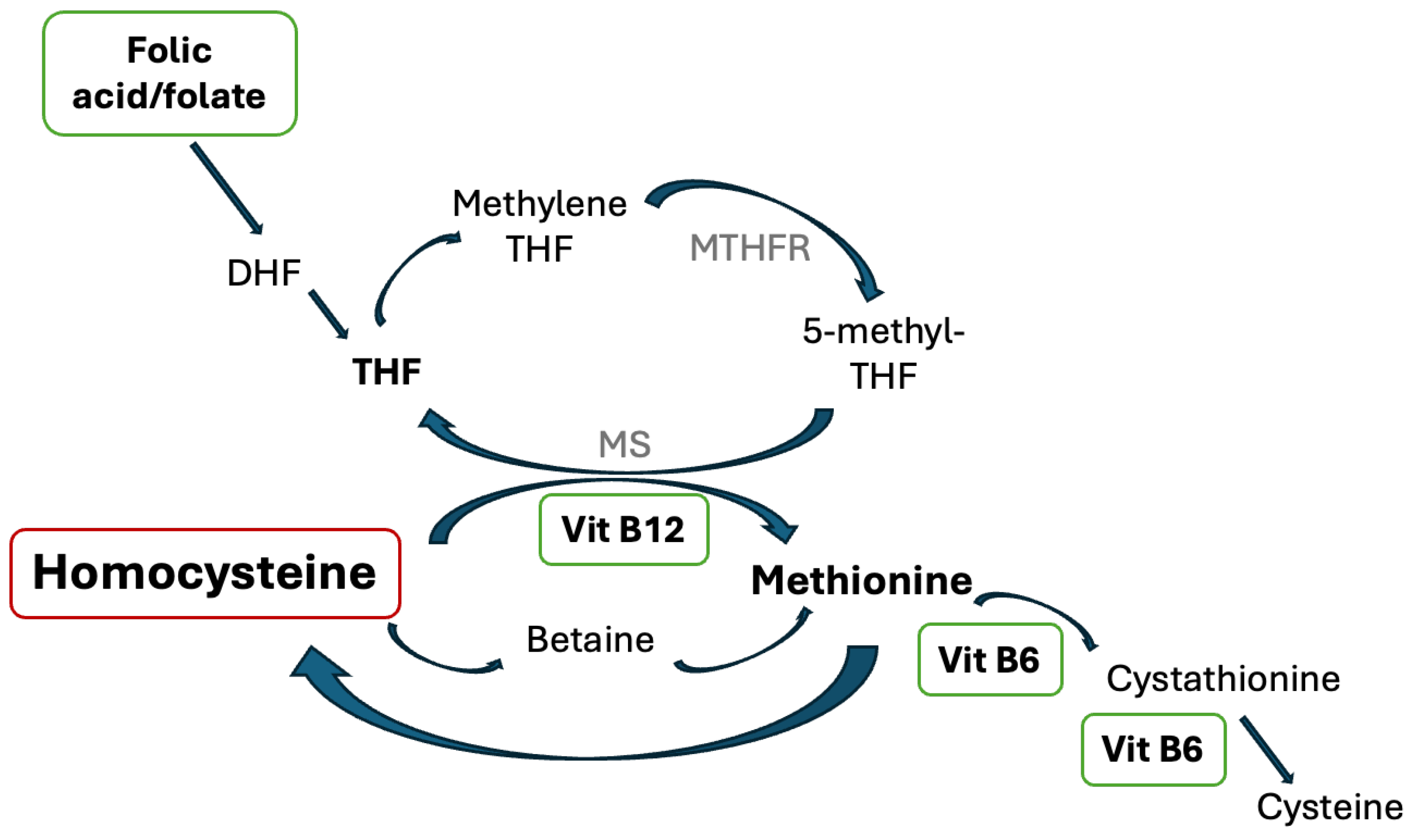

2]. Specifically, vitamin B6, B9, and B12 are involved in the homocysteine metabolic pathway and have previously shown to be associated with thrombotic risk reduction (

Figure 1) [

1,

2].

Homocysteine(Hcy) is derived from the essential amino acid methionine and is known to play a role in cellular homeostasis. Elevation of homocysteine in the plasma is linked to cardiovascular disease and venous thrombotic events [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Several studies have identified that hyperhomocysteinemia (>15 µmol/L) may negatively affect the cardiovascular system and lead to stroke, coronary artery disease, and deep vein thrombosis [

8]. The positive correlation between homocysteine level and thromboembolic risk has been shown frequently when homocysteine level is above 30 µmol/L (severe/moderate hyperhomocysteinemia) [

9,

10]. However, the modestly elevated homocysteine showed mixed results on the effect of the cardiovascular system, and thus it may not be an independent risk factor for thromboembolism when homocysteine level is between 15 to 30 µmol/L [

9]. High concentration of homocysteine in the plasma may induce oxidative damage to endothelial cells which consequently causes dysfunction of the anticoagulation system and leads to thrombotic events [

11].

Vitamin B deficiency could lead to hyperhomocysteinemia, which is an independent risk factor for thrombosis events. However, results of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of B vitamin supplementations have been inconsistent in improving clinical outcomes of arterial or venous thrombotic events. Our study aims to review currently available RCTs in the past 10 years and discuss the effects of B vitamins, mainly pyridoxine (B6), folic acid (B9), and cobalamin(B12) on clinical outcomes in reducing various arterial and venous thromboembolism events.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

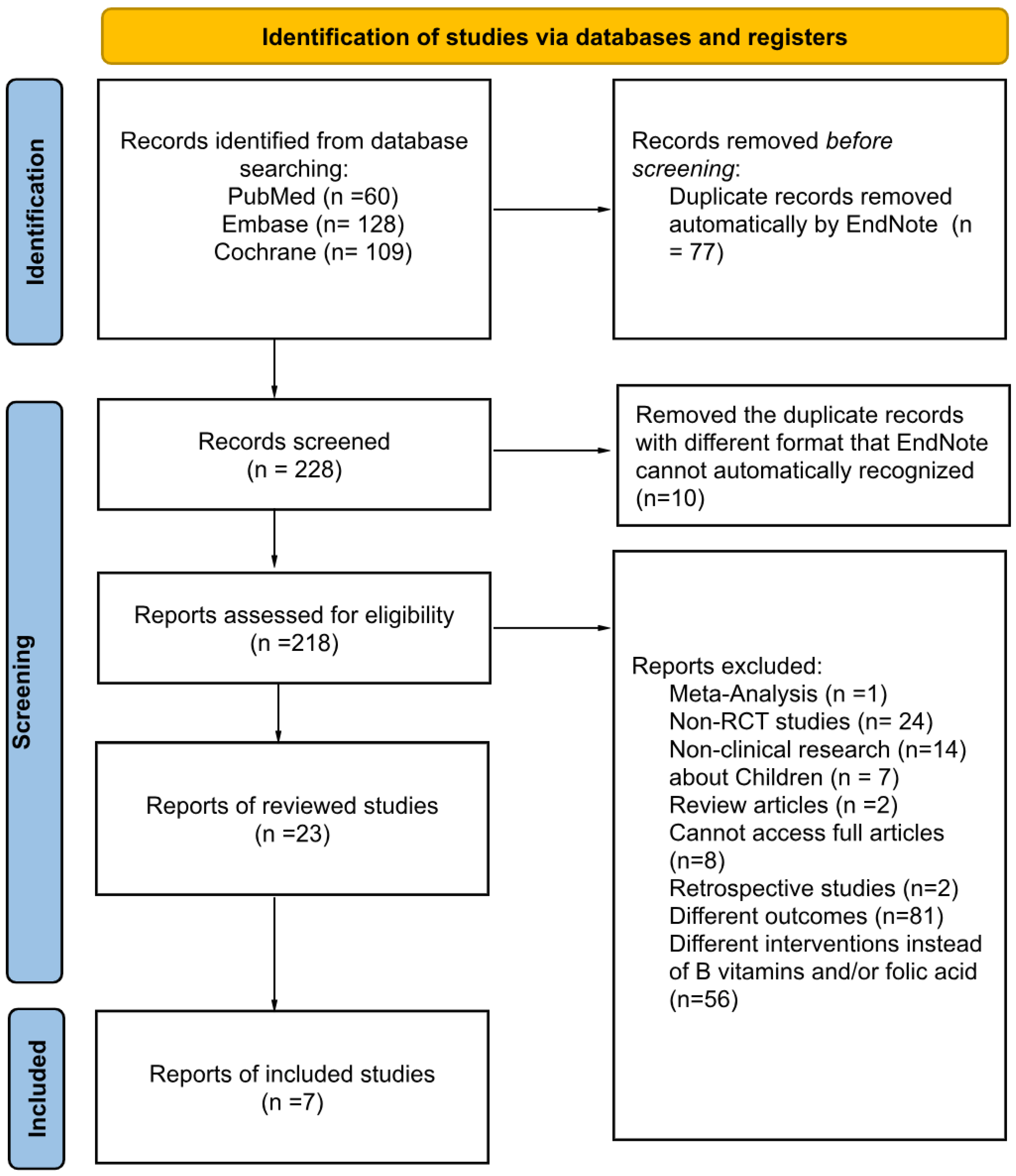

A literature research was conducted using three databases (PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane) to identify all RCTs published between January 2014 to December 2024 using predefined search terms: (vitamin B OR folate OR folic acid OR B vitamins) AND (homocysteine OR homocysteinemia OR hyperhomocysteinemia) AND (thrombosis OR thrombotic OR cardiovascular event OR stroke OR cardiovascular accident OR thromboembolism).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Trials were eligible if they corresponded to the following characteristics:

Population: adult patients (greater or equal to 18 years of age).

Intervention: oral, enteral, or parenteral folic acid (Vitamin B9) and/or cobalamin (or Vitamin B12) and/or pyridoxine (Vitamin B6) with or without standard therapy.

Outcomes: Incidence of any thrombotic events including but not limited to myocardial infarction (MI), stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), cardiovascular accident (CVA), deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE). Trials reporting only biochemical outcomes or surrogate markers were excluded.

2.3. Eligibility Review and Data Abstraction

The primary citation screening was done by using the keywords listed above in the three databases. All of the authors were independently assigned to review all citations after the primary screening. Full texts of potential studies were reviewed and study details including vitamin B regimen, study methods, results on homocysteine level, and clinical outcomes were extracted.

2.4. Qualitative Analysis

For each RCT included, two reviewers independently evaluated the methodological quality, risk of bias, and synthesis of the results. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion or third-party adjudication. No quantitative analysis was performed due to the heterogenesis of the studies.

Figure 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of study selection based on inclusion and exclusion criteria [

12]

.

Figure 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of study selection based on inclusion and exclusion criteria [

12]

.

3. Results

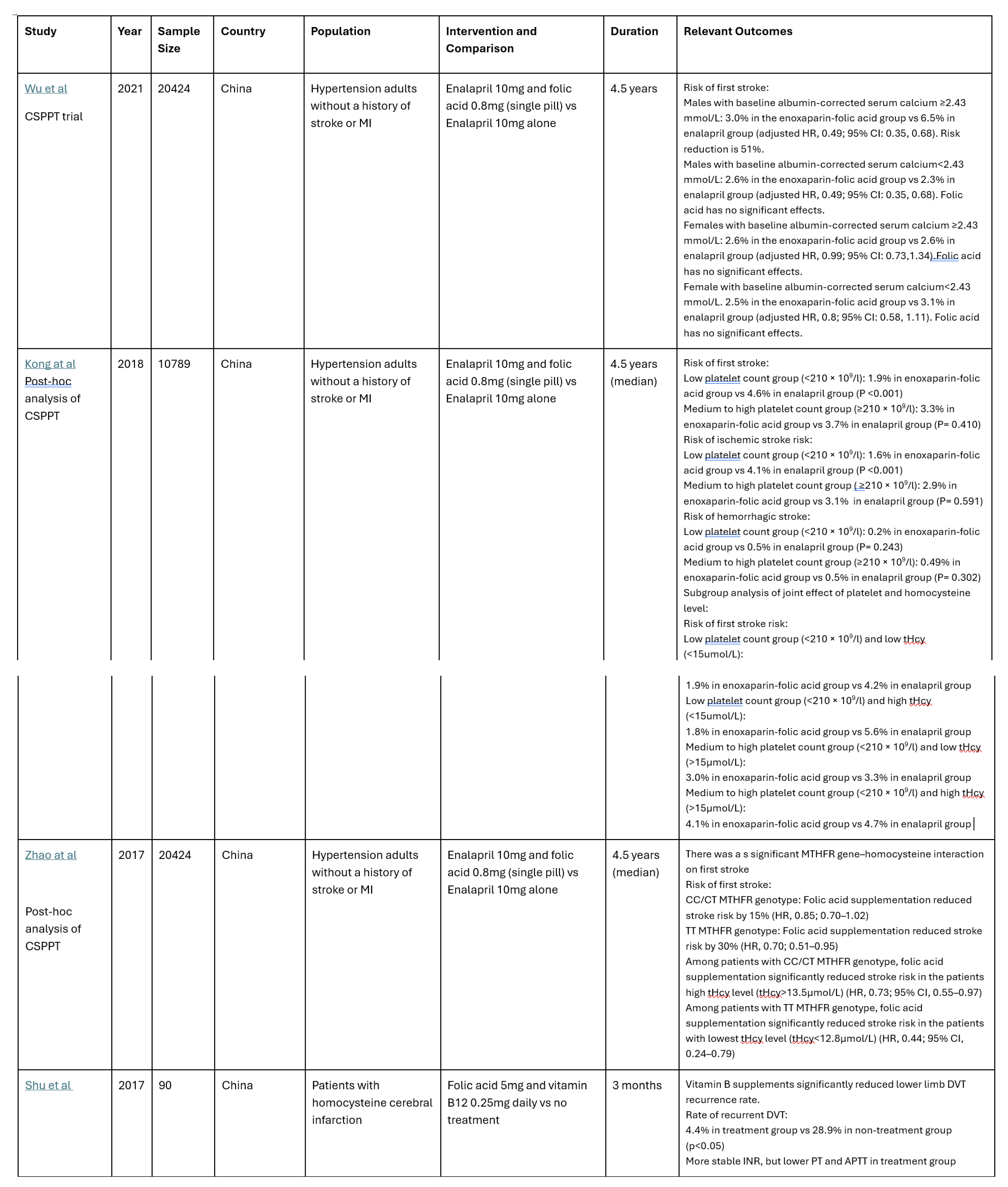

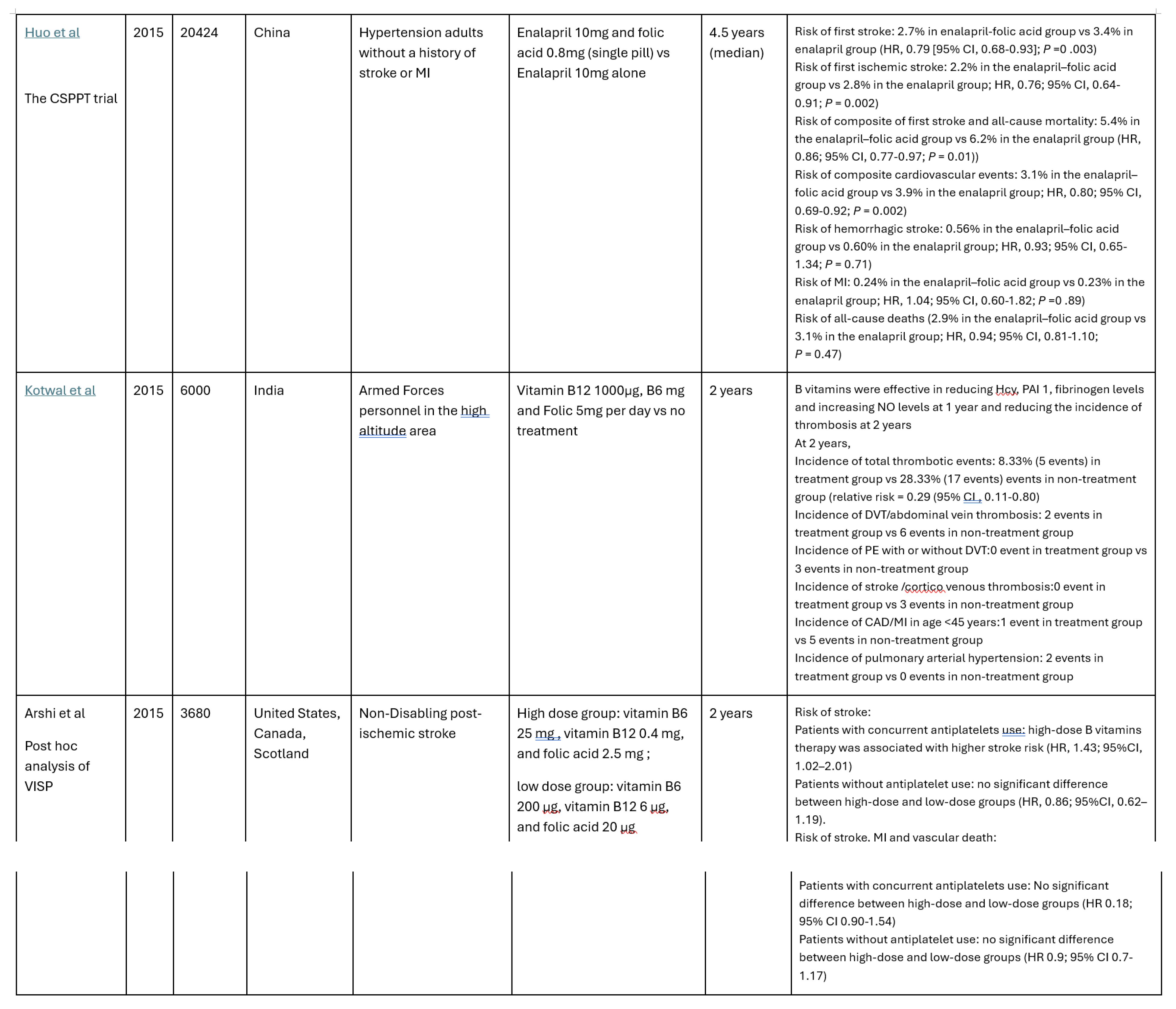

3.1. Summary of Trials on Arterial Thrombosis Events

Among the 24 studies identified, 7 randomized controlled trials (RCT) met the inclusion criteria. Six of these 7 studies were based on the China Stroke Primary Prevention Trial (CSPPT) with different analysis of the effects of enalapril with or without folic acid supplementation in hypertension adults without a history of arterial thrombotic events [

13]. In the CSPPT, folic acid supplementation has been shown to significantly reduce first stroke, first ischemic stroke, and composite cardiovascular events. Particularly, the risk of first stroke was significantly reduced by 73% with a subgroup with low platelets (<210 × 109/l) and high total homocysteine (tHcy) (≥15 μmol/) [

14]. The effect of folic acid intervention also significantly reduced the stroke risk in patients with CC/CT MTHFR genotype [

15] and in male patients with elevated serum calcium levels with increased risk of first stroke [

16].

In addition, Kotwal et al from India reported that B vitamins reduce total thrombosis, stroke and MI in soldiers in high-altitude areas [

17].

However, in the post-ischemic stroke population on antiplatelet therapy, post hoc analysis of VISP trial showed higher stroke risk for patients supplemented with high-dose B vitamins therapy (vitamin B6 25 mg, vitamin B12 0.4 mg, and folic acid 2.5 mg) compared with those on low-dose therapy (vitamin B6 200 μg, vitamin B12 6 μg, and folic acid 20 μg). The increased risk was not found among those not on antiplatelets [

18].

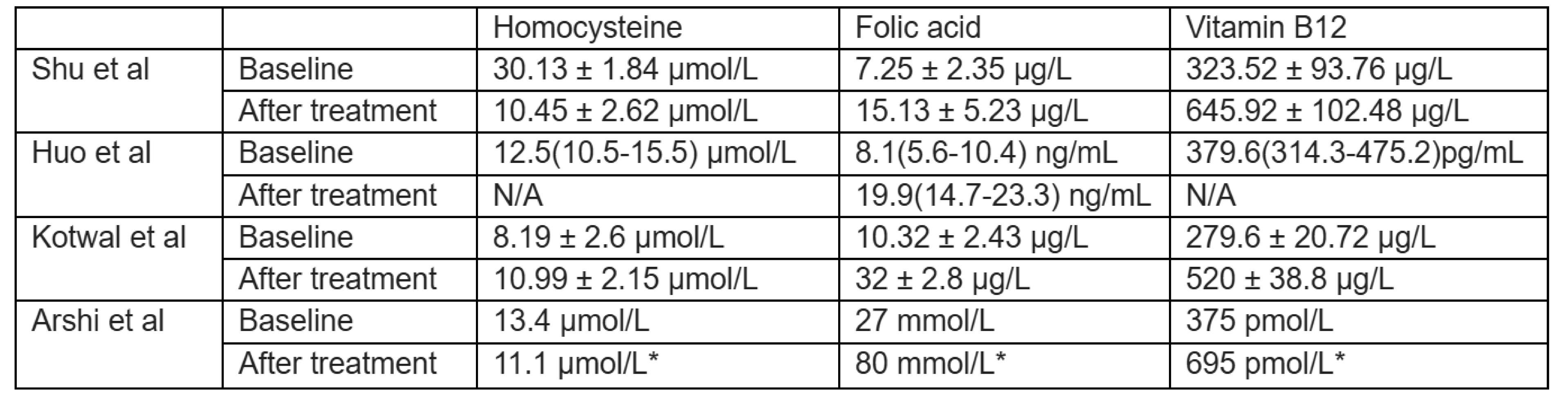

3.2. Summary of Trials on Venous Thrombotic Events

Shu et al studied the effect of folic acid on venous thromboembolic events in patients with cerebral infarction with DVT and baseline homocysteine level around 30 µmol/L for the intervention of folic acid 5mg and vitamin B12 0.25mg daily. Patients' serum folic acid and vitamin B12 levels increased with vitamin B supplementation. Homocysteine level decreased with vitamin B supplements and was negatively correlated with folic acid and vitamin B12 levels. The recurrence rate of lower limb deep venous thrombosis of the treatment group was 4.4%, which was significantly lower than that of the non-treatment group at 28.9% (p<0.05) [

19]. Kotwal et.al also showed a numerically lower number of incidences of DVT and PE in soldiers staying in high altitude supplemented with folic acid, vitamin B6 and vitamin B12 [

17].

Various vitamin B supplementation strategies have been used. It ranges from folic acid with antihypertensive medication to a combination of folic acid, vitamin B12, and vitamin B6.

See

Table 1 for study detailed summaries including study design, B vitamins regimen, and clinical outcomes.

Table 1.

Summary of RCTs of Vitamin B Supplements to the Risk of Thrombotic Events During 2014 to 2024.

Table 1.

Summary of RCTs of Vitamin B Supplements to the Risk of Thrombotic Events During 2014 to 2024.

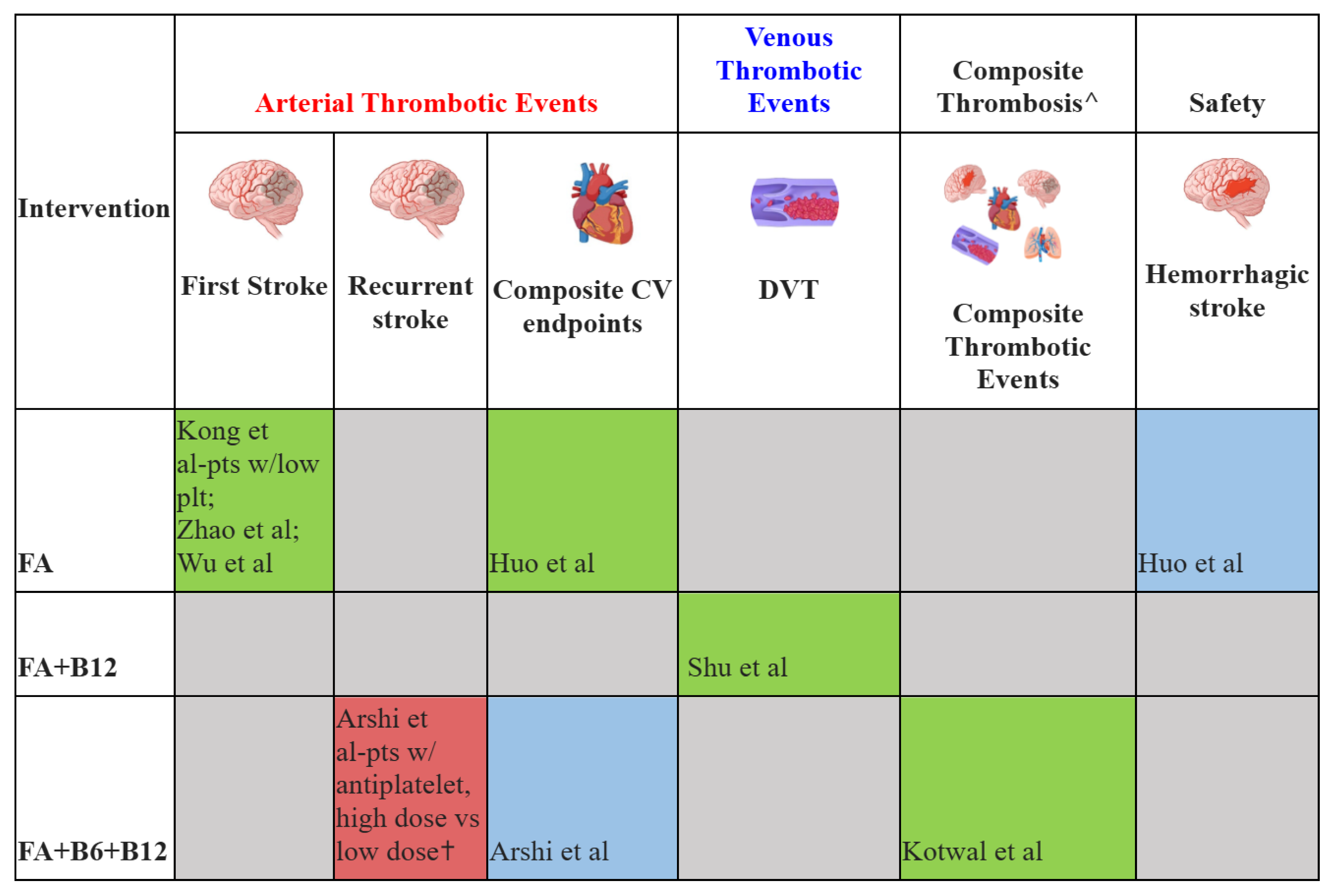

Table 2.

Summary of the Thrombotic Outcomes of Table 1*.

Table 2.

Summary of the Thrombotic Outcomes of Table 1*.

Table 3.

Change of Serum Homocysteine, Folic Acid and Vitamin B12 Levels.

Table 3.

Change of Serum Homocysteine, Folic Acid and Vitamin B12 Levels.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Vitamin B Supplements on Arterial Events

The possible role of folic acid in reducing the risk of stroke through lowering homocysteine levels has been investigated. One of the studies from CSPPT [

13] has demonstrated that compared to the sole use of antihypertensive medication, the combination of blood pressure drug and folic acid could reduce the risk of stroke by 21%. In a following study [

14], the risk factor of primary stroke prevention through folic acid has been identified. As a comparison, the previous clinical studies VISP trial [

20] and VITATOPS [

21] showed no statistically significant results in reducing the primary outcome of recurrent stroke with high-dose folic acid, vitamin B6 and B12 (2.5mg, 25 mg, and 0.4 mg) group compared to low-dose (20 μg, 200 μg, and 6 μg) group. They also showed no differences in reducing the composite outcomes of recurrent stroke or TIA when comparing folic acid with placebo, respectively [

20,

21].

Sub analysis of previous studies pointed to a reverse association between B vitamins supplementation and antiplatelet use and in reducing the risk of stroke. One of the post-hoc analyses of the VISP trial showed that high-dose folic acid with vitamin B6 and B12, compared to low-dose, may increase the risk of recurrent stroke in patients with the concurrent use of antiplatelets (hazard ratio (HR), 1.43; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.02–2.01) [

18]. However, among patients who were not on antiplatelets, a trend of decreased risk was identified with the high dose of folic acid. Similar trends were reported in one of the post-hoc analyses of VITATOPS trial that unlike patients who were not the recipients of any antiplatelets, patients with the baseline use of antiplatelets did not benefit from the treatment of B vitamins regarding the primary or secondary outcomes of stroke, MI, or cardiovascular death [

22]. The aforesaid evidence indicates the baseline use of antiplatelets may be used as a predictor of the efficacy of B vitamins and antiplatelet-naive patients may be a targeted population of B vitamins treatment in the prevention of stroke and other cardiovascular thrombotic events. As the current results are from post-hoc analysis, more prospective studies are warranted to investigate the correlation between antiplatelets, B vitamins, and the risk of stroke.

4.2. Effects of Vitamin B Supplements on Venous Thrombotic Events

Studies on risk reduction of VTE through homocysteine lowering by daily supplementation of B vitamins were conflicting. While Shu et al. [

19] found positive effects of B vitamins in reduced lower limb DVT recurrence rate, VITRO study found that homocysteine lowering by B vitamins did not prevent any recurrent VTE [

23]. In the VITRO study, adult patients with a first confirmed deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE) with a homocysteine level above the 75th percentile of the normal value were randomized to daily supplementation of 5mg folic acid, 50mg pyridoxine, and 0.4mg cyanocobalamin) or placebo. Patients were followed for 2.5 years. The number of recurrent VTE was 12.2% in the B vitamin group vs. 14.4% in the placebo group [

23].

Since 2014, there’s only one study that specifically investigated combination B supplements reducing the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) through serum homocysteine lowering. However, previous meta-analysis also has shown that reduced levels of folic acid and vitamin B12 could be an independent risk factor for venous thrombosis regardless of homocysteine level [

24]. Cattaneo et al also found the correlation between low vitamin B6 levels and the risk of DVT is independent of fasting tHcy levels [

25]. Another study found there was a significantly reduced vitamin B6 level among patients with unprovoked VTE compared to healthy volunteers (p<0.009) [

26]. There were no significant differences in terms of tHcy level, folic acid level, and vitamin B12 level. These findings suggest that B vitamins may play a protective role in the prevention of venous thrombosis independent of the homocysteine pathway. Further randomized controlled studies are needed to support these benefits.

4.3. Effects of Vitamin B Supplements on Other Vascular Outcomes

Other than DVT/PE, ischemic stroke, and MI, B vitamins also have effects on vascular endothelial function. For example, Chambers et al demonstrated oral folic acid and vitamin B12 supplementations improved vascular endothelial function in patients with coronary heart disease. The mechanism is thought to be via reducing homocysteine levels in the body [

27]. Similarly, Menzel et al also demonstrated that B vitamins could reduce the deterioration of endothelial function in addition to reducing blood pressure and tHcy levels [

28]. Zamani et al published a systematic review in 2023 on folic acid's effect on endothelial function [

29]. The meta-analysis suggested that folic acid supplementation may improve endothelial function by increasing flow-mediated dilation (FMD) and FMD% levels.

Low vitamin B6 and folic acid levels along with elevated homocysteine levels are independent risk factors for retinal vein occlusion (RVO) [

30]. Meng et al published a study in 2018 and demonstrated that the prevalence of retinal atherosclerosis (RA) was 77.6% in patients with hypertension and diabetes, and folic acid supplementation was associated with reduced RA in female patients with hyperhomocysteinemia [

31]. Hodis et al showed high dose vitamin B supplementation reduced the progression of early-stage subclinical atherosclerosis (carotid artery intima-media thickness) in well-nourished individuals at low risk of cardiovascular disease with a fasting homocysteine level of >9.1 µmol/L [

32]. Vitamin B supplementation could improve arterial function in vegetarians with subnormal vitamin B12 levels [

33].

4.4. Effects of Vitamin B Supplements and tHcy Lowering

In the CSPPT trial, folic acid supplementation was also shown to decrease tHcy level and the degree of reduction was affected by sex, MTHFR C677T genotypes, baseline folate, tHcy, estimated glomerular filtration rate levels, and smoking status [

34]. Homocysteine-lowering response by genotype was eliminated when plasma folate levels reached ≈15 ng/mL or higher [

35].

4.5. Potential Cofounders on Clinical Trial Outcomes

4.5.1. Dietary Fortification and Nutritional Deficiencies

Mandatory fortification of grains in the US may be one of the reasons that causes the mixed results regarding reducing stroke risk between trials from North America and the rest of the world. Since mandatory fortification, the mean population tHcy level was lowered from 10.1 to 9.4 μmol/L(p<0.001) [

36]. Most of Europe and China do not mandate fortification [wald et al]. The meta-analysis of folic acid and stroke in non-mandatory fortification areas [

37] showed a modest reduction of future strokes with the use of folic acid (RR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.77 to 0.95) [

38], which suggests that the benefits in prevention of thromboembolism may only apply in population with very high baseline homocysteine due to lack of mandatory fortification. In places with high prevalence of vegetarianism, deficiency of Vitamin B12 is also more common.

4.5.2. Concurrent Medication Treatment

Several drugs could decrease the absorption of vitamin B6,9 and 12. For example, antiepileptics and sulfasalazine can reduce the absorption of folic acid. Isoniazid, cycloserine, penicillamine, hydralazine, levodopa, and some anticonvulsants could affect vitamin B6 absorption. Proton pump inhibitors, H2 receptor antagonists, colchicine, and metformin could lead to vitamin B12 malabsorption. Medications can also cause hyperhomocysteinemia, for example, metformin, methotrexate, niacin, and cholestyramine [

39].

4.5.3. Genetic Mutations

MTHFR gene mutation is associated with reduced enzymatic efficiency and increased homocysteine levels. One of the common genetic variants MTHFR 677C→T has been identified as one of the causes of hyperhomocysteinemia [

40]. As the genotype C677T (heterozygous) was associated with mildly increased homocysteine level, homozygous T677T polymorphism elevated homocysteine level by 25% compared to the CC genotype (non-carriers) [

41]. Homozygous TT genotype has been more frequently found in the Chinese populations than in other populations. This genotype is associated with a 13% increase in the risk of any type of stroke (adjusted odd ratio 1.13, 95% CI 1.09–1.17) when compared to noncarriers [

42]. This genetic distribution perhaps leads to a higher risk of hyperhomocysteinemia and a more significant efficacy of folic acid supplementation among Chinese in the prevention of stroke. One of the CSPPT trial post-hoc analysis focused on the MTHFR mutation subgroup and identified folic acid benefited most in patients with TT genotype and low platelet count with a risk reduction of 66% (HR 95%CI, 0.15-0.81, Number Needed to Treat = 27) [

43].

4.5.4. Safety of Vitamin B Supplement

Though B vitamins are water-soluble vitamins with a wide therapeutic index, over-supplementing B vitamins could also lead to negative clinical outcomes. For example, over supplementation of vitamin B6 could lead to peripheral neuropathy and the recommended upper limit is 100mg/day. Interestingly, in 2020, Flores-Guerrero et al performed a prospective population-based cohort study that demonstrated higher levels of plasma concentrations of vitamin B12 was associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality after adjusting for age, sex, renal function, and other clinical and laboratory variables. Caution should be taken when considering vitamin B12 supplementation in the absence of vitamin B12 deficiency [

44]. The DIVINe trial (Diabetic Intervention with Vitamins to Improve Nephropathy) also concluded that the cyanocobalamin may be harmful for participants with impaired renal function [

45]. Hence, the potential harmful effect with over-supplementation in the general population and supplementation in the renal impairment group can mitigate the potential beneficial effects.

4.6. Limitations and Further Research

Our review is limited by narrative nature that no quantitative analysis was performed due to heterogeneity of trial designs. Our literature search included RCTs in the last 10 years (2014 to 2024). We did not include RCTs prior to 2014 as the management of patients with MI, stroke, PE and DVT have been vastly improved considering recent medical advancements. Hence, comparing outcome measures are no longer comparable and relevant when looking at data from older days. The fact that there are only 7 published RCTs in the time span of 10 years with clinical outcomes further solidified that new trials are much needed in regard to the effect of vitamin B supplements in reducing thrombotic events.

Well-designed clinical trials are needed with the considerations of patients' baseline social and demographic information, such as baseline vitamin B and homocysteine level, smoking and alcohol use, and current medication use. Underlying conditions such as hypercholesterolemia and obesity, genetic mutations also need to be considered for a more homogenous cohort that may yield definitive results.

5. Conclusions

This review investigated the effect of B vitamin supplementation on thrombotic risks by analyzing clinical trials from the last ten years. Limited studies were found with conflicting results in thrombotic risk reduction with supplement of B vitamins. Thus, more clinical trials are needed to determine a clearer correlation between B vitamin supplementation and the risk of thrombosis.

References

- Hanna M, Jaqua E, Nguyen V, Clay J. B Vitamins: Functions and Uses in Medicine. Perm J. 2022 Jun 29;26(2):89-97. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Koklesova L, Mazurakova A, Samec M, Biringer K, Samuel SM, Büsselberg D, Kubatka P, Golubnitschaja O. Homocysteine metabolism as the target for predictive medical approach, disease prevention, prognosis, and treatments tailored to the person. EPMA J. 2021 Nov 11;12(4):477-505. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Menezo Y, Elder K, Clement A, Clement P. Folic Acid, Folinic Acid, 5 Methyl TetraHydroFolate Supplementation for Mutations That Affect Epigenesis through the Folate and One-Carbon Cycles. Biomolecules. 2022 Jan 24;12(2):197. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kataria N, Yadav P, Kumar R, Kumar N, Singh M, Kant R, Kalyani V. Effect of Vitamin B6, B9, and B12 Supplementation on Homocysteine Level and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Stroke Patients: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Cureus. 2021 May 11;13(5):e14958. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Collaboration HLT. Lowering blood homocysteine with folic acid based supplements: meta-analysis of randomised trials. Homocysteine Lowering Trialists' Collaboration. BMJ. 1998 Mar 21;316(7135):894-8. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Eichinger, S. Eichinger S. Homocysteine, vitamin B6 and the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb. 2003 Sep-2004 Dec;33(5-6):342-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray JG, Kearon C, Yi Q, Sheridan P, Lonn E; Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation 2 (HOPE-2) Investigators. Homocysteine-lowering therapy and risk for venous thromboembolism: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Jun 5;146(11):761-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makris M. Hyperhomocysteinemia and thrombosis. Clin Lab Haematol. 2000 Jun;22(3):133-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guéant JL, Guéant-Rodriguez RM, Oussalah A, Zuily S, Rosenberg I. Hyperhomocysteinemia in Cardiovascular Diseases: Revisiting Observational Studies and Clinical Trials. Thromb Haemost. 2023 Mar;123(3):270-282. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guieu R, Ruf J, Mottola G. Hyperhomocysteinemia and cardiovascular diseases. Ann Biol Clin (Paris). 2022 Feb 1;80(1):7-14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pushpakumar S, Kundu S, Sen U. Endothelial dysfunction: the link between homocysteine and hydrogen sulfide. Curr Med Chem. 2014;21(32):3662-72. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021 Mar 29;372:n71. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huo Y, Li J, Qin X, Huang Y, Wang X, Gottesman RF, Tang G, Wang B, Chen D, He M, Fu J, Cai Y, Shi X, Zhang Y, Cui Y, Sun N, Li X, Cheng X, Wang J, Yang X, Yang T, Xiao C, Zhao G, Dong Q, Zhu D, Wang X, Ge J, Zhao L, Hu D, Liu L, Hou FF; CSPPT Investigators. Efficacy of folic acid therapy in primary prevention of stroke among adults with hypertension in China: the CSPPT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015 Apr 7;313(13):1325-35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong X, Huang X, Zhao M, et al. Platelet Count Affects Efficacy of Folic Acid in Preventing First Stroke. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2136-2146. [CrossRef]

- Zhao M, Wang X, He M, Qin X, Tang G, Huo Y, Li J, Fu J, Huang X, Cheng X, Wang B, Hou FF, Sun N, Cai Y. Homocysteine and Stroke Risk: Modifying Effect of Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase C677T Polymorphism and Folic Acid Intervention. Stroke. 2017 May;48(5):1183-1190. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu H, Zhang Y, Li H, Li J, Zhang Y, Liang M, Nie J, Wang B, Wang X, Huo Y, Hou FF, Xu X, Qin X. Interaction of serum calcium and folic acid treatment on first stroke in hypertensive males. Clin Nutr. 2021 Apr;40(4):2381-2388. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotwal J, Kotwal A, Bhalla S, Singh PK, Nair V. Effectiveness of homocysteine lowering vitamins in prevention of thrombotic tendency at high altitude area: A randomized field trial. Thromb Res. 2015 Oct;136(4):758-62. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arshi B, Ovbiagele B, Markovic D, Saposnik G, Towfighi A. Differential effect of B-vitamin therapy by antiplatelet use on risk of recurrent vascular events after stroke. Stroke. 2015 Mar;46(3):870-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu XJ, Li ZF, Chang YW, Liu SY, Wang WH. Effects of folic acid combined with vitamin B12 on DVT in patients with homocysteine cerebral infarction. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017 May;21(10):2538-2544. [PubMed]

- Spence JD, Howard VJ, Chambless LE, Malinow MR, Pettigrew LC, Stampfer M, Toole JF. Vitamin Intervention for Stroke Prevention (VISP) trial: rationale and design. Neuroepidemiology. 2001 Feb;20(1):16-25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VITATOPS Trial Study Group. B vitamins in patients with recent transient ischaemic attack or stroke in the VITAmins TO Prevent Stroke (VITATOPS) trial: a randomised, double-blind, parallel, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010 Sep;9(9):855-65. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hankey GJ, Eikelboom JW, Yi Q, Lees KR, Chen C, Xavier D, Navarro JC, Ranawaka UK, Uddin W, Ricci S, Gommans J, Schmidt R; VITATOPS trial study group. Antiplatelet therapy and the effects of B vitamins in patients with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack: a post-hoc subanalysis of VITATOPS, a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2012 Jun;11(6):512-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- den Heijer M, Willems HP, Blom HJ, Gerrits WB, Cattaneo M, Eichinger S, Rosendaal FR, Bos GM. Homocysteine lowering by B vitamins and the secondary prevention of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Blood. 2007 Jan 1;109(1):139-44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou K, Zhao R, Geng Z, Jiang L, Cao Y, Xu D, Liu Y, Huang L, Zhou J. Association between B-group vitamins and venous thrombosis: systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2012 Nov;34(4):459-67. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattaneo M, Lombardi R, Lecchi A, Bucciarelli P, Mannucci PM. Low plasma levels of vitamin B(6) are independently associated with a heightened risk of deep-vein thrombosis. Circulation. 2001 Nov 13;104(20):2442-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekim M, Sekeroglu MR, Balahoroglu R, Ozkol H, Ekim H. Roles of the Oxidative Stress and ADMA in the Development of Deep Venous Thrombosis. Biochem Res Int. 2014;2014:703128. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chambers JC, Obeid OA, Refsum H, Ueland P, Hackett D, Hooper J, Turner RM, Thompson SG, Kooner JS. Plasma homocysteine concentrations and risk of coronary heart disease in UK Indian Asian and European men. Lancet. 2000 Feb 12;355(9203):523-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzel D, Haller H, Wilhelm M, Robenek H. L-Arginine and B vitamins improve endothelial function in subjects with mild to moderate blood pressure elevation. Eur J Nutr. 2018 Mar;57(2):557-568. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zamani M, Rezaiian F, Saadati S, Naseri K, Ashtary-Larky D, Yousefi M, Golalipour E, Clark CCT, Rastgoo S, Asbaghi O. The effects of folic acid supplementation on endothelial function in adults: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr J. 2023 Feb 24;22(1):12. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sodi A, Giambene B, Marcucci R, Sofi F, Bolli P, Abbate R, Prisco D, Menchini U. Atherosclerotic and thrombophilic risk factors in patients with recurrent central retinal vein occlusion. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2008 Mar-Apr;18(2):233-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng Y, Li J, Chen X, She H, Zhao L, Peng Y, Zhang J, Shang K, Li H, Yang W, Zhang Y, Gu X, Li J, Qin X, Wang B, Xu X, Hou F, Tang G, Liao R, Yang L, Huo Y. Association Between Folic Acid Supplementation and Retinal Atherosclerosis in Chinese Adults With Hypertension Complicated by Diabetes Mellitus. Front Pharmacol. 2018 Oct 30;9:1159. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Dustin L, Mahrer PR, Azen SP, Detrano R, Selhub J, Alaupovic P, Liu CR, Liu CH, Hwang J, Wilcox AG, Selzer RH; BVAIT Research Group. High-dose B vitamin supplementation and progression of subclinical atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. Stroke. 2009 Mar;40(3):730-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kwok T, Chook P, Qiao M, Tam L, Poon YK, Ahuja AT, Woo J, Celermajer DS, Woo KS. Vitamin B-12 supplementation improves arterial function in vegetarians with subnormal vitamin B-12 status. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16(6):569-73. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang B, Wu H, Li Y, et al. Effect of long-term low-dose folic acid supplementation on degree of total homocysteine-lowering: major effect modifiers. British Journal of Nutrition. 2018;120(10):1122-1130. [CrossRef]

- Huang X, Qin X, Yang W, Liu L, Jiang C, Zhang X, Jiang S, Bao H, Su H, Li P, He M, Song Y, Zhao M, Yin D, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Li J, Yang R, Wu Y, Hong K, Wu Q, Chen Y, Sun N, Li X, Tang G, Wang B, Cai Y, Hou FF, Huo Y, Wang H, Wang X, Cheng X. MTHFR Gene and Serum Folate Interaction on Serum Homocysteine Lowering: Prospect for Precision Folic Acid Treatment. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018 Mar;38(3):679-685. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacques PF, Selhub J, Bostom AG, Wilson PW, Rosenberg IH. The effect of folic acid fortification on plasma folate and total homocysteine concentrations. N Engl J Med. 1999 May 13;340(19):1449-54. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wald, N.J., Morris, J.K. & Blakemore, C. Public health failure in the prevention of neural tube defects: time to abandon the tolerable upper intake level of folate. Public Health Rev 39, 2. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Hsu CY, Chiu SW, Hong KS, Saver JL, Wu YL, Lee JD, Lee M, Ovbiagele B. Folic Acid in Stroke Prevention in Countries without Mandatory Folic Acid Food Fortification: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Stroke. 2018 Jan;20(1):99-109. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim J, Kim H, Roh H, Kwon Y. Causes of hyperhomocysteinemia and its pathological significance. Arch Pharm Res. 2018 Apr;41(4):372-383. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leclerc D, Sibani S, Rozen R. Molecular Biology of Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase (MTHFR) and Overview of Mutations/Polymorphisms. In: Madame Curie Bioscience Database [Internet]. Austin (TX): Landes Bioscience; 2000-2013. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK6561/.

- Jeppe Frederiksen, Klaus Juul, Peer Grande, Gorm B. Jensen, Torben V. Schroeder, Anne Tybjærg-Hansen, Børge G. Nordestgaard; Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphism (C677T), hyperhomocysteinemia, and risk of ischemic cardiovascular disease and venous thromboembolism: prospective and case-control studies from the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Blood. 2004; 104 (10): 3046–3051. [CrossRef]

- Derrick A Bennett, Sarah Parish, Iona Y Millwood, Yu Guo, Yiping Chen, Iain Turnbull, Ling Yang, Jun Lv, Canqing Yu, George Davey Smith, Yongjun Wang, Yilong Wang, Richard Peto, Rory Collins, Robin G Walters, Liming Li, Zhengming Chen, Robert Clarke, the China Kadoorie Biobank (CKB) Study Collaborative Group , MTHFR and risk of stroke and heart disease in a low-folate population: a prospective study of 156 000 Chinese adults, International Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 52, Issue 6, December 2023, Pages 1862–1869. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y., Zhang, Z., Wang, B. et al. Effect of plateletcrit and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T genotypes on folic acid efficacy in stroke prevention. Sig Transduct Target Ther 9, 110. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Flores-Guerrero JL, Minovic I, Groothof D, Gruppen EG, Riphagen IJ, Kootstra-Ros J, Muller Kobold A, Hak E, Navis G, Gansevoort RT, de Borst MH, Dullaart RPF, Bakker SJL. Association of Plasma Concentration of Vitamin B12 With All-Cause Mortality in the General Population in the Netherlands. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Jan 3;3(1):e1919274. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- House AA, Eliasziw M, Cattran DC, et al. Effect of B-Vitamin Therapy on Progression of Diabetic Nephropathy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2010;303(16):1603–1609. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Results showed significant decreased risk;

Results showed significant decreased risk;  Results showed no significant changes;

Results showed no significant changes;  Results showed significant increased risk;

Results showed significant increased risk;  Results not reported. FA: folic acid; B6: vitamin B6; B12, vitamin B12; DVT: deep venous thrombosis; CV: cardiovascular; Composite CV endpoints: myocardial infarction, cardiovascular death, and stroke; Pts: patients; w/: with; plt: platelet.

Results not reported. FA: folic acid; B6: vitamin B6; B12, vitamin B12; DVT: deep venous thrombosis; CV: cardiovascular; Composite CV endpoints: myocardial infarction, cardiovascular death, and stroke; Pts: patients; w/: with; plt: platelet.