2. Results and Discussion

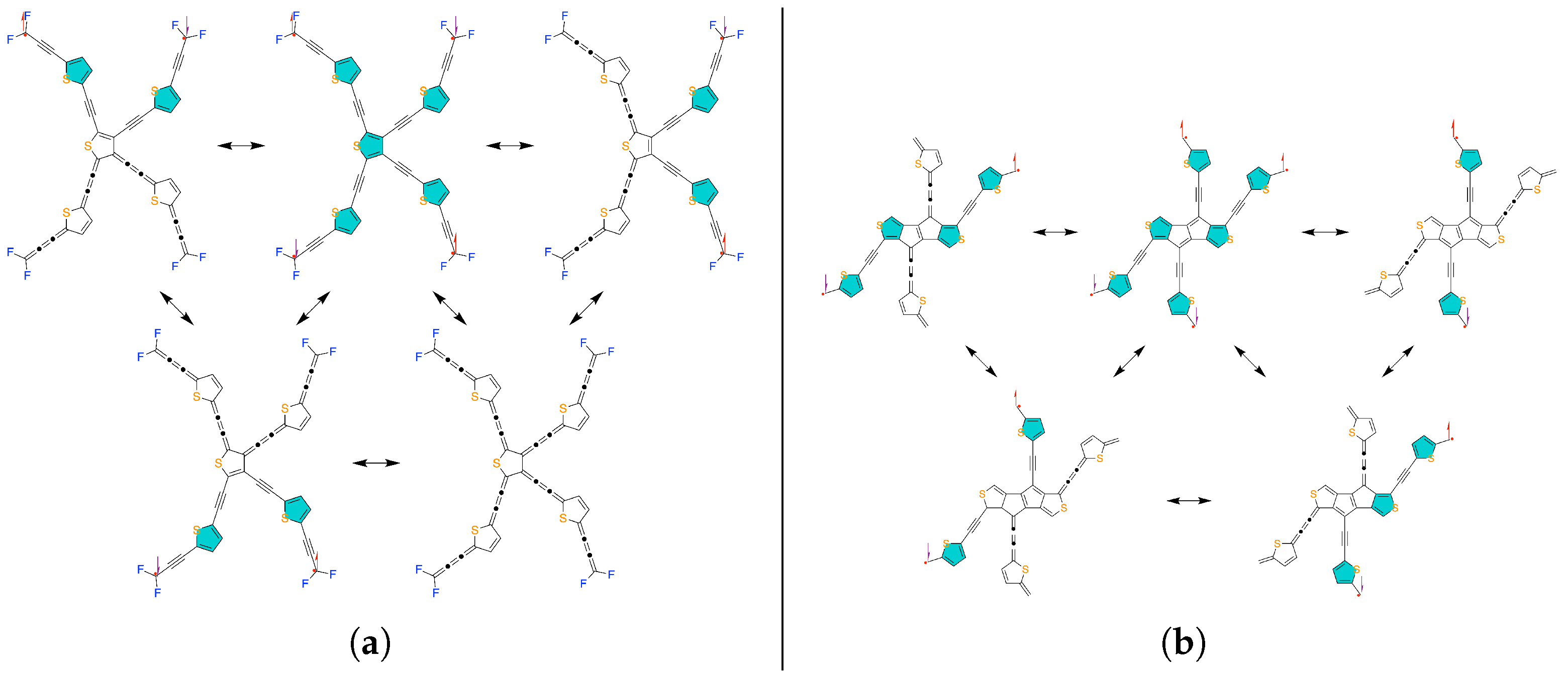

By application of the theory of rational design of polyradicals, we designed parallel- and cross-conjugated tetraradical(oid)s, which contain five-membered cyclopentadienyl and thiophene rings. The aromatic stabilization of thiophene and the topology of the

-systems leads to high open-shell characters in the designed compounds as results show. The resonance structures of parallel-conjugated thiophenic tetraradical(oid)

PT0,4 is given in

Figure 1a and those of cross-conjugated thiophenic tetraradical(oid)

CT2,4 is given in

Figure 1b.

Upon analysis of the valence bond forms of

PT0,4 in

Figure 1a, we can note that there is no lower-bond restriction for this compound to have open shells, in diradical structure compared to closed-shell structure, two more thiophene rings assume aromatic configuration with 6

electrons. In the tetraradical valence bond form, three more thiophene rings assume aromatic configuration compared to diradical VBFs (

Figure 1a). Our theory of polyradical design says that we need the aromatic resonance energy from at least two-three benzene rings to offset the energy of the broken

bond upon opening the shell, and the aromatic resonance energy of benzene is about 151

while the thiophene’s is about 121

[

16]. Thus, about 2.5–3.75 thiophene rings are needed to bridge directly

-conjugated unpaired electrons to maintain the high open shell character. Moreover, as apparent from the resonance structures of

PT0,4 in

Figure 1a, each unpaired electron is directly

-conjugated to two other unpaired electrons, so that in some valence bond forms, each such electron could be paired with any of the other directly

-conjugated electron and close the corresponding shell. In total, if every unpaired electron becomes paired, the aromatic configuration of all five thiophene rings is lost. This co-dependence between aromaticity and open-shell character leads to high diradical and tetraradical characters of the

PT0,4. We computed the electronic structure of

PT0,4 with complete active space self-consistent field (CASSCF) [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24] calculations with Dunning’s correlation consistent double-

basis set [

25], which showed that the low-energy spectrum of

PT0,4 has narrow spectral range of 72 cm

−1, singlet ground state (GS) with a quintet highest-energy spin state (HS), and singlet-triplet gap of 29 cm

−1, as shown in taba2 (see computational details thoroughly in section S2 of the Supporting Information). The natural orbitals (NOs) are eigenvectors of the first-order density matrix and their occupation numbers are corresponding eigenvalues [

26]. Each of these orbitals shows the electron density distribution of the average number of electrons occupying it. Frontier NOs of

PT0,4 with symbolic assignations are given in fig3. These NOs describe the electron density distribution in the spin states of the low-energy spectrum given taba2. As evident from the frontier NO occupation numbers of

PT0,4, even in the singlet ground state, four of

values are very close to 1, which means there are almost four unpaired electrons. Diradical and tetraradical

and

as special cases of polyradical character

vary from

(fully closed shell) to

(fully open shell) and we are calculating them based on frontier NO occupation number according to the method of Yamaguchi [

27]. For

PT0,4, the diradical character

and tetraradical character

, implying almost fully open-shell electronic structure with four unpaired electrons. Even though there is no topological restriction for this compound to have an open-shell electronic structure, the electrons remain unpaired because the collective aromatic resonance energy of thiophene rings offsets the energy that would have been gained by

bonding if these electrons paired.

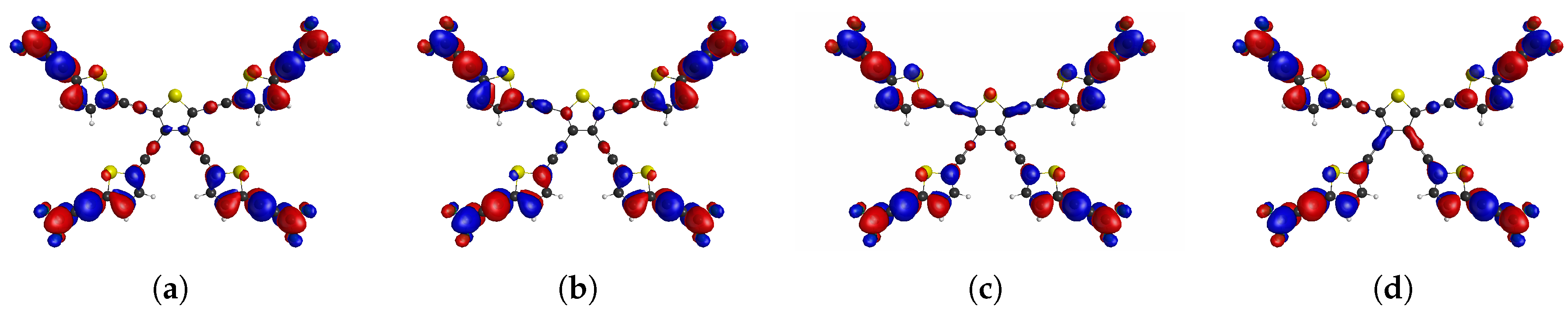

Figure 2.

The frontier CASSCF NOs of tetraradical(oid) PT0,4 describing the density distribution of unpaired electrons indicated by NO occupation numbers: (a), (b), (c), (d),

Figure 2.

The frontier CASSCF NOs of tetraradical(oid) PT0,4 describing the density distribution of unpaired electrons indicated by NO occupation numbers: (a), (b), (c), (d),

Table 1.

CASSCF(12,12)/cc-pVDZ states of PT0,4 using quintet UKS/DFT-optimized geometry.

Table 1.

CASSCF(12,12)/cc-pVDZ states of PT0,4 using quintet UKS/DFT-optimized geometry.

| State |

Symmetry |

HONO – 1 |

HONO |

LUNO |

LUNO + 1 |

from G. S. (cm−1) |

|

A |

|

1.050 |

|

1.043 |

|

0.958 |

|

0.948 |

0.00 |

|

A |

|

1.037 |

|

1.012 |

|

0.989 |

|

0.962 |

29.34 |

|

A |

|

1.024 |

|

1.017 |

|

0.983 |

|

0.975 |

44.18 |

|

A |

|

1.018 |

|

1.010 |

|

0.993 |

|

0.979 |

58.31 |

|

A |

|

1.011 |

|

1.008 |

|

0.991 |

|

0.990 |

64.25 |

|

A |

|

1.000 |

|

1.000 |

|

1.000 |

|

0.999 |

72.21 |

Having characterized the parallel-conjugated tetraradical(oid), let us now focus on the cross-conjugated thiophenic tetraradical(oid)

CT2,4 which includes not only thiophene rings but also fused cyclopentadienyl rings so that it has five-membered rings only based on the carbon atom. It is important to emphasize that we cannot create the true cross-conjugation with only five-membered heterocyclic aromatic rings (furan, pyrrole, thiophene, etc.) as shown in

Figure 1a. This is because paths of direct

-conjugation can diverge in such geometries. However, if we have the five-membered rings with each atom able to form single or double bonds within and outside the ring, we can create such geometries when connected terminal sites can have converging paths of direct

-conjugation, which can be used to create the topological restriction on the lower-bound number of unpaired electrons. This property was employed in designing

CT2,4 for which resonance structures are shown in

Figure 1b. Notably, from these structures it is evident that closing the shell between unpaired electrons on the opposite sides of the pentaleno[1,2-c:4,5-c’]dithiophene subsystem only destroys the aromatic configuration of two thiophene rings, while any other on-bond pairing destroys at least three. Moreover, among diradical VBFs of the

CT2,4, which have equal number of

bonds, one of them has highest amount (four) of thiophene rings with aromatic configuration. Thus, according to Clar’s rule [

28], it should the most important contributor between diradical VBFs should. In contrast, there are no such differences between diradical valence bond forms of

PT0,4. Hence,

CT2,4 might have a preferred open shell subsystem in some of the states, as evident from

and

states described by tabab2. This concept allows us to control the tendency of modulation between open-shell characters (diradical, tetraradical, etc.) and energy gaps between lower-energy states and relatively higher-energy states within the spin spectrum of polyradicals.

Table 2.

CASSCF(12,12)/cc-pVDZ states of CT2,4 using triplet UKS/DFT-optimized geometry.

Table 2.

CASSCF(12,12)/cc-pVDZ states of CT2,4 using triplet UKS/DFT-optimized geometry.

| State |

Symmetry |

HONO – 1 |

HONO |

LUNO |

LUNO + 1 |

from G. S. (cm−1) |

|

|

N |

1.848 |

* |

1.012 |

* |

0.990 |

N |

0.160 |

0.00 |

|

|

N |

1.852 |

* |

1.001 |

* |

1.001 |

N |

0.157 |

18.84 |

|

|

|

1.097 |

|

1.075 |

|

0.934 |

|

0.898 |

5197.44 |

|

|

|

1.017 |

|

1.000 |

|

1.000 |

|

0.985 |

5197.44 |

|

|

|

1.017 |

|

1.000 |

|

1.000 |

|

0.985 |

5197.44 |

|

|

|

1.025 |

|

1.012 |

|

1.011 |

|

0.954 |

5517.36 |

Table 3.

CASSCF(12,12/cc-pVDZ states of CT2,4 using quintet UKS/DFT-optimized geometry.

Table 3.

CASSCF(12,12/cc-pVDZ states of CT2,4 using quintet UKS/DFT-optimized geometry.

| State |

Symmetry |

HONO – 1 |

HONO |

LUNO |

LUNO + 1 |

from G. S. (cm−1) |

|

|

|

1.202 |

|

1.002 |

|

0.999 |

|

0.799 |

0.00 |

|

|

|

1.129 |

|

1.000 |

|

1.000 |

|

0.872 |

254.64 |

|

|

|

1.006 |

|

1.000 |

|

1.000 |

|

0.995 |

671.30 |

|

|

|

1.006 |

|

1.000 |

|

1.000 |

|

0.995 |

671.33 |

|

|

N/A* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.025 |

|

1.012 |

|

1.011 |

|

0.954 |

817.11 |

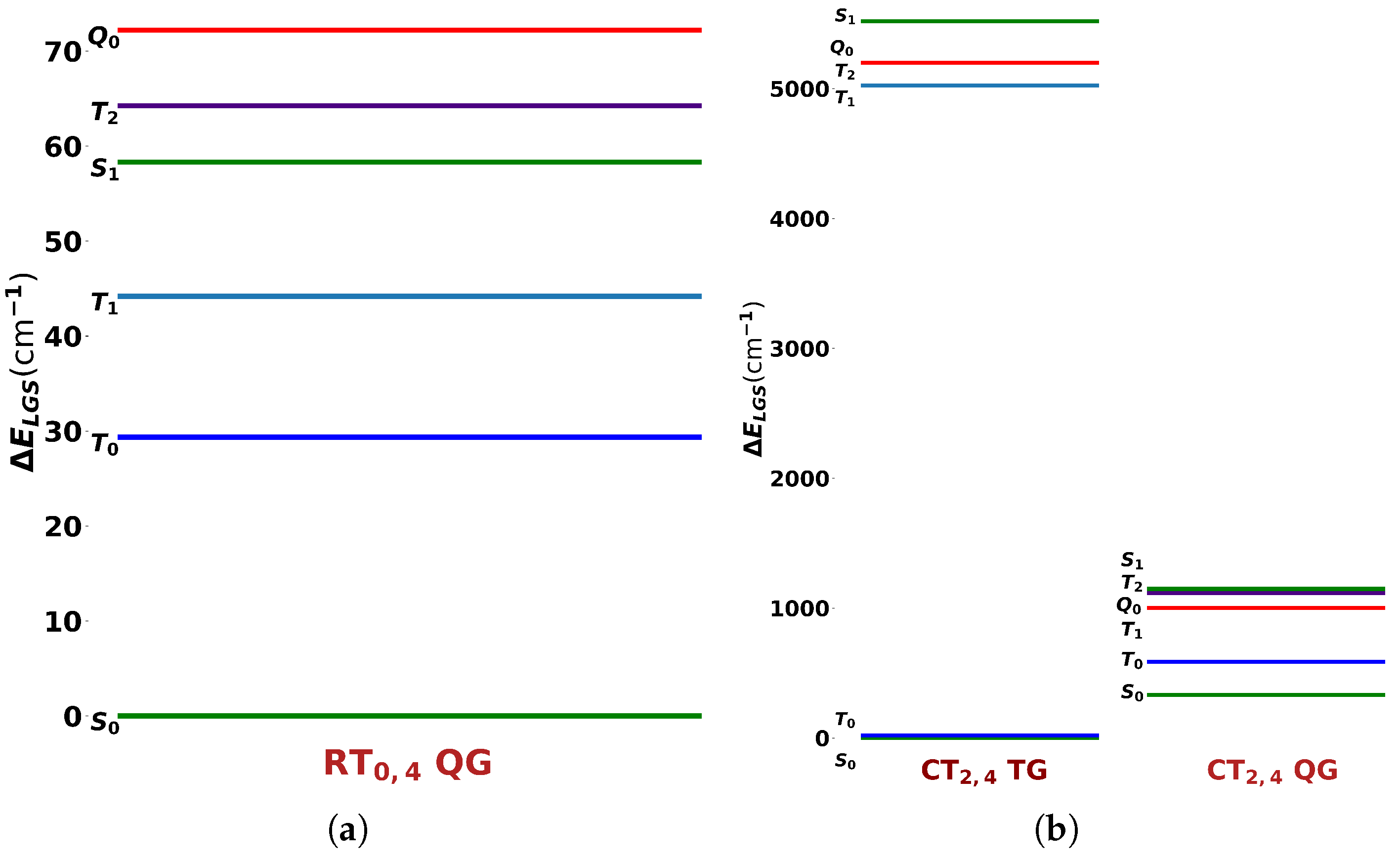

The CASSCF results for different spin states and their characteristics based on frontier NOs and occupation numbers are given in

Table 1 and

Table 2, and CASSCF frontier NOs with symbolic assignations are given in fig4. The spin state spectrum for triplet UKS/DFT and quintet UKS/DFT-optimized geometries (TG and QG, respectively) is given in

Figure 4b. Results show that in the CASSCF(12,12) singlet ground state obtained for triplet UKS/DFT-optimized geometry has two unpaired electrons and the two unpaired electrons are found in the specific parts of the molecule, as shown by the first resonance structure (top left) in

Figure 1b. This is because such a resonance structure has the most amount of thiophene rings in the aromatic configuration among the diradical VBFs and for the triplet UKS/DFT-optimized geometry favors this configuration. However, with sufficiently close energies (almost the degenerate region of PES), when the quintet UKS/DFT-optimized geometry is used for CASSCF(12,12) calculations, the singlet ground state has almost four unpaired electrons according to NO occupation numbers of

state. The diradical character is

and tetraradical character is

(for QG). The comparison of these results shows that since

CT2,4 is topologically restricted to be a diradical, its diradical character is higher than that of

PT0,4, which does not have such restrictions. However, since tetraradical valence bond form of

PT0,4 has three more thiophene rings in aromatic configuration compared to diradical valence bond forms, while tetraradical VBF of

CT2,4 has only two more thiophene rings in aromatic configuration compared to one of the diradical VBFs, the tetraradical character of

PT0,4 is higher. The comparison of the structure of the low-energy spectra of these tetraradical(oid)s is given in fig5. The detailed CASSCF results for these compounds are given in section S3 of the Supporting Information. This is an example how to control the tendency of modulation of open-shell characters for two, four and higher number of unpaired electrons. The topological control of

-conjugation used in conjunction with the control of aromatic stabilization per each pair of directly

-conjugated unpaired electrons allows the precise control over the open-shell properties of the unsaturated organic compounds.

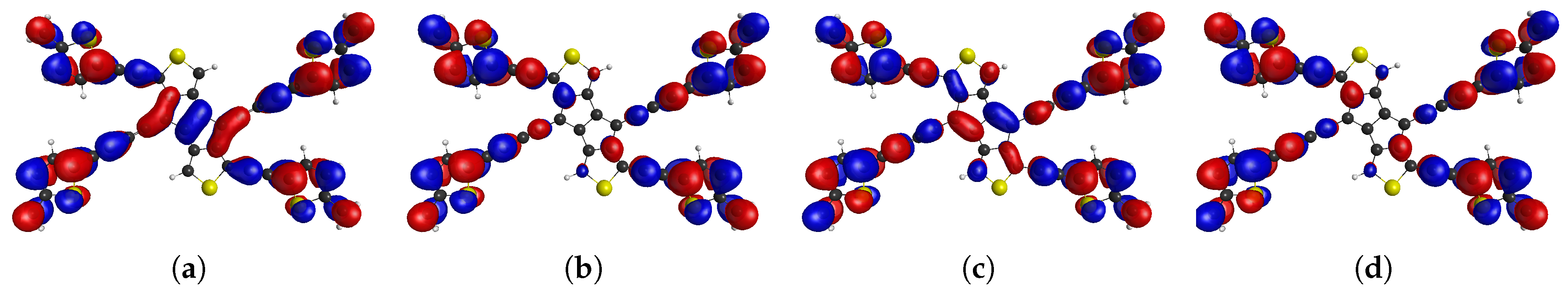

Figure 3.

The frontier CASSCF NOs of tetraradical(oid) CT2,4 describing the density distribution of unpaired electrons indicated by NO occupation numbers: (a), (b), (c), (d),

Figure 3.

The frontier CASSCF NOs of tetraradical(oid) CT2,4 describing the density distribution of unpaired electrons indicated by NO occupation numbers: (a), (b), (c), (d),

Figure 4.

The CASSCF spectra of (a) PT0,4 with quintet-optimized geometry (QG) and (b)CT2,4 with triplet-optimized geometry (TG) and QG.

Figure 4.

The CASSCF spectra of (a) PT0,4 with quintet-optimized geometry (QG) and (b)CT2,4 with triplet-optimized geometry (TG) and QG.

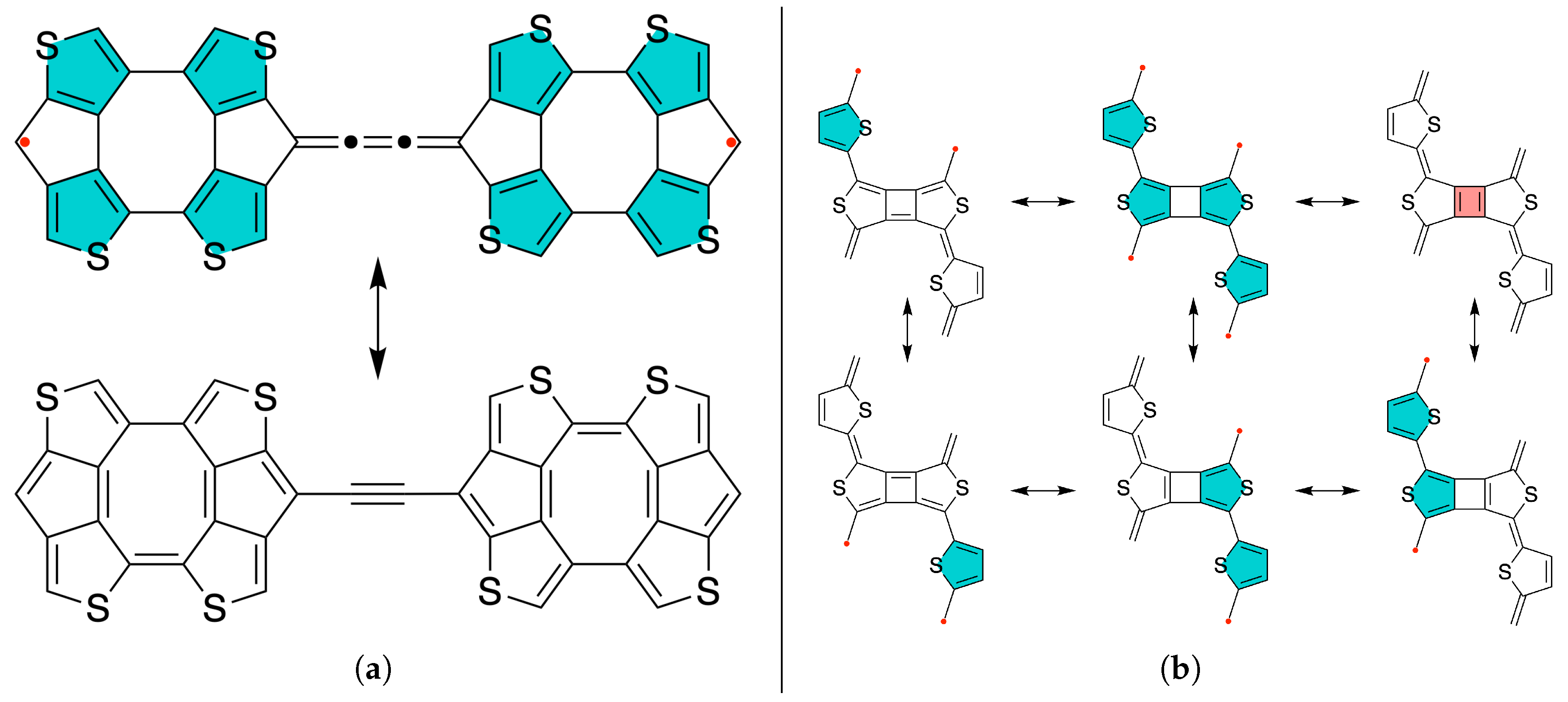

We also designed the diradical system which contains only five-membered rings and no terminal methylene groups as shown in

Figure 5a, in which the cumulative aromaticity of the thiophene rings results in high open-shell character, as verified by CASSCF(14,14)/cc-pVDZ calculations. Specifically, diradical character

, with a singlet-triplet gap of

cm

−1. This system is non-alternant, but due to the symmetry between paths of direct

-conjugation and antiferromagnetic coupling for both paths, it can be predicted that the ground state has a multiplicity of singlet.

In addition to taking advantage of aromaticity and topological restrictions to design compounds with high open-shell characters, we can also take partial or full advantage of anti-aromaticity. In principle, any effect in the compound which stabilizes or destabilizes particular configurations can be used to control some of the properties of compounds. If we are using aromaticity to stabilize open-shell configurations of the compounds, we can use the analogical strategy and use anti-aromaticity to destabilize the closed-shell configurations and in this manner, design compounds with high open-shell character. To exemplify this concept, we designed tetraradical(oid)

, which is expected to have significantly higher diradical character than tetraradical character, because two thiophene aromatic rings are not always sufficient to promote very high (

) open-shell character, but the additional effect of anti-aromaticity in closed-shell VBF compared to diradical VBF with two thiophene rings in the aromatic configuration is greater difference than diradical VBF compared to tetraradical VBF with four thiophene rings in aromatic configuration. Hence, the additional difference made by anti-aromaticity of the cyclobutadiene creates higher diradical character than tetraradical character, even though each open shell is stabilized by two thiophene rings in aromatic configuration according to the resonance structures in

Figure 5b. As a consequence, the diradical character of this compound is

and tetraradical character is

according to CASSCF NO occupation numbers of singlet ground state (

) determined by CASSCF(12,12)/cc-pVDZ calculations for triplet and quintet UKS/DFT-optimized geometries. The detailed CASSCF results for

TD0,2 and

are given in section S3 of the Supporting Information.

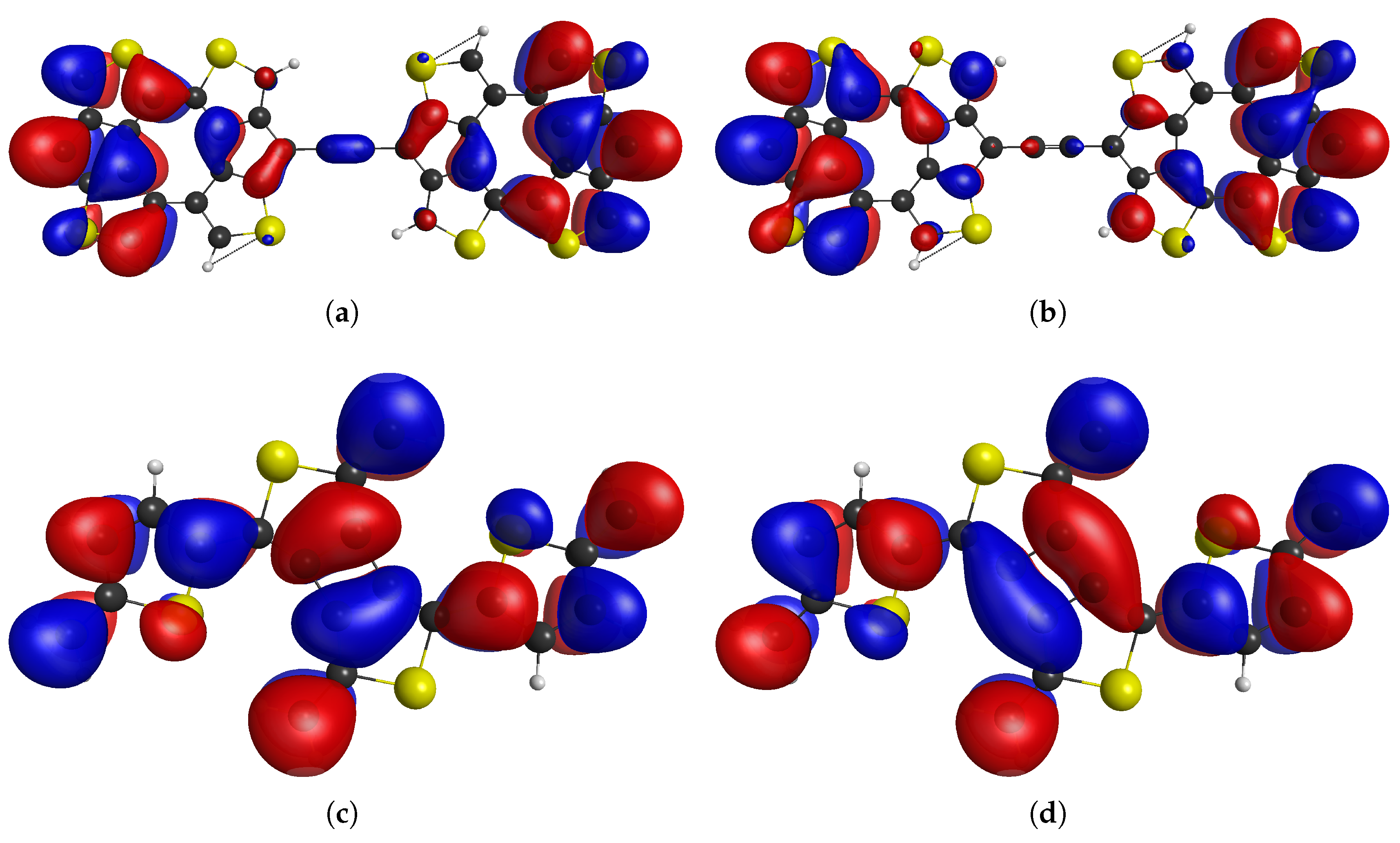

The CASSCF frontier NOs of these compounds are shown in fig6 and they clearly show the presence of unpaired electrons. The higher diradical character of TD0,2 compared to can simply be explained by greater difference in TD0,2 in the number of thiophenic rings in aromatic configuration in diradical VBF compared to closed-shell VBF to offset the energy of the broken bond that leads to the unpaired electrons.

Since we established the rules to control the open-shell characters as well as structure of the spin spectrum of the compounds and now we can create polyradicals with heteroatomic aromatic rings, we can envisage multifunctional molecular materials showing cross-dependent effects between magnetic response (diamagnetism versus ordered magnetism) and external oriented electric field or mechanical stress.

Figure 6.

The CASSCF NOs of TD0,2 ((a) and (b)) and ((c) and (d)).

Figure 6.

The CASSCF NOs of TD0,2 ((a) and (b)) and ((c) and (d)).