1. Introduction

In the highly competitive world of video streaming services, delivering an outstanding user experience (UX) is essential to maintain viewer engagement and satisfaction. Traditional metrics like viewing time and user rating are claimed to be inadequate for measuring user engagement. Viewing time may not depict a reliable active engagement, meanwhile explicit rating is subject to bias and fails to show complex and multifaceted nature of UX and QoE (Quality of Experience). Hence, measuring QoE for optimization based on these metrics much more leads to bias and misinterpretations.

In an era of mass content consumption and the rapid evolution of technology, video streaming services should adapt to a dynamic ecosystem. Some QoE influence factors such as advertisement frequency, network conditions, video content quality will be the main factors that influence QoE. Advertisement not only plays an important role in revenue generation, but, on the other hand, it may degrade QoE if not inserted with a good strategy. Some recent findings to improve QoE utilize adaptive bitrate streaming, congestion prediction model, and sophisticated machine learning algorithm often focus on certain factors and lack of comprehensive and integrated view of QoE.

There is a standard for measuring video QoE recommended by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) named ITU-T P.1203 [

1]. It provides a systematic framework to evaluate audiovisual QoE via adaptive bitrate streaming. Its objective is to build an objective model that mimics subjective QoE for a better accuracy and comprehensive insight.

ITU-T P.1203 is a hybrid model that combines network statistics measurements with perceptual quality models to estimate QoE. It consists of three main modules:

- 1.

Audio Quality Measurement (P.1203.1): This module estimates the quality of audio stream based on codec parameters, sampling rate, and bitrate.

- 2.

Video Quality Measurement (P.1203.2): This module estimates the quality of video based on factors like resolution, encoding bitrate, frame rate, spatial and temporal complexity of content characteristics.

- 3.

Integration Model for Overall Quality (P.1203.3): This module considers both audio and video quality, including stalling events and other streaming disturbances, for overall quality measurement.

To provide a great video streaming experience for the user, it is necessary to measure and optimize QoE accurately. The ITU-T P.1203 standard is a complex model that combines individual quality scores for audio and video streams into an Overall Quality Score (OQS). We formulated OQS as Mean Opinion Score (MOS) ranging from 1 (poor quality) to 5 (excellent quality) to depict the user’s subjective experience.

The ITU-T P.1203 models observe several critical QoE influence factors of the audiovisual quality, including:

- 1.

Bitrate and Resolution Impact: It has been assumed that the better video quality has the higher bitrates and resolutions for their sharp and great image detail. However, at a certain point, higher bitrate and resolution does not mean the user satisfaction keep increasing.

- 2.

Stalling Events: Stalling indicated by video freezing. It is due to loading delays that may result in degradation of user experience. A short period of stalling event may drastically degrade user QoE. Hence, ITU-T P.1203 considers stalling events as one of QoE influence factor.

- 3.

Audio-Video Synchronization: ITU-T P. 1203 consider synchronization of both audio and video to achieve immersive viewing experience. As desynchronization between them may lead to user QoE impairment.

- 4.

Temporal Variation of Quality: ITU-T P.1203 consider both resolution and bitrate fluctuation frequency during video streaming session due to sudden and often fluctuation may lead to deterioration of QoE.

- 5.

Final Quality Integration: ITU-T P.1203 considers individual video stream segments to accumulate quality scores at the segment level over time. Some segments may have different weight due to differences in psychological bias that may impact overall quality.

Final OQS can be formulated as a combination of video and audio scores with its weight as well rebuffering and bitrate fluctuation, as summarized below: [

1]

In equation

1 variable

is the video quality score (e.g., based on bitrate and resolution), variable

is the audio quality score, variable

Stalling Impact reflects the penalty for stalling events, variable

Bitrate Switch Impact accounts for the quality degradation from bitrate changes, variable

,

,

, and

are the weights determined by empirical testing.

In the modern video streaming landscape, it is necessary to compromise between monetization using ad and user QoE. While ITU-T P.1203 does not consider advertisement insertion strategies as one of its influence factors. Our research addresses this gap by taking into account both ad insertion strategies and user satisfaction by proposing a novel approach that is built from ITU-T P.1203 as its base reference.

Our work has six contributions that extend the ITU-T P.1203 scope:

- 1.

Creation and development of AELIX (Adaptive Ensemble for Imbalance Classification using eXplainable AI) to represent advancement in QoE inference by considering face emotion recognition, advertisement strategy, network statistic and user rating.

- 2.

Multi-modal dataset collection and creation of unified platform. The collected data including user face video while watching, user rating and ad feedback.

- 3.

Propose advanced metrics and formulas for QoE optimization. It includes the Ad Effectiveness Score (AES), Log-Transformed Ad Count (LAC), Emotional Valence Consistency (EVC), and Frustration Recovery Rate (FRR).

- 4.

Propose adaptive ensemble learning to handle class imbalance.

- 5.

Propose an ad optimization strategy using sentiment analysis.

- 6.

Found outstanding accuracy over state-of-the-art algorithms. AELIX outperforms the industry standard ITU-T P.1203 by 55.3%, achieving an accuracy of 0.994.

Henceforth, we presented several research questions to help us achieve our research objective:

- 1.

Research Question 1 (RQ1): How can facial expression, sentiment analysis, and network statistic be effectively utilized to estimate user satisfaction during a video streaming session?

- 2.

Research Question 2 (RQ2): How do various ad insertion strategies affect QoE, and how can sentiment analysis offer deeper apprehensions into more holistic QoE?

- 3.

Research Question 3 (RQ3): How can adaptive ensemble learning and XAI effectively tackle an imbalanced data problem to accurately infer QoE compared to traditional metrics.

2. Related Work

In this section, we present the related literature on QoE inference and several QoE influence factors. Quality of Experience in video streaming is a complex, multidimensional challenge that may involve video quality, network conditions, user behavior, and advertisements. We break down the related work into four subsections categorized by topics.

2.1. QoE Prediction and Assessment Techniques

Recently, estimating and optimizing video QoE is one of the prominent research areas. Various approaches have been proposed with different strengths and limitations. In this part, we discuss their contributions and methodologies while comparing with our proposed approach.

M, V. P. K. et al. in [

2] presented a no-reference video quality assessment method using a neuro fuzzy framework. This technique evaluates real-time video by examining video content in no reference condition. Although they did not utilize any facial emotional or advertising as one of their features, they investigate QoE in a real-time environment. On the other hand, our proposed AELIX approach uses not only multimodal data but also takes into consideration network condition, advertisement insertion strategies, and user feedback to provide more holistic insight on evaluating QoE.

Du et al. in [

3] proposed the VCFNet model to evaluate QoE in HTTP adaptive streaming services, focusing on video clarity and fluency. Their proposed model analyzes QoE by emphasizing on video delivery technical aspects while neglecting broader user related element including user emotional engagement and impact of ads. In contrast, our proposed approach extends this idea by adding more elements in user behavior and advertising-related factors to contribute to the assessment of overall QoE.

Selma et al. in [

4] presented the relationships between facial emotions, video advertisements, and QoE, focusing on the role of emotional engagement in the overall evaluation of QoE. Their work aligns with our proposed solution, except that our proposed approach extends further by leveraging ensemble learning, advanced metrics, and XAI to infer QoE.

Ahmad et al. in [

5] explored a holistic study on supervised learning techniques for the estimation of QoE, emphasizing network and video parameters. Although their work has a solid foundation, it still limited on user feedback integration and continuous real-time emotional responses. AELIX fills this gap by integrating these factors into its predictive models to better understand the prediction of Qo.

Skaka-Čekić and Baraković Husić in [

6] presented a QoE modeling methodological feature selection for presenting the most influential factors in QoE. However, implementing this in a real-time manner is still open for challenge. AELIX uses selected features within an adaptive ensemble framework to enhance real-time QoE inference.

Kougioumtzidis et al. in [

7] presented convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to estimate QoE in streaming video games in O-RAN environments. They presented deep learning’s accuracy for certain types of content. AELIX utilizes this idea by implementing deep learning in an ensemble learning framework to handle a wider range of video content.

Ligata et al. in [

8] emphasized on QoE prediction for video services in home WiFi networks environment. They focused more on its network condition. Despite their remarkable network statistic analysis, it did not consider user feedback and emotional responses as proposed by our AELIX.

Bulkan et al. in [

9] presented QoE model for inserting ad by focusing on the importance of ad placement and frequency related to user preferences. Their finding focuses on the impact of ads on QoE, which aligns with our research work.

Jones and Hamby in [

10] evaluated how emotional fluctuation during ad related to ad preferences on overall QoE. Their claim supports our focus on capturing real-time emotional behavior during ad and video consumption with AELIX.

2.2. Network and System-Level QoE Optimization

This subsection presents a comparison of QoE optimization in network and system level with our proposed approach. Firstly, Miranda et al. in [

11] focused on predicting Video on Demand (VoD) QoE based on network Quality of Service (QoS) metrics. They use ICMP probes to observe latency and packet loss in relationship with perceived QoE. Their method relies on technical metrics and overlooking user related metrics like emotional fluctuation. On the other hand, our proposed approach does not only consider network conditions, but also user emotional factor and ad impact in relation to overall QoE.

Orsolic and Skorin-Kapov in [

12] proposed a framework for in-network QoE observation for encrypted video streaming while emphasizing on preserving QoE without compromising encryption on user privacy. Their framework has advantages in an encrypted environment is a must. However, their limitations lie in the limited user feedback and emotional data to deepen their analysis. Our proposed approach fill this gap with considering user feedback and emotional fluctuation both in encryption or no encryption available environment.

Petrou et al. in [

13] explored the open challenges to optimize QoE in YouTube over SATCOM (satellite communication) networks by utilizing deep learning to estimate QoE in high latency environment. Our proposed approach align with their work in utilizing deep learning as well offer more generalizable alternative that are not limited to SATCOM.

Yin et al. in [

14] improve adaptive video streaming by utilizing machine learning method to estimate network fluctuations for responsive video quality adjustments. Their approach improves adaptive streaming performance by implementing real-time network changes. Our proposed approach considers this to apply changing ad insertion strategies in accordance with emotional fluctuations during video consumption.

Zhou et al. in [

15] presented selective prefetching to reduce buffering and improve video quality by using neural enhanced adaptive streaming framework. They use Neural Network (NN) to optimize prefetching strategies and improve streaming quality. Their work focuses mainly on technical aspect without considering the user’s emotional aspect. Our proposed work aligns with their work in utilizing Deep Neural Network while considering user emotional fluctuation in inferring QoE.

Zhang et al. in [

16] presented a real-time QoE inference using advanced machine learning in network communication. They claimed that their proposed solution can dynamically estimate real-time video quality dynamically over various conditions effectively and accurately. AELIX extends their findings by incorporating adaptive ensemble learning with real-time emotional feedback.

Ye et al. in [

17] implemented deep reinforcement learning and digital twins to build adaptive bitrate algorithms that adjust video quality based on fluctuating network conditions. They optimized the streaming quality with better adaptive bitrate selections. AELIX adopts this idea by using ensemble learning and real-time emotion and network fluctuation feedback to account for better overall QoE estimation.

Wang et al. in [

18] proposed AdaEvo. It is a framework to ensure the continuous evolution of deep neural network (DNN) models on mobile devices in a real-time manner. They update the model dynamically according to resource constrained environment in mobile streaming. AELIX adopts this continuous improvement to its QoE prediction model to dynamically shape ad insertion strategies.

Sedlak et al. in [

19] proposed an active inference framework to improve resource allocation in the computing continuum to maintain high QoE in a changing environment conditions.They ensure optimal QoE can be achieved by effectively managing computational resources. AELIX aligns with their focus in adapting the strategies to handle ever-changing emotion and network conditions.

2.3. User Behavior, Interaction, and Immersive Media QoE

In this subsection, we present a comparative analysis of key findings on user behavior and immersive media QoE, contrasting them with our proposed approach. In this case, Laiche et al. in [

20] presented QoE-aware traffic monitoring by evaluating user behavior while watching. They have shown the importance of user interactions and traffic patterns in network management. They focus primarily on the technical aspect of the traffic and user behavior without considering user satisfaction. AELIX builds on this by leveraging facial emotion and advertisement impact analysis with network technical details to provide a more holistic understanding of QoE.

Bartolec et al. in [

21] focused on the impact of user playback interactions related to in-network QoE estimation. They claimed that certain user interactions like play, pause, and seek have specific impact on overall QoE. They mentioned the relationship between user interactions and perceived video quality. However, it still needs real-time emotional feedback for more improvement, as further filled by our proposed work.

Gao et al. in [

2] claimed that they can optimize QoE in adaptive bitrate streaming environment by predicting user interest. They dynamically adjust video bitrate based on predicted user interest. They presented its effectiveness in improving technical streaming quality. Our work aligns with their work in ensuring both technical network conditions and user engagement to improve QoE.

Van Kasteren et al. [

23] and Nguyen et al. [

24] provide a novel point of view of QoE in immersive media. Van Kasteren et al. used subjective and eye movement to investigate user interaction with video content. Moreover, Nguyen et al. discover the limitations of traditional video quality metrics to capture QoE in AR (Augmented Reality) environment. These works highlight the need for a better framework and metric to adjust to the rapidly evolving understanding of QoE.AELIX builds on these to present some advanced metric that will hopefully be an alternative to understand QoE in a better way.

2.4. Advanced Techniques and Explainability in Video Streaming

In this subsection, we presentexisting approaches in video streaming explainability. Zhang et al. [

25] utilized causal structure learning to estimate cellular QoE using technical insight without considering any user-related factors. Meanwhile, our proposed approach integrates causal factors with real-time emotional features that contribute to overall QoE. Wu et al. [

26] and Lundberg and Lee [

27] presented explainability in deep learning through SHAP. It is aligned with AELIX to ensure interpretable and transparent QoE estimations.

Moreover, Zhang et al. [

28] and Shepelenko et al. [

29] explored the emotional effect of emotions on user behavior. Their works aligned with ours in terms of real-time integration of emotion recognition into the approach. Zhou et al. [

30] claimed the physiological data efficacy such as eye-tracking for user state prediction. AELIX use this fact to integrate facial emotion into the approach to dynamically enhance experiences. García-Torres et al. [

31] focused on adaptive and interpretable models as used in our approach through ensemble learning and explainable AI. The summary of this comparative literature review and discussion is shown in

Table 1.

3. Methodology

This section explains the step-by-step method to achieve the research objective and answer the research questions. The research questions presented in

Table A1 in

Appendix A.1. Our proposed approach is illustrated in

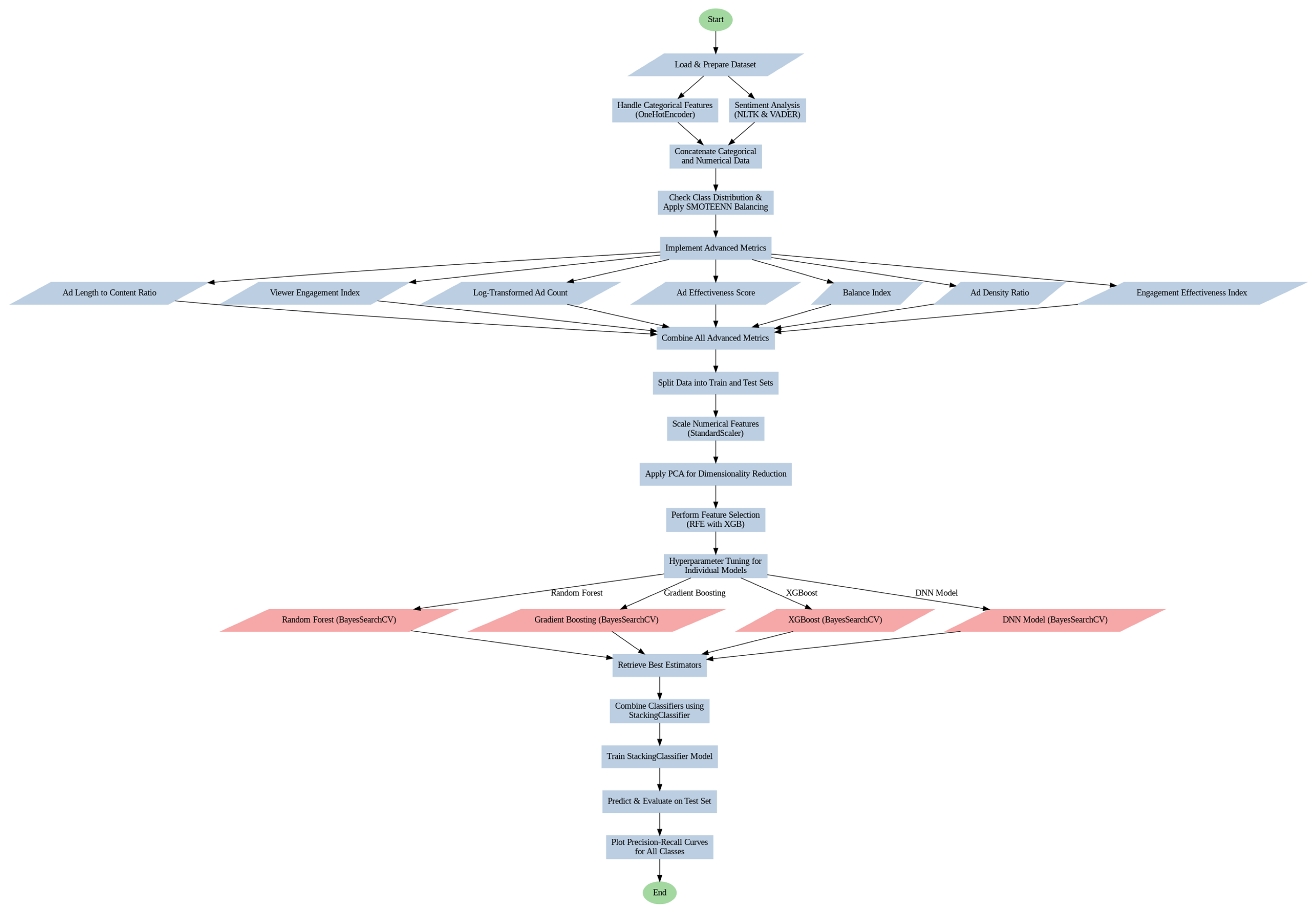

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

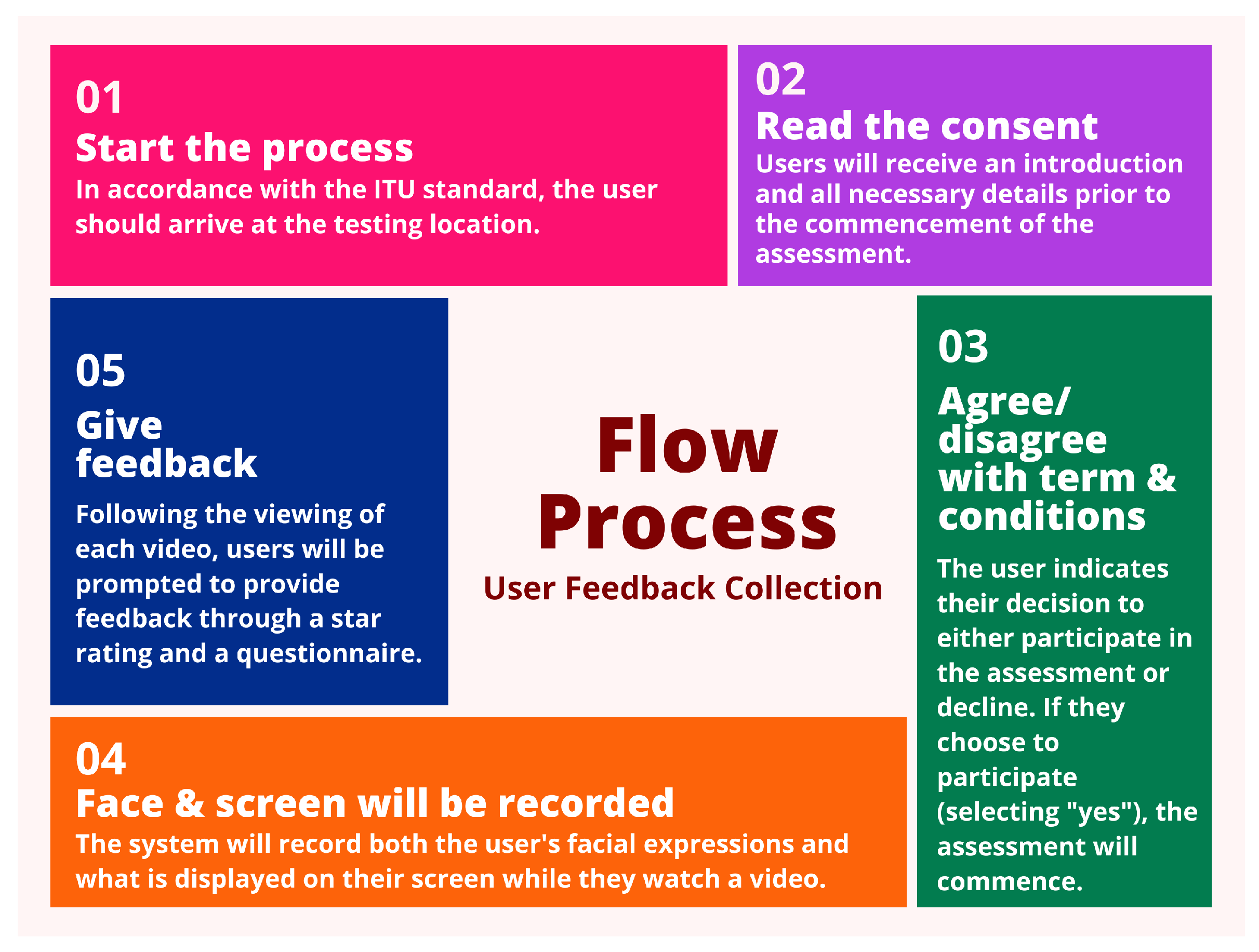

Figure 1 summarizes the user experience during the test.

Figure 2 summarizes the back-end process of our proposed approach. Next, we overview

Figure 1.

Step 1: User Arrive at test location/visit test website At the initial stage, as shown in

Figure 1, user enters the lab room and reads the agreement. There are some conditions that we cannot reach the participants across the globe, so that we advertise the questionnaire and survey to be taken by any participants who want to earn some amount of money (around 0.5 USD). All the platforms are centralized into one

www.tisaselma.online/form.html for Indonesian people who is talking in Bahasa Indonesia or

www.tisaselma.online/form2.html for user talking in English language. In addition, the automatic recording platform

www.xavyr.co.uk developed for the automatic face and screen recording. The questionnaire has 100 questions that can be reached through this link:

https://tinyurl.com/QoEQuestion.

Step 2: Consent Process Participants were asked to read the procedures and consent form. If they accept, they can proceed, if not, they can leave at any time and for any reason.

Step 3: Acceptance of Terms and Conditions Upon agreement to the consent, some participants give their consent to be recorded by their face and screen.

Step 4: Video Viewing and Recording Participants are then allowed to watch a 5 minute video with ads and give their ratings and comments afterward. While they were watching the video, their face and screen was being recorded and saved into the server.

Step 5: Rating and Feedback After the participants watched each video, they were asked to give a rating from 1 to 5 and submit comments about their watching experience. Right after they have finished watching all videos, they were asked to fill in the survey.

In this section, we overview the data collection and preparation processes. First, we collected participant demographics; second, we collected participant consent; third, we collected participant face and screen recording; fourth, we collected network statistic while participants were watching video with ads; fifth, we collected star rating and comments. In the end, we collected the responses to the questionnaire. All demographic information is saved in an Excel file All face recordings will be extracted into frames using VLC. We use 30 fps and a 4-second time window. A frame is extracted every 4 seconds. For every 120 frames, there will be one frame extracted as the input. These frames will be fed into DeepFace to get face emotion. These facial emotions would be mapped to one to five emotions as per

Table 2. This emotion would be put in the Excel file to unify as 1 to 5 ratings used to train the model. Meanwhile, the network statistic while participant watching, extracted from YouTube stats-for-nerds including bitrate, resolution, stalling information. These network statistics would be fed into ITU-T. P.1203 and gave the results as a 1-5 QoS score. The sample of all unified data sources is available in the Appendix

Table A3 in

Appendix A.3.

Next, we present an overview of our proposed methodology as illustrated in

Figure 2. The following is a detailed step-by-step explanation of it.

- 1.

-

Start

- 2.

-

Data Analysis (Node: Load & Prepare Dataset)

Step: Prepare the dataset and perform Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA). We checked the dataset from any missing values, outliers, and data distributions.

Missing Features Handling: We remove missing values and fill them with 0 to avoid problems during training. We address all the outliers through removal. Example: columns such as bitrate, ad.count_x, and content.length_x contain missing values or outliers, which are replaced with 0 or filled with mean/median.

-

We use two public datasets from YouTube Spam Collection by Alberto & Lochter [

38] and Advertising Dataset from Elmetwally, n.d. [

39]. They are used as an accuracy comparison with our collected data and our proposed approach. We use YouTube dataset to help us analyze user feedback and engagement patterns. And we use Advertising Dataset to show interactions and click-through rates pattern that may be beneficial for QoE.

- –

The YouTube Spam Collection dataset by Alberto and Lochter [

38] contains labeled comments from YouTube videos that differentiate between spam and not.

- –

The Advertising Dataset by Elmetwally [

39] on Kaggle contains advertisement data on social media with their metrics such as clicks and demographics.

- 3.

-

Data Augmentation (Node: Handle Categorical Features)

Categorical Feature Encoding: We use it to convert columns using One-Hot Encoding or Feature Hashing. It transforms nominal and ordinal variables into binary for numerical processing. Example: a resolution column has values such as 720p, 1080p, and can be transformed into binary columns’ resolution_720p, resolution_1080p.

Numerical & Categorical Merge: we combine encoded data with numerical columns such as bitrate, content.length_x, and customized metrics such as Ad Length to Content Ratio.

- 4.

-

Sentiment Analysis (Node: sentiment analysis)

In the initial state of text preprocessing, user reviews or comments are prepared using NLTK [

40]. The preparation includes text tokenizing, removing stop words, and standardizing word by stemming.

VADER (Valence Aware Dictionary for Sentiment Reasoning) gives sentiment scores based on a predefined lexicon associated with valence scores. It is derived from human sentiment analysis and statistical research. For example, “hate” was assigned as a strong negative (e.g, -3.0) due to the common emotional intensity in language usage (Hutto & Gilbert, 2014 in [

43]).

The system modifies sentiment scores by contextual modifiers. For example, intensifiers (“really”) can reverse sentiment, and negations (“not”) can reverse it.

-

For instance:

- –

“I hate these ads” has a compound sentiment score of -0.75, and has strong negativity.

- –

“I really hate these ads!” amplifies the negative up to -0.9 due to the intensifier.

- –

“I do not hate these ads” flips the score to +0.1 and modify negative sentiment with negation.

VADER normalizes individual word scores to a compound value between -1 (most negative) and +1 (most positive). VADER is effective in social media sentiment analysis as compared to human raters.

-

Example:

- –

“I hate these ads” yields a compound score of -0.75 (strong negative).

- –

“I really hate these ads!” amplifies the negative sentiment to -0.9 due to the intensifier.

- –

“I do not hate these ads” results in +0.1, reversing the negative sentiment.

- 5.

-

Feature Engineering (Node: Concatenate Categorical and Numerical Data)

Once categorical features are encoded, they must be merged with existing numerical data for subsequent processing.

Example: Columns such as content.length_x (numerical) and resolution_720p (encoded categorical) are combined into a single data frame.

- 6.

-

Class Imbalance Handling (Node: Check Class Distribution & Apply SMOTEENN Balancing)

To handle class imbalance, we use SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique). SMOTE is used to create synthetic samples for minority classes to ensure a balanced training model.

Example: Our collected data set has low-rated ads compared to high-rated ones. SMOTE generates synthetic samples for high-rated ads to balance the training set.

- 7.

-

Implement Advanced Metrics (Node: Implement Advanced Metrics)

Traditional metrics to assess ads effect like click-through rates (CTR), user ratings failed to investigate the relationship between ads and engagement. They overlook aspects like the ratio between ad and content length and user interruption tolerance.

The streaming platforms need to compromise between profit and user satisfaction; it is a necessity to develop more holistic metrics.

Our goal is to validate proposed metrics: Log-Transformed Ad Count (LAC), Ad Effectiveness Score (AES), Emotional Valence Consistency (EVC), and Frustration Recovery Rate (FRR). They have the potential to enhance QoE inference accuracy in our collected dataset.

-

The dataset used for this research from wide range of culture, content and ads. We used two public datasets and several algorithms to ensure generalizability against our proposed approach. The experimental results of using proposed metrics can be seen in

Table 4.

- (a)

-

Ad Effectiveness Score (AES): AES assess ad effectiveness by considering user ratings, burden of ad frequency and ad length. Equation

2 is used to determine AES:

In equation

2 variable stars is the user’s rating. AdCount is the number of ads inserted in video. AdLength is ad length. ContentLength is the length of video content. AES offer a measure to tolerate between maximizing ad revenue and optimizing user satisfaction. From our collected data, users who consume more/longer ads were more likely to rate video poorly, non-linearly.

- (b)

-

Log-Ad Count (LAC) LogAdCount has a function to normalize ad count distribution to make the metric less susceptible due to outliers. Equation

3 is used to determine LAC:

In equation

3 variable AdCount is the number of ads inserted in a video content. Without log transformation, the distribution of ad counts in a dataset is often heavily skewed. Most users seeing a few ads and a few users see a high number of ads unevenly. This skew can ruin the models. It makes a difficult assessment of true ad frequency influence on user behavior. The model becomes more robust to outliers and can generalize better across a wider range of ad counts by applying a log transformation, Accordingly, the predictions become more accurate. Without this adjustment, it would be biased towards users with lower ad exposure, resulting in inaccurate predictions in a real-world scenarios.

- (c)

-

Emotional Valence Consistency (EVC) Emotional Valence means positive or negative emotional experience. Consistency means a stable conditions of a user’s emotional state over time while watching. EVC is important due to the users who experience stable and positive emotions are more to have a better satisfaction. And frequent of emotional fluctuations may degrade perceived quality and lower ratings. Equation

4 is used to determine EVC:

In equation

4 variable Var, a measure of dispersion, it represents selected engagement-related metrics variance. LEAE stands for Likely Engagement and Attention Estimation, AES stands for AdEffectivenessScore. AES measures the impact of ads and FER or perceived relevance. FER stands for Face Emotion Recognition score that fluctuate during watching over time. The variance of these metrics means how many fluctuations of user’s emotional experience over time. A low variance refers to consistent metrics and high EVC. If it has high fluctuation, it means unstable emotional and reduction of EVC. Consistency has relationship with positive QoE. Usually, a user who has positive and steady emotions will remain engaged, attentive, and without feeling fatigued, and will have the opportunity to give a higher rating. Emotional fluctuations may mean sudden change from satisfaction to annoyance that can degrade QoE. EVC helps predict which content has an enjoyable experience and maintains stable emotion.

- (d)

LEAE (Likely Engagement and Attention Estimation) LEAE is used to assess content with ads effectiveness to capture and sustain user attention. In equation

5 variable AES means how ads align with user preferences, and LAC means ad exposure volume. Logarithm of AES means control of diminishing returns on ad relevance due to the most effective ads may reach saturation point.

,

,

,

refers to coefficients and · denote multiplication between the coefficients and variables. Targeted ads can improve QoE but in moderation by balancing relevance and quantity to avoid fatigue, as mentioned by Wojdynski and Evans in [

41]. A high LEAE means ads are relevant and placed effectively, high QoE and user retention. LEAE important for ad strategies optimization in which it aligns with user preferences, QoE and business goals. Equation

5 is used to determine LEAE:

- (e)

-

Frustration Recovery Rate (FRR) FRR is a metric to assess user resilience on disruptive ad, especially on negative emotion and repeated ad occurrences. In formula

6, the variable FER examines user facial frustration. Variable repeat means the existence of repeated ads, with a value of 1 means there are repeated ads, and 0 indicating no repetition. A high FRR refers to positive maintained engagement, although there exist ad frustrations. In contrast, a low FRR means susceptibility to repeated negative interruptions and negative emotion that leads to a higher potential for abandonment. Liu-Thompkins in [

43] claimed that there is a relationship between repetitive ads with user tolerance and frustration. If FRR is optimized, user retention and engagement will improve due to strategically reduced ad repetition with observed emotional cues over time. Equation

6 is used to determine FRR:

In Equation

6, the variable LAC represents the logarithmic scale of the ad count. Ad.each.min refers to the existence of ad each minute. Higher value means high ad interruptions and may lead to user frustration.

- 8.

Data Splitting (Node: Split Data into Train and Test Sets) The dataset was split into 20:80 Pareto ratio to improve objective assessment of model’s accuracy. For instance, 800 of 1000 rows were utilized for training while the remaining 200 were utilized for testing.

- 9.

Feature Scaling (Node: Scale Numerical Features) The numerical features like bitrate and content length are scaled for consistency to certain ranges.

- 10.

Dimensionality Reduction (Node: Apply PCA for Dimensionality Reduction) Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is applied to reduce complexity with maintain maximum variance to avoid overfitting. If there are 20 features, PCA will reduce it to 10 PCA and retain 95% variance.

- 11.

Feature Selection (Node: Perform Feature Selection using RFE with XGB) We use XGBoost to select the most important features, reduce noise and enhance generalization.

- 12.

Hyperparameter Tuning (Node: Hyperparameter Tuning for Individual Models) We use cross validation to tune hyperparameters including learningRate, treeDepth and regularization. We tune learningRate and maxDepth using Random Grid Search and Bayesian Optimization for search refining.

- 13.

Model Training and Evaluation (Nodes: Model Training and Prediction) We combined them with stacking classifier and evaluated with metrics such as accuracy, F1-score, precision, and recall.

- 14.

Model Explainability SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) is used to interpret how certain features impact predictions. Example: A model is trained using Stacking Classifier that combine ensemble learning technique to enhance accuracy by learning from other uniqueness [

42].

4. Results

We gathered the data set through unified frameworks hosted on

www.tisaselma.online and

www.xavyr.co.uk (both now decommissioned as data collection has concluded). In total, 194 completed questionnaires were collected, 43 participants completed video recordings with participants representing more than 120 different ethnicities and cities worldwide. The data of this questionnaire, comprising 103 rows and 194 columns, were used for semantic analysis. Table A1 in the Appendix presents the questions asked during the study, while Table A2 provides an overview of 10 rows of responses that will be used in the machine learning model.

The overview of combined data from network condition streaming, face emotion recognition while participant watching, and star rating feedback, ITU-T P.1203 can be seen in Table A3 in the Appendix A. In it we can see the video content and advertisement strategies summary.

4.1. User Demography

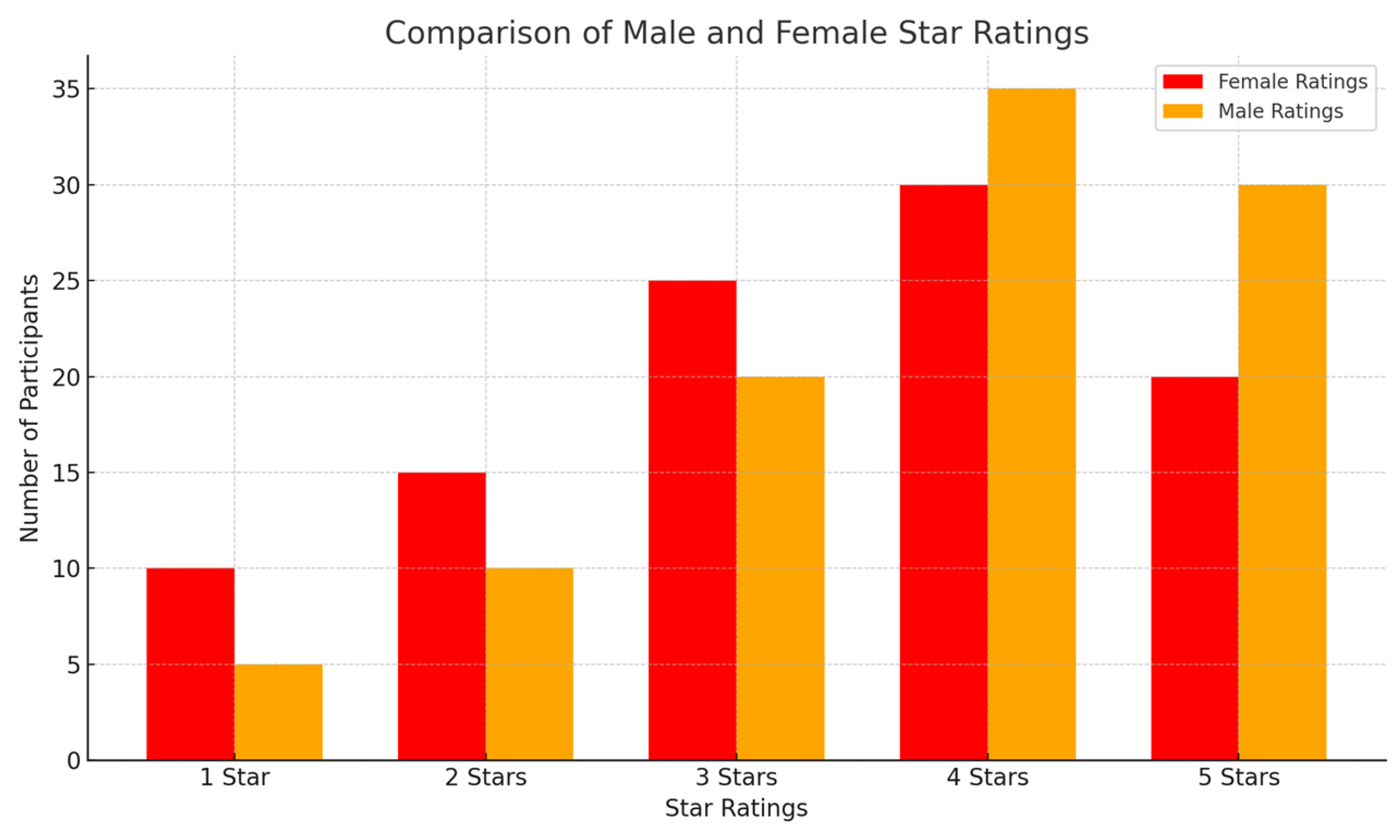

In

Figure 3, it is shown that the majority of the participants who answered this questionnaire are male (about 60% of 908 participants).

4.2. Questionnaire Results

In this section, we analyze the results of questions 1 to 10 in Table A1, with visual representation provided in

Figure 2 through

Figure 4. Moreover, as shown in

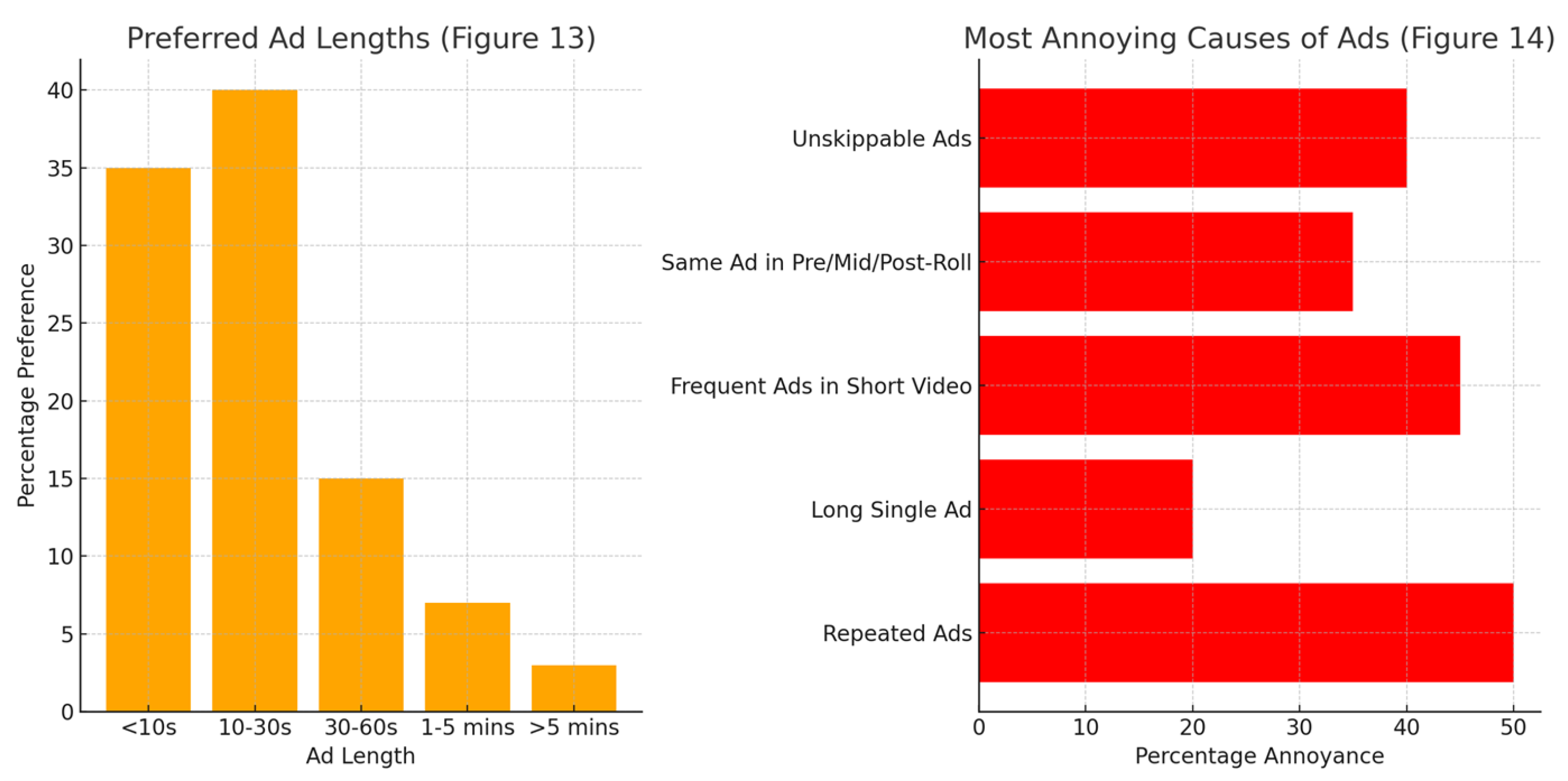

Figure 3, the dominant participant is male with 60% of participants. Users aged 21-30 have higher tolerance for pre-roll ads but lower tolerance for mid-roll and post-roll ads. From these results, ad placement can have more benefit by considering more personalized ads by gender and age preferences.

Figure 4 illustrates various user perceptions of ads in pre-roll, mid-roll, and post-roll placements. In detail, 32% of users have thought that pre-roll ads are “moderate.” However, some participants think that mid and post-roll are excessive and disturbing. These facts suggest that a more balanced frequency ad placement strategy is needed. The evidence is summarized in

Figure 4 and not all participants completely answer all the questions.

Figure 4 shows that mid-roll ads are considered the most annoying, primarily due to they have high frequency and unskippable. As seen in

Figure 4, mid-roll ads cause the highest annoyance. In contrast, post-roll ads are rated as “not at all” satisfactory after “moderate” and “neutral”, it may refer to some participants find pre-roll and mid-roll ads bothersome. From the questionnaire summarized in 5(a), the majority of participants prefer short ads under 30 seconds. In addition,

Figure 5(b). shows the necessity to manage ad frequency to prevent ad fatigue.

4.3. Sentiment Analysis (SA)

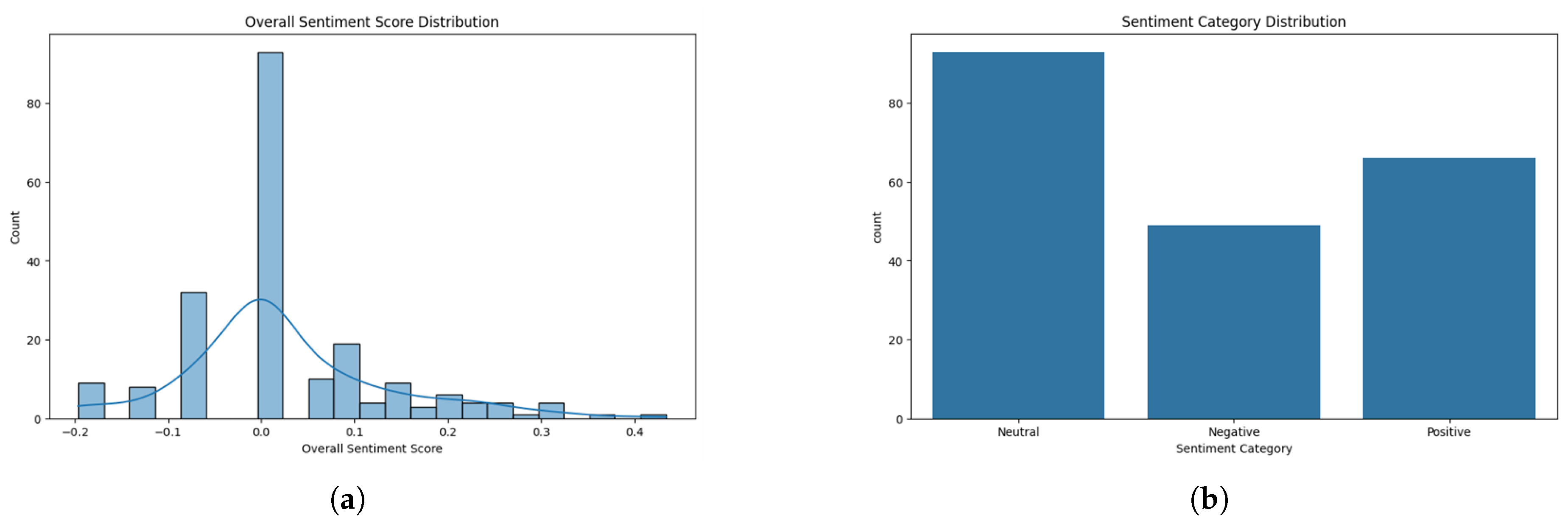

In our work, we leverage the capabilities of sentiment analysis during our machine learning data pre-processing. From our experiment, we summarize the results of our collected data as follows: neutral has 44.71%, positive sentiment indicated has 31.73% and negative sentiment recorded as 23.56%. We use NLTK and VADER to optimize ad strategies in a real time manner. Positive users allowed to watch higher ad loads to drive higher monetization, and conversely, neutral and negative users watch less intrusive ads to maintain their engagement. In

Figure 6.a illustrates sentiment category distributions during watching session. By observing SA, we can see participants emotional acceptance or rejection during ad content consumption over time and optimize strategies accordingly.

4.4. Data Analysis

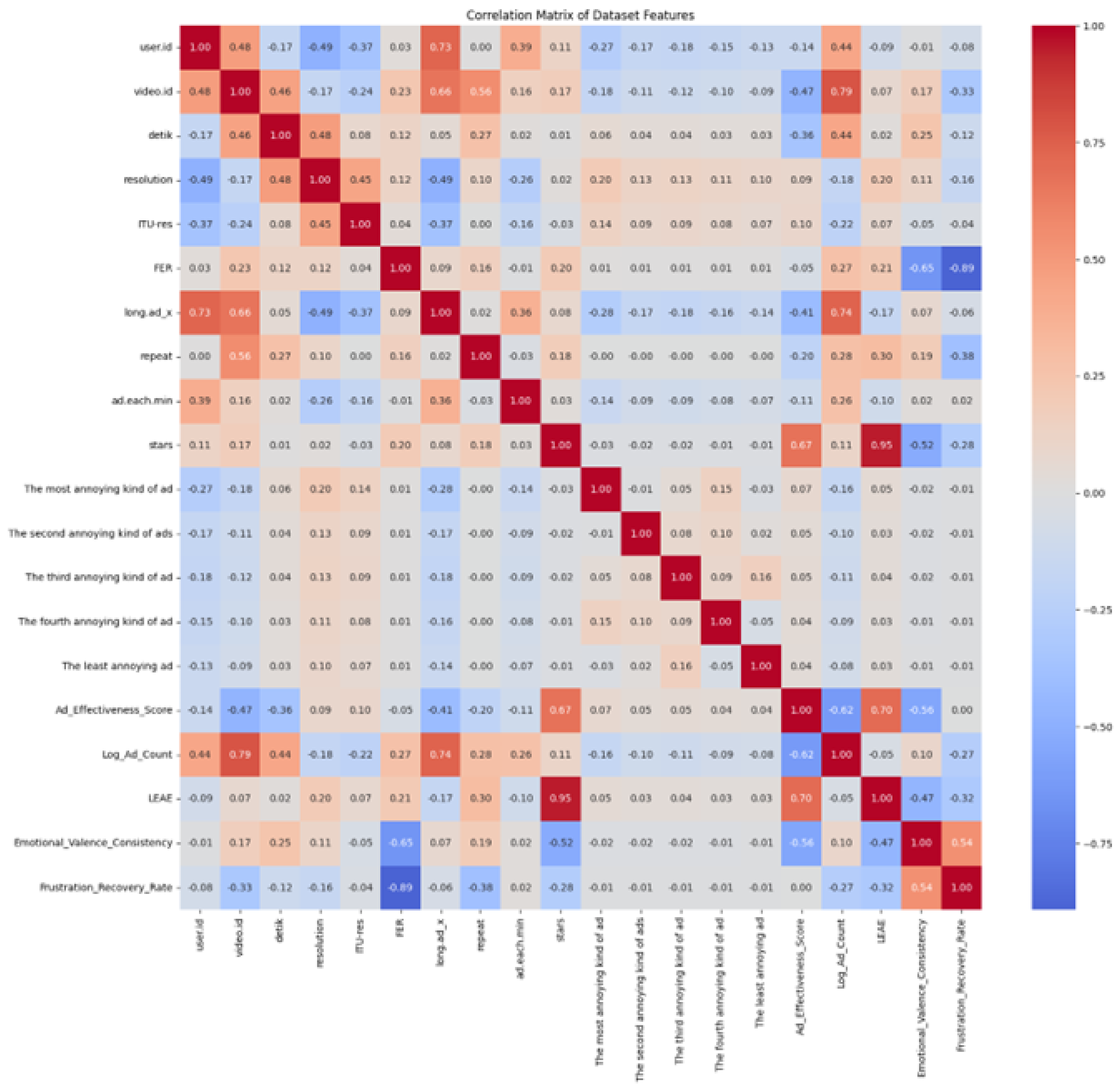

This subsection present data analysis of our own collected dataset. We use heat map analysis correlation matrix as seen in

Figure 7 to show relationship between each metrics. Red color means strong positive correlation, such as LEAE and ad.each.min. While blue color indicates strong negative correlations such as FER and FRR.

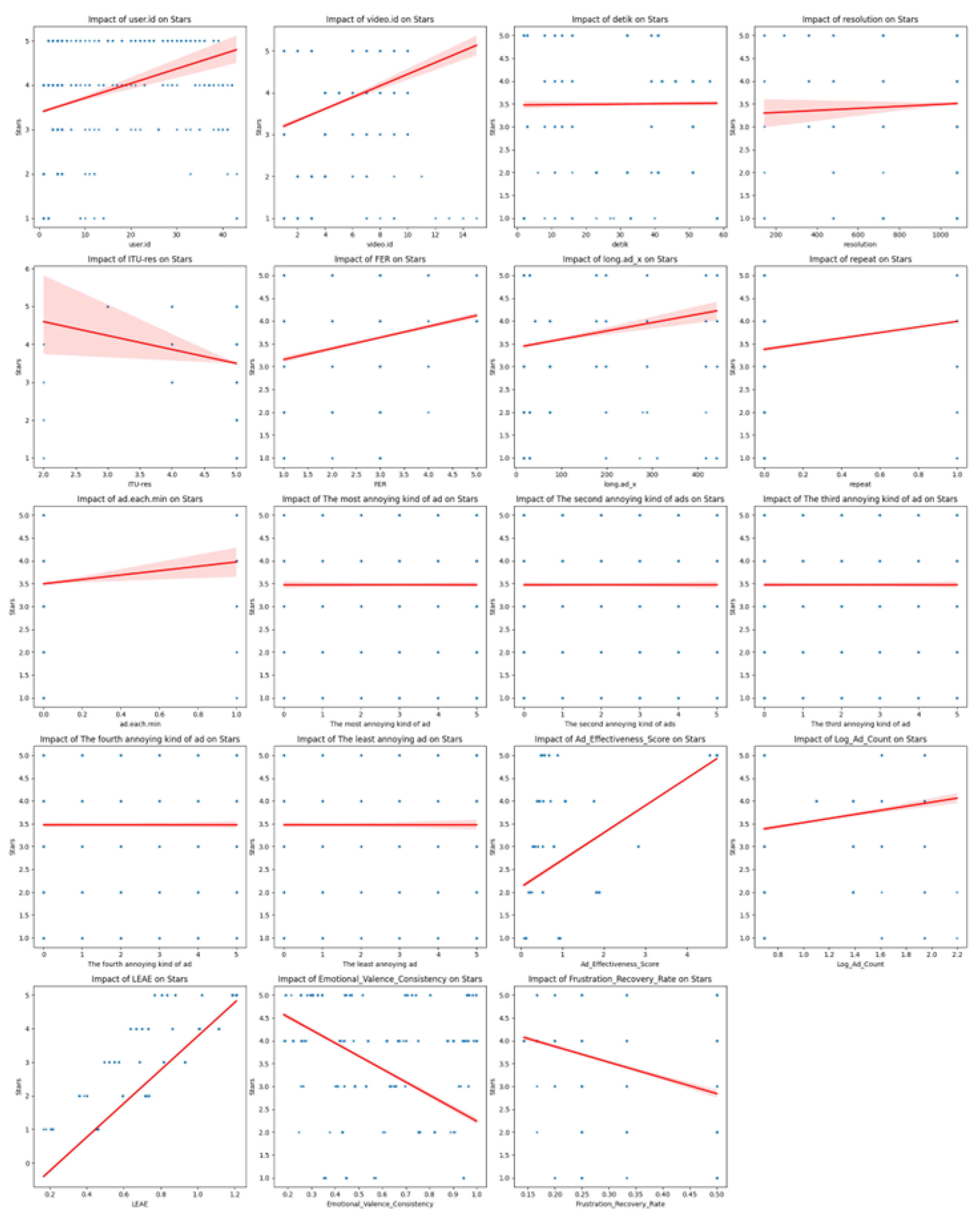

Figure 8 of feature importance bar chart and scatter plots shows the most dominant feature is LEAE to predict ’stars’. It means user will give high star rating due to consistently engaged with content. AES is the second most influential feature, means well-targeted and relevant ads may improve ’stars’. LAC and long.adX have less impact on ’stars’. LEAE and AES have strong positive correlations with ’stars’. These combined analysis give insight on multidimensional model of user engagement that can managed over time.

4.5. Machine Learning Results

The experimental results, summarized in

Table 3 examine the results before and after using PCA, RFE and SMOTEENN. Meanwhile in

Table 4 investigates various machine learning algorithms based on F1-score, precision, recall, and accuracy over three datasets: Own Collected Dataset, Advertising Dataset, and YouTube Comment Spam Dataset.

Table 3.

Class distribution and features before and after SMOTEENN, PCA, and RFE.

Table 3.

Class distribution and features before and after SMOTEENN, PCA, and RFE.

| Condition |

Feature |

Number of Samples |

| Class distribution before SMOTEENN |

1 |

95 |

| |

2 |

64 |

| |

3 |

32 |

| |

4 |

13 |

| |

5 |

11 |

| Class distribution after SMOTEENN |

1 |

95 |

| |

2 |

95 |

| |

3 |

95 |

| |

4 |

95 |

| |

5 |

95 |

| Features before PCA |

Name, Title, Resolusi, Bitrate, Itu, Fer, ContentLength, AdCount, LongAd, AdLoc, Repeat, Long5minAd, AdEachMin, PreMidPostSameAd, NoSkip |

| Features after PCA |

PC |

Top 3 Dominant Contributors |

| |

PC1 |

Long5minAd (0.444), Name (-0.411), ContentLength (0.317) |

| |

PC2 |

Itu (0.441), Fer (-0.254), ContentLength (-0.346) |

| |

PC3 |

AdLoc (0.549), Title (0.453), Long5minAd (0.299) |

| |

PC4 |

PreMidPostSameAd (0.480), LongAd (0.325), Bitrate (0.357) |

| |

PC5 |

title (0.454), itu (-0.413), bitrate (-0.407) |

| |

PC6 |

adCount (0.627), repeat (0.487), fer (0.332) |

| |

PC7 |

preMidPostSameAd (0.493), bitrate (0.340), repeat (0.204) |

| |

PC8 |

resolusi (0.505), name (0.443), contentLength (-0.294) |

| |

PC9 |

adEachMin (0.445), preMidPostSameAd (0.382), contentLength (0.157) |

| |

PC10 |

longAd (0.550), noSkip (-0.469), adLoc (-0.341) |

| |

PC11 |

noSkip (0.484), adCount (0.368), long5minAd (0.275) |

| |

PC12 |

long5minAd (0.503), adEachMin (0.386), title (-0.293) |

| Features before RFE |

Name, Title, Resolusi, Bitrate, Itu, Fer, ContentLength, AdCount, LongAd, AdLoc, Repeat, Long5minAd, AdEachMin, PreMidPostSameAd, NoSkip |

| Features after RFE |

Resolusi, Title, Long5minAd, ContentLength, Name, Name, AdCount, PreMidPostSameAd, Repeat |

Table 4.

Summary of Algorithm Performance Across Datasets.

Table 4.

Summary of Algorithm Performance Across Datasets.

| Algorithm |

F1 score |

Precision |

Recall |

Accuracy |

| Own Collected Dataset |

| AELIX Base Model (without Advanced Matrices) |

0.937 |

0.929 |

0.952 |

0.95 |

| AELIX (With Advanced Matrices) |

0.985 |

0.985 |

0.985 |

0.99 |

| Random Forest |

0.861 |

0.825 |

0.904 |

0.9 |

| Random Forest (with advanced metrics) |

0.905 |

0.914 |

0.905 |

0.905 |

| Decision Tree |

0.862 |

0.893 |

0.857 |

0.86 |

| Decision Tree (with advanced metrics) |

0.975 |

0.976 |

0.975 |

0.974 |

| XGBoost |

0.888 |

0.881 |

0.905 |

0.9 |

| XGBoost (with advanced metrics) |

0.943 |

0.946 |

0.942 |

0.942 |

| DNN |

0.937 |

0.929 |

0.952 |

0.95 |

| DNN (with advanced metrics) |

0.977 |

0.978 |

0.978 |

0.978 |

| LSTM |

0.865 |

0.837 |

0.905 |

0.9 |

| LSTM (with advanced metrics) |

0.35 |

0.387 |

0.388 |

0.379 |

| GRU |

0.581 |

0.731 |

0.619 |

0.62 |

| GRU (with advanced metrics) |

0.272 |

0.357 |

0.275 |

0.368 |

| CNN |

0.839 |

0.837 |

0.857 |

0.86 |

| CNN (with advanced metrics) |

0.977 |

0.978 |

0.977 |

0.977 |

| Advertising Public Dataset (Elmetwally, T. (n.d.)) |

| AELIX Base Model (without Advanced Matrices) |

0.8 |

0.802 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

| AELIX (With Advanced Matrices) |

0.9563 |

0.962 |

0.9563 |

0.96 |

| Random Forest |

0.9 |

0.912 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

| Random Forest (with advanced metrics) |

0.903 |

0.912 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

| XGBoost |

0.92 |

0.94 |

0.92 |

0.925 |

| XGBoost (with advanced metrics) |

0.903 |

0.912 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

| GRU |

0.7 |

0.701 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

| GRU (with advanced metrics) |

0.811 |

0.836 |

0.825 |

0.82 |

| CNN |

0.952 |

0.959 |

0.95 |

0.95 |

| CNN (with advanced metrics) |

0.952 |

0.959 |

0.95 |

0.95 |

| Decision Tree |

0.8571 |

0.88 |

0.85 |

0.85 |

| Decision Tree (with advanced metrics) |

0.928 |

0.943 |

0.925 |

0.93 |

| DNN |

0.877 |

0.882 |

0.875 |

0.875 |

| DNN (with advanced metrics) |

0.901 |

0.903 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

| LSTM |

0.69 |

0.733 |

0.675 |

0.68 |

| LSTM (with advanced metrics) |

0.872 |

0.872 |

0.875 |

0.88 |

| YouTube Comment Spam Public Dataset Shakira (Alberto, T., & Lochter, J. (2015)) |

| AELIX Base Model (without Advanced Matrices) |

0.913 |

0.929 |

0.911 |

0.91 |

| AELIX (With Advanced Matrices) |

0.954 |

0.954 |

0.954 |

0.95 |

| Random Forest |

0.925 |

0.938 |

0.924 |

0.924 |

| Random Forest (With Advanced Matrices) |

0.901 |

0.921 |

0.898 |

0.9 |

| XGBoost |

0.937 |

0.946 |

0.937 |

0.937 |

| XGBoost (With Advanced Matrices) |

0.901 |

0.921 |

0.898 |

0.9 |

| GRU |

0.807 |

0.807 |

0.81 |

0.81 |

| GRU (With Advanced Matrices) |

0.756 |

0.755 |

0.759 |

0.76 |

| CNN |

0.851 |

0.863 |

0.848 |

0.848 |

| CNN (with advanced metrics) |

0.888 |

0.897 |

0.886 |

0.89 |

| Decision Tree |

0.875 |

0.881 |

0.873 |

0.881 |

| Decision Tree (with advanced metrics) |

0.863 |

0.872 |

0.861 |

0.86 |

| DNN |

0.874 |

0.876 |

0.873 |

0.873 |

| DNN (with advanced metrics) |

0.824 |

0.826 |

0.823 |

0.82 |

| LSTM |

0.805 |

0.808 |

0.81 |

0.81 |

| LSTM (with advanced metrics) |

0.776 |

0.782 |

0.785 |

0.78 |

Meanwhile, in

Table 5 we present comparison summary of SMOTEENN, PCA and RFE combination results with meta learner XGBoost, Gradient Boosting, Random Forest and DNN and base learner logistic regression. The best performer is the combination of using SMOTEENN with PCA and RFE with precision, recall and f1 score up to 0.9. We choose to utilize PCA to reduces the feature space by retaining variance and helps to remove both redundancy and noise in our dataset. And we use RFE in order to select the most important features that contribute to the model’s predictive power while focusing on interpretability by using a specific model to rank features. We thought that using these combinations lead us to dimensionality reduction to retain maximum feature variance while retaining most significant features. The list of class distributions before and after SMOTEENN, PCA and RFE can be found in

Table 7.

Table 4 presents comparison result of different machine learning algorithms in predicting stars. We use Random Forest, Decision Tree, XGBoost, DNN, LSTM, GRU and CNN as comparison to our proposed approach AELIX. Meanwhile, in

Table 5, AELIX both with and without advanced metrics, consistently outperforms the other models. When we use advanced metrics, AELIX achieves the highest F1-score of 0.994, along with precision and recall scores of 0.994.

AELIX perform well without any usage of advanced metrics by achieving F1-score 0.937. AELIX with advanced metrics has the ability to capture more complex interactions between video content, advertisements, and user engagement. Moreover, XGBoost shows robust performance with F1-score 0.888 for our own collected dataset and 0.937 for YouTube Spam Dataset. XGBoost unable to show high accuracy in imbalance Advertising dataset due to it is excels in structured and large environment but lacks in capturing user specific data and ability to interpret most dominant feature. Accordingly, our proposed approach combine XGBoost and XAI using SHAP to handle XGBoost limitation.

In Advertising dataset, Random Forest shows competitive results with F1-score 0.861, although it struggles to handle our collected imbalanced dataset. Random Forest similar to XGBoost has limitation in real world video streaming imbalanced data where positive sentiment is underrepresented. Moreover, Neural Network (NN) model such as DNN and CNN have high accuracy and F1-score on YouTube Spam Public Dataset with 0.952 but has limitation in Advertising Dataset where user engagement and ad placement require fine-tuning and greater interpretability. However, Recurrent architectures such as GRU and LSTM are inappropriate for non-sequential task. It has shown by low F1-scores 0.581.

In

Table 6 we present the comparison of meta-learner algorithm with base estimators’ random forest, gradient boosting, XGBoost and DNN. The best meta-learner is logistic regression with up to 0.9 precision, recall and f1 score due to its effectiveness in cases where classes are linearly separable with less overfitting compared with other complex models like DNN or ensemble methods. Logistic regression is simple and has better generalization compared with more complex algorithms like Random Forest, Gradient Boosting and XGBoost.

Table 6.

Comparison summary of meta-learner algorithm results with base estimators’ random forest, gradient boosting, XGBoost and DNN.

Table 6.

Comparison summary of meta-learner algorithm results with base estimators’ random forest, gradient boosting, XGBoost and DNN.

| Meta-Learner |

Precision |

Recall |

F1 Micro Average |

| Random Forest |

0.5349 |

0.5349 |

0.5349 |

| KNN |

0.3953 |

0.3953 |

0.3953 |

| SVM |

0.5116 |

0.5116 |

0.5116 |

| Decision Tree |

0.3488 |

0.3488 |

0.3488 |

| Gradient Boosting |

0.3488 |

0.3488 |

0.3488 |

| Logistic Regression |

0.9286 |

0.9524 |

0.9365 |

In

Table 7 we can see the comparison of base learner with meta learner logistic regression. The best of all is the combination of Random Forest, XGBoost, Gradient Boosting and DNN with up to 0.9 of precision, recall and f1 score. This outstanding performance due to Random Forest nature in minimizing variance by combining multiple decision trees, while Gradient Boosting (GB) and XGBoost nature in reducing error via iterative learning that can capture all complex nonlinear relationships effectively. DNN complements these combinations by learning abstract and hierarchical features after PCA and RFE.

Table 7.

Summary comparison of base estimators with meta-learner logistic regression.

Table 7.

Summary comparison of base estimators with meta-learner logistic regression.

| Base Estimators |

Precision |

Recall |

F1 Micro Average |

| RandomForest, GradientBoosting, XGBoost |

0.4601 |

0.5349 |

0.4854 |

| RandomForest, SVM, DecisionTree |

0.4512 |

0.5116 |

0.4694 |

| KNN, XGBoost, ExtraTrees |

0.6283 |

0.5349 |

0.518 |

| MLP, GradientBoosting, DecisionTree |

0.4718 |

0.5581 |

0.5009 |

| RandomForest, MLP, SVM |

0.4086 |

0.4651 |

0.427 |

| ExtraTrees, DecisionTree, GradientBoosting |

0.4305 |

0.4884 |

0.4475 |

| KNN, RandomForest, GradientBoosting |

0.6256 |

0.5581 |

0.5284 |

| SVM, XGBoost, ExtraTrees |

0.4718 |

0.5349 |

0.4913 |

| RandomForest, GradientBoosting, XGBoost, DNN |

0.9286 |

0.9524 |

0.9365 |

4.6. SHAP Results

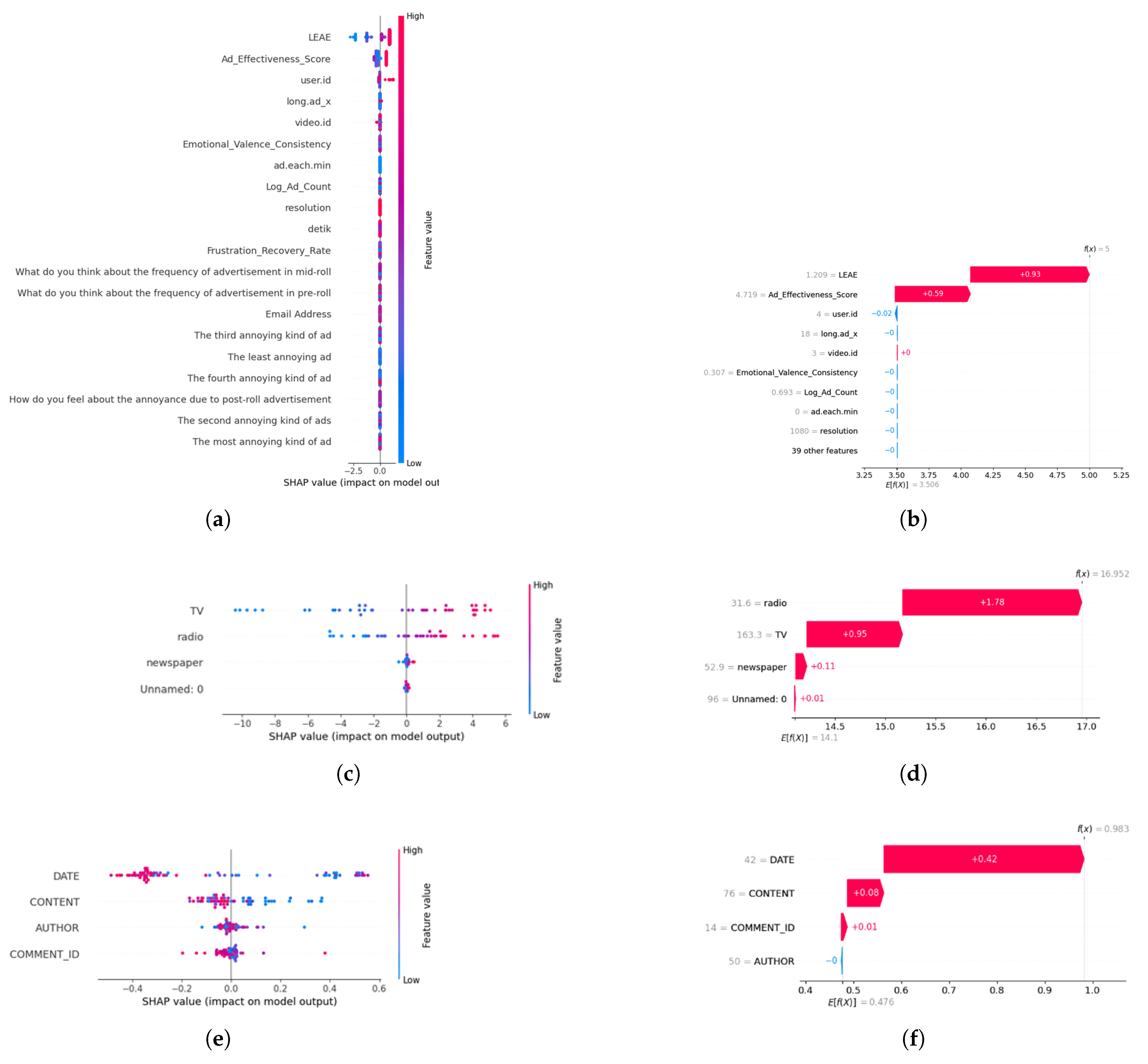

One of XAI techniques used in our proposed approach is SHAP (SHapley Additive Explanations) as shown in SHAP plots in

Figure 9. In

Figure 9 (a) and

Figure 9 (b), we discover the variables’ prediction influence of our collected dataset. AES related engagement has positive SHAP values means strong contribution to model’s predictions. LEAE has SHAP value

means higher engagement is directly correlated with an increased likelihood of a higher rating. Moreover, AES has

means relevance ad placement has strong relationship with user satisfaction. On the contrary, long.adX (

) and ad.each.min that has near-zero SHAP value has minimal or negative influence on user rating means repeated ad may degrade stars rating. These transparencies are crucial for data scientist and marketing strategists to optimize content delivery and ad effectiveness.

Figure 9(c) and

Figure 9(d) for Advertising Public Dataset show feature influence on different model predictions. The color gradient ranging from blue (low value) to red (high value) shows that high TV spending has positive influence in model output. Radio has a mixed influence with some negative influences. It can be seen that radio (+1.78) is the most dominant feature, followed by TV and newspaper. On the other hand,

Figure 9(e) and

Figure 9(f) for YouTube Spam Public Dataset have the most domineering feature as DATE, followed by CONTENT, and AUTHOR.

4.7. Experimental Results Analysis

Our experimental results reveal the impact of different types of ads on QoE. Mid-roll ads were found to be the most disruptive to QoE and significantly elicit a negative emotional response to the user. Meanwhile, pre-roll and post-roll ads have slightly deteriorated user engagement and lead to negative response. Our proposed approach successfully addresses the following research questions:

- 1.

Research Question #1: Can integrating multimodal data sources (facial emotion recognition, video metadata, network conditions, and user feedback) provide more accurate QoE predictions compared to traditional methods? Finding: Yes it can. Our proposed AELIX can achieve a high accuracy of about 0.95 in QoE predictions utilizing face emotion, ads placement strategies, network statistics, and several advanced metrics and outperforming state-of-the-art models and standard ITU-T P.1203 by 55.3%. It can be done in real time so that the stakeholder can manage automatic strategies accordingly over time.

- 2.

Research Question #2: How do different types of ads impact user engagement and emotional responses during video streaming? Finding: From our experimental results, mid-roll ads have the most impairment in QoE and user emotion, followed by pre-roll and post-roll ads. This finding supports our hypothesis that the timing and placement of advertisements significantly affect user satisfaction. consequently, a happy user can have more intense ads rather than an unhappy one.

- 3.

Research Question #3: Can XAI techniques improve transparency and decision making for stakeholders in video streaming services? Finding: The usage of SHAP as one of XAI can provide better insights on the most influential factor that may affect QoE for more informed decision-making process.

AELIX can be applied practically in companies like Netflix, YouTube, and Hulu, where real-time emotion recognition, ad and network condition observation can be leveraged to optimize a more personalized streaming experience. It can help advertising agencies to have more effective advertising campaign strategies. For network operators, these proposed alternatives offer data-driven insights for infrastructure enhancement and adaptive streaming strategies. In academic perspective, this proposed approach offers a robust framework and empirical evidence. Our future work will examine the usage of more adaptive technology that can better understand QoE and offers both personalized experience and privacy.

5. Conclusions

This study proposed AELIX, a multimodal framework to infer QoE in video streaming services utilizing user feedback, network statistics, video metadata analysis, and facial emotion recognition over time. AELIX integrates novel advanced metrics, adaptive ensemble learning, stacking classifier and XAI SHAP techniques to conquer our base model ITU-T P.1203 by 55.3% and accuracy 0.994. We assess AELIX effectiveness with our own collected data and two public datasets, including Advertising Dataset and YouTube Spam Dataset. From our findings, we found the efficacy of utilizing Emotional Valence Consistency (EVC), Log-Transformed Ad Count (LAC), and Frustration Recovery Rate (FRR) as novel advanced metrics to provide better understanding inferring and optimize QoE for stakeholders.

Our key contributions include our own video streaming collected dataset from more than 120 cities and countries around the world to ensure general background, propose novel advanced metrics that support ad management strategies and deployment of both offline and real time adaptive ad strategies optimization framework. These contributions offer alternative actionable insights for the service provider, content creator, advertising agency, and related stakeholder to better compromise between QoE and monetization revenue.

Although we discovered outstanding outcomes, it comes with certain limitations that need to be addressed in future research and challenges.Our study still needs to tackle lighting issue for face emotion recognition, different cultural expression of satisfaction and frustration, privacy and ethical concern to be developed widely in reality. Moreover, we still need to expand our dataset to wider range of types, format of ad and content. In addition, the incorporation of physiological data such as heart rate and eye tracking can provide more insight into understanding user engagement. In conclusion, this work discovers the advancement in the field of QoE assessment to deliver emotion driven insights for an alternative approach in understanding and optimizing QoE.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.S.; methodology, T.S.; software, T.S.; validation, T.S. ; formal analysis, T.S. ; investigation, T.S.; resources T.S..; data curation, T.S.; writing—original draft preparation, T.S.; writing—review and editing, T.S.; visualization, T.S.; supervision, T.S.; project administration, T.S.; funding acquisition, T.S.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is funded by the UAEU-ADU Joint Research Grant number 12T041.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further in-quiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to LanguageText for support in grammar and English writing, and ChatGPT and Gemini for help with brainstorming during our research work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Questions asked during the test.

Table A1.

Questions asked during the test.

| No. |

Questions |

Possible Answers |

| Q1 |

What do you think about the frequency of advertisement in pre-roll |

Few/ Many/ Moderate/ None |

| Q2 |

What do you think about the frequency of advertisement in mid-roll |

Few/ Many/ Moderate/ None |

| Q3 |

What do you think about the frequency of advertisement in post-roll |

Few/ Many/ Moderate/ None |

| Q4 |

Reduction of service experience due to pre-roll advertisement |

Advertisement make video QoE better/ Extremely reduced/ Moderately/ Not at all/ Slightly reduced |

| Q5 |

What do you think about the reduction of service experience due to mid-roll advertisement |

Advertisement make video QoE better/ Extremely reduced/ Moderately/ Not at all/ Slightly reduced |

| Q6 |

What do you think about the reduction of service experience due to post-roll advertisement |

Advertisement make video QoE better/ Extremely reduced/ Moderately/ Not at all/ Slightly reduced |

| Q7 |

How do you feel about the annoyance due to pre-roll advertisement |

Extremely Annoying/ I am happy to watch pre-roll advertisement/ Moderately/ Neutral/ Not at all |

| Q8 |

How do you feel about the annoyance due to mid-roll advertisement |

Extremely Annoying/ I am happy to watch pre-roll advertisement/ Moderately/ Neutral/ Not at all |

| Q9 |

How do you feel about the annoyance due to post-roll advertisement |

Extremely Annoying/ I am happy to watch pre-roll advertisement/ Moderately/ Neutral/ Not at all |

| Q10 |

What is your opinion about maximum acceptable advertisement length period |

None/ less than 10s/ 10-30s/ 30-60s/ 1-5 minutes/ more than 5minutes |

| Q11 |

Please reorder from the most annoying to the least |

Many repeated advertisements in 1 point of time in mid-roll/ Single 5 minutes advertisement long in mid-roll/ in 5 minutes video content, every 1 minute there is one repeated ads/ Same ads repeatedly in pre, mid, post-roll/ There is no skippable ads |

Appendix A.2

Table A2.

Overview of questionnaire data used for semantic analysis.

Table A2.

Overview of questionnaire data used for semantic analysis.

| Timestamp |

2/28/2022 19:40 |

3/1/2022 0:53 |

3/5/2022 2:55 |

3/6/2022 20:51 |

3/7/2022 14:49 |

3/10/2022 16:13 |

3/14/2022 13:05 |

3/17/2022 22:34 |

3/20/2022 19:27 |

| Email Address |

Ra***@gmail.com |

20**@uaeu.ac.ae |

Ok**@gmail.com |

Ra**@hotmail.com |

Ro**@gmail.com |

Mu**@gmail.com |

Le**@gmail.com |

Ka**@gmail.com |

Tr**@gmail.com |

| What do you think about the frequency of advertisement in pre-roll |

Few |

Many |

Most all time |

Many |

Few |

Many |

None |

Most all time |

Many |

| What do you think about the frequency of advertisement in mid-roll |

Many |

Many |

Most all time |

Many |

Few |

Many |

Few |

Most all time |

Few |

| What do you think about the frequency of advertisement in post-roll |

Some |

Many |

Some |

None |

Few |

Many |

Some |

Many |

Many |

| How bodily relaxed / aroused are you after watching first video (Title: How This Guy Found a Stolen Car!)? [(A) Relaxed - (B) Stimulated] |

A |

A |

A |

A |

A |

A |

A |

B |

B |

| How bodily relaxed / aroused are you after watching first video (Title: How This Guy Found a Stolen Car!)? [(A) Calm - (B) Excited] |

A |

A |

B |

B |

A |

B |

A |

B |

B |

| How bodily relaxed / aroused are you after watching first video (Title: How This Guy Found a Stolen Car!)? [(A) Sluggish - (B) Frenzied] |

B |

A |

B |

B |

A |

A |

A |

B |

B |

| How bodily relaxed / aroused are you after watching first video (Title: How This Guy Found a Stolen Car!)? [(A) Dull - (B) Jittery] |

A |

A |

B |

A |

B |

A |

A |

B |

B |

| How bodily relaxed / aroused are you after watching first video (Title: How This Guy Found a Stolen Car!)? [(A) Sleepy - (B) Wide Awake] |

B |

A |

B |

B |

B |

A |

B |

B |

B |

Appendix A.3

Table A3.

Video content and advertisement summary.

Table A3.

Video content and advertisement summary.

| Content Title |

Length of Content (s) |

Number of Ad |

Length of Ad (s) |

Position of Ad |

| Expo 2020 Dubai |

280 |

1 |

18 |

Post-roll |

| Squid game2 |

113 |

1 |

30 |

Pre-roll |

| Every death game SG |

375 |

1 |

18 |

Mid-roll |

| 5 metaverse |

461 |

3 |

75 |

Pre, Mid, Post-roll |

| Created Light from Trash |

297 |

2 |

45 |

Pre-roll |

| How this guy found a stolen car! |

171 |

6 |

288 |

Pre, Mid, Post-roll |

| First underwater farm |

233 |

6 |

198 |

Pre, Mid, Post-roll |

| Most beautiful building in the world |

166 |

6 |

292 |

Mid-roll |

| This is made of...pee?! |

78 |

4 |

418 |

Pre-roll |

| The most unexplored place in the world |

256 |

5 |

391 |

Post-roll |

| Jeda Rodja 1 |

387 |

8 |

279 |

Pre-roll |

| Jeda Rodja 2 |

320 |

8 |

440 |

Pre, Mid, Post-roll |

| Jeda Rodja 3 |

415 |

6 |

272 |

Pre, Mid, Post-roll |

| Jeda Rodja 4 |

371 |

6 |

311 |

Post-roll |

| Jeda Rodja 5 |

376 |

6 |

311 |

Mid-roll |

References

- International Telecommunication Union. Recommendation ITU-T P.1203.3, Parametric Bitstream-Based Quality Assessment of Progressive Download and Adaptive Audiovisual Streaming Services over Reliable Transport-Quality Integration Module. 2017. Available online: https://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-P.1203.3/en (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- M, V. P. K.; Ghosh, M.; Mahapatra, S. No-reference video quality assessment from artifacts and content characteristics: A neuro-fuzzy framework for video quality evaluation. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2024, 83, 48049–48074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Li, J.; Zhuo, L.; Yang, S. VCFNet: Video clarity-fluency network for quality of experience evaluation model of HTTP adaptive video streaming services. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2022, 81, 42907–42923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selma, T.; Masud, M. M.; Bentaleb, A.; Harous, S. Inference Analysis of Video Quality of Experience in Relation with Face Emotion, Video Advertisement, and ITU-T P.1203. Technologies 2024, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Mansoor, A. B.; Barakabitze, A. A.; Hines, A.; Atzori, L.; Walshe, R. Supervised-learning-Based QoE Prediction of Video Streaming in Future Networks: A Tutorial with Comparative Study. IEEE Communications Magazine 2021, 59, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaka-Čekić, F.; Baraković Husić, J. A feature selection for video quality of experience modeling: A systematic literature review. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kougioumtzidis, G.; Vlahov, A.; Poulkov, V. K.; Lazaridis, P. I.; Zaharis, Z. D. QoE Prediction for Gaming Video Streaming in O-RAN Using Convolutional Neural Networks. IEEE Open Journal of the Communications Society 2024, 5, 1167–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligata, A.; Perenda, E.; Gacanin, H. Quality of Experience Inference for Video Services in Home WiFi Networks. IEEE Communications Magazine 2018, 56, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkan, U.; Dagiuklas, T.; Iqbal, M. Modelling Quality of Experience for Online Video Advertisement Insertion. IEEE Transactions on Broadcasting 2020, 66, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.; Hamby, A. It’s Written on Your Face: How Emotional Variation in Super Bowl Advertisements Influences Ad Liking. Journal of Advertising 2024, 53, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, G.; MacEdo, D. F.; Marquez-Barja, J. M. Estimating Video on Demand QoE From Network QoS Through ICMP Probes. IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management 2022, 19, 1890–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsolic, I.; Skorin-Kapov, L. A Framework for in-Network QoE Monitoring of Encrypted Video Streaming. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 74691–74706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, M.; Pradas, D.; Royer, M.; Lochin, E. Unveiling YouTube QoE Over SATCOM Using Deep-Learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 39978–39994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Chen, H.; Xu, Y.; Ma, Z.; Xu, X. Learning Accurate Network Dynamics for Enhanced Adaptive Video Streaming. IEEE Transactions on Broadcasting. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Luo, Z.; Hu, M.; Wu, D. PreSR: Neural-Enhanced Adaptive Streaming of VBR-Encoded Videos with Selective Prefetching. IEEE Transactions on Broadcasting 2023, 69, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cheng, S.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, X. Inferring Video Streaming Quality of Real-time Communication inside Network. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology. [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Qin, S.; Xiao, Q.; Jiang, W.; Tang, X.; Li, X. Adaptive Bitrate Algorithms via Deep Reinforcement Learning With Digital Twins Assisted Trajectory. IEEE Transactions on Network Science and Engineering 2024, 11, 3522–3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yu, Z.; Yu, H.; Liu, S.; Xie, Y.; Guo, B.; Liu, Y. AdaEvo: Edge-Assisted Continuous and Timely DNN Model Evolution for Mobile Devices. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing. [CrossRef]

- Sedlak, B.; Pujol, V. C.; Donta, P. K.; Dustdar, S. Equilibrium in the Computing Continuum through Active Inference. Future Generation Computer Systems 2024, 160, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiche, F.; ben Letaifa, A.; Aguili, T. QoE-aware traffic monitoring based on user behavior in video streaming services. Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience 2023, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolec, I.; Orsolic, I.; Skorin-Kapov, L. Impact of User Playback Interactions on In-Network Estimation of Video Streaming Performance. IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management 2022, 19, 3547–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Zhang, H.; Hu, H.; Wen, Y.; Cai, J.; Luo, C.; Zeng, W. Optimizing Quality of Experience for Adaptive Bitrate Streaming via Viewer Interest Inference. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2018, 20, 3399–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kasteren, A.; Brunnström, K.; Hedlund, J.; Snijders, C. Quality of experience of 360 video—Subjective and eye-tracking assessment of encoding and freezing distortions. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2022, 81, 9771–9802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.; Vats, S.; van Damme, S.; van der Hooft, J.; Vega, M. T.; Wauters, T.; de Turck, F.; Timmerer, C.; Hellwagner, H. Characterization of the Quality of Experience and Immersion of Point Cloud Videos in Augmented Reality Through a Subjective Study. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 128898–128910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Chuai, G.; Gao, W.; Liu, Q. Cellular QoE Prediction for Video Service Based on Causal Structure Learning. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2023, 24, 7541–7551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Shao, S.; Tunc, C.; Satam, P.; Hariri, S. An Explainable and Efficient Deep Learning Framework for Video Anomaly Detection. Cluster Computing 2022, 25, 2715–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, S. M.; Lee, S. I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Qian, J.; Cao, J. How Video Cover Images Influence Pre-Roll Advertisement Clicks: The Value of Emotional Faces in Driving Attention to the Advertisement. Journal of Advertising Research 2023, 63, 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepelenko, A.; Kosonogov, V.; Shestakova, A. How Emotions Induce Charitable Giving: A Psychophysiological Study. Social Psychology 2023, 54, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Yang, X. J.; de Winter, J. C. F. Using Eye-Tracking Data to Predict Situation Awareness in Real Time during Takeover Transitions in Conditionally Automated Driving. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2022, 23, 2284–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Torres, M.; Pinto-Roa, D. P.; Núñez-Castillo, C.; Quiñonez, B.; Vázquez, G.; Allegretti, M.; García-Diaz, M. E. Feature Selection Applied to QoS/QoE Modeling on Video and Web-Based Mobile Data Services: An Ordinal Approach. Computer Communications 2024, 217, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N. V.; Bowyer, K. W.; Hall, L. O.; Kegelmeyer, W. P. SMOTE: Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling Technique. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, G. E.; Prati, R. C.; Monard, M. C. A Study of the Behavior of Several Methods for Balancing Machine Learning Training Data. ACM SIGKDD Explorations Newsletter 2004, 6, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Machine Learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, A.; Wiener, M. Classification and Regression by RandomForest. R News 2002, 2, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, J. H. Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine. Annals of Statistics 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Alberto, T.; Lochter, J. YouTube Spam Collection [Dataset]. UCI Machine Learning Repository. [CrossRef]

- Elmetwally, T. Advertising Dataset [Dataset]. Kaggle. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/tawfikelmetwally/advertising-dataset.

- Budianto, A. G.; et al. Sentiment Analysis Model for KlikIndomaret Android App during Pandemic Using VADER and Transformers NLTK Library. 2022 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM) 2022, pp. 281–286. [CrossRef]

- Wojdynski, B. W.; Evans, N. J. Going Native: Effects of Disclosure Position and Language on the Recognition and Evaluation of Online Native Advertising. Journal of Advertising 2016, 45, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, D. H. Stacked Generalization. In Neural Networks 1992, 5.

- Liu-Thompkins, Y. A Decade of Online Advertising Research: What We Learned and What We Need to Know. Journal of Advertising 2019, 48, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutto, C.; Gilbert, E. VADER: A Parsimonious Rule-Based Model for Sentiment Analysis of Social Media Text. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 2014, 8, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).