2. Generative Techniques for LVLMs

In this section, we will provide an in-depth exploration of various generative techniques employed in LVLMs. These techniques play a crucial role in enhancing the model’s ability to generate coherent and contextually relevant outputs across both visual and linguistic domains. We will examine how these methods enable the integration of image and text modalities, allowing LVLMs to generate images from textual descriptions, produce captions from images, or answer visual questions. Additionally, we will discuss key advancements that have contributed to the growing effectiveness of generative AI in LVLMs, including the development of multimodal transformers, cross-attention mechanisms, and large-scale pretraining on diverse datasets.

CLIP: CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pretraining) is a groundbreaking approach developed by OpenAI that redefines how vision-language models are trained and utilized. Instead of relying on fixed, predetermined labels, CLIP uses natural language supervision by jointly training an image encoder and a text encoder to predict which image-text pairs are correctly aligned. [

4] The pre-training is performed on a massive dataset of 400 million (image, text) pairs sourced from the internet, enabling the model to learn from a wide variety of visual and linguistic contexts without the need for manual labeling.One of the most significant aspects of CLIP is its ability to transfer its learned representations to various downstream tasks in a zero-shot manner, meaning it does not require additional fine-tuning or retraining for specific tasks. This allows CLIP to perform competitively across a diverse range of tasks, including object classification, optical character recognition (OCR), action recognition, geo-localization, and many types of fine-grained object detection. The model’s effectiveness is evident in its ability to match or even surpass fully supervised baselines like ResNet-50 [

23] on ImageNet [

21], without having seen any of the labeled training examples. The core mechanism of CLIP is its contrastive pre-training objective, where it learns to maximize the similarity between correctly paired images and text while minimizing it for incorrect pairs. This creates a shared multi-modal embedding space where both visual and textual representations can be compared, significantly enhancing the model’s capacity to generate accurate and contextually aware outputs. The success of CLIP demonstrates the power of leveraging natural language as a flexible supervision signal, which can express a broader range of visual concepts than traditional label-based approaches. In conclusion, CLIP has proven to be a highly versatile and efficient model for vision-language tasks, demonstrating remarkable zero-shot transfer performance across a wide range of computer vision datasets and tasks, including OCR, action recognition, and fine-grained object classification. The scalability of CLIP ensures that as compute and data resources increase, so does its capability to transfer to new tasks, making it a valuable tool for large-scale applications. CLIP’s cross-modal architecture, which allows for seamless integration of text and image processing, adds significant value by enabling complex tasks such as text-based image retrieval, image captioning, and visual question answering with a high degree of accuracy.However, while CLIP’s flexibility and broad generalization capabilities are impressive, they also bring forth important ethical concerns. Issues such as model bias, content generation control, and the potential risks of deploying zero-shot models in real-world environments without thorough safeguards must be carefully considered. Overall, CLIP represents a significant step forward in vision-language modeling, offering both opportunities and challenges in its practical implementation and ethical use.

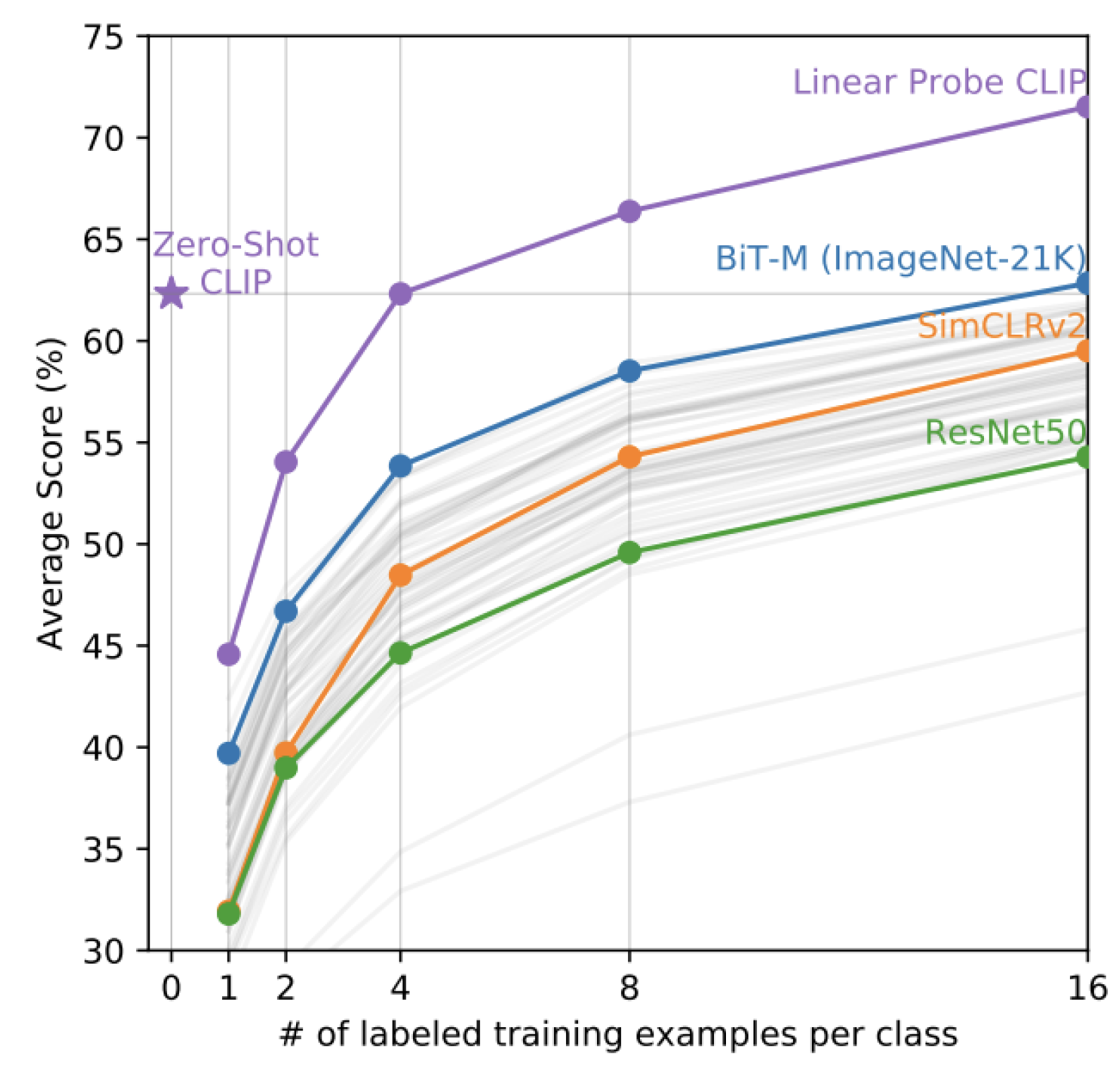

Figure 1.

Zero-shot CLIP surpasses few-shot linear probes, matching the average performance of a 4-shot linear classifier trained on the same feature space. It nearly matches the best performance of a 16-shot linear classifier across publicly available models. In the evaluation, BiT-M and SimCLRv2 models are highlighted as top performers, while light gray lines represent other models in the evaluation suite. The analysis used 20 datasets, each with at least 16 examples per class, showcasing CLIP’s robustness even without additional training.(Fig. credit: [

4]).

Figure 1.

Zero-shot CLIP surpasses few-shot linear probes, matching the average performance of a 4-shot linear classifier trained on the same feature space. It nearly matches the best performance of a 16-shot linear classifier across publicly available models. In the evaluation, BiT-M and SimCLRv2 models are highlighted as top performers, while light gray lines represent other models in the evaluation suite. The analysis used 20 datasets, each with at least 16 examples per class, showcasing CLIP’s robustness even without additional training.(Fig. credit: [

4]).

Flamingo: In the Flamingo [

24] paper, DeepMind introduces a sophisticated vision-language model designed to perform few-shot learning across a wide range of tasks, such as image captioning, video understanding, and visual question-answering. Flamingo leverages the pre-trained CLIP model’s approach by combining a frozen vision encoder (NFNet) and a large frozen language model. Key innovations include the Perceiver Resampler, which reduces the computational burden by transforming visual features into a fixed number of tokens, and cross-attention layers, which integrate visual information with text-based predictions.Flamingo uses a contrastive pre-training strategy, similar to CLIP, on vast amounts of multimodal data gathered from the web, bypassing the need for manually labeled datasets. This method helps create shared cross-modal representations that allow the model to handle diverse tasks with minimal task-specific data. The model also incorporates cross-attention layers between frozen language model layers, enabling it to condition text generation on visual inputs effectively. These layers allow Flamingo to ingest interleaved sequences of images, videos, and text, producing contextually relevant text outputs. Flamingo significantly outperforms existing fine-tuned models on tasks like visual question-answering (VQA), image-text alignment, and video captioning, using substantially fewer training examples. Its few-shot learning capability allows it to adapt to new tasks with just a handful of examples, highlighting the model’s scalability and efficiency in multimodal learning environments. In essence, Flamingo expands upon CLIP’s innovations by enhancing the model’s capacity to handle both textual and visual inputs simultaneously, making it an advanced tool for a variety of vision-language tasks with minimal data-specific fine-tuning.

In reflecting on Flamingo’s architecture and capabilities, one can observe its remarkable ability to bridge the gap between visual and textual inputs using minimal task-specific training data. This model exemplifies the next evolution of vision-language models by effectively leveraging frozen pre-trained components, making it both efficient and scalable. The integration of the Perceiver Resampler and cross-attention layers is particularly innovative, allowing Flamingo to process multimodal inputs seamlessly. In my view, Flamingo sets a strong precedent for future multimodal models that aim to handle complex real-world tasks with minimal data and fine-tuning efforts. Its performance on few-shot learning benchmarks further highlights its flexibility, making it an important contribution to the field of AI.

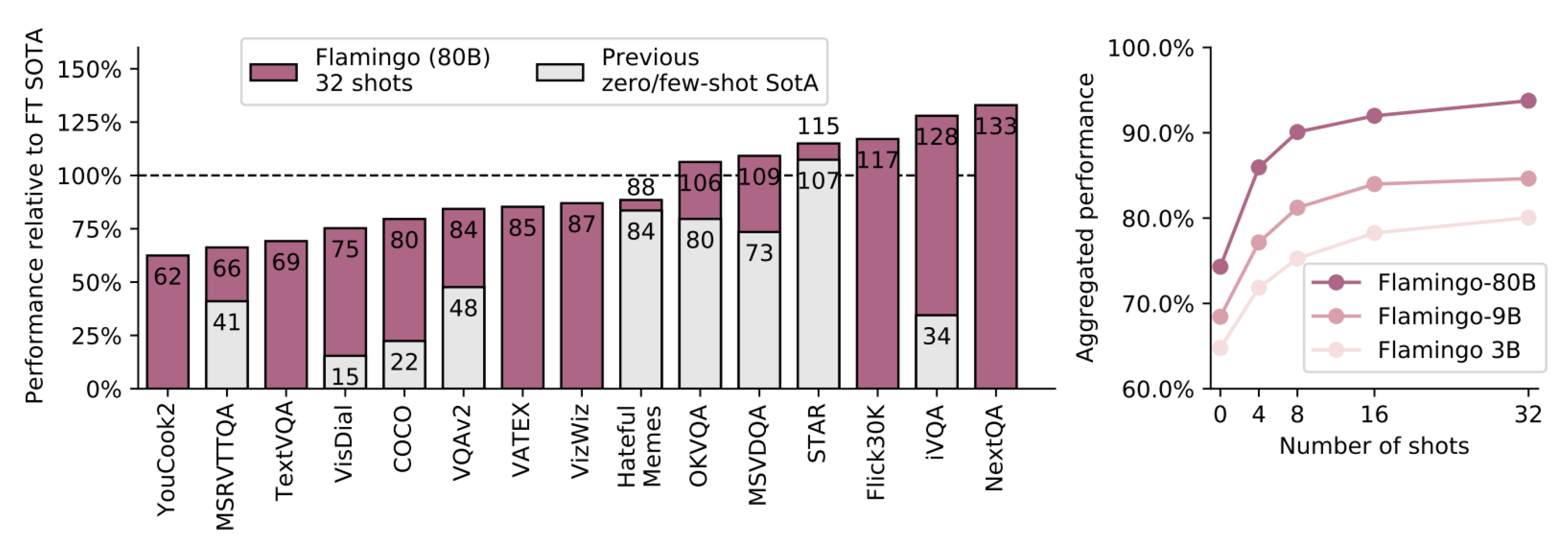

Figure 2.

Flamingo result overview.Flamingo’s largest model outperforms state-of-the-art fine-tuned models on 6 out of 16 tasks without fine-tuning, setting new benchmarks for few-shot learning on 9 tasks. Its performance improves with model size and the number of shots, showcasing scalability and adaptability. The RareAct benchmark was excluded due to a lack of fine-tuned results for comparison. (Fig. credit: [

24]).

Figure 2.

Flamingo result overview.Flamingo’s largest model outperforms state-of-the-art fine-tuned models on 6 out of 16 tasks without fine-tuning, setting new benchmarks for few-shot learning on 9 tasks. Its performance improves with model size and the number of shots, showcasing scalability and adaptability. The RareAct benchmark was excluded due to a lack of fine-tuned results for comparison. (Fig. credit: [

24]).

BLIP : In this paper BLIP [

25] presents a novel framework designed to integrate both understanding and generation capabilities within a single model architecture. The authors introduce the Multimodal Mixture of Encoder-Decoder (MED) model, which can function as a unimodal encoder (for separate image and text encoding), an image-grounded text encoder, or an image-grounded text decoder. This flexible architecture allows BLIP to address a range of tasks, such as image-text retrieval and caption generation. The model is trained using three objectives: Image-Text Contrastive (ITC) Loss, which aligns image and text features for distinguishing positive and negative pairs; Image-Text Matching (ITM) Loss, which refines the model’s ability to recognize matched image-text pairs; and Language Modeling (LM) Loss, which enables the model to generate accurate textual descriptions of images. One of BLIP’s key innovations is the CapFilt method, which improves the quality of its training data by generating synthetic captions and filtering out noisy image-text pairs, ensuring better alignment between the modalities. BLIP’s use of large-scale web datasets, combined with human-annotated datasets, enables it to perform well across multiple tasks. The results show that BLIP outperforms existing models in both vision-language understanding and generation, setting new benchmarks in tasks like image-text retrieval and captioning. This framework’s unified approach makes it an efficient solution for multimodal learning, demonstrating strong generalization to various datasets.

When compared to state-of-the-art models in the vision-language domain, BLIP demonstrates superior performance across various benchmarks. Unlike models such as CLIP and ALIGN, which primarily focus on either understanding or retrieval tasks, BLIP’s unified encoder-decoder architecture enables it to excel in both vision-language understanding (e.g., image-text retrieval) and generation (e.g., captioning). Additionally, the integration of the CapFilt method distinguishes BLIP from its counterparts by addressing the issue of noisy data in web-crawled datasets. This filtering mechanism ensures that BLIP learns from high-quality image-text pairs, which enhances its ability to perform multimodal alignment more effectively.In terms of few-shot and zero-shot learning, BLIP also outperforms state-of-the-art models on several popular datasets such as COCO and Visual Genome. Its pre-training on a combination of human-annotated and web datasets gives it a competitive edge over models like SimVLM and UNITER, which rely heavily on human-labeled data. Furthermore, BLIP’s ability to handle both image-text retrieval and generation tasks in a unified framework positions it as a more versatile solution compared to models that specialize in only one of these areas. Overall, BLIP sets new performance benchmarks while demonstrating more robust generalization capabilities across a variety of vision-language tasks.

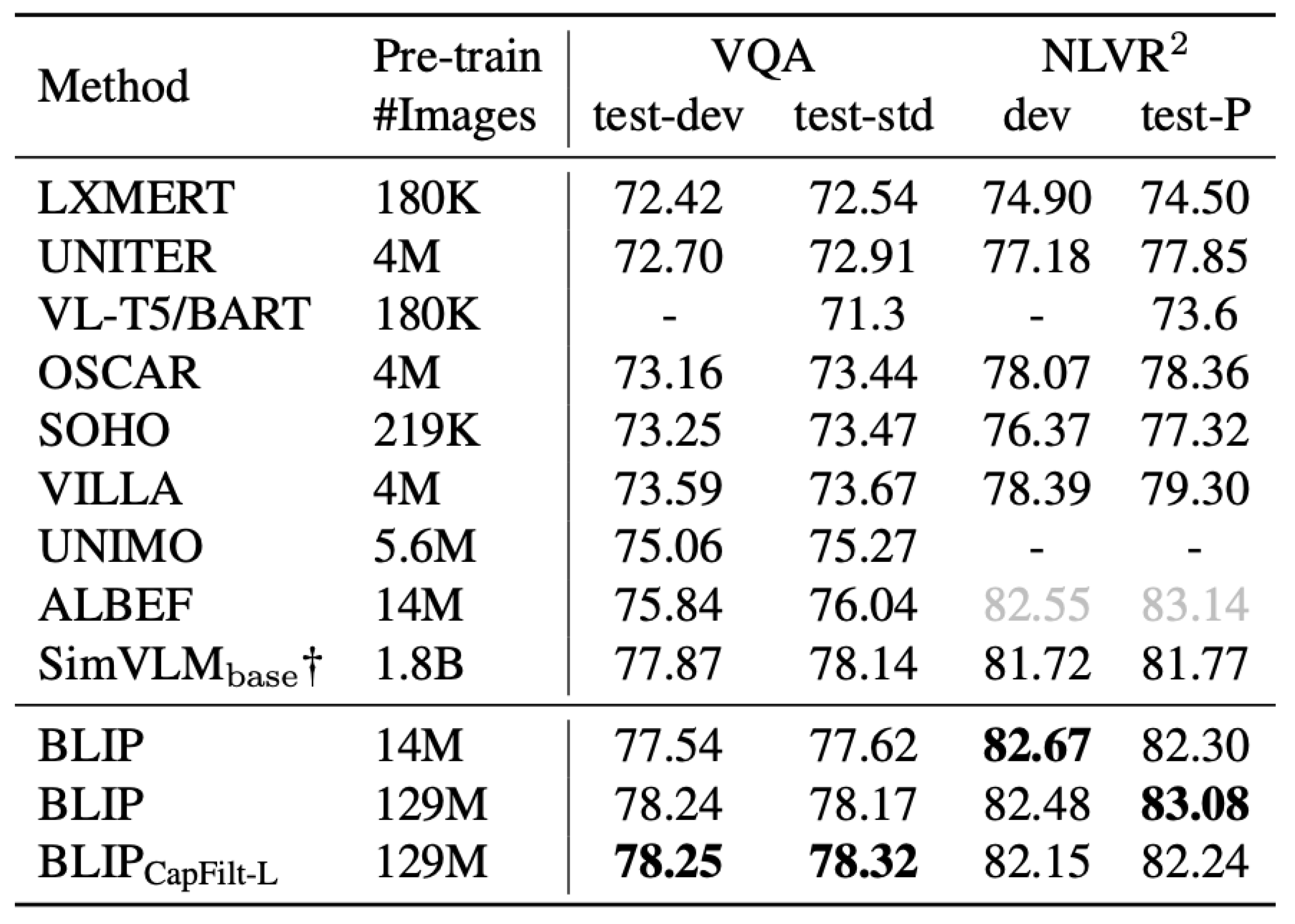

Figure 3.

In comparison with state-of-the-art methods on VQA and NLVR2, ALBEF includes an additional pre-training step specifically for the NLVR2 task. SimVLM†, on the other hand, utilizes 13 times more training data than BLIP and employs a larger vision backbone, combining ResNet and ViT, to enhance performance. Despite these advantages in data and architecture, BLIP demonstrates competitive results, highlighting its efficiency and effectiveness with a more streamlined approach. (Fig. credit: [

25]).

Figure 3.

In comparison with state-of-the-art methods on VQA and NLVR2, ALBEF includes an additional pre-training step specifically for the NLVR2 task. SimVLM†, on the other hand, utilizes 13 times more training data than BLIP and employs a larger vision backbone, combining ResNet and ViT, to enhance performance. Despite these advantages in data and architecture, BLIP demonstrates competitive results, highlighting its efficiency and effectiveness with a more streamlined approach. (Fig. credit: [

25]).

UniT: In this paper UniT [

26] introduces a versatile framework that unifies various tasks across different domains, such as object detection, natural language understanding, and multimodal reasoning, within a single Transformer-based model. The UniT model is based on an encoder-decoder architecture, where separate encoders handle different input modalities (like images and text), and a shared decoder works across tasks. This allows for joint training and effective multitasking, significantly reducing the number of parameters compared to training separate models for each task.UniT achieves this multitasking capability by sharing the same model parameters across different tasks and domains, allowing it to handle both vision-based tasks (such as object detection) and text-based tasks (like language understanding). The model demonstrates strong performance across seven tasks using eight datasets, with experiments showing a 87.5% reduction in the number of parameters compared to conventional task-specific models. The architecture also enables easy extension to more modalities, showcasing its flexibility in handling diverse input types and outputs. The use of transformers for both image and text encoders, with the inclusion of BERT for textual inputs and convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for image inputs, enables efficient and scalable multitasking.

In conclusion, UniT is a breakthrough in multitask learning, offering a unified solution that elegantly balances complexity and scalability across diverse tasks and modalities. By leveraging a shared transformer-based architecture, UniT demonstrates the potential of joint learning without sacrificing performance. What stands out most about this work is its efficient parameterization—reducing model size by 87.5%—while still excelling across both vision and language tasks. This approach could inspire future research on building highly versatile AI models that generalize well across domains, opening new possibilities for more robust and scalable AI systems in real-world applications. The ability to extend this model to additional modalities further enhances its relevance in advancing multimodal learning.

X-CLIP: In this paper X-CLIP [

27] author proposes a novel approach for video-text retrieval by introducing multi-grained contrastive learning. Unlike previous methods that primarily focus on either coarse-grained or fine-grained contrasts, X-CLIP handles both, as well as cross-grained contrasts. Specifically, the model aligns video and text representations at multiple levels: frame-word, video-sentence, sentence-frame, and video-word. This multi-grained approach allows X-CLIP to more effectively capture the semantic alignment between videos and their corresponding text descriptions.The X-CLIP framework utilizes the CLIP architecture’s powerful image-text retrieval capabilities and extends it to video-text tasks by implementing a more granular alignment of visual and textual data. It includes both frame-level and video-level representations, processed by temporal encoders, to better account for the temporal dynamics in video data. This results in improved performance across several benchmarks, outperforming state-of-the-art models, with significant gains on datasets like MSR-VTT, MSVD, and DiDeMo. The innovative contribution of this paper lies in its multi-grained contrastive learning mechanism, which integrates both fine and coarse levels of alignment, offering a more nuanced understanding of video-text relationships. This makes X-CLIP a strong advancement in the domain of video-text retrieval, demonstrating the potential for more accurate and scalable models. In conclusion, X-CLIP represents a significant advancement in video-text retrieval by introducing a multi-grained contrastive learning approach. Its ability to align video and text representations at various levels, such as frame-word and video-sentence, enables deeper semantic understanding, which is crucial for handling the complexity of video data. By building on the existing CLIP architecture and extending it to video, X-CLIP demonstrates impressive scalability and flexibility, making it a promising tool for real-world applications like video search, recommendation systems, and autonomous systems. Despite its high computational demands, the performance improvements across multiple benchmarks, such as MSR-VTT and MSVD, highlight X-CLIP’s superior ability to capture both visual and temporal information. As the need for more accurate and contextually aware video retrieval systems grows, X-CLIP paves the way for future innovations in the field of multimodal AI, offering an enhanced ability to understand and process sequential and complex video content.

CoCa : In the paper CoCa (Contrastive Captioner) [

9] framework presented in this paper by google proposes a unified approach that combines contrastive learning and caption generation for enhanced image-text understanding. The model is designed to handle both image-to-text and text-to-image tasks within a single architecture. CoCa incorporates two branches: a contrastive branch that aligns images with text descriptions and a generative branch that produces captions from visual inputs. By leveraging pre-training on large-scale datasets, CoCa achieves state-of-the-art performance across various vision-language benchmarks, including MSCOCO, Flickr30k, and NoCaps. The model’s architecture includes a dual-encoder structure for contrastive learning, along with an autoregressive decoder for caption generation. This combination allows CoCa to excel at tasks like image captioning, text-based image retrieval, and image-based text generation. The joint training of contrastive and generative tasks enhances CoCa’s ability to generalize to unseen data, offering a robust and scalable solution for multimodal tasks. Additionally, the paper demonstrates that CoCa significantly outperforms prior models on zero-shot transfer capabilities and general-purpose image-text tasks, making it a versatile tool for real-world applications such as search engines, recommendation systems, and automated content generation

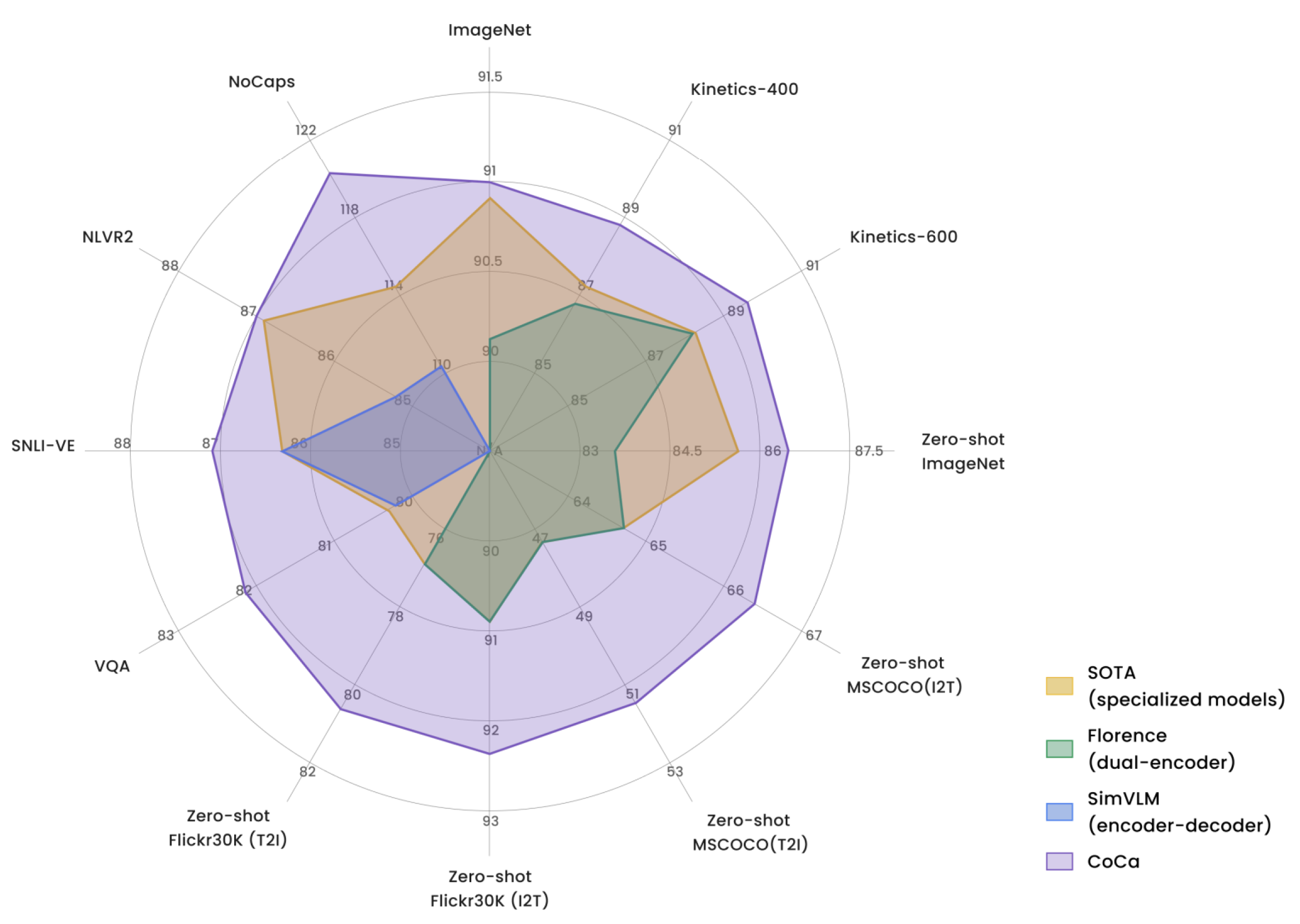

Figure 4.

This radar plot showcases the performance of CoCa, SimVLM, Florence, and state-of-the-art specialized models across a variety of datasets, including ImageNet, Kinetics-400, NoCaps, VQA, and NLVR2. CoCa demonstrates consistent and superior performance across vision-language tasks like image captioning, visual question answering, and video understanding, outperforming other models in both zero-shot and fine-tuned settings. (Fig. credit: [

9]).

Figure 4.

This radar plot showcases the performance of CoCa, SimVLM, Florence, and state-of-the-art specialized models across a variety of datasets, including ImageNet, Kinetics-400, NoCaps, VQA, and NLVR2. CoCa demonstrates consistent and superior performance across vision-language tasks like image captioning, visual question answering, and video understanding, outperforming other models in both zero-shot and fine-tuned settings. (Fig. credit: [

9]).

Figure 5.

These graphs illustrate the trade-offs between model size (number of parameters in millions) and ImageNet Top-1 Accuracy for various models. The left plot compares CoCa’s performance to other models such as Florence, ViT, and SwinV2, highlighting CoCa’s superior accuracy across different model sizes. The right plot further emphasizes CoCa’s efficiency by comparing it against models like CLIP, ALIGN, and LiT, where CoCa achieves higher accuracy with a relatively compact model size. (Fig. credit: [

9]).

Figure 5.

These graphs illustrate the trade-offs between model size (number of parameters in millions) and ImageNet Top-1 Accuracy for various models. The left plot compares CoCa’s performance to other models such as Florence, ViT, and SwinV2, highlighting CoCa’s superior accuracy across different model sizes. The right plot further emphasizes CoCa’s efficiency by comparing it against models like CLIP, ALIGN, and LiT, where CoCa achieves higher accuracy with a relatively compact model size. (Fig. credit: [

9]).

CoCa seamlessly integrates contrastive learning and generative tasks, offering a unified model capable of tackling a broad range of image-text tasks. You emphasize CoCa’s scalability and performance efficiency, noting that its ability to perform well on both small and large datasets, and across multiple modalities, marks it as a standout in the field. Moreover, CoCa’s capacity to outperform state-of-the-art models while using fewer parameters is a significant takeaway, setting a new benchmark for real-world applications in search, recommendation, and content generation.

Florence: Florence is a large-scale foundation model for computer vision introduced by Lu Yuan [

28] aiming to unify multiple visual tasks within a single architecture. Drawing inspiration from foundational models in natural language processing, Florence leverages a Vision Transformer (ViT) architecture and is trained on a massive dataset comprising billions of image-text pairs collected from the web. A key component of the model is its use of a contrastive learning objective that aligns visual and textual representations in a shared embedding space, enhancing its ability to understand and relate visual content to textual descriptions. Efficient training strategies, including distributed training across multiple GPUs and advanced optimization algorithms, enable the model to handle its scale effectively. Florence achieves state-of-the-art results on standard benchmarks like ImageNet for image classification and COCO for object detection and segmentation, demonstrates strong transfer learning capabilities with minimal fine-tuning, and excels in cross-modal tasks that require understanding the relationship between images and text. This work sets a new precedent for foundation models in computer vision by demonstrating that scaling up models and training data, combined with effective learning objectives, can lead to significant advancements in visual understanding across diverse tasks.

Figure 6.

Comparison of linear probing results for image classification on 11 datasets against existing state-of-the-art models, including SimCLRv2 (Chen et al., 2020c), ViT (Dosovitskiy et al., 2021a), EfficientNet (Xie et al., 2020), and CLIP [

4]. (Fig. credit: [

28]).

Figure 6.

Comparison of linear probing results for image classification on 11 datasets against existing state-of-the-art models, including SimCLRv2 (Chen et al., 2020c), ViT (Dosovitskiy et al., 2021a), EfficientNet (Xie et al., 2020), and CLIP [

4]. (Fig. credit: [

28]).

Florence represents a significant advancement in the field of computer vision, illustrating the profound impact of combining large-scale multimodal data with a unified architectural approach. By training on billions of image-text pairs and employing a contrastive learning objective to align visual and textual representations, Florence not only achieves state-of-the-art performance on traditional benchmarks but also excels in cross-modal tasks that bridge the gap between vision and language. This work underscores the potential of foundation models to generalize across diverse tasks, suggesting that the future of computer vision lies in scalable models that can learn rich, versatile representations from vast and varied datasets. The success of Florence paves the way for further exploration into even larger models and more integrated learning objectives, pointing toward a new era of AI systems capable of more holistic understanding and reasoning.

ALIGN: In the paper ALIGN [

29], author introduces a large-scale model that learns visual and vision-language representations by leveraging over one billion noisy image-text pairs collected from the web without manual filtering. Utilizing a dual-encoder architecture—with an image encoder (such as EfficientNet or Vision Transformer) and a text encoder (like BERT)—trained jointly using a contrastive learning objective, the model aligns images and their corresponding textual descriptions in a shared embedding space, enhancing its ability to understand and relate visual content to language. ALIGN achieves strong zero-shot performance on ImageNet and other classification benchmarks by mapping class labels or descriptions into the shared embedding space and matching them with image embeddings. It sets new state-of-the-art results in image-to-text and text-to-image retrieval tasks and shows significant improvements when fine-tuned on downstream applications, highlighting its effectiveness as a foundational model for various vision and language tasks. The success of ALIGN underscores the potential of utilizing large-scale, noisy web data to train powerful vision-language models, demonstrating that with appropriate training objectives and architectures, models can learn rich, generalizable representations without the need for costly manual annotation or curation. This work paves the way for future research to explore even larger datasets and more sophisticated architectures to further bridge the gap between vision and language understanding.

Figure 7.

Comparison of image-text retrieval results on the Flickr30K and MSCOCO datasets, evaluated in both zero-shot and fine-tuned settings. ALIGN is benchmarked against several state-of-the-art models, including ImageBERT (Qi et al., 2020), UNITER (Chen et al., 2020c), CLIP (Radford et al., 2021), GPO (Chen et al., 2020a), ERNIE-ViL (Yu et al., 2020), VILLA (Gan et al., 2020), and Oscar (Li et al., 2020). (Fig. credit: [

29]).

Figure 7.

Comparison of image-text retrieval results on the Flickr30K and MSCOCO datasets, evaluated in both zero-shot and fine-tuned settings. ALIGN is benchmarked against several state-of-the-art models, including ImageBERT (Qi et al., 2020), UNITER (Chen et al., 2020c), CLIP (Radford et al., 2021), GPO (Chen et al., 2020a), ERNIE-ViL (Yu et al., 2020), VILLA (Gan et al., 2020), and Oscar (Li et al., 2020). (Fig. credit: [

29]).

ALIGN marks a advancement in vision-language representation learning by effectively harnessing massive amounts of noisy, uncurated web data. By employing a dual-encoder architecture and a contrastive learning objective to align visual and textual modalities in a shared embedding space, the model demonstrates that large-scale noisy supervision can rival or even surpass models trained on smaller, curated datasets. This approach not only achieves state-of-the-art performance in zero-shot image classification and cross-modal retrieval tasks but also emphasizes the scalability and robustness of learning from real-world data. ALIGN’s success underscores the potential of leveraging vast, readily available web resources to train powerful AI models, suggesting a paradigm shift in how we approach data collection and model training in the field of computer vision and beyond.

5. Challenges and Future Directions

In this section, we discuss the key challenges currently being faced and explore potential future directions for addressing them.

Data Limitations and Ambiguity: One of the persistent challenges in training Vision-Language Models (VLMs) lies in the inherent limitations of real-world datasets. For instance, it is often difficult to find images paired with negative captions, which are essential for robust model evaluation. Furthermore, current benchmarks struggle to diagnose whether a model fails due to a lack of object recognition or an inability to comprehend relationships between recognized objects. Captions in these datasets, such as those from COCO, tend to be overly simplistic and may introduce biases or ambiguities, limiting the model’s understanding of complex visual scenes. This raises the need for more sophisticated datasets that provide richer, more varied captions, particularly those that challenge a model’s ability to grasp relational and contextual understanding.

Video-Based Challenges: Video data introduces an additional layer of complexity due to its temporal dimension, which requires models not only to recognize static objects but also to understand the motion, dynamics, and spatial-temporal relationships of objects and actions. Tasks like text-to-video retrieval, video question answering, and video generation are becoming core challenges in computer vision research. However, video data demands significantly higher storage, processing power, and GPU memory compared to images, due to the frame-by-frame nature of video processing. For instance, a 24 fps video necessitates 24 times the storage and computational power if treated as a sequence of static images, pushing VLMs to make trade-offs such as using compressed video formats or employing more efficient data processing techniques. A major hurdle in video-text pretraining is the scarcity of high-quality supervision for temporal relationships. Current datasets often describe the content of video scenes rather than actions or motions, causing video-based models to behave similarly to image-based models and neglect the temporal aspects. Models like CLIP trained on video data tend to exhibit noun biases, struggling to capture interactions and temporal dynamics in videos. Generating paired video-caption data that accurately reflects both static content and temporal dynamics is costly and complex, making it difficult to build robust video VLMs. Although video captioning models can generate more captions, they still require an initial, high-quality dataset for training. Another possible solution is training a video encoder solely on video data, as done in models like VideoPrism [

36], which reduces the reliance on imperfect captions but still requires massive computational resources.

Computational Complexity: Video data processing is inherently more resource-intensive than image processing due to the redundancy between consecutive frames [

37]. While images already contain redundant information, this redundancy is even more pronounced in videos, where successive frames are often very similar. This redundancy calls for more efficient training methods, such as frame sampling or masked modeling, which has shown promise in image-based VLMs. Processing high volumes of video data demands not only advanced compression techniques but also optimized architectures that can handle the temporal aspects without overwhelming computational resources.

Biases in Vision-Language Models: Another pressing challenge is addressing the biases that emerge during training, such as noun bias in video models [

38], where models prioritize object recognition over understanding interactions and actions. This bias limits the generalization capabilities of VLMs in real-world applications, especially for tasks requiring action recognition and complex reasoning. Developing methods to mitigate these biases, including better curation of training data and the use of multimodal attention mechanisms, remains a critical area of research.

Future research should focus on compressing video data, utilizing frame-sampling techniques, and developing lightweight architectures that handle video streams effectively. Masked training strategies, which have reduced redundancy in image models, could be employed for video models as well. Furthermore, existing benchmarks for VLMs often fail to account for the complexity of real-world vision-language tasks, necessitating the development of new evaluation methods that assess both object recognition and relational understanding. Balanced datasets, like Winoground [

39], can discourage unimodal shortcuts and encourage true multimodal understanding. Addressing model biases, such as noun bias in video-text models, will also be critical. Future efforts should focus on training models to recognize complex interactions, using balanced datasets, attention mechanisms, and regularization techniques to reduce biases. Finally, scaling generative AI for video remains a major challenge. Refining techniques like text-to-video generation [

40] and video question answering will be key to capturing the full range of temporal dynamics, and developing efficient generative models that handle video data without overwhelming computational resources is crucial for the future of multimodal AI.