Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

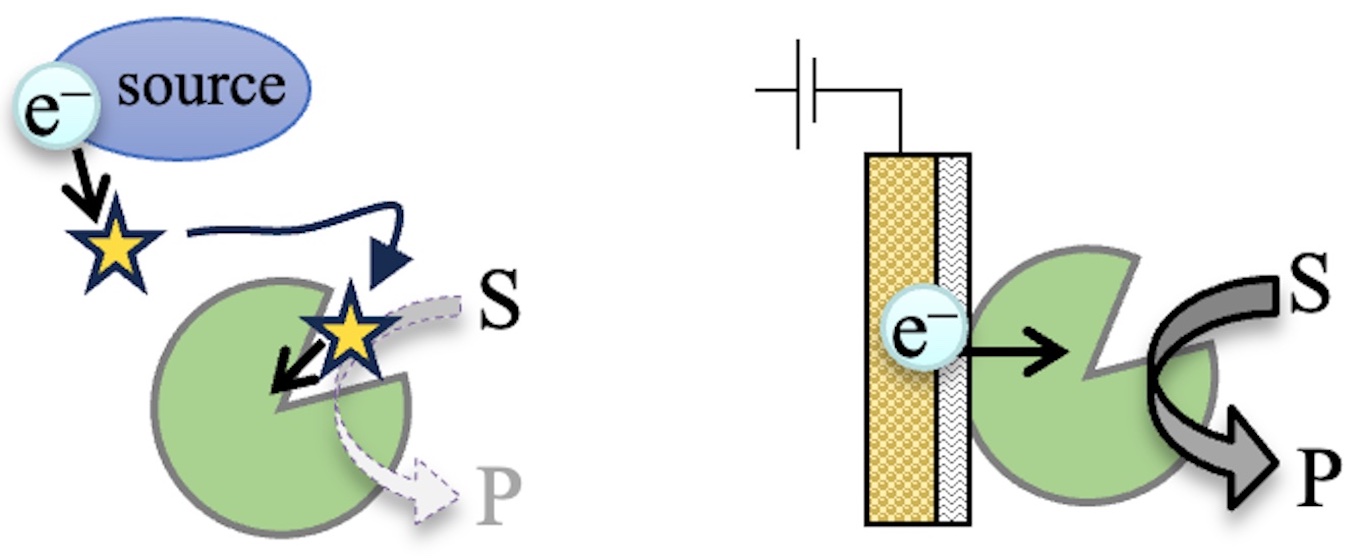

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

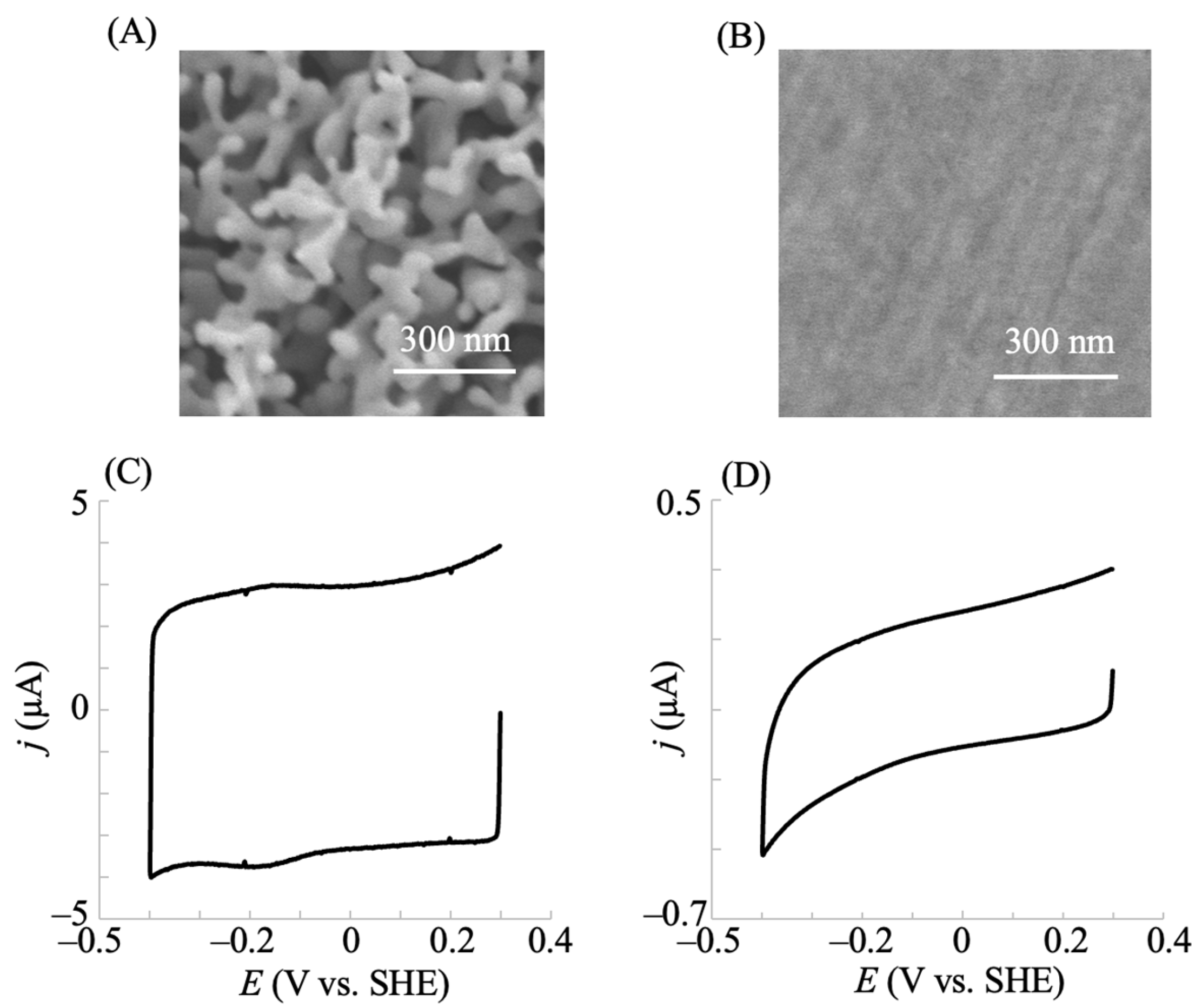

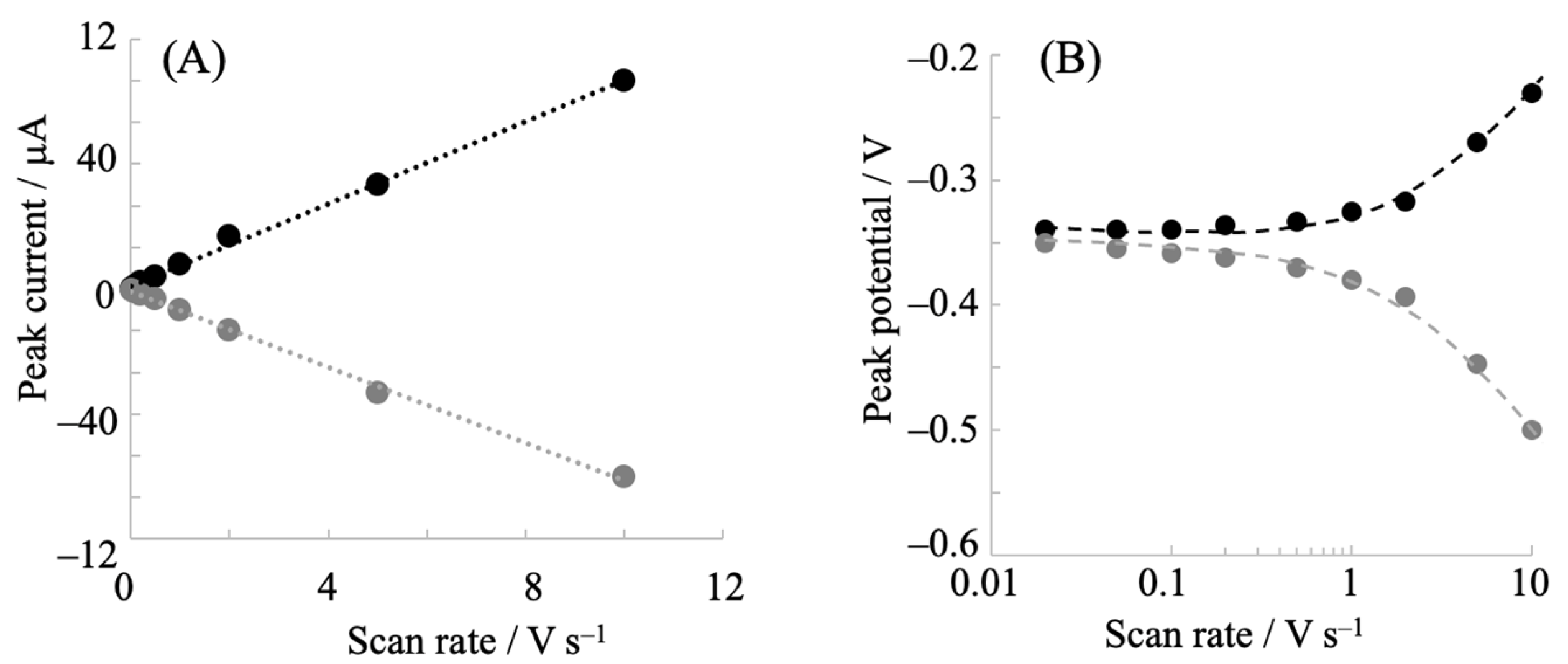

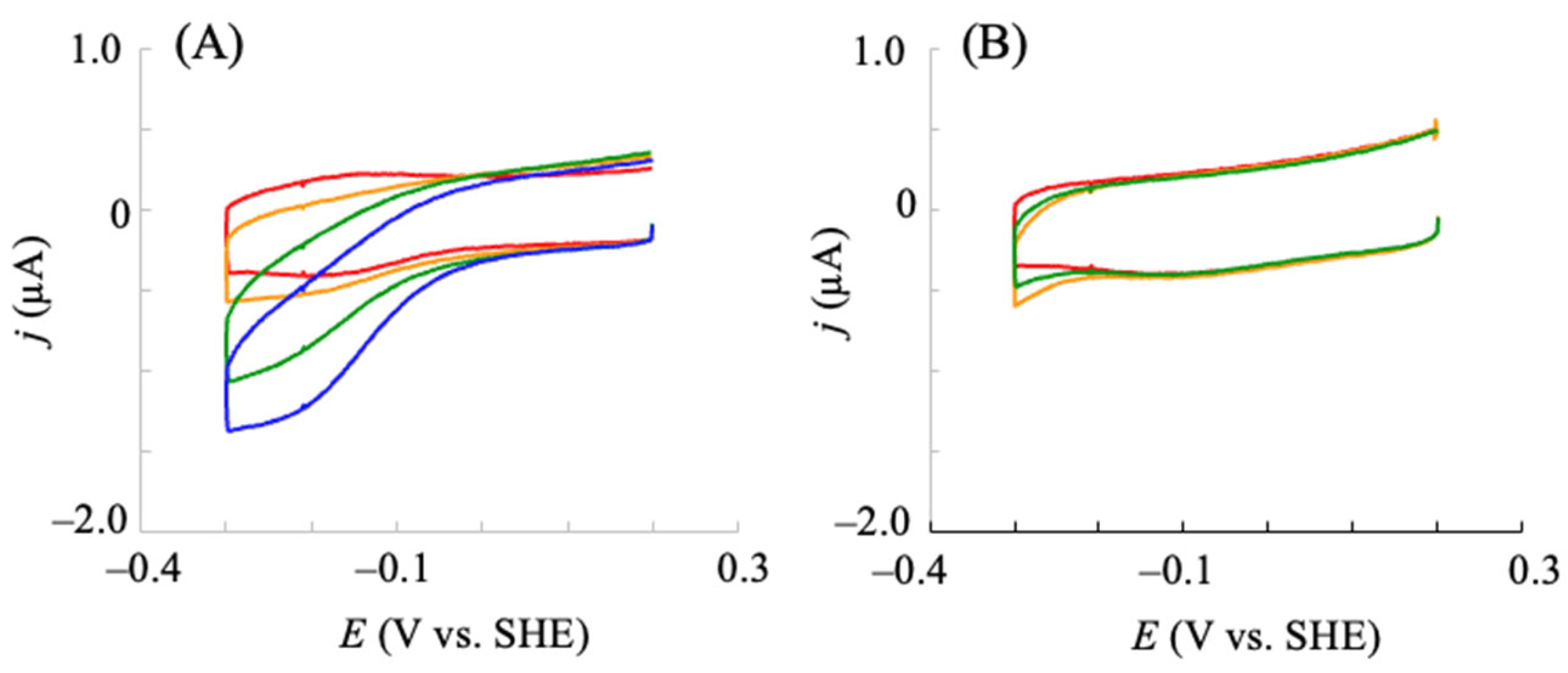

2.1. Electrochemical Redox Control of hIDO1 Using the NPG Electrode with Direct Electron Transfer

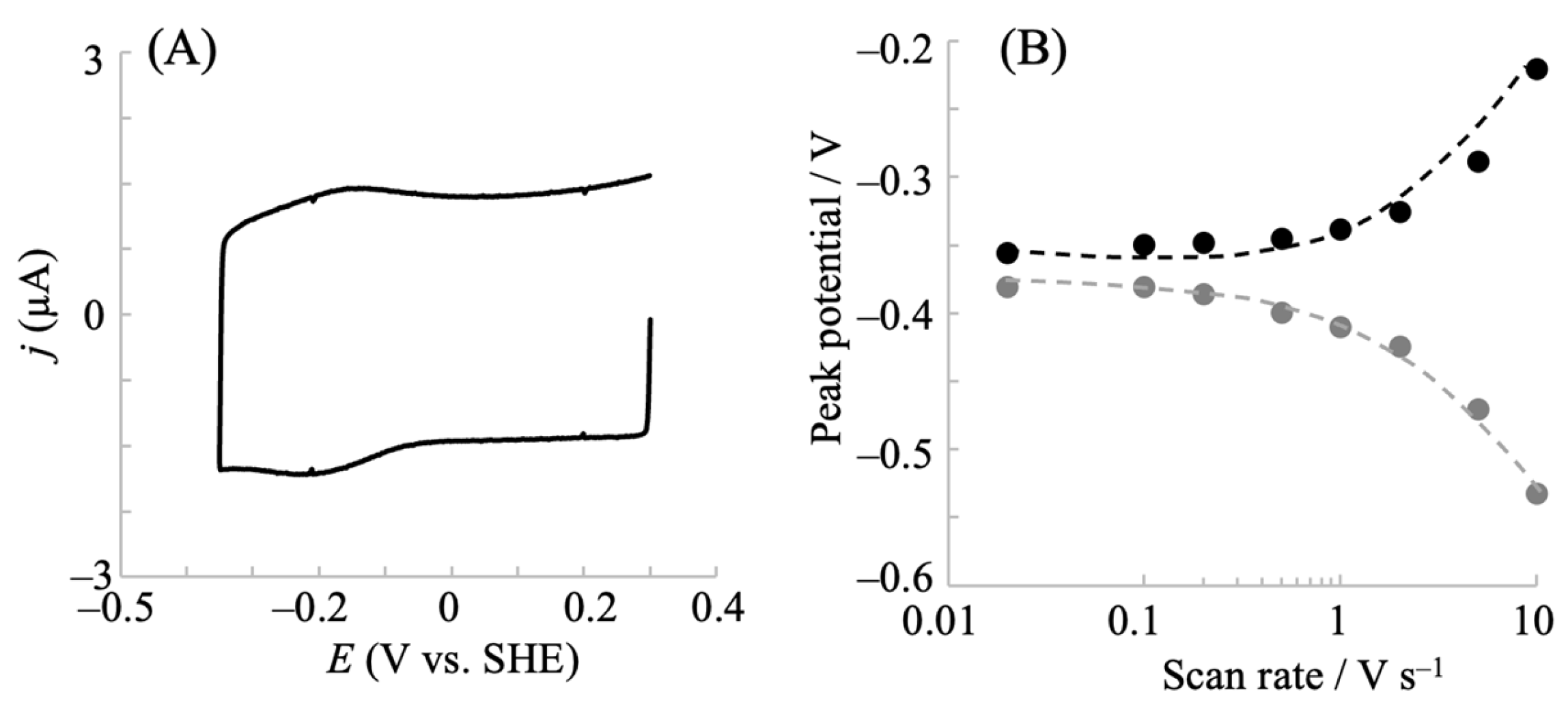

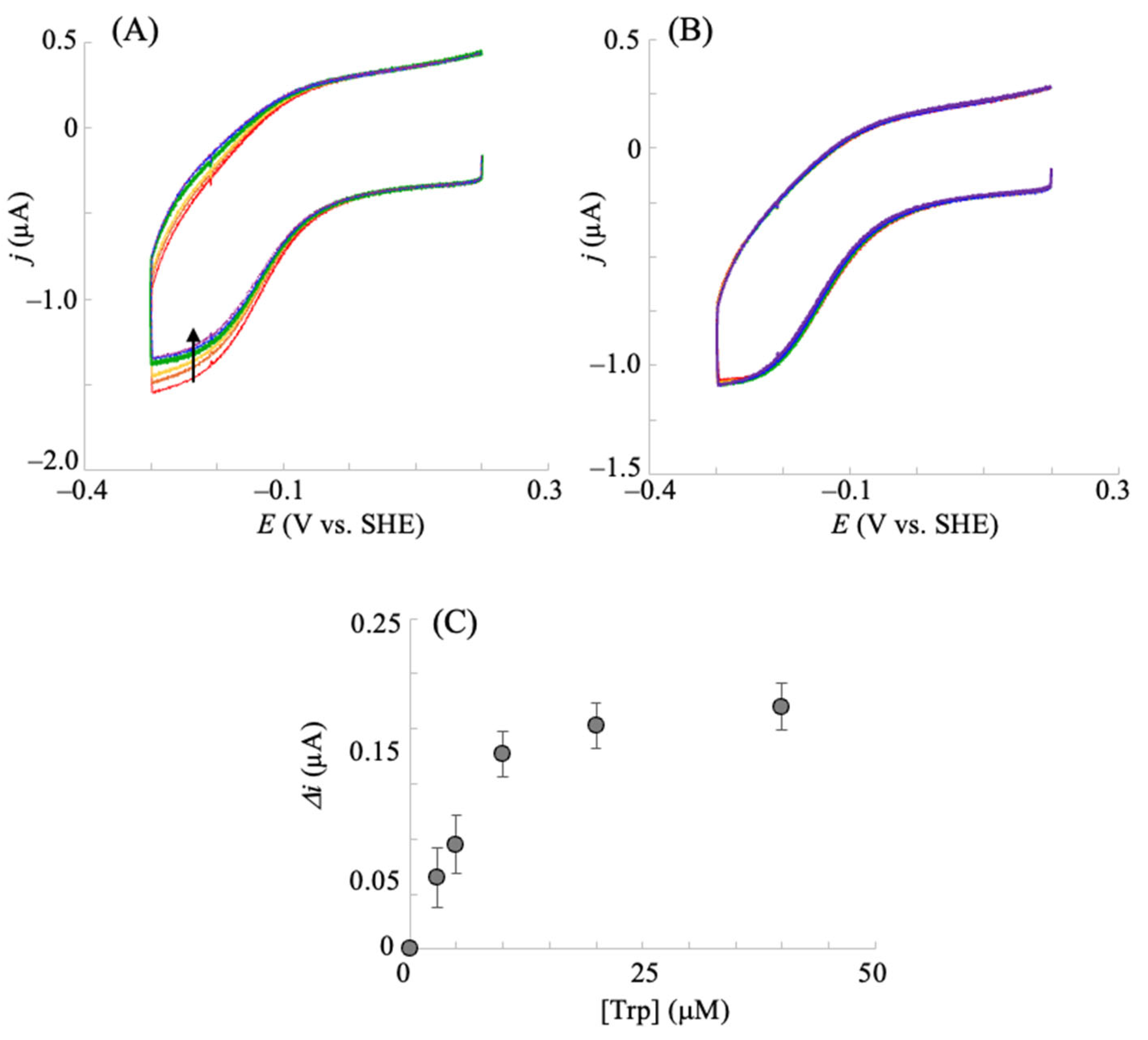

2.2. Electrocatalytic Reductive Reaction with hIDO in the Presence of Molecular Oxygen and Trp

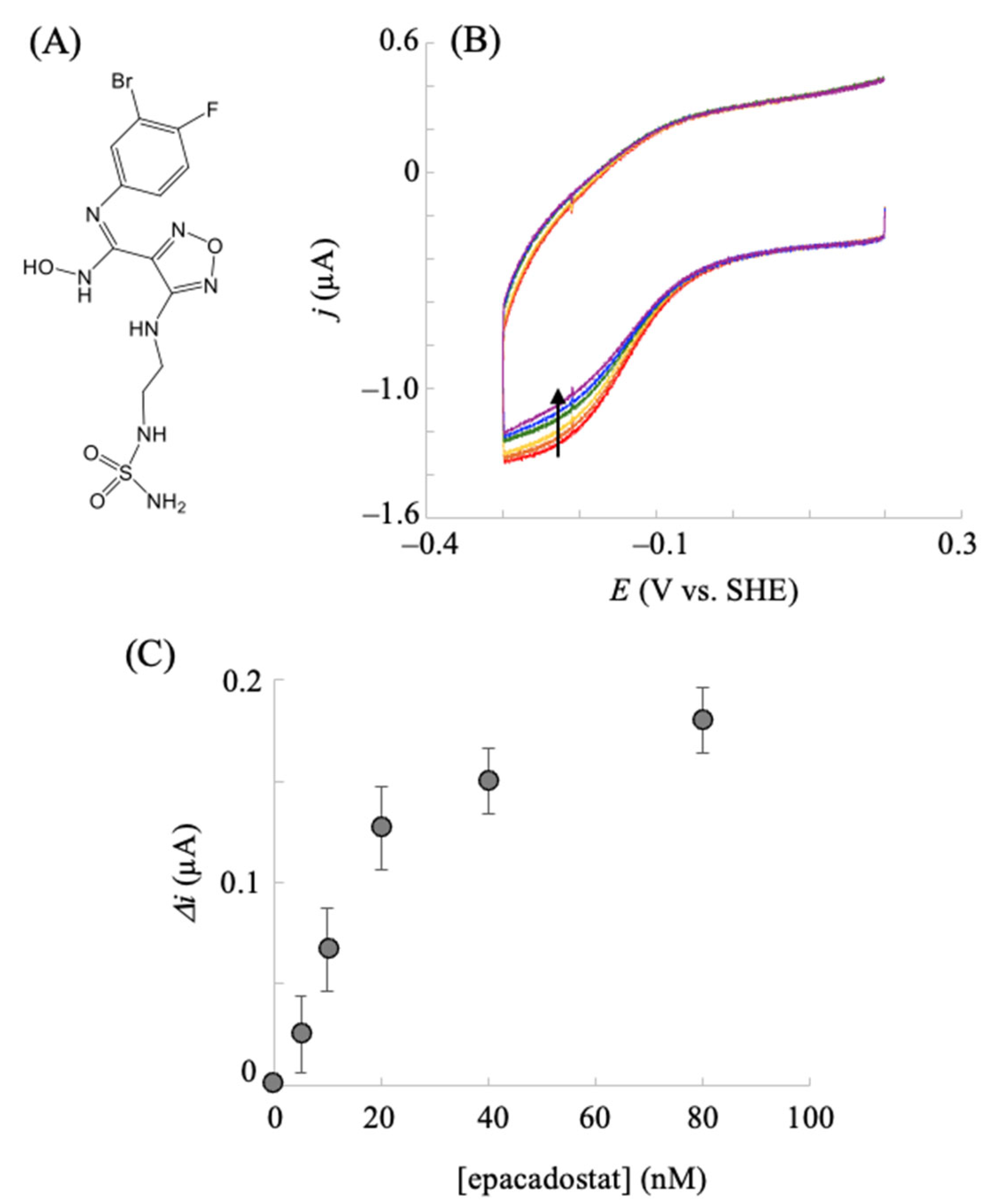

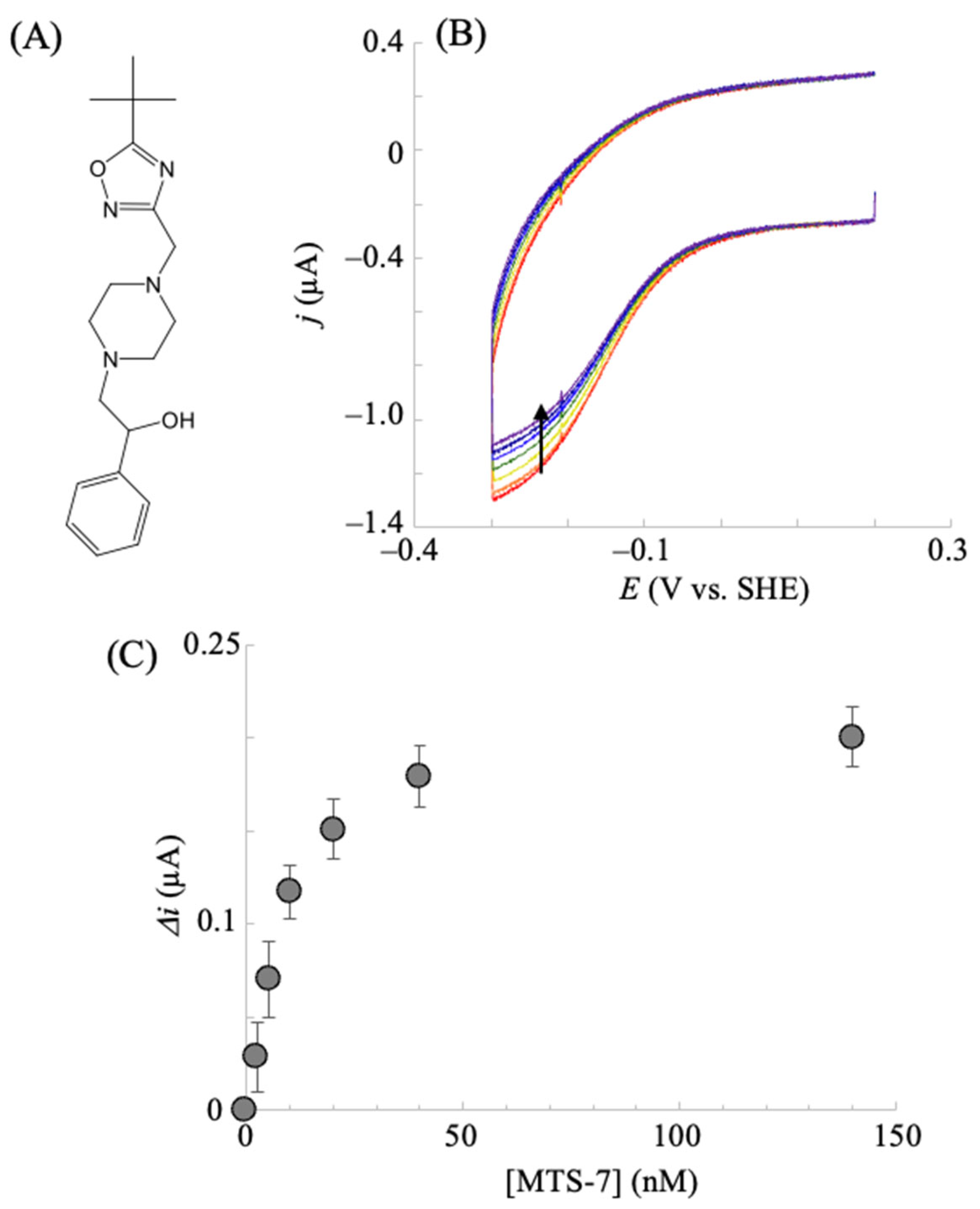

2.3. Electrochemical hIDO Inhibition Assay

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagents

3.2. Preparation of hIDO1 Enzymes

3.3. Fabrication of Nanostructured Electrode and hIDO1 Immobilization

3.4. Electrochemical Measurements and hIDO1 Assay

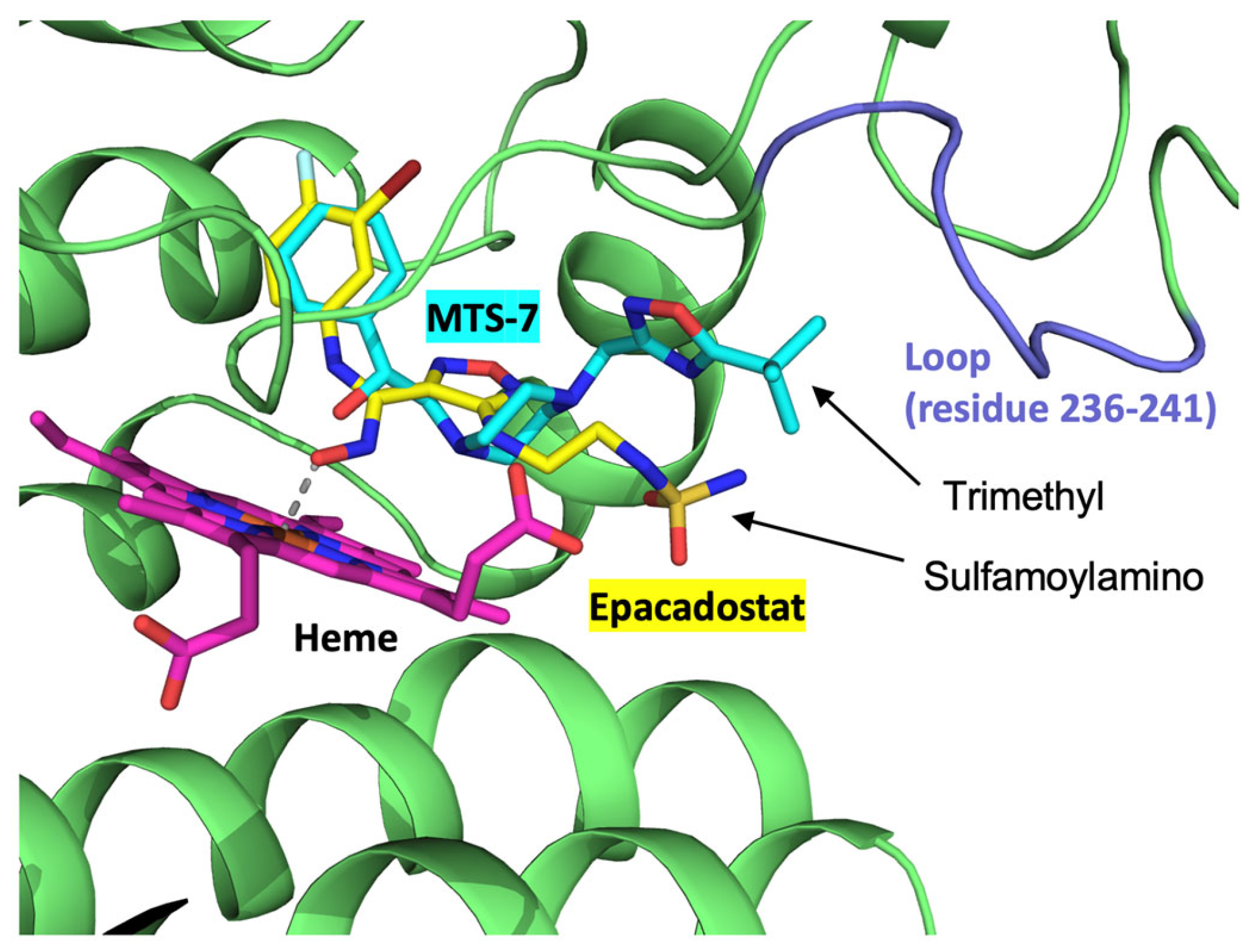

3.5. In Silico Study

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nelp, M.T.; Kates, P.A.; Hunt, J.T.; Newitt, J.A.; Balog, A.; Maley, D.; Zhu, X.; Abell, L.; Allentoff, A.; Borzilleri, R.; Lewis, H.A.; Lin, Z.; Seitz, S.P.; Yan, C.; Groves, J.T. Immune-modulating enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase is effectively inhibited by targeting its apo-form. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2018, 115, 3249–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis-Ballester, A.; Pham, K.N.; Batabyal, D.; Karkashon, S.; Bonanno, J.B.; Poulos, T.L.; Yeh, S.R. Structural insights into substrate and inhibitor binding sites in human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capece, L.; Lewis-Ballester, A.; Yeh, S.R.; Estrin, D.A.; Marti, M.A. Complete reaction mechanism of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase as revealed by QM/MM simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 1401–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, E.S.; Basran, J.; Lee, M.; Handa, S.; Raven, E.L. Substrate Oxidation by Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase: EVIDENCE FOR A COMMON REACTION MECHANISM. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 30924–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxenkrug, G. Serotonin - Kynurenine Hypothesis of Depression: Historical Overview and Recent Developments. Curr. Drug Targets 2013, 14, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, H.; Ozaki, N.; Sawada, M.; Isobe, K.; Ohta, T.; Nagatsu, T. A link between stress and depression: Shifts in the balance between the kynurenine and serotonin pathways of tryptophan metabolism and the etiology and pathophysiology of depression. Stress 2008, 11, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillemin, G.J.; Brew, B.J. Implications of the kynurenine pathway and quinolinic acid in Alzheimer's disease. Redox Rep. 2002, 7, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campesan, S.; Green, E.W.; Breda, C.; Sathyasaikumar, K.V.; Muchowski, P.J.; Schwarcz, R.; Kyriacou, C.P.; Giorgini, F. The Kynurenine Pathway Modulates Neurodegeneration in a Drosophila Model of Huntington's Disease. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyttenhove, C.; Pilotte, L.; Théate, I.; Stroobant, V.; Colau, D.; Parmentier, N.; Boon, T.; Van den Eynde, B.J. Evidence for a tumoral immune resistance mechanism based on tryptophan degradation by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 1269–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, G.C. CANCER Why tumours eat tryptophan. Nature 2011, 478, 192–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triplett, T.A.; Garrison, K.C.; Marshall, N.; Donkor, M.; Blazeck, J.; Lamb, C.; Qerqez, A.; Dekker, J.D.; Tanno, Y.; Lu, W.C.; Karamitros, C.S.; Ford, K.; Tan, B.; Zhang, X.M.; McGovern, K.; Coma, S.; Kumada, Y.; Yamany, M.S.; Sentandreu, E.; Fromm, G.; Tiziani, S.; Schreiber, T.H.; Manfredi, M.; Ehrlich, L.I. R.; Stone, E.; Georgiou, G. Reversal of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-mediated cancer immune suppression by systemic kynurenine depletion with a therapeutic enzyme. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Xu, W.; Liu, F.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, L.; Ding, Z.; Liang, H.; Song, J. The emerging roles of IDO2 in cancer and its potential as a therapeutic target. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 137, 111295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantouris, G.; Serys, M.; Yuasa, H.J.; Ball, H.J.; Mowat, C.G. Human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-2 has substrate specificity and inhibition characteristics distinct from those of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-1. Amino Acids 2014, 46, 2155–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efimov, I.; Basran, J.; Sun, X.; Chauhan, N.; Chapman, S.K.; Mowat, C.G.; Raven, E.L. The mechanism of substrate inhibition in human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 3034–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, J.; Wen, H.; Zhao, S.; Wang, L.; Qiao, H.; Shen, H.; Yu, Z.; Di, B.; Xu, L.; Hu, C. Displacement Induced Off-On Fluorescent Biosensor Targeting IDO1 Activity in Live Cells. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 14943–14950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sono, M. The Roles of Superoxide Anion and Methylene Blue in the Reductive Activation of Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase by Ascorbic Acid or by Xanthine Oxidase-Hypoxanthine. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 1616–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.R.; Terentis, A.C.; Cai, H.; Takikawa, O.; Levina, A.; Lay, P.A.; Freewan, M.; Stocker, R. Post-translational regulation of human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity by nitric oxide. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 23778–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, F.; Ohnishi, T.; Hayaishi, O. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Characterization and properties of enzyme. O2- complex. J. Biol. Chem. 4637. [Google Scholar]

- Yuasa, H.J.; Stocker, R. Methylene blue and ascorbate interfere with the accurate determination of the kinetic properties of IDO2. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 4892–4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, F.A.; Cheng, B.; Herold, R.A.; Megarity, C.F.; Siritanaratkul, B. From Protein Film Electrochemistry to Nanoconfined Enzyme Cascades and the Electrochemical Leaf. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 5421–5458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, L.B. F.; Sudmeier, T.; Landis, M.A.; Allen, C.S.; Vincent, K.A. Controlled Biocatalytic Synthesis of a Metal Nanoparticle-Enzyme Hybrid: Demonstration for Catalytic H2-driven NADH Recycling. Angew. Chem.-Int. Edit. 2024, 63, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, T.; Kitazumi, Y.; Shirai, O.; Kano, K. Direct Electron Transfer-Type Bioelectrocatalysis of Redox Enzymes at Nanostructured Electrodes. Catalysts 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayikpoe, R.; Ngendahimana, T.; Langton, M.; Bonitatibus, S.; Walker, L.M.; Eaton, S.S.; Eaton, G.R.; Pandelia, M.E.; Elliott, S.J.; Latham, J.A. Spectroscopic and Electrochemical Characterization of the Mycofactocin Biosynthetic Protein, MftC, Provides Insight into Its Redox Flipping Mechanism. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 940–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenner, L.P.; Butt, J.N. Electrochemistry of surface-confined enzymes: Inspiration, insight and opportunity for sustainable biotechnology. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2018, 8, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, J.H. T.; Glennon, J.D.; Gedanken, A.; Vashist, S.K. Achievement and assessment of direct electron transfer of glucose oxidase in electrochemical biosensing using carbon nanotubes, graphene, and their nanocomposites. Microchim. Acta 2017, 184, 369–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, J.K.; Neupane, D.; Nepal, B.; Mikhaylov, V.; Demchenko, A.V.; Stine, K.J. Preparation, Modification, Characterization, and Biosensing Application of Nanoporous Gold Using Electrochemical Techniques. Nanomaterials 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.J.; Xu, H.T.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y. Correlation of the structure and applications of dealloyed nanoporous metals in catalysis and energy conversion/storage. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mie, Y.; Takayama, H.; Hirano, Y. Facile control of surface crystallographic orientation of anodized nanoporous gold catalyst and its application for highly efficient hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Catal. 2020, 389, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mie, Y.; Ikegami, M.; Komatsu, Y. Nanoporous Structure of Gold Electrode Fabricated by Anodization and Its Efficacy for Direct Electrochemistry of Human Cytochrome P450. Chem. Lett. 2016, 45, 640–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mie, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Itoga, Y.; Sueyoshi, K.; Tsujino, H.; Yamashita, T.; Uno, T. Nanoporous gold based electrodes for electrochemical studies of human neuroglobin. Electrochem. Commun. 2020, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mie, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Torii, R.; Jingkai, S.; Tanaka, T.; Sueyoshi, K.; Tsujino, H.; Yamashita, T. Redox State Control of Human Cytoglobin by Direct Electrochemical Method to Investigate Its Function in Molecular Basis. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 68, 806–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, N.; Basran, J.; Efimov, I.; Svistunenko, D.A.; Seward, H.E.; Moody, P.C. E.; Raven, E.L. The role of serine 167 in human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase: A comparison with tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 4761–4769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onuoha, A.C.; Rusling, J.F. ELECTROACTIVE MYOGLOBIN-SURFACTANT FILMS IN A BICONTINUOUS MICROEMULSION. Langmuir 1995, 11, 3296–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, Y.; Takeuchi, R.; Kitazumi, Y.; Shirai, O.; Kano, K. Significance of Mesoporous Electrodes for Noncatalytic Faradaic Process of Randomly Oriented Redox Proteins. J. Phy.l Chem. C 2016, 120, 26270–26277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.L.; Lu, G.X.; Yang, B.J. Myoglobin/sol-gel film modified electrode: Direct electrochemistry and electrochemical catalysis. Langmuir 2004, 20, 1342–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-M.; Tseng, C.-C. Comparison of the direct electrochemistry of myoglobin and hemoglobin films and their bioelectrocatalytic properties. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2005, 575, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Li, Y.; Bai, Y.; Sun, C. Hydrogen peroxide biosensor based on myoglobin/colloidal gold nanoparticles immobilized on glassy carbon electrode by a Nafion film. Sens. Actuat. B: Chem. 2006, 115, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolawole, A.O.; Hixon, B.P.; Dameron, L.S.; Chrisman, I.M.; Smirnov, V.V. Catalytic activity of human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (hIDO1) at low oxygen. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2015, 570, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.; Ladomersky, E.; Bell, A.; Dussold, C.; Cardoza, K.; Qian, J.; Lauing, K.L.; Wainwright, D.A. Quantification of IDO1 enzyme activity in normal and malignant tissues. Methods Enzymol. 2019, 629, 235–256. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Shin, N.; Koblish, H.K.; Yang, G.; Wang, Q.; Wang, K.; Leffet, L.; Hansbury, M.J.; Thomas, B.; Rupar, M.; Waeltz, P.; Bowman, K.J.; Polam, P.; Sparks, R.B.; Yue, E.W.; Li, Y.; Wynn, R.; Fridman, J.S.; Burn, T.C.; Combs, A.P.; Newton, R.C.; Scherle, P.A. Selective inhibition of IDO1 effectively regulates mediators of antitumor immunity. Blood 2010, 115, 3520–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, J.T.; Siu, S.; Meininger, D.P.; Wienkers, L.C.; Rock, D.A. In vitro modulation of cytochrome P450 reductase supported indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity by allosteric effectors cytochrome b(5) and methylene blue. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 2647–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, E.W.; Douty, B.; Wayland, B.; Bower, M.; Liu, X.; Leffet, L.; Wang, Q.; Bowman, K.J.; Hansbury, M.J.; Liu, C.; Wei, M.; Li, Y.; Wynn, R.; Burn, T.C.; Koblish, H.K.; Fridman, J.S.; Metcalf, B.; Scherle, P.A.; Combs, A.P. Discovery of potent competitive inhibitors of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase with in vivo pharmacodynamic activity and efficacy in a mouse melanoma model. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 7364–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsujino, H.; Uno, T.; Yamashita, T.; Katsuda, M.; Takada, K.; Saiki, T.; Maeda, S.; Takagi, A.; Masuda, S.; Kawano, Y.; Meguro, K.; Akai, S. Correlation of indoleamine-2,3-dioxigenase 1 inhibitory activity of 4,6-disubstituted indazole derivatives and their heme binding affinity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 29, 126607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukaszewski, M.; Soszko, M.; Czerwinski, A. Electrochemical Methods of Real Surface Area Determination of Noble Metal Electrodes - an Overview. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2016, 11, 4442–4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trashin, S.; de Jong, M.; Meynen, V.; Dewilde, S.; De Wael, K. Attaching Redox Proteins onto Electrode Surfaces by using bis-Silane. ChemElectroChem 2016, 3, 1035–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukunishi, Y.; Mikami, Y.; Kubota, S.; Nakamura, H. Multiple target screening method for robust and accurate in silico ligand screening. J. Mol. Graph. 2006, 25, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukunishi, Y.; Mikami, Y.; Takedomi, K.; Yamanouchi, M.; Shima, H.; Nakamura, H. Classification of chemical compounds by protein-compound docking for use in designing a focused library. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. Software News and Update AutoDock Vina: Improving the Speed and Accuracy of Docking with a New Scoring Function, Efficient Optimization, and Multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated Docking with Selective Receptor Flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).