Background. Atherosclerosis is a chronic and progressive condition of the arteries, characterized by the thickening and hardening of their walls due to the formation of atherosclerotic plaques. Low-grade inflammation is implicated in the pathogeny of atherosclerosis. Chronic apical periodontitis (CAP), the chronic inflammation around the root apex of infected teeth, is associated with a low-grade inflammatory state, so a connection between atherosclerosis and CAP have been suggested. The aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review with meta-analysis to answer the following PICO question: In adult patients, does the presence or absence of atherosclerosis affect the prevalence of CAP? Methods. The PRISMA guidelines were followed to carry out this systematic review. A bibliographic search was performed in PubMed-MEDLINE, Embase, and Scielo. Inclusion criteria selected the studies presenting data on the prevalence of CAP in patients diagnosed with atherosclerosis and control patients. The statistical analysis was carried out using RevMan software. Study characteristics and risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were extracted. Random-effects meta-analyses were performed. Risk of bias was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale, adapted for cross-sectional studies. To estimate variance and heterogeneity between trials, the Higgins I2 test was used. The quality of the evidence was evaluated using GRADE. Results. The search strategy recovered 102 articles, and only five met the inclusion criteria. Meta-analysis showed and overall OR = 2.94 (95% CI = 1.83 – 4.74; p < 0.01) for the prevalence of CAP among patients with atherosclerosis. The overall risk of bias was moderate. The quality of the evidence showed a low level of certainty. Conclusions. Patients with atherosclerosis are almost three times more likely to have CAP. This finding supports the hypothesis that chronic inflammatory processes in the oral cavity could significantly impact cardiovascular health, emphasizing the importance of an integrated approach to oral and systemic health care. This result should be translated to daily clinical practice: the healthcare community should be aware of this association and suspect atherosclerotic pathology in patients who show a high prevalence of CAP. Likewise, patients with atherosclerosis should be monitored in the dental clinic for CAP.

1. Introduction

Apical periodontitis is an inflammation of the tissues surrounding the apex of the tooth, caused by the immune reaction triggered by bacterial antigens passing from the infected root canal [

1]. The estimated prevalence of apical periodontitis is around 52% [

2]. Periapical chronic inflammation, called chronic apical periodontitis (CAP), causes destruction of the periapical bone, which is evident on X-rays as a radiolucent image around the apex of the affected tooth [

3].

Atherosclerosis is a chronic and progressive condition of the arteries, characterized by the thickening and hardening of their walls due to the most common formation of atheromatous plaques [

4]. These plaques are accumulations of lipids, cholesterol, calcium, and other substances that deposit in the innermost layer of the arteries, known as the intima, which is in contact with the blood and lined with endothelial cells [

5]. Atheromatous plaques can restrict blood flow or even completely obstruct an artery, leading to severe cardiovascular problems such as myocardial infarctions or strokes [

4]. Atherosclerosis can be characterized as an independent form of inflammation, sharing similarities but also having fundamental differences from low-grade inflammation and various variants of canonical inflammation [

6]. There are numerous factors that act as inducers of the inflammatory process in atherosclerosis, including vascular endothelium aging, metabolic dysfunctions, autoimmune, and in some cases, infectious damage factors [

4,

6]. Low-grade chronic inflammation can lead to vascular inflammation and endothelial dysfunction, which can subsequently lead to atherosclerosis [

6]. Oral inflammatory processes, such as periodontal disease [

7] and chronic apical periodontitis [

8], are associated to low-grade inflammation [

9]. For this reason, studies have been conducted investigating the possible association of periodontal disease [

10] and chronic apical periodontitis [

11] with atherosclerosis. Early endothelial dysfunction has been found in young men with apical periodontitis compared to healthy control patients [

12]. Some studies have found a relationship between CAP and cardiovascular diseases associated with atherosclerosis, such as myocardial infarction [

13], hypertension [

14] or stroke [

15]. Additionally, some experimental studies carried out in animals have found that CAP exacerbates atherosclerosis [

16,

17].

This study aimed to conduct a systematic review with meta-analysis to investigate the possible association between atherosclerosis and the prevalence of CAP. The null hypothesis was that the prevalence of CAP in patients with atherosclerosis is similar to that of the healthy general population.

2. Materials and Methods

To conduct this systematic review the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [

18,

19] were followed.

2.1. Review Question

The review focused on answering the following research question, structured according to PICO method (population, intervention, comparison, and outcome): In adult patients (P), does the presence of atherosclerosis (I) compared to its absence (C), affect the prevalence of CAP?

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria established were: (a) epidemiological studies published until December 2024; (b) studies comparing atherosclerotic patients with healthy control subjects; (c) studies diagnosing the atherosclerotic condition clinically or by imaging techniques; and (d) studies assessing the prevalence of AP, both in atherosclerotic patients and in control healthy subjects, using radiological methods.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) In vitro or animal studies, (b) case series, (c) studies reporting data only from atherosclerotic patients, (d) studies not reporting the radiological prevalence of CAP, (e) studies including patients with atherosclerosis in the same experimental group as patients with other pathologies, without differentiating the data obtained in each pathology, and (f) studies that had been no initial agreement among the reviewers were excluded.

2.3. Search Strategy and Information Sources

Once the PICO question and inclusion criteria were established, the search strategy was designed. A bibliographic search was conducted with no time or language limits in PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science, Scopus, EMBASE, and SCIELO. For the electronic search strategy, terms from the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) and text words (tw) were combined as follows:

("arteriosclerosis"[All Fields] OR "coronary artery disease"[All Fields] OR "atherosclerosis"[All Fields] OR "arterial disease"[All Fields] OR "atherosclerotic plaque"[All Fields]) AND ("periapical pathology"[All Fields] OR "apical periodontitis"[All Fields] OR "periapical infection"[All Fields] OR "endodontics"[All Fields] OR "periapical disease"[All Fields]). A complementary screening was performed by searching for any additional studies through the references of the included studies that did not appear in the database search. A search was conducted in the grey literature, but it did not provide useful data (

https://opengrey.eu/; https://scholar.google.com/;

https://www.greynet.org/).

The selection of the articles was done by three authors individually (J.J.S-E, M.L-L., and D.C-B.) reading the titles and abstracts, or full text if further clarification was necessary. A second stage involved reading the full texts of all selected articles to definitively assess whether or not they met the inclusion criteria. Disagreements on eligibility were resolved by discussion and consensus.

2.4. Data Extraction

One of the authors (M.L-L.) was responsible for data extraction, while three reviewers (J.M-G., D.C-B and J.J.S-E) verified the tabulated data to ensure the absence of typo errors and carried out the analysis of the articles; the articles in disagreement were discussed. For each study, the following data were extracted: authors and year of publication, study design, the total sample size and that of the control and experimental groups, main variables, methods used to diagnose CAP and to detect atherosclerosis, and main results, including the number of control and atherosclerotic patients with and without CAP.

2.5. Data Synthesis and Analysis

The outcome variable studied was the prevalence of CAP, calculated as the percentage of individuals with at least one tooth affected by CAP. In each selected study, the odds ratio (OR) was calculated with its 95% confidence interval (CI), aiming to measure the effect of the relationship between atherosclerosis and the prevalence of CAP.

To determine the overall OR and its 95% CI for the prevalence of AP, a random-effects meta-analysis was performed using the RevMan software (Review Manager Web. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2019) software version 5.4. To estimate the variance and heterogeneity of the studies, the Tau

2 and the Higgins I

2 test were used, considering slight heterogeneity if it ranged from 25% to 50%, moderate from 50% to 75%, and high if the heterogeneity was greater than 75% [

20]. The level of significance was applied to p = 0.05.

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

The methodological risk of bias of the selected articles was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale [

21], adapted for cross-sectional studies [

22]. This scale was adapted to the outcome of interest, classifying the items into two domains: sample selection and outcome. They were given points (*) depending on the aspect required were present or missing. Three authors (M.L-L., D.C-B., and J.J.S-E.) independently assessed the risk of bias of each of the included studies. In case of disagreement, the authors discussed until they reached an agreement. Two domains, sample selection, and outcome, were considered. The evaluation of each item was made according to the following criteria:

A) Domain “Sample selection” (maximum: six points):

1) Representativeness of the sample: Truly representative of the average in the target population (random sampling) ➔ three points; Somewhat representative of the average in the target population (non-random sampling) ➔ two points; Selected group of users ➔ one point; No description of the sampling strategy ➔ no points.

2). Sample size: Justified, the study provided sample size calculation, or the entire population was recruited (and the loss rate was ≤20%) ➔ one point; Not justified size no points.

3). Atherosclerotic condition: The atherosclerotic condition was verified by imaging techniques ➔ two points; Atherosclerotic condition was established only clinically ➔ one point; The condition of atherosclerosis was not established either clinically or by imaging methods ➔ no points.

B) Domain “Outcome” (maximum: six points):

1) Assessment of the outcome: Training and calibration for the methodology of assessing radiographically periapical lesions with inter- and intra-agreement values provided ➔ two points; Training and calibration for the methodology of assessing radiographically periapical lesions, with inter- or intra-agreement values not provided ➔ one point; Training and calibration not mentioned ➔ no points.

2) Type of radiographs used: Computed tomography or periapical radiographs → two points; Panoramic radiographs → one point; the type of radiography used is not specified → no points.

3) Inclusion of third molar in the total sample of teeth: Third molar included ➔ one point. If the study did not mention that third molar was excluded, it got one point in this domain; third molar not included ➔ no points.

4) Number of observers: Radiographs were studied by two or more examiners ➔ one point; only one examiner studied the radiographs ➔ no points.

The maximum possible score was 12 points. High risk of bias was defined as 0 to 4 points, moderate risk of bias was considered for the studies scoring 5 to 8 points, and finally low risk of bias was assigned to studies scoring between 9 and 12 points.

Articles were assessed independently by 4 reviewers (J.J.S-E., D.C-B., M.L-L., J.J.S-M.), and cases of disagreements in the risk of bias were discussed until a consensus was achieved.

2.7. Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

The GRADE tool was used to assess the overall quality and certainty of the evidence (Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) [

23]. Four investigators (M.L-L. J.J.S-E., B.S-D., and J.J.S-M.) independently carried out the assessment. This procedure defines an initial level of certainty according to the design of the included studies and, subsequently, analyzes different domains such as the risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, publication bias, dose-response gradient, confounding factors, or the magnitude of the effect to conclude at a final level of certainty. Having a high or moderate level of evidence, if it was highly likely or possible that the true effect was close to the estimated conclusion, allowing a recommendation to be made. A low or very low level of evidence indicates that confidence in the result is limited or very weak, respectively [

24].

3. Results

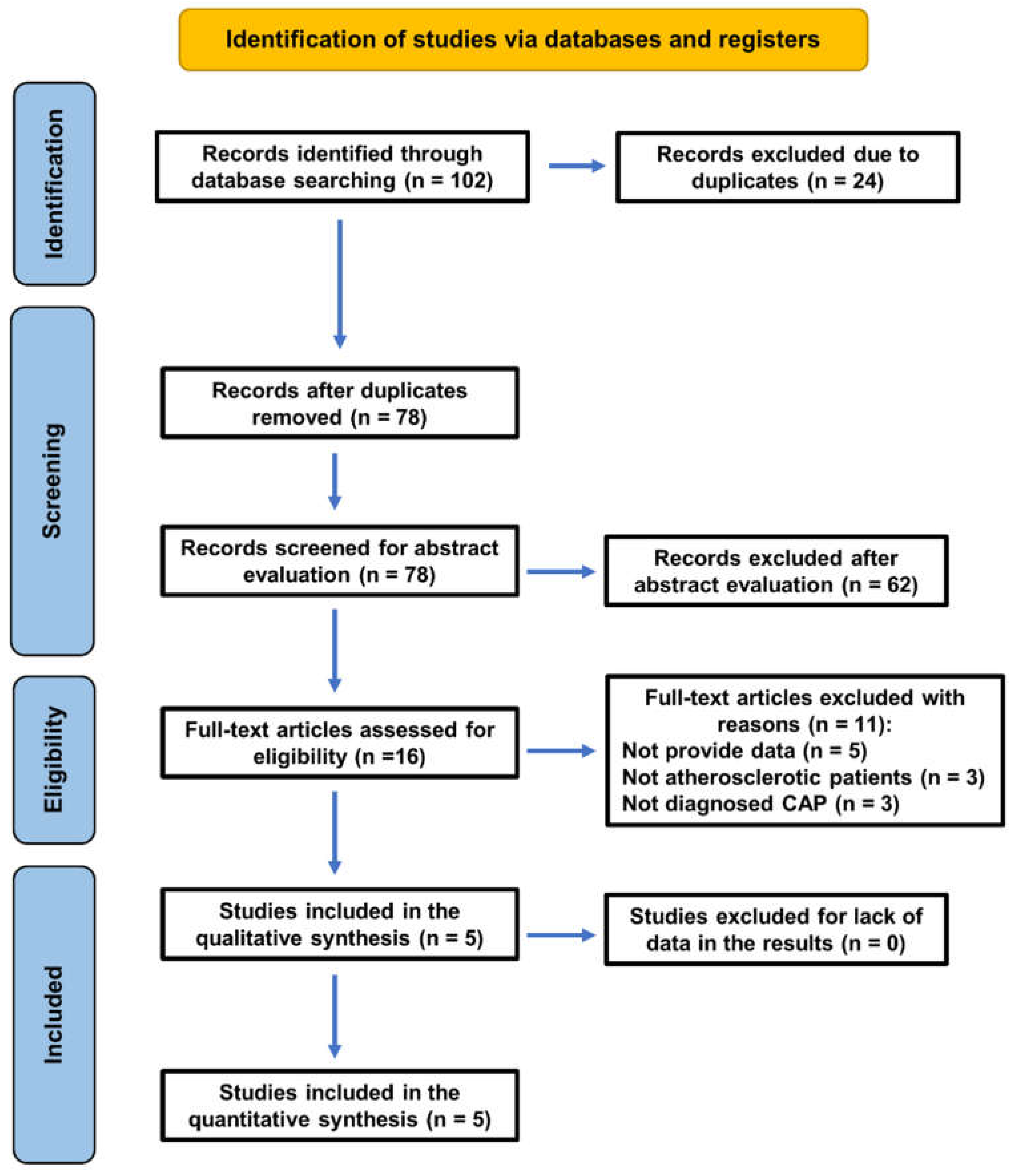

The search strategy to select the articles that have been included in this systematic review has followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, as shown in the flowchart (

Figure 1).

The baseline search recovered 102 titles. After the removal of duplicates, 78 articles remained, of which 62 were excluded after reading abstract for being unrelated to the topic, and 16 were selected for full text. After full-text reading, 11 articles were excluded for the following reasons: five did not provide the necessary data [11,12, 25–27], in three studies some patients in the experimental group did not have atherosclerosis [

28,

29,

30], and other three studies did not establish the radiographic diagnosis of CAP [

31,

32,

33]. The excluded articles and the reasons for their exclusion are shown in

Table 1.

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

Finally, five studies were selected and included for systematic review and meta-analysis (

Table 2).

The studies [13, 34–37] analyzed the association between atherosclerosis and the prevalence of CAP, diagnosed radiographically. For each study, the study design, included subjects, variable analyzed, diagnostic methods, and main results are summarized in

Table 2. Four of the included studies were cross-sectional [

34,

35,

36,

37], with level 4 of evidence according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine [

38], and one was retrospective studies [

13], with level 3 of evidence. Regarding the diagnosis of CAP, three of the included studies used panoramic radiographs to identify teeth with apical pathology [

13,

36,

37], one study used periapical radiographs [

35], and another study used a whole-body CT scan [

34] (

Table 2).

Concerning the atherosclerotic condition of patients in the atherosclerosis group, two studies included patients who had suffered cardiovascular events (CVE) associated with atherosclerosis [13, 36]. Other study one used CT scan [

34], and another one used coronary angiography [

35]. Finally, other study used Doppler sound to assess carotid wall thickness [

37].

An evidence table was elaborated with data from the included studies (

Table 3). The number of patients with at least one tooth with CAP in both the control and the atherosclerotic groups were the key data extracted in each of the studies. Then, the prevalence of CAP in patients with atherosclerosis and in healthy control subjects was calculated, as well as the corresponding OR for each study and for the overall sample.

The five studies included a total of 1,108 people, 515 atherosclerotic patients and 593 control healthy subjects. Patients with atherosclerosis showed a CAP prevalence of 65.4%, much higher than that found in the control group (38.8%). Data from four of the five studies [

34,

35,

36,

37] provided significant OR values greater than 1 (1.65-3.09), indicating association between atherosclerosis and periapical status. One of the studies [

13] did not provide a significant OR (1.65; p = 0.126).

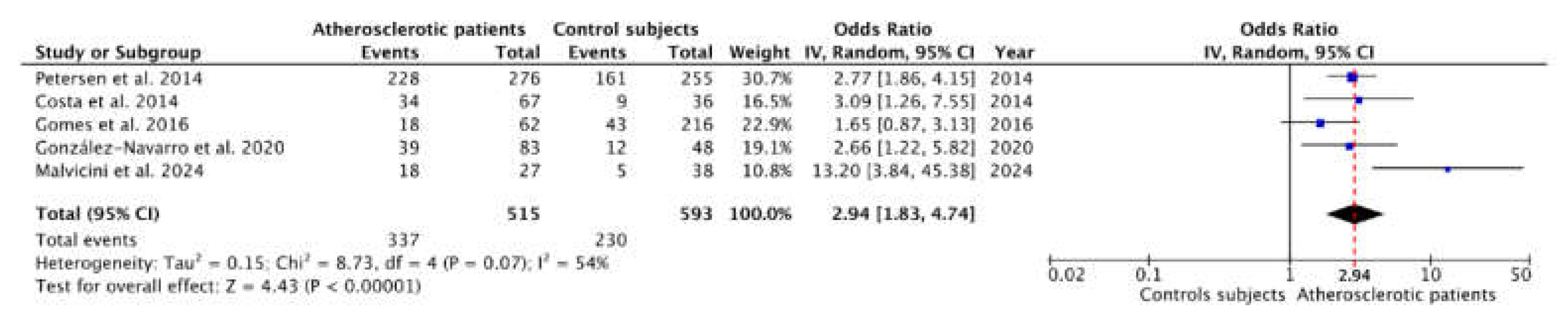

3.2. Meta-Analysis of the Prevalence of Chronic Apical Periodontitis

The data shown in

Table 3 were used to perform the meta-analysis, which forest plot is shown in

Figure 2. The blue squares represent the point estimate of the OR, and these are proportional in area to the study size. The horizontal lines represent the 95% confidence intervals. The black diamond shows the statistical summary of the five studies, and the red dotted vertical line indicates the calculated overall OR. This overall OR was determined using the inverse variance random effects method, resulting in an OR = 2.94 (95% CI = 1.83 – 4.74; p < 0.01). The heterogeneity value was I

2 = 54% (Tau

2 = 0.15; p = 0.07) indicating a moderate level of heterogeneity among the studies.

3.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

According to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale [

21], risk of bias was evaluated for each study (

Table 4). The five studies were classified as moderate risk of bias. The overall sum of the scores of the five studies was 30, indicating a moderate overall risk of bias.

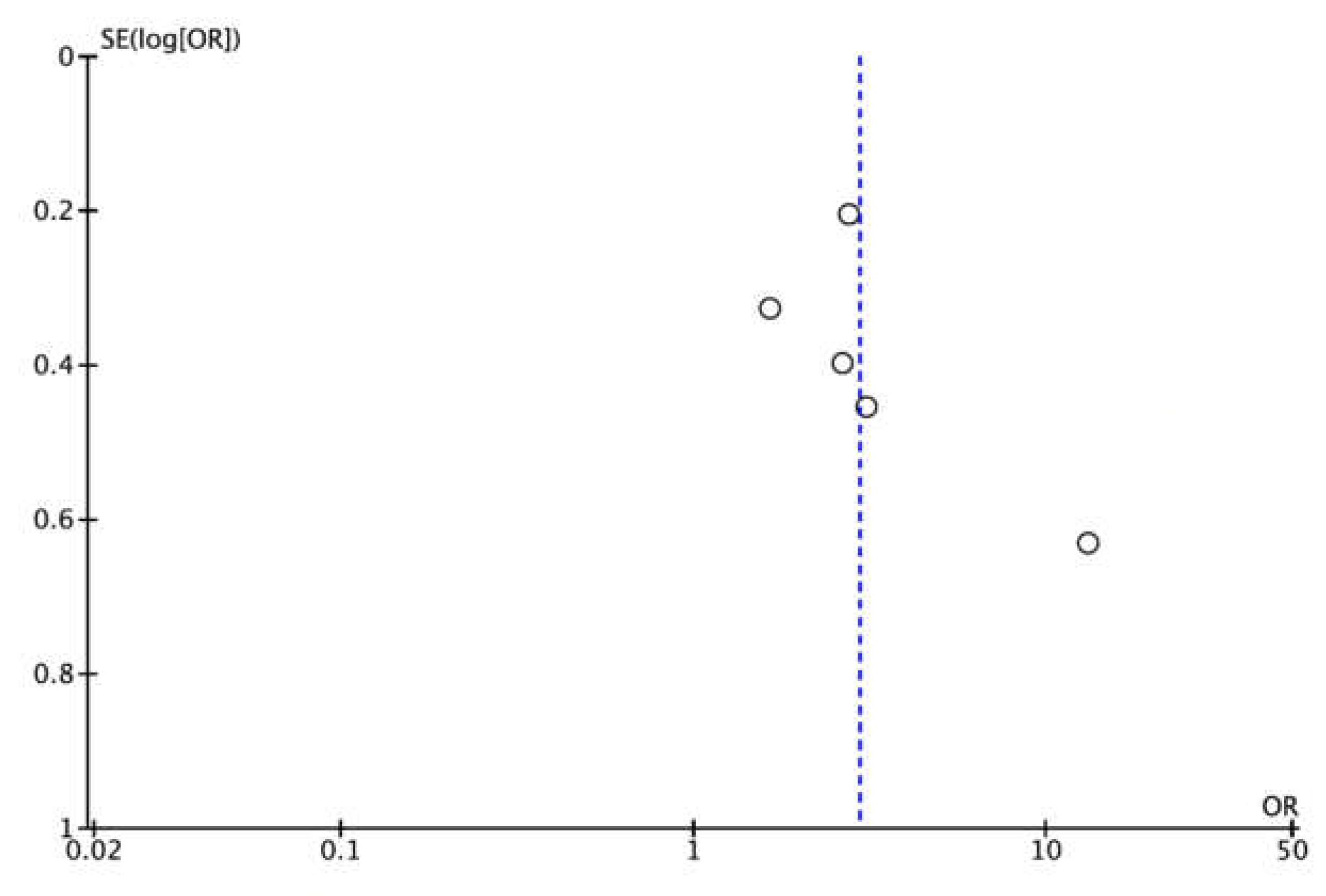

3.4. Publication Bias

Publication bias could not be assessed quantitatively as there were fewer than the required minimum of 10 studies [

20]. However, a funnel plot was plotted to illustrate the possible existence of publication bias (

Figure 3).

3.5. GRADE Evaluation: Level of Certainty

The certainty of evidence was assessed using the GRADE tool (

Table 5). All included studies were observational; therefore the initial level of certainty is low. The domain risk of bias, according to its overall result (moderate), was classified as “not serious”. The domain inconsistency received the ‘not serious’ classification as the heterogeneity was moderate (I

2 = 54%). Indirectness domain was classified as ‘not serious’ as the studies did not perform indirect comparisons or present indirect results. The included populations were representative of the atherosclerotic patients and CAP was reliably evaluated. However, the domain of imprecision was rated ‘serious’ since the 95% CI of the estimated effect (OR) was out of 0.75-1.25, and the number of included studies was moderate (only 5 studies). While there were not enough studies to perform a quantitative assessment of publication bias, it was not considered significant enough to downgrade the quality of evidence, as studies from various journals with varying sample sizes were included and none were funded by the private sector. For all the above, the certainty of the evidence was classified as low, indicating that the true effect might be markedly different from the estimated effect.

4. Discussion

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to investigate the relationship between the prevalence of CAP and atherosclerosis. After analyzing the studies published in the literature to date, the null hypothesis can be rejected, that is, the prevalence of CAP is higher in patients with atherosclerosis compared to healthy control subjects. This finding supports the hypothesis that CAP could significantly impact cardiovascular health, emphasizing the importance of an integrated approach to oral and systemic healthcare.

The overall OR provided by the meta-analysis (OR = 2.94; p < 0.01) suggested that patients with atherosclerosis are nearly 3 times more likely to present CAP than patients without this condition. However, the overall risk of bias was moderate and the evaluation of the level of certainty, carried out with the GRADE tool [

24], concluded that the level of certainty is low, that is, the true effect might be markedly different from the estimated effect.

4.1. Methodological Differences and Heterogeneity

Among the included studies there are marked differences in the methodology used to detect apical periodontitis and to diagnose atherosclerosis. This has probably influenced the calculated heterogeneity value (I

2 = 54%). Each radiographic technique has its own limitations for diagnosing periapical pathology. Periapical and panoramic radiographs are useful for initial evaluations of pathology [

39], but CBCT provides more advanced and detailed information [

40]. However, CBCT has significant drawbacks, such as its high cost and lower accessibility, so it should be reserved for specific cases of diagnosis and follow-up of periapical pathology [

41].

Regarding the diagnosis of atherosclerotic conditions, all included studies confirmed the atherosclerotic status of patients clinically or by imaging techniques. Therefore, there is correspondence between the conditions of the included studies and the specific research PICO question, without indirectness, and this has been considered in the evaluation of the level of certainty.

The first study investigating the possible association between CAP and coronary heart disease was carried out in 2003 [

30], but was not included in the review because the study sample involved patients with different pathologies. On the contrary, all the studies included in the systematic review determined the relationship between the prevalence of CAP in control healthy subjects and in patients with atherosclerotic condition, assessed clinically or by imaging techniques.

The study by Petersen et al. (2014) is the one that contributes the highest percentage of subjects (48%) to the meta-analysis and also the one that finds the highest prevalence of CAP in both atherosclerotic patients and controls. The results of this study provided an OR of 2.83 (p < 0.01) for the association between atherosclerosis and CAP. Three other studies [

35,

36,

37] included in the systematic review also provided similar OR values. On the contrary, the study conducted by Gomes et al. (2016), including 278 subjects, provided a non-significant OR = 1.65 (p = 0.126). The prevalence of CAP found both in the control group (20%) and the atherosclerotic group (29%) in this study are strikingly low compared to that calculated for the healthy world population (52%) [

2], this could explain its non-significant result. Other differences in the results of the included studies may be attributed to variability in the methodologies used to diagnose CAP and atherosclerosis, as well as population and design differences.

4.2. Pathophysiological Implications

Although it is not the objective of this study, the application of the criteria of biological plausibility and scientific coherence stated by Hill [

42] advises analyzing the possible biological mechanisms that could explain the association between endodontic infection and atherosclerosis. The relationship between CAP and atherosclerosis can be explained by several pathophysiological mechanisms [

43]. Chronic inflammation from CAP may induce endothelial dysfunction [

12,

44], a critical step in the development of atherosclerosis. Endothelial dysfunction, characterized by reduced nitric oxide production, adversely affects vascular tone regulation and promotes the formation of atherosclerotic plaques [

44].

Low grade chronic inflammation can also increase the risk of atherosclerosis and insulin resistance which are the leading mechanisms in the development of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) [

45]. Apical periodontitis is associated with elevated levels of inflammatory markers such as interleukins, immunoglobulins, and C-reactive protein in humans [

46]. These findings suggest that apical periodontitis contributes to low-level systemic inflammation [

47] and is not limited to a localized lesion, leading to an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases [

48]. Additionally, inflammatory mediators released during CAP, such as interleukins and C-reactive protein, may enter the bloodstream, contributing to vascular damage [

7,

49,

50]. The presence of chronic inflammation in adults with CAP could act as a risk factor for various cardiovascular diseases, contributing to the reduction in flow-mediated dilation and an increase in carotid intima thickness [

12,

37].

Another proposed mechanism involves the potential role of bacterial dissemination. Pathogens associated with CAP, such as Porphyromonas endodontalis and Enterococcus faecalis, may invade the bloodstream and adhere to vascular endothelium, directly contributing to plaque formation and vascular inflammation [

43,

51,

52]. This bacterial insult can synergize with systemic inflammation to accelerate the progression of atherosclerotic lesions, highlighting the multifaceted nature of this association [

53].

Experimental studies have also demonstrated that CAP can exacerbate atherosclerosis. Conti et al. (2020) and Gan et al. (2022) documented that animal models with CAP developed higher levels of systemic inflammation and atherosclerotic plaque formation compared to controls. These findings support the hypothesis of a bidirectional connection between oral inflammatory pathologies and cardiovascular diseases [

54].

4.3. Clinical Implications

The results of this systematic review and meta-analysis have an evident clinical interest, as they suggest a relationship between atherosclerosis and endodontic disease. Dentists should be aware that CAP could serve as a potential cardiovascular risk indicator, and physicians should consider oral health as an integral part of the evaluation and management of patients with atherosclerosis. Interdisciplinary collaboration is essential to address these risks effectively. For example, early detection and treatment of CAP could reduce systemic inflammatory states and potentially mitigate the progression of atherosclerosis. Similarly, periodic monitoring of atherosclerosis patients in dental clinics could help identify undiagnosed CAP cases. Therefore, it is essential to consider this relationship in the daily clinical practice of dentists and healthcare professionals in general.

This systematic review, together with other published studies [

55,

56,

57,

58], have highlighted the relationship between CAP and several systemic diseases [

43,

54] making it crucial for clinicians to study these relationships to better understand and communicate the prognosis of a tooth undergoing endodontic treatment. Moreover, systemic diseases can influence the outcome of root canal treatment [

49].

However, the results of this review must be considered in their entirety. The GRADE system was applied to assess the certainty of evidence, starting at a low level due to the observational nature of the included studies. Domains such as risk of bias, inconsistency, and indirectness were classified as "not serious," while imprecision was rated "serious" due to the confidence intervals and the limited number of studies. Overall, the evidence was classified as low certainty, suggesting that the true effect might differ substantially from the estimated effect.

4.4. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

The conducted meta-analysis has been based on a robust methodological approach, adhering to PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews [

18]. The inclusion of five studies involving 1,108 participants allows for a statistical synthesis providing a highly significant OR for the association between atherosclerosis and CAP. The use of standardized tools, such as the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale and the GRADE system, ensures a rigorous evaluation of bias and evidence quality.

Despite its strengths, this study has notable limitations. First, the number of studies included in the meta-analysis was limited (n=5), which may affect the generalizability of the results. Additionally, methodological heterogeneity among studies was moderate (I2 = 54.2%), reflecting differences in diagnostic techniques used to identify CAP and atherosclerosis. For instance, while some studies employed panoramic radiographs, others used periapical radiographs or computed tomography, potentially influencing the detection of periapical lesions.

Another limitation is the lack of population representativeness in the samples studied. Most patients were selected from university dental clinics, potentially introducing selection bias. Furthermore, not all studies excluded edentulous patients, which might have altered the CAP prevalence estimates.

4.5. Future Directions

Future studies should focus on prospective designs to establish causal relationships between CAP and atherosclerosis. Additionally, evaluating the impact of endodontic treatment on the progression of atherosclerosis and exploring the role of specific inflammatory biomarkers in this association would be valuable. Finally, the inclusion of more diverse and representative samples will allow for greater generalizability of results.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis suggests a significant association between atherosclerosis and CAP. Patients with atherosclerosis are almost three times more likely to have CAP, highlighting the importance of considering oral health as a key component in the prevention and management of cardiovascular diseases. This result should be translated to daily clinical practice. Integrating oral care strategies into medical practice could improve overall health outcomes in patients with these chronic conditions. It is important for the healthcare community to be aware of this association in order to suspect atherosclerotic pathology in patients who show a high incidence of periapical pathology in their dental history.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author Contributions

All authors have reviewed and approved the submitted version. The au-thors declare: "Conceptualization, J.M.-G, D.C.-B & J.J.S.-E; Methodology and Software, D.C.-B; B.S.-D, & J.J.S.-E; Validation, J.J.S.-E, J.M.-G, D.C.-B, & M.L.-L.; Formal Analysis, M.L.-L. & D.C.-B; Investigation, M.L-L, J.J.S.-M, B.S.-D, & J.J.S.-E; Data Curation, JJ.S.-E, M.L-L., J.M.-G & D.C.-B; Writing - Original Draft Preparation, J.J.S.-S, M.L.-L. & D.C.-B; Writing - Review & Editing, D.C.-B, J.M.-G, M.L.-L. & J.J.S.-E; Visualization, J.J.S.-M., B.S.-D. & J.J.S.-E.; Supervision, J.J.S.E. & J.M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are public.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CAP |

Chronic apical periodontitis |

CT

CI |

Confidence interval

Computed tomography |

| OR |

Odds ratio |

References

- Siqueira, J.F.; Rôças, I.N. The microbiota of acute apical abscesses. J. Dent. Res. 2009, 88, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tibúrcio-Machado, C.S.; Michelon, C.; Zanatta, F.B.; Gomes, M.S.; Marin, J.A.; Bier, C.A. The global prevalence of apical periodontitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Endod. J. 2021, 54, 712–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orstavik, D.; Kerekes, K.; Eriksen, H.M.; Ørstavik, D.; Kerekes, K.; Eriksen, H.M. The periapical index: A scoring system for radiographic assessment of apical periodontitis. Dent. Traumatol. 1986, 2, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libby, P. The changing landscape of atherosclerosis. Nature 2021, 592, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushenkova, N. V.; Summerhill, V.I.; Zhang, D.; Romanenko, E.B.; Grechko, A. V.; Orekhov, A.N. Current Advances in the Diagnostic Imaging of Atherosclerosis: Insights into the Pathophysiology of Vulnerable Plaque. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusev, E.; Sarapultsev, A. Atherosclerosis and Inflammation: Insights from the Theory of General Pathological Processes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutsopoulos, N.M.; Madianos, P.N. Low-grade inflammation in chronic infectious diseases: paradigm of periodontal infections. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1088, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotti, E.; Dessì, C.; Piras, A.; Mercuro, G. Can a chronic dental infection be considered a cause of cardiovascular disease? A review of the literature. Int. J. Cardiol. 2011, 148, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papi, P.; Pranno, N.; Di Murro, B.; Pompa, G.; Polimeni, A.; Letizia, C.; Petramala, L.; Concistrè, A.; Muñoz Aguilera, E.; Orlandi, M.; et al. Association between subclinical atherosclerosis and oral inflammation: A cross-sectional study. J. Periodontol. 2023, 94, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doughan, M.; Chehab, O.; de Vasconcellos, H.D.; Zeitoun, R.; Varadarajan, V.; Doughan, B.; Wu, C.O.; Blaha, M.J.; Bluemke, D.A.; Lima, J.A.C. Periodontal Disease Associated With Interstitial Myocardial Fibrosis: The Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, N.; Mittal, S.; Tewari, S.; Sen, J.; Laller, K. Association of Apical Periodontitis with Cardiovascular Disease via Noninvasive Assessment of Endothelial Function and Subclinical Atherosclerosis. J. Endod. 2019, 45, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotti, E.; Dess, C.; Piras, A.; Flore, G.; Deidda, M.; Madeddu, C.; Zedda, A.; Longu, G.; Mercuro, G. Association of endodontic infection with detection of an initial lesion to the cardiovascular system. J. Endod. 2011, 37, 1624–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, M.S.; Hugo, F.N.; Hilgert, J.B.; Sant’Ana Filho, M.; Padilha, D.M.P.; Simonsick, E.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Reynolds, M.A. Apical periodontitis and incident cardiovascular events in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Int. Endod. J. 2016, 49, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabanillas-Balsera, D.; Areal-Quecuty, V.; Cantiga-Silva, C.; de Cardoso, C.B.M.; Cintra, L.T.A.; Martín-González, J.; Segura-Egea, J.J. Prevalence of apical periodontitis and non-retention of root-filled teeth in hypertensive patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leão, T.S.S.; Tomasi, G.H.; Conzatti, L.P.; Marrone, L.C.P.; Reynolds, M.A.; Gomes, M.S. Oral Inflammatory Burden and Carotid Atherosclerosis Among Stroke Patients. J. Endod. 2022, 48, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, L.C.; Segura-Egea, J.J.; Cardoso, C.B.M.; Benetti, F.; Azuma, M.M.; Oliveira, P.H.C.; Bomfim, S.R.M.; Cintra, L.T.A. Relationship between apical periodontitis and atherosclerosis in rats: lipid profile and histological study. Int. Endod. J. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Gan, G.; Lu, B.; Zhang, R.; Luo, Y.; Chen, S.; Lei, H.; Li, Y.; Cai, Z.; Huang, X. Chronic apical periodontitis exacerbates atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice and leads to changes in the diversity of gut microbiota. Int. Endod. J. 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; Estarli, M.; Barrera, E.S.A.; et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Rev. Esp. Nutr. Humana y Diet. 2016, 20, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, R.; Álvarez-Pasquin, M.J.; Díaz, C.; Del Barrio, J.L.; Estrada, J.M.; Gil, Á. Are healthcare workers intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? BMC Public Health 2013, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- León-López, M.; Cabanillas-Balsera, D.; Martín-González, J.; Montero-Miralles, P.; Saúco-Márquez, J.J.; Segura-Egea, J.J. Prevalence of root canal treatment worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55, 1105–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Montori, V.; Akl, E.A.; Djulbegovic, B.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence--study limitations (risk of bias). J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hultcrantz, M.; Rind, D.; Akl, E.A.; Treweek, S.; Mustafa, R.A.; Iorio, A.; Alper, B.S.; Meerpohl, J.J.; Murad, M.H.; Ansari, M.T.; et al. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 87, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedlander, A.H.; Sung, E.C.; Chung, E.M.; Garrett, N.R. Radiographic quantification of chronic dental infection and its relationship to the atherosclerotic process in the carotid arteries. Oral Surgery, Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontology 2010, 109, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glodny, B.; Nasseri, P.; Crismani, A.; Schoenherr, E.; Luger, A.; Bertl, K.; Petersen, J. The occurrence of dental caries is associated with atherosclerosis. Clinics 2013, 68, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liljestrand, J.M.; Mäntylä, P.; Paju, S.; Buhlin, K.; Kopra, K.A.E.; Persson, G.R.; Hernandez, M.; Nieminen, M.S.; Sinisalo, J.; Tjäderhane, L.; et al. Association of Endodontic Lesions with Coronary Artery Disease. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 1358–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willershausen, B.; Kasaj, A.; Willershausen, I.; Zahorka, D.; Briseño, B.; Blettner, M.; Genth-Zotz, S.; Münzel, T. Association between Chronic Dental Infection and Acute Myocardial Infarction. J. Endod. 2009, 35, 626–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualini, D.; Bergandi, L.; Palumbo, L.; Borraccino, A.; Dambra, V.; Alovisi, M.; Migliaretti, G.; Ferraro, G.; Ghigo, D.; Bergerone, S.; et al. Association among oral health, apical periodontitis, CD14 polymorphisms, and coronary heart disease in middle-aged adults. J. Endod. 2012, 38, 1570–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisk, F.; Hakeberg, M.; Ahlqwist, M.; Bengtsson, C. Endodontic variables and coronary heart disease. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2003, 61, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, L.; Lavstedt, S.; Frithiof, L.; Theobald, H. Relationship between oral health and mortality in cardiovascular diseases. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2001, 28, 762–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowan, L.T.; Lakshminarayan, K.; Lutsey, P.L.; Beck, J.; Offenbacher, S.; Pankow, J.S. Endodontic therapy and incident cardiovascular disease: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. J. Public Health Dent. 2020, 80, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; He, M.; Yin, T.; Zheng, Z.; Fang, C.; Peng, S. Association of severely damaged endodontically infected tooth with carotid plaque and abnormal carotid intima-media thickness: a retrospective analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 4677–4686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, J.; Glaßl, E.-M.M.; Nasseri, P.; Crismani, A.; Luger, A.K.; Schoenherr, E.; Bertl, K.; Glodny, B. The association of chronic apical periodontitis and endodontic therapy with atherosclerosis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2014, 18, 1813–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, T.H.R.; Neto, J.A.D.F.; De Oliveira, A.E.F.; Maia, M.D.F.L.E.; de Almeida, A.L.; de Figueiredo Neto, J.A.; De Oliveira, A.E.F.; Lopes e Maia, M. de F. ; de Almeida, A.L. Association between chronic apical periodontitis and coronary artery disease. J. Endod. 2014, 40, 164–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Navarro, B.; Segura-Egea, J.J.; Estrugo-Devesa, A.; Pintó-Sala, X.; Jane-Salas, E.; Jiménez-Sánchez, M.C.; Cabanillas-Balsera, D.; López-López, J. Relationship between apical periodontitis and metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular events: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvicini, G.; Marruganti, C.; Leil, M.A.; Martignoni, M.; Pasqui, E.; de Donato, G.; Grandini, S.; Gaeta, C. Association between apical periodontitis and secondary outcomes of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: A case–control study. Int. Endod. J. 2024, 57, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howick, J.; Chalmers, I.; Glasziou, P.; Greenhalgh, T.; Heneghan, C.; Liberati, A.; Moschetti, I.; Phillips, B.; Thornton, H. The 2011 Oxford CEBM Levels of Evidence: Introductory Document. Oxford Cent. Evidence-Based Med. http//www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653 2011, 1–3.

- Ríos-Santos, J. V.; Ridao-Sacie, C.; Bullón, P.; Fernández-Palacín, A.; Segura-Egea, J.J. Assessment of periapical status: A comparative study using film-based periapical radiographs and digital panoramic images. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2010, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Giudice, R.; Nicita, F.; Puleio, F.; Alibrandi, A.; Cervino, G.; Lizio, A.S.; Pantaleo, G. Accuracy of Periapical Radiography and CBCT in Endodontic Evaluation. Int. J. Dent. 2018, 2018, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Durack, C.; Abella, F.; Roig, M.; Shemesh, H.; Lambrechts, P.; Lemberg, K. European Society of Endodontology position statement: The use of CBCT in Endodontics. Int. Endod. J. 2014, 47, 502–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HILL, A.B. THE ENVIRONMENT AND DISEASE: ASSOCIATION OR CAUSATION? Proc. R. Soc. Med. 1965, 58, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura-Egea, J.J.; Martín-González, J.; Castellanos-Cosano, L. Endodontic medicine: connections between apical periodontitis and systemic diseases. Int. Endod. J. 2015, 48, 933–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotti, E.; Zedda, A.; Deidda, M.; Piras, A.; Flore, G.; Ideo, F.; Madeddu, C.; Pau, V.M.; Mercuro, G. Endodontic Infection and Endothelial Dysfunction Are Associated with Different Mechanisms in Men and Women. J. Endod. 2015, 41, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soysal, P.; Arik, F.; Smith, L.; Jackson, S.E.; Isik, A.T. Inflammation, Frailty and Cardiovascular Disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1216, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, A.C.; Twisk, J.W.R.; Crielaard, W.; Ouwerling, P.; Schoneveld, A.H.; van der Waal, S.V. The influence of apical periodontitis on circulatory inflammatory mediators in peripheral blood: A prospective case-control study. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56, 130–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarabi, G.; Heydecke, G.; Seedorf, U. Roles of Oral Infections in the Pathomechanism of Atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, A.C.; Crielaard, W.; Armenis, I.; de Vries, R.; van der Waal, S. V. Apical Periodontitis Is Associated with Elevated Concentrations of Inflammatory Mediators in Peripheral Blood: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Endod. 2019, 45, 1279–1295e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Egea, J.J.; Cabanillas-Balsera, D.; Martín-González, J.; Cintra, L.T.A. Impact of systemic health on treatment outcomes in endodontics. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56 Suppl 2, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirin, D.A.; Ozcelik, F.; Uzun, C.; Ersahan, S.; Yesilbas, S. Association between C-reactive protein, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and the burden of apical periodontitis: a case-control study. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2019, 77, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajishengallis, G.; Chavakis, T. Local and systemic mechanisms linking periodontal disease and inflammatory comorbidities. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminoshariae, A.; Ms, D.D.S.; Kulild, J.C.; Ms, D.D.S.; Fouad, A.F.; Ms, D.D.S. The Impact of Endodontic Infections on the Pathogenesis of Cardiovascular Disease ( s ): A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis Using GRADE. J. Endod. 2018, 44, 1361–1366e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cintra, L.T.A.; Estrela, C.; Azuma, M.M. ; Queiroz, índia O. de A.; Kawai, T.; Gomes-Filho, J.E. Endodontic medicine: Interrelationships among apical periodontitis, systemic disorders, and tissue responses of dental materials. Braz. Oral Res. 2018, 32, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cintra, L.T.A.; Gomes, M.S.; da Silva, C.C.; Faria, F.D.; Benetti, F.; Cosme-Silva, L.; Samuel, R.O.; Pinheiro, T.N.; Estrela, C.; González, A.C.; et al. Evolution of endodontic medicine: a critical narrative review of the interrelationship between endodontics and systemic pathological conditions. Odontology 2021, 109, 741–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura-Egea, J.J.; Cabanillas-Balsera, D.; Jiménez-Sánchez, M.C.; Martín-González, J. Endodontics and diabetes: association versus causation. Int. Endod. J. 2019, 52, 790–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabanillas-Balsera, D.; Segura-Egea, J.J.; Bermudo-Fuenmayor, M.; Martín-González, J.; Jiménez-Sánchez, M.C.; Areal-Quecuty, V.; Sánchez-Domínguez, B.; Montero-Miralles, P.; Velasco-Ortega, E. Smoking and Radiolucent Periapical Lesions in Root Filled Teeth: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Sánchez, M.; Cabanillas-Balsera, D.; Areal-Quecuty, V.; Velasco-Ortega, E.; Martín-González, J.; Segura-Egea, J. Cardiovascular diseases and apical periodontitis: association not always implies causality. Med. Oral Patol. Oral y Cir. Bucal 2020, 0–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovljevic, A.; Ideo, F.; Jacimovic, J.; Aminoshariae, A.; Nagendrababu, V.; Azarpazhooh, A.; Cotti, E. The Link Between Apical Periodontitis and Gastrointestinal Diseases-A Systematic Review. J. Endod. 2023, 49, 1421–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).