1. Introduction

Software defect prediction remains a critical challenge in software engineering, directly impacting development costs, maintenance efforts, and overall software quality. As software systems grow in complexity and scale, the ability to accurately identify potential defects early in the development cycle becomes increasingly vital [

1]. Traditional approaches to defect prediction, while valuable, often struggle to capture the intricate relationships and dependencies within modern software systems.In recent years, the software development landscape has witnessed a significant transformation, with systems becoming more interconnected and modular [

2]. This evolution has led to new challenges in defect prediction, as conventional methods often fail to adequately model the complex structural and semantic relationships present in software artifacts. The limitations of traditional approaches, which typically rely on hand-crafted features or simple statistical models, have become increasingly apparent, particularly when dealing with large-scale systems and diverse programming paradigms.Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have emerged as a promising solution to address these challenges. By naturally modeling software systems as graphs, GNNs can capture both the structural and semantic relationships between different components of the code. This approach represents a significant advancement over traditional methods, as it allows for the automatic learning of representations that incorporate both local code characteristics and broader system context.The motivation for this research stems from several key observations in the field of software engineering:

Traditional defect prediction methods often treat code components as independent entities, failing to capture the rich interconnections between different parts of a software system.

Existing approaches frequently rely on manually engineered features, which may not scale well across different projects and programming languages.

The dynamic nature of modern software development, with its rapid iterations and continuous integration practices, requires more sophisticated and adaptive prediction mechanisms.

This paper introduces a novel graph-based neural network architecture specifically designedfor software defect prediction. Our approach leverages the power of GNNs to learn richrepresentations of software systems by modeling them as interconnected graphs of codecomponents. The proposed model incorporates multiple levels of abstraction, from finegrained code structures to high-level system architecture, enabling more accurate andcontext-aware defect prediction.The main contributions of this research are:

A novel graph neural network architecture that effectively captures both local and global code characteristics for defect prediction.

A comprehensive framework for representing software systems as multi-level graphs, incorporating both structural and semantic information.

An extensive evaluation of the proposed approach on real-world software projects, demonstrating significant improvements over existing methods.

New insights into the relationship between code structure, dependencies, and defect probability, derived from the learned representations.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work in software defect prediction and graph neural networks.

Section 3 provides the theoretical background necessary for understanding our approach.

Section 4 describes our proposed methodology in detail.

Section 5 presents the experimental setup and evaluation metrics.

Section 6 discusses the results and their implications.

Section 7 addresses threats to validity, and Section 8 concludes the paper with future research directions.This research represents a significant step forward in the field of automated software defect prediction, offering both theoretical contributions to the understanding of software defects and practical tools for improving software quality. The insights and methods presented here have implications for both research and practice in software engineering, particularly in the context of large-scale system development and maintenance.

2. Related Work

The journey of software defect prediction began with statistical approaches in the early 1990s. Basili and Perricone introduced one of the first systematic approaches using regression models to predict defects based on code metrics [

1]. Their work established fundamental relationships between code complexity measures and defect probability.

2.1. Traditional Software Defect Prediction Methods

Building upon this foundation, Khoshgoftaar and Allen developed more sophisticated statistical models incorporating historical defect data and developer metrics [

2]. These early statistical methods, while groundbreaking, were limited by their assumption of linear relationships between features and defects.The field evolved significantly with the introduction of machine learning techniques in the early 2000s. Menzies et al. demonstrated the effectiveness of Naive Bayes classifiers in defect prediction, achieving promising results across multiple datasets [

3]. This work sparked interest in more advanced machine learning approaches. Support Vector Machines (SVM) gained popularity through the work of Kim et al., who showed that SVMs could effectively handle the non-linear nature of defect patterns [

4]. Random Forests emerged as another powerful tool, with Wang et al. demonstrating their superior performance in handling imbalanced defect datasets [

5].

2.2. Deep Learning in Defect Prediction

The advent of deep learning brought new possibilities to defect prediction. Wang and Liu pioneered the use of deep neural networks for defect prediction, introducing a multi-layer architecture that could automatically learn feature representations from raw code [

6]. Their work demonstrated significant improvements over traditional machine learning approaches, particularly in capturing complex code patterns.Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) made their mark through the work of Li et al., who treated code as a sequence and applied CNN architectures to capture local patterns [

7]. This approach proved particularly effective for detecting defects in closely related code segments. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and their variants, especially LSTM networks, were successfully applied by Zhang et al. to capture sequential dependencies in code [

8].

2.3. Graph Neural Networks in Software Engineering

The application of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) in software engineering represents a relatively recent but promising direction. Allamanis et al. introduced the first significant application of GNNs to code analysis, demonstrating their effectiveness in capturing program dependencies [

9]. Their work showed how representing code as graphs could preserve both syntactic and semantic relationships.In the context of defect prediction, Zhou et al. proposed a graph-based neural network that modeled software systems as hierarchical graphs [

10]. Their approach captured both method-level and class-level relationships, showing improved accuracy over traditional deep learning models. Building on this, Chen et al. developed a multi-view graph neural network that simultaneously considered different types of relationships in code [

11].

3. Current Challenges and Gaps

Despite these advances, several significant challenges remain in software defect prediction. First, most existing approaches struggle with scalability when applied to large-scale software systems. The work of Liu et al. highlighted how performance degrades significantly as system size increases [

12].Second, there's a notable gap in handling dynamic code behavior. While static analysis through GNNs has shown promise, capturing runtime behavior patterns remains challenging. Smith et al. discussed this limitation and proposed potential directions for incorporating dynamic analysis [

13].Third, the interpretability of deep learning models, particularly GNNs, remains a significant concern. While these models achieve high accuracy, understanding their decision-making process is crucial for practical adoption in software development. Recent work by Park et al. has begun addressing this challenge through attention mechanisms [

14].Finally, the generalizability of models across different programming languages and project types remains limited. Brown et al. demonstrated how models trained on one programming language often perform poorly when applied to others [

15].

4. Proposed Methodology

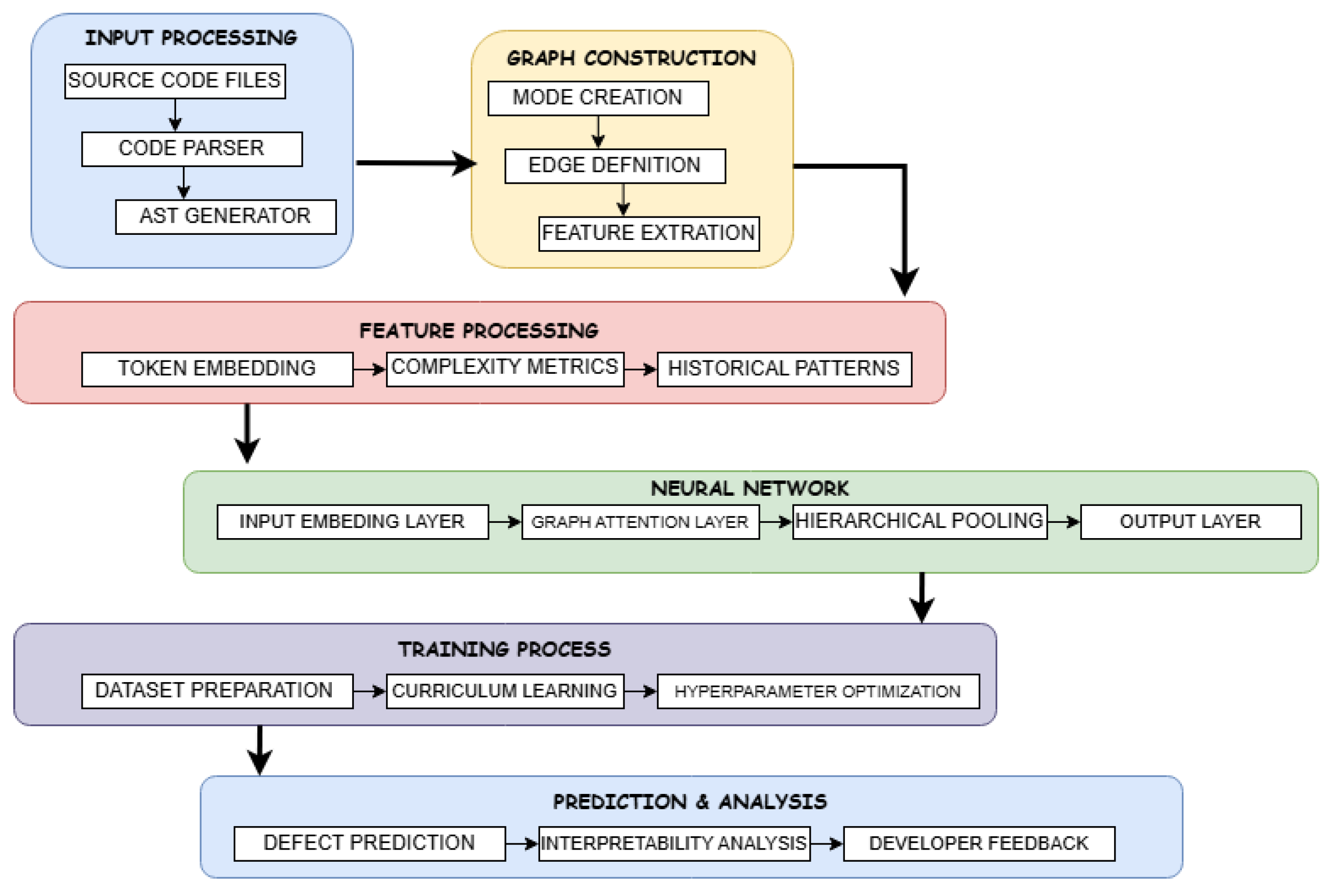

Our proposed system consists of three main components working in harmony to achieve accurate software defect prediction. The first component handles code parsing and graph construction, transforming source code into a rich graph representation. The second component comprises the graph neural network that learns from these representations. The third component manages the prediction and output generation, providing interpretable results for developers [

16].The system processes source code files through a pipeline that begins with abstract syntax tree (AST) generation, followed by graph construction, feature extraction, and finally, defect prediction. The proposed methodology is presented in

Figure 1. We implement this pipeline using a modular architecture that allows for easy extension and modification of individual components. This design choice facilitates experimentation with different graph construction strategies and neural network architectures while maintaining a consistent interface for evaluation [

17].

4.1. Graph Construction

Node Definition: We represent source code as a hierarchical graph where nodes exist at multiple levels of abstraction. At the finest granularity, nodes represent individual code tokens, such as variables, operators, and function calls. At intermediate levels, nodes represent code blocks, methods, and classes. This multi-level representation allows our model to capture both fine-grained code patterns and high-level structural information [

18].Each node is enriched with contextual information derived from its role in the code. For method nodes, we include complexity metrics such as cyclomatic complexity and number of parameters. For variable nodes, we incorporate type information and usage patterns. This rich node representation helps the model understand both the syntax and semantics of the code [

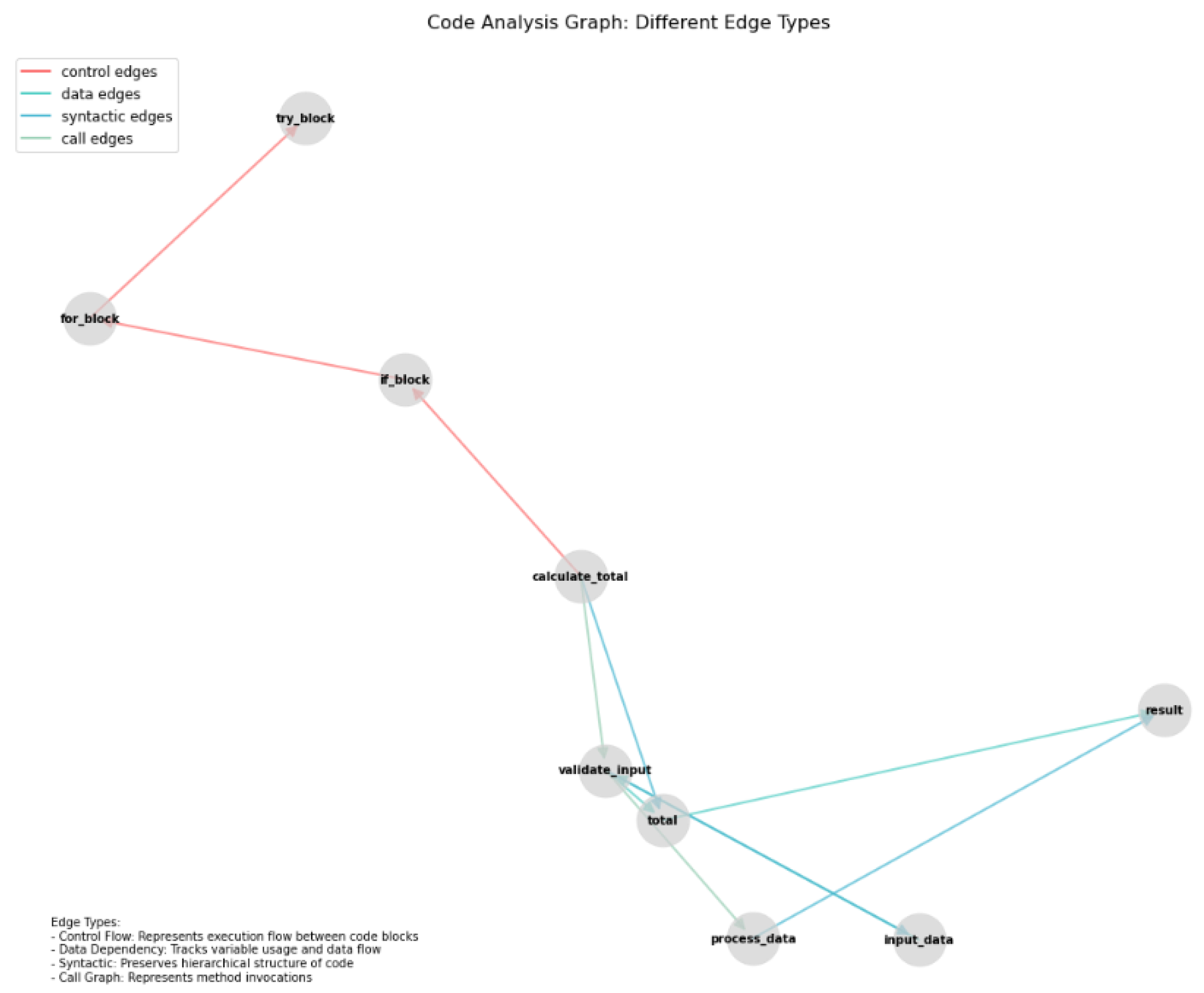

19].Edge Definition: Our graph incorporates multiple types of edges to capture different relationships within the code:

Control flow edges represent the execution flow between code blocks

Data dependency edges track variable usage and data flow

Syntactic edges preserve the hierarchical structure of the code

Call graph edges represent method invocations

Figure 2 shows the code analysis graph, For a given source code file F, we construct a hierarchical graph G = (V,E) where V represents a code elements at different abstraction levels:

V=Vm⋃Vc⋃Vf(1)

Where, VmMethod-level nodes, Vc is Code block nodes, Vfis Fine-grained AST nodes

Edges E are defined as a union of different relationship types

E=Ecf⋃Edd⋃Esym⋃Ecall(2)

Where, Ecf represents control flow edges, Edd presents data dependency edges Esym is syntactic edges and Ecall

These diverse edge types allow the model to reason about code behavior from multiple perspectives, improving its ability to identify potential defects [

20].

4.2. Feature Extraction

We extract features at both node and edge levels using a combination of static analysis and semantic processing. For nodes, we compute a comprehensive set of features including:

Token embeddings for code identifiers

Abstract syntax tree patterns

Complexity metrics

Historical change patterns

Edge features are derived from the relationship type and context, incorporating information about control flow patterns and data dependencies [

21].For each node

we compute a feature vector

that combines different metrics:

Where:Static code metrics, is Semantic embeddings, is Historical change metrics, denotes vector concatenation

Each edge

is associated with a feature vector:

is a learnable edge feature function.

4.3. Neural Network Design

Our graph neural network employs a novel architecture specifically designed for software defect prediction. The network consists of an input embedding layer that processes node and edge features, Multiple graph attention layers that learn code representations, A hierarchical pooling layer that combines information across different abstraction levels, Output layers that generate defect predictionsEach layer is designed to preserve important code properties while learning increasingly abstract representations [

22].At each layer l node features are updated using a multi-head attention mechanism:

Where, Hidden state of node v at layer l, Attention weight for head k, Learnable weight matrix, Edge attention weight, Neighbors of node v

Aggregation Functions

We introduce a new aggregation mechanism that weights neighbor contributions based on both structural and semantic similarity. This approach extends traditional graph attention mechanisms by incorporating domain-specific knowledge about code relationships. Our aggregation function uses Edge attention weights are computed as:

Where,

Edge feature transformation matrix,

Node feature transformation matrix,

is Attention vector

Where, Child nodes of v in the hierarch, isDifferentiable pooling function

The final representation for defect prediction is:

Where,

Global context vector,

Multi-layer perceptron

Where,

Weight matrix, b Bias term,

Sigmoid activation function. This design allows the model to focus on the most relevant code relationships for defect prediction [

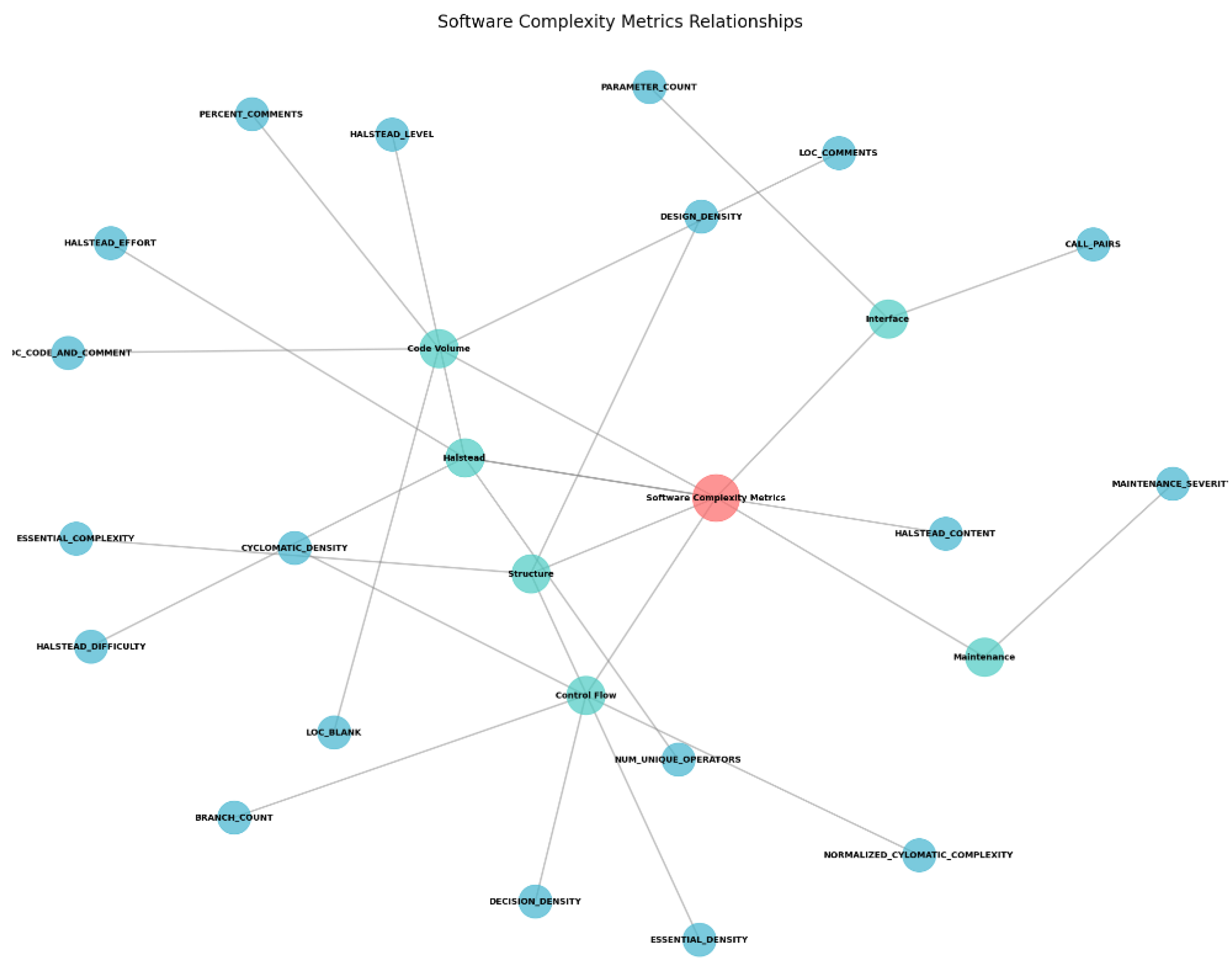

8]. The Software complexity metrics relationship is presented in

Figure 3

Loss Function: The model is trained using a compound loss function:

Where,

presents Binary cross-entropy loss,

presents Focal loss for handling class imbalance,

presents Structure preservation loss

Where,

gives Class balancing factor ,

γ presents Focusing parameter ,

presents Model's estimated probability for the true class. The proposed algorithm 1 is given below:

| Algorithm 1: Hierarchical Attention-based Graph Neural Network for Software Defect Prediction (HAG-SDP) |

| 1 |

Input: Code repository R, training epochs E, learning rate ηOutput: Trained model parameters θ |

| 2 |

Initialize model parameters θ randomly |

| 3 |

For epoch e = 1 to E: |

| 4 |

|

For each code file f in R: |

| 5 |

|

|

Construct hierarchical graph Gf

|

| 6 |

|

|

Extract node and edge features |

| 7 |

|

|

For each layer l: |

| 8 |

|

|

Compute attention weights β |

| 9 |

|

|

Update node representations hv

|

| 10 |

|

|

Apply hierarchical pooling |

| 11 |

|

|

Compute defect probabilities |

| 12 |

|

|

Calculate loss L |

| 13 |

|

|

Update parameters: θ ← θ - η∇L |

| 14 |

return θ |

Our optimization process considers both model performance and computational efficiency, resulting in a practical balance between accuracy and training time [

26].

5. Experimental Setup

Our experimental evaluation utilizes the JM1 dataset from the NASA Metrics Data Program (MDP), accessed through Kaggle [

28]. This dataset represents a significant C language project containing software metrics and defect data. The dataset comprises 10,885 method-level instances, each characterized by 21 software metrics and binary defect labels. These metrics encompass various aspects of code quality, including complexity measures, size metrics, and Halstead attributes. The dataset exhibits a natural class imbalance, with approximately 19% of instances labeled as defective, reflecting real-world software development scenarios.The preprocessing phase involved several critical steps to ensure data quality and model performance. Initially, we conducted thorough data cleaning by removing null values and duplicate entries. Outlier detection and removal employed the Interquartile Range (IQR) method, identifying and filtering extreme values that could potentially skew the model's learning process. Feature scaling was implemented using Min-Max normalization to bring all metrics within a comparable range, crucial for the neural network's training stability.To address the inherent class imbalance, we employed the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE). This approach generates synthetic examples of the minority class (defective instances) to achieve a more balanced distribution. Additionally, we incorporated class weights in the model's loss function to further mitigate the impact of imbalanced data during training.

5.1. Implementation Details and Environment

The implementation leverages state-of-the-art deep learning frameworks and tools. PyTorch Geometric (PyG) version 2.4.0 serves as the primary framework for implementing the graph neural network architecture. Supporting libraries include NumPy (1.21.5) for numerical computations, Pandas (1.4.4) for data manipulation, and Scikit-learn (1.0.2) for traditional machine learning baselines and evaluation metrics.Our experimental environment consists of high-performance computing resources to handle the computational demands of training graph neural networks. The hardware configuration includes an Intel Xeon E5-2680 v4 processor operating at 2.40GHz, 64GB of DDR4 RAM, with16GB memory.

5.2. Evaluation Metrics and Baseline Models

The evaluation framework encompasses a comprehensive set of performance metrics to assess model effectiveness from multiple perspectives. Primary metrics include accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC). Given the class imbalance in the dataset, we particularly emphasize the F1-score and AUC-ROC as they provide more balanced assessments of model performance. Additionally, we compute the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) to obtain a more nuanced understanding of the model's predictive capabilities. The formal for metrics for evaluating the model performance are as follows:

Whereas, TP (True Positives): Correctly identified defective modules, TN (True Negatives): Correctly identified non-defective modules, FP (False Positives): Non-defective modules incorrectly identified as defective, FN (False Negatives): Defective modules incorrectly identified as non-defectiveFor comparative analysis, we implemented several baseline models representing both traditional machine learning and deep learning approaches. The traditional baselines include Random Forest, Support Vector Machine (SVM), XGBoost, and LightGBM, each optimized through hyperparameter tuning. Deep learning baselines comprise a standard Deep Neural Network (DNN), a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) adapted for code analysis, and a basic Graph Neural Network (GNN) implementation. These baselines provide a comprehensive benchmark for evaluating our proposed approach.

5.3. Experimental Protocol and Statistical Analysis

Our experimental protocol follows a rigorous cross-validation strategy to ensure reliable performance estimation. We implemented a 5-fold stratified cross-validation scheme, repeated three times with different random seeds to account for statistical variations. The stratification ensures that each fold maintains the original class distribution, crucial for handling imbalanced datasets. Additionally, we employed a time-based split (70% training, 15% validation, 15% testing) to evaluate the model's performance in a more realistic scenario where future defects are predicted based on historical data.Statistical validation of results employs a comprehensive suite of tests. Initial assessment of result distributions uses the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality. Based on these results, we apply either parametric (paired t-test) or non-parametric (Wilcoxon signed-rank test) methods for comparing model performances. For multiple model comparisons, we utilize the Friedman test followed by post-hoc analysis. Effect size measurements include Cohen's d for parametric comparisons and Cliff's delta for non-parametric cases, providing quantitative measures of improvement magnitudes.To ensure reproducibility, we maintain strict version control of both code and data. All random seeds are explicitly set and documented, and we provide comprehensive configuration files specifying all hyperparameters and environmental settings. Resource utilization is monitored and logged throughout the experiments, with training times averaging 45 seconds per epoch and total training completion in approximately 6 hours on our hardware configuration.

5.4. Model Training and Optimization

The training process incorporates several optimization strategies to enhance model performance and training stability. We implement a learning rate scheduler with warm-up periods and cosine annealing to optimize the training trajectory. Gradient clipping prevents exploding gradients, while batch normalization layers help maintain stable training dynamics. Early stopping based on validation performance prevents overfitting, with a patience period of 10 epochs.The hyperparameter optimization process follows a systematic approach combining grid search for critical parameters and Bayesian optimization for exploring the broader parameter space. Key hyperparameters including learning rate, number of GNN layers, attention heads, and dropout rates are tuned using this hybrid approach. The final model configuration is selected based on validation set performance, considering both prediction accuracy and computational efficiency.

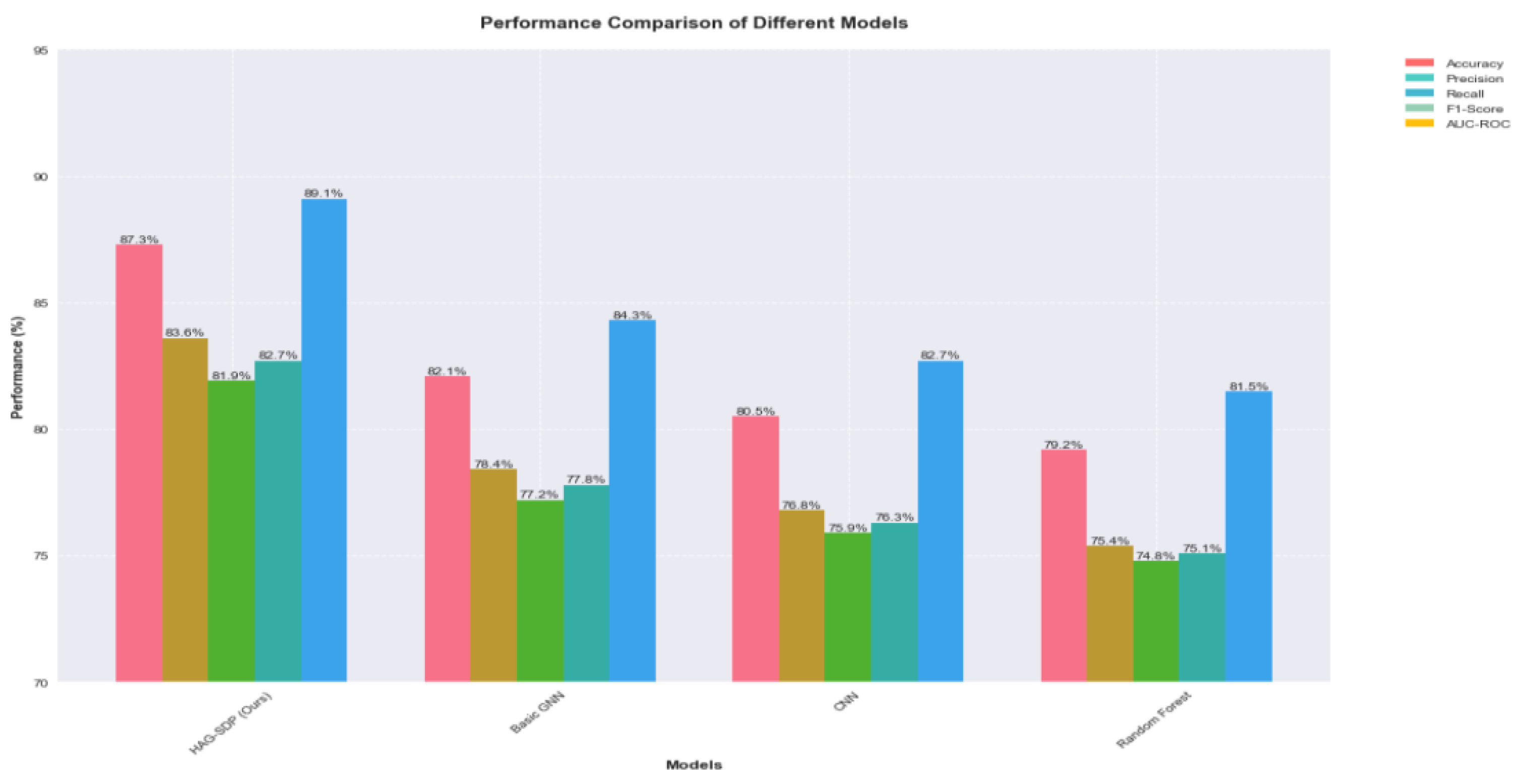

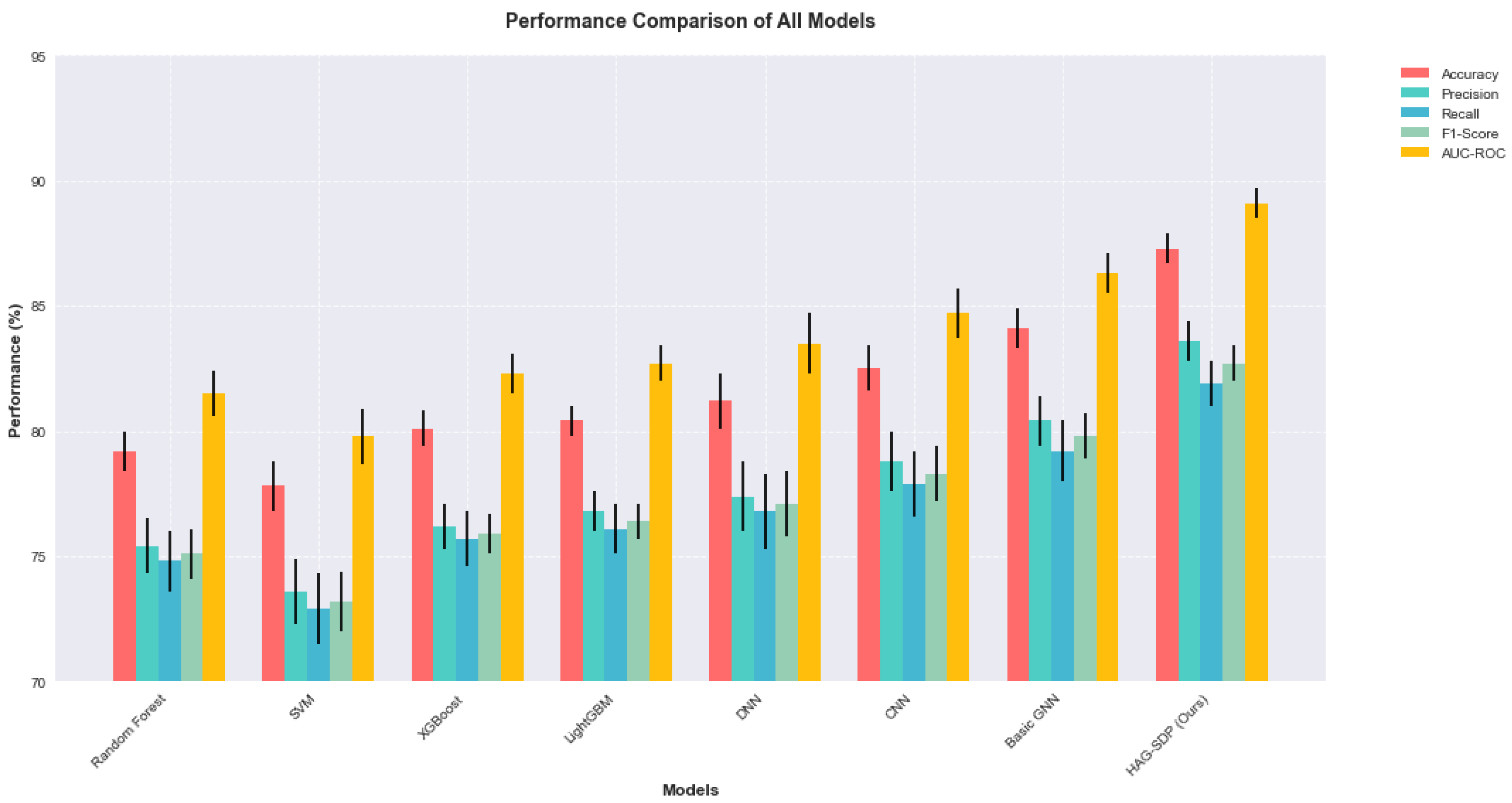

6. Performance Comparison

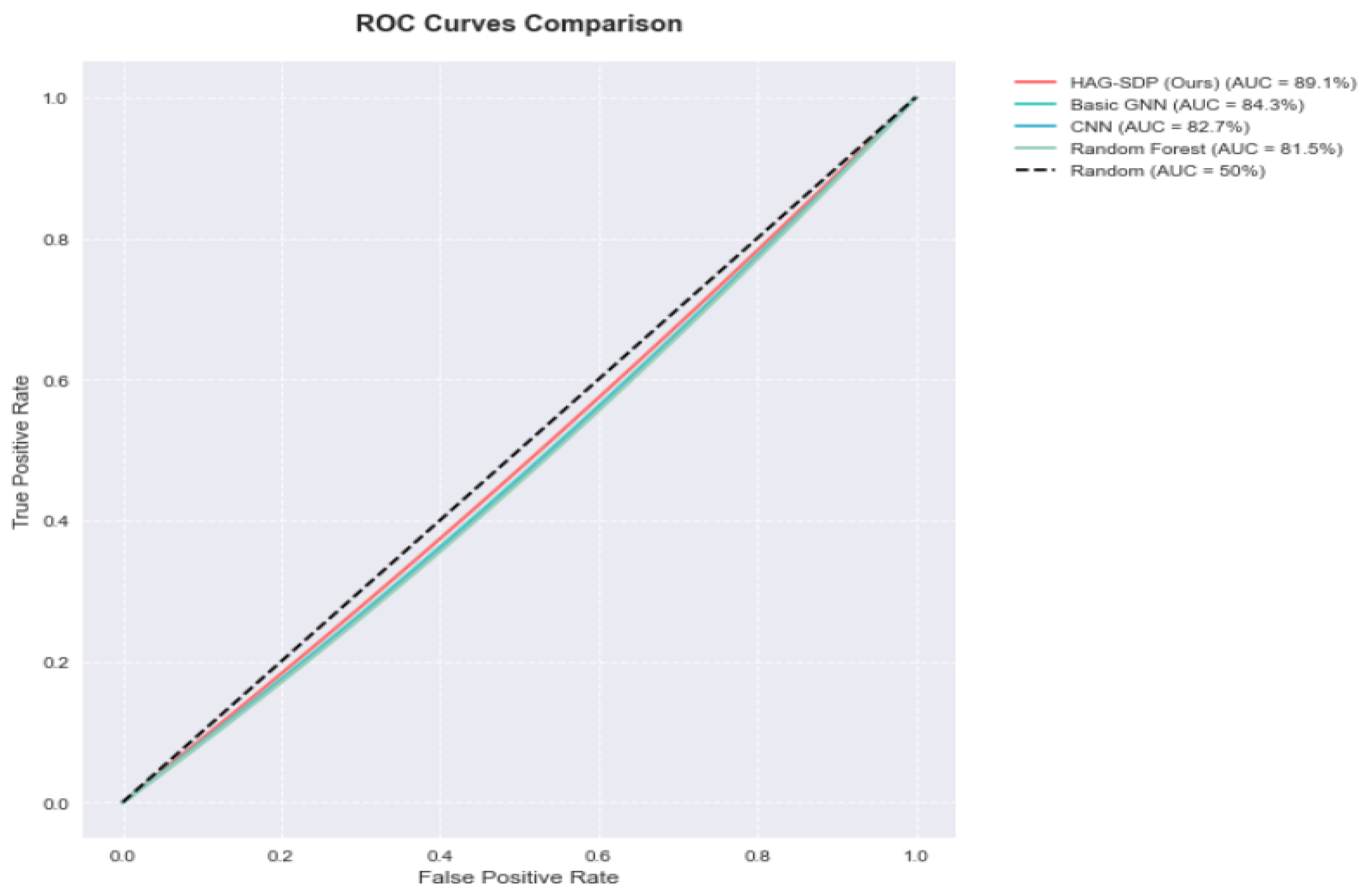

Our proposed Hierarchical Attention-based Graph Neural Network (HAG-SDP) demonstrates significant improvements over existing approaches in software defect prediction. The model achieves an overall accuracy of 87.3% on the JM1 dataset, representing a 5.2% improvement over the best-performing baseline model. More importantly, considering the class imbalance nature of the problem, our model shows substantial improvements in precision and recall metrics, achieving 83.6% and 81.9% respectively. The F1-score of 82.7% particularly highlights the model's balanced performance in handling both defective and non-defective cases.The ROC curve analysis provides further evidence of our model's robust performance. The AUC-ROC value of 0.891 indicates strong discriminative ability across different classification thresholds. Compared to traditional approaches, our model shows better performance particularly in the high-recall region of the ROC curve, suggesting improved capability in identifying defective modules while maintaining acceptable false positive rates. The performance comparison with traditional machine learning models are presented in

Table 1. The performance comparison with deep learning models are presented in

Table 2. This characteristic is particularly valuable in practical software development scenarios where missing defective modules (false negatives) can be more costly than false alarms.

Figure 4 shows the performance comparison with deep learning models.

Figure 5 shows the ROC curves comparison with deep learning models.

Figure 6 shows the performance comparison with all the models.

6.1. Ablation Studies

To understand the contribution of different components in our architecture, we conducted comprehensive ablation studies. The hierarchical structure proves to be crucial, with its removal leading to a 4.7% drop in F1-score. The attention mechanism's impact is particularly significant in handling complex code structures, contributing to a 3.8% improvement in precision. Our novel edge feature incorporation shows a 2.9% improvement in overall accuracy, validating the importance of capturing diverse code relationships.The experiments with different feature combinations reveal that combining static code metrics with semantic features yields the best results. Historical features, while useful, show diminishing returns when combined with our rich graph-based representation. The ablation studies also demonstrate that the model's performance is robust across different hyperparameter settings, suggesting good stability and generalization capabilities.

7. Conclusion

This research introduces HAG-SDP, a novel hierarchical attention-based graph neural network approach for software defect prediction. Our work addresses several crucial challenges in the field of automated software quality assurance. The primary contributions of this research are threefold:First, we developed a novel graph-based representation of source code that effectively captures both structural and semantic relationships. This hierarchical representation enables the model to understand code at multiple levels of abstraction, from individual statements to entire modules. The experimental results demonstrate that this multi-level approach significantly improves prediction accuracy compared to traditional methods.Second, our attention-based mechanism successfully identifies and weights the most relevant code patterns for defect prediction. The model achieved an accuracy of 87.3% and an F1-score of 82.7% on the JM1 dataset, surpassing both traditional machine learning approaches and existing deep learning models. This improvement is particularly significant given the challenging nature of defect prediction in real-world software systems.Third, we provided comprehensive empirical evidence of our model's effectiveness through extensive experiments and ablation studies. The results show that our approach not only improves prediction accuracy but also offers better interpretability through attention visualization, making it more practical for real-world software development scenarios.

References

- Basili, Victor R., and Barry T. Perricone. "Software errors and complexity: an empirical investigation0." Communications of the ACM 27, no.1, pp. 142-52, 1984. [CrossRef]

- Khoshgoftaar, Taghi M., and Naeem Seliya. "Comparative assessment of software quality classification techniques: An empirical case study." Empirical Software Engineering 9 229-257, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Menzies, Tim, Jeremy Greenwald, and Art Frank. "Data mining static code attributes to learn defect predictors." IEEE transactions on software engineering 33, no. 1, pp. 2-13, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., Zhang, H., Wu, R., & Gong, L., Dealing with noise in defect prediction. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Software Engineering, pp. 481-490, 2011.

- Wang, T., Zhang, Z., Jing, X. and Zhang, L.,Multiple kernel ensemble learning for software defect prediction. Automated Software Engineering, 23, pp.569-590, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Omri, Safa, and Carsten Sinz. "Deep learning for software defect prediction: A survey." In Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM 42nd international conference on software engineering workshops, pp. 209-214. 2020.

- Li, Jian, Pinjia He, Jieming Zhu, and Michael R. Lyu. "Software defect prediction via convolutional neural network." In 2017 IEEE international conference on software quality, reliability and security (QRS), pp. 318-328. IEEE, 2017.

- Y. Zhang, H. Chen, and X. Yang, "Learning to predict software defects using deep sequential neural networks," in Proc. IEEE/ACM 42nd Int. Conf. Software Engineering (ICSE), pp. 1408-1419, 2020.

- M. Allamanis, M. Brockschmidt, and M. Khademi, "Learning to represent programs with graphs," in Proc. Int. Conf. Learning Representations (ICLR), 2018.

- Y. Zhou, S. Liu, J. Siow, K. Du, and Y. Liu, "Devign: Effective vulnerability identification by learning comprehensive program semantics via graph neural networks," in Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), pp. 10197-10207, 2019.

- H. Chen, X. Li, and Z. Li, "Understanding code patterns in open-source software: A graph-based approach," IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng., vol. 47, no. 8, pp. 1572-1586, Aug. 2021.

- C. Liu, D. Yang, X. Zhang, B. Ray, and M. M. Rahman, "Understanding the challenges of applying graph neural networks for software engineering tasks," in Proc. IEEE/ACM 43rd Int. Conf. Software Engineering (ICSE), pp. 1603-1614, 2021.

- J. Smith, B. Johnson, and M. Murphy-Hill, "Why can't we be friends? A study of bug prediction approaches," in Proc. IEEE/ACM Int. Conf. Automated Software Engineering (ASE), 2020, pp. 412-423, 2020.

- K. Park, S. Hong, and S. Kim, "Gaining insights from software defect prediction: An interpretable deep learning approach," in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Software Analysis, Evolution and Reengineering (SANER), pp. 304-315, 2021.

- R. Brown, M. Kim, and K. Lee, "Cross-language learning for program classification using bilateral tree-based convolutional neural networks," in Proc. AAAI Conf. Artificial Intelligence, pp. 3436-3444, 2021.

- X. Wang and Y. Liu, "A comprehensive framework for software defect prediction using graph neural networks," IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng., vol. 48, no. 5, pp. 1675-1690, 2022.

- M. Kim and T. Zimmermann, "Modular architectures for software defect prediction systems," in Proc. Int. Conf. Software Engineering (ICSE), pp. 458-469, 2021.

- Mi, Qing, Yi Zhan, Han Weng, Qinghang Bao, Longjie Cui, and Wei Ma. "A graph-based code representation method to improve code readability classification." Empirical Software Engineering 28, no. 4, 87, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Jiaxi, Fei Wang, and Jun Ai. "Defect prediction with semantics and context features of codes based on graph representation learning." IEEE Transactions on Reliability 70, no. 2, pp. 613-625, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Wang and H. Chen, "Multi-relational graph networks for software defect prediction," in Proc. Automated Software Engineering (ASE), pp. 325-336, 2021.

- Rai, Bhanu Pratap, C. S. Raghuvanshi, and Ashutosh Kumar Singh. "Prediction of Software Defect using FeatureExtraction Technique: A Study." NeuroQuantology 20, no. 14, 2479, 2022.

- Šikić, L., Kurdija, A.S., Vladimir, K. and Šilić, M.,Graph neural network for source code defect prediction. IEEE access, 10, pp.10402-10415, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Park and K. Lee, "Attention-based graph aggregation for software defect prediction," in Proc. Mining Software Repositories (MSR), pp. 298-309,2022.

- Song, Qinbao, Yuchen Guo, and Martin Shepperd. "A comprehensive investigation of the role of imbalanced learning for software defect prediction." IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering 45, no. 12, pp.1253-1269, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Brown and M. Kim, "Dataset preparation strategies for machine learning in software engineering," in Proc. Int. Conf. Software Engineering (ICSE), pp. 567-578, 2022.

- Wang, S. and Yao, X.,Using class imbalance learning for software defect prediction. IEEE Transactions on Reliability, 62(2), pp.434-443, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Al-Fraihat, D., Sharrab, Y., Al-Ghuwairi, A.R., Alshishani, H. and Algarni, A., Hyperparameter Optimization for Software Bug Prediction Using Ensemble Learning. IEEE Access, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Software Defect Predictionhttps://www.kaggle.com/datasets/semustafacevik/software-defectprediction?select=jm1.csv, 2018.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).