1. Introduction

Purpose of This Research

In human interaction, events like conflicts may come as a surprise to those involved. But arguably, they often follow a hidden script. Social systems like families or work-teams have recurring communication flows, in other terms: they follow their characteristic patterns. Watzlawick defines communication pattern as a stochastic process that “refers to the lawfulness inherent of symbols or events” [

1]. A lawfulness that he likes to a composer’s tendency to use a certain sequence of notes rather than another. These patterns are what we perceive as “typical” for a certain composer. We tend to be surprised if the pattern is broken, we would for instance be stunned if Haydn had written a Lento following an Adagio. At the same time, when we are part of a social system, we tend to be oblivious to the lawfulness in our own communication, as Watzlawick argues: “we are particularly unaware of the rules being followed in successful, and broken in disturbed, communication”. Watzlawick puts the recognition of communication patterns at the core of his theory: “the search for pattern is the basis for all scientific investigation. Where there is pattern there is significance - this epistemological maxim also holds for the study of human interaction”.

If events in teams, such as conflicts, follow an inherent lawfulness of team interaction, as Watzlawick suggests, can we not apply machine learning to detect the pattern prior to such events and thus forecast their occurrence? This would have a variety of potential applications: to give a meeting moderator a lead time to constructively work with an upcoming conflict before the heat goes up. It could also give a sales agent an indication that he is about to lose a customer’s attention in a sales meeting, to name just two.

The connection between individual emotion and group phenomena is however not trivial to establish. In Luhmann’s theory of social systems, individuals and organizations are separate, but connected autopoietic systems [

2]. An idea that has been built upon by other sociologists [

3,

4]. In this view, a causal connection between the emotion of an individual and a group event cannot be a priori established. On the other hand, there is little doubt that emotions shared by individuals in groups are of particular relevance: “emotions have been proposed to play a role in the development and maintenance of interpersonal bonds, group cohesion and group identity; the division of responsibilities and the negotiation of power roles among group members”[

5]. This research approaches the question in how far emotions of one or several individuals can be predicted by the interaction by two or more people. In how far these individual emotions can be tied to group phenomena such as conflicts, joy or even meeting success, requires further research.

Research Questions

The research questions pursued in this research were:

How accurately can a machine learning model forecast emotional reactions based on the patterns in human interaction?

How does the accuracy of predictions change, depending on how far ahead the emotions are that are predicted?

State of the Art

Previous research has tried to predict individual emotions conveyed through the tone of voice and/or through facial expressions. With the evolvement of deep learning, speech emotion recognition (SER) is becoming ever faster in recognizing a speaker's emotional state. At the same time, they can do so using increasingly smaller snippets of audio data. [

6]

Modern SER transformer models like Wav2Vec 2.0 [

7] were trained to detect the emotional state of an audio stream by using self-supervised learning and can classify a wide range of emotions of individuals. While classifying audio data within fractions of a second might already sound like predicting the following emotional state, it arguably is still just a very fast classification.

There is significantly less research to be found on forecasting the occurrence of emotions. [

8] use individual level utterances in a dialogue setting and attempts to predict the emotional state of the same person a certain amount of time steps in the future. While this setup seems promising, our goal is to take forecasting to group level. We envisage a system that takes in the full audio stream of a conversation and accurately forecasts group level-phenomena. The merit of this approach compared to the utterance level approach would be a system that is not bound to the behavior of singular people but the flow of conversation itself. Following Watzlawick’s theory, a system that adheres to the inherent lawfulness of communication could potentially offer greater stability for forecasting.

2. Materials and Methods

Datasets

Examining 32 different datasets, we found an inherent scarcity of labelled data that is eligible to use for our machine learning use-case [

9]. There are many annotated datasets for speech emotion recognition to be found, however, they are very rarely in dialogue settings where subjects are responding to each other's utterances, as required for this research. Out of these 32 datasets, two were found to be feasible for this study: IEMOCAP and MELD.

IEMOCAP

The IEMOCAP dataset [

10] provides exactly this with 151 audio-visual recordings of English spoken dialogue. These recordings total approximately 12 hours of audio, performed by five male and five female actors in dyadic sessions designed to emulate natural conversational flow and authentic emotional expressions. The dataset contains 10,039 utterances in total [

11]. While the dataset specifies the gender of the actors, it does not provide details about their age or ethnicity. The dataset also includes visual data from facial motion capture, but our study exclusively focuses on the audio component. The dialogues can be analyzed either as complete conversations or as pre-segmented utterances of varying lengths, each annotated by at least three evaluators into nine emotional categories: anger, happiness, excitement, sadness, frustration, fear, surprise, other and neutral state. This selection aims to capture conversational dynamics by representing positive, negative, and neutral emotional directions. Since the distribution of emotions in the dataset was not equally balanced, we applied undersampling to ensure that the selected emotions were represented more evenly. As a result, our reduced dataset includes approximately 2,900 annotated utterances.

MELD

The Multimodal Emotion Lines Dataset (MELD) dataset provides a rich resource for emotion recognition tasks with approximately 13,000 utterances from 1,433 multi-party conversations in the TV series Friends. Unlike datasets focused on dyadic interactions, MELD captures natural, multi-party dialogues, enabling the study of conversational dynamics in group settings.

Each utterance in the dataset is annotated into one of seven emotion categories: neutral, anger, disgust, sadness, joy, surprise, and fear, with multiple annotators ensuring reliability. Additionally, MELD provides the audio, text transcripts, and video recordings of the interactions, although our study exclusively utilizes the audio data to focus on tonal expressions.

The conversations in MELD are segmented into variable-length utterances, maintaining the natural flow of dialogue and allowing for contextually grounded emotion detection. This dataset is suitable for evaluating emotion prediction models in conversational contexts, as it includes transitions between emotional states that mimic real-world dialogue scenarios. For our purposes, we reduce the annotation categories to three: happy, sad, and neutral, aligning with the positive, negative, and neutral conversational flows central to our research objectives. However, there is one major disadvantage with MELD: It also includes audience laughter, which might cloud the detection of audio patterns. Therefore, the focus in this study was to use the IEMOCAP dataset.

Feature Extracting and Preprocessing

Handcrafted Audio Features

Audio data can be analyzed through various well-established techniques to extract key information. Commonly used features include pitch, energy, Mel Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCC), and Mel Filter Bank (MFB) coefficients. These methods are widely recognized for their reliability and effectiveness in capturing the acoustic properties of audio and classifying them. [

8]

While these handcrafted features remain valuable, advancements in self-supervised deep learning models have enabled the efficient extraction of emotion-relevant information directly from raw audio signals.

Latent Features of Self-Supervised Models

Self-supervised models excel in representing audio because they extract meaningful latent features directly from raw waveforms. These features capture subtle variations in pitch, tone, and rhythm, which are key for understanding emotional cues. By learning representations in an unsupervised manner, such models effectively generalize across tasks, including emotion detection and forecasting.

Wav2Vec 2.0 [

7] is a state-of-the-art self-supervised deep learning model designed for processing raw audio data. It learns meaningful representations of audio by transforming raw waveforms into feature-rich embeddings, which can then be used for various downstream tasks, such as speech recognition or emotion detection. The model consists of a feature extractor that maps audio input into a high-dimensional latent feature space. A task-specific fine-tuned head is then utilized to interpret these features for downstream applications, such as emotion classification or transcription, ensuring optimal performance across diverse tasks.

Contrastive models, such as Microsoft CLAP [

12] or AudioCLIP [

13], further enhance flexibility by aligning audio features with semantic labels. These models enable zero-shot classification, allowing for the prediction of emotional states even without extensive task-specific fine-tuning. This capability is particularly valuable when labeled data is limited.

These embeddings act as compact representations of the audio signal, preserving its essential features while reducing dimensionality. This balance allows downstream classifiers to perform robustly even with lightweight architectures, making such embeddings foundational for predictive tasks.

Preprocessing SER Datasets for Forecasting

To prepare the IEMOCAP and MELD datasets for emotion forecasting, we extracted audio segments corresponding to a fixed time window (which we refer to as forecasting window) before each annotated utterance. We chose the 10-second forecasting window because it allows us to capture a broader context leading up to the emotional event. Unlike other approaches that prioritize real-time prediction speed, our focus was on forecasting the emotional event ahead of time, and thus, we were not bound by strict time limitations for the window length. However, to avoid overloading the embedding model with excessive data, we decided on a 10-second window, as it typically includes at least two or three utterances in the dialogue. This approach enables the study of how interaction patterns evolve and influence emotional states over time.

Shifting the Forecasting Windows

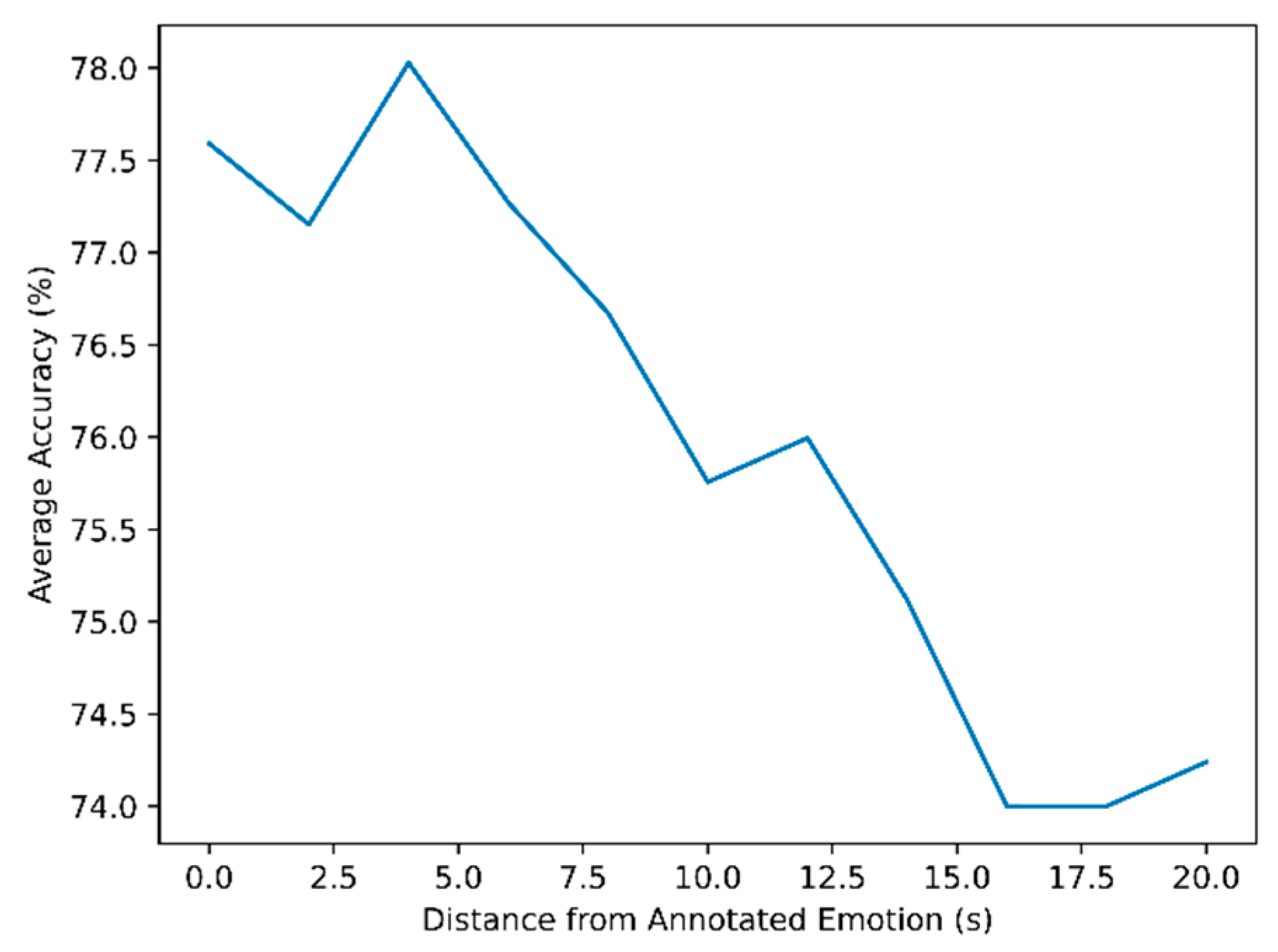

Additionally, we tested shifting the forecasting window further back, allowing the recording to take place up to 20 seconds before the annotated event. By shifting the window in steps of 2 seconds, we explored how well we could forecast the emotional event based on increasing distances to the recorded audio.

It’s important to reemphasize that our approach focused on training the model on the embeddings generated from the entire conversational context, also including silence or half sentences, rather than on individual utterances. This aligns with our research hypothesis that emotions arise from interaction, rather than isolated moments, highlighting the importance of conversation dynamics in emotional expression.

To illustrate our training data, let the annotated events be

For each -th event, we create shifted windows as follows:

The shifted windows generate a new dataset:

represents the audio segment corresponding to the -th event. is the label associated with .

● For : The training dataset consists of windows immediately

preceding the event.

● For : The training dataset shifts the windows 2 seconds further

into the past, and so on.

This creates 11 distinct datasets of 10 second recordings of audio (one for each in .

For each dataset we trained a model individually providing it only with the necessary information for this specific time delay from the emotional event. We tested the performance of the models by performing a 5-fold cross validation. We recorded the accuracies of the validation set and averaged them to get the overall accuracy.

Zero-Shot Forecasting Using Contrastive Models

As previously discussed, contrastive models like Microsoft CLAP show potential for zero-shot audio classification without extensive task-specific training, even though their reliability is limited in certain contexts.

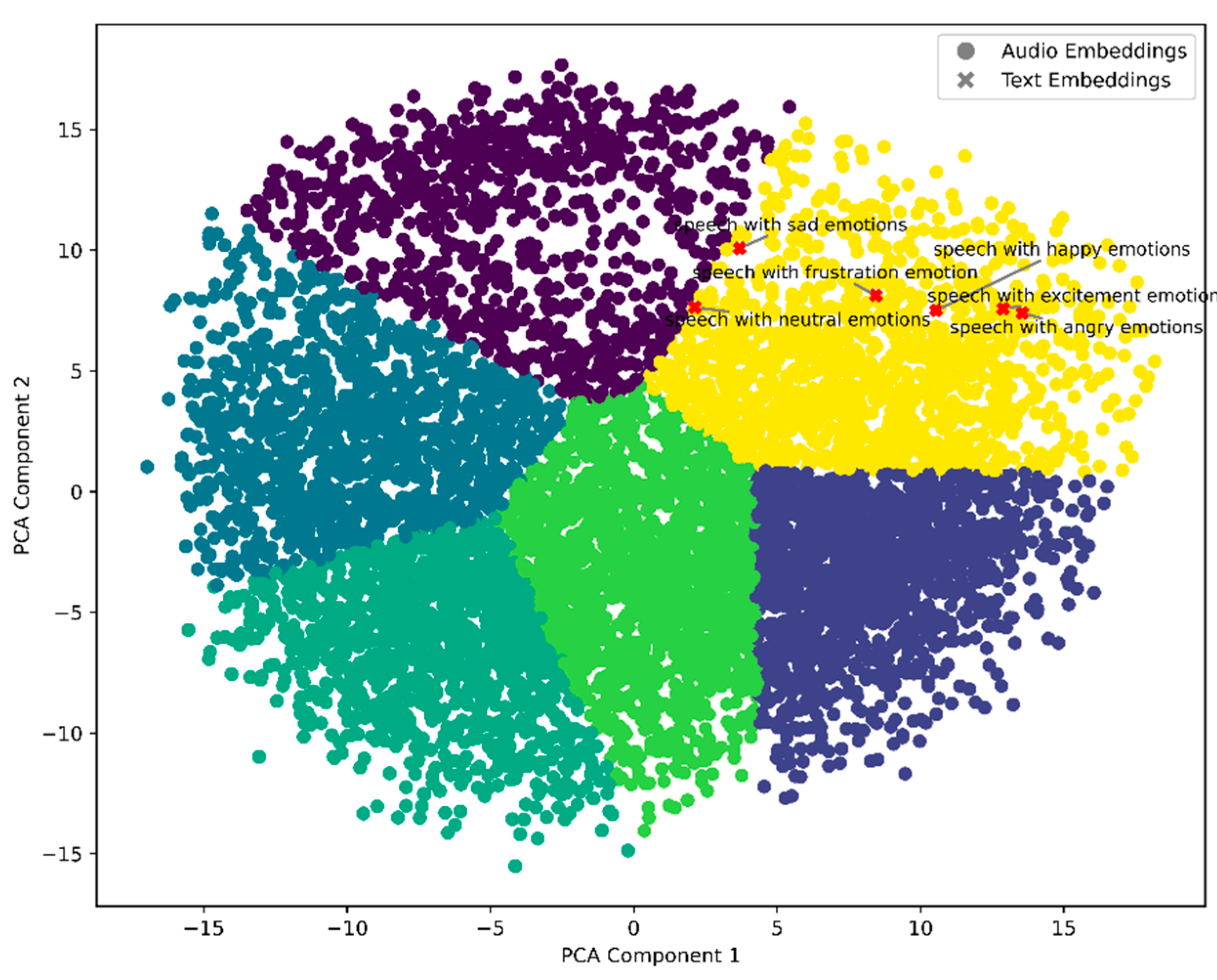

Figure 1 illustrates the PCA projection of CLAP embeddings of all IEMOCAP dataset utterances into a 2D space, combined with K-means clustering to group the features. While the embeddings exhibit some degree of spatial separation, closer analysis using Cosine distance reveals that the clusters are not well-defined enough to support reliable classification of emotional states. This is evident in the overlap of clusters and the lack of clear boundaries between emotional categories. Even when text embeddings (shown as red markers) are overlaid, they do not demonstrate sufficient alignment with the clusters to suggest robust predictive utility.

These findings suggest that while contrastive models might provide compact and meaningful embeddings, their representation might be too complex for effective classification using only the Cosine distance. Additionally, selecting the appropriate text prompt proves challenging, further complicating the ability to accurately map embeddings to emotional labels. This highlights the need for further refinement, such as integrating a custom supervised model to map embeddings to emotional reaction labels to make these embeddings viable for forecasting.

Forecasting – a Supervised Approach

The experiments with the audio embedding capabilities of Microsoft CLAP and AudioCLIP resulted in mixed results. These models, being general-purpose contrastive audio-text pretraining frameworks, were not fine-tuned on emotion-specific datasets. As a result, their embeddings lacked the specificity required to reliably distinguish between nuanced emotional states in our experiments. While promising for zero-shot classification, CLAP’s performance highlighted the need for more tailored solutions when applied to emotion forecasting.

To overcome these challenges, we leveraged a Wav2Vec 2.0 model fine-tuned on IEMOCAP dataset by SpeechBrain for feature extraction [

14]. This model generates 768-dimensional vector embeddings from raw audio, capturing rich latent features. Using these embeddings as input, we designed and trained a simple but effective Fully Connected Deep Neural Network (FC-DNN) to forecast emotional reactions.

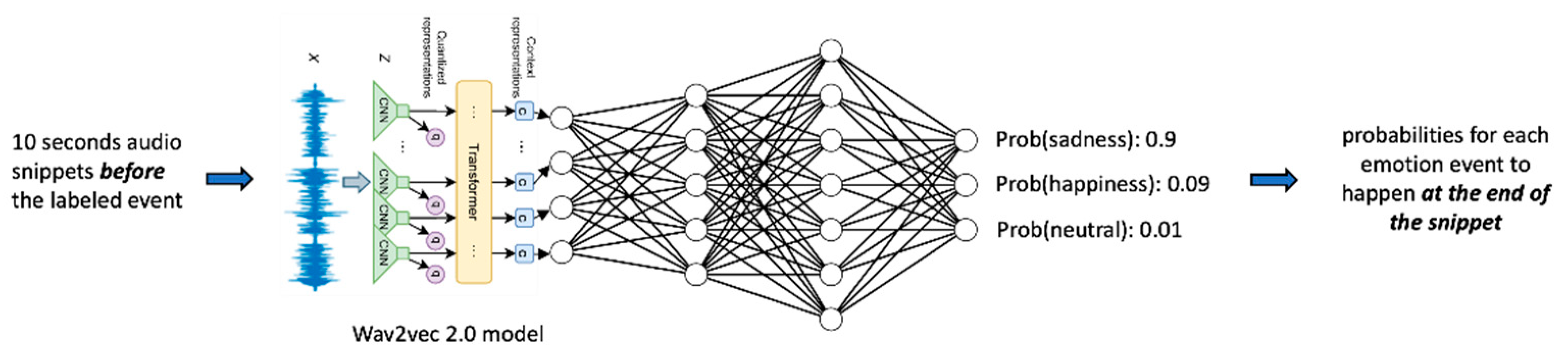

The pipeline and model architecture we developed for this purpose is illustrated in

Figure 2. It reflects a systematic approach, incorporating preprocessing, feature extraction, and an FC-DNN model inference.

The architecture of the FC-DNN includes an input layer that accepts 768-dimensional vector embeddings, 4 hidden linear layers with 265 neurons each, with dropout (0.1) and batch normalization applied to mitigate overfitting and stabilize training. The output layer provides multi-class classification scores using Softmax for the specified emotion classes (e.g., excitement, sadness, neutral).

We evaluated the performance of our model using architectures with increased complexity, such as additional layers and neurons. Surprisingly, we discovered that the lightweight configuration of our network achieved comparable results, indicating its efficiency and suitability for this task.

3. Experiments and Results

4. Discussion

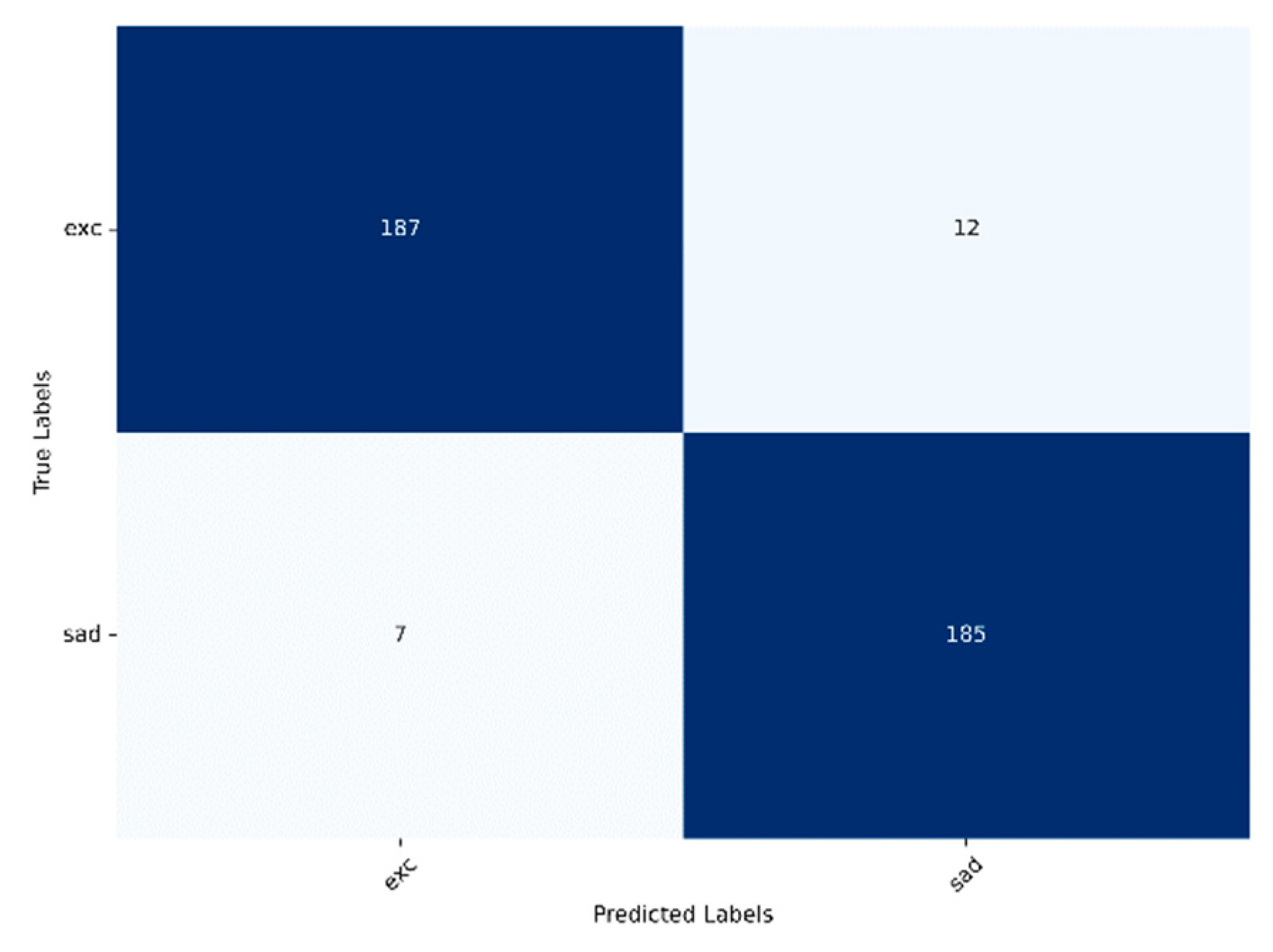

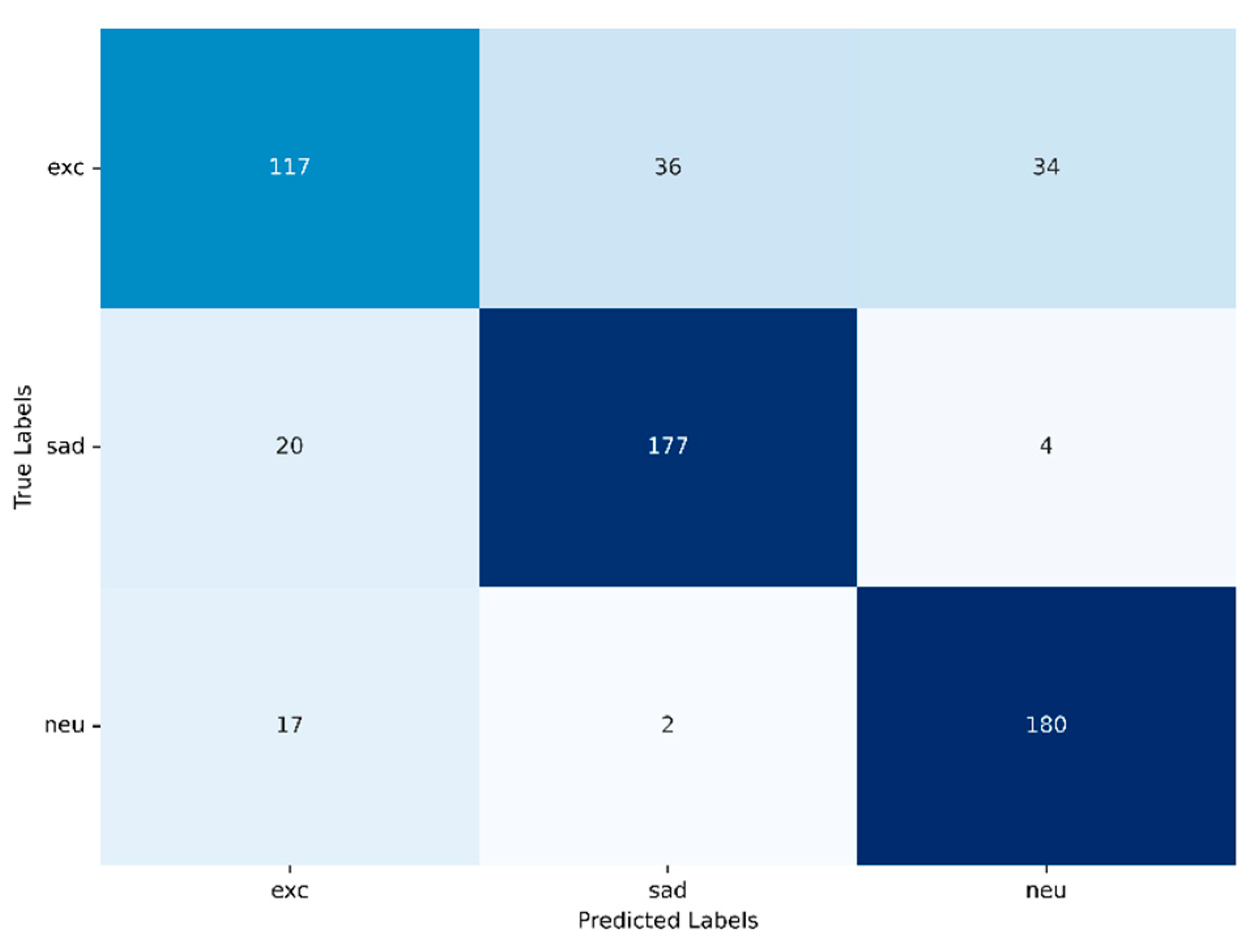

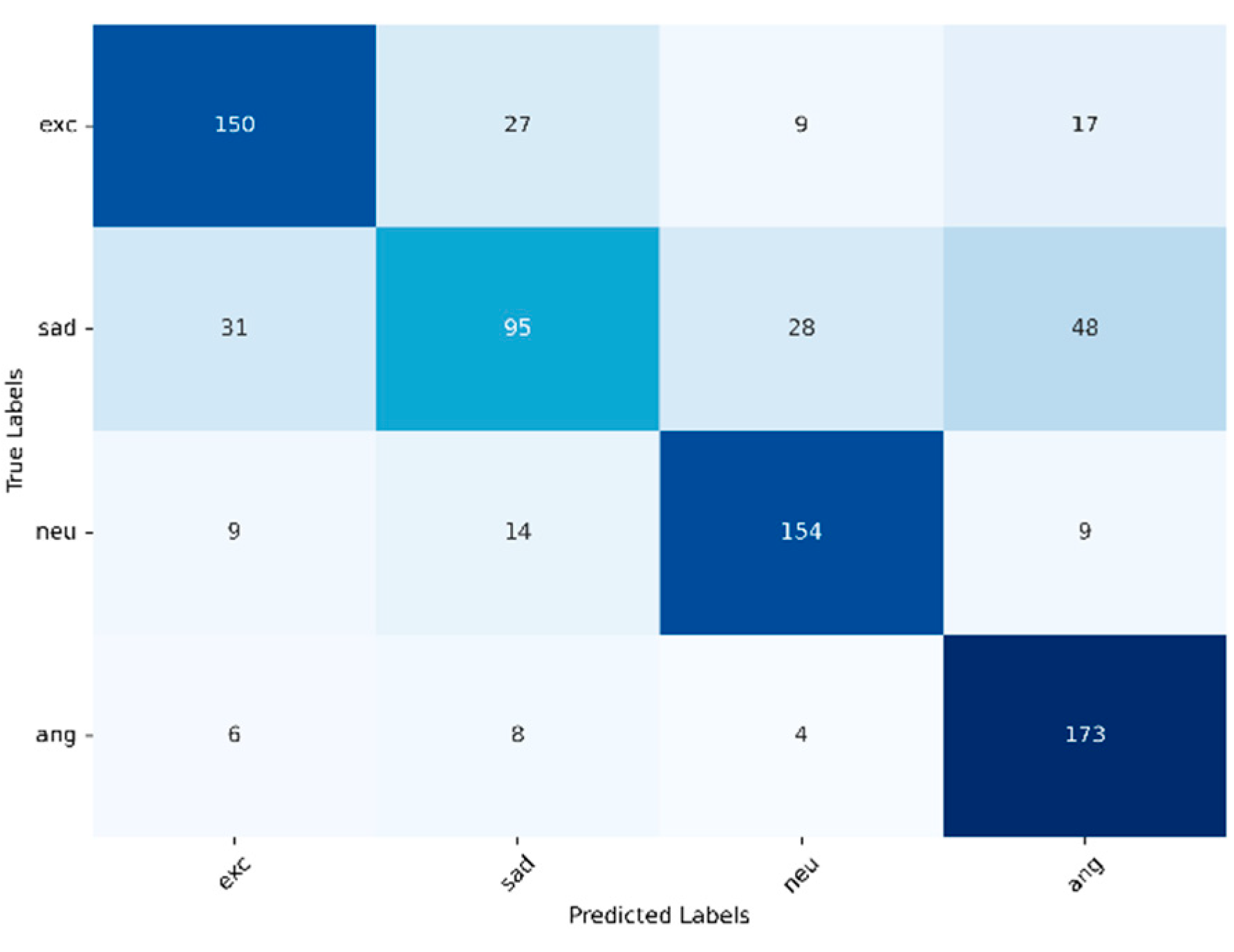

Regarding RQ1, the research based on the IEMOCAP dataset shows that emotional reactions can be forecasted with the approach introduced here. The accuracy of the forecast drops with the number of emotions that are to be considered. When using three emotional states, sadness, excitement and neutral, the cross-validation mean accuracy reaches 78.80 %. When adding a fourth emotional state (angry) the cross-validation mean accuracy drops to 72.14%. These results indicate that the embedding model’s representations become less distinguishable as the number of emotions to be forecasted grows.

When forecasting four emotions, sadness and excitement are often mixed by the model. This misclassification occurs quite uniformly, suggesting that there are either similarities in the patterns that lead to these emotions or in the way they are represented by the model. Additionally, many samples that should be forecasted as sadness are instead categorized as anger. This further emphasizes the difficulty the model faces in distinguishing patterns leading to sadness from those leading to other emotional states.

With regard to RQ2, the findings show that the accuracy of forecasts decreases with the time span between annotation and input data. In our research the accuracy dropped in a near-linear fashion from 78% to 74% when going back 20 seconds. This suggests that temporal proximity plays a significant role in the model's ability to predict the label. Information from distant windows carries less relevance or is harder for the model to be utilized effectively. A similar effect would likely be observed in human judgment: as an emotional reaction, such as a conflict, approaches, it becomes increasingly apparent to an external observer what is likely to occur. This observation further suggests that the machine learning model exhibits consistent and non-erratic behavior.

5. Conclusions

It can be surmised that forecasting emotions based on human interaction is a promising path for further research. This is backed up by Watzlawick’s communication theory and coaching practice as well as the initial experiments presented here The accuracy of the results depends on the number of emotions to be forecasted and how far ahead in time the forecast takes place. These experiments further indicate that using the embedding models as described here is a promising path to reduce the complexity of audio signals while pertaining the relevant information for emotion forecasting.

Forecasting just two different emotional reactions 10 or 20 seconds ahead of time might already find interesting practical use cases: For example, to indicate whether a conflict is about to occur. Forecasting this should require only two classes: The emotional signature of a conflict, and a neutral state. More research would be required to confirm this hypothesis.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study is its reliance on only one dataset, which is rooted in North American culture. More research with groups of different sizes in different social and cultural contexts could lead to further insights. Furthermore, limited time and resources have, thus far, restricted the exploration of a wider range of model types and experimental settings.

6. Patents

The following patent application has been filed at the US Patent Office as a result of this work: 63/654,513.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Thomas Spielhofer; methodology, Kristof Maar and Jakob Prager; software, Kristof Maar and Jakob Prager; data curation, Kristof Maar and Jakob Prager; validation, Thomas Spielhofer; writing, Thomas Spielhofer, Kristof Maar and Jakob Prager; visualization, Kristof Maar and Jakob Prager; project administration, Thomas Spielhofer; funding acquisition, Thomas Spielhofer. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Sunshine in Interaction FlexCo, Vienna, Austria.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We would particularly like to thank Ashish Bansal for his invaluable feedback. We would also like to thank the IEMOCAP dataset provider and the entire team at Sunshine in Interaction for their encouragement and support, with special thanks to Lorenz Glatz.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

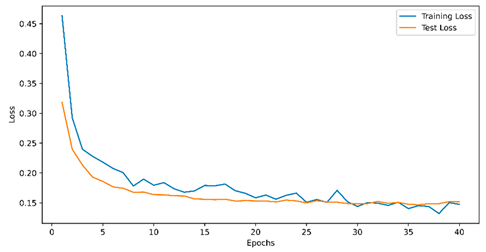

Appendix A. Train and Evaluation Losses

Table 4.

final model training with two classes.

Table 4.

final model training with two classes.

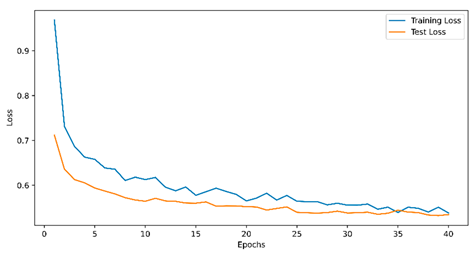

Table 5.

final model training with three classes.

Table 5.

final model training with three classes.

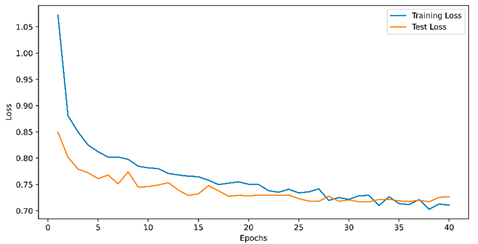

Table 6.

final model training with four classes.

Table 6.

final model training with four classes.

Appendix B. Infrastructure Used for This Research

Appendix B.1: Hardware Environment

Platform: Google Colab Pro

Operating System: Linux-based environment (Ubuntu 22.04 LTS)

GPU: NVIDIA Tesla T4, 16 GB GDDR6 VRAM

CPU: 8 vCPUs (Intel(R) Xeon(R) @ 2.20GHz)

RAM: 51 GB

Software: Conda-managed environment with pip-installed dependencies

Appendix B.2: Software Environment

Python, Version 3.10

Core Libraries: numpy, pandas, matplotlib, scikit-learn, torch, torchvision, keras, librosa, soundfile, tqdm, google-colab

Specialized Libraries: funasr, modelscope, hyperpyyaml, ruamel.yaml, tensorboardX, transformers, huggingface-hub, umap-learn, torchlibrosa, sentencepiece

References

- Watzlawick, P.; Bavelas, J.B.; Jackson, D.D. Pragmatics of Human Communication: A Study of Interactional Patterns, Pathologies and Paradoxes; W. W. Norton, 2011; ISBN 978-0-393-70722-9.

- Luhmann, N. Organisation und Entscheidung: 227. Sitzung am 18. Januar 1978 in D??sseldorf; 1978; ISBN 978-3-322-91079-0.

- Simon, F.B. Einführung in Die Systemische Organisationstheorie; Carl-Auer Verlag, 2021; ISBN 3-8497-8348-0.

- Wimmer, R. Die Neuere Systemtheorie Und Ihre Implikationen Für Das Verständnis von Organisation, Führung Und Management. Unternehmerisches Management. Herausforderungen und Perspektiven 2012, 7–65.

- van Kleef, G.A.; Fischer, A.H. Emotional Collectives: How Groups Shape Emotions and Emotions Shape Groups. COGNITION EMOTION 2016, 30, 19

. [CrossRef]

- Purohit, T.; Yadav, S.; Vlasenko, B.; Dubagunta, S.P.; Magimai.-Doss, M. Towards Learning Emotion Information from Short Segments of Speech. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023 - 2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); IEEE: Rhodes Island, Greece, June 4 2023; pp. 1–5.

- Baevski, A.; Zhou, H.; Mohamed, A.; Auli, M. Wav2vec 2.0: A Framework for Self-Supervised Learning of Speech Representations 2020.

- Shahriar, S.; Kim, Y. Audio-Visual Emotion Forecasting: Characterizing and Predicting Future Emotion Using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 14th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2019); IEEE: Lille, France, May 2019; pp. 1–7.

- Ma, Z.; Chen, M.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, W.; Li, X.; Ye, J.; Chen, X.; Hain, T. EmoBox: Multilingual Multi-Corpus Speech Emotion Recognition Toolkit and Benchmark 2024.

- Busso, C.; Bulut, M.; Lee, C.-C.; Kazemzadeh, A.; Mower, E.; Kim, S.; Chang, J.N.; Lee, S.; Narayanan, S.S. IEMOCAP: Interactive Emotional Dyadic Motion Capture Database. Lang Resources & Evaluation 2008, 42, 335–359. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhang, C.; Wu, X.; Woodland, P.C. Estimating the Uncertainty in Emotion Class Labels with Utterance-Specific Dirichlet Priors. IEEE Trans. Affective Comput. 2023, 14, 2810–2822. [CrossRef]

- Elizalde, B.; Deshmukh, S.; Wang, H. Natural Language Supervision for General-Purpose Audio Representations 2024.

- Guzhov, A.; Raue, F.; Hees, J.; Dengel, A. AudioCLIP: Extending CLIP to Image, Text and Audio 2021.

- Ravanelli, M.; Parcollet, T.; Plantinga, P.; Rouhe, A.; Cornell, S.; Lugosch, L.; Subakan, C.; Dawalatabad, N.; Heba, A.; Zhong, J.; et al. SpeechBrain: A General-Purpose Speech Toolkit 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).