Submitted:

28 January 2025

Posted:

28 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 60K10; 90B25

1. Introduction

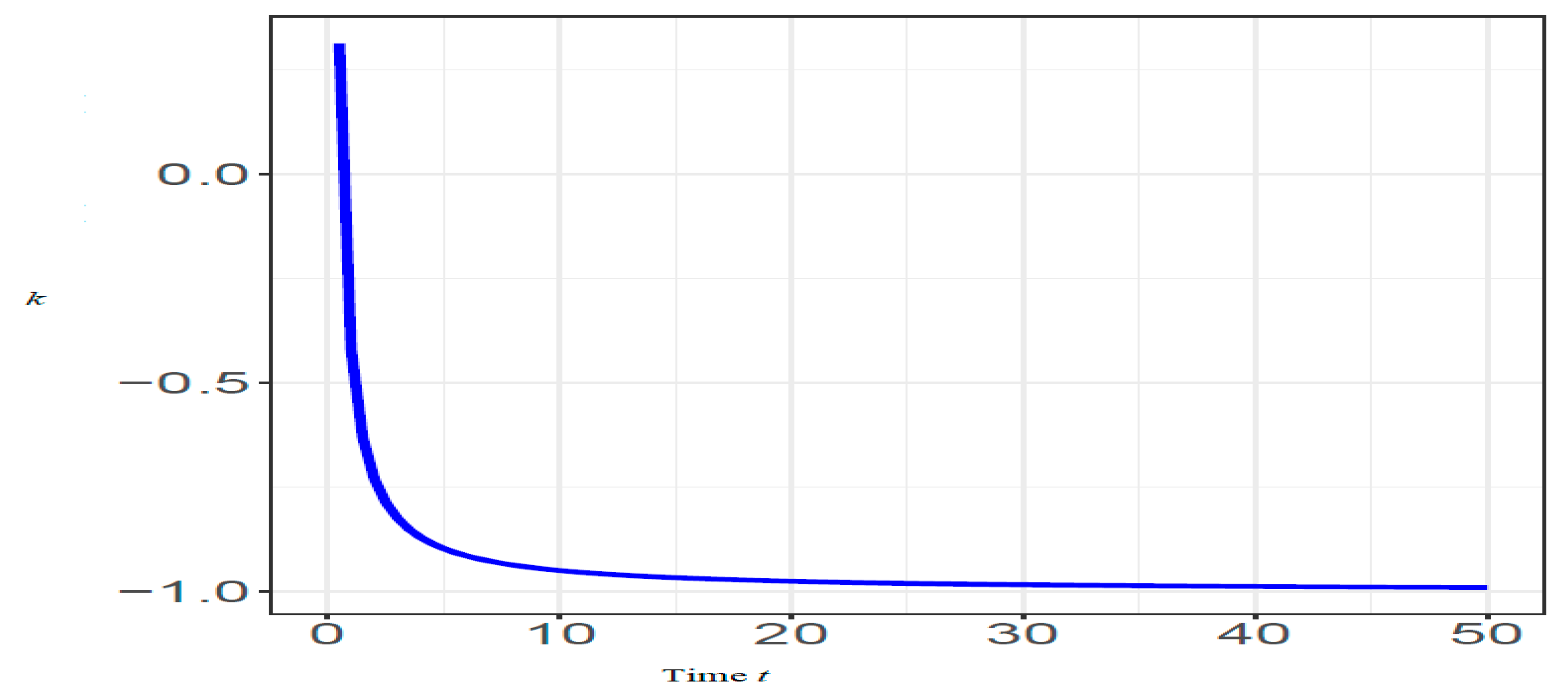

- If , then the aging speed is positive, indicating that the system's risk of failure is increasing over time.

- , then the aging speed is negative, suggesting that the risk of failure is decreasing.

- , then the aging has a constant speed.

- Increasing Failure Rate (IFR): If is increasing, it implies that the system is becoming more prone to failure as time progresses. This is characteristic of "aging" systems where wear and tear accumulate over time.

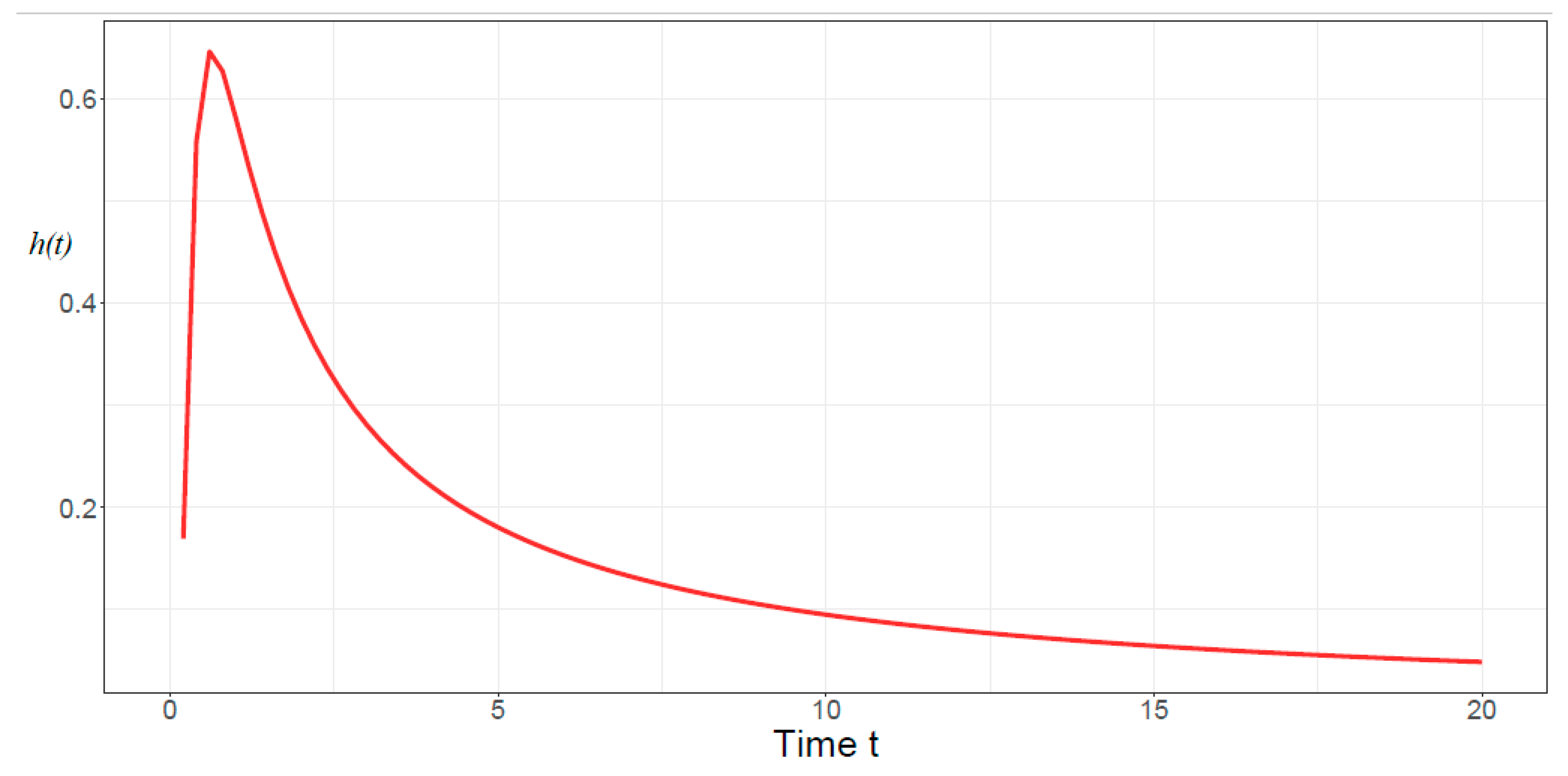

- Decreasing Failure Rate (DFR): If is decreasing, it suggests that the system is becoming less likely to fail as time goes on, which can occur in certain contexts like burn-in periods.

- Constant Failure Rate (CFR): If is constant, it indicates that failures occur uniformly over time, typical of systems with no aging effects, such as in exponential distributions.

2. Some Novel Life Distribution Classes

- (i).

- increasing (decreasing) failure rate ratio property [denoted by , whenever is increasing (decreasing) in , for all .

- (ii).

- increasing (decreasing) reversed failure rate property [denoted by , whenever is increasing (decreasing) in , for all .

- (iii).

- increasing (decreasing) failure rate relative to average failure rate property [denoted as ( , whenever is increasing (decreasing) in (Righter et al. (2009)).

- (iv).

- increasing (decreasing) reversed failure rate relative to average reversed failure rate property [denoted as , whenever is increasing (decreasing) in .

- (i).

- .

- (ii).

- .

- (i).

- if, and only if, is increasing (decreasing) in .

- (ii).

- if, and only if, is increasing (decreasing) in .

- (i).

- If is increasing (i.e. if is IFR) and also log-convex in , then .

- (ii).

- If is decreasing (i.e. if is DFR) and log-concave in , then .

- (iii).

- If is decreasing (i.e. if is DRFR) and log-concave, then .

3. Preservation of and Classes

3.1. Extreme Order Statistics

3.2. Order Statistics

4. Illustrations and Remarks

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Ahmed, M., Lodi, S.H. and Rafi, M.M. (2022). Probabilistic seismic hazard analysis-based zoning map of Pakistan. Journal of Earthquake Engineering, 26(1), 271-306.

- Barlow, R.E. and Proschan, F. (1996). Mathematical theory of reliability. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics.

- Elgohari, H., Ibrahim, M., Yousof, H.M. (2021). A new probability distribution for modeling failure and service times: properties, copulas and various estimation methods. Statistics, Optimization and Information Computing, 9(3), 555-586.

- Finkelstein, M. (2008). Failure Rate Modelling for Reliability and Risk. Springer Science and Business Media.

- Gavrilov, L.A. and Gavrilova, N.S. (2005). Reliability Theory of Aging and Longevity. Handbook of the Biology of Aging, 3-42.

- Jiang, R., Ji, P. and Xiao, X. (2003). Aging property of unimodal failure rate models. Reliability Engineering and System Safety, 79(1), 113-116.

- Kayid, M., and Alshehri, M.A. (2024). Stochastic aspects of reversed aging intensity function of random quantiles. Journal of Inequalities and Applications, 2024(1), 119.

- Kayid, M. and Almohsen, R. A. (2024). Preservation of relative failure rate and relative reversed failure rate orders by distorted distributions. Acta Applicandae Mathematicae, 194(1), 1-15.

- Khan, M.Y., Iqbal, T., Iqbal, T., and Shah, M.A. (2020). Probabilistic modeling of earthquake Interevent times in different regions of Pakistan. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 177(12), 5673-5694.

- Klein, J.P. and Moeschberger, M.L. (2006). Survival Analysis: Techniques for Censored and Truncated Data. Springer Science and Business Media.

- Lai, C.D., and Xie, M. (2006). Stochastic ageing and dependence for reliability. Springer Science and Business Media.

- Marshall, A.W. and Olkin, I. (2007). Life Distributions (Vol. 13). Springer, New York.

- Navarro, J. (2022). Aging Properties. In: Introduction to System Reliability Theory. Springer, Cham.

- Rehman, K., Burton, P.W. and Weatherill, G. A. (2018). Application of Gumbel I and Monte Carlo methods to assess seismic hazard in and around Pakistan. Journal of Seismology, 22, 575-588.

- Rahman, A.U., Najam, F.A., Zaman, S., Rasheed, A. and Rana, I.A. (2021). An updated probabilistic seismic hazard assessment (PSHA) for Pakistan. Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering, 19, 1625-1662.

- Righter, R., Shaked, M. and Shanthikumar, J. G. (2009). Intrinsic aging and classes of nonparametric distributions. Probability in the Engineering and Informational Sciences, 23(4), 563-582.

- Shaked, M. and Shanthikumar, J. G. (Eds.). (2007). Stochastic Orders. New York, Springer, New York.

| Distribution | Survival function | Failure rate | Classes of life distributions |

| IFRR, DFRR | |||

| IFRR | |||

| IFRR, DFRR | |||

| DFRR | |||

| DFRR | |||

| , | DFRR | ||

| , | IFRR | ||

| IFRR |

| Distribution | Distribution function | Reversed failure rate | Classes of life distributions |

| Uniform | IRFRR, DRFRR | ||

| IRFRR, DRFRR | |||

| IRFRR, DRFRR | |||

| DRFRR | |||

| a | IRFRR, DRFRR | ||

| Reversed generalized Pareto |

IRFRR (1 < a < 0), DRFRR (a > 0) |

||

| Half-logistic | , | DRFRR | |

| , | IRFRR |

| 0.4994765579 | 0.665968438 | 0.663175700 | 0.3767697318 | 0.5023596424 | 0.481206988 |

| 0.0262070426 | 0.0349427235 | 0.044638045 | 0.2760793150 | 0.3681057533 | 0.379140003 |

| 0.4268042135 | 0.5690722846 | 0.552286801 | 0.1202760829 | 0.1603681105 | 0.153914794 |

| 0.6347501182 | 0.8463334910 | 0.856256977 | 0.6925388390 | 0.9233851187 | 0.913135678 |

| 0.1062242823 | 0.1416323764 | 0.149734467 | 0.4858971732 | 0.6478628975 | 0.649624370 |

| 0.0020145895 | 0.0026861193 | 0.003775633 | 0.1023574924 | 0.1364766565 | 0.129376481 |

| 0.2021058905 | 0.2694745207 | 0.275697108 | 0.0247524753 | 0.0330033004 | 0.025111582 |

| 0.1250653974 | 0.1667538632 | 0.172243974 | 0.3492021468 | 0.4656028624 | 0.460156151 |

| 0.7632430504 | 1.0176574005 | 0.989129083 | 0.3888029720 | 0.5184039626 | 0.515212907 |

| 0.3313270349 | 0.4417693799 | 0.443656742 | 0.0023579842 | 0.0031439790 | 0.009198710 |

| 0.1914079065 | 0.2552105420 | 0.273083995 | 0.2420603688 | 0.3227471584 | 0.314663449 |

| 0.0222195438 | 0.0296260584 | 0.024211896 | 0.2495684549 | 0.3327579398 | 0.321895450 |

| 0.2309642881 | 0.3079523841 | 0.294108814 | 0.2897415880 | 0.3863221174 | 0.390603567 |

| 0.1388329777 | 0.1851106370 | 0.194475793 | 0.3238376461 | 0.4317835281 | 0.440572804 |

| 0.3314107170 | 0.4418809560 | 0.466452456 | 0.0854768423 | 0.1139691230 | 0.127169177 |

| 0.6436907800 | 0.8582543733 | 0.883448724 | 0.1384879074 | 0.1846505432 | 0.182986975 |

| 0.5571105993 | 0.7428141324 | 0.742170484 | 0.4533983734 | 0.6045311645 | 0.604828181 |

| 0.2168994877 | 0.2891993169 | 0.272227298 | 0.2409825121 | 0.3213100162 | 0.308286976 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).