Submitted:

26 January 2025

Posted:

26 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This paper presents the challenges of building Carolina, a large open corpus of Brazilian Portuguese texts developed since 2020 using the Web-as-Corpus methodology enhanced with provenance and typology concerns (WaC-wiPT). The corpus aims at being used both as a reliable source for research in Linguistics and as an important resource for Computer Science research on language models. Above all, this endeavor aims at removing Portuguese from the set of “low-resource languages”. This paper details Carolina's construction methodology, with special attention to the issue of describing provenance and typology according to international standards, while briefly describing its relationship with other existing corpora, its current state of development and its future directions.

Keywords:

Introduction

1. Fundamentals and Related Works

1.1. Fundamentals

1.2. Related Works

2. Building a Methodology

2.1. The Issue of Provenance

2.2. Defining Typologies

2.3. The Downloading and Preprocessing Stages

2.4. Defining Metadata

3. Current State

4. Conclusion and Future Steps

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Pre-Registration and Equator Network Research Standards

Availability of Data and Material

Code Availability

Notes

- 1

- Carolina Michaëlis de Vasconcelos holds the distinction of being the first woman appointed as a university professor in June 1911, at the Faculty of Letters of Lisbon, although she never taught there. Preferring to remain in Porto, she requested and obtained a transfer to the Faculty of Letters of Coimbra, where she engaged in intensive teaching activity, leading the courses in Romance and Portuguese Philology (Sales, 2025).

- 2

- After naming the corpus, it came to our knowledge that Carolina's father, Dr. Gustav Michaëlis, was a mathematician, which brings an unexpected and felicitous relation to our work.

- 3

- A summarized version of the methodology developed can be found in Sturzeneker et al. (2022).

- 4

- 5

- The TenTen Corpus Family is available for consultation in more than 40 languages, including a corpus of 4 billion tokens for Portuguese (ptTenTen), which includes the European and Brazilian variants. However, the corpora of all these languages are not openly available, being accessible only from the Sketch Engine platform (Jakubíček et al.; 2013) (Wagner et al., 2018).

- 6

- Published in 2017, it contains 2.68 billion tokens that were crawled from the Web in 24 hours, by initially employing queries to a search engine with random pairs of content words, according to the description of its development in Wagner et al (2018). Its importance for advances in Brazilian Portuguese research in multiple areas is illustrated by its employment in NLP model training, as substantiated in Souza et al. (2020).

- 7

- It was developed by the Applied Linguistics and Language Studies Program of the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo (LAEL/PUC-SP) and its version 6.0 of February 2, 2020 is available for online searches at Linguateca. The full corpus can be downloaded upon approval of a requisition form, as long as the user agrees not to distribute or use it for profit purposes. Although the primary sources of the texts are not explicit, there are several works on the construction of the Brazilian Corpus that describe the set of typologies and textual genres that compose it (Sardinha et al., 2010; Vianna; de Oliveira, 2010; de Oliveira; Dias, 2009; de Brito et al., 2007).

- 8

- The Lácio-Web project comprises six corpora, four of which are currently available online (Lácio-Ref, Mac-Morpho, Par-C, and Comp-C) and whose content is described on its website: http://143.107.183.175:22180/lacioweb/descricao.html.

- 9

- In both corpora, the texts were processed after the download for boilerplate removal, duplicates detection, lemmatization and tagging. The complete Web/Dialects corpus is available for purchase, with different selling prices depending on the final license chosen by the user (academic or commercial) at https://www.corpusdata.org/purchase.asp. The NOW Corpus can be accessed free of charge for online searches on its website (https://www.corpusdoportugues.org/now/), but it cannot be downloaded in full.

- 10

- 11

- Available in Portuguese at http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2018/lei/l13709.htm.

- 12

- Raw corpus (‘Corpus Cru’) is a concept created to describe a product derived from the Lapelinc method for building corpora (Namiuti; Santos, 2021), which consists of an unpublicized version of the corpus that holds more information about itself, serving as a mirror of the original sources of the corpus. This notion has been adapted to the methodology used to build Carolina.

- 13

- For the time being, all of the files of this broad typology were extracted from http://www.dominiopublico.gov.br/.

- 14

- 15

- All the tools were developed using Python 3.

- 16

- The tool he developed for his Master's degree at the University of São Paulo is available at https://github.com/mayara-melo/analise-juridica.

- 17

- The token count was achieved with the wc -c linux command, which counts “whitespace-separated tokens”: https://www.gnu.org/software/coreutils/manual/html_node/wc-invocation.html#wc-invocation. It means that these sums will significantly decrease after the preprocessing phase. As well as the number of files, yet we expect it to be in a lower range than the 95% of discarded documents crawled by the brWaC (Wagner et al., 2018), for instance. This same observation is valid for Table 3.

- 18

- 19

- (https://huggingface.co/datasets/carolina-c4ai/corpus-carolina)- cf. full list of all versions available for download at https://sites.usp.br/corpuscarolina/corpus.

References

- Aluísio, S. M. , G. M., Finger, M., Nunes, M. das G. V.; Tagnin, S. E. O. (2003). The Lacio-Web Project: overview and issues in Brazilian Portuguese corpora creation. In D. Archer, P. Rayson, A. Wilson; T. McEnery (Eds.) Proceedings of the Corpus Linguistics 2003 conference (CL2003) (Lancaster, UK, 28-31 March 2003) (pp.

- Aluísio, S. M. , Pinheiro, G. M., Manfrin, A. M., de Oliveira, L. H., Genoves Jr, L. C., & Tagnin, S. E. (2004). The Lácio-Web: Corpora and Tools to Advance Brazilian Portuguese Language Investigations and Computational Linguistic Tools. In M. T. Lino, M. F. Xavier, F. Ferreira, R. Costa; R. Silva (Eds.), LREC 2004 Fourth International Conference On Language Resources And Evaluation. (pp. 1779-1782). European Language Resources Association.

- Bahdanau, D. , Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. (2014). Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409. 0473. [Google Scholar]

- Baroni, M.; Bernardini, S.; Ferraresi, A.; Zanchetta, E. The WaCky wide web: a collection of very large linguistically processed web-crawled corpora. Lang. Resour. Evaluation 2009, 43, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, S. , Baroni M.; Evert, E. (2006). A WaCky introduction. In: M. Baroni; S. Bernardini (eds.). WaCky! working papers on the web as corpus. Bologna: GEDIT, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bick, E. (2000). The parsing system palavras: Automatic grammatical analysis of Portuguese in a constraint grammar framework. Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

- Boos, R., Prestes, K., Villavicencio, A., Padró, M. (2014). brWaC: A WaCky Corpus for Brazilian Portuguese. In: Baptista J., Mamede N., Candeias S., Paraboni I., Pardo T.A.S., Volpe Nunes, M.G. (eds). Computational Processing of the Portuguese Language. PROPOR 2014, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 8775. Springer, Cham. (pp. 201-206). [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, J. A. (2007). Direitos Autorais no Trabalho Acadêmico. REVISTA JURÍDICA DA PRESIDÊNCIA, 9(86), 58-86.

- Clarke, C. L. , G. V., Laszlo, M., Lynam, T. R.; Terra, E. L. (2002). The impact of corpus size on question answering performance. In K. Järvelin, M. Beaulieu, R. Baeza-Yates, S. H. Myaeng (Eds.), Proceedings of the 25th annual international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in information retrieval (pp.

- Costa, A. S. (2024). Um sistema de anotação de múltiplas camadas para corpora históricos da língua portuguesa baseados em manuscritos (Doctoral dissertation). Universidade Estadual do Sudoeste da Bahia.

- Crespo, M. C. R. M.; Rocha, M. L. S. J.; Sturzeneker, M. L.; Serras, F. R.; Mello, G. L.; Costa, A. S.; Palma, M. F.; Mesquita, R. M.; Guets, R. P.; Silva, M. M.; Finger, M.; Paixão de Sousa, M. C.; Namiuti, C.; Martins do Monte, V. . Carolina: a General Corpus of Contemporary Brazilian Portuguese with Provenance, Typology and Versioning Information. Manuscript. September, 2022. C: Preprint, 2023; arXiv:2303.16098v1 [cs. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, M. , Ferreira, M. (2016). Corpus do Português: 1,1 billion words, Web/Dialetics. Brigham Young University: Provo-UT, 2016. Retrieved , 2021, from https://www.corpusdoportugues. 26 May.

- Davies, M. , Ferreira, M. (2018). Corpus do Português: 1,1 billion words, NOW. Brigham Young University: Provo-UT, 2018. Retrieved , 2021, from https://www.corpusdoportugues. 26 May.

- de Brito, M. G. , Valério, R. G., de Almeida, G. P.; de Oliveira, L. P. (2007). CORPOBRAS PUC-RIO: Desenvolvimento e análise de um corpus representativo do português. PUC-Rio. Retrieved May 26, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, L.; Dias, M.C. Compilação de corpus: representatividade e o CORPOBRAS. 7. [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding, arXiv 2019, arXiv:1810. 0 2019, 4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraresi, A.; Bernardini, S.; Picci, G.; Baroni, M. (2010). Web corpora for bilingual lexicography: A pilot study of English/French collocation extraction and translation. In: Using Corpora in Contrastive and Translation Studies. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. (pp. 337-362).

- Fletcher, W. H. (2007). Concordancing the Web: promise and problems, tools and techniques. In M. Hundt, N. Nesselhaulf; C. Biewer (Eds.), Corpus Linguistics and the Web (pp. 25-45). Rodopi.

- Jakubíček, M.; Kilgarriff, A.; Vojtěch, K.; Pavel, R. ; Vít Suchomel. (2013). The TenTen corpus family. In 7th International Corpus Linguistics Conference CL (pp. 125-127).

- Kalchbrenner, N.; Blunsom, P. (2013). In Two recurrent continuous translation models. In Proceedings of the ACL Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), (pp. 1700–1709). Association for Computational Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Z.; Chen, M.; Goodman, S.; Gimpel, K.; Sharma, P.; Soricut, R. (2019). Albert: A lite bert for self-supervised learning of language representations. arXiv:1909.11942.

- Liu, V.; Curran, J. R. (2006). Web text corpus for natural language processing. In D. McCarthy; S. Wintner (Eds.), 11th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. (2019). Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv:1907.11692.

- Namiuti, C.; Santos, J.V. (2021). "Novos desafios para antigas fontes: a experiência DOViC na nova linguística histórica". In: Humanidades digitais e o mundo lusófono. Organização Ricardo M. Pimenta, Daniel Alves. – Rio de Janeiro: Editora FGV, 2021, págs.

- de Sousa, M.C.P. O Corpus Tycho Brahe: contribuições para as humanidades digitais no Brasil. 16, 53. [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, G. M.; Aluísio, S. M. (2003). Córpus Nilc: descrição e análise crítica com vistas ao projeto Lacio-Web. Núcleo Interinstitucional de Lingüística Computacional. Retrieved , 2021, from http://143.107.183.175:22180/lacioweb/publicacoes. 27 May.

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I. (2018). Improving language understanding by generative pre-training. OpenAI. Retrieved , 2021, from https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/openai-assets/research-covers/language-unsupervised/language_understanding_paper. 10 June.

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P. J. (2019). Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. arXiv:1910.10683. from https://www.jmlr.

- Sales, Joana; Sales, Teresa. Carolina Michaëlis de Vasconcelos (1851-1925). Centro de Documentação e Arquivo Feminista Elina Guimarães, 2025. Disponível em: https://www.cdocfeminista.org/carolina-michaelis-de-vasconcelos-1851-1925/. Acesso em: 25 jan. 2025.

- Sanh, V.; Debut, L.; Chaumond, J.; Wolf, T. (2019). DistilBERT, a distilled version of BERT: smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. arXiv:1910.01108.

- Santos, V.G.; Alves, C.A.; Carlotto, B.B.; Dias, B.A.P.; Gris, L.R.S.; Izaias, R.d.L.; de Morais, M.L.A.; de Oliveira, P.M.; Sicoli, R.; Svartman, F.R.F.; et al. CORAA NURC-SP Minimal Corpus: a manually annotated corpus of Brazilian Portuguese spontaneous speech. IberSPEECH 2022. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- Santos, D. (2000). O projecto Processamento Computacional do Português: Balanço e perspectivas. In M. das Graças (Ed.), V Encontro para o processamento computacional da língua portuguesa escrita e falada (PROPOR 2000) (pp. 105-113).

- Santos, J. V.; Namiuti, C. O futuro das humanidades digitais é o passado. In: CARRILHO, E. et al. Estudos Linguísticos e Filológicos oferecidos a Ivo Castro. Lisboa: Centro de Linguística da Universidade de Lisboa, 2019 (pp. 1381-1404). ISBN 978-989-98666-3-8.

- Sardinha, T. B.; Filho, J. L. M.; Alambert, E. (2010) Manual Córpus Brasileiro. PUCSP, FAPESP. Retrieved , 2021, from https://www.linguateca.pt/Repositorio/manual_cb. 26 May.

- Simmhan, Y.L.; Plale, B.; Gannon, D. A survey of data provenance in e-science. ACM SIGMOD Rec. 2005, 34, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, F.; Nogueira, R.; Lotufo, R. (2020). BERTimbau: Pretrained BERT Models for Brazilian Portuguese. In: Brazilian Conference on Intelligent Systems. Spinger, Cham. (pp. 403-417), from https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-3-030-61377-8_28.

- Stim, R. (2016). Fair Use. Stanford Libraries; NOLO. Retrieved 27 May, 2021, from https://fairuse.stanford.

- Stim, R. (2016). Measuring Fair Use: The Four Factors. Stanford Libraries; NOLO. Retrieved 27 May, 2021, from https://fairuse.stanford.

- Sturzeneker, M. L.; Crespo, M. C. R. M.; Rocha, M. L. S. J.; Finger, M.; Paixão de Sousa, M. C.; Martins do Monte, V.; Namiuti, C. . ‘Carolina’s Methodology: building a large corpus with provenance and typology information’. Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Digital Humanities and Natural Language Processing (2nd DHandNLP 2022). CEUR-WS, Vol. 3128, 2022. Available at http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3128.

- TEI Consortium, Burnard, L.; Sperberg-McQueen, C. M. (2021). TEI P5: Guidelines for electronic text encoding and interchange. Version 4.2.2. Last updated on 9th 21, revision 609a109b1. Retrieved May 20, 2021 from https://tei-c.org/release/doc/tei-p5-doc/en/Guidelines.pdf. 20 April.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A. N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. arXiv:1706.03762.

- Vianna, A. E. P. B.; de Oliveira, L. P. (2010). CORPOBRAS PUC-Rio: Análise de corpus e a metáfora gramatical. PUC-Rio. Retrieved , 2021, from http://www.puc-rio.br/ensinopesq/ccpg/Pibic/relatorio_resumo2010/relatorios/ctch/let/LET-%20Ana%20Elisa%20Piani%20Besserman%20Vianna. 26 May.

- Wagner Filho, J. A.; Wilkens, R.; Idiart, M.; Villavicencio, A. (2018). The BrWac corpus: A new open resource for Brazilian Portuguese. In: Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018). (pp. 4339-4344), from https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/L18-1686.

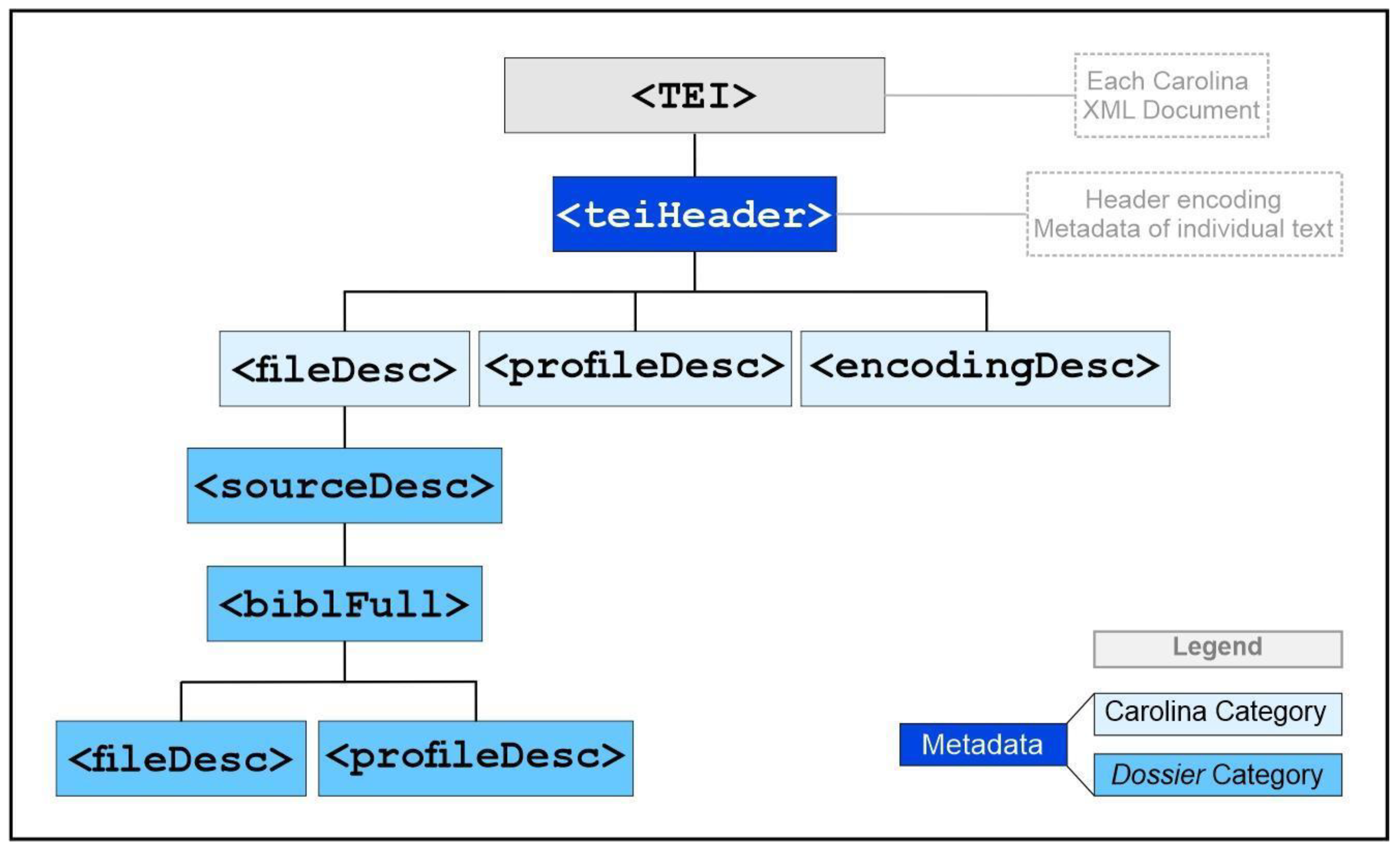

| Category | Group | Item of Metadata | Cardinality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carolina | Primary Identification | Name of the file created in the corpus Corpus description |

1 1 |

| Authorship | Creator of the file in the corpus Responsibilities for the file in the corpus |

1+ | |

| Dating | Date of creation of the file in the corpus Source file download date |

1 | |

| Licenses | License type of the file created in the corpus Access conditions for the file created in the corpus |

1 1 |

|

| Extent | Number of words in the text from the source document | 1 | |

| Typology | Carolina typology | 1 | |

| Dossier | Primary Identification | Title of the source document | 1 |

| Authorship | Source-document author Source-document translator Sponsor (Institution responsible for the source document) |

0+ 0+ 1+ |

|

| Authority | 1 | ||

| Publisher | 0/1 | ||

| Date | Year of publication of the source document Full date or period (start and end) of the source document | 1 0/1 |

|

| Licenses | License of source document (Public domain, Commons, etc.) |

0/1 | |

| License URL | 0/1 | ||

| Usage permissions Access conditions of source document (public, restricted, etc.) |

0/1 0/1 |

||

| Localization | Domain Subdomain Source document access URL Regional origin of source document |

1 0/1 1 0/1 |

|

| Acquisition | File format of the source document (pdf, html, etc.) Constitution (integral, fragmented, etc.) Nature of acquisition (native digital, scanned printout, OCR) Part (part of the collection the document represents, if app.) Collection (of which the document is part of, if app.) |

1 1 1 0/1 0/1 |

|

| Size | File size of the source document (in bytes) Number of pages of the source document |

1 0/1 |

|

| Typology | Document type declared in the source document Linguistic variety (regional) indicated in the source document Written or oral text (transcribed) Domain of use |

0/1 0/1 1 1 |

|

| Degree of preparation | 0/1 | ||

| User-generated | 0/1 |

| Date | Carolina Version | Size (GB) | Number of extracted texts | Number of tokens17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022, Mar | 1.0 - Ada | 39.23 | 1,745,234 | 653,346,569 |

| 2022, Apr | 1.1 - Ada | 7.2 | 1,745,187 | 653,322,577 |

| 2023, Mar | 1.2 - Ada | 11.36 | 2,107,045 | 823,198,893 |

| 2024, Oct | 1.3 - Ada | 11.16 | 2,076,205 | 802,146,069 |

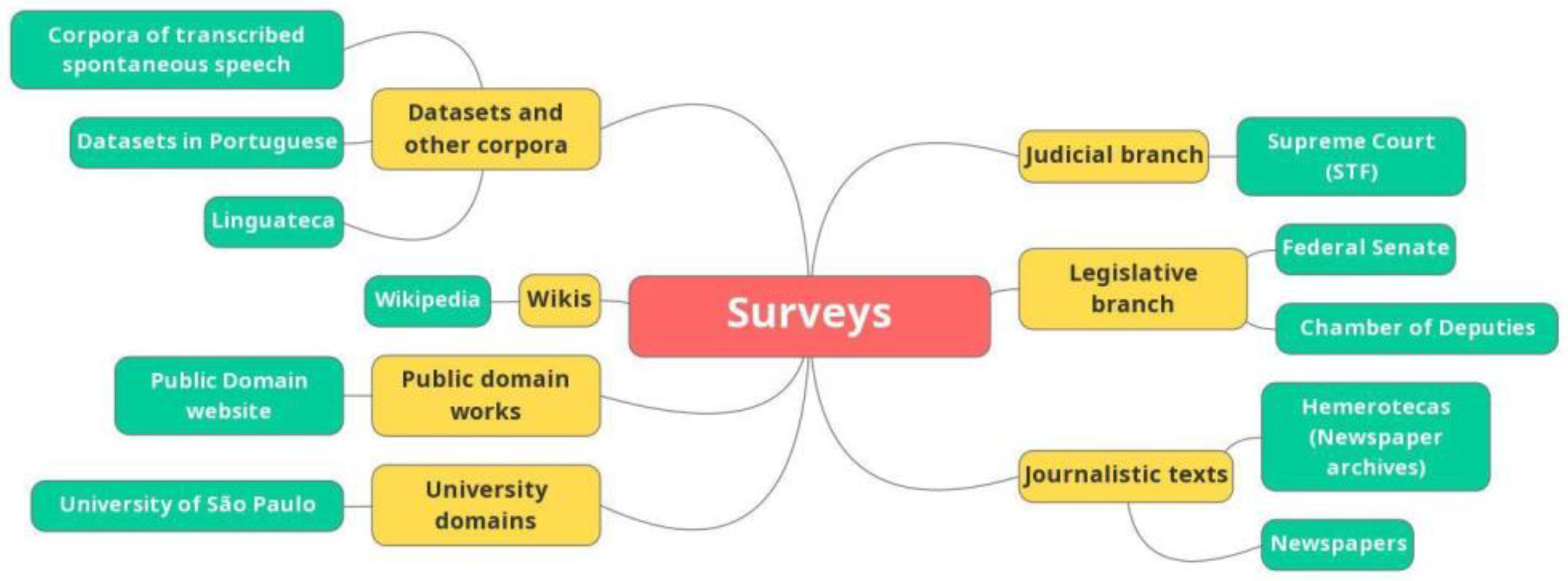

| Broad typology | Size (GB) | Number of extracted texts | Number of words |

|---|---|---|---|

| Datasets and other corpora | 4.3 | 1,074,032 | 196,524,339 |

| Judicial branch | 1.5 | 40,398 | 196,228,167 |

| Legislative branch | 0.025 | 13 | 3,162,474 |

| Public domain works | 0.005 | 26 | 601,465 |

| Social Media | 0.017 | 3,294 | 1,231,881 |

| University domains | 0.011 | 941 | 1,078,967 |

| Wikis | 5.3 | 957,501 | 403,318,776 |

| Journalistic texts | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Current total | 11.16 | 2,076,205 | 802,146,069 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).