Submitted:

23 January 2025

Posted:

26 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

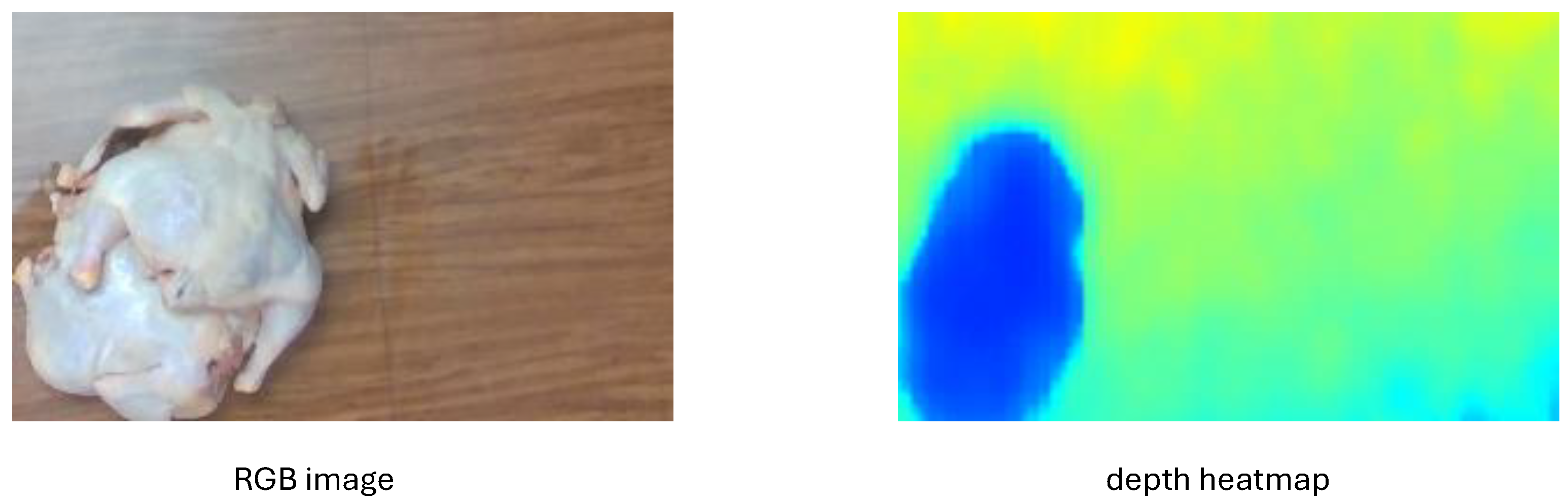

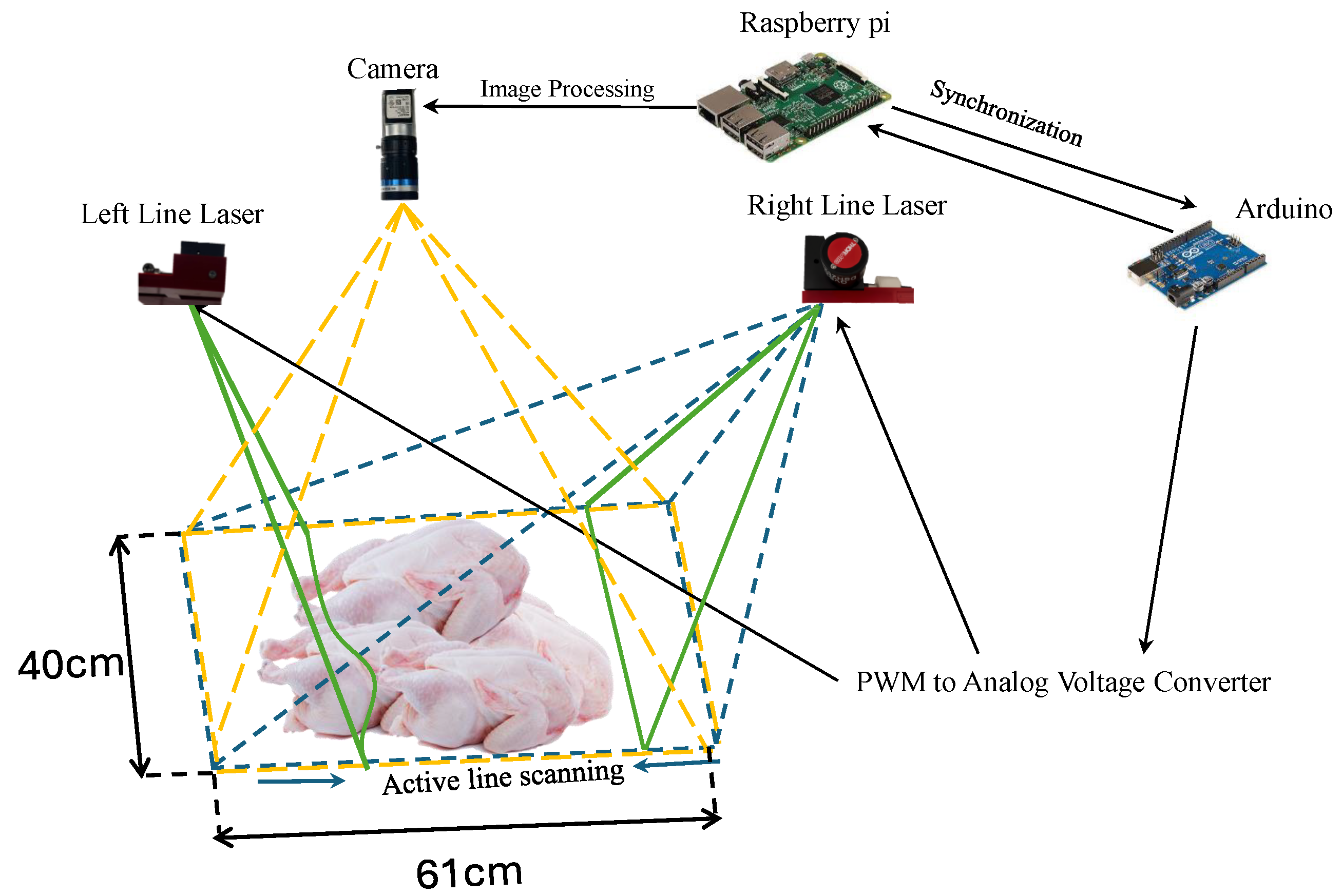

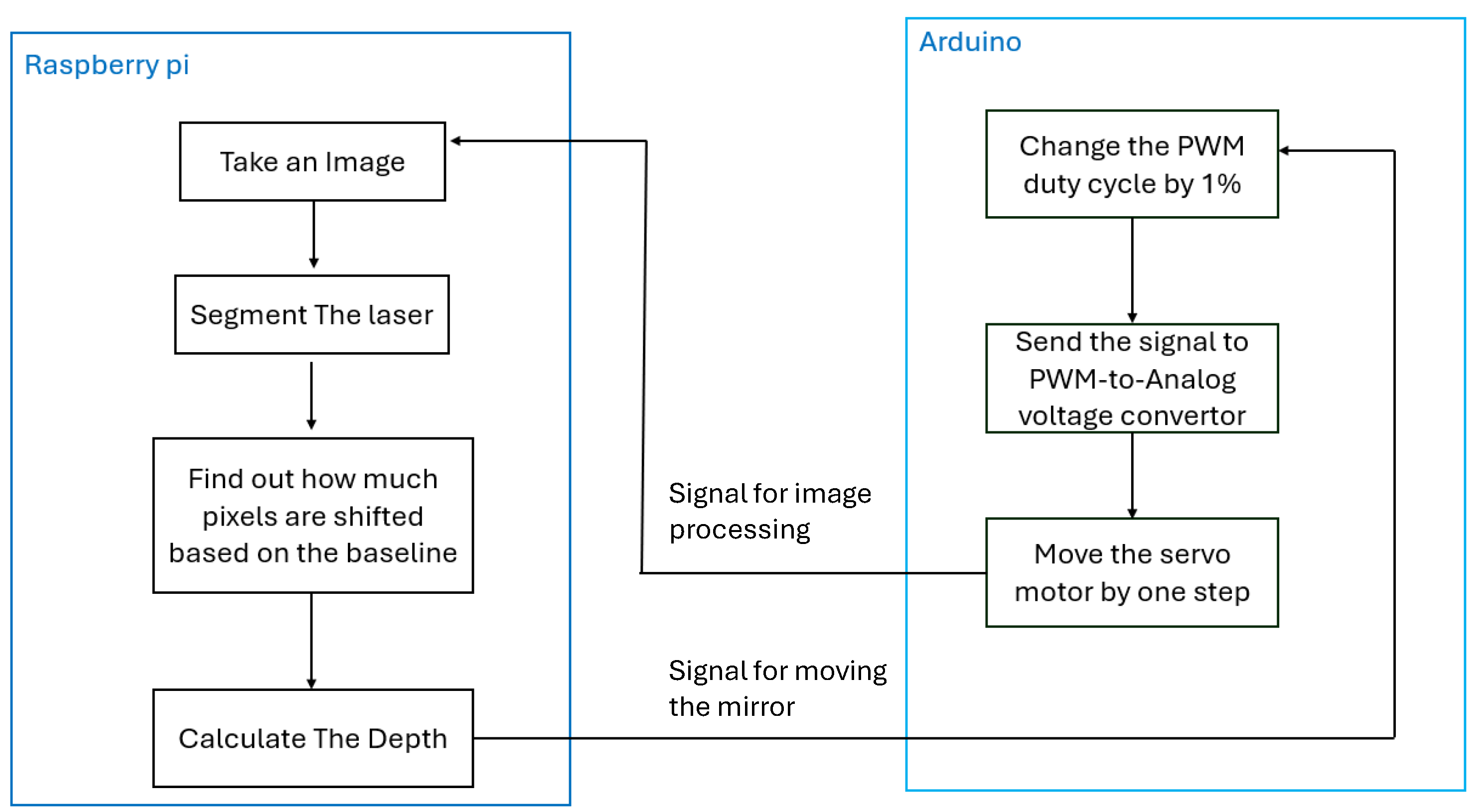

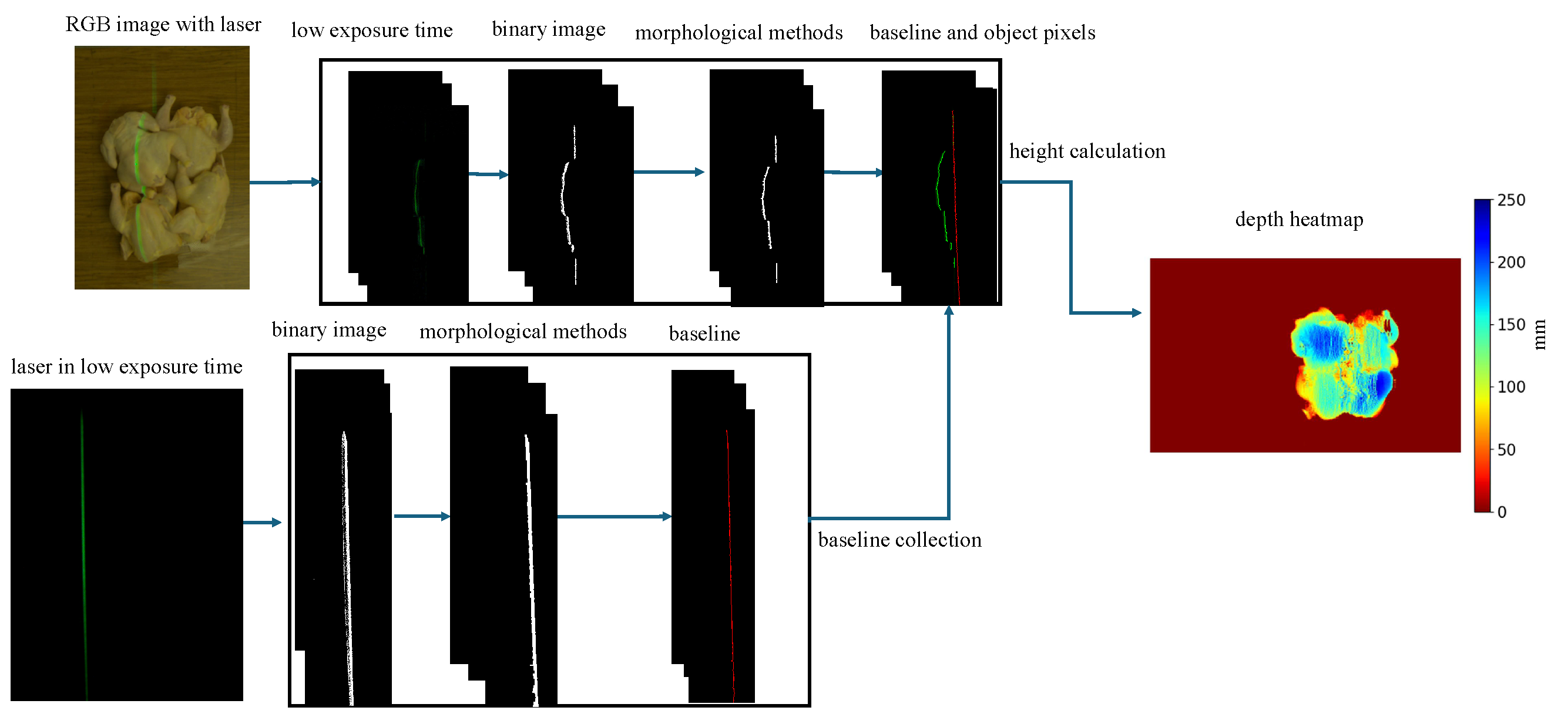

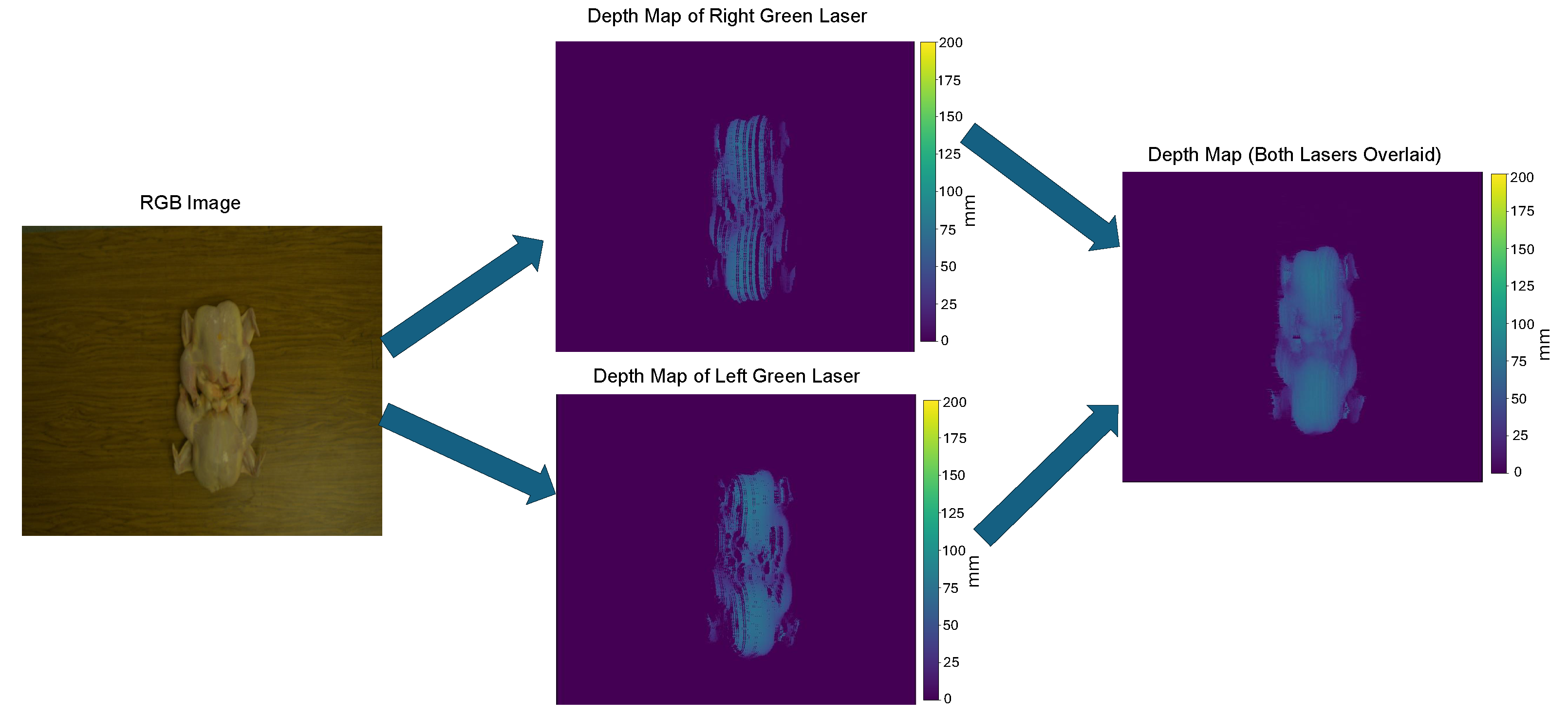

2.1. Dual-Line Laser Active Scanning: A Hardware and Software System for Height Estimation

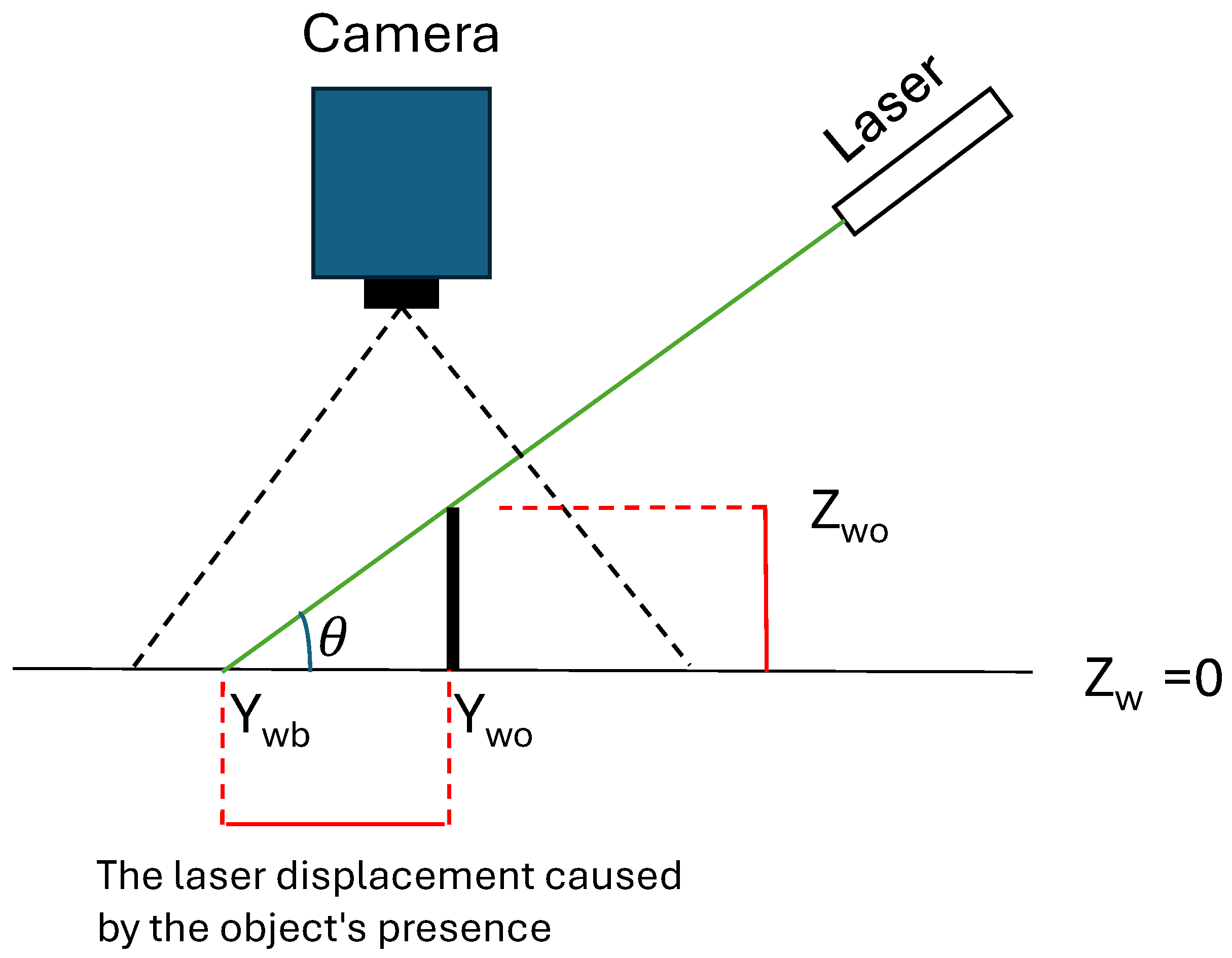

2.2. Optical Triangulation for Object Height Estimation

2.2.1. Baseline Position Collection of Laser Line

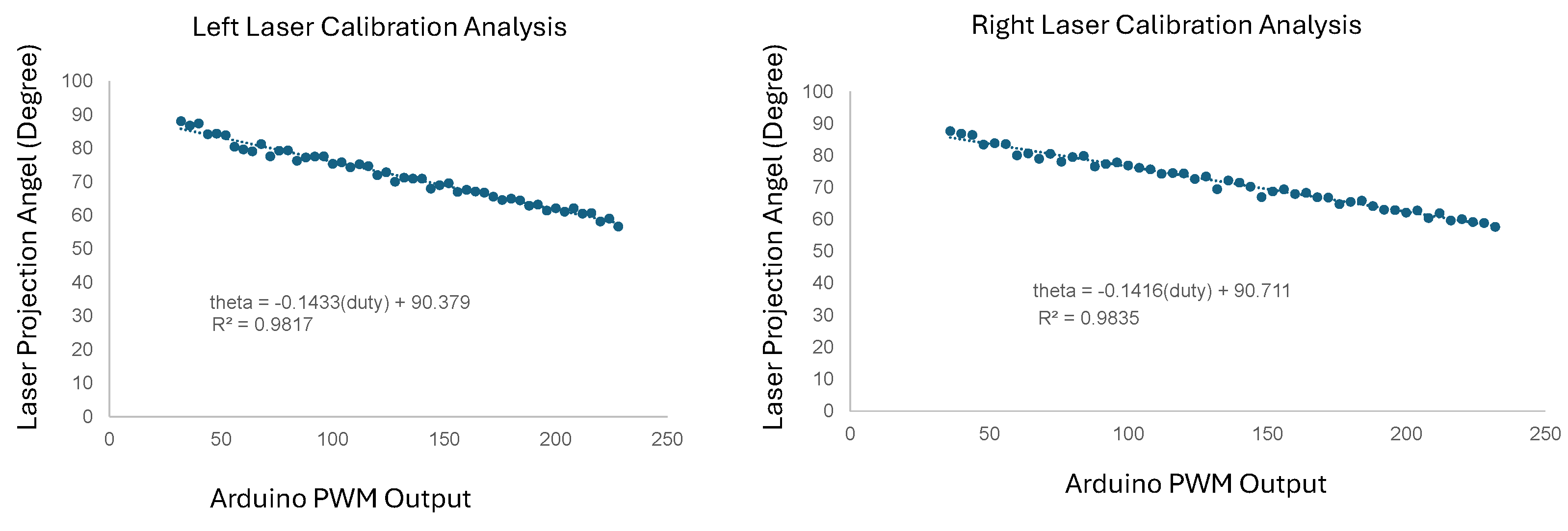

2.2.2. Laser Angle Calibration

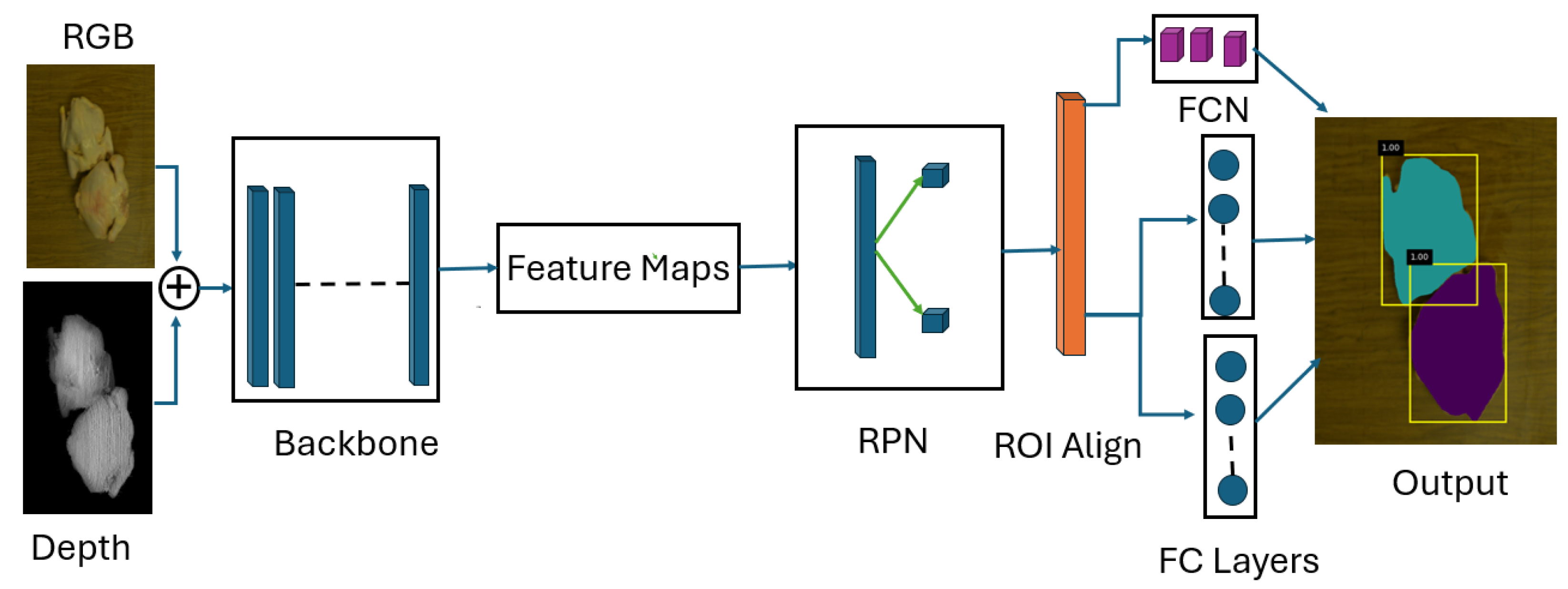

2.3. Instance Segmentation of Chicken Carcass

3. Results

3.1. The Performance Evaluation of Active Laser Scanning System

3.1.1. Laser Calibration Performance

3.1.2. System Depth Estimation Accuracy

3.2. Performance of Chicken Instance Segmentation

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), 2025. Livestock and Poultry: World Markets and Trade. Available online: https://www.fas.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2024-10/Livestock_poultry.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Kalhor, T.; Rajabipour, A.; Akram, A.; Sharifi, M. Environmental impact assessment of chicken meat production using life cycle assessment. Information Processing in Agriculture 2016, 3(4), 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derya, Y. Global Poultry Industry and Trends. 2021. Available online: https://www.feedandadditive.com/global-poultry-industry-and-trends/.

- Barbut, S. Automation and meat quality-global challenges. Meat Science 2014, 96(1), 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, A. (2019). How to get a processing line speed waiver. WATTPoultry. https://www.wattagnet.com/articles/38224-how-to-get-a-processing-line-speed-waiver?

- Christopher, Q. Ga. poultry producers scratch for workers amid rising demand, prices. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. https://www.ajc.com/news/ga-poultry-producers-scratch-for-workers-amid-risingdemand-prices/AOBN7F6ZRZC2PPBDWDYUOECSY4/ 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, D.; Pabiou, T.; Evans, R. D.; Beder, C.; Daly, A. Predicting carcass cut yields in cattle from digital images using artificial intelligence. Meat Science 2021, 181, 108671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, E. U.; Morey, A. Application of optical technologies in the US poultry slaughter facilities for the detection of poultry carcass condemnation. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2020, 100(10), 3736–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, R.; Yang, K.; Zhang, X. X.; Chen, K. Development of Online Detection and Processing System for Contaminants on Chicken Carcass Surface. Applied Engineering in Agriculture 2016, 32(1), 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Iglesia, D. H.; Villarrubia González, G.; Vallejo García, M.; López Rivero, A. J.; De Paz, J. F. Non-invasive automatic beef carcass classification based on sensor network and image analysis. Future Generation Computer Systems 2020, 113, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbon, S. B. J.; Ayub da Costa Barbon, A. P.; Mantovani, R. G.; Barbin, D. F. Prediction of pork loin quality using online computer vision system and artificial intelligence model. Meat Science 2018, 140, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajdi, M.; Varidi, M. J.; Varidi, M.; Mohebbi, M. Using electronic nose to recognize fish spoilage with an optimum classifier. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2019, 13, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joutou, T.; Yanai, K. A food image recognition system with Multiple Kernel Learning. In Proceedings of the 16th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing; pp. 285–288. [CrossRef]

- Tanno, R.; Okamoto, K.; Yanai, K. DeepFoodCam: ADCNN-based Real-time Mobile Food Recognition System; ACM Digital Library, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Ali, M.; Cobau, J.; Tao, Y. Designs of a customized active 3D scanning system for food processing applications. In Proceedings of the 2021 ASABE Annual International Virtual Meeting; p. 2100388. [CrossRef]

- Misimi, E.; Øye, E. R.; Eilertsen, A.; Mathiassen, J. R. B.; Åsebø Berg, O.; Gjerstad, T. B.; Buljo, J. O.; Skotheim, Ø. GRIBBOT - Robotic 3D vision-guided harvesting of chicken fillets. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2016, 121, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.; Parekh, S.; White, R.; Losey, D. P. Safely and autonomously cutting meat with a collaborative robot arm. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aly, B. A.; Low, T.; Long, D.; Baillie, C.; Brett, P. Robotics and sensing technologies in red meat processing: A review. Trends in Food Science Technology 2023, 132, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S., Zhang, G., Fuhlbrigge, T., Watson, T., and Tallian, R. (2023). Applications and requirements of industrial robots in meat processing. IEEE (Year). [DOI/Link if available].

- Echegaray, N.; Hassoun, A.; Jagtap, S.; Tetteh-Caesar, M.; Kumar, M.; Tomasevic, I.; Goksen, G.; Lorenzo, J. M. Meat 4.0: Principles and Applications of Industry 4.0 Technologies in the Meat Industry. Applied Sciences 2022, 12(14), 6986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templer, R. G.; Nicholls, H. R.; Nicolle, T. Robotics for meat processing – from research to commercialisation. Industrial Robot 1999, 26(3), 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnell, G. Robots for the meat industry. Industrial Robot 1995, 22(5), 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, K., Norton, T., Frías, J. M., and Tiwari, B. K. (2017). Robotics in meat processing. In Emerging Technologies in Meat Processing (eds E.J. Cummins and J.G. Lyng). [CrossRef]

- Khodabandehloo, K. Achieving robotic meat cutting. Animal Frontiers 2022, 12(2), 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayik, G. A.; Muzaffar, K.; Gull, A. Robotics and Food Technology: A Mini Review. Food Engineering 2023, 148, 103623. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Kwon, Y.; Kim, H.-W.; Seol, K.-H.; Cho, B.-K. Robot Technology for Pork and Beef Meat Slaughtering Process: A Review. Animals 2023, 13(4), 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, T.; Ahlin, K.; Joffe, B. P. Robotic Rehang with Machine Vision. In Proceedings of the 2021 ASABE Annual International Virtual Meeting; p. 202100519. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Sun, D. W.; Pu, H.; Gao, W.; Dai, Q. Applications of emerging imaging techniques for meat quality and safety detection and evaluation: A review. Journal of Food Engineering 2017, 104, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Hao, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S. A real-time classification and detection method for mutton parts based on single shot multi-box detector. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2021, 45(10). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulum, M. F., Maryani, Min Rahminiwati, L. C., Hendra Setyawan, N., Ain, K., Mukhaiyar, U., Pamungkas, F. A., Jakaria, & Garnadi, A. D. (2024). Assessment of Meat Content and Foreign Object Detection in Cattle Meatballs Using Ultrasonography, Radiography, and Electrical Impedance Tomography Imaging. Advances in Mechanical Engineering, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Wang, W.; Guo, L.; Chen, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y. Evaluation of Deep Learning for Automatic Multi-View Face Detection in Cattle. Agriculture 2021, 11(11), 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y., Truman, M., & Sukkarieh, S. (2019). Cattle segmentation and contour extraction based on Mask R-CNN for precision livestock farming. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 164, 104958. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K., Xie, T., Yan, R., Wen, X., Li, D., Jiang, H., Jiang, N., Feng, L., Duan, X. (2022). An Attention Mechanism-Improved YOLOv7 Object Detection Algorithm for Hemp Duck Count Estimation. Agriculture, 12(10), 1659. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Su, H., Zheng, X., Liu, Y., Zhou, R., Xu, L., Liu, Q., Liu, D., Wang, Z., & Duan, X. (2022). Study of a QueryPNet Model for Accurate Detection and Segmentation of Goose Body Edge Contours. Animals, 12(19), 2653. [CrossRef]

- Modzelewska-Kapituła, M., & Jun, S. (2022). The application of computer vision systems in meat science and industry – A review. Meat Science, 182, 108904. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M. A., Wang, D., & Tao, Y. (2024). Active Dual Line-Laser Scanning for Depth Imaging of Piled Agricultural Commodities for Itemized Processing Lines. Sensors, 24(8), 2385. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Li, J., Liu, C., & Liu, G. (2018). Prediction of pork loin quality using online computer vision system and artificial intelligence model. Meat Science, 140, 155-163. [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1512.03385. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.11946. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. (2023). Challenges and Opportunities in Robotic Food Handling: A Review.

- An, G., et al. (2024). Deep spatial and discriminative feature enhancement network for stereo matching. The Visual Computer, 40, 1–16. Springer.

- Zhao, Z.; Cao, Q.; Zhang, X. Segmentation and Tracking of Vegetable Plants by Exploiting Vegetable Shape Feature for Precision Spray of Agricultural Robots. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.13518. [Google Scholar]

- He, K., Gkioxari, G., Dollár, P., & Girshick, R. (2017). Mask R-CNN. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2961-2969. [CrossRef]

- He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., & Sun, J. (2016). Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 770-778. 2016). Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 770–778. [CrossRef]

- Ai Chen, Xin Li, Tianxiang He, Junlin Zhou, and Duanbing Chen, Advancing in RGB-D Salient Object Detection: A Survey, Applied Sciences, vol. 14, no. 17, pp. 8078, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tran, M. Tran, M., Truong, S., Fernandes, A. F. A., Kidd, M. T., & Le, N. CarcassFormer: An End-to-end Transformer-based Framework for Simultaneous Localization, Segmentation and Classification of Poultry Carcass Defects. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.11429. [Google Scholar]

- Chaitanya Pallerla, Yihong Feng, Casey M. Owens, Ramesh Bahadur Bist, Siavash Mahmoudi, Pouya Sohrabipour, Amirreza Davar, and Dongyi Wang, Neural network architecture search enabled wide-deep learning (NAS-WD) for spatially heterogenous property aware chicken woody breast classification and hardness regression, available at ScienceDirect, 2024.

- K. Simonyan and A. Zisserman, "Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition," in *Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR)*, 2015. [Online]. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1409.1556.

- M. Tan and Q. Le, "EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks," in *Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML)*, vol. 97, 2019, pp. 6105–6114. [Online]. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1905.11946.

- A. Howard, M. Zhu, B. Chen, D. Kalenichenko, W. Wang, T. Weyand, M. Andreetto, and H. Adam, "MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications," 2017. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/1704.04861.

- A. Author, B. Author, and C. Author, “MultiStar: Instance Segmentation of Overlapping Objects with Star-Convex Polygons,” arXiv, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2011.13228.

- Teledyne Vision Solutions, 2023. Accuracy of Stereo Vision Camera Disparity Depth Calculations. Available online: https://www.teledynevisionsolutions.com/support/support-center/technical-guidance/iis/accuracy-of-stereo-vision-camera-disparity-depth-calculations/ (accessed on 16 January 2025).

| Step Height (mm) | Height Value (mm) from Right Laser | Height Value (mm) from Left Laser | Final Height Value Using Both Lasers (mm) | Height Value from Real-Sense (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 43.09 | 46.15 | 45.89 | 27.13 |

| 100 | 97.00 | 99.85 | 98.37 | 83.58 |

| 150 | 143.91 | 147.92 | 145.85 | 202.00 |

| Mask R-CNN RGB Backbones | mAP IoU=0.50:0.95 | Center Offset (pixels) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RGB | RGBD | RGB | RGBD | |

| ResNet50 | 0.631 | 0.680 | 22.09 | 8.99 |

| ResNet101 | 0.508 | 0.638 | 22.18 | 13.34 |

| VGG16 | 0.132 | 0.466 | 19.57 | 21.19 |

| EfficientNetB0 | 0.132 | 0.565 | 22.58 | 16.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).