Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

23 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

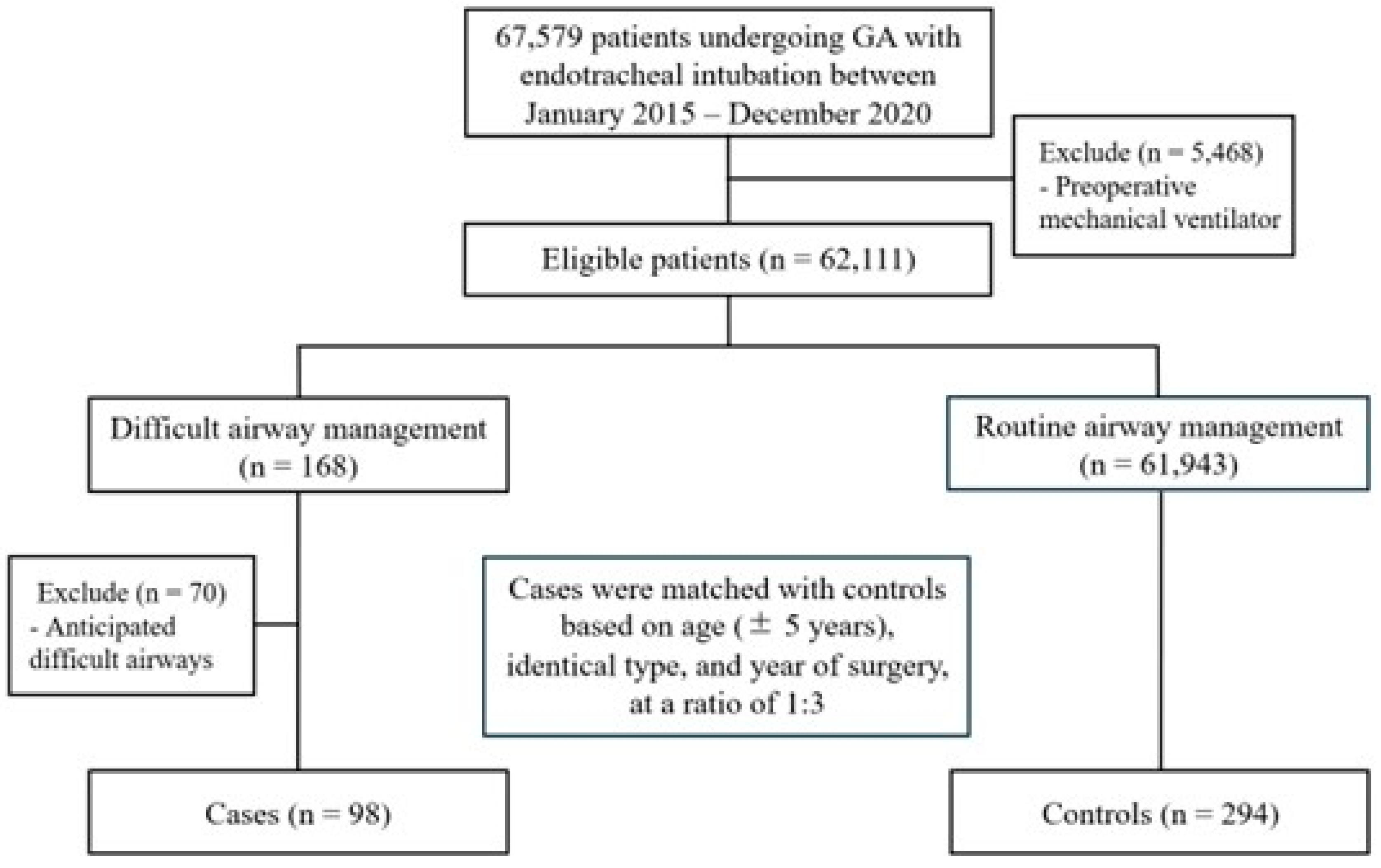

2.1. Patient Selection

2.2. Matching Procedure

2.3. Potential Risk Factors and Confounding Variables

2.4. Sample Size Determination

2.5. Statistical Analysis

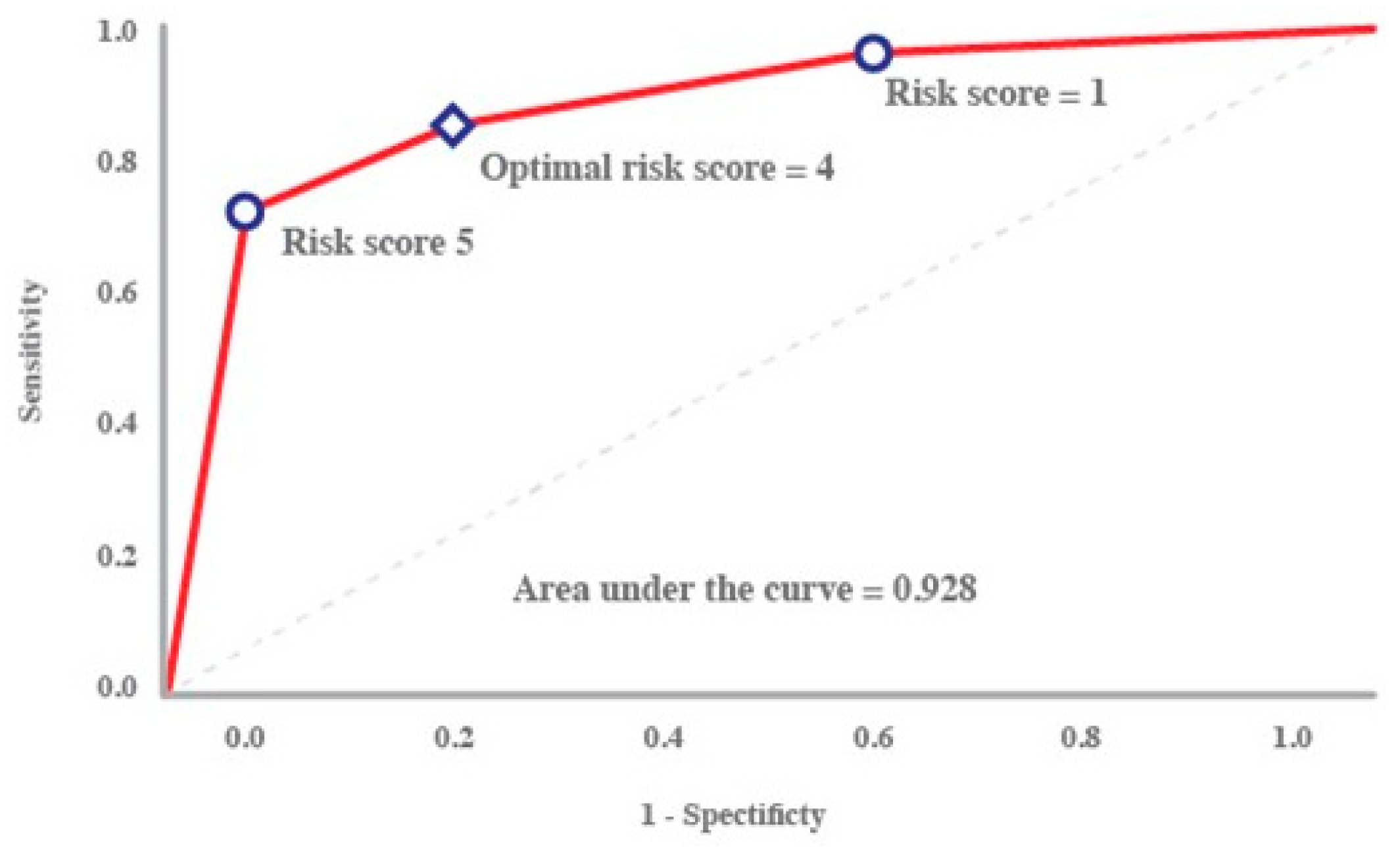

2.6. Score Derivation and Validation

3. Results

3.1. Development of the CLAIR Risk Prediction Tool

3.2. Web-Based Risk Calculator and Accessibility

3.3. Web-Based Risk Calculator and Accessibility

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Interpretation and Implications

3.1.1. CLAIR Score: A Paradigm Shift in Airway Risk Prediction

- Coagulopathy and hypocalcemia

- Laryngoscopic view grades

- Potential airway difficulty

- Inexperienced residents

3.1.2. Clinical Implications in Anesthesia Practice

4.4. Controversies4.5. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PAAd Thai | Perioperative and Anesthetic Adverse Events in Thailand |

| BMI | body mass index |

| ASA | American Society of Anesthesiologists |

| AUC | area under the receiver operating characteristic curve |

References

- Koh, W.; Kim, H.; Kim, K.; Ro, Y.J.; Yang, H.S. Encountering unexpected difficult airway: relationship with the intubation difficulty scale. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2016, 69, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crosby, E.T.; Cooper, R.M.; Douglas, M.J.; Doyle, D.J.; Hung, O.R.; Labrecque, P.; Muir, H.; Murphy, M.F.; Preston, R.P.; Rose, D.K.; et al. The unanticipated difficult airway with recommendations for management. Can. J. Anaesth. 1998, 45, 757–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benumof, J.L. Management of the difficult adult airway. With special emphasis on awake tracheal intubation. Anesthesiology. 1991, 75, 1087–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrich, S.; Birkholz, T.; Irouschek, A.; Ackermann, A.; Schmidt, J. Incidences and predictors of difficult laryngoscopy in adult patients undergoing general anesthesia: a single-center analysis of 102,305 cases. J. Anesth. 2013, 27, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.N.; Sundaram, V. Incidence and predictors of difficult mask ventilation and intubation. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 28, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraj, A.K.; Siddiqui, N.; Abdelghany, S.M.O.; Balki, M. Management of difficult and failed intubation in the general surgical population: a historical cohort study in a tertiary care centre. Can. J. Anaesth. 2022, 69, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipanmekaporn, T.; Punjasawadwong, Y.; Raksakietisak, M.; Sriraj, W.; Lekprasert, V.; Werawatganon, T. A study into perioperative anaesthetic adverse events in Thailand (PAAd Thai): an analysis of suspected emergence delirium. J. Perioper. Pract. 2018, 1750458918780117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, A.M.; Aziz, M.F.; Posner, K.L.; Duggan, L.V.; Mincer, S.L.; Domino, K.B. Management of difficult tracheal intubation: A closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 2019, 131, 818–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, T.M.; Woodall, N.; Harper, J.; Benger, J.; Fourth National Audit Project. Major complications of airway management in the UK: results of the Fourth National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Difficult Airway Society. Part 2: Intensive care and emergency departments. Br. J. Anaesth. 2011, 106, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, S.M.; Tiwari, A.; Chung, F.; Wong, D.T. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor associated with difficult airway management - A narrative review. J. Clin. Anesth. 2018, 45, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawley, S.M.; Dalton, A.J. Predicting the difficult airway. BJA Educ. 2015, 15, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honarmand, A.; Safavi, M.; Yaraghi, A.; Attari, M.; Khazaei, M.; Zamani, M. Comparison of five methods in predicting difficult laryngoscopy: neck circumference, neck circumference to thyromental distance ratio, the ratio of height to thyromental distance, upper lip bite test and Mallampati test. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2015, 4, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trambadia, D.N.; Yadav, P.; A, S. Preoperative assessment to predict difficult airway using multiple screening tests. Cureus. 2023, 15, e46868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, S.H.; Lee, J.G.; Yu, S.B.; Kim, D.S.; Ryu, S.J.; Kim, K.H. Predictors of difficult intubation defined by the intubation difficulty scale (IDS): predictive value of 7 airway assessment factors. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2012, 63, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidhya, S.; Sharma, B.; Swain, B.P.; Singh, U.K. Comparison of sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of Wilson’s score and intubation prediction score for prediction of difficult airway in an eastern Indian population-A prospective single-blind study. J. Family Med. Prim. Care. 2020, 9, 1436–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apfelbaum, J.L.; Hagberg, C.A.; Connis, R.T.; Abdelmalak, B.B.; Agarkar, M.; Dutton, R.P.; Fiadjoe, J.E.; Greif, R.; Klock, P.A.; Mercier, D.; et al. 2022 American Society of Anesthesiologists Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway. Anesthesiology. 2022, 136, 31–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, S.; Srinivasan, S.; Jain, R.K. Hypocalcaemia leading to difficult airway in sepsis. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 27, 123–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsetti, A.; Sorbello, M.; Adrario, E.; Donati, A.; Falcetta, S. Airway ultrasound as predictor of difficult direct laryngoscopy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth. Analg. 2022, 134, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luis-Cabezón, N.; Ly-Liu, D.; Renedo-Corcostegui, P.; Santaolalla-Montoya, F.; Zabala-Lopez de Maturana, A.; Herrero-Herrero, J.C.; Martínez-Hurtado, E.; De Frutos-Parra, R.; Bilbao-Gonzalez, A.; Fernandez-Vaquero, M.A. A new score for airway assessment using clinical and ultrasound parameters. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 2024, 11, 1334595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulkerson, J.S.; Moore, H.M.; Anderson, T.S.; Lowe, R.F. Jr. Ultrasonography in the preoperative difficult airway assessment. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2017, 31, 513–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, D.; Pace, N.L.; Lee, A.; Hovhannisyan, K.; Warenits, A.M.; Arrich, J.; Herkner, H. Airway physical examination tests for detection of difficult airway management in apparently normal adult patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 5, CD008874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallhi, A.I.; Abbas, N.; Naqvi, S.M.N.; Murtaza, G.; Rafique, M.; Alam, S.S. A comparison of Mallampati classification, thyromental distance and a combination of both to predict difficult intubation. Anaesth. Pain Intensive Care. 2018, 22, 468–473. [Google Scholar]

- Ambesh, S.P.; Singh, N.; Rao, P.B.; Gupta, D.; Singh, P.K.; Singh, U. A combination of the modified Mallampati score, thyromental distance, anatomical abnormality, and cervical mobility (M-TAC) predicts difficult laryngoscopy better than Mallampati classification. Acta Anaesthesiol. Taiwan. 2013, 51, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.Y.; Zhang, K.D.; Zhang, Z.H.; Zhang, D.X.; Wang, H.L.; Qi, F. Evaluation of the reliability of the upper lip bite test and the modified mallampati test in predicting difficult intubation under direct laryngoscopy in apparently normal patients: a prospective observational clinical study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2022, 22, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komatsu, R.; Kasuya, Y.; Yogo, H.; Sessler, D.I.; Mascha, E.; Yang, D.; Ozaki, M. Learning curves for bag-and-mask ventilation and orotracheal intubation: an application of the cumulative sum method. Anesthesiology. 2010, 112, 1525–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E J, S.K.; Purva, M.; Chander M, S.; Parameswari, A. Impact of repeated simulation on learning curve characteristics of residents exposed to rare life threatening situations. BMJ Simul. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2020, 6, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Unanticipated difficult airway (n = 98) |

Non-difficult airway (n = 294) |

Total (n = 392) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.243 | |||

| Male | 56 (57.1) | 146 (49.7) | 202 (51.5) | |

| Female | 42 (42.9) | 148 (50.3) | 190 (48.5) | |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 55 (38.0, 65.8) | 56 (36.2, 64.0) | 56 (37.8, 64.0) | 0.790 |

| Age (years) | match | |||

| ≤7 | 12 (12.2) | 34 (11.6) | 46 (11.7) | |

| 8–20 | 3 (3.1) | 14 (4.8) | 17 (4.3) | |

| 21–64 | 56 (57.1) | 180 (61.2) | 236 (60.2) | |

| ≥ 65 | 27 (27.6) | 66 (22.4) | 93 (23.7) | |

| Weight (kg), median (IQR) | 58.8 (49.1, 70.0) | 59.5 (48.4, 69.0) | 59.5 (48.5, 69.2) | 0.980 |

| Height (cm), median (IQR) | 160 (152.2,165.9) | 158.5 (150,165) | 159 (151,165) | 0.346 |

| BMI (kg/m2) median (IQR) | 23.3 (19,25.9) | 22.7 (19.2,26) | 22.9 (19.2,26) | 0.494 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.286 | |||

| < 15 | 8 (8.2) | 21 (7.1) | 29 (7.4) | |

| 15–29 | 82 (83.7) | 231 (78.6) | 313 (79.8) | |

| ≥30 | 8 (8.2) | 42 (14.3) | 50 (12.8) | |

| ASA classification | 0.798 | |||

| I | 2 (2) | 13 (4.4) | 15 (3.8) | |

| II | 52 (53.1) | 155 (52.7) | 207 (52.8) | |

| III | 43 (43.9) | 123 (41.8) | 166 (42.3) | |

| IV | 1 (1) | 3 (1) | 4 (1) | |

| Preoperative probable difficult airway | 0.002 | |||

| No | 95 (96.9) | 247 (84) | 342 (87.2) | |

| Yes | 3 (3.1) | 47 (16) | 50 (12.8) | |

| Modified Mallampati classification | 0.911 | |||

| 1–2 | 79 (80.6) | 239 (81.3) | 318 (81.1) | |

| 3–4 | 10 (10.2) | 26 (8.8) | 36 (9.2) | |

| unknown | 9 (9.2) | 29 (9.9) | 38 (9.7) | |

| Thyromental distance | 0.832 | |||

| < 3 finger breaths | 3 (3.1) | 8 (2.7) | 11 (2.8) | |

| 3 finger breaths | 64 (65.3) | 181 (61.6) | 245 (62.5) | |

| > 3 finger breaths | 22 (22.4) | 80 (27.2) | 102 (26) | |

| unknown | 9 (9.2) | 25 (8.5) | 34 (8.7) | |

| Inter-incisor gap | 0.824 | |||

| 1–2 cm | 7 (7.1) | 16 (5.4) | 23 (5.9) | |

| 3–4 cm | 82 (83.7) | 251 (85.4) | 333 (84.9) | |

| unknown | 9 (9.2) | 27 (9.2) | 36 (9.2) | |

| Limited neck flexion and extension | 1 | |||

| No | 94 (95.9) | 284 (96.6) | 378 (96.4) | |

| Yes | 3 (3.1) | 8 (2.7) | 11 (2.8) | |

| Cannot evaluate | 1 (1) | 2 (0.7) | 3 (0.8) | |

| Upper lip bite test classification | 0.681 | |||

| 1 | 53 (54.1) | 175 (59.5) | 288 (58.2) | |

| 2 | 26 (26.5) | 75 (25.5) | 101 (25.8) | |

| 3 | 1 (1) | 3 (1) | 4 (1) | |

| unknown | 18 (18.4) | 41 (13.9) | 59 (15.1) | |

| Facial appearance or syndrome | 0.418 | |||

| Normal | 95 (96.9) | 289 (98.3) | 384 (98) | |

| Abnormal | 3 (3.1) | 5 (1.7) | 8 (2) | |

| Edentulous | 0.840 | |||

| No | 88 (89.8) | 268 (91.2) | 356 (90.8) | |

| Yes | 10 (10.2) | 26 (8.8) | 36 (9.2) | |

| Overbite | 0.250 | |||

| No | 97 (99) | 294 (100) | 391 (99.7) | |

| Yes | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Previous history of difficult intubation and ventilation | 1 | |||

| No | 98 (100) | 293 (99.7) | 391 (99.7) | |

| Yes | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Medical conditions | 1 | |||

| No | 93 (94.9) | 278 (94.9) | 371 (94.6) | |

| Yes | 5 (5.1) | 16 (5.4) | 21 (5.4) | |

| Congenital heart disease | 0.770 | |||

| No | 95 (96.9) | 281 (95.6) | 376 (95.9) | |

| Yes | 3 (3.1) | 13 (4.4) | 16 (4.1) | |

| Airway/neck/oral deformity | 0.639 | |||

| No | 90 (91.8) | 276 (93.9) | 366 (93.4) | |

| Yes | 8 (8.2) | 18 (6.1) | 26 (6.6) | |

| Foreign body aspiration | 0.438 | |||

| No | 97 (99) | 293 (99.7) | 390 (99.5) | |

| Yes | 1 (1) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) | |

| Infection: retropharyngeal abscess, epiglottitis, supraglottitis | 1 | |||

| No | 97 (99) | 292 (99.3) | 389 (99.2) | |

| Yes | 1 (1) | 2 (0.7) | 3 (0.8) | |

| Post-surgical procedure: thyroid, cervical vertebrae | 0.504 | |||

| No | 94 (95.9) | 286 (97.3) | 380 (96.9) | |

| Yes | 4 (4.1) | 8 (2.7) | 12 (3.1) | |

| OSA/Snoring | 0.875 | |||

| No | 83 (84.7) | 245 (83.3) | 328 (83.7) | |

| Yes | 15 (15.3) | 49 (16.7) | 100 (16.3) | |

| Tumors: thyroid, pharynx, larynx and tracheobronchus, esophagus | 0.634 | |||

| No | 86 (87.8) | 265 (90.1) | 528 (87.7) | |

| Yes | 12 (12.2) | 29 (9.9) | 74 (12.3) | |

| Trauma: face, neck | 0.643 | |||

| No | 96 (98) | 290 (98.6) | 386 (98.5) | |

| Yes | 2 (2) | 4 (1.4) | 6 (1.5) | |

| Burns (head, neck, face), smoke inhalation, massive burn | 0.261 | |||

| No | 96 (98) | 292 (99.3) | 388 (99) | |

| Yes | 2 (2) | 2 (0.7) | 4 (1) | |

| History radiation of head, neck | 0.697 | |||

| No | 95 (96.9) | 288 (98) | 383 (97.7) | |

| Yes | 3 (3.1) | 6 (2) | 9 (2.3) | |

| Laryngeal edema: angioedema, allergic, post rigid bronchoscopy | 1 | |||

| No | 97 (99) | 292 (99.3) | 389 (99.2) | |

| Yes | 1 (1) | 2 (0.7) | 3 (0.8) | |

| Coagulopathy and hypocalcemia | 0.102 | |||

| No | 95 (96.9) | 292 (99.3) | 387 (98.7) | |

| Yes | 3 (3.1) | 2 (0.7) | 5 (1.3) | |

| Type of surgery | match | |||

| Remote | 14 (14.3) | 41 (13.9) | 55 (14) | |

| Neuro/Orthopedic | 6 (6.1) | 18 (6.1) | 24 (6.1) | |

| Eye/superficial | 12 (12.2) | 40 (13.6) | 52 (13.3) | |

| ENT | 31 (31.6) | 90 (30.6) | 121 (30.0) | |

| Thoracic/Vascular | 12 (12.2) | 34 (11.6) | 46 (11.7) | |

| Abdomen | 23 (23.5) | 71 (24.1) | 94 (24) | |

| First-attempt intubation personnel | 0.152 | |||

| Anesthesia instructors | 9 (9.2) | 31 (10.5) | 40 (10.2) | |

| Anesthesiology residents | 72 (73.5) | 187 (63.6) | 259 (66.1) | 0.096 |

| Certified registered nurse anesthetists | 3 (3.1) | 28 (9.5) | 31 (7.9) | |

| Nurse anesthetist students | 14 (14.3) | 48 (16.3) | 62 (15.8) | |

| Intubation experience (years) | 0.837 | |||

| < 5 | 93 (94.9) | 275 (93.5) | 368 (93.9) | |

| 5–10 | 3 (3.1) | 13 (4.4) | 16 (4.1) | |

| 11–20 | 2 (2) | 4 (1.4) | 6 (1.5) | |

| > 20 | 0 (0) | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.5) | |

| Laryngoscopic view | < 0.001 | |||

| Grade 1 | 10 (10.2) | 227 (77.2) | 237 (60.5) | |

| Grade 2 | 14 (14.3) | 49 (16.7) | 63 (16.1) | |

| Grade 3 | 43 (43.9) | 14 (4.8) | 57 (14.5) | |

| Grade 4 | 30 (30.6) | 0 (0) | 30 (7.7) | |

| Unknown | 1 (1) | 4 (1.4) | 5 (1.3) |

| Predictive factors | Coefficient | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | Risk score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C: Coagulopathy and hypoCalcemia | 2.36 | 10.57 (0.67, 167.55) | 0.094 | 3 |

|

L: Laryngoscopic view (Ref: grade 1) Grade 2 Grade 3 Grade 4 |

2.14 4.85 5.36 |

8.52 (3.45, 21.04) 128.15 (45.66, 359.67) 212.4 (56.66, 796.25) |

< 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 |

3 6 7 |

| A: potential Airway difficulty | -2.97 | 0.05 (0.01, 0.23) | < 0.001 | -4 |

| IR: Inexperienced Residents | 0.96 | 2.61 (1.17, 5.81) | 0.019 | 1 |

| Score | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | +LR | -LR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 100.00 | 2.38 | 25.45 | 100.00 | 51.19 | 1.02 | 0 |

| 4 | 98.98 | 9.18 | 26.65 | 96.43 | 54.08 | 1.09 | 0.11 |

| 5 | 97.96 | 15.65 | 27.91 | 95.83 | 56.80 | 1.16 | 0.13 |

| 6 | 96.94 | 15.65 | 27.70 | 93.88 | 56.29 | 1.15 | 0.2 |

| 7 | 79.59 | 22.45 | 25.49 | 76.74 | 51.02 | 1.03 | 0.91 |

| 8 | 35.71 | 55.44 | 21.08 | 72.12 | 45.58 | 0.8 | 1.16 |

| 9 | 2.04 | 99.66 | 66.67 | 75.32 | 50.85 | 6 | 0.98 |

| 10 | 1.02 | 99.66 | 50.00 | 75.13 | 50.34 | 3 | 0.99 |

| 11 | 0.00 | 99.66 | 0 | 74.94 | 49.83 | 0 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).