1. Introduction

Hydrogen sulfide (H

2S) is a highly toxic gas used as a raw material in industry. It is transported and stored in bulk for this purpose [

1]. H

2S is classified as a blood agent because it inhibits cellular respiration and shares some similar toxic metabolic properties with cyanide and azide [

2]. There are also multiple sources of H

2S in the environment, and it is also a hazard in > 80 occupational settings [

1]. For example, it is a byproduct of industrial processes e.g. the natural gas and petroleum industry, and is produced naturally as a result of anaerobic decomposition of human and animal sewage. These are some of the many sources of accidental acute H

2S poisoning. It is estimated that there are more than 1000 reports of acute exposures to H

2S each year [

3] and globally the number of cases is likely to be much higher. H

2S also has a history of use as a chemical weapon [

4]. Components to make this lethal gas have been found in Islamic State camps [

5] and was recently used in a foiled terrorist incident in Australia [

6]. It is easily generated from commonly available materials [

4,

5,

7]. As a result of the latter, H

2S has been employed as a suicide agent in confined spaces, such as cars and apartments, endangering bystanders and/or first responders [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Because of its lethality and a history of use as a chemical weapon, there are concerns about the potential misuse of H

2S as a weapon of mass destruction, which could result in significant civilian casualties with high morbidity and mortality [

5,

7].

Although there is large body of literature on toxic effects of acute H

2S poisoning, knowledge on the neurotoxic mechanisms of acute poisoning by this gas, both immediate and delayed, is still evolving. Commonly cited neurotoxic mechanisms include inability of cells to utilize oxygen (histotoxic hypoxia), or hypoxia resulting from oxygen deficiency caused by poor gaseous exchange in the lungs triggered by H

2S -induced pulmonary edema, hypotension negatively impacting blood flow to the brain, and direct toxicity of the gas on brain cells. H

2S is also a well known inhibitor of cytochrome c oxidase (CCO), a terminal enzyme in the electron transport chain respensible for proton gradient to drive ATP generation [

12,

13], causing energy deprivation. The brain is particularly vulnerable to this biochemical lesion because it has limited alternative pathways to generate the necessary energy [

1]. The clinical phenotype of the immediate effects of acute H

2S poisoning is well known and is characterized by a sudden loss of the sense of smell, irritation, sudden collapse (knockdown), coma, seizures, reduced breathing rate, dyspnea, and death within minutes following exposure to H

2S at concentrations exceeding 500 ppm[

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. However, much less is known about the delayed neurological sequelae of acute H

2S poisoning, including their prevalence, whether they are reversible or permanent, and the basic celullar and molecular mechanisms underlying a wide array of reported neurological sequelae including learning and cognition deficits, postural instability predisposing to falls, insomnia, anxiety, depression, aggravated seizures, slurred speech, hearing impairment, persistent headaches, among others are unknown [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. Considering neurological diseases are a major cause of mobidity and mortility worldwide, and that the number of these cases is increasing each year, it is important to understand the role of the enviromantal factors in the pathogenesis of these diseases, including that of acute H

2S poisoning.

Goals of the Literature Review

The goal of this literature review was to gain a better understanding of the nature of neurological sequelae induced by acute H

2S poisoning in humans and their prevalence. This is particularly important because neurological diseases are a leading cause of disability and the second most common cause of death [

33] and the burden of these diseases is not only large but also increasing globally [

34]. Therefore, it is crucial to understand all factors that are contributing to this burden, including the role of acute H

2S poisoning. To the best of our knowledge, we are not aware of any comprehensive review of the literaure on this topic. Our review covered literature from 1950 to 2024. We also reviewed the existing literature on animal models used to study dealyed neurological sequelae of acute H

2S poisining during the same period.

2. Outcomes of the Literature Review on Neurological Sequelae of Acute H2S Poisoning in Humans

We found at least 3 published large population studies of mass civilian exposures to H

2S. In the 1950 industrial accident at a gas treatment plant in Poza Rica Mexico 22 people (6%) were killed and 320 (94%) were hospitalized [

31]. Exposure was for about 20 mins. Of the 320 hospitalized victims, medical professionals closely monitored only 47 of them for an unspecified period of time and used undisclosed evaluation techniques. Of these 47 closely observed, 4 developed neurological sequelae including slurred speech (dysarthria) [one patient], neuritis of the acoustic nerve (two patients), and one epileptic suffered a marked worsening of his condition [

31]. The 2003 accidental sour gas well blow-out in China caused 243 (2.7%) deaths and 9000 hospital visits and hospitalizations [

35]. Individuals who died were exposed for about 30 mins. Unfortunately, no long-term follow-ups were done to evaluate surviving victims for neurological sequelae. The third large population study involved a review of 152 clinical cases of acute H

2S poisoning in China and was published by Wang et al in 1989 [

36]. Victims in this study were exposed to H

2S in different ways. Some were exposed to H

2S produced in a fire in a sulfide production facility, others were victims of acute H

2S exposure from putrefaction, while the rest were exposed to H

2S via leakage of pipelines transporting the gas and other sources. This study showed a 5.3% mortality rate, and 39 (41%) of the 95 patients that were followed up for 1-10 yrs developed neuropsychiatric sequelae [

36]. Reported neurological sequalae in this particular study included brain fog, impaired memory, difficulty focusing, decreased motivation, mental fatigue (collectively known as mental asthenia), hysteria, “mental illness” and a decorticate posture. Unfortunately, as in the case of Poza Rica Mexico accident, the techniques used for evaluation of patients for neurological sequelae were not reported. All three large population studies showed that the overall mortality rate ranged from 2.7% to 6%, implying that the majority of victims of acute H

2S poisoning survive the accidents. Notably, Wang’s review paper of a large population supports the observation that long-term follow-up and assessment using neuropsychiatric testing indicate that neurological sequelae are common and are largely behavioral in nature because 41% of the 95 patients followed up for 1-10 yrs developed neurological sequelae [

36]. Considering the high survival rate of victims of this highly neurotoxic gas, it is imperative that we fully investigate the potential for survivors of accidents involving acute H

2S exposure to develop neurological sequelae, to study and identify underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms, and to develop drugs for prevention and/or treatment of victims to reduce morbidity and mortality.

A summary of the other literature on neurological sequelae following acute H

2S poisoning, most involving human case studies, is given in

Table 1. These delayed sequalae typically set in a starting about 72 h post exposure and they include locomotor deficits such as walking with a spastic gait, slowed movement (bradykinesia), postural instabilty causing falls, learning and memory (cognition) deficits, deficits in executive planning functioning, hearing impairment, dysarthria, slowed mental and physical function (psychomotor retardation), sleep disorders like insomnia, persistent headaches, neuropsychiatric disorders, aggravation of preexisting seizures, and in the most severe cases, permanent vegetative states [

18,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

32,

36,

38]. It was notable that not all individuals reported developing all these sequalae, as different individuals displayed some but not other symptoms. The severity of these neurological sequelae also varied from individual to individual for reasons that are not entirely known. Some victims became moribund and died weeks later while others only displayed neurophyschological effects. Considering that the majority of the victims of acute H

2S poisoning survive, and in the case the majority of these survivors develop neurological sequelae, these delayed sequelae can potentially be devastating by imposing a heavy burden on victims, caretakers, and on the healthcare system in general. Moreover, because this medical condition is understudied, currently, there are no FDA approved drugs for prevention or treatment of these neurological sequelae of acute H

2S poisoning. Without knowledge of the underlying mechanisms it is a challenge to develop target specific therapeutic interventions.

3. Observed Limitations of Reviewed Literature

This literature review revealed several inconsistencies regarding the evaluation of patients for neurological sequalae following acute H

2S poisoning. Notably, several reported human cases of acute H

2S poisoning lacked adequate follow-up following the accidents to sufficiently evaluate presence or absence of sequelae. Follow-up of patients for periods of 1-10 yr would be ideal to conclusively determine whether neurological sequelae are present or not. Moreover, in some cases, patient evaluations for neurological sequelae was not done at all [

35]. Another limitation was that when adequate follow-up was done, the techniques and endpoints used to assess the presence of sequelae were variable and inconsistent. Endpoints assessed included brain anatomical changes using imaging modalities such us MRI, brain function changes using PET, neurological examinations, and neuropsychological examinations. Thorough evaluations would have used all these techniques for a comprehensive patient evaluations but this was not the case. Moreover, psychiatric examinations were suggested but none of the case studies reviewed performed them. We also observed that the older literature [

29,

30] lacked long-term follow-up of victims after hospital discharge and/or did not perform specialized neurological, neuropsychological, or brain imaging examinations ideal for determining long-term neurological impacts. These inconsistences may be some of the reasons why some authors have suggested that neurological sequalae after acute H

2S poisoning are rare [

39]. For example, Haouzi et al [

39] cited Mooyaart et al 2016 [

29,

40] to assert that sequelae are rare, but Mooyaart’s study focused on only 8 victims who received cardiopulmonary resuscitation after the accidents and reported that 6 of these 8 patients who received cardiopulmonary resuscitation (75 %) did not have neurological sequelae. Yet, in the same Mooyaart study, they reported that 24 of the 54 victims (43%) survived but whether the rest of the survivors were evaluated for neurological sequelae was not reported. Moreover, Mooyaart et al only reviewed medical records and did not report the assessment techniques used by physicians to assess the presence and types of neurological sequalae. They simply stated that no permanent damage was observed, which may be misleading [

36]. Mooyaart’s study should be contrasted with other case reports in which appropriate long-term follow-up on victims and assessment techniques were done which showed that H

2S-induced neurological sequalae

are more common [18,26]. Specifically, Tvedt’s study in which victims who were unconscious for 5-20 mins and followed up for 5-10 yrs with neurological and neuropsychological examination showed that one patient had severe dementia, and that memory and motor function were most affected [

37]. They also reported that two patients who were most severely affected had pulmonary edema which emphasizes the importance of using inhalation exposures to recapitulate the lung-brain axis in the pathogenesis of neurological deficits.

4. Distribution of Delayed Neurological Anatomical and Functional Lesions

It was interesting that lesions reported publications summarized in

Table 1 were present only in select brain regions. Nam B et al reported necrosis of basal ganglia and motor cortex by MRI 30 days after the accident [

19]. Matsuo F et al showed bilateral cerebral and lentiform nucleus lessions in a patient in a chronic vegetative state who died 5 weeks after exposure [

27]. Schneider JS et al showed abnormal metabolism in the thalamus, basal ganglia, temporal and inferior parietal lobe using PET 3 yrs after the accident [

28]. The same study reported decreased metabolism in putamen, amygdala and hippocampus by SPECT 3.5 yrs after the accident. Tvedt B et al (1991) showed cerebral atrophy and widening of 3

rd vetericle using MRI and CT scans 5 yrs after the accident [

18]. Gaitonde et al 1987 reported symetric low densities of basal ganglia by CT scan [

41]. Thus the cortex, thalamus, and basal ganglia develop lesions. Notably, however, functional changes involved additional brain regions including the hippocampus, suggesting H

2S casues functional impairment without necessity inducing brain lesions [

28]. This is significant because absence of lesions does not imply absence of disease. In otherwords, it is possible for victims of acute H H

2S 2S poisoning to develop neurological and/or neurophyshiatric disease without necessarily developing brain lesions. Warencya, MW et al [

42] (1989) suggested inhibition of monoaminooxidase enzyme is a sequela of acute H

2S poisoning which is responsible for increased brain catecholamins and serotonin levels. This coould be a mechanism of H

2S-induced neurophychological sequalae, but need further evalauation. It is also possible that the reported brain anatomical changes could drive the development of the various neurological sequlae reported in various survivors of acute H

2S poisoning.

Other toxicants such as cyanide and azide were reported to share a common toxic mechanism with H

2S poisoning by inhibiting CCO activity, blocking ATP and causing energy deficit in the brain [

43,

44]. Brain ischaemia and hypoglycemia also share some similarities with H

2S poisoning as they cause hypoxia and/or energy deficit [

45]. Indeed hypoxia is often cited as the cause of the brain lesions following acute H

2S poisoning [

19,

46]. However, we observed that the distribution of brain lesions following acute cyanide or azide poisoning, though similar to that of acute H

2S poisoning, is not identical with that of acute H

2S poisoning. Cyanide poisoning affects the basal ganglia primarily [

47] and Parkinsonism syndrome is the primary sequela of acute cyanide poisoning [

48]. Azide poisoning affects the basal ganglia, cerebral cortex, and the cerebellum [

49,

50]. In a rat model, cereral ischemia of 2-5 mins and 1 week of recovery neuronal necrosis was reported in the CA1 of the hippocampus, the dentate gyrus, the thalamus, and the primary olfactory cortex [

45]. Ischemia of 6-30 mins duration and evaluation after 1 week caused injury middle layers of cerebral cortex, caudate nucleus, substantia nigra, and ventral thalamus [

45]. In a rat model of hypoglycemic coma for 30 mins followed by 1 week of recovery, the lesion distribution was seen in surface layers of the cerebral cortex, parts of the dentate gyrus, and the foramen of Lushka [

51]. Using an inhalation model of acute H

2S poisioning for 15-45 mnutes Kim et al reported lesions in the cortex, thalamus, inferior coliculus, basal ganglia and select nuclei the brainstem [

52]. The variation in lesion distribution in these cases which involve hypoxia and/or energy deficits suggest a combination of shared similar but also unique mechanisms of brain injury.

5. Potential Mechanisms Underlying H2S-Induced Neurological Sequelae

In our review we did not come across any studies of molecular mechanisms in inducing neurological sequelae. It was also apparent that there is a wide range of neurological sequelae in human victims of acute H

2S poisoning. Not all sequelae are induced in all victims. For example some victims may experience dysathria while others will experience hearing impairment. Yet, others will develop neurophychological effects and/or memory impaiment. As reported by Fenga C (2002) reduced cognition, depression and personality changes can exist even when a neurological examination and neuroimaging is unremarkable suggesting anatomic brain lesions are not essential for development of neurological sequelae [

25]. Therefore, some of these effects could be caused by altered brain metabolism and/or neurotransmitter level changes, altered expression and function of synaptic proteins, altered calcium signalling pathways, and altered neural communication and signalling. Using an inhalation mouse model of acute H

2S poisoning our lab has demonstrated altered dopamine, epinephrine and glutamate levels [

12,

13,

52]. It is possible that such changes in neurotransmitter levels are responsible for some of the behavioral changes reported. Moreover, H

2S also causes acute lung injury (ALI) simultaneously [

12,

53]. The impact of pulmonary disorders on neurological health commonly called the lung-brain axis is well known [

54,

55]. These recent publications suggest that mechanisms by which ALI contribute to brain injury are more complex than via hypoxia alone which is commonly cited as a contributing factor [

54,

55]. Therefore, there is a critical knowledge gap on understanding the underlying molecular and cellular mechanisms, the minimum single toxic doses required to trigger them, factors predisposing to neurological sequelae, whether the reported sequealae are reversible or not, and how to prevent or treat them.

There is also a major debate whether the neurotoxicity of H

2S is a result of direct effects of the gas on the brain or whether it is a result of secondary events e.g. due to hypoxia [

46]. There is sufficient evidence in the literature to show that acute H

2S exposure induces hypoxia and that this is one of the mechanisms contributing to brain lesions [

1,

56,

57]. However, questions on the downstream cellular and molecular mechanisms by which hypoxia triggers neuronal cell death and why neuronal cell death occurs in selective brain regions rather than globally remain uninvestigated and unknown. Understanding these pathways is key to developing therapeutic interventions targetings critical pathways of cell injury and death. It is notable, however, that work from our laboratory and works of others affirm direct effects of H

2S on brain cells [

46,

53,

58].

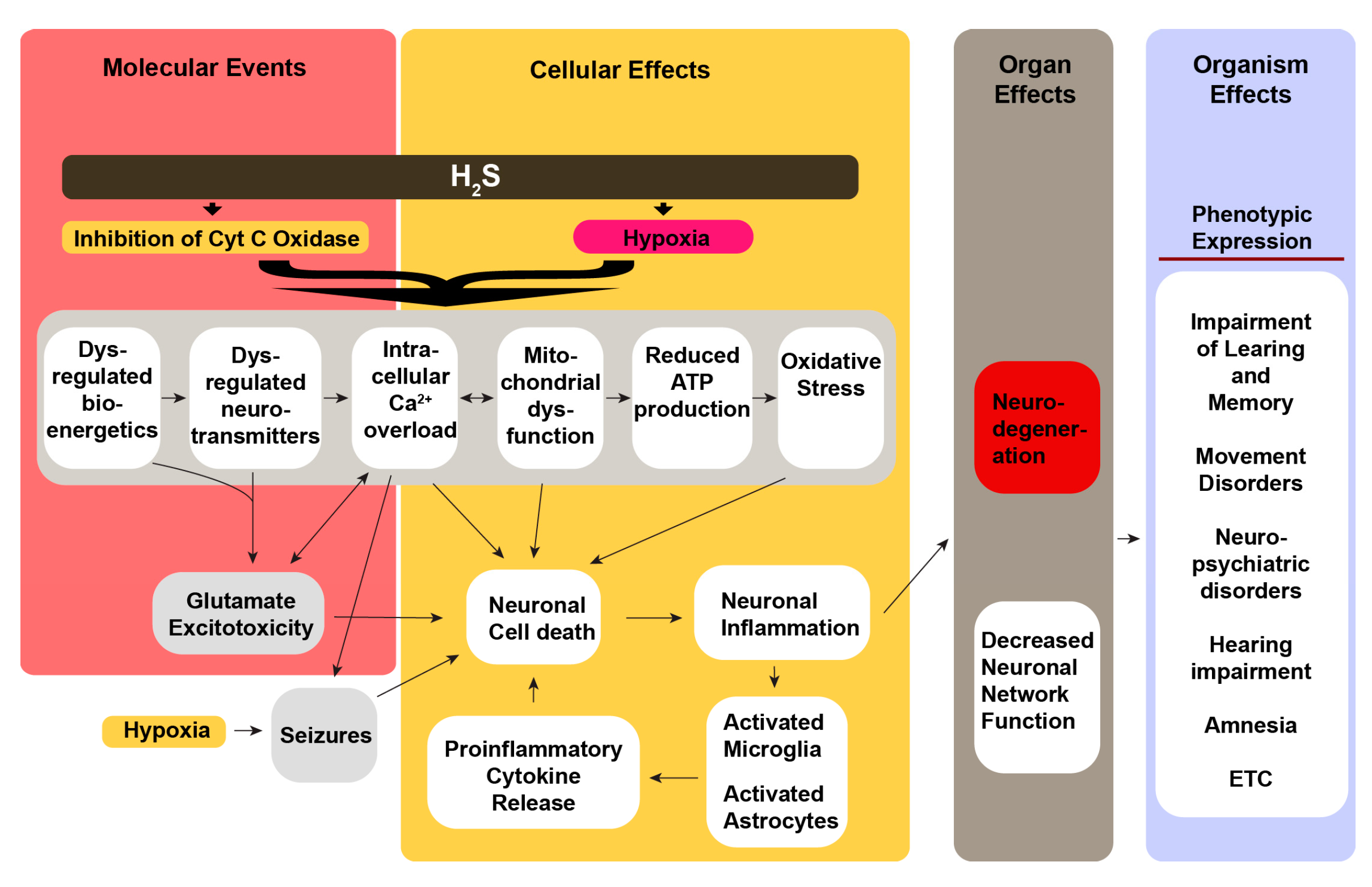

Our overall hypothesis on the mechanisms by which acute H

2S exposure induces neurological sequelae is summarized in

Figure 1. We hypothesize that neurological sequelae of acute H

2S poisoning is triggered by a cascade of multiple cellular mechanisms triggered by direct effects of H

2S on brain cells inducing mitochondrial injury (energy failure), oxidative stress, calcium dysregulation, neurotransmitter imbalances, and neuroinflammation (

Figure 1) [

12,

53,

58,

59]. Seizures cause secondary effects including neurodegeneration [

60]. Our secondary hypothesis is that acute H

2S poisoning induces neurological sequelae via the lung-brain axis. In this regard H

2S-induced ALI contributes to the development of neurological sequalae via multiple mechanisms including hypoxia (pulmonary edema), pro-inflammatory cytokines, and extracellular vesicles of lung origin, and lung microbiome [

54,

55]. Published literature indicates that > 80% of the survivors of acute respiratory distress develop neurological sequelae including cognitive and emotional impairments, depression, anxiety, cognitive impairments, and persistent psychological distress [

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67]. We postulate that the combination of these direct and indirect mechanisms has additive or synergistic effects to cause the reported sequalae, particularly the neuropsychological effects. Thus, there is a huge knowledge gap on testing these hypotheses to generate knowledge on underlying cellular mechanisms causing the neurological sequelae of acute H

2S poisoning. This knowledge is essential for treating victims of acute H

2S poisoning to reduce morbidity.

6. A Review of the Literature of Animal Models

There is meager literature involving use of animal models to study neurological sequelae of acute H

2S poisoning. In our lab we use a whole-body inhalational mouse model which recapitulates the natural route of acute H

2S poisoning in humans which is a single inhalation exposure [

12,

52]. The majority of studies have been done using rodent models i.e rats and mice [

58,

68,

69,

70,

71] but some used sheep [

72], which did not reproduce clinical symptoms including neurological lesion and sequelae. We made two major observations from the literature review involving use of animal models, all regarding flaws in the approach. A major flaw we observed in the research approach is that most investigators use intraperitoneal (IP) or intravenous injections of H

2S chemical donors [

39,

56,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78]. Though convenient, this approach does not recapitulate the typical human route of exposure, i.e. inhalation, as this flawed approach disregards the roles of both the nose-brain axis and the lung-brain axis in inducing neurotoxicity and neurological sequelae [

54,

79,

80]. Absorption of toxicants

via the olfactory route is well documented for many toxicants and is likely involved with a simple molecule like H

2S. Therefore, following inhalation absorption through the olfactory route could be involved. Besides, H

2S exposure by inhalation causes ALI which also likely plays a role in development of neurological sequelae [

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67]. Notably, ALI is absent following IP/IV injections. Hence, the animal models using this route for H

2S exposure [

56,

71] are likely to have difficulty replicating the neurological lesions reported in numerous human case reports in

Table 1 [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

36,

37] or replicating data generated using an inhalation mouse model [

12,

13,

52,

53,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85]. Therefore, scientific results from animal models using IP/IV injections of NaHS and other H

2S chemical donors should be interpreted with caution. Secondly, we observed that there are no animal studies on the natural history of acute H

2S poisoning in the literature, specifically those mimicking a long-term follow-up following acute H

2S in humans. Studies using animal models to study the natural history of a single acute H

2S exposure are needed as they can significantly contribute to our knowledge on sequelae of acute H

2S poisoning in humans.

7. Discussion

The environment has a role to play in the pathogenesis of neurological diseases. Cases of non-communicable neurological diseases are increasing annually as the number of older Americans increases. Already, neurological diseases are reducing the quality of life of many Americans, accounting for significant mortality and morbidity, and contributing to escalating healthcare costs. It is therefore essential that all environmental factors with potential contribution to neurological conditions, including dementia, cognition impairment, neuropsychological conditions, movement disabilities, etc. are investigated and mechanisms unraveled. This will allow interventions including development of therapies to prevent and treat these neurological conditions.

Whereas the immediate short term effects of acute H2S are well known, literature on the prevalence of neurological sequelae of acute H2S poisoning is meager and mixed. Some publications suggest that neurological sequelae are more common and likely under reported while others suggested that they are rare. In this review we have observed that neurological sequelae of acute H2S poisoning are common and are likely underreported in the literature. A wide array of neurological sequalae were reported including cognition, locomotion, ataxia, hearing, sleep, emotion, seizures, and others. It was notable that different individuals developed different sequalae and behavioral effects were more common among victims. We noticed inconsistencies in reporting of neurological sequalae in case reports. Most studies reported the immediate effects of acute poisoning but did not involve long-term follow-up studies which is essential to uncover the sequalae. Another deficiency we observed was the inconsistencies in patient evaluation for the sequelae. Considering neurological sequelae are many and varied, this suggests it requires different specialized medical expertise to accurately identify these sequelae. When neurological sequelae were evaluated, evaluations included brain anatomical or functional imaging, or neurological examinations, or neuropsychological assessments. Notably, however, only a few studies performed patient evaluations using a combination of these techniques. We also observed that in some case reports the patient assessment techniques used were not reported at all. This reduced the quality of the case reports. Moreover, some of the literatures which failed to report the assessment techniques used only involved a review of patient medical records. Overall, our observation is that as of now there is a dearth of studies in which a long-term comprehensive assessment of victims of acute H2S poisoning was done involving highly specialized medical specialists with expertise in radiology, neurology, and neuropsychology. As such it is possible that the prevalence of neurological sequelae is currently underestimated.

Regarding the literature using animal models we observed a paucity of long-term studies to investigate neurological sequelae. There are no studies on the natural history of single acute inhalation studies of H

2S in animal models. Neurological sequalae take time to develop and follow up studies for 3 months to 2 years are needed first to identify the sequalae and secondly to determine whether or not these effects are reversible. Secondly, we observed a general trend in which animal studies used a flawed approach i.e injecting chemical donors of H

2S IP or IV to study effects of H

2S on the brain and other tissues. Some of these studies reported difficulties of recapitulating brain lesions and other sequalae reported in humans. Such studies should be interpreted with caution and should be challenged. These studies do not recapitulate the natural route of human exposure i.e. via inhalation and do not cause ALI. Shortcuts using IP/IV injections of chemical donors negate the contributions of the olfactory route of absorption (nose-brain axis) and the contributions of acute respiratory distress induced by H

2S-induced (Lung-brain axis) to the development of neurological sequelae. The potential contributions of the lung-brain axis via ALI to the pathogenesis of mood and other neuropsychological disorders reported in victims of acute H

2S via inhalation in freely walking animal models cannot be ignored. It is our observation that more work needs to be done using appropriate models and for suitable duration using multiple evaluation endpoints to fully determine the extent of neurological sequelae, the underlying mechanisms, and whether these sequelae are reversible or not. A short-term inhalation mouse model of a single acute H

2S exposure has recapitulated locomotor impairment, neurochemical changes, and MRI lesions in select brain lesions of mice [

12].

Recommended future research directions needed to move this field forward include long-term (at least 10 yrs) interdisciplinary evaluations and assessment of victims of acute H2S intoxication by qualified medical experts in radiology (imaging), neurology, neuropsychology, and perhaps neuropsychiatry to fully characterize neurological sequalae of this potent gas. Research using animal models should also involve interdisciplinary collaborations, use animal models which recapitulate the inhalation route of exposure, and should be of sufficient duration to allow delayed effects to develop and to determine whether these effects are reversible or not. It is also noteworthy that the published literature is devoid of molecular mechanistic research deciphering the molecular mechanisms of how neurological sequelae develop. In addition, the role of the lung-brain axis in the pathogenesis of H2S-induced neurological sequalae needs further research. The contribution of this route to the development of sequelae reported in this case should not be dismissed especially considering that the lung is directly impacted by H2S gas via inhalation. It should be noted, however, that some neurological sequelae were reported while anatomic imaging scans did not show any abnormalities. This suggests that some sequelae may not be triggered by presence of brain lesions but rather functional changes. It should also be noted that the locations of brain lesions caused by H2S are not identical to that caused by cyanide, azide, hypoglycemia, or asphyxia (hypoxia) though there were some similarities. This suggests that H2S poisoning bears specific properties not shared by other toxicants with some shared toxicity e.g. inhibition of the CCO enzyme.

8. Conclusions

H2S has caused mass mortality in the past. Evidence from the published population studies suggests that the majority of victims of acute H2S poisoning accidents survive. There is also ample evidence from the literature that survivors of acute H2S poisoning develop a variety of neurological sequelae. Also, there are concerns that industrial accidents and/or nefarious use of this gas will cause mass mortality and morbidity. A key concern is that currently, there are no FDA approved drugs for treatment of mass civilian casualties of acute H2S poisoning to prevent or cure neurological sequelae. Part of the reason is that there is meager research in this area hence there is a knowledge gap on cellular and molecular mechanisms by which H2S causes these neurological sequelae. We posit that this involves both direct effects of H2S on the brain confounded by acute respiratory distress from H2S-induced lung injury (lung-brain axis). Neurological diseases currently impart a heavy burden on patients and the healthcare system, and since the number of individuals with these conditions is steadily increasing annually, it is critical that we understand the role of the environment in the pathogenesis of these conditions, including the role of acute H2S poisoning in order to develop intervention strategies to reduce both mortality and morbidity. There is also a need to use appropriate animal models which recapitulate typical human exposure scenarios, including exposure via inhalation as other routes of exposure bypass the role of the lung-brain and/or nose-brain axes in brain injury and neurological sequelae.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Wilson K Rumbeiha; Literature Review, Wilson K Rumbeiha.; writing—original draft preparation, Wilson K Rumbeiha.; writing—review and editing, Dong-Suk Kim; funding acquisition, Wilson K Rumbeiha. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. This project did not receive external funding.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| H2S |

Hydrogen sulfide |

| ATP |

Adenosine triphosphate |

| CCO |

Cytochrome C oxidase |

| FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

| MRI |

Magnetic resonance imaging |

| PET |

Positron emission tomography |

| CT |

Computed tomography |

| SPECT |

Single photon emission computed tomography |

| ALI |

Acute lung injury |

References

- W. Rumbeiha, E. Whitley, P. Anantharam, D. S. Kim, and A. Kanthasamy, “Acute hydrogen sulfide-induced neuropathology and neurological sequelae: challenges for translational neuroprotective research,” Ann N Y Acad Sci, vol. 1378, no. 1, pp. 5-16, Aug 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Skolnik and C. W. Heise, “Hydrogen sulfide,” in Critical Care Toxicology J. Brent et al. Eds. Springer Nature Springer Nature 2017, ch. 99, pp. 1963-1971.

- (2016). Toxicological profile for hydrogen sulfide and carbonyl sulfide.

- C. H. Foulkes, “Gas!” The Story of the Special Brigade. Naval and Military, 2009, p. 408.

- M. K. Binder, J. M. Quigley, and H. F. Tinsley, “Islamic State chemical weapons: A case contained by its context?,” CTC SENTINEL, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 27-31, 2018.

- R. Stuart and L. Hall. “Sydney terror plotters ’tried to blow up Etihad plane, unleash poison gas attack’.” ABC NEWS. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-08-04/sydney-terror-raids-police-say-plane-bomb-plot-disrupted/8773752 (accessed Dec. 2, 2021).

- HAZMAT/SAFETY. “TSA issues security awareness message on potential use of H2S in terrorist attack.” BULKTRANSPORTER. https://www.bulktransporter.com/hazmatsafety/tsa-issues-security-awareness-message-potential-use-h2s-terrorist-attack (accessed Dec 2, 2021).

- S. Papadodima, I. Papoutsis, P. Nikolaou, C. Spiliopoulou, and M. Stefanidou, ““Detergent suicide” by adolescent as instructed by internet: A case report,” Forensic Sci Crimino, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 1-2, 2017.

- A. R. Anderson, “Characterization of Chemical Suicides in the United States and Its Adverse Impact on Responders and Bystanders,” The western journal of emergency medicine, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 680-683, Nov 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. B. Ruder, J. G. Ward, S. Taylor, K. Giles, T. Higgins, and J. M. Haan, “Hydrogen sulfide suicide: a new trend and threat to healthcare providers,” Journal of burn care & research : official publication of the American Burn Association, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. e23-5, Mar-Apr 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. N. Sams, H. W. Carver, 2nd, C. Catanese, and T. Gilson, “Suicide with hydrogen sulfide,” The American journal of forensic medicine and pathology, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 81-2, Jun 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Santana Maldonado et al., “Acute hydrogen sulfide-induced neurochemical and morphological changes in the brainstem,” Toxicology, vol. 485, p. 153424, Feb 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Anantharam et al., “Characterizing a mouse model for evaluation of countermeasures against hydrogen sulfide-induced neurotoxicity and neurological sequelae,” Ann N Y Acad Sci, vol. 1400, no. 1, pp. 46-64, Jul 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. O. Beauchamp, Jr., J. S. Bus, J. A. Popp, C. J. Boreiko, and D. A. Andjelkovich, “A critical review of the literature on hydrogen sulfide toxicity,” Critical reviews in toxicology, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 25-97, 1984. [CrossRef]

- T. L. Guidotti, “Hydrogen Sulfide intoxication,” in Handbook of Clinical Neurology, vol. 131, M. Lotti and M. L. Bleecker Eds., 3rd ed., 2015, ch. 8.

- World Health Organization. “Hydrogen Sulfide.” ICPS International Programme on Chemical Safety. (accessed December 29, 2015).

- H. H. Wasch, W. J. Estrin, P. Yip, R. Bowler, and J. E. Cone, “Prolongation of the P-300 latency associated with hydrogen sulfide exposure,” Archives of neurology, vol. 46, no. 8, pp. 902-4, Aug 1989. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2757531.

- B. Tvedt, A. Edland, K. Skyberg, and O. Forberg, “Delayed neuropsychiatric sequelae after acute hydrogen sulfide poisoning: affection of motor function, memory, vision and hearing,” Acta neurologica Scandinavica, vol. 84, no. 4, pp. 348-51, Oct 1991. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1772008.

- B. Nam et al., “Neurologic sequela of hydrogen sulfide poisoning,” Industrial health, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 83-7, Jan 2004. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14964623.

- C. R. Hoidal, A. H. Hall, M. D. Robinson, K. Kulig, and B. H. Rumack, “Hydrogen sulfide poisoning from toxic inhalations of roofing asphalt fumes,” Annals of emergency medicine, vol. 15, no. 7, pp. 826-30, Jul 1986. [CrossRef]

- A. R. Hirsch, “Hydrogen sulfide exposure without loss of consciousness: chronic effects in four cases,” Toxicol Ind Health, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 51-61, Mar 2002. [CrossRef]

- P. Sanz-Gallen, S. Nogue, M. Palomar, M. Rodriguez, M. J. Marti, and P. Munne, “[Acute poisoning caused by hydrogen sulphide: clinical features of 3 cases],” Anales de medicina interna, vol. 11, no. 8, pp. 392-4, Aug 1994. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7772687. Intoxicacion aguda por sulfuro de hidrogeno: aspectos clinicos en tres casos.

- L. J. Hurwitz and G. I. Taylor, “Poisoning by sewer gas with unusual sequelae,” Lancet, vol. 266, no. 6822, pp. 1110-12, May 29 1954. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13164338.

- M. C. Shivanthan et al., “Hydrogen sulphide inhalational toxicity at a petroleum refinery in Sri Lanka: a case series of seven survivors following an industrial accident and a brief review of medical literature,” Journal of occupational medicine and toxicology, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 9, Apr 11 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. Fenga, A. Cacciola, and E. Micali, “[Cognitive sequelae of acute hydrogen sulphide poisoning. A case report],” La Medicina del lavoro, vol. 93, no. 4, pp. 322-8, Jul-Aug 2002. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12212401. Sequele cognitive nell’intossicazione acuta da idrogeno solforato. Descrizione di un caso clinico.

- K. H. Kilburn, “Case report: profound neurobehavioral deficits in an oil field worker overcome by hydrogen sulfide,” The American journal of the medical sciences, vol. 306, no. 5, pp. 301-5, Nov 1993. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8238084.

- F. Matsuo, J. W. Cummins, and R. E. Anderson, “Neurological sequelae of massive hydrogen sulfide inhalation,” Archives of neurology, vol. 36, no. 7, pp. 451-2, Jul 1979. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/454254.

- J. S. Schneider, E. H. Tobe, P. D. Mozley, Jr., L. Barniskis, and T. I. Lidsky, “Persistent cognitive and motor deficits following acute hydrogen sulphide poisoning,” Occup Med (Lond), vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 255-60, May 1998. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9800424.

- W. W. Burnett, E. G. King, M. Grace, and W. F. Hall, “Hydrogen sulfide poisoning: review of 5 years’ experience,” Canadian Medical Association journal, vol. 117, no. 11, pp. 1277-80, Dec 3 1977. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/144553.

- M. Arnold, R. M. Dufresne, B. C. Alleyne, and P. J. Stuart, “Health implication of occupational exposures to hydrogen sulfide,” Journal of occupational medicine. : official publication of the Industrial Medical Association, vol. 27, no. 5, pp. 373-6, May 1985. [CrossRef]

- L. C. McCabe and G. D. Clayton, “Air pollution by hydrogen sulfide in Poza Rica, Mexico; an evaluation of the incident of Nov. 24, 1950,” A.M.A. archives of industrial hygiene and occupational medicine, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 199-213, Sep 1952. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14952044.

- G. Gerasimon, S. Bennett, J. Musser, and J. Rinard, “Acute hydrogen sulfide poisoning in a dairy farmer,” Clinical toxicology, vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 420-3, May 2007. [CrossRef]

- V. L. Feigin et al., “The global burden of neurological disorders: translating evidence into policy,” Lancet Neurol, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 255-265, Mar 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. L. Feigin and T. Vos, “Global Burden of Neurological Disorders: From Global Burden of Disease Estimates to Actions,” Neuroepidemiology, vol. 52, no. 1-2, pp. 1-2, 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Yang, G. Chen, and R. Zhang, “Estimated Public Health Exposure to H2S Emissions from a Sour Gas Well Blowout in Kaixian County, China,” Aerosol and Air Quality Research, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 430-443, 2006.

- D. X. Wang, “[A review of 152 cases of acute poisoning of hydrogen sulfide],” Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi, vol. 23, no. 6, pp. 330-2, Nov 1989. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2697541.

- B. Tvedt, K. Skyberg, O. Aaserud, A. Hobbesland, and T. Mathiesen, “Brain damage caused by hydrogen sulfide: a follow-up study of six patients,” American journal of industrial medicine, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 91-101, 1991. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1867221.

- B. Nam et al., “In vivo detection of hydrogen sulfide in the brain of live mouse: application in neuroinflammation models,” Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, vol. 49, no. 12, pp. 4073-4087, Oct 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Haouzi, T. Sonobe, and A. Judenherc-Haouzi, “Hydrogen sulfide intoxication induced brain injury and methylene blue,” Neurobiol Dis, p. 104474, May 16 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Q. Mooyaart et al., “Outcome after hydrogen sulphide intoxication,” Resuscitation, vol. 103, pp. 1-6, Jun 2016. [CrossRef]

- U. B. Gaitonde, R. J. Sellar, and A. E. O’Hare, “Long term exposure to hydrogen sulphide producing subacute encephalopathy in a child,” British medical journal, vol. 294, no. 6572, p. 614, Mar 7 1987. [CrossRef]

- m. w. warenycia et al., “Acute Hydrogen sulfide poisoning,” Biochemical Pharmacology, research journal vol. 38, no. 6, 1989.

- H. B. Leavesley, L. Li, K. Prabhakaran, J. L. Borowitz, and G. E. Isom, “Interaction of cyanide and nitric oxide with cytochrome c oxidase: implications for acute cyanide toxicity,” Toxicol Sci, vol. 101, no. 1, pp. 101-11, Jan 2008. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Bennett, G. W. Mlady, Y. H. Kwon, and G. M. Rose, “Chronic in vivo sodium azide infusion induces selective and stable inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase,” J Neurochem, vol. 66, no. 6, pp. 2606-11, Jun 1996. [CrossRef]

- T. Wieloch, “Neurochemical correlates to selective neuronal vulnerability,” Progress in brain research, vol. 63, pp. 69-85, 1985. [CrossRef]

- T. H. Milby and R. C. Baselt, “Hydrogen sulfide poisoning: clarification of some controversial issues,” American journal of industrial medicine, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 192-5, Feb 1999. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9894543.

- Kasamo et al., “Chronological changes of MRI findings on striatal damage after acute cyanide intoxication: pathogenesis of the damage and its selectivity, and prevention for neurological sequelae: a case report,” Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, vol. 243, no. 2, pp. 71-4, 1993. [CrossRef]

- F. Carella, M. P. Grassi, M. Savoiardo, P. Contri, B. Rapuzzi, and A. Mangoni, “Dystonic-Parkinsonian syndrome after cyanide poisoning: clinical and MRI findings,” J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, vol. 51, no. 10, pp. 1345-8, Oct 1988. [CrossRef]

- D. S. Sax and F. A. Mettler, “Mechanisms of azide ataxia--result of a chemical cerebellar decortication,” Transactions of the American Neurological Association, vol. 96, pp. 301-5, 1971. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4400653.

- S. A. Luse, F. A. Mettler, and W. Blank, “An ultrastructural study of lesions induced by sodium azide in the primate brain,” Transactions of the American Neurological Association, vol. 95, pp. 57-8, 1970. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4998769.

- R. N. Auer, T. Wieloch, Y. Olsson, and B. K. Siesjo, “The distribution of hypoglycemic brain damage,” Acta neuropathologica, vol. 64, no. 3, pp. 177-91, 1984. [CrossRef]

- D. S. Kim, C. M. Santana Maldonado, C. Giulivi, and W. K. Rumbeiha, “Metabolomic Signatures of Brainstem in Mice following Acute and Subchronic Hydrogen Sulfide Exposure,” Metabolites, vol. 14, no. 1, Jan 14 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. S. Kim et al., “Investigations into hydrogen sulfide-induced suppression of neuronal activity in vivo and calcium dysregulation in vitro,” Toxicol Sci, vol. 192, no. 2, pp. 247-64, Mar 6 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Park and C. H. Lee, “The Impact of Pulmonary Disorders on Neurological Health (Lung-Brain Axis),” Immune Netw, vol. 24, no. 3, p. e20, Jun 2024. [CrossRef]

- O. Bajinka, L. Simbilyabo, Y. Tan, J. Jabang, and S. A. Saleem, “Lung-brain axis,” Crit Rev Microbiol, vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 257-269, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Baldelli, F. H. Green, and R. N. Auer, “Sulfide toxicity: mechanical ventilation and hypotension determine survival rate and brain necrosis,” Journal of applied physiology, vol. 75, no. 3, pp. 1348-53, Sep 1993. [CrossRef]

- Y. Shen et al., “Case series and clinical analysis of acute hydrogen sulfide poisoning: Experience from 10 cases at a hospital in Zhoushan,” Toxicol Ind Health, p. 7482337241308388, Dec 20 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jiang et al., “Hydrogen Sulfide-Mechanisms of Toxicity and Development of an Antidote,” Scientific reports, vol. 6, p. 20831, 2016. [CrossRef]

- N. S. Cheung, Z. F. Peng, M. J. Chen, P. K. Moore, and M. Whiteman, “Hydrogen sulfide induced neuronal death occurs via glutamate receptor and is associated with calpain activation and lysosomal rupture in mouse primary cortical neurons,” Neuropharmacology, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 505-14, Sep 2007. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Jett and S. M. Spriggs, “Translational research on chemical nerve agents,” Neurobiol Dis, vol. 133, p. 104335, Jan 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Mart and L. B. Ware, “The long-lasting effects of the acute respiratory distress syndrome,” Expert Rev Respir Med, vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 577-586, Jun 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. P. Kapfhammer, H. B. Rothenhausler, T. Krauseneck, C. Stoll, and G. Schelling, “Posttraumatic stress disorder and health-related quality of life in long-term survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome,” Am J Psychiatry, vol. 161, no. 1, pp. 45-52, Jan 2004. [CrossRef]

- R. O. Hopkins, L. K. Weaver, D. Pope, J. F. Orme, E. D. Bigler, and L. V. Larson, “Neuropsychological sequelae and impaired health status in survivors of severe acute respiratory distress syndrome,” Am J Respir Crit Care Med, vol. 160, no. 1, pp. 50-6, Jul 1999. [CrossRef]

- S. Herridge et al., “Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome,” N Engl J Med, vol. 364, no. 14, pp. 1293-304, Apr 7 2011. [CrossRef]

- E. Mikkelsen et al., “Cognitive, mood and quality of life impairments in a select population of ARDS survivors,” Respirology, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 76-82, Jan 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Wilcox, N. E. Brummel, K. Archer, E. W. Ely, J. C. Jackson, and R. O. Hopkins, “Cognitive dysfunction in ICU patients: risk factors, predictors, and rehabilitation interventions,” Crit Care Med, vol. 41, no. 9 Suppl 1, pp. S81-98, Sep 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Herridge et al., “Recovery and outcomes after the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in patients and their family caregivers,” Intensive Care Med, vol. 42, no. 5, pp. 725-738, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. W. Warenycia et al., “Acute hydrogen sulfide poisoning. Demonstration of selective uptake of sulfide by the brainstem by measurement of brain sulfide levels,” Biochem Pharmacol, vol. 38, no. 6, pp. 973-81, Mar 15 1989. [CrossRef]

- R. P. Smith, R. Kruszyna, and H. Kruszyna, “Management of acute sulfide poisoning. Effects of oxygen, thiosulfate, and nitrite,” Archives of environmental health, vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 166-9, May-Jun 1976. [CrossRef]

- A. Judenherc-Haouzi et al., “Methylene blue counteracts H2S toxicity-induced cardiac depression by restoring L-type Ca channel activity,” American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology, vol. 310, no. 11, pp. R1030-44, Jun 1 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. Sonobe, B. Chenuel, T. K. Cooper, and P. Haouzi, “Immediate and Long-Term Outcome of Acute H2S Intoxication Induced Coma in Unanesthetized Rats: Effects of Methylene Blue,” miR oxidative stress, vol. 10, no. 6, p. e0131340, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Haouzi, N. Tubbs, J. Cheung, and A. Judenherc-Haouzi, “Methylene Blue Administration During and After Life-Threatening Intoxication by Hydrogen Sulfide: Efficacy Studies in Adult Sheep and Mechanisms of Action,” Toxicol Sci, vol. 168, no. 2, pp. 443-459, Apr 1 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Judenherc-Haouz, T. Sonobe, V. S. Bebarta, and P. Haouzi, “On the Efficacy of Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation and Epinephrine Following Cyanide- and H(2)S Intoxication-Induced Cardiac Asystole,” Cardiovascular toxicology, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 436-449, Oct 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Sonobe and P. Haouzi, “H2S induced coma and cardiogenic shock in the rat: Effects of phenothiazinium chromophores,” Clinical toxicology, vol. 53, no. 6, pp. 525-39, Jul 2015. [CrossRef]

- Haouzi, T. Sonobe, and B. Chenuel, “Oxygen-related chemoreceptor drive to breathe during H(2)S infusion,” Respiratory physiology & neurobiology, vol. 201, pp. 24-30, Sep 15 2014. [CrossRef]

- Haouzi, T. Sonobe, N. Torsell-Tubbs, B. Prokopczyk, B. Chenuel, and C. M. Klingerman, “In vivo interactions between cobalt or ferric compounds and the pools of sulphide in the blood during and after H2S poisoning,” Toxicol Sci, vol. 141, no. 2, pp. 493-504, Oct 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Cronican, K. L. Frawley, H. Ahmed, L. L. Pearce, and J. Peterson, “Antagonism of Acute Sulfide Poisoning in Mice by Nitrite Anion without Methemoglobinemia,” Chem Res Toxicol, vol. 28, no. 7, pp. 1398-408, Jul 20 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ding et al., “A rapid evaluation of acute hydrogen sulfide poisoning in blood based on DNA-Cu/Ag nanocluster fluorescence probe,” Scientific reports, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 9638, Aug 29 2017. [CrossRef]

- G. Lucchini, D. C. Dorman, A. Elder, and B. Veronesi, “Neurological impacts from inhalation of pollutants and the nose-brain connection,” Neurotoxicology, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 838-41, Aug 2012. [CrossRef]

- C. L. Mumaw et al., “Microglial priming through the lung-brain axis: the role of air pollution-induced circulating factors,” FASEB J, vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 1880-91, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- W. K. Rumbeiha, D. S. Kim, A. Min, M. Nair, and C. Giulivi, “Disrupted brain mitochondrial morphology after in vivo hydrogen sulfide exposure,” Scientific reports, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 18129, Oct 24 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. S. Kim et al., “Transcriptomic profile analysis of brain inferior colliculus following acute hydrogen sulfide exposure,” Toxicology, vol. 430, p. 152345, Jan 30 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. S. Kim et al., “Broad spectrum proteomics analysis of the inferior colliculus following acute hydrogen sulfide exposure,” Toxicology and applied pharmacology, vol. 355, pp. 28-42, Sep 15 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Anantharam et al., “Midazolam Efficacy Against Acute Hydrogen Sulfide-Induced Mortality and Neurotoxicity,” Journal of medical toxicology : official journal of the American College of Medical Toxicology, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 79-90, Mar 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Anantharam et al., “Cobinamide is effective for treatment of hydrogen sulfide-induced neurological sequelae in a mouse model,” Ann N Y Acad Sci, vol. 1408, no. 1, pp. 61-78, Nov 2017. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).