Submitted:

21 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Synthesis and Optical Characterization of ICT Complex Between TiO2 and DHQ

2.2. Biological Effects of ICT Complex Between TiO2 and DHQ

2.2.1. Treatments Preparation

2.2.2. Cell Culture

2.2.3. Cytotoxicity Evaluation

2.2.4. H2DCFDA Assay (2′,7′-Dichlorofluorescin Diacetate)

2.3. Comet Assay

2.4. Antimicrobial Activity

3. Results and Discussions

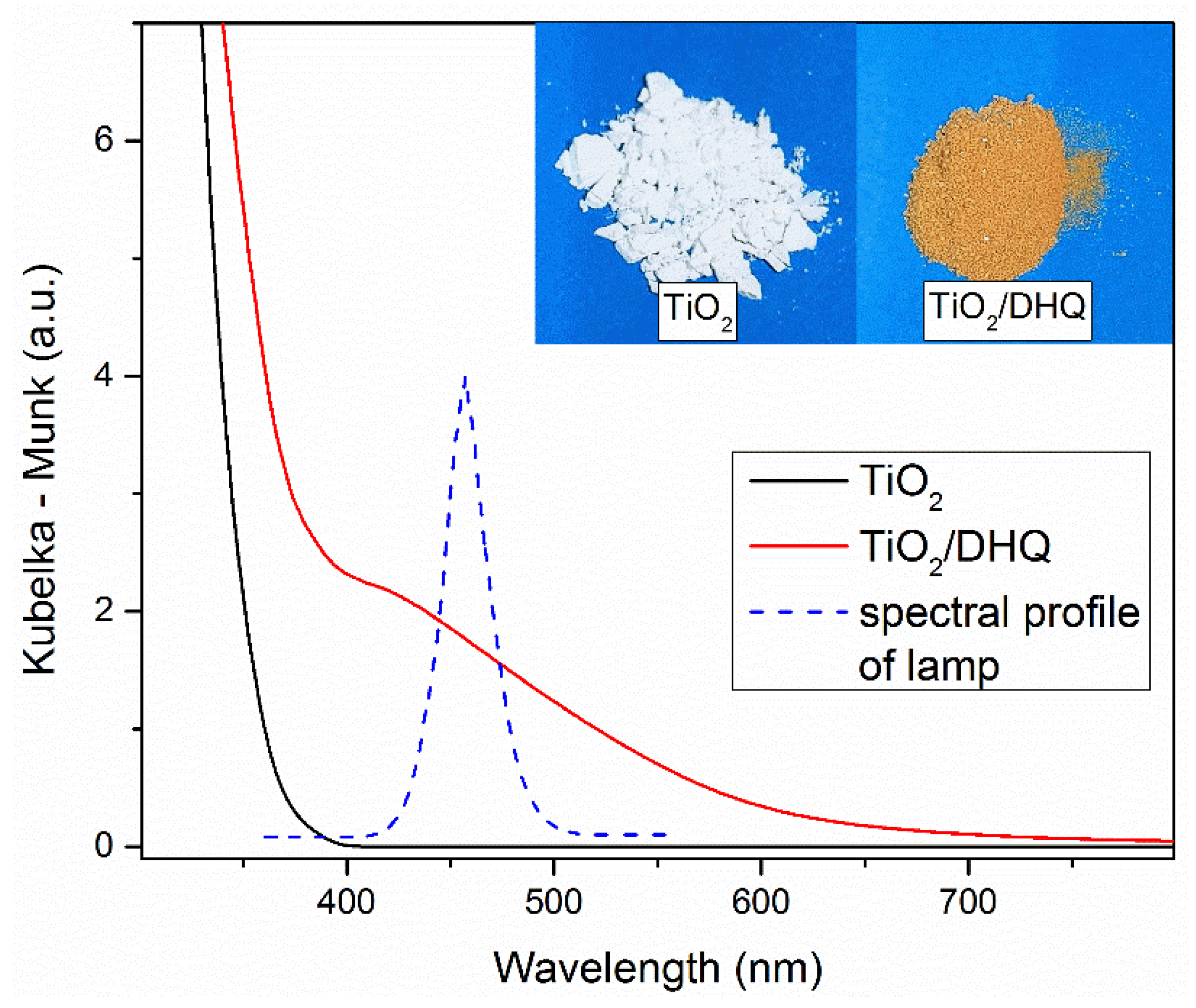

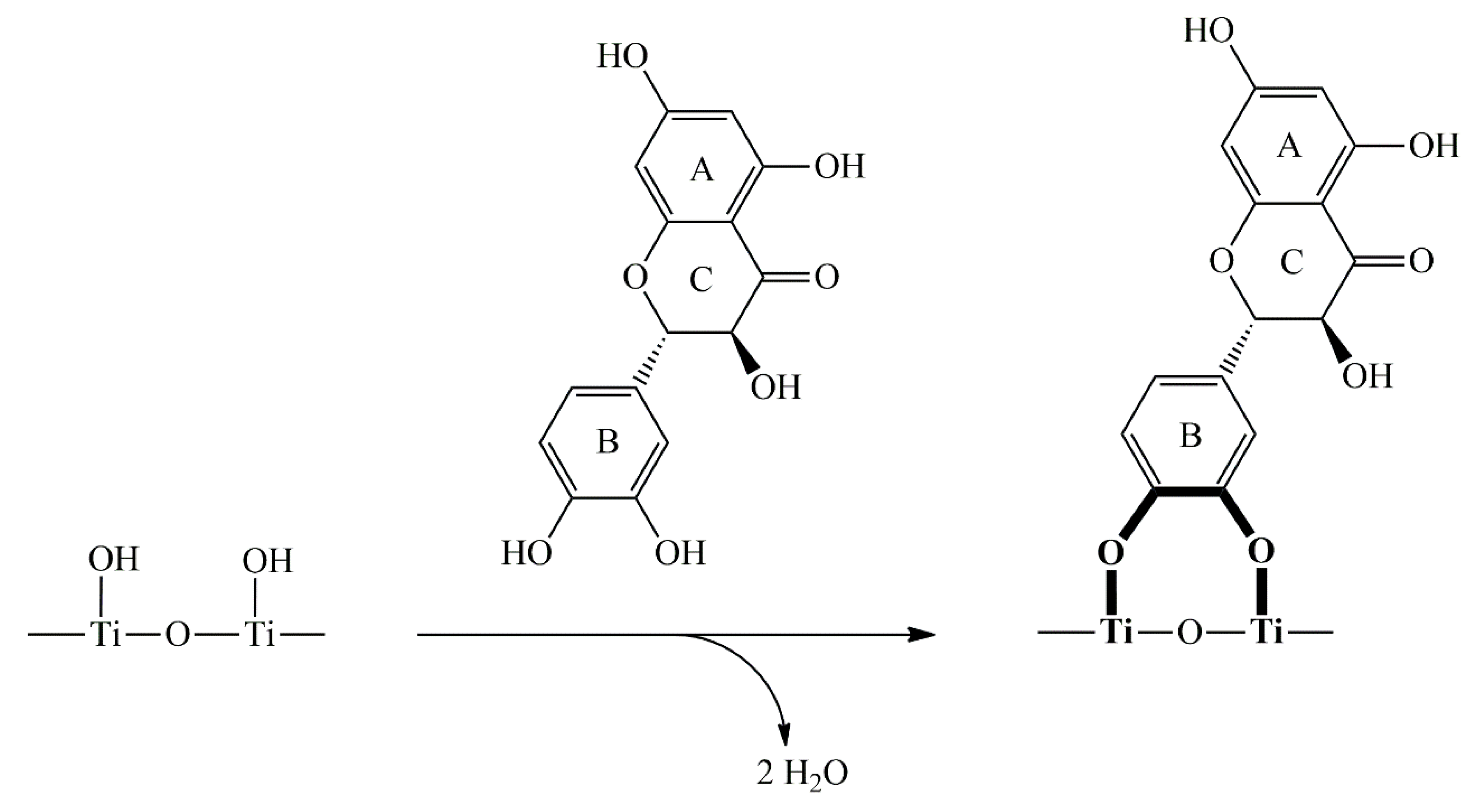

3.1. Basic Properties of ICT Complex Between TiO2 and DHQ

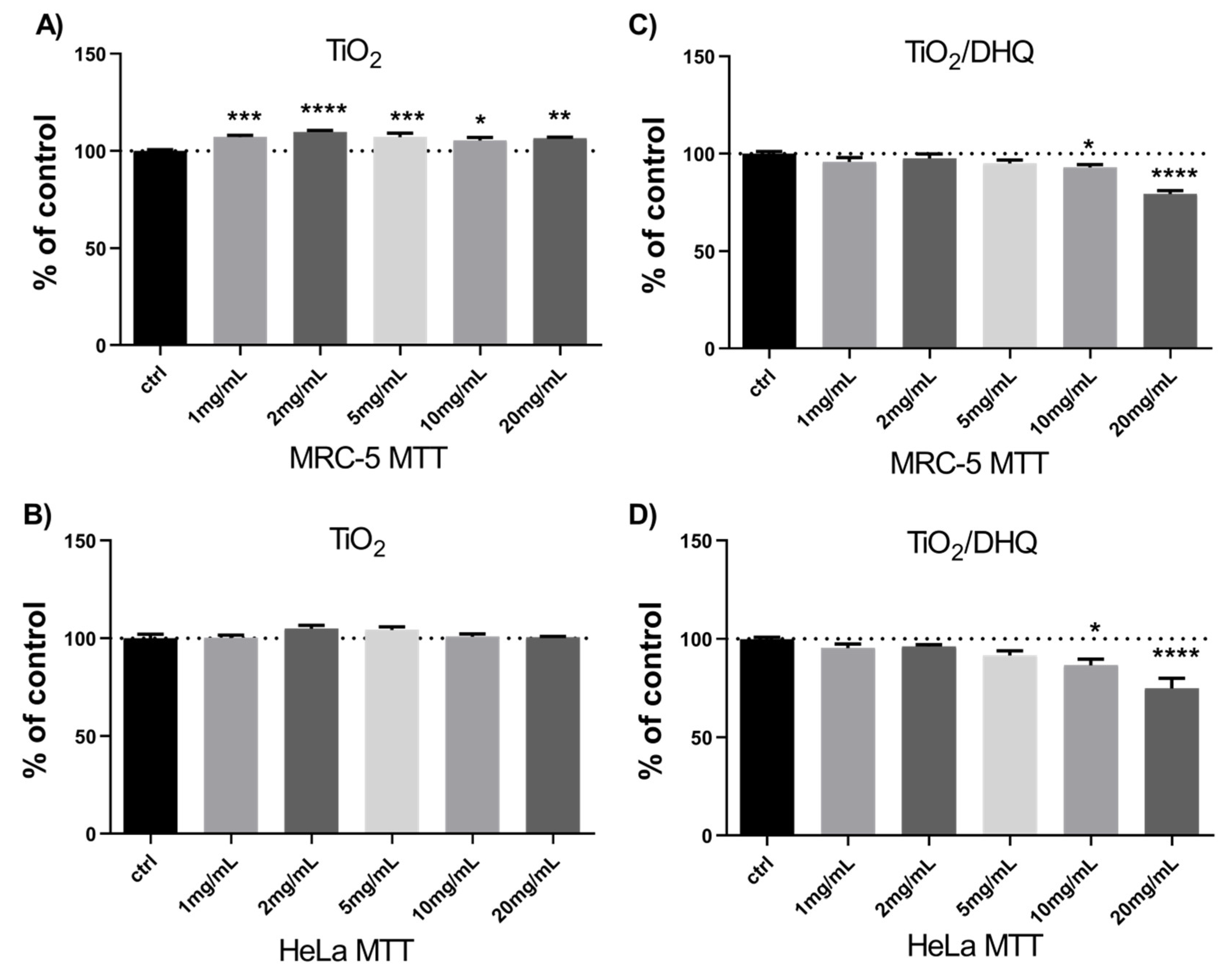

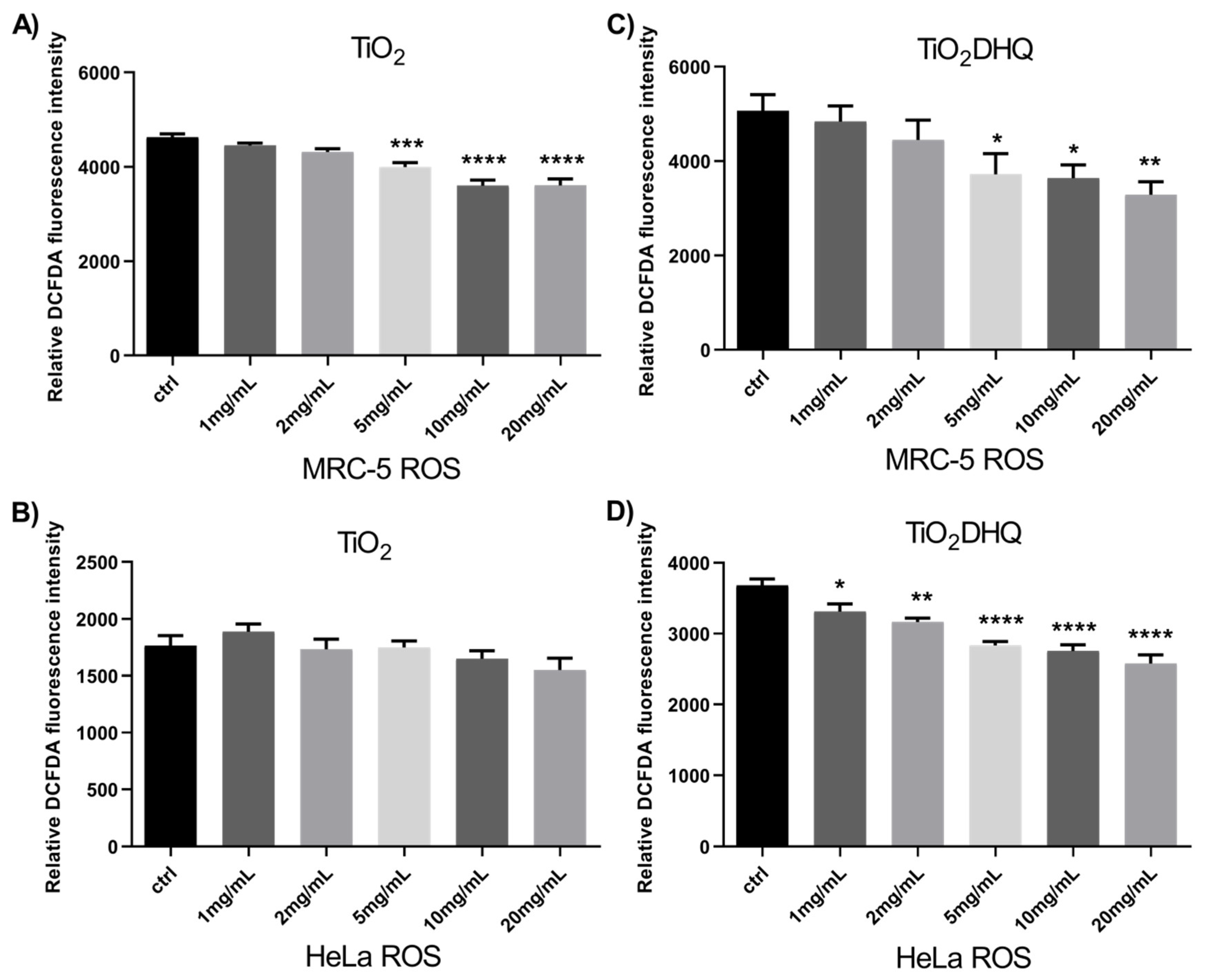

3.2. Cytotoxicity

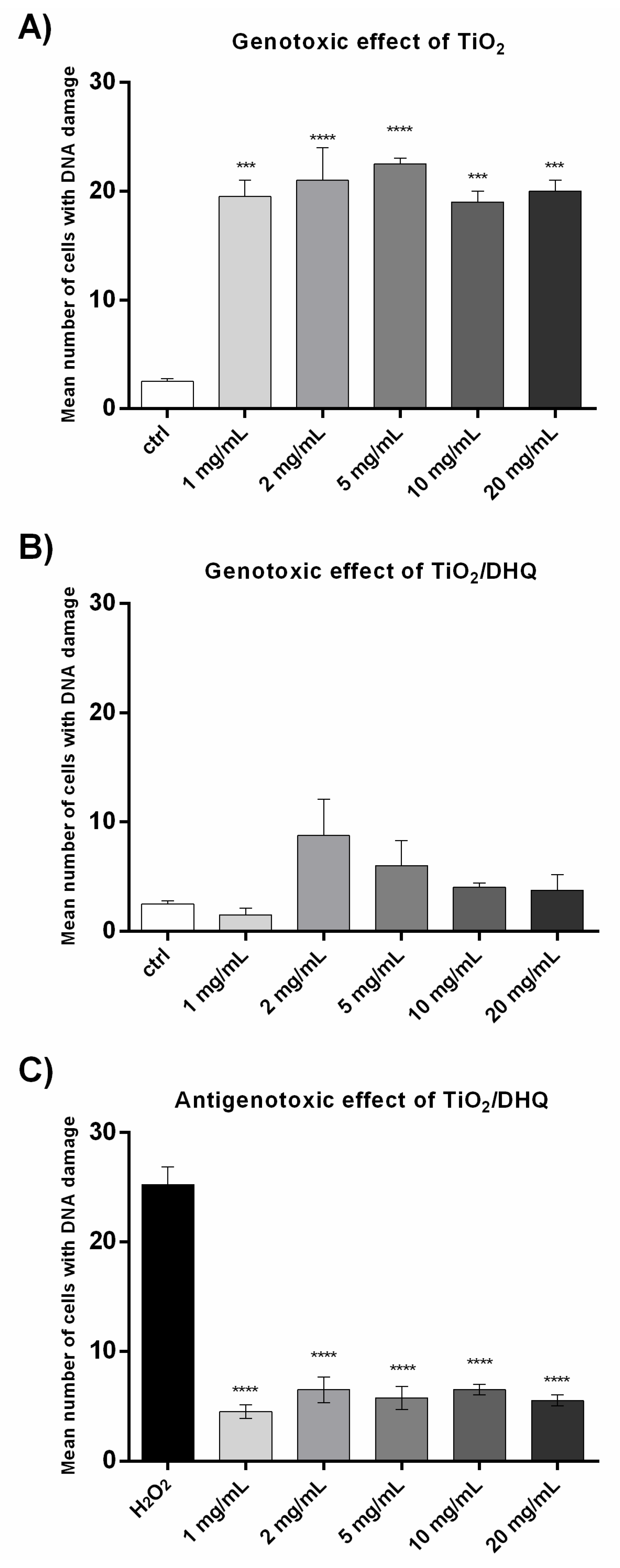

3.4. Genotoxicity and Antigenotoxicity

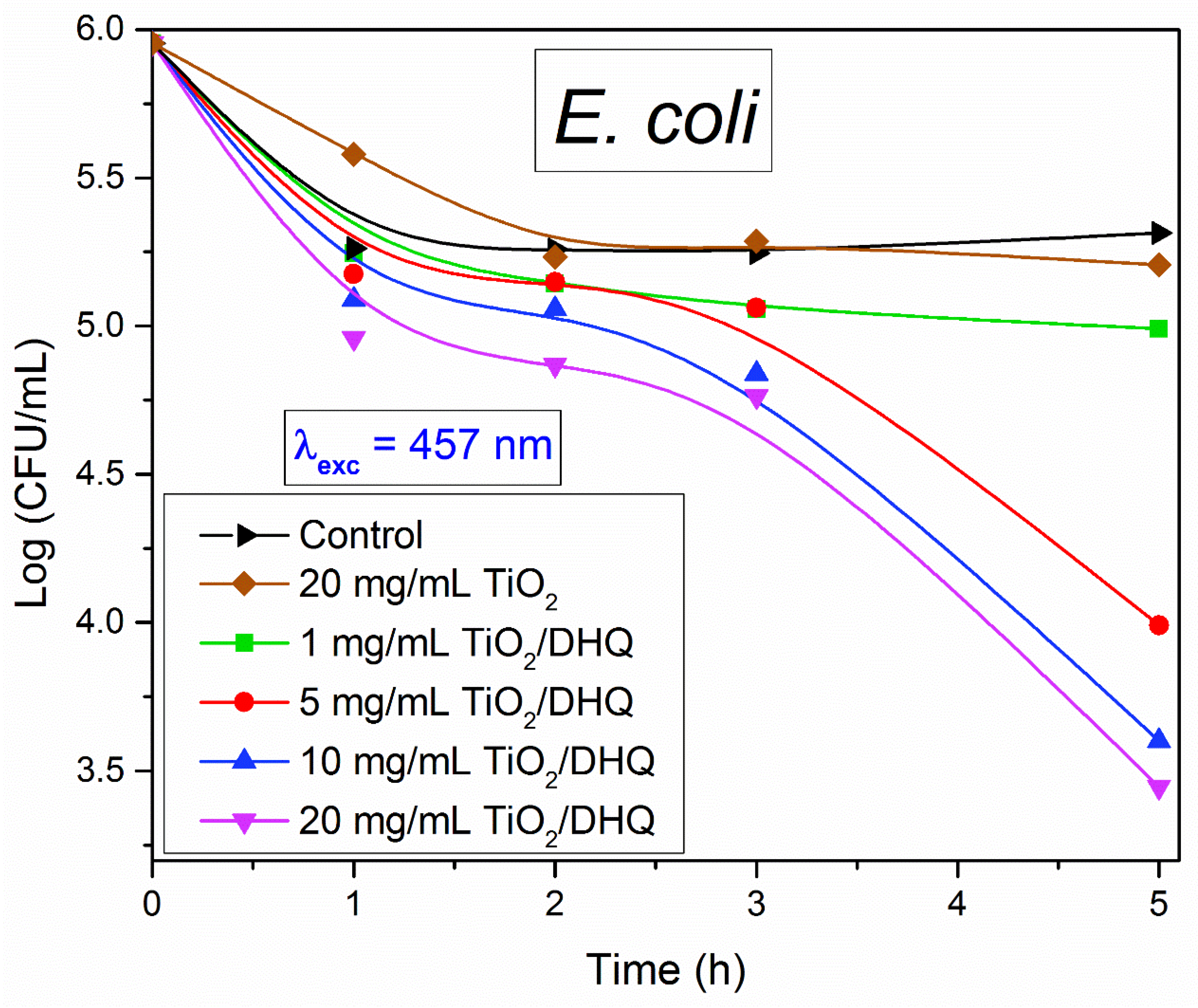

3.5. Preliminary Antimicrobial Tests

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoffmann, M.R.; Martin, S.T.; Choi, W.; Bahnemann, D.W. Environmental applications of semiconductor photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carré, G.; Hamon, E.; Ennahar, S.; Estner, M.; Lett, M.C.; Horvatovich, P.; Gies, J.P.; Keller, V.; Keller, N.; Andrea, P. TiO2 Photocatalysis Damages Lipids and Proteins in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2014, 80, 2573–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wu, Q.; Meng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, C. Recent advances in photocatalytic self-cleaning performances of TiO2-based building materials. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 20584–20597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziental, D.; Czarczynska-Goslinska, B.; Mlynarczyk, D.T.; Glowacka-Sobotta, A.; Stanisz, B.; Goslinski, T.; Sobotta, L. Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles: Prospects and Applications in Medicine. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouirfa, H.; Bouloussa, H.; Migonney, V.; Falentin-Daudré, C. Review of titanium surface modification techniques and coatings for antibacterial applications. Acta Biomater. 2019, 83, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nešić, A.; Gordić, M.; Davidović, S.; Radovanović, Ž.; Nedeljković, J.; Smirnova, I.; Gurikov, P. Pectin-based nanocomposite aerogels for potential insulated food packaging application. Carbohyd. Polym. 2018, 195, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, A.J.; AL-Anbari, R.H.; Kadhim, G.R.; Salame, C.T. Exploring potential Environmental applications of TiO2 Nanoparticles. Energy Procedia 2017, 119, 332–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.T.; Nguyen, L.M.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; Liew, R.K.; Nguyen, D.T.C.; Tran, T.V. Recent advances on botanical biosynthesis of nanoparticles for catalytic, water treatment and agricultural applications: A review. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 827, 154160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajh, T.; Nedeljković, J.M.; Chen, L.X.; Poluektov, O.; Thurnauer, M.C. Improving optical and charge separation properties of nanocrystalline TiO2 by surface modification with vitamin C. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 3515–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janković, I.A.; Šaponjić, Z.V.; Čomor, M.I.; Nedeljković, J.M. Surface modification of colloidal TiO2 nanoparticles with bidentate benzene derivatives. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 12645–12652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazić, V.; Nedeljković, J.M. Photocatalytic Reactions over TiO2-Based Interfacial Charge Transfer Complexes. Catalysts 2024, 14, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janković, I.A.; Šaponjić, Z.V.; Džunuzović, E.S.; Nedeljković, J.M. New hybrid properties of TiO2 nanoparticles surface modified with catecholate type ligands. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2010, 5, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savić, T.D.; Janković, I.A.; Šaponjić, Z.V.; Čomor, M.I.; Veljković, D.Ž.; Zarić, S.D.; Nedeljković, J.M. Surface modification of anatase nanoparticles with fused catecholate type ligands: a combined DFT and experimental study of optical properties. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 1612–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savić, T.D.; Čomor, M.I.; Nedeljković, J.M.; Veljković, D.Ž.; Zarić, S.D.; Rakić, V.M.; Janković, I.A. The effect of substituents on the surface modification of anatase nanoparticles with catecholate-type ligands: a combined DFT and experimental study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 20796–20805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higashimoto, S.; Nishi, T.; Yasukawa, M.; Azuma, M.; Sakata, Y.; Kobayashi, H. Photocatalysis of titanium dioxide modified by catechol-type interfacial surface complexes (ISC) with different substituted groups. J. Catal. 2015, 329, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milićević, B.; Ðorđević, V.; Lončarević, D.; Ahrenkiel, S.P.; Dramićanin, M.D.; Nedeljković, J.M. Visible light absorption of surface modified TiO2 powders with bidentate benzene derivatives. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 2015, 217, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savić, T.D.; Šaponjić, Z.V.; Čomor, M.I.; Nedeljković, J.M.; Dramićanin, M.D.; Nikolić, M.G.; Veljković, D.Ž.; Zarić, S.D.; Janković, I.A. Surface modification of anatase nanoparticles with fused ring salicylate-type ligands (3-hydroxy-2-naphtoic acids): a combined DFT and experimental study of optical properties. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 7601–7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boz, D.K.; Garcia, G.A.; Nahon, L.; Sredojevic, D.; Lazic, V.; Vukoje, I.; Ahrenkiel, S.P.; Djokovic, V. Ž. Šljivančanin; Nedeljkovic, J.M. Interfacial Charge Transfer Transitions in Colloidal TiO2 Nanoparticles Functionalized with Salicylic acid and 5-Aminosalicylic acid: A Comparative Photoelectron Spectroscopy and DFT Study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 29057–29066. [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa, J.; Matsumura, S.; Hanaya, M. A single Ti‒O‒C linkage induces interfacial charge-transfer transitions between TiO2 and a π-conjugated molecule. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2016, 657, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, J.; Eda, T.; Giorgi, G.; Hanaya, M. Visible-to-Near-IR Wide-Range Light Harvesting by Interfacial Charge-Transfer Transitions between TiO2 and p-Aminophenol and Evidence of Direct Electron Injection to the Conduction Band of TiO2. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 18710–18716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieriková, Z.; Dvoranová, D.; Brezová, V.; Džunuzović, E.; Sredojević, D.N.; Lazić, V.; Nedeljković, J.M. Visible-light-responsive surface-modified TiO2 powder with 4-chlorophenol: A combined experimental and DFT study. Opt. Mater. 2019, 89, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, J.; Kato, S.; Hanaya, M. Substituent effects on interfacial charge-transfer transitions in a TiO2-phenol complex. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2023, 827, 140688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, S.; Abe, C.; Torimoto, T.; Ohtani, B. Photochemical hydrogen evolution from aqueous triethanolamine solutions sensitized by binaphthol-modified titanium(IV) oxide under visible-light irradiation, J. Photoch. Photobio. A 2003, 160, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, B.; Peng, C.; Lu, P.; He, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Q. Fabrication of Tiron-TiO2 charge-transfer complex with excellent visible-light photocatalytic performance, Mat. Chem. Phys. 2016, 184, 298–305. [Google Scholar]

- Vukoje, I.; Kovač, T.; Džunuzović, J.; Džunuzović, E.; Lončarević, D.; Ahrenkiel, S.P.; Nedeljković, J.M. Photocatalytic ability of visible-light-responsive TiO2 nanoparticles, J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 18560–18569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazić, V.; Sredojević, D.; Ćirić, A.; Nedeljković, J.M.; Zelenková, G.; Férová, M.; Zelenka, T.; Chavhan, M.P.; Slovák, V. The photocatalytic ability of visible-light-responsive interfacial charge transfer complex between TiO2 and Tiron, J. Photoch. Photobio. A 2024, 449, 115394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kose, O. In vitro toxicity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on human lung cells – impact of the physicochemical features, PhD thesis, Chemical and Process Wngineering, Université de Lyon, 2020, in English.

- Afşar, O.; Oltulu, Ç. Evaluation of the cytotoxic effect of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in human embryonic lung cells, Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 53, 1648–1657. [Google Scholar]

- Sredojević, D.; Lazić, V.; Pirković, A.; Periša, J.; Murafa, N.; Spremo-Potparević, B.; Živković, L.; Topalović, D.; Zarubica, A.; Krivokuća, M.J.; Nedeljković, J.M. Toxicity of silver supported by surface-modified zirconium dioxide with dihydroquercetin, Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3195.

- Nikšić, V.; Šimunková, M.M.; Dyrčíková, Z.; Dvoranová, D.; Brezová, V.; Sredojević, D.; Nedeljković, J.M.; Lazić, V. Photoinduced reactive species in interfacial charge transfer complex between TiO2 and taxifolin: DFT and EPR study, Opt. Mater. 2024, 152, 115454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriari-Khalaji, M.; Zabihi, F.; Bahi, A.; Sredojević, D.; Nedeljković, J.M.; Macharia, D.K.; Ciprian, M.; Yang, S.; Ko, F. Photon-driven bactericidal performance of surface-modified TiO2 nanofibers, J. Mater. Chem. C 2023, 11, 5796–5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajić, V.; Spremo-Potparević, B.; Živković, L.; Čabarkapa, A.; Kotur-Stevuljević, J.; Isenović, E.; Sredojević, D.; Vukoje, I.; Lazić, V.; Ahrenkiel, S.P.; Nedeljković, J.M. Surface-modified TiO2 nanoparticles with ascorbic acid: Antioxidant properties and efficiency against DNA damage in vitro, Colloid Surface B 2017, 155, 323–331.

- Lazić, V.; Pirković, A.; Sredojević, D.; Marković, J.; Papan, J.; Ahrenkiel, S.P.; Janković-Častvan, I.; Dekanski, D.; Jovanović-Krivokuća, M.; Nedeljković, J.M. Surface-modified ZrO2 nanoparticles with caffeic acid: Characterization and in vitro evaluation of biosafety for placental cells, Chem. -Biol. Interact. 2021, 347, 109618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekanski, D.; Spremo-Potparević, B.; Bajić, V.; Živković, L.; Topalović, D.; Sredojević, D.N.; Lazić, V.; Nedeljković, J.M. Acute toxicity study in mice of orally administrated TiO2 nanoparticles functionalized with caffeic acid, Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 115, 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Todorović, A.; Bobić, K.; Veljković, F.; Pejić, S.; Glumac, S.; Stanković, S.; Milovanović, T.; Vukoje, I.; Nedeljković, J.M.; Škodrić, S.R.; Pajović, S.B.; Drakulić, D. Comparable Toxicity of Surface-Modified TiO2 Nanoparticles: An In Vivo Experimental Study on Reproductive Toxicity in Rats, Antioxidants 2024, 13, 231.

- Živković, L.; Bajić, V.; Topalović, D.; Bruić, M.; Spremo-Potparević, B. Antigenotoxic Effects of Biochaga and Dihydroquercetin (Taxifolin) on H2O2-Induced DNA Damage in Human Whole Blood Cells, Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 5039372. [Google Scholar]

- Abhijit, D.; Baidya, R.; Chakraborty, T. Pharmacological basis and new insights of taxifolin: A comprehensive review, Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 142, 112004. [Google Scholar]

- Orlova, S.V.; Tatarinov, V.V.; Nikitina, E.A.; Sheremeta, A.V.; Ivlev, V.A.; Vasilev, V.G.; Paliy, K.V.; Goryainov, S.V. Molecularbiological problems of drug design and mechanism of drug action, Pharm. Chem. J. 2022, 55, 1133–1137. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhtar-Fayyad, D. Cytocompatibility of new bioceramic-based materials on human fibroblast cells (MRC-5), Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. O. 2011, 112, e137–e142. [Google Scholar]

- Tice, R.R.; Agurell, E.; Anderson, D.; Burlinson, B.; Hartmann, A.; Kobayashi, H.; Miyamae, Y.; Rojas, E.; Ryu, J.C.; Sasaki, Y.F. Single cell gel/comet assay: guidelines for in vitro and in vivo genetic toxicology testing, Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2000, 35, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.; Yu, T.W.; Phillips, B.J.; Schmezer, P. The effect of various antioxidants and other modifying agents on oxygen-radical-generated DNA damage in human lymphocytes in the comet assay, Mutat. Res. 1994, 307, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokaitytė, A.; Zaborskienė, G.; Baliukonienė, V.; Jovaišienė, J.; Gustienė, S. Cytotoxicity of carnosine, taxifolin, linalool and their combinations with acids to the cells of human cervical carcinoma (HeLa), Biologija 2018, 64, 274–284.

- Mohammed, H.A.; El-Ghaly, S.A.A.E.-S.M. F.A.Khan; Emwas, A.H.; Jaremko, M.; Almulhim, F.; Khan, R.A.; Ragab, E.A. Comparative Anticancer Potentials of Taxifolin and Quercetin Methylated Derivatives against HCT-116 Cell Lines: Effects of O-Methylation on Taxifolin and Quercetin as Preliminary Natural Leads, ACS Omega. 2022; 7, 46629–46639. [Google Scholar]

- Chahardoli, A.; Jalilian, F.; Shokoohinia, Y.; Fattahi, A. The role of quercetin in the formation of titanium dioxide nanoparticles for nanomedical applications, Toxicol. in Vitro 2023, 87, 105538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.; Feng, J.; Kang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Tang, Y. Taxifolin protects RPE cells against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis, Mol. Vis. 2017, 23, 520–528. [Google Scholar]

- Bruić, M.; Pirković, A.; Borozan, S.; Aleksić, M.N.; Krivokuća, M.J.; Spremo-Potparević, B. Antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects of taxifolin in H2O2-induced oxidative stress in HTR-8/SVneo trophoblast cell line, Reprod. Toxicol. 2024, 126, 108585. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Xie, H.; Jiang, Q.; Wei, G.; Lin, L.; Li, C.; Ou, X.; Yang, L.; Xie, Y.; Fu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, D. The mechanism of (+) taxifolin’s protective antioxidant effect for •OH-treated bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells, Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2017, 22, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svobodová, A.R.; Ryšavá, A.; Čížková, K.; Roubalová, L.; Ulrichová, J.; Vrba, J.; Zálešák, B.; Vostálová, J. Effect of the flavonoids quercetin and taxifolin on UVA-induced damage to human primary skin keratinocytes and fibroblasts, Photoch. Photobio. Sci. 2022, 21, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulla, S.; Lomada, D.; Araveti, P.B.; Srivastava, A.; Murikinati, M.K.; Reddy, K.R. Inamuddin; Reddy, M.C.; Altalhi, T. Titanium dioxide nanotubes conjugated with quercetin function as an effective anticancer agent by inducing apoptosis in melanoma cells. J. Nanostructure. Chem. 2021, 11, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, S.; Kulyar, M.F.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Boruah, P.; Asif, M. Toxicological Consequences of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) and Their Jeopardy to Human Population, Bionanoscience 2021, 11, 621–632.

- Langie, S.; Azqueta, A.; Collins, A. The comet assay: past, present, future, Front. Genet 2015, 6, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Chen, J.; Bian, Q.; Ning, J.; Yong, L.; Ou, T.; Song, Y.; Wei, S. Genotoxicity Evaluation of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles In Vivo and In Vitro: A Meta-Analysis, Toxics 2023, 11, 882.

- Ling, C.; An, H.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Lu, T.; Wang, H.; Hu, Y.; Song, G.; Liu, S. Genotoxicity Evaluation of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles in Vitro: A Systematic Review of the Literature and Meta-analysis, Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2021, 199, 2057–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Han, S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Jia, G. Advances in genotoxicity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in vivo and in vitro, NanoImpact 2022, 25, 100377.

- Chen, T.; Yan, J.; Li, Y. Genotoxicity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles, J. Food Drug Anal. 2014, 22, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazic, V.; Vukoje, I.; Milicevic, B.; Spremo-Potparevic, B.; Zivkovic, L.; Topalovic, D.; Bajic, V.; Sredojevic, D.; Nedeljkovic, J.M. Efficiency of the interfacial charge transfer complex between TiO2 nanoparticles and caffeic acid against DNA damage in vitro: a combinatorial analysis. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2019, 84, 539–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).