Submitted:

20 January 2025

Posted:

21 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

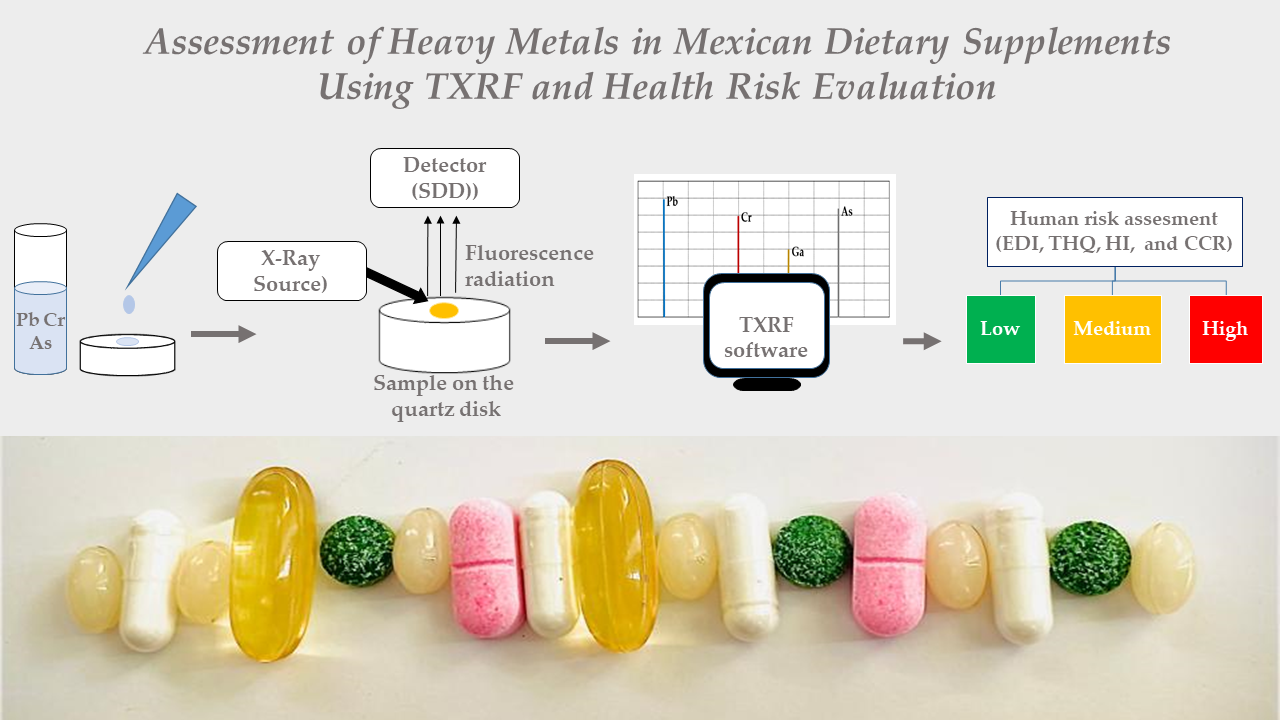

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Sample Preparation

2.4. TXRF Analysis

2.5. Quality Control

2.6. Human Health Risk Assessment

2.6.1. Estimated Daily Intake (EDI)

- C = Metal concentration in the sample in mg/kg for solid samples and mg/L for liquid samples.

- IR = Ingestion rate (calculated based on the recommended dose) in mg/day or mL/day.

- EF = Exposure frequency (260 days per year).

- ED = Exposure duration (30 years).

- BW = Body weight (70 kg).

- AT non cancer = Average exposure time (EF x ED), (365 days per year x 30 years).

2.6.2. Target Hazard Quotient (THQ) and Hazard Index (HI)

- EDI

- = Estimated Daily Intake in mg.kg -1 bw.day-1

- EDI

- RfD = Reference Dose, in mg.kg -1 bw.day-1, which represents the tolerable daily intake of the metal via oral exposure. The RfDs of lead, arsenic, and chromium were established according to different international standards (Table 1).

2.6.3. Cummulative Carcinogenic Risk (CCR)

- CSF = Cancer Slope Factor in (mg.kg -1 bw.day-1)- 1

- EDI = Estimated Daily Intake in mg.kg -1 bw.day-1

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Dietary Samples Characteristics

3.2. Quality Control

3.3. Application to Real Samples

3.3.1. Lead

3.3.2. Arsenic

3.3.3. Chromium

3.4. Human Health Risk Assessment

3.4.1. Estimated Daily Intake

3.4.2. Total Hazard Quotient and Hazard Index

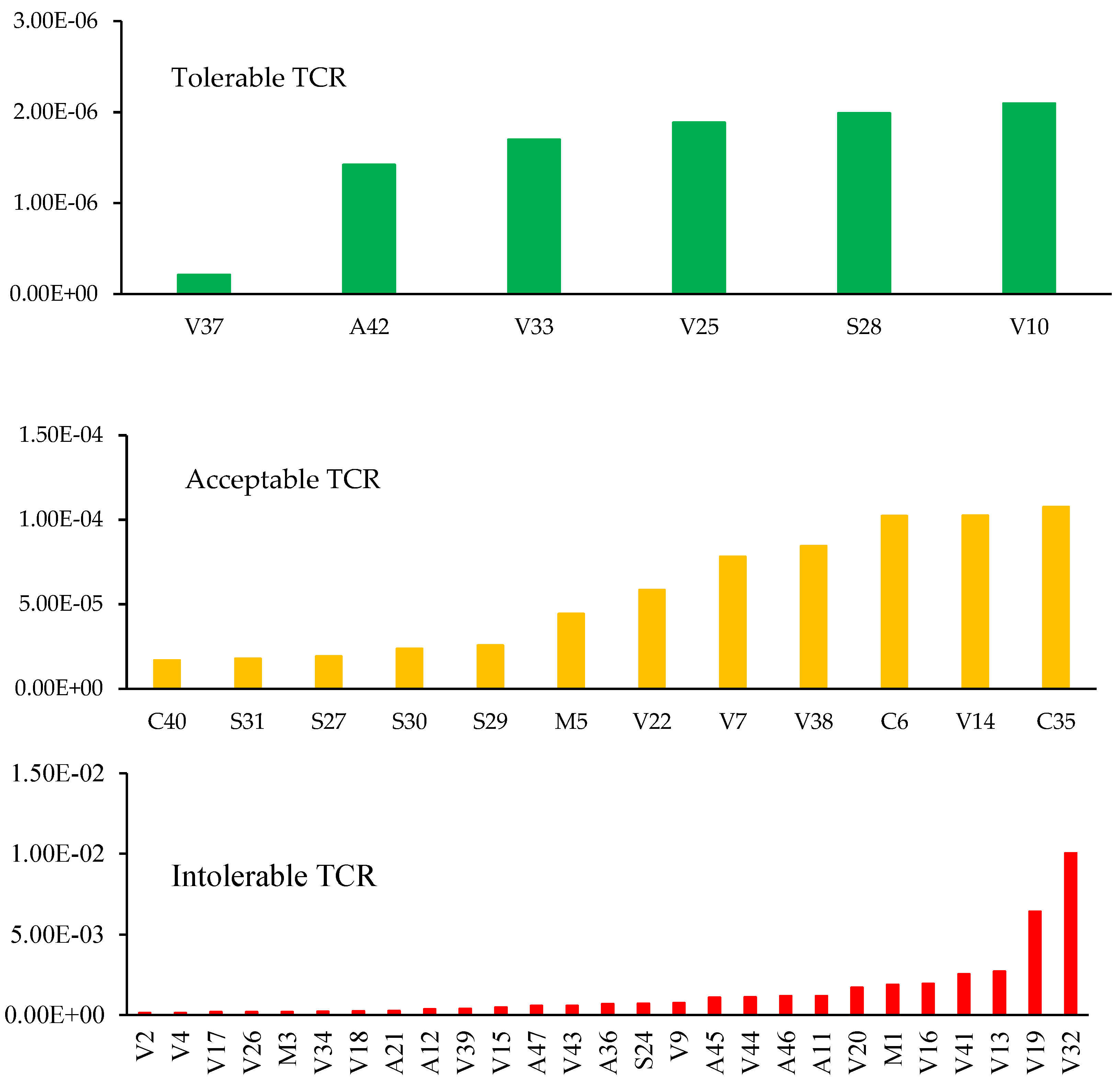

3.4.4. The Cumulative Cancer Risk (CCR)

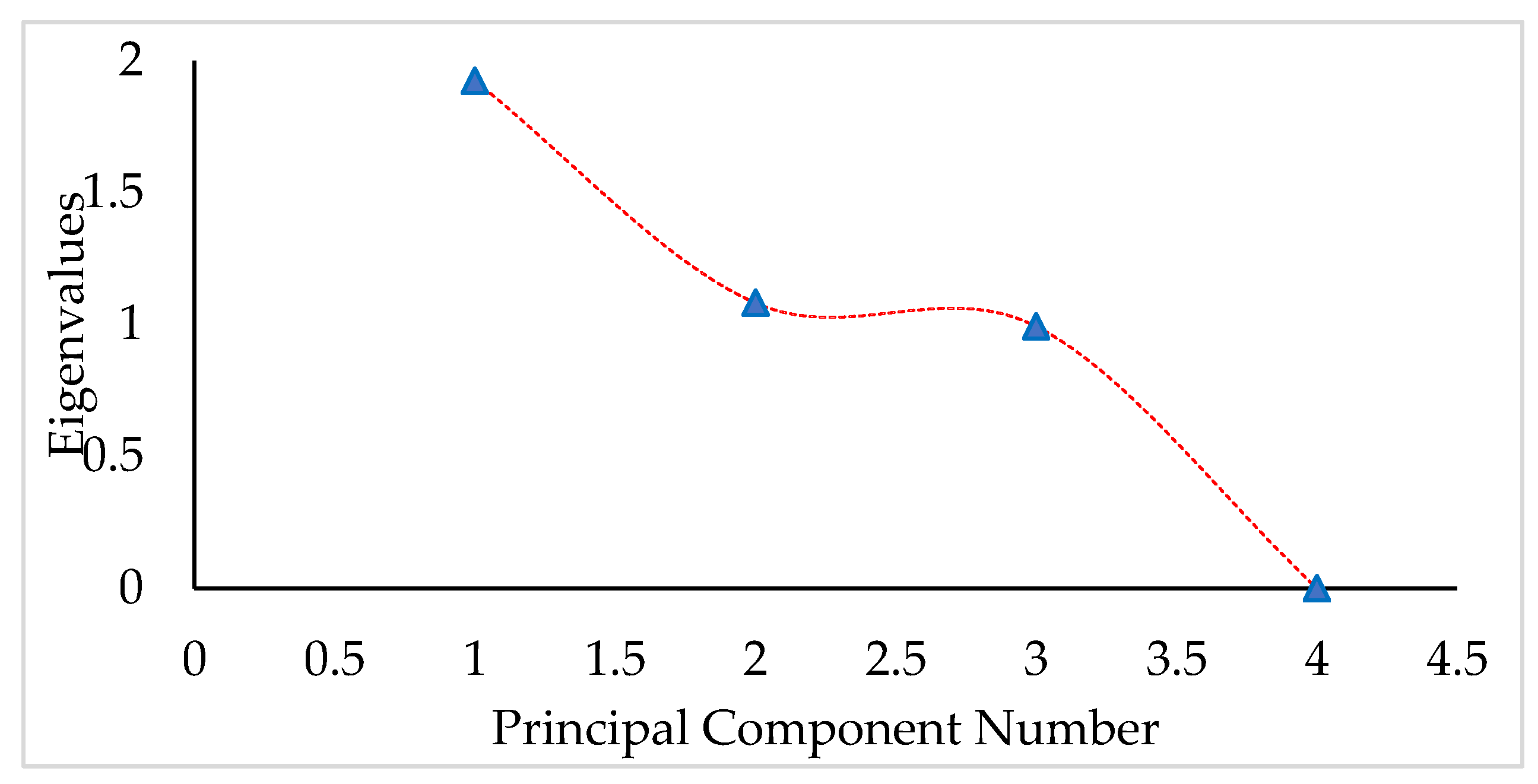

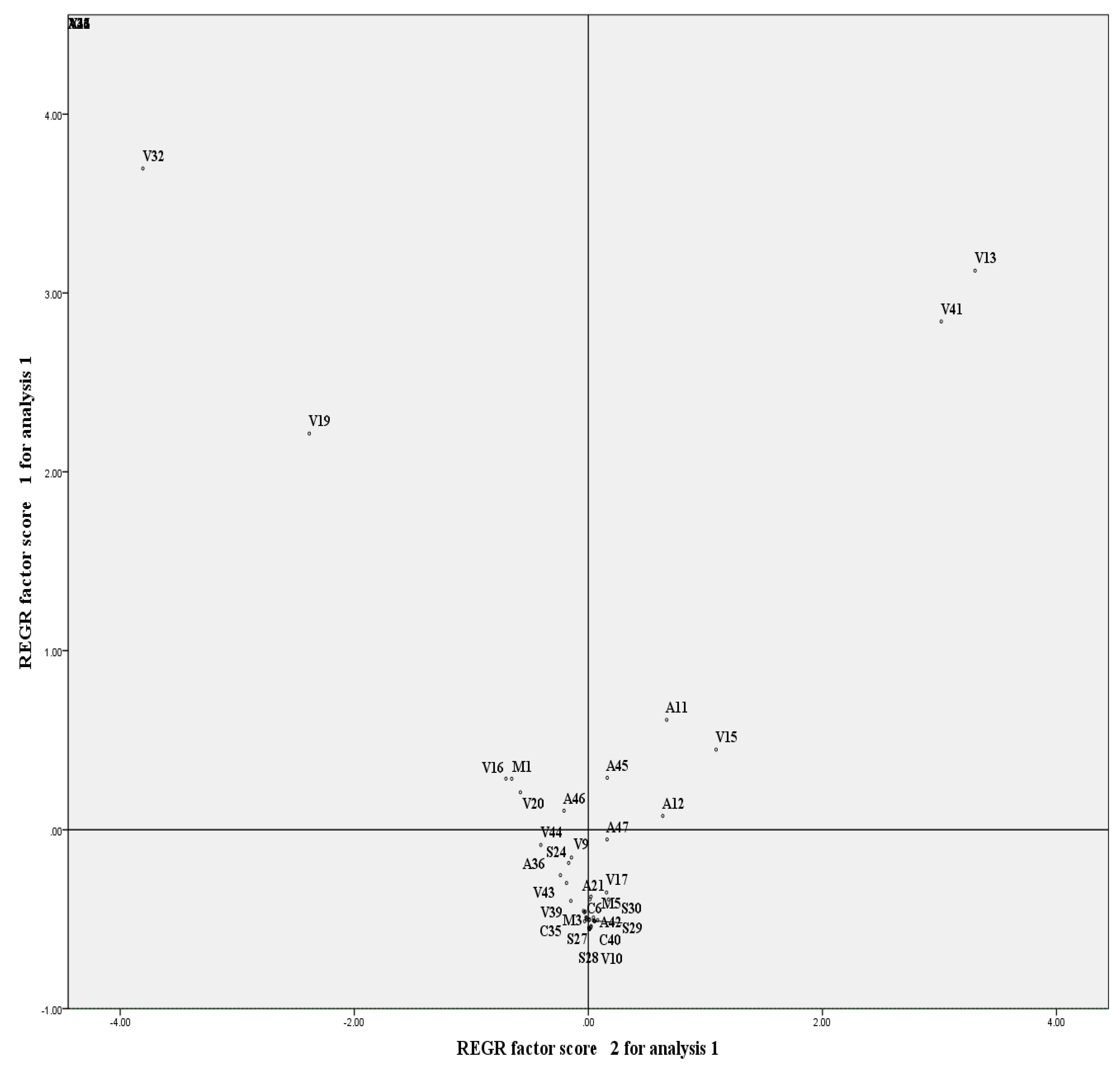

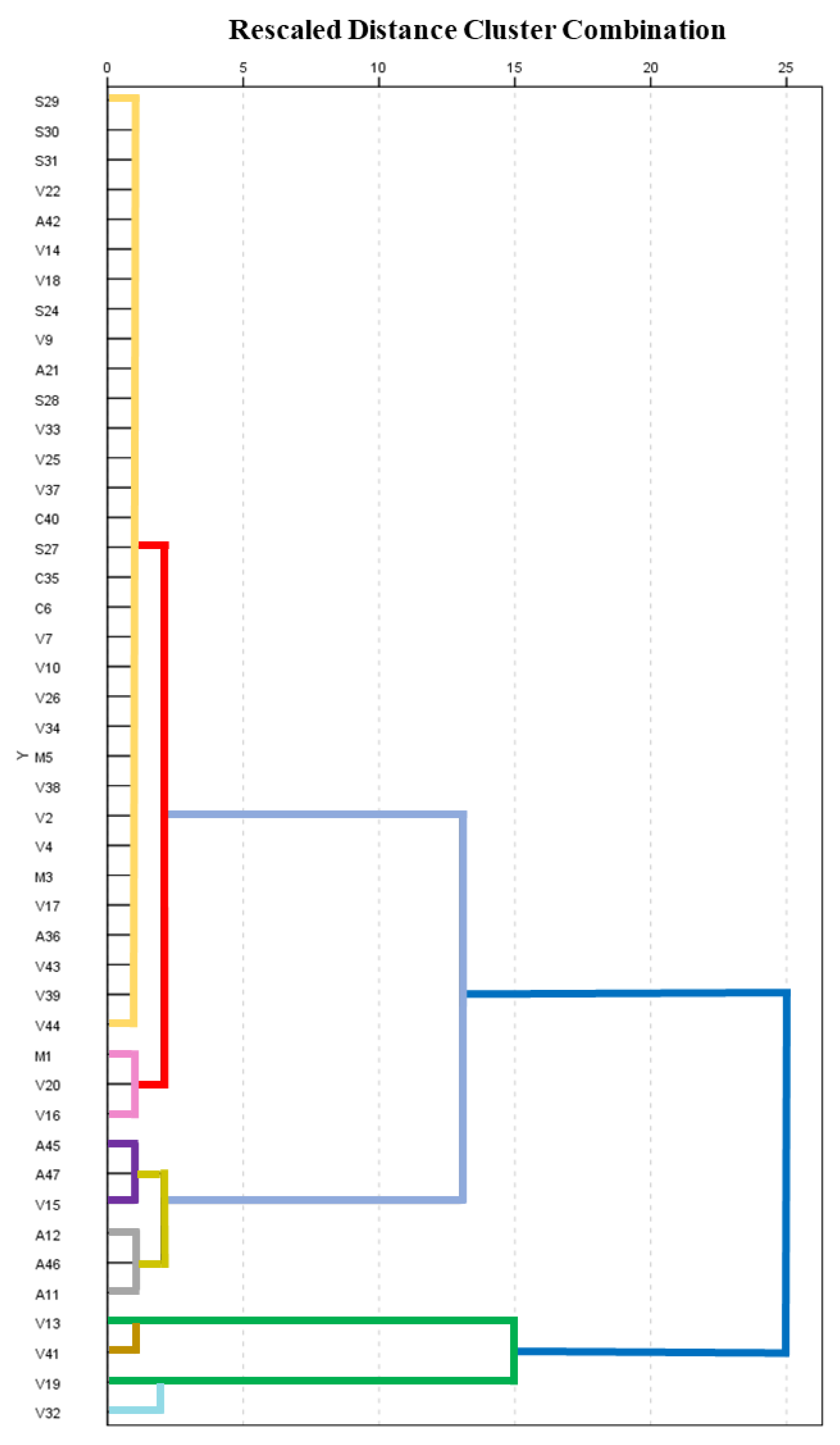

3.5. Multivariate Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Augustsson, A.; Qvarforth, A.; Engström, E.; Paulukat, C.; Rodushkin, I. Trace and Major Elements in Food Supplements of Different Origin: Implications for Daily Intake Levels and Health Risks. Toxicol. Reports 2021, 8, 1067–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajewska, M.J. Analysis of the Content of Selected Heavy Metals in Dietary Supplements Available on the Polish Market. Farm. Pol. 2023, 79, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopra, A.S.; Lordan, R.; Horbańczuk, O.K.; Atanasov, A.G.; Chopra, I.; Horbańczuk, J.O.; Jóźwik, A.; Huang, L.; Pirgozliev, V.; Banach, M.; et al. The Current Use and Evolving Landscape of Nutraceuticals. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 175, 106001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rico, L.; Leyva-Perez, J.; Jara-Marini, M.E. Content and Daily Intake of Copper, Zinc, Lead, Cadmium, and Mercury from Dietary Supplements in Mexico. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2007, 45, 1599–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, M.; Ahmed, M.; Aftab, F.; Ali, M.A.; Sanaullah, M.; Ahmad, W.; Alshammari, A.H.; Khalid, K.; Wani, T.A.; Zargar, S. Contamination of Trace, Non-Essential/Heavy Metals in Nutraceuticals/Dietary Supplements: A Chemometric Modelling Approach and Evaluation of Human Health Risk upon Dietary Exposure. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2024, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jairoun, A.A.; Shahwan, M.; Zyoud, S.H. Heavy Metal Contamination of Dietary Supplements Products Available in the UAE Markets and the Associated Risk. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad, M.; Ahmed, M.; Ramzan, M.; Fatima, M.; Aftab, F.; Sanaullah, M.; Qamar, S.; Iftikhar, Z.; Wani, T.A.; Zargar, S. Appraisal of Potentially Toxic Metals Contamination in Protein Supplements for Muscle Growth: A Chemometric Approach and Associated Human Health Risks. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2024, 85, 127481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltrán, B.G.; Ramos-Sanchez, V.; Chávez-Flores, D.; Rodríguez-Maese, R.; Palacio, E. Total Reflection X-Ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (TXRF) Method Validation: Determination of Heavy Metals in Dietary Supplements. J. Chem. 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanković, V.; Tasić, T.; Leskovac, A.; Petrović, S.; Mitić, M.; Lazarević-Pašti, T.; Novković, M.; Potkonjak, N. Metals on the Menu—Analyzing the Presence, Importance, and Consequences. Foods 2024, 13, 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balali-Mood, M.; Naseri, K.; Tahergorabi, Z.; Khazdair, M.R.; Sadeghi, M. Toxic Mechanisms of Five Heavy Metals: Mercury, Lead, Chromium, Cadmium, and Arsenic. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 643972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korfali, S.I.; Hawi, T.; Mroueh, M. Evaluation of Heavy Metals Content in Dietary Supplements in Lebanon. Chem. Cent. J. 2013, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uranga Valencia, L.P.; Villarreal Ramírez, V.H.; Macías López, M.G.; Ortega Montes, F.; Terrazas Gómez, M.I. Estudio de Mercado Para Suplementos Alimenticios Orgánicos En Delicias, Chihuahua. Rev. Biológico Agropecu. Tuxpan 2021, 9, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, P.; Ruiz-Sánchez, E.; Ríos, C.; Ruiz-Chow, Á.; Reséndiz-Albor, A.A. A Health Risk Assessment of Lead and Other Metals in Pharmaceutical Herbal Products and Dietary Supplements Containing Ginkgo Biloba in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. Artic. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 8285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, P.; Ruiz-Sánchez, E.; Rojas, C.; García-Martínez, B.A.; López-Ramírez, A.M.; Osorio-Rico, L.; Ríos, C.; Reséndiz-Albor, A.A. Human Health Risk Assessment of Arsenic and Other Metals in Herbal Products Containing St. John’s Wort in the Metropolitan Area of Mexico City. Toxics 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustatea, G.; Ungureanu, E.L.; Iorga, S.C.; Ciotea, D.; Popa, M.E. Risk Assessment of Lead and Cadmium in Some Food Supplements Available on the Romanian Market. Foods 2021, 10, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Fan, X.; Zhou, J. Total Reflection X-Ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy. OALib 2020, 07, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Estévez, D.; Yánez-Jácome, G.S.; Simbaña-Farinango, K.; Navarrete, H. Distribution, Contents, and Health Risk Assessment of Cadmium, Lead, and Nickel in Bananas Produced in Ecuador. Foods 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, E.; Nesha, M.; Chowdhury, M.A.Z.; Rahman, S.H. Human Health Risk Assessment of Edible Body Parts of Chicken through Heavy Metals and Trace Elements Quantitative Analysis. PLoS One 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebeyehu, H.R.; Bayissa, L.D. Levels of Heavy Metals in Soil and Vegetables and Associated Health Risks in Mojo Area, Ethiopia. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0227883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USEPA Integrated Risk Information System | US EPA. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/iris (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- USP-NF Elemental Impurities—Limits and Elemental Impurities—Procedures | USP-NF. Available online: https://www.uspnf.com/official-text/accelerated-revision-process/accelerated-revision-history/elemental-impurities-limits-and-elemental (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Ćwieląg-Drabek, M.; Piekut, A.; Szymala, I.; Oleksiuk, K.; Razzaghi, M.; Osmala, W.; Jabłońska, K.; Dziubanek, G. Health Risks from Consumption of Medicinal Plant Dietary Supplements. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 3535–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchounwou, P.B.; Yedjou, C.G.; Patlolla, A.K.; Sutton, D.J. Heavy Metal Toxicity and the Environment. EXS 2012, 101, 133–164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Budi, H.S.; Catalan Opulencia, M.J.; Afra, A.; Abdelbasset, W.K.; Abdullaev, D.; Majdi, A.; Taherian, M.; Ekrami, H.A.; Mohammadi, M.J. Source, Toxicity and Carcinogenic Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals. Rev. Environ. Health 2024, 39, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandara, S.B.; Urban, A.; Liang, L.G.; Parker, J.; Fung, E.; Maier, A. Active Pharmaceutical Contaminants in Dietary Supplements: A Tier-Based Risk Assessment Approach. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 123, 104955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łozak, A.; Sołtyk, K.; Kiljan, M.; Fijałek, Z.; Ostapczuk, P. Determination of Selected Trace Elements in Dietary Supplements Containing Plant Materials. Polish J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2012, 62, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almela, C.; Algora, S.; Benito, V.; Clemente, M.J.; Devesa, V.; Súñer, M.A.; Vélez, D.; Montoro, R. Heavy Metal, Total Arsenic, and Inorganic Arsenic Contents of Algae Food Products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 918–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Wu, Q.; Gao, H.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Lek, S.; Xiao, J. Species-Specific Bioaccumulation and Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metal in Seaweeds in Tropic Coasts of South China Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 832, 155031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, O.; Kawamoto, M.S.; LeBlanc, K.L.; Grinberg, P.; Nogueira, A.R.de A.; Mester, Z. Determination of Chromium Picolinate and Trace Hexavalent Chromium in Multivitamins and Supplements by HPLC-ICP-QQQ-MS. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2020, 87, 103421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillitteri, J.L.; Shiffman, S.; Rohay, J.M.; Harkins, A.M.; Burton, S.L.; Wadden, T.A. Use of Dietary Supplements for Weight Loss in the United States: Results of a National Survey. Obesity 2008, 16, 790–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DesMarias, T.L.; Costa, M. Mechanisms of Chromium-Induced Toxicity. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2019, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.; Roberts, S.M.; Saab, I.N. Review of Regulatory Reference Values and Background Levels for Heavy Metals in the Human Diet. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Ahmad, M.; Khan, M.A.; Sohail, A.; Sanaullah, M.; Ahmad, W.; Iqbal, D.N.; Khalid, K.; Wani, T.A.; Zargar, S. Assessment of Carcinogenic and Non-Carcinogenic Risk of Exposure to Potentially Toxic Elements in Tea Infusions: Determination by ICP-OES and Multivariate Statistical Data Analysis. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2024, 84, 127454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, M.L.; Watkins, B.A.; Li, Y.; Anderson, R.A.; Campbell, W.W. Chromium Picolinate and Conjugated Linoleic Acid Do Not Synergistically Influence Diet- and Exercise-Induced Changes in Body Composition and Health Indexes in Overweight Women. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2008, 19, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine, J.M.R.; Fung, L.A.H.; Grant, C.N. Assessment of the Potential Health Risks Associated with the Aluminium, Arsenic, Cadmium and Lead Content in Selected Fruits and Vegetables Grown in Jamaica. Toxicol. Reports 2017, 4, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metal | RfD (mg.kg ̶ 1.day ̶ 1) | CSF (mg.kg ̶ 1.day ̶ 1) ̶ 1 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pb | 0.0035 | 0.0085 | [5,15,18] |

| As | 3 x 10-4 | 1.5 | [19] |

| Cr | 0.003 | 0.5 | [5,18,19] |

| Sample ID | *Dosage per day | Serving weight (Kg) |

IR (Kg/Day) | Therapeutic indication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 2 | 0.001 | 0.002 | Booster energy |

| V2 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.001 | Weight loss |

| M3 | 3 | 0.0005 | 0.002 | Weight loss |

| V4 | 1 | 0.002 | 0.002 | Improve digestion |

| M5 | 2 | 0.0005 | 0.001 | Booster energy |

| C6 | 2 | 0.0008 | 0.002 | Weight loss |

| V7 | 3 | 0.001 | 0.004 | Improve digestion |

| V8 | 3 | 0.001 | 0.003 | Weight loss |

| V9 | 3 | 0.001 | 0.003 | Improve digestion |

| V10 | 3 | 0.0005 | 0.002 | Improve glucose level |

| A11 | 6 | 0.0004 | 0.002 | Blood detoxifier |

| A12 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.03 | Muscle development |

| V13 | 6 | 0.0005 | 0.003 | Improve the immune system |

| V14 | 6 | 0.0005 | 0.003 | Weight loss |

| V15 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.033 | Improve the immune system |

| V16 | 4 | 0.0005 | 0.002 | Weight loss |

| V17 | 2 | 0.0005 | 0.001 | Weight loss |

| V18 | 2 | 0.0005 | 0.001 | Antioxidant |

| V19 | 6 | 0.001 | 0.006 | Weight loss |

| V20 | 3 | 0.001 | 0.004 | Improve digestion |

| A21 | 2 | 0.015 | 0.030 | Improve the immune system |

| V22 | 1 | 0.025 | 0.025 | Improve the immune system |

| S24 | 1 | 0.040 | 0.040 | Relaxing of the blood vessels |

| V25 | 1 | 0.002 | 0.002 | Improve digestion |

| V26 | 2 | 0.0005 | 0.001 | Antioxidant |

| S27 | 2 | 0.0005 | 0.001 | Regulation of the sleep cycle |

| S28 | 1 | 0.0006 | 0.0006 | Booster energy |

| S29 | 1 | 0.005 | 0.005 | Increased muscle mass |

| S30 | 1 | 0.005 | 0.005 | Increased muscle mass |

| S31 | 1 | 0.005 | 0.005 | Increased muscle mass |

| V32 | 6 | 0.001 | 0.006 | Weight loss |

| V33 | 3 | 0.0005 | 0.002 | Improve glucose level |

| V34 | 2 | 0.0005 | 0.001 | Antioxidant |

| C35 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.001 | Weight loss |

| A36 | 6 | 0.0004 | 0.002 | blood detoxifier |

| V37 | 3 | 0.001 | 0.003 | Weight loss |

| V38 | 6 | 0.0005 | 0.003 | Weight loss |

| V39 | 3 | 0.001 | 0.004 | Improve digestion |

| C40 | 1 | 0.0005 | 0.0005 | Booster energy |

| V41 | 6 | 0.0005 | 0.003 | Improve the immune system |

| A42 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.030 | Improve muscle development |

| V43 | 3 | 0.001 | 0.003 | Improve digestion |

| V44 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.001 | Weight loss |

| A45 | 3 | 0.003 | 0.009 | Muscle activity and cell growth |

| A46 | 3 | 0.003 | 0.009 | Muscle activity and cell growth |

| A47 | 3 | 0.003 | 0.009 | Muscle activity and cell growth |

| aSample ID | Standard adition (µg/L) | bMetal concentration (µg/L) | % Recovery | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb | Cr | As | Pb | Cr | As | ||

| V9 | 0 | 4.03 ± 0.17 | 28.94 ± 0.17 | 0.40 ± 0.09 | 86 | 104 | 96 |

| 25 | 25.52 ± 1.28 | 55.5 ± 0.4 | 25.02 ± 0.52 | ||||

| V10 | 0 | 2.16 ± 0.07 | 0.397 ± 0.001 | ˂LOD | 95 | 96 | 91 |

| 25 | 25.94 ± 0.56 | 24.51 ± 0.15 | 22.65 ± 0.37 | ||||

| A11 | 0 | 3.83 ± 0.23 | 73.07 ± 0.29 | 0.70 ± 0.13 | 86 | 96 | 98 |

| 25 | 25.29 ± 0.22 | 97.13 ± 0.44 | 25.21 ± 0.34 | ||||

| A12 | 0 | 1.77 ± 0.03 | 0.3894 ± 0.0002 | 0.47 ±0.04 | 92 | 95 | 103 |

| 25 | 24.77 ± 0.32 | 24.10 ± 0.13 | 26.23 ± 0.36 | ||||

| V14 | 0 | 3.82 ± 0.12 | 0.414 ± 0.001 | 2.26 ± .06 | 94 | 102 | 97 |

| 25 | 27.29 ± 0.84 | 26.04 ± 0.24 | 26.49 ± 0.64 | ||||

| V15 | 0 | 2.43 ± 0.09 | 0.72 ± 0.01 | ˂LOD | 97 | 101 | 104 |

| 25 | 26.57 ± 0.87 | 25.95 ± 0.14 | 26.03 ± 0.18 | ||||

| V16 | 0 | 3.34 ± 0.02 | 151.66 ± 0.09 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 96 | 96 | 99 |

| 25 | 27.29 ± 0.24 | 175.61 ± 0.79 | 24.76 ± 0.61 | ||||

| S27 | 0 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 1.85 ± 0.04 | 0.21 ± .04 | 96 | 89 | 100 |

| 25 | 24.26 ± 0.96 | 24.09 ± 0.40 | 25.29 ± 0.11 | ||||

| M1 | 0 | 5.6 ± 0.7 | 163.01 ± 0.39 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 83 | 107 | 106 |

| 25 | 26.4 ± 0.2 | 189.7 ± 0.8 | 26.75 ± 0.36 | ||||

| C6 | 0 | 2.65 ± 0.07 | 12.88 ± 0.42 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 94 | 93 | 104 |

| 25 | 26.15 ± 0.18 | 36.2 ± 0.2 | 26.1 ± 0.3 | ||||

| Sample ID | Pb (mg/Kg) | Cr (mg/Kg) | As (mg/Kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 4.51 ± 0.66 | 131.46 ± 0.39 | 0.21 ± 0.02 |

| V2 | 1.63 ± 0.02 | 12.97 ± 0.06 | 0.31 ± 0.04 |

| M3 | 1.08 ± 0.17 | 15.97 ± 0.46 | 0.46 ± 0.06 |

| V4 | 1.52 ± 0.07 | 11.19 ± 0.32 | 0.26 ± 0.02 |

| M5 | 1.64 ± 0.14 | 2.15 ± 0.01 | 1.34 ± 038 |

| C6 | 1.75 ± 0.06 | 8.47 ± 0.42 | 0.06 ± 0.09 |

| V7 | 0.82 ± 0.04 | 2.67 ± 0.06 | 0.12 ± 0.05 |

| V9 | 4.20 ± 0.16 | 30.14 ± 0.17 | 0.42 |

| V10 | 2.16 ± 0.06 | 0.1588 ± 0.0005 | ˂ LOD |

| A11 | 9.03 ± 0.22 | 34.68 ± 0.44 | 11.41 ± 0.65 |

| A12 | 1.58 ± 0.03 | 0.3476 ± 0.0001 | 0.424 ± 0.039 |

| V13 | 2.55 ± 0.06 | 6.31 ± 0.15 | 39.93 ± 0.32 |

| V14 | 2.51 ± 0.11 | 0.272 ± 0.001 | 1.49 ± 0.05 |

| V15 | 2.25 ± 0.09 | ˂ LOD | 0.66 ± 0.04 |

| V16 | 2.98 ± 0.03 | 135.41 ± 0.10 | 0.07 ± 0.03 |

| V17 | 1.98 ± 0.05 | 8.00 ± 0.33 | 5.91 ± 0.96 |

| V18 | 8.17 ± 0.05 | 29.81 ± 0.34 | 1.47 ± 0.03 |

| V19 | 2.59 ± 0.02 | 150.01 ± 0.03 | ˂ LOD |

| V20 | 2.64 ± 1.05 | 65.96 ± 0.33 | 0.12 ± 0.09 |

| A21 | 0.59 ± 0.07 | 1.15 ± 0.08 | ˂ LOD |

| V22 | 0.39 ± 0.04 | 0.32083 ± 0.00008 | ˂ LOD |

| S24 | 0.40 ± 0.02 | 2.49 ± 0.03 | ˂ LOD |

| V25 | 0.94 ± 0.07 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | ˂ LOD |

| V26 | 0.73 ± 0.4 | 22.52 ± 0.28 | 1.08 ± 0.02 |

| S27 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 2.00 ± 0.04 | 0.23 ± 0.01 |

| S28 | 1.485 ± 0.002 | 0.420 ± 0.004 | ˂ LOD |

| S29 | 1.749 ± 0.009 | 0.687 ± 0.013 | ˂ LOD |

| S30 | 1.7857 ± 0.0005 | 0.632 ± 0.006 | ˂ LOD |

| S31 | 1.812 ± 0.001 | 0.466 ± 0.002 | ˂ LOD |

| V32 | 0.54 ± 0.10 | 233.20 ± 1.45 | 0.24 ± 0.06 |

| V33 | 0.49 ± 0.17 | ˂ LOD | 0.05 ± 0.02 |

| V34 | 0.47 ± 0.1 | 25.84 ± 0.71 | 0.93 ± 0.05 |

| C35 | 0.24 ± 0.14 | 14.52 ± 0.56 | 0.18 ± 0.02 |

| A36 | 0.41 ± 0.11 | 39.56 ± 0.45 | 0.25 ± 0.05 |

| V37 | 0.58 ± 0.12 | ˂ LOD | ˂ LOD |

| V38 | 0.53 ± 0.03 | 3.09 ± 0.18 | 0.28 ± 0.11 |

| V39 | ˂ LOD | 15.15 ± 0.23 | ˂ LOD |

| C40 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 1.55 ± 0.25 |

| V41 | ˂ LOD | 6.95 ± 0.09 | 37.11 |

| A42 | 0.39 ± 0.09 | ˂ LOD | ˂ LOD |

| V43 | 1.39 ± 0.20 | 24.16 ± 0.32 | 0.026 ± 0.008 |

| V44 | 0.86 ± 0.07 | 127.97 ± 0.48 | 0.31 ± 0.1 |

| A45 | 7.20 ±0.61 | 15.36 ± 0.15 | 0.47 ± 0.17 |

| A46 | 4.11 ± 0.17 | 18.21 ± 0.33 | ˂ LOD |

| A47 | 6.32 ± 0.17 | 8.71 ± 0.30 | ˂ LOD |

| Minimum | 0.0700 ± 0.0005 | 0.07800 ± 0.00008 | 0.0260 ± 0.0004 |

| Maximum | 9.03 ± 1.05 | 233.20 ± 1.45 | 39.93 ± 0.96 |

| Mean | 1.99 ± 0.13 | 26.88 ± 0.23 | 2.39 ± 0.11 |

| Sample ID |

EDI (mg/Kg bw/Day) | THQ | HI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb | Cr | As | Pb | Cr | As | ||

| A11 | 3.10E-04 | 1.19E-03 | 3.91E-04 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.93 | 1.27 |

| A12 | 6.77E-04 | 1.49E-04 | 1.82E-04 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.43 | 0.60 |

| A21 | 2.53E-04 | 4.93E-04 | NA | 0.05 | 0.12 | NA | 0.17 |

| A36 | 1.41E-05 | 1.36E-03 | 8.57E-06 | 0.003 | 0.32 | 0.02 | 0.35 |

| A42 | 1.67E-04 | NA | NA | 0.03 | NA | NA | 0.03 |

| A45 | 9.25E-04 | 1.97E-03 | 6.002E-05 | 0.19 | 0.47 | 0.14 | 0.80 |

| A46 | 5.28E-04 | 2.34E-03 | NA | 0.11 | 0.56 | NA | 0.66 |

| A47 | 8.13E-04 | 1.12E-03 | NA | 0.17 | 0.27 | NA | 0.43 |

| C35 | 3.43E-06 | 2.07E-04 | 2.57E-06 | 0.001 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| C40 | 5.00E-07 | 5.57E-07 | 1.11E-05 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| C6 | 4.13E-05 | 2.00E-04 | 1.3E-06 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.0003 | 0.06 |

| M1 | 1.29E-04 | 3.76E-03 | 6.00E-06 | 0.03 | 0.89 | 0.01 | 0.93 |

| M3 | 2.31E-05 | 3.42E-04 | 9.86E-06 | 0.005 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.11 |

| M5 | 2.34E-05 | 3.071E-05 | 1.91E-05 | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| S24 | 2.30E-04 | 1.42E-03 | NA | 0.05 | 0.34 | NA | 0.38 |

| S27 | 4.10E-06 | 2.86E-05 | 3.29E-06 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| S28 | 1.32E-05 | 3.75E-06 | NA | 0.003 | 0.001 | NA | 0.004 |

| S29 | 1.25E-04 | 4.91E-05 | NA | 0.03 | 0.01 | NA | 0.04 |

| S30 | 1.27E-04 | 4.51E-05 | NA | 0.03 | 0.01 | NA | 0.04 |

| S31 | 1.29E-04 | 3.33E-05 | NA | 0.03 | 0.01 | NA | 0.03 |

| V10 | 4.63E-05 | 3.40E-06 | NA | 0.01 | 0.0008 | NA | 0.01 |

| V13 | 1.09E-04 | 2.70E-04 | 1.71E-03 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 4.06 | 4.15 |

| V14 | 1.08E-04 | 1.17E-05 | 6.39E-05 | 0.02 | 0.003 | 0.15 | 0.18 |

| V15 | 1.06E-03 | NA | 3.11E-04 | 0.22 | NA | 0.74 | 0.95 |

| V16 | 8.51E-05 | 3.87E-03 | 2.00E-06 | 0.02 | 0.92 | 0.005 | 0.94 |

| V17 | 2.83E-05 | 1.14E-04 | 8.44E-05 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0.23 |

| V18 | 1.17E-04 | 4.26E-04 | 2.10E-05 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.17 |

| V19 | 2.23E-04 | 1.29E-02 | NA | 0.05 | 3.05 | NA | 3.10 |

| V2 | 2.79E-05 | 2.22E-04 | 5.31E-06 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.07 |

| V20 | 1.36E-04 | 3.39E-03 | 6.17E-06 | 0.03 | 0.81 | 0.01 | 0.85 |

| V22 | 1.39E-04 | 1.15E-04 | NA | 0.03 | 0.03 | NA | 0.06 |

| V23 | 2.20E-03 | 1.73 | 3.27 | 0.45 | 410.75 | 777.45 | 1188.64 |

| V25 | 2.01E-05 | 3.43E-06 | NA | 0.004 | 0.001 | NA | 0.005 |

| V26 | 1.04E-05 | 3.22E-04 | 1.54E-05 | 0.002 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.12 |

| V32 | 4.63E-05 | 2.00E-02 | 2.06E-05 | 0.01 | 4.75 | 0.05 | 4.80 |

| V33 | 1.05E-05 | NA | 1.07E-06 | 0.002 | NA | 0.003 | 0.005 |

| V34 | 6.71E-06 | 3.69E-04 | 1.33E-05 | 0.001 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| V37 | 2.49E-05 | NA | NA | 0.01 | NA | NA | 0.01 |

| V38 | 2.27E-05 | 1.32E-04 | 1.20E-05 | 0.005 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| V39 | NA | 7.79E-04 | NA | NA | 0.19 | NA | 0.19 |

| V4 | 3.26E-05 | 2.40E-04 | 5.57E-06 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.08 |

| V41 | NA | 2.98E-04 | 1.59E-03 | NA | 0.07 | 3.78 | 3.85 |

| V43 | 6.55E-05 | 1.14E-03 | 1.23E-06 | 0.01 | 0.27 | 0.003 | 0.29 |

| V44 | 1.47E-05 | 2.19E-03 | 5.31E-06 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.01 | 0.54 |

| V7 | 4.22E-05 | 1.37E-04 | 6.1E-06 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| V8 | 1.42E-02 | 5.41E-02 | NA | 2.90 | 12.85 | NA | 15.75 |

| V9 | 1.98E-04 | 1.42E-03 | 1.98E-05 | 0.04 | 0.34 | 0.05 | 0.42 |

| EDI_Pb | EDI_Cr | EDI_As | HI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDI_Pb | Pearson correlation | 1 | 0.015 | 0.029 | 0.077 |

| Sig. (two-sided) | 0.924 | 0.848 | 0.613 | ||

| N | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | |

| EDI_Cr | Pearson correlation | 0.015 | 1 | -0.081 | 0.682** |

| Sig. (two-sided) | 0.924 | 0.598 | <0.0001 | ||

| N | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | |

| EDI_As | Pearson correlation | 0.029 | -0.081 | 1 | 0.672** |

| Sig. (two-sided) | 0.848 | 0.598 | <0.0001 | ||

| N | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | |

| HI | Pearson correlation | 0.077 | 0.682** | 0.672** | 1 |

| Sig. (two-sided) | 0.613 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| N | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).