Submitted:

21 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

- Through the systematic classification of various features in building floor plans, this paper offers a comprehensive framework to assist researchers and practitioners in understanding and applying these features more effectively. This classification not only aids theoretical research but also offers guidance for practical implementations.

- Through a detailed analysis of the four features, this paper presents innovative tools and methodologies for architectural designers and planners in selecting and optimizing schemes, illustrating how these tools collaboratively operate to extract and analyze building floor plan features. This advancement contributes to enhancing design efficiency and effectiveness.

1. Floor Plan Retrieval Overview

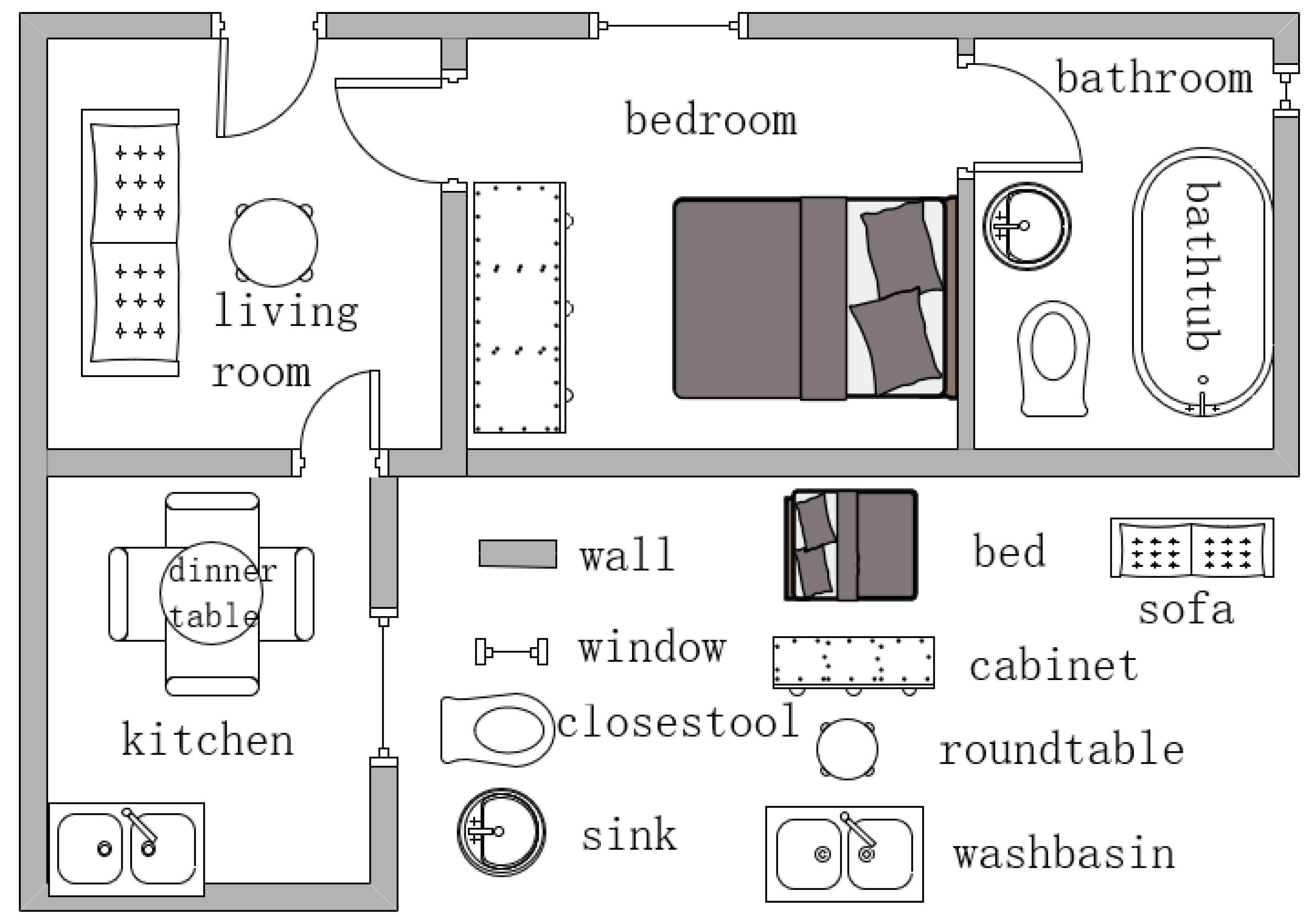

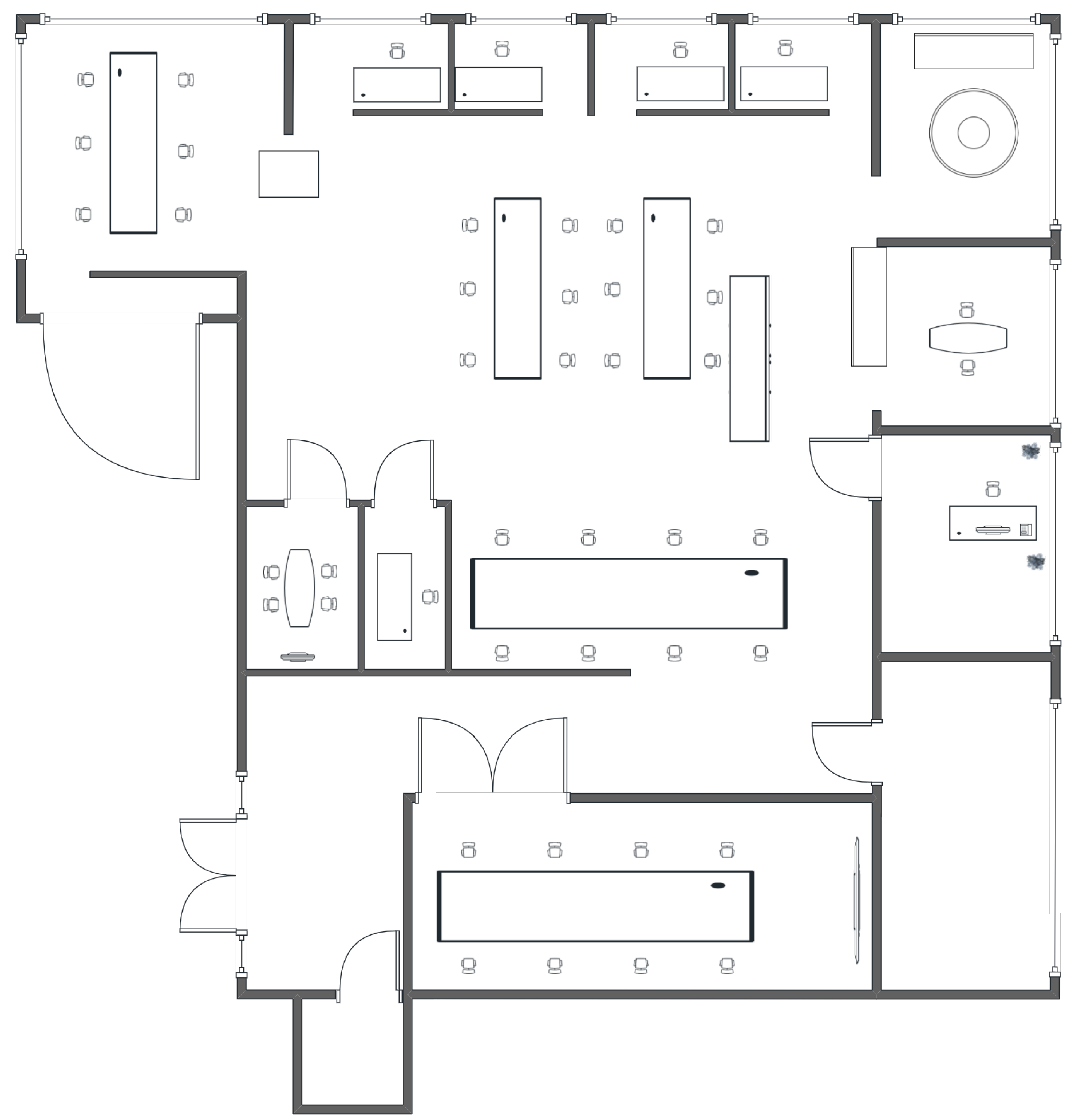

1.1. Overview of Floor Plan Feature Extraction

1.2. Overview of Floor Plan Retrieval Architecture

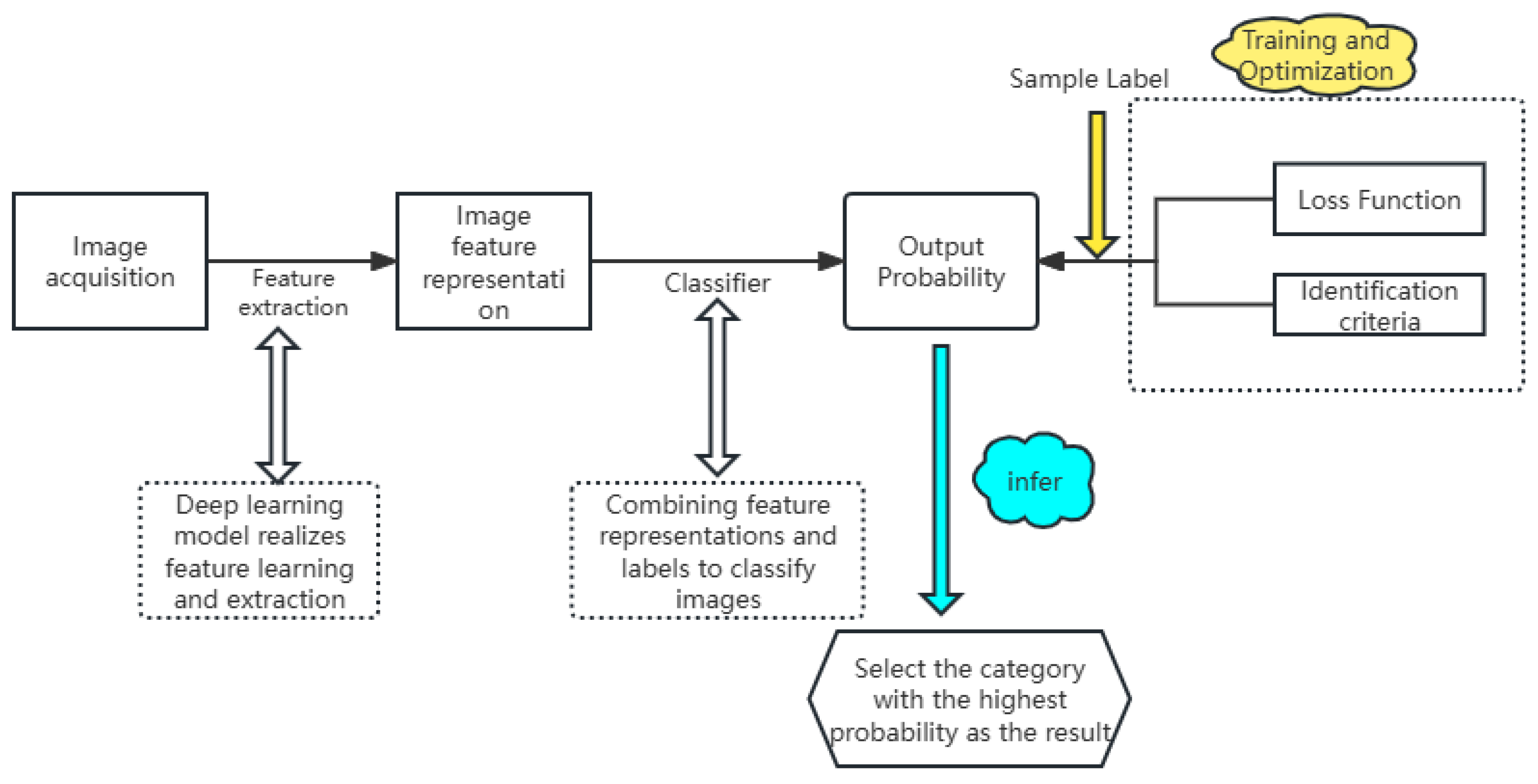

1.2.1. Network Feedforward Solutions

1.2.2. Feature Extraction of Floor Plans Structural Elements

1.2.3. Similarity Measure

2. Semantic Feature Retrieval

2.1. Semantic Feature Analysis

2.2. Rule Feature Extraction Retrieval

3. Texture Feature Retrieval

3.1. Gabor Wavelet Transform

3.2. Texture Spectrum

| V1 | V2 | V3 |

|---|---|---|

| *V4 V6 | *V0 V7 | *V5 V8 |

4. Spatial Feature Retrieval

4.1. Topological and Geometric Feature

4.1.1. Topological Feature Retrieval

4.1.2. Geometric Feature Retrieval

4.2. Multi-Dimensional and Shape Feature Retrieval

4.2.1. Multi-Dimensional Feature Retrieval

- High-dimensionality: Typically, the dimension of the image feature vector is on the order of .

- Non-Euclidean similarity measurement: The Euclidean distance metric often fails to adequately represent all human perceptions of visual content; consequently, alternative similarity measurement methods, such as histogram intersection, cosine similarity, and correlation, must be employed.

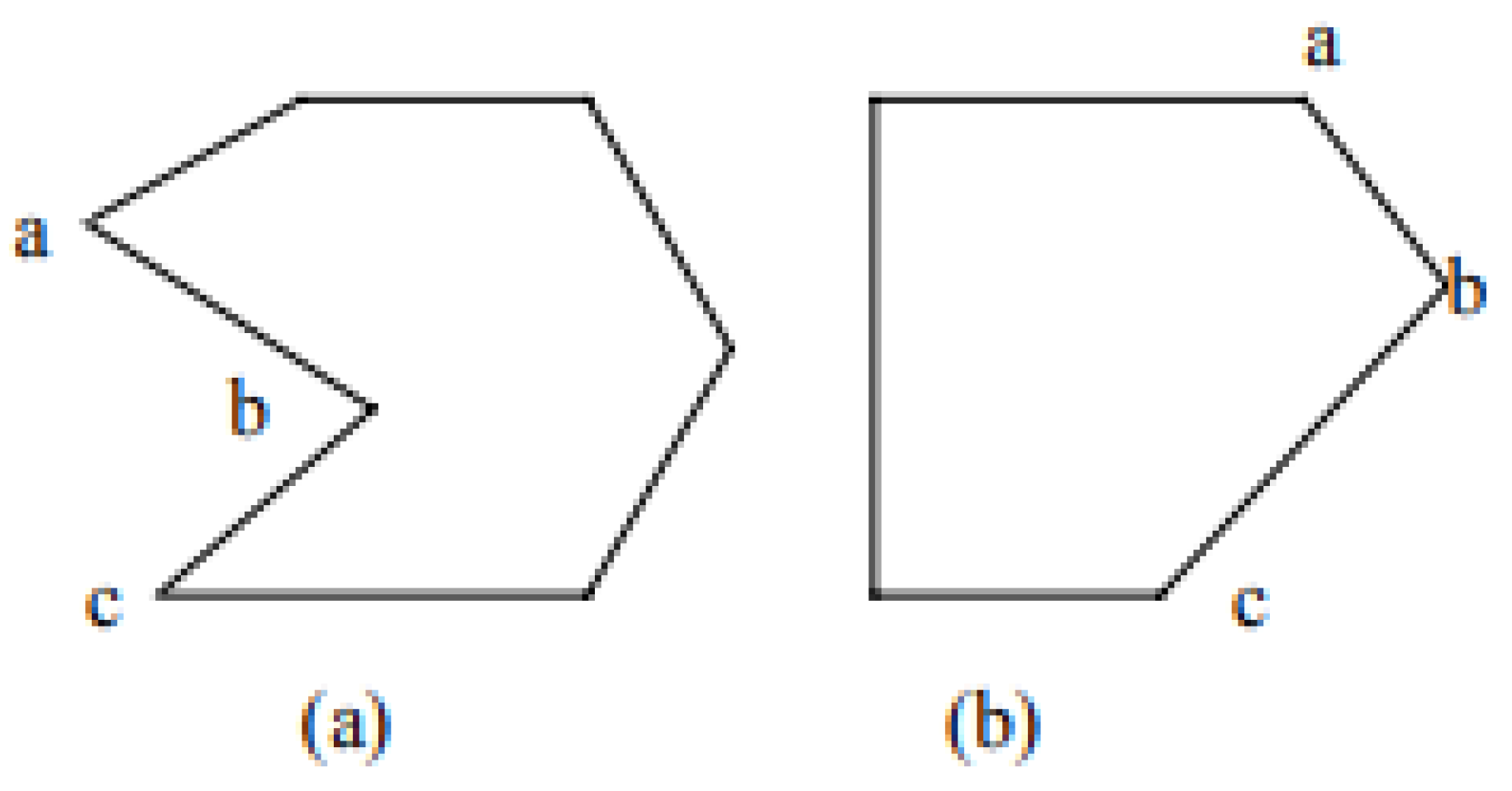

4.2.2. Fourier Shape Descriptor

4.2.3. Shape-Independent Moments

4.2.4. Shape Features Based on Inner Angles

5. Experimental and Performance Comparison of Various Algorithms

5.1. Datasets

5.2. Evaluation

5.3. Various Algorithms Performance Comparison

6. Conclusion

-

Diverse graphic retrieval and cross-application including images, text, audio, video, etc.Future architectural design tools are likely to prioritize user experience by integrating multiple data sources for federated searches, thus providing richer and more accurate results. Enhancing the design process through personalized requirements and collaborative design will create a more enjoyable and efficient experience. Future research may delve into multimodal data representation, processing, and retrieval, combining floor plans with other modalities (such as text, 3D models, and satellite images) to gain a comprehensive understanding of architectural design. Moreover, in smart city planning, architectural design, and virtual reality (VR), multidimensional feature retrieval of floor plans will play an increasingly important role in achieving more accurate design, simulation, and optimization. In the study of cultural heritage protection and digitalization, multidimensional feature retrieval can facilitate the comparison, classification, and restoration of floor plan data for historical buildings and cultural relics.

-

Efficient feature extraction and indexing as well as personalized and adaptive retrieval.As the volume of data continues to increase, efficiently indexing and retrieving multidimensional features becomes essential. Future research may focus on designing more efficient and lightweight deep learning models, enabling real-time multidimensional feature extraction on mobile devices and embedded systems. By analyzing user interaction data, future floor plan retrieval systems will be able to adaptively adjust feature weights and optimization strategies to achieve personalized retrieval results. With minimal user feedback, the retrieval model can be continuously improved, thereby enhancing the overall performance of the system.

-

Interpretability of multi-dimensional data and data privacy security.As the complexity of deep learning models increases, interpretability becomes crucial. Future research may focus on developing models that can explain the relationship between multidimensional features and retrieval results, enabling users to understand the decision-making process of the retrieval system. Additionally, as data privacy concerns grow, ensuring efficient floor plan retrieval while protecting user privacy will be essential. Technologies such as differential privacy and federated learning should be integrated into the retrieval system. Furthermore, safeguarding sensitive architectural and design data from unauthorized access will emerge as an important research direction, particularly in floor plan retrieval for military and government building designs.

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kemble Stokes, H. : An examination of the productivity decline in the construction industry[J]. Rev. Econ. Stat. 63(4), 495 (1981).

- Zhengda, L. , Wang, T., Guo, J., Meng, W., Xiao, J., Zhang, W., Zhang, X.: Data-driven floor plan understanding in rural residential buildings via deep recognition. Inf. Sci. 567, 58–74 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Pizarro, P.N. , Hitschfeld, N., Sipiran, I., Saavedra, J.M.: Automatic floor plan analysis and recognition[J]. Autom. Constr. 140, 104348 (2022).

- Shelhamer, E. , Long J., Darrell T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation[J], In IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, pp. 640–651 (2017).

- Ronneberger, O. Fischer, P., Brox, T.: U-net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation[C]. In: Navab, N., Hornegger, J., Wells, W.M., Frangi, A.F. (eds.) Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, October 5-9, 2015, Proceedings, Part III, pp. 234–241. Springer International Publishing, Cham (2015).

- Chen, L.-C. Zhu, Y., Papandreou, G., Schroff, F., Adam, H.:Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation[C]. In: Ferrari, V., Hebert, M., Sminchisescu, C.,Weiss, Y. (eds.) Computer Vision – ECCV 2018: 15th European Conference, Munich, Germany, September 8–14, 2018, Proceedings, Part VII, pp. 833–851. Springer International Publishing,Cham (2018).

- ALEIXO C B, MARIUSZ T, ANNA H, et al. Automatic reconstruction of semantic 3d models from 2d floor plans[C].2023 18th International Conference on Machine Vision and Applications2023:1-5.

- PARK S, HYEONCHEOL K. 3DPlanNet: generating 3d models from 2d floor plan images using ensemble methods[J]. Electronics, 2021: 2729.

- ZHU J, ZHANG H, WEN Y M. A new reconstruction method for 3D buildings from 2D vector floor plan[J]. Computer-aided Design and Applications, 2014,11(6): 704-714.

- WANG L Y, GUNHO S. An integrated framework for reconstructing full 3d building models[J]. Advances in 3D Geo-Information Sciences, 2011: 261-274.

- CHEN L,WU J Y,YASUTAKA F. Floornet: a unified framework for floorplan reconstruction from 3d scans[C].Proceedings of the Europeanconference on computer vision,2018: 201-217.

- TARO N, TOSHIHIKO Y. A preliminary study on attractiveness analysis of real estate floor plans[C].2019 IEEE 8th Global Conference on Consumer Electronics,2019: 445-446.

- KIRILL S, NICOLAS P. Integratingfloor plans into hedonic models for rent price appraisal[J].Research Papers in Economics,2021.

- GEORG G, LUKAS F,KAUFMAN H,et al. Extraction of structural and semantic data from 2D floor plans for interactive andimmersive VR real estate exploration[J]. Technologies, 2018, 6(4):101.

- DIVYA S, NITIN G, CHATTOPADHYAY C,et al. DANIEL: a deep architecture for automatic analysis and retrieval of building floor plans[C].2017 14th IAPR International Conference on Document Analysisand Recognition, 2017.

- DIVYA S, NITIN G, CHATTOPADHYAY C,et al. A novel feature transform framework using deep neural network for multimodal floor plan retrieval[J]. International Journal on Document Analysis and Recognition, 2019, 22(4): 417-429.

- YAMASAKI T,ZHANG J, YUKI T,et al. Apartment structure estimation using fully convolutional networks and graph model[C].Proceedings of the 2018 ACM Workshop on Multimedia for Real Estate Tech,2018: 1-6.

- KIM H, SEONGYONG K, KIYUN Y. Automatic extraction of indoor spatial information fromfloor plan image: a patch-based deep learning methodology application on large-scale complex buildings[J].ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 2021, 10(12): 828.

- MA K Y,CHENG Y,GE W,et al.Method of automatic recognition of functional parts in architecturallayout plan using Faster R-CNN [J].Journal of Surveying and Planning Science and Technology,2019,36(03):311-317.

- SHEHZADI T, KHURRAM A H, ALAIN P,et al. Mask-Aware semi-supervised object detection in floor plans[J]. Applied Sciences, 2022, 12(19):9398.

- WANG T, MENG W L,ZHENG D L,et al.RC-Net: row and column network with text feature for parsing floor plan images[J]. Journal of Computer Science And Technology, 2023, 38(3): 526–539.

- FAN Z W, ZHU L J,Li H H,et al. Floorplancad: alarge-scale cad drawing dataset for panoptic symbol spotting[C].Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2021: 10128-10137.

- CHRISTOFFER P, FREDERIK M, MARK P P, et al. Generalizing floor plans using graph neural networks[C].2021 IEEEInternational Conference on Image Processing, 2021: 654-658.

- ZENG Z L, Li X Z, Yu Y K,et al. Deep floor plan recognition using a multi-task network withroom-boundary-guided attention[C].Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2019: 9096-9104.

- LV X L, ZHAO S C, YU X Y,et al. Residential floor plan recognition and reconstruction[C].Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2021: 16717-16726.

- GAO M,ZHANG H H,ZHANG T R, et al. Deep learning based pixel-level public architectural floor plan space recognition[J]. Journal of Graphics, 2022, 43(2): 189.

- YANG L P, MICHAEL W. Generation of navigation graphs for indoor space[J/OL]. International Journal of Geographical Information Science[J], 2015: 1737-1756.

- SARDEY M P, GAJANAN K. A Comparative Analysis of Retrieval Techniques in Content BasedImage Retrieval[C]. Computer Science and amp; Information Technology, 2015.

- LIU C, WU J J,PUSHMEET K,et al. Raster-to-Vector: revisiting floorplan transformation[C].2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer, 2017:2214-2222.

- AOKI Y, SHIO A, ARAI H, et al. A prototype system for interpreting hand-sketched floor plans[C].Proceedings of 13th International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Vienna, 1996:747-751.

- SHERAZ A, MARCUS L, MARKUS W,et al. Improved automatic analysis of architecturalfloor plans[C].2011 International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition,2011:864-869.

- RAOUL W, INA B, KLEIN R,et al.The room connectivity graph: shape retrieval in the architectural domain[J]. 2008.

- LLUÍS-P D L H, DAVID F, ALICIA F, et al. Runlength histogram image signature for perceptual retrieval of architectural floor plans[M].IAPR International Workshop on Graphics Recognition,2013.

- LLUÍS-PERE D L H, SHERAZ A, MARCUS L, et al. Statistical segmentation and structural recognition for floor plan interpretation[J]. International Journal on Document Analysis and Recognition, 2014: 221-237.

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-rural Developmentof the People’s Republic of China.GB 50352-2005. General principles for civil engineering design[S]. Beijing:China Publishing Group,2005:101-108.

- YANG, L. Research and implementation of building image retrieval based on deep learning[D].Xi’an:Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology,2022.

- ZHANG H X, LI Y S, SONG C.Block vectorization of interior layout plans and high-efficiency 3D building modeling [J]. Computer Science and Exploration,2013,7(1):63-73.

- MARKUS W, MARCUS L, ANDREAS D. A.SCAtch - a sketch-based retrieval for architectural floor plans[C].In 2010 12th International Conferenceon Frontiers in Handwriting Recognition,2010:289-294.

- IORDANIS E, MICHALIS S, GEORGIOS P. PU learning-based recognition of structural elements in architectural floor plans[J]. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 2021, 80(9): 13235-13252.

- Haralick R M, Shanmugam K, Dinstein I H. Textural features for image classification[J]. IEEE Transactions on systems, man, and cybernetics, 1973 (6): 610-621.

- Manjunath B S, Ma W Y. Texture features for browsing and retrieval of image data[J]. IEEE Transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, 1996, 18(8): 837-842.

- Daugman J, G. Uncertainty relation for resolution in space, spatial frequency, and orientation optimized by two-dimensional visual cortical filters[J]. JOSA A, 1985, 2(7): 1160-1169.

- He D C, Wang L. Texture features based on texture spectrum[J]. Pattern recognition, 1991, 24(5): 391-399.

- CLAUDIO M, RENATO P, MURA,et al.Walk2Map: extracting floor plans from indoor walk trajectories[J]. Computer Graphics Forum, 2021: 375-388.

- YUKI T, NAOTO I, TOSHIHIKO Y, et al. Similar floor plan retrieval featuring multi-task learning of layout type classification and room presence prediction[C].2018 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics,2018: 1-6.

- KAREN S, ANDREW Z. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition[C].International Conference on Learning Representations, 2015.

- Wang T, Meng W L, Lu Z D, et al. RC-Net: Row and Column Network with Text Feature for Parsing Floor Plan Images[J]. Journal of Computer Science and Technology, 2023, 38(3): 526-539.

- CAO Y Q, JIANG T, THOMAS G. A maximum common substructure-based algorithm for searching and predicting drug-like compounds[J]. Bioinformatics, 2008, 24(13): i366-i374.

- DIVYA S, CHIRANJOY C, GAURAV H,et al. A unified framework for semantic matching of architectural floorplans[C].2016 23rd International Conference on Pattern Recognition,2016.

- DIVYA S, CHIRANJOY C. High-level feature aggregation for fine-grained architectural floor plan retrieval[J]. IET ComputerVision, 2018, 12(5): 702-709.

- LEE P K, BJORN S. Shape-Based floorplan retrieval using parse tree matching[C].2021 17th International Conference on Machine Vision and Applications, 2021: 1-5.

- RASIKA K, KRUPA J, CHIRANJOY C, et al. A rotation and scale invariant approach for multi-oriented floor plan image retrieval[J]. Pattern Recognition Letters, 2021: 1-7.

- Boston, M. A dynamic index structure for spatial searching[C]. Proceedings of the ACM-SIGMOD. 1984: 547-557.

- Greene, Diane. An implementation and performance analysis of spatial data access methods. Proceedings[C]. Fifth International Conference on Data Engineering. IEEE Computer Society, 1989.

- Sellis T, Roussopoulos N, Faloutsos C. The R+-tree: A dynamic index for multi-dimensional objects[J]. 1987.

- Beckmann N, Kriegel H P, Schneider R, et al. The R*-tree: An efficient and robust access method for points and rectangles[C].Proceedings of the 1990 ACM SIGMOD international conference on Management of data. 1990: 322-331.

- White D A, Jain R C. Similarity indexing: Algorithms and performance[C].Storage and Retrieval for Still Image and Video Databases IV. SPIE, 1996, 2670: 62-73.

- Ng R T, Sedighian A. Evaluating multidimensional indexing structures for images transformed by principal component analysis[C]. Storage and Retrieval for Still Image and Video Databases IV. SPIE, 1996, 2670: 50-61.

- Tagare H, D. Increasing retrieval efficiency by index tree adaptation[C].1997 Proceedings IEEE Workshop on Content-Based Access of Image and Video Libraries. IEEE, 1997: 28-35.

- Hu M, K. Visual pattern recognition by moment invariants[J]. IRE transactions on information theory, 1962, 8(2): 179-187.

- Yang L, Albregtsen F. Fast computation of invariant geometric moments: A new method giving correct results[C].Proceedings of 12th International Conference on Pattern Recognition. IEEE, 1994, 1: 201-204.

- Kapur D, Lakshman Y N, Saxena T. Computing invariants using elimination methods[C].Proceedings of International Symposium on Computer Vision-ISCV. IEEE, 1995: 97-102.

- Cooper D B, Lei Z. On representation and invariant recognition of complex objects based on patches and parts[C].International Workshop on Object Representation in Computer Vision. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1994: 139-153.

- Zhuang, Y. Intelligent Multimedia Information Analysis and Retrieval with Application to Visual Design[J]. Doctor Dissertation of Zhejiang University, 1998.

- Delalandre M, Valveny E, Pridmore T, et al. Generation of synthetic documents for performance evaluation of symbol recognition and spotting systems[J]. International Journal on Document Analysis and Recognition (IJDAR), 2010, 13(3): 187-207.

- LLUÍS-PERE DL H, ORIOL R T, SERGI R M,et al. CVC-FP and SGT: a new database for structural floor plan analysis and its groundtruthing tool[J]. International Journal on Document Analysis and Recognition,2015, 18: 15-30.

- MARÇAL R, AGNÉS B, JOSEP L. Relational indexing of vectorial primitives for symbol spotting in line-drawing images[J]. Pattern Recognition Letters, 2010, 31(3): 188-201.

- Sharma D, Gupta N, Chattopadhyay C, et al. Daniel: A deep architecture for automatic analysis and retrieval of building floor plans[C]. 2017 14th IAPR international conference on document analysis and recognition (ICDAR). IEEE, 2017, 1: 420-425.

- SHREYA G, VISHESH M, CHIRANJOY C, et al. BRIDGE: building plan repositoryfor image description generation, and evaluation[C].2019 International Conference on DocumentAnalysis and Recognition,2019:1071-1076.

- TAHIRA S, KHURRAM A H, ALAIN P,et al. Mask-Aware semi-supervised object detection in floor plans[J]. Applied Sciences, 2022, 12(19):9398.

- Kiyota, Y. Frontiers of computer vision technologies on real estate property photographs and floorplans[J]. Frontiers of Real Estate Science in Japan, 2021, 325.

- Dodge S, Xu J, Stenger B. Parsing floor plan images[C].2017 Fifteenth IAPR international conference on machine vision applications (MVA). IEEE, 2017: 358-361.

- Pizarro Riffo P, N. Wall polygon retrieval from architectural floor plan images using vectorización and Deep Learning methods[J]. 2023.

- Fan Z, Zhu L, Li H, et al. Floorplancad: A large-scale cad drawing dataset for panoptic symbol spotting[C]. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision. 2021: 10128-10137.

- Ebert F, Yang Y, Schmeckpeper K, et al. Bridge data: Boosting generalization of robotic skills with cross-domain datasets[J]. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2109.13396, 2021.

- Mishra S, Hashmi K A, Pagani A, et al. Towards robust object detection in floor plan images: A data augmentation approach[J]. Applied Sciences, 2021, 11(23): 11174.

- NAOKI K, TOSHIHIKO Y, KIYOHARU A, et al. Users’preference prediction of real estate propertiesbased on floor plan analysis[J]. IEICE Transactions on Information and Systems, 2020: 398-405.

- DIVYA S, NITIN G, CHIRANJOY C, et al. REXplore: a sketch based interactive explorer for real estates using building floor plan images[J]. 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Multimedia, 2018:61-64.

- ATHARVA K, RASIKA K, KRUPA J,et al. RISC-Net: rotation invariant siamese convolution network for floor plan image retrieval[J]. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 2022: 41199-41223.

- Fan Z, Zhu L, Li H, et al. Floorplancad: A large-scale cad drawing dataset for panoptic symbol spotting[C].Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision. 2021: 10128-10137.

- GAL C, URI S,VARUN S, et al. Anonline algorithm for large scale image similarity learning[J]. Neural Information Processing Systems,Neural Information Processing Systems,2009.

- DIVYA S, CHIRANJOY C,GAURAY H. Retrieval of architectural floor plans based on layout semantics[J].IEEE 2016 Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition,2016.

| Dataset name | Number of pictures | usage | public | year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SESYD [65] | 1000 | Retrieval,Symbol localization | yes | 2010 |

| LIFULL HOME’S Dataset [71] | 8300 ten thousand | Retrieval,Deep learning,Text mining | yes | 2015 |

| CVC-FP [72] | 122 | Semantic segmentation | yes | 2015 |

| FPLAN-POLY [73] | 42 | Symbolic positioning | yes | 2010 |

| ROBIN [68] | 510 | Retrieval,Symbol location | yes | 2017 |

| FloorPlanCAD [74] | 10094 | Panoramic Symbol Positioning | yes | 2021 |

| BRIDGE [75] | 13000 | Symbol Recognition Scene Map Composition Retrieval Building Plan Analysis |

yes | 2019 |

| SFPI [76] | 10000 | Symbol positioning Building plan analysis |

yes | 2022 |

| methodology | dataset | performance | year |

|---|---|---|---|

| RLH + Chechik et al. [81] | ROBIN | Map=0.10 | 2009 |

| RLH + Chechik et al. [81] | SESYD | Map=1.0 | 2009 |

| BOW + Chechik et al. [81] | ROBIN | Map=0.19 | 2009 |

| BOW + Chechik et al. [81] | SESYD | Map=1.0 | 2009 |

| HOG + Chechik et al. [81] | ROBIN | Map=0.31 | 2009 |

| DANIEL [15] | ROBIN | Map=0.56 | 2017 |

| Sharma et al. [49] | ROBIN | Map=0.25 | 2016 |

| CVPR [82] | ROBIN | Map=0.29 | 2016 |

| MCS [82] | HOME | - | 2018 |

| CNNs(update) [36] | HOME | Accuracy=0.49 | 2018 |

| Sharma and Chattopadhyay [50] | ROBIN | MAP=0.31 | 2018 |

| Sharma and Chattopadhyay [50] | SESYD | MAP=1.0 | 2018 |

| FCNs [17] | HOME | MAP=0.39 | 2018 |

| REXplore [78] | ROBIN | MAP=0.63 | 2018 |

| Rasika et al. [52] | ROBIN | MAP=0.74 | 2021 |

| RISC-Net [79] | ROBIN | MAP=0.79 | 2022 |

| GCNs | ROBIN | MAP=0.85 | – |

| 6]*Class | Semantic Symbol Spotting | Instance Symbol Spotting | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| weighted Fl | mAP | ||||

| GCN-based DccpLabv3+ | Faster R-CNN | FCOS | YOLOv3 | ||

| single door | 0.885 | 0.827 | 0.843 | 0.859 | 0.829 |

| double door | 0.796 | 0.831 | 0.779 | 0.771 | 0.743 |

| sliding door | 0.874 | 0.876 | 0.556 | 0.494 | 0.481 |

| window | 0.691 | 0.603 | 0.518 | 0.465 | 0.379 |

| bay window | 0.050 | 0.163 | 0.068 | 0.169 | 0.062 |

| blind window | 0.833 | 0.856 | 0.614 | 0.520 | 0.322 |

| opening symbol | 0.451 | 0.721 | 0.496 | 0.542 | 0.168 |

| stairs | 0.857 | 0.853 | 0.464 | 0.487 | 0.370 |

| gas stove | 0.789 | 0.847 | 0.503 | 0.715 | 0.601 |

| refrigerator | 0.705 | 0.730 | 0.767 | 0.774 | 0.723 |

| washing machine | 0.784 | 0.569 | 0.379 | 0.261 | 0.374 |

| sofa | 0.606 | 0.674 | 0.160 | 0.133 | 0.435 |

| bed | 0.893 | 0.908 | 0.713 | 0.738 | 0.664 |

| chair | 0.524 | 0.543 | 0.112 | 0.087 | 0.132 |

| table | 0.354 | 0.496 | 0.175 | 0.109 | 0.173 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).