Introduction

Viruses are commonly categorized into two primary and widely recognized groups: enveloped viruses (EV) and non-enveloped viruses (for non-enveloped viruses, N-EV). This distinction is based on the presence or absence of an external lipid bilayer membrane, which characterizes EV and is absent in N-EV.

Our understanding of enveloped viruses has significantly progressed, largely driven by advancements in structural and cell biology. The development of cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and related imaging techniques, combined with independently resolved atomic structures of virion components, has been fundamental in elucidating virus structure. While the X-ray crystallographic structure of an enveloped animal virus remains unsolved, several enveloped virus structures now achieve near-atomic or perhaps more appropriately, pseudo-atomic resolution. Parallel advancements in cell biology methodologies and reagents have also provided useful insight on the morphogenesis of enveloped viruses. Techniques such as confocal microscopy and other imaging methods have been useful in detailing the pathways and interactions that virion components navigate during assembly and budding.

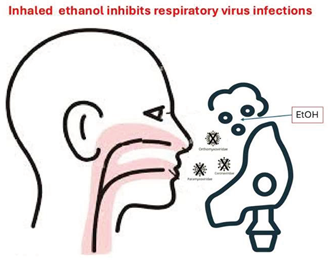

EtOH has demonstrated high efficacy in inactivating enveloped viruses both in vitro [

1,

2,

3] and in vivo (in animal and human studies) [

4,

5,

6].

The inhalation route has been a significant method of drug administration for respiratory disorders since ancient times. Today, it remains the preferred approach for treating numerous pulmonary diseases, including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cystic fibrosis, and pneumonia. The pulmonary route enables targeted drug delivery to the lungs, allowing the drug to reach its site of action directly. This targeted delivery ensures a rapid onset of therapeutic effect, with lower doses required and higher local drug concentrations at the site of pulmonary disease. It also minimizes systemic bioavailability, thus reducing the risk of systemic toxicity and bypassing first-pass metabolism in the liver [

7].

Aerosol therapy allows for further reduction in drug dosages, improved access to “hidden” areas and more precise targeting of specific cells or compartments, ultimately enhancing drug bioavailability. The particle size generated - commonly defined by the Aerodynamic Median Mass Diameter (AMMD) - is closely associated with the specific site of treatment.

This narrative review explores the general structural characteristics of enveloped viruses and examines the potential role of inhaled EtOH in addressing respiratory diseases caused by enveloped viruses.

Enveloped Viruses Are Generally Less Virulent

On the other hand, enveloped viruses are generally less virulent than non-enveloped viruses, as they do not always rely on cell lysis for their exit from host cells, although cell death can still occur as a consequence of viral replication. The presence of an outer membrane, or envelope, surrounding the capsid enables enveloped viruses to incorporate portions of the host cell membrane during assembly and release [

8]. The presence of a membranous envelope is associated with reduced resistance to environmental factors such as desiccation, heat, alcohol, and detergents, which limits the survival of viral particles outside the host. Despite this limitation, the envelope offers several distinct advantages to the virus: (i) it allows viral particles to exit host cells via the cellular exocytosis machinery, minimizing cellular damage and delaying immune detection; (ii) it increases the viral particle's packaging capacity, enabling the incorporation of additional viral proteins; (iii) it conceals the capsid’s structurally fixed antigens from circulating antibodies; and (iv) it offers greater structural flexibility to envelope proteins compared to capsid proteins, enhancing the virus's ability to evade neutralizing immune responses. Most zoonotic viruses are enveloped, likely due to the adaptability of envelope proteins, which facilitates their ability to infect different hosts, although additional adaptations are also necessary. In addition to incorporating host cell phospholipids and membrane proteins, the viral envelope contains viral glycoproteins that are critical for binding to specific host cell receptors. The fusion of the viral envelope with the host cell membrane upon entry allows the capsid to be released into the cytoplasm, initiating viral genome release, replication, and the production of progeny virions. The most prominent enveloped viruses that cause human diseases are listed in

Table 1, with a subset of these viruses specifically associated with respiratory diseases detailed in

Table 2.

What About Viral Envelopes?

During viral maturation, a process called budding allows viral envelopes to form from the membranes of host cells. These membranes may originate from the plasma membrane or from internal structures such as the nuclear membrane, endoplasmic reticulum, or Golgi complex. The lipids that constitute the viral envelope are sourced directly from the host cell, whereas the envelope proteins are encoded by the viral genome.

Two main types of proteins are associated with the viral envelope. The first type consists of glycoproteins, often referred to as peplomers (from peplos, meaning envelope), or spikes. These structures can frequently be observed as distinct projections on the surface of the envelope in electron micrographs. The second type, matrix proteins, are non-glycosylated proteins located within the envelope of virions in certain viral families. Matrix proteins provide structural rigidity to the virion. For example, the rhabdovirus envelope contains a tightly packed bullet-shaped matrix protein that surrounds the helical nucleocapsid. In contrast, arenaviruses, bunyaviruses, and coronaviruses lack matrix proteins, making their envelopes more pleomorphic compared to those of other viruses.

Notably, envelopes are not exclusive to viruses with helical symmetry; certain icosahedral viruses, including ranaviruses, African swine fever viruses, herpesviruses, togaviruses, flaviviruses, and retroviruses, also possess an envelope. For most enveloped viruses, the integrity of the envelope is critical for their infectivity. However, in some cases, such as with certain poxviruses, the envelope is not essential for the virus to remain infectious [

9].

Types and Functions of the Virus Envelope

Nearly one-quarter of viruses have an envelope encasing their protein capsid. This envelope typically consists of a lipid bilayer membrane obtained from the host, embedded with viral-encoded glycoproteins. The characteristics of the envelope, including its size, composition, morphology, and complexity, vary widely among different viral families

Viral glycoproteins are embedded in the lipid bilayer and are essential in the virus-host interactions. In some cases, non-glycosylated viral proteins may also be incorporated into the envelope. The number of glycoproteins differs across viral families. For instance, more than 10 glycoproteins have been identified in viruses belonging to the Herpesviridae family, while simpler viruses such as those in the Togaviridae and Orthomyxoviridae families possess only one or two multimeric proteins.

Additionally, some enveloped viruses encode specialized glycoproteins known as viroporins. These proteins function as ion channels and possess at least one transmembrane domain, along with extracellular regions that interact with host or viral proteins. Examples of viroporins have been identified in influenza A virus, Hepacivirus C (formerly hepatitis C virus), human immunodeficiency virus 1, and coronaviruses.

A structural layer of proteins known as the matrix may be found between the envelope and the capsid in some enveloped viruses (e.g., Orthomyxoviridae and Retroviridae). In other cases, the capsid may directly interact with the internal tails of membrane proteins, as observed in Togaviridae and Bunyavirales. The envelope and associated proteins primarily function in processes such as recognition, attachment, and entry into host cells through fusion with host membranes. The envelope also plays a significant role in helping viruses evade the mammalian host's immune response, conferring an evolutionary advantage.

From an evolutionary perspective, viral envelope proteins have been co-opted into vertebrate genomes, playing significant roles in biological processes. A notable example is the syncytin genes, which originate from retroviral envelope proteins and have been adapted for critical functions in placental morphogenesis. This represents a striking case of convergent evolution, where viral-derived genes have been repurposed to enable placentation in several species [

10].

Respiratory Viruses

As shown in

Table 2, most respiratory viruses are enveloped. These are among the most prevalent causes of disease in humans and have a significant global impact, particularly on children. Acute respiratory infections (ARI) are responsible for about one-fifth of all childhood deaths worldwide, with the burden being disproportionately higher in impoverished tropical regions compared to temperate areas. This disparity is due to higher ARI case-fatality ratios in these regions. The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has underscored the profound impact that human respiratory viruses can have on global health.

Respiratory viruses from various families have evolved to efficiently transmit from person to person and are found circulating globally. Community-based studies confirm that these viruses are the leading causes of ARI. The most commonly circulating respiratory viruses, endemic or epidemic, include influenza viruses, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza viruses, metapneumovirus, rhinovirus, coronaviruses, adenoviruses, and bocaviruses (

Table 2).

Given the prevalence and impact of these viruses, this review focuses particularly on enveloped respiratory viruses, such as coronaviruses. The viral envelope, derived from the host cell membrane, is vulnerable to specific disruptions. Unlike host membranes, viral envelopes lack metabolic turnover and cannot repair themselves once the virus has budded. This inherent vulnerability has long been exploited by disinfectants to inactivate enveloped viruses.

Moreover, this review highlights new therapeutic possibilities, such as the use of nebulized EtOH solutions to interfere with the transmission and infectivity of enveloped respiratory viruses. This approach provides an innovative avenue for limiting the spread of these pathogens, particularly in healthcare and community settings where ARI poses a significant risk [

11].

What Is EtOH?

Ethanol, or ethyl alcohol, known simply as alcohol, is a linear alkyl chain alcohol. Its condensed structural formula is CH3CH2OH. In chemistry, it can also be found abbreviated with the acronym EtOH or C2H6O.

How Does EtOH Work on Enveloped Viruses?

EtOH most likely inactivates enveloped viruses (EV) by disrupting their structural components, as viruses lack a metabolism unlike bacteria. Enveloped viruses are structured with a genomic core encased in a protein shell, further surrounded by an outer lipid bilayer. According to Watts et al. [

1], EtOH can interact with all three of these components: it can denature protein, fluidize and overall reorganize the structures of the lipid bilayers through the modification of the lipid packing by its cosurfactant actions, and aggregate DNA and RNA.

Watts et al. noted that the detailed nano-structural and surface-chemical effects of EtOH on enveloped viruses had not been fully explored. To address this, they used the Phi6 bacteriophage as a model. Phi6 is an 85 nm-diameter enveloped bacteriophage that infects Pseudomonas bacteria and serves as a surrogate for enveloped human viruses like influenza, Ebola, and SARS-CoV-2.

The Phi6 envelope is composed of a lipid bilayer derived from the plasma membrane of its bacterial host, containing a high density of viral membrane proteins. The most abundant of these is the major envelope protein P9, which facilitates vesicle formation from the plasma membrane and associates with the nucleocapsid. The nucleocapsid, located beneath the membrane, contains the virus's three double-stranded RNA segments.

Their research revealed that EtOH’s primary disruptive effect is on the envelope structure rather than the protein capsid. However, envelope proteins and their interactions with the nucleocapsid play a critical role in stabilizing the bilayer structure. This finding suggests that destabilizing the lipid envelope is a key mechanism through which EtOH inactivates enveloped viruses.

No significant modifications in the lipid envelope were observed up to EtOH 20%.

At 50% EtOH concentration, the lipid bilayer of the enveloped virus separates from the nucleocapsid and loses its bilayer structure. This structural disintegration correlates directly with a complete loss of viral infectivity at the same EtOH concentration, highlighting EtOH’s unspecific but effective mode of action in destroying the lipid membrane. This broad-spectrum activity is thought to extend to human pathogenic enveloped viruses such as Ebola, influenza, and coronaviruses [

1].

Manning et al. [

12] further explored EtOH's mechanism of action, focusing on its interaction with protein structures. EtOH interferes with intramolecular hydrogen bonds between the side chains of proteins. These bonds are crucial for maintaining the tertiary structure of proteins, which in turn is essential for their function [

13]. EtOH’s hydroxyl group (-OH) competes as a hydrogen bond donor or acceptor, disrupting these bonds and destabilizing protein structures. While other alcohols like methanol and propanol can act similarly, their higher toxicity limits their use in vivo.

Manning et al. also addressed the challenges of translating in vitro findings into effective in vivo treatments. In the human respiratory system, sputum and mucus on the respiratory epithelium may impede a molecule's access to its viral target, even if the molecule demonstrates efficacy in vitro. Using Lipinski’s rules and Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models, they developed the Penetration Score (PS), a metric that estimates the likelihood of a molecule penetrating a mucus layer. PS values are calculated relative to water, the most abundant molecule in vivo. A low PS indicates a better candidate for in vivo applications. EtOH, with a very low PS, is thus a promising candidate for treating conditions like COVID-19, where mucus accumulation in the lungs is common.

This low PS helps explain why some in vitro-effective drugs, such as Remdesivir, may fail to achieve the same efficacy in vivo. EtOH’s ability to penetrate mucus layers, combined with its broad-spectrum activity against enveloped viruses, makes it a strong candidate for therapeutic use in respiratory infections.

Manning et al. [

14] also calculated the amount of alcohol needed to clear SARS-CoV-2 viral load affecting the lungs: 153 µg of EtOH or 191.25 µL.

Studies suggest that viral loads in the lungs, often higher than in other parts of the respiratory tract, are correlated with the severity of COVID-19 [

15]. Therefore, a direct treatment targeting the infection from the mouth to the alveoli could be the most effective approach.

Tamai et al. [

4] investigated the effect of EtOH on Influenza A virus (IAV)-infected mice. Their findings indicate that EtOH not only directly inactivates extracellular IAV but also suppresses progeny virus production in the respiratory tract. Interestingly, the virucidal efficacy of low-concentration EtOH solutions in the respiratory tract was observed to be higher than that on environmental surfaces, likely due to temperature effects. While the inactivation of extracellular IAV by EtOH is attributed to its ability to disrupt viral envelopes, the mechanism by which EtOH suppresses progeny virus production remains unclear.

Tamai et al. also noted that IAV-induced expression of type I interferon-related genes was not affected by EtOH, suggesting that further research is needed to determine whether EtOH enhances antiviral immunity. This is particularly relevant because EtOH is known to modulate several immune-related pathways [

16]. Additionally, they recommended investigating EtOH’s effects on viral proteins or the cellular metabolism of virus-infected epithelial cells, given its previously reported activities [

17].

Recently, Hancock et al. [

18] confirmed the efficacy of inhaled EtOH in another influenza-infection mouse model, both in terms of lowering the viral load and increasing the macrophagic response.

Nomura et al. [

19] examined the effect of various EtOH concentrations on SARS-CoV-2 infectivity. They found that a 99% reduction in infectious titers occurred at an EtOH concentration of 24.1% (w/w) [29.3% (v/v)]. For comparison, ETOH was tested against other enveloped viruses, including influenza virus, vesicular stomatitis virus (Rhabdoviridae), and Newcastle disease virus (Paramyxoviridae). The 99% inhibitory concentrations were 28.8% (w/w) [34.8% (v/v)], 24.0% (w/w) [29.2% (v/v)], and 13.3% (w/w) [16.4% (v/v)], respectively. Some differences from SARS-CoV-2 were observed, but the differences were not significant. It was concluded that EtOH at a concentration of 30%(w/w) [36.2% (v/v)] almost completely inactivates SARS-CoV-2.

Recently, Jia et al. [

20] discovered that high expression of oleoyl-acyl-carrier-protein (ACP) hydrolase (OLAH) is a key factor in life-threatening respiratory viral diseases, including avian A(H7N9) influenza, seasonal influenza, COVID-19, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). OLAH is an enzyme involved in fatty acid production, primarily oleic and palmitic acids, which are known for their proinflammatory activity. Due to EtOH action on lipids, it is also possible to hypothesize its beneficial effect on lowering the inflammatory status connected with these diseases.

EtOH Inhalation Toxicity

Three major considerations must be taken in account:

i) Firstly, there is a notable distinction between EtOH that is ingested and EtOH that is inhaled. Inhaled EtOH bypasses the initial metabolic step required for ingested EtOH and instead directly reaches the left ventricle of the heart and the brain.

ii) Secondly, the chronic use of EtOH differs from chronic EtOH abuse, which can lead to lung damage, including alveolar macrophage dysfunction and an increased risk of bacterial pneumonia and tuberculosis [

21].

iii) Finally, chronic intoxication has to be differentiated from acute one.

The inhalation/absorption rate, i.e. the amount of EtOH that passes from the alveoli to the bloodstream, is 62%. [

22]

EtOH is eliminated from the body at a rate of 120 to 300 mg/L/hour [

23]. Approximately 95% of consumed (or inhaled) EtOH is metabolized by alcohol dehydrogenase, while the remaining 5% is excreted unchanged through exhaled air, urine, perspiration, saliva, and tears.

(i) Blood levels below 184.2 mg/L (4 mmol/L): asymptomatic.

(ii) Blood levels up to 460.6 mg/L (10 mmol/L): associated with behavioral and cognitive changes.

(iii) Blood levels exceeding 460.6 mg/L (10 mmol/L): considered toxic.

(iv) Blood levels above 2763.7 mg/L (60 mmol/L): may result in coma or death.

The serum concentrations observed following EtOH inhalation are significantly lower than those linked to toxicity or fatal outcomes [

24].

It is worth noting that regulations concerning acute EtOH exposure vary across nations or states, with legal limits on Blood Alcohol Concentration (BAC) generally ranging between 500 and 800 mg/L. Additionally, workplace regulations impose restrictions on maximum levels of chronic EtOH exposure.

Regarding acute EtOH inhalation, Bessonneau [

22] demonstrated that during 90 seconds of hand disinfection using a gel with an EtOH concentration of 700 g/L, the cumulative inhaled dose of EtOH was approximately 328.9 mg (~65.78 mg/L).

Healthcare workers may disinfect their hands as many as 30 times per day [

25], resulting in an estimated daily inhaled EtOH dose of 9.86 grams. Clinically, this repetitive exposure could lead to a state of subacute, rather than acute, intoxication, and such occupational practices could contribute to chronic EtOH exposure over time. Clinically, this repetitive exposure could lead to a state of subacute, rather than acute, intoxication, and such occupational practices could contribute to chronic EtOH exposure over time.

For workers in the alcohol production industry in the United Kingdom, the occupational exposure limit (OEL) for EtOH is set at 1000 parts per million (ppm) or 1910 mg/m³ during an eight-hour work shift. This exposure is roughly equivalent to the daily consumption of 10 grams of EtOH, approximately the amount in one glass of alcohol [

26]. These findings align closely with Bessonneau's analysis [

22] and exceed the theoretical amount needed to reduce viral loads in the respiratory tract, as estimated by Manning et al. [

14].

Concerns regarding EtOH inhalation and potential damage to the respiratory tract were addressed by the detailed study of Castro-Balado et al. [

5]. This research examined possible mucosal or structural harm in the lungs, trachea, and esophagus of rodents exposed to 65% v/v EtOH for 15 minutes every eight hours (three times daily) over five consecutive days, at a flow rate of 2 L/min. Importantly, histological analysis revealed no signs of damage in the treated animals or the control group. The absorbed EtOH dosage in this experiment was calculated to be 1.2 g/kg/day. Translating this dosage to humans would correspond to an exposure of 151 grams per day.

Interestingly, in the randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted by Hosseinzadeh [

27], no collateral effects were reported, likely due to their absence or their minimal and tolerable nature, while Amoushahi et al. noted only a few mild and bearable adverse events [

28].

Furthermore, multiple studies suggest that industrial EtOH exposure does not pose significant issues in reproductive medicine [

29] or oncology [

26], despite the known toxicity associated with chronic EtOH inhalation.

Sisson's work [

30] demonstrated that EtOH's effect on respiratory ciliary cells follows a bimodal pattern depending on both exposure time and dosage. Specifically, low concentrations of EtOH (10 mM = 0.46 mg/ml) were found to enhance ciliary clearance, potentially facilitating the elimination of viral loads after they have been theoretically inactivated by EtOH's physicochemical properties.

More recently, Hancock et al. [

31] conducted a phase I, single-centre, open-label clinical trial in healthy adult volunteers assessing the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of inhaled EtOH. EtOH was nebulized using a standard jet nebulizer, together with a closed-circuit reservoir system. No serious adverse events were reported with only small transient increases in heart rate, blood pressure, and blood neutrophil levels.

Although EtOH could theoretically exert a negative impact on the respiratory microbiome, no evidence supporting this has been found in current literature. On the contrary, some insights may suggest otherwise. For instance, Sulaiman et al. [

15] observed that poor clinical outcomes were associated with the enrichment of the lower respiratory tract microbiota by an oral commensal, the

Mycoplasma salivarium, and with an increased SARS-CoV-2 viral load in a group of intubated COVID-19 patients. Similarly, Rueca et al. [

32] reported a complete depletion of

Bifidobacterium and

Clostridium in the nasal/oropharyngeal microbial flora of intensive care patients with SARS-CoV-2. Comparable findings have been recently corroborated by Chu et al. [

33].

It is worth noting that both

Mycoplasma salivarium and SARS-CoV-2 [

34] are fully inactivated by EtOH. Additionally, certain strains of

Clostridium are known to produce endogenous EtOH [

35], raising the possibility that their absence could deprive the host of a potential defense mechanism.

Lastly, Kramer et al. [

36] reported that frequent use of alcohol-based antiseptics had no adverse effects on the hand microbiome of healthcare workers.

EtOH in Medicine

In addition to its widespread industrial and recreational applications (e.g., spirits, cosmetics, fuel), EtOH is recognized as a medicinal agent and is listed in both the European and US Pharmacopeias. Medically, EtOH is primarily utilized as an antidote for methanol and ethylene glycol poisoning, as an excipient in numerous medications, as a sclerosant agent, and as a highly effective disinfectant for both skin and surfaces.

Historically, EtOH inhalation was demonstrated to be both safe and effective for the treatment of coughs and pulmonary edema [

37,

38,

39,

40].

Moreover, EtOH is commonly used as an excipient in inhalation treatments for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), with doses as high as 9 mg per actuation [

41].

Current Knowledge on EtOH Inhalation for Enveloped-Virus Respiratory Diseases

The search for reference material was carried out by consulting online databases for existing work relevant to the topic. PubMed, MEDLINE, ScienceDirect, Scopus, and Google Scholar (the latter to identify both published and unpublished information) were searched, utilizing specific keywords and applying publication date and other filters. The search revealed limited data on this topic, especially when compared to extensive literature on the use of EtOH for hand and surface disinfection.

In the context of prevention, Hosseinzadeh et al. [

27] conducted a randomized controlled trial involving healthcare workers from medical centers at the frontline of the COVID-19 pandemic. This study aimed to assess the efficacy of combining EtOH with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in a nasal spray format for preventing COVID-19. The results indicated that the incidence rates of COVID-19 were 0.07 in the control group and 0.008 in the intervention group. The relative risk was calculated at 0.12 (95% CI: 0.02–0.97), leading the authors to conclude that the combined use of DMSO and EtOH can significantly reduce the incidence of COVID-19 among healthcare providers.

Anecdotal reports have suggested that alcohol consumption could help prevent the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and potentially mitigate its effects. Tong and Salvatori [

42] conducted a cross-sectional study within a social community, which, despite its methodological limitations, found a statistically significant association between increased alcohol consumption and a lower likelihood of contracting SARS-CoV-2. One possible explanation for these findings was the dual action of inhaled and ingested EtOH acting as a disinfectant for the naso-oro-pharyngeal mucosa and the respiratory tract through exhaled EtOH. However, the authors cautioned against drawing misleading conclusions and explicitly advised against using EtOH as a medical treatment. The study instead highlighted the potential role of inhaled EtOH in combating SARS-CoV-2.

In the treatment domain, Castro-Balado et al. [

43] conducted the ALCOVID-19 trial, aimed at evaluating the safety and efficacy of inhaled EtOH in older adults during the early stages of infection. The study found no significant difference in disease progression between treatment and control groups. However, a reduction in viral load was observed in the treatment group, though not statistically significant. Importantly, inhaled EtOH was deemed safe, as no plasma EtOH was detected, and no electrocardiographic, analytical, or respiratory issues were noted. It is worth mentioning that the trial was terminated early due to difficulties in participant recruitment.

Amoushahi et al. [

28] conducted a randomized clinical trial (RCT) involving 99 symptomatic, RT-PCR-positive patients hospitalized and receiving remdesivir-dexamethasone. Patients were randomly assigned to either the control group (CG), receiving distilled water spray, or the intervention group (IG), which received a 35% EtOH spray. The primary outcome was the Global Symptomatic Score (GSS), measured at the first visit and on days three, seven, and 14. Secondary outcomes included the Clinical Status Scale (CSS) and readmission rates.

The results showed no significant difference in the GSS or CSS at admission. However, by day 14, both the GSS and CSS improved significantly in the IG (p = 0.016 and p = 0.001, respectively). Additionally, the readmission rate was considerably lower in the IG (0% vs. 10.9%; p = 0.02). Based on these findings, the authors concluded that inhaled-nebulized EtOH is effective in rapidly improving clinical status and reducing the need for further treatment. Due to its low cost, availability, and minimal adverse effects, they recommended it as an adjunctive treatment for moderate COVID-19.

Tamai et al. [

4] conducted a study on mice treated with EtOH vapor twice daily, beginning the day before intranasal administration of Influenza A virus (IAV). The treatment group showed significantly less weight loss compared to the control group. On day 10 post-infection, 63% of untreated mice (17 of 27) reached the humane endpoint (20% body weight loss), while only 11% of treated mice (3 of 27) reached the same point.

EtOH vapor treatment was shown to reduce viral titers in the lungs, but not in the nasal cavity, on day 3 after infection. Furthermore, the treatment also led to a reduction in leukocyte infiltration and lung damage, with a decrease in monocytes and macrophages in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). Despite this reduction, the viability of these cells was somewhat preserved. Additionally, EtOH vapor treatment significantly decreased the expression of genes associated with innate immunity, such as Irf7, in lung tissues.

Overall, the study suggests that inhalation of EtOH vapor can reduce viral load in the lungs and protect mice from lethal IAV infection, with no detectable adverse effects.

Finally, Hancock et al. [

31] concluded that concentrations up to 80% of Inhaled EtOH are safe and efficacious, suggesting further studies for assessing its use as treatment for respiratory infections.

Conclusions

The research data suggests that EtOH inhalation could potentially play a beneficial role in treating respiratory infections caused by enveloped viruses. Based on the findings, a 50% EtOH concentration appears to be a reasonable option for inhalation therapy. The best delivery method would likely involve an aerosol device capable of generating particles with an average mass median diameter (AMMD) of 5 µm to ensure effective deposition in the respiratory tract.

In terms of treatment scheduling, delivering EtOH every 8 hours for 1-2 weeks seems to be a promising regimen, offering adequate therapeutic effects with minimal or no side effects, though further research is needed to confirm the optimal timing and frequency.

Patient selection should exclude individuals with certain conditions or circumstances, such as: infancy, alcoholism or a history of adverse reactions to EtOH, drug addiction or previous treatment for alcoholism/drug addiction, currently on disulfiram or cimetidine, non-drinkers of alcohol (no absolute criteria), any liver disease, uncontrolled diabetes, acute or chronic pancreatitis, serious respiratory diseases, tuberculosis or other mycobacterial infections, confirmed or suspected pregnancy, active psychosis, inability to give legally valid informed consent.

Despite the promising preliminary results, there is a clear gap in well-designed clinical trials assessing the efficacy of EtOH inhalation in treating respiratory infections. Therefore, conducting carefully structured studies is essential. This low-cost therapy could become an important therapeutic option, especially for large numbers of patients simultaneously infected, as was the case during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, inhaled EtOH could be a successful approach for fragile patients as cancer patients because it is likely to have no or minimal effects on already established life-saving treatments. Further investigation by national and international institutions is urgently needed to validate these findings and refine treatment protocols.