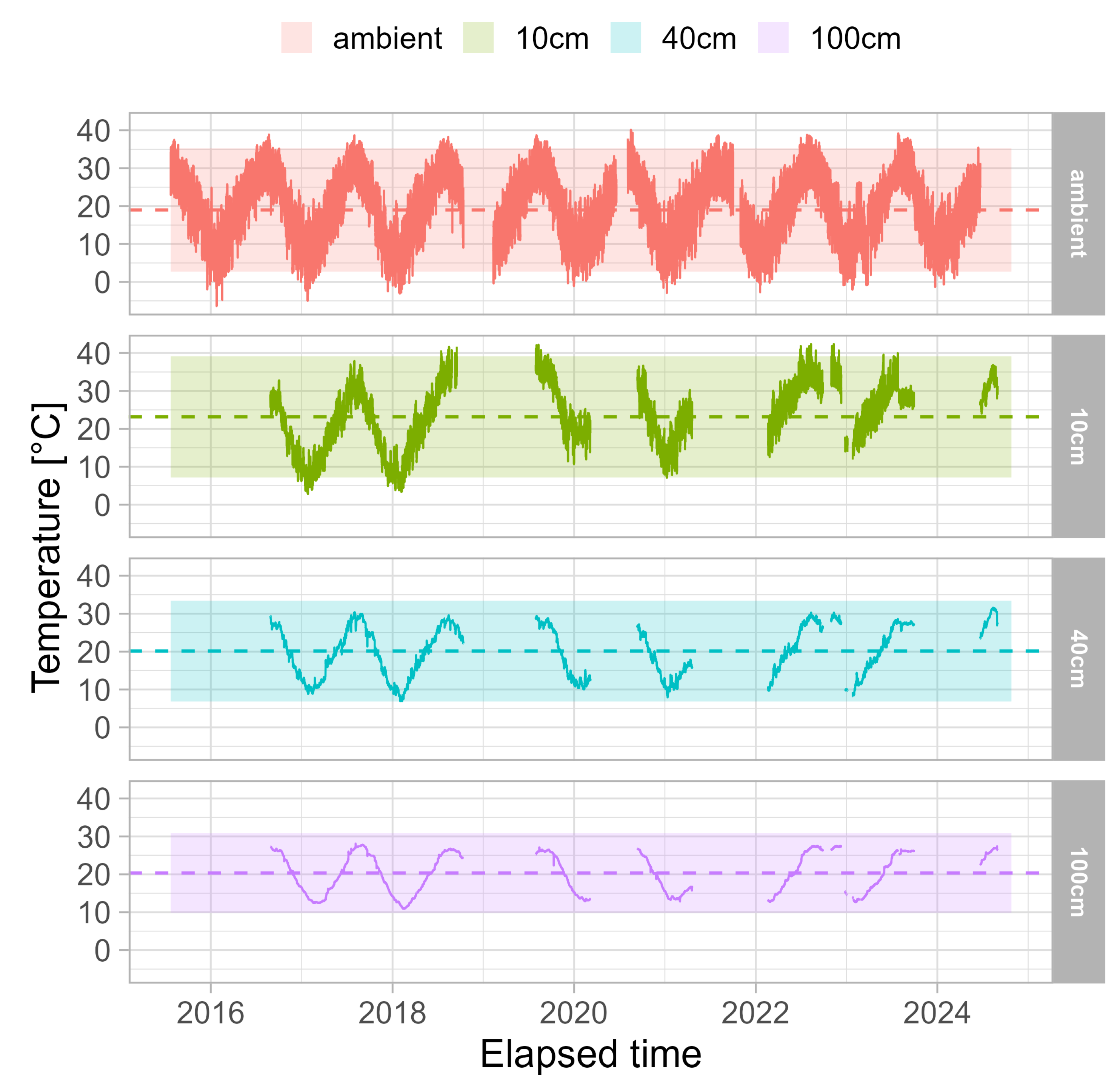

A clear thermal gradient is evident, with temperature lines at different depths exhibiting noticeable fluctuations. The temperature range at a depth of 100 cm is significantly smaller compared to the shallower depths of 10 cm and 40 cm. This finding indicates potential variations in the soil’s thermal properties, with deeper layers exhibiting enhanced stability. Both ambient and soil temperatures demonstrate clear seasonal variations, with the amplitude of temperature fluctuations diminishing with increasing depth. At the ambient level as well as at depths of 10 cm and 40 cm, temperature fluctuations between summer and winter are more pronounced. Conversely, the 100-cm depth exhibits a more stable temperature throughout the year, suggesting that deeper soil layers are less influenced by surface temperature variations. As previously indicated, the development of a model capable of predicting soil temperature based on measurements of outdoor temperature will facilitate more precise and efficacious data analysis, particularly in cases where radon transport or permeability are being investigated or for statistical analysis like trend and harmonic.

3.2. Modelling

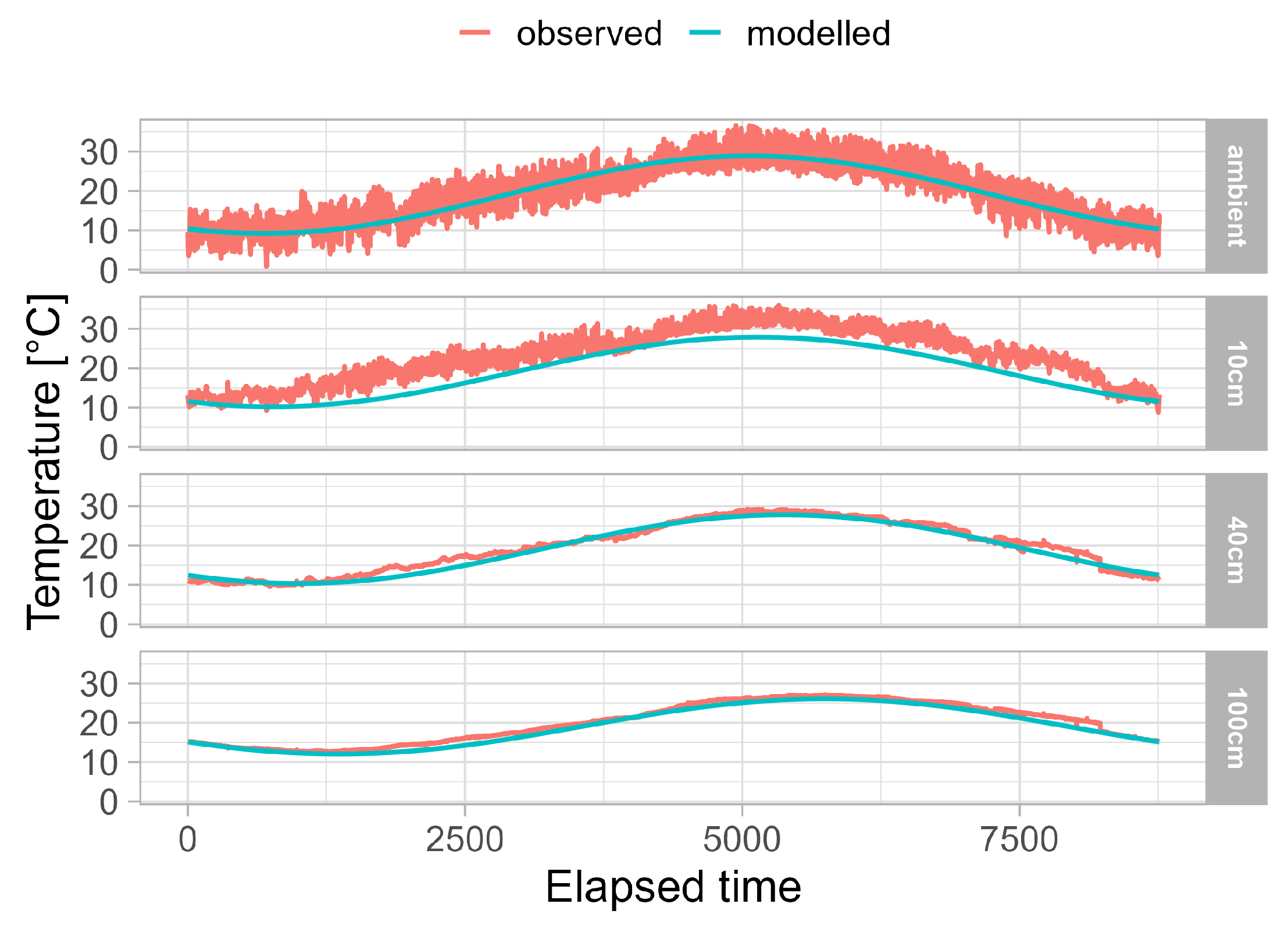

The temperature oscillations were modelled using Equations (

1) and (

2), with average values taken from the 9-year measurement period for different depths and ambient conditions. The results presented in

Table 2 summarizes the fitted values of thermal diffusivity (

),

and peak temperature times (

,

).

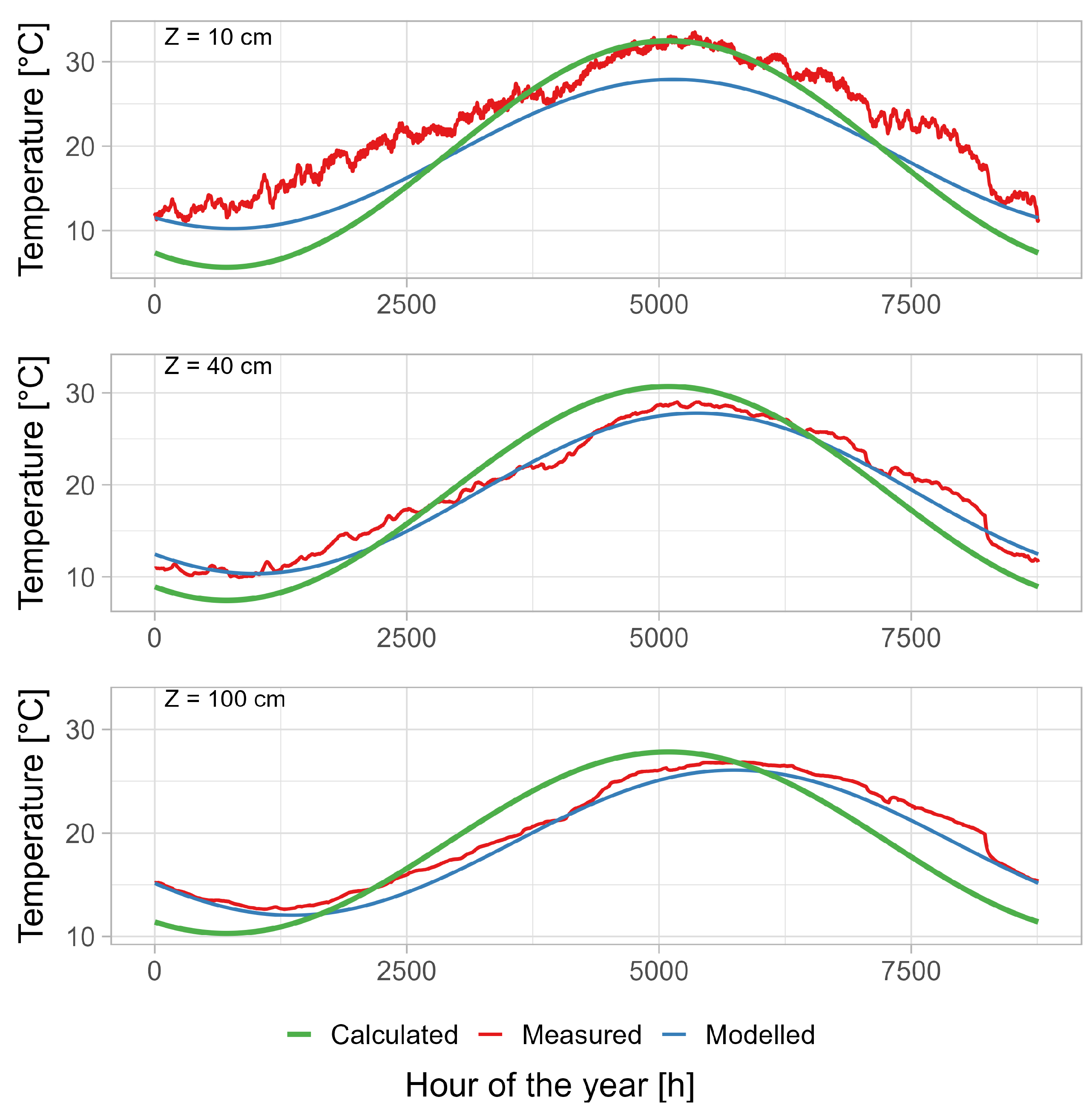

Observed and modelled temperature data are compared in

Figure 2, with the corresponding fit parameters presented in

Table 2.

As shown, the observed ambient and 10 cm depth temperatures exhibit higher frequency fluctuations and generally higher peak values compared to deeper measurements. While the model captures the overall seasonal trend, it underestimates temperature fluctuations, particularly at the surface (10 cm). As depth increases, the agreement between calculated and observed temperatures improves, with the curves aligning more closely at 40 cm and 100 cm. This suggests that the model performs better at greater depths, where temperature variations are more stable, confirming the phenomenon of thermal buffering.

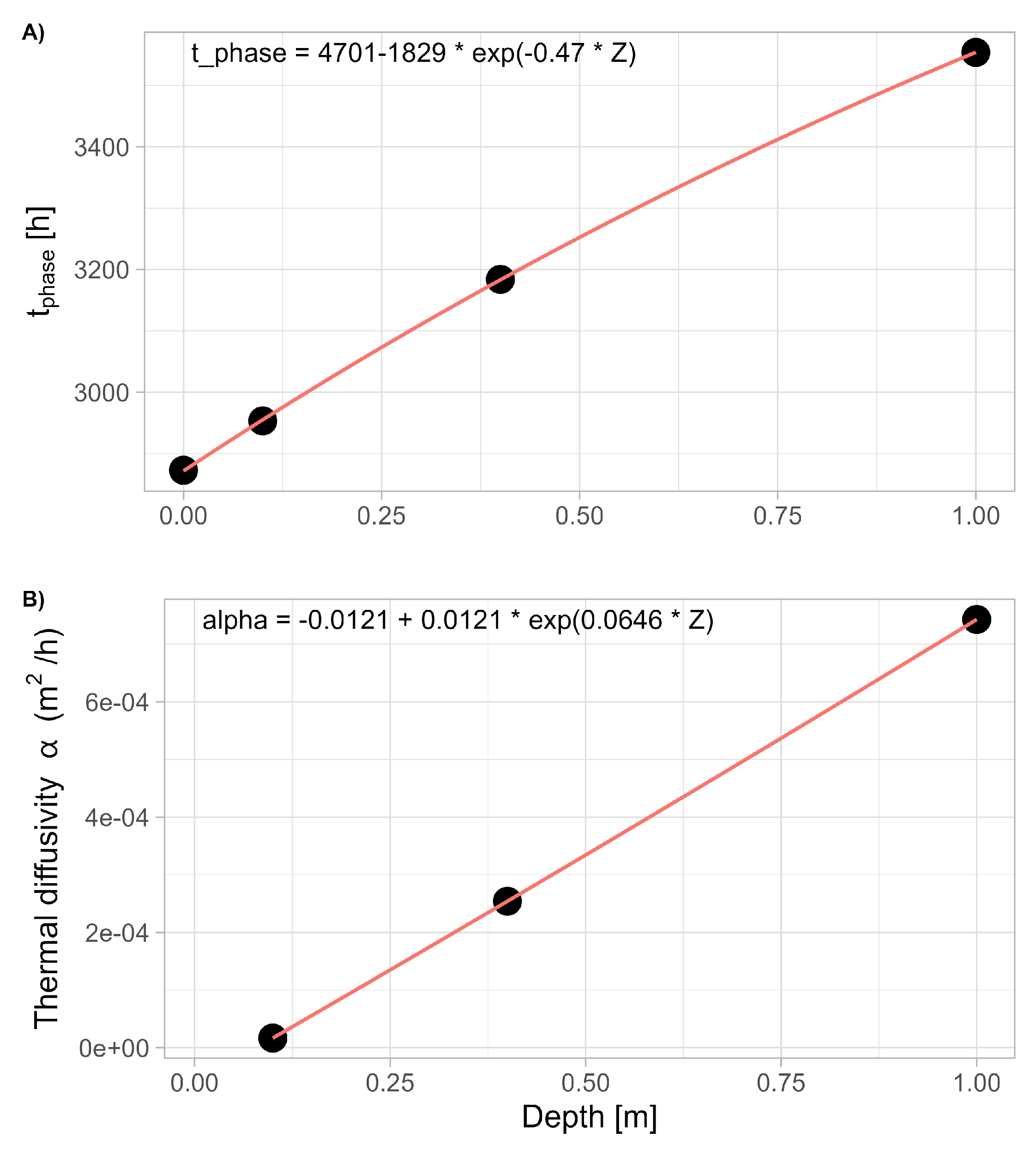

The observed increase in soil thermal diffusivity (

) and the phase parameter of sinusoidal temperature oscillation (

) with depth, as presented in

Table 2 and

Figure 3, reflects the combined effects of soil composition, structure, and moisture content.

The relationship between

and depth (

Z) follows an exponential decay curve, i.e.,

. The phase parameter increases from about 2900 to 3500 hours, indicating that deeper soil layers take longer to reach their minimum and maximum values than shallower layers (

Figure 3A). This delay with depth can be attributed to the insulating properties of the soil.

Moreover, the relationship between thermal diffusivity (

) and depth (

Z) is found to be exponential, i.e.

, which means an increase from almost zero at the surface to about 7 ×

at a depth of 100 cm (see

Figure 4B).

At shallow depths, reduced thermal diffusivity is attributed to increased porosity, organic matter content, and the presence of air-filled pores, which serve to reduce thermal conductivity. At greater depths, soil compaction, increased bulk density, enhanced particle-to-particle contact, and stabilised moisture content improve thermal conductivity, while decreasing organic matter and reduced temperature fluctuations further contribute to higher thermal diffusivity. These findings emphasise the pivotal role of depth-dependent soil properties in modifying and delaying temperature variations, which has substantial implications for ground temperature modelling. The gradient in thermal diffusivity affects heat and mass transfer processes, including the transport of soil gases such as radon, influencing temperature-driven convective flows and diffusion rates within the soil matrix.

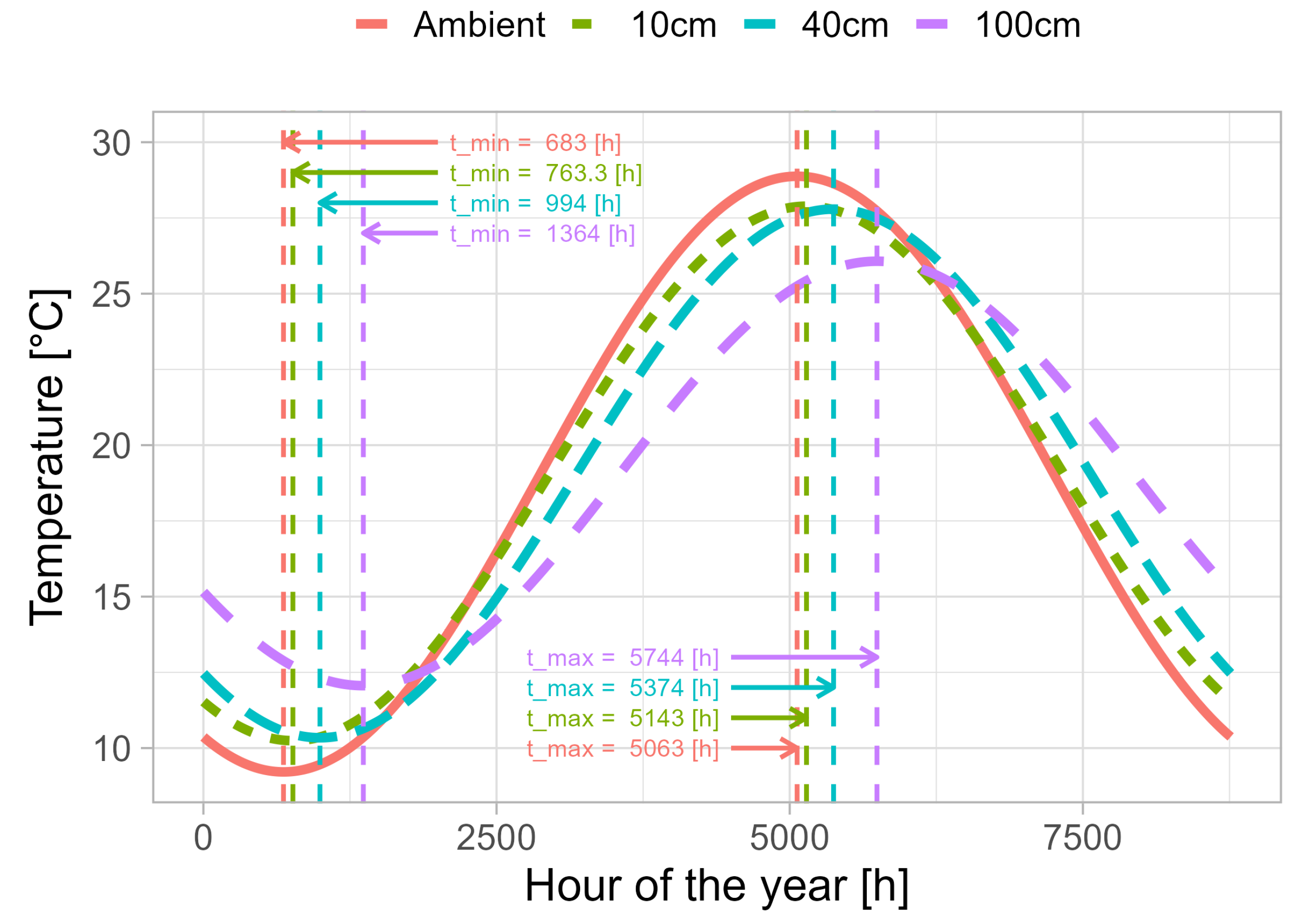

Figure 4 illustrates the modelled temperature variations at varying soil depths (10 cm, 40 cm, and 100 cm) and ambient conditions over the course of a year with the initial parameters of

and

from

Table 2.

The temperature curves demonstrate a sinusoidal pattern indicative of annual temperature cycles, with temperatures ranging from approximately C to C. The amplitude of temperature variation exhibits a decrease with depth.

A critical aspect of the graph is the time shift in minimum and maximum temperatures at varying depths. The analysis reveals that minimum temperatures progressively lag with increasing depth relative to the ambient minimal temperature observed at the end of January (≈ 683 hours of the year ∼ 28 days). The delay is 88 h (≈3.5 days ∼end of January) at a depth of 10 cm, 311 hours at 40 cm (≈13 days ∼middle of February), and 681 h at 100 cm (≈28 days ∼end of February). A similar trend is observed for maximum temperatures, which also exhibit a lag with depth in relation to the maximum of ambient temperature at 5064 hours of the year (≈end of July). The delay is 79 h at 10 cm (≈3.3 days ∼begining of August), 310 h at 40 cm (≈13 days ∼middle of August) and 680 h at 100 cm (≈28 days ∼end of August). This phenomenon can be attributed to the principles of heat diffusion and the soil’s buffering effect on temperature fluctuations, which cause a delay and attenuation of temperature signals as they propagate through the soil medium, with each successive layer contributing to the cumulative delay.

Figure 5 compares modelled and observed soil temperature data, where each hour of the day represents the mean value for that specific hour calculated over the 9-year measurement period. Data were modelled using Equation (

2) with input parameters as literature values of

for volcanic soil [

11,

12] and a

as the observed minimum ambient temperature.

The observed temperatures exhibit higher frequency fluctuations and generally higher peak values, particularly at the shallow depth of 10 cm. The model’s predictions effectively capture the overall seasonal trends but tend to underestimate temperature variations, especially near the surface. The agreement of oscillation between modelled and observed temperatures improves with increasing depth, indicating enhanced model performance in more thermally stable, deeper soil layers. However, a notable discrepancy exists between the measured and modelled temperatures (using constant and for all layers) for deeper layers, particularly regarding the time difference in the occurrence of minimum and maximum temperature values. This observation suggests that literature values of thermal diffusivity cannot be generalized and should account for specific soil properties and depth-dependent variations. The findings underscore both the necessity for precise temperature measurements to facilitate a comprehensive understanding of radon transport processes and the intricate nature of temperature dynamics across soil layers, particularly highlighting the challenges associated with accurately modeling near-surface temperature variations.

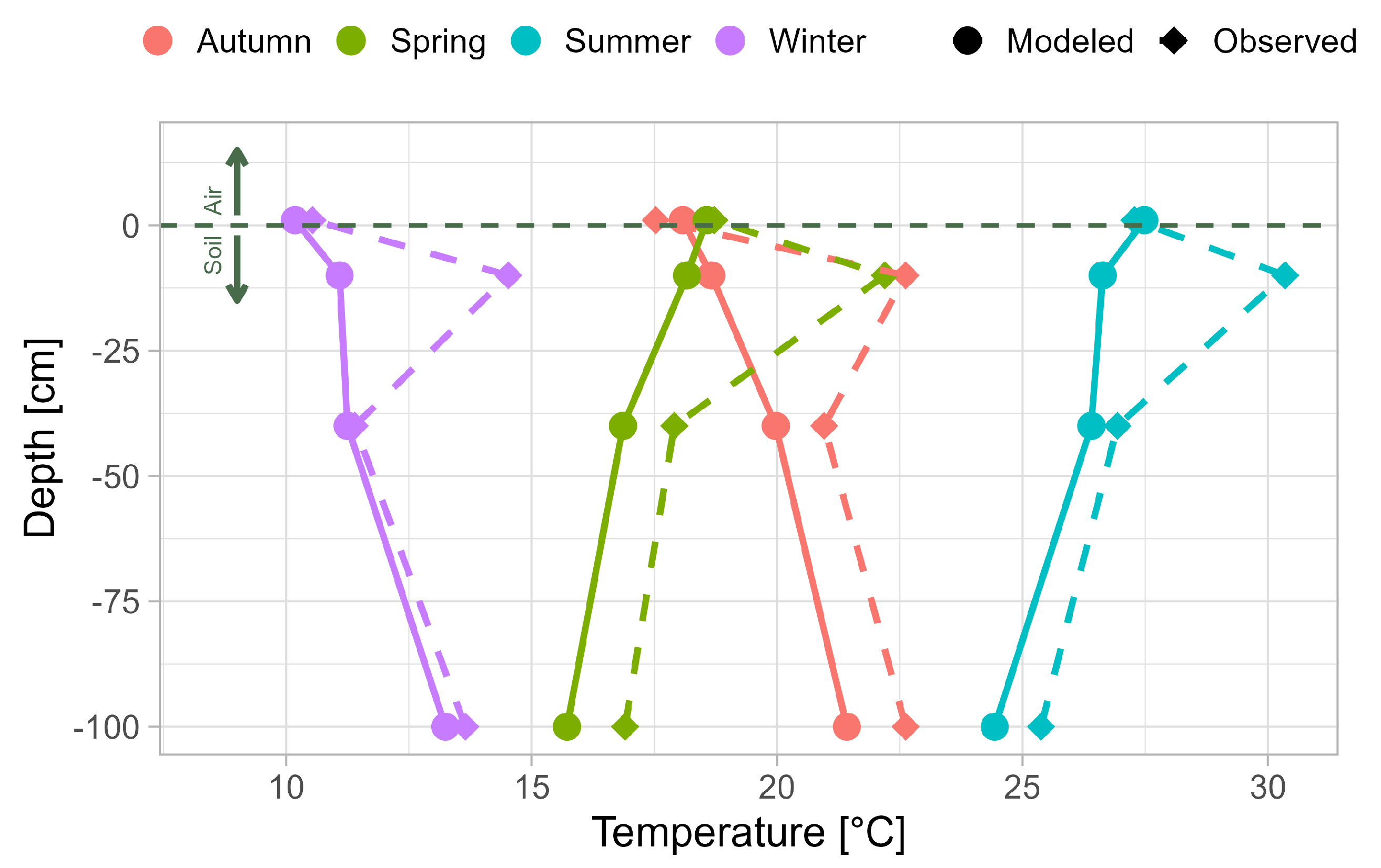

Figure 6 illustrates the seasonal variation of soil temperature profiles for both modelled and observed data with all layers (ambient and depth) for the average value of the entire period. The temperature profiles show clear seasonal stratification, with temperatures ranging from approximately 10 °C to 27 °C for the modelled data and from 11 °C to 32 °C for the observed data. Winter exhibits the coolest temperatures, while summer shows the warmest, with spring and autumn representing transitional periods. These findings reveal a distinct thermal gradient, demonstrating increasing thermal buffering with soil depth, which can be linked to an increase in thermal diffusivity.

However, the comparison reveals significant differences between observed and modelled soil temperatures at 10 cm depth across all seasons. These discrepancies are most pronounced in the transition seasons (spring and autumn), where the modelled temperatures consistently deviate from the observed values. This disparity may be attributable to either the influence of surface ambient conditions or potential sensor malfunctions.

The temperature profiles reveal interesting pattern similarities between winter-autumn and summer-spring pairs, demonstrating seasonal coupling in soil temperature dynamics (seasonal coupling refers to the synchronized patterns of change in soil temperature across different depths over the course of a year, driven primarily by seasonal variations in surface heat fluxes influenced by factors like solar radiation, air temperature, and precipitation).

In the winter-autumn pair, both seasons show that the temperature increases with depth, being lowest at ground level. In the spring-summer pair, the temperature decreases with depth. Therefore, the largest temperature range is observed at 0 cm and the smallest at 100 cm. At 10 cm and 40 cm depths, the temperature ranges are comparable; however, in the spring-autumn pair, the difference increases with depth.

These seasonal couplings likely reflect the transition periods in annual soil temperature cycles, where winter-autumn represents the cooling phase and summer-spring the warming phase of the soil profile. The similarity in patterns despite different absolute temperatures indicates the consistent nature of heat transfer processes during these paired seasons, though the model captures these dynamics with varying degrees of accuracy across different depths.

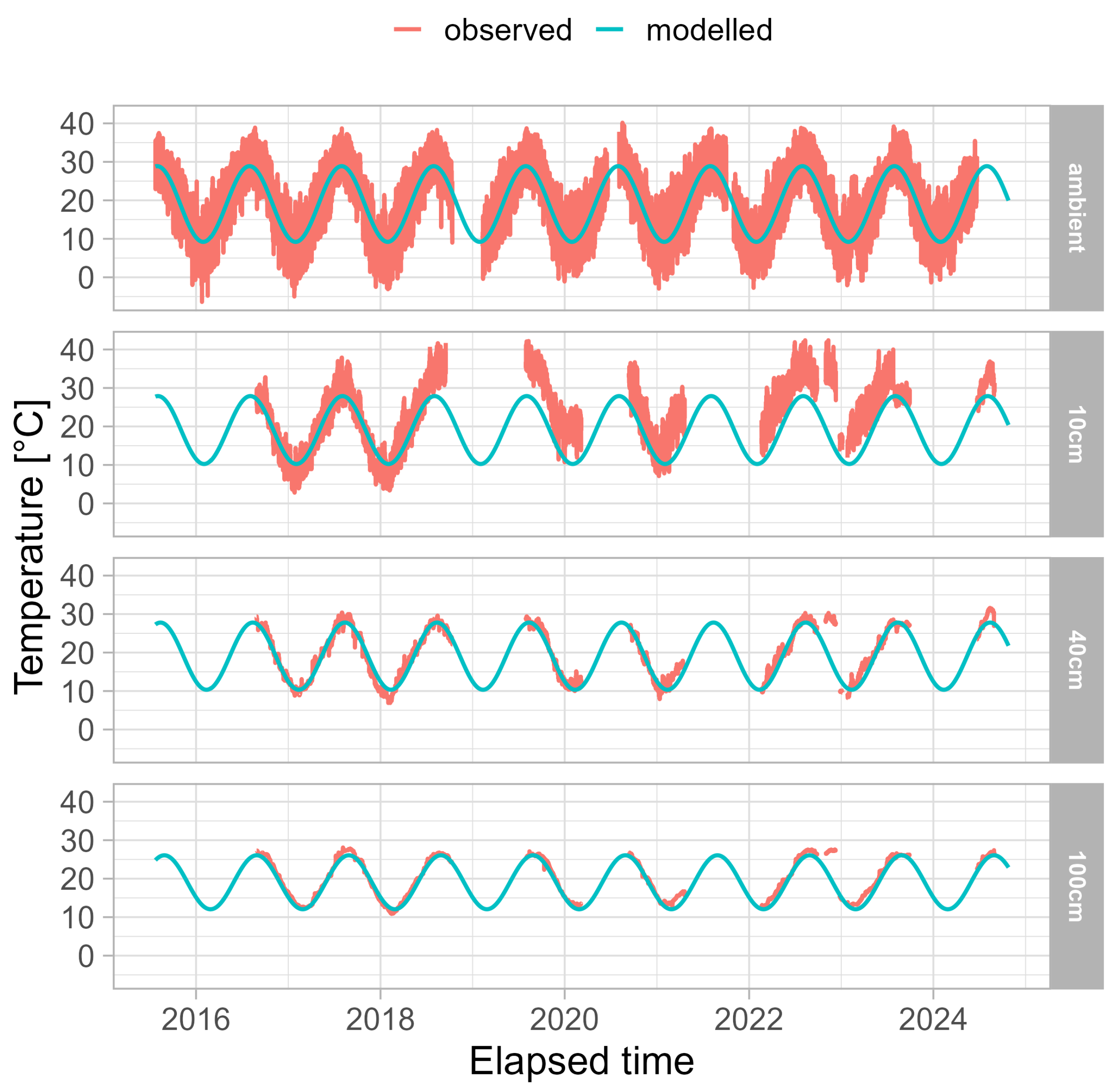

Using the data presented in

Table 2, the modelling procedure was carried out and the results were then compared with the observed data throughout the entire measurement period (see

Figure 7).

At the ambient level, the observed temperatures show significant variability, with clear seasonal oscillations ranging from −6 °C to 40 °C. The model data show comparable seasonal patterns, but with reduced short term variability and a more idealised sinusoidal curve in the range of 10 °C to 30 °C. The model data demonstrate comparable seasonal patterns, yet exhibit decreased short-term fluctuations, thus manifesting a more idealised sinusoidal curve. Moving deeper into the soil profile, at depths of 10 cm, 40 cm, and 100 cm, several key patterns emerge. Initially, at a depth of 10 cm, the model initially underestimates the observed temperatures. While the modelled data closely match the observations during the first years of measurement, they show increasing divergence in subsequent years. This progressive deviation could be attributed to either changing environmental factors or gradual sensor deterioration. Secondly, the amplitude of the temperature fluctuations gradually decreases with depth, suggesting a dampening effect of the soil environment. At a depth of 100 cm, the temperature fluctuations are significantly less pronounced compared to the ambient measurements. Thirdly, a substantial enhancement in the congruence between observed and modelled temperatures and depth is evident. The temporal resolution of the data appears to be quite high, capturing both diurnal and seasonal temperature fluctuations. The seasonal pattern demonstrates consistent annual cycles, with peaks occurring in the summer months and troughs in the winter. This cyclical pattern remains evident at all depths, although its magnitude decreases with increasing depth. This visualisation effectively demonstrates the ability of the soil to buffer temperature fluctuations, with deeper layers showing increased thermal stability and more predictable temperature patterns that are more in line with model expectations.