Submitted:

17 January 2025

Posted:

20 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

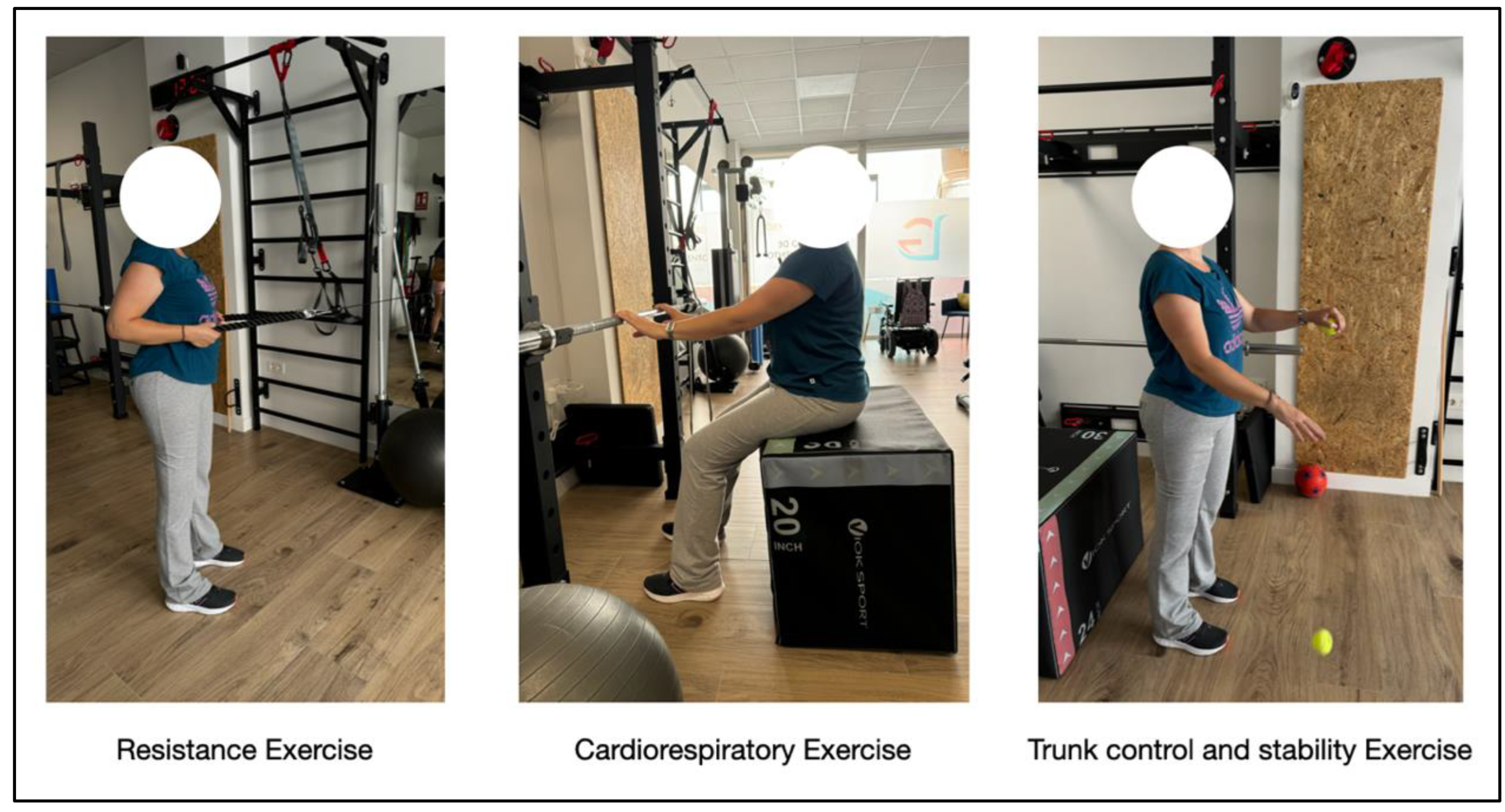

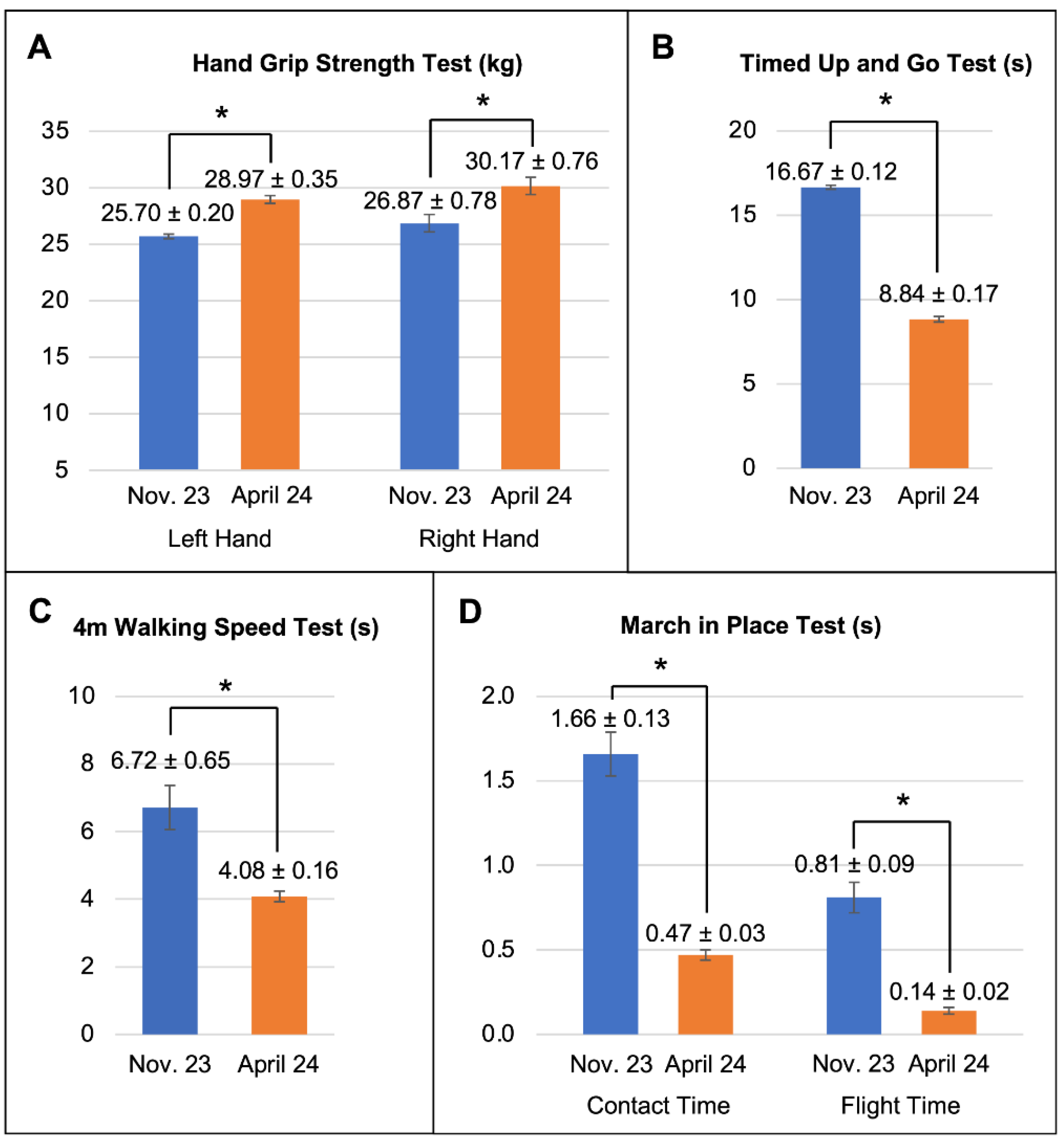

Background/Objectives: Overcoming an oncological process has a significant impact on lower-extremity sarcoma survivors’ quality of life, due to the deterioration in their physical and functional state. This study evaluates the effects of a six-month multicomponent physical training program on mesenchymal chondrosarcoma survivors’ physical function and quality of life Methods: The program was performed done twice weekly and included resistance, cardiorespiratory, trunk control and stability exercises. Results: Functional assessments revealed improvements in hand grip strength, walking speed, balance, and coordination. The Timed Up and Go test showed a 50% reduction in completion time, reflecting better mobility and strength. Additionally, gait speed increased significantly, and balance trials indicated enhanced coordination. Quality of life evaluations using the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire indicated progress in physical health, psychological well-being, and environmental engagement. Conclusions: Taken together, these results emphasize the importance of tailored exercise interventions for sarcoma survivors, particularly those with significant physical impairments. Such programs are vital complements to conventional rehabilitation strategies, fostering physical activity adapted to individual needs. By addressing the multifaceted challenges of survivorship, these interventions enhance functional capacity, reduce disability, and improve overall well-being. Therefore, this case study highlights the program’s effectiveness in managing post-treatment sequelae, opening a pathway to improved physical autonomy and quality of life.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albini, A., C. L. Vecchia, F. Magnoni, O. Garrone, D. Morelli, J. P. Janssens, A. Maskens, G. Rennert, V. Galimberti, and G. Corso. 2024. Physical activity and exercise health benefits: cancer prevention, interception, and survival. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38920329/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, A., T. Martins, and L. Lima. 2021. Patient-reported outcomes in sarcoma: a scoping review. Eur J Oncol Nur 50: 101897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, C., G. Siegel, and S. Smith. 2019. Rehabilitation to improve the function and quality of life of soft tissue and bony sarcoma patients. Patient Related Outcome Measures 10: 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assi, M., M. Ropars, and A. Rébillard. 2017. The Practice of Physical Activity in the Setting of Lower-Extremities Sarcomas: A First Step toward Clinical Optimization. Frontiers in Physiology 8, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coletta, G., and S.M. Phillips. 2023. An elusive consensus definition of sarcopenia impedes research and clinical treatment: A narrative review. Ageing Research Reviews 86: 101883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hollander, D., W. Van der Graaf, M. Fiore, B. Kasper, S. Singer, I. Desar, and H. Husson. 2020. Unravelling the heterogeneity of soft tissue and bone sarcoma patients’ health-related quality of life. ESMO, 5e000914. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, L., C.E. Holm, A. Villadsen, M.S. Sørensen, M.K. Zebis, and M.M. Petersen. 2021. Clinically Important Reductions in Physical Function and Quality of Life in Adults with Tumor Prostheses in the Hip and Knee: A Cross-sectional Study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 479, 10: 2306–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, T., Y. Okita, N. Watanabe, S. Yokota, J. Nakano, and A. Kawai. 2023. Factors associated with physical function in patients after surgery for soft tissue sarcoma in the thigh. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 24, 661: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, S., L. Errington, A. Godfrey, L. Rochester, and C. Gerrand. 2017. Objective clinical measurement of physical functioning after treatment for lower extremity sarcoma. Eur J Surg Oncol, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, S., A. Godfrey, S. Del Pin, L. Rochester, and C. Gerrand. 2020. Are Accelerometer-based Functional Outcome Assessments Feasible and Valid After Treatment for Lower Extremity Sarcomas? Clin Orthop Relat Res 478: 482–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.B., K.K. Ness, and Schadler. 2020. Exercise and Physical Activity in Patients with Osteosarcoma and Survivors. Current Advances in Osteosarcoma, Advances in Experimental, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazendam, A., and et al. 2023. Chondrosarcoma: A Clinical Review. J. Clin. Med. 12: 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jepsen, D.B., K. Robinson, G. Ogliari, M. Montero-Odasso, N. Kamkar, J. Ryg, and et al. 2022. Predicting falls in older adults: an umbrela review of instruments assessing gait, balance, and functional mobility. BMC Geriatrics 22: 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapstad, M.K., I. Naterstad, and B. Bogen. 2023. The association between cognitive impairment, gait speed, and Walk ratio. Front. Aging Neurosci. 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonough, J., J. Eliott, S. Neuhaus, J. Jessica Reid, and P. Butow. 2019. Health-related quality of life, psychosocial functioning, and unmet health needs in patients with sarcoma: a systematic review. Psychooncology 28, 4: 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, J., and et al. 2021. Physical function predicts mortality in patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Supportive Care in Cancer 29: 5623–5634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagi, M., P. Pilavaki, A. Constantinidou, and T. Stylianopoulos. 2022. Immunotherapy in soft tissue and bone sarcoma. Theranostics 12, 14: 6106–6129. Available online: https://www.thno.org/v12p6106.htm. [CrossRef]

- Power, M., A. Harper, and M. Bullinger. 1999. The World Health Organization WHOQOL-100: tests of the universality of Quality of Life in 15 different cultural groups worldwide. Health Psychol 18, 5: 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaisar, R., M.A. Hussain, F. Franzese, A. Karim, F. Ahmad, A. Awad, and et al. 2024. Predictors of the onset of low handgrip strength in Europe: a longitudinal study of 42,183 older adults from 15 countries. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 36: 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, D.C., and K.R. Gundle. 2020. Advances in the Functional Assessment of Patients with Sarcoma. Adv Exp Med Biol 1257: 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skevington, S.M., M.K.A. Lotfy, and WHOQOL Group. 2004. The World Health Organization's WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res 13, 2: 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H., and et al. 2021. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, A., M. Okamoto, M. Kito, Y. Yoshimura, K. Aoki, S. Suzuki, A. Takazawa, Y. Komatsu, H. Ideta, T. Ishida, and J. Takahashi. 2023. Muscle strength and functional recovery for soft-tissue sarcoma of the thigh: a prospective study. Int J Clin Oncol 28, 7: 922–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaishya, R., A. Misra, A. Vaish, N. Ursino, and R. D’Ambrosi. 2024. Hand grip strength as a proposed new vital sign of health: a narrative review of evidences. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition 43: 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kouswijk, H.W., H. G. van Keeken, J. J. W. Ploegmakers, G. H. Seeber, and I. van den Akker-Scheek. 2023. Therapeutic validity and effectiveness of exercise interventions after lower limb-salvage surgery for sarcoma: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 24: 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., and W. Zhou. 2021. Roles and molecular mechanisms of physical exercise in cancer prevention and treatment. Journal of Sport and Health Science 10, 2: 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaja ̨c, A.E., M. Fiedorowicz, A. Tysarowski, S. Kopec, B. Szostakowski, M.J. Spałek, and et al. 2021. Chondrosarcoma-from Molecular Pathology to Novel Therapies. Cancers 13: 2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subject level | Program objectives | Spatial and material resources | Assessment processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial: untrained with little experience in regular physical exercise programs. | Functionality in daily living activities and quality of life. | Training centre equipment (bench/box, rack, dumbbells, pulleys, elastic band, medicine balls, bicycle, arm ergometer...). | 1.- Physical condition parameters (functional capacity): A) Hand grip strength test. B) Timed Up and Go (TUG) Test. C) 4m walking speed test. D) March in place test (Optojump system). 2.- Quality of life: A) WHOQOL-BREF. |

| Mesocycles | M. 1 | M. 2 | M. 3 | M. 4 | M. 5 | M. 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weekly frequency | 2 d/w | 2 d/w | 2 d/w | 2 d/w | 2 d/w | 2 d/w |

| Resistance training units | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Cardiorespiratory training units | 0 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| Trunk control and stability training units | 8 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Frequency | Volume | Intensity | Recovery | Methodology | Exercises |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 d/w | -Training unit duration: 25-30´ -Exercises: 5. -Series: 2. -Repetitions: 6. |

Low effort character: 6 (12). | 2´inter-series. | Vertical progression. | - Assisted squat from box. - Horizontal pulley row. - Seated hip adduction with ball. - Inclined push-ups on bar. - Vertical traction with elastic band. |

| Frequency | Volume | Intensity | Recovery | Methodology | Exercises |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 d/w | -Training unit duration: 10´ -Exercises: 2. -Series: 1. -Repetitions: 5 (30” each). |

-50%-60%HRR. -RPE: 2-3 (Modified Borg) |

1´inter-repetitions. Ratio: 1:2. |

Fractionation, Interval. | Standing arm ergometer. |

| Frequency | Volume | Intensity | Recovery | Methodology | Exercises |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 d/w | -Training unit duration: 12´ -Exercises: 3. -Series: 2. -Repetitions: 6-10 |

Challenge/disruption for the trunk structures. | 2´inter-series. | Vertical progression. | -Alternately bounce 2 tennis balls with eyes closed while standing. -Apply manual resistance to hands in multiple directions while sitting. -Standing with horizontal shoulder adduction, rotate the cervical spine from one side to the other when receiving an auditory stimulus (clap). |

| Dimensions | November 2023 (Pre-Intervention) |

April 2024 (Post-Intervention) |

|---|---|---|

| Physical health | 10.3/20 | 10.9/20 |

| Psychological health | 12/20 | 13.3/20 |

| Social relations | 14.7/20 | 14.7/20 |

| Environment | 15.5/20 | 16/20 |

| General perception of quality of life | 4/5 | 4/5 |

| General perception of health | 3/5 | 4/5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).