Submitted:

16 January 2025

Posted:

16 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

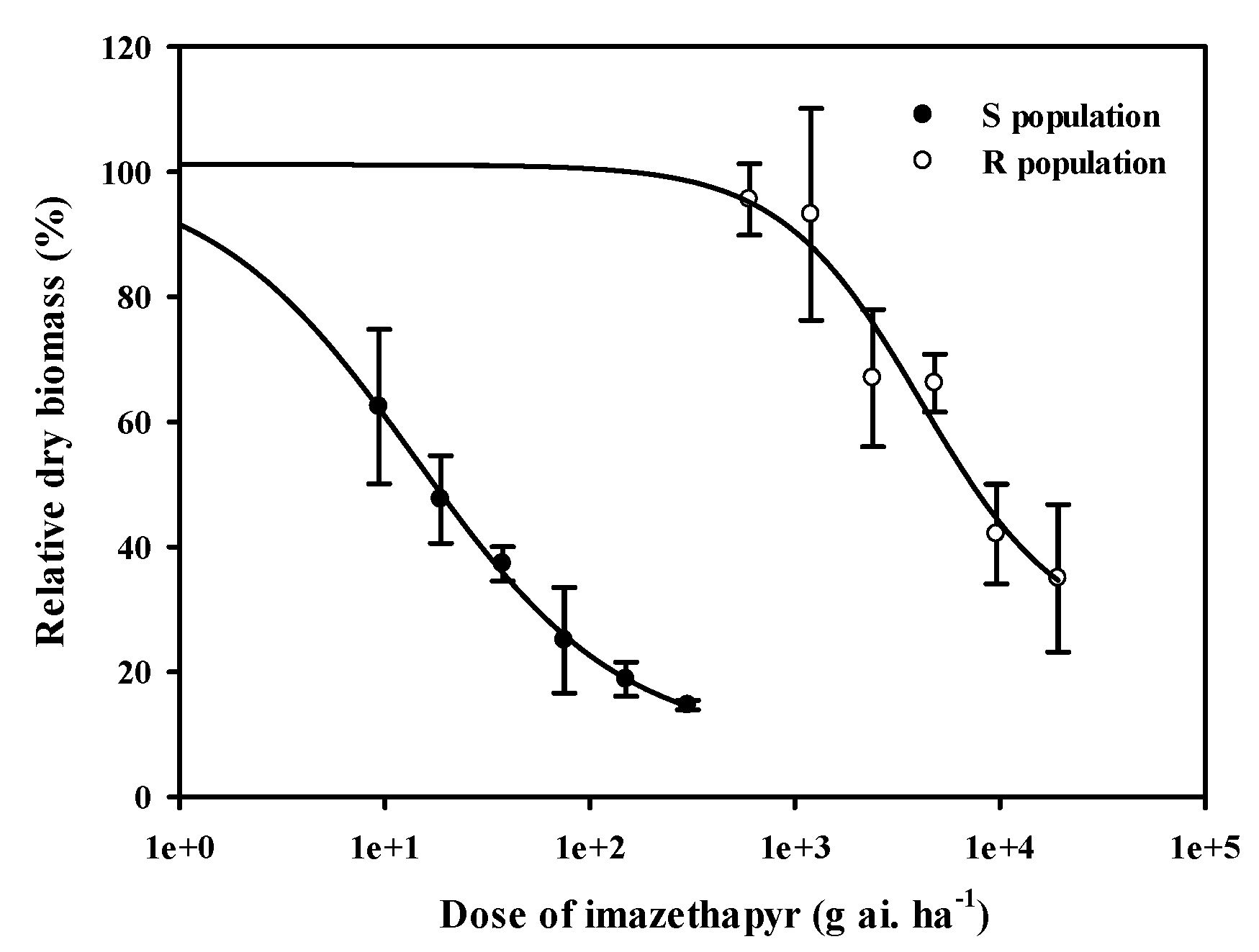

2.1. Response of A. palmeri to imazethapyr

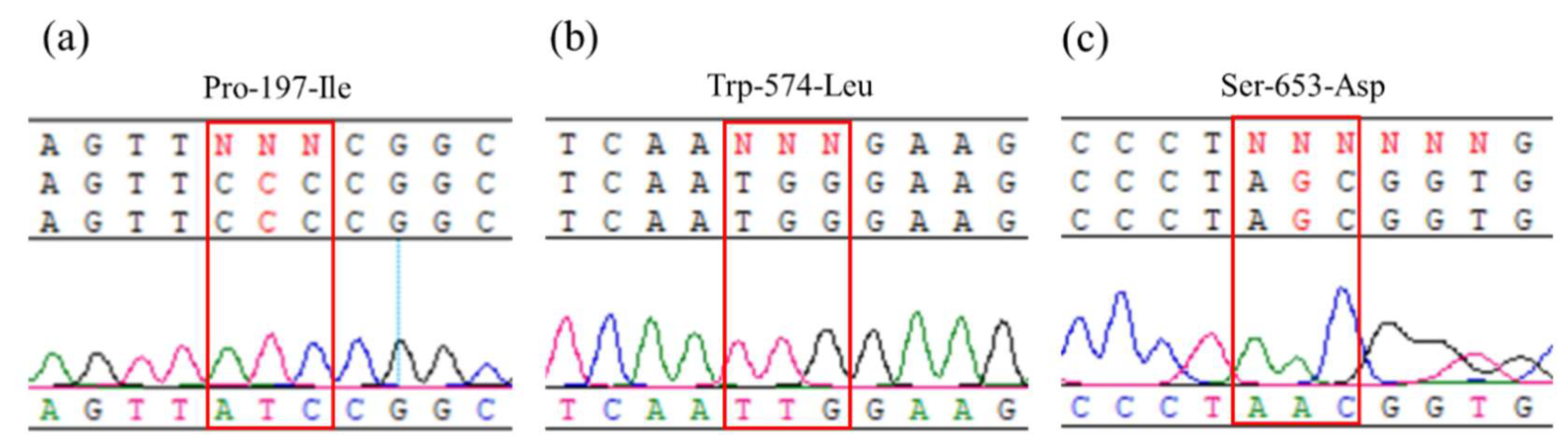

2.2. Sequencing of ALS gene

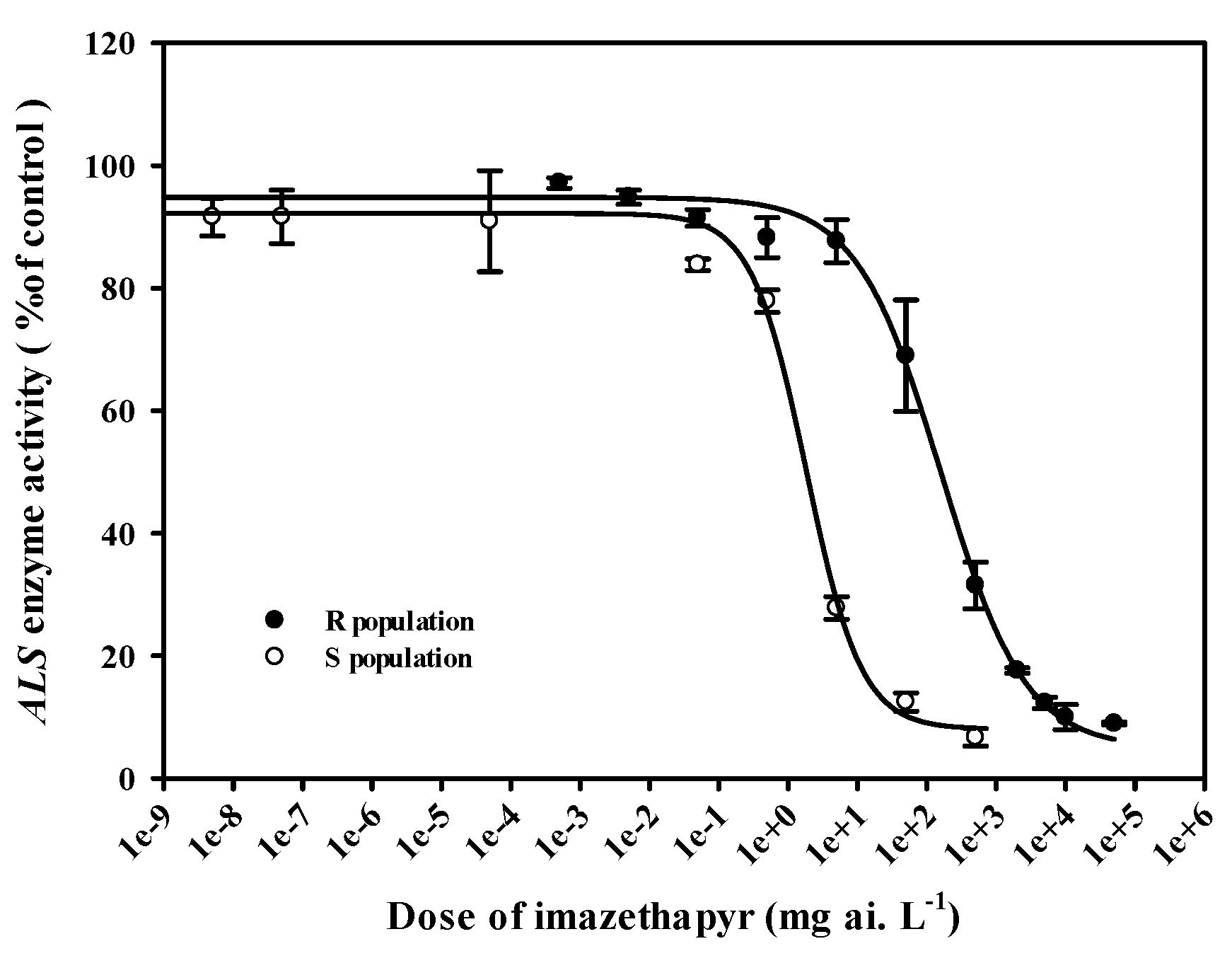

2.3. In vitro ALS assay

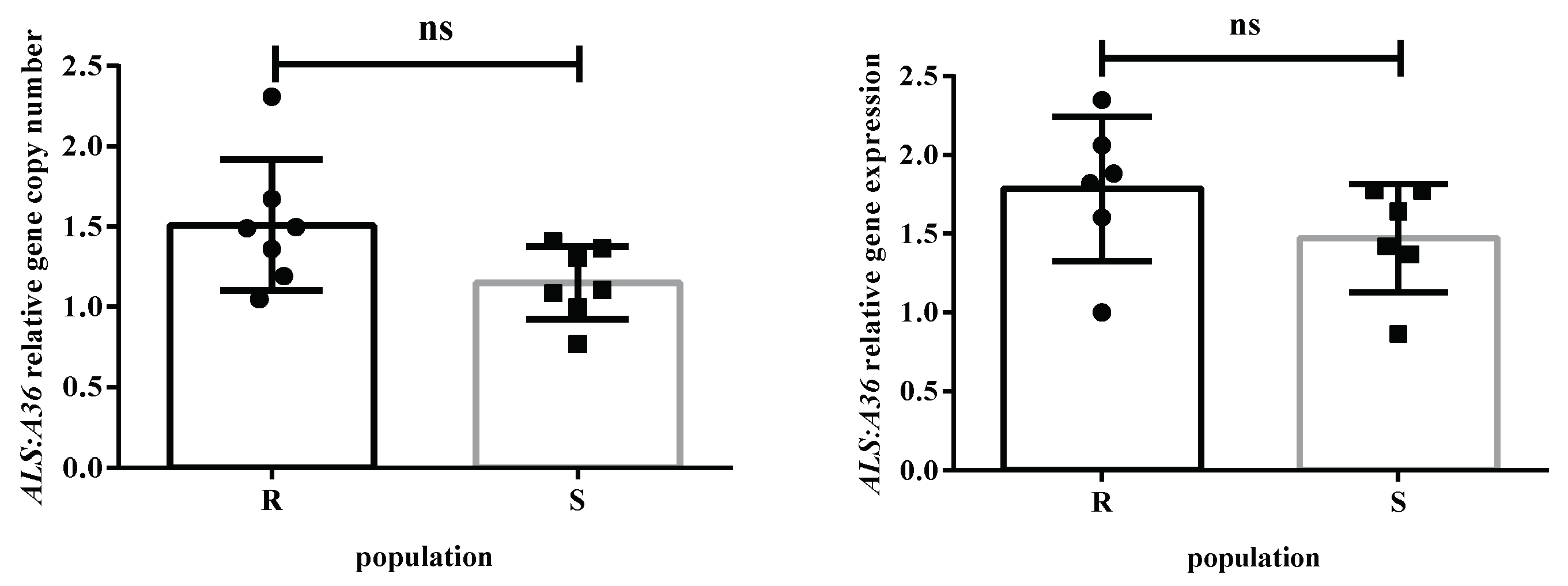

2.4. ALS gene copy number and ALS gene expression

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant materials and growth conditions

4.2. Dose-response experiments

4.3. ALS gene sequencing and resistance mutation genotyping

4.4. In vitro ALS assay

4.5. ALS gene copy numbers and ALS gene expression

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ward, S.M.; Webster, T.M.; Steckel, L.E. Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus. palmeri): a review. Weed Technol. 2013, 27, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingaman, T.E.; Oliver, L.R. Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus. palmeri) interference in soybeans (Glycine max). Weed Sci. 1994, 42, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, M.W.; Murray, D.S.; Verhalen, L.M. Full-season Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus. palmeri) interference with cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). Weed Sci. 1999, 47, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.T.; Baker, R.V.; Steele, G.L. Palmer Amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) Impacts on Yield, Harvesting, and Ginning in Dryland Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). Weed Technol. 2000, 14, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massinga, R.A.; Currie, R.S.; Horak, M.J.; Boyer, J. Interference of Palmer amaranth in corn. Weed Sci. 2001, 49, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massinga, R.A.; Currie, R.S. Impact of Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus. palmeri) on corn (Zea mays) grain yield and yield and quality of forage. Weed Technol. 2002, 16, 532–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Y. Amaranthus. palmeri S Watson, A newly naturalized species in China. Botanical bulletin 2003, 20, 734–735. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Che, J.D. Invasive weed- Amaranthus. palmeri S Watson. Weed Science 2008, 26, 58–60. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mo, X.Q.; Meng, W.Q.; Li, H.Y. New distribution records of three species of exotic plants in Tianjin: Amaranthus palmeri. Ipomoea lacunosa and Aster subulatu. Journal of Tianjin Normal University (Natural Science Edition) 2017, 37, 36–38. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.G.; Cao, J.J.; Wang, R. Risk assessment based on analytic hierarchy process of an invasive alien weed,Amaranthus. palmeri,in northern Henan Province. Plant Quarantine 2021, 35, 60–65. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M. Study on ecological effects of two amaranth invasive plants on the functional traits of native plants; Nankai university: Tianjin, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chaleff, R.S.; Mauvais, C.J. Acetolactate synthase is the site of action of two sulfonylurea herbicides in higher plants. Science. 1984, 224, 1443–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaner, D.L.; Anderson, P.C.; Stidham, M.A. Imidazolinones: potential inhibitors of acetohydroxyacid synthase. Plant Physiol. 1984, 76, 545–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerwick, B.C.; Subramanian, M.V.; Loney-Gallant, V.I.; Chandler, D.P. Mechanism of action of the 1, 2, 4-triazolo [1,5-a] pyrimidines. J. Pestic. Sci. 1990, 29, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stidham, M.A. Herbicides that inhibit acetohydroxyacid synthase. Weed Sci. 1991, 39, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santel, H.J.; Bowden, B.A.; Sorensen, V.M.; Mueller, K.H.; Reynolds, J. Flucarbazone-sodium: a new herbicide for grass control in wheat. Weed Science Society of America Abstract. 1999, 39, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Horak, M.; Peterson, D. Biotypes of Palmer Amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) and common waterhemp (Amaranthus rudis) are resistant to imazethapyr and thifensulfuron. Weed Technol. 1995, 9, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heap, I. The international survey of herbicide resistant weeds. Available online: https://www.weedscience.org/ (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Yu, Q.; Powles, S. Resistance to AHAS inhibitor herbicides: current understanding. Pest Manag Sci. 2014, 70, 1340–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, V.; Salas-Perez, R.A.; Bagavathiannan, M.V.; Lawton-Rauh, A.; Roma-Burgos, N. Target-site mutation accumulation among ALS inhibitor-resistant Palmer amaranth. Pest Manag Sci. 2019, 75, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohrt, J.R.; Sprague, C.L.; Swathi, N.; Douches, D. Confirmation of a three-way (glyphosate, als, and atrazine) herbicide-resistant population of Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus. palmeri) in Michigan. Weed Sci. 2017, 65, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, S.; Varanasi, V.K.; Nakka, S.; Bhowmik, P.C.; Thompson, C.R.; Peterson, D.E.; Currie, R.S.; Jugulam, M. Evolution of target and non-target based multiple herbicide resistance in a single Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) population from Kansas. Weed Technol. 2020, 34, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, D.J.; Jordan, D.L.; Roma-Burgos, N.; Jennings, K.M.; Leon, R.G.; Vann, M.C.; Everman, W.J.; Cahoon, C.W. Susceptibility of Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) to herbicides in accessions collected from the North Carolina Coastal Plain. Weed Sci. 2020, 68, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manicardi, A.; Scarabel, L.; Llenes, J.M.; Montull, J.M.; Osuna, M.D.; Farré, J.T.; Milani, A. Genetic basis and origin of resistance to acetolactate synthase inhibitors in Amaranthus palmeri from Spain and Italy. Pest Manag Sci. 2023, 79, 4886–4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foes, M.J.; Tranel, P.J.; Wax, L.M.; Stoller, E.W. A biotype of common waterhemp (Amaranthus. rudis) resistant to triazine and ALS herbicides. Weed Sci. 1998, 5, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larran, A.S.; Palmieri, V.E.; Perotti, V.E.; Lieber, L.; Tuesca, D.; Permingeat, H.R. Target-site resistance to acetolactate synthase (ALS)-inhibiting herbicides in from Argentina. Pest Manag Sci. 2017, 73, 2578–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Küpper, A.; Borgato, E.A.; Patterson, E.L.; Gonçalves Netto, A.; Nicolai, M.; Carvalho, S.J.P.d.; Nissen, S.J.; Gaines, T.A.; Christoffoleti, P.J. Multiple Resistance to Glyphosate and Acetolactate Synthase Inhibitors in Palmer Amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) Identified in Brazil. Weed Sci. 2017, 65, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torra, J.; Royo-Esnal, A.; Romano, Y.; Osuna, M.D.; León, R.G.; Recasens, J. Amaranthus palmeri a New Invasive Weed in Spain with Herbicide Resistant Biotypes. Agronomy. 2020, 10, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakka, S.; Godar, A.S.; Wanti, P.S.; Thompson, C.R.; Peterson, D.E.; Roelofs, J.; Jugulam, M. Physiological and molecular characterization of hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase (HPPD)-inhibitor resistance in Palmer Amaranth (Amaranthus. palmeri S. Wats) . Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.C.; Huang, H.J.; Zhang, C.X.; Wei, S.H.; Huang, Z. F.; Chen, J. Y.; Wang, X. Mutations and amplification of EPSPS gene confer resistance to glyphosate in goosegrass (Eleusine indica). Planta. 2015, 242, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaines, T.A.; Zhang, W.L.; Wang, D.F.; Bukun, B.; Chisholm, S.T.; Shaner, D.L.; Westra, P. Gene amplification confers glyphosate resistance in Amaranthus palmeri. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010, 107, 1029–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhari, S.; Jordan, D.; York, A.; Jennings, K.M.; Cahoon, C.W.; Inman, A.; Chandi, M.D. Biology and management of glyphosate-resistant and glyphosate-susceptible Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus. palmeri) phenotypes from a segregating population. Weed Sci. 2007, 65, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molin, W.T.; Nandula, V.K.; Wright, A.A.; Bond, J.A. Transfer and expression of ALS inhibitor resistance from Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus. palmeri) to an A. spinosus × A. palmeri hybrid. Weed Sci. 2016, 64, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibony, M.; Rubin, B. Molecular basis for multiple resistance to acetolactate synthase-inhibiting herbicides and atrazine in Amaranthus blitoides (prostrate pigweed). Planta. 2003, 216, 1022–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whaley, C.A.; Wilson, H.P.; Westwood, J.H. ALS resistance in several smooth pigweed (Amaranthus hybridus) biotypes. Weed Sci. 2006, 54, 828–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprague, C.L.; Stoller, E.W.; Wax, L.M.; Horak, M.J. Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus. palmeri) and common water hemp (Amaranthus rudis) resistance to selected ALS-inhibiting herbicides. Weed Sci. 1997, 45, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Mccullough, P.E.; Mcelroy, J.S.; Jespersen, D.; Shilling, D.G. Gene expression and target-site mutations are associated with resistance to ALS inhibitors in annual sedge (Cyperus compressus) biotypes from Georgia. Weed Sci. 2020, 68, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Burgos, N.R.; Singh, V.; Alcober, E.A.L.; Salaa-Perez, R.; Shivrain, V. Differential response of Arkansas Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus. palmeri) to glyphosate and mesotrione. Weed Technol 2018, 32, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, G.M.; Hamill, A.S.; Tardif, F.J. ALS inhibitor resistance in populations of Powell amaranth and redroot pigweed. Weed Sci. 2001, 49, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Zuniga, R.; Morrison, D. Update on the environmental and economic costs associated with alien-invasive species in the United States. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 52, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steckel, L.E. The dioecious Amaranthus spp.: here to stay. Weed Technol. 2007, 21, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Liu, R.; Boyer, G.; Stahlman, P.W. Confirmation of 2,4-D resistance and identification of multiple resistance in a Kansas Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus. palmeri) population. Pest Manag Sci. 2019, 75, 2925–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Shane Friesen, L.J.; Zhang, X.Q.; Powles, S.B. Tolerance to acetolactate synthase and acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase inhibiting herbicides in Vulpia bromoides is conferred by two co-existing resistance mechanisms. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2004, 78, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, V.; Lawton-Rauh, A.; Bagavathiannan, M.V.; Roma-Burgos, N. EPSPS gene amplification primarily confers glyphosate resistance among Arkansas Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus. palmeri) populations. Weed Sci. 2018, 66, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene mutation types | Number of individuALS |

| Pro-197-lle | 19 |

| Trp-574-Leu | 13 |

| Ser-653-Asp | 20 |

| Pro-197-lle+ Trp-574-Leu | 11 |

| Pro-197-lle+ Ser-653-Asp | 9 |

| Trp-574-Leu+ Ser-653-Asp | 25 |

| Pro-197-lle+ Trp-574-Leu+ Ser-653-Asp | 2 |

| Mutation not detected | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).