1. Introduction

Causal discovery using methods such as FCI [

11] or IC [

12], as well as the many variants and extensions of these classic methods developed over the past several decades [

2,

3,

13,

14,

15], involves searching super-exponential spaces as the number of causal DAGs grows extremely large in the number of variables. For

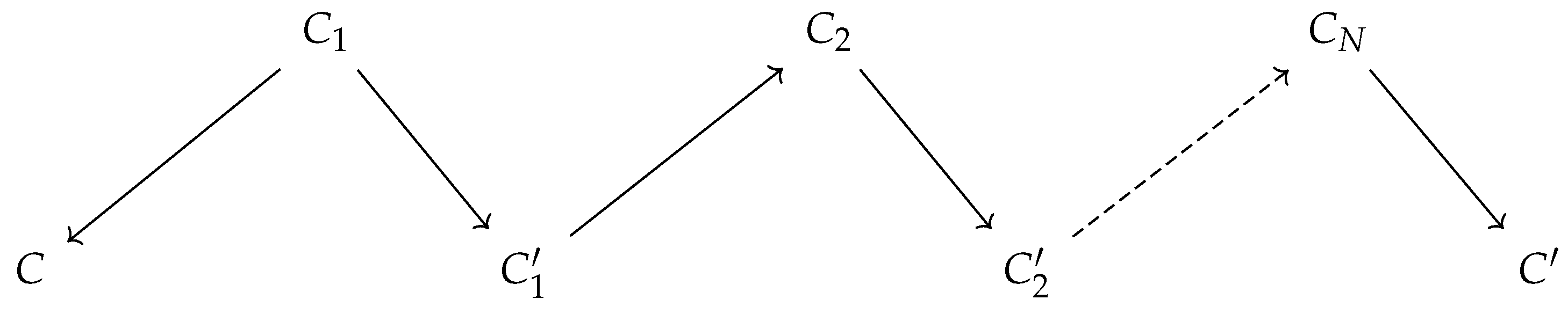

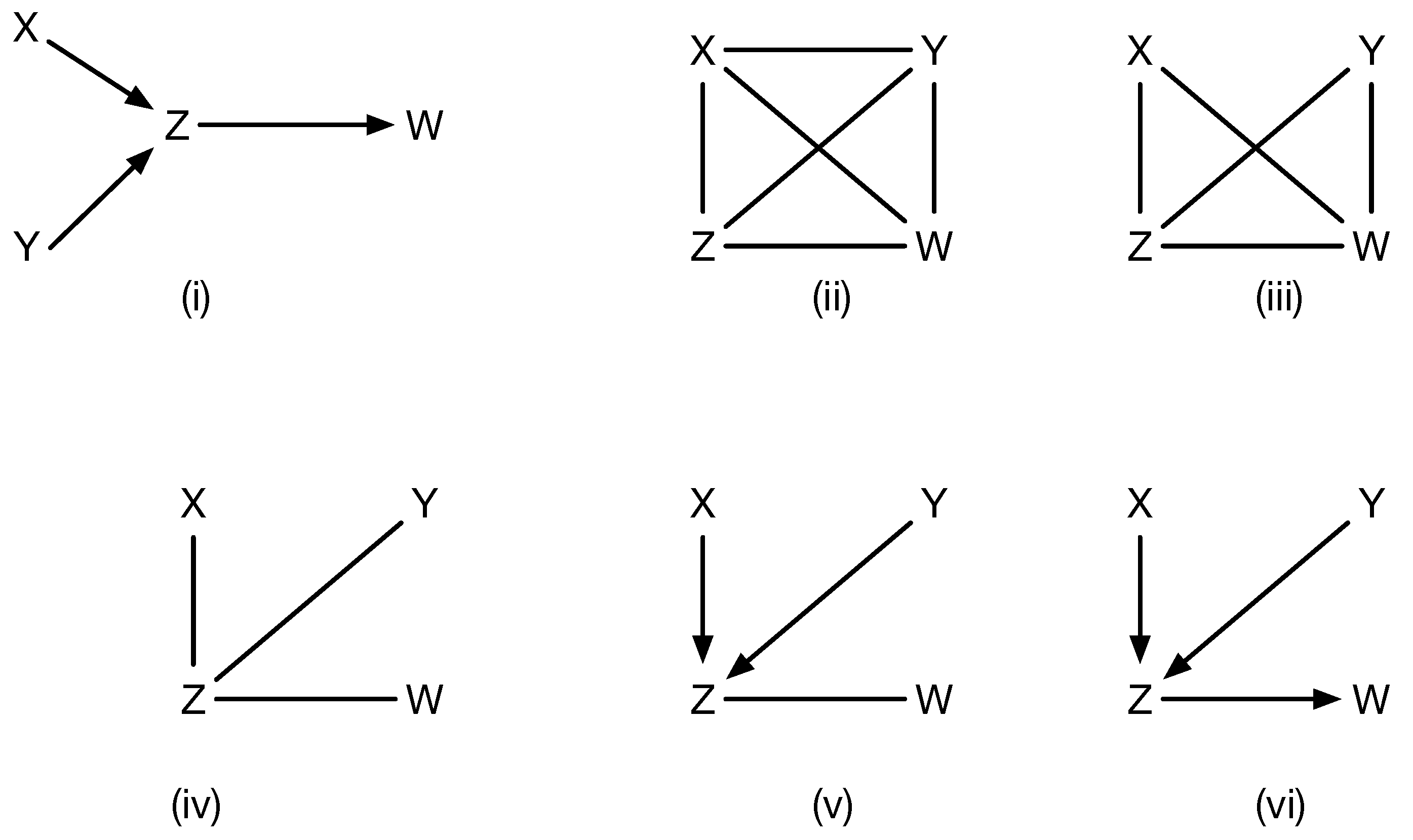

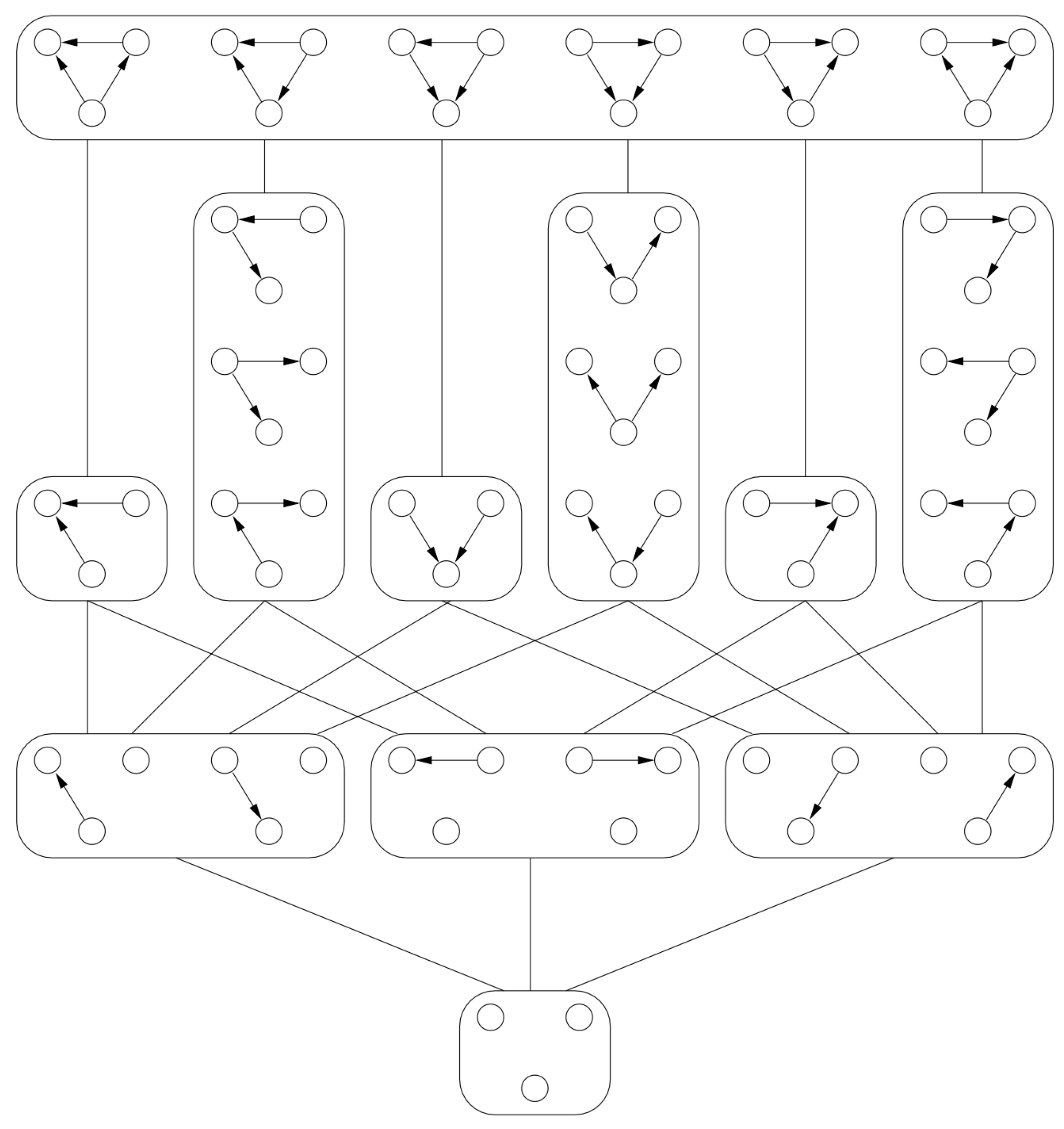

variables, there are 11 equivalence classes of DAG models (see

Figure 1). There are approximately

DAG models on just 11 labeled variables.

1 To make matters worse, DAG models capture only a tiny portion of the space because for

, there are

conditional independence structures, but DAG models capture only roughly 1% of this space! More powerful models like integer-valued multisets (imsets) [

16] that model conditional independences by mapping the powerset of all variables into integers grow even larger still (of the order of

). Representing this space efficiently with categorical representations like affine CDU categories [

8] or Markov categories [

17] will require defining equivalence classes over string diagrams to combat this curse of dimensionality. This challenge motivates the need for a deeper categorical understanding of the equivalence classes of observationally indistinguishable models [

1]. While allowing for arbitrary interventions on causal models enables accurate identification [

14,

15], such interventions are rarely practical in the real world. Insights such as the Meek-Chickering theorem [

2,

18,

19] allow a deeper understanding of connected paths among equivalent causal DAG models, which we propose to study using a homotopy framework in this paper.

Causal discovery poses some unique challenges for categorical modeling.

Figure 1 illustrates the structure of causal equivalence classes on causal DAGs with 3 variables represented as essential graphs [

20] or `patterns" [

11] or PDAGs [

2], which combine undirected edges that could be oriented in either direction with directed edges. As Verma and Pearl [

1] noted several decades ago, two DAGs are equivalent if their underlying skeletons (undirected graph structure ignoring edge directions) and V-structures

are the same. The DAG at the bottom satisfies no conditional independences, and the DAG on the top satisfies all conditional independences. Our goal here is to build on the ideas in [

2] on connected paths between observationally equivalent models, in particular the Meek-Chickering theorem, which we want to generalize to the categorical setting. As Chickering [

2] notes, this theorem, which was originally a conjecture by Meek, implies that there exists a sparse search space, where each candidate model is connected to a small fraction of the total space, given a generative distribution that has a perfect map in a DAG defined over the observables. This property leads to the development of a greedy search algorithm that in the limit of training data can identify the correct model.

In practice, existing causal discovery algorithms, such as PC [

11] or IC [

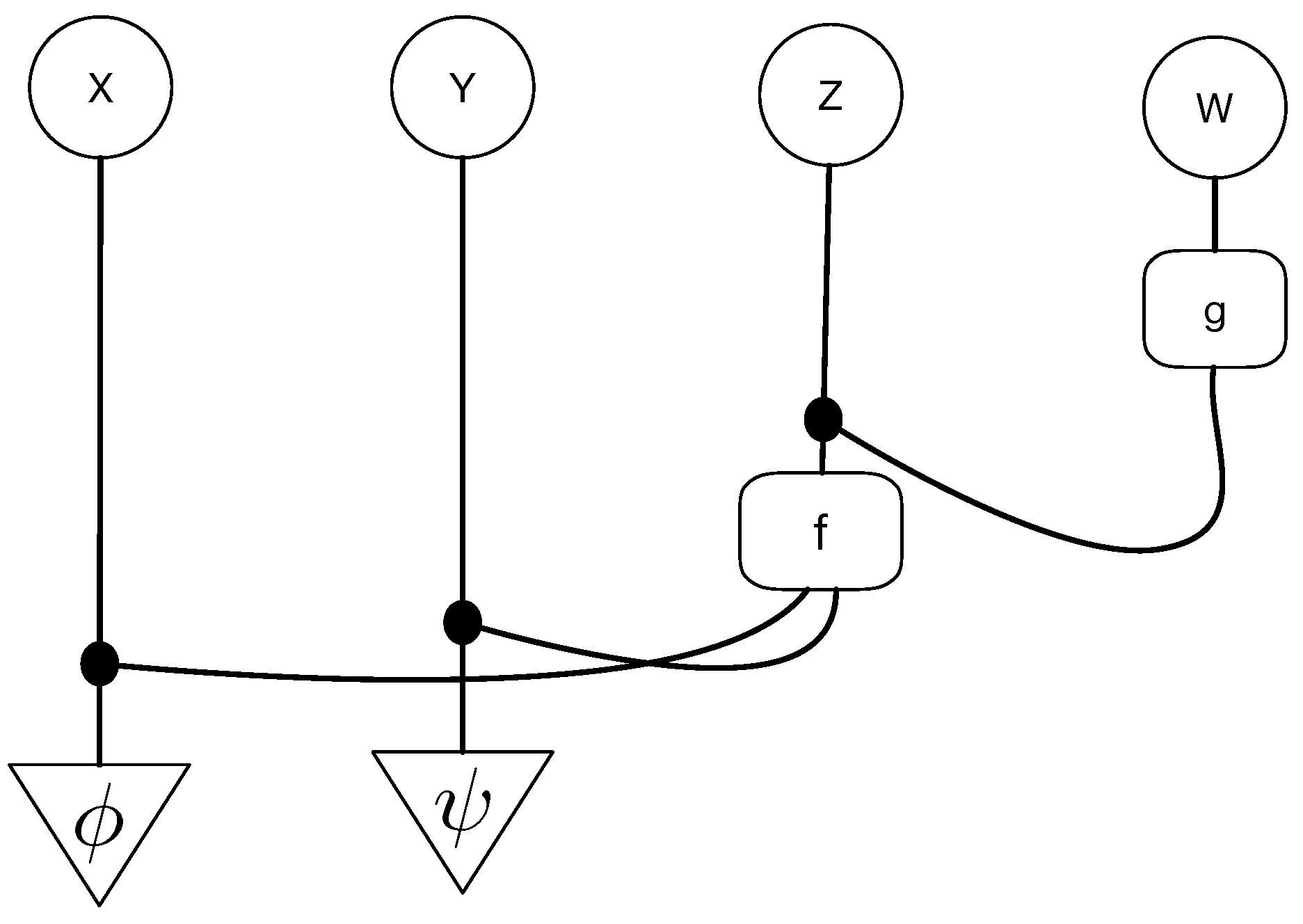

21] or their many extensions and variants combine both directional and non-directional encoding of causal models. Specifically, a common assumption, such as in PC, is that given an unknown true causal model (shown in

Figure 2 by panel (i)), the initial causal model (shown as (ii) in

Figure 2) is an undirected graph connecting all variables to each other, which satisfies no conditional independences, and is progressively refined (panels (ii)-(vi) in

Figure 2) based on conditional independence data and using edge orientation and propagation rules, such as the Meek rules [

18]. For example, the initial stage is to simply check all marginal independences, and given that

, that eliminates the undirected edge between

X and

Y. However, each undirected edge between two vertices, say

A and

B, that needs to eliminated due to conditional independence must be checked for increasingly large subsets

, and while methods like FCI and later enhancements [

14,

15] incorporate rather sophisticated methods to prune the space, this process remains computationally expensive, and its practicality remains in question as in the real world, interventions on arbitrary separating sets [

14] may be infeasible. While remarkable progress has been made over the past few decades (see [

15] for a state of the art method), it still can be prohibitive, and does not always end up with the right model. Edges that remain undirected are interpreted to indicate latent confounders.

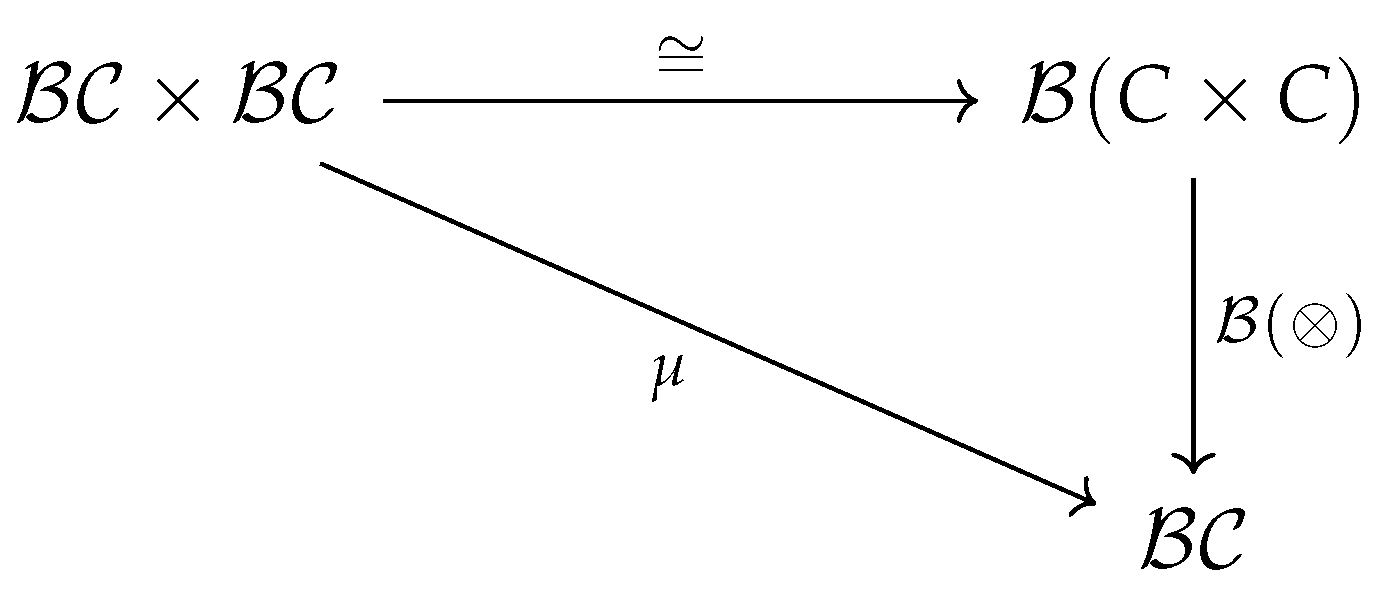

To generalize the Meek-Chickering theorem to the categorical setting, some challenges need to be addressed.

Figure 3 shows a string diagram representation of the causal model in

Figure 2. Such string diagrams are used in affine CD [

8] and Markov categories [

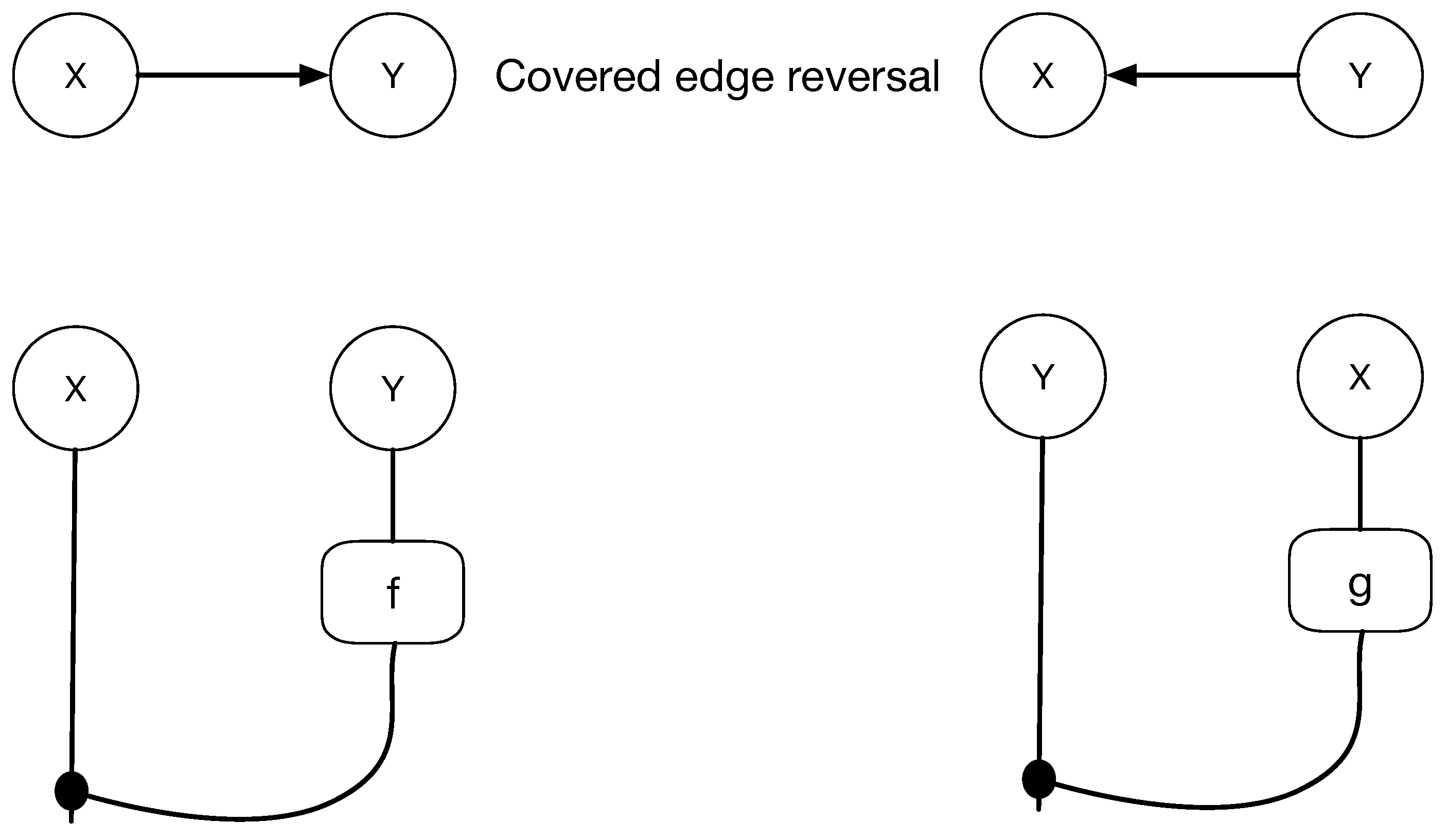

17]. However, as

Figure 4 shows, Meek-Chickering equivalence implies that covered edges can be reversed while maintaining DAG equivalence, which imposes an equivalence structure on string diagrams as shown. As the number of causal models grows exponentially, so does the number of string diagrams, and to develop deeper insight into the underlying topological structure of causal equivalences, we introduce a coalgebraic theory of causal inference based on a categorical structure we call cPROP, defined as a functor category from a PROP [

22] to a symmetric monoidal category [

23]. We build on the work of Fox [

4] who studied functor categories mapping PROPs to symmetric monoidal categories in his PhD dissertation in 1976. Crucially, Fox [

4] studied a particular functor category from a coalgebraic PROP to symmetric monoidal categories that defined a right adjoint from the category

MON of all symmetric monoidal categories to

CART, the category of all Cartesian categories.

2. In this sense, cPROPs are formally an algebraic theory in the sense of Lawvere [

5].

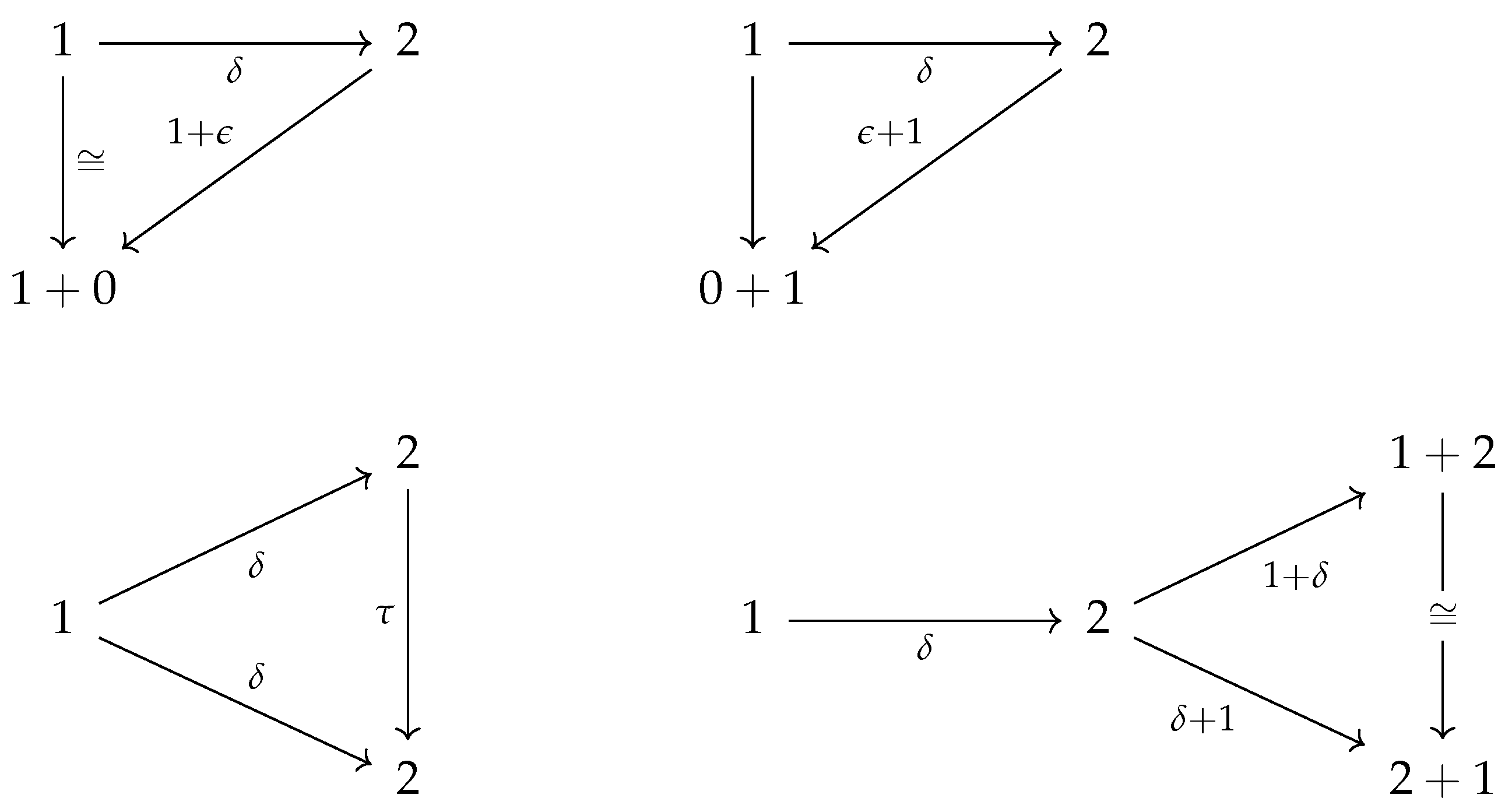

Objects in a cPROP are functors mapping a PROP

P – a symmetric monoidal category over natural numbers – to a symmetric monoidal category

. The structure PROP (for Products and Permutations) was originally introduced by Maclane [

22], and it has seen widespread use in many areas such as modeling connectivity in networks [

25,

26]. A trivial example of a PROP is the free monoidal category

over the category

1, whose objects can be interpreted as the natural numbers, the unit object is 0, and the tensor product is addition. More generally, a PROP

P is a small monoidal category with a strict monoidal functor

that is a bijection on objects. A cPROP is a functor category

, where C is a symmetric monoidal category, where in addition there is usually some constraints placed on the specific PROP

P.

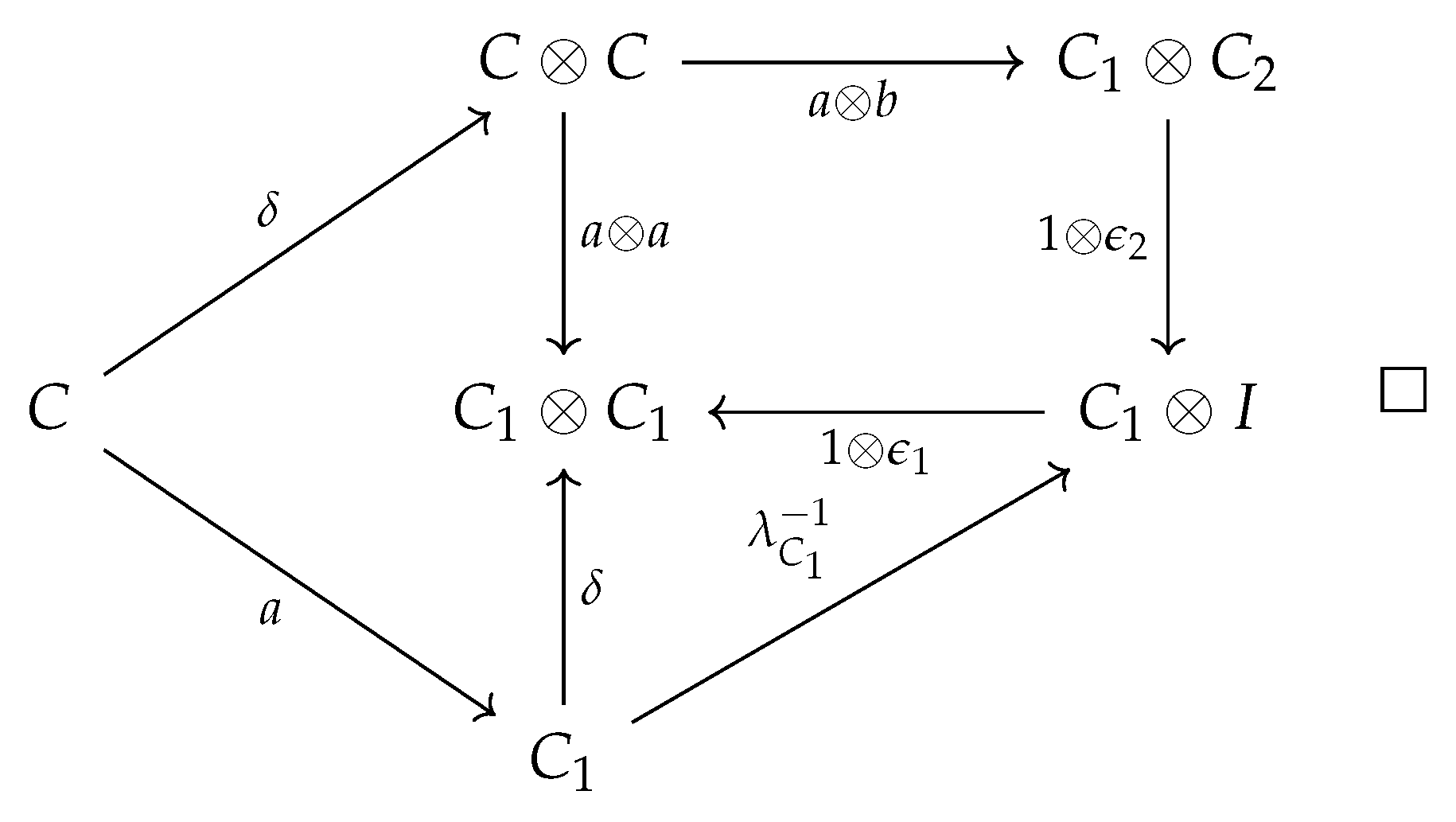

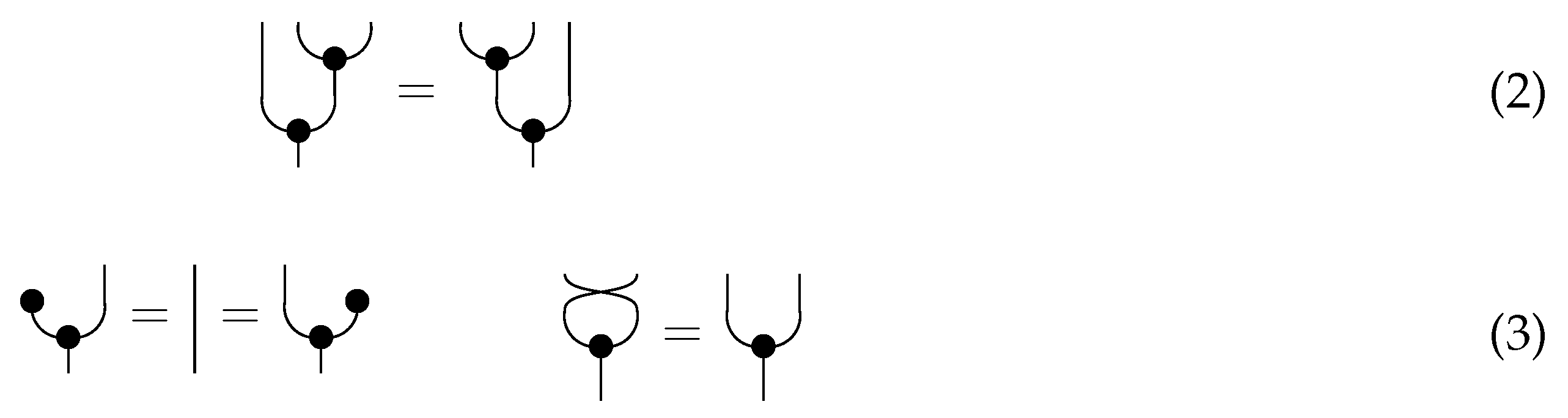

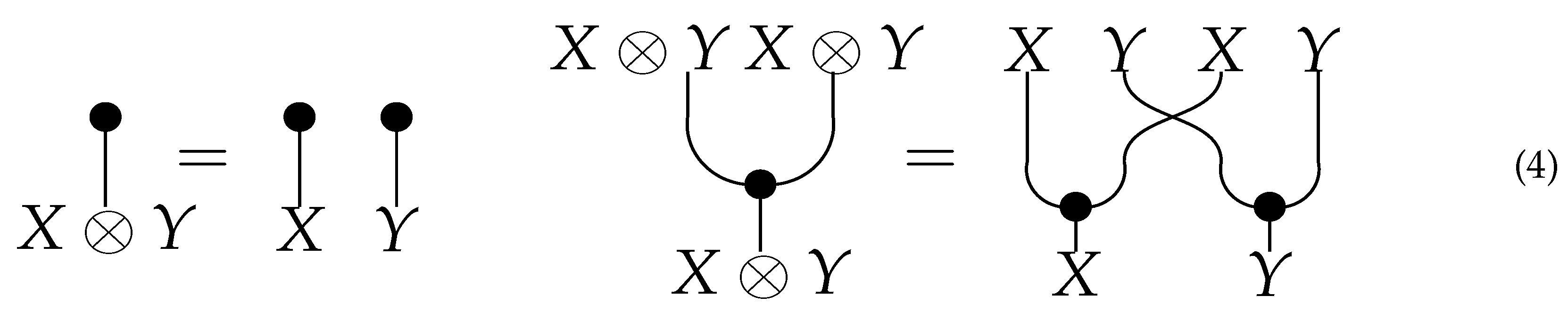

As a simple example, we consider cPROPs where the PROP

P is generated by a

coalgebraic structure defined by the maps

and

satisfying a set of commutative diagrams. Such cPROPs are closely related to symmetric monoidal category structures used in previous work on categorical models of causality, probability and statistics [

7,

17,

27,

28,

29]. In particular, Markov categories [

6,

17] and affine CDU (“copy-delete-uniform") categories used to model causal inference include a comonoidal “copy delete" structure correspond to such a cPROP, which we note is distinctive in that “delete" has a uniform structure, but “copy" does not, leading to a semi-Cartesian category.

In our previous work on universal causality [

29], we proposed the use of simplicial sets, which both provide a way to encode directional and non-directional edges, as well as forms the basis for topological realization for cPROPs and plays a central role in higher-order

∞-categories [

30,

31]. We study the classifying spaces [

9] of cPROPs in this paper, showing that they provide deeper insight into the connections between different cPROP categories that correspond to Markov categories, such as

FinStoch [

6].

In particular, we build on longstanding ideas in abstract homotopy theory on modeling equivalence classes of objects in a category [

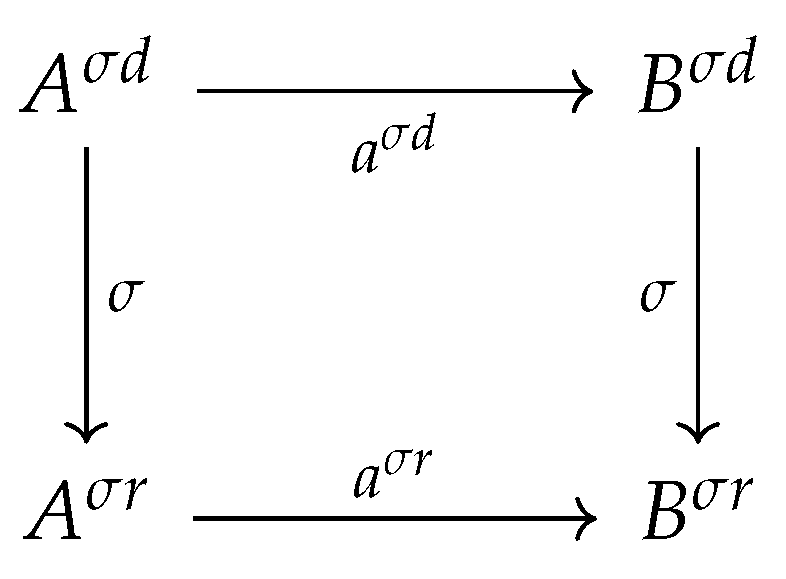

32] by mapping a category into a topological space, where (weak) equivalences can be modeled in terms of topological structures, such as homotopies. To make this more concrete, Jacobs et al. [

8] modeled a Bayesian network as a CDU functor

between two affine CDU or Markov categories, one specifying the graph structure of the model, and the other modeling its semantics as an object in the category of finite stochastic processes

FinStoch. A CDU functor is a special type of cPROP functor. Two Bayesian networks modeled as such cPROP functors that are observationally equivalent – such as

and

since the edge

is a covered edge that can be reversed – induce a natural transformation

. Using the associated classifying spaces

and

, the natural transformation induces a homotopy between

and

.

The idea of associating a topological space with a category goes back to Grothendieck, but was popularized by Segal [

9]: map a category

to a sequence of sets (or objects)

, where the

k-simplex

represents composable morphisms of length

k. A standard topological realization proposed by Milnor [

33] constructs a topological CW-complex out of simplicial sets. Segal called such a construction the classifying space

of category

. Our paper can be seen as an initial step in building a higher algebraic K-theory [

10] for causal inference, using as a concrete example the study of classifying spaces of cPROPs. A 0-simplex in a simplicial cPROP would be defined by its objects

, which map to 0-cells in its classifying space. An example 2-simplex in a cPROP, such as

maps to a 2 cell or simplicial triangle.

We build on the insight underlying Fox’s dissertation on universal coalgebras [

4], which shows that the subcategory of coalgebraic objects in a monoidal category forms its Cartesian closure. The adjoint functor theorems show that cofree algebras – right adjoints to forgetful functors – exist in such cases. In particular, Fox’s theorem implies that cPROPs that come with a type of “uniform copy-delete" structure [

34] are Cartesian symmetric monoidal categories, where the tensor product

becomes a Cartesian product operation through natural transformations, rather than the standard universal property. We note that Markov categories are semi-Cartesian because the comonoidal

structure is not uniform, but only

is. however, they contain a subcategory of deterministic morphisms that induce a Cartesian category using the uniform copy delete structure. It is worth noting here that Pearl [

12] has long advocated causality as being being intrinsically deterministic in his structural causal models (SCMs), where the role of probabilities is reflected in the uncertainty associated with exogenous variables that cannot be causally manipulated.

Here is a roadmap to the rest of the paper. We begin in

Section 2 with a concrete procedure for causal discovery called Greedy Equivalent Search (GES) [

2,

18], which illustrates the definition of causal equivalence we wish to study in its topological and homotopic sense, and which is also illustrative of a broad class of similar algorithms. Numerous refinements are possible, including the ability to intervene on arbitrary subsets [

14,

15], which we overlook in the interests of simplicity.

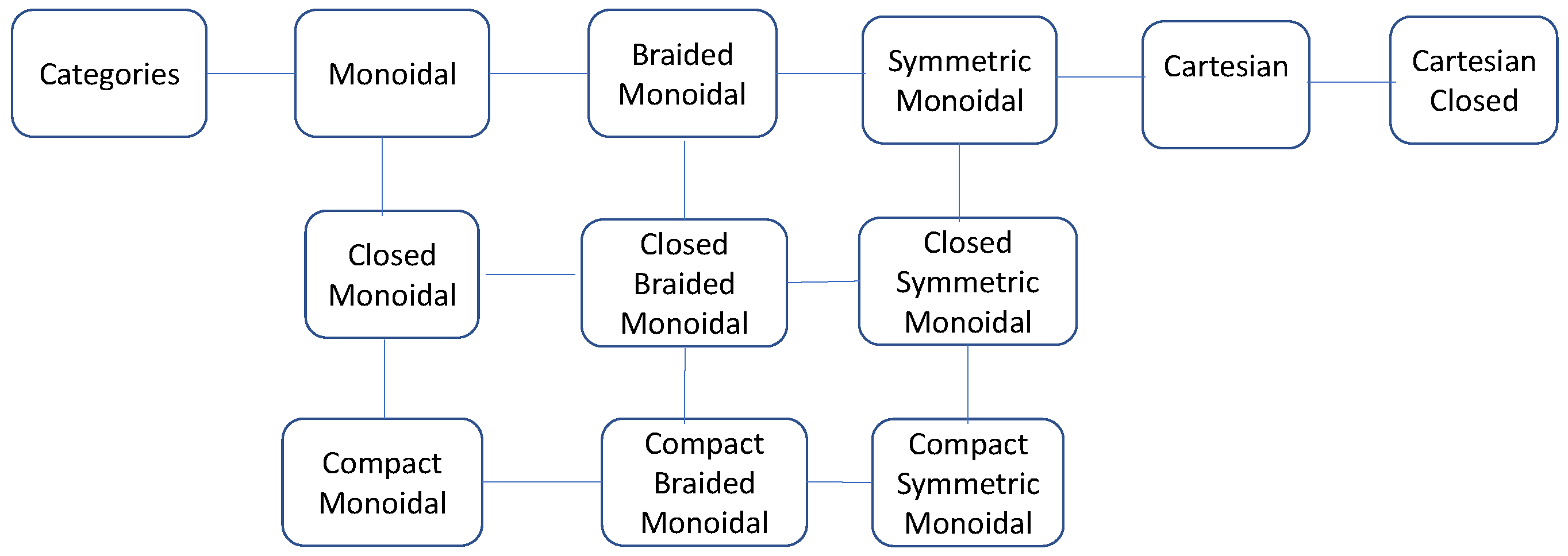

Section 3 begins with an introduction to algebraic theories of the type proposed by Lawvere [

5], a brief review of symmetric monoidal categories and an introduction to PROPs and cPROPs. We define functor categories mapping a PROP to a symmetric monoidal category. We review the central result of Fox showing that the inclusion of all Cartesian categories

CART in the larger category of all symmetric monoidal categories

MON has a right adjoint, which is defined by a coalgebraic PROP functor category. This coalgebraic structure relates to the “uniform copy-delete" structure studied by [

34]. In

Section 4, we explore the relationships between cPROPs with uniform copy and delete natural transformations and previous work on affine CDU categories [

7] and Markov categories [

6]. In

Section 5, we give a brief overview of Cartesian symmetric monoidal structure in topological spaces, which motivates our use of simplicial set topological realizations of cPROPs. In

Section 6, we define simplicial objects in cPROP categories.

Section 7 defines the abstract homotopy of cPROPs at a high level.

Section 8 drills down into showing the homotopic structure of cPROP functors that represent Bayesian networks, which closely relates to the work on CDU functors [

8]. We characterize natural transformations in the functor category of Bayesian networks modeled as cPROPs using Yoneda’s coend calculus [

23], and define an equivalence relationship among functors. In particular, we present categorical generalizations of the definitions of equivalent causal models in [

2,

18], and state a homotopic generalization of the well-known Meek-Chickering theorem for cPROPs. We associate with each edge reversal of a covered edge corresponds to natural transformation between corresponding cPROP functor. We formally characterize the classifying spaces of cPROPs in terms of associative and commutative

H-spaces [

32]. Finally, we combine the results of the previous section in

Section 10, stating the main result that the Grayson-Quillen procedure applied to cPROP yields a category

that represents a Grothendieck group completion of cPROP category

and whose connected components that define the 0

th order homology (loop) space is isomorphic to the Meek-Chickering equivalence classes. We summarize the paper and outline a few directions for further work in

Section 11.

2. Greedy Equivalence Search

To motivate the theoretical development in subsequent sections, we focus our attention in this section to a specific causal discovery algorithm, Greedy Equivalence Search (GES), originally proposed by Meek [

18], whose correctness and asymptotic optimality was subsequently shown by Chickering [

2] constituting an a algorithmic proof of the Meek-Chickering theorem. We do not present this framework as a state of the art causal discovery algorithm (e.g., Zanga and Stella [

3] provide a detailed survey of many causal discovery methods), but rather as an exemplar of the idea of searching in a space of equivalence classes of DAG models. Our ultimate goal is to provide a topological and abstract homotopic characterization of the search space in causal discovery, both for DAG and non-DAG models. It would help concretize the following theoretical abstractions to ground out the ideas in a specific algorithm.

For the sake of space, our discussion will be brief, and we relegate all missing details to the original paper [

2]. Broadly, the idea underlying GES is to search over equivalence classes of DAGs, by moving at each step to a

neighbor – meaning a model outside the current equivalence class by edge addition or deletion – that has the highest Bayesian score on a given IID dataset, if it improves the score. Bayesian approaches to learning models from data use a scoring function, such as Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), denoted as

where

D is an IID (independent and identically distributed) dataset sampled from the original (unknown) model. It is commonly assumed that such as a score is locally decomposable, meaning that

meaning that the overall score of a candidate DAG G is the sum of local scores for each node

that is purely a function of the projected data

D onto the node and its parents

. Given a dag G and a probability distribution

, G is a

perfect map of

p if (i) every independence constraint in

p is implied by the structure of G and (ii) every independence constraint implied by the structure of G holds in

p. If there exists a DAG G that is a perfect map of distribution

,

p is called

DAG-perfect. Under the assumption that the dataset

D is an IID sample from some DAG-perfect distribution

, the GES algorithm consists of two phases that is guaranteed to find the correct DAG G optimally in the limit of large datasets. The precise statement is as follows:

Theorem 1.([2]) Let denote the equivalence class that is a perfect map of the generative distribution and let m be the number of samples in a datasetD. Then in the limit of large m, for any equivalence class .

Here, is a Bayesian scoring method, like BIC, and it is assumed to score all DAGs in an equivalence class the same. The notion of equivalence classes is obviously fundamental to GES, and the formal statement of this characterization comes from the following transformational characterization of Bayesian networks. As previously noted, a covered edge in a DAG G is an edge with the property that the parents of Y are the same as the parents of X along with X itself.

Theorem 2.

(Meek-Chickering Theorem[2,18]) Let and be any pair of DAGs such that , meaning that is an independence map of , that is, every independence property in holds in . Intuitively, implies contains more edges than . Let r be the number of edges in that have opposite orientations in and let m be the number of edges in that do not exist in either orientation in G. Then, there is a sequence of edge reversals and additions in with the following properties:

Each edge reversed is a covered edge.

After each reversal and addition, is a DAG and .

After all reversals and additions, .

To relate this result and the ensuing GES algorithm to the original PC algorithm illustrated in

Figure 2, unlike PC, GES begins at the opposite end of the lattice of DAG models shown in

Figure 1, the empty DAG (which can be viewed as the

DAG in Theorem 2, and then progressively adds edges in the first phase, and then deletes edges in the second phase. In

Section 8, we will generalize this theorem to construct a topological and abstract homotopical equivalence across functors between cPROP categories. These functors are equivalent to the CDU functors proposed by Jacobs et al. [

8] to model Bayesian networks previously. Edge reversals or additions will correspond to natural transformations.

A further characterization of causal equivalence classes emerges from our application of higher algebraic K-theory [

9,

10]. Informally, we can define the notion of connectedness of a category in terms of the equivalence class of the relation defined over morphisms (two objects are in the same equivalence class if they are connected by a (perhaps zig-zag) morphism). We can treat each equivalence class as a topologically locally connected space and then the homotopy groups

of the classifying space BC of cPROP category

gives us an algebraic invariant of causal equivalence classes.

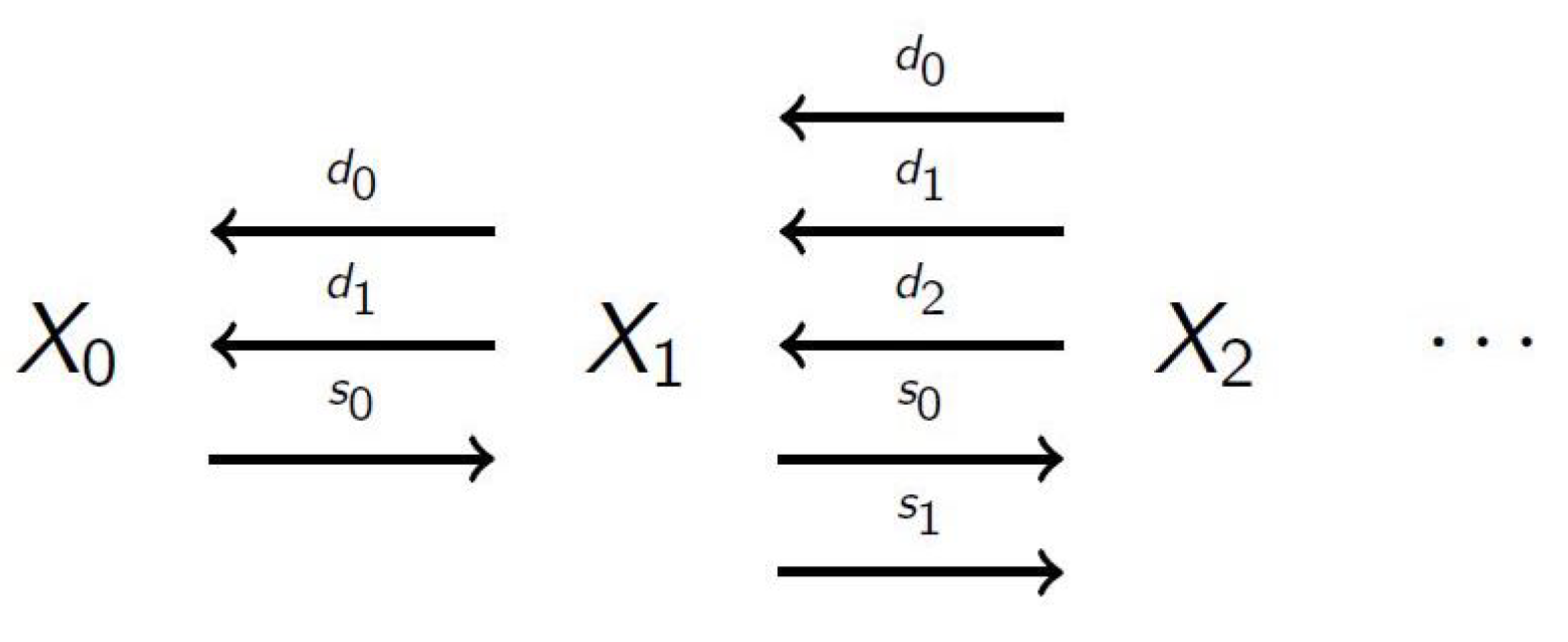

6. Simplicial Objects in cPROPs

We now turn to the embedding of cPROPs in the category of simplicial sets, which will be a prelude to constructing “nice" topological realizations and the study of their classifying spaces. To help guide intuition, a general principle in category theory is to replace objects

X by their

resolution that are “weakly equivalent" to it in some way, and that satisfy properties that the original objects do not (like limits and pullbacks, or colimits and pushouts). In Quillen’s model category framework for doing abstract homotopy in a category [

10], a (co)fibrant object play this role of having useful properties that the original objects do not, but are weakly equivalent to them. For example, in a cPROP (or Markov category), where

I is a terminal object, an object

X is considered a fibrant object if the unique morphism

to the terminal object is a fibration. We discuss below these notions using the framework of lifting diagrams. In this paper, we will not get into the details of model category structure for cPROPs (or Markov categories), but it will suffice to introduce ideas that will allow us to define the necessary homotopy structures in

Section 7.

Figure 6 gives the high level intuition. A simplicial set

X is defined as a collection of sets

, combined with degeneracy maps (indicated as

in the figure) and face maps (indicated as

in the figure). As a simple guide to help build intuition, any directed graph can be viewed as a simplicial set, where

is the set

V of vertices,

is the

E of edges, and the two face maps

and

from

to

yield the initial and final vertex of the edge. The single degeneracy map

between

and

adds a self loop to each vertex. Simplicial sets generalize graphs when we consider higher-order simplices. For example, between

and

, there are three face maps, mapping a simplicial triangle (a

)

to each of its 1-simplicial components, namely its edges.

We give a brief review of simplicial sets, summarizing some points we made in our previous paper on simplicial set representations in causal inference [

29]. A more detailed review can be found in many references [

32,

37]. Simplicial sets are higher-dimensional generalizations of directed graphs, partially ordered sets, as well as regular categories themselves. Importantly, simplicial sets and simplicial objects form a foundation for higher-order category theory [

30,

31]. Using simplicial sets and objects enables a powerful machinery to reason about both directional and non-directional paths in causal models, and to model equivalence classes of causal models.

Simplicial objects have long been a foundation for algebraic topology [

37,

38], and more recently in higher-order category theory [

30,

31,

39]. The category

has non-empty ordinals

as objects, and order-preserving maps

as arrows. An important property in

is that any many-to-many mapping is decomposable as a composition of an injective and a surjective mapping, each of which is decomposable into a sequence of elementary injections

, called

coface mappings, which omits

, and a sequence of elementary surjections

, called

co-degeneracy mappings, which repeats

. The fundamental simplex

is the presheaf of all morphisms into

, that is, the representable functor

. The Yoneda Lemma [

23] assures us that an

n-simplex

can be identified with the corresponding map

. Every morphism

in

is functorially mapped to the map

in

.

Any morphism in the category

can be defined as a sequence of

co-degeneracy and

co-face operators, where the co-face operator

is defined as:

Analogously, the co-degeneracy operator

is defined as

Note that under the contravariant mappings, co-face mappings turn into face mappings, and co-degeneracy mappings turn into degeneracy mappings. That is, for any simplicial object (or set) , we have , and likewise, .

The compositions of these arrows define certain well-known properties [

32,

37]:

Example 2. The “vertices” of a simplicial object X in a cPROP category are the objects in , and the “edges” are its arrows , where and are objects in . Note that is a contravariant functor , and since has only one object, the effect of this functor is to pick out objects in . The simplicial object . Given any such arrow, the face operators and recover the source and target of each arrow. Also, given an object X of category , we can regard the degeneracy operator as its identity morphism .

Example 3.

Given a cPROP category , we can identify an n-simplex of a simplicial object in a cPROP category with the sequence:

the face operator applied to yields the sequence

where the object is “deleted” along with the morphism leaving it.

Example 4.

Given a cPROP category , and an n-simplex of the simplicial object in a cPROP category , the face operator applied to yields the sequence

where the object is “deleted” along with the morphism entering it.

Example 5.

Given a cPROP category , and an n-simplex of the simplicial object, the face operator applied to yields the sequence

where the object is “deleted” and the morphisms is composed with morphism .

Example 6.

Given a cPROP category , and an n-simplex of the simplicial object defined over the cPROP category, the degeneracy operator applied to yields the sequence

where the object is “repeated” by inserting its identity morphism .

Definition 19.

Given a cPROP category , and an n-simplex of the simplicial object associated with the category, is adegeneratesimplex if some in is an identity morphism, in which case and are equal.

6.1. Simplicial Subsets and Horns of cPROP Categories

One significant strength of the simplicial object construction outlined above is that the resulting structures lead to topologically “nice" representations, in particular CW-complexes [

33]. One crucial property is that any

simplex

can be formed as a retract of an

n-simplex

by applying one of the face operators described earlier. Such nice structures are called Kan complexes. To define this property, we describe simplicial subsets and horns. These structures will play a key role in defining suitable lifting problems that are needed to explain Kan complexes.

Definition 20.

Thestandard simplex is the simplicial set defined by the construction

By convention, . The standard 0-simplex maps each to the single element set .

Definition 21.

Let S denote a simplicial object, where is its simplex. If for every integer , we are given a subset , such that the face and degeneracy maps

then the collection defines asimplicial subset

Definition 22.

Theboundaryis a simplicial set Setdefined as

Note that the boundary is a simplicial subset of the standard n-simplex .

Definition 23.

TheHornSetis defined as

Intuitively, the Horn can be viewed as the simplicial subset that results from removing the interior of the n-simplex together with the face opposite its ith vertex.

6.2. Lifting Problems in cPROP Categories

Lifting problems provide elegant ways to define basic notions in a wide variety of areas in mathematics [

40]. For example, the notion of injective and surjective functions, the notion of separation in topology, and many other basic constructs can be formulated as solutions to lifting problems. Database queries in relational databases can be defined using lifting problems [

41]. Lifting problems define ways of decomposing structures into simpler pieces, and putting them back together again. Our goal here is to illustrate that simplicial objects in Markov categories can solve certain types of lifting problems corresponding to inner horns. A fuller discussion of these issues can be found in [

31].

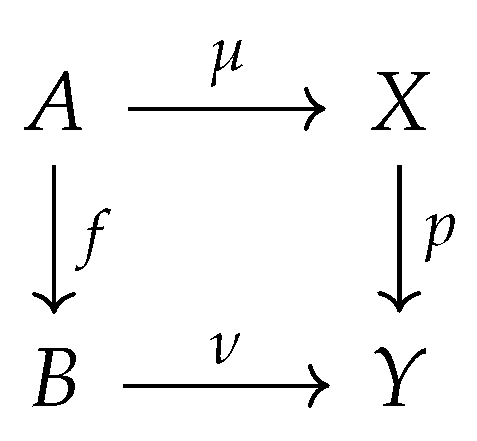

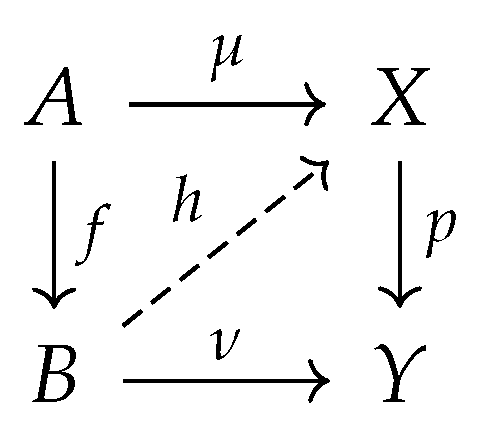

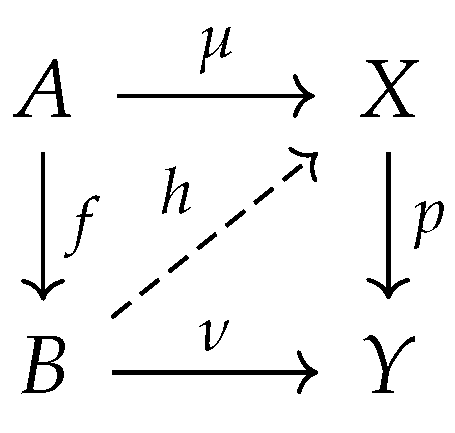

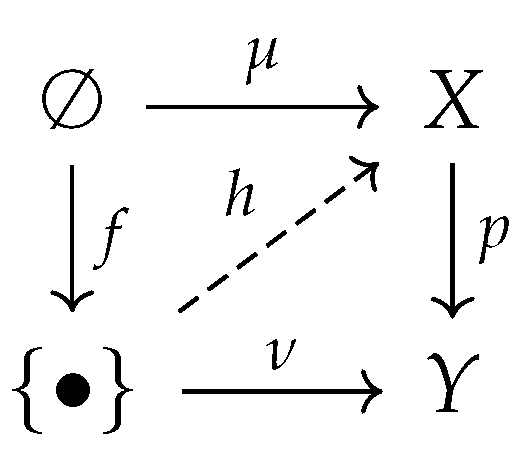

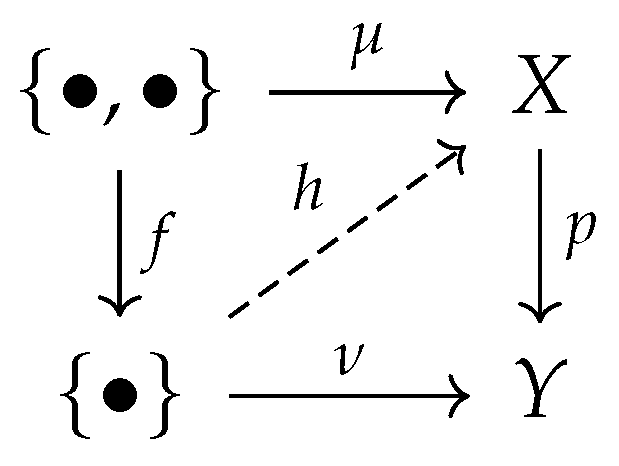

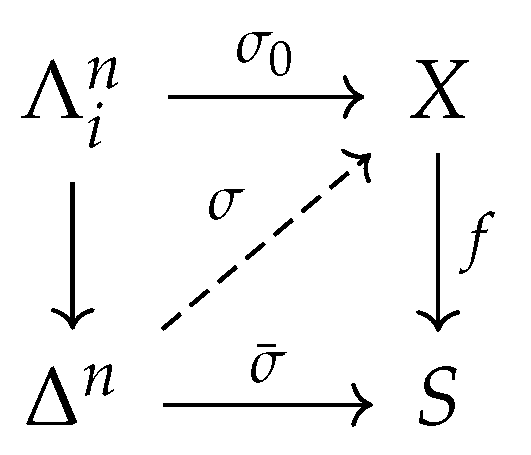

Definition 24.

Let be a cPROP category. Alifting problemin is a commutative diagram σ in .

Definition 25.

Let be a cPROP category. Asolution to a lifting problemin is a morphism in satisfying and as indicated in the diagram below.

Definition 26.

Let be a cPROP category. If we are given two morphisms and in , we say that f has theleft lifting propertywith respect to p, or that p has theright lifting propertywith respect to f if for every pair of morphisms and satisfying the equations , the associated lifting problem indicated in the diagram below.

admits a solution given by the map satisfying and .

Example 7.

Given the paradigmatic non-surjective morphism , any morphism p that has the right lifting property with respect to f is asurjective mapping. .

Example 8.

Given the paradigmatic non-injective morphism , any morphism p that has the right lifting property with respect to f is aninjective mapping. .

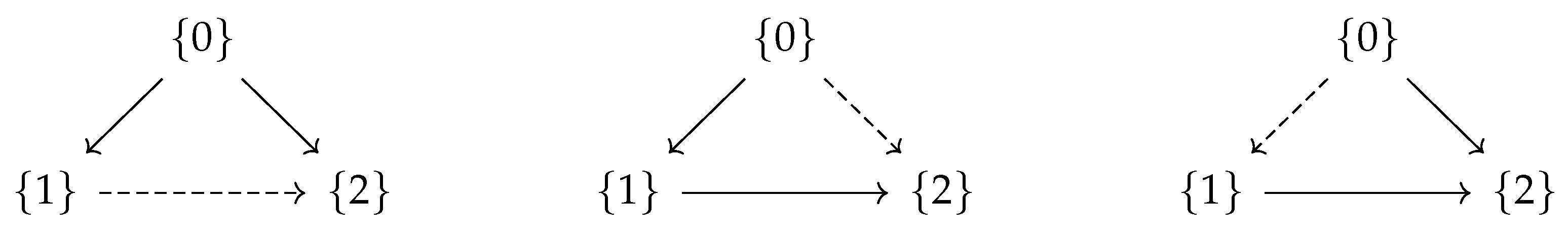

6.3. Filling Inner vs. Outer Horns in Markov Categories

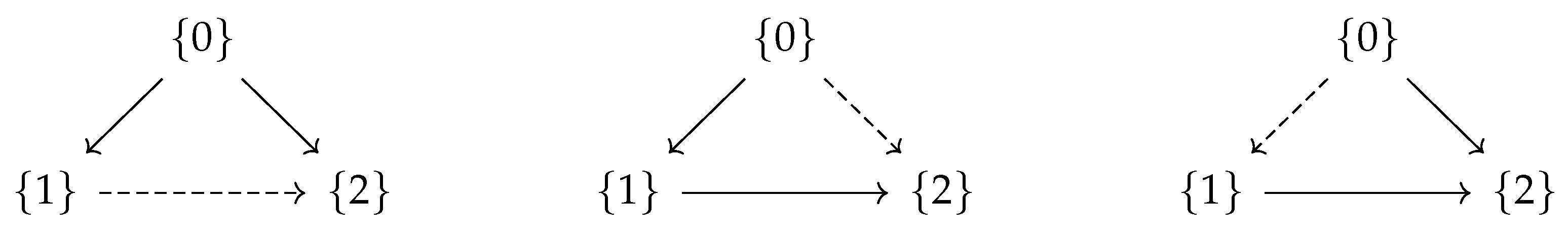

Consider the problem of composing 1-dimensional simplices to form a 2-dimensional simplicial object in a Markov category . Each simplicial subset of an n-simplex induces a a horn, where . Intuitively, a horn is a subset of a simplicial object that results from removing the interior of the n-simplex and the face opposite the ith vertex. Consider the three horns defined below. The dashed arrow ⤏ indicates edges of the 2-simplex not contained in the horns.

The inner horn

is the middle diagram above, and admits an easy solution to the “horn filling” problem of composing the simplicial subsets. The two outer horns on either end pose a more difficult challenge. For example, filling the outer horn

when the morphism between

and

is

f and that between

and

is tantamount to finding the left inverse of

f up to homotopy. Dually, in this case, filling the outer horn

is tantamount to finding the right inverse of

f up to homotopy. A considerable elaboration of the theoretical machinery in category theory is required to describe the various solutions proposed, which led to different ways of defining higher-order category theory [

30,

31,

39].

6.4. Kan complexes in cPROP Categories

To show that the nerve functor applied to cPROP categories produces only certain types of lifts, we need to introduce the notion of fibrations.

Definition 27.

Let be a morphism of simplicial objects in a cPROP category . We say f is aKan fibrationif, for each , and each , every lifting problem.

admits a solution. More precisely, for every map of simplicial sets and every n-simplex extending , we can extend to an n-simplex satisfying .

Example 9.

Given a simplicial object X in a cPROP category , a projection map that is a Kan fibration is called aKan complex

.

Example 10. Any isomorphism between simplicial objects in a cPROP category is a Kan fibration.

Example 11. The collection of Kan fibrations in cPROP categories is closed under retracts.

Definition 28. [31] A simplicial object X in a cPROP category satisfies the following condition:

Simplicial objects in cPROP categories can solve inner horn extension problems, but not the outer horn problems that are more challenging. are thus Kan complexes, which is obvious from the construction of the nerve functor. Simplicial objects that satisfy property C above can be identified with the nerve of a category, which yields a full and faithful embedding of a category in the category of sets. Definition 28 generalizes both of these definitions, and was called a

quasicategory in [

30] and

weak Kan complexes in [

39] when

is a category. We will use the nerve of a category below in defining homotopy colimits as a way of characterizing a causal model.

6.5. Topological Embedding of Simplicial Objects in cPROP Categories

Simplicial objects in cPROP categories can be embedded in a topological space using a construction originally proposed by Milnor [

33].

Definition 29.

Thegeometric realization of a simplicial object X in cPROP category defined as the topological space

where the n-simplex is assumed to have adiscrete

topology (i.e., all subsets of are open sets), and denotes thetopological

n-simplex

The spaces can be viewed ascosimplicial

topological spaces with the following degeneracy and face maps:

Note that , whereas .

The equivalence relation ∼ above that defines the quotient space is given as:

Topological Embeddings as Coends

We now bring in the perspective that topological embeddings of simplicial objects in cPROP categories can be interpreted as a coend [

23] as well. Consider the functor

where

where

F acts

contravariantly as a functor from

to

mapping

, and

covariantly mapping

as a functor from

to the category

of topological spaces.

The coend defines a topological embedding of a simplicial object

X in a cPROP category, where

represents composable morphisms of length

n. Given this simplicial object, we can now construct a topological realization of it as a coend object

where

is the simplicial object defined by the contravariant functor from the simplicial category

into the category of simplicial objects in cPROP categories, and

is a functor from the topological

n-simplex realization of the simplicial category

into topological spaces

. As MacLane [

23] explains it picturesquely, the “coend formula describes the geometric realization in one gulp". The formula says essentially to take the disjoint union of affine

n-simplices, one for each

, and glue them together using the face and degeneracy operations defined as arrows of the simplicial category

.

8. Classifying Spaces of Functors on cPROP Categories

In this section, we drill down from the abstractions above to prove a set of more concrete results regarding the classifying spaces of cPROP functors that correspond to Bayesian networks [

44], and can be seen as analogous to CDU functors in affine CD categories [

8]. In this section, we restrict our attention to the cPROP category

defined by the coalgebraic PROP

defined by the PROP maps

and

, as discussed earlier in

Section 3. We also build on the results of the previous sections to state a categorical generalization of the Meek-Chickering (MC) theorem for cPROP categories [

2,

18]. This theorem, originally stated as a conjecture in Meek’s dissertation [

18] was formally proved by Chickering [

2]. The MC theorem states that given any two causal DAG models

and

, where

is an

independence map of

, that is any conditional independence implied by the structure of

is also implied by the structure of

. Furthermore, there exists a finite sequence of edge additions and

covered edge reversals such that after each edge change,

remains a DAG, and

remains an independence map of

, and finally

after the sequence is completed.

To begin with, we build on the characterization of a causal DAGs

, or Bayesian networks [

12,

44], as functors from the cPROP (or equivalently CDU) category

to

FinStoch (see [

8] for more details). We assume the reader is familiar with the terminology of DAG models in this section, and we refer the reader to [

2] for additional details that we omit in the interests of space. We give a brief overview of the Markov category

FinStoch (which was called

Stoch in [

8]), whose objects are finite sets and morphisms

. States are stochastic matrices from a trivial input

, are essentially column vectors representing marginal distributions. The counit is a stochastic matrix with a row vector consisting only of 1’s. The composition of morphisms is defined by matrix multiplication. The monoidal product ⊗ in

FinStoch is the Cartesian product on objects, and Kronecker product of matrices:

. The Kronecker product corresponds to taking product distributions.

FinStoch realizes the “swap" operation defined by the string diagram in Definition 10 as

given by

, making it into a symmetric monoidal category.

Theorem 14.(Proposition 3.1, [8]) There is a 1-1 correspondence between Bayesian networks based on a DAG and cPROP functors of the type FinStoch

This theorem is essentially the same as that in [

8], since functors between CDU categories

and

FinStoch are special types of functors between cPROP categories. We can model the category of all Bayesian networks as a functor category

on cPROP categories. In this section, we explore the homotopic structure of this functor category, whose objects are Bayesian networks represented as functors, and whose arrows are natural transformations.

Let us now build on the homotopic structures defined earlier in

Section 7 in terms of viewing each cPROP category

in terms of its classifying space

. The following theorem is straightforward to prove.

Theorem 15.

Each Bayesian network encoded as a cPROP functor FinStochinduces a continuous and cellular map of CW complexes (i.e., compactly generated spaces with a weak Hausdorff topology [35]).

Proof. Recall that B is a functor from the category

Cat to the category Top of topological spaces defined as the classifying space of a category, constructed by forming the simplicial set using the nerve of the category (where each

n-simplex represents composable morphisms in a category of length

n), and using its topological realization as defined by Milnor [

33]. □

We can define an equivalence structure on cPROP functors representing DAG models, generalizing the classical definitions in Pearl [

12], and using Theorem 14 above.

Theorem 16.

Two cPROP functors FinStochand FinStochareequivalent, denoted as where we use the same symbol ≈ used in [2] for DAG equivalence, if they are constructed from DAG models and , respectively, that have the same skeletons and the same v-structures.

Proof. Two DAGs are known to be equivalent, meaning they are distributionally equivalent and independence equivalent, if their skeletons, namely the underlying undirected graph ignoring edge orientations, are isomorphic, and have the same v-structures, meaning an ordered triple of nodes where contains the edges and and X and Z are not adjacent in . Given that Theorem 14 gives us a 1-1 correspondence between DAG models and cPROP functors, the theorem follows straightforwardly. □

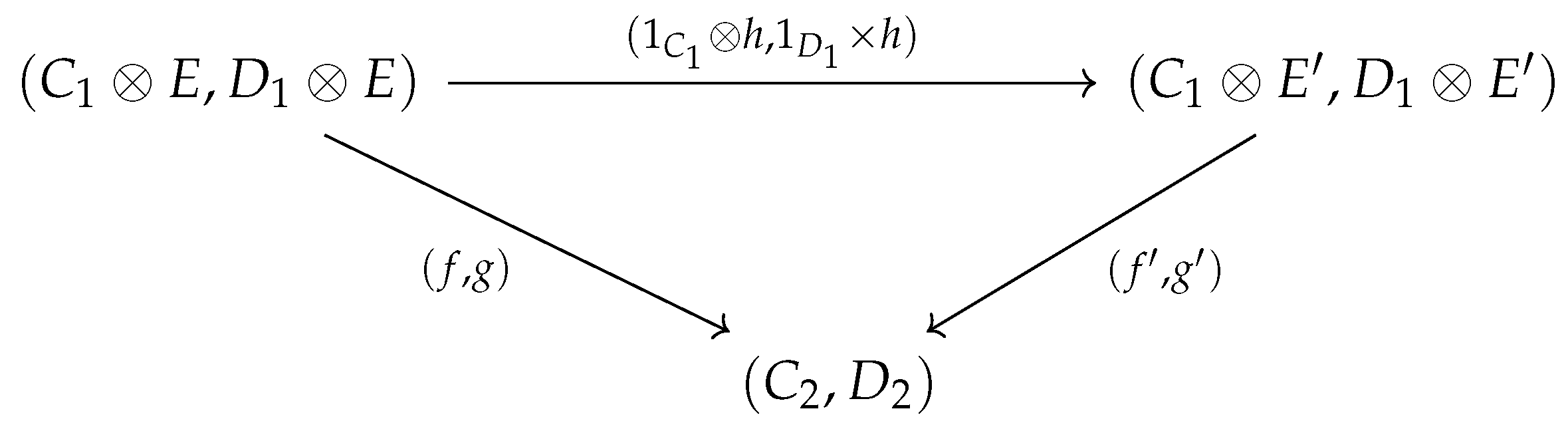

We can characterize the interaction between two Bayesian networks represented as cPROP functors through Yoneda’s (co)end calculus, where for simplicity we use the same cPROP category to denote that these DAGs have the same skeleton and v-structures.

Theorem 17.

Given two cPROP functors FinStochand FinStochrepresenting two DAG models, the set of natural transformations between them can be defined as an end

Proof. The proof of this result follows readily from the standard result that the set of natural transformations between two functors is an end (see page 223 in [

23]). □

We can this use this result to construct a homotopic structure on the topological space of all continuous and cellular maps of CW complexes defined in Theorem 15 above.

Theorem 18.

The topological space of all continuous and cellular maps of CW complexes, where each map is defined as

is decomposed into equivalence classes by the equivalence relation ≈ defined in Theorem 16.

Proof. The equivalence relation ≈ on cPROP functors is reflexive, symmetric and transitive, because as Theorem 14 showed, there is a 1-1 correspondence between causal DAG models and cPROP functors. Each equivalence class of DAG models maps precisely into an equivalence class of cPROP functors. □

Theorem 19. We can now bring to bear some properties of the classifying space developed by Segal [9] to construct a homotopy on cPROP categories and functors.

For any two cPROP functors FinStochand FinStoch, a natural transformation induces a homotopy between and .

If and is an adjoint pair of functors, then is homotopy equivalent to (here, is a subcategory of that is defined by the mapping of each object and morphism in ).

Proof.

We can think of the natural transformation

as a functor

from

to

. We define the action of

on objects as

and

. On morphisms

, we can set

and

. For the only non-trivial morphism

in

, we define

. The composite structure

yields the desired homotopy.

Given any adjoint pair of functors and , we can define the induced natural transformations and . From the just established results on the natural transformation , the desired homotopy follows.

□

8.1. Generalizing the Meek-Chickering Theorem to cPROP Categories

We now turn to discussing a homotopic generalization of the Meek-Chickering theorem for DAG models [

2,

18] to functors between cPROP categories defined above.

Definition 39.

Let be a cPROP functor defined from , any DAG model. An edge iscoveredif X and Y have identical parents, with the caveat that X is not a parent of itself. In other words, the parents of Y in are the parents of X along with X itself. Then, each covered edge in induces a corresponding covered morphism in that corresponds to in the corresponding cPROP category .

Since cPROP functors are in 1-1 correspondence with DAG models from Theorem 14, we can associate with any covered edge in a DAG model , an equivalent covered morphism in the Markov category associated with the DAG model .

Theorem 20. Let be any DAG model, with associated cPROP functor , and let ’ be the result of reversing the edge , and let be the corresponding modified cPROP functor. Then there is an induced natural transformation corresponding to reversing an edge, and using the definition of cPROP functor equivalence in Theorem 16 if and only if the edge is a covered edge in .

Proof. The proof of this theorem follows readily from Lemma 2 in [

2] showing that

’ is a DAG model that is equivalent to

if and only if the edge that is reversed, namely

, is covered in

. □

Theorem 21. [2] Let and be a pair of equivalent cPROP functors corresponding to two equivalent DAG models and , for which there δ edges in that have the opposite orientation in . Then, there exists a sequence of δ corresponding natural transformations transforming the functor into the functor , where natural transformation can be implemented by constructing the cPROP functor for each intervening DAG model that is based on reversing a single additional edge, satisfying the following properties:

Each natural transformation in must correspond to a covered edge in .

After each natural transformation, the functors .

After all natural transformations are composed, the two functors .

Proof. Once again, the proof follows readily from the equivalent Theorem 3 in [

2] exploiting the isomorphism between causal DAG models and cPROP functors from Theorem 14. □

To state the homotopic generalization of the Meek-Chickering theorem for functors between cPROP categories, we need to define the partial ordering on cPROP functors.

Definition 40. Define the partial ordering to indicate that the corresponding causal DAG is an independence map of . Here, ≤ implies that if , then by necessity contains more edges than .

Once again, it follows from the 1-1 correspondence between Bayesian networks and cPROP functors that the corresponding cPROP category must contain more morphisms than . We can now state the generalized Meek-Chickering theorem for functors between cPROP categories.

Theorem 22.

Let and be cPROP categories corresponding to any pair of DAGs and such that . Let r be the number of edges in that have the opposite orientation in , and let m be the number of edges in that do not exist in either orientation in . These edges translate correspondingly to the differences in morphisms in and. Then, there exists a sequence of at most natural transformations that map the cPROP functor into the cPROP functor satisfying the following properties:

Each edge reversal and corresponding natural transformation corresponds to a covered edge.

After each natural transformation corresponding to an edge reversal and edge addition, .

After all natural transformations are composed, is a natural isomorphism.

Proof. The proof generalizes in a straightforward way from Theorem 4 in [

2] since we are exploiting the 1-1 correspondences between causal DAG models and cPROP functors. The proof of this theorem in [

2] is constructive since it involves an algorithm, and it would take more space than we have to sketch out the entire process of categorifying it. But, each step in the Algorithm

APPLY-EDGE-ORIENTATION in [

2] can be equivalently implemented for cPROP categories using the correspondences between causal DAGs and cPROP functors. □

8.2. The Category of Fractions in a cPROP Category

A principal challenge in causal discovery is that models can be inferred from data only up to an equivalence class.

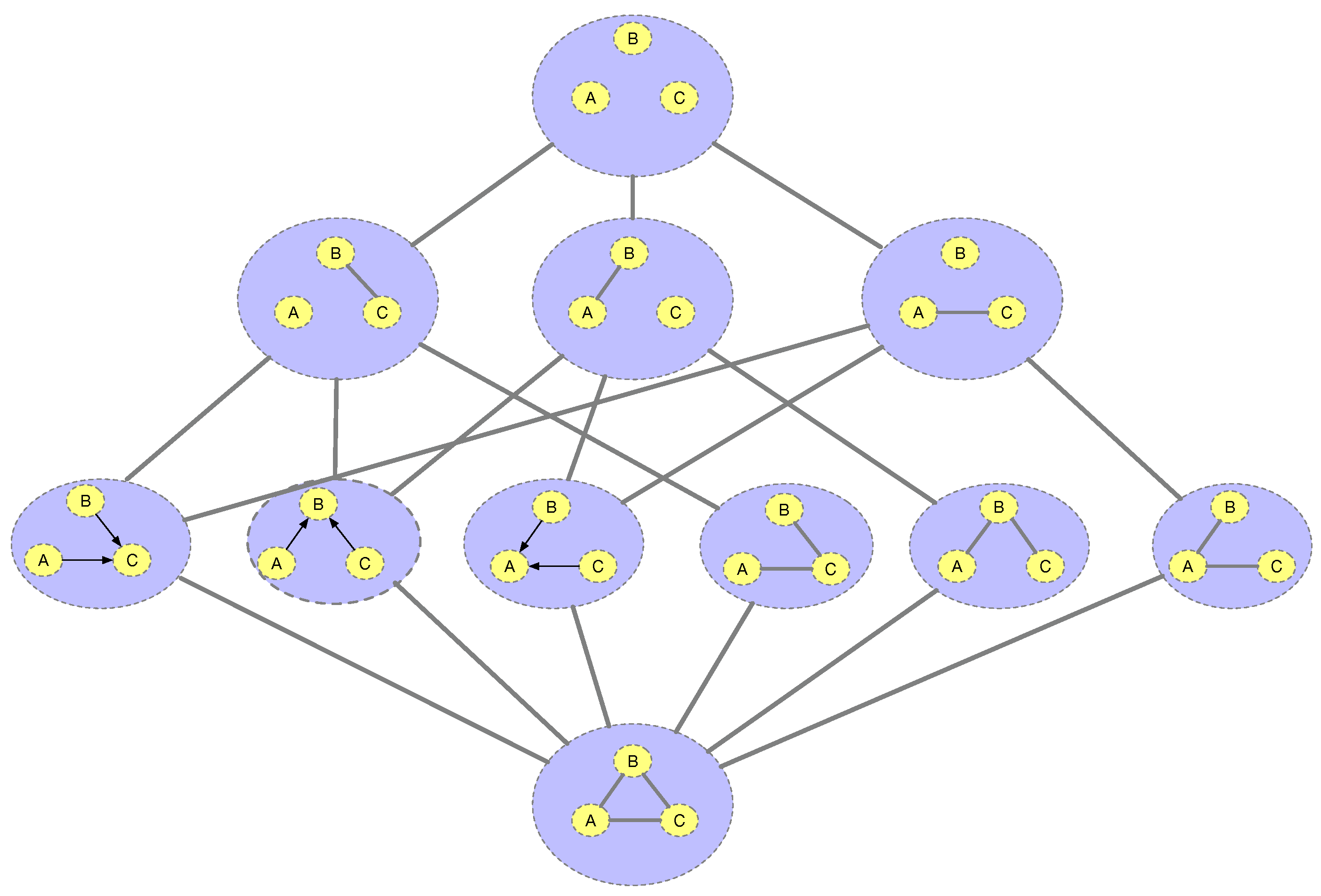

Figure 7 illustrates the equivalence classes of causal DAGs over 3 variables (this figure is reproduced from [

19], and can be viewed as an expanded version of

Figure 1).

We can view the morphisms between equivalent causal models as “invertible” arrows. The problem of defining a category with a given subclass of invertible morphisms, is called the category of fractions [

45]. It is also useful in the context of causal inference, as for example, in defining the Markov equivalence class of directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) as a category that is localized by considering all invertible arrows as isomorphisms. Borceux [

36] has a detailed discussion of the “calculus of fractions”, namely how to define a category where a subclass of morphisms are to be treated as isomorphisms. The formal definition is as follows:

Definition 41.

Consider a cPROP category and a class Σ of arrows of . Thecategory of fractions is said to exist when a category and a functor can be found with the following properties:

is an isomorphism.

If is a cPROP category, and is a functor such that for all morphisms , is an isomorphism, then there exists a unique functor such that .

A detailed construction of the category of fractions is given in [

36], which uses the underlying directed graph skeleton associated with the category. The characterization of the Markov equivalent class of acyclic directed graphs is an example of the abstract concept of category of fractions [

20]. Briefly, this condition states that two acyclic directed graphs are Markov equivalent if and only if they have the same skeleton and the same immoralities.

To summarize the results of this section, we showed that we can construct a homotopic equivalence across causal models represented as functors on cPROP categories. We introduced categorical generalizations of the definitions in [

2] and stated the categorical generalization of the Meek-Chickering theorem for Markov categories. We note that the results presented above are not the most general that can be shown, but for the purposes of this paper, we chose the simplest ones to present.

8.3. Homotopy Groups of Meek-Chickering Causal Equivalences

We can now define the equivalence classes under the Meek-Chickering formulation in a more abstract manner using abstract homotopy. First, we define the notion of an equivalence class of objects in any category simply as that defined by the connectedness relation defined by the morphisms. Two objects C and are in the same equivalence class in a category if the following structure holds true:

Definition 42.

Define the set ofpath componentsof a category as the set of equivalence classes of the morphism relation on the objects by .

Theorem 23. [32] The set of path components of the topological space , namely is in bijection with the set of path components of .

This relationship between the original category

and its topological realization

now gives us a homotopic characterization of the GES algorithm described in

Section 2. More formally, GES proceeds by moving from one equivalence class of causal models to the next by addition or removal of (non-covered) edges. These steps can be characterized in terms of natural transformations between equivalence classes of cPROP (or CDU [

8]) functors that define the causal DAGs. As shown in

Figure 7, we treat the equivalence class of DAGs within each connected component as a locally connected topological space. Thus, the set

is exactly the number of equivalence classes in

Figure 7, which is again the same as the number of connected components in

, defining the 0

th homotopy group in the topological realization of the category

.

Theorem 24. The GES procedure can be formally characterized topologically as moving from one equivalence class of connected topological spaces in to another, where an equivalence class of connected objects in is defined by the connectedness relation of natural transformations that correspond to reversals of covered edges within an equivalence class.

Proof: The proof of this theorem follows directly from Theorem 23, Theorem 2, and its homotopic version stated as Theorem 22. □