Submitted:

16 January 2025

Posted:

21 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

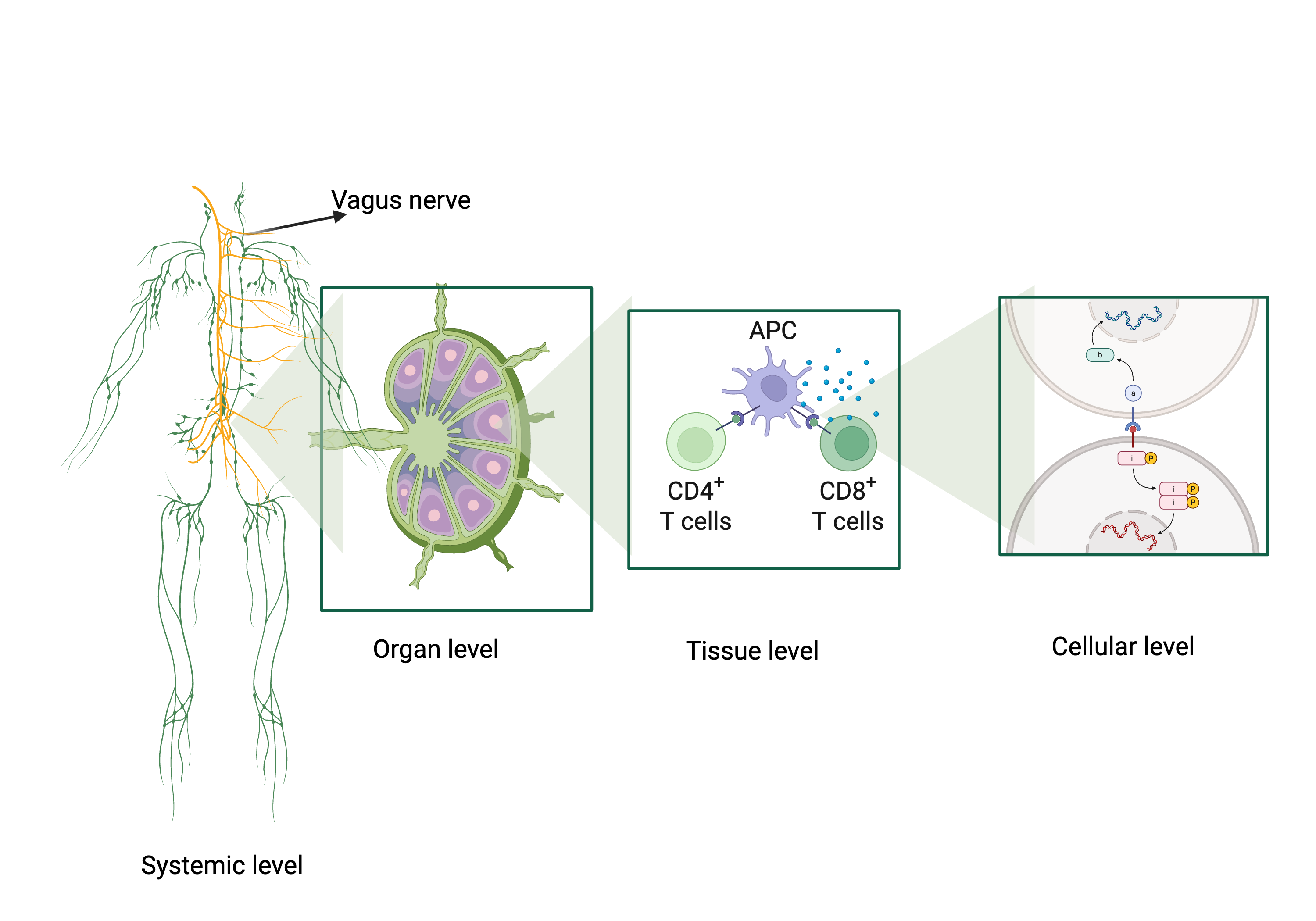

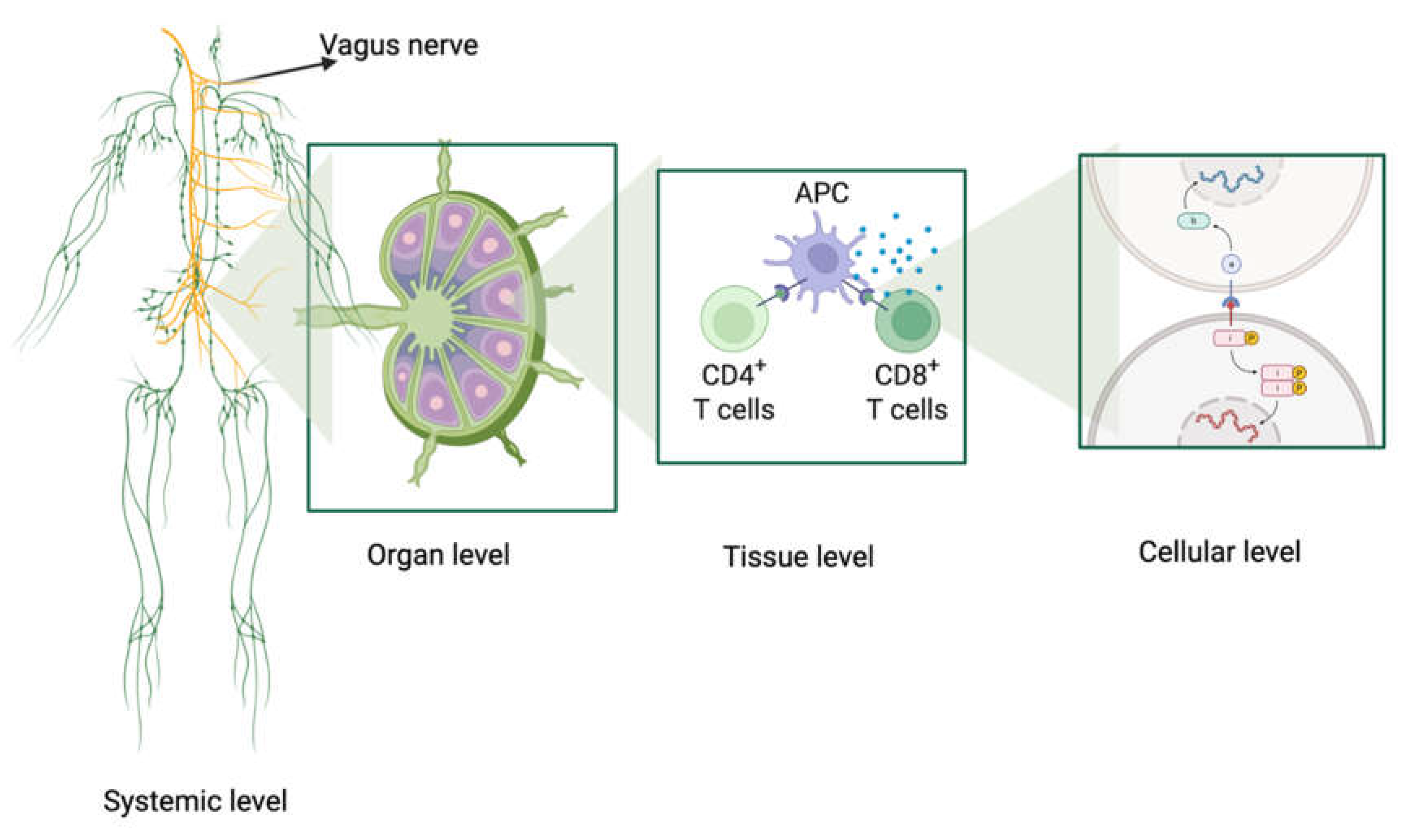

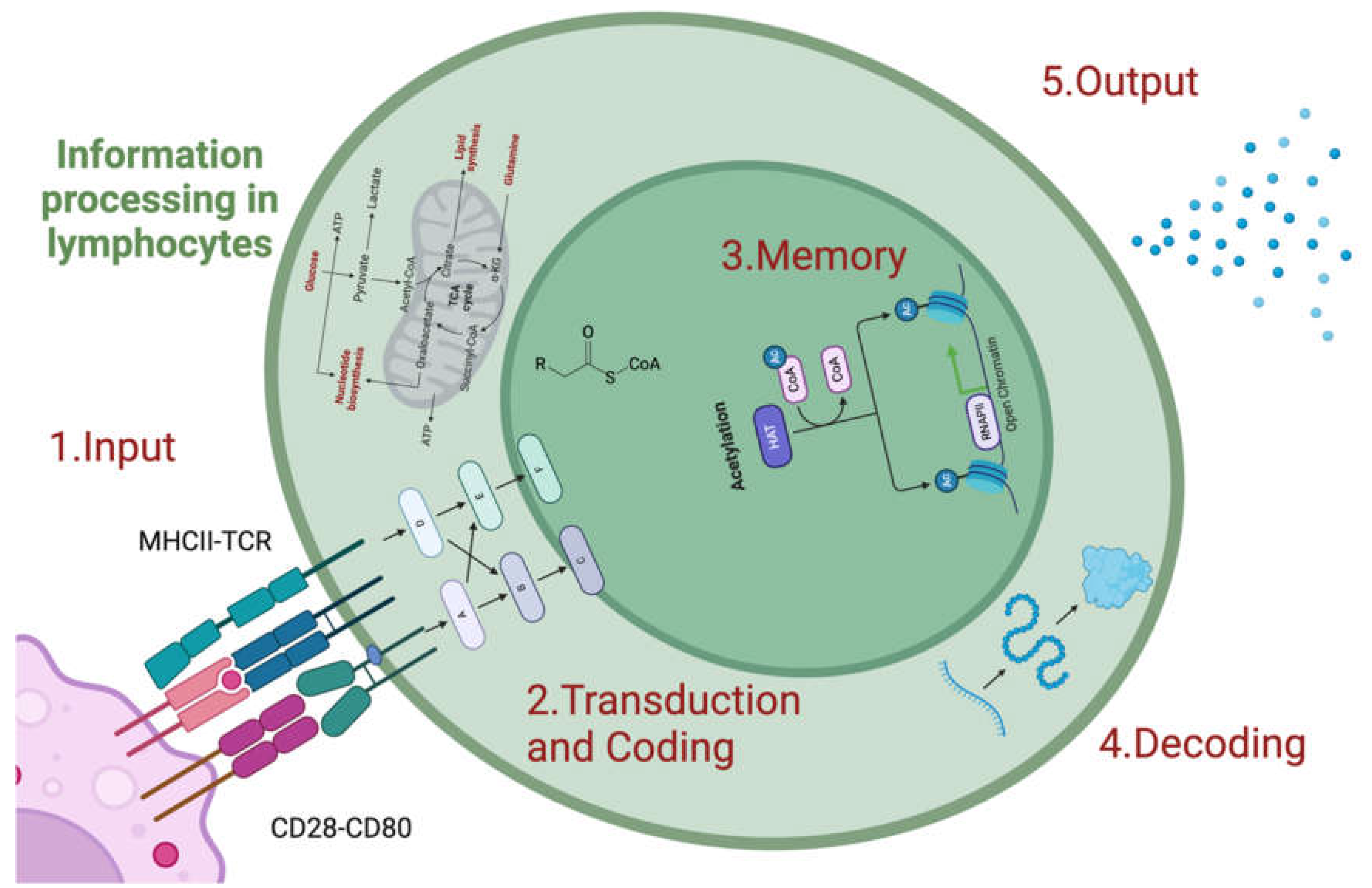

The immune system is a dynamic network that processes information across multiple biological scales, from molecular recognition of antigens to systemic coordination with the neuroimmune axis and microbiota. At the molecular level, pathways such as NF-κB and JAK-STAT regulate gene expression, integrating signals from pathogens and the organism itself while balancing activation through feedback loops. Cellular and tissue-level dynamics are exemplified by germinal centers, where B-cell hypermutation and clonal selection refine the humoral response, and by immunological synapses that regulate T-cell activation and fate. Systemically, the vagus nerve mediates neuroimmune interactions, while the microbiota co-evolves with the immune system, enhancing its plasticity and robustness. These processes embody antifragility, allowing the immune system to strengthen and expand its capabilities with each challenge. By understanding these multiscale processes, novel strategies emerge for precision medicine, including the modulation of the vagus nerve and microbiota, offering personalized approaches to treat infectious, autoimmune, and chronic diseases.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Multiscale Processing of Immunological Information

2.1. Molecular Scale

2.2. Cellular and Tissue Scale

2.3. Systemic and Neuroimmune Scale: A Dynamic, Adaptive Network with Deep Computational Processing

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shilts J, Severin Y, Galaway F, et al.: A physical wiring diagram for the human immune system. Nature 608: 397–404, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bausch-Fluck D, Goldmann U, Müller S, van Oostrum M, Müller M, Schubert OT and Wollscheid B: The in silico human surfaceome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115: E10988–E10997, 2018.

- Subramanian N, Torabi-Parizi P, Gottschalk RA, Germain RN and Dutta B: Network representations of immune system complexity. WIREs Systems Biology and Medicine 7: 13–38, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Richter PH: A network theory of the immune system. European Journal of Immunology 5: 350–354, 1975. [CrossRef]

- Taleb NN: Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder. New York, 2014.

- Axenie C, López-Corona O, Makridis MA, Akbarzadeh M, Saveriano M, Stancu A and West J: Antifragility as a complex system’s response to perturbations, volatility, and time. ArXiv: arXiv:2312.13991v1, 2023.

- Olivieri F, Prattichizzo F, Lattanzio F, Bonfigli AR and Spazzafumo L: Antifragility and antiinflammaging: Can they play a role for a healthy longevity? Ageing Research Reviews 84: 101836, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jaffe Y, Caramanica A and Price MD: Towards an antifragility framework in past human–environment dynamics. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10: 1–12, 2023.

- Axenie C, López-Corona O, Makridis MA, Akbarzadeh M, Saveriano M, Stancu A and West J: Antifragility in complex dynamical systems. npj Complex 1: 1–8, 2024.

- Optimal biochemical information processing at criticality | bioRxiv.

- Habibollahi F, Kagan BJ, Burkitt AN and French C: Critical dynamics arise during structured information presentation within embodied in vitro neuronal networks. Nat Commun 14: 5287, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Manicka S, Marques-Pita M and Rocha LM: Effective connectivity determines the critical dynamics of biochemical networks. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 19: 20210659, 2022.

- O’Donnell TJ, Kanduri C, Isacchini G, et al.: Reading the repertoire: Progress in adaptive immune receptor analysis using machine learning. cels 15: 1168–1189, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Klemm K and Bornholdt S: Topology of biological networks and reliability of information processing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102: 18414–18419, 2005.

- Leydesdorff L: Redundancy in Systems Which Entertain a Model of Themselves: Interaction Information and the Self-Organization of Anticipation. Entropy 12: 63–79, 2010.

- Zipp F, Bittner S and Schafer DP: Cytokines as emerging regulators of central nervous system synapses. Immunity 56: 914–925, 2023.

- Becher B, Derfuss T and Liblau R: Targeting cytokine networks in neuroinflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 23: 862–879, 2024.

- Britt EC, John SV, Locasale JW and Fan J: Metabolic regulation of epigenetic remodeling in immune cells. Curr Opin Biotechnol 63: 111–117, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Reid MA, Dai Z and Locasale JW: The impact of cellular metabolism on chromatin dynamics and epigenetics. Nat Cell Biol 19: 1298–1306, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Flavahan WA, Gaskell E and Bernstein BE: Epigenetic plasticity and the hallmarks of cancer. Science 357: eaal2380, 2017.

- Sheedy FJ and Kaufmann E: Linking metabolic and epigenetic changes in immune tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 121: e2419751121, 2024.

- Abhimanyu null, Longlax SC, Nishiguchi T, et al.: TCA metabolism regulates DNA hypermethylation in LPS and Mycobacterium tuberculosis-induced immune tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 121: e2404841121, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bláha J, Skálová T, Kalousková B, et al.: Structure of the human NK cell NKR-P1:LLT1 receptor:ligand complex reveals clustering in the immune synapse. Nat Commun 13: 5022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald KA and Kagan JC: Toll-like Receptors and the Control of Immunity. Cell 180: 1044–1066, 2020.

- Shah K, Al-Haidari A, Sun J and Kazi JU: T cell receptor (TCR) signaling in health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther 6: 412, 2021.

- Wilfahrt D and Delgoffe GM: Metabolic waypoints during T cell differentiation. Nat Immunol 25: 206–217, 2024.

- Liu X, Berry CT, Ruthel G, et al.: T Cell Receptor-induced Nuclear Factor κB (NF-κB) Signaling and Transcriptional Activation Are Regulated by STIM1- and Orai1-mediated Calcium Entry. J Biol Chem 291: 8440–8452, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Schulze-Luehrmann J and Ghosh S: Antigen-receptor signaling to nuclear factor kappa B. Immunity 25: 701–715, 2006.

- Klinger B, Rausch I, Sieber A, et al.: Quantitative modeling of signaling in aggressive B cell lymphoma unveils conserved core network. PLoS Comput Biol 20: e1012488, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Satpathy S, Wagner SA, Beli P, et al.: Systems-wide analysis of BCR signalosomes and downstream phosphorylation and ubiquitylation. Molecular Systems Biology 11: 810, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Dong R, Aksel T, Chan W, Germain RN, Vale RD and Douglas SM: DNA origami patterning of synthetic T cell receptors reveals spatial control of the sensitivity and kinetics of signal activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118: e2109057118, 2021.

- Arimont M, Sun S-L, Leurs R, Smit M, de Esch IJP and de Graaf C: Structural Analysis of Chemokine Receptor–Ligand Interactions. J Med Chem 60: 4735–4779, 2017.

- Levi-Schaffer F and Mandelboim O: Inhibitory and Coactivating Receptors Recognising the Same Ligand: Immune Homeostasis Exploited by Pathogens and Tumours. Trends Immunol 39: 112–122, 2018.

- Kok F, Rosenblatt M, Teusel M, et al.: Disentangling molecular mechanisms regulating sensitization of interferon alpha signal transduction. Mol Syst Biol 16: e8955, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Hahn J and Edgar TF: Process Control Systems. In: Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology (Third Edition). Meyers RA (ed.) Academic Press, New York, pp111–126, 2003.

- Elliott SJ: 6 - Design and Performance of Feedback Controllers. In: Signal Processing for Active Control. Elliott SJ (ed.) Academic Press, London, pp271–327, 2001.

- Hubo M, Trinschek B, Kryczanowsky F, Tüttenberg A, Steinbrink K and Jonuleit H: Costimulatory Molecules on Immunogenic Versus Tolerogenic Human Dendritic Cells. Front Immunol 4, 2013.

- Mueller DL: Tuning the immune system: competing positive and negative feedback loops. Nat Immunol 4: 210–211, 2003.

- Shlomchik MJ, Craft JE and Mamula MJ: From T to B and back again: positive feedback in systemic autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol 1: 147–153, 2001. [CrossRef]

- Xiao K, Liu C, Tu Z, et al.: Activation of the NF-κB and MAPK Signaling Pathways Contributes to the Inflammatory Responses, but Not Cell Injury, in IPEC-1 Cells Challenged with Hydrogen Peroxide. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020: 5803639, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Liang K-C, Lee C-W, Lin W-N, Lin C-C, Wu C-B, Luo S-F and Yang C-M: Interleukin-1beta induces MMP-9 expression via p42/p44 MAPK, p38 MAPK, JNK, and nuclear factor-kappaB signaling pathways in human tracheal smooth muscle cells. J Cell Physiol 211: 759–770, 2007.

- Coudronniere N, Villalba M, Englund N and Altman A: NF-κB activation induced by T cell receptor/CD28 costimulation is mediated by protein kinase C-θ. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 97: 3394–3399, 2000.

- Huang W, Lin W, Chen B, et al.: NFAT and NF-κB dynamically co-regulate TCR and CAR signaling responses in human T cells. Cell Rep 42: 112663, 2023.

- Walker GT, Perez-Lopez A, Silva S, et al.: CCL28 modulates neutrophil responses during infection with mucosal pathogens. Elife 13: e78206, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd CM and Snelgrove RJ: Type 2 immunity: Expanding our view. Sci Immunol 3: eaat1604, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Sokol CL and Luster AD: The chemokine system in innate immunity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7: a016303, 2015.

- Seif F, Khoshmirsafa M, Aazami H, Mohsenzadegan M, Sedighi G and Bahar M: The role of JAK-STAT signaling pathway and its regulators in the fate of T helper cells. Cell Communication and Signaling 15: 23, 2017.

- Alexander WS and Hilton DJ: The role of suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins in regulation of the immune response. Annu Rev Immunol 22: 503–529, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Yan M, Sun Z, Zhang S, et al.: SOCS modulates JAK-STAT pathway as a novel target to mediate the occurrence of neuroinflammation: Molecular details and treatment options. Brain Research Bulletin 213: 110988, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hu X, li J, Fu M, Zhao X and Wang W: The JAK/STAT signaling pathway: from bench to clinic. Signal Transduct Target Ther 6: 402, 2021.

- Oeckinghaus A and Ghosh S: The NF-κB Family of Transcription Factors and Its Regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 1: a000034, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Guo Q, Jin Y, Chen X, et al.: NF-κB in biology and targeted therapy: new insights and translational implications. Sig Transduct Target Ther 9: 1–37, 2024.

- Downton P, Bagnall JS, England H, et al.: Overexpression of IκB⍺ modulates NF-κB activation of inflammatory target gene expression. Front Mol Biosci 10, 2023.

- Sanjabi S, Zenewicz LA, Kamanaka M and Flavell RA: Anti- and Pro-inflammatory Roles of TGF-β, IL-10, and IL-22 In Immunity and Autoimmunity. Curr Opin Pharmacol 9: 447–453, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Iyer SS and Cheng G: Role of Interleukin 10 Transcriptional Regulation in Inflammation and Autoimmune Disease. Crit Rev Immunol 32: 23–63, 2012.

- Al-Qahtani AA, Alhamlan FS and Al-Qahtani AA: Pro-Inflammatory and Anti-Inflammatory Interleukins in Infectious Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 9: 13, 2024.

- Ruach R, Yellinek S, Itskovits E, Deshe N, Eliezer Y, Bokman E and Zaslaver A: A negative feedback loop in the GPCR pathway underlies efficient coding of external stimuli. Mol Syst Biol 18: e10514, 2022.

- Reina A and Marshall JAR: Negative feedback may suppress variation to improve collective foraging performance. PLOS Computational Biology 18: e1010090, 2022.

- Kriegeskorte N and Douglas PK: Interpreting encoding and decoding models. Current opinion in neurobiology 55: 167, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Blanco Malerba S, Micheli A, Woodford M and Azeredo da Silveira R: Jointly efficient encoding and decoding in neural populations. PLoS Comput Biol 20: e1012240, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Makadia HK, Schwaber JS and Vadigepalli R: Intracellular Information Processing through Encoding and Decoding of Dynamic Signaling Features. PLOS Computational Biology 11: e1004563, 2015.

- Su J, Song Y, Zhu Z, Huang X, Fan J, Qiao J and Mao F: Cell–cell communication: new insights and clinical implications. Signal Transduct Target Ther 9: 196, 2024.

- Mobeen A and Ramachandran S: Modeling the post-translational modifications and its effects in the NF-κB pathway. 2020.02.13.947010, 2020.

- Liu J, Qian C and Cao X: Post-Translational Modification Control of Innate Immunity. Immunity 45: 15–30, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Sun X, Cao S, Mao C, Sun F, Zhang X and Song Y: Post-translational modifications of p65: state of the art. Front Cell Dev Biol 12, 2024.

- Sebban H, Yamaoka S and Courtois G: Posttranslational modifications of NEMO and its partners in NF-κB signaling. Trends in Cell Biology 16: 569–577, 2006.

- Chambers MJ, Scobell SB and Sadhu MJ: Systematic genetic characterization of the human PKR kinase domain highlights its functional malleability to escape a poxvirus substrate mimic. eLife 13: RP99575, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Vivier E and Malissen B: Innate and adaptive immunity: specificities and signaling hierarchies revisited. Nat Immunol 6: 17–21, 2005.

- Devenish LP, Mhlanga MM and Negishi Y: Immune Regulation in Time and Space: The Role of Local- and Long-Range Genomic Interactions in Regulating Immune Responses. Front Immunol 12, 2021.

- Martincuks A, Andryka K, Küster A, Schmitz-Van de Leur H, Komorowski M and Müller-Newen G: Nuclear translocation of STAT3 and NF-κB are independent of each other but NF-κB supports expression and activation of STAT3. Cell Signal 32: 36–47, 2017.

- Lee H, Herrmann A, Deng J, et al.: Persistently-activated Stat3 maintains constitutive NF-κB activity in tumors. Cancer Cell 15: 283–293, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Son M, Wang AG, Keisham B and Tay S: Processing stimulus dynamics by the NF-κB network in single cells. Exp Mol Med 55: 2531–2540, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jin S, Zhou F, Katirai F and Li P-L: Lipid Raft Redox Signaling: Molecular Mechanisms in Health and Disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 15: 1043–1083, 2011.

- Ruzzi F, Cappello C, Semprini MS, et al.: Lipid rafts, caveolae, and epidermal growth factor receptor family: friends or foes? Cell Communication and Signaling 22: 489, 2024.

- Natoli G and Ostuni R: Adaptation and memory in immune responses. Nat Immunol 20: 783–792, 2019.

- Salvador-Martínez I, Murga-Moreno J, Nieto JC, Alsinet C, Enard D and Heyn H: Adaptation in human immune cells residing in tissues at the frontline of infections. Nat Commun 15: 10329, 2024.

- Newman MEJ: The Structure and Function of Complex Networks. SIAM Rev 45: 167–256, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Allen CD, Okada T and Cyster JG: Germinal Center Organization and Cellular Dynamics. Immunity 27: 190–202, 2007.

- Ozulumba T, Montalbine AN, Ortiz-Cárdenas JE and Pompano RR: New tools for immunologists: models of lymph node function from cells to tissues. Front Immunol 14, 2023.

- Biram A, Davidzohn N and Shulman Z: T cell interactions with B cells during germinal center formation, a three-step model. Immunol Rev 288: 37–48, 2019.

- Stebegg M, Kumar SD, Silva-Cayetano A, Fonseca VR, Linterman MA and Graca L: Regulation of the Germinal Center Response. Front Immunol 9, 2018.

- Matz H and Dooley H: 450 million years in the making: mapping the evolutionary foundations of germinal centers. Front Immunol 14, 2023.

- HWANG JK, ALT FW and YEAP L-S: Related Mechanisms of Antibody Somatic Hypermutation and Class Switch Recombination. Microbiol Spectr 3: 10.1128/microbiolspec.MDNA3-0037–2014, 2015.

- Wang Y, Zhang S, Yang X, et al.: Mesoscale DNA feature in antibody-coding sequence facilitates somatic hypermutation. Cell 186: 2193-2207.e19, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Benitez-Cantos MS, Cano C, Cuadros M and Medina PP: Activation-induced cytidine deaminase causes recurrent splicing mutations in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Molecular Cancer 23: 42, 2024.

- Altan-Bonnet G, Mora T and Walczak AM: Quantitative Immunology for Physicists. 696567, 2019.

- Park C-S and Choi YS: How do follicular dendritic cells interact intimately with B cells in the germinal centre? Immunology 114: 2–10, 2005.

- El Shikh MEM and Pitzalis C: Follicular dendritic cells in health and disease. Front Immunol 3: 292, 2012.

- Papa I and Vinuesa CG: Synaptic Interactions in Germinal Centers. Front Immunol 9, 2018.

- Syeda MZ, Hong T, Huang C, Huang W and Mu Q: B cell memory: from generation to reactivation: a multipronged defense wall against pathogens. Cell Death Discov 10: 1–16, 2024.

- Choi J, Crotty S and Choi YS: Cytokines in Follicular Helper T Cell Biology in Physiologic and Pathologic Conditions. Immune Netw 24: e8, 2024.

- Weinstein JS, Herman EI, Lainez B, Licona-Limón P, Esplugues E, Flavell R and Craft J: Follicular helper T cells progressively differentiate to regulate the germinal center response. Nat Immunol 17: 1197–1205, 2016.

- Marijuán PC and Navarro J: The biological information flow: From cell theory to a new evolutionary synthesis. Biosystems 213: 104631, 2022.

- Dustin ML and Colman DR: Neural and immunological synaptic relations. Science 298: 785–789, 2002.

- Grakoui A, Bromley SK, Sumen C, Davis MM, Shaw AS, Allen PM and Dustin ML: The immunological synapse: a molecular machine controlling T cell activation. Science 285: 221–227, 1999.

- Perkins ML: Biological patterning in networks of interacting cells.

- Mitrophanov AY and Groisman EA: Positive feedback in cellular control systems. BioEssays 30: 542–555, 2008.

- Kim D, Kwon Y-K and Cho K-H: Coupled positive and negative feedback circuits form an essential building block of cellular signaling pathways. BioEssays 29: 85–90, 2007.

- Ecosystem Control and Feedback Systems. In: Ecological Engineering Design. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp202–221, 2011.

- Shi C, Li H and Zhou T: Architecture-dependent robustness in a class of multiple positive feedback loops. IET Systems Biology 7: 1–10, 2013.

- Xie J, Tato CM and Davis MM: How the immune system talks to itself: the varied role of synapses. Immunol Rev 251: 65–79, 2013.

- Haykin H and Rolls A: The neuroimmune response during stress: A physiological perspective. Immunity 54: 1933–1947, 2021.

- Ngo C, Garrec C, Tomasello E and Dalod M: The role of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) in immunity during viral infections and beyond. Cell Mol Immunol 21: 1008–1035, 2024.

- Calzada-Fraile D and Sánchez-Madrid F: Reprogramming dendritic cells through the immunological synapse: A two-way street. European Journal of Immunology 53: 2350393, 2023.

- Atkinson S and Williams P: Quorum sensing and social networking in the microbial world. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 6: 959–978, 2009.

- Scheidweiler D, Bordoloi AD, Jiao W, et al.: Spatial structure, chemotaxis and quorum sensing shape bacterial biomass accumulation in complex porous media. Nat Commun 15: 191, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Naoun AA, Raphael I and Forsthuber TG: Immunoregulation via Cell Density and Quorum Sensing-like Mechanisms: An Underexplored Emerging Field with Potential Translational Implications. Cells 11: 2442, 2022.

- Stranford S and Ruddle NH: Follicular dendritic cells, conduits, lymphatic vessels, and high endothelial venules in tertiary lymphoid organs: Parallels with lymph node stroma. Front Immunol 3, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Acton SE, Onder L, Novkovic M, Martinez VG and Ludewig B: Communication, construction, and fluid control: lymphoid organ fibroblastic reticular cell and conduit networks. Trends in Immunology 42: 782–794, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Steinman RM: The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Annu Rev Immunol 9: 271–296, 1991.

- Vroomans RMA, Marée AFM, Boer RJ de and Beltman JB: Chemotactic Migration of T Cells towards Dendritic Cells Promotes the Detection of Rare Antigens. PLOS Computational Biology 8: e1002763, 2012.

- Quintana A, Schwindling C, Wenning AS, Becherer U, Rettig J, Schwarz EC and Hoth M: T cell activation requires mitochondrial translocation to the immunological synapse. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104: 14418–14423, 2007.

- Zak DE, Tam VC and Aderem A: Systems-Level Analysis of Innate Immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 32: 547–577, 2014.

- Buonaguro L, Wang E, Tornesello ML, Buonaguro FM and Marincola FM: Systems biology applied to vaccine and immunotherapy development. BMC Syst Biol 5: 146, 2011.

- Zak DE and Aderem A: Systems integration of innate and adaptive immunity. Vaccine 33: 5241–5248, 2015.

- Lyu J, Narum DE, Baldwin SL, et al.: Understanding the development of tuberculous granulomas: insights into host protection and pathogenesis, a review in humans and animals. Front Immunol 15, 2024.

- Sholeye AR, Williams AA, Loots DT, Tutu van Furth AM, van der Kuip M and Mason S: Tuberculous Granuloma: Emerging Insights From Proteomics and Metabolomics. Front Neurol 13: 804838, 2022.

- Mayito J, Andia I, Belay M, Jolliffe DA, Kateete DP, Reece ST and Martineau AR: Anatomic and Cellular Niches for Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Latent Tuberculosis Infection. J Infect Dis 219: 685–694, 2019.

- Henriques J, Berenbaum F and Mobasheri A: Obesity-induced fibrosis in osteoarthritis: Pathogenesis, consequences and novel therapeutic opportunities. Osteoarthr Cartil Open 6: 100511, 2024.

- Niu C, Hu Y, Xu K, Pan X, Wang L and Yu G: The role of the cytoskeleton in fibrotic diseases. Front Cell Dev Biol 12: 1490315, 2024.

- Moretti L, Stalfort J, Barker TH and Abebayehu D: The interplay of fibroblasts, the extracellular matrix, and inflammation in scar formation. J Biol Chem 298: 101530, 2021.

- Krieg T, Abraham D and Lafyatis R: Fibrosis in connective tissue disease: the role of the myofibroblast and fibroblast-epithelial cell interactions. Arthritis Research & Therapy 9: S4, 2007.

- Fowell DJ and Kim M: The spatiotemporal control of effector T cell migration. Nat Rev Immunol 21: 582–596, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Schenkel JM and Pauken KE: Localization, tissue biology, and T cell state — implications for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol 23: 807–823, 2023.

- Crossley RM, Johnson S, Tsingos E, et al.: Modeling the extracellular matrix in cell migration and morphogenesis: a guide for the curious biologist. Front Cell Dev Biol 12, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Germain RN: The art of the probable: system control in the adaptive immune system. Science 293: 240–245, 2001.

- Kurakin A: The self-organizing fractal theory as a universal discovery method: the phenomenon of life. Theor Biol Med Model 8: 4, 2011.

- Simon AK, Hollander GA and McMichael A: Evolution of the immune system in humans from infancy to old age. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 282: 20143085, 2015.

- Netea MG, Schlitzer A, Placek K, Joosten LAB and Schultze JL: Innate and Adaptive Immune Memory: an Evolutionary Continuum in the Host’s Response to Pathogens. Cell Host Microbe 25: 13–26, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Marchal S, Choukér A, Bereiter-Hahn J, Kraus A, Grimm D and Krüger M: Challenges for the human immune system after leaving Earth. NPJ Microgravity 10: 106, 2024.

- He J, Cui H, Jiang G, Fang L and Hao J: Knowledge mapping of trained immunity/innate immune memory: Insights from two decades of studies. Hum Vaccin Immunother 20: 2415823, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Epigenetic control of innate and adaptive immune memory | Nature Immunology.

- Kim MY, Lee JE, Kim LK and Kim T: Epigenetic memory in gene regulation and immune response. BMB Rep 52: 127–132, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Sun S and Barreiro LB: The epigenetic encoded memory of the innate immune system. Curr Opin Immunol 65: 7–13, 2020.

- Sun JC, Ugolini S and Vivier E: Immunological memory within the innate immune system. The EMBO Journal 33: 1295–1303, 2014.

- Ochando J, Mulder WJM, Madsen JC, Netea MG and Duivenvoorden R: Trained immunity — basic concepts and contributions to immunopathology. Nat Rev Nephrol 19: 23–37, 2023.

- Vuscan P, Kischkel B, Joosten LAB and Netea MG: Trained immunity: General and emerging concepts. Immunological Reviews 323: 164–185, 2024.

- Netea MG, Domínguez-Andrés J, Barreiro LB, et al.: Defining trained immunity and its role in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 20: 375–388, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Hajishengallis G and Chavakis T: DEL-1-Regulated Immune Plasticity and Inflammatory Disorders. Trends Mol Med 25: 444–459, 2019.

- Hikosaka M, Kawano T, Wada Y, Maeda T, Sakurai T and Ohtsuki G: Immune-Triggered Forms of Plasticity Across Brain Regions. Front Cell Neurosci 16, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Martin LB, Hanson HE, Hauber ME and Ghalambor CK: Genes, Environments, and Phenotypic Plasticity in Immunology. Trends in Immunology 42: 198–208, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ratnasiri K, Zheng H, Toh J, et al.: Systems immunology of transcriptional responses to viral infection identifies conserved antiviral pathways across macaques and humans. Cell Reports 43: 113706, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Grossman Z: Immunological Paradigms, Mechanisms, and Models: Conceptual Understanding Is a Prerequisite to Effective Modeling. Front Immunol 10, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Delplace F, Huard-Chauveau C, Berthomé R and Roby D: Network organization of the plant immune system: from pathogen perception to robust defense induction. The Plant Journal 109: 447–470, 2022.

- Artime O, Grassia M, De Domenico M, et al.: Robustness and resilience of complex networks. Nat Rev Phys 6: 114–131, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bery AI, Shepherd HM, Li W, Krupnick AS, Gelman AE and Kreisel D: Role of tertiary lymphoid organs in the regulation of immune responses in the periphery. Cell Mol Life Sci 79: 359, 2022.

- Jones GW, Hill DG and Jones SA: Understanding Immune Cells in Tertiary Lymphoid Organ Development: It Is All Starting to Come Together. Front Immunol 7, 2016.

- Alcalá-Corona SA, Sandoval-Motta S, Espinal-Enríquez J and Hernández-Lemus E: Modularity in Biological Networks. Front Genet 12, 2021.

- Kadelka C, Wheeler M, Veliz-Cuba A, Murrugarra D and Laubenbacher R: Modularity of biological systems: a link between structure and function. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 20: 20230505, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Novkovic M, Onder L, Cupovic J, et al.: Topological Small-World Organization of the Fibroblastic Reticular Cell Network Determines Lymph Node Functionality. PLoS Biol 14: e1002515, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Wang G and Yao W: An application of small-world network on predicting the behavior of infectious disease on campus. Infectious Disease Modelling 9: 177–184, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed E and Hashish AH: On modelling the immune system as a complex system. Theory Biosci 124: 413–418, 2006.

- Marin I and Kipnis J: Learning and memory ... and the immune system. Learn Mem 20: 601–606, 2013.

- Pappalardo F, Russo G and Reche PA: Toward computational modelling on immune system function. BMC Bioinformatics 21: 546, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Clark A and Rivas F: A learning experience. Trends Neurosci 38: 583–584, 2015.

- Jin H, Li M, Jeong E, Castro-Martinez F and Zuker CS: A body–brain circuit that regulates body inflammatory responses. Nature 630: 695–703, 2024.

- Cohen N: Bidirectional communication between the central nervous system (CNS) and the immune system. Dev Comp Immunol 15: 209–210, 1991. [CrossRef]

- Marques-Deak A, Cizza G and Sternberg E: Brain-immune interactions and disease susceptibility. Mol Psychiatry 10: 239–250, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Haddad JJ: On the mechanisms and putative pathways involving neuroimmune interactions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 370: 531–535, 2008.

- Ramos Meyers G, Samouda H and Bohn T: Short Chain Fatty Acid Metabolism in Relation to Gut Microbiota and Genetic Variability. Nutrients 14: 5361, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Sasso JM, Ammar RM, Tenchov R, Lemmel S, Kelber O, Grieswelle M and Zhou QA: Gut Microbiome–Brain Alliance: A Landscape View into Mental and Gastrointestinal Health and Disorders. ACS Chem Neurosci 14: 1717–1763, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Majumdar A, Siva Venkatesh IP and Basu A: Short-Chain Fatty Acids in the Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis: Role in Neurodegenerative Disorders and Viral Infections. ACS Chem Neurosci 14: 1045–1062, 2023.

- Siva Venkatesh IP, Majumdar A and Basu A: Prophylactic Administration of Gut Microbiome Metabolites Abrogated Microglial Activation and Subsequent Neuroinflammation in an Experimental Model of Japanese Encephalitis. ACS Chem Neurosci 15: 1712–1727, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Pavlov VA and Tracey KJ: The vagus nerve and the inflammatory reflex—linking immunity and metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol 8: 743–754, 2012.

- Krsek A and Baticic L: Neutrophils in the Focus: Impact on Neuroimmune Dynamics and the Gut–Brain Axis. Gastrointestinal Disorders 6: 557–606, 2024.

- Liu F-J, Wu J, Gong L-J, Yang H-S and Chen H: Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation in anti-inflammatory therapy: mechanistic insights and future perspectives. Front Neurosci 18, 2024.

- Warren A, Nyavor Y, Zarabian N, Mahoney A and Frame LA: The microbiota-gut-brain-immune interface in the pathogenesis of neuroinflammatory diseases: a narrative review of the emerging literature. Front Immunol 15: 1365673, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Szentirmai É, Buckley K, Massie AR and Kapás L: Lipopolysaccharide-mediated effects of the microbiota on sleep and body temperature. Sci Rep 14: 27378, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Munteanu C, Galaction AI, Turnea M, Blendea CD, Rotariu M and Poștaru M: Redox Homeostasis, Gut Microbiota, and Epigenetics in Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Systematic Review. Antioxidants (Basel) 13: 1062, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Montagnani M, Bottalico L, Potenza MA, Charitos IA, Topi S, Colella M and Santacroce L: The Crosstalk between Gut Microbiota and Nervous System: A Bidirectional Interaction between Microorganisms and Metabolome. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24: 10322, 2023.

- Domagala-Kulawik J, Osinska I and Hoser G: Mechanisms of immune response regulation in lung cancer. Translational Lung Cancer Research 3: 15, 2014.

- Carbone DP, Gandara DR, Antonia SJ, Zielinski C and Paz-Ares L: Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer: Role of the Immune System and Potential for Immunotherapy. J Thorac Oncol 10: 974–984, 2015.

- Liu Z, Chen J, Ren Y, et al.: Multi-stage mechanisms of tumor metastasis and therapeutic strategies. Signal Transduct Target Ther 9: 270, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hu A, Sun L, Lin H, Liao Y, Yang H and Mao Y: Harnessing innate immune pathways for therapeutic advancement in cancer. Sig Transduct Target Ther 9: 1–59, 2024.

- Shi X, Wang X, Yao W, et al.: Mechanism insights and therapeutic intervention of tumor metastasis: latest developments and perspectives. Signal Transduct Target Ther 9: 192, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Xia L, Oyang L, Lin J, et al.: The cancer metabolic reprogramming and immune response. Mol Cancer 20: 28, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Liu M, Liu H and Chen J: Tumor metabolic reprogramming in lung cancer progression. Oncol Lett 24: 287, 2022.

- Liao M, Yao D, Wu L, Luo C, Wang Z, Zhang J and Liu B: Targeting the Warburg effect: A revisited perspective from molecular mechanisms to traditional and innovative therapeutic strategies in cancer. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 14: 953–1008, 2024.

- Tufail M, Jiang C-H and Li N: Altered metabolism in cancer: insights into energy pathways and therapeutic targets. Molecular Cancer 23: 203, 2024.

- Nong S, Han X, Xiang Y, et al.: Metabolic reprogramming in cancer: Mechanisms and therapeutics. MedComm 4: e218, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Biswas D and Swanton C: Impact of cancer evolution on immune surveillance and checkpoint inhibitor response. Seminars in Cancer Biology 84: 89, 2022.

- Cha J-H, Chan L-C, Li C-W, Hsu JL and Hung M-C: Mechanisms controlling PD-L1 expression in cancer. Mol Cell 76: 359–370, 2019.

- Thol K, Pawlik P and McGranahan N: Therapy sculpts the complex interplay between cancer and the immune system during tumour evolution. Genome Medicine 14: 137, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lei Q, Wang D, Sun K, Wang L and Zhang Y: Resistance Mechanisms of Anti-PD1/PDL1 Therapy in Solid Tumors. Front Cell Dev Biol 8, 2020. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).