Submitted:

14 January 2025

Posted:

15 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

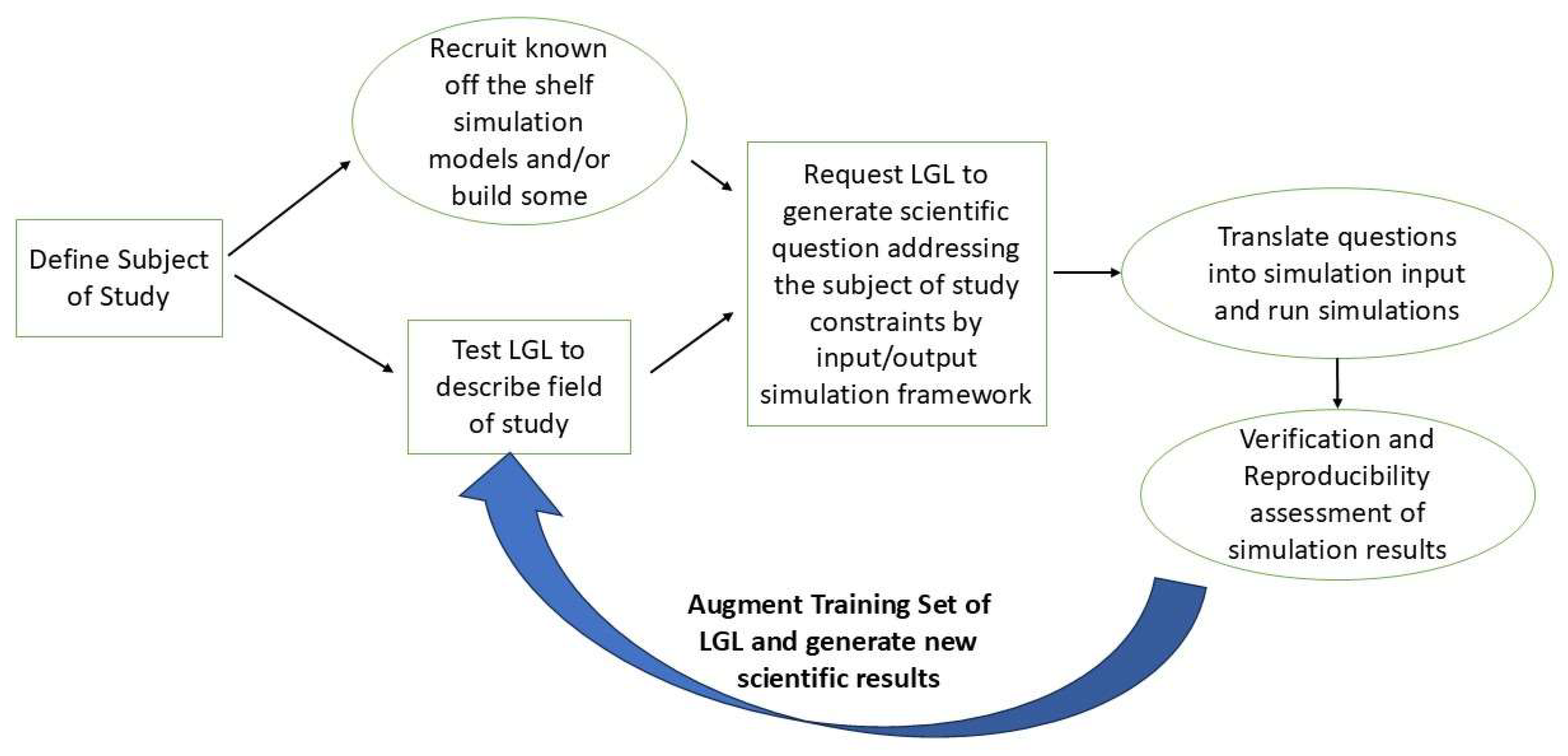

We hypothesize that large language models (LLMs) can effectively generate 'thought experiments' that can be evaluated using virtual simulators. This approach has the potential to automate knowledge generation, accelerate scientific discovery, and provide a systematic method for training subsequent LLMs with verifiable and reproducible datasets. To illustrate this concept, we will use the clinical workflow optimization challenge as a case study.

Keywords:

Introduction

Method

- (i).

- is not trivial and/or can be tuned to an increasing level of complexity.

- (i).

- has practical value.

- (i).

- is understood mathematically to some level.

- (i).

- gives some hint on how to generalize the concept.

- Frequency of patient arrival

- Number of Phases

- Mean and standard deviation of the normal distribution of elapse time of task processing for each phase

- Capacity of the facility to set how many patients can be processed in parallel for each phase.

- Global: throughput, and efficiency,

- Patient specific: waiting time in queue,

-

Focusing on a specific phase of the process:

- o elapse time per task per stage

- o hidden time between tasks at each stage

- (1)

- pseudo mathematical formulation: can you edit the formulation of the following problem please:

- (2)

- What is the solution to that problem, please?

- (3)

- Please provide ten meaningful scientific questions for a single-channel multiple-phase queueing system.

- (4)

- Is there a mathematical model of a single-channel multiple-phase queueing system?

- (5)

- What can go wrong in a clinical facility that can be modeled as a single-channel multiple-phase queue?

- (6)

- We consider a single-channel multiple-phase queue model of a clinic workflow, which can be modeled with the following parameters: frequency of patient arrival (F), number of phases in patient treatment, normal distribution parameters of processing time at each phase, capacity of the clinic for each phase, i.e., the number of patients that can be handled in parallel for each phase. Please formulate 10 interesting questions to explore the performance of the system using these parameters.

- (7)

- Please answer these questions in the same order.

- (8)

- Are there new challenges in understanding how single-channel multiple-phase models work?

- (9)

- What are the questions that are often overlooked when one attempts to optimize a single-channel multiphase queueing process?"

Result

Discussion

Technology Standpoint

Epistemology Standpoint

Some Grand Challenges to Come

- Open question in quantum physic using simulation of particle collider [https://pythia.org/] or [https://herwig.hepforge.org/] ?

- What can go wrong in critical human space exploration mission using a digital twin of a mission to Mars that would be verified and validated?

- How ecosystem would be affected by various scenario of global climate modeling using stochastic agent base model in ecology of population?

Conclusion

Appendix A. Element of a Conversation with Gemini

- A.1. Optimal Phase Sequencing:

- A.2. Phase Capacity and Bottlenecks:

- A.3. Customer Routing and Prioritization:

- A.4. Balking and Reneging:

- A.5. Bulk Arrivals and Departures:

- A.6. Phase-Dependent Service Times:

- A.7. Non-Markovian Arrivals and Departures:

- A.8. Finite Buffer Systems:

- A.9. System Stability and Transient Behavior:

- A.10. Applications and Case Studies:

- Overcrowding and Long Wait Times:

- Priority Mismanagement:

- Phase-Dependent Bottlenecks:

- Inefficient Resource Allocation:

- Poor Patient Experience:

- Staff Burnout:

- General Performance Questions:

- Phase-Specific Questions:

- Capacity-Related Questions:

- Arrival and Service Time Questions:

- Model Complexity:

- 2.

- Real-World Variations:

- 3.

- Data Limitations:

- 4.

- Dynamic Environments:

- 5.

- Computational Challenges:

-

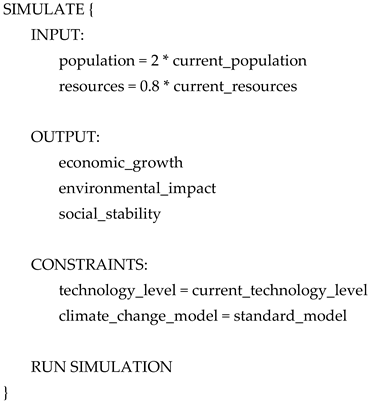

Identify the Core Variables:

- o Input Variables: These are the factors that can be manipulated in the simulation.

- o Output Variables: These are the outcomes or results we want to observe.

- o Constraints and Assumptions: These are the limitations or conditions that define the simulation environment.

-

Define the Experiment's Goal:

- o What is the specific question or hypothesis we want to test?

- o What kind of insights or predictions do we hope to gain?

-

Translate the Question into a Formal Query:

- o Formal Language: Use a formal language or scripting language that the simulation engine can interpret.

- o Structured Query: Break down the question into a series of statements and conditions.

- Simulation Engine Capabilities: The specific format and complexity of the query will depend on the capabilities of the simulation engine.

- Data and Models: Ensure that the simulation engine has access to the necessary data and models to accurately represent the real-world system.

- Validation and Calibration: Validate the simulation results against real-world data to ensure accuracy and reliability.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Conduct sensitivity analysis to understand how changes in input variables affect the output variables.

- Experiment: Simulate a system where service times for each patient are drawn from a distribution (e.g., exponential, normal) rather than being fixed.

- Question: How does variability in service times impact waiting times, queue length, and overall system performance?

- Goal: Identify optimal strategies for managing variable service times, such as flexible staffing or priority queuing systems.

- Experiment: Implement a priority-based queuing system where patients are assigned priorities based on urgency (e.g., critical, urgent, routine).

- Question: How does priority-based queuing affect waiting times for different patient categories and overall system efficiency?

- Goal: Develop strategies for prioritizing patients effectively to minimize wait times and improve patient satisfaction.

- Experiment: Model a system where multiple patients are processed together in batches (e.g., group therapy sessions, lab tests).

- Question: How does batch service impact system performance, particularly in terms of utilization and waiting times?

- Goal: Identify optimal batch sizes and scheduling strategies to maximize efficiency and minimize patient wait times.

- Experiment: Incorporate patient abandonment into the model, where patients may leave the queue if their wait time exceeds a certain threshold.

- Question: How does patient abandonment affect system performance, and what strategies can be implemented to reduce abandonment rates?

- Goal: Develop strategies to improve patient satisfaction and reduce lost opportunities.

- Experiment: Model a system with multiple service phases (e.g., triage, consultation, treatment).

- Question: How does the sequence and duration of service phases impact overall system performance?

- Goal: Identify bottlenecks and opportunities for improvement in multi-phase workflows.

References

- Radford, A., Narasimhan, K., Salimans, T., & Sutskever, I. (2018). Improving language understanding by generative pre-training.

- Ziwei Ji, Survey of Hallucination in Natural Language Generation, https://arxiv.org/pdf/2202.03629.

- National Research Council (2014) Convergence: Facilitating Transdisciplinary Integration of Life Sciences, Physical Sciences, Engineering, and Beyond. National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.

- Hubert, K.F., Awa, K.N. & Zabelina, D.L. The current state of artificial intelligence generative language models is more creative than humans on divergent thinking tasks. Sci Rep 14, 3440 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Lamb, David; Easton, S. M. (1984). "Originality in art and science [chap. 9]". Multiple Discovery: The Pattern of Scientific Progress. Amersham: Avebury Publishing. ISBN 978-0861270255.

- Lei Huang, Weijiang .Yu, Weito Ma, et Al, A Survey on Hallucination in Large Language Models: Principles, Taxonomy, Challenges, and Open Questions, ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. [CrossRef]

- Gendler TS. Thought Experiments Rethought—and Reperceived. Philosophy of Science. 2004;71(5):1152-1163. [CrossRef]

- Peter J Denning, Computational Thinking in Science, American Scientist, January-February 2017, Volume 105, Number 1, Page 13. [CrossRef]

- Ivo Babuska, J.Tinsley Oden, Verification and validation in computational engineering and science: basic concepts, Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, Volume 193, Issues 36–38, 2004, Pages 4057-4066, ISSN 0045-7825, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cma.2004.03.002.

- The Rise of Digital Twins, Nature Computational Science 26 March 2024.

- Cookson NA, Mather WH, Danino T, Mondragón-Palomino O, Williams RJ, Tsimring LS, Hasty J. Queueing up for enzymatic processing: correlated signaling through coupled degradation. Mol Syst Biol. 2011 Dec 20;7:561. PMID: 22186735; PMCID: PMC3737734. [CrossRef]

- Shi C, Jiang Y, Zhou T. Queuing Models of Gene Expression: Analytical Distributions and Beyond. Biophys J. 2020 Oct 20;119(8):1606-1616. Epub 2020 Sep 9. PMID: 32966761; PMCID: PMC7642270. [CrossRef]

- Sylwester Kloska, Krzysztof Pałczyński, Tomasz Marciniak, Tomasz Talaśka, Marissa Nitz, Beata J Wysocki, Paul Davis, Tadeusz A Wysocki, Queueing theory model of Krebs cycle, Bioinformatics, Volume 37, Issue 18, September 2021, Pages 2912–2919. [CrossRef]

- Adrian Furnham , Luke Treglown, George Horne, The Psychology of Queuing, Psychology, 2020, 11, 480-498 https://www.scirp.org/journal/psych ISSN Online: 2152-7199 ISSN Print: 2152-7180.

- A. Y. Huang, G. Joerger, R. Salmon, B. J. Dunkin, V. Sherman, B. L. Bass, and M. Garbey, A Robust and Non Obstrusive Automatic Event Tacking System for Operating Room Management to Improve Patient care Journal of Surgical Endoscopy,August 2016. [CrossRef]

- Marc Garbey, Guillaume Joerger, Juliette Rambour, Brian Dunkin and Barbara Bass, Multiscale Modeling of Surgical Flow in a Large Operating Room Suite: Understanding the Mechanism of Accumulation of Delays in Clinical Practice, Procedia Computer Science 108, 1863-1872, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Marc Garbey, Guillaume Joerger, Shannon Furr, A Model of Workflow in the Hospital During a Pandemic to Assist Management, Plos One, November 30, 2020. Volume 30, Issue 8, pp 3638-3645, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Marc Garbey, Guillaume Joerger, Shannon Furr, Application of Digital Twin and Heuristic Computer Reasoning to Workflow Management: Gastroenterology Outpatient Centers Stud,. Journal of Surgery and Research. 6 (2023): 104-129. [CrossRef]

- J.G.C. Templeton, G.I. Falin, Retrial Queues , Chapman & Hall/CRC Monographs on Statistics and Applied Probability) 1st Edition, 1997.

- Eniola Ezekiel, Theory and Practice of Queuing System, Independently published, July 29, 2022 · ISBN-13. 979-8842995080.

- Yeates LB. Thought Experimentation: A Cognitive Approach, Graduate Diploma in Arts (By Research) Dissertation, University of New South Wales (2004).

- M.Garbey, G.Joeger and H.Kaminsky, Self-Assessment Neurological Health Care System,.

- PCT/US24/41422.

- Iman Mirzadeh, Keivan Alizadeh, Hooman Shahrokhi, Oncel Tuzel, Samy Bengio , Mehrdad Farajtabar, GSM-Symbolic: Understanding the Limitations of Mathematical Reasoning in Large Language Models, arXiv:2410.05229v1, 7 Oct 2024. [CrossRef]

- Radosvet Desislavov, Fernando Martínez-Plumed, José Hernández-Orallo, Trends in AI inference energy consumption: Beyond the performance-vs-parameter laws of deep learning, Sustainable Computing: Informatics and Systems, Volume 38, 2023, 100857, ISSN 2210-5379, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suscom.2023.100857.

- Socol Y, Shaki YY, Yanovskiy M. Interests, Bias, and Consensus in Science and Regulation. Dose Response. 2019 Jun 5;17(2):1559325819853669. PMID: 31217756; PMCID: PMC6557026. [CrossRef]

- Barrio JR. Consensus science and the peer review. Mol Imaging Biol. 2009 Sep-Oct;11(5):293. PMID: 19399558; PMCID: PMC2719747. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).