Submitted:

14 January 2025

Posted:

15 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

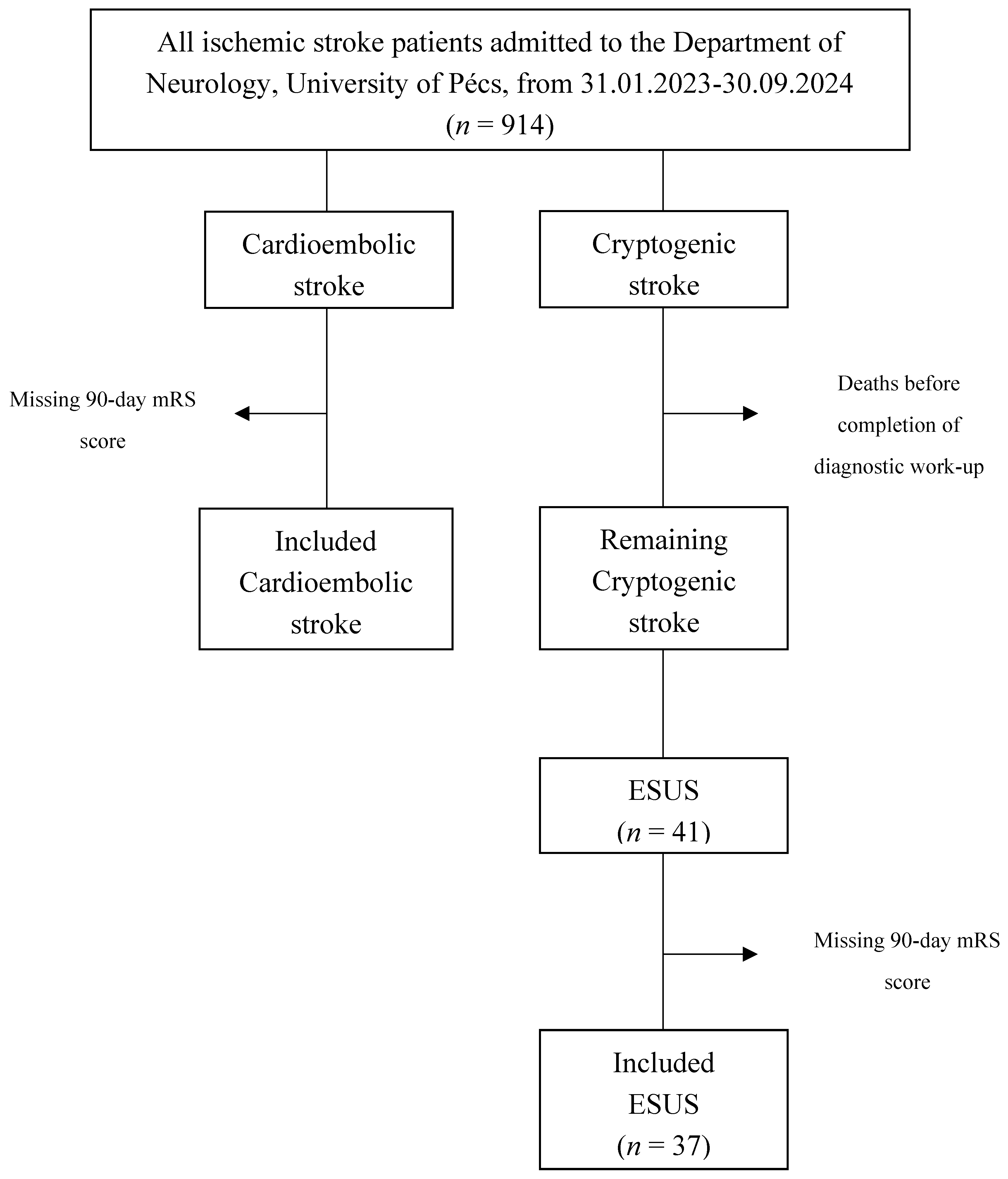

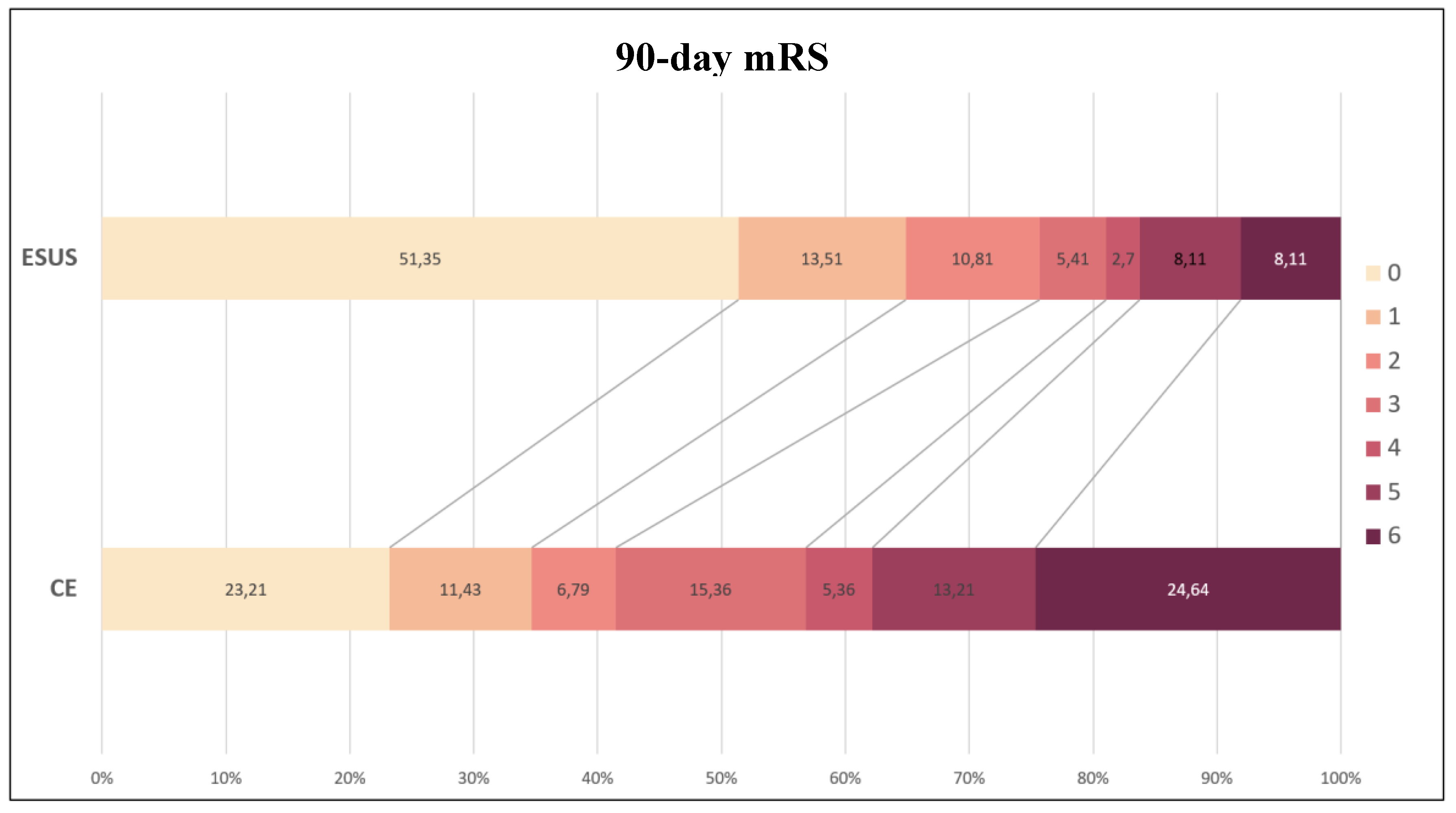

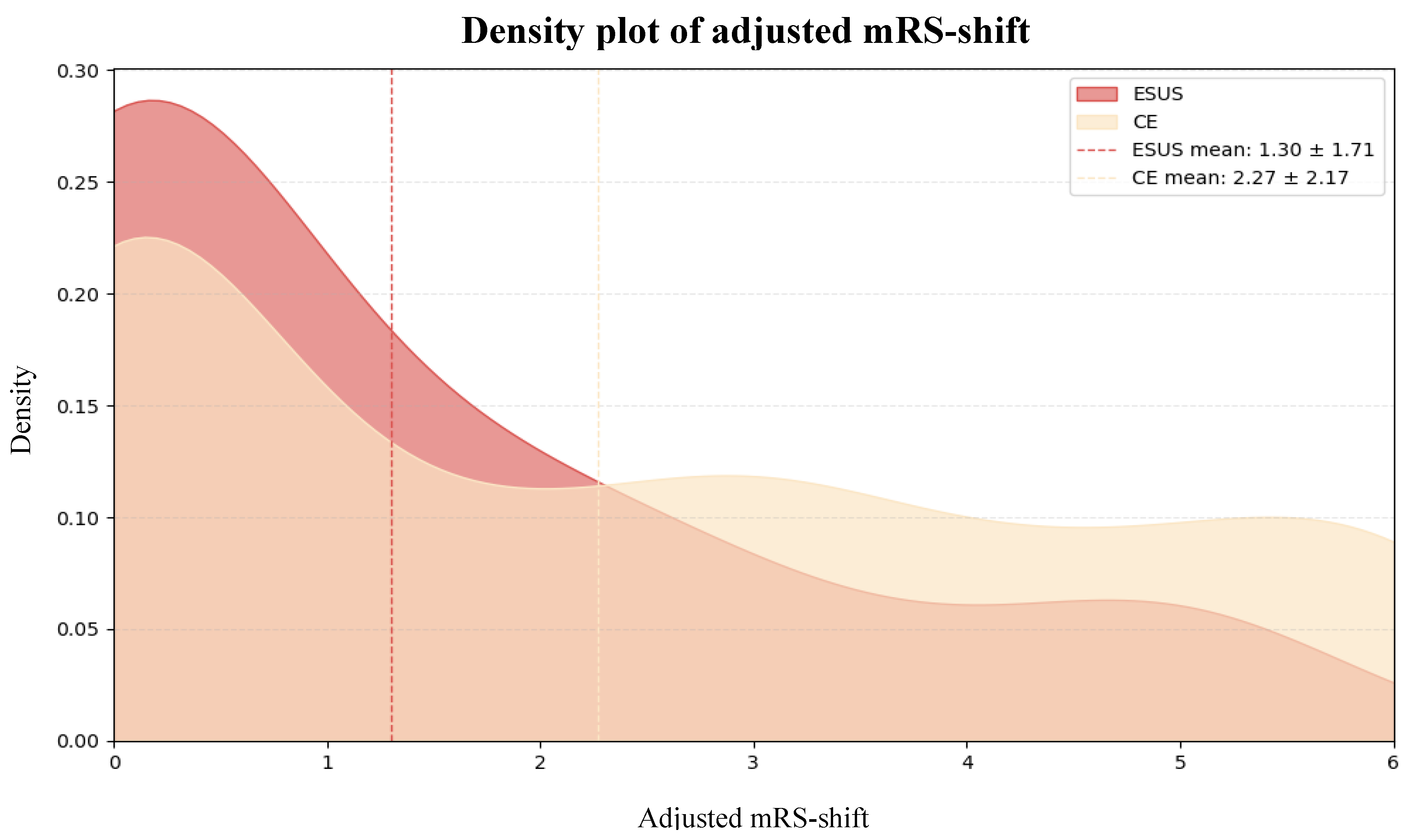

Background/Objectives: Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source (ESUS) is a subtype of ischemic stroke characterized by a non-lacunar infarct in the absence of a clearly identifiable embolic source, despite comprehensive diagnostic evaluation. While ESUS patients are typically younger, have fewer cardiovascular comorbidities, and experience milder strokes than those with cardioembolic strokes (CE), their long-term functional recovery remains underexplored. Methods: We retrospectively analyzed data from 317 ischemic stroke patients (n = 37 ESUS, n = 280 CE) admitted to the Department of Neurology, University of Pécs, between February 2023 and September 2024. Functional recovery was assessed using the modified Rankin Scale (mRS), adjusted for baseline differences (adjusted mRS-shift). Independent predictors of mRS-shift were identified using Firth penalized regression and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost). Results: ESUS patients were significantly younger (53.8 ± 13.5 years vs. 75.1 ± 11.3 years, p <0.001), had lower pre-morbid modified Rankin Scale (pre-mRS) scores (0.22 ± 0.75 vs. 0.81 ± 1.23, p <0.001), were less likely to have hypertension (70.3% vs. 86.1%, p = 0.027), and presented with milder strokes at admission (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] score 5.5 ± 3.6 vs. 8.1 ± 6.3, p <0.001) and 72 hours post-stroke (2.8 ± 3.7 vs. 6.5 ± 6.3, p <0.001) compared to CE patients. After adjusting for baseline differences, ESUS patients had significantly better functional recovery (adjusted mRS-shift 1.30 ± 1.71 vs. 2.27 ± 2.17, p <0.001). Conclusions: ESUS patients showed superior functional recovery compared to CE patients, even after adjusting for baseline differences. These findings highlight the need for further research into the pathophysiology and optimal treatment for ESUS.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Population

2.2. Definitions

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Outcome Measure

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Differences

| ESUS n = 37 | CE n = 280 | p-Value | |

| Baseline Characteristics | |||

| Age, years, mean (SD) Sex, male, n (%) Pre-mRS score, mean (SD) Hypertension, n (%) Diabetes mellitus, n (%) Current smoking, n (%) Alcohol consumption, n (%) Anticoagulation, n (%) |

53.8 (± 13.5) 20 (54.1%) 0.22 (± 0.75) 26 (70.3%) 9 (24.3%) 12 (32.4%) 18 (48.6%) 5 (13.5%) |

75.1 (± 11.3) 150 (53.6%) 0.81 (± 1.23) 241 (86.1%) 103 (36.8%) 47 (16.8%) 117 (41.8%) 102 (36.4%) |

<0.001* 1.00 <0.001* 0.027 0.148 0.040 0.481 0.005 |

| Stroke Characteristics | |||

| Onset-door-time, mean (SD) NIHSS score, mean (SD) 72hNIHSS score, mean (SD) Plasma-glucose, mean (SD) INR, mean (SD) |

360 (455) 5.5 (± 3.6) 2.8 (± 3.7) 7.46 (± 2.98) 1.13 (± 0.50) |

590 (± 1860) 8.1 (± 6.3) 6.5 (± 6.3) 7.51 (± 2.59) 1.21 (± 0.63) |

0.087 <0.001* <0.001* 0.925 0.394 |

| Treatment Modalities | |||

| SC, n (%) TL, n (%) MT, n (%) TL + MT, n (%) |

12 (32.4%) 13 (35.1%) 8 (21.6%) 4 (10.8%) |

133 (47.5%) 54 (19.3%) 65 (23.2%) 28 (10.0%) |

0.113 0.033 1.00 0.777 |

3.2. Functional Recovery

3.3. Subgroup Analyses

Anticoagulation Status

Treatment Modalities

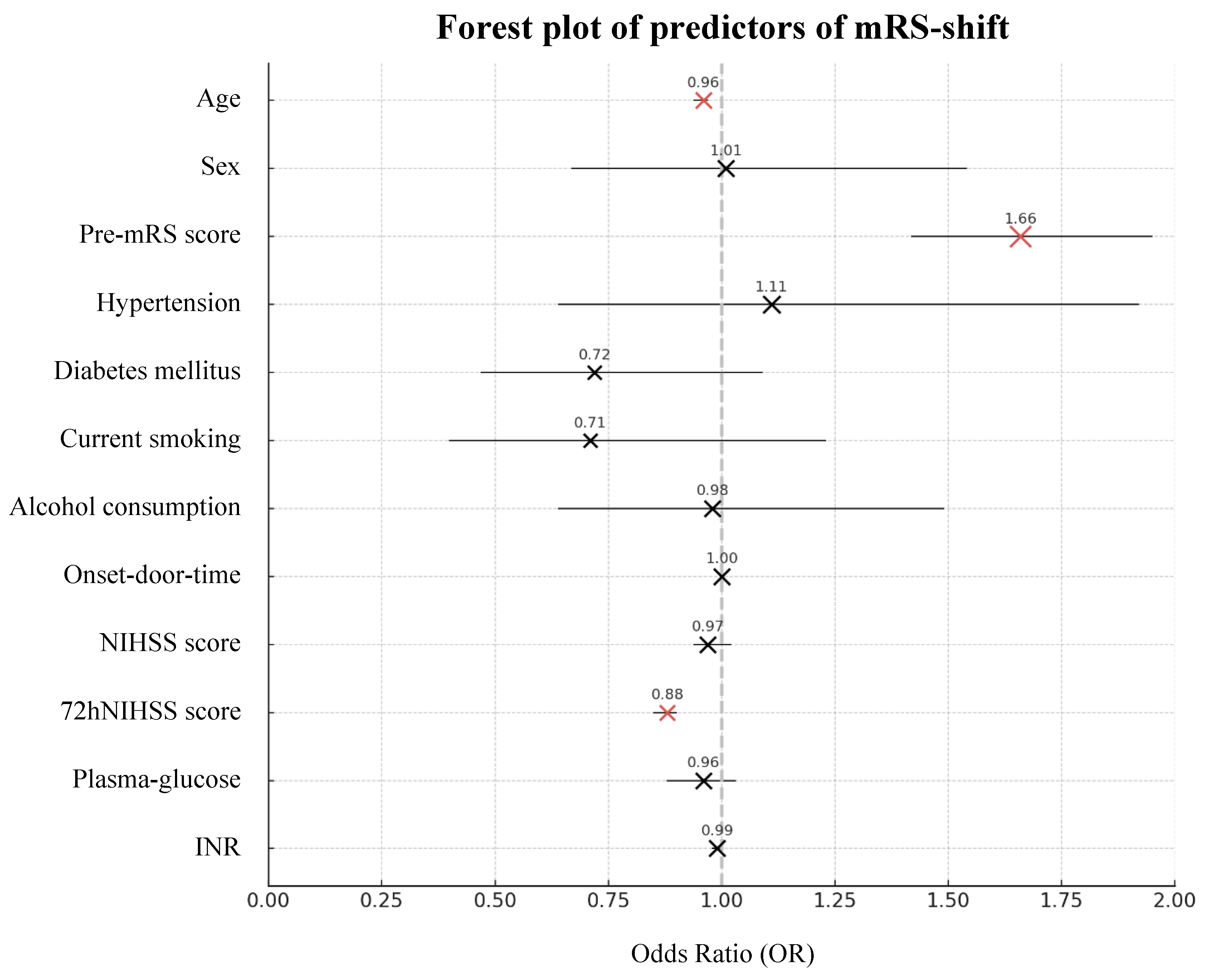

3.4. Predictors of Functional Recovery

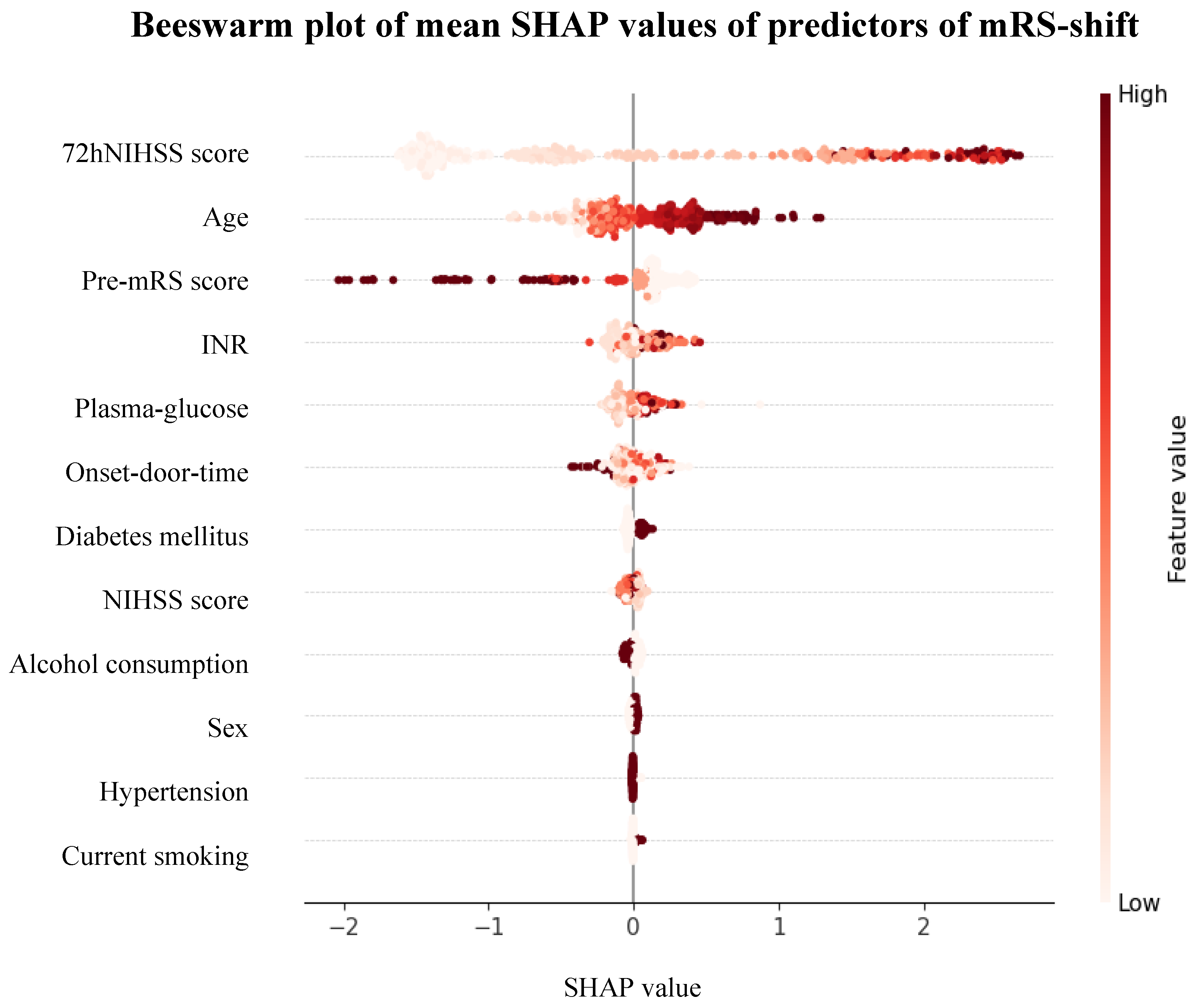

Firth Regression and XGBoost

Model Performance

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Age on Neuroplasticity and Recovery

4.2. Stroke Pathophysiology and Infarct Patterns

4.3. Complexity of Embolic Sources and Treatment Implications

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

List of Abbreviations

| ESUS | embolic stroke of undetermined source |

| CE | cardioembolic stroke |

| mRS | modified Rankin Scale |

| XGBoost | extreme gradient boosting |

| pre-mRS | pre-morbid modified Rankin Scale |

| NIHSS | National Institues of Health Stroke Scale |

| AF | atrial fibrillation |

| TINL | Transzlációs Idegtudományi Nemzeti Laboratórium |

| AIS | acute ischemic stroke |

| CTA | computed tomography angiography |

| MRA | magnetic resonance angiography |

| TTE | transthoracic echocardiography |

| MRT | magnetic resonance tomography |

| INR | international normalized ratio |

| SC | standard care |

| TL | thrombolysis |

| MT | mechanical thrombectomy |

| NCCT | non-contrast computed tomography |

| ECG | electrocardiogram |

| TEE | transesophageal echocardiography |

| SD | standard deviation |

| χ2 | chi-quare |

| OR | odds ratio |

| CI | confidence interval |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| df | degrees of freedom |

| PFO | patent foramen ovale |

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feigin, V.L.; Brainin, M.; Norrving, B.; Martins, S.O.; Pandian, J.; Lindsay, P.; F Grupper, M.; Rautalin, I. World Stroke Organization: Global Stroke Fact Sheet 2025. International Journal of Stroke 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamel, H.; Healey, J.S. Cardioembolic Stroke. Circ Res 2017, 120, 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntaios, G. Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020, 75, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Majander, N.; Aarnio, K.; Pirinen, J.; Lumikari, T.; Nieminen, T.; Lehto, M.; Sinisalo, J.; Kaste, M.; Tatlisumak, T.; Putaala, J. Embolic Strokes of Undetermined Source in Young Adults: Baseline Characteristics and Long-term Outcome. Eur J Neurol 2018, 25, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntaios, G.; Papavasileiou, V.; Milionis, H.; Makaritsis, K.; Manios, E.; Spengos, K.; Michel, P.; Vemmos, K. Embolic Strokes of Undetermined Source in the Athens Stroke Registry. Stroke 2015, 46, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Yiin, G.S.; Geraghty, O.C.; Schulz, U.G.; Kuker, W.; Mehta, Z.; Rothwell, P.M. Incidence, Outcome, Risk Factors, and Long-Term Prognosis of Cryptogenic Transient Ischaemic Attack and Ischaemic Stroke: A Population-Based Study. Lancet Neurol 2015, 14, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putaala, J.; Nieminen, T.; Haapaniemi, E.; Meretoja, A.; Rantanen, K.; Heikkinen, N.; Kinnunen, J.; Strbian, D.; Mustanoja, S.; Curtze, S.; et al. Undetermined Stroke with an Embolic Pattern—a Common Phenotype with High Early Recurrence Risk. Ann Med 2015, 47, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntaios, G.; Papavasileiou, V.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Milionis, H.; Makaritsis, K.; Vemmou, A.; Koroboki, E.; Manios, E.; Spengos, K.; Michel, P.; et al. Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source and Detection of Atrial Fibrillation on Follow-Up: How Much Causality Is There? Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases 2016, 25, 2975–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, R.G.; Sharma, M.; Mundl, H.; Kasner, S.E.; Bangdiwala, S.I.; Berkowitz, S.D.; Swaminathan, B.; Lavados, P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Rivaroxaban for Stroke Prevention after Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 378, 2191–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, H.-C.; Sacco, R.L.; Easton, J.D.; Granger, C.B.; Bar, M.; Bernstein, R.A.; Brainin, M.; Brueckmann, M.; Cronin, L.; Donnan, G.; et al. Antithrombotic Treatment of Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source. Stroke 2020, 51, 1758–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, H.; Longstreth, W.T.; Tirschwell, D.L.; Kronmal, R.A.; Marshall, R.S.; Broderick, J.P.; Aragón García, R.; Plummer, P.; Sabagha, N.; Pauls, Q.; et al. Apixaban to Prevent Recurrence After Cryptogenic Stroke in Patients With Atrial Cardiopathy. JAMA 2024, 331, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geisler, T.; Keller, T.; Martus, P.; Poli, K.; Serna-Higuita, L.M.; Schreieck, J.; Gawaz, M.; Tünnerhoff, J.; Bombach, P.; Nägele, T.; et al. Apixaban versus Aspirin for Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source. NEJM Evidence 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, R.G.; Diener, H.-C.; Coutts, S.B.; Easton, J.D.; Granger, C.B.; O’Donnell, M.J.; Sacco, R.L.; Connolly, S.J. Embolic Strokes of Undetermined Source: The Case for a New Clinical Construct. Lancet Neurol 2014, 13, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amarenco, P.; Bogousslavsky, J.; Caplan, L.R.; Donnan, G.A.; Wolf, M.E.; Hennerici, M.G. The ASCOD Phenotyping of Ischemic Stroke (Updated ASCO Phenotyping). Cerebrovascular Diseases 2013, 36, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brott, T.; Adams, H.P.; Olinger, C.P.; Marler, J.R.; Barsan, W.G.; Biller, J.; Spilker, J.; Holleran, R.; Eberle, R.; Hertzberg, V. Measurements of Acute Cerebral Infarction: A Clinical Examination Scale. Stroke 1989, 20, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsivgoulis, G.; Kargiotis, O.; Katsanos, A.H.; Patousi, A.; Mavridis, D.; Tsokani, S.; Pikilidou, M.; Birbilis, T.; Mantatzis, M.; Zompola, C.; et al. Incidence, Characteristics and Outcomes in Patients with Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source: A Population-Based Study. J Neurol Sci 2019, 401, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, E.S.J.; de Leon, J.; Boey, E.; Chin, H.-K.; Ho, K.-H.; Aguirre, S.; Sim, M.-G.; Seow, S.-C.; Sharma, V.K.; Kojodjojo, P. Stroke Recurrence in Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source Without Atrial Fibrillation on Invasive Cardiac Monitoring. Heart Lung Circ 2023, 32, 1000–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marko, M.; Singh, N.; Ospel, J.M.; Uchida, K.; Almekhlafi, M.A.; Demchuk, A.M.; Nogueira, R.G.; McTaggart, R.A.; Poppe, A.Y.; Rempel, J.L.; et al. Symptomatic Non-Stenotic Carotid Disease in Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source. Clin Neuroradiol 2024, 34, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsivgoulis, G.; Kargiotis, O.; Katsanos, A.H.; Patousi, A.; Pikilidou, M.; Birbilis, T.; Mantatzis, M.; Palaiodimou, L.; Triantafyllou, S.; Papanas, N.; et al. Clinical and Neuroimaging Characteristics in Embolic Stroke of Undetermined versus Cardioembolic Origin: A Population-Based Study. Journal of Neuroimaging 2019, 29, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arauz, A.; Morelos, E.; Colín, J.; Roldán, J.; Barboza, M.A. Comparison of Functional Outcome and Stroke Recurrence in Patients with Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source (ESUS) vs. Cardioembolic Stroke Patients. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0166091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Tang, X.; Liu, W.; Jia, K.; Zhao, X.; Yu, F. Clinical Features of Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source. Front Neurol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bembenek, J.P.; Karlinski, M.A.; Kurkowska-Jastrzebska, I.; Czlonkowska, A. Embolic Strokes of Undetermined Source in a Cohort of Polish Stroke Patients. Neurological Sciences 2018, 39, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scavasine, V.C.; Ribas, G. da C.; Costa, R.T.; Ceccato, G.H.W.; Zétola, V. de H.F.; Lange, M.C. Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source (ESUS) and Stroke in Atrial Fibrillation Patients: Not so Different after All? International Journal of Cardiovascular Sciences 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.H.; Heo, J.; Lee, H.; Jeong, J.; Kim, J.; Han, M.; Yoo, J.; Kim, J.; Baik, M.; Park, H.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Patients with Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source According to Subtype. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 9295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lattanzi, S.; Pulcini, A.; Corradetti, T.; Rinaldi, C.; Zedde, M.L.; Ciliberti, G.; Silvestrini, M. Prediction of Outcome in Embolic Strokes of Undetermined Source. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases 2020, 29, 104486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seet, R.C.S. Relationship Between Chronic Atrial Fibrillation and Worse Outcomes in Stroke Patients After Intravenous Thrombolysis. Arch Neurol 2011, 68, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntaios, G.; Perlepe, K.; Lambrou, D.; Sirimarco, G.; Strambo, D.; Eskandari, A.; Karagkiozi, E.; Vemmou, A.; Koroboki, E.; Manios, E.; et al. Prevalence and Overlap of Potential Embolic Sources in Patients With Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source. J Am Heart Assoc 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntaios, G.; Pearce, L.A.; Veltkamp, R.; Sharma, M.; Kasner, S.E.; Korompoki, E.; Milionis, H.; Mundl, H.; Berkowitz, S.D.; Connolly, S.J.; et al. Potential Embolic Sources and Outcomes in Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source in the NAVIGATE-ESUS Trial. Stroke 2020, 51, 1797–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamel, H.; Merkler, A.E.; Iadecola, C.; Gupta, A.; Navi, B.B. Tailoring the Approach to Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source. JAMA Neurol 2019, 76, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Monte, A.; Rivezzi, F.; Giacomin, E.; Peruzza, F.; Del Greco, M.; Maines, M.; Migliore, F.; Zorzi, A.; Viaro, F.; Pieroni, A.; et al. Multiparametric Identification of Subclinical Atrial Fibrillation after an Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source. Neurological Sciences 2023, 44, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.Y.Q.; Ho, J.S.Y.; Sia, C.-H.; Boi, Y.; Foo, A.S.M.; Dalakoti, M.; Chan, M.Y.; Ho, A.F.W.; Leow, A.S.; Chan, B.P.L.; et al. Left Atrial Volume Index Predicts New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation and Stroke Recurrence in Patients with Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source. Cerebrovascular Diseases 2020, 49, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathan, F.; Sivaraj, E.; Negishi, K.; Rafiudeen, R.; Pathan, S.; D’Elia, N.; Galligan, J.; Neilson, S.; Fonseca, R.; Marwick, T.H. Use of Atrial Strain to Predict Atrial Fibrillation After Cerebral Ischemia. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2018, 11, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Firth Coefficient |

OR | 95% CI | p-Value | Mean SHAP Value | 95% CI |

Feature Importance |

|

| Baseline Characteristics | |||||||

| Age Sex Pre-mRS score Hypertension Diabetes mellitus Current smoking Alcohol consumption |

-0.045 0.014 0.508 0.104 -0.331 -0.348 -0.021 |

0.96 1.01 1.66 1.11 0.72 0.71 0.98 |

0.94-0.97 0.67-1.54 1.42-1.95 0.64-1.92 0.47-1.09 0.40-1.23 0.64-1.49 |

<0.001* 0.948 <0.001* 0.712 0.120 0.223 0.923 |

0.039 -0.002 -0.017 -0.000 -0.003 -0.001 -0.000 |

-0.005-0.082 -0.003-0.000 -0.069-0.034 -0.002-0.001 -0.009-0.002 -0.003-(-0.000) -0.004-0.004 |

7.58% 4.89% 10.68% 2.96% 5.80% 3.34% 4.79% |

| Stroke Characteristics | |||||||

| Onset-door-time NIHSS score 72hNIHSS score Plasma-glucose INR |

0.000 -0.026 -0.131 -0.046 -0.009 |

1.00 0.97 0.88 0.96 0.99 |

1.00-1.00 0.94-1.02 0.85-0.90 0.88-1.03 0.98-1.00 |

0.407 0.226 <0.001* 0.251 0.110 |

-0.009 -0.008 0.078 -0.002 0.006 |

-0.022-0.005 -0.013-(-0.003) -0.082-0.237 -0.016-0.011 -0.009-0.022 |

5.91% 4.19% 38.97% 5.25% 5.63% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).