1. Introduction

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) encompasses a wide range of conditions, spanning from slow-progressing forms to highly aggressive cancers [

1]. The occurrence of NHL has been rising consistently in recent years. In 2020, approximately 545,000 new cases were reported globally, along with 260,000 related deaths [

2]. In NHL, achieving long-term survival relies not only on effectively treating malignancy but also on addressing the risks linked to treatment-related toxicity, with a focus on cardiotoxicity [

3]. A meta-analysis by Boyne and colleagues revealed that long-term survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma have a markedly elevated risk of cardiovascular-related mortality, being 7.3 and 5.35 times greater, respectively, than that of the general population [

4].

Cardiovascular adverse events associated with NHL therapy typically encompass cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction (CTRCD), myocarditis, vascular toxicities, hypertension, cardiac arrhythmias, QT interval prolongation, and pericardial vascular heart disease. The link between treatment approaches, such as anti-cancer drugs or radiotherapy, and these adverse effects is either well-documented or remains under study [

5]. For conditions such as cardiac injury, cardiomyopathy, and heart failure, the latest cardio-oncology guidelines and expert consensus advocate the use of the term cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction [

6]. The incidence of CTRCD in this population varies based on factors such as treatment regimens and individual patient characteristics. A study focusing on lymphoma patients receiving anthracycline-based chemotherapy reported a CTRCD incidence of 17.4% [

7]. Multimodality imaging, with a focus on echocardiography, plays a crucial role in assessing cardiac function both prior to and throughout antitumor treatment [

8].

Cardiorespiratory fitness, as measured by a cardiopulmonary exercise test reflects the integrated capacity of the cardiopulmonary system to deliver adequate oxygen and substrate to active skeletal muscles for adenosine triphosphate resynthesis. Cardiorespiratory fitness, therefore, provides a robust, objective evaluation of global physical functioning. While cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) is not a primary diagnostic tool for cancer therapy–related cardiac dysfunction it potential prognostic significance has been largely overlooked [

9]. Greater cardiorespiratory fitness, typically measured by peak oxygen consumption (VO₂ peak), has been linked to a reduced risk of cancer development [

10] and improved survival rates in large groups of cancer patients [

11]. A single-center study on adult-onset cancer patients, with a median follow-up of nearly five years, identified higher cardiorespiratory fitness as an independent predictor of overall mortality, cancer-specific mortality, and cardiovascular mortality [

12]. Taking this into consideration, we carried out this study to identify specific CPET parameters that could serve as early indicators of CTRCD, enhance understanding of the underlying mechanisms, and potentially guide personalized interventions to mitigate cardiovascular risks in cancer patients.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted prospectively thanks to a collaboration between the Public Medical-Sanitary Institution "Institute of Oncology" from which patients were randomly selected, and the Public Medical-Sanitary Institution "Institute of Cardiology" also from Chisinau, Republic of Moldova, where they were investigated. The group of patients included in the study consisted of those diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, aged over 18 years, who provided informed consent. The inclusion of patients in the study took place between 2022 and 2024, after the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the State University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Nicolae Testemitanu” (approval number 7/December 28, 2021). The research was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Patients were excluded from the study if they had a history of another oncological condition, prior treatments such as chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiotherapy, or pre-existing cardiac conditions, including known coronary or myocardial diseases (such as prior myocardial infarction, chronic ischemic syndromes, various cardiomyopathies, or post-inflammatory/infiltrative myocardial disorders). Additionally, those with moderate to severe valvular abnormalities (including moderate or greater valvular regurgitation and/or stenosis) or heart failure classified as class III-IV according to the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification were not included.

During the study implementation patients were asked through a questionnaire about cardiovascular disease risk factors (diabetes, dyslipidemia, smoking, hypertension) and their comorbidities (chronic kidney disease, proteinuria, chronic pulmonary obstructive disease, thyroid gland pathology). During the study periods data about characteristics of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and the treatment applied (groups of chemotherapeutic / immunotherapeutic agents, total dose of doxorubicine at 6-month follow-up) were collected. The patients were evaluated twice: first, before the initiation of specific antitumor treatment, and the second time after 6 months of treatment. They were assessed through echocardiography, cardiopulmonary exercise testing, and serological tests. From serological tests regarding the analysis presented here, we note that we assessed the quantitative levels of troponin I and NT-pro BNP at two stages: before the initiation of specific treatment and at 6 months after its start.

The echocardiographic examination was conducted by the same cardiologist using General Electric Vivid E95 ultrasound machine. The assessment of cardiac chamber size and function was performed in accordance with the guidelines provided by the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging for cardiac chamber quantification from 2015 [

13]. As per the diagnostic criteria outlined in the ESC 2022 Cardio-Oncology Guidelines, patients were categorized into two groups: those with CTRCD (Group I) and those without CTRCD (Group II), based on the observed changes in left ventricular ejection fraction, NT – pro BNP/troponin I levels.

Patients were introduced to the testing equipment of the cardiopulmonary test machine (Quark CPET Cosmed), including the cycle ergometer and ventilation assessment tools, and were instructed to perform at maximum effort while stopping the test if symptoms such as chest pain, palpitations, or dizziness occurred. Communication was conducted through non-verbal signals to avoid interfering with the accuracy of measured parameters. The testing setup included a cycle ergometer, a mask for collecting gas samples, and a system for analyzing the composition of exhaled gases. Simultaneous monitoring included a 12-lead ECG, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation.

The testing protocol followed a graded exercise design, where the intensity of physical effort increased progressively each minute during the exercise phase. The CPET protocol comprised four stages: rest, unloaded pedaling, incremental exercise, and recovery. The initial phase, lasting 3 minutes, was used to record baseline parameters such as ECG, heart rate, oxygen saturation, volume of oxygen (VO₂), and respiratory rate, while also allowing the patient to adapt to the equipment. This was followed by a 3-minute phase of unloaded pedaling. The incremental phase involved gradually increasing the workload over 8–12 minutes. The ramp rate, adjusted by the investigator based on the patient’s clinical status, ranged from 5 to 25 Watts. The formula for calculating the incremental ramp during CPET is as follows:

Ramp effort (W/min) = (VO₂ peak – VO₂ unloaded)/100, where:

VO₂ unloaded (ml/min) = 150 + (6 × body weight (kg))

VO₂ peak (ml/min) = (height (cm) – age (years)) × 20 (for men)

VO₂ peak (ml/min) = (height (cm) – age (years)) × 14 (for women)

The exercise stage continued until the patient either reached maximal effort or was unable to maintain a steady cadence. Patients were asked about any symptoms both during and after the test, and the Borg scale was used to evaluate their effort at the end. The recovery phase, lasting approximately 5 minutes, involved unloaded pedaling. Monitoring continued during this phase until the ECG normalized, blood pressure stabilized, and heart rate decreased by 10 beats per minute compared to baseline. The CPET parameters evaluated included: hemodynamic metrics (initial heart rate, peak heart rate, initial and final systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and initial/final oxygen saturation), VO₂ peak, VO₂ at the anaerobic threshold, anaerobic threshold as a percentage of VO₂, volume of oxygen per heart rate (VO₂ pulse), volume of oxygen per work rate (VO₂/WR), maximum respiratory exchange ratio, minute ventilation, ventilation efficiency (minute ventilation/VCO₂), respiratory reserve, end-tidal CO₂ pressure, and the oxygen consumption efficiency curve. Furthermore, we examined the presence of a VO₂ peak < 14 ml/kg/min, indicative of reduced aerobic capacity, which is linked to a higher risk of cardiovascular events and mortality.

Statistical Analysis

The analysis of the primary data was conducted using RStudio (version 2024.09.1+394, available at

https://www.rstudio.com/) and Python (version 3.12.3, accessible via

https://www.python.org/). These platforms facilitated full reproducibility of the statistical procedures employed. Descriptive statistics for numerical variables included calculations for the minimum, maximum, mean, and standard deviation, as well as the median, interquartile range (IQR), and the 25th and 75th percentiles. To compare numerical variables across groups, the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test was utilized. Box plots were used to visualize group differences for numerical variables, while correlation analysis (Spearman test with 95% confidence intervals) was represented via heatmaps. For categorical variables, absolute and relative frequencies were determined, with relative frequencies accompanied by their respective 95% confidence intervals. Hypothesis testing for categorical data employed Pearson's Chi-squared test, specifically the Monte Carlo variant with 100,000 samples. Across all statistical analyses, the significance threshold (α) was maintained at 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical and Demographic Characteristics

The study enrolled 127 patients diagnosed with NHL, comprising 72 men (56.7%) and 55 women (43.3%), with a median age of 62 years (IQR=14.0), ranging from 34 to 83 years old. Group I included 18 patients (14.2%) who developed CTRCD at 6 months follow-up, remaining patients were included in Group II (no CTRCD). Patients’ characteristics and comorbidities are presented in

Table 1. It should be noted that patients with a body mass index (BMI) > 30 kg/m² were statistically significantly more prevalent in Group I, with 8 subjects (44.4%, 95% CI: 21, 67), compared to 23 subjects in Group II (21.1%, 95% CI: 13, 29), as indicated by the Monte Carlo test result of 4.6, p=0.043. Dyslipidemia was also more prevalent among patients with CTRCD, affecting 17 patients (94.4%, 95% CI: 84, 105) compared to 67 patients (71.5%, 95% CI: 52, 71) in Group II, with a Monte Carlo test result of 7.5, p=0.006. Additionally, the severity of arterial hypertension was significantly higher among patients who subsequently developed CTRCD, indicating a greater degree of hypertension in this group, with a Monte Carlo test result of 24, p<0.001.

Regarding disease stage distribution, the majority of patients were classified as stage IV, accounting for 89 individuals (70.1%, CI: 62, 78). This was followed by 18 patients (14.2%, CI: 8.1, 20) in stage III, 16 patients (12.6%, CI: 6.8, 18) in stage II, and only 4 patients (3.1%, CI: 0.11, 6.2) in stage I. In terms of NHL treatment, most patients underwent a combination of chemotherapy and immunotherapy, totaling 114 cases (89.8%, CI: 84, 95). Chemotherapy alone was administered to 7 patients (5.5%, CI: 1.5, 9.5), while 5 patients (3.9%, CI: 0.55, 7.33) received immunotherapy as a standalone treatment. Doxorubicin was included in the treatment protocols for 80 patients (63.0%, CI: 55, 71), while 47 patients (37.0%, CI: 29, 45) did not receive anthracyclines. The median cumulative dose of doxorubicin at the end of study was 250 mg/m² (IQR = 410.0). The specifics of the oncological disease and treatment aspects are presented in

Table 2.

3.2. Correlations Between Baseline Cardiopulmonary Parameters and Left Ventricular Function at 6-Month Follow-Up

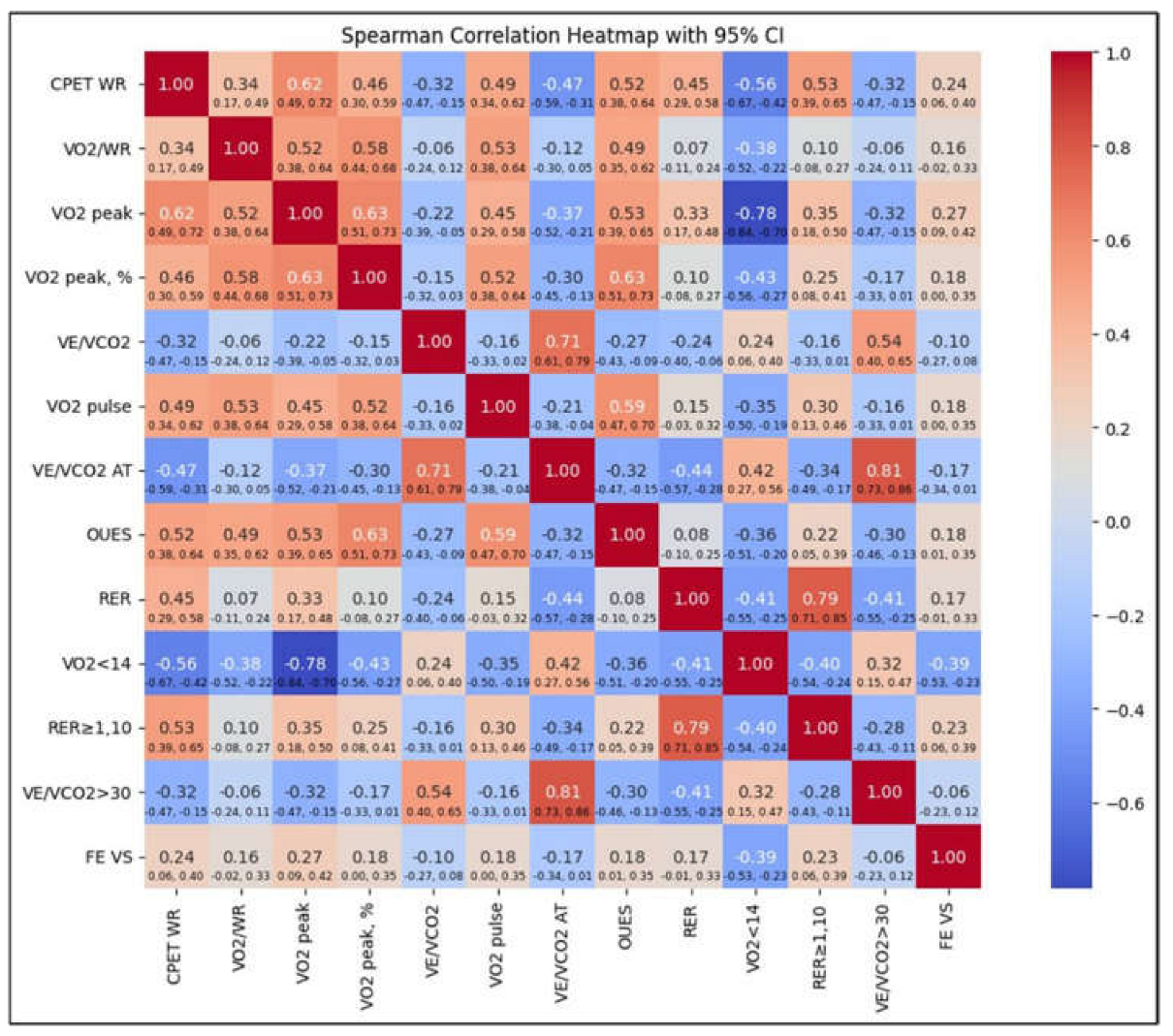

During the CPET, not all patients included in the study were able to complete the test. In Group I, 1 patient was unable to perform the test, while in Group II, 3 patients were unable to complete it. The inability to perform CPET was attributed to the advanced stage of the LNH. Consequently, the CPET data analyzed included results from 17 patients in Group I and 106 patients in Group II. We conducted an analysis of the relationship between cardiopulmonary parameters and changes in left ventricular function over time. This is depicted in

Figure 1, which features a heatmap illustrating Spearman correlations between various parameters from the initial CPET performed at the start of the study and the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) measured after 6 months of treatment. Among the analyzed parameters, VO₂ peak showed the strongest positive correlation with LVEF at 6 months (0.27). This suggests that better functional performance during the baseline CPET may predict improved left ventricular function at the third follow-up visit. Conversely, a VO₂ peak < 14 ml/kg/min (indicating reduced peak oxygen consumption below the threshold of 14 ml/kg/min) was negatively correlated with LVEF at 6 months (-0.39), highlighting that patients with very low baseline VO₂ peak are more likely to experience reduced ejection fractions after 6 months. The work rate (WR) exhibited a moderate positive correlation (0.24), indicating that higher exercise capacity at baseline is associated with improved LVEF after 6 months. Similarly, an respiratory exchange ratio (RER) ≥ 1 (respiratory exchange ratio of 1 or higher) demonstrated a moderate positive correlation (0.23) with LVEF at the final assessment, suggesting that achieving maximal effort, as indicated by RER ≥ 1, is linked to better LVEF outcomes. A weaker positive correlation (0.18) was identified with the oxygen uptake efficiency slope (OUES), indicating that patients with higher baseline OUES values tend to show better LVEF at 6 months.

3.3. Analysis of Cardiopulmonary Fitness and Its Impact on Patients with and Without CTRCD

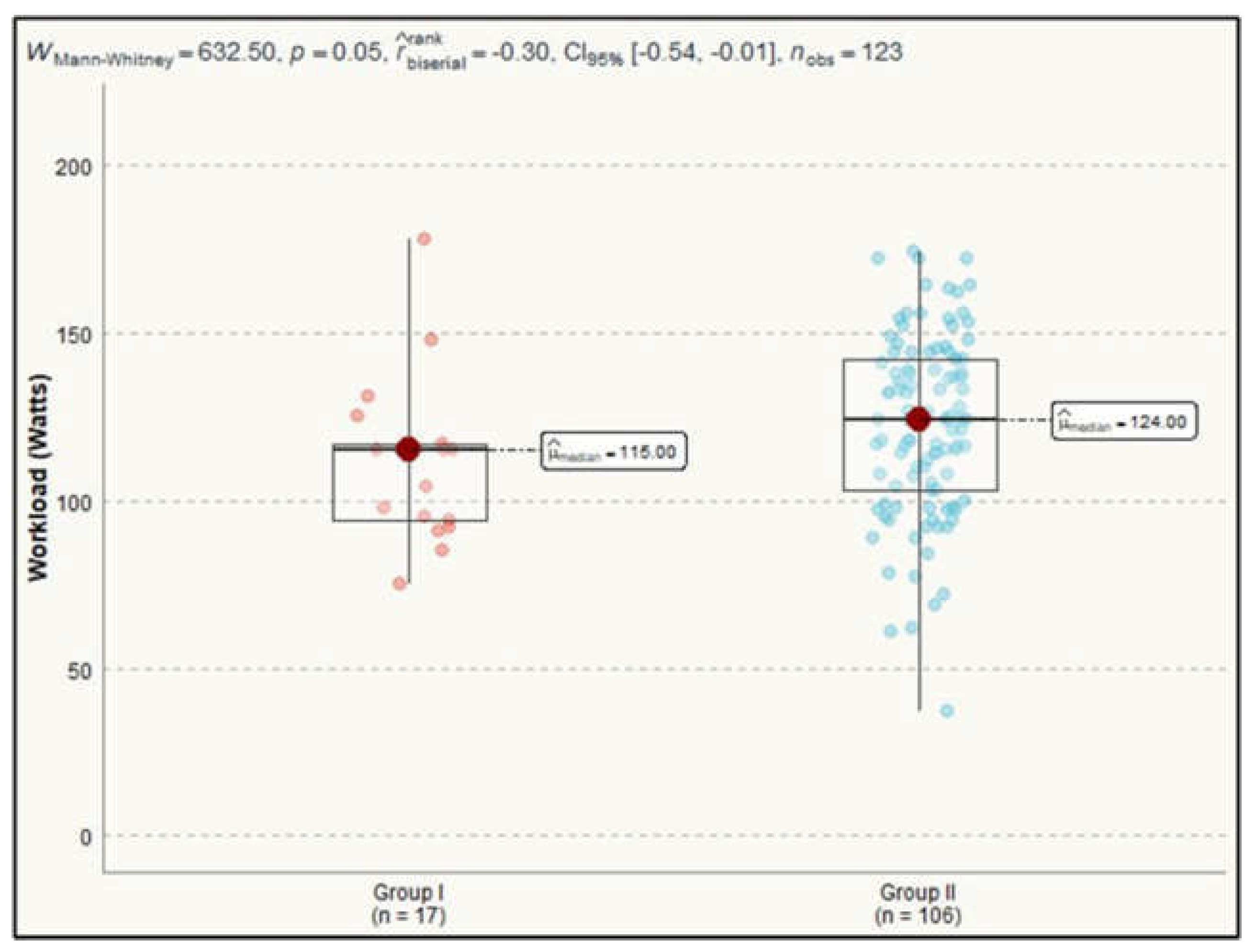

The maximum heart rate achieved in patients from Group I had a median of 123 bpm (IQR=11.0), while in Group II, the median was 124.0 bpm (IQR=22.8). The external mechanical workload or power output generated during exercise was a statistically significant difference between the groups. Group I had a median work rate of 115.0 Watts (IQR=23.0), while Group II achieved a median of 124.0 Watts (IQR=38.8). This difference was confirmed by a Mann-Whitney test result of 633, p=0.049 (

Figure 2).

The ability to achieve a maximal cardiopulmonary test analyzed by assessing the respiratory exchange ratio, showed no difference between the two groups (Mann-Whitney test=735, p=0.2). Although no statistically significant differences were observed between the groups in terms of median RER values (Mann-Whitney test=736, p=0.2), with a median of 1.1 (IQR=0.2) in Group I and 1.1 (IQR=0.1) in Group II, a statistically significant difference was noted in the proportion of patients achieving a RER ≥ 1.10. A RER ≥ 1.10 was significantly more frequent among patients who did not develop CTRCD compared to those who did. In the group without CTRCD, an RER ≥ 1.10 was observed in 79 participants (74.5%, 95% CI: 66, 83) compared to 8 patients (47.1%, 95% CI: 23, 71) in the group that developed CTRCD. This difference was statistically significant (Monte Carlo test=5.3, p=0.026). Among cardiovascular parameters, for final systolic blood pressure, no significant differences were observed between the groups. In Group I, the median systolic blood pressure was 145.0 mmHg (IQR=16.0), compared to 150.5 mmHg (IQR=14.0) in Group II (Mann-Whitney test=787, p=0.4). However, the final diastolic blood pressure showed statistically significant differences, with a Mann-Whitney test value of 563, p=0.013. In Group I, the median diastolic blood pressure was 75.0 mmHg (IQR=15.0) compared to 86.5 mmHg (IQR=10.0) in Group II. An additional cardiovascular measure, such as oxygen pulse (VO₂ pulse), was not different between the patients before the specific antitumoral treatment have started. Median value for Group I was 10.2 (IQR=3.8) and 12.1 (IQR=3.8) for Group II, Mann-Whitney test=776, p=0.4.

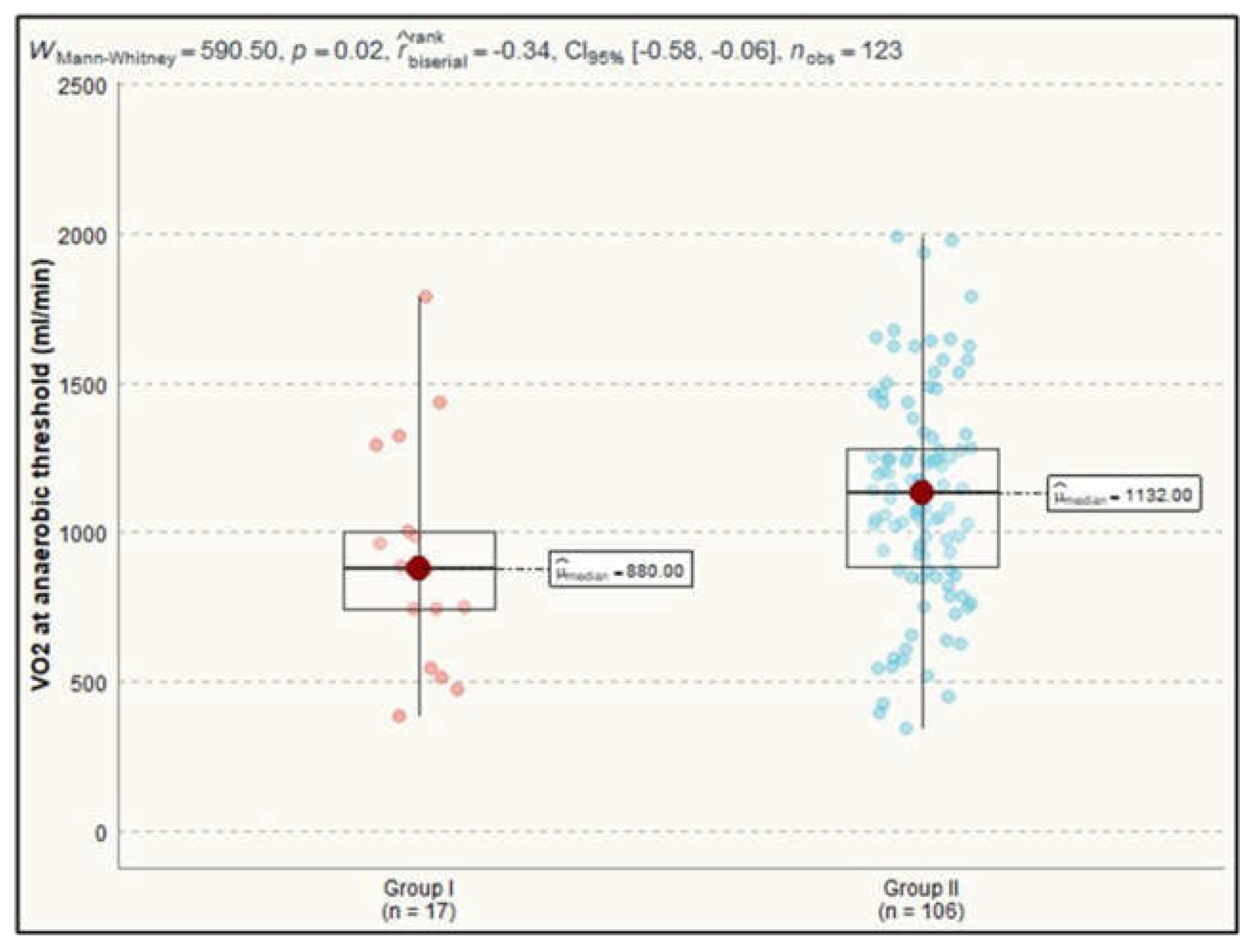

Analyzing the differences of parameters assessing metabolic gas exchange we observed a statistically significant impact on VO₂ at anaerobic threshold and O₂ consumption efficiency curve between the investigated groups. For VO₂ at anaerobic threshold, the median value in Group I was 880.0 ml/min (IQR=262.0), while in Group II it was 1132.0 ml/min (IQR=394.5), with a Mann-Whitney test result of 591, p=0.023 (

Figure 3).

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

Regarding the O₂ consumption efficiency curve, the median value in the group that developed CTRCD was 1811.0 (IQR=457.0), whereas in the group that did not develop CTRCD at 6 months of treatment, it was 2145.5 (IQR=659.8), with a Mann-Whitney test result of 612, p=0.034.

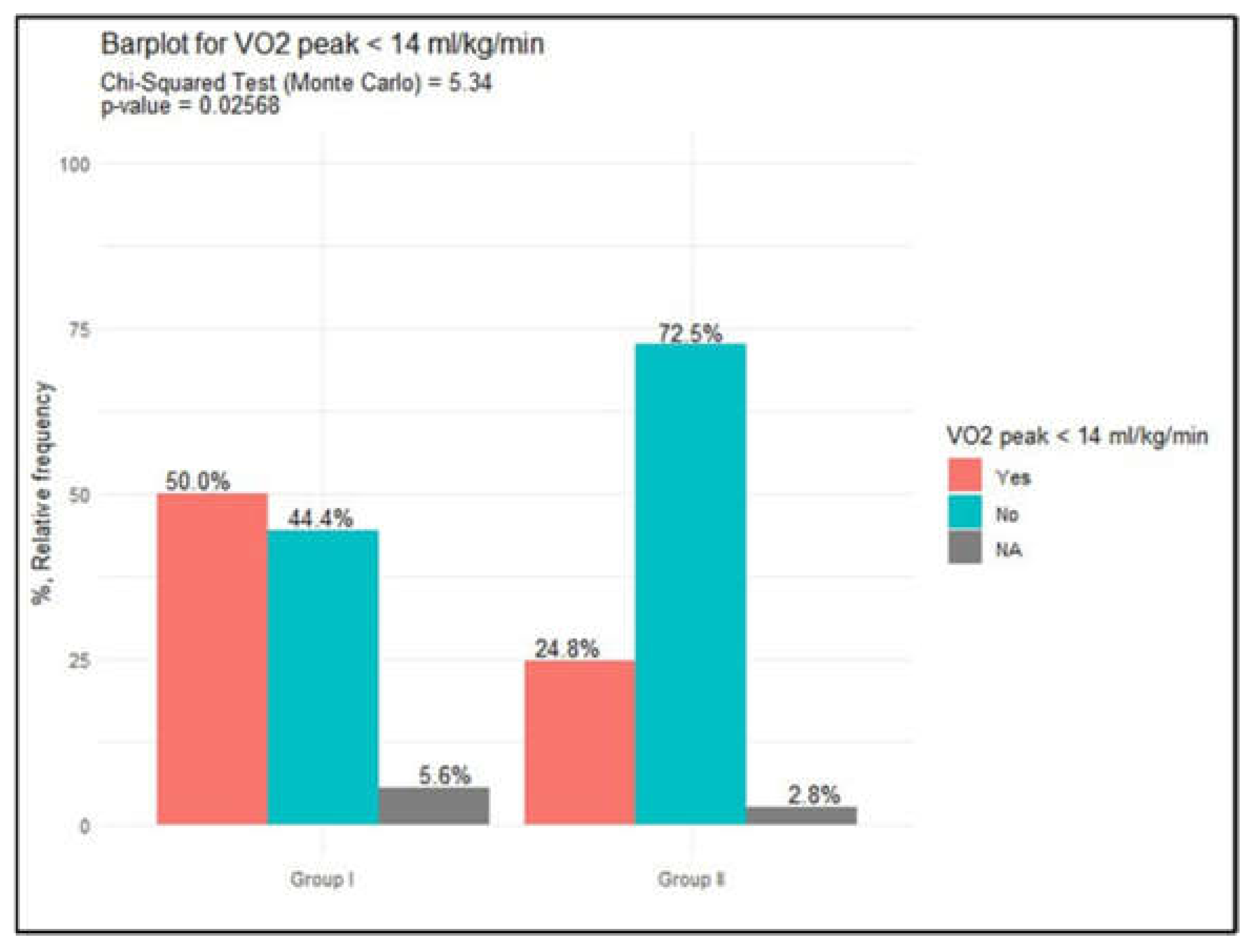

In the analysis of metabolic parameters, no statistically significant differences were observed between the groups in terms of oxygen consumption and peak oxygen uptake. The median VO₂ peak was 13.6 ml/kg/min (IQR=3.7) in Group I and 15.5 ml/kg/min (IQR=4.4) in Group II, with a Mann-Whitney test result of 697, p=0.14. However, a VO₂ peak < 14 ml/kg/min was more frequently noted in Group I compared to Group II, with 9 patients (52.9%, 95% CI: 29, 77) in Group I and 27 patients (25.5%, 95% CI: 17, 34) in Group II. This difference reached statistical significance, as indicated by the Monte Carlo test (5.3, p=0.027), data presented in

Figure 4.

Another parameter of interest investigated was VO₂ peak (% predicted), which is considered a key tool for diagnosing exercise intolerance and identifying subclinical heart failure [

14]. This indicator did not differ significantly between the patients. In Group I, the median was 61.0 % (IQR=13.0), while in Group II, it was 64.0 % (IQR=19.0), with a Mann-Whitney test result of 768, p=0.3. Other parameters of gas exchange also did not differ significantly, as presented in

Table 3.

The parameters evaluating ventilatory performance, assessed through cardiopulmonary testing, showed no statistically significant differences between patients who developed CTRCD and those who did not. The ventilatory efficiency slope (VE/VCO₂ slope), representing the relationship between minute ventilation (VE) and carbon dioxide production (VCO₂) during exercise, showed a lack of statistical significance between the analyzed groups, in Group I median value was 32.7 (IQR=5.9) and in Group II median value was 31.2 (IQR=5.4), Mann-Whitney test=994, p=0.5. The end-tidal partial pressure of carbon dioxide (Pet CO₂), key indicator of alveolar gas exchange and reflects how effectively the lungs are ventilating CO₂ out of the body also did not show differences between groups analyzed, Mann-Whitney test=1068, p=0.2.

4. Discussion

The findings of our study provide early insights into the relationship between cardiopulmonary parameters and the development of cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction in patients diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. There is published data about cardiorespiratory fitness, assessed via cardiopulmonary exercise testing through measures like peak oxygen consumption [

15] or metabolic equivalents [

16], that indicate highly reliable predictors of cardiovascular health and longevity [

17]. It also enhances risk stratification, aiding in better health outcomes and management decisions [

18]. The relation between baseline VO₂ peak and LVEF at 6 months, reinforces the role of VO₂ peak as an indicator of cardiopulmonary fitness and its prognostic significance. Other studies also have showed the role of VO₂ peak as an important marker of cardiovascular health in oncology patients. Study data showed that a higher VO₂ peak predicts better cardiac outcomes in cancer survivors [

19], aligning with our study’s findings that patients with VO₂ peak < 14 ml/kg/min were more likely to experience reduced LVEF at 6 months follow-up.

The current research identified a significant difference in the proportion of patients achieving a respiratory exchange ratio ≥ 1.10, with fewer patients with CTRCD reaching this threshold (p=0.026). This validates the fact that maximal effort during CPET is an indicator of a better cardiac reserve, as mentioned by Jones et al. [

20]. However, the absence of significant differences in median RER values between samples emphasizes additional research for better understanding of the relationship between RER and CTRCD onset. The lower median work rate suggests it may be quantified as a predictor of vulnerability to cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction occurrence. This finding highlights the value of baseline measured physical performance in identifying individuals at higher risk of CTRCD, ensuring earlier monitoring and preventive strategies. Other studies showed that reduced cardiorespiratory fitness is a major determinant of cardiovascular morbidity and cancer survival, suggesting that maintaining or improving cardiorespiratory fitness could be beneficial in mitigating treatment-related cardiac dysfunction [

21]. The significant differences in work rate and VO₂ at the anaerobic threshold between groups suggest a reduced exercise capacity in patients who developed CTRCD. These data correspond with reports from Lakoski et al., who showed that exercise intolerance correlates with subclinical cardiac dysfunction in cancer patients [

22]. Furthermore, the lack of significant differences in metabolic parameters such as the ventilatory efficiency slope, aligns with other resources, indicating that gas exchange efficiency may be less sensitive to CTRCD. Additional studies of Arena et al., similarly, noted that VE/VCO₂ may have limited predictive value in early-stage cardiac dysfunction [

23]. However, some published data, demonstrates that a VE/VCO₂ slope greater than 35 was associated with increased mortality after lung cancer resection, underlining its prognostic value in advanced disease stages [

24].

Limitations

While the study provides important insights, certain limitations must be acknowledged. The single-center design may limit general applicability, and the relatively small sample size could impact the robustness of statistical associations. Additionally, biomarkers of cardiotoxicity, such as troponin and natriuretic peptides, along with CPET parameters could enhance the predictive accuracy of CTRCD models.

5. Conclusions

The findings point out the importance of baseline cardiopulmonary exercise in identifying patients at risk for cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction. Parameters such as VO₂ peak, workload, VO₂ at anaerobic threshold and RER ≥ 1.10 are critical indicators of future cardiac performance and should be closely monitored for early high-risk individuals’ identification.

Patients with low VO₂ peak or suboptimal exercise capacity might become candidates for targeted interventions, such as tailored exercise programs or cardioprotective strategies, to preserve cardiac function during and after cancer treatment. The results reinforce the role of CPET as a tool in cardio-oncology for improving long-term cardiac outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B.; Data curation, D.B. and M.R.; Formal analysis, D.B.; Investigation, D.B. and M.R.; Methodology, D.B. and O.A.; Resources, V.R.; Supervision, V.R.; Visualization, D.B. and V.R.; Writing – original draft, D.B.; Writing – review & editing, D.B. and O.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the State University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Nicolae Testemitanu” (approval number 7/December 28, 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BMI |

body mass index |

| CI |

confidence interval |

| CO2 |

carbon dioxide |

| CPET |

cardiopulmonary exercise testing |

| ECG |

electrocardiogram |

| IQR |

interquartile range |

| NHL |

non-Hodgkin lymphoma |

| OUES |

oxygen uptake efficiency slope |

| RER |

respiratory exchange ratio |

| LVEF |

left ventricular ejection fraction |

| VCO2 |

volume of carbon dioxide |

| VE/VCO2 |

ventilatory equivalent for carbon dioxide |

| VO2 |

volume of oxygen |

| VO2 peak |

peak oxygen uptake |

| VO2 pulse |

volume of oxygen per heart rate |

| VO2/WR |

volume of oxygen per work rate |

References

- Armitage, J.; Gascoyne, R.; Lunning, M.; Cavalli, F. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Lancet, 1009. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Fang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Ding, M.; Ge, X. , et al. The epidemiological patterns of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: global estimates of disease burden, risk factors, and temporal trends. Front Oncol.

- Maraldo, M.; Levis, M.; Andreis, A.; Armenian, S.; Bates, J.; Brady, J.; Ghigo, A.; Lyon, A.; Manisty, C.; Ricardi, U.; Aznar, M.; Filippi, A. An integrated approach to cardioprotection in lymphomas. Lancet Haematol, e: 9(6).

- Boyne, D.; Mickle, A.; Brenner, D.; Friedenreich, C.; Cheung, W.; Tang, K.; Wilson, T.; Lorenzetti, D.; James, M.; Ronksley, P.; Rabi, D. Long-term risk of cardiovascular mortality in lymphoma survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Med, 4: 7(9), 4801. [Google Scholar]

- Rihackova, E.; Rihacek, M.; Vyskocilova, M.; Valik, D.; Elbl, L. Revisiting treatment-related cardiotoxicity in patients with malignant lymphoma—a review and prospects for the future. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyon, A.; López-Fernánde, T.; Couch, L.; Asteggiano, R.; Aznar, M.; Bergler-Klei, J.; et al. 2022 ESC Guidelines on cardio-oncology developed in collaboration with the European Hematology Association (EHA), the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ESTRO) and the International Cardio-Oncology Society (IC-OS). Eur Heart J, 4: 43(41), 4229. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Garcia, A. ; Macia, E; Gomez-Talavera, S.; Castillo, E.; Morillo, D.; Tuñon, J.; et al. Predictive Factors of Therapy-Related Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Lymphoma Receiving Anthracyclines. Med Sci (Basel).

- Perez, I.; Taveras, A.; Hernandez, G.; Sancassani, R. Cancer Therapy-Related Cardiac Dysfunction: An Overview for the Clinician. Clinical Medicine Insights: Cardiology, 1179. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, L.; Eves, N.; Haykowsky, M.; Freedland, S.; Mackey, J. Exercise intolerance in cancer and the role of exercise therapy to reverse dysfunction. The Lancet Oncology.

- Squires, R.; Shultz, A.; Herrmann, J. Exercise Training and Cardiovascular Health in Cancer Patients. Curr Oncol Rep, 2: 20(3).

- Lahart, I.; Metsios, G.; Nevill, A.; Carmichael, A. Physical activity, risk of death and recurrence in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Acta Oncol.

- Groarke, J.; Payne, D.; Claggett, B.; Mehra, M.; Gong, J.; Caron, J.; et al. Association of post-diagnosis cardiorespiratory fitness with cause-specific mortality in cancer. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes.

- Lang, R.; Badano, L.; Victor, M.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: An update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography.

- Piepoli, M.; Spoletini, I.; Rosano, G. Monitoring functional capacity in heart failure. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2019, 21(Suppl M):M9-M12.

- Kaminsky, L.; Imboden, M.; Arena, R.; Myers, J. Reference Standards for Cardiorespiratory Fitness Measured with Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing Using Cycle Ergometry: Data From the Fitness Registry and the Importance of Exercise National Database (FRIEND) Registry. Mayo Clin Proc, 2: 92(2).

- Jetté, M.; Sidney, K.; Blümchen, G. Metabolic equivalents (METS) in exercise testing, exercise prescription, and evaluation of functional capacity. Clin Cardiol.

- Ross, R.; Blair, S.; Arena, R.; Church, T.; Després, J.; Franklin, B.; et al. Importance of Assessing Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Clinical Practice: A Case for Fitness as a Clinical Vital Sign: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation.

- Fardman, A.; Banschick, G.; Rabia, R.; Percik, R.; Fourey, D. ; Segev, S; et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and survival following cancer diagnosis. Eur J Prev Cardiol.

- Haykowsky, M.; Brubaker, P.; Stewart, K.; Morgan, T.; Eggebeen, J.; Kitzman, D. Effect of endurance training on the determinants of peak exercise oxygen consumption in elderly patients with stable compensated heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol.

- Jones, L.; Eves, N.; Mackey, J.; Peddle, C.; Haykowsky, M.; Joy, A. Courneya KS, Tankel K, Spratlin J, Reiman T. Safety and feasibility of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in patients with advanced cancer. Lung Cancer, 2: 55(2).

- Wernhart, S.; Rassaf, T. Exercise, cancer, and the cardiovascular system: clinical effects and mechanistic insights. Basic Res Cardiol. [PubMed]

- Lakoski, S.; Barlow, C.; Gao, A.; DeFina, L.; Radford, N.; Farrell, S.; et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and risk of cancer incidence and cause-specific mortality following a cancer diagnosis in men: The Cooper Center longitudinal study. Journal of Clinical Oncology.

- Arena, R.; Myers, J.; Abella, J.; Peberdy, M.; Bensimhon, D.; Chase, P.; Guazzi, M. Development of a ventilatory classification system in patients with heart failure. Circulation, 2410. [Google Scholar]

- Brunelli, A. Ventilatory efficiency slope: an additional prognosticator after lung cancer surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg, 7: 50(4).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).