Submitted:

10 January 2025

Posted:

13 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Sample Selection & Outcomes

2.2. Covariates

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Sensitivity Analysis

3. Results

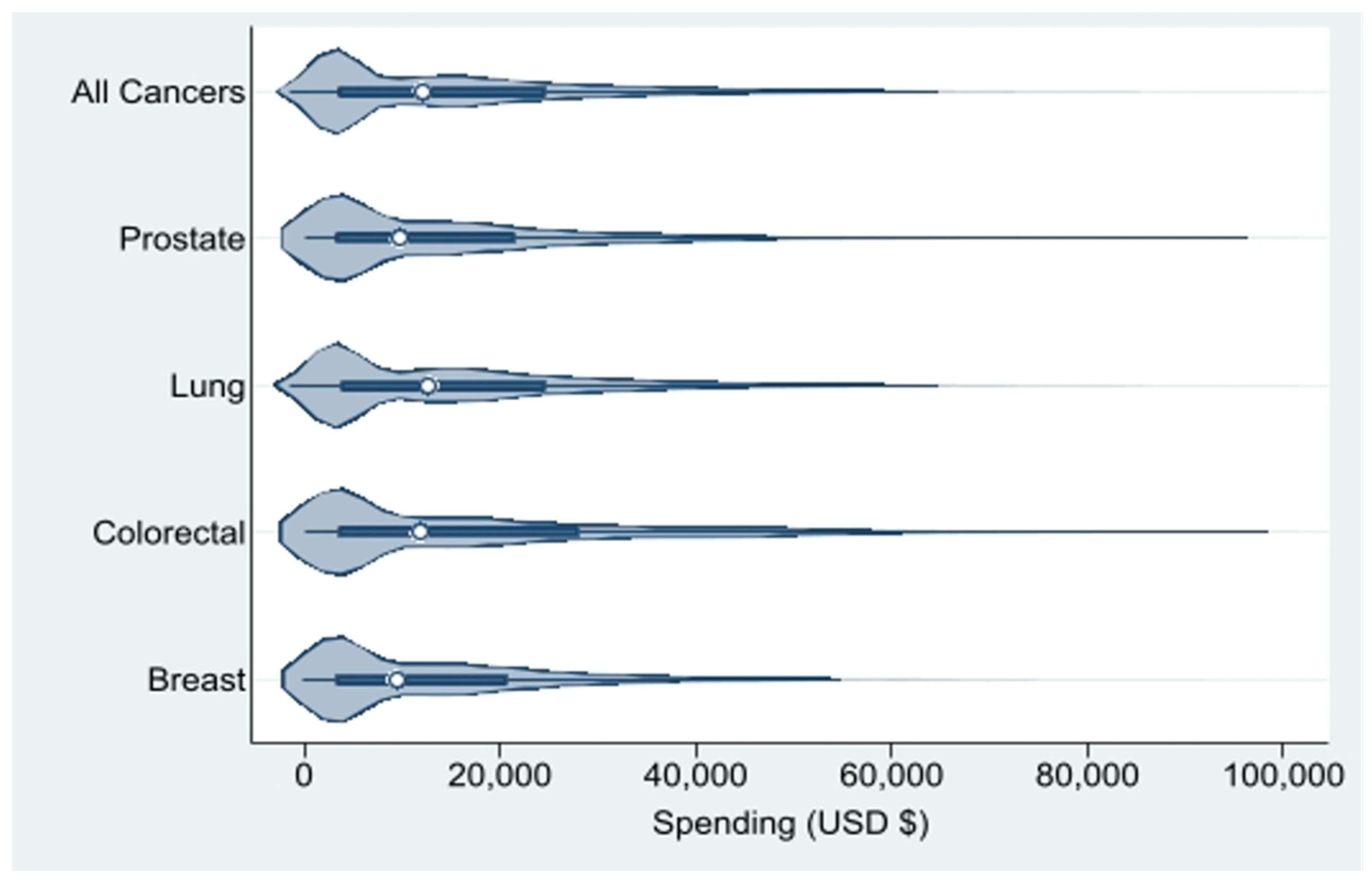

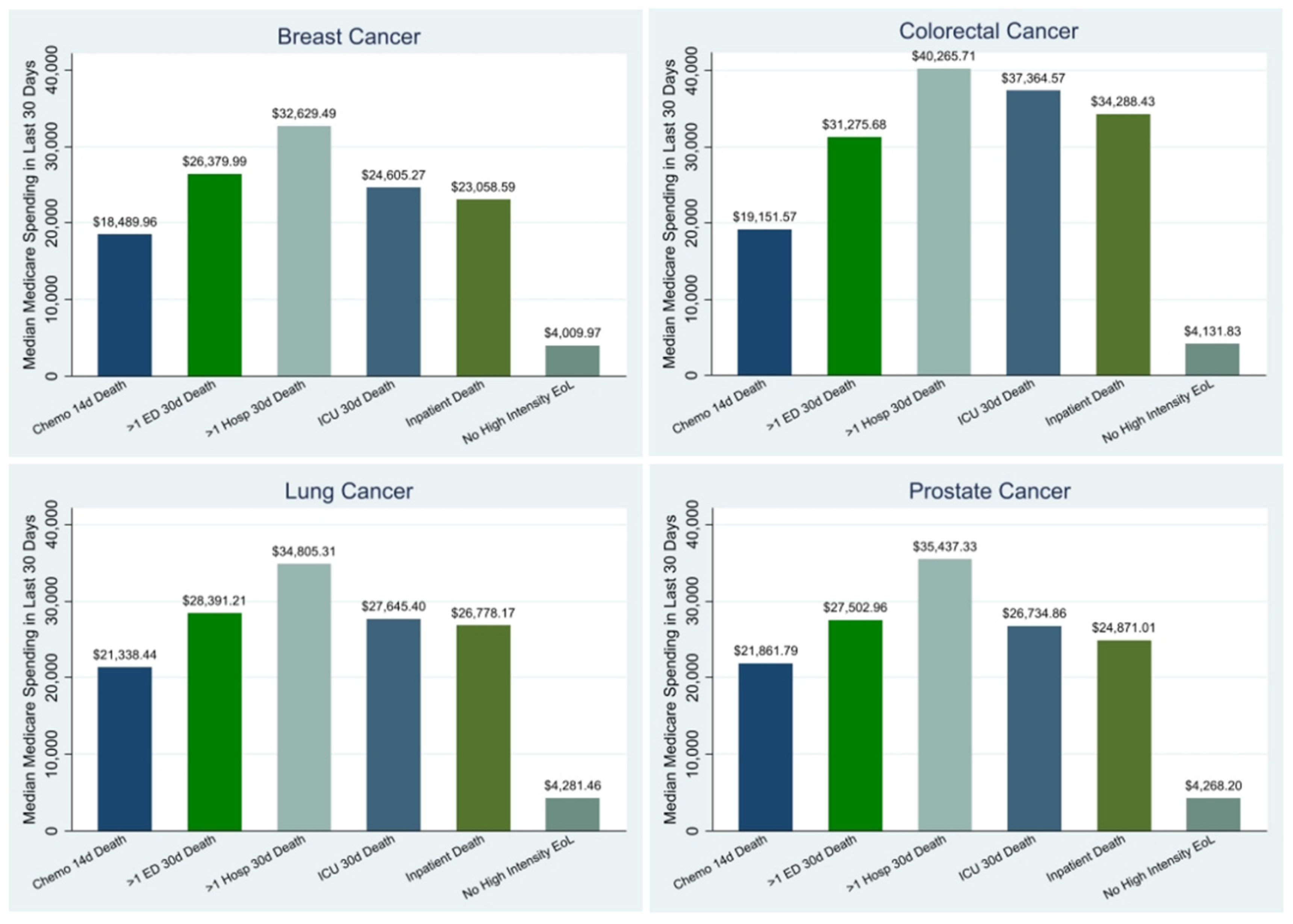

3.1. Descriptive Results

3.2. Predictor Results

3.3. Regression Results for Additional Analyses

4. Discussion

4.2. Demographic Predictors

4.3. Geographic Predictors

4.4. Sensitivity Analysis

4.5. Recommendations for Policy & Practice

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Model Fit Based on Box-Cox Transformation

Claims-based Indicators of Aggressive Cancer Care at the EoL

Chemotherapy Endpoint

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 1: MD, Bradley EH (2017) Epidemiology And Patterns Of Care At The End Of Life: Rising Complexity, Shifts In Care Patterns And Sites Of Death Health Aff (Millwood) 36, 2017.

- 2: JM, Gozalo P, Trivedi AN, Bunker J, Lima J, Ogarek J, Mor V (2018) Site of Death, Place of Care, and Health Care Transitions Among US Medicare Beneficiaries, 2000-2015 JAMA 320, 2018.

- 8: JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, Welch LC, Wetle T, Shield R, Mor V (2004) Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care JAMA 291, 2004.

- 2: AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, Chrischilles EA, Kahn KL, Ritchie CS, Weeks JC, Earle CC, Landrum MB (2016) Family Perspectives on Aggressive Cancer Care Near the End of Life JAMA 315, 2016.

- 4: AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, Matulonis UA, Block SD, Prigerson HG (2010) Place of death: correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers' mental health J Clin Oncol 28, 2010.

- 8: MM, Balboni TA, Maciejewski PK, Bao Y, Prigerson HG (2015) Quality of Life and Cost of Care at the End of Life: The Role of Advance Directives J Pain Symptom Manage 49, 2015.

- 4: B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, Nilsson ME, Maciejewski ML, Earle CC, Block SD, Maciejewski PK, Prigerson HG (2009) Health care costs in the last week of life: associations with end-of-life conversations Arch Intern Med 169, 2009.

- 1: JD, Riley GF (1993) Trends in Medicare payments in the last year of life N Engl J Med 328, 1993.

- 3: N (1984) Utilization and costs of Medicare services by beneficiaries in their last year of life Med Care 22, 1984.

- 7: SS, Kale M, Keyhani S, Roman BR, Yang A, Derosa AP, Korenstein D (2017) Overuse of Health Care Services in the Management of Cancer: A Systematic Review Med Care 55, 2017.

- 6: C, Kerr K, McGuire J, Rabow MW (2016) The Costs of Waiting: Implications of the Timing of Palliative Care Consultation among a Cohort of Decedents at a Comprehensive Cancer Center J Palliat Med 19, 2016.

- 3: S, Hsu SH, Huang S, Soulos PR, Gross CP (2017) Longer Periods Of Hospice Service Associated With Lower End-Of-Life Spending In Regions With High Expenditures Health Aff (Millwood) 36, 2017.

- 1: AZ, Hyer JM, Palmer E, Lustberg MB, Pawlik TM (2021) Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Hospice Utilization Among Medicare Beneficiaries Dying from Pancreatic Cancer J Gastrointest Surg 25, 2021.

- 8: YE, Williams CP, Jackson BE, Dionne-Odom JN, Taylor R, Ejem D, Kvale E, Pisu M, Bakitas M, Rocque GB (2019) Disparities in Hospice Utilization for Older Cancer Patients Living in the Deep South J Pain Symptom Manage 58, 2019.

- 1: AH, Bull JH, Swetz KM, Wolf SP, Shanafelt TD, Myers ER (2017) Future of the Palliative Care Workforce: Preview to an Impending Crisis Am J Med 130, 2017.

- 9: AH, Wolf SP, Troy J, Leff V, Dahlin C, Rotella JD, Handzo G, Rodgers PE, Myers ER (2019) Policy Changes Key To Promoting Sustainability And Growth Of The Specialty Palliative Care Workforce Health Aff (Millwood) 38, 2019.

- 2: ME, Black L, Benedict A, Roehrborn CG, Albertsen P (2010) Long-term medical-care costs related to prostate cancer: estimates from linked SEER-Medicare data Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 13, 2010.

- 1: B, Lin YS, Castel LD (2017) Cost drivers for breast, lung, and colorectal cancer care in a commercially insured population over a 6-month episode: an economic analysis from a health plan perspective J Med Econ 20, 2017.

- 6: KR, Lamont EB, Mariotto A, Warren JL, Topor M, Meekins A, Brown ML (2008) Cost of care for elderly cancer patients in the United States J Natl Cancer Inst 100, 2008.

- 1: NL, Huskamp HA, Kouri E, Schrag D, Hornbrook MC, Haggstrom DA, Landrum MB (2018) Factors Contributing To Geographic Variation In End-Of-Life Expenditures For Cancer Patients Health Aff (Millwood) 37, 2018.

- 2: LR, Bird CE, Schuster CR, Lynn J (2007) Age and gender differences in Medicare expenditures at the end of life for colorectal cancer decedents J Womens Health (Larchmt) 16, 2007.

- 1: LR, Bird CE, Schuster CR, Lynn J (2008) Age and gender differences in medicare expenditures and service utilization at the end of life for lung cancer decedents Womens Health Issues 18, 2008.

- 3: H, Qiu F, Boilesen E, Nayar P, Lander L, Watkins K, Watanabe-Galloway S (2016) Rural-Urban Differences in Costs of End-of-Life Care for Elderly Cancer Patients in the United States J Rural Health 32, 2016.

- 1: S, Rajan SS, Revere FL, Sharma G (2019) Factors Affecting Racial Disparities in End-of-Life Care Costs Among Lung Cancer Patients: A SEER-Medicare-based Study Am J Clin Oncol 42, 2019.

- Cancer Stat Facts: Common Cancer Sites. In: Editor (ed)^(eds) Book Cancer Stat Facts: Common Cancer Sites, City.

- 8: AS, Morrison RS, Wenger NS, Ettner SL, Sarkisian CA (2010) Determinants of treatment intensity for patients with serious illness: a new conceptual framework J Palliat Med 13, 2010.

- 5: AJ, Gardner LD, Zuckerman IH, Hendrick F, Ke X, Edelman MJ (2014) Validation of disability status, a claims-based measure of functional status for cancer treatment and outcomes studies Med Care 52, 2014.

- 5: CN, Legler JM, Warren JL, Baldwin LM, Schrag D (2007) A refined comorbidity measurement algorithm for claims-based studies of breast, prostate, colorectal, and lung cancer patients Ann Epidemiol 17, 2007.

- 2: GEP, Cox DR (1964) An Analysis of Transformations J Roy Stat Soc B 26, 1964.

- 3: CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, Ayanian JZ, Block SD, Weeks JC (2004) Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life J Clin Oncol 22, 2004.

- 1: CC, Park ER, Lai B, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ, Block S (2003) Identifying potential indicators of the quality of end-of-life cancer care from administrative data J Clin Oncol 21, 2003.

- e: H, Barbera LC, McGrail K, Burge F, Guthrie DM, Lawson B, Chan KKW, Peacock SJ, Sutradhar R (2022) Effect of Early Palliative Care on End-of-Life Health Care Costs: A Population-Based, Propensity Score-Matched Cohort Study JCO Oncol Pract 18, 2022.

- S: MB, Lynn J, Teno JM, Covinsky KE, Wu AW, Galanos A, Desbiens NA, Phillips RS (2000) Age-related differences in care preferences, treatment decisions, and clinical outcomes of seriously ill hospitalized adults: lessons from SUPPORT J Am Geriatr Soc 48, 2000.

- Lissauer M, Smitz-Naranjo L, Johnson S (2011) Gender influences end-of-life decisions. In: Editor (ed)^(eds) Book Gender influences end-of-life decisions. Critical Care, City.

- 9: W, Mallinger JB, Krishnan A, Shields CG (2006) Attitudes toward life-sustaining interventions among ambulatory black and white patients Ethn Dis 16, 2006.

- 1: PV, Davis B, Wright K, Marcial E (1993) The influence of ethnicity and race on attitudes toward advance directives, life-prolonging treatments, and euthanasia J Clin Ethics 4, 1993.

- 6: ED, Garrett JM, Evans AT, Danis M (1996) Differences in end-of-life decision making among black and white ambulatory cancer patients J Gen Intern Med 11, 1996.

- 4: NC, Campbell DG, Caringi J (2022) A qualitative study of rural healthcare providers' views of social, cultural, and programmatic barriers to healthcare access BMC Health Serv Res 22, 2022.

- 4: NA, Lamont EB (2000) Extent and determinants of error in doctors' prognoses in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study BMJ 320, 2000.

- 1: RM, McClish DK, Bekes C, Scott WE, Morley JN (1991) Ego bias, reverse ego bias, and physicians' prognostic Crit Care Med 19, 1991.

- 4: GA, Cronin AM, Uno H, Schrag D, Keating NL, Mack JW (2016) Intensity of Medical Interventions between Diagnosis and Death in Patients with Advanced Lung and Colorectal Cancer: A CanCORS Analysis J Palliat Med 19, 2016.

- 2: DK, Samuel CA, Rosenstein DL, Dusetzina SB (2016) Investigation of Racial Disparities in Early Supportive Medication Use and End-of-Life Care Among Medicare Beneficiaries With Stage IV Breast Cancer J Clin Oncol 34, 2016.

- 7: LA, Yabes JG, Filippou P, Wulff-Burchfield EM, Lopa SH, Gore J, Davies BJ, Jacobs BL (2021) High-intensity end-of-life care among Medicare beneficiaries with bladder cancer Urol Oncol 39, 2021.

- 1: NL, Jhatakia S, Brooks GA, Tripp AS, Cintina I, Landrum MB, Zheng Q, Christian TJ, Glass R, Hsu VD, Kummet CM, Woodman S, Simon C, Hassol A, Oncology Care Model Evaluation T (2021) Association of Participation in the Oncology Care Model With Medicare Payments, Utilization, Care Delivery, and Quality Outcomes JAMA 326, 2021.

- e: B, Frytak J, Hayes J, Neubauer M, Robert N, Wilfong L (2020) Evaluation of Practice Patterns Among Oncologists Participating in the Oncology Care Model JAMA Netw Open 3, 2020.

- 1: AF, Jr, Dawson NV, Desbiens NA, Fulkerson WJ, Jr, Goldman L, Knaus WA, Lynn J, Oye RK, Bergner M, Damiano A, Hakim R, Murphy DJ, Teno J, Virnig B, Wagner DP, Wu AW, Yasui Y, Robinson DK, Kreling B, Dulac J, Baker R, Holayel S, Meeks T, Mustafa M, Vegarra J, Alzola C, Harrell FE, Jr, Cook EF, Hamel MB, Peterson L, Phillips RS, Tsevat J, Forrow L, Lesky L, Davis R, Kressin N, Solzan J, Puopolo AL, Barrett LQ, Bucko N, Brown D, Burns M, Foskett C, Hozid A, Keohane C, Martinez C, McWeeney D, Melia D, Otto S, Sheehan K, Smith A, Tofias L, Arthur B, Collins C, Cunnion M, Dyer D, Kulak C, Michaels M, O'Keefe M, Parker M, Tuchin L, Wax D, Weld D, Hiltunen L, Marks G, Mazzapica N, Medich C, Soukup J, Califf RM, Galanos AN, Kussin P, Muhlbaier LH, Winchell M, Mallatratt L, Akin E, Belcher L, Buller E, Clair E, Drew L, Fogelman L, Frye D, Fraulo B, Gessner D, Hamilton J, Kruse K, Landis D, Nobles L, Oliverio R, Wheeler C, Banks N, Berry S, Clayton M, Hartwell P, Hubbard N, Kussin I, Norman B, Noveau J, Read H, Warren B, Castle J, Turner K, Perdue R, Coulton C, Landefeld CS, Speroff T, Youngner S, Kennard MJ, Naccaratto M, Roach MJ, Blinkhorn M, Corrigan C, Geric E, Haas L, Ham J, Jerdonek J, Landy M, Marino E, Olesen P, Patzke S, Repas L, Schneeberger K, Smith C, Tyler C, Zenczak M, Anderson H, Carolin P, Johnson C, Leonard P, Leuenberger J, Palotta L, Warren M, Finley J, Ross T, Solem G, Zronek S, Davis S, Broste S, Layde P, Kryda M, Reding DJ, Vidaillet HJ, Jr, Folien M, Mowery P, Backus BE, Kempf DL, Kupfer JM, Maassen KE, Rohde JM, Wilke NL, Wilke SM, Albee EA, Backus B, Franz AM, Henseler DL, Herr JA, Leick I, Lezotte CL, Meddaugh L, Duffy L, Johnson D, Kronenwetter S, Merkel A, Bellamy PE, Hiatt J, Wenger NS, Leal-Sotelo M, Moranville-Hawkins D, Sheehan P, Watanabe D, Yamamoto MC, Adema A, Adkins E, Beckson A-M, Carter M, Duerr E, El-Hadad A, Farber A, Jackson A, Justice J, O'Meara A, Benson L, Cheney L, Medina C, Moriarty J, Baker K, Marsden C, Watne K, Goya D, Desbiens N, Fulkerson WJ, Carpenter CCJ, Carson RA, Detmer DE, Steinwachs DE, Mor V, Harootyan RA, Leaf A, Watts R, Williams S, Ransohoff D (1995) A Controlled Trial to Improve Care for Seriously III Hospitalized Patients: The Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT) JAMA 274, 1995.

- e: CR, Parikh RB, Small DS, Evans CN, Chivers C, Regli SH, Hanson CW, Bekelman JE, Rareshide CAL, O'Connor N, Schuchter LM, Shulman LN, Patel MS (2020) Effect of Integrating Machine Learning Mortality Estimates With Behavioral Nudges to Clinicians on Serious Illness Conversations Among Patients With Cancer: A Stepped-Wedge Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial JAMA Oncol 6, 2020.

- e: A, Xu X, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D, Wharam JF, Wagner AK (2021) Intensity of End-of-Life Care in a Cohort of Commercially Insured Women With Metastatic Breast Cancer in the United States JCO Oncol Pract 17, 2021.

| All Cancers (N=59,355) | Breast Cancer (N=4,862) | Colorectal Cancer (N=11,806) | Lung Cancer (N=39,330) | Prostate Cancer (N=3,357) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Characteristics | |||||

| NCI Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 3 (3) | 3 (2) | 3 (3) |

| Performance Status,No. (%) | |||||

| Not Poor | 35,753 (60.2%) | 2,449 (50.4%) | 6,132 (51.9%) | 25,022 (63.6%) | 2,150 (64.0%) |

| Poor | 23,602 (39.8%) | 2,413 (49.6%) | 5,674 (48.1%) | 14,308 (36.4%) | 1,207 (36.0%) |

| Stage at Diagnosis,No. (%) | |||||

| I-II | 10,182 (17.2%) | 1,540 (31.7%) | 2,554 (21.6%) | 5,173 (13.2%) | 915 (27.3%) |

| III | 13,391 (22.6%) | 920 (18.9%) | 2,649 (22.4%) | 9,722 (24.7%) | 100 (3.0%) |

| IV | 31,874 (53.7%) | 1,825 (37.5%) | 5,495 (46.5%) | 22,614 (57.5%) | 1,940 (57.8%) |

| Death within 6 Months of Diagnosis,No. (%) | |||||

| No | 31,534 (53.1%) | 3,595 (73.9%) | 6,677 (56.6%) | 18,512 (47.1%) | 2,750 (81.9%) |

| Yes | 27,821 (46.9%) | 1,267 (26.1%) | 5,129 (43.4%) | 20,818 (52.9%) | 607 (18.1%) |

| Demographic Characteristics | |||||

| Age at Diagnosis, mean years (SD) | 76 (8) | 77 (9) | 79 (8) | 76 (7) | 77 (8) |

| Age at Death, mean years (SD) | 77 (8) | 79 (9) | 80 (8) | 76 (7) | 79 (8) |

| Year of Death,No. (%) | |||||

| 2011 | 5,994 (10.1%) | 311 (6.4%) |

1,187 (10.1%) | 4,318 (11.0%) | 178 (5.3%) |

| 2012 | 11,099 (18.7%) | 679 (14.0%) | 2,078 (17.6%) | 7,859 (20.0%) | 483 (14.4%) |

| 2013 | 13,267 (22.4%) | 1,044 (21.5%) | 2,597 (22.0%) | 8,933 (22.7%) | 693 (20.6%) |

| 2014 | 14,130 (23.8%) | 1,286 (26.5%) | 2,883 (24.4%) | 9,016 (22.9%) | 945 (28.2%) |

| 2015 | 14,865 (25.0%) | 1,542 (31.7%) | 3,061 (25.9%) | 9,204 (23.4%) | 1,058 (31.5%) |

| Sex,No. (%) | |||||

| Female | 29,187 (49.2%) | 4,809 (98.9%) | 6,209 (52.6%) | 18,169 (46.2%) | 0.00 (0.0%) |

| Male | 30,168 (50.8%) | 53 (1.1%) |

5,597 (47.4%) | 21,161 (53.8%) | 3,357 (100.0%) |

| Race/Ethnicity,No. (%) | |||||

| White | 46,765 (78.8%) | 3,758 (77.3%) | 8,844 (74.9%) | 31,665 (80.5%) | 2,498 (74.4%) |

| Black | 5,863 (9.9%) | 616 (12.7%) | 1,328 (11.2%) | 3,453 (8.8%) | 466 (13.9%) |

| Hispanic | 3,261 (5.5%) | 274 (5.6%) |

855 (7.2%) |

1,892 (4.8%) | 240 (7.1%) |

| Other^ | 3,466 (5.8%) | 214 (4.4%) |

779 (6.6%) |

2,320 (5.9%) | 153 (4.6%) |

| Marital Status,No. (%) | |||||

| Married | 27,345 (46.1%) | 1,556 (32.0%) | 4,851 (41.1%) | 19,123 (48.6%) | 1,815 (54.1%) |

| Not Married | 28,942 (48.8%) | 2,957 (60.8%) | 6,340 (53.7%) | 18,507 (47.1%) | 1,138 (33.9%) |

| Geographic/Socioeconomic Characteristics | |||||

| U.S. Region at Death,No. (%) | |||||

| Northeast | 10,936 (18.4%) | 968 (19.9%) | 2,297 (19.5%) | 7,056 (17.9%) | 615 (18.3%) |

| Midwest | 7,337 (12.4%) | 606 (12.5%) | 1,436 (12.2%) | 4,898 (12.5%) | 397 (11.8%) |

| South | 17,370 (29.3%) | 1,349 (27.7%) | 3,113 (26.4%) | 12,050 (30.6%) | 858 (25.6%) |

| West | 23,679 (39.9%) | 1,936 (39.8%) | 4,951 (41.9%) | 15,306 (38.9%) | 1,486 (44.3%) |

| Population in County of Residence,No. (%) | |||||

| 249,999 or less | 16,477 (27.8%) | 1,231 (25.3%) | 3,136 (26.6%) | 11,195 (28.5%) | 915 (27.3%) |

| 250,000 to 999,999 | 12,507 (21.1%) | 1,014 (20.9%) | 2,473 (20.9%) | 8,298 (21.1%) | 722 (21.5%) |

| 1,000,000 or more | 30,318 (51.1%) | 2,613 (53.7%) | 6,183 (52.4%) | 19,804 (50.4%) | 1,718 (51.2%) |

| Rural/Urban Area at Diagnosis,No. (%) | |||||

| All rural | 5,425 (9.1%) | 374 (7.7%) |

993 (8.4%) |

3,761 (9.6%) | 297 (8.8%) |

| All urban | 34,935 (58.9%) | 2,917 (60.0%) | 7,194 (60.9%) | 22,907 (58.2%) | 1,917 (57.1%) |

| Mostly rural | 5,100 (8.6%) | 348 (7.2%) |

889 (7.5%) |

3,564 (9.1%) | 299 (8.9%) |

| Mostly urban | 13,058 (22.0%) | 1,021 (21.0%) | 2,590 (21.9%) | 8,731 (22.2%) | 716 (21.3%) |

| Poverty,No. (%) | |||||

| 0%-<5% poverty | 10,204 (17.2%) | 918 (18.9%) | 2,032 (17.2%) | 6,634 (16.9%) | 620 (18.5%) |

| 5% to <10% poverty | 14,420 (24.3%) | 1,234 (25.4%) | 2,856 (24.2%) | 9,497 (24.1%) | 833 (24.8%) |

| 10% to <20% poverty | 18,223 (30.7%) | 1,371 (28.2%) | 3,625 (30.7%) | 12,237 (31.1%) | 990 (29.5%) |

| 20% to 100% poverty | 15,092 (25.4%) | 1,243 (25.6%) | 3,048 (25.8%) | 9,943 (25.3%) | 858 (25.6%) |

| State Buy-in,No. (%) | |||||

| No | 45,838 (77.2%) | 3,640 (74.9%) | 8,748 (74.1%) | 30,745 (78.2%) | 2,705 (80.6%) |

| Yes | 13,517 (22.8%) | 1,222 (25.1%) | 3,058 (25.9%) | 8,585 (21.8%) | 652 (19.4%) |

| All Cancers | Breast | Colorectal | Lung | Prostate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI) | Coefficient (95% CI) | Coefficient (95% CI) | Coefficient (95% CI) | Coefficient (95% CI) | |

| Clinical Predictors | |||||

| NCI Comorbidity Index | 1.06*** (1.03 to 1.09) |

0.99*** (0.87 to 1.10) |

1.07*** (0.99 to 1.15) |

1.10*** (1.06 to 1.14) |

0.94*** (0.80 to 1.08) |

| Performance Status | |||||

| Not Poor | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] |

| Poor | -5.36*** (-5.53 to -5.20) |

-4.62*** (-5.18 to -4.06) |

-6.31*** (-6.71 to -5.92) |

-5.33*** (-5.52 to -5.13) |

-4.43*** (-5.17 to -3.68) |

| Stage at Diagnosis | |||||

| I-II | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] |

| III | 0.37** (0.13 to 0.61) |

0.52 (-0.20 to 1.25) |

-0.83** (-1.38 to -0.29) |

0.89*** (0.58 to 1.19) |

0.82 (-1.21 to 2.85) |

| IV | 0.39*** (0.18 to 0.60) |

1.62*** (1.01 to 2.23) |

-1.72*** (-2.20 to -1.24) |

1.09*** (0.81 to 1.37) |

1.04** (0.26 to 1.81) |

| Demographic Predictors | |||||

| Age at Diagnosis | -0.05*** (-0.06 to -0.04) |

-0.16*** (-0.19 to -0.13) |

-0.04** (-0.06 to -0.01) |

-0.06*** (-0.07 to -0.05) |

-0.08*** (-0.12 to -0.03) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | |

| Female | 0.33*** (0.16 to 0.49) |

1.97 (-0.69 to 4.62) |

0.18 (-0.22 to 0.58) |

0.34*** (0.15 to 0.54) |

|

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] |

| Black | 0.91*** (0.63 to 1.19) |

1.72*** (0.83 to 2.61) |

0.50 (-0.15 to 1.15) |

0.87*** (0.52 to 1.21) |

0.80 (-0.36 to 1.96) |

| Hispanic | 0.03 (-0.33 to 0.38) |

-0.33 (-1.53 to 0.88) |

-0.46 (-1.23 to 0.31) |

0.18 (-0.26 to 0.63) |

-0.66 (-2.11 to 0.79) |

| Other^ | 0.91*** (0.56 to 1.27) |

-0.17 (-1.55 to 1.22) |

0.13 (-0.68 to 0.95) |

1.20*** (0.78 to 1.62) |

1.07 (-0.69 to 2.82) |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] |

| Not Married | 0.16 (-0.01 to 0.33) |

-0.33 (-0.92 to 0.27) |

0.14 (-0.27 to 0.55) |

0.20* (0.00 to 0.40) |

0.15 (-0.60 to 0.89) |

| Geographic/Socioeconomic Predictors | |||||

| U.S. Region at Death | |||||

| Northeast | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] |

| Midwest | -1.40*** (-1.69 to -1.11) |

-1.25** (-2.22 to -0.27) |

-1.62*** (-2.33 to -0.92) |

-1.36*** (-1.70 to -1.01) |

-1.18 (-2.5 to 0.14) |

| South | -2.32*** (-2.59 to -2.06) |

-2.16*** (-3.06 to -1.27) |

-2.30*** (-2.94 to -1.66) |

-2.26*** (-2.57 to -1.95) |

-2.53*** (-3.74 to -1.32) |

| West | -0.66*** (-0.89 to -0.43) |

-0.37 (-1.14 to 0.41) |

-0.74** (-1.28 to -0.19) |

-0.67*** (-0.94 to -0.40) |

-0.21 (-1.23 to 0.82) |

| Population in County of Residence | |||||

| 249,999 or less | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] |

| 250,000 – 999,999 | 0.56*** (0.32 to 0.81) |

0.83 (-0.03 to 1.70) |

1.07*** (0.46 to 1.68) |

0.46** (0.17 to 0.75) |

-0.18 (-1.29 to 0.93) |

| 1,000,000 or more | 1.33*** (1.10 to 1.57) |

1.91*** (1.09 to 2.73) |

1.44*** (0.86 to 2.03) |

1.23*** (0.95 to 1.51) |

1.17* (0.11 to 2.24) |

| Rural/Urban Area at Diagnosis | |||||

| All urban | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] |

| All rural | -0.62*** (-0.95 to -0.30) |

0.09 (-1.09 to 1.27) |

-0.65 (-1.45 to 0.15) |

-0.61*** (-0.98 to -0.23) |

-1.97** (-3.4 to -0.53) |

| Mostly rural | -0.77*** (-1.08 to -0.46) |

0.79 (-0.33 to 1.91) |

-0.65 (-1.45 to 0.15) |

-0.93*** (-1.29 to -0.57) |

-0.87 (-2.22 to 0.48) |

| Mostly urban | -0.55*** (-0.76 to -0.34) |

-0.43 (-1.15 to 0.29) |

-0.39 (-0.91 to 0.13) |

-0.59*** (-0.84 to -0.34) |

-1.15* (-2.11 to -0.19) |

| Poverty | |||||

| 0% – <5% poverty | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] |

| 5% – <10% poverty | -0.10 (-0.35 to 0.14) |

-0.27 (-1.08 to 0.53) |

0.16 (-0.44 to 0.76) |

-0.11 (-0.40 to 0.18) |

-1.22* (-2.3 to -0.15) |

| 10% – <20% poverty | 0.07 (-0.18 to 0.31) |

0.48 (-0.35 to 1.31) |

0.76* (0.16 to 1.35) |

-0.19 (-0.48 to 0.10) |

-0.45 (-1.55 to 0.65) |

| 20% – 100% poverty | 0.09 (-0.18 to 0.36) |

-0.03 (-0.94 to 0.89) |

1.05** (0.40 to 1.70) |

-0.14 (-0.46 to 0.18) |

-0.90 (-2.09 to 0.3) |

| State Buy-in | |||||

| No | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] |

| Yes | 0.72*** (0.52 to 0.93) |

0.31 (-0.38 to 1.00) |

0.18 (-0.30 to 0.66) |

0.86*** (0.61 to 1.10) |

1.19* (0.2 to 2.18) |

| All Cancers | Breast | Colorectal | Lung | Prostate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI) | Coefficient (95% CI) | Coefficient (95% CI) | Coefficient (95% CI) | Coefficient (95% CI) | |

| Clinical Predictors | |||||

| NCI Comorbidity Index | 0.94*** (0.89 to 0.98) |

0.90*** (0.69 to 1.11) |

0.82*** (0.71 to 0.93) |

1.01*** (0.96 to 1.07) |

0.79*** (0.49 to 1.09) |

| Performance Status | |||||

| Not Poor | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] |

| Poor | -4.98*** (-5.24 to -4.73) |

-3.83*** (-4.89 to -2.76) |

-5.81*** (-6.41 to -5.20) |

-5.00*** (-5.29 to -4.72) |

-4.39*** (-6.08 to -2.69) |

| Stage at Diagnosis | |||||

| I-II | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] |

| III | -1.35*** (-1.78 to -0.92) |

0.81 (-1.09 to 2.70) |

-0.55 (-1.41 to 0.32) |

-0.25 (-0.80 to 0.29) |

7.53 (-2.20 to 17.26) |

| IV | -2.24*** (-2.62 to -1.86) |

0.86 (-0.58 to 2.30) |

-4.71*** (-5.43 to -4.00) |

-0.60* (-1.10 to -0.10) |

4.02*** (1.90 to 6.14) |

| Demographic Predictors | |||||

| Age at Diagnosis | -0.08*** (-0.10 to -0.06) |

-0.20*** (-0.26 to -0.13) |

-0.05** (-0.09 to -0.02) |

-0.12*** (-0.14 to -0.10) |

-0.04 (-0.14 to 0.06) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | |

| Female | 0.49*** (0.26 to 0.72) |

1.44 (-3.87 to 6.76) |

-0.12 (-0.71 to 0.46) |

0.59*** (0.33 to 0.85) |

|

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] |

| Black | 0.66** (0.26 to 1.07) |

0.83 (-0.79 to 2.45) |

0.23 (-0.74 to 1.20) |

0.66** (0.19 to 1.12) |

0.87 (-1.57 to 3.31) |

| Hispanic | -0.12 (-0.64 to 0.40) |

-1.89 (-4.28 to 0.50) |

-1.37* (-2.55 to -0.19) |

0.27 (-0.33 to 0.86) |

-1.07 (-4.36 to 2.22) |

| Other^ | 0.72** (0.20 to 1.23) |

-1.28 (-4.00 to 1.44) |

0.27 (-0.98 to 1.52) |

0.97*** (0.40 to 1.54) |

2.67 (-2.85 to 8.19) |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] |

| Not Married | 0.08 (-0.16 to 0.32) |

0.42 (-0.70 to 1.55) |

0.06 (-0.54 to 0.66) |

0.01 (-0.26 to 0.27) |

-0.25 (-1.83 to 1.34) |

| Geographic/Socioeconomic Predictors | |||||

| U.S. Region at Death | |||||

| Northeast | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] |

| Midwest | -1.66*** (-2.07 to -1.24) |

-2.08* (-3.81 to -0.35) |

-1.58** (-2.60 to -0.57) |

-1.65*** (-2.12 to -1.18) |

-2.36 (-5.37 to 0.65) |

| South | -2.83*** (-3.21 to -2.46) |

-3.71*** (-5.29 to -2.12) |

-2.27*** (-3.21 to -1.34) |

-2.72*** (-3.15 to -2.30) |

-5.02*** (-7.71 to -2.34) |

| West | -0.92*** (-1.25 to -0.59) |

-1.26 (-2.66 to 0.14) |

-0.97* (-1.77 to -0.17) |

-0.85*** (-1.22 to -0.47) |

-1.50 (-3.81 to 0.82) |

| Population in County of Residence | |||||

| 249,999 or less | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] |

| 250,000 – 999,999 | 0.42* (0.07 to 0.77) |

1.19 (-0.42 to 2.80) |

0.60 (-0.28 to 1.48) |

0.36 (-0.03 to 0.75) |

-0.10 (-2.53 to 2.34) |

| 1,000,000 or more | 1.25*** (0.91 to 1.58) |

1.67* (0.15 to 3.19) |

1.34** (0.49 to 2.20) |

1.22*** (0.85 to 1.60) |

1.31 (-0.99 to 3.61) |

| Rural/Urban Area at Diagnosis | |||||

| All urban | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] |

| All rural | -0.60* (-1.05 to -0.14) |

1.00 (-1.16 to 3.16) |

-1.20* (-2.35 to -0.04) |

-0.58* (-1.09 to -0.07) |

-2.05 (-5.51 to 1.41) |

| Mostly rural | -0.79** (-1.23 to -0.34) |

1.24 (-0.83 to 3.31) |

-1.24* (-2.41 to -0.08) |

-0.76** (-1.26 to -0.27) |

-0.68 (-3.90 to 2.55) |

| Mostly urban | -0.48** (-0.79 to -0.18) |

-0.17 (-1.53 to 1.19) |

-0.85* (-1.60 to -0.09) |

-0.49** (-0.83 to -0.15) |

-0.61 (-2.61 to 1.38) |

| Poverty | |||||

| 0% – <5% poverty | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] |

| 5% – <10% poverty | -0.02 (-0.38 to 0.34) |

-0.62 (-2.11 to 0.86) |

0.09 (-0.79 to 0.97) |

0.02 (-0.38 to 0.42) |

0.23 (-2.19 to 2.65) |

| 10% – <20% poverty | 0.08 (-0.28 to 0.43) |

-0.50 (-2.03 to 1.03) |

0.84 (-0.04 to 1.71) |

-0.12 (-0.52 to 0.28) |

1.29 (-1.31 to 3.89) |

| 20% – 100% poverty | 0.12 (-0.27 to 0.51) |

0.34 (-1.40 to 2.07) |

0.76 (-0.19 to 1.72) |

-0.10 (-0.54 to 0.34) |

1.73 (-0.92 to 4.39) |

| State Buy-in | |||||

| No | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] | 0 [Reference] |

| Yes | 0.75*** (0.46 to 1.04) |

0.02 (-1.27 to 1.31) |

0.54 (-0.17 to 1.25) |

0.83*** (0.50 to 1.16) |

0.00 (-2.19 to 2.20) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).