Submitted:

11 January 2025

Posted:

13 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

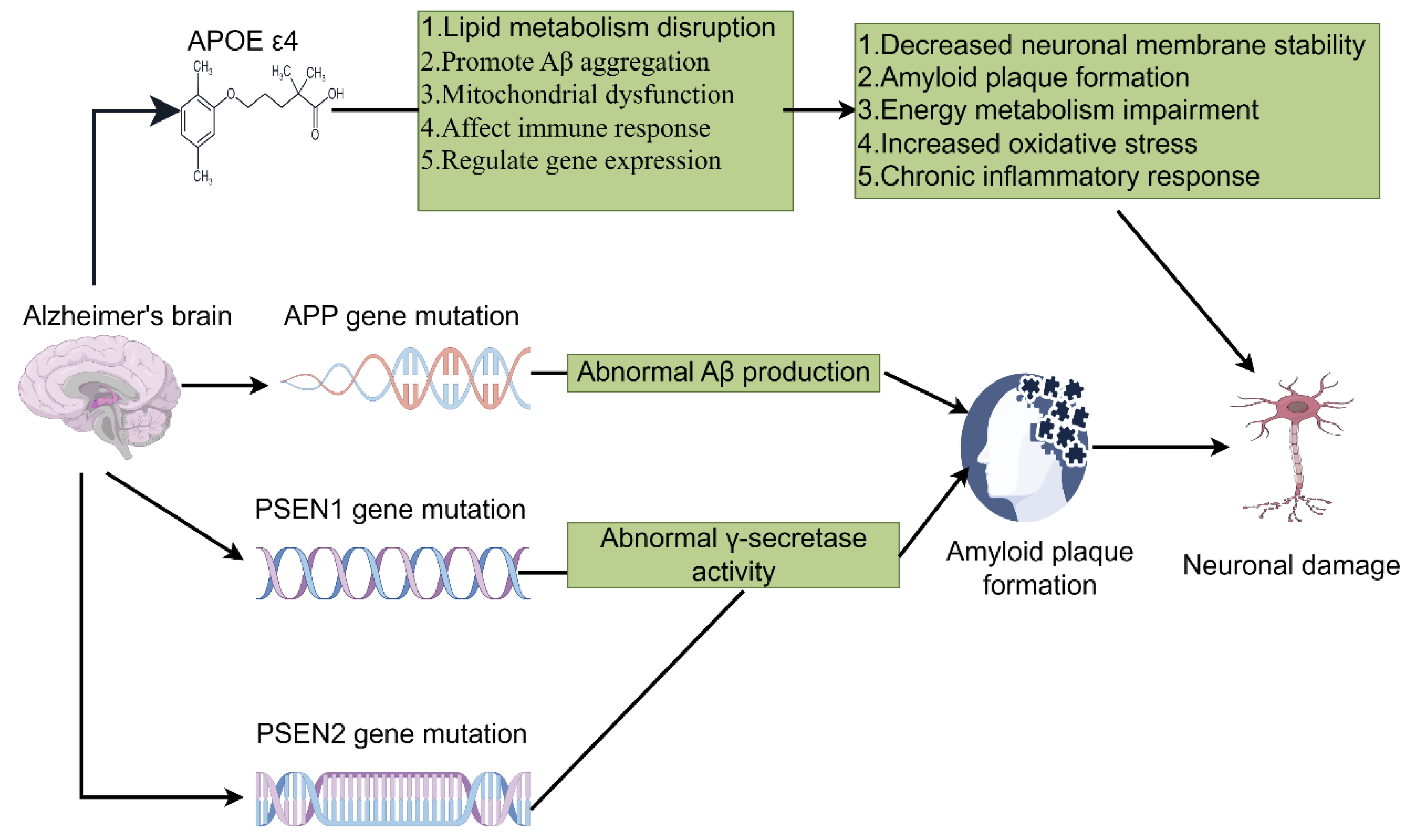

2. Genetic Background and Immune System in AD

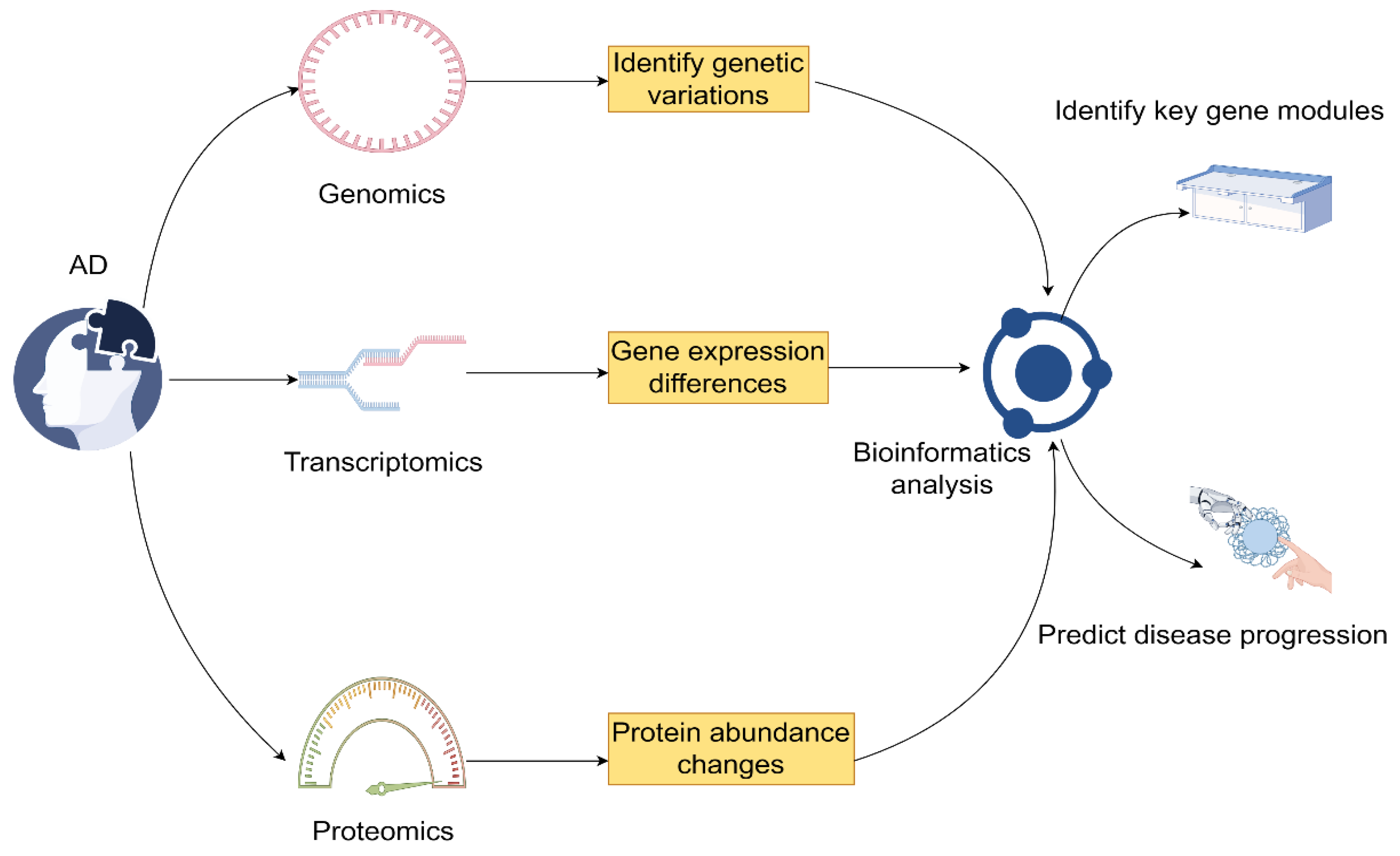

3. Integrated Analysis of Genetic and Immune Profiles

3.1. Integration Methods for Multi-Omics Data

3.2. Identification and Validation of Biomarkers

3.3. Patient Stratification and Precision Therapeutics

4. Current Status and Future Prospects of Immunotherapy in AD

4.1. Types and Mechanisms of Immunotherapeutic Approaches

4.2. Review and Analysis of Clinical Trials

4.3. Strategies and Future Directions for Personalized Immunotherapy

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

References

- Global Nutrition Target, C. Global, regional, and national progress towards the 2030 global nutrition targets and forecasts to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2025, 404, 2543–2583. [Google Scholar]

- Synnott, P.G.; Majda, T.; Lin, P.J.; Ollendorf, D.A.; Zhu, Y.; Kowal, S. Modeling the Population Equity of Alzheimer Disease Treatments in the US. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7, e2442353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiri, S.; Ghaffari Jolfayi, A.; Fazlollahi, A.; Morsali, S.; Sarkesh, A.; Daei Sorkhabi, A.; Golabi, B.; Aletaha, R.; Motlagh Asghari, K.; Hamidi, S.; Mousavi, S.E.; Jamalkhani, S.; Karamzad, N.; Shamekh, A.; Mohammadinasab, R.; Sullman, M.J.M.; Sahin, F.; Kolahi, A.A. Alzheimer's disease: a comprehensive review of epidemiology, risk factors, symptoms diagnosis, management, caregiving, advanced treatments and associated challenges. Front Med (Lausanne) 2024, 11, 1474043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, M.J.; Lipnicki, D.M.; Lam, B.C.P.; Crawford, J.D.; Schutte, A.E.; Peters, R.; Rydberg-Sterner, T.; Najar, J.; Skoog, I.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Rohr, S.; Pabst, A.; Lobo, A.; De-la-Camara, C.; Lobo, E.; Lipton, R.B.; Katz, M.J.; Derby, C.A.; Kim, K.W.; Han, J.W.; Oh, D.J.; Rolandi, E.; Davin, A.; Rossi, M.; Scarmeas, N.; Yannakoulia, M.; Dardiotis, T.; Hendrie, H.C.; Gao, S.; Carriere, I.; Ritchie, K.; Anstey, K.J.; Cherbuin, N.; Xiao, S.; Yue, L.; Li, W.; Guerchet, M.; Preux, P.M.; Aboyans, V.; Haan, M.N.; Aiello, A.; Scazufca, M.; Sachdev, P.S.; as the Cohort Studies of Memory in an International Consortium, G. Blood Pressure, Antihypertensive Use, and Late-Life Alzheimer and Non-Alzheimer Dementia Risk: An Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis. Neurology 2024, 103, e209715. [Google Scholar]

- Landeiro, F.; Harris, C.; Groves, D.; O'Neill, S.; Jandu, K.S.; Tacconi, E.M.C.; Field, S.; Patel, N.; Gopfert, A.; Hagson, H.; Leal, J.; Luengo-Fernandez, R. The economic burden of cancer, coronary heart disease, dementia, and stroke in England in 2018, with projection to 2050: an evaluation of two cohort studies. Lancet Healthy Longev 2024, 5, e514–e523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collaborators, G.U.B. o. D. The burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors by state in the USA, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 404, 2314–2340. [Google Scholar]

- Knecht, L.; Dalsbol, K.; Simonsen, A.H.; Pilchner, F.; Ross, J.A.; Winge, K.; Salvesen, L.; Bech, S.; Hejl, A.M.; Lokkegaard, A.; Hasselbalch, S.G.; Dodel, R.; Aznar, S.; Waldemar, G.; Brudek, T.; Folke, J. Autoantibody profiles in Alzheimer s, Parkinson s, and dementia with Lewy bodies: altered IgG affinity and IgG/IgM/IgA responses to alpha-synuclein, amyloid-beta, and tau in disease-specific pathological patterns. J Neuroinflammation 2024, 21, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mroke, P.; Goit, R.; Rizwan, M.; Tariq, S.; Rizwan, A.W.; Umer, M.; Nassar, F.F.; Torijano Sarria, A.J.; Singh, D.; Baig, I. Implications of the Gut Microbiome in Alzheimer's Disease: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e73681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Bai, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, R.; Zhu, S.; Li, T.; Zhang, M. The Relationship Between Alzheimer's Disease and Pyroptosis and the Intervention Progress of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Int J Gen Med 2024, 17, 4723–4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Gong, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, Y.; Sun, R.; Zhang, H.; Shang, J.; Zhang, J. Mutant NOTCH3ECD Triggers Defects in Mitochondrial Function and Mitophagy in CADASIL Cell Models. J Alzheimers Dis 2024, 100, 1299–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Chen, N.; Wang, C. Frontiers and hotspots evolution in anti-inflammatory studies for Alzheimer's disease. Behav Brain Res 2024, 472, 115178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.P.; Liu, X.H.; Ren, M.J.; Liu, X.T.; Shi, X.Q.; Li, M.L.; Li, S.A.; Yang, Y.; Wang, D.D.; Wu, Y.; Yin, F.X.; Guo, Y.H.; Yang, R.Z.; Cheng, M.; Xin, Y.J.; Kang, J.S.; Huang, B.; Ren, K.D. Neuronal cathepsin S increases neuroinflammation and causes cognitive decline via CX3CL1-CX3CR1 axis and JAK2-STAT3 pathway in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Aging Cell 2024, e14393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierre, R.C.; Rocha, P.R.; Graciani, A.L.; Coppi, A.A.; Arida, R.M. Tau, amyloid, iron, oligodendrocytes ferroptosis, and inflammaging in the hippocampal formation of aged rats submitted to an aerobic exercise program. Brain Res 2024, 1850, 149419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.W.; Khatib, L.A.; Heston, M.B.; Dilmore, A.H.; Labus, J.S.; Deming, Y.; Schimmel, L.; Blach, C.; McDonald, D.; Gonzalez, A.; Bryant, M.; Sanders, K.; Schwartz, A.; Ulland, T.K.; Johnson, S.C.; Asthana, S.; Carlsson, C.M.; Chin, N.A.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Rey, F.E.; Alzheimer Gut Microbiome Project, C.; Kaddurah-Daouk, R.; Knight, R.; Bendlin, B.B. Gut Microbiome Compositional and Functional Features Associate with Alzheimer's Disease Pathology. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaro-Ruiz, R.; Martin-Belmonte, A.; Aguado, C.; Moreno-Martinez, A.E.; Fukazawa, Y.; Lujan, R. Selective disruption of synaptic NMDA receptors of the hippocampal trisynaptic circuit in Abeta pathology. Biol Res 2024, 57, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.; Choe, K.; Park, J.S.; Park, H.Y.; Kang, H.; Park, T.J.; Kim, M.O. The Interplay of Protein Aggregation, Genetics, and Oxidative Stress in Alzheimer's Disease: Role for Natural Antioxidants and Immunotherapeutics. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Li, W.; Wu, W.; Liu, Q.; You, M.; Liu, X.; Ye, C.; Chen, J.; Tan, Q.; Liu, G.; Du, Y. Effects of electroacupuncture on microglia phenotype and epigenetic modulation of C/EBPbeta in SAMP8 mice. Brain Res 2024, 1849, 149339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haessler, A.; Candlish, M.; Hefendehl, J.K.; Jung, N.; Windbergs, M. Mapping cellular stress and lipid dysregulation in Alzheimer-related progressive neurodegeneration using label-free Raman microscopy. Commun Biol 2024, 7, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilton, P.M.; Ghare, S.S.; Charpentier, B.T.; Myers, S.A.; Rao, A.V.; Petrosino, J.F.; Hoffman, K.L.; Greenwell, J.C.; Tyagi, N.; Behera, J.; Wang, Y.; Sloan, L.J.; Zhang, J.; Shields, C.B.; Cooper, G.E.; Gobejishvili, L.; Whittemore, S.R.; McClain, C.J.; Barve, S.S. Age-associated temporal decline in butyrate-producing bacteria plays a key pathogenic role in the onset and progression of neuropathology and memory deficits in 3xTg-AD mice. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2389319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.H.; Ding, G.Y.; Chen, S.Y.; Liu, X.L.; Zhang, M.; Tang, H.D. Blood Cathepsins on the Risk of Alzheimer's Disease and Related Pathological Biomarkers: Results from Observational Cohort and Mendelian Randomization Study. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2024, 11, 1834–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vida, H.; Sahar, M.; Nikdouz, A.; Arezoo, H. Chemokines in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunol Cell Biol 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Luo, B.; Fei, L.; Zhang, Q.; Liang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, X. MS4A superfamily molecules in tumors, Alzheimer's and autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1481494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammers, D.B.; Eloyan, A.; Thangarajah, M.; Taurone, A.; Beckett, L.; Gao, S.; Polsinelli, A.J.; Kirby, K.; Dage, J.L.; Nudelman, K.; Aisen, P.; Reman, R.; La Joie, R.; Lagarde, J.; Atri, A.; Clark, D.; Day, G.S.; Duara, R.; Graff-Radford, N.R.; Honig, L.S.; Jones, D.T.; Masdeu, J.C.; Mendez, M.F.; Womack, K.; Musiek, E.; Onyike, C.U.; Riddle, M.; Grant, I.; Rogalski, E.; Johnson, E.C.B.; Salloway, S.; Sha, S.J.; Turner, R.S.; Wingo, T.S.; Wolk, D.A.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dickerson, B.C.; Rabinovici, G.D.; Apostolova, L.G.; Initiative, L.C. f. t. A. s. D. N. Differences in baseline cognitive performance between participants with early-onset and late-onset Alzheimer's disease: Comparison of LEADS and ADNI. Alzheimers Dement 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqabandi, J.A.; David, R.; Abdel-Motal, U.M.; ElAbd, R.O.; Youcef-Toumi, K. An innovative cellular medicine approach via the utilization of novel nanotechnology-based biomechatronic platforms as a label-free biomarker for early melanoma diagnosis. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 30107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hrybouski, S.; Das, S.R.; Xie, L.; Brown, C.A.; Flamporis, M.; Lane, J.; Nasrallah, I.M.; Detre, J.A.; Yushkevich, P.A.; Wolk, D.A. BOLD Amplitude Correlates of Preclinical Alzheimer's Disease. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Heneka, M.T.; Morgan, D.; Jessen, F. Passive anti-amyloid beta immunotherapy in Alzheimer's disease-opportunities and challenges. Lancet 2024, 404, 2198–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, H.; Zhong, M.; Lin, J.; Hu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Gan, C.L. Epileptic seizures induced by pentylenetetrazole kindling accelerate Alzheimer-like neuropathology in 5xFAD mice. Front Pharmacol 2024, 15, 1500105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Qi, Y.; Hu, Y.; Qiu, X.; Qiu, T.; Li, S.; Liu, M.; Jia, Q.; Sun, B.; Liu, C.; Li, T.; Le, W.; Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging, I. Integrated cerebellar radiomic-network model for predicting mild cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisen, P.; Bateman, R.J.; Crowther, D.; Cummings, J.; Dwyer, J.; Iwatsubo, T.; Kosco-Vilbois, M.; McDade, E.; Mohs, R.; Scheltens, P.; Sperling, R.; Selkoe, D. The case for regulatory approval of amyloid-lowering immunotherapies in Alzheimer's disease based on clearcut biomarker evidence. Alzheimers Dement 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosheny, R.L.; Miller, M.; Conti, C.; Flenniken, D.; Ashford, M.; Diaz, A.; Fockler, J.; Truran, D.; Kwang, W.; Kanoria, S.; Veitch, D.; Green, R.C.; Weiner, M.W.; Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging, I. The ADNI Administrative Core: Ensuring ADNI's success and informing future AD clinical trials. Alzheimers Dement 2024, 20, 9004–9013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menendez-Gonzalez, M. Therapeutic Challenges Derived from the Interaction Among Apolipoprotein E, Cholesterol, and Amyloid in Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carracedo, S.; Launay, A.; Dechelle-Marquet, P.A.; Faivre, E.; Blum, D.; Delarasse, C.; Boue-Grabot, E. Purinergic-associated immune responses in neurodegenerative diseases. Prog Neurobiol 2024, 243, 102693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Xu, S.; Lan, Z.; Fang, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, X. Apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer's Disease: Focus on Synaptic Function and Therapeutic Strategy. Mol Neurobiol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xia, Y.; Gui, Y. Neuronal ApoE4 in Alzheimer's disease and potential therapeutic targets. Front Aging Neurosci 2023, 15, 1199434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.Y.; Wang, Z.; Huang, H.C. Roles of ApoE4 on the Pathogenesis in Alzheimer's Disease and the Potential Therapeutic Approaches. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2023, 43, 3115–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, F.F. The problem of multiple adjustments in the assessment of minimal clinically important differences. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2025, 11, e70032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, L.; Lelo de Larrea-Mancera, E.S.; Maniglia, M.; Vodyanyk, M.M.; Gallun, F.J.; Jaeggi, S.M.; Seitz, A.R. Multidimensional relationships between sensory perception and cognitive aging. Front Aging Neurosci 2024, 16, 1484494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabouri, S.; Rostamirad, M.; Dempski, R.E. Unlocking the brain's zinc code: implications for cognitive function and disease. Front Biophys 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y. Mapping the current trends and hotspots of extracellular vesicles in Alzheimer's disease: a bibliometric analysis. Front Aging Neurosci 2024, 16, 1485750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdes, P.; Caldwell, A.B.; Liu, Q.; Fitzgerald, M.Q.; Ramachandran, S.; Karch, C.M.; Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer, N.; Galasko, D.R.; Yuan, S.H.; Wagner, S.L.; Subramaniam, S. Integrative multiomics reveals common endotypes across PSEN1, PSEN2, and APP mutations in familial Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther 2025, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, S.; Jiao, B. APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 Variants in Alzheimer's Disease: Systematic Re-evaluation According to ACMG Guidelines. Front Aging Neurosci 2021, 13, 695808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullan, M.; Crawford, F.; Buchanan, J. Technical feasibility of genetic testing for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1994, 8, 102–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutton, M.; Hardy, J. The presenilins and Alzheimer's disease. Hum Mol Genet 1997, 6, 1639–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Sterling, K.; Song, W. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in Alzheimer's disease and its pharmaceutical potential. Transl Neurodegener 2022, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weninger, S.; Irizarry, M.C.; Fleisher, A.S.; Leon, T.; Maruff, P.; Miller, D.S.; Seleri, S.; Carrillo, M.C.; Weber, C.J. Alzheimer's disease drug development in an evolving therapeutic landscape. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2024, 10, e70015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhakal, U.; Briceno, E.; Sharma, U.; Bogati, U.; Sharma, A.; Shrestha, L.; Ghimire, D.; Mendes de Leon, C.F. Health care systems and policies for older adults in Nepal: new challenges for a low-middle income country. Discov Public Health 2024, 21, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, T.K.S.; Udeh-Momoh, C.; Lim, M.A.; Gleerup, H.S.; Leifert, W.; Ajalo, C.; Ashton, N.; Zetterberg, H.; Rissman, R.A.; Winston, C.N.; S, O.B.; Jenkins, R.; Carro, E.; Orive, G.; Tamburin, S.; Olvera-Rojas, M.; Solis-Urra, P.; Esteban-Cornejo, I.; Santos, G.; Rajan, K.B.; Koh, D.; Simonsen, A.H.; Slowey, P.D.; et al. Guidelines for the standardization of pre-analytical variables for salivary biomarker studies in Alzheimer's disease research: An updated review and consensus of the Salivary Biomarkers for Dementia Research Working Group. Alzheimers Dement 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgorzynska, E. TREM2 in Alzheimer's disease: Structure, function, therapeutic prospects, and activation challenges. Mol Cell Neurosci 2024, 128, 103917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesinghe, P.; Li, H.R.; Ai, Z.; Campbell, M.; Chen, S.X.; Xi, J.; Pham, W.; Matsubara, J.A. Apolipoprotein E dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease: a study on miRNA regulation, glial markers, and amyloid pathology. Front Aging Neurosci 2024, 16, 1495615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Xi, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, J. Identification of potential therapeutic targets for Alzheimer's disease from the proteomes of plasma and cerebrospinal fluid in a multicenter Mendelian randomization study. Int J Biol Macromol 2025, 139394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roveta, F.; Bonino, L.; Piella, E.M.; Rainero, I.; Rubino, E. Neuroinflammatory Biomarkers in Alzheimer's Disease: From Pathophysiology to Clinical Implications. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Guo, Q.; Tian, J.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. TREM2 bridges microglia and extracellular microenvironment: Mechanistic landscape and therapeutical prospects on Alzheimer's disease. Ageing Res Rev 2025, 103, 102596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.H.; Liu, X.Y.; Tuo, J.M.; Li, J.H.; Tu, Y.F.; Tan, Q.; Ma, Y.Y.; Bai, Y.D.; Xin, J.Y.; Huang, S.; Zeng, G.H.; Shi, A.Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.H.; Bu, X.L.; Ye, L.L.; Wan, Y.; Liu, T.F.; Chen, X.W.; Qiu, Z.L.; Gao, C.Y.; Wang, Y.J. Roles of blood monocytes carrying TREM2(R47H) mutation in pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease and its therapeutic potential in APP/PS1 mice. Alzheimers Dement 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Beydoun, M.A.; Beydoun, H.A.; Li, Z.; Hu, Y.H.; Noren Hooten, N.; Ding, J.; Hossain, S.; Maino Vieytes, C.A.; Launer, L.J.; Evans, M.K.; Zonderman, A.B. Alzheimer's Disease polygenic risk, the plasma proteome, and dementia incidence among UK older adults. Geroscience 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagyinszky, E.; An, S.S.A. Haploinsufficiency and Alzheimer's Disease: The Possible Pathogenic and Protective Genetic Factors. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baligacs, N.; Albertini, G.; Borrie, S.C.; Serneels, L.; Pridans, C.; Balusu, S.; De Strooper, B. Homeostatic microglia initially seed and activated microglia later reshape amyloid plaques in Alzheimer's Disease. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 10634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.C.; Huang, L.Y.; Guo, H.H.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Hao, Q.; Tan, C.C.; Tan, L. Higher CSF sTREM2 attenuates APOE epsilon4-related risk for amyloid pathology in cognitively intact adults: The CABLE study. J Neurochem 2025, 169, e16273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, M.; Miller, G.W.; Vardarajan, B.N.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Guo, Z.; Liu, Z. Deciphering proteins in Alzheimer's disease: A new Mendelian randomization method integrated with AlphaFold3 for 3D structure prediction. Cell Genom 2024, 4, 100700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenoun, D.; Blaise, N.; Sellam, A.; Roupret-Serzec, J.; Jacquens, A.; Steenwinckel, J.V.; Gressens, P.; Bokobza, C. Microglial Depletion, a New Tool in Neuroinflammatory Disorders: Comparison of Pharmacological Inhibitors of the CSF-1R. Glia 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstock, M. Therapeutic agents for Alzheimer's disease: a critical appraisal. Front Aging Neurosci 2024, 16, 1484615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Wang, C.; Ding, Q.; Li, P.; Sun, S.; Wei, W.; Zhang, J.; Sun, R.; Yin, L.; Liu, S.; Pu, Y. Modulation of beta secretase and neuroinflammation by biomimetic nanodelivery system for Alzheimer's disease therapy. J Control Release 2024, 378, 735–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonul, C.P.; Kiser, C.; Yaka, E.C.; Oz, D.; Hunerli, D.; Yerlikaya, D.; Olcum, M.; Keskinoglu, P.; Yener, G.; Genc, S. Microglia-like cells from patient monocytes demonstrate increased phagocytic activity in probable Alzheimer's disease. Mol Cell Neurosci 2024, 132, 103990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, L.; Gu, T.; Yu, P.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, Z. The role of microglia in Neuroinflammation associated with cardiopulmonary bypass. Front Cell Neurosci 2024, 18, 1496520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flury, A.; Aljayousi, L.; Park, H.J.; Khakpour, M.; Mechler, J.; Aziz, S.; McGrath, J.D.; Deme, P.; Sandberg, C.; Gonzalez Ibanez, F.; Braniff, O.; Ngo, T.; Smith, S.; Velez, M.; Ramirez, D.M.; Avnon-Klein, D.; Murray, J.W.; Liu, J.; Parent, M.; Mingote, S.; Haughey, N.J.; Werneburg, S.; Tremblay, M.E.; Ayata, P. A neurodegenerative cellular stress response linked to dark microglia and toxic lipid secretion. Neuron 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haessler, A.; Gier, S.; Jung, N.; Windbergs, M. The Abeta(42):Abeta(40) ratio modulates aggregation in beta-amyloid oligomers and drives metabolic changes and cellular dysfunction. Front Cell Neurosci 2024, 18, 1516093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilopoulou, F.; Piers, T.M.; Wei, J.; Hardy, J.; Pocock, J.M. Amelioration of signaling deficits underlying metabolic shortfall in TREM2(R47H) human iPSC-derived microglia. FEBS J 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bello-Corral, L.; Seco-Calvo, J.; Molina Fresno, A.; Gonzalez, A.I.; Llorente, A.; Fernandez-Lazaro, D.; Sanchez-Valdeon, L. Prevalence of ApoE Alleles in a Spanish Population of Patients with a Clinical Diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease: An Observational Case-Control Study. Medicina (Kaunas) 2024, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau-Jurado, P.; Mostafaei, S.; Xu, H.; Mo, M.; Petek, B.; Kalar, I.; Naia, L.; Kele, J.; Maioli, S.; Pereira, J.B.; Eriksdotter, M.; Chatterjee, S.; Garcia-Ptacek, S. Medications and cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease: Cohort cluster analysis of 15,428 patients. J Alzheimers Dis 2025, 13872877241307870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visscher, P.M.; Gyngell, C.; Yengo, L.; Savulescu, J. Heritable polygenic editing: the next frontier in genomic medicine? Nature 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, A.C.; Bellou, E.; Harwood, J.C.; Yaman, U.; Celikag, M.; Magusali, N.; Rambarack, N.; Botia, J.A.; Sala Frigerio, C.; Hardy, J.; Escott-Price, V.; Salih, D.A. Human longevity and Alzheimer's disease variants act via microglia and oligodendrocyte gene networks. Brain 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zhu, H.; Deng, L.; Xu, S.; Xie, W.; Li, M.; Wang, R.; Tie, L.; Zhan, L.; Yu, G. Spatial Transcriptomics: Biotechnologies, Computational Tools, and Neuroscience Applications. Small Methods 2025, e2401107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, A.N.; Jayadev, S.; Prater, K.E. Microglial Responses to Alzheimer's Disease Pathology: Insights From "Omics" Studies. Glia 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shwab, E.K.; Man, Z.; Gingerich, D.C.; Gamache, J.; Garrett, M.E.; Serrano, G.E.; Beach, T.G.; Crawford, G.E.; Ashley-Koch, A.E.; Chiba-Falek, O. Comparative mapping of single-cell transcriptomic landscapes in neurodegenerative diseases. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Lu, W.; Zhou, X.; Mu, J.; Shen, W. Unraveling Alzheimer's disease: insights from single-cell sequencing and spatial transcriptomic. Front Neurol 2024, 15, 1515981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azargoonjahromi, A.; Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging, I. Serotonin enhances neurogenesis biomarkers, hippocampal volumes, and cognitive functions in Alzheimer's disease. Mol Brain 2024, 17, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.T.; Yu, Q.; Zhou, S.D.; Yin, Y.X.; Hu, R.G.; Lu, H.P.; Hu, B.L. Co-expression Network Analysis Reveals Novel Genes Underlying Alzheimer's Disease Pathogenesis. Front Aging Neurosci 2020, 12, 605961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Liu, X.; Zuo, F.; Shi, H.; Jing, J. Artificial intelligence-based multi-omics analysis fuels cancer precision medicine. Semin Cancer Biol 2023, 88, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballard, J.L.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Shen, L.; Long, Q. Deep learning-based approaches for multi-omics data integration and analysis. BioData Min 2024, 17, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolivar, D.A.; Mosquera-Heredia, M.I.; Vidal, O.M.; Barcelo, E.; Allegri, R.; Morales, L.C.; Silvera-Redondo, C.; Arcos-Burgos, M.; Garavito-Galofre, P.; Velez, J.I. Exosomal mRNA Signatures as Predictive Biomarkers for Risk and Age of Onset in Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanez, L.; Liu, M.; Beric, A.; Timsina, J.; Kholfeld, P.; Bergmann, K.; Lowery, J.; Sykora, N.; Sanchez-Montejo, B.; Brock, W.; Budde, J.P.; Bateman, R.J.; Barthelemy, N.; Schindler, S.E.; Holtzman, D.M.; Benzinger, T.L.S.; Xiong, C.; Tarawneh, R.; Moulder, K.; Morris, J.C.; Sung, Y.J.; Cruchaga, C. Benchmarking of a multi-biomarker low-volume panel for Alzheimer's Disease and related dementia research. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastenbroek, S.E.; Sala, A.; Vallez Garcia, D.; Shekari, M.; Salvado, G.; Lorenzini, L.; Pieperhoff, L.; Wink, A.M.; Lopes Alves, I.; Wolz, R.; Ritchie, C.; Boada, M.; Visser, P.J.; Bucci, M.; Farrar, G.; Hansson, O.; Nordberg, A.K.; Ossenkoppele, R.; Barkhof, F.; Gispert, J.D.; Rodriguez-Vieitez, E.; Collij, L.E.; et al. Continuous beta-Amyloid CSF/PET Imbalance Model to Capture Alzheimer Disease Heterogeneity. Neurology 2024, 103, e209419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Xie, Q.; Xie, J.; Ni, M.; Wang, J.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Q. Cerebrospinal Fluid Proteomics Identifies Potential Biomarkers for Early-Onset Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2024, 100, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosun, D.; Hausle, Z.; Iwaki, H.; Thropp, P.; Lamoureux, J.; Lee, E.B.; MacLeod, K.; McEvoy, S.; Nalls, M.; Perrin, R.J.; Saykin, A.J.; Shaw, L.M.; Singleton, A.B.; Lebovitz, R.; Weiner, M.W.; Blauwendraat, C.; Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging, I. A cross-sectional study of alpha-synuclein seed amplification assay in Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative: Prevalence and associations with Alzheimer's disease biomarkers and cognitive function. Alzheimers Dement 2024, 20, 5114–5131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvado, G.; Horie, K.; Barthelemy, N.R.; Vogel, J.W.; Pichet Binette, A.; Chen, C.D.; Aschenbrenner, A.J.; Gordon, B.A.; Benzinger, T.L.S.; Holtzman, D.M.; Morris, J.C.; Palmqvist, S.; Stomrud, E.; Janelidze, S.; Ossenkoppele, R.; Schindler, S.E.; Bateman, R.J.; Hansson, O. Disease staging of Alzheimer's disease using a CSF-based biomarker model. Nat Aging 2024, 4, 694–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Li, Y.; Fowler, C.; Doecke, J.D.; Lim, Y.Y.; Drysdale, C.; Zhang, V.; Park, K.; Trounson, B.; Pertile, K.; Rumble, R.; Pickering, J.W.; Rissman, R.A.; Sarsoza, F.; Abdel-Latif, S.; Lin, Y.; Dore, V.; Villemagne, V.; Rowe, C.C.; Fripp, J.; Martins, R.; Wiley, J.S.; Maruff, P.; Mintzer, J.E.; Masters, C.L.; Gu, B.J. Leukocyte surface biomarkers implicate deficits of innate immunity in sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2023, 19, 2084–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, M.D.; Britton, K.J.; Joyce, H.E.; Menard, W.; Emrani, S.; Kunicki, Z.J.; Faust, M.A.; Dawson, B.C.; Riddle, M.C.; Huey, E.D.; Janelidze, S.; Hansson, O.; Salloway, S.P. Clinical application of plasma P-tau217 to assess eligibility for amyloid-lowering immunotherapy in memory clinic patients with early Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther 2024, 16, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malaguarnera, M.; Cabrera-Pastor, A. Emerging Role of Extracellular Vesicles as Biomarkers in Neurodegenerative Diseases and Their Clinical and Therapeutic Potential in Central Nervous System Pathologies. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotze, K.; Vrillon, A.; Dumurgier, J.; Indart, S.; Sanchez-Ortiz, M.; Slimi, H.; Raynaud-Simon, A.; Cognat, E.; Martinet, M.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Hourregue, C.; Bouaziz-Amar, E.; Paquet, C.; Lilamand, M. Plasma neurofilament light chain as prognostic marker of cognitive decline in neurodegenerative diseases, a clinical setting study. Alzheimers Res Ther 2024, 16, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musso, G.; Gabelli, C.; Puthenparampil, M.; Cosma, C.; Cagnin, A.; Gallo, P.; Soraru, G.; Pegoraro, E.; Zaninotto, M.; Antonini, A.; Moz, S.; Zambon, C.F.; Plebani, M.; Corbetta, M.; Basso, D. Blood biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease with the Lumipulse automated platform: Age-effect and clinical value interpretation. Clin Chim Acta 2025, 565, 120014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liampas, I.; Kyriakoulopoulou, P.; Karakoida, V.; Kavvoura, P.A.; Sgantzos, M.; Bogdanos, D.P.; Stamati, P.; Dardiotis, E.; Siokas, V. Blood-Based Biomarkers in Frontotemporal Dementia: A Narrative Review. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda, T.I.; Diaz, M.J.; Gozlan, E.C.; Chobrutskiy, A.; Chobrutskiy, B.I.; Blanck, G. Immunogenomics Parameters for Patient Stratification in Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2022, 88, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathore, S.; Higgins, I.A.; Wang, J.; Kennedy, I.A.; Iaccarino, L.; Burnham, S.C.; Pontecorvo, M.J.; Shcherbinin, S. Predicting regional tau accumulation with machine learning-based tau-PET and advanced radiomics. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2024, 10, e70005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, L.L.; Pijnenburg, Y.A.; Koedam, E.L.; van der Vlies, A.E.; Reuling, I.E.; Koene, T.; Teunissen, C.E.; Scheltens, P.; van der Flier, W.M. Early onset Alzheimer's disease is associated with a distinct neuropsychological profile. J Alzheimers Dis 2012, 30, 101–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Rodriguez, M.; Garcia-Rodriguez, C.; Villalobos, C.; Nunez, L. Role of Toll Like Receptor 4 in Alzheimer's Disease. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, G.; Luo, Y.; Jiang, L.; Chi, H.; Tian, G. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease: insights from peripheral immune cells. Immun Ageing 2024, 21, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochon, E.A.; Sy, M.; Phillips, M.; Anderson, E.; Plys, E.; Ritchie, C.; Vranceanu, A.M. Bio-Experiential Technology to Support Persons With Dementia and Care Partners at Home (TEND): Protocol for an Intervention Development Study. JMIR Res Protoc 2023, 12, e52799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murfield, J.; Moyle, W.; O'Donovan, A. Planning and designing a self-compassion intervention for family carers of people living with dementia: a person-based and co-design approach. BMC Geriatr 2022, 22, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navathe, A.S.; Volpp, K.G.; Caldarella, K.L.; Bond, A.; Troxel, A.B.; Zhu, J.; Matloubieh, S.; Lyon, Z.; Mishra Meza, A.; Sacks, L.; Nelson, C.; Patel, P.; Shea, J.; Calcagno, D.; Vittore, S.; Sokol, K.; Weng, K.; McDowald, N.; Crawford, P.; Small, D.; Emanuel, E.J. Effect of Financial Bonus Size, Loss Aversion, and Increased Social Pressure on Physician Pay-for-Performance: A Randomized Clinical Trial and Cohort Study. JAMA Netw Open 2019, 2, e187950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, J.D.; Catalano, R.F.; Miller, J.Y. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychol Bull 1992, 112, 64–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, T.G.; Croitoru, C.G.; Hodorog, D.N.; Cuciureanu, D.I. Passive Anti-Amyloid Beta Immunotherapies in Alzheimer's Disease: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Impact. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.X.; Tan, E.K.; Zhou, Z.D. Passive immunotherapy for Alzheimer's disease: challenges & future directions. J Transl Med 2024, 22, 430. [Google Scholar]

- Winblad, B.; Graf, A.; Riviere, M.E.; Andreasen, N.; Ryan, J.M. Active immunotherapy options for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther 2014, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacosta, A.M.; Pascual-Lucas, M.; Pesini, P.; Casabona, D.; Perez-Grijalba, V.; Marcos-Campos, I.; Sarasa, L.; Canudas, J.; Badi, H.; Monleon, I.; San-Jose, I.; Munuera, J.; Rodriguez-Gomez, O.; Abdelnour, C.; Lafuente, A.; Buendia, M.; Boada, M.; Tarraga, L.; Ruiz, A.; Sarasa, M. Safety, tolerability and immunogenicity of an active anti-Abeta(40) vaccine (ABvac40) in patients with Alzheimer's disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase I trial. Alzheimers Res Ther 2018, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambracht-Washington, D.; Rosenberg, R.N. Active DNA Abeta42 vaccination as immunotherapy for Alzheimer disease. Transl Neurosci 2012, 3, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, C.M.; Xue, W.W.; Liu, D.; Ma, L.; Xie, H.T.; Ning, K. Stem cell therapy in Alzheimer's disease: current status and perspectives. Front Neurosci 2024, 18, 1440334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Kong, F.; Ding, J.; Chen, C.; He, F.; Deng, W. Promoting Alzheimer's disease research and therapy with stem cell technology. Stem Cell Res Ther 2024, 15, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Rosa, A.; Olaso-Gonzalez, G.; Arc-Chagnaud, C.; Millan, F.; Salvador-Pascual, A.; Garcia-Lucerga, C.; Blasco-Lafarga, C.; Garcia-Dominguez, E.; Carretero, A.; Correas, A.G.; Vina, J.; Gomez-Cabrera, M.C. Physical exercise in the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer's disease. J Sport Health Sci 2020, 9, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallinckrodt, C.; Tian, Y.; Aisen, P.S.; Barkhof, F.; Cohen, S.; Dent, G.; Hansson, O.; Harrison, K.; Iwatsubo, T.; Mummery, C.J.; Muralidharan, K.K.; Nestorov, I.; Nisenbaum, L.; Rajagovindan, R.; von Hehn, C.; van Dyck, C.H.; Vellas, B.; Wu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Sandrock, A.; Chen, T.; Budd Haeberlein, S. Investigating Partially Discordant Results in Phase 3 Studies of Aducanumab. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2023, 10, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budd Haeberlein, S.; Aisen, P.S.; Barkhof, F.; Chalkias, S.; Chen, T.; Cohen, S.; Dent, G.; Hansson, O.; Harrison, K.; von Hehn, C.; Iwatsubo, T.; Mallinckrodt, C.; Mummery, C.J.; Muralidharan, K.K.; Nestorov, I.; Nisenbaum, L.; Rajagovindan, R.; Skordos, L.; Tian, Y.; van Dyck, C.H.; Vellas, B.; Wu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Sandrock, A. Two Randomized Phase 3 Studies of Aducanumab in Early Alzheimer's Disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2022, 9, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarawneh, R.; Pankratz, V.S. The search for clarity regarding "clinically meaningful outcomes" in Alzheimer disease clinical trials: CLARITY-AD and Beyond. Alzheimers Res Ther 2024, 16, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honig, L.S.; Sabbagh, M.N.; van Dyck, C.H.; Sperling, R.A.; Hersch, S.; Matta, A.; Giorgi, L.; Gee, M.; Kanekiyo, M.; Li, D.; Purcell, D.; Dhadda, S.; Irizarry, M.; Kramer, L. Correction: Updated safety results from phase 3 lecanemab study in early Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther 2024, 16, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honig, L.S.; Sabbagh, M.N.; van Dyck, C.H.; Sperling, R.A.; Hersch, S.; Matta, A.; Giorgi, L.; Gee, M.; Kanekiyo, M.; Li, D.; Purcell, D.; Dhadda, S.; Irizarry, M.; Kramer, L. Updated safety results from phase 3 lecanemab study in early Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther 2024, 16, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDade, E.; Cummings, J.L.; Dhadda, S.; Swanson, C.J.; Reyderman, L.; Kanekiyo, M.; Koyama, A.; Irizarry, M.; Kramer, L.D.; Bateman, R.J. Lecanemab in patients with early Alzheimer's disease: detailed results on biomarker, cognitive, and clinical effects from the randomized and open-label extension of the phase 2 proof-of-concept study. Alzheimers Res Ther 2022, 14, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampi, R.R.; Forester, B.P.; Agronin, M. Aducanumab: evidence from clinical trial data and controversies. Drugs Context 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuller, L.H.; Lopez, O.L. ENGAGE and EMERGE: Truth and consequences? Alzheimers Dement 2021, 17, 692–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, A.; Ritchie, M.D. Is the Relationship Between Cardiovascular Disease and Alzheimer's Disease Genetic? A Scoping Review. Genes (Basel) 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, C.; Nazarovs, J.; Soldan, A.; Singh, V.; Wang, J.; Hohman, T.; Dumitrescu, L.; Libby, J.; Kunkle, B.; Gross, A.L.; Johnson, S.; Lu, Q.; Engelman, C.; Masters, C.L.; Maruff, P.; Laws, S.M.; Morris, J.C.; Hassenstab, J.; Cruchaga, C.; Resnick, S.M.; Kitner-Triolo, M.H.; An, Y.; Albert, M. Alzheimer's disease genetic risk and cognitive reserve in relationship to long-term cognitive trajectories among cognitively normal individuals. Alzheimers Res Ther 2023, 15, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldner, A.C.; Turner, A.K.; Simpson, J.F.; Estus, S. Skipping of FCER1G Exon 2 Is Common in Human Brain But Not Associated with the Alzheimer's Disease Genetic Risk Factor rs2070902. J Alzheimers Dis Rep 2023, 7, 1313–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitson, H.E.; Potter, G.G.; Feld, J.A.; Plassman, B.L.; Reynolds, K.; Sloane, R.; Welsh-Bohmer, K.A. Dual-Task Gait and Alzheimer's Disease Genetic Risk in Cognitively Normal Adults: A Pilot Study. J Alzheimers Dis 2018, 64, 1137–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arai, H.; Suzuki, H.; Yoshiyama, T. Vanutide cridificar and the QS-21 adjuvant in Japanese subjects with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease: results from two phase 2 studies. Curr Alzheimer Res 2015, 12, 242–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmatalova, Z.; Skoumalova, A. [Some aspects of the immune system in the pathogenesis of Alzehimers disease]. Epidemiol Mikrobiol Imunol 2016, 65, 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.; Landreth, G.; Bickford, P. The promise and perils of an Alzheimer disease vaccine: a video debate. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2009, 4, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterner, R.M.; Takahashi, P.Y.; Yu Ballard, A.C. Active Vaccines for Alzheimer Disease Treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016, 17, 862 e11-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwan, P.; Konno, H.; Chan, K.Y.; Baum, L. Rationale for the development of an Alzheimer's disease vaccine. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2020, 16, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Blue, E.E.; Conomos, M.P.; Fohner, A.E. The power of representation: Statistical analysis of diversity in US Alzheimer's disease genetics data. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2024, 10, e12462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, N.R.; Kumar, A.; Zaman, A.; Del Rosario, P.; Mena, P.R.; Manoochehri, M.; Stein, C.; De Vito, A.N.; Sweet, R.A.; Hohman, T.J.; Cuccaro, M.L.; Beecham, G.W.; Huey, E.D.; Reitz, C. Disentangling the genetic underpinnings of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease in the Alzheimer's Disease Sequencing Project: Study design and methodology. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2024, 16, e70000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenfest-Allen, E.; Valladares, O.; Kuksa, P.P.; Gangadharan, P.; Lee, W.P.; Cifello, J.; Katanic, Z.; Kuzma, A.B.; Wheeler, N.; Bush, W.S.; Leung, Y.Y.; Schellenberg, G.; Stoeckert, C.J., Jr.; Wang, L.S. NIAGADS Alzheimer's GenomicsDB: A resource for exploring Alzheimer's disease genetic and genomic knowledge. Alzheimers Dement 2024, 20, 1123–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toga, A.W.; Phatak, M.; Pappas, I.; Thompson, S.; McHugh, C.P.; Clement, M.H.S.; Bauermeister, S.; Maruyama, T.; Gallacher, J. The pursuit of approaches to federate data to accelerate Alzheimer's disease and related dementia research: GAAIN, DPUK, and ADDI. Front Neuroinform 2023, 17, 1175689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, G.Q.; Tao, C.; Schulz, P.E.; Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging, I.; Cui, L. An ontology-based approach for harmonization and cross-cohort query of Alzheimer's disease data resources. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2023, 23 (Suppl 1), 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Therapy Type | Mechanism Description |

Clinical Application and Challenges | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Passive immunotherapy |

Injection of monoclonal antibodies to clear pathological proteins. |

Approved for early AD treatment, optimization needed for safety. |

[100] |

| Active immunotherapy (Vaccine) |

Injection of antigens or vaccines to stimulate immune response. |

Improved to reduce side effects, individual differencesand immune memory maintenance are still challenges. |

[102] |

| Cell therapy | Transplantation of immune cells or stem cells to repair neural tissue. |

In early stages, further validation of safety and efficacy is required. |

[105] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).