Submitted:

08 January 2025

Posted:

09 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

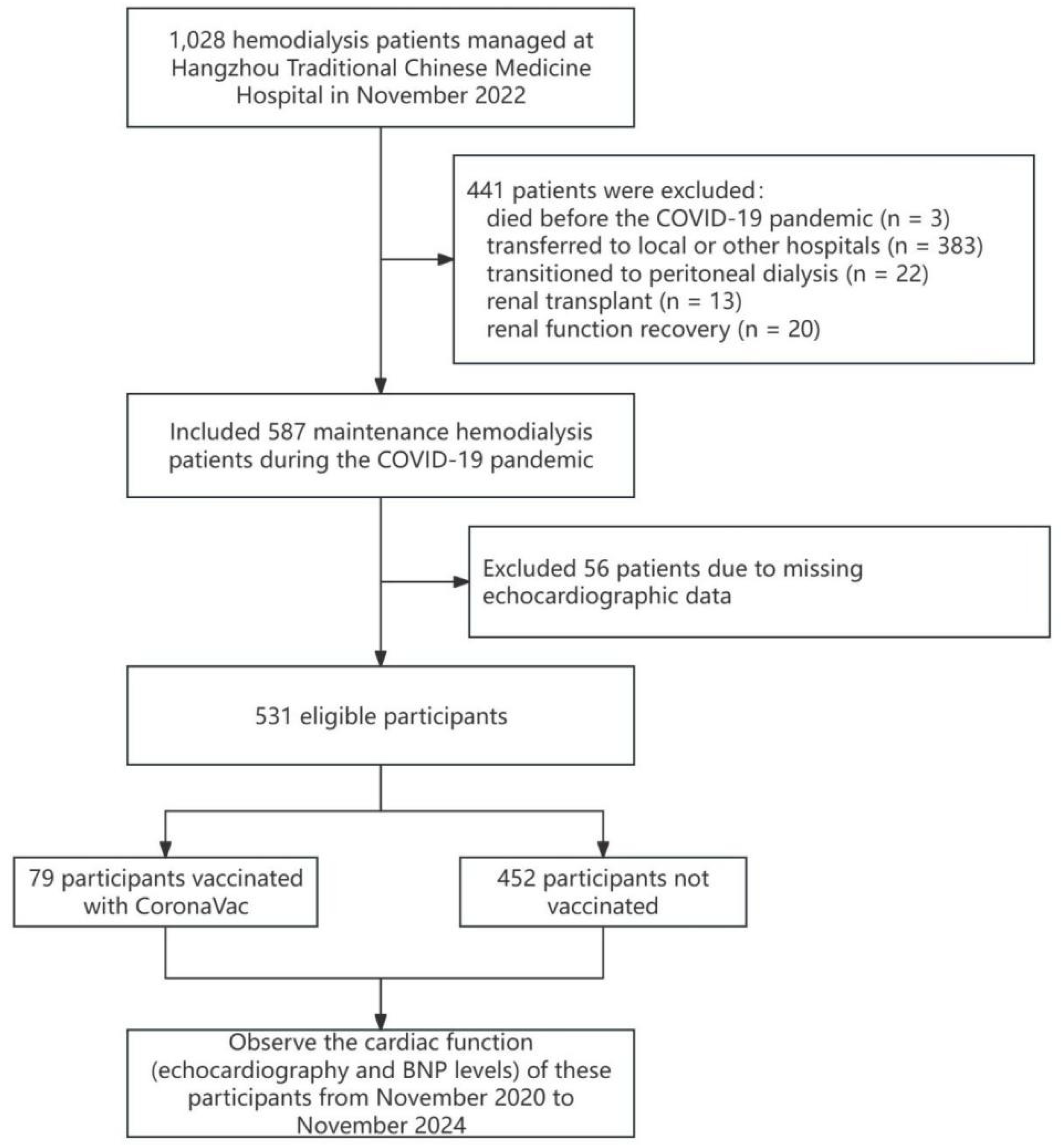

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1 Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. Clinical and Biochemical Differences Between Survival and Death Groups

3.3. Echocardiographic and BNP Characteristics of the Study Population

3.4. Multivariate Analysis of LVIDs and Related Factors

3.5. Multivariate Cox Regression Analysis Across Different Models

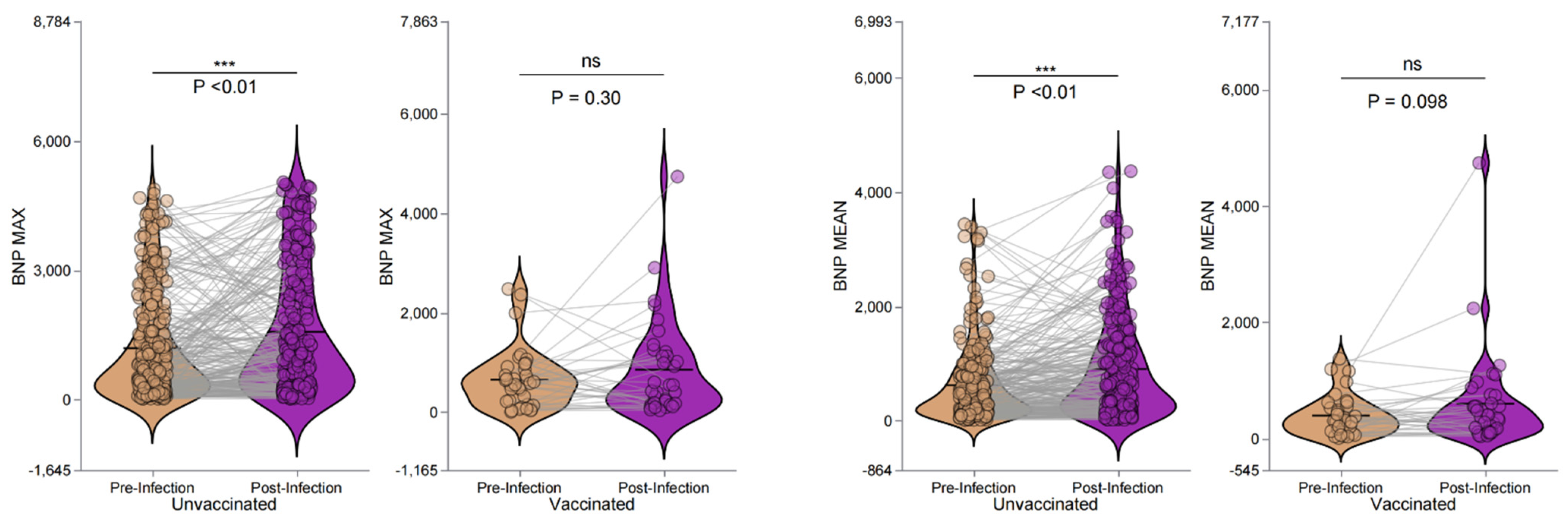

3.6. BNP Levels and the Effect of Vaccination Pre- and Post-Infection in Hemodialysis Patients

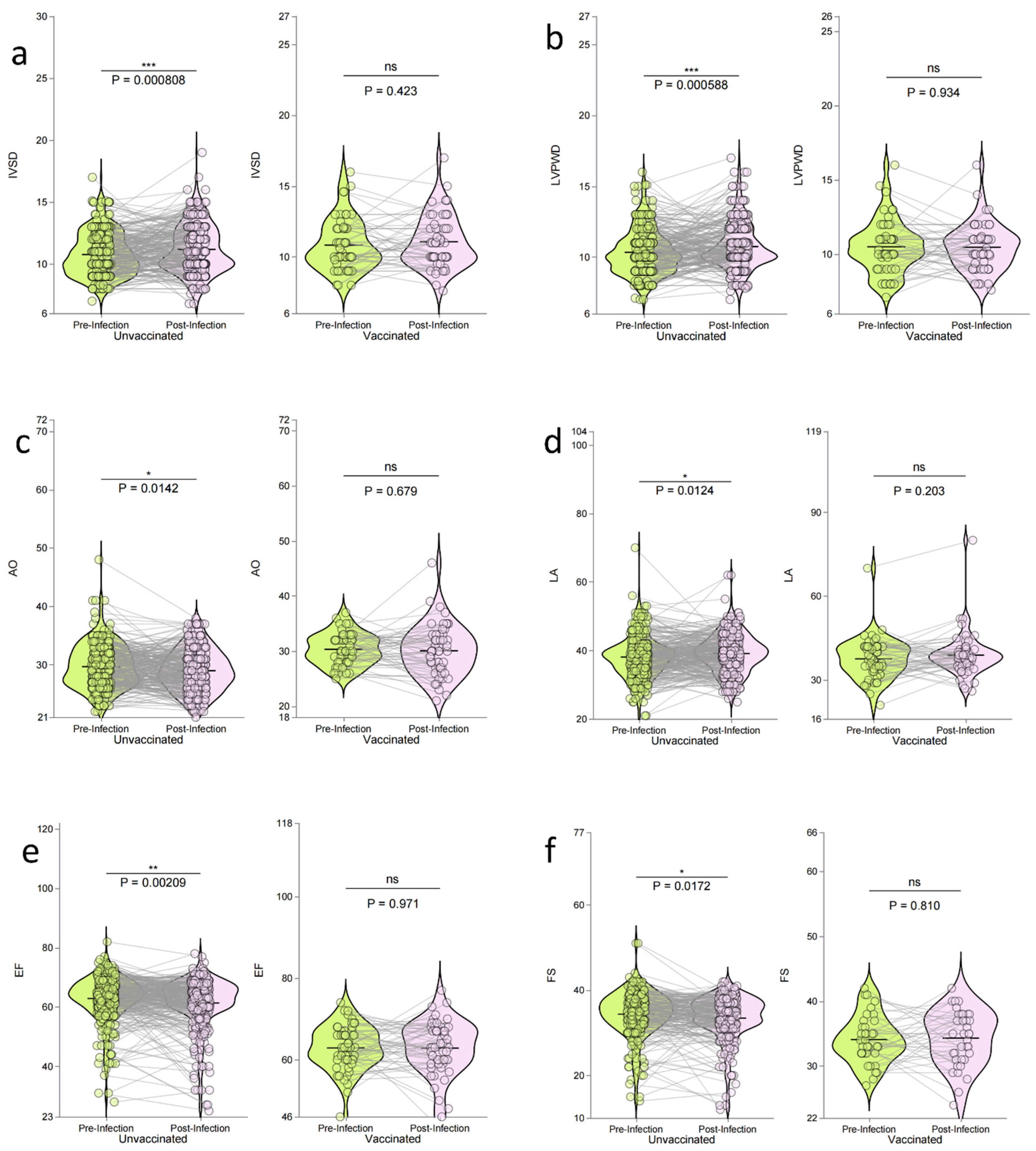

3.7. Impact of Vaccination on Echocardiographic Parameters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grujic N, Pešić S, Naumovic R: MO851 INCIDENCE AND MORTALITY OF CORONAVIRUS DISEASE (COVID 19) IN HEMODIALYSIS PATIENTS. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2021, 36(Supplement_1):gfab098. 0043.

- Haarhaus M, Santos C, Haase M, Mota Veiga P, Lucas C, Macario F: Risk prediction of COVID-19 incidence and mortality in a large multi-national hemodialysis cohort: implications for management of the pandemic in outpatient hemodialysis settings. Clinical Kidney Journal 2021, 14(3):805-813.

- Goicoechea M, Cámara LAS, Macías N, de Morales AM, Rojas ÁG, Bascuñana A, Arroyo D, Vega A, Abad S, Verde E: COVID-19: clinical course and outcomes of 36 hemodialysis patients in Spain. Kidney international 2020, 98(1):27-34.

- Vergara A, Molina-Van den Bosch M, Toapanta N, Villegas A, Sánchez-Cámara L, Sequera Pd, Manrique J, Shabaka A, Aragoncillo I, Ruiz MC: The impact of age on mortality in chronic haemodialysis population with COVID-19. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2021, 10(14):3022.

- Tylicki L, Puchalska-Reglińska E, Tylicki P, Och A, Polewska K, Biedunkiewicz B, Parczewska A, Szabat K, Wolf J, Dębska-Ślizień A: Predictors of mortality in hemodialyzed patients after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11(2):285.

- !!! INVALID CITATION !!! [5,6].

- Ashby DR, Caplin B, Corbett RW, Asgari E, Kumar N, Sarnowski A, Hull R, Makanjuola D, Cole N, Chen J: Severity of COVID-19 after vaccination among hemodialysis patients: an observational cohort study. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2022, 17(6):843-850.

- Wu C, Xie G, Chen J, Liu Q, Wang H, Tang Y: # 5019 MORTALITY FOR COVID-19 IN UNDERGOING MAINTENANCE DIALYSIS PATIENTS: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW AND META-ANALYSIS. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2023, 38(Supplement_1):gfad063c_5019.

- Cozzolino M, Mangano M, Stucchi A, Ciceri P, Conte F, Galassi A: Cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2018, 33(suppl_3):iii28-iii34.

- !!! INVALID CITATION !!! [10].

- Sarnak MJ, Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC, Coresh J, Culleton B, Hamm LL, McCullough PA, Kasiske BL, Kelepouris E, Klag MJ: Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: a statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, High Blood Pressure Research, Clinical Cardiology, and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation 2003, 108(17):2154-2169.

- Wang A, Montgomery D, Brinster DR, Gilon D, Upchurch Jr GR, Gleason TG, Estrera A, Isselbacher EM, Eagle KA, Hughes GC: Predicting in-hospital survival in acute type A aortic dissection medically treated. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2020, 75(11):1360-1361.

- Puntmann VO, Carerj ML, Wieters I, Fahim M, Arendt C, Hoffmann J, Shchendrygina A, Escher F, Vasa-Nicotera M, Zeiher AM: Outcomes of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in patients recently recovered from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA cardiology 2020, 5(11):1265-1273.

- Driggin E, Madhavan MV, Bikdeli B, Chuich T, Laracy J, Biondi-Zoccai G, Brown TS, Der Nigoghossian C, Zidar DA, Haythe J: Cardiovascular considerations for patients, health care workers, and health systems during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American College of cardiology 2020, 75(18):2352-2371.

- Gao P, Liu J, Liu M: Effect of COVID-19 vaccines on reducing the risk of long COVID in the real world: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19(19):12422.

- Feltes G, Romero R, Uribarri Gonzalez A, Nuñez Gil IJ, Raposeiras-Roubin S, Viana-Llamas MC, Alfonso E: Post-COVID-19 Symptoms and Heart Disease: Incidence, Prognostic Factors, Outcomes and Vaccination: Results from a Multi-Center International Prospective Registry (HOPE 2). 2023.

- Zisis SN, Durieux JC, Mouchati C, Perez JA, McComsey GA: The protective effect of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination on postacute sequelae of COVID-19: a multicenter study from a large national health research network. In: Open Forum Infectious Diseases: 2022: Oxford University Press; 2022: ofac228.

- Akin D, Ozmen S, Caliskan A, Sari T: Efficacy and safety of Sinovac vaccine administered in patients undergoing hemodialysis. The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries 2022, 16(12):1821-1825.

- Medina-Pestana J, Teixeira CM, Viana LA, Manfredi SR, Nakamura MR, Lucena EF, Amiratti AL, Tedesco-Silva H, Covas DT, Cristelli MP: Immunogenicity, reactogenicity and breakthrough infections after two doses of the inactivated CoronaVac vaccine among patients on dialysis: phase 4 study. Clinical Kidney Journal 2022, 15(4):816-817.

- Ran E, Wang M, Wang Y, Liu R, Yi Y, Liu Y: New-onset crescent IgA nephropathy following the CoronaVac vaccine: A case report. Medicine 2022, 101(33):e30066.

- Ihara H, Kikuchi K, Taniguchi H, Fujita S, Tsuruta Y, Kato M, Mitsuishi Y, Tajima K, Kodama Y, Takahashi F: 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine improves survival in dialysis patients by preventing cardiac events. Vaccine 2019, 37(43):6447-6453. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Q, Lu C, Chen H, Li M, Bai X, Chen J, Li D, Zhang Y, Lei N, He W: Effectiveness of vaccination in reducing hospitalization and mortality rates in dialysis patients with Omicron infection in China: A single-center study. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2023, 19(2):2252257.

- Rincon-Arevalo H, Choi M, Stefanski A-L, Halleck F, Weber U, Szelinski F, Jahrsdörfer B, Schrezenmeier H, Ludwig C, Sattler A: Impaired humoral immunity to SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients and dialysis patients. Science immunology 2021, 6(61):eabj1031.

- Parker EP, Tazare J, Hulme WJ, Bates C, Carr EJ, Cockburn J, Curtis HJ, Fisher L, Green AC, Harper S et al.: Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine uptake in people with kidney disease: an OpenSAFELY cohort study. BMJ Open 2023, 13(1):e066164. [CrossRef]

- Manley HJ, Li NC, Aweh GN, Hsu CM, Weiner DE, Miskulin D, Harford AM, Johnson D, Lacson E, Jr.: SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Effectiveness and Breakthrough Infections Among Patients Receiving Maintenance Dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2023, 81(4):406-415.

- Speer C, Göth D, Benning L, Buylaert M, Schaier M, Grenz J, Nusshag C, Kälble F, Kreysing M, Reichel P et al.: Early Humoral Responses of Hemodialysis Patients after COVID-19 Vaccination with BNT162b2. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2021, 16(7):1073-1082. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi AR, Alvestrand A, Divino-Filho JC, Gutierrez A, Heimbürger O, Lindholm B, Bergström J: Inflammation, malnutrition, and cardiac disease as predictors of mortality in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002, 13 Suppl 1:S28-36. [CrossRef]

- Selim G, Stojceva-Taneva O, Zafirovska K, Sikole A, Gelev S, Dzekova P, Stefanovski K, Koloska V, Polenakovic M: Inflammation predicts all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in haemodialysis patients. Prilozi 2006, 27(1):133-144.

- Jagadeswaran D, Indhumathi E, Hemamalini AJ, Sivakumar V, Soundararajan P, Jayakumar M: Inflammation and nutritional status assessment by malnutrition inflammation score and its outcome in pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease patients. Clin Nutr 2019, 38(1):341-347.

- de Mutsert R, Grootendorst DC, Axelsson J, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT, Dekker FW: Excess mortality due to interaction between protein-energy wasting, inflammation and cardiovascular disease in chronic dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008, 23(9):2957-2964.

- Wang AY, Wang M, Woo J, Lam CW, Lui SF, Li PK, Sanderson JE: Inflammation, residual kidney function, and cardiac hypertrophy are interrelated and combine adversely to enhance mortality and cardiovascular death risk of peritoneal dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004, 15(8):2186-2194. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Reyes MJ, Alvarez-Ude F, Sánchez R, Mon C, Iglesias P, Díez JJ, Vázquez A: Inflammation and malnutrition as predictors of mortality in patients on hemodialysis. J Nephrol 2002, 15(2):136-143.

- Choi HY, Lee JE, Han SH, Yoo TH, Kim BS, Park HC, Kang SW, Choi KH, Ha SK, Lee HY et al.: Association of inflammation and protein-energy wasting with endothelial dysfunction in peritoneal dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010, 25(4):1266-1271. [CrossRef]

- Brandão da Cunha Bandeira S, Cansanção K, Pereira de Paula T, Peres WAF: Evaluation of the prognostic significance of the malnutrition inflammation score in hemodialysis patients. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2020, 35:109-115.

- Liu Y, Coresh J, Eustace JA, Longenecker JC, Jaar B, Fink NE, Tracy RP, Powe NR, Klag MJ: Association between cholesterol level and mortality in dialysis patients: role of inflammation and malnutrition. Jama 2004, 291(4):451-459.

- Stenvinkel P, Alvestrand A: Inflammation in end-stage renal disease: sources, consequences, and therapy. Semin Dial 2002, 15(5):329-337.

- Palazzuoli A, Gallotta M, Quatrini I, Nuti R: Natriuretic peptides (BNP and NT-proBNP): measurement and relevance in heart failure. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2010, 6:411-418.

- Zoccali C, Mallamaci F, Benedetto FA, Tripepi G, Parlongo S, Cataliotti A, Cutrupi S, Giacone G, Bellanuova I, Cottini E et al.: Cardiac natriuretic peptides are related to left ventricular mass and function and predict mortality in dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001, 12(7):1508-1515. [CrossRef]

- Harrison TG, Shukalek CB, Hemmelgarn BR, Zarnke KB, Ronksley PE, Iragorri N, Graham MM, James MT: Association of NT-proBNP and BNP With Future Clinical Outcomes in Patients With ESKD: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2020, 76(2):233-247.

- Yuan L, Chen C, Feng Y, Yang XJ, Li Y, Wu Y, Hu F, Zhang M, Li X, Hu H et al.: High-sensitivity cardiac troponin, a cardiac marker predicting death in patients with kidney disease: a dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Qjm 2023, 116(5):335-343.

- Zuo ML, Chen QY, Pu L, Shi L, Wu D, Li H, Luo X, Yin LX, Siu CW, Hong DQ et al.: Impact of Hemodialysis on Left Ventricular-Arterial Coupling in End-Stage Renal Disease Patients. Blood Purif 2023, 52(7-8):702-711. [CrossRef]

- McCullough PA, Chan CT, Weinhandl ED, Burkart JM, Bakris GL: Intensive Hemodialysis, Left Ventricular Hypertrophy, and Cardiovascular Disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2016, 68(5s1):S5-s14.

- Flythe JE, Chang TI, Gallagher MP, Lindley E, Madero M, Sarafidis PA, Unruh ML, Wang AY, Weiner DE, Cheung M et al.: Blood pressure and volume management in dialysis: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int 2020, 97(5):861-876. [CrossRef]

- Law MC, Kwan BC, Fung JS, Chow KM, Ng JKC, Pang WF, Cheng PM, Leung CB, Szeto CC: The efficacy of managing fluid overload in chronic peritoneal dialysis patients by a structured nurse-led intervention protocol. BMC Nephrol 2019, 20(1):454.

- Sturm G, Lamina C, Zitt E, Lhotta K, Lins F, Freistätter O, Neyer U, Kronenberg F: Sex-specific association of time-varying haemoglobin values with mortality in incident dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010, 25(8):2715-2722.

- Zoccali C, Benedetto FA, Mallamaci F, Tripepi G, Giacone G, Stancanelli B, Cataliotti A, Malatino LS: Left ventricular mass monitoring in the follow-up of dialysis patients: prognostic value of left ventricular hypertrophy progression. Kidney Int 2004, 65(4):1492-1498.

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X et al.: Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395(10223):497-506.

- Naga YS, El Keraie A, Abd ElHafeez SS, Zyada RS: Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on care of maintenance hemodialysis patients: a multicenter study. Clin Exp Nephrol 2024, 28(10):1040-1050.

- Natale P, Zhang J, Scholes-Robertson N, Cazzolli R, White D, Wong G, Guha C, Craig J, Strippoli G, Stallone G et al.: The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Patients With CKD: Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Am J Kidney Dis 2023, 82(4):395-409.e391. [CrossRef]

- Tobler DL, Pruzansky AJ, Naderi S, Ambrosy AP, Slade JJ: Long-Term Cardiovascular Effects of COVID-19: Emerging Data Relevant to the Cardiovascular Clinician. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2022, 24(7):563-570.

- Watanabe A, Iwagami M, Yasuhara J, Takagi H, Kuno T: Protective effect of COVID-19 vaccination against long COVID syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 2023, 41(11):1783-1790.

- Mercadé-Besora N, Li X, Kolde R, Trinh NT, Sanchez-Santos MT, Man WY, Roel E, Reyes C, Delmestri A, Nordeng HME et al.: The role of COVID-19 vaccines in preventing post-COVID-19 thromboembolic and cardiovascular complications. Heart 2024, 110(9):635-643. [CrossRef]

- Boros LG, Kyriakopoulos AM, Brogna C, Piscopo M, McCullough PA, Seneff S: Long-lasting, biochemically modified mRNA, and its frameshifted recombinant spike proteins in human tissues and circulation after COVID-19 vaccination. Pharmacol Res Perspect 2024, 12(3):e1218.

| Variable | Total (n = 531) |

Unvaccinated (n = 452) |

Vaccinated (n = 79) | t/χ2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64.51 ± 13.81 | 65.21 ± 13.76 | 60.54 ± 13.51 | t = 2.79 | 0.006 ** |

| Dialysis Duration (months) | 71.10 ± 63.30 | 73.73 ± 64.79 | 56.04 ± 51.88 | t = 2.30 | 0.022 * |

| Gender, n (%) | χ2 = 1.18 | 0.277 | |||

| Male | 334 (62.90) | 280 (61.95) | 54 (68.35) | ||

| Female | 197 (37.10) | 172 (38.05) | 25 (31.65) | ||

| Primary Disease, n (%) | 0.243 | ||||

| PKD | 26 (4.90) | 20 (4.42) | 6 (7.59) | ||

| CTD | 9 (1.69) | 8 (1.77) | 1 (1.27) | ||

| CGN | 289 (54.43) | 240 (53.10) | 49 (62.03) | ||

| DN | 199 (37.48) | 177 (39.16) | 22 (27.85) | ||

| Others | 8 (1.51) | 7 (1.55) | 1 (1.27) | ||

| Death, n (%) | χ2 = 3.98 | 0.049 * | |||

| 0 | 461 (86.82) | 387 (85.62) | 74 (93.67) | ||

| 1 | 70 (13.18) | 65 (14.38) | 5 (6.33) | ||

| HTN, n (%)* | χ2 = 0.01 | 0.918 | |||

| 0 | 72 (13.56) | 61 (13.50) | 11 (13.92) | ||

| 1 | 459 (86.44) | 391 (86.50) | 68 (86.08) | ||

| Arrhythmia, n (%) | χ2 = 3.33 | 0.068 | |||

| 0 | 491 (92.47) | 414 (91.59) | 77 (97.47) | ||

| 1 | 40 (7.53) | 38 (8.41) | 2 (2.53) | ||

| CAD, n (%) | χ2 = 12.37 | <0.001** | |||

| 0 | 392 (73.82) | 321 (71.02) | 71 (89.87) | ||

| 1 | 139 (26.18) | 131 (28.98) | 8 (10.13) | ||

| HF, n (%) | χ2 = 1.48 | 0.224 | |||

| 0 | 507 (95.48) | 429 (94.91) | 78 (98.73) | ||

| 1 | 24 (4.52) | 23 (5.09) | 1 (1.27) | ||

| COVID-19 Hospitalization, n (%) | χ2 = 0.02 | 0.898 | |||

| 0 | 452 (85.28) | 385 (85.37) | 67 (84.81) | ||

| 1 | 78 (14.72) | 66 (14.63) | 12 (15.19) | ||

| Severe COVID-19, n (%) | χ2 = 0.20 | 0.658 | |||

| 0 | 512 (96.42) | 437 (96.68) | 75 (94.94) | ||

| 1 | 19 (3.58) | 15 (3.32) | 4 (5.06) |

| Variables, Units | Total (n = 531) |

Survival (n = 461) |

Death (n = 70) | t/Z | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 64.51 ± 13.81 | 62.82 ± 13.24 | 75.67 ± 12.27 | t = -7.64 | <0.001** |

| Dialysis Duration, months | 48.00 (26.00, 96.50) | 49.00 (27.00, 97.00) | 45.38 (18.66, 94.21) | Z = -1.05 | 0.292 |

| URR, % | 68.55 ± 30.37 | 68.57 ± 32.12 | 68.37 ± 8.49 | t = 0.04 | 0.97 |

| ALB, g/dL | 35.62 ± 4.00 | 35.96 ± 3.88 | 33.60 ± 4.15 | t = 4.42 | <0.001** |

| ALT, U/L | 14.07 ± 8.47 | 14.11 ± 8.18 | 13.81 ± 10.06 | t = 0.26 | 0.794 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 2.19 ± 0.82 | 2.21 ± 0.84 | 2.06 ± 0.68 | t = 1.35 | 0.178 |

| Ca, mg/dL | 2.22 ± 0.20 | 2.22 ± 0.20 | 2.20 ± 0.17 | t = 0.86 | 0.389 |

| TG, mg/dL | 1.84 ± 1.48 | 1.86 ± 1.53 | 1.71 ± 1.11 | t = 0.73 | 0.468 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 0.97 ± 0.24 | 0.97 ± 0.24 | 0.92 ± 0.25 | t = 1.64 | 0.102 |

| Cr, µmol/L | 750.93 ± 275.31 | 774.00 ± 276.61 | 612.10 ± 223.19 | t = 5.14 | <0.001** |

| PTH, pg/mL | 226.10 (117.12, 437.43) | 224.40 (117.85, 418.15) | 273.90 (108.10, 504.00) | Z = -0.65 | 0.514 |

| K, mEq/L | 4.66 ± 0.66 | 4.68 ± 0.66 | 4.56 ± 0.65 | t = 1.40 | 0.162 |

| PHOS, mg/dL | 1.61 ± 0.46 | 1.64 ± 0.46 | 1.42 ± 0.46 | t = 3.66 | <0.001** |

| Na, mEq/L | 138.03 ± 3.16 | 138.12 ± 3.18 | 137.43 ± 2.96 | t = 1.70 | 0.090* |

| Urea, µmol/L | 21.80 ± 6.52 | 22.20 ± 6.25 | 19.40 ± 7.56 | t = 3.19 | 0.002** |

| PT, seconds | 11.30 ± 2.02 | 11.20 ± 2.06 | 11.89 ± 1.68 | t = -2.42 | 0.016* |

| PA, mg/dL | 313.06 ± 80.97 | 318.20 ± 78.71 | 275.05 ± 88.09 | t = 3.25 | 0.001** |

| AST, U/L | 18.86 ± 8.75 | 18.27 ± 7.79 | 22.24 ± 12.50 | t = -2.44 | 0.017* |

| Hb, g/dL | 109.90 ± 13.72 | 110.68 ± 13.38 | 104.77 ± 14.89 | t = 3.37 | <0.001** |

| UA, µmol/L | 401.74 ± 102.71 | 410.32 ± 98.65 | 350.48 ± 112.04 | t = 4.37 | <0.001** |

| TCH, mg/dL | 3.89 ± 1.11 | 3.93 ± 1.13 | 3.63 ± 0.95 | t = 1.96 | 0.051 |

| Hs-CRP, mg/L | 2.44 (1.11, 7.32) | 2.03 (0.97, 6.20) | 7.26 (3.17, 24.80) | Z = -6.30 | <0.001** |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 80.75 (39.30, 160.82) | 74.30 (39.30, 157.10) | 120.70 (47.10, 221.90) | Z = -1.88 | 0.06 |

| Variables, Units | Total (n = 531) | Survival (n = 461) | Death (n = 70) | Z/χ2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNP Max, pg/mL | 462.50 (98.75, 1216.50) | 401.50 (86.75, 999.75) | 1246.00 (387.75, 2456.50) | Z = -4.77 | <0.001** |

| BNP Mean, pg/mL | 283.00 (84.75, 679.75) | 247.00 (70.75, 612.25) | 584.50 (181.50, 992.00) | Z = -3.52 | <0.001** |

| IVSD, mm | 10.20 (9.00, 12.00) | 10.00 (9.00, 12.00) | 11.00 (10.00, 12.00) | Z = -1.39 | 0.165 |

| LVIDd, mm | 49.00 (46.00, 53.00) | 49.00 (46.00, 53.00) | 49.00 (46.02, 53.00) | Z = -0.08 | 0.938 |

| LVIDs, mm | 32.00 (30.00, 35.00) | 32.00 (30.00, 35.00) | 33.00 (30.00, 36.40) | Z = -0.99 | 0.321 |

| LVPWD, mm | 10.00 (9.00, 11.00) | 10.00 (9.00, 11.00) | 10.00 (9.57, 11.65) | Z = -1.53 | 0.127 |

| AO, mm | 29.00 (27.00, 32.00) | 29.00 (27.00, 32.00) | 29.00 (27.00, 32.00) | Z = -0.36 | 0.718 |

| LA, mm | 38.00 (34.00, 41.00) | 38.00 (34.00, 41.00) | 39.00 (34.25, 42.00) | Z = -1.14 | 0.254 |

| SV, mL | 72.00 (63.50, 85.00) | 72.00 (63.00, 85.00) | 73.00 (65.00, 81.00) | Z = -0.12 | 0.906 |

| EF, % | 64.00 (60.00, 68.00) | 64.00 (60.00, 68.00) | 64.00 (58.00, 66.75) | Z = -1.46 | 0.144 |

| FS, % | 35.00 (32.00, 38.00) | 35.00 (32.00, 38.00) | 35.00 (31.25, 37.00) | Z = -1.04 | 0.299 |

| Arrhythmia | χ2 = 3.28 | 0.07 | |||

| Normal | 491 (92.47) | 430 (93.28) | 61 (87.14) | ||

| Abnormal | 40 (7.53) | 31 (6.72) | 9 (12.86) | ||

| Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) | χ2 = 70.02 | <0.001** | |||

| Normal | 392 (73.82) | 369 (80.04) | 23 (32.86) | ||

| Abnormal | 139 (26.18) | 92 (19.96) | 47 (67.14) | ||

| Heart Failure | χ2 = 7.17 | 0.007** | |||

| Normal | 507 (95.48) | 445 (96.53) | 62 (88.57) | ||

| Abnormal | 24 (4.52) | 16 (3.47) | 8 (11.43) | ||

| IVSD Status | χ2 = 1.07 | 0.301 | |||

| Normal | 212 (39.92) | 188 (40.78) | 24 (34.29) | ||

| Abnormal | 319 (60.08) | 273 (59.22) | 46 (65.71) | ||

| LVIDd Status | χ2 = 1.50 | 0.221 | |||

| Normal | 464 (87.38) | 406 (88.07) | 58 (82.86) | ||

| Abnormal | 67 (12.62) | 55 (11.93) | 12 (17.14) | ||

| LVIDs Status | χ2 = 3.86 | 0.049* | |||

| Normal | 228 (90.48) | 200 (92.17) | 28 (80.00) | ||

| Abnormal | 24 (9.52) | 17 (7.83) | 7 (20.00) | ||

| LVPWDStatus | χ2 = 1.71 | 0.191 | |||

| Normal | 251 (47.27) | 223 (48.37) | 28 (40.00) | ||

| Abnormal | 280 (52.73) | 238 (51.63) | 42 (60.00) | ||

| AO Status | χ2 = 0.00 | 1 | |||

| Normal | 517 (97.36) | 449 (97.40) | 68 (97.14) | ||

| Abnormal | 14 (2.64) | 12 (2.60) | 2 (2.86) | ||

| LA Status | χ2 = 0.67 | 0.412 | |||

| Normal | 385 (72.64) | 337 (73.26) | 48 (68.57) | ||

| Abnormal | 145 (27.36) | 123 (26.74) | 22 (31.43) | ||

| SV Status | χ2 = 0.04 | 0.846 | |||

| Normal | 355 (90.79) | 306 (90.53) | 49 (92.45) | ||

| Abnormal | 36 (9.21) | 32 (9.47) | 4 (7.55) | ||

| EF Status | χ2 = 1.18 | 0.278 | |||

| Normal | 486 (91.87) | 424 (92.37) | 62 (88.57) | ||

| Abnormal | 43 (8.13) | 35 (7.63) | 8 (11.43) | ||

| FS Status | χ2 = 0.30 | 0.586 | |||

| Normal | 381 (93.38) | 332 (93.79) | 49 (90.74) | ||

| Abnormal | 27 (6.62) | 22 (6.21) | 5 (9.26) |

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | β | S.E | Z | P-value | HR (95% CI) | Variables | β | S.E | Z | P-value |

| Age | 0.07 | 0.01 | 7.23 | <0.001** | 1.08 (1.06–1.10) | 0.1 | 0.04 | 2.6 | 0.009** | 1.10 (1.02–1.18) |

| ALB | -0.11 | 0.02 | -4.48 | <0.001** | 0.90 (0.85–0.94) | 0.13 | 0.12 | 1.05 | 0.294 | 1.14 (0.89–1.45) |

| Cr | -0.01 | 0 | -4.3 | <0.001** | 0.99 (0.99–0.99) | 0 | 0 | 0.12 | 0.906 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) |

| PHOS | -1.16 | 0.3 | -3.86 | <0.001** | 0.31 (0.17–0.57) | -0.56 | 0.93 | -0.6 | 0.547 | 0.57 (0.09–3.54) |

| Urea | -0.07 | 0.02 | -3.34 | <0.001** | 0.93 (0.89–0.97) | -0.09 | 0.07 | -1.3 | 0.195 | 0.91 (0.79–1.05) |

| PT | 0.06 | 0.03 | 2.2 | 0.028* | 1.07 (1.01–1.13) | -0.03 | 0.17 | -0.16 | 0.869 | 0.97 (0.69–1.37) |

| PA | -0.01 | 0 | -3.29 | <0.001** | 0.99 (0.99–0.99) | 0 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.989 | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) |

| AST | 0.04 | 0.01 | 3.54 | <0.001** | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.43 | 0.154 | 1.03 (0.99–1.08) |

| Hb | -0.03 | 0.01 | -3.5 | <0.001** | 0.97 (0.96–0.99) | -0.04 | 0.03 | -1.34 | 0.18 | 0.96 (0.90–1.02) |

| UA | -0.01 | 0 | -4.52 | <0.001** | 0.99 (0.99–0.99) | 0 | 0 | 0.55 | 0.584 | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) |

| Hs-CRP | 0.01 | 0 | 4.84 | <0.001** | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | 0.03 | 0.01 | 1.97 | 0.049* | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) |

| BNP Max | 0.01 | 0 | 4.93 | <0.001** | 1.01 (1.01–1.01) | 0 | 0 | -0.19 | 0.847 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) |

| BNPMean | 0.01 | 0 | 2.1 | 0.036* | 1.01 (1.01–1.01) | 0 | 0 | -0.66 | 0.506 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) |

| HTN | -0.81 | 0.28 | -2.92 | 0.004** | 0.44 (0.26–0.77) | -0.63 | 0.73 | -0.86 | 0.388 | 0.53 (0.13–2.23) |

| CAD | 1.93 | 0.25 | 7.57 | <0.001** | 6.88 (4.18–11.34) | 1.44 | 0.7 | 2.04 | 0.041* | 4.20 (1.06–16.71) |

| HF | 1.17 | 0.38 | 3.12 | 0.002** | 3.22 (1.54–6.74) | -0.18 | 1.37 | -0.13 | 0.896 | 0.84 (0.06–12.34) |

| Variables | Model 1 HR (95% CI), p | Model 2 HR (95% CI), p | Model 3 HR (95% CI), p |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVIDd | 1.46 (0.78–2.71), 0.235 | 1.03 (0.28–3.76), 0.959 | 2.85 (0.18–45.72), 0.460 |

| LVPWD | 1.36 (0.84–2.19), 0.207 | 1.19 (0.25–5.68), 0.824 | 1.58 (0.05–48.08), 0.793 |

| AO | 1.06 (0.26–4.33), 0.934 | 0.00 (0.00–Inf), 0.997 | 0.00 (0.00–Inf), 0.999 |

| LA | 1.25 (0.75–2.06), 0.394 | 1.17 (0.29–4.65), 0.828 | 0.12 (0.01–1.96), 0.135 |

| IVSD | 1.28 (0.78–2.10), 0.326 | 5.94 (1.04–33.77), 0.045* | 49.88 (0.85–2938.25), 0.060* |

| SV | 0.81 (0.29–2.23), 0.679 | 1.12 (0.25–5.14), 0.879 | 0.41 (0.02–10.64), 0.593 |

| EF | 1.49 (0.71–3.11), 0.289 | 0.10 (0.01–1.14), 0.064 | 0.00 (0.00–74.96), 0.259 |

| FS | 1.49 (0.59–3.73), 0.398 | 0.57 (0.05–6.22), 0.649 | 97.62 (0.02–562248.02), 0.300 |

| LVIDs | 2.66 (1.16–6.10), 0.021* | 28.88 (3.47–240.13), 0.002** | 1574.03 (3.30–750000.88), 0.019* |

| Gender (Female) | 1.00 (0.61–1.62), 0.988 | 0.15 (0.03–0.66), 0.013* | 0.01 (0.00–0.34), 0.011* |

| LVIDd (Abnormals) | 0.99 (0.96–1.03), 0.779 | 0.86 (0.74–0.99), 0.046* | 0.78 (0.57–1.08), 0.139 |

| LVIDs (Abnormal) | 1.02 (0.97–1.08), 0.434 | 0.87 (0.75–1.01), 0.074 | 0.72 (0.51–0.99), 0.050 |

| SV (Abnormal) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01), 0.914 | 1.04 (1.01–1.07), 0.037* | 1.08 (1.01–1.16), 0.023* |

| EF (Abnormal) | 0.98 (0.95–1.00), 0.089 | 0.87 (0.76–0.98), 0.027* | 0.71 (0.52–0.96), 0.025* |

| AO (Abnormal) | 1.00 (0.94–1.07), 0.888 | 0.93 (0.81–1.06), 0.288 | 0.65 (0.45–0.95), 0.027* |

| Group | Pre-Infection (n=283) | Post-Infection (n=283) | z | p-value | z-value | z p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNP Max, pg/mL | ||||||

| Unvaccinated | 652.00 (234.00, 1765.50) | 1059.00 (312.00, 2486.50) | 10629.5 | <0.001** | -1.76 | 0.078 |

| Vaccinated | 573.50 (205.50, 882.50) | 489.50 (161.25, 1152.75) | 266 | 0.3 | -2.78 | 0.006** |

| BNP Mean, pg/mL | ||||||

| Unvaccinated | 398.00 (158.50, 833.00) | 619.00 (226.50, 1291.50) | 8658 | < 0.001** | -1.56 | 0.119 |

| Vaccinated | 311.00 (121.50, 535.25) | 389.50 (155.75, 640.50) | 227 | 0.098 | -2.33 | 0.02* |

| Group | Pre-Infection (n=348) | Post-Infection (n=348) | t-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVSD, mm | Unvaccinated | 10.76 ± 1.73 | 11.18 ± 1.95 | -3.39 | <0.001** |

| Vaccinated | 10.84 ± 1.81 | 11.07 ± 1.86 | -0.81 | 0.423 | |

| LVIDd, mm | Unvaccinated | 49.48 ± 5.65 | 49.79 ± 5.33 | -0.82 | 0.411 |

| Vaccinated | 49.71 ± 5.64 | 49.59 ± 5.35 | 0.13 | 0.897 | |

| LVIDS, mm | Unvaccinated | 33.52 ± 6.01 | 33.61 ± 5.81 | 0.15 | 0.883 |

| Vaccinated | 32.80 ± 3.36 | 32.23 ± 4.30 | 1.3 | 0.206 | |

| LVPWD, mm | Unvaccinated | 10.34 ± 1.58 | 10.96 ± 3.12 | -3.2 | 0.001** |

| Vaccinated | 10.50 ± 1.78 | 10.48 ± 1.57 | 0.08 | 0.934 | |

| AO, mm | Unvaccinated | 29.68 ± 3.73 | 28.92 ± 3.95 | 2.62 | 0.014* |

| Vaccinated | 30.35 ± 2.83 | 29.53 ± 5.98 | 0.95 | 0.679 | |

| LA, mm | Unvaccinated | 38.15 ± 6.06 | 39.20 ± 5.73 | -2.51 | 0.013* |

| Vaccinated | 37.58 ± 7.33 | 38.91 ± 7.82 | -1.29 | 0.203 | |

| SV, mL | Unvaccinated | 74.95 ± 16.79 | 75.99 ± 17.05 | -0.35 | 0.727 |

| Vaccinated | 81.57 ± 32.12 | 78.55 ± 13.44 | 0.63 | 0.531 | |

| EF, % | Unvaccinated | 62.89 ± 7.64 | 61.39 ± 8.59 | 3.11 | 0.002** |

| Vaccinated | 63.30 ± 5.08 | 63.13 ± 6.27 | 0.27 | 0.971 | |

| FS, % | Unvaccinated | 34.37 ± 5.44 | 33.32 ± 5.58 | 2.37 | 0.017* |

| Vaccinated | 34.11 ± 3.72 | 34.44 ± 4.38 | -0.24 | 0.810 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).