1. Introduction

Whether for religious, medicinal or recreational purposes, evidence of the use of psychoactive substances by humans to produce altered states of consciousness has been widely documented across history, be it through examination of cultural texts or artefacts [

1,

2]. Acknowledgement of the negative effects of substance use has been similarly documented - in Ancient Greece the effects of alcohol withdrawal were noted by the philosopher Aristotle, who also warned against its consumption during pregnancy; Celsus, a Roman physician, considered alcohol dependence to be a disease, while more recent history reveals the Chinese government’s attempts to suppress the sale and use of opium during the 18th century [

1]. The narrative of wilful deviance was constructed, positing that addiction was associated with immoral and hedonistic individuals incapable of self-control, whereas “normal” people could consume socially sanctioned licit substances without the potential for them to become habit-forming [

1,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

Such stigmatisation is further evidenced in the manner in which substance misuse has commonly been treated from a medical standpoint: as an acute condition in speciality treatment programmes which are often financially, culturally and even geographically distinct from general healthcare [

3]. Such segregation is described by McLellan and colleagues [

3] as contributing to physicians being wilfully inattentive to pervasive substance use problems which can be present across all medical settings. Despite the often restricted perspective on substance misuse, epidemiological investigations in recent decades have increasingly acknowledged the overlap of substance use disorder (SUD) with psychiatric conditions [

8], noting that patients with such presentations are at greater risk of delayed diagnosis, more severe symptoms, reduced treatment response and impaired adherence, greater social functioning impairment, suicidal ideation, homelessness and even criminal activity [

9,

10]. It has been demonstrated that SUD, when presenting with comorbid psychiatric conditions, is associated with a more severe presentation of substance use, characterised by adolescent onset of SUD with rapid progression between first substance use and emergence of disordered usage [

11].

1.1. The Foundation for Co-Occurring Disorders

The stated overlap is termed “co-occurring disorders” (CODs); a phenomenon in which it is possible to distinguish between at least one SUD together with one (or more) co-occurring psychiatric disorder(s) [

10]. This term replaces the previously used “dual diagnosis” as it is less restrictive in terms of the number of conditions which may be presumed to co-occur [

10]. Such reconceptualization and acknowledgement provide an important framework for challenging indoctrinated stigma of SUD, however, it does not explain the mechanism by which these comorbidities occur, understanding of which may improve treatment strategies and outcomes for such afflicted individuals.

Research devoted to understanding the mechanisms which underlie human behaviours is largely summarised to indicate that great inter-individual variation and associated trajectories exist due to varying gene-environment and phenotype-environment interactions during development [

12]. As such, vulnerability for development of SUD derived from genetics and neurobiology may be relative to an individual’s developmental framework, with differing developmental factors and environmental circumstances either enhancing or protecting against this vulnerability throughout the life-course [

12]. With this consideration, two commonly applied theories for CODs relate to 1) common neurobiological vulnerability and 2) presence of pre-morbid psychiatric conditions – the self-medication hypothesis – which could be interpreted as psychiatric vulnerability for SUD development [

10,

12].

As previously reported by this study’s authors [

13], evidence to support the neurobiological vulnerability theory of CODs can be derived from the abnormal functioning of the brain-reward circuitry which may, in turn, also influence the emergence- or symptomology of other psychiatric conditions such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or mood disorder. It is noted that a bi-directional causal relationship is well established for mood disorders and SUD [

14]; chronological emergence trends of both conditions show great overlap during adolescence and young adulthood [

15], thus clear delineation of consistent earlier onset of one disorder over the other is considered problematic. The meta-analysis by Groenman and colleagues [

16] reported that childhood occurrence of ADHD, as well as other externalising disorders such as oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD), and depression were all associated with increased risk for SUD development. Contemplation of the self-medication hypothesis was discussed by these authors [

16], however, a noted caveat of this theory included the afore-mentioned bidirectionality for depression and SUD, thus leading to their conclusion that while self-medication may play a role in COD emergence, a neurobiological liability is implicated to have a profound role.

Executive function deficits implicated in the deficient cognitive- and motivational-affective symptoms of ADHD have been explained by dual- and multi-pathway models [

17]. These models consider the role of subcortical regions in motivation and reward, and their impaired connections with cortical regions, both of which are implicated in ADHD and SUD [

17]. Children with ADHD have been shown to display abnormal responses to positive reinforcement, a finding that is supported by neurobiological data in that the neurotransmitter, dopamine (DA), is strongly implicated to mediate reinforcement and brain structures innervated by dopaminergic projections from the midbrain are implicated in both reinforcement learning mechanisms and ADHD [

18]. Altered response to reinforcement is proposed as an underlying mechanism for impulsive behaviours [

18]. Impulsivity is generally not associated with depressive states of mood disorders, however, it is a common correlate and risk factor for suicidal behaviour, with consideration that the greatest proportion of attempted- and completed suicide is associated with depression [

19]. Indeed, reduced impulse control, together with irritability, aggressiveness, antisocial behaviour and alcohol abuse, is considered to be an atypical depression symptom, the described symptom array being more commonly experienced in men, who are also five times more likely than women to commit suicide [

14]. As such, impulsive behaviours, which are pervasive across many psychiatric conditions [

19] and are strongly associated with SUD emergence [

12,

17], are associated with abnormal brain-reward circuitry and this is hypothesized to have implications in the neurobiological vulnerabilities considered to underlie the phenomenon that is encompassed by the term COD.

1.2. Epidemiological Data for the Co-Occurrence of SUD with ADHD and Mood Disorders

Existing literature provides evidence to support overlap of these three conditions within substance-abusing populations. One or more SUDs are reported to be identified in up to 20% of individuals with mood disorders [

20] and approximately 50% of individuals with ADHD [

21]. In the investigation of patients attending a private rehabilitation centre in South Africa by Fabricius and colleagues [

10], co-occurring (psychiatric) disorders (CODs) were identified in 57.1% of the study population, with over 65% of these patients being diagnosed with a mood disorder and 16% with ADHD. Another South African study reported a substance use prevalence of 50% in a sample of adolescents attending psychiatric services [

22] In the study by Chan and colleagues [

11], an assessment of the pooled prevalence of internalising and externalising disorders reported in substance abuse treatment studies revealed the past year prevalence of depression to vary from 32.7% in young adolescents to 56.2% in adults over the age of 40 years, while ADHD prevalence exceeded 30% in all reported age groups. The meta-analysis by van Emmerik-van Oortmerssen and colleagues [

23] determined the mean prevalence of ADHD in SUD populations to be 23.1%.

Comorbidity rates indicate that a patient with major depressive disorder (MDD) has an 18.6% chance of also having ADHD, while the chance for an ADHD patient having MDD is 9.4% [

24]. However, lifelong prevalence of MDD indicates that 35% to-50% of adults with ADHD will experience one or more depressive episodes during their lifetime, with literature indicating that ADHD symptom severity is correlated with the occurrence of lifetime depressive episodes in both sexes [

25,

26,

27]. In contrast to ADHD, which typically present during childhood, mood disorders typically occur over a lifespan, with a cumulative prevalence which increases with age [

11], thus mood disorder populations tend to display a higher average age. It is noted that a categorical view of mood disorders includes several diagnostic terms, however, a dimensional view focusing on the harmonising characteristics of sad, irritable or empty mood together with impairing somatic and cognitive symptoms is applied when referring to mood disorder (depression) for the purpose of this investigation [

28,

29].

The South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (SACENDU) was established by the Medical Research Council of South Africa (MRC) in 1996 through funding from the World Health Organization (WHO) and is a sentinel surveillance system which is operational in all nine provinces of South Africa [

30,

31]. SACENDU’s bi-annual reports on data from July 2014 through to December 2018, refer to the term dual diagnosis, with such rates reported upon admission for SUD treatment ranging from 13% to 19% [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Of the 19% of dual diagnosis subjects referenced in SACENDU’s most recent research brief, 41% were reported to be mental illness comorbidities [

40]. Given that these statistics were based on reports upon admission and not indicative of subsequent diagnoses while receiving treatment, the true rate of mental illness comorbidity within South African substance using populations is estimated to be higher based on the existing international and South African literature.

With consideration for the described neurobiological underpinnings, together with the stated epidemiological data, the aim of this study was to establish the difference in severity of depression symptomatology between SUD comorbid with ADHD and SUD without ADHD treatment-seeking patients. The following objectives were identified to achieve, namely to:

screen for the presence of ADHD and mood disorder;

quantify depression symptom severity;

confirm a diagnosis of ADHD; and

determine the point prevalence of different CODs within a substance-using population.

2. Materials and Methods

A multi-centre, cross-sectional comparison study design made use of convenience sampling, with study participants being drawn from six substance use treatment facilities within South Africa’s Gauteng and Eastern Cape provinces. A target of 200 participants was envisioned for the study population. Participants were adults over the age of 18 years attending in-patient treatment facilities for SUD, with the applied exclusion criteria being a history of head injury or non-completion of primary school-level education.

2.1. Data Collection Instrumentation

Data collection consisted of two stages, each including collection of specific information from participants with the application of validated psychometric tools:

- 2.

Diagnostic phase

2.1.1. The Adult ADHD Self Report Scale (ASRS) Vers 1.1

The ASRS is designed for collection of ADHD symptoms in the context of adulthood by relating symptoms to adult situations such as work, tasks or projects [

41]. This reliable and valid self-administered instrument was jointly developed in 2005 by the WHO and Kessler and colleagues [

42]. The ASRS v1.1 consists of 18 questions which are based on the criteria used for diagnosing ADHD in the DSM-IV-TR (Text Revision) [

42]. Six of these items – the ASRS Part A (ASRS-A) – have been found to be most predictive of symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of ADHD [

42].

2.1.2. Beck Depression Inventory

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is one of the most extensively used measures for measurement of the intensity of depression in psychiatric populations and detection of depression in normal populations [

43,

44]. The instrument was derived from clinical observations of the attitudes and symptoms often displayed by depressed psychiatric patients, with systematic consolidation into 21 symptoms and attitudes [

43]. These items were included to assess the intensity of depression as they are based on its main symptoms, as such the tool is generally considered to have high content validity [

44]. It is noted that although the tool was designed to be administered by trained interviewers, it is most often self-administered [

43]. Despite the BDI being developed as a screening tool, it can also be applied to confirm a diagnosis of depression [

45].

2.1.3. Diagnostic Interview for ADHD in Adults (DIVA 2.0)

The DIVA 2.0 interview allows for thorough evaluation of DSM-IV-TR criteria for ADHD in adulthood [

46]. It is divided into two domains to assess symptoms applicable to childhood (before age 12) and adulthood, while the third part considers functional impairment in five areas of functioning in both age categories [

46]. The study conducted by Ramos-Quiroga and colleagues [

46] reported that the DIVA 2.0 has similar psychometric properties to what is considered to be the gold standard diagnostic interview for adult ADHD (Conners’ Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV [CAADID]), while good correlation was found with the Wender Utah Rating Scale (WURS) for evaluating childhood symptoms. Overall the study authors concluded that it was a reliable diagnostic tool with good predictive value for the diagnosis obtained [

46].

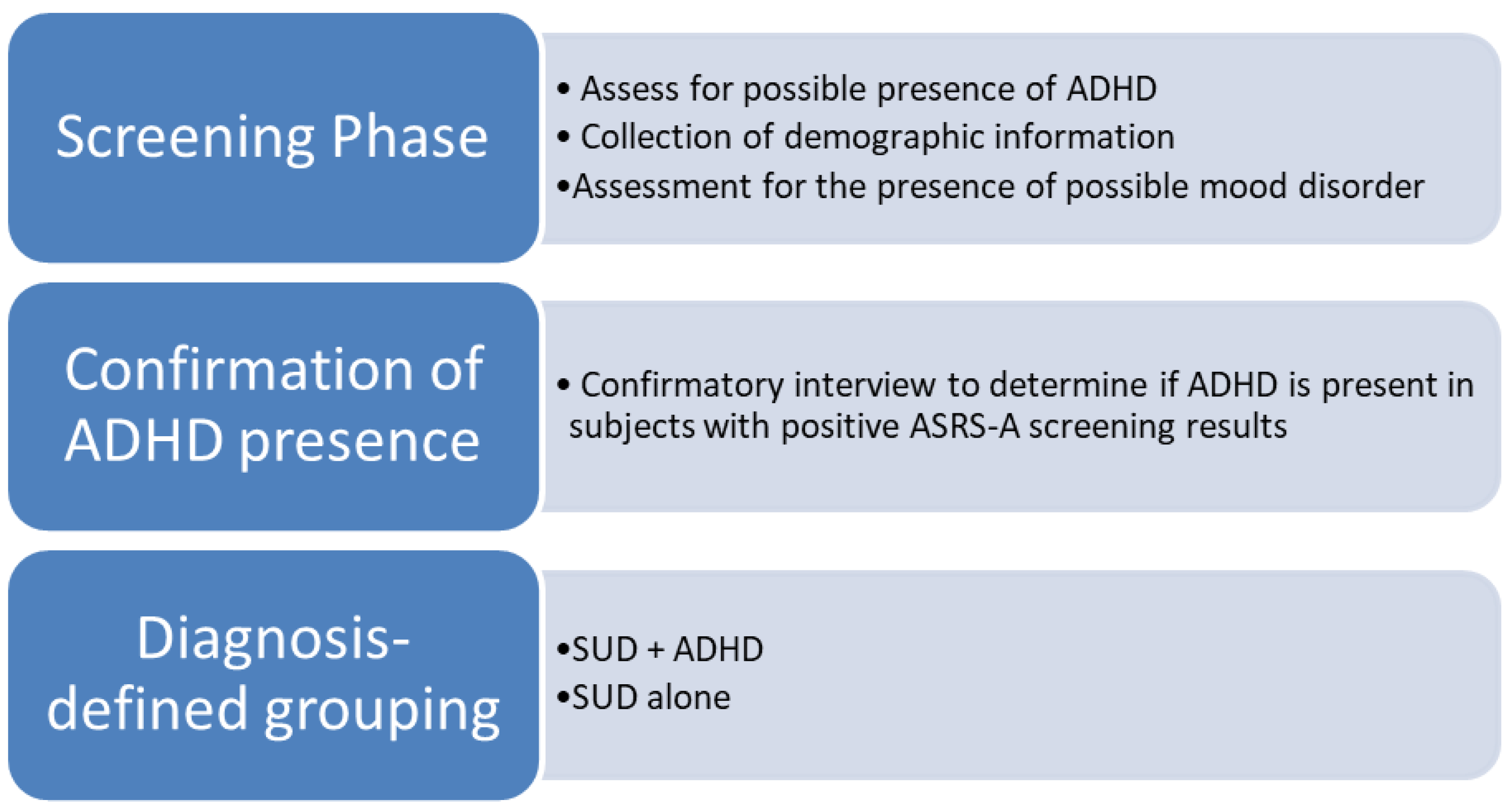

2.2. Data Collection Process

The primary stage of data collection consisted of screening in which the possible presence of adult ADHD and mood disorder was assessed. The secondary, diagnostic phase involved all participants who screened positively for ADHD based on the ASRS-A results being interviewed, with application of the Diagnostic Interview for ADHD in Adults (DIVA) to confirm the presence of ADHD. Following this, participants were grouped according to diagnoses: SUD with ADHD (SUD + ADHD) and SUD with ADHD (SUD - ADHD). This process is illustrated in

Figure 1. Data was collected between July 2018 and June 2019 by three study colleagues within the different regions.

2.3. Ethical Approval

Permission to conduct the study at each of the treatment facilities was arranged individually via the respective management entities with consideration for the previously granted ethical approval for the investigation from the Nelson Mandela University Research Ethics Committee (Human) (H14-HEA-PHA-081). The study participants were provided with a document describing the investigation processes. This was accompanied by the present researcher(s) giving a general address to describe the processes and applied instruments with the opportunity for questions from participants to be answered. Informed consent was obtained from participants prior to completion of the data collection tools.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed using Statistica v. 12 (Dell Software). A 2 x 2 x 3 (ADHD group x gender x age group) ANOVA model was employed to indicate between-group differences. Post-hoc (Bonferroni) analysis was employed to reveal within-group differences.

3. Results

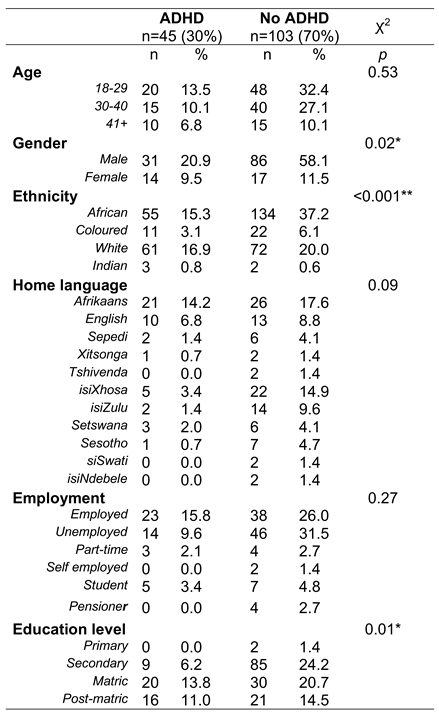

Screening for ADHD produced a total of 153 subjects, however, ADHD diagnosis could not be verified in 5 of the participants. A total of sample size of 148 participants was thus achieved, with diagnostic stratification represented as follows: SUD + ADHD, n = 45 and SUD – ADHD, n = 103.

Study participants represented eight of South Africa’s nine provinces. The greatest provincial representation was for Gauteng (43.24%, n = 64), followed by the Eastern Cape (34.46%, n = 51), Limpopo (6.76%, n =10), Mpumalanga (6.08%, n = 9), KwaZulu-Natal (2.70%, n = 4), Western Cape (2.70%, n = 4), North-West Province (2.03%, n = 3) and Free State (2.03%, n = 3). Participant home language endorsement revealed that all of South Africa’s 11 official languages were included in the study sample, the greatest proportion of participants being Afrikaans-speaking (31.76%, n = 47), followed by Xhosa (18.24%, n = 27), English (15.54%, n = 23) and Zulu (10.81%, n = 16).

More than half of the study participants endorsed African ethnicity (53.38%, n = 79) and the study population was predominantly male (79.05%, n = 117). A mean age of 31.76 ±10.08 years was obtained, with the female portion of the study population being slightly older on average at 33.68 ±8.63 years against 31.25 ±10.37 years for men. Further demographic considerations are depicted in

Table 1.

Table 2 indicates the result of the ANOVA analysis.

There was a significant main effect of ADHD diagnosis: F(1, 135) = 12.45, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.08, and a significant main effect of gender: F(1, 135) = 4.78, p = 0.03, ηp2 = 0.03 on depressive symptoms as indicated by the Beck scale scoring.

There was no effect of age, neither main, nor interacting.

Post-hoc analysis (Bonferroni) revealed that only the male ADHD group (M = 25.81, SD = 11.59) had significantly higher scores than the non-ADHD males (M = 16.34, SD = 10.95) on the Beck scale: p < 0.001.

The difference in scores between the female ADHD group (M = 31.36, SD = 11.91) and the Non-ADHD group (M = 21.12, SD = 11.42) did not differ significantly: p = 0.08, alhough it approached significance.

4. Discussion

The target study sample size was not met, however, the achieved sample of 148 subjects was considered adequate. Ethnic representation, viewed together with the inclusion of all official languages of South Africa, was considered favourable, although it diverged from the 2019 mid-year population estimates for South Africa, with over- and disproportionate representation of Caucasian and mixed-race participants [

47]. This disproportional representation could be due to historical inequality within South Africa as a result of its former apartheid regime, with it being noted by Myers and colleagues [

48] that historically disadvantaged groups may experience limited access to substance abuse treatment. With respect to ADHD prevalence within the sample as a function of ethnicity, it was noted that only 16.85% (n = 89) of the African participants were confirmed to have ADHD against 51.11% (n = 45) of Caucasian participants, a finding which could be construed to infer a lower prevalence of ADHD within this ethnic division. However, it has been previously reported that although the ASRS has been shown to have adequate internal consistency within a multi-cultural South African population sample, problems were experienced with relating the English tool to indigenous-African language speakers [

49], as such it is considered that culturally-related condition inferences based on the ethnic representation reported in this investigation should be interpreted with caution.

It was noted that a greater number of participants endorsed completion of matric and post-matric education within the non-ADHD group, however the relative proportions were higher for the ADHD group in these categories. This was not anticipated given that presence of ADHD is typically associated with lower education levels [

28]. However, given that the study sample was drawn from substance abusing populations, associated with cognitive impairment [

50], it is perhaps not remarkable.

The sample was notably predominated by men, representing 79.05% of the total study population (N = 148). SUD has been described as a “male-dominated” disorder with men making up over 70% of substance users, a finding replicated in the study by Arfken and colleagues [

51]. With consideration for existing literature indicating greater tendencies towards impulsivity in men as evidenced by a higher prevalence rate of impulse-control related conditions such as ADHD [

28], greater expression of impulsivity as an atypical symptom of depression and a higher rate of suicide [

14] against the established theory of SUD being associated with heightened impulsivity derived from abnormal functioning of the brain-reward circuitry [

17], it is perhaps expected that SUD should be more prevalent in men. However, it is also posed that research in substance use populations has been historically skewed towards the outcomes in men [

52]. Despite lower prevalence rates of SUDs in women, women presenting for SUD treatment are reported to experience more severe problems [

52]. It is noted that 83.87% (n = 31) of the women in the study sample were identified as having CODs against 68.38% (n = 117) of the male participants, possibly reflecting such trends of women experiencing greater psychiatric problems upon referral or admission for SUD treatment [

52]. It is proposed that reasons for this phenomenon are multifactorial, including more financial barriers to accessing treatment, reduced availability of time to attend treatment and a greater susceptibility to stigmatisation, culminating in treatment avoidance with associated exacerbation of existing conditions [

52].

The presence of ADHD was found to be associated with greater mean depressive symptom severity, with post-hoc analysis revealing that this was only significantly so for male participants. It was noted that this finding approached significance for the female participants, it being contemplated that a significant association might have been identified had the sample size been larger. Further to the interaction of ADHD on severity of mood disorder experienced by study participants, it was also noted that the prevalence of ADHD in the study population was skewed towards co-presentation with mood disorder; 86.67% (n = 45) of participants with ADHD also experienced mood disorder. Previous investigation into the co-morbid presentation of ADHD and mood disorder has been without resolve for determination of the extent to which this presentation is due to either genetic or environmental factors [

21]. However, with both conditions being highly impairing, it has been shown that the course of depression in the presence of ADHD is associated with an earlier age of onset of depression, longer durations of depressive episodes, higher rates of suicidality, greater risk and poorer long-term outcomes [

21,

53]. It is considered that this interplay, particularly with the increase in suicidality which further implicates increased impulsivity, may also infer the involvement of the brain reward circuitry given its role in eliciting euphoria and anhedonia, with such extremes of mood being implicated in mood disorder symptomology [

54]. It is noted that the study by Howard and colleagues [

55] determined that depression and ADHD appear to be independent, additive sources contributing to substance use risk.

With consideration for prevalence rates for CODs reported in other South African data, it was noted that the identified COD rate in the study population was over three times greater than the highest rate reported by SACENDU [

40] and 14.5% higher than the rate reported by Fabricius and colleagues [

10]. These findings support the speculation that identification of CODs is under-recognised in South African SUD populations, emphasising the need for appropriate screening and surveillance incorporating associated results to allow for improved prevalence reporting.

The influence of ADHD on mood disorder severity identified in this study is consistent with existing literature, however further investigation is warranted to determine if the interaction of gender within the ADHD group remains only significant for men. A key consideration relates to the contrasts identified with respect to COD prevalence rates in South Africa, emphasising the need to undertake comprehensive screening for psychiatric comorbidities in SUD treatment settings. Further investigation incorporating such activity may provide an improved view of the extent of CODs and their potential influence on SUD treatment outcome.

The findings of this study should be considered against the following limitations:

Diagnostic screening was limited to ADHD and mood disorder, thus there is potential for other comorbid psychiatric disorders to have been present in the study population.

No confirmatory procedure was applied to test the validity of positive mood disorder screening. The decision to omit such activity was related to mood disorders being routinely screened for in psychiatric settings and the potential application of the BDI as a diagnostic tool.

Diagnoses elicited as a result of the applied instrumentation were not confirmed by a treating physician at the facilities sampled.

5. Conclusions

Despite a long history of mankind’s consumption of substances for the purpose of producing altered states of consciousness, the negative effects thereof have also been recorded since antiquity. Excessive substance use has been, and often continues to be, viewed as a failing of moral character; a vice of the wilfully deviant and hedonistic. Such stigmatisation is evident in the manner in which substance misuse has been treated medically – distinct from general medicine. However, research in more recent decades has revealed the folly in this perception by identifying the high levels of psychiatric co-morbidity often accompanying SUD.

The complex interplay between SUDs and CODs allows for a degree of reconceptualization of SUDs and their long-associated stigma. Consideration for SUDs being a response to attempt self-medication of a psychiatric condition or arising due to a common pathway to elicit a COD provides a framework to better understand substance use motivations and, perhaps, more importantly, identify suitable targets to prevent development of substance use. It is proposed that the brain reward circuitry is implicated in the neurobiological vulnerability to develop both SUD and ADHD as well as other psychiatric conditions. It is of concern that SUDs interact with CODs to aggravate the presentation of all conditions.

Existing literature reveals overlap of SUD with ADHD and mood disorders, with previous investigations identifying higher prevalence rates of each condition in psychiatric populations. However, data from South Africa appears to underestimate the prevalence of CODs.

This study sought to determine the influence of ADHD on severity of mood disorder in substance abusing populations. Objectives were to screen for the presence of ADHD and mood disorder by applying the ASRS and BDI, with confirmation of the ADHD diagnosis with application of the DIVA structured diagnostic interview. Participants were grouped based on the presence or absence of ADHD for purposes of comparison with application of a 2 x 2 x 3 ANOVA model.

A total sample of 148 participants was achieved, with a fair representation of the demographic variation in South Africa. Statistical analysis revealed a significant main effect of ADHD diagnosis and a significant main effect of gender on depressive symptom severity, however, post-hoc analysis revealed that only the male ADHD group had significantly higher scores on the BDI. However, consideration was given to the results of the analysis of the female portion, showing that significance was approached, a result which may have been more robust with a larger study sample.

The prevalence rates of CODs were found to be higher than corresponding literature from South African studies, possibly implicating a gap in SUD assessment for CODs. This emphasises the need for incorporation of screening practices to identify CODs in these populations, especially given the potential exacerbation of CODs on overall outcomes for SUD, as well as further between-condition interactions in the presence of more than one COD as was identified in this investigation.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Permission to conduct the study at each of the treatment facilities was arranged individually via the respective management entities with consideration for the previously granted ethical approval for the investigation from the Nelson Mandela University Research Ethics Committee (Human) (H14-HEA-PHA-081).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study as required by the Research Ethics Committee (Human) of Nelson Mandela University.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset presented in this article is not available due to the ethical agreement signed by the university. Requests to access the dataset should be directed to the chairperson of the university’s research ethics committee.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the patients who participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADHD |

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

| CD |

Conduct Disorder |

| COD |

Co-occurring Disorder |

| MDD |

Major Depressive Disorder |

| ODD |

Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) |

| SUD |

Substance Use Disorder |

References

- Crocq M-A. Historical and cultural aspects of man’s relationship with addictive drugs. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2007;9(4):355-361. [CrossRef]

- Stolberg VB. Historical images and reviews of substance use and substance abuse in the teaching of addiction studies. J Teach Addictions. 2009;8:65-83. [CrossRef]

- McLellan AT, Starrels JL, Tai B, et al. Can substance use disorders be managed using the chronic care model? Review and recommendations from a NIDA Consensus Group. Public Health Reviews. 2014;35(2):1-14. [CrossRef]

- Mora-Ríos J, Ortega-Ortega M, Medina-Mora ME. Addiction-related stigma and discrimination: a qualitative study in treatment centers in Mexico City. Subst Use Misuse, 2017;52(5):594-603. [CrossRef]

- Robb J, Chou C-C, Johnson L, et al. Mediating effects of social support and coping between perceived and internalized stigma for substance users. J Rehabil. 2018;84(2):14-21.

- Witte TH, Schroeder CC, Hackman CL. Stigma and substance use: can undergraduate instruction in addiction studies change stigmatizing attitudes? [Letter to the editor]. J Alcohol Drug Educ. 2018;62(3):9-15.

- Yang LH, Wong LY, Grivel MM, et al. Stigma and substance use disorders: an international phenomenon. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2017;30(5):378-388.

- Havassy BE, Alvidrez J, Owen KK. 2004. Comparisons of patients with comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders: implications for treatment and service delivery. Am J Psychiatry. 2004; 161(1):139–145. [CrossRef]

- Langås A-M, Malt UF, Opjordsmoen S. Comorbid mental disorders in substance users from a single catchment area – a clinical study. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11(25):1–12. [CrossRef]

- Fabricius V, Langa M, Wilson K. An exploratory investigation of co-occurring substance related and psychiatric disorders. J Subst Use. 2008;13(2):99–114. [CrossRef]

- Chan Y-F, Dennis ML, Funk RR. Prevalence and comorbidity of major internalizing and externalizing problems among adolescents and adults presenting to substance abuse treatment. Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;34:14–24. [CrossRef]

- Sloboda Z, Glantz MD, Tarter RE. Revisiting the concepts of risk and protective factors for understanding the etiology and development of substance use and substance use disorders: implications for prevention. Subst Use Misuse. 2012;47:944–962. [CrossRef]

- Regnart J, Truter I, Meyer A. Critical exploration of co-occurring attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, mood disorder and substance use disorder. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2017;17(3):275-282. [CrossRef]

- Fountoulakis KN. The emerging modern face of mood disorders: a didactic editorial with a detailed presentation of data and definitions. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2010;9(14):1–22. [CrossRef]

- Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, et al. Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(4):359–364. [CrossRef]

- Groenman AP, Janssen TWP, Oosterlaan J. Childhood psychiatric disorders as risk factor for subsequent substance abuse: a meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(7):556–569. [CrossRef]

- Molina BSG, Pelham WE (Jr). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and risk of substance use disorder: developmental considerations, potential pathways, and opportunities for research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:607–39. [CrossRef]

- Tripp G, Wickens JR. Neurobiology of ADHD. Neuropharmacology. 2009;57:579–589.

- Saddichha S, Schuetz C. Impulsivity in remitted depression: a meta-analytical review. Asian J Psychiatr. 2014;9:13–16. [CrossRef]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and 680 related conditions. Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29(2):107–120. [CrossRef]

- Taurines R, Schmitt J, Renner T, et al. Developmental comorbidity in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. ADHD Atten Def Hyp Disord. 2010;2(4):267–289. [CrossRef]

- Taukoor B, Paruk S, Karim E, et al. Substance use in adolescents with mental illness in Durban, South Africa. J Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2017;29(1):51-61. [CrossRef]

- van Emmerik-van Oortmerssen K, van de Glind G, van den Brink W, et al. Prevalence of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in substance use disorder patients: a meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;122(1–2):11-19.

- Goodman D. Adult ADHD and comorbid depressive disorders: diagnostic challenges and treatment options. Prim Psychiatry. 2009;16(7):5–7. [CrossRef]

- Sobanski E. Psychiatric comorbidity in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256(1):26–31. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders [Text revision] (DSM-IV-TR). 4th ed. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- Knouse LE, Zvorsky I, Safren SA. Depression in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): the mediating role of cognitive-behavioral factors. Cognit Ther Res. 2013; 37(6) 1220–1232. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Nandi A, Beard JR, Galea S. Epidemiologic heterogeneity of common mood and anxiety disorders over the lifecourse in the general population: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9(31):1-11.

- Parry CDH, Bhana A, Plüddemann A, et al. The South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (SACENDU): description, findings (1997-99) and policy implications. Addiction. 2002;97(8):969-976. [CrossRef]

- Parry C, Plüddemann A, Bhana A. Monitoring alcohol and drug abuse trends in South Africa (1996-2006): reflections on treatment demand trends. Contemp Drug Probl. 2009;36(3/4)685-703. [CrossRef]

- Dada S, Harker Burnhams N, Erasmus J, et al. Monitoring alcohol, tobacco and other drug abuse trends in South Africa (July – December 2014) (Phase 37). SACENDU Update. 2015;37:1-2.

- Dada S, Harker Burnhams N, Erasmus J, et al. Alcohol and drug abuse trends: January – June 2015 (Phase 38). SACENDU Update. 2015;38:1-3.

- Dada S, Harker Burnhams N, Erasmus J, et al. Alcohol and drug abuse trends: July – December 2015 (Phase 39). SACENDU Update. 2016;39:1-2.

- Dada S, Harker Burnhams N, Erasmus J, et al. Alcohol and other drug use trends January – June 2016 (Phase 40). SACENDU Update. 2016;40:1-2.

- Dada S, Harker Burnhams N, Erasmus J, et al. Monitoring alcohol, tobacco and other drug use trends in South Africa July – December 2016 (Phase 41). SACENDU Update. 2017;41:1-2.

- Dada S, Harker Burnhams N, Erasmus J, et al. Alcohol and other drug use trends: January – June 2017 (Phase 42). SACENDU Update. 2018;42:1-2.

- Dada S, Harker Burnhams N, Erasmus J, et al. Alcohol and other drug use trends (South Africa): July – December 2017 (Phase 43). SACENDU Update. 2018;43:1-3.

- Dada S, Harker Burnhams N, Erasmus J, et al. Monitoring alcohol, tobacco and other drug use trends (South Africa): January – June 2018 (Phase 44). SACENDU Update. 2019;44:1-4.

- Dada S, Harker Burnhams N, Erasmus J, et al. Monitoring alcohol, tobacco and other drug use trends (South Africa): July – December 2018 (Phase 45). SACENDU update. 2019;45:1-3.

- Yeh C-B, Gau SS-F, Kessler RC, et al. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the adult ADHD Self-report Scale. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2008;17(1):45–54. [CrossRef]

- Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, et al. The World Health Organization adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol Med. 2005;35(2):245–256. [CrossRef]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:77-100. [CrossRef]

- Richter P, Werner J, Heerlein A, et al. On the validity of the Beck Depression Inventory: a review. Psychopathology. 1998:31(3);160-168.

- Pop-Jordanova N. BDI in the assessment of depression in different medical conditions. Pril (Makedon Akad Nauk Umet Odd Med Nauki). 2017:38(1):103-111. [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Quiroga JA, Nasillo V, Richarte V, et al. Criteria and concurrent validity of DIVA 2.0: a semi-structured diagnostic interview for adult ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2019;23(10):1126-1135. [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. Mid-year population estimates 2019. South Africa; 2019. Available from: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022019.pdf.

- Myers BJ, Louw J and Pasche SC. 2010. Inequitable access to substance abuse treatment services in Cape Town, South Africa. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2010;5(28)1-11. [CrossRef]

- Regnart J, Truter I, Zingela Z, et al. A pilot study: use of the Adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Self-Report Scale in a South African patient population. S Afr J Psychiatry. 2019;25(0), a1326. [CrossRef]

- Block RI, Erwin WJ, Ghoneim MM. Chronic drug use and cognitive impairments. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002 Oct;73(3):491-504. [CrossRef]

- Arfken CL, Klein C, di Menza S, et al. Gender differences in problem severity at assessment and treatment retention. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2001 Jan;20(1):53-7. [CrossRef]

- Green CA. Gender and use of substance abuse treatment services. Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29(1):55-62.

- McIntosh D, Kutcher S, Binder C, et al. Adult ADHD and comorbid depression: a consensus-derived diagnostic algorithm for ADHD. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:137–150. [CrossRef]

- Shirayama Y, Chaki S. Neurochemistry of the nucleus accumbens and its relevance to depression and antidepressant action in rodents. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2006;4:277–291. [CrossRef]

- Howard AL, Kennedy TM, Macdonald EP, et al. Depression and ADHD-related risk for substance use in adolescence and early adulthood: concurrent and prospective associations in the MTA. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2019 Dec;47(12):1903-1916. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).