1. Introduction

Accumulating epidemiological evidence indicates that infection with Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg), which is a major periodontal pathogen, cause a large number of systemic diseases, including atherosclerosis, hypertension, adverse pregnancy outcomes, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes mellitus, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, rheumatoid arthritis and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [

1]. Recently, it has been reported that approximately 40% of patients diagnosed with AD lack AD pathology including the cerebrospinal fluid levels of amyloid-β42 and phosphorylated tau [

2]. Therefore, microglia-mediated neuroinflammation is considered a key driver of dementia associated with a variety of diseases including AD. Moreover, Pg can influence the development development of these periodontitis-related systemic disorders by affecting the adaptive immune response and inducing inflammation and innate immune responses [

1]. In contrast, Pg is a relatively poor inducer of proinflammatory cytokines [

3,

4]. Pg lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulated an inflammatory response when injected into connective tissue but was minimally stimulatory when a systemic response was measured [

5,

6]. Furthermore, Pg LPS is a weaker Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2/4 agonist and NF-κB/STAT signaling activator in BV-2 microglia than in E. coli LPS [

7]. The presence of fewer acyl chains and phosphate groups in Pg LPS-lipid A than E. coli-lipid A may be responsible for the weaker activating properties of Pg LPS. These low biological activities may allow Pg to evade innate host defense mechanisms without endotoxin tolerance, leading to chronic inflammation. However, the mechanisms by which Pg LPS can augment local systemic immune and inflammatory responses remains unclear.

There is a strong association between depression and elevated levels of inflammation. It has been reported that social stress enhances Pg LPS-induced inflammatory responses by CD11b-positive cells [

8]. Chronic stress can significantly enhance the pathological progression of periodontitis through an adrenergic signaling-mediated inflammatory response [

9]. Moreover, stress-induced microglial activation, anxiety-like behaviors and IL-1β production were inhibited by a pharmacological blockade of adrenergic receptors [

10,

11,

12]. We previously reported that noradrenaline (NA) induces the production of IL-1β through the activation of β2 adrenergic receptors (Aβ2R)/exchange proteins directly activated by cAMP (Epac), which activates AP-1-mediated transcription [

13]. Moreover, both NF-κB and AP-1 play important roles as transcription factors in the expression of IL-1β, which is a critical step in inflammation through the induction of other proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines [

14,

15].

Therefore, we hypothesized that NA may enhance neuroinflammation following systemic stimulation with Pg virulence factors, because enhanced NA release is a central response to stress. In the present study, we investigated the possible functional interaction between NA and Pg virulence factors in the production of IL-1β by BV-2 microglia. 61

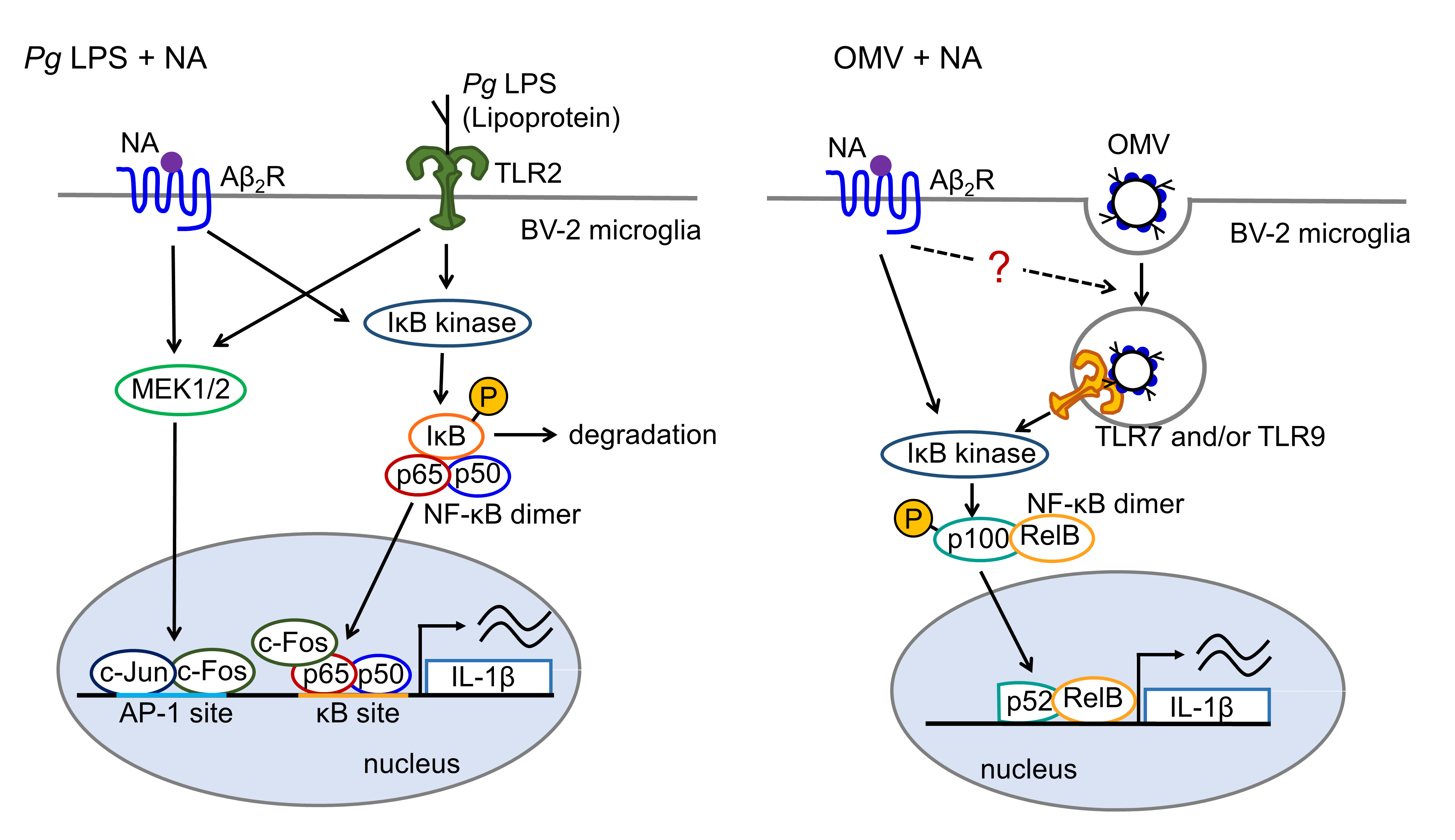

3. Discussion

In this study, NA augmented Pg virulence factor-induced IL-1β transcriptional activities up to 20-fold without affecting either peak or duration time. Considering that higher amounts of NA are released from nonsynaptic varicosities noradrenergic terminals, especially under stress conditions, Aβ2R on microglia surrounding noradrenergic terminals can be activated. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report showing that NA synergizes with Pg virulence factors to up-regulate the expression of IL-1β in the microglia.

We recently reported that the delivery of gingipains into cerebral microvascular endothelial cells, probably through OMVs, may be responsible for blood-brain-barrier damage through intracellular degradation of tight junction proteins, ZO-1 and occludin [

24]. Therefore, it is likely that circulating

Pg virulence factors are augmented by NA in the brain parenchyma. Several studies have reported anti-inflammatory effects of NA, which is contrary to our findings [

25,

26]. The anti- and pro-inflammatory effects of NA are intriguing paradoxes. One aspect common to the above-mentioned studies has been suggested that experiments showing an anti-inflammatory effect of NA are mostly conducted in the combination with

E. coli LPS treatment, which induces the translocation of NF-

κB into the nucleus [

27]. However, in the present study, we observed that NA augmented the

Pg LPS-induced production of IL-1

β. We previously reported that

Pg LPS-induced luciferase activity in BV-2 microglia was almost completely suppressed by a specific TLR2 antagonist, C29, but not by a specific TLR4 agonist, TAK-242 [

16,

17]. These observations indicate that

Pg LPS-induced luciferase activity in BV-2 microglia is mediated by lipoproteins via TLR2. Therefore, this discrepancy may be due to the difference in TLRs activated by

Pg lipoproteins and

E .coli LPS. Further studies are needed to fully understand the paradoxical effects of NA.

NF-

κB and AP-1 play important roles as transcription factors in the expression of various genes induced by bacterial LPS, including

Pg LPS. Therefore, using specific inhibitors of NF-

κB or AP-1, we investigated the involvement of these transcription factors in the production of IL-1

β following treatment with NA,

Pg LPS, and their combination. NAI and SR11302 inhibited the mean levels of luciferase activity induced by NA alone or

Pg LPS alone by approximately 30-40%. In contrast, NAI and SR11302 inhibited the mean levels of lucife rase activity induced by NA plus

Pg LPS by approximately 80% and 20%, respectively. Therefore, it is considered that the increased promoter activity of the

κB sites is responsible for the synergistic effect of NA and

Pg LPS on the production of IL-1

β in BV-2 microglia. A typical structure of NF-

κB is the p50-p65 dimer (NF-

κB1/RelA), because dimer formation is necessary for DNA binding. The

N-terminal regions of the dimer are responsible for specific DNA contact. In contrast, the

C-terminal regions are usually highly conserved, and are responsible for dimerization and nonspecific DNA phosphate contact. AP-1 transcription factors are dimers composed of members of the c-Fos and c-Jun protein families. AP-1 c-Fos can enhance the NF-

κB target gene expression by binding to AP-1 sites. Moreover, the basic zipper domains of AP-1 c-Jun and c-Fos physically interacts with the Rel-homology domain of p65, forming a transcription complex with enhanced DNA binding and potentiated biological functions [

18]. Considering that the inhibitory effect of SR11302, which blocks the binding of AP-1 to the promoter region, was lower than NAI, AP-1 may physically interacting with p65 to enhance its binding of p65 to the

κB sites in the present study. In this study, we found that c-Fos directly binds to p65 by co-immunoprecipitation combined with western blotting following co-treatment with NA and

Pg LPS. Furthermore, the structural models generated by AlphaFold 2 in this study suggest that the binding of c-Fos to the p65:p50 heterodimer induces a conformation change of DNA to form hydrogen bonds between c-Fos and DNA, which is likely to enhance the stabilization of the protein-DNA complex. Persistent NF-

κB the protein-DNA complex. Persistent NF-

κB activation is a hallmark of chronic Inflammatory diseases, including neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and arthritis [

28,

29].

On the other hand, OMVs carry various virulence factors including LPS, gingipains (Arg-gingipain and Lys-gingipain), FimA, DNA and cell wall components, that could elicit various inflammatory and immune responses [

30].

Pg LPS and gingipains are directly detected by TLR2 and protease-activated receptor 2 on the cell membrane, respectively [

31]. In the present study, NAI and SR11302 showed no or moderate inhibitory effects on luciferase activity induced by OMVs alone and OMVs plus NA, suggesting that OMVs and OMVs plus NA activate transcriptional pathways other than either NF-

κB p65 or AP-1. We have previously reported that OMVs are quickly phagocytosed by BV-2 microglia, and that the phagocytic/endocytic pathway is required for the production of IL-1

β [

17]. It was also noted that the amounts of proIL-1

β and an unconventional 20-kDa form of IL-1

β were markedly increased in the cell lysates of BV-2 microglia after stimulation with NA plus OMVs relative to stimulation with either NA or OMVs alone. It has been reported that LPS treatment produces the 20-kDa form of IL-1

β intracellularly [

32]. In contrast, leaked proIL-1

β from LPS-primed microglia after ATP stimulation is processed into the 20-kDa form of IL-1

β by cathepsin D [

33,

34]. It is suggested that the formation of the 20-kDa form of IL-1

β prevents the generation of mature IL-1

β and thus may limit inflammation, because the 20-kDa form of IL-1

β is minimally active at IL-1R1 and is not further cleaved to highly active 17-kDa mature form [

34].

RNA and DNA in bacterial OMVs are recognized by TLR7/TLR8 and TLR9 in phago-endosomes, respectively. We found that the TLR7/9 inhibitor E6446 significantly suppressed the luciferase activity induced by both OMVs alone and NA plus OMVs. Moreover, the p52 inhibitor SN52 significantly suppressed the luciferase activity induced by both OMVs alone and NA plus OMVs. OMVs are thought to induce inflammatory and immune responses through the activation of the TLR7/9-p52/RelB-mediated pathway after phagocytosis. However, the mechanisms for the NA plus OMV-induced synergistic effect remain unclear in this study. It is likely that A

β2R/Epac-mediated pathway enhances trafficking of endosomes and/or phagosomes to promote their fusion, because Epac-Rap1 signaling was suggested to play an important role in the interaction between late endosomes and phagosomes [

35]. The precise molecular mechanisms underlying the synergistic effects of the NA and OMV-induced production of IL-1

β in BV-2 should be elucidated in future studies.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

NA, U0126,a MEK inhibitor, and NAI, an inhibitor of NF-κB p65 transcriptionally activity, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Wedelolactone, an IκB kinase (IKK) inhibitor, was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd (Tokyo, Japan). SR11302, an inhibitor of AP-1 c-Fos transcriptional activity, was purchased from MedChem Express (Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA). Standard Pg LPS, a TLR4/TLR2 agonist, was purchased from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA, USA).

4.2. Cell Culture

The BV-2 cells, a murine microglial cell line [

36], and a well-accepted alternative to primary microglia [

37,

38], were used in this study. BV-2 microglia were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, penicillin, and streptomycin. To establish NanoLuc (Nluc) probe-expressing cells (Nluc reporter BV-2 microglia), we infected the cells with a lentiviral vector carrying the Nluc probe as described previously [

13]. The Nluc luciferase protein is retained only when the proteolytic processing of IL-1

β is successful, as it can be escape proteasome degradation.

4.3. Measurement of the Luciferase Activity (RLU)

Nluc reporter reporter BV-2 microglia were plated in 96-well white culture plates at a density of 5 104 cells per well. After overnight culture, drug treatments were performed, and luciferase activity following treatment with NA (1 or 3 µM), Pg LPS (10 or 30 µg/mL) or OMVs (150 µg of protein/mL) was measured using a luminometer (GloMax; Promega Corp., Madison, WS, USA) with a Nano-Glo® luciferase assay system (N1110; Promega Corp.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RLU induced by NA, Pg LPS or OMVs was then measured in sum of cells and culture media. Each treatment was repeated in triplicate on the same plate

4.4. Bacterial Culture and Isolation of OMVs

Pg ATCC33277 was maintained as previously described [

24]. OMVs were prepared ultracentrifugation as previously described [

24].

4.5. RT-qPCR

The mRNA levels of IL-1

β expressed in BV-2 microglia were measured by RT-qPCR as previously described [

16,

39]. The primer pair sequences were as follows: IL-1

β, 5

’-CAACCAACAAGTGATATTCTCCAT-3’ and 5

’-GATCCACACTCTCCAGCTGCA-3

’;

β-actin, 5

’-GGCATTGTGATGGACTCCG-3

’ and 5

’-GCTGGAAGGTGGACAGTGA-3

’. For data normalization, an internal control (

β-actin) was used for cDNA input, and the relative units were calculated using a calibration curve method. Experiments were repeated three times, and the results are presented as the mean

± standard error.

4.6. Immunoassay for IL-1β

The concentrations of IL-1β in the cell lysates of BV-2 microglia were measured using a LumitTM IL-1β (Mouse) Immunoassay (Promega) 1 h after treatment with NA, Pg LPS, OMVs, NA plus Pg LPS, and NAplus OMVs, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Luminescence generated, which was proportional to the amount of IL-1β, was measured using a multimode plate reader EnSight (Parkin-Elmer, Shelton, CT, USA).

4.7. Immunoblotting

BV-2 microglia were seeded in a 6 cm petri dish at a density of 3.3 106cells/dish for 1 day. After treatment with NA(3

µM),

Pg LPS (30

µg/mL) or OMVs (150

µg protein/mL), and their combination, each specimen was electrophoresed using 15% SDS-polyacryl-amide gels, and then proteins on the SDS gels were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and immunoblotted as previously described [

39]. The primary antibodies used were as followings: goat anti-IL-1

β antibodies (1:1000; R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA); rabbit anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) antibodies (1:1000; Proteintech, Tokyo, Japan).

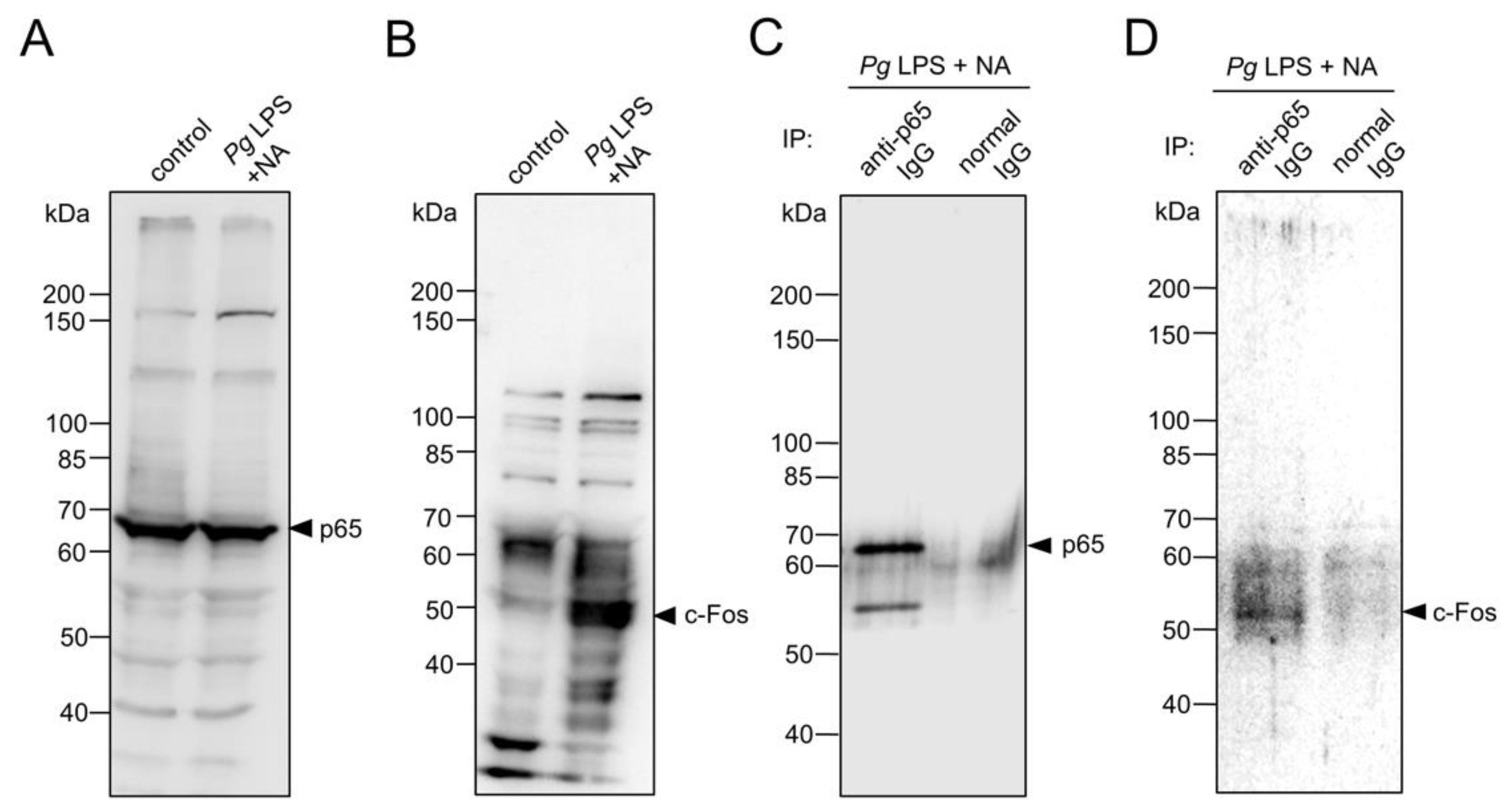

4.8. Co-Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblot Analysis

BV-2 microglia were seeded in a 10 cm petri dish at a density of 3.3 106cells/dish for overnight. After treatment with NA(3 µM), Pg LPS (30 µg/mL), and their combination, cells were collected and cell lysates (1 mg of protein/each) were performed immuno-precipitation using Pierce co-immunoprecipitation Kit (Thermo Fischer Scientific) according to manufacture’s instructions. The antibodies for immunoprecipitation were rabbit anti-NF-κB p65 antibodies (20 µL; ab2071297, Abcam, Tokyo, Japan). Immuno-precipitates were separated on a !0% SDS-PAGE gel, transferred to PVDF membrane, and immunoblotted. The primary antibodies for immunoblotting used were as follows: rabbit anti-c-Fos antibodies (1:1000; ab190289, Abcam); rabbit anti-NF-κB p65 anti-bodies (1:1000; Ab16502, Abcam).

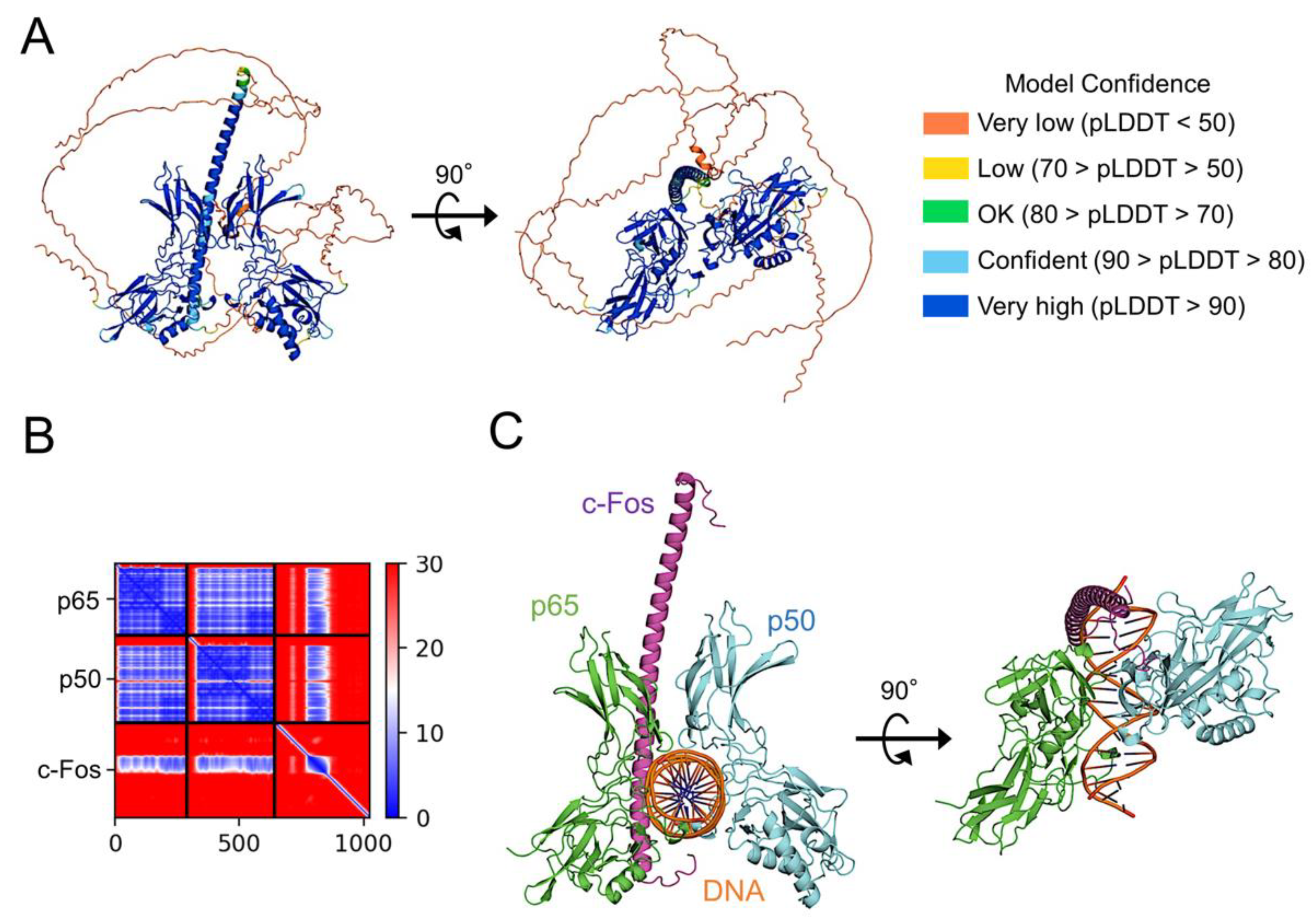

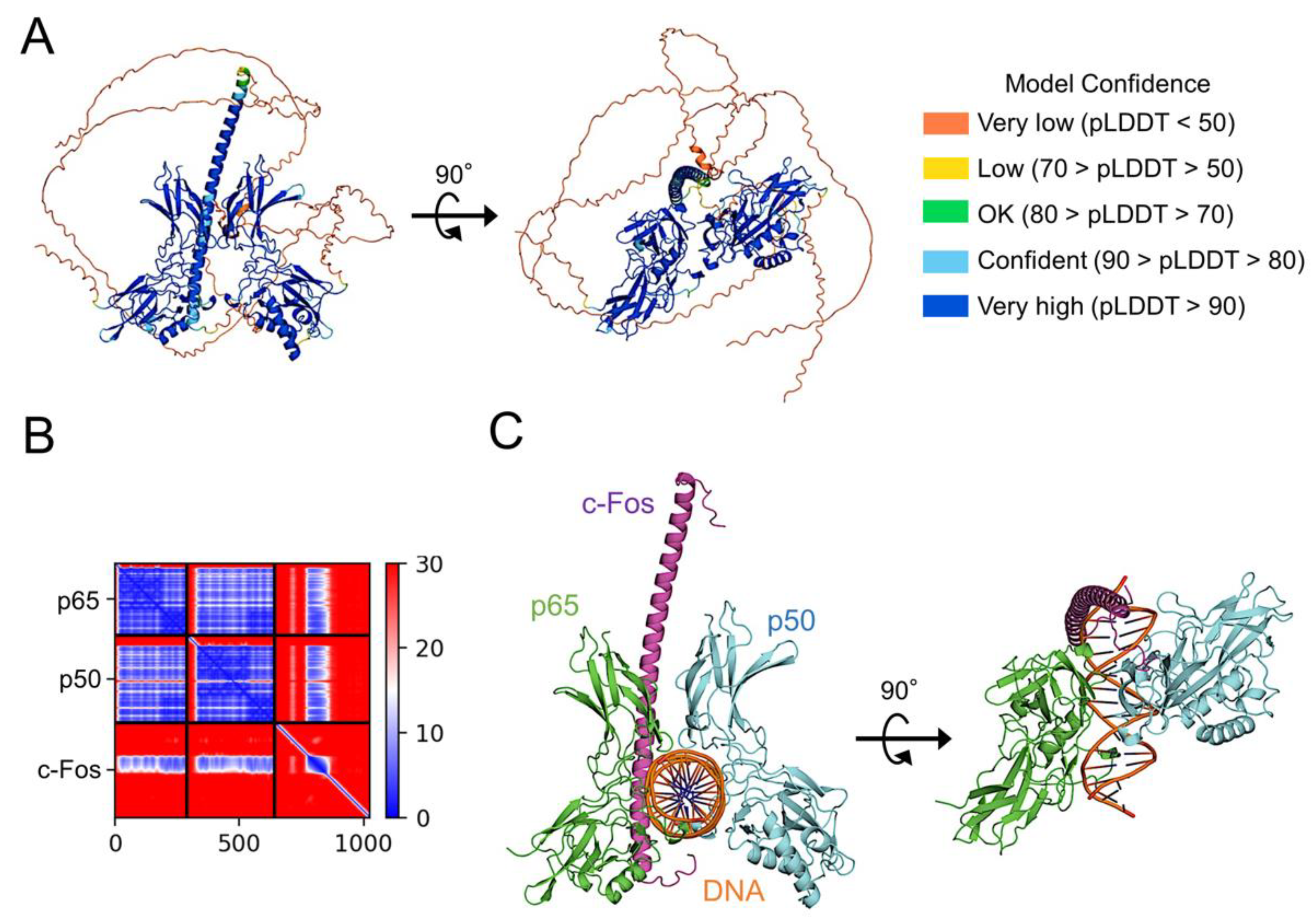

4.9. AlphaFold Predictions

The AlphaFold models of the ternary complex consisting of the DNA binding domain and dimerization domain of p65 (aa 1–291), those of p50 (aa 1–352), and full length of c-Fos were predicted using the AlphaFold v2.0 algorithm on the Co-lab server (

https://colab.research.google.com/github/sokrypton/ColabFold/blob/main/AlphaFold2. ipynb, accessed on November 20, 2023) [

40]. Predictions were performed with default multiple sequence alignment generation using the MMSeqs2 server, with 48 recycles and templates (homologous structures). The best of the five predicted models (rank 1) computed by AlphaFold was considered in the present work. The Structure of the complex consisting of p65, p50, c-Fos, and DNA was generated based on the AlphaFold model of p65:p50 hetero-dimer bound to leucine-zipper domain of c-Fos and the structure of DNA-bound p65:p50 heterodimer (PDB code 2I9T).

4.10. Statistical Analyses

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error (SE). The results were analyzed by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a post-hoc Tukey’s test using the GraphPad Prism8 (GraphPad Software, Inc., CA, USA) software package. P values of <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.N.; investigation, S.M. (Sakura Muramoto), S.S. (Sachi Shimizu), S.S. (Sumika Shirakawa), H.I., S.M. (Sayaka Miyamoto), M.J., U.T., C.M, E.I., K.O., and S.N.; analysis, S.M. (Sakura Muramoto), H.I., S.N., and H.N.; methodology and resources, Z.W., and H.T.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.N.; writing—review and editing, S.M. (Sakura Muramoto), S.S. (Sachi Shimizu), S.S. (Sumika Shirakawa), S.M. (Sayaka Miyamoto), M.J. H.I, O.K., S.N., and H.N.; and funding acquisition, H.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

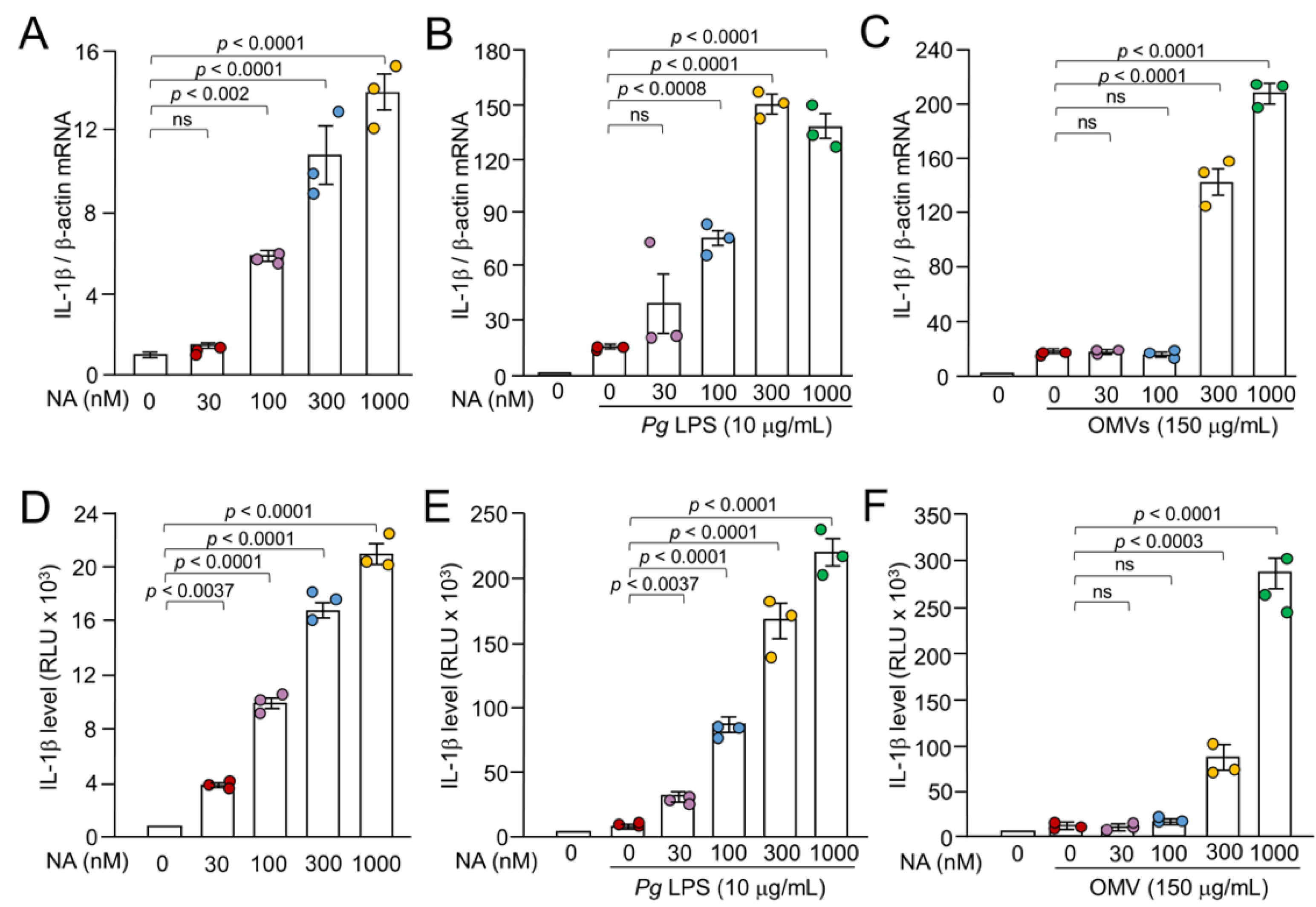

Figure 1.

Synergistic effects of NA on the Pg virulence factor-induced the expression of IL-1β by BV-2 microglia. (A-C) The mean relative level of IL-1β mRNA following treatment with NA, NA +Pg LPS and NA+OMVs for 1 h. (A) The mean relative level of IL-1β mRNA induced by NA with various concentrations (30-1000 nM). (B, C) The mean relative level of IL-1β mRNA induced by Pg LPS (10 μg/mL) (B) or OMVs (150 μg of protein/mL) (C) in the absence or presence of NA (30-1000 nM). D-F. The mean relative luciferase activity of the IL-1β probe following treatment with NA, NA+Pg LPS and NA+OMVs for 1h. (D) The mean relative luciferase activity of the IL-1β probe induced by NA with various concentrations (30-1000 nM). (E, F) The mean relative luciferase activity of the IL-1β probe induced by Pg LPS (10 μg/mL) (E) or OMVs (150 μg of protein/mL) (F) in the absence or presence of NA (30-1000 nM). Data relative to the values are presented as the mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments.

Figure 1.

Synergistic effects of NA on the Pg virulence factor-induced the expression of IL-1β by BV-2 microglia. (A-C) The mean relative level of IL-1β mRNA following treatment with NA, NA +Pg LPS and NA+OMVs for 1 h. (A) The mean relative level of IL-1β mRNA induced by NA with various concentrations (30-1000 nM). (B, C) The mean relative level of IL-1β mRNA induced by Pg LPS (10 μg/mL) (B) or OMVs (150 μg of protein/mL) (C) in the absence or presence of NA (30-1000 nM). D-F. The mean relative luciferase activity of the IL-1β probe following treatment with NA, NA+Pg LPS and NA+OMVs for 1h. (D) The mean relative luciferase activity of the IL-1β probe induced by NA with various concentrations (30-1000 nM). (E, F) The mean relative luciferase activity of the IL-1β probe induced by Pg LPS (10 μg/mL) (E) or OMVs (150 μg of protein/mL) (F) in the absence or presence of NA (30-1000 nM). Data relative to the values are presented as the mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments.

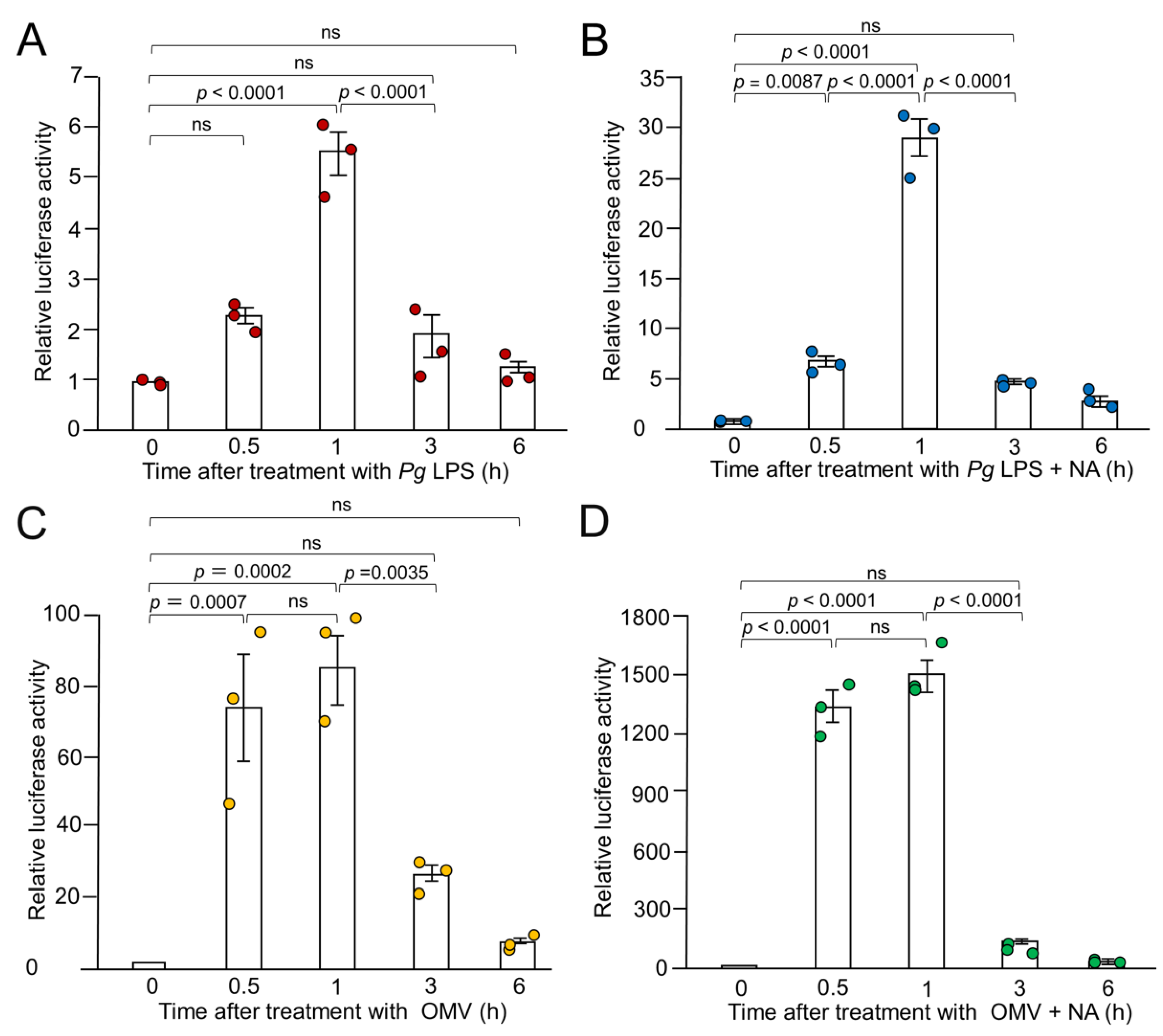

Figure 2.

Time course of the mean relative luciferase activity of the IL-1β probe induced by Pg LPS, OMVs and their combination with NA. (A, B) The mean relative luciferase activity of the IL-1β probe induced by either Pg LPS alone (10 μg/mL) (A)or combination with NA (1 μM) (B). (C, D) The mean relative luciferase activity of the IL-1β probe induced by either OMVs alone (150 μg of protein/mL) (C) or combination with NA (1 μM) (D). Data relative to the values are presented as the mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments.

Figure 2.

Time course of the mean relative luciferase activity of the IL-1β probe induced by Pg LPS, OMVs and their combination with NA. (A, B) The mean relative luciferase activity of the IL-1β probe induced by either Pg LPS alone (10 μg/mL) (A)or combination with NA (1 μM) (B). (C, D) The mean relative luciferase activity of the IL-1β probe induced by either OMVs alone (150 μg of protein/mL) (C) or combination with NA (1 μM) (D). Data relative to the values are presented as the mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments.

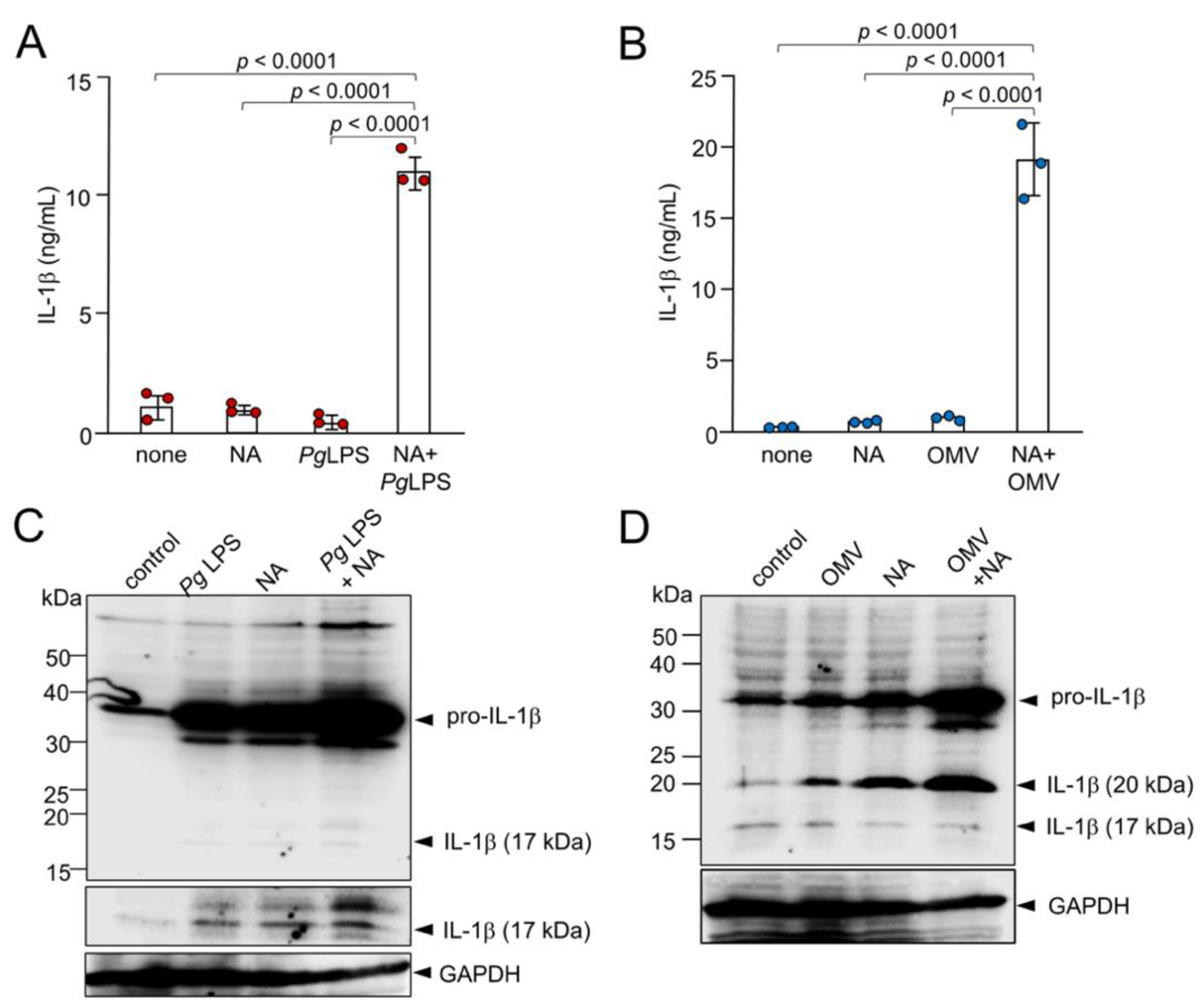

Figure 3.

Production of IL-1β by BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA, Pg virulence factors and their combination. (A) The mean concentration IL-1β in the cell lysates of BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA (1 μM), Pg LPS (10 μg/mL) and their combined application. (B) The mean concentration of IL-1β in the cell lysates of BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA (1 μM), OMVs (150 μg of protein/mL) and their combined application. Data are presented as the mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments. (C) Cell lysates from BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA (3 μM), Pg LPS (30 μg/mL) or their combined application for 1h were subjected to immunoblotting of IL-1β. (D) Cell lysates from BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA (3 μM), OMVs (150 μg of protein/mL) or their combined application for 1h were subjected to immunoblotting of IL-1β. Immunoblotting of GAPDH was used as a loading control.

Figure 3.

Production of IL-1β by BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA, Pg virulence factors and their combination. (A) The mean concentration IL-1β in the cell lysates of BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA (1 μM), Pg LPS (10 μg/mL) and their combined application. (B) The mean concentration of IL-1β in the cell lysates of BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA (1 μM), OMVs (150 μg of protein/mL) and their combined application. Data are presented as the mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments. (C) Cell lysates from BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA (3 μM), Pg LPS (30 μg/mL) or their combined application for 1h were subjected to immunoblotting of IL-1β. (D) Cell lysates from BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA (3 μM), OMVs (150 μg of protein/mL) or their combined application for 1h were subjected to immunoblotting of IL-1β. Immunoblotting of GAPDH was used as a loading control.

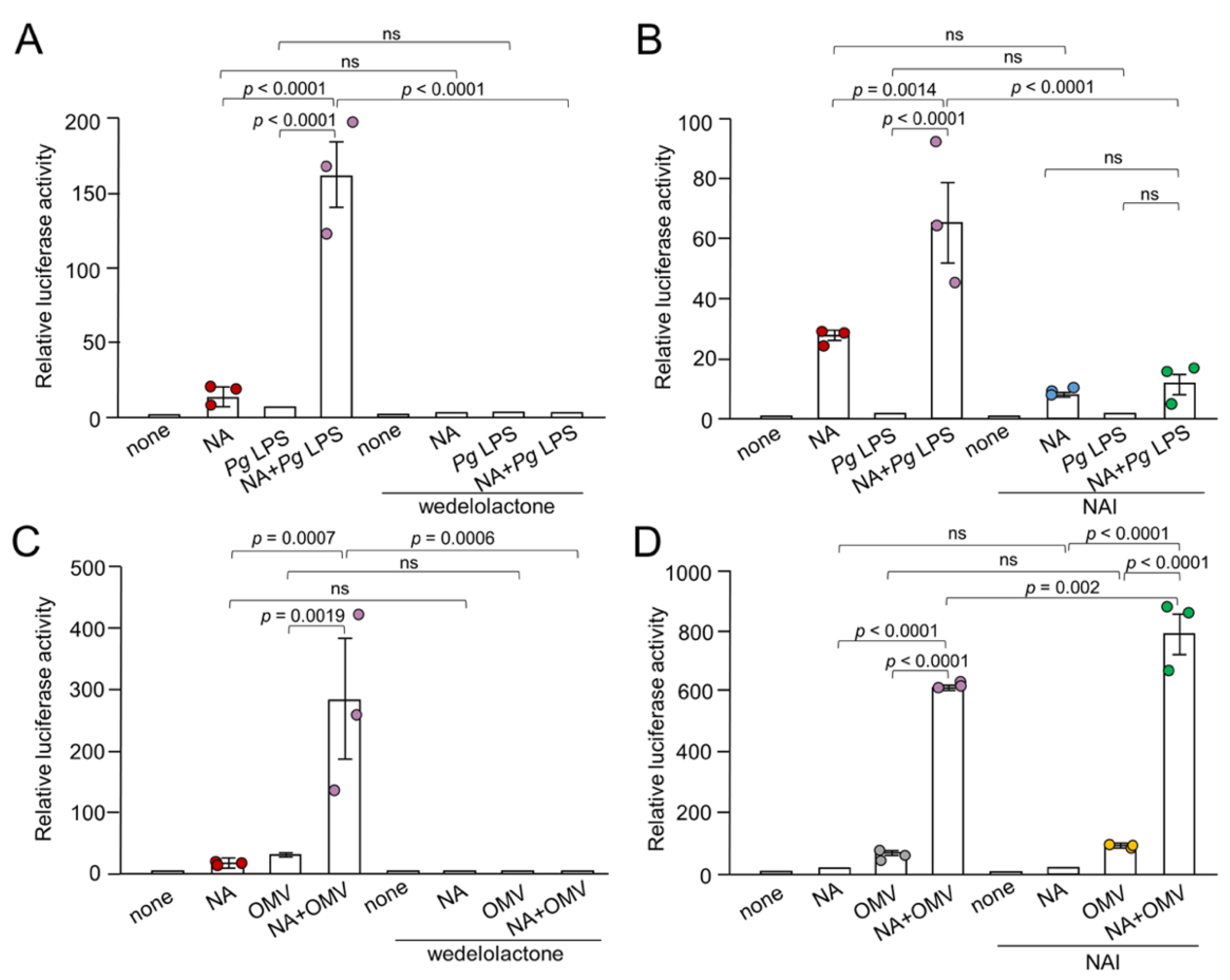

Figure 4.

Effects of NF-κB signaling pathway inhibitors on the production of IL-1β by BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA, Pg virulence factors and their combination. (A, B) The mean relative luciferase activity of the IL-1β probe induced by NA (1 μM), Pg LPS (10μg/mL) and their combined application in the absence or presence of wedelolactone (30 μM) (A) or NAI (100 nM) (B). (C, D) The mean relative luciferase activity of the IL-1β probe induced by NA (1 μM), OMVs (150 μg/mL) and their combined application in the absence or presence of wedelolactone (30μM) (C) or NAI (100 nM) (D). Data relative to the values are presented as the mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments.

Figure 4.

Effects of NF-κB signaling pathway inhibitors on the production of IL-1β by BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA, Pg virulence factors and their combination. (A, B) The mean relative luciferase activity of the IL-1β probe induced by NA (1 μM), Pg LPS (10μg/mL) and their combined application in the absence or presence of wedelolactone (30 μM) (A) or NAI (100 nM) (B). (C, D) The mean relative luciferase activity of the IL-1β probe induced by NA (1 μM), OMVs (150 μg/mL) and their combined application in the absence or presence of wedelolactone (30μM) (C) or NAI (100 nM) (D). Data relative to the values are presented as the mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments.

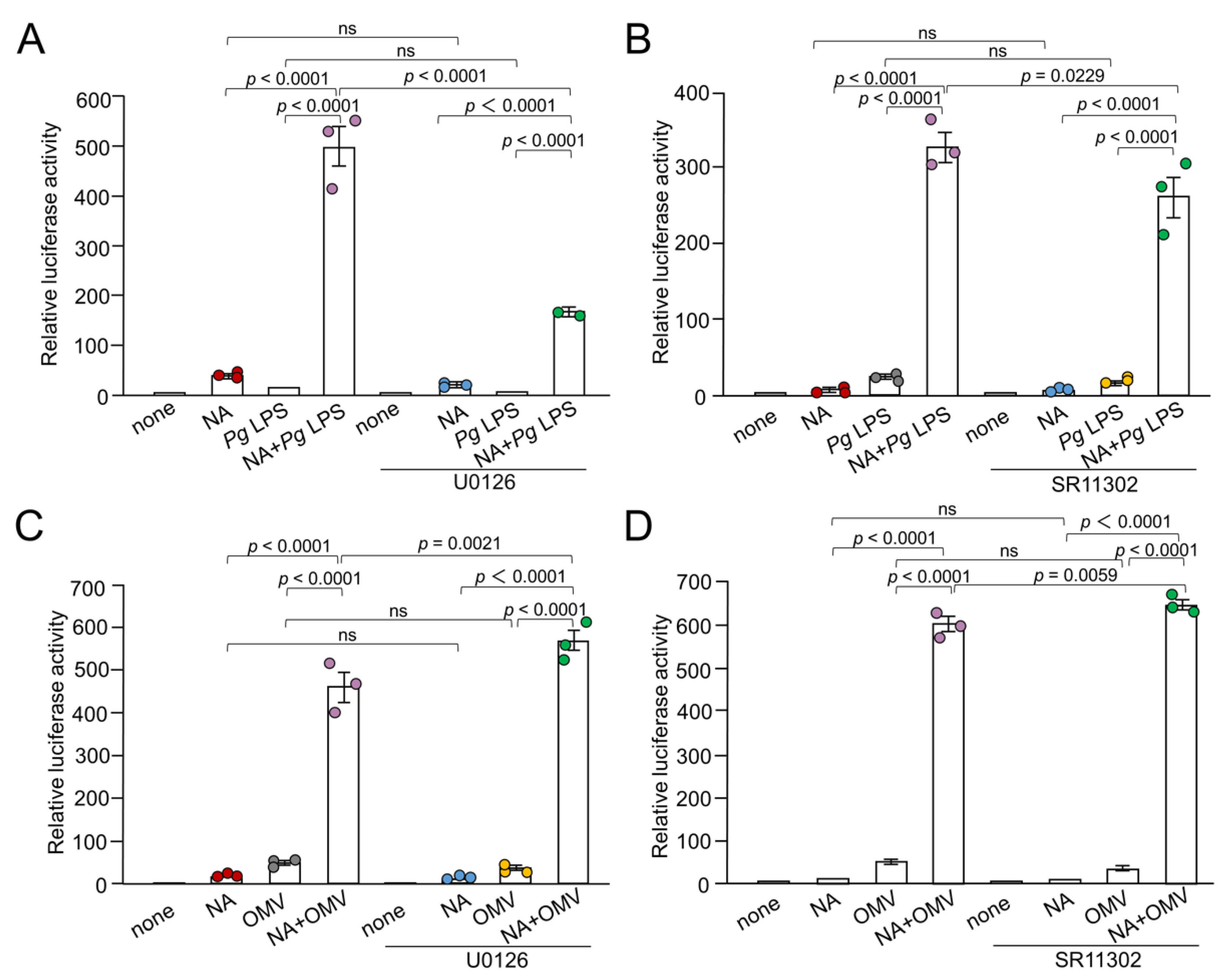

Figure 5.

Effects of AP-1 signaling pathway inhibitors on the production of IL-1β by BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA, Pg virulence factors and their combination. (A, B) The mean relative luciferase activity of the IL-1β probe induced by NA (1 μM), Pg LPS (10 μg/mL) and their combined application in the absence or presence of U0126 (15 μM) (A) or SR11302 (10 μM) (B). (C, D) The mean relative luciferase activity of the IL-1β probe induced by NA (1 μM), OMVs (150 μg of protein/mL) and their combined application in the absence or presence of U0126 (15 μM) (C) or SR11302 (10 μM) (D). Data relative to the values are presented as the mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments.

Figure 5.

Effects of AP-1 signaling pathway inhibitors on the production of IL-1β by BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA, Pg virulence factors and their combination. (A, B) The mean relative luciferase activity of the IL-1β probe induced by NA (1 μM), Pg LPS (10 μg/mL) and their combined application in the absence or presence of U0126 (15 μM) (A) or SR11302 (10 μM) (B). (C, D) The mean relative luciferase activity of the IL-1β probe induced by NA (1 μM), OMVs (150 μg of protein/mL) and their combined application in the absence or presence of U0126 (15 μM) (C) or SR11302 (10 μM) (D). Data relative to the values are presented as the mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments.

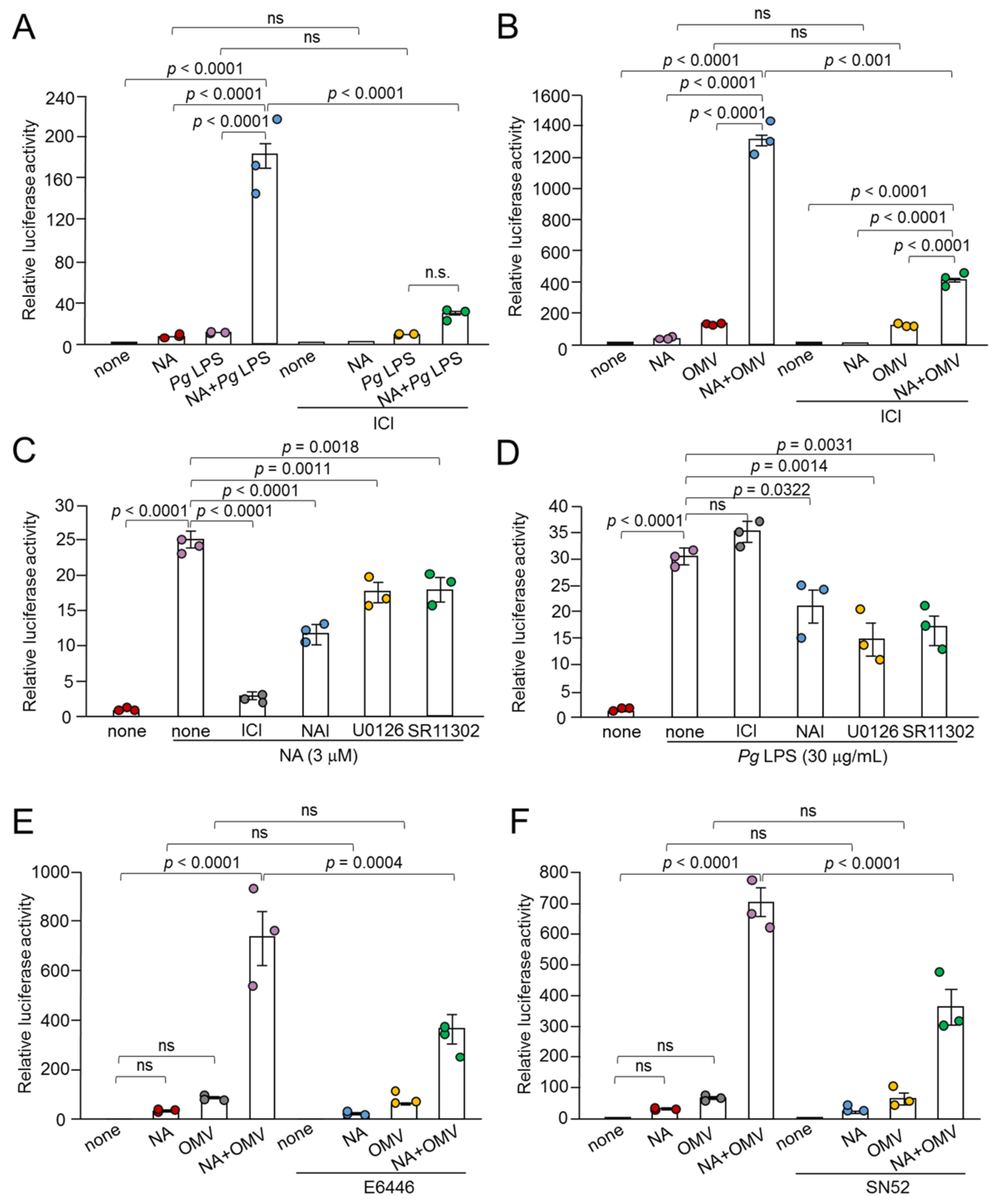

Figure 6.

Involvement of Aβ2R in the synergistic effect of NA and Pg virulence factors in the production of IL-1β by BV-2 microglia and effects of signaling inhibitors on the production of IL-1β induced by NA or Pg LPS alone. (A, B) Effects of ICI on the production of IL-1β by BV-2 microglia following stimulation of NA (1 μM) plus Pg LPS (10 μg/mL) or NA (1 μM) plus OMVs (150 μg/mL). (C, D) Effects of β2 ICI-118551 (0.1 μM), NAI (100 nM), U0126 (15 μM) and SR11302 (10 μM) on the production of IL-1β by BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA (3 μM) or Pg LPS (30 μg/mL). (E, F) Possible involvement of phagocytosis-related pathways on the production of IL-1β by BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA (1 μM) plus OMVs (150 μg/mL) was examined using the TLR9 inhibitor, E6446 (10 μM) (E) or the p52 inhibitor, SN52 (40 μg/mL) (F). Data relative to the values are presented as the mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments.

Figure 6.

Involvement of Aβ2R in the synergistic effect of NA and Pg virulence factors in the production of IL-1β by BV-2 microglia and effects of signaling inhibitors on the production of IL-1β induced by NA or Pg LPS alone. (A, B) Effects of ICI on the production of IL-1β by BV-2 microglia following stimulation of NA (1 μM) plus Pg LPS (10 μg/mL) or NA (1 μM) plus OMVs (150 μg/mL). (C, D) Effects of β2 ICI-118551 (0.1 μM), NAI (100 nM), U0126 (15 μM) and SR11302 (10 μM) on the production of IL-1β by BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA (3 μM) or Pg LPS (30 μg/mL). (E, F) Possible involvement of phagocytosis-related pathways on the production of IL-1β by BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA (1 μM) plus OMVs (150 μg/mL) was examined using the TLR9 inhibitor, E6446 (10 μM) (E) or the p52 inhibitor, SN52 (40 μg/mL) (F). Data relative to the values are presented as the mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments.

Figure 7.

Possible changes in expression levels and protein complex formation of p65 and c-Fos in BV-2 microglia following combined treatment with NA and Pg LPS. (A, B) Western blotting to analyze the protein levels of p65 (A) and c-Fos (B) in BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA and Pg LPS. (C, D) Co-immunoprecipitation combined with western blotting to analyze the interaction between p65 and c-Fos in BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA and Pg LPS. Co-immunoprecipitated samples using normal or anti-p65 IgG were subsequently subjected to western blotting using anti-p65 IgG (C) or anti-c-Fos IgG (D).

Figure 7.

Possible changes in expression levels and protein complex formation of p65 and c-Fos in BV-2 microglia following combined treatment with NA and Pg LPS. (A, B) Western blotting to analyze the protein levels of p65 (A) and c-Fos (B) in BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA and Pg LPS. (C, D) Co-immunoprecipitation combined with western blotting to analyze the interaction between p65 and c-Fos in BV-2 microglia following treatment with NA and Pg LPS. Co-immunoprecipitated samples using normal or anti-p65 IgG were subsequently subjected to western blotting using anti-p65 IgG (C) or anti-c-Fos IgG (D).

Figure 8.

Prediction of c-Fos binding to NF-

κB p65:p50 heterodimer. (

A) The structural model of c-Fos-bound NF-

κB p65:p50 heterodimer generated using AlphaFold2, presented as a ribbon colored in their pLDDT score. c-Fos binds to the molecular surface of p65. The figure to the right shows the complex structure vertically rotated by 90° from the figure to the left. (

B) PAE plots of the c-Fos and p65:p50 complex model. (

C) The structural model of the p65:p50:c-Fos complex forms a composite surface for DNA recognition. For the model construction, DNA bound to the p65:50 heterodimer (PDB code

2I9T) was bound to the AlphaFold2 model of the p65:p50:c-Fos complex. The long disordered regions in the

N-terminus and

C-terminus of c-Fos were removed from the figure to facilitate visualization. The NF-

κB of p65 and p50 are in green and light blue, respectively. c-Fos is in purple. The two DNA strands are in orange. The figure to the right shows the complex structure vertically rotated by 90° from the figure to the left. The figures were drawn using PyMOL [

41].

Figure 8.

Prediction of c-Fos binding to NF-

κB p65:p50 heterodimer. (

A) The structural model of c-Fos-bound NF-

κB p65:p50 heterodimer generated using AlphaFold2, presented as a ribbon colored in their pLDDT score. c-Fos binds to the molecular surface of p65. The figure to the right shows the complex structure vertically rotated by 90° from the figure to the left. (

B) PAE plots of the c-Fos and p65:p50 complex model. (

C) The structural model of the p65:p50:c-Fos complex forms a composite surface for DNA recognition. For the model construction, DNA bound to the p65:50 heterodimer (PDB code

2I9T) was bound to the AlphaFold2 model of the p65:p50:c-Fos complex. The long disordered regions in the

N-terminus and

C-terminus of c-Fos were removed from the figure to facilitate visualization. The NF-

κB of p65 and p50 are in green and light blue, respectively. c-Fos is in purple. The two DNA strands are in orange. The figure to the right shows the complex structure vertically rotated by 90° from the figure to the left. The figures were drawn using PyMOL [

41].