Submitted:

06 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Culture Conditions

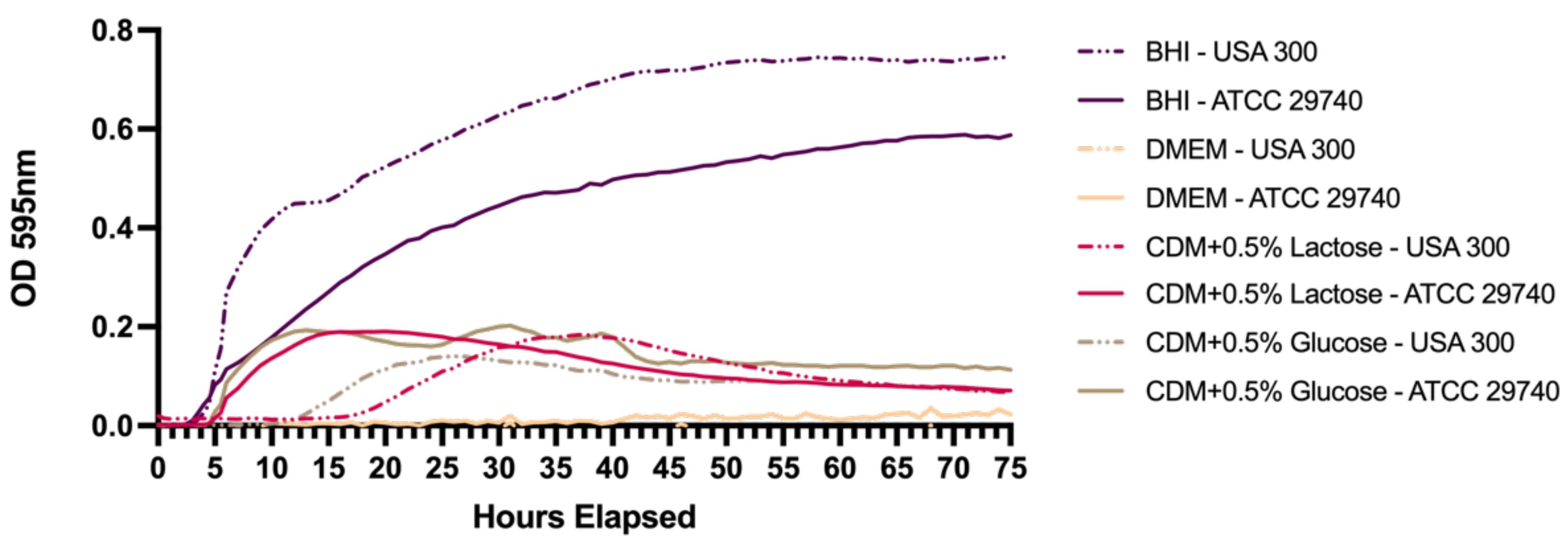

2.2. Growth Curves in Different Media

2.3. Nutritional Deprivation and Cell Enumeration

2.4. Quantitative PCR and ATP Assays

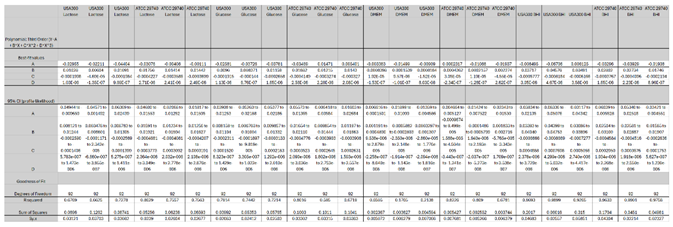

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Persistence Establishes within 72 Hours in Nutrient Deficient Conditions

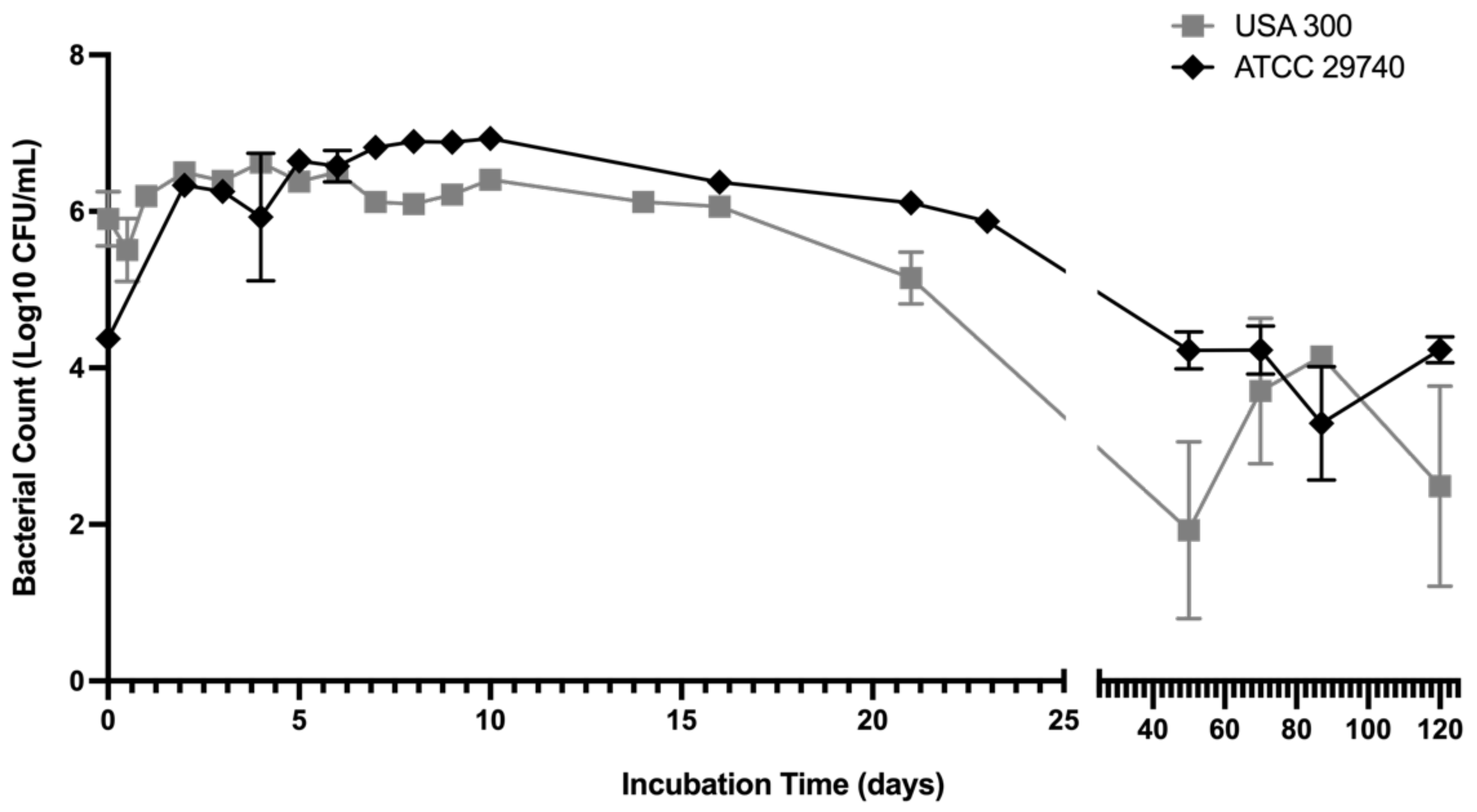

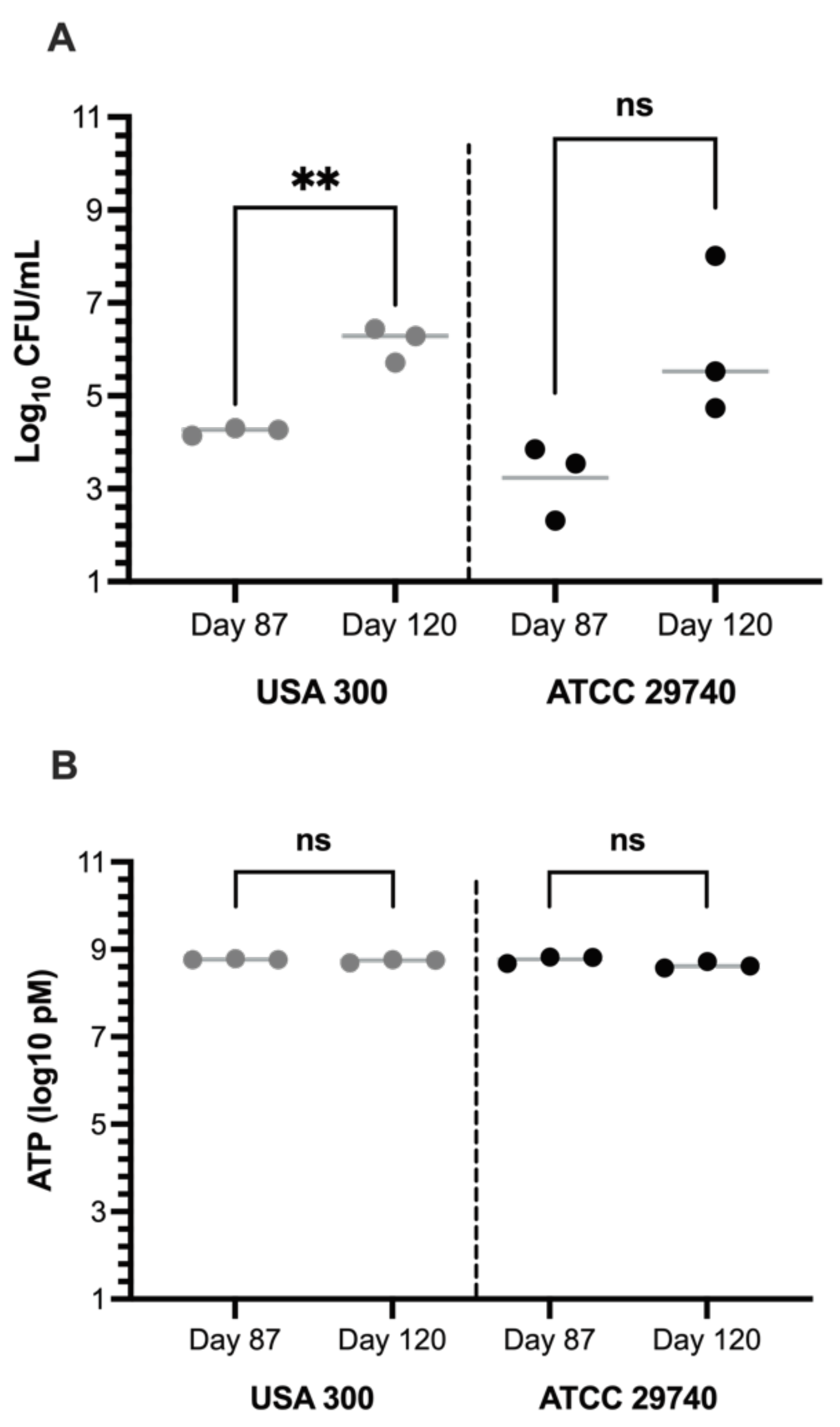

3.2. Persistence Continues for Over 120 Days When Challenged with Nutritional Stress and Induces Persister-Like Growth Patterns

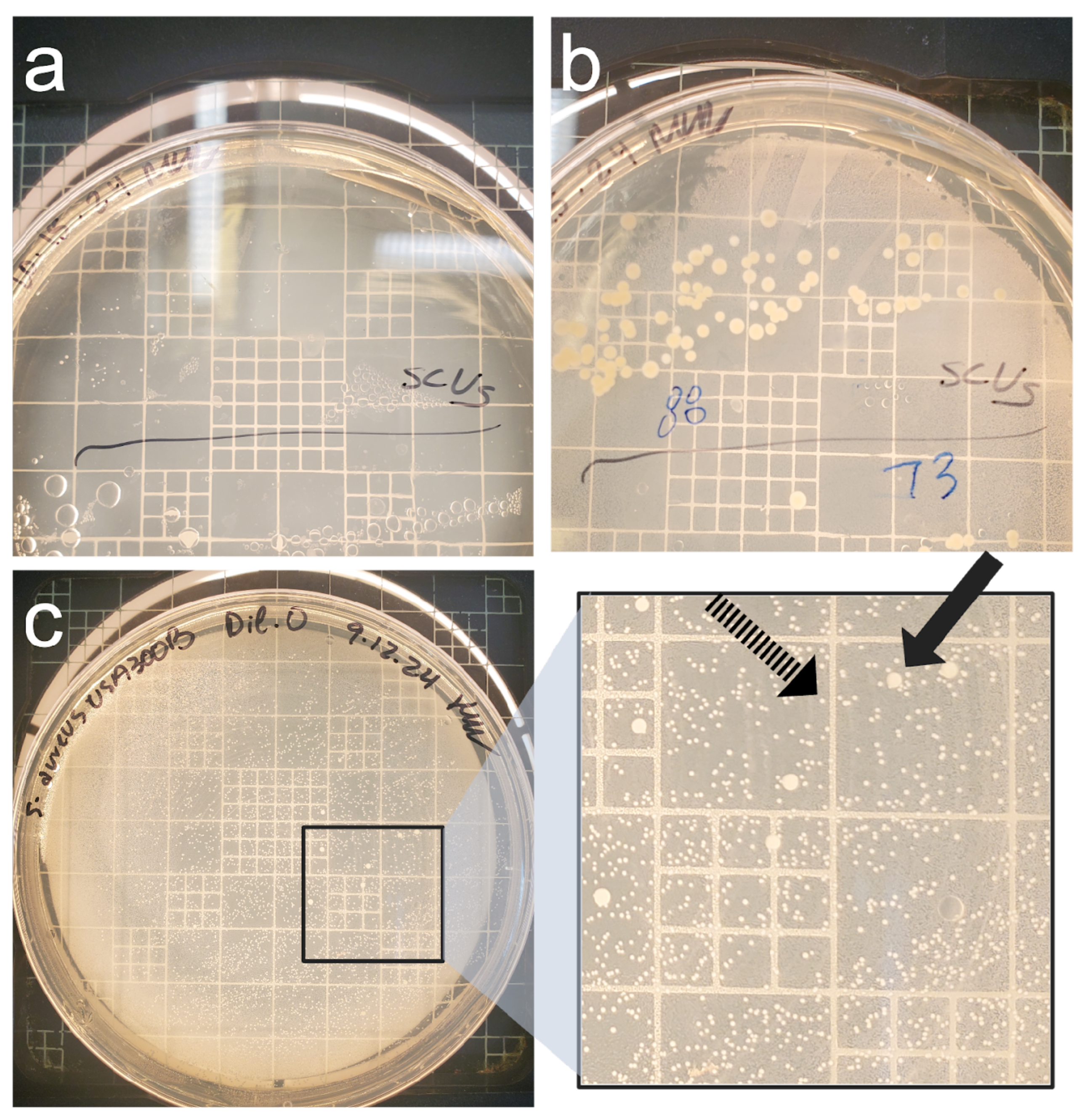

3.3. Culture-Based Methods of Detection Do Not Accurately Reflect Viability

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCV | Small Colony Variant |

Appendix A

| Between Strain | Lactose | 0.14370278 | |||

| Glucose | 0.684679703 | ||||

| DMEM | 0.902200382 | ||||

| BHI | 0.396304143 | ||||

| USA300 | Lactose | Glucose | DMEM | BHI | |

| Lactose | NA | ||||

| Glucose | 0.474397606 | NA | |||

| DMEM | 0.459986984 | 0.404311317 | NA | ||

| BHI | 0.275856074 | 0.171969557 | 0.648222506 | NA | |

| ATCC 29740 | Lactose | Glucose | DMEM | BHI | |

| Lactose | NA | ||||

| Glucose | 0.686956269 | NA | |||

| DMEM | 0.284479808 | 0.07761123 | NA | ||

| BHI | 0.07761123 | 0.158564251 | 0.372151583 | NA |

References

- Lowy, F.D. Staphylococcus aureus Infections. New England Journal of Medicine 1998, 339, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peton, V.; le Loir, Y. Staphylococcus aureus in Veterinary Medicine. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2014, 21, 602–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peres, A.G.; Madrenas, J. The broad landscape of immune interactions with Staphylococcus aureus: From commensalism to lethal infections. Burns 2013, 39, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnanamani, A.; Hariharan, P.; Paul- Satyaseela, M.; Gnanamani, A.; Hariharan, P.; Paul- Satyaseela, M. Staphylococcus aureus: Overview of Bacteriology, Clinical Diseases, Epidemiology, Antibiotic Resistance and Therapeutic Approach. Frontiers in Staphylococcus aureus 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.L.; Cabezudo, I.; Wenzel, R.P. Epidemiology of Nosocomial Infections Caused by Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Ann Intern Med 1982, 97, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.K.; Garg, R.; Baliga, S.; Bhat, K.G. Nosocomial Infections and Drug Susceptibility Patterns in Methicillin Sensitive and Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Diagn Res 2013, 7, 2178–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, M.; Wozniak, D.J.; Stoodley, P.; Hall-Stoodley, L. Prevention and treatment of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy 2015, 13, 1499–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, B.; Pickering, A.C.; Rocha, L.L.; Aguilar, A.P.; Fabres-Klein, M.H.; Mendes, T.A.D.O.; Fitzgerald, J.R.; Ribon, A.D.O.B. Diversity and pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus from bovine mastitis: Current understanding and future perspectives. BioMed Central 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haag, A.F.; Fitzgerald, J.R.; Penadés, J.R. Staphylococcus aureus in Animals. Microbiol Spectr 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangra, S.; Khunger, S.; Chattopadhya, D. Antimicrobial Resistance in Staphylococci Special Emphasis on Methicillin Resistance among Companion Livestock and Its Impact on Human Health in Rural India. IntechOpen 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Ronholm, J. Staphylococcus aureus in Agriculture: Lessons in Evolution from a Multispecies Pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 2021, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, F.C.; Markey, B.K. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in animals: A Review. The Veterinary Journal 2008, 175, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parastan, R.; Kargar, M.; Solhjoo, K.; Kafilzadeh, F. Staphylococcus aureus biofilms: Structures, antibiotic resistance, inhibition, and vaccines. Gene Reports 2020, 20, 100739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantosti, A.; Sanchini, A.; Monaco, M. Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance in Staphylococcus Aureus. Future Microbiology 2007, 2, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, P.C. Microbiology of Antibiotic Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2007, 45, S165–S170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, H.F.; Deleo, F.R. Waves of resistance: Staphylococcus aureus in the antibiotic era. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howden, B.P.; Giulieri, S.G.; Wong Fok Lung, T.; Baines, S.L.; Sharkey, L.K.; Lee, J.Y.H.; Hachani, A.; Monk, I.R.; Stinear, T.P. Staphylococcus aureus Host Interactions and Adaptation. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21, 380–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinges, M.M.; Orwin, P.M.; Schlievert, P.M. Exotoxins of Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Microbiol Rev 2000, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conlon, B.P. Staphylococcus aureus chronic and relapsing infections: Evidence of a role for Persister Cells. BioEssays 2014, 36, 991–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Lee, R.E.; Lee, W. A pursuit of Staphylococcus aureus continues: A role of persister cells. Arch. Pharm. Res 2020, 43, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, K. Persister Cells: Molecular Mechanisms Related to Antibiotic Tolerance. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology 2012, 211, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, R.; von Eiff, C.; Kahl, B.; Becker, K.; McNamara, P.; Merrmann, M.; Peters, G. Small colony variants: A pathogenic form of bacteria that facilitates persistent and recurrent infections. Nat Rev Microbiol 2006, 4, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, R.A.; Kriegeskorte, A.; Kahl, B.C.; Becker, K.; Löffler, B.; Peters, G. Staphylococcus aureus Small Colony Variants (SCVs): A road map for the metabolic pathways involved in persistent infections. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuchscherr, L.; Heitmann, V.; Hussain, M.; Viemann, D.; Roth, J.; von Eiff, C.; Peters, G.; Becker, K.; Löffler, B. Staphylococcus aureus Small-Colony Variants Are Adapted Phenotypes for Intracellular Persistence. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2010, 202, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuchscherr, L.; Medina, E.; Hussain, M.; Völker, W.; Heitmann, V.; Niemann, S.; Holzinger, D.; Roth, J.; Proctor, R.A.; Becker, K.; Peters, G.; Löffler, B. Staphylococcus aureus phenotype switching: An effective bacterial strategy to escape host immune response and establish a chronic infection. EMBO Mol Med 2011, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, K. Detection, Identification and Diagnostic Characterization of the Staphylococcal Small Colony-Variant (SCV) Phenotype. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, S.E.; Beam, J.E.; Conlon, B.P. Recalcitrant Staphylococcus aureus Infections: Obstacles and Solutions. Infect Immun 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaatout, N.; Ayachi, A.; Kecha, M. Staphylococcus aureus persistence properties associated with bovine mastitis and alternative therapeutic modalities. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2020, 129, 1102–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.-Q.; Liu, Z.-Z.; Zhou, C.-K.; Zhang, L.; Gao, Y.; Luo, X.-Y.; Zhang, J.-G.; Chen, W.; Yang, Y.-J. Trained immunity in recurrent Staphylococcus aureus infection promotes bacterial persistence. PLoS Pathog 2024, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Oh, D.H.; Broadbent, J.R.; Johnson, M.E.; Weimer, B.C.; Steele, J.L. Aromatic amino acid catabolism by lactococci. Lait 1997, 77, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, C.; Weimer, B.C.; Gann, R.; Desai, P.T.; Shah, J.D. The Yin and Yang of pathogens and probiotics: Interplay between Salmonella enterica sv. Typhimurium and Bifidobacterium infantis during co-infection. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabyan, N.; Park, D.; Foutouhi, S.; et al. Salmonella Degrades the Host Glycocalyx Leading to Altered Infection and Glycan Remodeling. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 29525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smug, B. J.; Opalek, M.; Necki, M.; Wloch-Salamon, D. Microbial lag calculator: A shiny-based application and an R package for calculating the duration of microbial lag phase. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2023, 15, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, E.J.; Bacigalupe, R.; Harrison, E.M.; et al. Gene exchange drives the ecological success of a multi-host bacterial pathogen. Nat Ecol Evol 2018, 2, 1468–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stülke, J.; Hillen, W. Carbon catabolite repression in bacteria. Current Opinion in Microbiology 1999, 2(2), 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, S.P.; Clements, M.O.; Foster, S.J. Characterization of the Starvation-Survival Response of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 1998, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyango, L.A.; Alreshidi, M.M. Adaptive metabolism in staphylococci: Survival and persistence in environmental and clinical settings. J Patho. 2018, 2018, 1092632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassat, J.E.; Skaar, E.P. Metal ion acquisition in Staphylococcus aureus: Overcoming nutritional immunity. Semin Immunopathol 2012, 34, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, J.; Hobbs, G.; Nakouti, I. Persister cells: Formation, resuscitation and combative therapies. Arch Microbiol 2021, 203, 5899–5906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiff, C.V. Staphylococcus aureus small colony variants: A challenge to microbiologists and clinicians. Elsevier BV 2008, 31, 507–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Zilm, P.S.; Kidd, S.P. Novel Research Models for Staphylococcus aureus Small Colony Variants (SCV) Development: Co-pathogenesis and Growth Rate. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foddai, A.C.G.; Grant, I.R. Methods for detection of viable foodborne pathogens: Current state-of-art and future prospects. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2020, 104, 4281–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, K. Detection, Identification and Diagnostic Characterization of the Staphylococcal Small Colony-Variant (SCV) Phenotype. Antibiotics (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riss, T. L.; Moravec, R. A.; Niles, A. L.; Duellman, S.; Benink, H. A.; Worzella, T. J.; Minor, L. Cell viability assays. In Assay guidance manual, 2016.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).