Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

08 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Related Concepts

2.2. Related Research

3. Initial Scale Construction

3.1. Information Ecology Theory

3.2. Data Sources and Data Collection

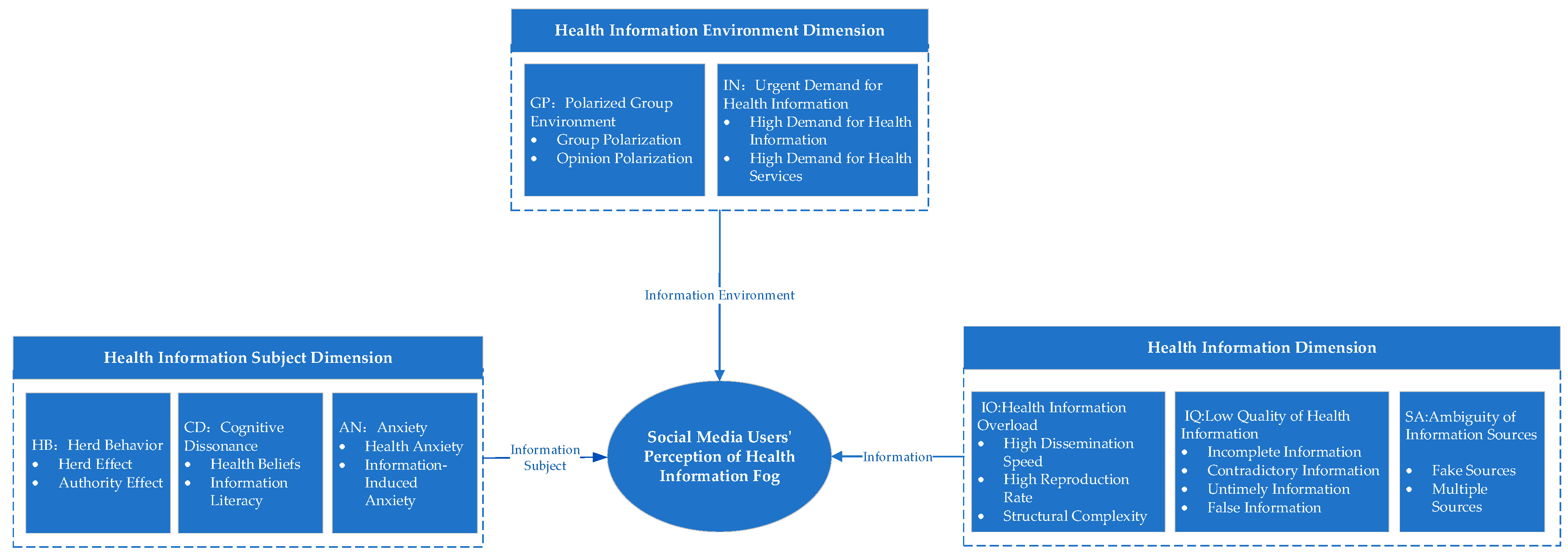

3.3. Definition of Concepts and Determination of Dimensions

3.4. Data Sources and Data Collection

4. Scale Validation

4.1. Preliminary Research and Scale Revision

4.2. Formal Survey and Scale Validation

4.2.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

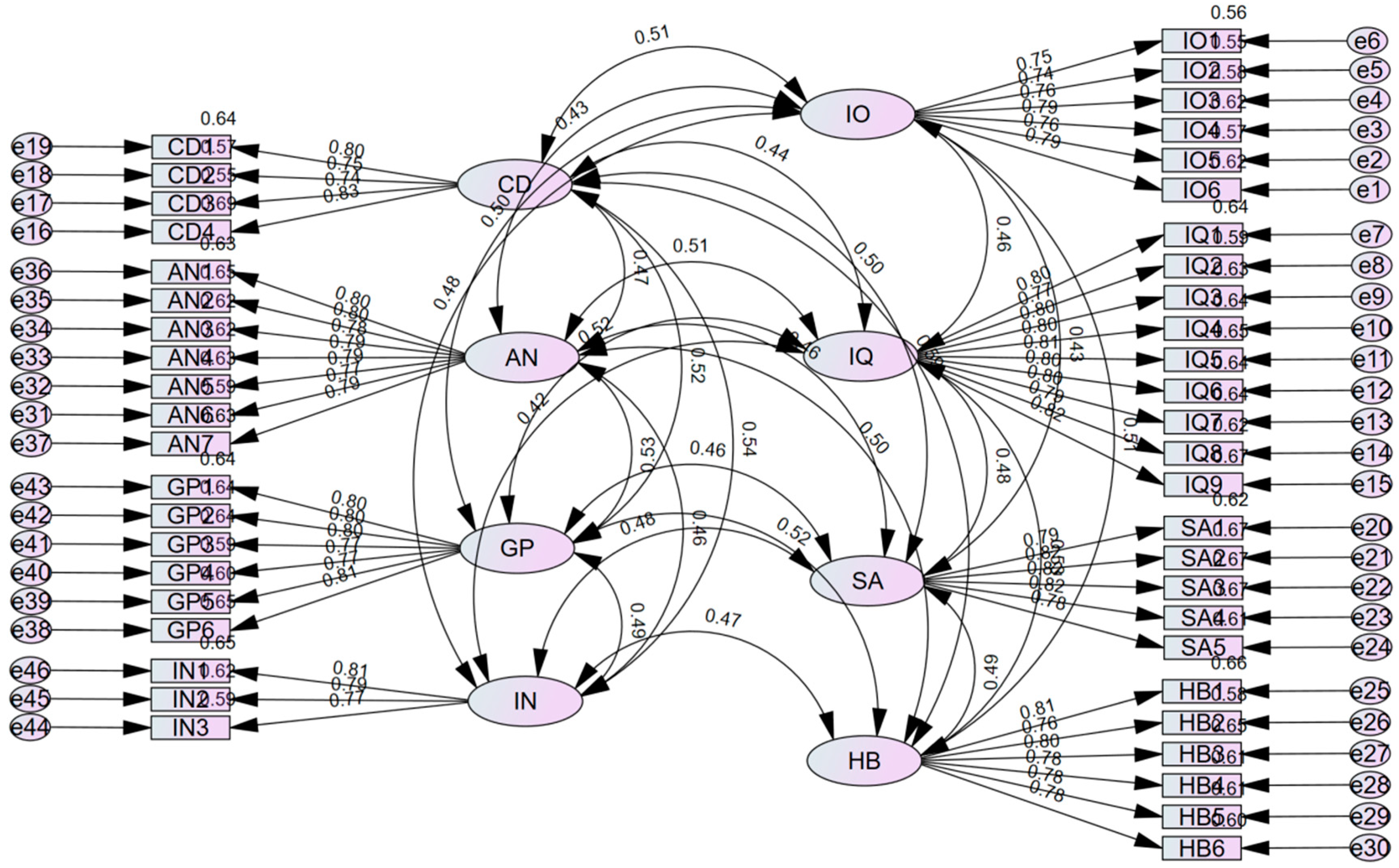

4.2.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.2.3. Categorization of Social Media Users' Perception of Health Information Ambiguity

- Low: Less than P10

- Relatively Low: ≥P10 and ≤P30

- Average: >P30 and ≤P70

- Relatively High: >P70 and ≤P90

- High: Greater than P90

5. Conclusion and Prospect

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Powell, J.; Pring, T. The impact of social media influencers on health outcomes: Systematic review. Social Science & Medicine 2024, 340, 116472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stimpson, J.P.; Ortega, A.N. Social media users’ perceptions about health mis- and disinformation on social media. Health Affairs Scholar 2023, 1, qxad050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neely, S.R.; Eldredge, C.E.; Sanders, R. Health Information Seeking Behaviors on Social Media During the COVID-19 Pandemic Among American Social Networking Site Users: Survey Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, G.; Hendlin, Y.; Desikan, A.; et al. The disinformation playbook: how industry manipulates the science-policy process—and how to restore scientific integrity. Journal of Public Health Policy 2021, 42, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ireton, C.; Posetti, J. Journalism, Fake News & Disinformation: Handbook for Journalism Education and Training. UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2018.

- Zhihui, P. On the Integration, Transformation, and Reinterpretation of the Concept of Disinformation in the Chinese Context. Information Theory and Practice 2022, 45, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aïmeur, E.; Amri, S.; Brassard, G. Fake news, disinformation and misinformation in social media: a review. Social Network Analysis and Mining 2023, 13, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisondi, M.A.; Barber, R.; Faust, J.S.; et al. A Deadly Infodemic: Social Media and the Power of COVID-19 Misinformation. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e35552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pian, W.; Chi, J.; Ma, F. The causes, impacts and countermeasures of COVID-19 “Infodemic”: A systematic review using narrative synthesis. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021, 58, 102713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, D.R. Health disinformation & social media: The crucial role of information hygiene in mitigating conspiracy theory and infodemics. EMBO Rep. 2020, 21, e51819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotez, P.J. Health Disinformation—Gaining Strength, Becoming Infinite. JAMA Intern. Med. 2024, 184, 96–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstra, L.; Gommers, D. How can doctors counter health misinformation on social media? BMJ 2023, 382, p1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marar, S.D.; Al-Madaney, M.M.; Almousawi, F.H. Health information on social media.Perceptions, attitudes, and practices of patients and their companions. Saudi Med. J. 2019, 40, 1294–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Costa, M.-P.; López-Pan, F.; Buslón, N.; et al. Nobody-fools-me perception: Influence of Age and Education on Overconfidence About Spotting Disinformation. Journal. Pract. 2023, 17, 2084–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.L.; Huang, L.V. Digital Disinformation About COVID-19 and the Third-Person Effect: Examining the Channel Differences and Negative Emotional Outcomes. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, R.; Srivastava, A.; Ningthoujam, G.D.; Potsangbam, T.; Oinam, A.; Anal, C.L. An Observational Study in Manipur State, India on Preventive Behavior Influenced by Social Media During the COVID-19 Pandemic Mediated by Cyberchondria and Information Overload. J. Prev. Med. Public Health . 2021, 54, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, R.; Green, H.; Hobbs, C.; Loveday, C.; Almasi, E.; Middleton, R.; Halcomb, E.J.; Moxham, L. Adaption of the Cancer Information Overload Scale for pandemics and assessment of infodemic levels among nurses and midwives. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2022, 29, e13055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.D.; Carcioppolo, N.; King, A.J.; Bernat, J.K.; Davis, L.A.; Yale, R.; Smith, J. The cancer information overload (CIO) scale: Establishing predictive and discriminant validity. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 94, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, A.; Soós, S.; Tompa, O.; Révész, L.; Tóth, L.P.; Szabó, A. Measuring Athletes’ Perception of the Sport Nutrition Information Environment: The Adaptation and Validation of the Diet Information Overload Scale among Elite Athletes. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Xie, T. Social Media Overload and Anxiety Among University Students During the COVID-19 Omicron Wave Lockdown: A Cross-Sectional Study in Shanghai, China,2022. Int.J. Public Health. 2023, 67, 1605363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimah, R.N.; Kusnanto, H.; Lazuardi, L. Development of the information quality scale for health information supply chain type 2 diabetes mellitus management using exploratory factor analysis. Journal of Public Health Research 2023, 12, 22799036231170843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadahunsi, K.P.; Wark, P.; Mastellos, N.; et al. Assessment of Clinical Information Quality in Digital Health Technologies: International eDelphi Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2022, 24, e41889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stimpson, J.P.; Ortega, A.N. Social media users’ perceptions about health mis- and disinformation on social media. Health Affairs Scholar 2023, 1, qxad050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, B.; Oh, S. College Students’ Perceived Credibility of Health Information on YouTube. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology 2023, 60, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Li, W.; Xin, X.; et al. Strategies for Assessing Health Information Credibility Among Older Social Media Users in China: A Qualitative Study. Health Communication 2023, 39, 2767–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagler, R.H.; Vogel, R.; Gollust, S.E.; Yzer, M.C.; Rothman, A.J. Effects of Prior Exposure to Conflicting Health Information on Responses to Subsequent Unrelated Health Messages: Results from a Population-Based Longitudinal Experiment. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 2021, 56, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; Zhang, B. Determinants of the Perceived Credibility of Rebuttals Concerning Health Misinformation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Chen, G.; Yang, C. How cognitive conflict affects judgments of learning: Evaluating the contributions of processing fluency and metamemory beliefs. Memory & Cognition 2021, 49, 912–922. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas, D.R.Z.; Jaldin, M.L.L.; Canaviri, B.N.; et al. Social media exposure, risk perception, preventive behaviors and attitudes during the COVID-19 epidemic in La Paz, Bolivia: A cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE, 2021, 16, e0245859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Li, Z.; Yu, Z.; He, L.; Zhou, J. Communication related health crisis on social media: a case of COVID-19 outbreak. Current Issues in Tourism 2021, 24, 2699–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. (Thomas); Tham, J.S.; Waheed, M. The Effects of Receiving and Expressing Health Information on Social Media during the COVID-19 Infodemic: An Online Survey among Malaysians. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 7991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrage, M. Information Ecology: Mastering the Information and Knowledge Environment. Harvard Business Review 1997, 75, 185–189. [Google Scholar]

- Usinowicz, J.; O’Connor, M.I. The fitness value of ecological information in a variable world. Ecology Letters 2023, 26, 621–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KAWO. 2023 China Social Media Platform Guide. Social Media Report, 2023. Available online: https://www.sgpjbg.com/baogao/122692.html.

- Rajesh, M.A.; Hiwarkar, D.T. Exploring Preprocessing Techniques for Natural Language Text: A Comprehensive Study Using Python Code. International Journal of Engineering Technology and Management Sciences, 2023, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Shang, R.-A.; Kao, C.-Y. The effects of information overload on consumers’ subjective state towards buying decision in the internet shopping environment. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 2009, 8, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallavi, P.; Bakhla, A.; Kisku, R.R.; et al. Excessive and Unreliable Health Information and Its Predictability for Anxiety: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Cureus 2022, 14, e27149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W. Health Information Seeking versus Avoiding: How Do College Students Respond to Stress-related Information? American Journal of Health Behavior 2019, 43, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, L.; Lu, Y.; et al. Do you get tired of socializing? An empirical explanation of discontinuous usage behaviour in social network services. Information & Management 2016, 53, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Li, J.; Qin, N.; et al. Examining the Effect of Overload on the MHealth Application Resistance Behavior of Elderly Users: An SOR Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 6658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afful-Dadzie, E.; Afful-Dadzie, A.; Egala, S.B. Social media in health communication: A literature review of information quality. Health Information Management Journal 2021, 52, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebesin, F.; Smuts, H.; Mawela, T.; et al. The Role of Social Media in Health Misinformation and Disinformation During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Bibliometric Analysis. JMIR Infodemiology 2023, 3, e48620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Xie, B. Quality of health information for consumers on the web: A systematic review of indicators, criteria, tools, and evaluation results. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 2015, 66, 2071–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A.; Sanford, C. Influence Processes for Information Technology Acceptance: An Elaboration Likelihood Model. MIS Quarterly 2006, 30, 805–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; Zhang, B. Determinants of the Perceived Credibility of Rebuttals Concerning Health Misinformation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laugesen, J.; Hassanein, K.; Yuan, Y. The Impact of Internet Health Information on Patient Compliance: A Research Model and an Empirical Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2015, 17, e143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, X.; Chen, M.; Guan, X. How Should the Medical Community Respond to the Low Quality of Medical Information on Social Media? European Urology Open Science 2021, 24, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmer, N. Questioning reliability assessments of health information on social media. Journal of the Medical Library Association 2017, 105, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.C.S.; Wang, Y. The influences of electronic word-of-mouth message appeal and message source credibility on brand attitude. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 2011, 23, 448–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaoguang, H.; Feicheng, M.; Yifei, Q.; et al. Exploring the determinants of health knowledge adoption in social media: An intention-behavior-gap perspective. Information Development 2018, 34, 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-I.; Jin, Y. Crisis Information Seeking and Sharing (CISS): Scale Development for Measuring Publics’ Communicative Behavior in Social-Mediated Public Health Crises. Journal of International Crisis and Risk Communication Research 2019, 2, 13–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasmari, H.; Zavalina, O.L. Using Two Theories in Exploration of the Health Information Diffusion on Social Media During a Global Health Crisis. Journal of 2023, 5, 2250095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.-H.; Wang, Y.-S.; Tang, T.-I. Exploring the determinants of knowledge adoption in virtual communities: A social influence perspective. International Journal of Information Management, 2015, 35, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Yang, B.; Wang, X.; et al. On the dimensionality of intragroup conflict: An exploratory study of conflict and its relationship with group innovation performance. International Journal of Conflict Management 2017, 28, 538–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagler, R.H.; Vogel, R.I.; Gollust, S.E.; et al. Public perceptions of conflicting information surrounding COVID-19: Results from a nationally representative survey of U.S. adults. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0240776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tocalli-Beller, A. Cognitive Conflict, Disagreement and Repetition in Collaborative Groups: Affective and Social Dimensions from an Insider’s Perspective. Canadian Modern Language Review 2003, 60, 143–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilowsky, I. Dimensions of Hypochondriasis. The British Journal of Psychiatry 1967, 113, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salkovskis, P.; Rimes, K.; Warwick, H.; Clark, D.M. The Health Anxiety Inventory: Development and Validation of Scales for the Measurement of Health Anxiety and Hypochondriasis. Psychological Medicine 2002, 32, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahai, F. The Stress Factor of Social Media. Aesthetic Surgery Journal 2018, 38, 689–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attribute | Category | Number of Respondents | Attribute | Category | Number of Respondents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 16 | Occupation | Retired | 8 |

| Female | 19 | Student | 12 | ||

| Age | 18-25 years old | 5 | Corporate Employee | 12 | |

| 26-35 years old | 8 | Other | 3 | ||

| 36-45 years old | 11 | Registration Time | < 0.5 years | 2 | |

| >46 | 11 | 0.5-1 year | 4 | ||

| Education | Associate Degree or Below | 18 | 1-3 years | 16 | |

| Bachelor's | 10 | 3-5 years | 10 | ||

| Master's and Above | 7 | > 5 years | 3 | ||

| Social Media Source | WeChat Video Accounts | 10 | Health Info Browsing Frequency | Rarely (Seasonally) | 2 |

| Douyin | 16 | Occasionally (Monthly) | 5 | ||

| Kuaishou | 9 | Often (Weekly) | 15 | ||

| Always (Daily) | 13 |

| Information Ecology Factor |

Main Theme |

Initial Category |

Typical Evidence Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Information |

Health Information Overload | Information spreads rapidly, reproduction is fast, and hierarchical structure is complex | "On social media platforms, I find that health information spreads very quickly. Everyone is forwarding and commenting, and within minutes, there are hundreds of responses." |

| Low Quality of Health Information | Information lacks timeliness, updates are relatively slow, and accuracy is questionable. Some information is incomplete, and outdated information continues to circulate | "I often see some health information, but it’s hard to judge whether it’s real. Sometimes, I feel the information lacks integrity; some outdated information is still being spread." | |

| Ambiguity of Information Sources | Claims of authority from experts or institutions are false, and sources are difficult to identify | "Many people online claim to be authoritative experts posting health information, but later I realized they were not credible. Sometimes, it’s hard to identify where the forwarded information originates." | |

|

Information Subjects |

Blind Conformity Among Health Information Disseminators | Herd effect, authority effect | "I see everyone forwarding certain health information, and I think it must be correct, so I forward it as well. Some people forward information because they believe it comes from an authoritative source." |

| Cognitive Dissonance Among Health Information Consumers | Information literacy, deeply ingrained health concepts, and uncertain information environments reduce individuals' cognitive capacity | "Sometimes, I find myself opposing or doubting health information that conflicts with my original views, resulting in skepticism or even rejection of new health information. Facing a large amount of health information, I feel confused and unsure of what to trust." | |

| Anxiety Among Health Information Consumers | Psychological health level, health anxiety, information-induced anxiety | "During the pandemic, I paid close attention to health information, but sometimes I felt anxious because of conflicting or fake information, which affected my mood. Misinformation often causes anxiety among users." | |

|

Information Environment |

Polarized Group Environments | Polarization of groups, polarization of opinions | "In our social circles, people tend to share and forward health information aligned with their views, rarely seeing different voices. The structural setup of social media circles can lead to the spread of one-sided information, forming polarized groups and opinions." |

| Urgent Demand for Health Information | Demand for Health Information and Health Services | "When health problems arise, I first search online to check what symptoms might indicate. I hope to find authoritative information and professional services to address my concerns, and many people around me do the same." |

| Dimension/Concept | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Health Information Overload | Social media facilitates the rapid spread of emotions, opinions, or behaviors, resulting in users perceiving an overload of health information due to its low reproduction cost and complex structure. |

| Low Quality of Health Information | Online health information is often incomplete, contradictory, or outdated. It lacks timeliness, infrequent updates, and reliability, leading to users perceiving a low quality of health information. |

| Ambiguity of Information Sources | Fake or duplicate sources of health information make it difficult for users to identify the authenticity of the sources, resulting in perceived ambiguity in the origins of health information. |

| Herd Behavior Among Spreaders | Social media users may succumb to psychological and social pressures, such as peer pressure, exposure pressure, and authority influence, leading to biased or irrational behaviors. |

| Cognitive Dissonance Among Consumers | Audience members' preconceived health beliefs conflict with new health information, forming rigid impressions and resulting in misalignment between initial views and alternative perspectives. |

| Anxiety Among Consumers | The impact of health conditions on audiences' physical and mental health triggers anxiety and stress, with the overwhelming amount of health information on social media exacerbating this emotional state. |

| Polarized Group Environment | In highly cohesive social media groups, individuals are repeatedly exposed to similar health information, rarely encountering differing viewpoints, leading to group polarization and extreme opinion dynamics. |

| Urgent Demand for Health Information | The environment is shaped by the strong demand for health information and services, as users require higher-quality information or assistance to meet their health needs. |

| Dimension/Concept | Item | Reference Source |

|---|---|---|

| Health Information Overload (IO) | 1 It is difficult to fully understand the excessive health information on social media. | Y. Chen et al. [36] |

| 2 Excessive health information on social media makes it difficult for me to notice important information. | P. Pallavi et al. [37] | |

| 3 It is burdensome to fully comprehend the excessive health information on social media. | J. Jensen et al. [18] | |

| 4 Excessive health information on social media makes me feel tense. | W. Shi [38] | |

| 5 Only a small portion of the excessive health information on social media is what I need. | S. Zhang et al. [39] | |

| 6 While browsing health information on social media, I often get distracted by the abundance of information. | Y. Cao et al. [40] | |

| Low-Quality Health Information (IQ) | 1 Health information on social media is often incomplete. | E. Afful-Dadzie et al. [41] |

| 2 Health information on social media is often inconsistent. | ||

| 3 Health information on social media often lacks authenticity. | F. Adebesin et al. [42] | |

| 4 Health information on social media is often not updated in a timely manner. | Y. Zhang et al. [43] | |

| 5 Most of the health information on social media is of little value. | A. Bhattacheriee et al. [44] | |

| 6 Most of the health information on social media is meaningless. | Y. Sui [45] | |

| 7 Most of the health information on social media does not meet my needs. | J. Laugesen et al. [46] | |

| 8 Health information seen on social media is often about similar topics and categories. | ||

| 9 Health information on social media is often difficult to understand. | ||

| 10 I feel that most of the health information on social media is unprofessional. | X. Zu et al. [47] | |

| 11 I feel that most of the health information on social media is not objective. | ||

| Ambiguous Information Sources (SA) | 1 Many health information sources on social media appear to be fabricated. | Interview |

| 2 Health information sources on social media are diverse and complex, making it difficult to distinguish between true and false. | ||

| 3 Many health information sources on social media are unreliable. | N. Dalmer [48] | |

| 4 Health information sources on social media are generally untrustworthy. | ||

| 5 Most health information publishers on social media are not experts in this field. | P. Wu et al. [49] | |

| 6 Most health information publishers on social media are not qualified to comment on related topics. | C. Huo et al. [50] | |

| Herd Behavior (HB) | 1 I tend to share widely endorsed health information. | Y-I Lee et al. [51] |

| 2 The mainstream opinions on social media often influence my behavior in sharing health information. | ||

| 3 I tend to share health information that has been widely reposted. | ||

| 4 I tend to share health information published by well-known health experts on social media. | A. Hanan et al. [52] | |

| 5 I tend to share health information from authoritative organizations. | ||

| 6 I tend to share recommendations from influential users on social media. | ||

| Cognitive Conflict (CD) | 1 The health information I see on social media differs from my prior knowledge. | C. Chou et al. [53] |

| 2 The health information I see on social media conflicts with my prior knowledge. | L. Ma et al. [54] | |

| 3 The health information I see on social media is inconsistent with my prior knowledge. | R. Nagler et al. [55] | |

| 4 When I share the health information I see on social media with my family, they mostly disagree. | T. Agustina et al. [56] | |

| Anxiety (AN) | 1 Many times, I still feel confused after searching for health information on social media. | L. Pilowsky [57] |

| 2 I feel frustrated after searching for health information on social media. | ||

| 3 I feel scared after searching for health information on social media. | ||

| 4 Seeing health information related to me on social media makes me feel stressed and tense. | Interview | |

| 5 Ambiguous health information makes me feel uneasy. | P. Salkovskis [58] | |

| 6 I am annoyed by behaviors such as advertisements, requests for likes, and follows on social media. | F. Nahai et al. [59] | |

| 7 I am often forced to receive health information on social media involuntarily. | ||

| 8 I worry that personal health information on social media platforms may be leaked. | ||

| 9 I am easily influenced and disturbed by health information on social media. | ||

| Polarized Environment (GP) | 1 Social media platforms often recommend similar health information to me. | Interview |

| 2 When different opinions about health information exist on social media, I tend to trust bloggers whose views align with mine. | ||

| 3 When different opinions about health information exist on social media, I prefer the content published by bloggers I follow. | ||

| 4 When different opinions about health information exist on social media, I am more likely to repost the content from bloggers I follow to support their views. | ||

| 5 Interacting with bloggers I follow on social media deepens my impression of the health information they post. | ||

| 6 Interacting with bloggers I follow on social media makes me believe that the information they post is correct. | ||

| 7 On social media platforms, I only care about the health information posted by the bloggers I follow and ignore information from others. | ||

| 8 Browsing only health information posted by bloggers I follow on social media reduces the psychological burden of excessive online information. | ||

| Health Information Urgency (IN) | 1 The sharing and dissemination of health information on social media is extensive. | Interview |

| 2 Health information posted on social media often sparks widespread discussion. | ||

| 3 The demand for searching health information on social media is increasing. | ||

| 4 Many people first consider searching for answers on social media when facing health concerns. |

| Variable | Symbol | CITC Value | Cronbach's Alpha After Item Deletion | Overall Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IO | IO1 | 0.721 | 0.881 | 0.899 |

| IO2 | 0.75 | 0.877 | ||

| IO3 | 0.729 | 0.88 | ||

| IO4 | 0.704 | 0.884 | ||

| IO5 | 0.669 | 0.889 | ||

| IO6 | 0.778 | 0.873 | ||

| IQ | IQ1 | 0.754 | 0.882 | 0.898 |

| IQ2 | 0.749 | 0.882 | ||

| IQ3 | 0.715 | 0.884 | ||

| IQ4 | 0.688 | 0.885 | ||

| IQ5 | 0.719 | 0.884 | ||

| IQ6 | 0.732 | 0.883 | ||

| IQ7 | 0.283 | 0.91 | ||

| IQ8 | 0.3 | 0.908 | ||

| IQ9 | 0.71 | 0.884 | ||

| IQ10 | 0.678 | 0.886 | ||

| IQ11 | 0.691 | 0.885 | ||

| SA | SA1 | 0.408 | 0.879 | 0.857 |

| SA2 | 0.609 | 0.839 | ||

| SA3 | 0.763 | 0.811 | ||

| SA4 | 0.714 | 0.821 | ||

| SA5 | 0.695 | 0.824 | ||

| SA6 | 0.726 | 0.819 | ||

| HB | HB1 | 0.689 | 0.84 | 0.866 |

| HB2 | 0.637 | 0.848 | ||

| HB3 | 0.668 | 0.842 | ||

| HB4 | 0.684 | 0.839 | ||

| HB5 | 0.655 | 0.845 | ||

| HB6 | 0.646 | 0.847 | ||

| CD | CD1 | 0.723 | 0.803 | 0.854 |

| CD2 | 0.698 | 0.813 | ||

| CD3 | 0.685 | 0.819 | ||

| CD4 | 0.676 | 0.822 | ||

| AN | AN1 | 0.703 | 0.871 | 0.888 |

| AN2 | 0.742 | 0.869 | ||

| AN3 | 0.376 | 0.898 | ||

| AN4 | 0.679 | 0.873 | ||

| AN5 | 0.711 | 0.871 | ||

| AN6 | 0.736 | 0.869 | ||

| AN7 | 0.712 | 0.87 | ||

| AN8 | 0.441 | 0.894 | ||

| AN9 | 0.751 | 0.867 | ||

| GP | GP1 | 0.58 | 0.805 | 0.829 |

| GP2 | 0.7 | 0.791 | ||

| GP3 | 0.619 | 0.8 | ||

| GP4 | 0.573 | 0.806 | ||

| GP5 | 0.596 | 0.803 | ||

| GP6 | 0.594 | 0.804 | ||

| GP7 | 0.395 | 0.834 | ||

| GP8 | 0.437 | 0.825 | ||

| IN | IN1 | 0.568 | 0.714 | 0.765 |

| IN2 | 0.488 | 0.783 | ||

| IN3 | 0.607 | 0.688 | ||

| IN4 | 0.668 | 0.659 |

| Item | Factor Loading | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| IO1 | 0.781 | 0.224 | -0.022 | -0.116 | -0.085 | -0.195 | -0.073 | 0.019 |

| IO2 | 0.745 | 0.273 | -0.142 | -0.056 | -0.128 | -0.075 | -0.091 | -0.171 |

| IO2 | 0.634 | 0.332 | -0.101 | -0.155 | -0.104 | -0.239 | -0.107 | -0.094 |

| IO3 | 0.707 | 0.281 | -0.042 | -0.156 | -0.005 | -0.146 | -0.189 | -0.162 |

| IO3 | 0.571 | 0.416 | -0.22 | -0.134 | -0.138 | -0.08 | -0.143 | 0.028 |

| IO4 | 0.727 | 0.269 | -0.084 | -0.141 | -0.192 | -0.202 | -0.089 | -0.148 |

| IQ1 | 0.175 | 0.747 | -0.111 | -0.138 | -0.064 | -0.1 | -0.104 | -0.193 |

| IQ2 | 0.344 | 0.754 | 0.002 | -0.033 | 0.086 | -0.086 | -0.126 | -0.067 |

| IQ3 | 0.126 | 0.75 | -0.196 | -0.06 | -0.012 | -0.055 | -0.033 | -0.196 |

| IQ4 | 0.285 | 0.704 | -0.019 | 0.021 | 0.007 | -0.093 | -0.109 | -0.101 |

| IQ5 | 0.171 | 0.732 | -0.135 | -0.163 | 0.003 | -0.098 | -0.189 | -0.017 |

| IQ6 | 0.133 | 0.76 | -0.146 | -0.151 | -0.128 | -0.139 | -0.095 | -0.012 |

| IQ9 | 0.177 | 0.714 | -0.141 | -0.073 | -0.101 | -0.098 | -0.144 | -0.074 |

| IQ10 | 0.115 | 0.731 | -0.086 | -0.068 | -0.115 | -0.198 | -0.046 | -0.046 |

| IQ11 | 0.061 | 0.754 | -0.115 | -0.11 | -0.126 | -0.146 | -0.014 | -0.018 |

| SA2 | -0.199 | -0.105 | 0.698 | 0.07 | 0.081 | 0.154 | 0.044 | -0.071 |

| SA3 | -0.094 | -0.214 | 0.782 | 0.132 | 0.145 | 0.198 | 0.053 | 0.074 |

| SA4 | -0.067 | -0.164 | 0.72 | 0.112 | 0.171 | 0.255 | 0.148 | 0.054 |

| SA5 | 0.05 | -0.163 | 0.79 | 0.002 | 0.058 | 0.135 | 0.184 | 0.07 |

| SA6 | -0.109 | -0.143 | 0.783 | 0.157 | 0.14 | 0.097 | 0.094 | 0.034 |

| HB1 | -0.213 | -0.166 | -0.02 | 0.743 | 0.091 | 0.171 | 0.119 | 0.022 |

| HB2 | 0.005 | -0.059 | 0.224 | 0.677 | 0.035 | 0.222 | 0.195 | 0.052 |

| HB3 | -0.03 | -0.209 | 0.114 | 0.652 | 0.148 | 0.105 | 0.308 | 0.115 |

| HB4 | -0.163 | -0.141 | -0.023 | 0.753 | 0.137 | 0.122 | 0.164 | -0.01 |

| HB5 | -0.042 | -0.075 | 0.146 | 0.722 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.019 | 0.204 |

| HB6 | -0.153 | -0.041 | 0.1 | 0.719 | 0.077 | 0.042 | 0.114 | 0.173 |

| CD1 | -0.13 | -0.104 | 0.214 | 0.154 | 0.763 | 0.029 | 0.115 | 0.044 |

| CD2 | -0.142 | -0.105 | 0.091 | 0.136 | 0.783 | 0.079 | 0.164 | 0.044 |

| CD3 | -0.035 | -0.013 | 0.163 | 0.222 | 0.777 | 0.049 | -0.021 | 0.186 |

| CD4 | -0.105 | -0.098 | 0.061 | 0.01 | 0.823 | 0.081 | 0.061 | -0.021 |

| AN1 | -0.181 | -0.192 | 0.089 | 0.111 | -0.005 | 0.767 | 0.023 | 0.08 |

| AN2 | -0.139 | -0.164 | 0.184 | 0.202 | 0.092 | 0.698 | 0.215 | 0.108 |

| AN4 | -0.11 | -0.123 | 0.023 | 0.109 | 0.032 | 0.765 | 0.148 | 0.126 |

| AN5 | -0.068 | -0.199 | 0.119 | 0.092 | 0.166 | 0.709 | 0.204 | 0.13 |

| AN6 | -0.177 | -0.094 | 0.171 | 0.054 | 0.013 | 0.739 | 0.151 | 0.136 |

| AN7 | -0.156 | -0.11 | 0.112 | 0.153 | 0.051 | 0.727 | 0.142 | -0.068 |

| AN8 | 0.01 | -0.048 | 0.264 | 0.102 | 0.016 | 0.536 | -0.14 | 0.032 |

| GP1 | -0.057 | -0.072 | 0.118 | 0.107 | 0.28 | 0.15 | 0.662 | -0.002 |

| GP2 | -0.104 | -0.154 | 0.019 | 0.123 | 0.058 | 0.094 | 0.754 | 0.064 |

| GP3 | -0.149 | -0.065 | 0.111 | 0.124 | 0.103 | 0.04 | 0.688 | 0.066 |

| GP4 | -0.128 | -0.206 | 0.161 | 0.179 | -0.078 | 0.111 | 0.668 | 0.101 |

| GP5 | -0.047 | -0.12 | 0.071 | 0.188 | 0.008 | 0.178 | 0.666 | -0.063 |

| IN1 | -0.202 | -0.184 | 0.055 | 0.095 | 0.06 | 0.156 | 0.059 | 0.73 |

| IN3 | -0.026 | -0.165 | 0.018 | 0.225 | 0.132 | 0.112 | 0.001 | 0.795 |

| IN4 | -0.12 | -0.118 | 0.033 | 0.119 | 0.026 | 0.123 | 0.076 | 0.78 |

| Attribute | Category | Number of Respondents(N=561) | Percentage(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 287 | 51.2 |

| Female | 274 | 48.8 | |

| Age | <20years old | 69 | 12.3 |

| 20—29years old | 144 | 25.7 | |

| 30—39years old | 204 | 36.4 | |

| 40—49years old | 117 | 20.9 | |

| ≥50years old | 27 | 4.8 | |

| Education | Junior high school or below | 15 | 2.7 |

| High school | 39 | 7.0 | |

| Vocational college | 183 | 32.6 | |

| Bachelor's degree or above | 324 | 57.8 | |

| Social Media Usage Frequency |

Frequently, almost every day | 179 | 31.9 |

| Occasionally, 1–3 times per week | 205 | 36.5 | |

| Sometimes, 1–3 times per month | 183 | 32.6 | |

| Rarely, 1–3 times in the past three months | 39 | 7.0 | |

| Never, no usage in the past three months | 23 | 4.1 | |

| Self-Reported Health Status |

Very good | 165 | 29.4 |

| Good | 191 | 34.1 | |

| Average | 96 | 17.1 | |

| Poor | 78 | 13.9 | |

| Very poor | 31 | 5.5 |

| Item | Factor Loading | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| IO1 | 0.737 | 0.210 | 0.086 | 0.048 | 0.167 | 0.089 | 0.193 | 0.051 |

| IO2 | 0.773 | 0.156 | 0.108 | 0.124 | 0.038 | 0.135 | 0.080 | 0.091 |

| IO3 | 0.772 | 0.122 | 0.087 | 0.065 | 0.084 | 0.142 | 0.120 | 0.009 |

| IO4 | 0.769 | 0.134 | 0.135 | 0.073 | 0.058 | 0.174 | 0.107 | 0.064 |

| IO5 | 0.746 | 0.137 | 0.130 | 0.072 | 0.064 | 0.137 | 0.128 | 0.057 |

| IO6 | 0.728 | 0.062 | 0.056 | 0.106 | 0.185 | 0.208 | 0.126 | 0.143 |

| IQ1 | 0.158 | 0.674 | 0.184 | 0.111 | 0.123 | 0.228 | 0.110 | 0.115 |

| IQ2 | 0.163 | 0.729 | 0.139 | 0.012 | 0.116 | 0.108 | 0.098 | 0.152 |

| IQ3 | 0.189 | 0.740 | 0.106 | 0.117 | 0.036 | 0.143 | 0.158 | 0.079 |

| IQ4 | 0.205 | 0.754 | 0.143 | 0.106 | 0.070 | 0.036 | 0.120 | 0.049 |

| IQ5 | 0.034 | 0.726 | 0.163 | 0.180 | 0.036 | 0.185 | 0.209 | 0.108 |

| IQ6 | 0.126 | 0.741 | 0.078 | 0.062 | 0.160 | 0.083 | 0.155 | 0.085 |

| IQ7 | 0.107 | 0.751 | 0.143 | 0.118 | 0.114 | 0.237 | 0.064 | 0.043 |

| IQ8 | -0.039 | 0.749 | 0.045 | 0.163 | 0.020 | 0.176 | 0.137 | 0.022 |

| IQ9 | 0.103 | 0.792 | 0.064 | 0.104 | 0.135 | 0.111 | 0.085 | 0.099 |

| SA1 | 0.093 | 0.126 | 0.732 | 0.118 | -0.007 | 0.197 | 0.141 | 0.069 |

| SA2 | 0.087 | 0.151 | 0.749 | 0.200 | 0.193 | 0.013 | 0.066 | 0.039 |

| SA3 | 0.115 | 0.226 | 0.769 | 0.135 | 0.091 | 0.079 | 0.084 | 0.063 |

| SA4 | 0.099 | 0.140 | 0.752 | 0.117 | 0.174 | 0.038 | 0.148 | 0.099 |

| SA5 | 0.212 | 0.171 | 0.761 | 0.156 | 0.112 | 0.159 | 0.093 | -0.010 |

| HB1 | 0.062 | 0.124 | 0.107 | 0.792 | 0.041 | 0.048 | 0.083 | 0.123 |

| HB2 | 0.038 | 0.113 | 0.168 | 0.752 | 0.127 | 0.162 | 0.146 | 0.091 |

| HB3 | 0.174 | 0.114 | 0.096 | 0.778 | 0.162 | 0.037 | 0.130 | 0.148 |

| HB4 | 0.081 | 0.131 | 0.084 | 0.769 | 0.136 | 0.095 | 0.073 | 0.029 |

| HB5 | -0.008 | 0.122 | 0.139 | 0.759 | 0.018 | 0.125 | 0.033 | 0.051 |

| HB6 | 0.163 | 0.142 | 0.127 | 0.770 | 0.050 | 0.097 | 0.199 | 0.063 |

| CD1 | 0.122 | 0.187 | 0.252 | 0.097 | 0.727 | 0.243 | 0.146 | 0.113 |

| CD2 | 0.120 | 0.120 | 0.098 | 0.154 | 0.757 | 0.210 | 0.171 | 0.108 |

| CD3 | 0.158 | 0.204 | 0.172 | 0.163 | 0.737 | 0.210 | 0.175 | 0.137 |

| CD4 | 0.220 | 0.190 | 0.127 | 0.153 | 0.703 | 0.145 | 0.170 | 0.038 |

| AN1 | 0.156 | 0.172 | 0.108 | 0.112 | 0.042 | 0.763 | 0.168 | 0.093 |

| AN2 | 0.194 | 0.124 | 0.067 | 0.134 | 0.152 | 0.734 | 0.118 | 0.065 |

| AN3 | 0.059 | 0.215 | 0.085 | 0.074 | 0.139 | 0.760 | 0.098 | 0.161 |

| AN4 | 0.148 | 0.162 | -0.010 | 0.088 | 0.101 | 0.785 | 0.114 | 0.059 |

| AN5 | 0.133 | 0.175 | 0.091 | 0.129 | 0.137 | 0.732 | 0.036 | 0.079 |

| AN6 | 0.138 | 0.132 | 0.147 | 0.049 | 0.058 | 0.768 | 0.185 | -0.017 |

| AN7 | 0.144 | 0.145 | 0.071 | 0.050 | 0.179 | 0.693 | 0.205 | 0.174 |

| GP1 | 0.119 | 0.145 | 0.069 | 0.113 | 0.055 | 0.169 | 0.779 | 0.098 |

| GP2 | 0.124 | 0.192 | 0.132 | 0.106 | 0.112 | 0.182 | 0.769 | 0.052 |

| GP3 | 0.166 | 0.167 | 0.088 | 0.122 | 0.138 | 0.147 | 0.744 | 0.065 |

| GP4 | 0.150 | 0.067 | 0.145 | 0.113 | 0.089 | 0.082 | 0.788 | 0.094 |

| GP5 | 0.135 | 0.223 | 0.086 | 0.078 | 0.050 | 0.164 | 0.790 | 0.026 |

| GP6 | 0.081 | 0.168 | 0.058 | 0.143 | 0.204 | 0.113 | 0.755 | 0.079 |

| IN1 | 0.058 | 0.227 | 0.068 | 0.180 | 0.082 | 0.137 | 0.151 | 0.757 |

| IN2 | 0.155 | 0.119 | 0.087 | 0.252 | 0.124 | 0.191 | 0.097 | 0.745 |

| IN3 | 0.158 | 0.214 | 0.092 | 0.067 | 0.128 | 0.173 | 0.113 | 0.783 |

| Item | Average Variance Extracted AVE Value | Composite Reliability CR Value |

|---|---|---|

| IO | 0.584 | 0.894 |

| IQ | 0.634 | 0.940 |

| SA | 0.647 | 0.902 |

| HB | 0.619 | 0.907 |

| CD | 0.613 | 0.863 |

| AN | 0.623 | 0.920 |

| GP | 0.626 | 0.909 |

| IN | 0.624 | 0.833 |

| IO | IQ | SA | HB | CD | AN | GP | IN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IO | 0.764 | |||||||

| IQ | 0.418 | 0.796 | ||||||

| SA | 0.392 | 0.446 | 0.804 | |||||

| HB | 0.461 | 0.485 | 0.444 | 0.787 | ||||

| CD | 0.458 | 0.402 | 0.441 | 0.525 | 0.783 | |||

| AN | 0.395 | 0.473 | 0.418 | 0.455 | 0.420 | 0.789 | ||

| GP | 0.451 | 0.485 | 0.417 | 0.475 | 0.461 | 0.483 | 0.791 | |

| IN | 0.416 | 0.377 | 0.416 | 0.408 | 0.454 | 0.405 | 0.426 | 0.790 |

| Note: The diagonal values represent the square root of the AVE. | ||||||||

| Unstd | S.E. | C.R. | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IO6 | <--- | IO | 1 | |||

| IO5 | <--- | IO | 0.923 | 0.069 | 13.34 | *** |

| IO4 | <--- | IO | 1.005 | 0.072 | 14.008 | *** |

| IO3 | <--- | IO | 0.963 | 0.071 | 13.489 | *** |

| IO2 | <--- | IO | 0.873 | 0.067 | 13.013 | *** |

| IO1 | <--- | IO | 0.918 | 0.07 | 13.105 | *** |

| IQ1 | <--- | IQ | 1 | |||

| IQ2 | <--- | IQ | 0.932 | 0.065 | 14.331 | *** |

| IQ3 | <--- | IQ | 0.981 | 0.065 | 15.122 | *** |

| IQ4 | <--- | IQ | 0.985 | 0.065 | 15.175 | *** |

| IQ5 | <--- | IQ | 1.017 | 0.066 | 15.381 | *** |

| IQ6 | <--- | IQ | 0.997 | 0.066 | 15.149 | *** |

| IQ7 | <--- | IQ | 0.992 | 0.065 | 15.198 | *** |

| IQ8 | <--- | IQ | 0.965 | 0.065 | 14.841 | *** |

| IQ9 | <--- | IQ | 1.027 | 0.066 | 15.633 | *** |

| CD4 | <--- | CD | 1 | |||

| CD3 | <--- | CD | 0.924 | 0.069 | 13.422 | *** |

| CD2 | <--- | CD | 0.928 | 0.068 | 13.618 | *** |

| CD1 | <--- | CD | 1.017 | 0.069 | 14.686 | *** |

| SA1 | <--- | SA | 1 | |||

| SA2 | <--- | SA | 1.034 | 0.07 | 14.762 | *** |

| SA3 | <--- | SA | 1.028 | 0.07 | 14.759 | *** |

| SA4 | <--- | SA | 1.01 | 0.068 | 14.832 | *** |

| SA5 | <--- | SA | 0.976 | 0.07 | 13.899 | *** |

| HB1 | <--- | HB | 1 | |||

| HB2 | <--- | HB | 0.965 | 0.068 | 14.153 | *** |

| HB3 | <--- | HB | 1.01 | 0.067 | 15.117 | *** |

| HB4 | <--- | HB | 0.972 | 0.067 | 14.597 | *** |

| HB5 | <--- | HB | 0.955 | 0.066 | 14.528 | *** |

| HB6 | <--- | HB | 0.978 | 0.068 | 14.466 | *** |

| AN6 | <--- | AN | 1 | |||

| AN5 | <--- | AN | 1.002 | 0.072 | 14.002 | *** |

| AN4 | <--- | AN | 0.966 | 0.07 | 13.889 | *** |

| AN3 | <--- | AN | 1.018 | 0.073 | 13.853 | *** |

| AN2 | <--- | AN | 1.02 | 0.072 | 14.25 | *** |

| AN1 | <--- | AN | 1.009 | 0.072 | 14.097 | *** |

| AN7 | <--- | AN | 1.004 | 0.072 | 14.011 | *** |

| GP6 | <--- | GP | 1 | |||

| GP5 | <--- | GP | 0.922 | 0.064 | 14.3 | *** |

| GP4 | <--- | GP | 0.938 | 0.066 | 14.132 | *** |

| GP3 | <--- | GP | 0.975 | 0.065 | 14.904 | *** |

| GP2 | <--- | GP | 0.966 | 0.064 | 15.032 | *** |

| GP1 | <--- | GP | 1.031 | 0.069 | 14.924 | *** |

| IN3 | <--- | IN | 0.944 | 0.074 | 12.717 | *** |

| IN2 | <--- | IN | 0.923 | 0.071 | 12.958 | *** |

| IN1 | <--- | IN | 1 |

| Fit Index | CMIN/DF | RMSEA | CFI | IFI | TLI | PGFI | PCFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research Result | 1.043 | 0.012 | 0.995 | 0.995 | 0.995 | 0.776 | 0.924 |

| Evaluation Criterion | <3.00 | <0.08 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.50 | >0.50 |

| Meets Criterion | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Percentile | IO | IQ | SA | HB | CD | AN | GP | IN | Total Perception Intensity Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 11.00 | 16.00 | 9.00 | 11.00 | 7.00 | 13.00 | 11.00 | 5.00 | 115.00 |

| 10 | 12.00 | 19.00 | 10.00 | 12.00 | 8.00 | 14.00 | 11.00 | 6.00 | 120.20 |

| 15 | 13.00 | 20.00 | 11.00 | 13.00 | 8.30 | 16.00 | 13.00 | 6.00 | 124.30 |

| 20 | 14.40 | 21.00 | 12.00 | 14.00 | 9.00 | 17.00 | 14.00 | 7.00 | 127.00 |

| 25 | 16.00 | 23.00 | 13.00 | 15.00 | 10.00 | 18.00 | 15.00 | 8.00 | 130.00 |

| 30 | 17.00 | 25.00 | 14.00 | 16.00 | 10.00 | 19.00 | 16.00 | 8.00 | 132.00 |

| 35 | 18.00 | 26.00 | 15.00 | 17.00 | 11.00 | 20.00 | 17.00 | 9.00 | 134.00 |

| 40 | 18.00 | 27.00 | 16.00 | 18.00 | 12.00 | 21.00 | 18.00 | 9.00 | 136.00 |

| 45 | 19.00 | 28.00 | 16.00 | 19.00 | 12.00 | 22.00 | 19.00 | 10.00 | 139.00 |

| 50 | 20.00 | 29.00 | 17.00 | 20.00 | 13.00 | 23.00 | 20.00 | 10.00 | 142.00 |

| 55 | 21.00 | 31.00 | 18.00 | 21.00 | 14.00 | 24.00 | 20.00 | 11.00 | 145.00 |

| 60 | 22.00 | 32.00 | 18.00 | 22.00 | 14.00 | 26.00 | 21.20 | 11.00 | 148.00 |

| 65 | 23.00 | 34.00 | 19.00 | 22.30 | 15.00 | 27.00 | 23.00 | 11.00 | 156.00 |

| 70 | 23.40 | 35.00 | 20.00 | 23.00 | 16.00 | 28.00 | 24.00 | 12.00 | 175.40 |

| 75 | 24.00 | 36.00 | 20.00 | 25.00 | 17.00 | 29.00 | 24.00 | 12.00 | 183.00 |

| 80 | 25.60 | 38.00 | 21.00 | 25.60 | 17.00 | 30.00 | 26.00 | 13.00 | 187.00 |

| 85 | 27.00 | 40.00 | 23.00 | 27.00 | 18.00 | 32.00 | 27.00 | 13.00 | 192.00 |

| 90 | 28.00 | 43.00 | 24.00 | 28.00 | 19.00 | 33.00 | 29.00 | 15.00 | 198.00 |

| 95 | 30.00 | 44.00 | 25.00 | 30.00 | 20.00 | 35.00 | 30.00 | 15.00 | 211.90 |

| Level | Classification Standard | IO | IQ | SA | HB | CD | AN | GP | IN | Total Perception Intensity Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | <P10 | <12.00 | <19.00 | <10.00 | <12.00 | <8.00 | <14.00 | <11.00 | <6.00 | <120.20 |

| Relatively Low | Relatively Low | Relatively Low | Relatively Low | Relatively Low | Relatively Low | Relatively Low | Relatively Low | Relatively Low | Relatively Low | Relatively Low |

| Average | P30—P70 | 17.00- 23.40 |

25.00- 35.00 |

14.00- 20.00 |

16.00- 23.00 |

10.00- 16.00 |

19.00- 28.00 |

16.00- 24.00 |

8.00- 12.00 |

132.00- 175.40 |

| Relatively High | P70—P90 | 23.40- 28.00 |

35.00- 43.00 |

20.00- 24.00 |

23.00- 28.00 |

16.00- 19.00 |

28.00- 33.00 |

24.00- 29.00 |

12.00- 15.00 |

175.40- 198.00 |

| High | >P90 | >28.00 | >43.00 | >24.00 | >28.00 | >19.00 | >33.00 | >29.00 | >15.00 | >198.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).