Submitted:

03 January 2025

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

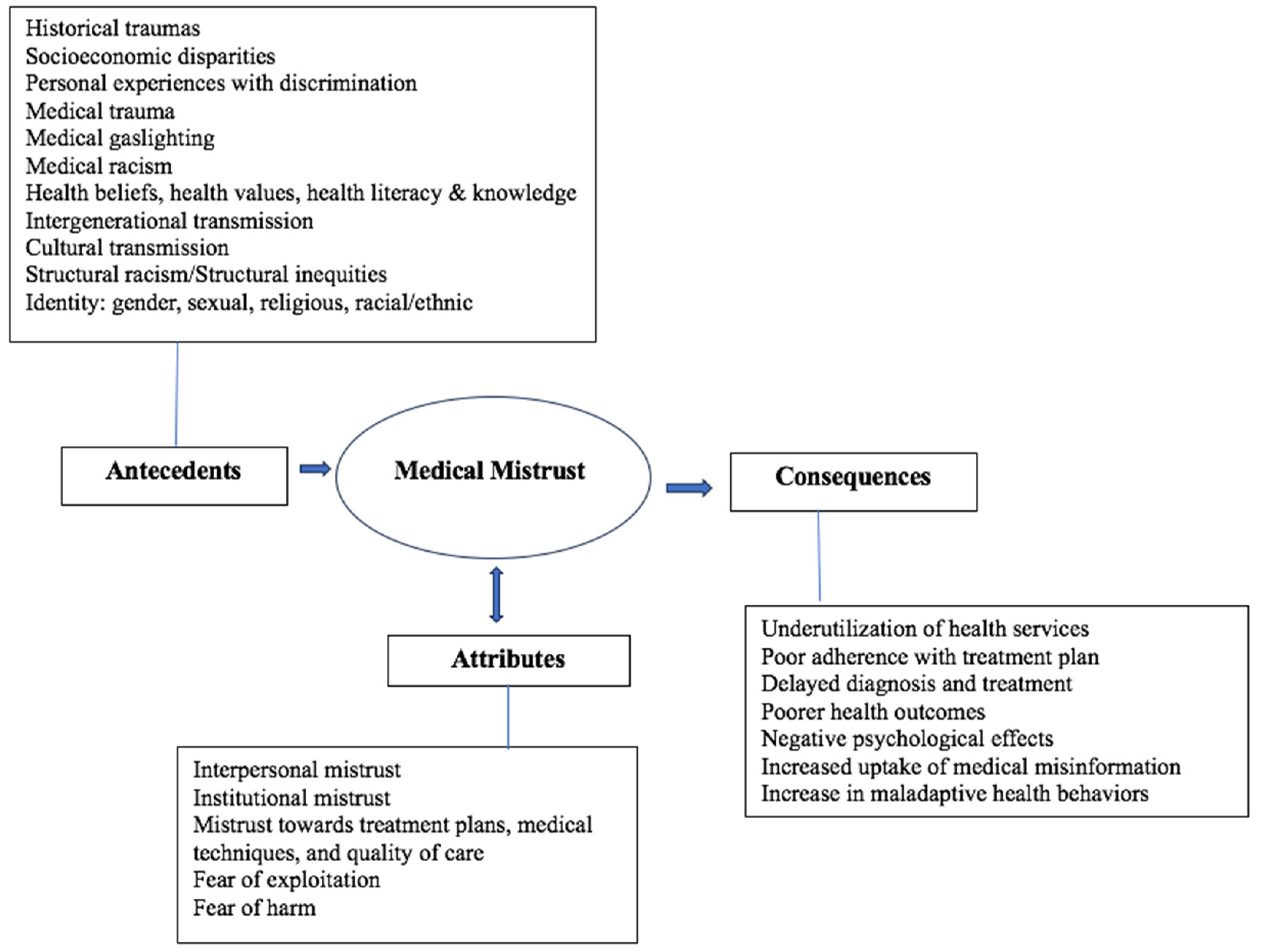

Background The term “medical mistrust” has increased in literary usage within the last ten years, but the term has not yet been given a full conceptualization. This article analyzes usage of the term “medical mistrust” in extant literature in order to articulate its antecedents, attributes, and consequences. The aim of this article is to provide a preliminary conceptual definition and conceptual figure for medical mistrust. Methods Walker & Avant’s (2019) conceptual analysis method was used. PUBMED, CINAHL, SCOPUS, PSYCinfo, and Google search engines were used. Results Medical mistrust is a social determinant of health fueled by a fear of harm and exploitation, and is experienced at both the interpersonal and institutional level, reinforced by structural racism and systemic inequalities. Medical mistrust is predicated by historical trauma, socioeconomic disparities, medical gaslighting, medical traumatic experiences, maladaptive health beliefs and behaviors, individual minority identity, and is transmitted intergenerationally and culturally. Consequences of medical mistrust include underutilization of health services, delays in diagnosis and care, poor treatment adherence, poor health outcomes, negative psychological effects, and an increase in the uptake of medical misinformation and maladaptive health behaviors. Conclusion The findings of this concept analysis have important implications for healthcare providers, healthcare systems, researchers, as well as healthcare policy makers.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Definition of Medical Mistrust

1.2. Difficulties Defining Medical Mistrust

1.3. Purpose of the Analysis

1.3.1. Clarify the Meaning of Medical Mistrust

1.3.2. Identify Key Attributes, Antecedents, and Consequences of Medical Mistrust

2. Methods

- Select a concept.

- Determine the aims or purposes of analysis.

- Identify all uses of the concept that you can discover.

- Determine the defining attributes

- Identify a model case.

- Identify borderline, related, contrary, invented, and illegitimate cases.

- Identify antecedents and consequences

- Define empirical referents.

2.1. Literature Review

3. Results

3.1. Attributes of Medical Mistrust

3.2. Antecedents and Consequences of Medical Mistrust

3.2. Figures, Tables and Schemes

| Attributes | Antecedents | Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal mistrust: suspicion and skepticism towards healthcare providers and their intentions | Historical traumas | Underutilization of health services |

| Institutional mistrust: toward healthcare systems | Socioeconomic disparities | Poor adherence with treatment plan |

| Mistrust about treatment plans, medical techniques, and quality of care provided | Personal experiences with discrimination | Delayed diagnosis and treatment |

| Fear of exploitation | Medical trauma | Poor health outcomes |

| Fear of harm | Medical gaslighting | Increased uptake of medical misinformation |

| Medical racism | Negative psychological effects: anger, powerlessness, loss of faith in healthcare system, depression, anxiety | |

| Health beliefs, health values, health literacy/knowledge | Increase in maladaptive health behaviors | |

| Intergenerational transmissionCultural transmission | ||

| Structural racism/Structural inequities | ||

| Identity status including ethnic identity, gender identity, sexual orientation, and religious identity |

3.3. Model Cases

3.3.1. Case One: Model Case

3.3.2. Case Two: Relevant Case

3.3.3. Case Three: Contrary

3.4. Empirical Referents

| Tool | # of items | Rating scale | Aspects | Reliability(Cronbach alpha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group Based Medical Mistrust Scale (GBMMS) | 12 | 5-point Likert Scale | Subscales are: Suspicion of healthcare providers, Group disparities in healthcare, lack of support from healthcare providers |

0.83 |

| Medical Mistrust Index (MMI) | 7 | 4-point Likert scale | Mistrust of healthcare organizations and the medical care systems | 0.76 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Definition

4.2. Future Implications of Medical Mistrust

4.2.1. For Future Research

4.2.2. For Healthcare Providers/Organizations

4.2.3. For Health Policy Makers

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bylund Grenklo, T., Kreicbergs, U. C., Valdimarsdóttir, U. A., Nyberg, T., Steineck, G., & Fürst, C. J. (2013). Communication and trust in the care provided to a dying parent: a nationwide study of cancer-bereaved youths. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31, 2886- 2894. [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, J., & Halkitis, P. N. (2019). Towards a more inclusive and dynamic understanding of medical mistrust informed by science. Behavioral Medicine, 45(2), 79-85.

- Rose, A., Peters, N., Shea, J. A., & Armstrong, K. (2004). Development and testing of the health care system distrust scale. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 19, 57-63. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, H. S., Valdimarsdottir, H. B., Winkel, G., Jandorf, L., & Redd, W. (2004). The Group-Based Medical Mistrust Scale: psychometric properties and association with breast cancer screening. Preventive medicine, 38(2), 209-218.

- Oakley, L. P., López-Cevallos, D. F., & Harvey, S. M. (2019). The association of cultural and structural factors with perceived medical mistrust among young adult Latinos in rural Oregon. Behavioral Medicine, 45(2), 118-127.

- Trent, M., Gooley, D.G., Douge, J. (2019). The impact of racism on child and adolescent health. Pediatrics,144(2):e20191765.

- Hostetter, M., & Klein, S. (2021, January 14). Understanding and ameliorating medical mistrust among black americans. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletter-article/2021/jan/medical-mistrust-among-black-americans.

- Shaughnessy, A. F., Andrea Vicini Sj, Zgurzynski, M., O’Reilly-Jacob, M., & Duggan, A. P. (2023). Indicators of the dimensions of trust (and mistrust) in early primary care practice: a qualitative study. BMC Primary Care, 24(1). [CrossRef]

- Ash, M. J., Berkley-Patton, J., Christensen, K., Haardörfer, R., Livingston, M. D., Miller, T., & Woods-Jaeger, B. (2021). Predictors of medical mistrust among urban youth of color during the COVID-19 pandemic. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 11(8), 1626-1634. [CrossRef]

- Peek, M. E., Gorawara-Bhat, R., Quinn, M. T., Odoms-Young, A., Wilson, S. C., & Chin, M. H. (2013). Patient Trust in Physicians and Shared Decision-Making Among African-Americans With Diabetes. Health Communication, 28(6), 616–623. [CrossRef]

- Choy, H. H., & Ismail, A. (2017). Indicators for Medical Mistrust in Healthcare–A Review and Standpoint from Southeast Asia. The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences : MJMS, 24(6), 5–20. [CrossRef]

- Pappas, C., & Williams, I. (2011). Grey literature: its emerging importance. Journal of Hospital Librarianship, 11(3), 228-234.

- Hopewell, S., McDonald, S., Clarke, M. J., & Egger, M. (2007). Grey literature in meta-analyses of randomized trials of health care interventions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2).

- Walker LO, Avant KC. Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing. 6th edition. Boston: Pearson; 2019.

- Adams, L. B., Richmond, J., Corbie-Smith, G., & Powell, W. (2017). Medical mistrust and colorectal cancer screening among African Americans. Journal of community health, 42(5), 1044-1061.

- Ball, K., Lawson, W., & Alim, T. (2013). Medical mistrust, conspiracy beliefs & HIV-related behavior among African Americans. J Psychol Behav Sci, 1(1), 1-7.

- Brenick, A., Romano, K., Kegler, C., & Eaton, L. A. (2017). Understanding the influence of stigma and medical mistrust on engagement in routine healthcare among black women who have sex with women. LGBT health, 4(1), 4-10.

- Fisher, C. B., Fried, A. L., Macapagal, K., & Mustanski, B. (2018). Patient–provider communication barriers and facilitators to HIV and STI preventive services for adolescent MSM. AIDS and Behavior, 22(10), 3417-3428.

- Griffin, M., Cahill, S., Kapadia, F., & Halkitis, P. N. (2020). Healthcare usage and satisfaction among young adult gay men in New York city. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 32(4), 531-551.

- Kinlock, B. L., Parker, L. J., Bowie, J. V., Howard, D. L., LaVeist, T. A., & Thorpe Jr, R. J. (2017). High levels of medical mistrust are associated with low quality of life among black and white men with prostate cancer.

- López-Cevallos, D. F., Harvey, S. M., & Warren, J. T. (2014). Medical mistrust, perceived discrimination, and satisfaction with health care among young-adult rural Latinos. The Journal of Rural Health, 30(4), 344-351.

- Powell, W., Richmond, J., Mohottige, D., Yen, I., Joslyn, A., & Corbie-Smith, G. (2019). Medical mistrust, racism, and delays in preventive health screening among African-American men. Behavioral Medicine, 45(2), 102-117.

- Randolph, S. D., Golin, C., Welgus, H., Lightfoot, A. F., Harding, C. J., & Riggins, L. F. (2020). How perceived structural racism and discrimination and medical mistrust in the health system influences participation in HIV health services for black women living in the United States South: a qualitative, descriptive study. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 31(5), 598-605.

- Tekeste, M., Hull, S., Dovidio, J. F., Safon, C. B., Blackstock, O., Taggart, T., ... & Calabrese, S. K. (2018). Differences in medical mistrust between black and white women: implications for patient–provider communication about PrEP. AIDS and Behavior, 23(7), 1737-1748.

- Bazargan, M., Cobb, S., & Assari, S. (2021). Discrimination and medical mistrust in a racially and ethnically diverse sample of California adults. The Annals of Family Medicine, 19(1), 4-15.

- Guadagnolo, B. A., Cina, K., Helbig, P., Molloy, K., Reiner, M., Cook, E. F., & Petereit, D. G. (2009). Medical mistrust and less satisfaction with health care among Native Americans presenting for cancer treatment. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved, 20(1), 210.

- LaVeist, T. A., Nickerson, K. J., & Bowie, J. V. (2000). Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African American and white cardiac patients. Medical Care Research and Review, 57(1_suppl), 146-161.

- Ross, M. W., Essien, E. J., & Torres, I. (2006). Conspiracy beliefs about the origin of HIV/AIDS in four racial/ethnic groups. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999), 41(3), 342.

- Westergaard, R. P., Beach, M. C., Saha, S., & Jacobs, E. A. (2014). Racial/ethnic differences in trust in health care: HIV conspiracy beliefs and vaccine research participation. Journal of general internal medicine, 29(1), 140-146.

- Brandon, D. T., Isaac, L. A., & LaVeist, T. A. (2005). The legacy of Tuskegee and trust in medical care: is Tuskegee responsible for race differences in mistrust of medical care? Journal of the National Medical Association, 97(7), 951.

- Corbie-Smith, G., Frank, E., Nickens, H. W., & Elon, L. (1999). Prevalences and correlates of ethnic harassment in the US Women Physicians' Health Study. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 74(6), 695-701.

- Freimuth, V. S., Quinn, S. C., Thomas, S. B., Cole, G., Zook, E., & Duncan, T. (2001). African Americans’ views on research and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Social science & medicine, 52(5), 797-808.

- Gamble, V. N. (1997). Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. American journal of public health, 87(11), 1773-1778.

- Scharff, D. P., Mathews, K. J., Jackson, P., Hoffsuemmer, J., Martin, E., & Edwards, D. (2010). More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved, 21(3), 879.

- Griffin, D. S., Muhlbauer, G., & Griffin, D. O. (2018). Adolescents trust physicians for vaccine information more than their parents or religious leaders. Heliyon, 4(12), e01006.

- Bogart, L. M., & Thorburn, S. (2005). Are HIV/AIDS conspiracy beliefs a barrier to HIV prevention among African Americans? Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 38, 213-218. [CrossRef]

- Hall, M. A., Dugan, E., Zheng, B., & Mishra, A. K. (2001). Trust in physicians and medical institutions: what is it, can it be measured, and does it matter?. The milbank quarterly, 79(4), 613-639.

- Thom, D. H., Hall, M. A., & Pawlson, L. G. (2004). Measuring patients’ trust in physicians when assessing quality of care. Health affairs, 23(4), 124-132.

- Halbert, C. H., Weathers, B., Delmoor, E., Mahler, B., Coyne, J., Thompson, H. S., ... & Lee, D. (2009). Racial differences in medical mistrust among men diagnosed with prostate cancer. Cancer, 115(11), 2553-2561.

- Boulware, L. E., Cooper, L. A., Ratner, L. E., LaVeist, T. A., & Powe, N. R. (2003). Race and trust in the health care system. Public health reports, 118(4), 358.

- Doescher, M. P., Saver, B. G., Franks, P., & Fiscella, K. (2000). Racial and ethnic disparities in perceptions of physician style and trust.

- Goodin, B. R., Pham, Q. T., Glover, T. L., Sotolongo, A., King, C. D., Sibille, K. T., ... & Fillingim, R. B. (2013). Perceived racial discrimination, but not mistrust of medical researchers, predicts the heat pain tolerance of African Americans with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Health Psychology, 32(11), 1117.

- Gordon, H. S., Street Jr, R. L., Sharf, B. F., Kelly, P. A., & Souchek, J. (2006). Racial differences in trust and lung cancer patients' perceptions of physician communication. Journal of clinical oncology, 24(6), 904-909.

- King, W. D. (2003). Examining African Americans' mistrust of the health care system: expanding the research question. Commentary on" Race and trust in the health care system". Public Health Reports, 118(4), 366.

- O'Malley, A. S., Sheppard, V. B., Schwartz, M., & Mandelblatt, J. (2004). The role of trust in use of preventive services among low-income African-American women. Preventive medicine, 38(6), 777-785.

- Benkert, R., Peters, R. M., & Templin, T. N. (2019). Sociodemographics and medical mistrust in a population based sample of Michigan residents. Int J Nurs Health Care Res, 6, 092.

- Abel, W. M., & Efird, J. T. (2013). The association between trust in health care providers and medication adherence among Black women with hypertension. Frontiers in public health, 1, 66.

- Blackstock, O. J., Addison, D. N., Brennan, J. S., & Alao, O. A. (2012). Trust in primary care providers and antiretroviral adherence in an urban HIV clinic. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved, 23(1), 88-98.

- Elder, K., Ramamonjiarivelo, Z., Wiltshire, J., Piper, C., Horn, W. S., Gilbert, K. L., ... & Allison, J. (2012). Trust, medication adherence, and hypertension control in Southern African American men. American journal of public health, 102(12), 2242-2245.

- Graham, J. L., Giordano, T. P., Grimes, R. M., Slomka, J., Ross, M., & Hwang, L. Y. (2010). Influence of trust on HIV diagnosis and care practices: a literature review. Journal of the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care, 9(6), 346-352.

- Jneid, S., Jabbour, H., Hajj, A., Sarkis, A., Licha, H., Hallit, S., & Khabbaz, L. R. (2018). Quality of life and its association with treatment satisfaction, adherence to medication, and trust in physician among patients with hypertension: a cross-sectional designed study. Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology and therapeutics, 23(6), 532-542.

- Nguyen, G. C., LaVeist, T. A., Harris, M. L., Datta, L. W., Bayless, T. M., & Brant, S. R. (2009). Patient trust-in-physician and race are predictors of adherence to medical management in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory bowel diseases, 15(8), 1233-1239.

- Pellowski, J. A., Price, D. M., Allen, A. M., Eaton, L. A., & Kalichman, S. C. (2017). The differences between medical trust and mistrust and their respective influences on medication beliefs and ART adherence among African-Americans living with HIV. Psychology & health, 32(9), 1127-1139.

- Saha, S., Jacobs, E. A., Moore, R. D., & Beach, M. C. (2010). Trust in physicians and racial disparities in HIV care. AIDS patient care and STDs, 24(7), 415-420.

- Whetten, K., Leserman, J., Whetten, R., Ostermann, J., Thielman, N., Swartz, M., & Stangl, D. (2006). Exploring lack of trust in care providers and the government as a barrier to health service use. American journal of public health, 96(4), 716-721.

- Graham, J. L., Shahani, L., Grimes, R. M., Hartman, C., & Giordano, T. P. (2015). The influence of trust in physicians and trust in the healthcare system on linkage, retention, and adherence to HIV care. AIDS patient care and STDs, 29(12), 661-667.

- Graham, J. L., Grimes, R. M., Slomka, J., Ross, M., Hwang, L. Y., & Giordano, T. P. (2013). The role of trust in delayed HIV diagnosis in a diverse, urban population. AIDS and Behavior, 17(1), 266-273.

- Thom, D. H., Ribisl, K. M., Stewart, A. L., Luke, D. A., & The Stanford Trust Study Physicians. (1999). Further validation and reliability testing of the Trust in Physician Scale. Medical care, 510-517.

- Trachtenberg, F., Dugan, E., & Hall, M. A. (2005). How patients' trust relates to their involvement in medical care. Journal of Family Practice, 54(4), 344-354.

- Hall, O. T., Jordan, A., Teater, J., Dixon-Shambley, K., McKiever, M. E., Baek, M., ... & Fielin, D. A. (2022). Experiences of racial discrimination in the medical setting and associations with medical mistrust and expectations of care among black patients seeking addiction treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 133, 108551.

- Fisher, J. A. (2008). Institutional mistrust in the organization of pharmaceutical clinical trials. Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy, 11(4), 403–413. [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, A. B., Corbie-Smith, G., Thomas, S. B., Mohanan, S., & Del Rio, C. (2004). Understanding the patient’s perspective on rapid and routine HIV testing in an inner-city urgent care center. AIDS Education and prevention, 16(2), 101–114.

- LaVeist, T. A., Isaac, L. A., & Williams, K. P. (2009). Mistrust of Health Care Organizations Is Associated with Underutilization of Health Services. Health Services Research, 44(6), 2093–2105. [CrossRef]

- Bogart, L. M., Takada, S., & Cunningham, W. E. (2021). Medical mistrust, discrimination, and the domestic HIV epidemic. HIV in US Communities of Color, 207-231.

- Cuevas, A. G., & O’Brien, K. (2019). Racial centrality may be linked to mistrust in healthcare institutions for African Americans. Journal of health psychology, 24(14), 2022-2030.

- Allen, J. D., Fu, Q., Shrestha, S., Nguyen, K. H., Stopka, T. J., Cuevas, A., & Corlin, L. (2022). Medical mistrust, discrimination, and COVID-19 vaccine behaviors among a national sample U.S. adults. SSM - Population Health, 20, 101278. [CrossRef]

- Hoadley, A., Bass, S. B., Chertock, Y., Brajuha, J., D’Avanzo, P., Kelly, P. J., & Hall, M. J. (2022). The role of medical mistrust in concerns about tumor genomic profiling among Black and African American cancer patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2598.

- Owens, D. C., & Fett, S. M. (2019). Black maternal and infant health: historical legacies of slavery. American journal of public health, 109(10), 1342-1345.

- Mendes, M. M. (2022). My Grandmother, My Mother, and Me; The Effects of Intergenerational Healthcare Trauma on a Multiethnic Family, With a Focus on Black Women.

- Armstrong, K., Ravenell, K. L., McMurphy, S., & Putt, M. (2007). Racial/ethnic differences in physician distrust in the United States. American journal of public health, 97(7), 1283-1289.

- Bazargan, M., Cobb, S., & Assari, S. (2021). Discrimination and Medical Mistrust in a Racially and Ethnically Diverse Sample of California Adults. The Annals of Family Medicine, 19(1), 4–15. [CrossRef]

- Hall, G. L., & Heath, M. (2021). Poor medication adherence in African Americans is a matter of trust. Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities, 8(4), 927-942.

- Thompson, H. S., Manning, M., Mitchell, J., Kim, S., Harper, F. W., Cresswell, S., ... & Marks, B. (2021). Factors associated with racial/ethnic group–based medical mistrust and perspectives on COVID-19 vaccine trial participation and vaccine uptake in the US. JAMA Network Open, 4(5), e2111629-e2111629.

- Sutton, A. L., He, J., Edmonds, M. C., & Sheppard, V. B. (2019). Medical mistrust in black breast cancer patients: acknowledging the roles of the trustor and the trustee. Journal of Cancer Education, 34, 600-607.

- Wang, J. C., Dalke, K. B., Nachnani, R., Baratz, A. B., & Flatt, J. D. (2023). Medical mistrust mediates the relationship between nonconsensual intersex surgery and healthcare avoidance among intersex adults. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 57(12), 1024-1031.

- Grimaldi, A. L. (2020). “Malicious Medicine”: A Qualitative Study of Medical Mistrust and PrEp Perceptions for African American and Hispanic Men and Women in New Haven, CT (Master's thesis, Yale University).

- Smallwood, R., Woods, C., Power, T., & Usher, K. (2020). Understanding the impact of historical trauma due to colonization on the health and well-being of indigenous young peoples: A systematic scoping review. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 32(1), 59–68. [CrossRef]

- Idan, E., Xing, A., Ivory, J., & Alsan, M. (2020). Sociodemographic correlates of medical mistrust among African American men living in the East Bay. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved, 31(1), 115-127.

- Angelo, F., Veenstra, D., Knerr, S., & Devine, B. (2022). Prevalence and prediction of medical distrust in a diverse medical genomic research sample. Genetics in Medicine, 24(7), 1459-1467.

- Bazargan, M., Cobb, S., Assari, S., & Bazargan-Hejazi, S. (2022). Preparedness for serious illnesses: Impact of ethnicity, mistrust, perceived discrimination, and health communication. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®, 39(4), 461-471.

- Smith, A. C., Woerner, J., Perera, R., Haeny, A. M., & Cox, J. M. (2022). An investigation of associations between race, ethnicity, and past experiences of discrimination with medical mistrust and COVID-19 protective strategies. Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities, 9(4), 1430-1442.

- Carlisle, S. K. (2015). Perceived discrimination and chronic health in adults from nine ethnic subgroups in the USA. Ethnicity & Health, 20, 309–326. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, L. D., Smith, M. A., & Bigman, C. A. (2019). Does discrimination breed mistrust? Examining the role of mediated and non-mediated discrimination experiences in medical mistrust. Journal of health communication, 24(10), 791-799.

- Adams, V., & Craddock, J. (2023). Patient-provider communication quality as a predictor of medical mistrust among young Black women. Social work in public health, 38(4), 334-343.

- Chang, P. C., Wu, T., & Du, J. (2020). Psychological contract violation and patient’s antisocial behaviour: A moderated mediation model of patient trust and doctor-patient communication. International Journal of Conflict Management, 31(4), 647-664.

- Shapiro, D., & Hayburn, A. (2024). Medical gaslighting as a mechanism for medical trauma: case studies and analysis. Current Psychology, 43(45), 34747-34760.

- Fetters, A. (2018). The doctor doesn’t listen to her. But the media is starting to. The Atlantic.

- Au, L., Capotescu, C., Eyal, G., & Finestone, G. (2022). Long covid and medical gaslighting: Dismissal, delayed diagnosis, and deferred treatment. SSM-Qualitative Research in Health, 2, 100167.

- Heraclides, A., Hadjikou, A., Kouvari, K., Karanika, Ε., & Heraclidou, I. (2024). Low health literacy is associated with health-related institutional mistrust beyond education. European Journal of Public Health, 34(Supplement_3), ckae144-1683.

- Hartmann, M., & Müller, P. (2023). Acceptance and adherence to COVID-19 preventive measures are shaped predominantly by conspiracy beliefs, mistrust in science and fear–A comparison of more than 20 psychological variables. Psychological Reports, 126(4), 1742-1783.

- Pummerer, L. (2022). Belief in conspiracy theories and non-normative behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47, 101394.

- Ojikutu, B. O., Amutah-Onukagha, N., Mahoney, T. F., Tibbitt, C., Dale, S. D., Mayer, K. H., & Bogart, L. M. (2020). HIV-related mistrust (or HIV conspiracy theories) and willingness to use PrEP among Black women in the United States. AIDS and Behavior, 24, 2927-2934.

- Canales, M. K., Weiner, D., Samos, M., Wampler, N. S., Cunha, A., & Geer, B. (2011). Multi-generational perspectives on health, cancer, and biomedicine: Northeastern Native American perspectives shaped by mistrust. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved, 22(3), 894-911.

- Kincade, L. L., & Fox, C. A. (2022). “Runs in the family”: Fear of police violence and separation among Black families in central Alabama. Psychology of violence, 12(4), 221.

- Lee, M. J., Reddy, K., Chowdhury, J., Kumar, N., Clark, P. A., Ndao, P., ... & Song, S. (2018). Overcoming the legacy of mistrust: African Americans’ mistrust of medical profession. Journal of Healthcare Ethics and Administration, 4(1): 16-40.

- Whaley, A. L. (2001). Cultural mistrust: An important psychological construct for diagnosis and treatment of African Americans. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 32(6), 555.

- Ojikutu, B. O., Bogart, L. M., & Dong, L. (2022). Mistrust, empowerment, and structural change: lessons we should be learning from COVID-19. American Journal of Public Health, 112(3), 401-404.

- Williams, D. R., & Mohammed, S. A. (2013). Racism and health I: Pathways and scientific evidence. American behavioral scientist, 57(8), 1152-1173.

- Carlisle, B. L., & Murray, C. B. (2020). The role of cultural mistrust in health disparities. The Wiley Encyclopedia of Health Psychology, 43-50.

- Bailey, Z. D., Krieger, N., Agénor, M., Graves, J., Linos, N., & Bassett, M. T. (2017). Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. The lancet, 389(10077), 1453-1463.

- Yearby, R., Clark, B., & Figueroa, J. F. (2022). Structural Racism In Historical And Modern US Health Care Policy: Study examines structural racism in historical and modern US health care policy. Health Affairs, 41(2), 187-194.

- Walensky, R. P. (2021). Media statement from CDC Director Rochelle P. Walensky, MD, MPH, on racism and health: media statement: for immediate release: Thursday, April 8, 2021.

- Edgoose, J., Quiogue, M., & Sidhar, K. (2019). How to identify, understand, and unlearn implicit bias in patient care. Family practice management, 26(4), 29-33.

- Plaisime, M. V., Jipguep-Akhtar, M. C., & Belcher, H. M. (2023). ‘White People are the default’: A qualitative analysis of medical trainees' perceptions of cultural competency, medical culture, and racial bias. SSM-Qualitative Research in Health, 4, 100312.

- Hammond, W. P. (2010). Psychosocial correlates of medical mistrust among African American men. American journal of community psychology, 45, 87-106.

- Meghani, S. H., Brooks, J. M., Gipson-Jones, T., Waite, R., Whitfield-Harris, L., & Deatrick, J. A. (2009). Patient–provider race-concordance: does it matter in improving minority patients’ health outcomes?. Ethnicity & health, 14(1), 107-130.

- Jupic, T., Smylie, L., & Dubey, E. (2023). Physician/Patient Discordance. Urban Emergency Medicine, 110.

- Moore, C., Coates, E., Watson, A. R., de Heer, R., McLeod, A., & Prudhomme, A. (2023). “It’s important to work with people that look like me”: black patients’ preferences for patient-provider race concordance. Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities, 10(5), 2552-2564.

- Bilewicz, M. (2022). Conspiracy beliefs as an adaptation to historical trauma. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47, 101359.

- Cox, A. B., Jaiswal, J., LoSchiavo, C., Witte, T., Wind, S., Griffin, M., & Halkitis, P. N. (2023). Medical Mistrust Among a Racially and Ethnically Diverse Sample of Sexual Minority Men. LGBT health, 10(6), 471-479.

- Hill, M., Truszczynski, N., Newbold, J., Coffman, R., King, A., Brown, M. J., ... & Hansen, N. (2023). The mediating role of social support between HIV stigma and sexual orientation-based medical mistrust among newly HIV-diagnosed gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. AIDS care, 35(5), 696-704.

- Frost, D. M., & Meyer, I. H. (2023). Minority stress theory: Application, critique, and continued relevance. Current Opinion in Psychology, 51, 101579.

- Kano, M., Jaffe, S. A., Rieder, S., Kosich, M., Guest, D. D., Burgess, E., ... & Myaskovsky, L. (2022). Improving sexual and gender minority cancer care: patient and caregiver perspectives from a multi-methods pilot study. Frontiers in Oncology, 12, 833195.

- Phillips, G., Xu, J., Cortez, A., Curtis, M. G., Curry, C., Ruprecht, M. M., & Davoudpour, S. (2024). Influence of Medical Mistrust on Prevention Behavior and Decision-Making Among Minoritized Youth and Young Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 1-11.

- Dale, S. K., Bogart, L. M., Wagner, G. J., Galvan, F. H., & Klein, D. J. (2016). Medical mistrust is related to lower longitudinal medication adherence among African-American males with HIV. Journal of health psychology, 21(7), 1311-1321.

- Galvan, F. H., Bogart, L. M., Klein, D. J., Wagner, G. J., & Chen, Y. T. (2017). Medical mistrust as a key mediator in the association between perceived discrimination and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive Latino men. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 40(5), 784-793.

- Greer, T. M., Brondolo, E., & Brown, P. (2014). Systemic racism moderates effects of provider racial biases on adherence to hypertension treatment for African Americans. Health Psychology, 33, 35-42. [CrossRef]

- Hamoda, R., McPherson, L., Lipford, K., Arriola, K., Plantinga, L., Gander, J., Hartmann, E., Mulloy, L., Zayas, C., Lee., K., Pastan, S., Patzer, R. E. (2020). Association of sociocultural factors with initiation of the kidney transplant evaluation process. American Journal of Transplantation, 20(1), 190-203.

- Kalichman, S. C., Eaton, L., Kalichman, M. O., Grebler, T., Merely, C., & Welles, B. (2016). Race-based medical mistrust, medication beliefs and HIV treatment adherence: test of a mediation model in people living with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 39, 1056-1064. [CrossRef]

- Pellowski, J. A., Price, D. M., Allen, A. M., Eaton, L. A., & Kalichman, S. C. (2017). The differences between medical trust and mistrust and their respective influences on medication beliefs and ART adherence among African-Americans living with HIV. Psychology & health, 32(9), 1127-1139.

- Matthew, D. B. (2018). Just medicine: A cure for racial inequality in American health care. NYU Press.

- Sommers, B. D., Gawande, A. A., & Baicker, K. (2017). Health insurance coverage and health— what the recent evidence tells us. New England Journal of Medicine,377(6),586-593.

- Thrasher, A. D., Earp, J. A. L., Golin, C. E., & Zimmer, C. R. (2008). Discrimination, distrust, and racial/ethnic disparities in antiretroviral therapy adherence among a national sample of HIV-infected patients. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 49, 84-93. [CrossRef]

- Durant, R. W., Legedza, A. T., Marcantonio, E. R., Freeman, M. B., & Landon, B. E. (2011). Different types of distrust in clinical research among whites and African Americans. Journal of the National Medical Association, 103(2), 123-130.

- Klonoff, E. A. (2009). Disparities in the provision of medical care: an outcome in search of an explanation. Journal of behavioral medicine, 32(1), 48-63.

- Paradies, Y., Ben, J., Denson, N., Elias, A., Priest, N., Pieterse, A., . . . Gee, G. (2015). Racism as a determinant of health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One, 10, 1-48. [CrossRef]

- Peek, M. E., Odoms-Young, A., Quinn, M. T., Gorawara-Bhat, R., Wilson, S. C., & Chin, M. H. (2010). Racism in healthcare: its relationship to shared decision-making and health disparities: a response to Bradby. Social science & medicine (1982), 71(1), 13.

- Vina, E. R., Hausmann, L. R., Utset, T. O., Masi, C. M., Liang, K. P., & Kwoh, C. K. (2015). Perceptions of racism in healthcare among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a cross-sectional study. Lupus science & medicine, 2(1), e000110.

- Nelson, A. R., Stith, A. Y., & Smedley, B. D. (2002). Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Jacobs, J., Walsh, J. L., Valencia, J., DiFranceisco, W., Hirschtick, J. L., Hunt, B. R., ... & Benjamins, M. R. (2024). Associations Between Religiosity and Medical Mistrust: An Age-Stratified Analysis of Survey Data from Black Adults in Chicago. Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities, 1-9.

- Henderson, D. X., Walker, L., Barnes, R. R., Lunsford, A., Edwards, C., & Clark, C. (2019). A framework for race-related trauma in the public education system and implications on health for black youth. Journal of school health, 89(11), 926-933.

- Omodei M., McLennan, J. (2000). Conceptualizing and measuring global interpersonal mistrust-trust, Journal of Social Psychology, 140:279–294.

- Pearson, S. D., & Raeke, L. H. (2000). Patients’ trust in physicians: many theories, few measures, and little data. Journal of general internal medicine, 15(7), 509-513.

- Shelton, R. C., Winkel, G., Davis, S. N., Roberts, N., Valdimarsdottir, H., Hall, S. J., & Thompson, H. S. (2010). Validation of the group-based medical mistrust scale among urban black men. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25(6), 549-555.

- Brown, M. T., & Bussell, J. K. (2011, April). Medication adherence: WHO cares?. In Mayo clinic proceedings (Vol. 86, No. 4, pp. 304-314). Elsevier.

- Aspiras, O., Hutchings, H., Dawadi, A., Wang, A., Poisson, L., Okereke, I. C., & Lucas, T. (2024). Medical mistrust and receptivity to lung cancer screening among African American and white American smokers. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 1-12.

- Jaffee, K., Cohen, M., Azaiza, F., Hammad, A., Hamade, H., & Thompson, H. (2021). Cultural barriers to breast cancer screening and medical mistrust among Arab American women. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 23, 95-102.

- Henderson, R. C., Williams, P., Gabbidon, J., Farrelly, S., Schauman, O., Hatch, S., ... & MIRIAD Study Group. (2015). Mistrust of mental health services: ethnicity, hospital admission and unfair treatment. Epidemiology and psychiatric sciences, 24(3), 258-265.

- Kinlock, B. L., Thorpe Jr, R. J., Howard, D. L., Bowie, J. V., Ross, L. E., Fakunle, D. O., & LaVeist, T. A. (2016). Racial disparity in time between first diagnosis and initial treatment of prostate cancer.

- Simon, M. A., Tom, L. S., Nonzee, N. J., Murphy, K. R., Endress, R., Dong, X., & Feinglass, J. (2015). Evaluating a bilingual patient navigation program for uninsured women with abnormal screening tests for breast and cervical cancer: implications for future navigator research. American journal of public health, 105(5), e87-e94.

- Zhang, C., McMahon, J., Leblanc, N., Braksmajer, A., Crean, H. F., & Alcena-Stiner, D. (2020). Association of medical mistrust and poor communication with HIV-related health outcomes and psychosocial wellbeing among heterosexual men living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 34(1), 27-37.

- Leonard, S. I., Pizii, C. T., Zhao, Y., Céspedes, A., Kingston, S., & Bruzzese, J. M. (2024). Group-Based Medical Mistrust in Adolescents With Poorly Controlled Asthma Living in Rural Areas. Health Promotion Practice, 25(5), 758-762.

- Egede, L. E., & Michel, Y. (2006). Medical mistrust, diabetes self-management, and glycemic control in an indigent population with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 29(1).

- Jiang, Y. (2016). Beliefs in chemotherapy and knowledge of cancer and treatment among African American women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Number 2/March 2016, 43(2), 180-189.

- Maly, R. C., Stein, J. A., Umezawa, Y., Leake, B., & Anglin, M. D. (2008). Racial/ethnic differences in breast cancer outcomes among older patients: effects of physician communication and patient empowerment. Health Psychology, 27(6), 728.

- Guadagnolo, Kristin Cina, Petra Helbig, Kevin Molloy, Mary Reiner, E. Francis Cook, & Daniel G. Petereit. (2008). Medical Mistrust and Less Satisfaction With Health Care Among Native Americans Presenting for Cancer Treatment. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 20(1), 210–226. [CrossRef]

- Molina, Y., Kim, S., Berrios, N., & Calhoun, E. A. (2015). Medical mistrust and patient satisfaction with mammography: the mediating effects of perceived self-efficacy among navigated African American women. Health Expectations, 18(6), 2941-2950.

- Kutnick, A. H., Leonard, N. R., & Gwadz, M. V. (2019). “Like I have no choice”: a qualitative exploration of HIV diagnosis and medical care experiences while incarcerated and their effects. Behavioral Medicine, 45(2), 153-165.

- Batova, T. (2022). To wear or not to wear: a commentary on mistrust in public comments to CDC tweets about mask-wearing during COVID19. International Journal of Business Communication, 59(2), 287-308.

- Featherstone, J. D., & Zhang, J. (2020). Feeling angry: the effects of vaccine misinformation and refutational messages on negative emotions and vaccination attitude. Journal of Health Communication, 25(9), 692-702.

- Relf, M. V., Pan, W., Edmonds, A., Ramirez, C., Amarasekara, S., & Adimora, A. A. (2019). Discrimination, medical distrust, stigma, depressive symptoms, antiretroviral medication adherence, engagement in care, and quality of life among women living with HIV in North Carolina: A mediated structural equation model. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 81(3), 328-335.

- Sheppard, V. B., Harper, F. W., Davis, K., Hirpa, F., & Makambi, K. (2014). The importance of contextual factors and age in association with anxiety and depression in Black breast cancer patients. Psycho-oncology, 23(2), 143-150.

- Stimpson, J. P., Park, S., Wilson, F. A., & Ortega, A. N. (2024). Variations in Unmet Health Care Needs by Perceptions of Social Media Health Mis-and Disinformation, Frequency of Social Media Use, Medical Trust, and Medical Care Discrimination: Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR public health and surveillance, 10(1), e56881.

- Ayers, J. W., Poliak, A., Dredze, M., Leas, E. C., Zhu, Z., Kelley, J. B., ... & Smith, D. M. (2023). Comparing physician and artificial intelligence chatbot responses to patient questions posted to a public social media forum. JAMA internal medicine, 183(6), 589-596.

- Chen, J., & Wang, Y. (2021). Social media use for health purposes: systematic review. Journal of medical Internet research, 23(5), e17917.

- Neely, S., Eldredge, C., & Sanders, R. (2021). Health information seeking behaviors on social media during the COVID-19 pandemic among American social networking site users: survey study. Journal of medical Internet research, 23(6), e29802.

- Chou WS, Oh A, Klein WMP. Addressing Health-Related Misinformation on Social Media. JAMA. 2018 Dec 18;320(23):2417-2418. [CrossRef]

- Vosoughi S, Roy D, Aral S. The spread of true and false news online. Science. 2018 Mar 9;359(6380):1146-1151. [CrossRef]

- Naeem, S. B., Bhatti, R., & Khan, A. (2021). An exploration of how fake news is taking over social media and putting public health at risk. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 38(2), 143-149.

- Harper, D. J. (2011). Social inequality and the diagnosis of paranoia. Health Sociology Review, 20(4), 423-436.

- Rastegar, P. J., & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J. (2024, May). Understanding College Students’ Healthcare Avoidance: From Early Maladaptive Schemas, through Healthcare Institutional Betrayal and Betrayal Trauma Appraisal of Worst Healthcare Experiences. In Healthcare (Vol. 12, No. 11, p. 1126). MDPI.

- Underhill, K., Morrow, K. M., Colleran, C., Holcomb, R., Calabrese, S. K., Operario, D., ... & Mayer, K. H. (2015). A qualitative study of medical mistrust, perceived discrimination, and risk behavior disclosure to clinicians by US male sex workers and other men who have sex with men: implications for biomedical HIV prevention. Journal of Urban Health, 92, 667-686.

- Dahlem, C. H. Y., Villarruel, A. M., & Ronis, D. L. (2014). African American Women and Prenatal Care. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 37(2), 217–235. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).