1. Introduction

Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) has been proved to be safe with many advantages to treatment. On other hands glioma tumor treatment is a major neuro-oncological problem. To date, the exact cellular mechanism of PDT in cancer treatment is still unclear. However, currently we know that PDT has three

singlet oxygen (1O

2)

. PS should be non-mutagenic and have a stronger absorption in the region (650–800 nm) to allow increased light penetration in human tissue [

1]

. In this article, we are trying to explore the current knowledge on the relationship between PDT and genetic changes in glioma treatment (

Figure 1).

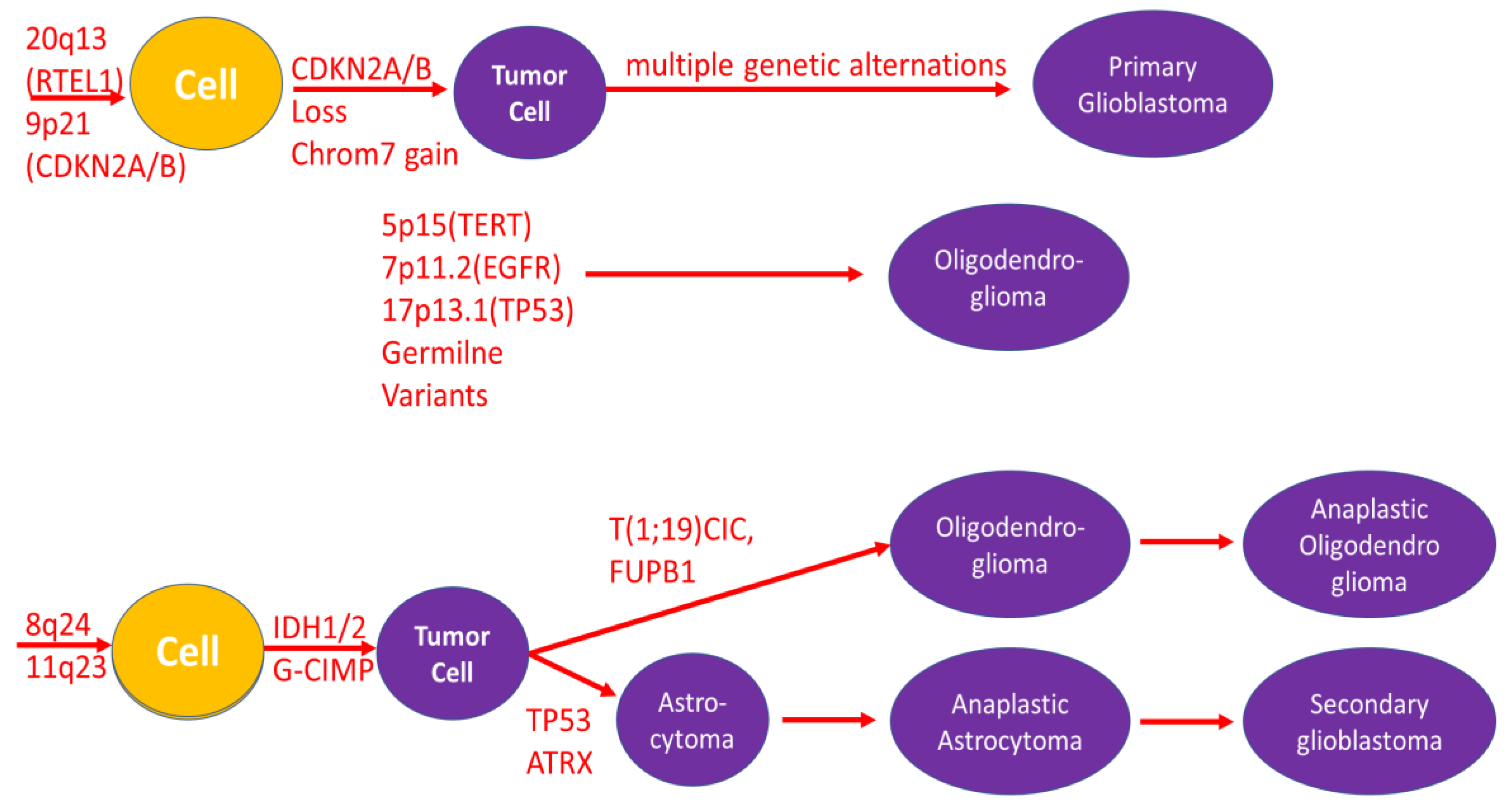

In the 2009, the first gene expression analysis and genome association studies concerning several loci associated with glioma have been discovered [

2,

3] (

Figure 2).

The 8q24 genetic variant has been associated with the risk of several types of cancer. The mechanism by which the 8q24 genetic variant increases the risk of glioma is unknown. Genetic testing of the tumor serves to properly qualify but is also a prognostic factor. The number of tests performed indicates how complex and complicated the process of genetic diagnostics of gliomas is. A number of genetic tests are performed, such as: p53 gene mutation, loss of heterozygosity (9q, 10p, 10q, 13 q, 17q, 19q, 22q), chromosomal deletions or amplifications of DNA fragments encoding genes: PTEN, CDK4, CDK6, EGFR, MDM2, MGMT mutations, IDH1 mutation, IDH2 mutation. In 2005 Malmer et al. observed an association of a specific p53 haplotype and glioma. Among the most frequently performed genetic tests, low expression of EGFR, p-53 protein, IDH-1 and IDH-2 mutations, and MGMT mutations have a favorable prognosis. According to the current new classification, to classify a tumor as oligodendroglioma, there must be confirmation of the 1p19q codeletion. 2005 Malmer et al. observed an association of a specific p53 haplotype and glioma [

4].

Genetic testing of the tumor includes tests such as:

loss of heterozygosity (9q, 10p, 10q, 13 q, 17q, 19q, 22q) [

6],

chromosomal deletions or amplifications of DNA fragments encoding the following genes: PTEN, CDK4, CDK6, EGFR, MDM2 [

7],

IDH1 [

9] and IDH2 mutation [

10],

IDH-1 [

12] and IDH-2 mutation [

13].

In this oaper we review the effects of photodynamic therapy and genetically determined glioma syndromes associated with an increased risk of disease.

2. Gene Expression Analysis

Gene expression analysis indicating the presence of MGMT mutations promotes better tumor susceptibility to chemotherapy [

14]. Loss of heterozygosity in chromosomes 9p and 10q and deletion of 16p are observed in high-grade gliomas. Genome sites that promote susceptibility to glioma have been identified. Innovative therapies give hope for curing gliomas. A number of clinical trials are being conducted using new targeted therapies and immunotherapy. Brain tumors and other tumors of the central nervous system (CNS) are a significant problem associated with significant mortality and morbidity at all ages. They are the most common group of cancers diagnosed in children aged 0-14 and the second most common cancer in the age group 15-19. Most of these tumors are malignant (3.55 per 100,000), the most common of which are glioma, embryonal tumors and germ cell tumors. In turn, pituitary gland tumor is the most common among non-malignant brain tumors and other CNS tumors, occurring at a frequency of 2.6 per 100,000. In all adults (over 20 years of age), benign lesions are more common (22.38 per 100,000) than malignant lesions (8.5 per 100,000) [

15,

16].

Brain tumors and other CNS tumors constitute a very complex and extensive group of tumors. The classification according to The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System includes 12 main groups: 1. Gliomas, glioneuronal tumors, and neuronal tumors; 2. Choroid plexus tumors; 3. Embryonal tumors; 4. Pineal tumors; 5. Cranial and paraspinal nerve tumors; 6. Meningiomas; 7. Mesenchymal, non-meningothelial tumors; 8. Melanocytic tumors; 9. Hematolymphoid tumors; 10. Germ cell tumors; 11. Tumors of the sellar region and 12. Metastases to the CNS [

17].

In patients diagnosed with glioma, the most frequently assessed genes are carcinogen metabolism and immune function genes, because of their probable association with carcinogenesis or because of the persistently observed association between allergies and glioma. Although promising results have been obtained, as indicated below, in a few studies performed on any polymorphisms to ensure consistency. Inherited variation in DNA repair represents a major category of genes widely studied in cancer because of their importance in maintaining genomic integrity. Glioma and/or glioma subtypes were significantly associated with variants in ERCC1, ERCC2, the nearby gene GLTSCR1 (a candidate glioma tumor suppressor of unknown function), PRKDC (also known as XRCC7), MGMT, and most recently CHAF1A.

Separation of analyses for cases with a family history showed support for an association with the RTEL gene in cases with a family history of brain tumors [

18].

To the the syndromes predisposing to the development of glioma beongs: Li-Fraumeni band (LFS) [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]; Lynch syndrome (HNPCC) [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]; Tuberous sclerosis syndrome (

Tuberous Sclerosis Complex; TSC) [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]; Neurofibromatosis type syndrome 1 (NF1) [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]; neurofibromatosis type syndrome 2 (NF2) [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]; and Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome (VHL) [

21,

22]. Below we described mentioned syndromes.

2.1. Li-Fraumeni Band (LFS)

Li-Fraumeni syndrome is a rare disease inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. It was first described by Li and Fraumeni in 1969 [

24]. LFS is a cancer predisposition syndrome associated with a high risk of malignant tumors. This risk, over the lifetime of a person affected by LFS, is at least 70% for men and at least 90% for women [

25]. According to other authors, the incidence of developing at least one cancer at the age of 30 is 50%, while at the age of 70 it is close to 100% [

24]. There are five types of cancer to which these patients are particularly vulnerable: adrenocortical carcinomas, breast cancer, central nervous system tumors, osteosarcomas, and soft-tissue sarcomas [

24,

25]. It is necessary to confirm all three classic clinical criteria to confirm LFS: (1) proband with sarcoma diagnosed before the age of 45; (2) a first-degree relative diagnosed with cancer before age 45; (3) a first- or second-degree relative diagnosed with cancer before age 45 or sarcoma diagnosed at any age. An additional diagnostic criterion, but not required, is the demonstration of a heterozygous germline pathogenic variant in TP53, which occurs in 60-80% of patients [

24,

25]. In 40% of patients with a phenotype similar to Li-Fraumeni syndrome (Li–Fraumeni-like - LFL), the presence of harmful TP53 mutations was confirmed. These mutations are located mainly in the DNA-binding domain. It has also been shown that mutations in the cell cycle checkpoint gene CHEK2, without detectable TP53 mutations, may also predispose to the development of LFS or LFL in some families. The literature also indicates that mutations in POT1 are associated with the development of several types of cancer in LFL families [

26]. The incidence of brain cancer up to the age of 70 is 6% in women and 19% in men. Approximately 10% of LFS patients will develop a glioma (astrocytoma or glioblastoma multiforme) [

25,

27].

2.2. Lynch Syndrome (LS)

Lynch syndrome (LS; otherwise known as Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer - HNPCC syndrome) is an autosomal dominant disease, the essence of which is the loss of function in one of four different genes encoding mismatch repair proteins [

28]. LS is caused by the presence of pathogenic germline variants (PGV) in any of the 4 DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2, or deletions in EPCAM. [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. The consequence is the potential development of cancers related primarily to the digestive tract and gynecological organs, i.e. large intestine (CRC) and endometrium (EC) [

28,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Lynch syndrome is the most common form of hereditary predisposition to colorectal cancer. It affects approximately 3% of patients with colorectal cancer and approximately 2-6% of patients with endometrial cancer (according to various sources). [

34,

36] The lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer in patients affected by LS is 50-80%, and endometrial cancer is 40-60%. [

35] These patients also have cancer of the upper urinary tract, hepatobiliary tract, small intestine, ovary, skin, pancreas and brain. [

33,

36] The first case report of the family, later called "Family G," dates back to 1913, when Dr. Aldred Scott Warthin, a pathologist at the University of Michigan, noticed a distinct susceptibility to developing certain types of cancer.

Then, in 1966, cases of two large families suffering from colon, stomach and endometrial cancer were described by Dr. Henry Lynch, after whom the syndrome was named in 1984. There are Lynch I and Lynch II syndromes, which, unlike the first syndrome, are characterized by additional tumors apart from the colorectal cancer. A little later, the term "hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer" (HNPCC) was proposed, which suggested a lack of connection with the classic form of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). [

33] The diagnosis of LS is based on the Amsterdam and Bethesda criteria, related primarily to the history of cancer in the patient and his family. Cancer diagnosis is performed using two techniques. Using immunohistochemistry, the expression of MMR proteins can be examined, while molecular biology methods are helpful in determining the occurrence of microsatellite DNA instability. [

34] There are three varieties of Lynch syndrome, i.e. Turcot's syndrome, Muir–Torre syndrome and constitutional MMR deficiency (CMMR-D) syndrome, which may occur simultaneously in one patient. [

35]

Lynch syndrome is associated with a four-fold increased risk of brain tumors, primarily the development of glioblastoma multiforme. Type I Turcot syndrome predisposes to the development of gliomas and astrocytomas, and type II Turcot syndrome may cause medulloblastomas. Muir–Torre syndrome and CMMR-D syndrome are also characterized by a higher incidence of brain tumors, including gliomas, compared to the general population. According to research, among patients suffering from Lynch syndrome, 14% of families were diagnosed with primary brain tumors. The most common histological subtype was glioblastoma multiforme (56%), followed by astrocytoma in 22% of cases and oligodendroglioma in 9%. The median age at diagnosis was 42 years. [

35] For the prevention of central nervous system and brain tumors in people with LS, no additional monitoring beyond an annual physical/neurological examination beginning at age 25–30 is currently recommended. [

37] Temozolomide (TMZ) is recommended as a standard treatment option for gliomas, and it works by inducing DNA damage through guanine and adenine methylation. This process initiates a futile cycle of mismatch repair, causing lethal double-strand breaks leading to checkpoint activation and apoptosis. Given the dependence of the effectiveness of TMZ and other alkylating agents on the repair of functional mismatches, MMR-deficient cells are inherently more resistant to their effects and may survive at the cost of extensive mutagenesis. Preliminary studies indicate potential resistance to TMZ in cells from glioma patients. [

31] Further research is needed to find the most effective treatment.

3. Selected Neurocutaneous Diseases

Neurocutaneous diseases include primarily tuberous sclerosis syndrome (TSC), neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), neurofibromatosis type II (NF2) and von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL). [

38,

39]

3.1. Tuberous Sclerosis Syndrome (TSC) and Gliomas in TSC

Tuberous sclerosis syndrome is an autosomal dominant neurocutaneous disease that was first mentioned in 1880-1900. The relationship between changes in the brain and skin symptoms on the face was then described. At that time, a characteristic triad of symptoms was also described - Vogt's triad: sebaceous adenoma, epilepsy and mental retardation, which is a loose definition of TSC. [

39,

40] The incidence of TSC is 1 in 6,000-10,000 live births. [

39,

40] Tuberous sclerosis syndrome is caused by a mutation in the TSC1 or TSC2 gene, which occurs de novo in 80% of cases. Among these cases, mutations in the TSC2 gene are observed approximately 4 times more often than mutations in TSC1. It was noticed that the frequency of both types of mutations is the same among familial cases. [

39,

40]

Patients with TSC are at increased risk of developing tumors of the central nervous system. Cortical tubes, usually in the form of benign hemartomas, which are detected in 95% of patients, are the most characteristic neuropathological and pathognomonic feature of tuberous sclerosis of the brain. They show dysplastic neurons along with eosinophilic giant cells of mixed neuronal lineage. Subependymal nodules are also hamartomatous lesions located along the walls of the lateral ventricles. Subependymal giant cell astrocytomas are slow-growing tumors that are the most common brain tumor in patients with TSC. They are found in approximately 6-14% of patients, usually in the first 2 decades of life. Neuroimaging studies and the presence of hydrocephalus are used to differentiate a giant cell subependymal astrocytoma from a subependymal nodule. To prevent the development of subependymal giant cell astrocytoma, it is recommended to perform follow-up MRI examinations every 1-3 years. Treatment of brain tumors in the course of TSC is mainly based on surgical resection of the lesions and targeted therapy using mTOR inhibitors, e.g. everolimus. Surgery, as the therapy of choice, is necessary in the event of symptoms related to the mass of the tumor, such as obstructive hydrocephalus, swollen papillae, increased intracranial pressure, but also when radiological progression of the tumor is noted or when new focal neurological deficits appear. Everolimus has been shown to be effective in patients with subependymal giant cell astrocytomas associated with TSC. This therapy is recommended in patients who are not good candidates for surgery or in cases of asymptomatic disease with a constantly enlarging lesion.

Further research is necessary to prove the preliminary results of treatment [

39]. Neurofibromatosis (Neurofibromatosis syndrome types 1 and 2; NF1 and NF2). Neurofibromatosis is a neurocutaneous disease characterized by the development of tumors of the central or peripheral nervous system, including the brain, spinal cord, organs, skin and bones. There are three types of neurofibromatosis, the most common of which is type 1 (NF1), accounting for 96% of cases, type 2 (NF2) is diagnosed in 3%, and schwannomatosis (SWN) in <1% [

41].

3.2. Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1) and Gliomas in NF1

Neurofibromatosis type 1 is caused by a mutation in the NF1 gene, which is located on chromosome 17q11.2. [

39,

41]. There are over 500 known mutations in the NF1 gene [

39,

41].

In 90% of cases, these are point mutations, while deletion of a single exon or the entire NF1 gene is responsible for the remaining 5-7% [

41]. The neurofibromatosis type 1 gene encodes neurofibromin, which is a protein that activates Ras-GTPase, thereby interrupting Ras signaling. NF1 protein deficiency results in hyperactivation of Ras, leading to subsequent activation of many important pathways. Neurofibromin is produced in neurons, oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells and other types of non-neuronal cells. The non-functional protein affects the growth of neurofibromas along nerves throughout the body [

39,

41].

Neurofibromatosis type 1 is associated with an increased risk of developing many types of cancer, including those affecting the nervous system, which constitute a significant proportion of malignancies. The most common intracranial tumors include optic gliomas, diagnosed in 15-20% of patients with NF1, and brain stem gliomas. It is believed that these tumors have a milder course than in patients without cancer predisposition syndromes, which may even regress. Most of them are asymptomatic and do not require treatment or biopsy. The main therapeutic method for tumors not related to the optic pathway is surgery, which is unfortunately limited due to the possibility of regrowth of the lesion. For patients with optic glioma, the treatment of choice is conservative treatment with follow-up imaging or chemotherapy with carboplatin and vincristine, and surgical resection is used for tumors that have an atypical appearance, are associated with hydrocephalus, or are associated with complete loss of vision in one eye. In patients who have progressed after using other therapeutic options, radiotherapy is recommended, but is limited due to the fear of the development of a secondary tumor or malignant transformation. The possible effectiveness of targeted therapy directed at the pathogenic molecular pathway of neurofibromatosis type 1 is indicated, but there is still insufficient research on the most effective therapeutic strategy. Diagnostic MRI screening is not recommended in asymptomatic patients [

39].

3.3. Neurofibromatosis Type 2 (NF2) and Gliomas in NF2

Neurofibromatosis type 2, like schwannomatosis, originates from Schwann cells and leads to an increased susceptibility to the development of tumors of the nervous system [

39].

The most frequently observed lesions in the central nervous system are bilateral vestibular schwannomas, which occur in 90-95% of patients under 30 years of age. Also characteristic are intramedullary and extramedullary tumors of the spine (63-90%), intracranial meningiomas (45-71%), and neuromas of other cranial nerves (24-51%) [

39]. Currently, there is no most effective therapeutic option for patients with NF2. The most important goal of treatment in patients with NF2 is to preserve hearing function and improve quality of life [

39] .The simultaneous occurrence of multiple intracranial tumors indicates the advantage of conservative treatment. [

39] Additional treatment is usually necessary when neurological changes occur and there is a risk of brain stem compression, hearing loss or facial nerve dysfunction. [

39,

41] Surgical intervention is the primary treatment method, but there is a high probability of tumor regrowth. Radiosurgery is being used more and more often, but it may be associated with vestibular dysfunction and trigeminal neuropathy. Malignant transformation after using this method is very rare. [

41] The use of radiotherapy may contribute to the secondary development of cancer, therefore its use is not recommended in patients with NF2. [

39] Recent research reports the benefits of using targeted therapies that target the molecular pathways that control cell growth. The latest reports indicate the monoclonal antibody bevacizumab as the first-line drug in the treatment of rapidly growing vestibular schwannomas. [

39,

41]

3.4. Von Hippel-Lindau Syndrome (VHL)

Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome (VHL) is a multi-system autosomal dominant disease that predisposes to the development of benign and malignant tumors of the central nervous system and visceral organs [

39,

42,

43,

44] In approximately 80% of cases, VHL is hereditary, and in 20% of cases the mutation occurs de novo. [

44] The most characteristic type of cancer for VHL, developing in approximately 50% of patients, is hemangioblastoma, which originates from the blood vessels as a benign lesion. This tumor may occur both in the central nervous system (CNS hemangioblastoma; CNS-H) - in the brain and spinal cord, as well as in the retina (retinal hemangioblastoma; RH). Depending on the location, it may cause different symptoms. Retinal hemangioblastomas may present with loss of vision, cerebellar hemangioblastomas with headaches, vomiting, gait disturbances or ataxia, and spinal hemangioblastomas and related syrinx with pain. Typical kidney diseases are cysts and renal cell carcinoma (RCC), occurring in approximately 70% of patients with VHL, which is the main cause of mortality. [

43,

44]

Typical symptoms of VHL also include pheochromocytoma (PCC), which may cause hypertension or be asymptomatic, and changes in the pancreas (pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors or cystadenomas), inner ear and genital tract (cysts and/or cystadenomas of epididymis and cysts and /or cystadenomas of broad ligament). [

32,

33] Due to the genotype-phenotype correlation and the incidence of PCC, VHL is divided into type 1 and type 2. Type 1 VHL is caused by truncating mutations or exon deletions. It is characterized mainly by the occurrence of RH, CNS-H, RCC, with a low risk of developing PCC. Type 2 VHL, characterized by PCC, is caused by a missense mutation. Type 2 is divided into three further subtypes (2A, 2B and 2C), differing in the incidence of CNS-H, RH and RCC tumors. [

43,

44,

45] The diagnosis is based on the diagnosis of tumors characteristic of this syndrome in patients with or without a positive family history of VHL. [

39]

The most common lesions in the central nervous system in people with VHL are undoubtedly hemangioblastoma. Available studies show that these patients may also develop low-grade or pilocytic astrocytomas. [

46] Surgical resection is recommended for the treatment of CNS tumors. The use of targeted therapies is under research. [

43,

44] Screening to detect VHL-related tumors at an early stage of development includes frequent general physical and neurological examinations, regular dilated eye examinations, audiological evaluation, CNS and systemic imaging, and laboratory tests. [

45]

4. Glioma Treatmet

These cancer susceptibility syndromes are associated with only a small minority of familial gliomas, suggesting the presence of additional predisposing genes. [

19]

Genetic studies provide useful, often more complete information on prognostic factors from cases. However, it is still unfortunate that most adult patients do not have access to clinical trials. The disadvantage is that pathological diagnoses vary greatly depending on the neuropathologist, the time and place of diagnosis, and the diagnostic criteria used [

47,

48].

The treatment of gliomas, due to their very poor prognosis, has been the subject of discussion since the 1980s.[

45,

48]. The current therapeutic standard includes surgical resection combined with radiochemotherapy [

48]. The first research results using photodynamic therapy in the treatment of gliomas bring promising results. It was noticed that the use of photodynamic therapy in combination with surgery prolongs the patient's survival time compared to tumor resection alone [

45,

49,

50]. Muller and Willson showed that the median survival in patients who additionally received PDT was 11 months, which means an extension of survival by 3 months compared to patients who did not receive this therapy [

50].

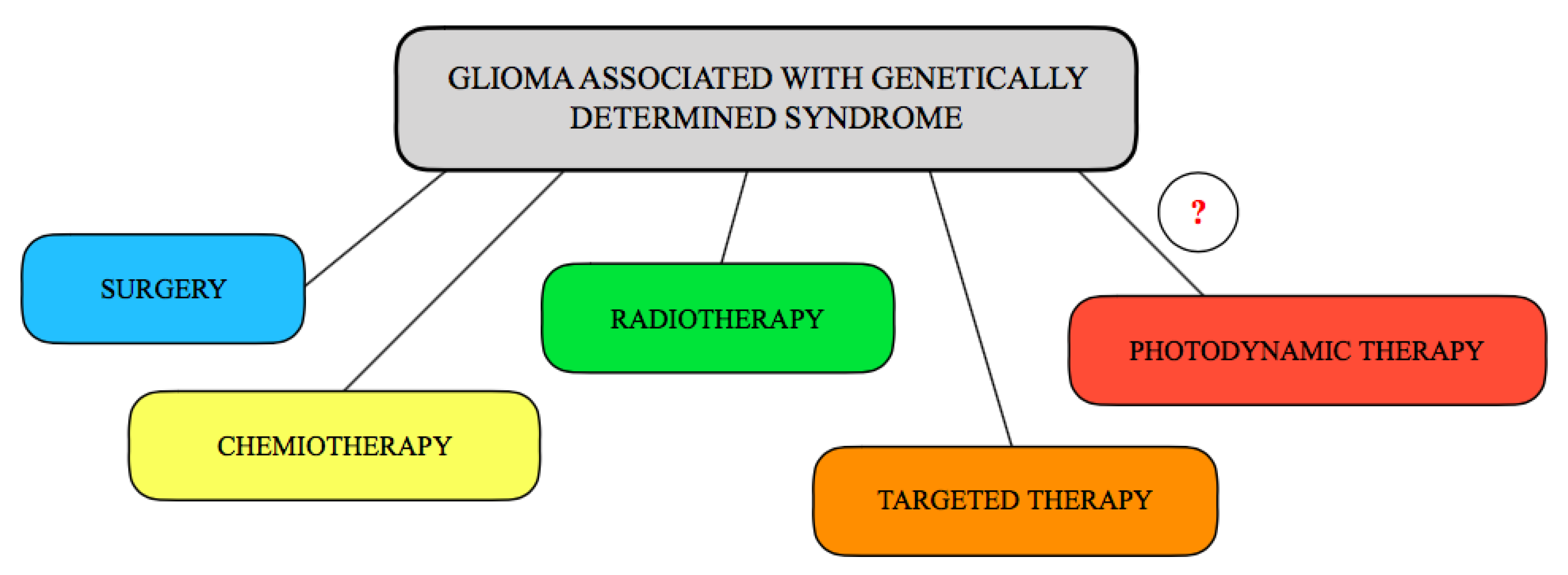

This review provides an overview of genetic alterations in glioma, their impact on antibody and biomarker expression, and the future design of antiglioma therapies. Glioma is the most frequently diagnosed and least prognostic tumor of the central nervous system. It is already stage IV at diagnosis, and the median survival time with current treatment techniques is several months. Current variants for the treatment of glioma are presented in

Figure 3 and includes surgery, chemiotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy and being to consider the use of photodynamic therapy.

5. Photodynamic Therapy

It is known that a combination of photochemical and photobiological processes occurred during PDT leads to the eventual selective destruction of tumor cells. In the case of cancer disease, to better understand the molecular mechanism of photosensitizer in PDT treatment, microarray analysis is also used to help identify genes that may contribute to the response to PDT treatment. To date, very few microarray studies have been conducted on in PDT response to cancer treatment. However, the change of gene expression was observed in A431 squamous cell carcinoma cell, RT4 urothelial carcinoma cell, HT29 colon cancer cell or Ca9-22 gingival cancer cell before and after PDT [

51,

52]. All these published studies [

51,

52] focused on the gene expression induced by PDT in cell cultures. Thus, further in vivo analysis should be performed.

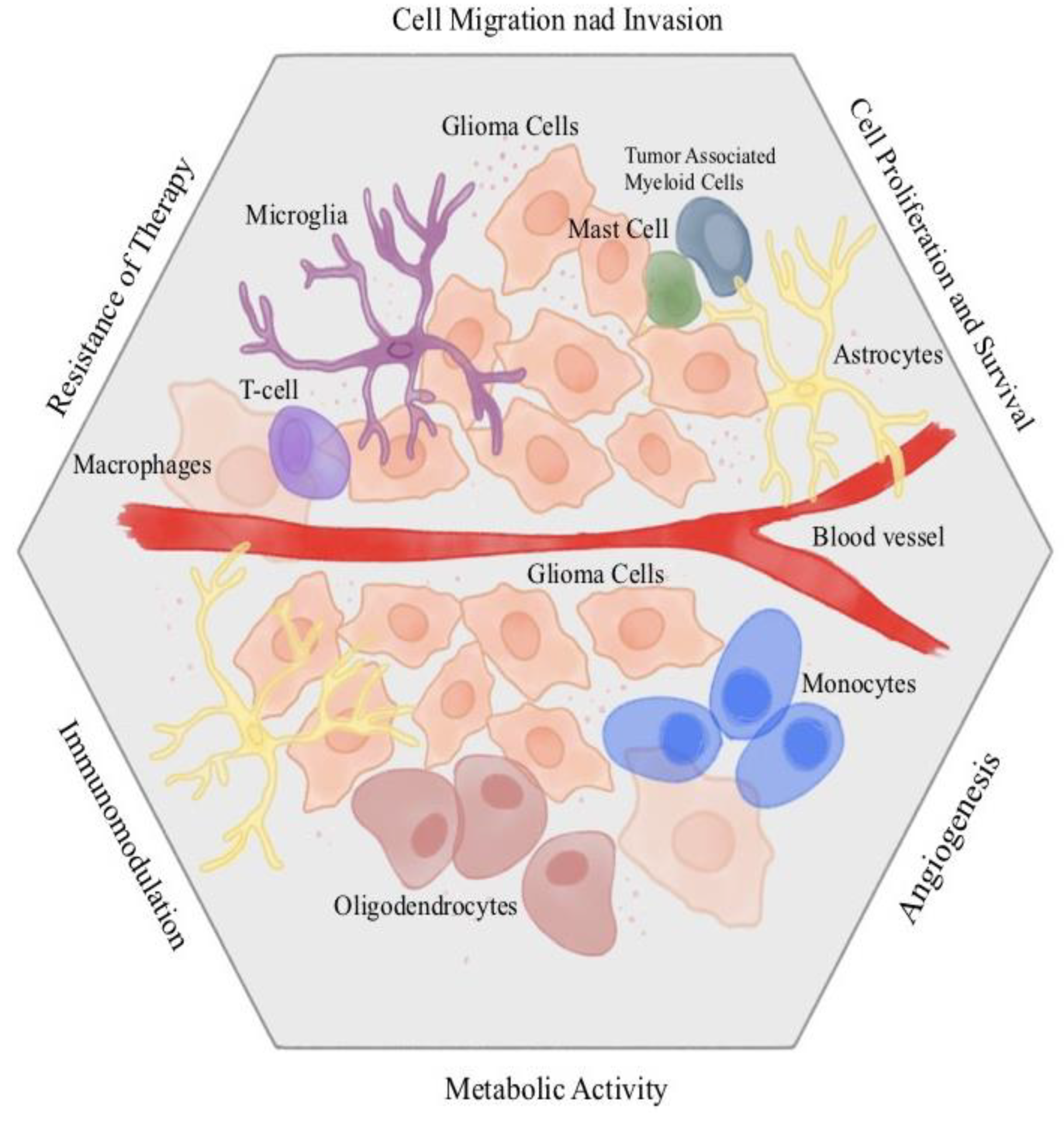

Understanding the molecular interactions between glioma tumors, host immune cells, and the tumor microenvironment may lead to new, integrated approaches to simultaneously control tumor escape pathways and activate antitumor immune responses (

Figure 4). Glioma cells-brain microenvironment interactions have usually mainly focused on astrocyte-derived growth factors and metalloproteinases that facilitate glioma invasion,pro-inflammatory cytokines involved in immunosuppression (e.g., TGF-b), or gap junction

Gene expression analysis is increasingly used to understand the impact of therapeutic methods on the molecular mechanism of diseases. This approach is associated with increasing the effectiveness of treatment and reducing the side effects of treatment [

53]. Gene expression analysis is attracted the attention of researchers to help to monitor and develop a new therapeutic methods. PDT, like other methods, is assessed by gene expression analysis. The expression of many genes changes in response to PDT [

4]. PDT is a therapeutic method whose action is based on the interaction between dye, light and oxygen (

Figure 5). [

54,

55]

The first literature reports, presented about 100 years ago by Raab and von Tappeiner, concerned the influence of selected dyes on cell death under the influence of light. Additionally, it was noticed that in the absence of oxygen, the reaction does not occur. [

54,

55,

56] In 1913, the German scientist reported that hematoporphyrin, a first-generation photosensitizer, increases the skin's sensitivity to light. [

54].

In 1990, the photosensitizer 5-ALA and visible light were used, which confirmed the efficacy of PDT in the treatment of basal cell carcinoma. The overall response rate was up to 90% [

54]. PDT involves the intravenous, intraperitoneal, local or oral introduction of a photosensitive chemical - a photosensitizer (PS), and then its activation with light of an appropriate wavelength, which usually coincides with the longest absorption band of the photosensitizer and is approximately 600-800 nm. [

57,

58,

59] An oxidative reaction occurs, resulting in the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which in turn leads to cell death. [

57,

58] However,

ROS are continuously produced in living cells. They are by-products of normal metabolism, during metabolism of xenobiotics, and by radiation. The anticancer effects of PDT include: direct cytotoxic effects on cancer cells, damage to the microcirculation causing local ischemia, and stimulation of the immune response against the cancer. [

57,

58] The greatest advantages of photodynamic therapy are the safety of its simultaneous use with other methods: surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy, as well as the selective effect on selected (cancer) cells, which significantly reduces the risk of side effects. [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61]. Photodynamic therapy is used in the treatment of many diseases of various systems and tissues. It is commonly used in dermatological diseases such as keratosis, skin cancer and melanoma. PDT has also been shown to have an effect on the treatment of many types of solid organ cancers: esophagus, lung, prostate, breast, head and neck, biliary tract, urinary bladder, pancreas, cervix, brain and others. [

62]

Photosensitizers (PS), as substances necessary to carry out photodynamic therapy, should have certain features (

Table 1). An ideal photosensitizer accumulates only in tumors, has low activity in the absence of light and does not remain in the body for long. Since there are difficulties in selecting an appropriate substance that meets all the above criteria, based on the research conducted so far, photosensitizers have been divided into 3 generations, taking into account their molecular properties (

Table 1). First generation photosensitizers are naturally occurring porphyrins that are characterized by skin sensitivity and poor absorption at 630 nm. These features significantly limited their use in many diseases, which is why second-generation photosensitizers were distinguished, characterized by better parameters related to light absorption in a specific area of the spectrum and greater selectivity towards cancer. In turn, third-generation photosensitizers include nanoplatforms, genetically modified systems and carrier-bound systems. These substances show even greater cytotoxicity towards tumor areas. [

55,

59,

62,

63] The most thoroughly researched and most frequently used is 5-aminolaevulinic acid (5-ALA). [

61,

62,

63].

In turn, from the results presented by Schwartz et al. shows that in the group of patients with unresectable, newly diagnosed glioblastomas who, in addition to radiotherapy and chemotherapy, were also treated with PDT, a significantly longer median time to disease progression was found, which was 16.0 months compared to 10.2 months in patients who underwent resection. surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, and 3-year survival of 56.0 vs. 21.0% [

64]. Despite the encouraging first research results, some limitations related to photodynamic therapy should also be noted. Resistance to PDT is the main problem that specialists have to face. This may be due to, among others: from the development of cellular resistance or the occurrence of many biological barriers, such as technical limitations of light delivery, insufficient accumulation of the photosensitizer in the tumor, as well as limited transport of the photosensitizer to the area of postoperative resection [

45,

46]. Further research is needed, focusing on improving light delivery mechanisms and optimizing workflow.

6. The Effect of PDT on Gene Expression in Cells

The current treatment standards for sporadic gliomas include, in addition to surgical resection, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. These methods may contribute to DNA damage, which in turn may result in the development of secondary cancers.[

22,

65]. Taking into account inn the targeted treatment of cancer, organ-sparing technique and low systemic toxicity PDT seems to be a method bypassing the problems occurring when using currently recommended procedures, therefore we hope that should be the future of the treatment of these diseases.

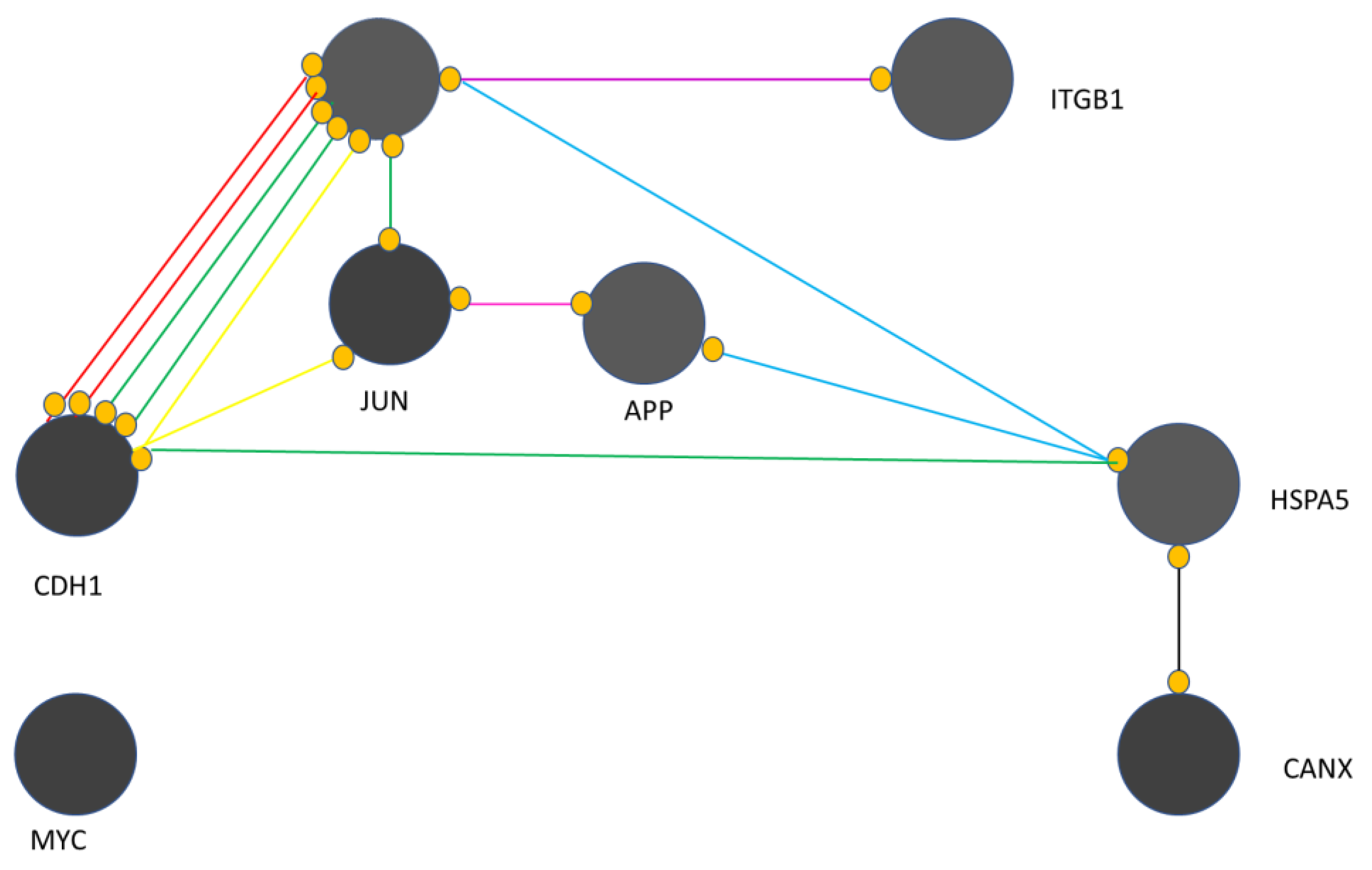

PDT affects the complicated expression of many genes in the treated cells, Studies on the mechanism of PDT show details of the molecular connections following the use of PDT [

66]. Gene expression analysis is used to understand the effects of PDT. The literature shows the genes changes in response to PDT [

67]. Bioinformatics methods such as network analysis are used for genomic and proteomic assessments [

68]. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis is a graph theory-based method that examines genes and proteins in an interacting unit called an interaction (

Figure 6) [

69]. To assess the feasibility of the analysis, gene expression profiles were assessed by mean difference plot analysis. Many significant upregulated and downregulated genes appear after PDT. In treated samples, significant changes in gene expression have been reported after PDT [

70]. It has been expressed that the detection of regulatory associations between genes is a suitable tool for the analysis of molecular events in the studied systems [

71].

Figure 3 shows that yellow, green, red, blue, purple, black, and pink colors refer to cellular functions e.g. expression, activation, inhibition, binding, catalysis, reaction, and post- PDT modification respectively. This map presents information that:

EGFR is critical in the presented map;

MYC remains isolated and has no interaction with other genes, i.e. CANX, CDH1, JUN, APP, HSPA5, EGFR and ITGB1;

CANX is associated with HSPA5 only through reaction activity;

ITGB1 is linked to EGFR through catalytic activity;

HSPA5 has binding connections with APP and EGFR,

HSPA5 activates CDH1.

APP and JUN have an association of post-translational modifications

EGFR and CDH1 have complex connections.

Cell proliferation, differentiation and survival is regulated by the binding of EGF to EGFR which initiates signaling pathways involved in this regulation of cellular functions. The relationship between EGFR and CDH1 and EGFR silencing leads to a significant regulation of cancer progression through the TGFBR1–EGFR–CTNNB1–CDH1 axis. The complex relationships between EGFR, CDH1, and JUN have emerged as the core of the molecular events in response to PDT. It was indicated that cell survival, differentiation and proliferation are the main relatively regulated processes in the examined cells after PDT [

72,

73].

The observed genomic changes after PDT helped to confirm the link between EGFR, CDH1 and JUN {74]. Cell survival, differentiation and proliferation were indicated as the main relatively regulated process in the studied cells after PDT. Also, after PDT decreased expression of ABCG2 was found. Research done by Gupta et al. showed down-regulation of ABCG2 mRNA with malignant change in 12 different tissues in arrays of paired normal and cancer cDNAs. They reported also down-regulation at the mRNA level of ABCG2 in human specimens of colorectal and cervical cancer [

74]. Research done by Liu et al. presented a range of ABCG2 expression, as well as a control cell line transfected with ABCG2 [

75]. The structure of the PS is a keypoint in the resitance mediated ABCG2. [

76]. These examples are a strong evidence for the future study of post PDT genetic changes. The results obteined in changes of gees after PDT are very pleased in current genetics and oncology.

Current treatment standards for sporadic gliomas include, in addition to surgical resection, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. These methods can contribute to DNA damage, which in turn can result in the development of secondary cancers, to which patients affected by the above genetic syndromes are predisposed.

Due to the rarity of the described syndromes, there is little data on the use of photodynamic therapy in these patients, which is associated with the need to conduct appropriate studies. [

60]

To investigate the role of p53 in cellular sensitivity to photodynamic therapy, in the study by Tong et al., normal human fibroblasts expressing wild-type p53 and immortalized Li-Fraumeni Syndrome cells expressing only mutant p53 were used after PDT with Photofrin. The clonogenic survival of both cell groups was compared. LFS cells were found to be more resistant to PDT compared to normal human fibroblasts. Although normal human fibroblasts showed increased levels of p53 after PDT, no apoptosis or any obvious changes in the cell cycle were detected. LFS cells showed prolonged accumulation of cells in the G2 phase and underwent apoptosis after PDT at equivalent levels of Photofrin. The number of apoptotic LFS cells increased with time after PDT and correlated with the loss of cell viability.[

76]

Because of the resistance of DNA mismatch repair deficient cells to many chemotherapeutic agents and radiotherapy and the potential to rapidly acquire additional mutations leading to tumor progression, a study was conducted to assess the effect of loss of DNA mismatch repair activity on sensitivity to photodynamic therapy. Cell lines that were proficient and deficient in mismatch repair due to loss of MLH1 or MSH2 protein function were used. Using a clonogenic assay, loss of mismatch repair did not appear to contribute to resistance to photodynamic therapy. This suggests that photodynamic therapy may be a strategy to circumvent resistance resulting from loss of DNA mismatch repair. [

77] There is no data in the available literature regarding the use of PDT in the treatment of brain tumors in patients with TSC. In this group of patients, PDT has so far been used to treat facial angiofibromas and retinal astrocytomas. [

78,

79,

80] A patient treated with photodynamic therapy with 5-aminolevulinic acid due to facial angiofibroma achieved a 6-year remission of the disease [78, while in the patient treated with a combination of photodynamic therapy and ultrapulse carbon dioxide laser, satisfactory results were achieved. [

79] The authors of the results of the treatment of a patient with aggressive retinal astrocytoma suggest that PDT with verteporfin can be considered as the first-line treatment for the above conditions. [

80] A group of researchers from the University of Florida and the Medical College of Wisconsin conducted preliminary in vitro and in vivo studies to determine the sensitivity of human NF1 tumor cells to PDT. They showed that in vitro PDT ablated various cultures of NF1 tumor cells using Photofrin, sodium talaporfin, or aminolevulinic acid (ALA), whereas normal Schwann cells were less susceptible to PDT, requiring significantly higher doses of PS to achieve cell death. [

81,

82] Effects of PDT on the treatment of patients with von Hippel-Lindau syndrome

To date, PDT in patients with von Hippel-Lindau syndrome has been used to treat eye conditions, primarily retinal hemangiomas. In a study of seventeen patients with retinal hemangioblastoma who underwent photodynamic therapy, 47% were patients with von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Satisfactory rates of tumor control and visual stabilization and improvement were achieved.[

83]

7. Conclusions

The presence of PS without PDT does not have a significant impact on the gene expression profiles of the cells examined. The presence of PS with PDT influences the gene expression profiles of the examined cells. Bioinformatics combined with genomics provides valuable information about molecular events in living systems. In future work, it may be recommended to evaluate the role of EGFR, CDH1 and JUN in response to PDT based on the synergistic effect of related drugs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.I., J.S., J.T., D.B.-A., and D.A.; methodology J.I., J.S., D.B.-A., and D.A.; software, J.I., J.S., J.T., D.B.-A., and D.A.; validation, .I., J.S., J.T., D.B.-A., and D.A.; formal analysis, .I., J.S., D.B.-A., and D.A.; Investigation, J.I., J.S., D.B.-A., and D.A.; resources, J.I., J.S., J.T., D.B.-A., and D.A.; data curation, J.I., J.S., J.T., D.B.-A., and D.A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.I., J.S., J.T., D.B.-A., and D.A.; writing—review and editing, J.I., J.S., J.T., D.B.-A., and D.A.; visualization, J.I., J.S., J.T., D.B.-A., and D.A.; supervision, J.I., J.S., J.T., D.B.-A., and D.A.; funding acquisition, J.I., J.S., J.T., D.B.-A., and D.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Schena, M.; Shalon, D.; Heller, R.; Chai, A.; O Brown, P.; Davis, R.W. Parallel human genome analysis: microarray-based expression monitoring of 1000 genes.. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1996, 93, 10614–10619. [CrossRef]

- Shete S, Hosking FJ, Robertson LB, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies five susceptibility loci for glioma. Nat Genet. 2009 Aug;41(8):899–U54. doi:10.1038/ng.407.

- Wrensch, M.; Jenkins, R.B.; Chang, J.S.; Yeh, R.-F.; Xiao, Y.; Decker, P.A.; Ballman, K.V.; Berger, M.; Buckner, J.C.; Chang, S.; et al. Variants in the CDKN2B and RTEL1 regions are associated with high-grade glioma susceptibility. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 905–908. [CrossRef]

- Malmer, B.; Feychting, M.; Lönn, S.; Ahlbom, A.; Henriksson, R. p53 Genotypes and Risk of Glioma and Meningioma. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers Prev. 2005, 14, 2220–2223. [CrossRef]

- Roda, D.; Veiga, P.; Melo, J.B.; Carreira, I.M.; Ribeiro, I.P. Principles in the Management of Glioblastoma. Genes 2024, 15, 501. [CrossRef]

- Vizcaino, M.A.; Palsgrove, D.N.; Yuan, M.; Giannini, C.; Cabrera-Aldana, E.E.; Pallavajjala, A.; Burger, P.C.; Rodriguez, F.J. Granular cell astrocytoma: an aggressive IDH-wildtype diffuse glioma with molecular genetic features of primary glioblastoma. Brain Pathol. 2019, 29, 193–204. [CrossRef]

- Testa, U.; Castelli, G.; Pelosi, E. Genetic Abnormalities, Clonal Evolution, and Cancer Stem Cells of Brain Tumors. Med Sci. 2018, 6, 85. [CrossRef]

- Kober, P.; Rymuza, J.; Baluszek, S.; Maksymowicz, M.; Nyc, A.; Mossakowska, B.J.; Zieliński, G.; Kunicki, J.; Bujko, M. DNA Methylation Pattern in Somatotroph Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumors. Neuroendocrinology 2023, 114, 51–63. [CrossRef]

- Balss, J.; Meyer, J.; Mueller, W.; Korshunov, A.; Hartmann, C.; von Deimling, A. Analysis of the IDH1 codon 132 mutation in brain tumors. Acta Neuropathol. 2008, 116, 597–602. [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Parsons, D.W.; Jin, G.; McLendon, R.; Rasheed, B.A.; Yuan, W.; Kos, I.; Batinic-Haberle, I.; Jones, S.; Riggins, G.J.; et al. IDH1andIDH2Mutations in Gliomas. New Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 765–773. [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Liu, Y.; Cai, S.J.; Qian, M.; Ding, J.; Larion, M.; Gilbert, M.R.; Yang, C. IDH mutation in glioma: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 122, 1580–1589. [CrossRef]

- Westphal, M.; Hamel, W.; Kunzmann, R.; Hänsel, M.; Hölzel, F. Karyotype analyses of 20 human glioma cell lines. Acta Neurochir. 1994, 126, 17–26. [CrossRef]

- Fritz, G.; Tano, K.; Mitra, S.; Kaina, B. Inducibility of the DNA Repair Gene Encoding O6-Methylguanine- DNA Methyltransferase in Mammalian Cells by DNA-Damaging Treatments. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991, 11. [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Francis, S.S.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. Epidemiology of Brain and Other CNS Tumors. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2021, 21, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Patil, N.; Cioffi, G.; Waite, K.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2013–2017. Neuro-Oncology 2020, 22 (Suppl. 2), iv1–iv96. [CrossRef]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, 1231–1251. [CrossRef]

- Panek , P., & Jezela-Stanek, A. (2023). Genetyczne i molekularne podłoża rozwoju glejaka. Postępy Biochemii, 69(4), 254-263. [CrossRef]

- Melin, B.; Dahlin, A.M.; Andersson, U.; Wang, Z.; Henriksson, R.; Hallmans, G.; Bondy, M.L.; Johansen, C.; Feychting, M.; Ahlbom, A.; et al. Known glioma risk loci are associated with glioma with a family history of brain tumours—A case–control gene association study. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 132, 2464–2468. [CrossRef]

- Idbaih, A.; Boisselier, B.; Sanson, M.; Crinière, E.; Liva, S.; Marie, Y.; Carpentier, C.; Paris, S.; Laigle-Donadey, F.; Mokhtari, K.; et al. Tumor genomic profiling and TP53 germline mutation analysis of first-degree relative familial gliomas. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 2007, 176, 121–126. [CrossRef]

- Panek, P., & Jezela-Stanek, A. (2023). Genetyczne i molekularne podłoża rozwoju glejaka. Postępy Biochemii, 69(4), 254-263. [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.; Kamiya-Matsuoka, C.; Slopis, J.M.; McCutcheon, I.E.; Majd, N.K. Therapeutic Strategies for Gliomas Associated With Cancer Predisposition Syndromes. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, e2300442. [CrossRef]

- Wańkowicz, Paweł, and Przemysław Nowacki. "Glioblastoma Multiforme–the Progress of Knowledge on the Pathogenesis of C." Pomeranian Journal of Life Sciences 60.2 (2014): 40-43.

- Gargallo, P.; Yáñez, Y.; Segura, V.; Juan, A.; Torres, B.; Balaguer, J.; Oltra, S.; Castel, V.; Cañete, A. Li–Fraumeni syndrome heterogeneity. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2020, 22, 978–988. [CrossRef]

- Schneider K, Zelley K, Nichols KE, Garber J. Li-Fraumeni Syndrome. 1999 Jan 19 [updated 2019 Nov 21]. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, Amemiya A, editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2024. PMID: 20301488.

- Guidi, M.; Giunti, L.; Lucchesi, M.; Scoccianti, S.; Giglio, S.; Favre, C.; Oliveri, G.; Sardi, I. Brain tumors in Li-Fraumeni syndrome: a commentary and a case of a gliosarcoma patient. Futur. Oncol. 2016, 13, 9–12. [CrossRef]

- Idbaih, A.; Boisselier, B.; Sanson, M.; Crinière, E.; Liva, S.; Marie, Y.; Carpentier, C.; Paris, S.; Laigle-Donadey, F.; Mokhtari, K.; et al. Tumor genomic profiling and TP53 germline mutation analysis of first-degree relative familial gliomas. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 2007, 176, 121–126. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Kaneda, M.; Futagawa, M.; Takeshita, M.; Kim, S.; Nakama, M.; Kawashita, N.; Tatsumi-Miyajima, J. Genetic and genomic basis of the mismatch repair system involved in Lynch syndrome. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 24, 999–1011. [CrossRef]

- Büttner, R.; Friedrichs, N. Erblicher Darmkrebs bei Lynch-/HNPCC-Syndrom in Deutschland. Der Pathol. 2019, 40, 584–591. [CrossRef]

- Rojek, A., Zub, W. L., Waliszewska-Prosół, M., Bladowska, J., Obara, K., & Ejma, M. (2016). Wieloletnie przeżycie chorych z glejakiem wielopostaciowym—opisy przypadków. Polski Przegląd Neurologiczny, 12(2), 107-115.

- Alnahhas, I.; Rayi, A.; Ong, S.; Giglio, P.; Puduvalli, V. Management of gliomas in patients with Lynch syndrome. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, 167–168. [CrossRef]

- Maratt, J.K.; Stoffel, E. Identification of Lynch Syndrome. Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. North Am. 2022, 32, 45–58. [CrossRef]

- Kastrinos, F.; Stoffel, E.M. History, Genetics, and Strategies for Cancer Prevention in Lynch Syndrome. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 12, 715–727. [CrossRef]

- Pellat, A.; Netter, J.; Perkins, G.; Cohen, R.; Coulet, F.; Parc, Y.; Svrcek, M.; Duval, A.; André, T. Syndrome de Lynch : quoi de neuf ?. Bull. du Cancer 2018, 106, 647–655. [CrossRef]

- Therkildsen, C.; Ladelund, S.; Rambech, E.; Persson, A.; Petersen, A.; Nilbert, M. Glioblastomas, astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas linked to Lynch syndrome. Eur. J. Neurol. 2015, 22, 717–724. [CrossRef]

- Peltomäki, P.; Nyström, M.; Mecklin, J.-P.; Seppälä, T.T. Lynch Syndrome Genetics and Clinical Implications. Gastroenterology 2023, 164, 783–799. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya P, McHugh TW. Lynch Syndrome. 2023 Feb 4. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 28613748.

- Kampitsi, C.-E.; Nordgren, A.; Mogensen, H.; Pontén, E.; Feychting, M.; Tettamanti, G. Neurocutaneous Syndromes, Perinatal Factors, and the Risk of Childhood Cancer in Sweden. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2325482–e2325482. [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, N.J. Neurocutaneous Syndromes and Brain Tumors. J. Child Neurol. 2016, 31, 1399–1411. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.P. Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 2021, 37, 100875. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, R. Current Understanding of Neurofibromatosis Type 1, 2, and Schwannomatosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5850. [CrossRef]

- Hirbe, A.C.; Gutmann, D.H. Neurofibromatosis type 1: a multidisciplinary approach to care. Lancet Neurol. 2014, 13, 834–843. [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwaarde RS, Ahmad S, van Nesselrooij B, Zandee W, Giles RH. Von Hippel-Lindau Syndrome. 2000 May 17 [updated 2024 Feb 29]. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, Amemiya A, editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2024. PMID: 20301636.

- Myong, N.-H.; Park, B.-J. Malignant Glioma Arising at the Site of an Excised Cerebellar Hemangioblastoma after Irradiation in a von Hippel-Lindau Disease Patient. Yonsei Med J. 2009, 50, 576–581. [CrossRef]

- Mikhail MI, Singh AK. Von Hippel-Lindau Syndrome. 2023 Jan 30. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 29083737.

- Rkein, A.M.; Ozog, D.M. Photodynamic Therapy. Dermatol. Clin. 2014, 32, 415–425. [CrossRef]

- Aldape, K.; Simmons, M.L.; Davis, R.L.; Miike, R.; Wiencke, J.; Barger, G.; Lee, M.; Chen, P.; Wrensch, M. Discrepancies in diagnoses of neuroepithelial neoplasms: the San Francisco Bay Area Adult Glioma Study.. 2000, 88, 2342–9.

- Karak, A.K.; Singh, R.; Tandon, P.N.; Sarkar, C. A comparative survival evaluation and assessment of interclassification concordance in adult supratentorial astrocytic tumors.. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2000, 6, 46–52. [CrossRef]

- Stummer, W.; Stepp, H.; Möller, G.; Ehrhardt, A.; Leonhard, M.; Reulen, H.J. Technical Principles for Protoporphyrin-IX-Fluorescence Guided Microsurgical Resection of Malignant Glioma Tissue. Acta Neurochir. 1998, 140, 995–1000. [CrossRef]

- Muller, P.J.; Wilson, B.C. Photodynamic therapy of brain tumors—A work in progress. Lasers Surg. Med. 2006, 38, 384–389. [CrossRef]

- Verwanger, T.; Sanovic, R.; Aberger, F.; Frischauf, A.-M.; Krammer, B. Gene expression pattern following photodynamic treatment of the carcinoma cell line A-431 analysed by cDNA arrays. Int. J. Oncol. 2002, 21, 1353–1359. [CrossRef]

- Wild, P.J.; Krieg, R.C.; Seidl, J.; Stoehr, R.; Reher, K.; Hofmann, C.; Louhelainen, J.; Rosenthal, A.; Hartmann, A.; Pilarsky, C.; et al. RNA expression profiling of normal and tumor cells following photodynamic therapy with 5-aminolevulinic acid–induced protoporphyrin IX in vitro. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2005, 4, 516–528. [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.S.; Zande, P.V.; Wittkopp, P.J. Molecular and evolutionary processes generating variation in gene expression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020, 22, 203–215. [CrossRef]

- Josefsen, L.B.; Boyle, R.W. Photodynamic Therapy and the Development of Metal-Based Photosensitisers. Met. Drugs 2008, 2008, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Kessel, D. Photodynamic Therapy: A Brief History. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1581. [CrossRef]

- Javed, Z.; Aziz, H.F.; Shamim, M.S. Photodynamic Therapy In Adult Intra-Axial Brain Tumours. J. Pak. Med Assoc. 2024, 74, 404–406. [CrossRef]

- Donohoe, C.; Senge, M.O.; Arnaut, L.G.; Gomes-Da-Silva, L.C. Cell death in photodynamic therapy: From oxidative stress to anti-tumor immunity. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Rev. Cancer 2019, 1872, 188308. [CrossRef]

- Correia, J.H.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Pimenta, S.; Dong, T.; Yang, Z. Photodynamic Therapy Review: Principles, Photosensitizers, Applications, and Future Directions. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1332. [CrossRef]

- Aebisher, D.; Przygórzewska, A.; Myśliwiec, A.; Dynarowicz, K.; Krupka-Olek, M.; Bożek, A.; Kawczyk-Krupka, A.; Bartusik-Aebisher, D. Current Photodynamic Therapy for Glioma Treatment: An Update. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 375. [CrossRef]

- Bhanja, D.; Wilding, H.; Baroz, A.; Trifoi, M.; Shenoy, G.; Slagle-Webb, B.; Hayes, D.; Soudagar, Y.; Connor, J.; Mansouri, A. Photodynamic Therapy for Glioblastoma: Illuminating the Path toward Clinical Applicability. Cancers 2023, 15, 3427. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lovell, J.F.; Yoon, J.; Chen, X. Clinical development and potential of photothermal and photodynamic therapies for cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 657–674. [CrossRef]

- Hsia, T.; Small, J.L.; Yekula, A.; Batool, S.M.; Escobedo, A.K.; Ekanayake, E.; Gil You, D.; Lee, H.; Carter, B.S.; Balaj, L. Systematic Review of Photodynamic Therapy in Gliomas. Cancers 2023, 15, 3918. [CrossRef]

- Bartusik-Aebisher, D.; Żołyniak, A.; Barnaś, E.; Machorowska-Pieniążek, A.; Oleś, P.; Kawczyk-Krupka, A.; Aebisher, D. The Use of Photodynamic Therapy in the Treatment of Brain Tumors—A Review of the Literature. Molecules 2022, 27, 6847. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, C., Stepp, H., Rühm, A., Tonn, J. C., Kreth, S., & Kreth, F. W. (2015, June). Interstitial photodynamic therapy for de-novo glioblastoma multiforme WHO IV: a feasibility study. In Proceedings of the 66th Annual Meeting of the German Society of Neurosurgery (DGNC), Karlsruhe, Germany (pp. 7-10).

- Mikhail MI, Singh AK. Von Hippel-Lindau Syndrome. 2023 Jan 30. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 29083737.

- Rkein, A.M.; Ozog, D.M. Photodynamic Therapy. Dermatol. Clin. 2014, 32, 415–425. [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, S.; Knap, B.; Przystupski, D.; Saczko, J.; Kędzierska, E.; Knap-Czop, K.; Kotlińska, J.; Michel, O.; Kotowski, K.; Kulbacka, J. Photodynamic therapy – mechanisms, photosensitizers and combinations. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 106, 1098–1107. [CrossRef]

- Aniogo, E.C.; George, B.P.A.; Abrahamse, H. The role of photodynamic therapy on multidrug resistant breast cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2019, 19, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Sun, C.; Hou, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, M.-G.; et al. A comprehensive bioinformatics analysis on multiple Gene Expression Omnibus datasets of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Sun, C.; Hou, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, M.-G.; et al. A comprehensive bioinformatics analysis on multiple Gene Expression Omnibus datasets of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.B. Estimation of Gene Regulatory Networks from Cancer Transcriptomics Data. Processes 2021, 9, 1758. [CrossRef]

- Herbst, R.S. Review of epidermal growth factor receptor biology. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2004, 59, S21–S26. [CrossRef]

- Verwanger, T. Time-resolved gene expression profiling of human squamous cell carcinoma cells during the apoptosis process induced by photodynamic treatment with hypericin. Int. J. Oncol. 2009, 35, 921–939. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Martin, P.M.; Miyauchi, S.; Ananth, S.; Herdman, A.V.; Martindale, R.G.; Podolsky, R.; Ganapathy, V. Down-regulation of BCRP/ABCG2 in colorectal and cervical cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 343, 571–577. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Baer, M.R.; Bowman, M.J.; Pera, P.; Zheng, X.; Morgan, J.; Pandey, R.A.; Oseroff, A.R. The Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Imatinib Mesylate Enhances the Efficacy of Photodynamic Therapy by Inhibiting ABCG2. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 2463–2470. [CrossRef]

- Robey, R.W.; Steadman, K.; Polgar, O.; Bates, S.E. ABCG2-mediated transport of photosensitizers: Potential impact on photodynamic therapy. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2005, 4, 195–202. [CrossRef]

- Tong Z, Singh G, Rainbow AJ. The role of the p53 tumor suppressor in the response of human cells to photofrin-mediated photodynamic therapy. Photochem Photobiol. 2000 Feb;71(2):201-10. doi:10.1562/0031-8655(2000)071<0201:trotpt>2.0.co;2. PMID: 10687395.

- A Schwarz, V.; Hornung, R.; Fedier, A.; Fehr, M.K.; Walt, H.; Haller, U.; Fink, D. Photodynamic therapy of DNA mismatch repair-deficient and -proficient tumour cells. Br. J. Cancer 2002, 86, 1130–1135. [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; He, S.; Chen, P.; Li, Q.; Zhu, M.; Guo, J.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Q.; Peng, X.; Li, S.; et al. Photodynamic therapy in a patient with facial angiofibromas due to tuberous sclerosis complex. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 28, 183–185. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yao, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhang, L.; Peng, D.; Zhang, G. The combination of photodynamic therapy and ultrapulse carbon dioxide laser for facial angiofibromas in tuberous sclerosis complex: A case report. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2022, 37, 102725. [CrossRef]

- Eskelin, S.; Tommila, P.; Palosaari, T.; Kivelä, T. Photodynamic therapy with verteporfin to induce regression of aggressive retinal astrocytomas. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008, 86, 794–799. [CrossRef]

- Quirk, B.; Olasz, E.; Kumar, S.; Basel, D.; Whelan, H. Photodynamic Therapy for Benign Cutaneous Neurofibromas Using Aminolevulinic Acid Topical Application and 633 nm Red Light Illumination. Photobiomodulation, Photomedicine, Laser Surg. 2021, 39, 411–417. [CrossRef]

- Muir, D., Perrin, G., Neubauer, D., & Whelan, H. (2008, June). Photodynamic therapy development using NF1 tumor xenografts. In Children’s Tumor Foundation Conference.

- Di Nicola, M.; Williams, B.K.; Hua, J.; Bekerman, V.P.; Mashayekhi, A.; Shields, J.A.; Shields, C.L. Photodynamic Therapy for Retinal Hemangioblastoma: Treatment Outcomes of 17 Consecutive Patients. Ophthalmol. Retin. 2021, 6, 80–88. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).