Submitted:

01 January 2025

Posted:

04 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background: As the global population ages, mental health challenges such as depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline become increasingly prevalent. Smart home technologies (SHTs) offer potential for real-time monitoring and early intervention, yet practical barriers related to usability, accessibility, and user acceptance persist. Methods: This narrative review summarizes literature from 2010 to early 2024 on SHT development, focusing on older adults’ mental health needs. User-centered design principles, accessibility guidelines, and ethical considerations were synthesized to identify challenges and facilitators. Results: Findings highlight issues such as complex interfaces, cognitive overload, and high costs, which limit SHT adoption. Accessibility barriers, including physical and sensory impairments, likewise reduce engagement and threaten the inclusivity of current SHT solutions. Nevertheless, research shows that user-centric design, participatory co-development, and adaptive interfaces can significantly improve acceptance. Early detection systems integrating AI-driven behavioral monitoring, medication reminders, and social engagement features demonstrate promise for timely mental health support. Conclusions: By addressing usability, accessibility, affordability, and privacy concerns through a multidisciplinary framework, SHTs can facilitate holistic mental health care for older adults. These systems have the potential to enhance autonomy, support aging in place, and foster improved wellbeing, provided that they are tailored to the diverse needs of end users.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Context of the Aging Population

1.2. Smart Home Technologies (SHTs) as a Solution, and Adoption Barriers

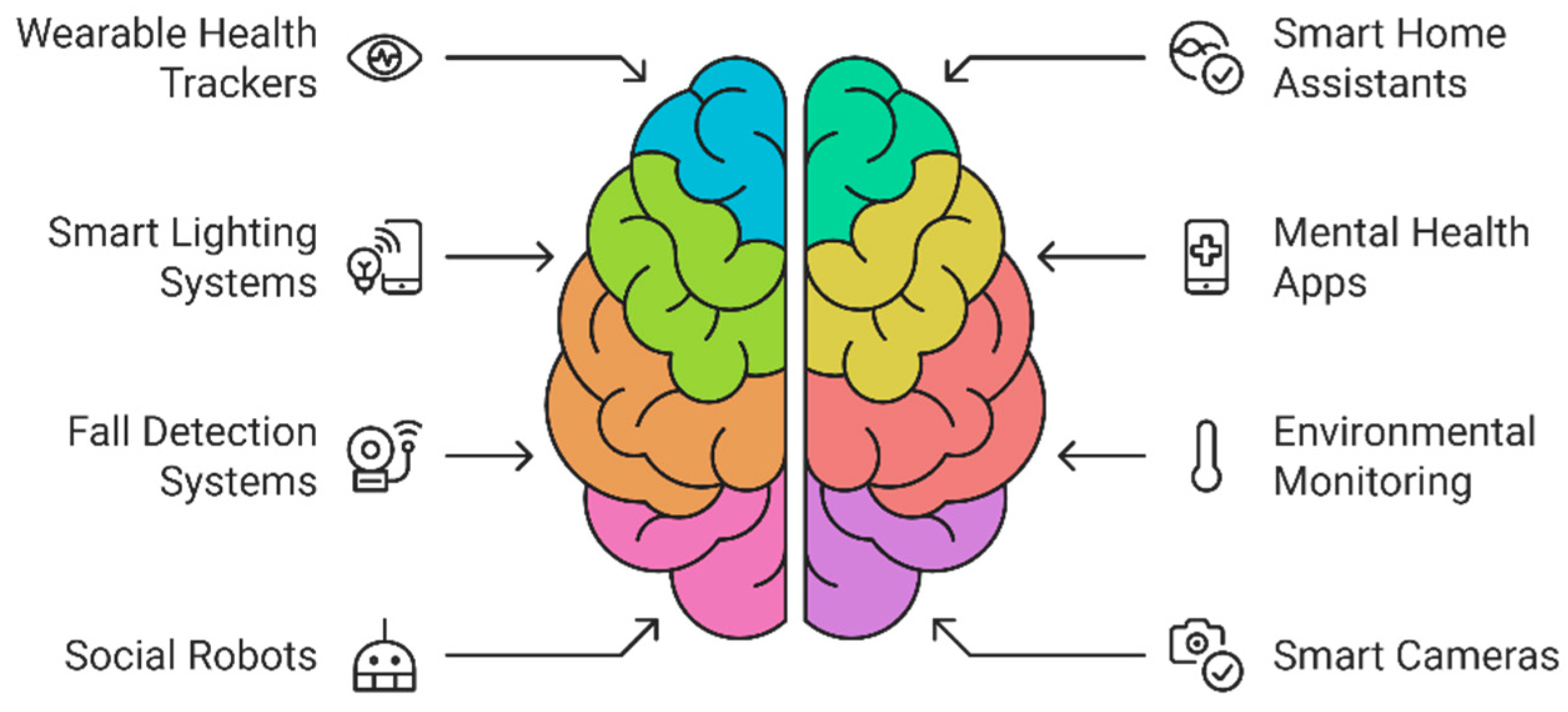

1.3. Early Detection and Intervention Through SHTs: Features and Interventions

1.4. Purpose and Scope

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

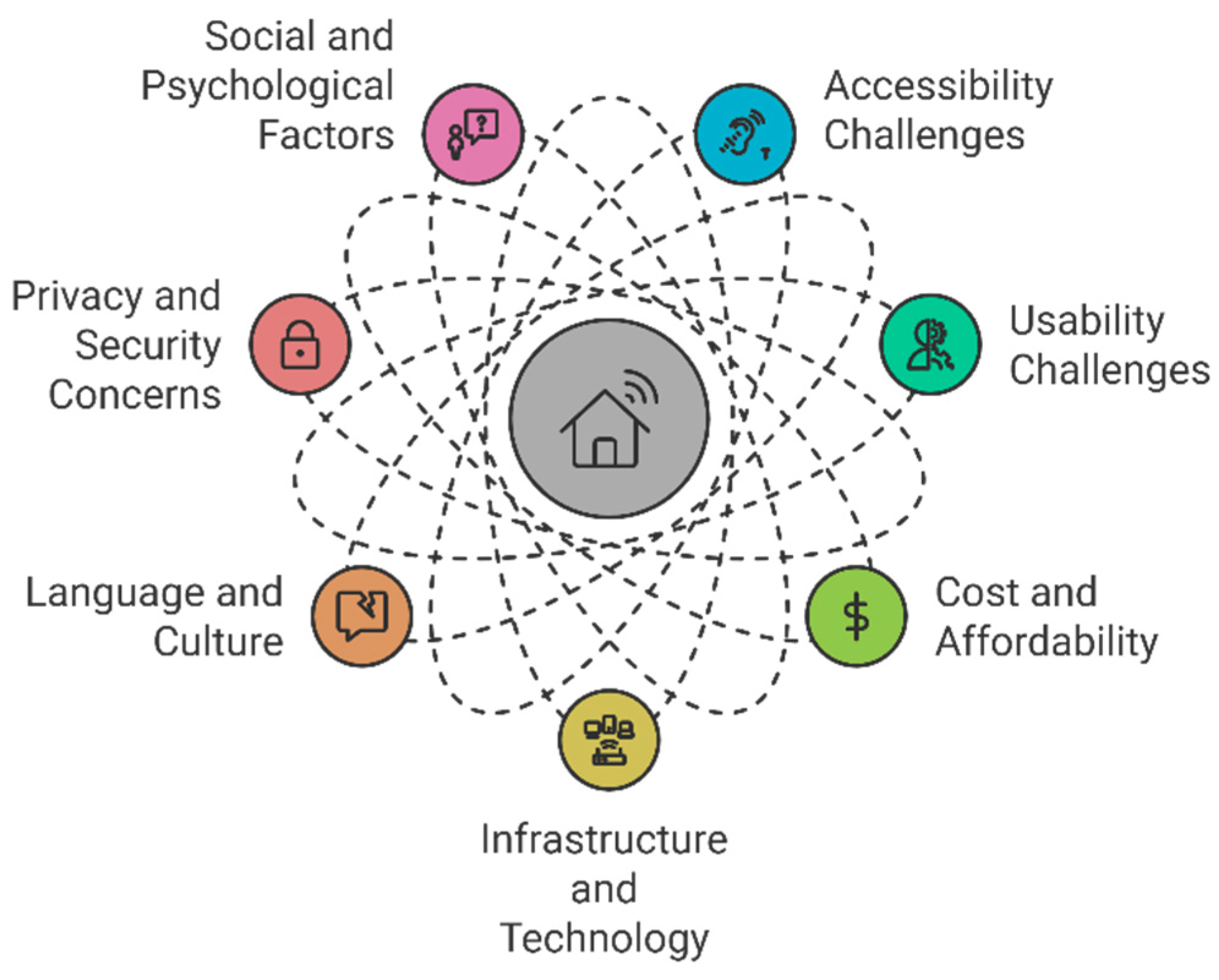

3.1. Usability and Accessibility Challenges in SHTs

3.2. Literature-Identified Gaps

3.2.1. Overemphasis on Physical Health Monitoring

3.2.2. Lack of Personalization and User-Centered Testing

3.2.3. Privacy Concerns and Siloed Data Streams

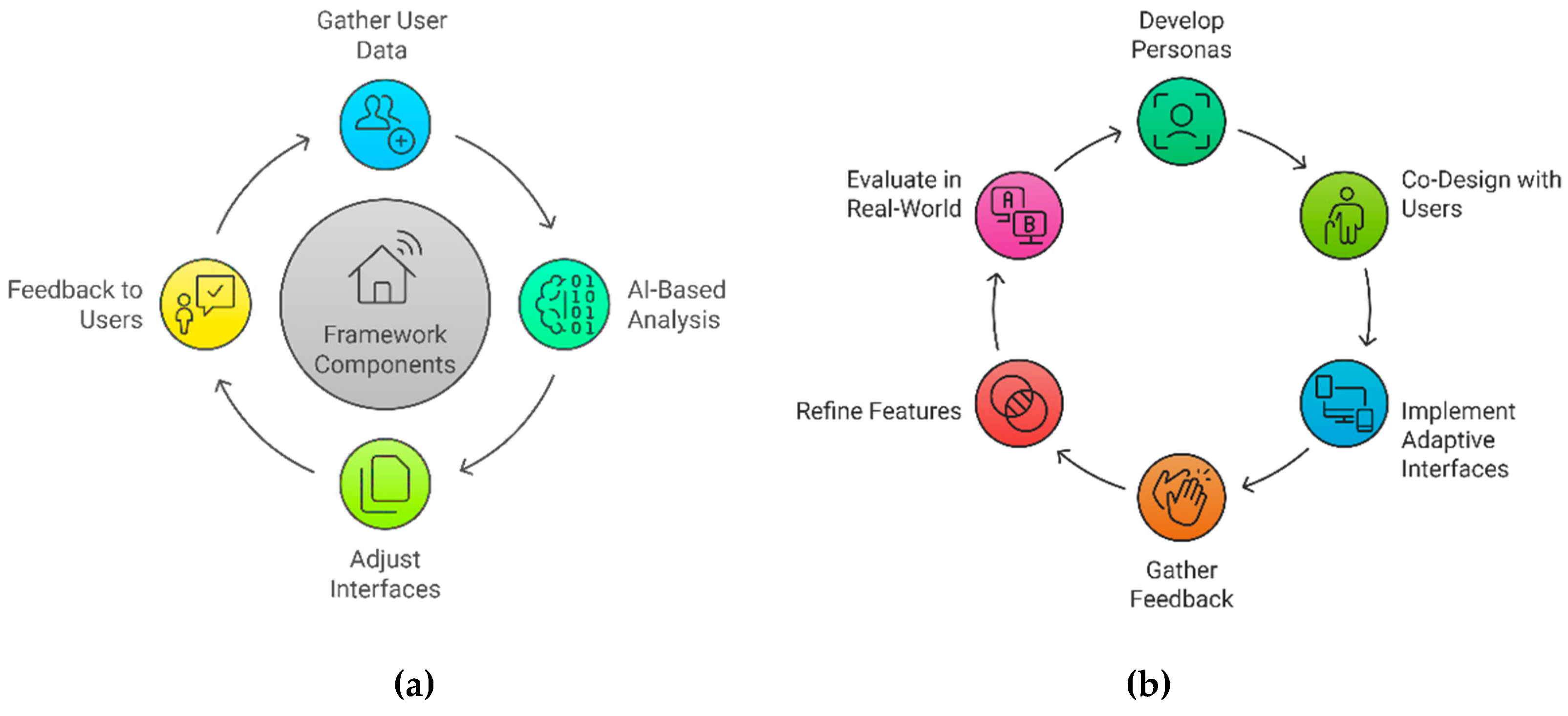

3.3. Proposed Solutions: Design Strategies and Co-Creation

3.4. Conceptual Framework for Integrative Smart Home Solutions

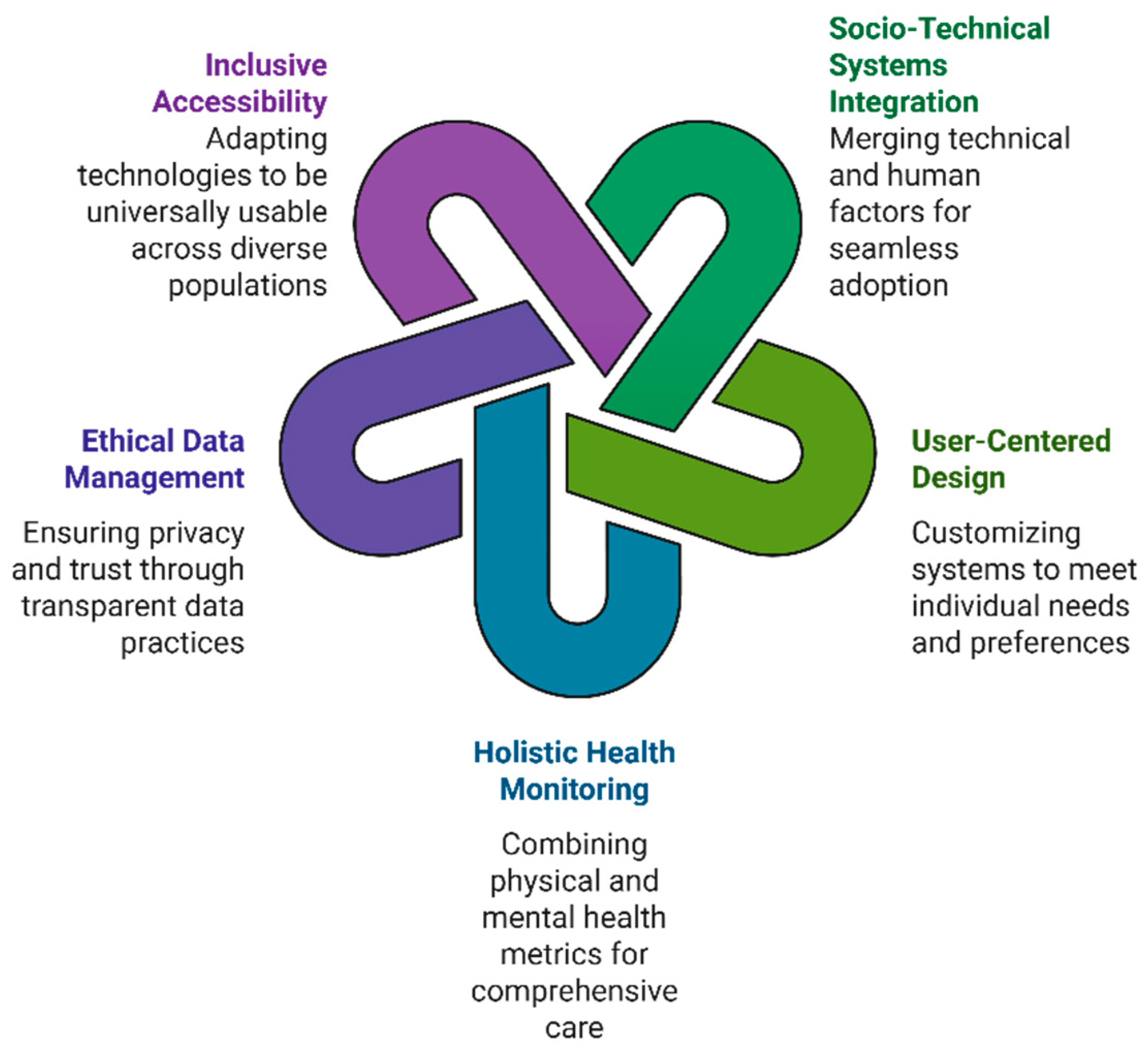

3.4.1. Core Principles of the Framework

- o

- Socio-Technical Systems Integration: Effective adoption of smart home technologies (SHTs) requires more than technical proficiency; it also depends on social, cultural, and behavioral dynamics. User acceptance is shaped by the perceived relevance of the technology, concerns over data privacy, and trust in system reliability [15,16]. By merging technical and human factors, SHTs can be embedded into older adults’ daily lives in a way that feels intuitive and supportive rather than intrusive [12,17].

- o

- User-Centered Design and Personalization: Research repeatedly emphasizes the need for customization, co-design, and iterative feedback loops [25,26]. Systems that offer adjustable font sizes, voice or gesture controls, and culturally responsive settings empower older adults to tailor interactions to their cognitive, physical, and linguistic needs [18,19]. Over time, personalization can reduce anxiety, improve satisfaction, and increase sustained use [20,27].

- o

- Holistic Health Monitoring: While physical health metrics (e.g., fall detection, vitals) are critical, mental health indicators—such as mood, cognitive performance, and social engagement—must be equally prioritized [7,9,22]. Combining behavioral sensing (sleep, mobility), cognitive tasks (brief in-home quizzes), and emotional analysis (AI-based voice or facial recognition) provides a more comprehensive portrait of well-being [23,24]. Proactive interventions emerge when data streams are integrated seamlessly rather than kept in silos [30,31].

- o

- Ethical Data Management and Transparency: Continuous monitoring, especially of mental and emotional states, raises legitimate privacy and ethical concerns [16,17]. Clear communication of data practices—how information is collected, stored, and shared—fosters trust among older users [15]. Robust security measures (e.g., encryption, secure cloud storage) and user consent tools (e.g., opting o ut of certain sensors) are central to reinforcing comfort and acceptance [14,19].

- o

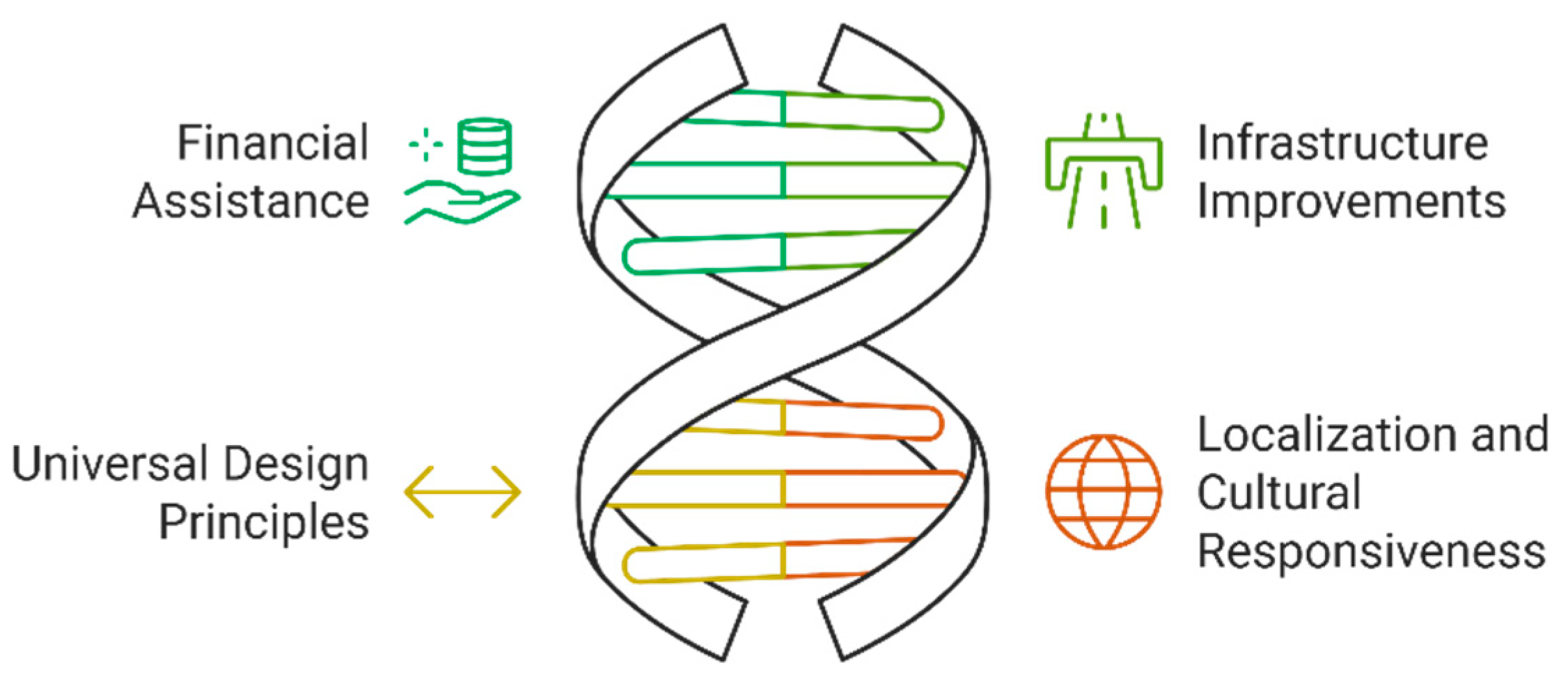

- Inclusive Accessibility: The framework underscores universal design principles, adapting to visual, auditory, and motor impairments [12,13]. Additionally, cultural and linguistic responsiveness broadens SHT relevance worldwide, ensuring older adults can interact with the system in ways that align with local norms, language preferences, and values [14,25].

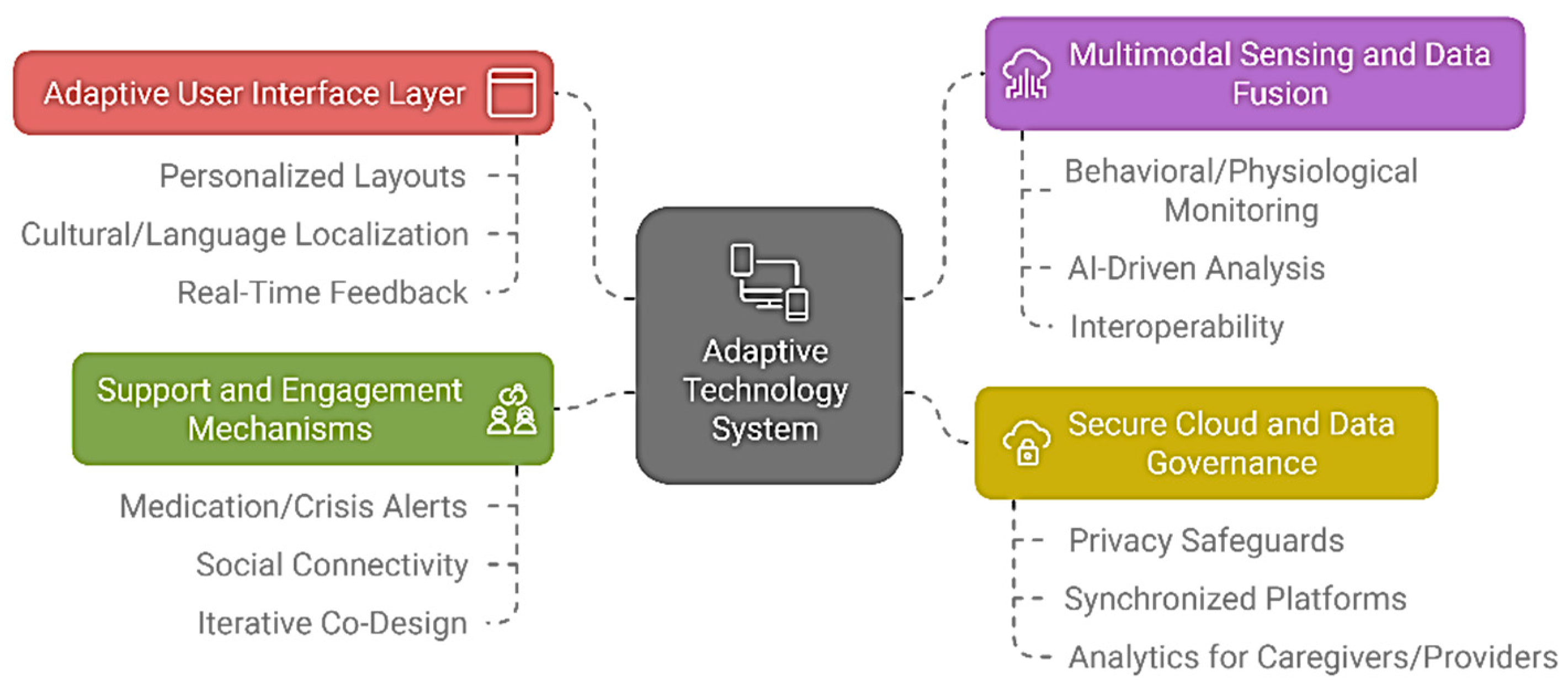

3.4.2. Framework Components and Dynamics

- o

- Adaptive User Interface Layer: 1. Personalized Layouts: Large buttons, high-contrast visuals, voice/gesture input for users with varying dexterity or vision [12,18]. 2.Cultural/Language Localization: Multi-language support, culturally relevant prompts, and flexible navigation to accommodate diverse backgrounds [14,25]. 3. Real-Time Feedback: Simple, reassuring messages or icons confirming user actions, minimizing technology anxiety [3,11].

- o

- Multimodal Sensing and Data Fusion: 1. Behavioral/Physiological Monitoring: Sleep patterns, physical activity, and vital signs integrated with mental health indicators (mood, memory tasks) [22,24]. 2. AI-Driven Analysis: Emotional state inference via speech/text analysis or facial recognition, delivering discreet alerts for significant mental health risks [25,30]. 3. Interoperability: Standardized protocols that unify disparate sensors and systems, offering a holistic view of user well-being [12,31].

- o

- Secure Cloud and Data Governance: 1. Privacy Safeguards: Encryption, anonymization, and user-controlled permissions to mitigate surveillance fears and align with ethical guidelines [15,16]. 2. Synchronized Platforms: A unified database ensures consistent updates across devices (smart speakers, tablets, wearables), avoiding siloed data [13,31]. 3. Analytics for Caregivers/Providers: Seamless sharing of relevant metrics with trusted parties, enabling timely intervention for mental health concerns [29,32].

- o

- Support and Engagement Mechanisms: 1. Medication/Crisis Alerts: Automated reminders and emergency notifications that incorporate both mental and physical health triggers [27,30]. 2. Social Connectivity: In-home video conferencing, online communities, and interactive programs to reduce isolation [31,32]. 3. Iterative Co-Design: Continuous user feedback sessions to refine both interface and features, ensuring SHTs stay aligned with older adults’ evolving needs [20,26].

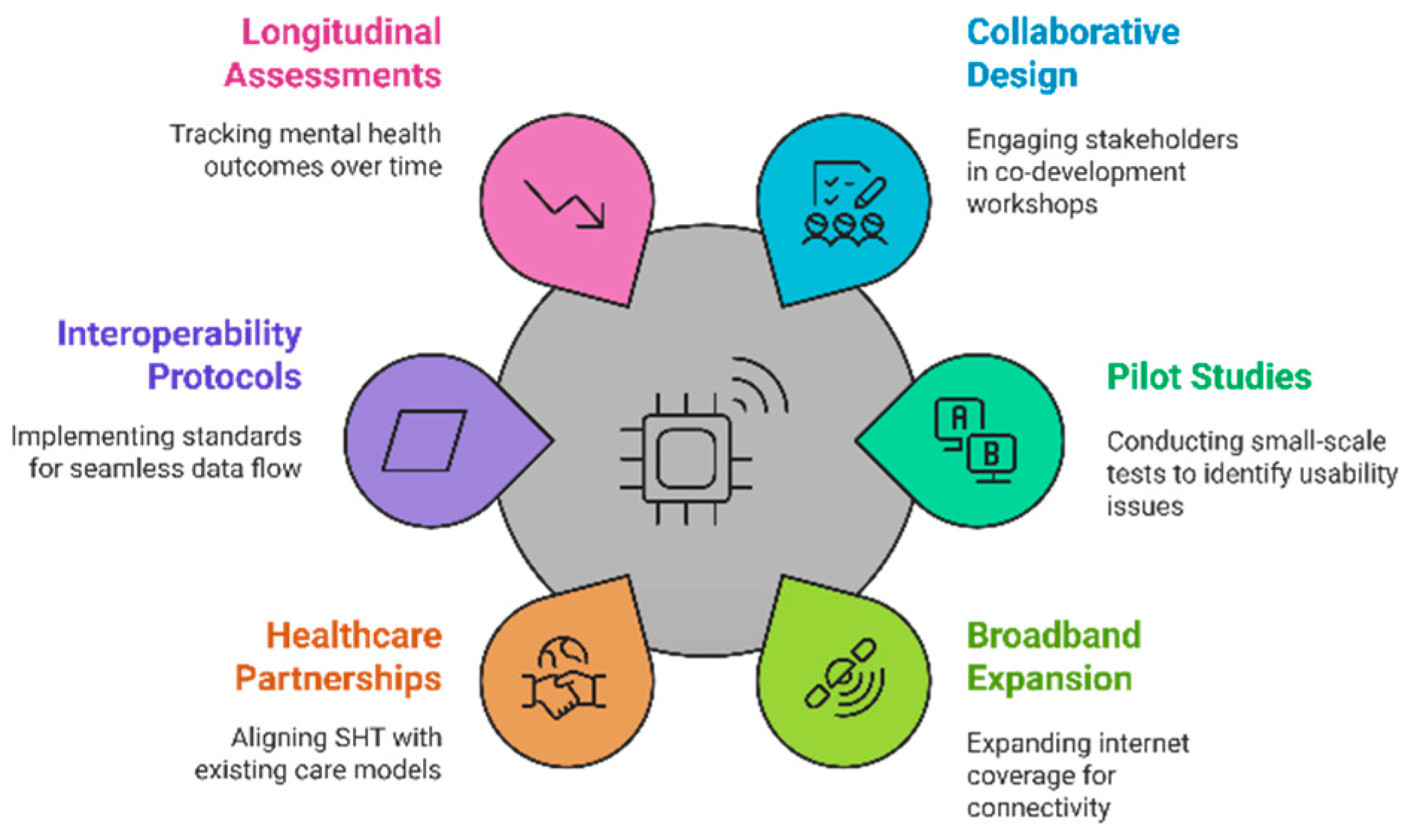

3.4.3. Implementation Pathway

- Phase 2: Scalable Deployment and Infrastructure Integration: 1. Expand broadband coverage and ensure robust connectivity to support real-time data exchange [20]. 2. Partner with healthcare institutions and insurers to align SHT solutions with existing care models, enabling potential subsidies or reimbursement [19,21]. 3. Implement standardized interoperability protocols, facilitating seamless data flow and reducing user confusion [12,13].

- Phase 3: Continuous Evaluation and Policy Support: 1. Establish longitudinal assessment of mental health outcomes, tracking indicators like depression severity, anxiety episodes, and cognitive functioning [31,32]. 2. Develop policy frameworks and ethical guidelines mandating transparent data usage, anonymization protocols, and user-consent mechanisms [15,16]. 3. Encourage iterative updates through user feedback, refining the SHT ecosystem to maintain relevance as older adults’ capabilities and preferences evolve [26,30].

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Findings

4.2. Opportunities for Collaboration

4.3. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Ageing and Health. 2024. Available online: Link (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- World Health Organization. Mental Health of Older Adults. 2024. Available online: Link (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Tian, Y.J.; Felber, N.A.; Pageau, F.; et al. Benefits and Barriers Associated with the Use of Smart Home Health Technologies in the Care of Older Persons: A Systematic Review. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucher, E.M.; Raiker, J.S. Engagement and Retention in Digital Mental Health Interventions: A Narrative Review. BMC Digital Health 2024, 2, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyle, W.; Murfield, J.; Lion, K. The Effectiveness of Smart Home Technologies to Support the Health Outcomes of Community-Dwelling Older Adults Living with Dementia: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2021, 153, 104513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Dieciuc, M.; Carr, D.; et al. New Opportunities for the Early Detection and Treatment of Cognitive Decline: Adherence Challenges and the Promise of Smart and Person-Centered Technologies. BMC Digital Health 2023, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrančić, A.; Zadravec, H.; Orehovački, T. The Role of Smart Homes in Providing Care for Older Adults: A Systematic Literature Review from 2010 to 2023. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 1502–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggar, C.; et al. Smart Home Technology to Support Older People's Quality of Life: A Longitudinal Pilot Study. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2023, 18, e12489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, T.H.; Ma, J.H.; Cha, S.H. Elderly Perception on the Internet of Things-Based Integrated Smart-Home System. Sensors 2021, 21, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holthe, T.; Halvorsrud, L.; Karterud, D.; Hoel, K.A.; Lund, A. Usability and Acceptability of Technology for Community-Dwelling Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia: A Systematic Literature Review. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 863–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolazzi, A.; Quaglia, V.; Bongelli, R. Barriers and Facilitators to Health Technology Adoption by Older Adults with Chronic Diseases: An Integrative Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Arias, A.; Cardona-Acevedo, S.; Gómez-Molina, S.; Gonzalez-Ruiz, J.D.; Valencia, J. Smart Home Adoption Factors: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 9241-11:2018 - Ergonomics of Human-System Interaction—Part 11: Usability: Definitions and Concepts. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Peek, S.T.M.; Wouters, E.J.; van Hoof, J.; et al. Factors Influencing Acceptance of Technology for Aging in Place: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2014, 83, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frik, A.; et al. Privacy and Security Threat Models and Mitigation Strategies of Older Adults. In Proceedings of the USENIX Security Symposium (SOUPS), Santa Clara, CA, USA, 11–13 August 2019. Available online: Link (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Felber, N.A.; Tian, Y.; Pageau, F.; et al. Mapping Ethical Issues in the Use of Smart Home Health Technologies to Care for Older Persons: A Systematic Review. BMC Med. Ethics 2023, 24, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lattie, E.G.; Stiles-Shields, C.; Graham, A.K. An Overview of and Recommendations for More Accessible Digital Mental Health Services. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2022, 1, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.; Heinsch, M.; Betts, D.; et al. Barriers and Facilitators to the Use of E-Health by Older Adults: A Scoping Review. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, M.T.; Blocker, K.A.; Rogers, W.A. Older Adults and Smart Technology: Facilitators and Barriers to Use. Front. Comput. Sci. 2022, 4, 835927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, A.R.; Munson, S.A.; Renn, B.N.; et al. Use of Human-Centered Design to Improve Implementation of Evidence-Based Psychotherapies in Low-Resource Communities: Protocol for Studies Applying a Framework to Assess Usability. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2019, 8, e14990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.N.; Kim, M.J. A Critical Review of Smart Residential Environments for Older Adults with a Focus on Pleasurable Experience. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamwal, R.; et al. Smart Home and Communication Technology for People with Disability: A Scoping Review. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2022, 17, 624–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vailati Riboni, F.; Comazzi, B.; Bercovitz, K.; et al. Technologically-Enhanced Psychological Interventions for Older Adults: A Scoping Review. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorronzoro-Zubiete, E.; Rivera-Romero, O.; Giunti, G.; Sevillano, J.L. Smart Home Applications for Cognitive Health of Older Adults. In Smart Home Technologies and Services for Geriatric Rehabilitation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2022; pp. 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Cho, M.E.; Jun, H.J. Developing Design Solutions for Smart Homes Through User-Centered Scenarios. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorayeb, A.; Comber, R.; Gooberman-Hill, R. Development of a Smart Home Interface with Older Adults: Multi-Method Co-Design Study. JMIR Aging 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; et al. Design Considerations for Mobile Health Applications Targeting Older Adults. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2021, 80, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosravi, P.; Ghapanchi, A.H. Investigating the Effectiveness of Technologies Applied to Assist Seniors: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2016, 85, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghafurian, M.; Wang, K.; Dhode, I.; Kapoor, M.; Morita, P.P.; Dautenhahn, K. Smart Home Devices for Supporting Older Adults: A Systematic Review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 47137–47158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meer, L.; et al. Targeting Personal Recovery of People With Complex Mental Health Needs: The Development of a Psychosocial Intervention Through User-Centered Design. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 635514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vial, S.; Boudhraâ, S.; Dumont, M. Human-Centered Design Approaches in Digital Mental Health Interventions: Exploratory Mapping Review. JMIR Ment. Health 2022, 9, e35591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaportzis, E.; Clausen, M.G.; Gow, A.J. Older Adults’ Perceptions of Technology and Barriers to Interacting with Tablet Computers: A Focus Group Study. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, L.; Pernice, K. UX Design for Seniors (Ages 65 and Older). Nielsen Norman Group, 2020. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Czaja, S.J.; Boot, W.R.; Charness, N.; Rogers, W.A. Designing for Older Adults: Principles and Creative Human Factors Approaches, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).