Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

04 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

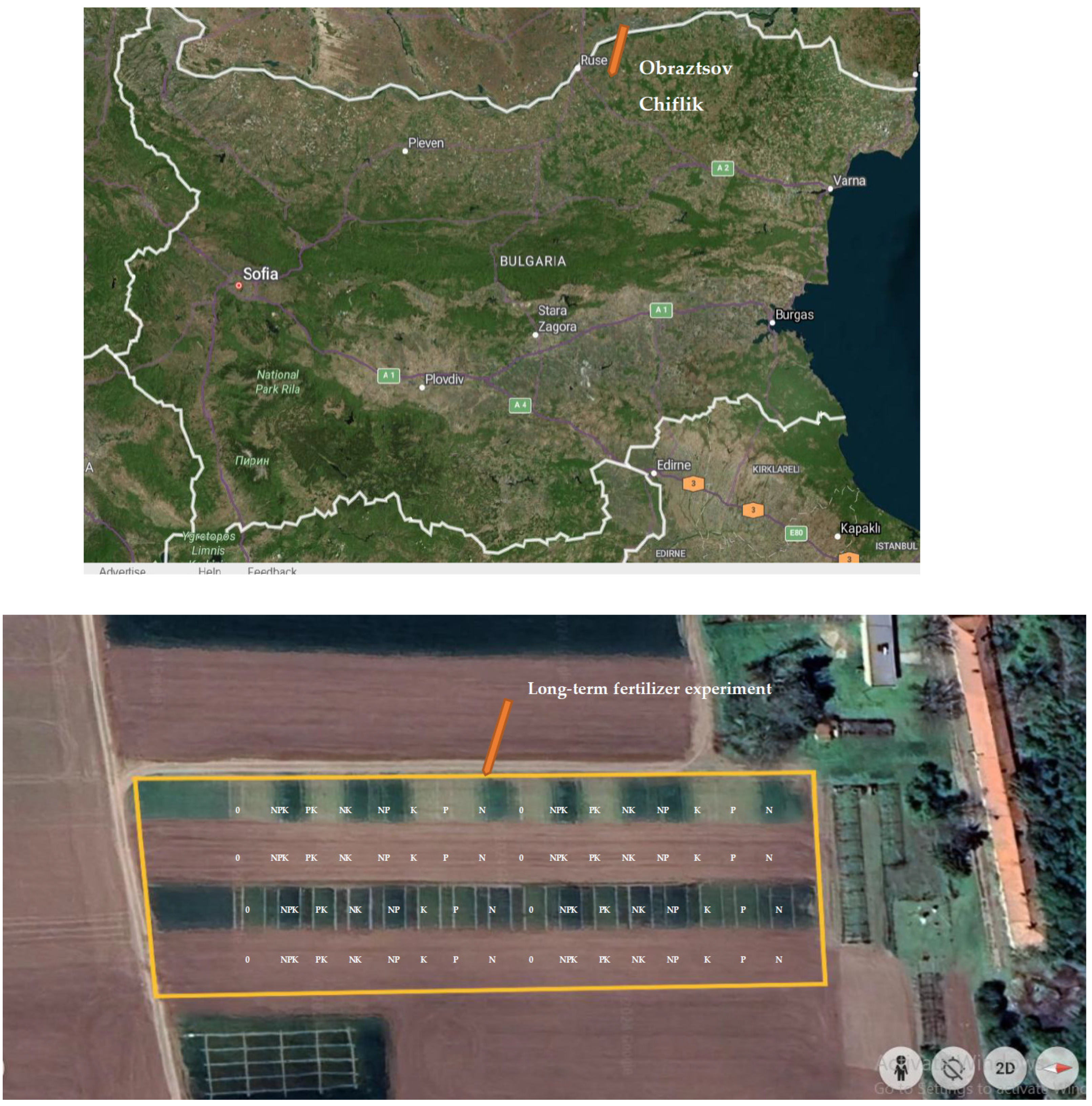

2.1. Site Description

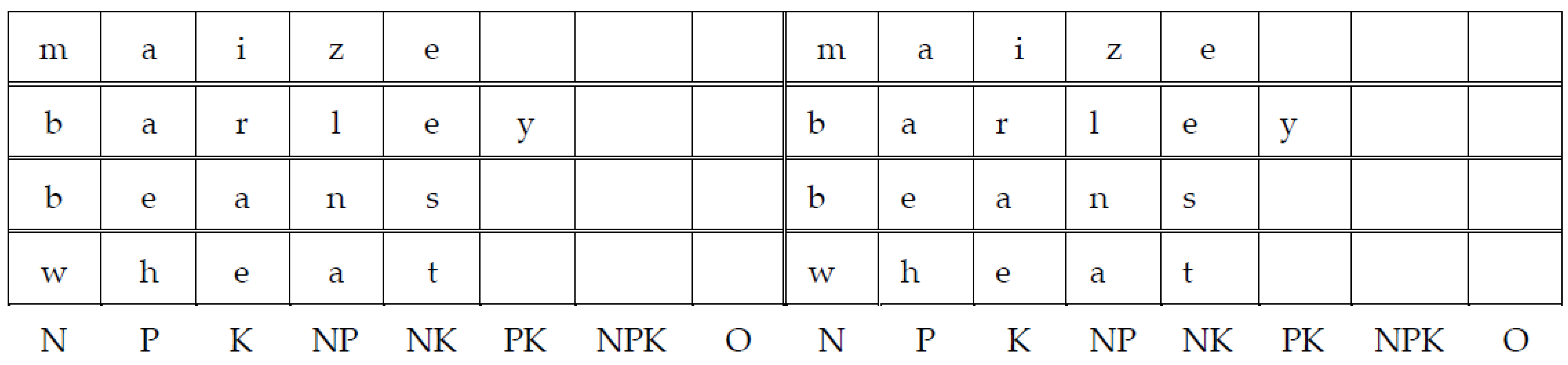

2.2. Experiment Design

2.3. Chemical and Microbiological Analyses

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

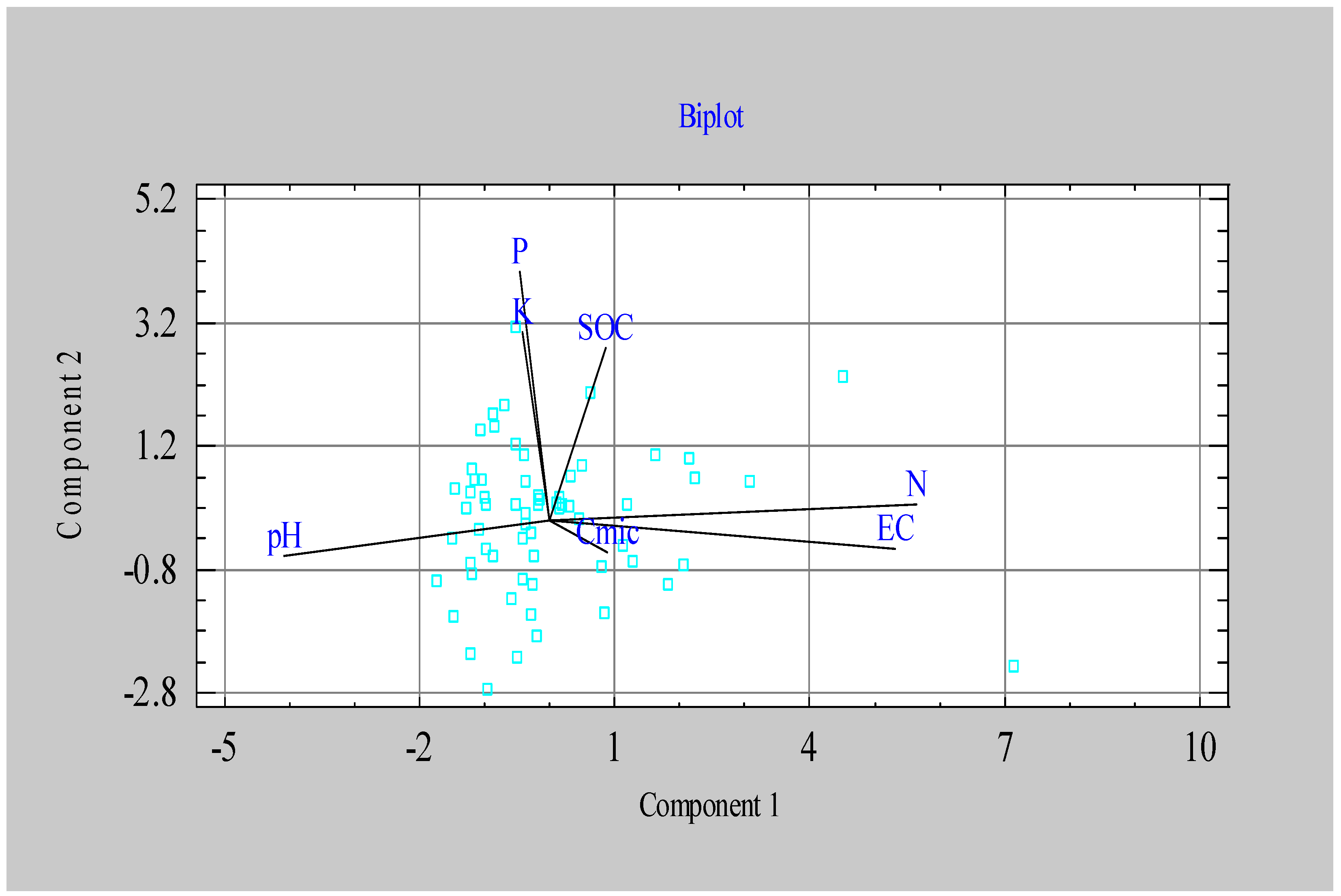

3.1. Soil Chemical Properties and Organic Matter Content

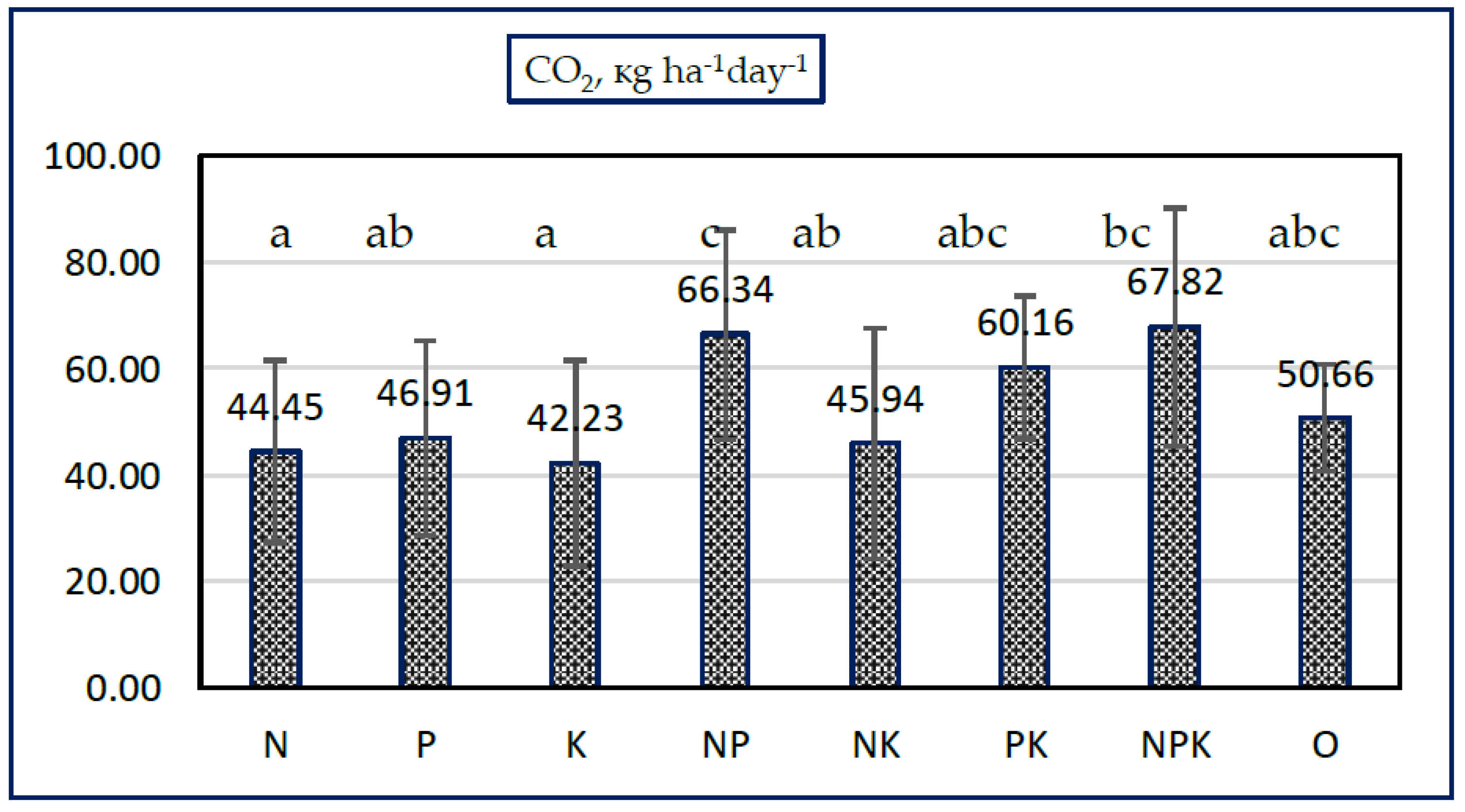

3.2. Effects of Mineral Fertilization on Soil CO2 Emissions

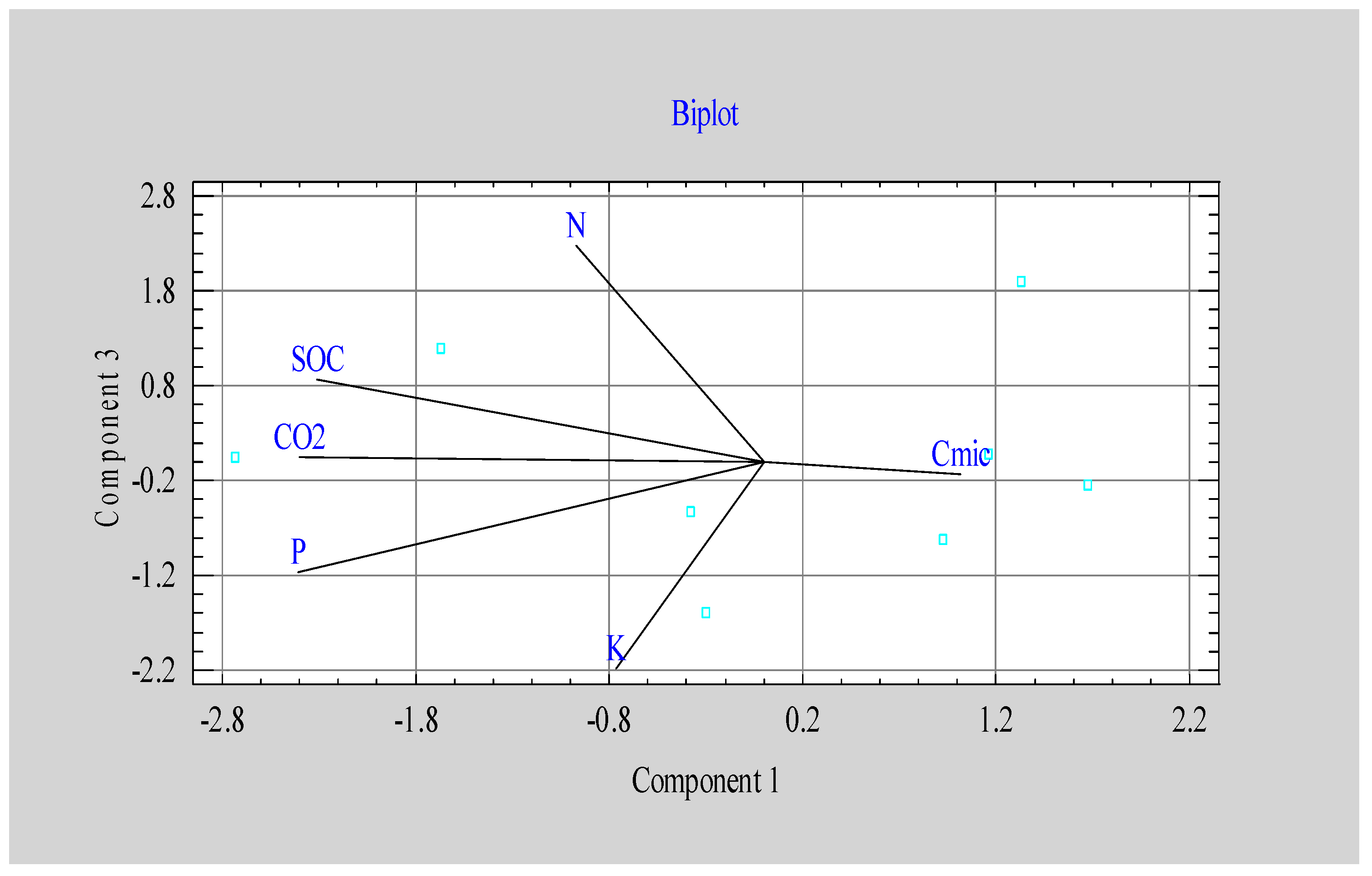

| Component 1 | Component 2 | Component 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalue | 2.47 | 1.46 | 1.22 | |

| Percent of variance | 41.18 | 24.36 | 20.35 | |

| N | -0.220 | 0.450 | 0.655 | |

| P | -0.545 | -0.065 | -0.334 | |

| K | -0.173 | 0.498 | -0.629 | |

| CO2 | -0.544 | -0.064 | 0.012 | |

| Cmic | 0.230 | 0.729 | -0.039 | |

| SOC | -0.524 | 0.101 | 0.250 | |

3.3. Effects of Long-Term Mineral Fertilization on Soil Microbiota.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Francioli D.; Schulz E.; Lentendu G.; Wubet T.; Buscot F.; Reitz T. Mineral vs. organic amendments: Microbial community structure, activity and abundance of agriculturally relevant microbes are driven by long-term fertilization strategies. Front. Microbiol 2016, 7:1446. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X. J.; Liu, J. J.; Wei D.; Zhu, P.; Cui X.; Zhou B. K.; Chen, X; Jin, J.; Liu, V.; Wang, G. Effects of over 30-year of different fertilization regimes on fungal community compositions in the black soils of northeast China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 248 113–122. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Walder, F.; Büchi, L.; Meyer, M.; Held, A.Y.; Gattinger, A.; Keller, T.; Charles, R.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. Agricultural intensification reduces microbial network complexity and the abundance of keystone taxa in roots. ISME J. 2019, 13, 1722–1736. [CrossRef]

- Šimanský, V.; Juriga, M.; Jonczak, J.; Uzarowicz, L.; Stapień, W. How relationships between soil organic matter parameters and soil structure characteristics are affected by the long-term fertilization of a sandy soil. Geoderma 2019, 342, pp. 75-84.

- Ullah, S.; Ai, C.; Ding, W.; Jiang, R.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, W.; Hou, Y.; He, P., The response of soil fungal diversity and community composition to long-term fertilization, Applied Soil Ecology, 2019, Volume 140, Pages 35-41, ISSN 0929-1393. [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Han, X.; Wang, Y.; Han, M.; Shi, H.; Liu, N.; Bai, H. Influence of long-term fertilization on soil microbial biomass, dehydrogenase activity, and bacterial and fungal community structure in a brown soil of northeast China. Ann Microbiol. 2015. 65, pp.533–542 . [CrossRef]

- Šimanský, V.; Jonczak, J.; Horváthová, J.; Igaz, D.; Aydın, E.; Kováčik, P. Does long-term application of mineral fertilizers improve physical properties and nutrient regime of sandy soils? Soil and Tillage Research, 2022, Volume 215, 105224, ISSN 0167-1987. [CrossRef]

- UNEP, United nations environmental programme, Annual evaluation report, 2007 https://www.unep.org/resources/synthesis-reports/unep-annual-evaluation-report-2007.

- Nasser, H.A.; Mahmoud, M.; Tolba, M.M. Radwan, A.R.; Gabr, N.M.; ElShamy, A.A.; Yehya, M.S.; Ziemke, A; Hashem, M.Y. Pros and cons of using green biotechnology to solve food insecurity and achieve sustainable development goals. Euro-Mediterr J Environ Integr. 2021, 29 . [CrossRef]

- Patrick, M.; Tenywa, J.S. ; Ebanyat, P. ; Tenywa, M.M.; Mubiru, D.N.; Basamba, T.A.; Leip, A. Soil organic carbon thresholds and nitrogen management in tropical agroecosystems: concepts and prospects J. Sust. Dev., 2013, 6 , pp. 31-43.

- Galloway, J.N.; Townsend, A.R.;Erisman, J.W.; Bekunda, M.; Cai, Z; Freney, J.R.; Martinelli, L.A.; Seitzinger, S.P.; Sutton, M.A., Transformation of the nitrogen cycle: recent trends, questions and potential solutions. Science. 2008, 320, 889-892.

- Wang, X.; Song, L. Advances in the Study of NO3 – Immobilization by Mic robes in Agricultural Soils. Nitrogen 2024, 5, 927–940. [CrossRef]

- Braos, L.B.; Carlos, R.S.; Bettiol, A.C.T.; Bergamasco, M.A.M.; Terçariol, M.C.; Ferreira, M.E.; da Cruz, M.C.P. Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Forms and Their Relationship with Nitrogen Availability Affected by Cover Crop Species and Nitrogen Fertilizer Doses. Nitrogen 2023, 4, 85–101. [CrossRef]

- Jesmin, T.; Mitchell, D.T.; Mulvaney, R.L. Short-Term Effect of Nitrogen Fertilization on Carbon Mineralization during Corn Residue Decomposition in Soil. Nitrogen 2021, 2, 444–460. [CrossRef]

- Saeed, Q.; Zhang, A.; Mustafa, A.; Sun,B.; Zhang,S.; Yang, X. Effect of long-term fertilization on greenhouse gas emissions and carbon footprints in northwest China: A field scale investigation using wheat-maize-fallow rotation cycles, Journal of Cleaner Production, 2022 Volume 332, 130075, ISSN 0959-6526. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Huang, J.; Wang, B. Long-Term Application of Organic Manure and Mineral Fertilizer on N2O and CO2 Emissions in a Red Soil from Cultivated Maize-Wheat Rotation in China, Agricultural Sciences in China, 2011, Volume 10, Issue 11, pp. 1748-1757, ISSN 1671-2927. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Q.; C. Pu, X. Zhao, J.F. Xue, R. Zhang, Z.J. Nie, F. Chen, R. Lal, H.L. Zhang Tillage effects on carbon footprint and ecosystem services of climate regulation in a winter wheat–summer maize cropping system of the North China Plain Ecol. Indicat., 67 (2016), pp. 821-829.

- Paustian, K.; Larson, E.; Kent, J.; Marx, E.; Swan, A. Soil C sequestration as a biological negative emission strategy Front. Clim., 2019, 1, 10.3389/fclim.2019.00008.

- Bradford, M.A. C; Carey, J.; Atwood, L. ; Bossio, D. ; Fenichel, E.P. ; Gennet, S.; Fargione, J. ; Fisher, J.R.B.; Fuller, E. ; Kane, D.A. ; Lehmann, J.; Oldfield, E.E.; Ordway, E.M.; Rudek, J.; Sanderman, J.; Wood, S.A. Soil carbon science for policy and practice, Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 1070–1072. [CrossRef]

- Çakmakçı, R.; Salık, M.A.; Çakmakçı, S. Assessment and Principles of Environmentally Sustainable Food and Agriculture Systems. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1073. [CrossRef]

- Mattila,V.; Dwivedi, P.; Gauri, P.; Ahbab, Md. Blockchain for Environmentally Sustainable Economies: Case Study of 5irechain. International Journal of Social Sciences and Management Review. 2022, 5, 50-62. [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Soussana, J.F.; Angers, D.; Schipper, L.; Chenu, C.; Rasse, DP.; Batjes, N.H.; van Egmond, F.; McNeill, S.; Kuhnert, M.; Arias-Navarro, C.; Olesen, J.E.; Chirinda, Ngonidzashe; Fornara, D.; Wollenberg, E.; Álvaro-Fuentes, J.; Sanz-Cobena, A. & Klumpp, K. How to measure, report and verify soil carbon change to realise the potential of soil carbon sequestration for atmospheric greenhouse gas removal. Global Change Biology. 2019, 1-23 p.

- Druckman, A.; Jackson, T. The carbon footprint of UK households 1990–2004: A socio-economically disaggregated, quasi-multi-regional input–output model, Ecological Economics, 2009, Volume 68, Issue 7, Pages 2066-2077, ISSN 0921-8009. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Pan, G.; Smith, P.; Luo, T.; Li, L.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, X.; Han, X.; Yan, M. Carbon footprint of China's crop production—An estimation using agro-statistics data over 1993–2007, Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 2011, Volume 142, Issues 3–4, Pages 231-237, ISSN 0167-8809. [CrossRef]

- Suleiman, A.K.A.; Manoeli, L.; Boldo, J.T.; Pereira, M.G.; Roesch, L.F.W. Shifts in soil bacterial community after eight years of land-use change. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 36, 137–144.

- Mahal, N.K.; Osterholz,W.R.; Miguez, F.E.; Poffenbarger, H.J.; Sawyer, J.E.; Olk, D.C.; Archontoulis, S.V., Castellano, M.J.: Nitrogen Fertilizer Suppresses Mineralization of Soil Organic Matter in Maize Agroecosystems. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 7:59. [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Chen, M. M.; Feng, H. J.; Wei, M.; Song, F. P.; Lou, Y. H.; Cui, X.; Wang, H.; Zhuge, Y. Organic and inorganic fertilizers respectively drive bacterial and fungal community compositions in a fluvo-aquic soil in northern China. Soil Till. Res. 2020, 198:104540. [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Xie, B.; Wan, C.; Song, R.; Zhong, W.; Xin, S.; Song, K. Enhancing Soil Health and Plant Growth through Microbial Fertilizers: Mechanisms, Benefits, and Sustainable Agricultural Practices. Agronomy 2024, 14, 609. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, P.; Liu, X. J.; Xiao, L.; Shi, P.; Zhao, B. H. Effects of farmland conversion on the stoichiometry of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus in soil aggregates on the Loess Plateau of China. Geoderma. 2019, 351 188–196. [CrossRef]

- Filcheva, E.; Tsadilas, C. Influence of cliniptilolite and compost on soil properties. Commun. Soil Sci Plan. 2002, 33 (3-4), 595-607. [CrossRef]

- Hoper, H. Substrate-induced respiration. Chapter 6.3 in Bloem, J.; Hopkins D.W.; Benedetti, A. (Eds.), Microbiological Methods for Assessing Soil Quality. Cabi Publishing, 2008, First Edition, https://www.cabi.org/bookshop/book/9780851990989/.

- Grudeva, V.; Moncheva, P.; Nedeva, S.; Gocheva, B.; Antonova-Nedeva, S.; Naumova, S. Handbook of microbiology. University edition SU “St. Kl. Ohridski”, 2007, (Bg).

- Bilandžija, D.; Zgorelec, Ž.; Kisić, I. Influence of Tillage Practices and Crop Type on Soil CO2 Emissions. Sustainability 2016, 8, 90. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, G. P.; Bruulsema, T. W.; Gehl, R. J.;Kanter, D.; Mauzerall, D. L.; Rotz, C. A. Nitrogen–climate interactions in US agriculture.Biogeochemistry. 2013, 114, 41–70. [CrossRef]

- Mulvaney, R. L.; Khan, S. A.; Ellsworth, T. R.: Synthetic nitrogen fertilizers deplete soil nitrogen: a global dilemma for sustainable cereal production. J. Environ. Qual. 2009, 38, 2295–2314. [CrossRef]

- Russell, A. E.; Cambardella, C. A.; Laird, D. A.; Jaynes, D. B.; Meek, D. W. Nitrogen fertilizer effects on soil carbon balances in Midwestern US agricultural systems. Ecol. Appl. 2009. 19, 1102–1113. [CrossRef]

- Poffenbarger, H. J.; Barker, D. W.; Helmers, M. J.; Miguez, F. E.;Olk, D. C.; Sawyer, J. E.Maximum soil organic carbon storage in Midwest US cropping systems when crops are optimally nitrogen-fertilized. PLoS ONE. 2017, 12:e0172293. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Sun, B.; Lu, F.; Wang, X.; Zhuang, T.; Zhang, G.; Ouyang, X. Roles of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium fertilizers in carbon sequestration in a Chinese agricultural ecosystem. Climatic Change. 2017, 142, 587–596 . [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Wang, W. Combination of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilization enhance ecosystem carbon sequestration in a nitrogen-limited temperate plantation of Northern China, Forest Ecology and Management, 2015, Volume 341, Pages 59-66, ISSN 0378-1127. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Shen, F. Y., Liu, Y., Yang, Y. C., Wang, J., Purahong, W., et al. (2022). Contrasting altitudinal patterns and co-occurrence networks of soil bacterial and fungal communities along soil depths in the cold-temperate montane forests of China. Catena 209:105844. [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Kästner, M.; Rainer Georg, J. Microbial necromass on the rise: the growing focus on its role in soil organic matter development. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 150:108000. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, H.; Reich, .B.; Banerjee, S.; van der Heijden, M.G.A.; Sadowsky, M.J.; Ishii, S.; Jia, X.; Shao, M.; Liu, B.; Jiao, H.; Li, H.; Wei, X. Erosion reduces soil microbial diversity, network complexity and multifunctionality, The ISME Journal, 2021, Volume 15, Issue 8, Pages 2474–2489. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Jiang, X.; Zhou, B.; Zhao, B. S.; Ma, M. C.; Guan, D. W.; Li, J.; Chen, S.; Cao, F.; Shen, D.; Qin, J. Thirty-four years of nitrogen fertilization decreases fungal diversity and alters fungal community composition in black soil in northeast China. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 95, 135–143. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Chen, K.; Shi, J.; Wang, Y.; Luo, P.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Han, X. Long-term fertilization altered microbial community structure in an aeolian sandy soil in northeast China. Front. Microbiol. 2022 13:979759. [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Han, X.; Wang, Y.; Han, M.; Shi, H.; Liu, N.; Bai, H. Influence of long-term fertilization on soil microbial biomass, dehydrogenase activity, and bacterial and fungal community structure in a brown soil of northeast China. Ann Microbiol. 2015, 65, pp. 533–542 . [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Cheng, M.; Wen, Y.; Darboux, F. Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration under Long-Term Chemical and Manure Fertilization in a Cinnamon Soil, Northern China. Sustainability, 2022, 14, 5109. https:// doi.org/10.3390/su14095109.

- Hu, X.K.; Su, F.; Ju, X.T.; Gao, B.; Oenema, O.; Christie, P.; Huang, B.X.; Jiang, R.F.; Zhang, F.S. Greenhouse gas emissions from a wheat–maize double cropping system with different nitrogen fertilization regimes, Environmental Pollution, 2013, Volume 176 , Pages 198-207,ISSN 0269-7491.

| Soil layer | Fractions according to FAO (2006), % | USDA | Texture class | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cm | Sand 2-0.063 mm |

Silt 0.063-0.002 mm |

Clay <0.002 mm |

Sand 2-0.05 mm |

|

| 0-5 | 5,7 | 65,5 | 28,8 | 8,1 | SiCL |

| 10-15 | 4,0 | 65,6 | 30,3 | 7,5 | SiCL |

| 15-20 | 4,4 | 65,1 | 30,4 | 7,5 | SiCL |

| Treatment | N (N-NO3, N-NH4) | P2O5 | K2O | EC | pH | SOC | Cmic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 121.74 d | 15.97 a | 27.13 a | 90.43 c | 5.44 ab | 1.22 bc | 300.9 bc | |||||||

| P | 28.88 ab | 35.21 c | 34.09 b | 29.13 a | 5.90 d | 1.34 cd | 274.3 abc | |||||||

| K | 28.81 ab | 21.02 ab | 42.1 c | 29.92 ab | 5.89 cd | 1.24 bc | 304.0 bc | |||||||

| NP | 83.00 bcd | 27.58 bc | 29.74 ab | 46.79 ab | 5.44 ab | 1.43 d | 245.2 ab | |||||||

| NK | 90.06 cd | 16.39 a | 43.95 c | 56.39 abc | 5.30 a | 1.25 bc | 343.8 c | |||||||

| PK | 36.74 abc | 31.83 c | 46.17 c | 39.01 ab | 5.66 bc | 1.18 ab | 303.3 bc | |||||||

| NPK | 121.29 d | 37.53c | 45.83 c | 70.54 bc | 5.42 a | 1.42 d | 263.8 abc | |||||||

| 0 | 21.92 a | 17.11 a | 31.23 ab | 25.10 a | 5.82 cd | 1.05 a | 209.1 a | |||||||

| ANOVA factors | F ratio |

P value |

F ratio |

P value | F ratio | P value | F ratio | P value | F ratio | P value |

F ratio |

P value |

F ratio |

P value |

| Treatment | 4.36 | 0.00007 | 5.77 | 0.0000 | 11.66 | 0.0000 | 2.54 | 0.025 | 8.02 | 0.000 | 5.94 | 0.0000 | 2.11 | 0.059 |

| Season | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | 7.43 | 0.009 | 19.47 | 0.0001 | NS | NS | 22.40 | 0.000 |

| Crop | 6.86 | 0.0006 | 9.66 | 0.0000 | 2.23 | 0.095 | 3.51 | 0.021 | 6.39 | 0.0009 | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Component 1 | Component 2 | Component 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalue | 2.23 | 1.35 | 1.27 |

| Percent of variance | 31.83 | 19.26 | 18.20 |

| N | 0.632 | 0.072 | -0.028 |

| P | -0.070 | 0.402 | -0.522 |

| K | -0.126 | 0.581 | 0.230 |

| pH | -0.423 | -0.416 | -0.321 |

| EC | 0.611 | -0.118 | -0.045 |

| SOC | 0.087 | 0.261 | -0.710 |

| Cmic | 0.145 | -0.490 | -0.255 |

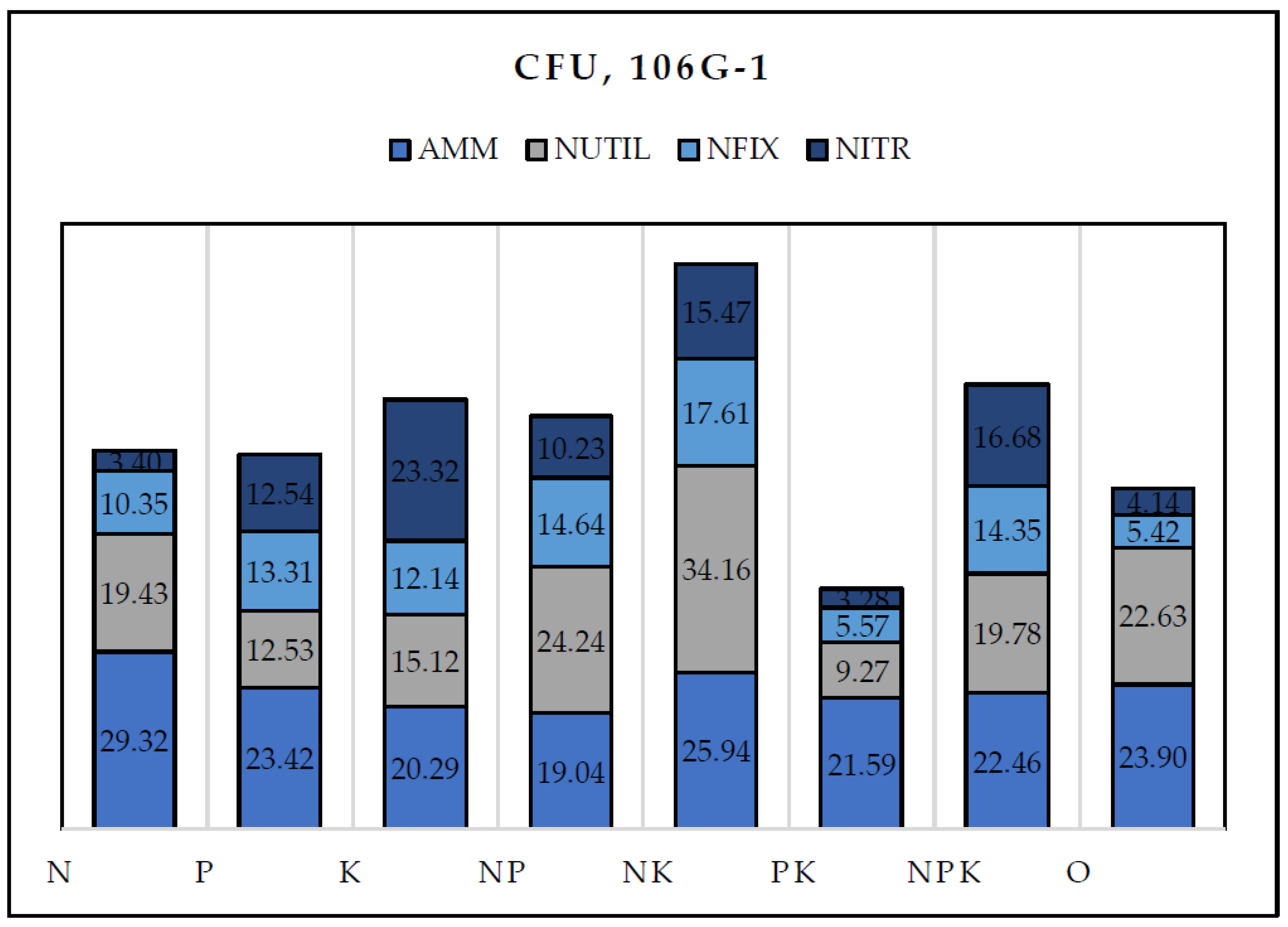

| Treatment | Ammonifying bacteria | Nitrogen fixing bacteria |

Nitrogen utilizing bacteria | Nitrifying bacteria | Actinomycetes | Microscopic fungi | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 29.32b | ±27.3 | 10.35ab | ±15.1 | 19.43abc | ±26.5 | 3.40a | ±5.9 | 0.51ab | ±0.3 | 0.061abc | ±0.03 | ||||||

| P | 23.42a | ±13.9 | 13.31ab | ±19.4 | 12.53ab | ±14.7 | 12.54abc | ±16.7 | 0.44a | ±0.4 | 0.043a | ±0.06 | ||||||

| K | 20.29a | ±20.1 | 12.14ab | ±19.7 | 15.12ab | ±19.6 | 23.32c | ±26.6 | 0.55ab | ±0.5 | 0.046ab | ±0.05 | ||||||

| NP | 19.04a | ±22.6 | 14.64ab | ±16.7 | 24.24bcd | ±29.2 | 10.23ab | ±14.1 | 0.40a | ±0.3 | 0.069c | ±0.07 | ||||||

| NK | 25.94a | ±32.6 | 17.61a | ±44.1 | 34.16cd | ±72.7 | 15.47bc | ±39.3 | 0.48ab | ±0.5 | 0.061bc | ±0.06 | ||||||

| PK | 21.59a | ±32.3 | 5.57 | ±8.2 | 9.27ab | ±21.2 | 3.28a | ±5.6 | 0.66b | ±0.5 | 0.047ab | ±0.05 | ||||||

| NPK | 22.46a | ±27.8 | 14.35a | ±31.9 | 19.78a | ±46.0 | 16.68a | ±41.3 | 0.41a | ±0.3 | 0.050ab | ±0.04 | ||||||

| 0 | 23.90b | ±32.3 | 5.42ab | ±4.4 | 22.63d | ±33.1 | 4.14bc | ±5.0 | 0.32a | ±0.3 | 0.044ab | ±0.04 | ||||||

| ANOVA factors |

F ratio |

P value |

F ratio |

P value |

F ratio |

P value |

F ratio |

P value |

F ratio |

P value |

F ratio |

P value |

||||||

| Treatment | 1.45 | 0.186 | 1.25 | 0.277 | 3.65 | 0.001 | 3.25 | 0.003 | 1.79 | 0.092 | 2.32 | 0.0276 | ||||||

| Season | 67.76 | 0.000 | 41.01 | 0.000 | 73.28 | 0.000 | 49.96 | 0.000 | 35.96 | 0.000 | 265.27 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Crop | 4.77 | 0.003 | 2.42 | 0.068 | 2.34 | 0.074 | 2.97 | 0.033 | 5.02 | 0.002 | 13.61 | 0.000 | ||||||

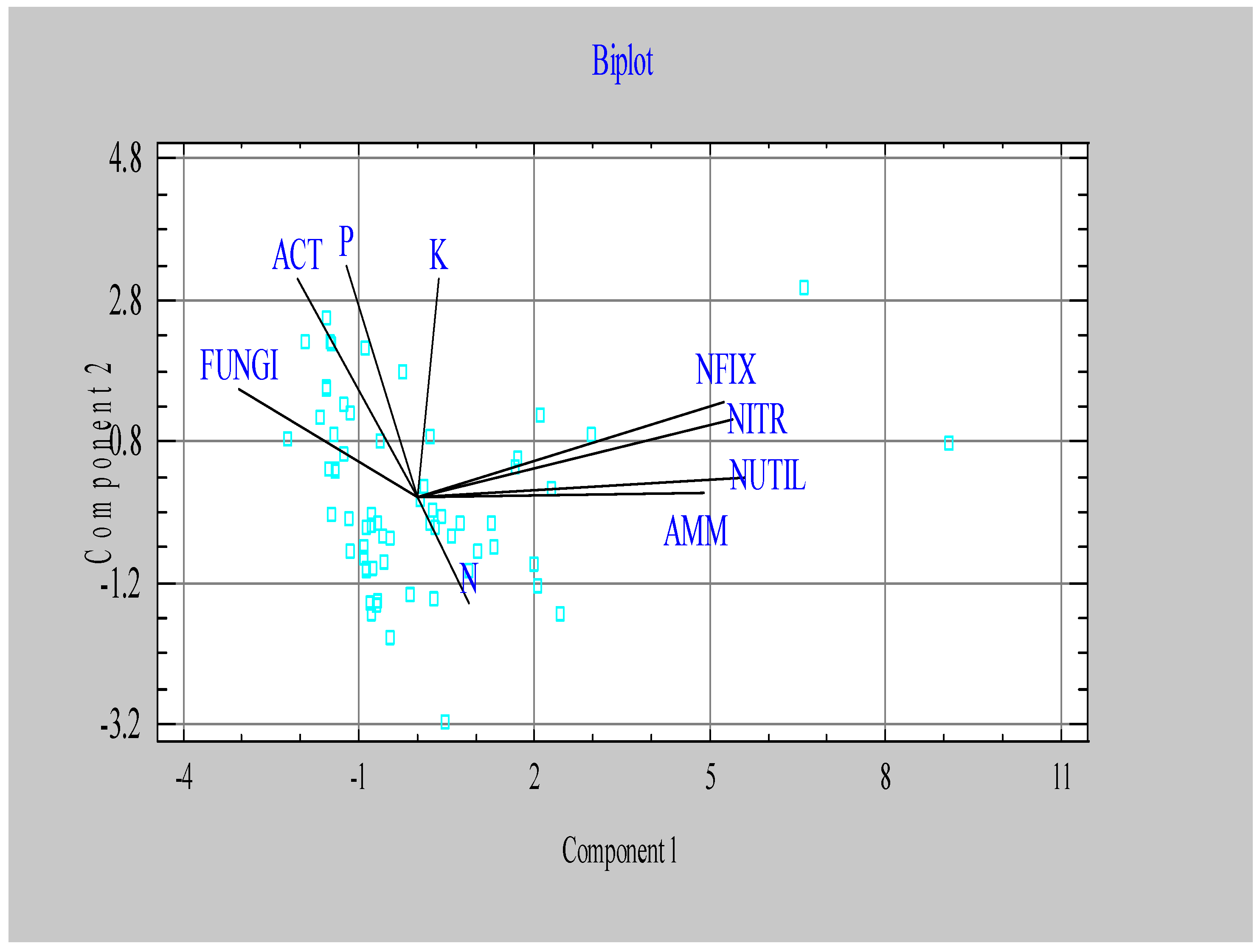

| Component 1 | Component 2 | Component 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalue | 5.54 | 1.53 | 1.06 |

| Percent of variance | 39.29 | 17.00 | 11.75 |

| N | 0.078 | -0.244 | 0.724 |

| P | -0.107 | 0.533 | 0.377 |

| K | 0.033 | 0.505 | 0.402 |

| ACT | -0.181 | 0.504 | -0.326 |

| FUNGI | -0.271 | 0.249 | -0.179 |

| AMM | 0.433 | 0.012 | -0.090 |

| NITR | 0.464 | 0.223 | 0.005 |

| NFIX | 0.476 | 0.180 | -0.059 |

| NUTIL | 0.496 | 0.049 | -0.146 |

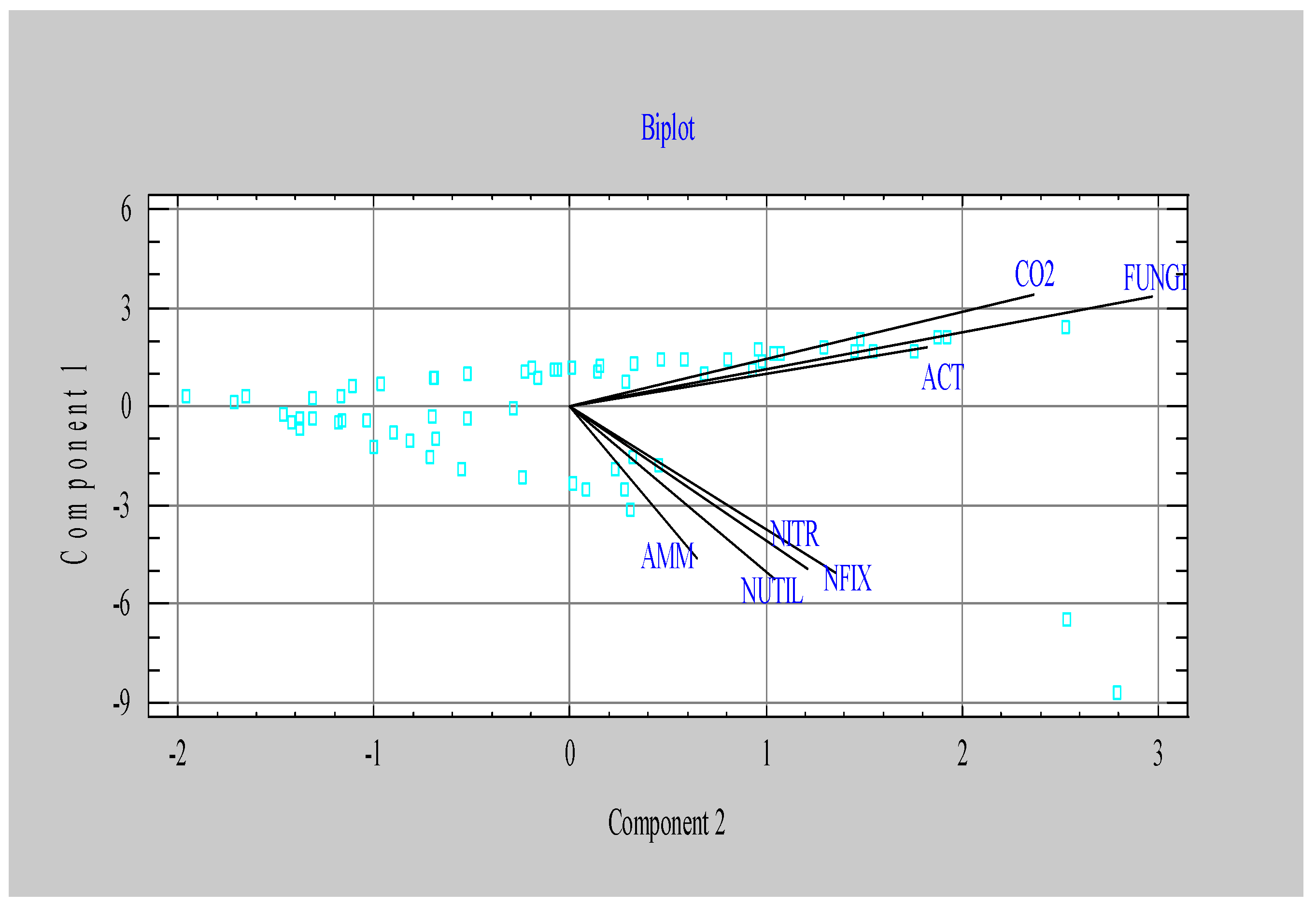

| Component 1 | Component 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalue | 3.77 | 1.29 |

| Percent of variance | 53.81 | 18.40 |

| CO2 | 0.307 | 0.498 |

| NFIX | -0.450 | 0.285 |

| NITR | -0.441 | 0.255 |

| NUTIL | -0.470 | 0.220 |

| ACT | 0.161 | 0.384 |

| AMM | -0.415 | 0.137 |

| FUNGI | 0.298 | 0.626 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).